Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Acessos

Acessos

Links relacionados

-

Similares em

SciELO

Similares em

SciELO

Compartilhar

GE-Portuguese Journal of Gastroenterology

versão impressa ISSN 2341-4545

GE Port J Gastroenterol vol.27 no.2 Lisboa abr. 2020

https://doi.org/10.1159/000501939

ORIGINAL ARTICLE

Clinicopathologic Characteristics of Patients with Gastric Superficial Neoplasia and Risk Factors for Multiple Lesions after Endoscopic Submucosal Dissection in a Western Country

Caracterização clinicopatológica dos doentes com neoplasias gástricas superficiais e fatores de risco para lesões múltiplas após dissecção endoscópica da submucosa num país ocidental

Gisela Brito-Gonçalvesa, Diogo Libâniob,c, Pedro Marcosb,d, Inês Pitab, Rui Castrob, Inês Sáb, Mário Dinis-Ribeirob,c, Pedro Pimentel-Nunesb,c,e

aFaculty of Medicine, University of Porto, Porto, Portugal; bDepartment of Gastroenterology, Portuguese Oncology Institute, Porto, Portugal; cMEDCIDS, Departamento de Medicina da Comunidade, Informação e Decisão em Saúde, Faculty of Medicine, University of Porto, Porto, Portugal; dDepartment of Gastroenterology, Centro Hospitalar Leiria, Leiria, Portugal; eDepartment of Surgery and Physiology, Faculty of Medicine, University of Porto, Porto, Portugal

* Corresponding author.

ABSTRACT

Background: Endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD) is a treatment for early gastric neoplasms that preserves the stomach. However, the risk of multiple lesions persists. Objectives: To assess clinicopathologic characteristics of patients with early gastric neoplasms in a Western country and evaluate risk factors for multiple gastric lesions, synchronous, or metachronous. Methods: A retrospective cohort of 230 consecutive patients who underwent ESD for primary neoplasms from 2012 to 2017 (median follow-up: 33 months) was assessed to determine the clinicopathologic characteristics and risk factors for multiple lesions. Results: The mean age was 68 years, and 53.9% were male. Current/former smoking status was present in 40.4%, and 29.5% had family history of gastric cancer. A third of the patients had only focal gastric atrophy/metaplasia (operative link on gastritis assessment/operative link on gastric intestinal metaplasia assessment [OLGA/OLGIM] I/II; endoscopic grading of gastric intestinal metaplasia [EGGIM] 1–4). Synchronous and metachronous lesions occurred in 14.3 and 8.6% of patients, respectively. There was a trend for higher risk of multiple lesions in smokers and patients with extensive metaplasia (EGGIM > 4), but only older age was an independent risk factor (OR 3.30; 95% CI 1.05–10.34). Age > 60 years (OR 10.10, 95% CI 1.40–88.04), current/former smoking status (OR 3.64, 95% CI 1.07–12.40), and OLGIM III/IV (OR 3.07, 95% CI 1.01–9.36) were independent risk factors for synchronous lesions. No risk factors for metachronous lesions were found. Conclusions: Surveillance limited to patients with advanced stages of gastritis may miss some primary superficial neoplasms. Although older age increases the risk of multiple lesions, no risk factors were found for metachronous lesions. Therefore, endoscopic surveillance after ESD should be done equally in all patients.

Keywords: Stomach neoplasms, Endoscopic submucosal dissection, Multiple primary neoplasms, Secondary neoplasms, Risk factors

RESUMO

Introdução: A dissecção endoscópica da submucosa (DES) é uma opção terapêutica para neoplasias gástricas em estadios iniciais e que permite preservar o estômago. No entanto, o risco de desenvolver lesões múltiplas mantém- se. Objetivos: Avaliar as características clinicopatológicas dos pacientes com neoplasias gástricas superficiais primárias num país ocidental e avaliar os fatores de risco (FR) para lesões gástricas múltiplas, síncronas ou metácronas. Métodos: Foram estudados, retrospetivamente, 230 doentes submetidos a DES por lesões gástricas primárias entre 2012 e 2017 (tempo de seguimento mediano: 33 meses). As características clínicopatológicas e os FR para lesões múltiplas foram analisados. Resultados: A idade média foi de 68 anos, 53,9% eram homens, 40,4% eram fumadores/ex-fumadores e 29,5% tinham história familiar de cancro gástrico. Um terço dos pacientes apresentava apenas atrofia/metaplasia focal (OLGA/OLGIM I/II; EGGIM 1–4). Foram detetadas lesões síncronas em 14,3% e metácronas em 8,6% dos doentes. Para lesões gástricas múltiplas, tabagismo e metaplasia extensa (EGGIM> 4) mostraram uma associação, mas apenas a idade avançada foi FR independente (Odds Ratio [OR] 3, 30; Intervalo de Confiança a 95% [IC 95%] 1, 05–10, 34). Idade superior a 60 anos (OR 10,10; IC95% 1,40–88,04), tabagismo (OR 3,64; IC95% 1,07–12,40) e OLGIM III/IV (OR 3,07; IC95% 1,01–9,36) foram FR independentes para lesões síncronas. Não foram encontrados FR para lesões metácronas. Conclusões: Limitar a vigilância aos pacientes com gastrite em estadios avançados não permite identificar todas as lesões neoplásicas precoces. A idade avançada aumenta o risco de lesões múltiplas, contudo não foi encontrado nenhum FR para lesões metácronas. Assim, a vigilância endoscópica após DES deve ser idêntica em todos os pacientes.

Palavras-Chave: Neoplasias gástricas, Dissecção endoscópica da submucosa, Neoplasias primárias múltiplas, Neoplasias secundárias, Fatores de risco

Introduction

Gastric cancer is the fifth most common malignancy and the third leading cause of cancer-related death worldwide [1]. The development of new endoscopic techniques and their increasing availability made possible the diagnosis of neoplasms in initial stages. Some risk factors for gastric cancer are established (namely, Helicobacter pylori infection and family history), although less is known about the clinicopathologic characteristics of patients with superficial gastric neoplasms in Western countries. The knowledge of risk factors for superficial neoplasms could influence screening policies and surveillance schedules.

