Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Acessos

Acessos

Links relacionados

-

Similares em

SciELO

Similares em

SciELO

Compartilhar

Media & Jornalismo

versão impressa ISSN 1645-5681versão On-line ISSN 2183-5462

Media & Jornalismo vol.20 no.37 Lisboa dez. 2020

https://doi.org/10.14195/2183-5462_37_1

ARTIGO

The Revolution in News That Nobody Named[1]

A Revolução nas notícias que ninguém nomeou

Michael Schudson*

* Columbia Journalism School Ms3035@columbia.edu

ABSTRACT

In 2020, both popular and academic discussions of journalism in the United States - and elsewhere in the world where journalism has been significantly influenced by the US model - have assumed that “objectivity” is the journalist’s guiding ideal. That assumption is not well founded. Along with Katherine Fink (2014) I have argued that in the US there was a dramatic transformation in news practice and news ideals beginning in the late 1960s and taking on an enduring place in journalism in the 1970s. Where in the 1950s and 1960s the “objectivity” model describes some 90% of front-page news stories in leading US newspapers, by the late 1970s it described only 40-50% of stories, the others better labeled “contextual” or “analytical” journalism. Others have made similar points about US journalism and still others have found comparable changes in various European journalisms.

Why have journalists and historians of journalism not understood this? How can we better grasp this transformation of modern professionalism from Professionalism 1.0 to Professionalism 2.0 - a powerful revolution that preceded the digital revolution? This essay seeks to explore these questions.

Keywords: objectivity; professionalism; US journalism

RESUMO

Em 2020, os debates correntes e académicos sobre o jornalismo nos Estados Unidos - e nos países em que foi significativamente influenciado pelo modelo norte-americano - assumiram que a “objetividade” é o ideal que orienta a atividade do jornalista. Mas essa assunção carece de fundamentação. No trabalho conjunto com Katherine Fink (2004), defendi que nos Estados Unidos ocorreu uma transformação dramática nas práticas e ideais jornalísticos, que teve início no final dos anos 60 e que se consolidou a partir da década de 1970. Se nos anos 50 e 60 o modelo da “objetividade” é aplicável a cerca de 90% das notícias de primeira página dos principais jornais norte-americanos, no final dos anos 70 adequa-se a apenas 40-50% das notícias, sendo que as restantes peças remetem para o chamado jornalismo “contextual” ou “analítico”. Outros autores chegam à mesma conclusão no que concerne ao jornalismo norte-americano e outros ainda encontram mudanças similares em vários países da Europa.

Por que razão jornalistas e historiadores do jornalismo não identificaram esta mudança? De que forma podemos compreender melhor esta transformação no âmbito do profissionalismo moderno, de um Profissionalismo 1.0 para um Profissionalismo 2.0 - uma revolução poderosa que foi anterior à revolução digital? Este ensaio procura dar resposta a estas questões.

Palavras chave: objetividade; profissionalismo; jornalismo norte-americano

In 2020, both popular and academic discussions of journalism in the United States assume that “objectivity” as a guiding value of American journalism is still practiced as well as preached. That assumption is not well founded, at least not if one means what counted as “objective” news coverage in the 1950s and 1960s. Katherine Fink and I have argued (2014) that in the US there was a dramatic transformation in news practice and news ideals beginning in the late 1960s that took on an enduring place in journalism in the 1970s. Where in the 1950s and 1960s the “objectivity” model describes some 90% of front-page news stories in leading US newspapers, by the late 1970s it described only 40-50% of stories, with the other half of the stories better labeled “contextual” or “analytical” journalism. Other researchers have made similar points about US journalism and still others have found comparable changes in various European journalisms.

This shift toward a deeper and richer journalism from a more “stenographic” jounalism, although abundantly documented, is barely noticed in the most familiar accounts by journalists and historians of journalism history. How can we better grasp this substantial transformation of contemporary professionalism that preceded the digital revolution? That is the question I ponder here.

