Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Accesos

Accesos

Links relacionados

-

Similares en

SciELO

Similares en

SciELO

Compartir

e-Pública: Revista Eletrónica de Direito Público

versión On-line ISSN 2183-184X

e-Pública vol.6 no.1 Lisboa abr. 2019

DIREITO PÚBLICO

Austerity measures and their impact on Human Rights

The interaction between the European Court of Human Rights and the European Committee of Social Rights

O impacto das medidas de austeridade nos Direitos Humanos

A Interação do Tribunal Europeu dos Direitos Humanos com o Comité dos Direitos Sociais

Hugo Oliveira Evangelista I 1 , Marta Prata Domingos II 1 .

I Faculdade de Direito da Universidade de Lisboa, Alameda da Universidade - Cidade Universitária, 1649-014 Lisboa - Portugal. E-mail:h.m.oliveira.evangelista@studen.rug.nl

II Faculdade de Direito da Universidade de Lisboa, Alameda da Universidade - Cidade Universitária, 1649-014 Lisboa - Portugal. E-mail:marta.prata.domingos@gmail.com

ABSTRACT

Over the past years, the expressions “austerity measures”, “economic crisis” and “troika” have been frequently used in the conversations of most European citizens. Now that most of the countries seem to have rebuilt their economies, we would like to understand the extent of the collateral damages. In this paper, we will be analysing the impact of the adoption of austerity measures on human rights issues. In order to reach this goal, we will be analysing three different cases (the first one was decided by the European Committee of Social Rights, and the others by the European Court of Human Rights). All cases are related to the austerity measures used in Greece and in Portugal at the time of the economic crisis. Drawing on official reports and on previous literature, we have concluded that the austerity policies have had a deep repercussion on human rights. However, that impact can be contained. In a second stage, we have explored the relationship between the two aforementioned institutions and observed that they complement each other, notwithstanding the fact that a lot of work still needs to be done to optimise that interaction, in order to guarantee greater protection to human rights.

Keywords: Austerity Measures – European Court of Human Rights – European Committee of Social Rights – Interaction – Social Security.

RESUMO

Nos últimos anos as expressões “medidas de austeridade”, “crise económica” e “troika” têm sido frequentemente usadas nas conversas da maioria dos cidadãos europeus. Agora, que a maioria dos países parece ter conseguido reconstruir as suas economias, gostaríamos de perceber a extensão dos danos colaterais provocados pelas medidas de austeridade adotadas. Ao longo deste artigo analisaremos o impacto causado em matéria de direitos humanos. Para alcançar este objetivo foram analisados três casos, o primeiro decidido pelo Comité Europeu dos Direitos Sociais, e o segundo e terceiro pelo Tribunal Europeu dos Direitos do Homem. Todos os casos dizem respeito à adoção de medidas de austeridade na Grécia e em Portugal aquando da crise económica de 2009. Com base em relatórios oficiais e em diferentes posições doutrinárias, concluímos que a adoção de medidas de austeridade teve repercussões profundas nos direitos humanos. Não obstante, esse impacto pode ser contido. Numa segunda etapa deste artigo, exploramos a relação entre as duas instituições acima mencionadas e a forma como se complementam, embora muito trabalho tenha de ser feito para fomentar a interação e assim garantir uma maior proteção dos direitos humanos.

Palavras-Chave:Medidas de Austeridade – Tribunal Europeu dos Direitos do Homem – Comité Europeu dos Direito Sociais – Interação – Segurança Social.

Summary: 1. Introduction, 2. The Greek Course of Events, 2.1. I.S.A.P. v. Greece, 3. The Portuguese Circumstances, 3.1. Da C. Mateus and S. Januário v. Portugal, 3.2. Da Silva Carvalho v. Portugal 4. The Outcome, 5. Conclusion.

Sumário: 1. Introdução, 2. O Curso de Acontecimentos na Grécia, 2.1. I.S.A.P. c. Greece, 3. As Circunstâncias Portuguesas, 3.1. Da C. Mateus e S. Januário c. Portugal, 3.2. Da Silva Carvalho c. Portugal 4. O Resultado, 5. Conclusão.

1. Introduction

In 2008, after the bankruptcy of the American investment bank, Lehmann Brothers, the ongoing financial and economic crisis in the U.S. reached its peak, resulting in harmful effects to the global economy, especially in the South European countries. Due to their more vulnerable economies, some of these countries felt the need to seek assistance from the European Union institutions, in order to tackle what gradually became a sovereign debt crisis. Two of the most affected countries in these circumstances were Greece and Portugal.