Endoscopic mucosal resection and endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD) are effective minimally invasive techniques that have been used as an alternative to surgery for treatment of early gastric cancer (EGC) [2–4]. ESD allows en bloc resection with tumor-free margins even for large lesions [5, 6], preventing residual disease, and local recurrence. ESD is now recommended as the first-line treatment for superficial gastric lesions [7].

As a result of preserving the entire stomach after endoscopic treatment, there is an improvement in patients quality of life when compared to surgery (total or partial gastrectomy) [8]. Nevertheless, a risk of synchronous and metachronous gastric lesions (SGLs and MGLs, respectively) in the remnant mucosa persists [9–12].

SGLs have been reported in 3.4–10.9% of all patients with gastric cancer [13–15]. Cumulative incidence of developing MGLs after endoscopic resection of EGC has been reported as varying from 2.7 to 15.6% [16]. Therefore, a follow-up is necessary after ESD, and it is also important to identify factors that may contribute to the risk of SGLs and MGLs.

There are some risk factors proven to be associated with gastric cancer development [17]. Even though some reports suggest a few factors associated with multiple gastric lesions, there are no established risk factors for SGLs and MGLs, particularly in Western countries.

The aims of this study were to describe for the first time in a Western country the clinical features of patients treated with ESD for primary gastric superficial neoplasms and to analyze risk factors for the presence of SGLs and for the development of MGLs after ESD.

Materials and Methods

Study Design and Selection of Patients

All patients who had undergone ESD for primary early gastric neoplasms (low- or high-grade dysplasia [HGD]; ECG) in a tertiary-care medical center (Instituto Portugues de Oncologia do Porto – Francisco Gentil, E.P.E.) between January 2012 and December 2017 were retrospectively reviewed and included in the study unless meeting exclusion criteria (previous history of gastric cancer, gastrectomy, or endoscopic resection). ESD technique was previously described [12, 18].

Additional exclusion criteria were follow-up time < 12 months, follow-up in another hospital, and absence of follow-up data. In addition, patients with lynch syndrome and familial adenomatous polyposis who have an increased risk of early gastric neoplasms were also excluded.

All the patients meeting selection criteria were considered for the analysis of clinicopathological variables and risk factors for SGLs. In the analysis of risk factors for MGLs, patients who underwent subsequent gastrectomy due to noncurative ESD or for a different reason were excluded.

The protocol study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Instituto Portugues de Oncologia do Porto – Francisco Gentil, E.P.E.

Characterization of Patients Treated by ESD

Patients medical records, endoscopy and ESD reports, and histological results were retrieved from electronic medical records.

To define clinicopathologic characteristics of patients with gastric neoplasms treated with ESD the following variables were analyzed: age, gender, smoking status, alcohol consumption, family history of gastric cancer, H. pylori status at diagnosis, mucosal neutrophilic inflammation, atrophy, and intestinal metaplasia, operative link on gastritis assessment (OLGA) [19], operative link on gastric intestinal metaplasia assessment (OLGIM) [20], endoscopic grading of gastric intestinal metaplasia (EGGIM) [21], histologic lesion size, location, pathologic diagnosis of resected specimen, differentiation, curability evaluation (classical or expanded indication) [7, 22]. EGGIM is a scale for EGGIM using high-resolution endoscopy with narrow-band imaging, which evaluates the extent of intestinal metaplasia in 5 different areas of the stomach (lesser and greater curvature of the antrum, lesser and greater curvature of the corpus, and incisura). Each one is scored 0 (no intestinal metaplasia), 1 (focal intestinal metaplasia), or 2 points (extensive intestinal metaplasia), giving a maximum score of 10 points [21]. This was always calculated using Olympus HQ-190 scopes. Since this classification was only created in 2015, EGGIM data were collected from the first endoscopy report that stated this classification when available.

Follow-up time was also recorded, as well as the time until metachronous detection; patients were censored from time-toevent analysis at the time of loss to follow-up, gastrectomy, or death.

Management after ESD

After ESD, all patients with H. pylori infection were proposed for eradication as recommended [23–25]. First follow-up esophagogastroduodenoscopy was scheduled between 3 and 6 months after ESD and the second at 12 months. Then a follow-up endoscopy was performed every year.

Definition and Characterization of SGL or MGLs

SGL was defined as a concomitant lesion (either dysplasia or adenocarcinoma) in a different location of the stomach at the time of ESD or until 12 months after ESD for the primary lesion; a lesion was considered synchronous if both lesions had a clear border (i.e., 1 demarcation line for each one). MGL was defined as a newly developed dysplasia or adenocarcinoma that was detected at least 12 months after the primary procedure.

For patients with > 1 MGL, only the first one of each was studied. If > 1 lesions were diagnosed at the same time, only the most histologically advanced was considered. In case they had the same histological grade, only the larger lesion was analyzed.

Multiple lesions were defined as having a second lesion at the time or after resection (SGL, MGL, or both).

Definition of Risk Factors

Several potential clinical risk factors were analyzed: age, gender, smoking status, alcohol consumption, family history of gastric cancer, H. pylori status at diagnosis and during follow-up, and continuous use of aspirin and proton pump inhibitors (PPIs). Smoking status was classified into current, former (cessation of smoking for at least 12 months before the diagnosis), or never smoker. Alcohol daily intake was classified into drinking ≤40 and > 40 g in a day. H. pylori infection status and eradication were tested by histologic assessment (Giemsa staining) using gastric biopsies from the body and antrum. Use of PPI after ESD for > 12 months was defined as continuous. Use of aspirin was defined as continuous if it started previously to the diagnosis of the primary lesion and occurred for > 12 months.

Additionally, some potential risk factors related to stomach histopathologic evaluation were tested: histologic lesion size; pathologic diagnosis (dysplasia or EGC); tumor differentiation (well and moderately differentiated; undifferentiated); polymorphonuclear neutrophil activity of the background gastric mucosa; mucosal atrophy and intestinal metaplasia; and chronic atrophic/metaplastic gastritis of the background mucosa (based on OLGA, OLGIM, and EGGIM scores). The lesion location was classified by dividing the stomach into 3 segments: upper third (cardia, fundus, and upper and middle body), middle third (lower body, body-antrum transition, and angular incisura), and lower third (antrum). Intestinal metaplasia, mucosal atrophy, and polymorphonuclear neutrophil activity were evaluated by histologic examination of gastric biopsy samples.