Virtually all accounts by journalists and historians hold that in the United States news coverage of government, politics, and society opened up in the 1960s and 1970s. But why?

Was it the legacy of historical circumstance? Of the Vietnam War and Watergate and other moments where Americans learned that the highest reaches of national leadership made dangerous and devastating mistakes and could not be trusted? Yes, surely this broad disillusionment mattered. But other disillusionments had not. The way Senator Joseph McCarthy’s anti-communist hysteria entrapped journalists in the early 1950s did not transform journalism, nor did President Dwight Eisenhower’s lies about the American U-2 spy plane shot down over the Soviet Union in 1960. What made the response to the deceptions of the Kennedy, Johnson, and Nixon administrations over Vietnam different?

Something deeper was at stake. There was a generational change, a broad cultural change and a refashioning of how to understand democracy that all contributed to making the news media a chief agent in the opening up of American society. And I think the incorporation of an understanding of the shift from what we may think of as Objectivity 1.0 to the more analytically rich Objectivity 2.0 was overtaken by the overwhelming technological transformation of journalism in the digital era. How quickly that came to be seen as the story of our times!

The change in the media’s role 1970 to 1990s, before the digital revolution was very far along, before Facebook and Google and YouTube and so much more, was the joint product of several closely connected developments. Government - especially the federal government - grew larger and more engaged in people’s everyday lives; the culture of journalism changed and journalists asserted themselves more aggressively than before; and many governmental institutions became less secretive and more attuned to the news media, eager for media attention and approval. As the federal government expanded its reach (in civil rights, economic regulation, environmental responsibility, and social welfare programs like food stamps, Medicare, and Medicaid), as the women’s movement proclaimed that “the personal is political,” and as stylistic innovation in journalism proved a force of its own, the very concept of “covering politics” changed, too.

News coverage became more probing, more analytical, and more transgressive of conventional lines between public and private, but this recognizes only part of what made a changing journalism. Not only did the news media grow in independence and professionalism and provide a more comprehensive and more critical coverage of powerful institutions, but powerful institutions adapted to a world in which journalists had a more formidable presence than ever before. Of course, politicians had resented the press much earlier in American history - President George Washington complained about how he was portrayed in the newspapers; President Thomas Jefferson encouraged libel prosecutions in the state courts against editors who attacked him and his policies and President Theodore Roosevelt, a pioneer among presidents in manipulating journalists, famously castigated the negative tone of reporters he dubbed “muckrakers” (Levy, 1996, pp. 362-371; Schudson, 1998, p. 70; Goodwin, 2013, pp. 467-496). Even so, Washington politics was largely an insiders’ game. The Washington press corps was more subservient to the whims and wishes of editors and publishers back home than to official Washington and, in any event, politicians in Washington kept their jobs less by showing themselves in the best light in the newspapers than by maintaining their standing among their party’s movers and shakers in their home state. Members of the U.S. Senate were not popularly elected until 1914; before then, Senators were part of an insiders’ club remote from public opinion. And while in the early twentieth century a small number of writers at the most influential newspapers and a small number of syndicated political columnists came to be influential power brokers, the press as a corporate force did not have an imposing presence.

Media coverage of Congress in the 1950s and into the 1960s had been, as one contemporary gently called it, “overcooperative” (Matthews, 1960, p. 207). One reporter on Capitol Hill said (in 1956) that covering the Senate was “a little like being a war correspondent; you really become a part of the outfit you are covering” (Matthews, 1960, p. 214). Such politician-journalist collaboration did not happen every day but nor was it unusual. (Schudson, 2009, pp. 140-150). “Until the mid-1960s,” as Julian Zelizer, a leading historian of Congress simply observes, “the press was generally respectful of the political establishment” (Zelizer, 2007, p. 230).