Regarding Greece, this economic recession would aggravate an existing national debt crisis. In 2010, the Greek government officially requested a bailout from “Troika” (as it would later be designated), a group composed by the European Commission, the European Central Bank, and the International Monetary Fund.

The Portuguese administration ended up requiring financial assistance from this group in 2011, due to the stagnation of economic growth at the beginning of the twenty-first century, and the subsequent credit debt caused by the excessive allocation of loans.

This kind of financial help is always followed by some provisions designed to reduce expenditure and increase revenue in the form of austerity measures, such as: the deployment of structural reforms to unfit schemes, more severe combat to fiscal evasion, the implementation of new taxes and the increase of the already existing ones (as the VAT).

By virtue of its importance, in the present study we will be focusing our attention on the changes made by the Greek and Portuguese governments to their social security schemes.

Social security was first recognised as a fundamental human right by the United Nations Declaration of Human Rights (1948), and by the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (1966)2. The latter was considered an important milestone, as it was the first document to implement the general principles of social security as a state responsibility. In 1952, the International Labour Organization (ILO) had already laid down the minimum standards of social security.3

For all of the above reasons, we will be analysing the possible impact of the austerity measures adopted by the governments, implementing and protecting universal human rights. In other words, is it possible that the need to make cutbacks in public spending constitutes a threat to human rights? If so, does the end justify the means?

In order to answer this question, we will be looking into three specific cases, comparing the decisions made and the criteria used. In the case “Pensioners’ Union of the Athens-Piraeus Electric Railways (I.S.A.P.) vs. Greece (Complaint n. 78/2012)”4 decided by the European Committee of Social Rights, “António Augusto DA CONCEIÇÃO MATEUS against Portugal and Lino Jesus SANTOS JANUÁRIO against Portugal (Applications nos. 62235/12 and 57725/12)”5, and “Maria Alfredina Da SILVA CARVALHO RICO against Portugal (Application n. 13341/14)”6, decided by The European Court of Human Rights.

Although the cases being examined have a common background and deal with similar problems, we are well aware of the fact that they are decided by two different bodies, and that will necessarily lead to different lines of reasoning since they are based on different legal instruments, each of them with different purposes. However, we examine the contact points between the two structures and see if they take advantage of their similarities in order to improve the protection of human rights.

Therefore, at a second stage in this article, we will try to answer the following questions: are there enough bridges of communication between the two bodies? Is there enough convergence in cases related to the protection of human rights in austerity situations to consider that there might be some harmony between the ECSR’s and the ECHR’s rulings? Are their differences working as obstacles to a deeper alignment and to an exchange of knowledge, not allowing for a wider and stronger protection of human rights? That being said, we are knowledgeable of the progresses made by the two institutions in that respect, in cases related to other matters7. Bearing that in mind, it is only fair if we compare those advances with the situations at hand.

2. The Greek Course of Events

After two enormous bailouts, the situation in Greece changed dramatically, though not as expected.

Even before the first intervention of the European institutions, the Greek government had already adopted measures to reduce public expenditure and increase public revenue. The first set of policies included cuts in salaried bonuses, recruitment freeze, increase in the VAT (from 19% to 21%) and excise taxation (fuel, cigarettes and alcohol), and public investment cutbacks. Regrettably, these were insufficient. Therefore, in May 2010, Greece signed the first Memorandum of Understanding (MoU)8.

With the endeavours of the Troika, stricter laws were applied. The 13th and 14th salaries (bonuses) were limited or completely eliminated for high-wage earners, the VAT was once again increased (to 23%), taxes on luxury consumption, property and business profits were also raised. As far as pensions are concerned, the retirement age was raised from 60 to 65 years, penalties were introduced for early retirement, payments were suspended for the still employed pensioners with less than fifty-five years, and reduced to 70% for the older ones.

A second batch of measures was adopted in June 2011, and again in August 2011 bringing more cuts, increasing property taxes, and decreasing the tax-free income allowances (minimum income).

At the beginning of 2012, a second Memorandum had to be signed, which brought about further austerity measures. More pension and other social benefits cutbacks were made, and the 13th and 14th salaries ended up being completely abolished9.