These parameters were classified by the Updated Sydney System [26]. Based on this data, OLGA [19] and OLGIM [20] were calculated.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using IBM SPSS version 25.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). Categorical variables are presented as proportions, while continuous variables are presented as mean and SD or mean and range (minimum – maximum).

Differences between groups were evaluated with Pearson χ2 test or Fishers exact test for categorical variables, as appropriate. Variables with a p value < 0.1 in univariate analysis and variables with major clinical relevance (based on previous studies) were included in the multivariable analysis (binary logistic regression). Cumulative probabilities of multiple lesions were estimated by the Kaplan-Meier method. The log-rank test was used to compare the time-to-event curves of multiple gastric lesions according to age at the time of diagnosis and EGGIM score.

OR and 95% CIs are reported for each variable. A p value < 0.05 was regarded as statistically significant.

Results

Study Population

During the study period, 281 patients underwent ESD for primary gastric superficial neoplasia. One patient (0.36%) with lynch syndrome and 3 (1.07%) with familial adenomatous polyposis were excluded. Additionally, 47 patients (16.73%) with follow-up in another hospital or for < 12 months were also excluded. Therefore, a total of 230 patients were included in the primary analysis; 32 patients were further submitted to gastrectomy (one due to a gastrointestinal stromal tumor) and excluded from MGLs analysis. The median follow-up time of these 198 patients was 33 months (range 12–83 months).

Patients Clinicopathologic Characteristics

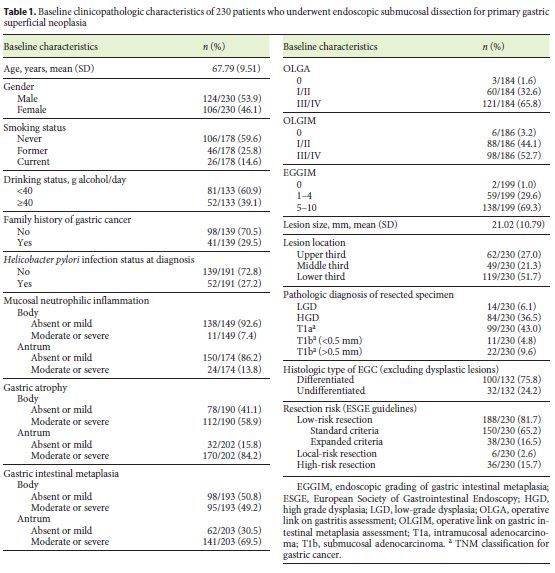

Clinicopathologic characteristics of patients who underwent ESD for primary gastric superficial neoplasia are shown in Table 1. The mean age at diagnosis was 67.8 years (SD 9.5) and 53.9% were male. Almost one-third of patients (29.5%) had a positive family history of gastric cancer. Sixty per cent of the patients had never smoked, while 14.6% were active tobacco consumers and 25.8% were former smokers. Most of the lesions were located in the lower third of the stomach (51.7%), and the majority was classified as HGD or intramucosal adenocarcinoma (36.5 and 43.0%, respectively). H. pylori infection was found in 27.2% of patients at the time of gastric neoplasia diagnosis.

Moderate to severe gastric atrophy and intestinal metaplasia (gastric body or/and antrum) were present in 85.3 and 74.5% of the study population, respectively. The proportion of patients with moderate to severe gastric atrophy/ intestinal metaplasia was not significantly different between patients with single or multiple lesions.

Almost all patients (98.4%) had gastric atrophy or intestinal metaplasia (32.6% OLGA I/II, 65.8% OLGA III/ IV, 44.1% OLGIM I/II, 52.7% OLGIM III/IV). EGGIM score of 0 was identified in 1.0% of patients; EGGIM scores of 1–4 and 5–10 were identified in 29.6 and 69.3% of patients, respectively.

Curative resection accounted for 81.7% of patients. Only 31 patients out of 42 who had no curative criteria underwent surgery. The remaining 11 patients were carefully followed up without surgery because of advanced age and comorbidities or due to surgery refusal. Only one of these patients developed a MGL.

Characterization of Synchronous and Metachronous Lesions

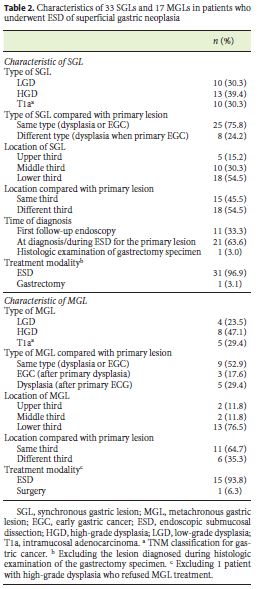

Among 230 patients who underwent ESD for superficial gastric neoplasia, 47 (20.4%) had multiple lesions. Thirty-three patients (14.3%) had SGLs, and their characteristics are presented in Table 2. Twenty-one lesions (63.6%) were detected at the same time as the primary lesion or during ESD and eleven (33.3%) during the first follow-up endoscopy. More than half of the SGLs (54.5%) were in the lower third of the stomach, and 39.4% were HGD. Comparing with the primary gastric lesions, 45.5% of SGLs were located in the same stomach third.

During follow-up time, 17 of 198 (8.6%) patients developed MGLs. The mean annual incidence of MGLs was 3.1 per 100 patient-years. The median interval time between ESD and the diagnosis of the first MGL was 19 months (range 12–44 months). Characteristics of these lesions are summarized in Table 2. Three patients with MGLs also had SGLs at diagnosis or at the first follow-up endoscopy. Three patients (17.6%) who had dysplasia as primary lesion developed a more advanced lesion (intramucosal carcinoma) during follow-up. MGLs were mostly located in the lower third of the stomach (76.5%). Close to two-thirds of MGLs (64.7%) were in the same stomach third as the primary lesion. Only one MGL needed surgical treatment because it did not meet the criteria for ESD, with all others being treated by ESD.