The decline of this respect helped bring more attention to political scandal. Scandal reporting, frequently decried as a lowering of the standards of the press from serious coverage of issues to a frivolous and sensational focus on political sideshows, is nonetheless a symptom of a system that had become more democratic. As governing became more public (through the Freedom of Information Act in 1966, the Legislative Reorganization Act of 1970 bringing more “sunshine” to Congress, the National Environmental Policy Act of 1970 requiring federal agencies to provide and publicly release “environmental impact statements,” the campaign finance laws of 1971 and 1973, the Inspectors General Act of 1978, and other legislative milestones) politicians and government officers were more often held accountable (Schudson, 2015). The character of democracy shifted from one in which voters normally could express and act on disapproval of government incumbents only on election day to one in which, in Zelizer’s words, “the nation would no longer have to wait until an election to punish government officials, nor would it have to depend on politicians to decide when an investigation was needed” (Zelizer, 2007, p. 236). To some extent, the proliferation of scandals was made possible by the new information that political candidates were required by law to report or that legislation newly insisted that the executive branch of government make publicly available. More broadly, scandal reporting increased with the growing acceptance of values promoted by the women’s movement that blurred the line between public and private behavior or, to put it more strongly, demonstrated that that line had been an artificial and gendered construction all along.

Investigative reporting in and after the late 1960s increased, as popular history and personal recollections attest, but that increase is modest when measured as a percentage of all front-page news stories. More surprising, because less a part of how journalists picture their own past, is the growth of “contextual reporting.” Whether you call this interpretative reporting, depth reporting, long-form journalism, explanatory reporting, or analytical reporting, it grew (Forde, 2007, p. 230). In quantitative terms, it was easily the most important change in reporting in the past three quarters of a century up to the rise of online journalism - and surely shaped the directions that online journalism would take.

Over the past half century news stories grew longer; they grew more critical of established power; journalists came to present themselves publicly as more aggressive; and news reports offered more context for understanding the events of the day. Katherine Fink and I have summarized this research elsewhere and I will not detail it here (Fink and Schudson, 2013). But the evidence is clear and consistent. And lest one is tempted to look back nostalgically to an earlier era of journalism, one researcher, Carl Sessions Stepp, comparing ten mainstream metropolitan dailies from 1963-64 and 1998-99, wrote that the 1999 papers were “by almost any measure, far superior to their 1960s counterparts.” They were “better written, better looking, better organized, more responsible, less sensational, less sexist and racist, and more informative and public-spirited” (Stepp, 1999, p. 6).

Max Frankel, Washington bureau chief for the New York Times from 1968 to 1972 and the Times’ executive editor from 1988 to 1994, recalls a growing pressure in the 1960s to offer “something unique” that other news outlets did not provide. This meant more analysis or more of a “mood” piece like “’what France is up to’ or ‘what Hitler represents’ and so on.” This was acceptable even decades earlier for foreign correspondents, but rarely for national or local news reporters. Abe Rosenthal, managing editor of the paper in the 1970s and executive editor for most of the 1980s, liked to encourage good writing and practiced it himself in his days as a foreign correspondent. “He was a brilliant stylist,” Frankel has recalled, and master of “the socalled soft but significant lead.” As editor, Rosenthal was “very tolerant of well-written, correspondent-like stories even when they came from the Bronx. Not just from India.” Frankel recalls that in his own tenure as editor he was “insistent” in his effort “to get analysis into regular news stories.”[2]

News stories have grown more contextualized over time, less confined to describing the immediately observable here-and-now. In 1960 more than 90 percent of New York Times’ front-page stories concerning electoral campaigns were largely descriptive - but less than 20 percent by 1992, according to Thomas Patterson’s research (Patterson, 1993, pp. 82-83). Reporters took a more active part in their own stories, and not to the benefit of candidates for office.