This cycle of requests for help and the implementation of austerity measures continued. In 2015, with the goal of strengthening its position in the negotiation of a third economic adjustment programme, the Greek administration called for a referendum which asked for its citizens’ opinion on whether they accepted the draft agreement presented by the Troika. The population voted overwhelmingly against the proposal (61,3%). Despite this result, the offer was accepted eight days later.

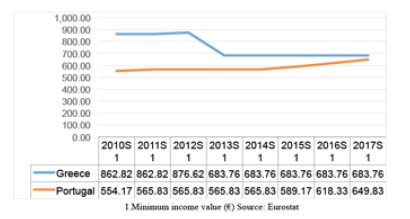

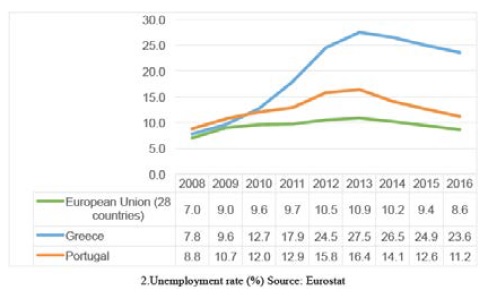

Possibly as a result of these continued policies, Greek society went through a deterioration of its life quality. This statement is based on the acknowledgement of the fact that the unemployment rate in Greece rose when the first austerity measures were implemented, the minimum wage was frozen since it had first been reduced by 22%, at the time of the second economic adjustment programme in 201210.

2.1. I.S.A.P. v. Greece

In the case “Pensioners’ Union of the Athens-Piraeus Electric Railways (I.S.A.P) vs Greece,” decided by the European Committee of Social Rights in 2012, the complainant claimed that the regulations introduced by the Greek government between May 2010, and November 2012, violated the articles 12§3 and 31§1 of the 1961 European Social Charter (the Charter). Article 12§3 stipulates that the contracting state is responsible for ensuring that he will make efforts “to progressively raise the system of social security to a higher level”. In what concerns article 31§1, it declares that any restriction or limitation imposed to the effectively realised rights prescribed in the Charter must be authorised by law, and necessary to protect rights and freedoms of others or the public interest, national security, health or morals.

According to the Committee, the complaint is only admissible as far as Article 12 is concerned, since Article 31§ “cannot be directly invoked as such, only providing a reference for the interpretation of substantive rights provisions of the Charter”11. The Committee goes further by stating that the alleged elements lead to a violation, not only of the third section of article 12, but also of its second section, where it is established that signers must “maintain the social security system at a satisfactory level, at least equal to the required for ratification of the International Labour Convention (n.102), concerning minimum standards of social security”.

In short, the Union complains that pension cuts made by the Greek government have caused a deterioration of the pensioners’ situation. A significant reduction has been made to the three bonuses, namely Christmas (from a month salary to 400), Easter, and holiday bonuses (from a half a month salary to 200), when the pensioner is over 60 years old. On the other hand, when the pension (bonuses included) exceeds 2500, or when the pensioner is younger than 60 years old, the bonuses are not paid12 at all. Primary and auxiliary pension payments were suspended or drastically reduced, early retirees having been the most affected13 by this measure. On the whole, pensions were reduced six times. A pensioners’ solidarity contribution was introduced to all pensions amounting to 1400 or more.

To conclude, the Union argues that the above-mentioned measures constitute a violation of article 12 of the 1961 Charter, as they do not respect the principles of proportionality and necessity. In addition, it also states that these policies are not the most suitable to achieve the goals intended by the government. This argument can end up being a powerful one in this accusation supported by the criteria set up by The Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights, concerning the adoption of austerity measures14. This method establishes that States should demonstrate “the necessity, reasonableness, temporariness and proportionality of the austerity measures; the exhaustion of alternative and less restrictive measures”15.

The complainant also invokes the case-law of The European Court of Human Rights in which it is clarified that the rights protected by The European Convention on Human Rights (the Convention), may not be constrained in a way that the provision of pension benefits is discontinued without balance between public interests and the protection of human rights.

The government contested the allegations, basing its justification on the need to adopt the aforementioned measures to face the economic and social situation that the country was going through, as a prerequisite for the loan granted by the Troika.

In its statement of grounds, the Committee made reference to the opinion of other international and national bodies as the ILO and The European Court of Human Rights. The ILO reported that in September 201116, the rate of pension replacement had not dropped below the levels set by Convention n.102, although, at the time, 20% of the population was facing the risk of poverty.