Risk Factors for Multiple Gastric Lesions

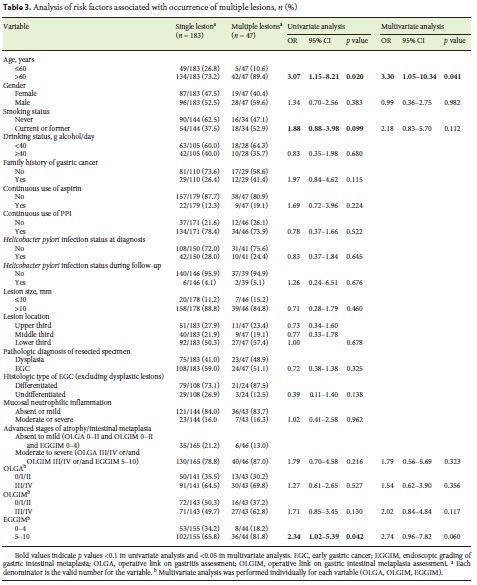

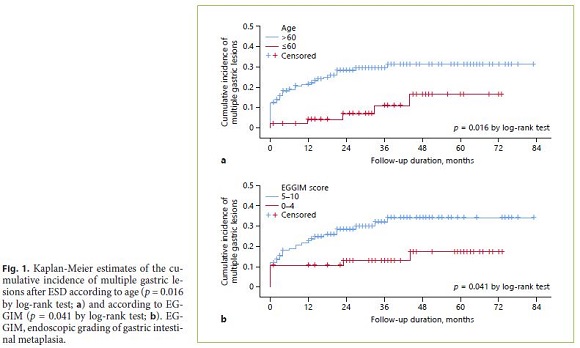

Age above 60 years (OR 3.07, 95% CI 1.15–8.21) was associated with multiple gastric lesions (Table 3). Advanced atrophic/metaplastic gastritis of the background mucosa (based on the combination of the 3 scores: OLGA III/IV or/and OLGIM III/IV or/and EGGIM 5–10) was not associated with higher risk of multiple lesions. However, higher EGGIM scores (5–10) were related with the development of multiple gastric lesions (OR 2.34, 95% CI 1.02–5.39). The presence of multiple lesions was also analyzed using Kaplan-Meier method for age (Fig. 1a) and EGGIM score (Fig. 1b). Patients over 60 years of age and patients with EGGIM 5–10 had multiple gastric lesions earlier. Current or former smoking status was more frequent on multiple gastric lesions group, although the difference was not statistically significant (52.9 vs. 37.5%, p = 0.099).

However, on multivariable analysis, only age above 60 years was found as an independent risk factor for multiple lesions (adjusted OR [AOR] 3.30, 95% CI 1.05– 10.34). EGGIM score 5–10 had an AOR of 2.74 for multiple gastric lesions (95% CI 0.96–7.82).

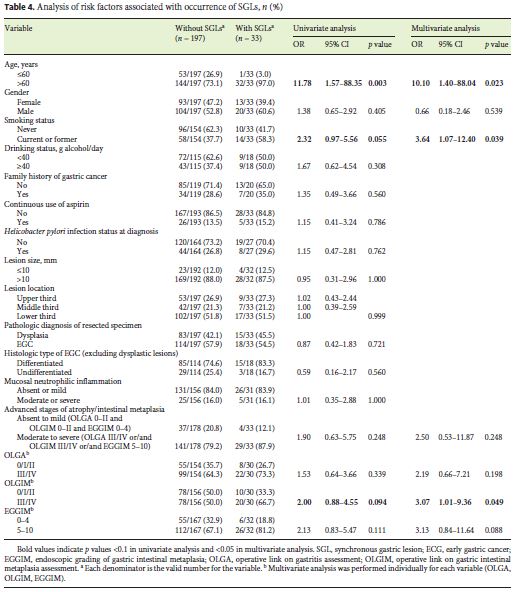

Risk Factors for SGLs

Univariate analysis (Table 4) revealed that age over 60 years (OR 11.78, 95% CI 1.57–88.35) was associated with the presence of SGLs. There was a tendency for current/ former smoking status (OR 2.32, 95% CI 0.97–5.56) and OLGIM stage III/IV (OR 2.00, 95% CI 0.88–4.55). Multivariate analysis showed that age over 60 years (AOR 10.10, 95% CI 1.40–88.04) and current or former smoking status (AOR 3.64, 95% CI 1.07–12.40) were independent risk factors. Chronic atrophic/metaplastic gastritis based on OLGA, OLGIM, and EGGIM scores was not associated with SGLs on univariate or multivariate analysis. However, OLGIM stage III/IV (AOR 3.07, 95% CI 1.01–9.36) was also an independent risk factor for SGLs.

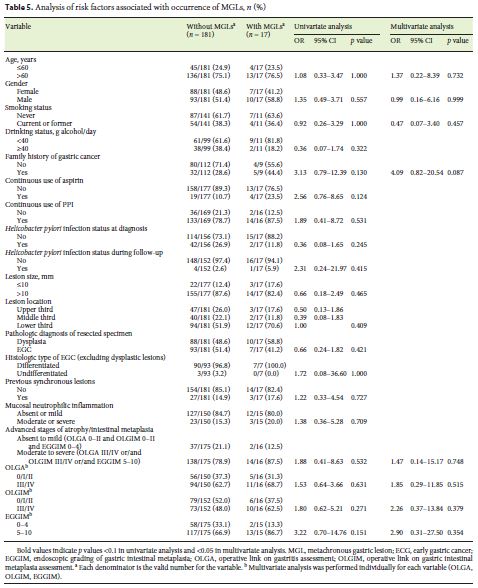

Risk Factors for MGLs

Univariate analysis (Table 5) did not show any factor associated with MGLs development. In the multivariate analysis, only family history of gastric cancer showed a trend toward greater risk for MGLs (AOR 4.09, 95% CI 0.82–20.54).

Discussion/Conclusion

The development of new endoscopic techniques and higher quality of endoscopy increased the diagnosis of EGC in recent years even in Western countries. These lesions can be treated with minimally invasive options like ESD, which is being increasingly used and is now recommended as the first-line treatment [7], since it preserves the stomach and has significant advantages on patients quality of life over surgical treatment [8]. ESD is also associated with shorter hospital stay and fewer complications compared to surgery [27]. Since endoscopic resection spares a large area of gastric mucosa, patients are at considerable risk of having SGLs and MGLs. Although there are several well-known factors associated with gastric cancer development [17], there are no established risk factors for these multiple gastric neoplasms in Western countries.