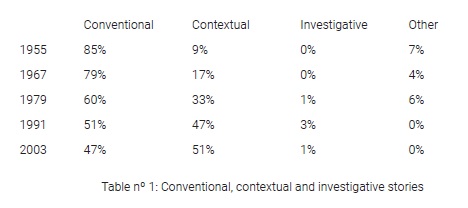

Katherine Fink and I added to this portrait an analysis of the content of three newspapers: the New York Times, the Washington Post, and the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel. We examined articles on the front pages of each newspaper over two weeks in the years 1955, 1967, 1979, 1991 and 2003, distinguishing conventional stories (event-centered information that addresses the who, what, when, and where of the event) from contextual stories (that emphasize “why” and provide information that the reporter judges to be part of the appropriate context for understanding the significance of the event at hand).

In our analysis, conventional stories often, though not always, focus on the official activities of government. This category includes stories about lawmaking and politics, but also public safety, such as court prosecutions, police crime reports, responses to fires, and natural disasters. A conventional story, however, is defined not by its subject matter but by its approach. Three features stand out. First, a conventional story identifies its subject clearly and promptly. Commonly, these stories answer the “who-what-when-where” questions in the lead paragraph or even the lead sentence. Also, commonly, the stories ignore or only implicitly address the “why” question. They tend to be written in the “inverted pyramid” style, with the most important information coming first.

Second, the conventional story describes activities that have occurred or will occur within 24 hours. One giveaway of a conventional story is a lead paragraph with the word “yesterday” or “today.” Contextual stories may focus on an occurrence of the past 24 hours but just as often may center on an event, action, or trend that runs over a longer time period or offers background for some trigger activity of the past day or two or three.

Third, conventional stories focus on one-time activities or actions - discrete events rather than long-term processes or sequences. Contextual stories, in contrast, tend to focus on the big picture, providing context or background for a topic of current interest. Where the conventional story is a well-cropped, tightly focused shot, the contextual story uses a wide-angle lens. It is often explanatory in nature, sometimes appearing beside conventional stories to complement the dry, just-the-facts versions of that day’s events. Contextual stories are often written in the present tense, since they describe processes and activities that are ongoing rather than events that have been both initiated and completed in the preceding hours or days. Alternatively, they may be written in the past tense, if their purpose is to give historical context.

Obviously, contextual stories are not all alike. They may be explanatory stories that help readers better understand complicated issues. They may be trend stories, using numerical data to show change over time on matters of public interest like high school graduation rates, population growth or unemployment. There are different ways to offer context; what all contextual stories share is an effort at offering accounts that go behind or beyond the “who-what-when-where” of a recent or unfolding event. The table below summarizes what Katherine Fink and I found overall across the samples we examined from the New York Times, Washington Post, and Milwaukee Journal over five time periods:

From 1979 on, it is clear that contextual journalism has had a major role in the newspapers, representing a third (and by 1991 a half) of the front page stories across the three papers. None of the papers is any longer committed only to the pared-down, just-the-facts “he said, she said” of the 1950s. Analysis has come to the fore - not partisan analysis but contextual information to help readers set the events of the day in a context that makes them comprehensible.

What brought this about? Yes, it was provoked by the Vietnam war and capped by Watergate. But it was also encouraged by a huge expansion of higher education and the centrality there of a “critical” or even “adversary” culture, and a broad rebellion