As for the Court, the Committee refers to the repeated understanding of that institution as regards the safeguard of the peaceful enjoyment of possessions, in line with Protocol No 1 to the European Convention on Human Rights (Article 1 of Protocol n.1 to the Convention)17.

The Committee concludes its decision by explaining that reductions in benefits do not automatically constitute a violation of Article 12. It is at the State’s discretion to change their social security system. Nevertheless, those modifications should never affect the minimums required to “maintain a sufficient level of protection for the benefit of the most vulnerable members of the society.” Since the Greek government, by accumulation of measures, did not guarantee that protection, nor did it exhaust their alternative measures, the Committee declared that there was a violation of Article 12§3 of the 1961 Charter, writing a brief note suggesting the existence of more suitable mechanisms to address a complaint regarding the pensioners’ right to property (possibly referring to the Court).

3. The Portuguese Circumstances

When we examine the situation in Portugal, upon signature of the Memorandum of Understanding, the austerity measures appear to have produced the effects desired.

The measures were similar to the Greek ones, although they variated in intensity and, in contrast to Greece, they did not endanger the most vulnerable groups. As part of the rescue plan the, government agreed to a 4.7 billion euros cut to public expenditure by 2014, with a special focus on health care, education and social security18. From the package of more than 220 austerity policies, we will be focusing on cuts in pensions (with particular emphasis on the cuts in various bonuses), and the introduction of the solidarity-based special contribution. Even though the bailout prerequisites were already quite demanding, the government went further and applied additional austerity measures, requiring an additional effort to meet the goals sooner than expected.

One of the most important measures required by the Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) was the reduction in pensions above 1500, with progressive rates. Pensions were to be reduced at an average rate of 5% and a 10% extraordinary solidarity contribution tax was applied to pensions above 5000. Afterwards, the Portuguese administration changed their minds with regard to the pensions between 1500 and 5000, and planned to replace the cuts made in those with cutbacks in the Christmas and holidays bonuses. In addition, in 2014 the retirement age was raised from 65 to 66 years old.

During the first two years of the programme for economic adjustment, the unemployment rate increased 3,5%, reaching its highest recorded level (16,4%) since 2008. On the other hand, the amount of money spent on pensions kept rising. Over the four years of the programme’s length, the minimum wage was frozen at 565,8319.

3.1 Da C. Mateus and S. Januário v. Portugal

Regarding the case “António Augusto DA CONCEIÇÃO MATEUS against Portugal, and Lino Jesus SANTOS JANUÁRIO against Portugal” (Applications n. 62235/12 and 57725/12), decided upon by the European Court of Human Rights, the complainants, as public sector pensioners eligible to receive benefits under the social security scheme, claimed that there had been a breach of their right to the protection of property, due to the reduction of their holiday and Christmas subsidies in 2012.

According to the 2012 State Budget Act, designed to implement the MoU, the holiday and Christmas subsidies or equivalent benefits received by the pensioners would be reduced.

In this particular case, the reductions amounted to a cumulative loss of 1102,4, when referring.to.the.first.applicant,.and.to.1368,04. for.the.second.one.

Months after the enforcement of this measure, a group of the Parliament members challenged its constitutionality, claiming that it violated the principle of equality as well as the right to social security. The Constitutional Court concurred, recognising the violation of the principle of proportional equality, stating: “it is evident that the difference in treatment of people receiving income and pensions from public funds [and that of other citizens] is excessive”. Despite this compromise, due to the advanced stage of implementation of the 2012 State Budget Act, cancelling that rule would mean the failure of complying with the MoU goals, making it impossible to find an alternative strategy to accomplish the same results in the time available. With this in mind, the Constitutional Court decided to suspend the implementation of its own decision, suggesting that the rule be applied in.2012.

The European Court of Human Rights analysed the applications in light of Article 1 of Protocol n.1 to the Convention, which protects the peaceful enjoyment of property. According to its content, no one can be deprived of their possessions unless public interest is at stake, and it can only be done in conditions provided by the law, and by the general principles of international law. However, this cannot jeopardise the State’s need “to control the use of property in accordance with general interest or to secure the payment of taxes or other contributions or penalties”.