Factors associated with SGLs and MGLs after endoscopic resection have been previously studied in Eastern countries. However, to our knowledge, there are no studies in Western countries about the clinicopathologic characterization of patients with primary superficial gastric neoplasms and subsequent risk factors for multiple lesions, SGLs and MGLs.

Of all primary gastric lesions treated with ESD in this study, there was no clear gender tendency with male gender accounting for 53.9%. In Eastern countries, superficial gastric lesions were reported to be much more frequent in male gender (> 70%) [28–31]. A lower proportion of H. pylori infection at the time of diagnosis was reported in our study population (27.2%) compared with previous data description of percentages superior to 50% [28, 30, 32]. However, most of our patients were under surveillance because of gastritis and probably had previous H. pylori eradications. Furthermore, Giemsa coloration at histopathologic specimen was the diagnostic test used for H. pylori detection. This method has a lower sensitivity (83%) when comparing to immunohistochemistry and fluorescent in situ hybridization; this, together with the high prevalence of advanced stages of atrophy may have led to underestimation of the real prevalence of H. pylori infection [33]. Most of the lesions were in the lower third of the stomach, similarly to most studies [28, 29, 34–36].

The great majority (98.4%) of the patients had gastric atrophy or intestinal metaplasia, although a significant proportion had only mild gastric atrophy or focal intestinal metaplasia (32.6% were OLGA I/II, 44.1% OLGIM I/ II and 29.6% EGGIM 1–4), and these results are similar to those from Eastern populations [29]. Our results suggest that early gastric lesions in the Western population may appear equally in both sexes and in all stages of gastritis. This supports the recent European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy guidelines that recommend surveillance of some patients with only focal metaplasia [23]. Additional studies should evaluate which patients with initial stages of gastritis deserve endoscopic surveillance.

In our study, 14.3% of the patients had SGLs which is in line with Eastern series. Seo et al. [37] and Young Jang et al. [38] reported percentages of 14.5 and 12.9%, respectively. Of all SGLs, more than half (63.6%) were diagnosed previously or at the time of the ESD procedure. However, one-third of the SGLs was only detected in the first follow-up endoscopy, showing the importance of surveillance in the first months after ESD. This information supports the suggestion of European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy: a follow-up endoscopy 3–6 months after ESD and then annually for attempted detection of new lesions [7]. Pimenta-Melo et al. [39] suggested that a rigorous protocol for endoscopy can reduce the missed gastric lesions. This highlights the need for highquality endoscopy at diagnosis and even during ESD in order to detect and timely treat SGLs, perhaps at the same time of index ESD.

In our series, age over 60 years, current/former smoking status, and OLGIM stage III/IV were independent risk factors for SGLs. There are only a few studies regarding the clinical features associated with SGLs. According to our data, one study identified intestinal metaplasia in the background mucosa as a risk factor for SGLs [34] and previous reports associated older age with SGLs [14, 15]. Isobe et al. [15] described a significantly higher percentage of smokers in patients with SGLs when compared to patients without SGLs; however, smoking status was not found as an independent risk factor. In opposition to our results, Lim et al. [30] reported a primary tumor size of < 10 mm as a risk factor. Our results suggest that older patients, smokers, or former smokers and patients with advanced stages of gastritis have an increased risk of SGLs. In these scenarios, endoscopic evaluation should be particularly careful at the time of ESD, especially considering the higher anesthetic risk of older patients, so that SGLs can be diagnosed and resected at the same time if adequate and feasible.

In our study population, 8.6% of patients developed MGLs with a mean annual incidence of 3.1 per 100 patient- years. These results are in accordance with a recent review that reported incidences of MGLs after endoscopic resection of EGC from 2.7 to 15.6% and annual incidences of MGLs between 2.48 and 4% [16]. Abe et al. [40] reported 7- and 10-year cumulative incidence of MGL of 13.1 and 22.7%, respectively. Kato et al. [36] reported a constant incidence rate of MGLs development even after > 5 years after ESD, so surveillance for > 5 years was recommended. Cho et al. [41] described similar 10-year cumulative incidences of MGLs after endoscopic resection of HGD and EGC.

We did not find any factor independently associated with MGLs. Only family history of gastric cancer showed a tendency to increase the risk of MGLs. In accordance with our results, previous studies described an independent association of family history and MGLs development [29, 42]. Nevertheless, other risk factors were previously reported in Eastern series: older age [11, 31, 35, 38, 43]; male gender [34, 40, 44]; current smoking status [31]; severe gastric atrophy [43–45]; gastric intestinal metaplasia [30]; gastric body intestinal metaplasia [43]; and presence of previous SGLs [40, 46]. However, our results showed that primary gastric neoplasia did not have the same predominance in male gender as in Eastern series and this fact can modify the effect of gender in MGLs development. Although smoking status was not a risk factor in our study, Ami et al. [31] described that a lifetime consumption superior to 20 pack-years was independently associated with MGLs. Some patients in our series may have stopped smoking after the diagnosis of the primary lesion. This may justify the increased risk of smoking for SGLs and not for MGLs. Advanced stage of gastritis as a risk factor for MGLs was not confirmed in our study, even though it was a risk factor for SGLs (OLGIM III/IV) and a factor associated with multiple lesions (EGGIM > 4). Our data indicate that after the removal of all visible lesions, genetic factors (family history) may be the most important ones for secondary lesions. Nevertheless, given the high incidence of MGLs (3.1 per 100 patient-years), our results do suggest that all patients benefit from strict follow-up. It supports current guidelines that recommend annual endoscopy in this situation [7].

Several studies have attempted to determine whether the presence of H. pylori is associated with MGL [35, 42, 47–49]. Current evidence does suggest that H. pylori infection almost doubles the risk of a secondary gastric lesion [49–51]; eradication is recommended in all these patients. In our study, all patients underwent eradication, and only a minority had persistent infection despite treatment. So, it was not possible to determine the real risk of persistent H. pylori gastritis. However, it allowed the study of other factors independently of H. pylori status and no consistent risk factors were found. Again, our results do suggest that after endoscopic resection of all lesions (primary and SGLs) and after H. pylori eradication, the risk of a new lesion remains high. Moreover, the real protective effect of substances such as PPIs and aspirin should be evaluated in prospective randomized controlled trials since our study did not show any clear effect.