- around the world - against “the Establishment.” Journalism became less comfortable with its role as part of the Establishment. The habit of identifying with political insiders began to be embarrassing. The roles of “watchdog,” independent critics, and accountability warden became more congenial. The smug self-assurance of 1950s journalism has never entirely disappeared, but professionalism as a set of values now incorporates assumptions about a dividing line between politicians and journalists that was much less true in the 1950s and 1960s. Meg Greenfield, editorial page editor of the Washington Post in the 1970s, put this well in her memoir: “We, especially some of us in the journalism business, were much too gullible and complaisant in the old days. Just as a matter of republican principle, the hushed, reverential behavior (Quiet! Policy is being made here!) had gotten out of hand. It encouraged public servants to believe that they could get away with anything - and they did” (Greenfield, 2001, p. 89). In the 1950s and 1960s, journalists could be powerful, prosperous, independent, disinterested, public-spirited, trusted, and even occasionally adored by the powerful and the ordinary citizen alike. This state of ebullient health was sustained by a bipartisan Cold War political consensus and by the growing economic prosperity of news organizations. Neither would last, nor would the easy assumption that journalism could be simultaneously part of a governing establishment and independent from it. To cite Greenfield again: “The mystique had decreed that the people in charge in Washington knew best. They could make things happen if they wanted to. Almost all of them were acting in good faith. And they were entitled to both privacy and discretion to do what they judged necessary for the nation’s well-being.” Those blithe assumptions, borne on the wings of World War II and the Cold War to follow, crashed in Vietnam.

The new, more analytical journalism - Objectivity 2.0 - dominates journalism today. But it insists - I think correctly - that it is still rooted in a commitment to presenting the verified facts at hand. Might there be a mode of professionalism yet to come that goes beyond objectivity altogether?

I hope not. The professionalism my colleagues teach at Columbia Journalism School and that is still taken seriously at hundreds of newsroom across the country and taught at scores of journalism schools insists that students learn to report “against their own assumptions.” If you believe strongly in pro-choice and you are assigned to write about the pro-life movement, and you are charged with understanding the prolife position and why pro-lifers hold it, your task is to represent the position and the people fairly and accurately. In 2016 it was the New York Times, not Fox News, not Breitbart News, that broke the story that Hillary Clinton as Secretary of State used a private server for emails, including confidential State Department communications. The Times is a professional Objectivity 2.0 news organization. It follows the story, not its own or their publisher’s or their editorial page editor’s preferences.

If there is an Objectivity 3.0 around the corner, it may call for public disclosure of some aspects of journalists’ backgrounds and qualifications, but this would not work without a public understanding that has not been secured - that disclosure is not disqualification. Can reporters cover controversial Facebook policies if they are not on Facebook? Would it be worse if they are on Facebook? Can you cover the auto industry in Detroit if you drive a Japanese car? Would that bias you in a way to disqualify you? Or would it be driving a Detroit-made car that would bias you? Can a Jew or a Mormon cover news of the Pope? Can a man cover a story about abortion fairly? Or a woman who has had an abortion? Or a woman who has not? These are not frivolous questions in a time of identity politics, but they will not move anyone toward full disclosure as a new standard for a professional ethic in journalism. I think journalism straddles an abyss between binding itself in a straitjacket of “nothing but the facts” and a premise of sensible interpretative and contextual reporting that stops well short of partisan advocacy.

What I do see is that Objectivity 1.0 - due regard for fact-based reporting - is part of what journalists do, but Objectivity 2.0 accepts also the need to structure reports so that the audience is equipped with sufficient context to comprehend them. Sometimes this may subordinate the central necessity of the factual reporting, but it does not bury it. Objectivity 3.0, if it is to emerge, must acknowledge both the requirements of reporting and the needs of telling a comprehensible story. Journalism that remains reliably professional must be “evidence-based” at heart. And it cannot shear off the advances that analysis and investigation, as emphasized in Objectivity 2.0, have contributed. But an Objectivity 3.0 might add to this an objectivity of empathy. Think of the contradiction at the heart of what physicians do. Doctors are both people who are trained in the sciences and people who are trained to be healers. They follow practices dictated by science and at the same time they engage in practices based on the unique persons who present themselves as patients. The genius of great doctors (or so it seems to me) is that they do both at once without denying either. Their knowledge is both schooled and clinical. They live off of both textbooks and techniques they can articulate and clinical judgment that no algorithm has yet captured. Doctors need not deny either part of themselves in their task of healing.