The applicants claimed that there was a violation of their right to the protection of property, due to the reduction in their Christmas and holiday bonuses for 2012. The Court argued that article 1 of Protocol n.1 does not guarantee the right to owning property, and it cannot be interpreted as protecting the entitlement to a pension of a certain amount. Nevertheless, if the State has legislation that establishes the payment of a pension as a fundamental right, then it must be interpreted as creating a property interest protected by Article 1. Therefore, its reduction or elimination needs to be justified.

In the present case, as the complainants were entitled to receive holiday and Christmas bonuses as they usually did, it is considered that there is a proprietary interest falling within the scope of the previously mentioned article. Despite this fact, the Court holds that the cuts were adopted as an exceptional measure to pursue a public interest justified by the need to reduce public expenditure.

When providing an explanation for the latter, the Court cites as an example the adoption of similar measures in Greece, so as to draw a clear distinction between the latter and the measures being challenged in the present case. Unlike Greece, Portuguese law had a transitory nature (only applicable from 2012 to 2014). Thus, the cuts were limited in time and in quantitative terms.

Taking this into account, the court considers that, due to the fact that there was no affectation of the basic pension value, and the measures had limited reach, they did not configure a disproportionate or excessive burden.

3.2 Da Silva Carvalho v. Portugal

The main concern in the lawsuit “Maria Alfredina Da SILVA CARVALHO RICO against Portugal (Application n. 13341/14)” is the application of the extraordinary solidarity contribution (CES - contribuição extraordinária de solidariedade).

Upon the signature of the MoU in 2011, the CES’s scope of application was extended in the 2013 State Budget Act in order to tax pensions above 1350 as well. As a result, the complainant lost 4,6% of her annual social security benefits, corresponding to a total amount of 1286,88. The time period estimated for the application of this measure was only one year.

In the 2014 State Budget Act, the CES was reintroduced in the same conditions as the one in 2013. Moreover, a few months later the measure was amended to include pensions above 1000, and the rates applied were increased.

The applicant claimed that the alterations made in 2014 to the CES regime constituted a violation of Article 1 of Protocol 1 and to the Articles 13 and 14 of the Convention. An important part of Ms.SILVA CARVALHO RICO’s argumentation was that the CES was no longer a temporary measure, since it had been applied for two consecutive years.

The legality of this rule had already been challenged in 2013 before the Constitutional Court by the President of the Portuguese Republic at the time, Aníbal Cavaco Silva, who questioned the observance of the principle of equality, proportionality and protection of legitimate expectations. The Court disagreed, arguing that it was not excessive or disproportionate, once it was exceptional and had a transitory nature.

At the time of the measure’s amendment, in March 2014, a group of Portuguese Parliament members challenged the rule’s constitutionality again, considering that it was no longer temporary, nor exceptional. Responding to this argument, the Court held by its 2013 decision, establishing that the CES law was still within the limits of reasonableness, and maintaining its characteristics of exceptionality and transience, since the situation that had led to its implementation remained unaltered. According to the Constitutional Court’s jurisprudence “a State cannot be forced to comply with its obligations within the framework of social rights if it does not possess the economic means to do so20”, this is known as “proviso of the possible”.

The Court explains the application of Article 1 of Protocol 1 by mentioning the case Da Conceição Mateus and Santos Januário v. Portugal, and identifying the three basic conditions that a measure has to fulfil regarding the restraint of the peaceful enjoyment of possessions: 1) must be subject to the conditions provided by law (lawfulness of the interference); 2) needs to be in the public interest; 3) has to guarantee a balance between the owner’s right and the community interests (proportionality).

Regarding the first condition, the Court based its response on the Constitutional Court’s argumentation, therefore considering that this requirement was satisfied. Secondly, as for the pursuit of the public interest, it was assumed that the Portuguese economic situation, combined with the transient nature of the norm, justified the use of the CES. As for the proportionality requisite, the Court draws a picture of the country’s situation of need that justified this kind of measures, and as the deprivation of income was not substantial, the Chamber considers that a balance was achieved. Once all the prerequisites were fulfilled, the reapplication of the CES was deemed legitimate.

4. The Outcome

Looking at the previously examined cases, we can observe some similarities in the measures adopted by the two countries.

Regarding the bonuses, in 2012 the Greek pensioners under sixty years old suffered a suspension of the payment of their subsidies, except for the disabled, the widowed, and people with less than 18 years old or 24, if they are students. Pensioners over 60 years of age had their Christmas bonuses reduced to 400, and their Easter and vacation subsidies lowered to 200. Bonus payments were suspended to those receiving more than 2500.