Some studies reported that new lesions tend to develop in the same third of the stomach and with the same histologic type as the primary lesion [30, 38, 52]. Our results showed that 64.7% of MGLs were in the same third as the primary neoplasm and 52.9% had an equal histologic type (dysplasia or EGC). Our study showed that primary lesions (51.7%), SGLs (54.5%), and MGLs (76.5%) are more frequently located in stomach lower third and this is in line with previous studies [41, 53]. This predilection can be attributed to the progression of gastric atrophy from the antrum to the body. It may also be explained by the initial antral location of H. pylori infection. Finally, the antral mucosa may be more susceptible to carcinogenesis than the remaining stomach mucosa.

Three patients with primary dysplastic lesions (2 HGD and 1 low-grade dysplasia) developed metachronous adenocarcinomas. This fact highlights the importance of following-up these patients.

Only one MGL needed surgical treatment because it did not meet the criteria for ESD (ulcerated undifferentiated- type gastric lesion), with all others being treated by ESD. This is in line with previous studies that reported that almost all the MGLs could be treated through to a new endoscopic procedure [38, 53].

This study has some limitations. First, it was performed in a single tertiary referral center, and it was designed retrospectively. Therefore, there are some missing data. Second, patients were only inquired about their smoking and drinking status at the moment of diagnosis and some patients may have stopped the consumption during follow-up.

Nevertheless, it has also a few strengths. It is the first study evaluating clinicopathologic characteristics of primary gastric neoplasia treated with ESD and defining subsequent risk factors for multiple gastric lesions in Western countries. Moreover, it is the first demonstrating that an EGGIM correlates with the risk of having > 1 lesion. In fact, for predicting multiple lesions, it was a risk factor more powerful than histologic staging, suggesting that, by quantifying metaplasia in all the gastric mucosa and not only in small biopsy fragments, it may be a better indicator of gastritis stage. However, since it was not possible to calculate EGGIM in every patient at the time of the diagnosis or ESD (in patients who performed ESD in 2012–2013, EGGIM was only calculated after 2 or 3 years), these results must be confirmed prospectively before firm conclusions can be made.

Future studies should evaluate the risk factors associated with SGLs and MGLs in a prospective way, with a higher number of patients and a longer follow-up time.

In conclusion, this study describes the characteristics of patients with primary gastric superficial lesions for the first time in a Western country. It suggests that surveillance limited to patients with advanced stages gastritis may miss some EGCs. Older age, current/former smoking, and OLGIM stage III/IV increase the risk of SGLs. Patients with these characteristics deserve a more careful follow-up endoscopy at the time of ESD. Older age increases the risk of multiple neoplasms. However, we did not find any independent risk factor for MGLs. Therefore, endoscopic surveillance after ESD should be done equally in all patients.

References

1 Bray F, Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Siegel RL, Torre LA, Jemal A. Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2018 Nov;68(6):394–424.

2 Isomoto H, Shikuwa S, Yamaguchi N, Fukuda E, Ikeda K, Nishiyama H, et al. Endoscopic submucosal dissection for early gastric cancer: a large-scale feasibility study. Gut. 2009 Mar;58(3):331–6.

3 Pyo JH, Lee H, Min BH, Lee JH, Choi MG, Lee JH, et al. Long-Term Outcome of Endoscopic Resection vs. Surgery for Early Gastric Cancer: A Non-inferiority-Matched Cohort Study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2016 Feb;111(2):240–9.

4 Chiu PW, Teoh AY, To KF, Wong SK, Liu SY, Lam CC, et al. Endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD) compared with gastrectomy for treatment of early gastric neoplasia: a retrospective cohort study. Surg Endosc. 2012 Dec;26(12):3584–91.

5 Lian J, Chen S, Zhang Y, Qiu F. A meta-analysis of endoscopic submucosal dissection and EMR for early gastric cancer. Gastrointest Endosc. 2012 Oct;76(4):763–70.

6 Park YM, Cho E, Kang HY, Kim JM. The effectiveness and safety of endoscopic submucosal dissection compared with endoscopic mucosal resection for early gastric cancer: a systematic review and metaanalysis. Surg Endosc. 2011 Aug;25(8):2666–77.

7 Pimentel-Nunes P, Dinis-Ribeiro M, Ponchon T, Repici A, Vieth M, De Ceglie A, et al. Endoscopic submucosal dissection: European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE) Guideline. Endoscopy. 2015 Sep;47(9):829–54.

8 Libanio D, Braga V, Ferraz S, Castro R, Lage J, Pita I, et al. Prospective comparative study of endoscopic submucosal dissection and gastrectomy for early neoplastic lesions including patients perspectives. Endoscopy. 2019 Jan;51(1):30–9.

9 Choi KS, Jung HY, Choi KD, Lee GH, Song HJ, Kim DH, et al. EMR versus gastrectomy for intramucosal gastric cancer: comparison of long-term outcomes. Gastrointest Endosc. 2011 May;73(5):942–8.

10 Nozaki I, Nasu J, Kubo Y, Tanada M, Nishimura R, Kurita A. Risk factors for metachronous gastric cancer in the remnant stomach after early cancer surgery. World J Surg. 2010 Jul;34(7):1548–54.

11 Libanio D, Pimentel-Nunes P, Afonso LP, Henrique R, Dinis-Ribeiro M. Long-Term Outcomes of Gastric Endoscopic Submucosal Dissection: Focus on Metachronous and Non-Curative Resection Management. GE Port J Gastroenterol. 2017 Jan;24(1):31–9.

12 Pimentel-Nunes P, Mourao F, Veloso N, Afonso LP, Jacome M, Moreira-Dias L, et al. Long-term follow-up after endoscopic resection of gastric superficial neoplastic lesions in Portugal. Endoscopy. 2014 Nov;46(11):933–40.