Similarly, journalism practiced with Objectivity 3.0 should accept that the job of journalism is to report stories about contemporary life. By reporting, journalists make a commitment to a factual and to a large extent verifiable world. By turning reports into stories, they give their reporting a form that makes them understandable, even compelling. Reports in story form have a point. They are not just transcripts. They combine reportage and story that not only informs and instructs but may touch people, even move them. And to do that, the reporters must seek to place themselves in the positions of the people about whom they write. This is not a matter of sentimentality but of a further depth in standing aside from one’s own standpoint.

Is that impossible? Can reporters bracket their own standpoints in the quest to get at someone else’s? It’s not easy and it cannot ever be fully done, but people do something like it all the time. A parent advising a child, a teacher counseling a student, a nurse a patient, a friend a friend are all capable of saying, “If I were in your shoes….” That is an act of empathic objectivity - and what that might mean in journalism in an era in which we are so strongly encouraged to express ourselves is worth considering. Journalism is in part a discipline of not expressing, of setting self-expression temporarily aside, exchanging it for reportorial honesty and empathy. I hope that is what journalism will learn to affirm.

BIBLIOGRAPHY REFERENCES

Fink, K., & Schudson, M. (2013). The Rise of Contextual Journalism 1950s-2000s. Journalism: Theory, Practice and Criticism, 15(1), 3-20. DOI: 10.1177/1464884913479015 [ Links ]

Forde, K. R. (2007). Discovering the Explanatory Report in American Newspapers. Journalism Practice, 1(2), 227-244. DOI: 10.1080/17512780701275531 [ Links ]

Goodwin, D.K. (2013). The Bully Pulpit: Theodore Roosevelt, William Howard Taft, and the Golden Age of Journalism. New York: Simon & Schuster. [ Links ]

Graves, L., personal communication, February 24, 2009

Greenfield, M. (2001). Washington. New York: Public Affairs. [ Links ]

Levy, L. W. (1996). Freedom of the Press from Zenger to Jefferson. Durham, N.C.: Carolina Academic Press. (Original work published 1966)

Matthews, D.R. (1960). U.S. Senators and Their World. New York: Vintage Books. [ Links ]

Patterson, T. (1993). Out of Order. New York: Knopf. [ Links ]

Schudson, M. (1998). The Good Citizen: A History of American Civic Life. New York: Free Press. [ Links ]

Schudson, M. (2009). Persistence of Vision: Partisan Journalism in the Mainstream Press. In Carl F. Kaestle and Janice A. Radway (Coords.), A History of the Book in America: Volume 4: Print in Motion: The Expansion of Publishing and Reading in the United States, 1880-1940 (pp. 140-150). Chapel Hill, N.C.: University of North Carolina Press.

Schudson, M. (2015). The Rise of the Right to Know: Politics and the Culture of Transparency 1945-1975. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Schudson, M. (2018). Why Journalism Still Matters. Cambridge, UK: Polity Press. [ Links ]

Stepp, C. S. (1999). State of the American Newspaper Then and Now. American Journalism Review, 21(7), 6. [ Links ]

Zelizer, J. E. (2007). Without Restraint: Scandal and Politics in America. In M. C. Carnes, The Columbia History of Post-World War II America. New York: Columbia University Press. [ Links ]

Biographical note

Michael S. Schudson is professor of journalism in the graduate school of journalism of Columbia University and adjunct professor in the department of sociology. He is professor emeritus at the University of California, San Diego. He is an expert in the fields of journalism history, media sociology, political communication, and public culture.

Email: Ms3035@columbia.edu

Address: Columbia University Graduate School of Journalism. Pulitzer Hall, MC 3801 2950 Broadway New York, NY 10027

Article by invitation/ Artigo por convite

[1] This essay results from an adaptation of some chapters of the book of Michael Schudson, Why Journalism Still Matters (Cambridge, UK: Polity Press, 2018).

[2] Lucas Graves, unpublished interview with Max Frankel, Feb 24, 2009, transcript in my possession.