In Portugal, in that same year, this matter received a stricter but temporary treatment. Christmas, Easter and vacation benefits were abolished in the case of pensions higher than 1100. Those receiving between 600 and 1100 saw a reduction in their subsidies.

Another contact point between the two countries was the use of a social solidarity contribution. Therefore, in 2012 the tax was applied by Greece to pensions amounting to 1400 or more. The rates varied between 3% and 14%, for pensions higher than 3500. However, it was established that a pensioner could never end up receiving less than 1400. For pensioners under 60 years old, the contribution rate ranged from 6%, applied to pensions amounting between 1700 to 2300, to 10% for higher pensions.

At the same time, Portugal imposed a 25% contribution to pensions between 5028 and 7546, and 50% to superior values21.

From the point of view of the European Union institutions, the previously mentioned measures, had different impacts, since the apparently stricter measures of the Portuguese Republic were justified and respected according to E.U. principles, not jeopardising the fundamental rights. Conversely, the Greek approach failed to respect the mentioned principles as it should, originating human rights violations, and was thus criticised by the Committee.

Taking this into account, we notice a lack of permeability from the Court regarding the application of the Committee’s jurisprudence (and the Charter’s), whereas the Committee only applies the Court’s jurisprudence occasionally22.

In short, the considerations brought to light by the institutions identified show that violations of the Human Rights, inter alia, the right to social security, have already happened, as we can see in the Greek case. Having said that, we can see that the situation, both in Greece, and in Portugal show similarities, however there was a variation in time and intensity, due to the fact that Greece has undergone a higher number of mandatory austerity measures for a longer period of time, and more intensely than Portugal, since the Greek has requested three bailouts, whereas Portugal only needed one.

When looking at the data provided by Eurostat, we can see different outcomes in both countries, becoming clear that the countries went through very similar periods and that the nature of the austerity measures applied showed great resemblance.

For instance, on what concerns the minimum wage, both countries decided to freeze the minimum income value. However, the Greek population is still waiting for the government to unfreeze their salaries.

Although the austerity measures are presented as part of an economic adjustment programme, we can observe that the same core values can produce different results as displayed when we compare the unemployment rate of both countries.

We cannot blame the austerity policies alone, since the countries’ political guidance went through several changes during the economic recession. On the one hand, these were ideological shifts, due to the constant alteration of the ruling parties; on the other hand, the guidelines dictated by the European institutions restricted the administration’s autonomy. To be able to calculate the political changes, or to blame any external factors on the countries’ situations seems impossible.

In brief, and in answer to our earlier questions, there are situations in which the use of austerity measures can produce a satisfactory outcome for the growth of the country without violating human rights, as we observed in the Portuguese case. Nonetheless, one should bear in mind that the unbalanced use of austerity can and will influence the population drastically, jeopardising their rights and leaving them no other options than to resort to the European bodies designed to protect them. In these particular situations we think that, by comparing the cost-benefit ratio, the level of growth provided by these policies does not justify undermining such an important safeguard of society’s dignity as the human rights.

At this second stage, and referring to the relation between these two bodies, we should first go back in history in order to understand the different backgrounds that gave rise to both institutions.

The Convention was created at a time23 the world was still becoming aware of the atrocities committed during the Second World War, and a legal instrument solely dedicated to guarantee the protection of the human rights had not been provided yet. Inspired by the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, the Convention was the European response to the need of ensuring that the mistakes of the past would not be repeated.

Taking this into account, we can understand the more formal design of the Convention and of the Court’s actions. Their main purpose consists in being the last bastion in the protection of human rights. On the other hand, the Charter was set up with different social concerns as its background24. The latter was established to complement the content of the Convention and to widen the scope of protection given to the human rights, in order to comprehend social and economic rights as well. Thus, the Committee constitutes a “specialised extension” of the Court for the social rights.

Court rulings are expected to follow the course of the traditional case law, on account of the enormous responsibility that lays under this institution decisions, due to its binding character, and to the fact that it deals with highly sensitive political and social issues25. Therefore, the Court needs to be cautious in maintaining a common thread in all its decisions.

As far as the Committee is concerned, despite the limitations that may arise from the lack of enforceability of its decisions, so far it has been able to contribute greatly to the protection of economic, social and cultural rights with innovative and revolutionary approaches. The Committee is capable of producing bold and creative26 jurisprudence, by taking advantage of various interpretation techniques, and seeking inspiration from the Court’s vast experience while maintaining its autonomy.