13 Ribeiro U Jr, Jorge UM, Safatle-Ribeiro AV, Yagi OK, Scapulatempo C, Perez RO, et al. Clinicopathologic and immunohistochemistry characterization of synchronous multiple primary gastric adenocarcinoma. J Gastrointest Surg. 2007 Mar;11(3):233–9.

14 Otsuji E, Kuriu Y, Ichikawa D, Okamoto K, Hagiwara A, Yamagishi H. Clinicopathologic characteristics and prognosis of synchronous multifocal gastric carcinomas. Am J Surg. 2005 Jan;189(1):116–9.

15 Isobe T, Hashimoto K, Kizaki J, Murakami N, Aoyagi K, Koufuji K, et al. Characteristics and prognosis of synchronous multiple early gastric cancer. World J Gastroenterol. 2013 Nov;19(41):7154–9.

16 Abe S, Oda I, Minagawa T, Sekiguchi M, Nonaka S, Suzuki H, et al. Metachronous Gastric Cancer Following Curative Endoscopic Resection of Early Gastric Cancer. Clin Endosc. 2018 May;51(3):253–9.

17 Van Cutsem E, Sagaert X, Topal B, Haustermans K, Prenen H. Gastric cancer. Lancet. 2016 Nov;388(10060):2654–64.

18 Dinis-Ribeiro M, Pimentel-Nunes P, Afonso M, Costa N, Lopes C, Moreira-Dias L. A European case series of endoscopic submucosal dissection for gastric superficial lesions. Gastrointest Endosc. 2009 Feb;69(2):350–5.

19 Rugge M, Meggio A, Pennelli G, Piscioli F, Giacomelli L, De Pretis G, et al. Gastritis staging in clinical practice: the OLGA staging system. Gut. 2007 May;56(5):631–6.

20 Capelle LG, de Vries AC, Haringsma J, Ter Borg F, de Vries RA, Bruno MJ, et al. The staging of gastritis with the OLGA system by using intestinal metaplasia as an accurate alternative for atrophic gastritis. Gastrointest Endosc. 2010 Jun;71(7):1150–8.

21 Pimentel-Nunes P, Libanio D, Lage J, Abrantes D, Coimbra M, Esposito G, et al. A multicenter prospective study of the real-time use of narrow-band imaging in the diagnosis of premalignant gastric conditions and lesions. Endoscopy. 2016 Aug;48(8):723–30.

22 Ono H, Yao K, Fujishiro M, Oda I, Nimura S, Yahagi N, et al. Guidelines for endoscopic submucosal dissection and endoscopic mucosal resection for early gastric cancer. Dig Endosc. 2016 Jan;28(1):3–15.

23 Pimentel-Nunes P, Libanio D, Marcos-Pinto R, Areia M, Leja M, Esposito G, et al. Management of epithelial precancerous conditions and lesions in the stomach (MAPS II): European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE), European Helicobacter and Microbiota Study Group (EHMSG), European Society of Pathology (ESP), and Sociedade Portuguesa de Endoscopia Digestiva (SPED) guideline update 2019. Endoscopy. 2019 Apr;51(4):365–88.

24 Dinis-Ribeiro M, Areia M, de Vries AC, Marcos-Pinto R, Monteiro-Soares M, OConnor A, et al.; European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy; European Helicobacter Study Group; European Society of Pathology; Sociedade Portuguesa de Endoscopia Digestiva. Management of precancerous conditions and lesions in the stomach (MAPS): guideline from the European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE), European Helicobacter Study Group (EHSG), European Society of Pathology (ESP), and the Sociedade Portuguesa de Endoscopia Digestiva (SPED). Endoscopy. 2012 Jan;44(1):74–94.

25 Malfertheiner P, Megraud F, OMorain CA, Gisbert JP, Kuipers EJ, Axon AT, et al.; European Helicobacter and Microbiota Study Group and Consensus panel. Management of Helicobacter pylori infection-the Maastricht V/Florence Consensus Report. Gut. 2017 Jan;66(1):6–30.

26 Dixon MF, Genta RM, Yardley JH, Correa P. Classification and grading of gastritis. The updated Sydney System. International Workshop on the Histopathology of Gastritis, Houston 1994. Am J Surg Pathol. 1996 Oct;20(10):1161–81.

27 Nishizawa T, Yahagi N. Long-Term Outcomes of Using Endoscopic Submucosal Dissection to Treat Early Gastric Cancer. Gut Liver. 2018 Mar;12(2):119–24.

28 Kang DH, Choi CW, Kim HW, Park SB, Kim SJ, Nam HS, et al. Location characteristics of early gastric cancer treated with endoscopic submucosal dissection. Surg Endosc. 2017 Nov;31(11):4673–9.

29 Yoon H, Kim N, Shin CM, Lee HS, Kim BK, Kang GH, et al. Risk Factors for Metachronous Gastric Neoplasms in Patients Who Underwent Endoscopic Resection of a Gastric Neoplasm. Gut Liver. 2016 Mar;10(2):228–36.

30 Lim JH, Kim SG, Choi J, Im JP, Kim JS, Jung HC. Risk factors for synchronous or metachronous tumor development after endoscopic resection of gastric neoplasms. Gastric Cancer. 2015 Oct;18(4):817–23.

31 Ami R, Hatta W, Iijima K, Koike T, Ohkata H, Kondo Y, et al. Factors Associated With Metachronous Gastric Cancer Development After Endoscopic Submucosal Dissection for Early Gastric Cancer. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2017 Jul;51(6):494–9.

32 Chung GE, Chung SJ, Yang JI, Jin EH, Park MJ, Kim SG, et al. Development of Metachronous Tumors after Endoscopic Resection for Gastric Neoplasm according to the Baseline Tumor Grade at a Health Checkup Center. Korean J Gastroenterol. 2017 Nov;70(5):223–31.

33 Kocsmar E, Szirtes I, Kramer Z, Szijarto A, Bene L, Buzas GM, et al. Sensitivity of Helicobacter pylori detection by Giemsa staining is poor in comparison with immunohistochemistry and fluorescent in situ hybridization and strongly depends on inflammatory activity. Helicobacter. 2017 Aug;22(4):e12387. [ Links ]

34 Moon HS, Yun GY, Kim JS, Eun HS, Kang SH, Sung JK, et al. Risk factors for metachronous gastric carcinoma development after endoscopic resection of gastric dysplasia: Retrospective, single-center study. World J Gastroenterol. 2017 Jun;23(24):4407–15.