Bearing these characteristics in mind, and as many authors have mentioned before, there is a natural complementarity between the two institutions and their instruments27. As Samantha Besson writes regarding the regime of non-discrimination, despite their differences “their growing body of reference jurisprudence shows interesting signs of convergence and cross-fertilisation”28. It is desirable that this kind of mutual reinforcement should contribute to a combined growth of the institutions, where they both build a harmonious, cooperative and structured case law. The dialogue between them can raise the standards in economic, social and cultural rights, as well as of enhancing the European social model29.

In the examined cases, the Committee was quite successful in using the Court’s jurisprudence and various sources of soft law by international and national bodies (e.g. ILO), while maintaining its own independence. When using the Court’s case law, the Committee does not mimic its older brother30, producing a systematic and reliable decision. It only uses the Court’s case law as a point of argumentation to sustain its ruling, and even ends up highlighting the Court’s more suitable character to solve questions regarding the pensioners’ right to property.

On the other hand, as far as the Court’s performance is concerned, it did not fundament its decisions using any soft law, and it was more skeptical about changing or further elaborating its previous understandings (even when asked about it a second time), leaving hardly any space for legal evolution since the previous understanding.

In both of the cases produced by the Court, which were analysed for this paper, no other legal tools were used to substantiate the Court’s decision besides the Portuguese Constitutional law, the case law of the Constitutional Court, as well as the economic adjustment programme and the European Institutions assessment of the country’s economic situation. This is rather disappointing since it does not show the desirable interconnection and harmony between the rulings of the neighbouring institutions.

Due to the Committee’s specialised nature and since the European Convention on Human Rights does not directly protect the right to social cash benefits, the choice not to use the specialised and matter-specific resources available seems rather strange to us31. In this line of thought, we believe that the existence of those resources in itself is a strong enough reason to be included as a Court (deeper) legal reasoning, providing in this way a greater understanding of its point of view.

In the discussed case, we noticed the existence of a closed gate that prevents the osmosis between the Court and other European and International Institutions, not allowing that institution to use instruments that would be more suitable to answer some of the questions presented.

Further research showed us that the Court only refers to the Committee’s jurisprudence and the European Social Charter when the applicant makes a reference to them. We could only find one case, related to the application of austerity measure where that happens – the Case of Béláné NAGY v. HUNGARY (Application n. 53080/13)32 decided by the Grand Chamber of that Court.

Therefore, in order to tackle that issue, we believe that, regardless of the sufficiency of their traditional go-to legislations (ECHR), the Court should, in some cases, state its grounds in a more complete way by providing soft law (droit mou) from other competent institutions in the matter under analysis, despite the decision made. In the mentioned cases the Court could have used the Committee’s jurisprudence regarding the use of austerity measures and the protection of the right to social cash benefits. In what the institutions of the Council of Europe are concerned, we would like to point out a report presented in June 2012 to the Parliamentary Assembly, that refers a study prepared by the OECD highlighting the potential of reductions of pension levels to widen income gaps33. The Court could have reasoned its decision using the Committee of Ministers of the Council of Europe’s resolutions, mainly the ones that concern the application of the European Code of Social Security by the different countries.

Supporting its decisions in various sources of soft law like the above mentioned would offer the Court the possibility to confer a more broad and solid protection to the rights that are not directly protected under the Convention. The Court itself has mentioned the importance of invoking other sources of law in order to interpret the Convention, for example in the case Demir and Baykara v. Turkey34 the Court referred that “it has never considered the provisions of the Convention as the sole framework of reference for the interpretation of the rights and freedoms enshrined therein”.

Another solution for this problem could be the creation of a mechanism of preliminary ruling connecting both entities where, in cases sent to the Court concerning social rights, the court has the power to send that case to the Committee to do a more complete assessment of the case. Consequently, the Court creates a communication network and enables the permeability35 between them, contributing to a more complete protection of the social rights.

This may also be introduced as a mechanism to increase connectivity, since nowadays the European Committee of social rights cannot consider individual applications (unlike the European Court of Human Rights), accepting only the Collective Complaints procedure established under the Charter. This system works as a parallel protection system which complements the judicial protection provided under the European Convention on Human Rights. Therefore, this mechanism could allow the committee to analyse individual complains rather than only being able to deal with the non-governmental organisations entitled to lodge collective complaints.