35 Chung CS, Woo HS, Chung JW, Jeong SH, Kwon KA, Kim YJ, et al. Risk Factors for Metachronous Recurrence after Endoscopic Submucosal Dissection of Early Gastric Cancer. J Korean Med Sci. 2017 Mar;32(3):421–6.

36 Kato M, Nishida T, Yamamoto K, Hayashi S, Kitamura S, Yabuta T, et al. Scheduled endoscopic surveillance controls secondary cancer after curative endoscopic resection for early gastric cancer: a multicentre retrospective cohort study by Osaka University ESD study group. Gut. 2013 Oct;62(10):1425–32.

37 Seo JH, Park JC, Kim YJ, Shin SK, Lee YC, Lee SK. Undifferentiated histology after endoscopic resection may predict synchronous and metachronous occurrence of early gastric cancer. Digestion. 2010;81(1):35–42.

38 Jang MY, Cho JW, Oh WG, Ko SJ, Han SH, Baek HK, et al. Clinicopathological characteristics of synchronous and metachronous gastric neoplasms after endoscopic submucosal dissection. Korean J Intern Med (Korean Assoc Intern Med). 2013 Nov;28(6):687–93.

39 Pimenta-Melo AR, Monteiro-Soares M, Libanio D, Dinis-Ribeiro M. Missing rate for gastric cancer during upper gastrointestinal endoscopy: a systematic review and metaanalysis. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016 Sep;28(9):1041–9.

40 Abe S, Oda I, Suzuki H, Nonaka S, Yoshinaga S, Nakajima T, et al. Long-term surveillance and treatment outcomes of metachronous gastric cancer occurring after curative endoscopic submucosal dissection. Endoscopy. 2015 Dec;47(12):1113–8.

41 Cho CJ, Ahn JY, Jung HY, Jung K, Oh HY, Na HK, et al. The incidence and locational predilection of metachronous tumors after endoscopic resection of high-grade dysplasia and early gastric cancer. Surg Endosc. 2017 Jan;31(1):389–97.

42 Kim YI, Choi IJ, Kook MC, Cho SJ, Lee JY, Kim CG, et al. The association between Helicobacter pylori status and incidence of metachronous gastric cancer after endoscopic resection of early gastric cancer. Helicobacter. 2014 Jun;19(3):194–201.

43 Han JS, Jang JS, Choi SR, Kwon HC, Kim MC, Jeong JS, et al. A study of metachronous cancer after endoscopic resection of early gastric cancer. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2011 Sep;46(9):1099–104.

44 Mori G, Nakajima T, Asada K, Shimazu T, Yamamichi N, Maekita T, et al. Incidence of and risk factors for metachronous gastric cancer after endoscopic resection and successful Helicobacter pylori eradication: results of a large-scale, multicenter cohort study in Japan. Gastric Cancer. 2016 Jul;19(3):911–8.

45 Maehata Y, Nakamura S, Fujisawa K, Esaki M, Moriyama T, Asano K, et al. Long-term effect of Helicobacter pylori eradication on the development of metachronous gastric cancer after endoscopic resection of early gastric cancer. Gastrointest Endosc. 2012 Jan;75(1):39–46.

46 Arima N, Adachi K, Katsube T, Amano K, Ishihara S, Watanabe M, et al. Predictive Factors for Metachronous Recurrence of Early Gastric Cancer After Endoscopic Treatment. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1999 Jul;29(1):44–7.

47 Fukase K, Kato M, Kikuchi S, Inoue K, Uemura N, Okamoto S, et al.; Japan Gast Study Group. Effect of eradication of Helicobacter pylori on incidence of metachronous gastric carcinoma after endoscopic resection of early gastric cancer: an open-label, randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2008 Aug;372(9636):392–7.

48 Bae SE, Jung HY, Kang J, Park YS, Baek S, Jung JH, et al. Effect of Helicobacter pylori eradication on metachronous recurrence after endoscopic resection of gastric neoplasm. Am J Gastroenterol. 2014 Jan;109(1):60–7.

49 Choi IJ, Kook MC, Kim YI, Cho SJ, Lee JY, Kim CG, et al. Helicobacter pylori Therapy for the Prevention of Metachronous Gastric Cancer. N Engl J Med. 2018 Mar;378(12):1085–95.

50 Jung DH, Kim JH, Chung HS, Park JC, Shin SK, Lee SK, et al. Helicobacter pylori Eradication on the Prevention of Metachronous Lesions after Endoscopic Resection of Gastric Neoplasm: A Meta-Analysis. PLoS One. 2015 Apr;10(4):e0124725. [ Links ]

51 Bang CS, Baik GH, Shin IS, Kim JB, Suk KT, Yoon JH, et al. Helicobacter pylori Eradication for Prevention of Metachronous Recurrence after Endoscopic Resection of Early Gastric Cancer. J Korean Med Sci. 2015 Jun;30(6):749–56.

52 Nasu J, Doi T, Endo H, Nishina T, Hirasaki S, Hyodo I. Characteristics of metachronous multiple early gastric cancers after endoscopic mucosal resection. Endoscopy. 2005 Oct;37(10):990–3.

53 Nakajima T, Oda I, Gotoda T, Hamanaka H, Eguchi T, Yokoi C, et al. Metachronous gastric cancers after endoscopic resection: how effective is annual endoscopic surveillance? Gastric Cancer. 2006;9(2):93–8.

Statement of Ethics

The authors have no ethical conflicts to disclose.

Disclosure Statement

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Funding Sources

None.

* Corresponding author.

Gisela Brito-Gonçalves

Faculty of Medicine, University of Porto

Alameda Prof. Hernâni Monteiro

PT–4200-319 Porto (Portugal)

E-Mail gisela.goncalves@live.com.pt

Received: May 13, 2019; Accepted after revision: June 30, 2019

Author Contributions

G.B.-G., P.M., I.P., R.C., and I.S. contributed to the data collection.

D.L. contributed to the analysis and interpretation of data and reviewed the language and intellectual content of this work.

P.P.-N. and M.D.-R. contributed to the conception of this study, design, and final approval of this version to be published.