When suggesting the embedding of a preliminary ruling mechanism, the unique nature of this mechanism comes to light, once it is an element which the use is restricted to the Court of justice of the European Union.

The preliminary ruling means that the Court of Justice of the European Union has jurisdiction to hear and determine questions referred for a preliminary ruling. Cases may arise before any court or tribunal of a Member State that may request the Court of Justice to give a ruling. Since the national tribunal considers that a decision from the European institution on the question is necessary to give judgement as the subject meter of the case touches upon EU Law36.

The legitimacy over such mater derives from the ECJ acting as guardian of the treaty and its integrity. Such is proven by the Court having jurisdiction over the interpretation of treaties and the validity and interpretation of acts from union institutions, bodies or agency.

When an EU law question is raised in a case pending before a court or tribunal of Member State, that court or tribunal shall bring it before the ECJ (being mandatory when that decision has no judicial remedy under national law).

On cases of preliminary ruling under Article 267 TFEU, the court of a Member State suspends its proceedings and refers that case to the Court of Justice of the European Union notifying it. Then the decision shall be notified to the parties, Member States, the Commission, and to the institution, or agency of the EU which adopted the act of validity or interpretation37.

Provided that none of the decisions analysed in this paper originated from the ECJ, it is only natural that no discussion regarding the ECHR requesting a ruling from the ECSR exists. Nonetheless, we believe that a mechanism of preliminary ruling between the two relevant institutions could help the ECSR to guarantee the unity or consistency of European Social Rights and eliminate any disparity in the decision process.

The suggestion put forward of applying a preliminary ruling mechanism to ECSR and ECHR is that it is maintained under a regime like the TFEU’s, having the ECSR taking the ECJ’s position ECJ and the ECHR fulfilling a role similar to that of the national court. Under this proposal, the ECHR when faced with a case in which the substantive matter is composed by Social Rights shall refer the case to the ECSR. Under this system, the preliminary ruling would maintain its mandatory character being the ECHR obliged to send the cases. However, there is a main distinctive trace between this hypothetical system and the framework described in the TFEU, being that the ECSR decisions should not hold binding force to the point where its decision on the case is final. The limitation on decision power steams from such force being too constrictive on the Court, narrowing its power to a point were any decision which touches upon social rights would be, despite legally made by the Court, factually made by the ECSR. As such, in the proposed solution, the European Court of Human Rights would have to mention and incorporate the Committee arguments and conclusion in their decisions generating a correspondence between the Committee understandings and the final decision.

The suggestion for using ECSR is as the protector of social rights and deciding body in this kind of cases arises from following the "bedrock" of lex specialis derogate lex generalis. It is only natural to conclude that the ECSR as an institution created with the sole focus on European Social rights is most suitable to decide in cases of such nature. The ability to decide such cases under the umbrella of an ECHR referral works like the current EU law leaving the Court to act as the decision-maker with binding power while maximizing the usefulness of the ECSR providing it with the stage to interact with binding powers without having them.

Applying the TFEU framework on the preliminary ruling to the ECHR and ECSR relationship would change their relationship from one alike the ECJ and expert opinions (at any time entrusting anyone with the task of giving it38) to a more dependency-based relationship, reminiscent of the ECJ and Advocate General although only on matters in which the ECSR is specialized. The ECHR would use what the ECSR states to decide on the merits of any case providing the ECSR with a rock-solid base to lay-down its argumentation having it impacting the hole decision process without taking power away from the ECHR.

In reply to the questions that were asked at the beginning of this paper regarding the interaction between the Court and the Committee, we can say that, in the scrutinised cases, there is no bridge of communication connecting them. Instead, there is a one-way street from the Court to the Committee. This does not necessarily imply that there is no convergence in their decisions, since there is no reason to doubt that, if their roles were reverse in these cases, they would decide in the same way. Nonetheless, we do not consider that there is enough harmony between their reasonings, since a crossover of information does not happen, partly due to the fact their differences act as obstacles preventing them from cooperating in the task of building a more protective and innovative justice system.

5. Conclusion

In the first part of this article, we concluded that the adoption of austerity can have a negative impact on human rights. However, that effect can be reduced or even non-existent if states only use them as a last resort. Even at that time, the implementation of such policies has to be done in a considerate and cautious way, in order to avoid jeopardizing the citizens.

The second question on which this article was based, consisted in finding if that damage was justified, in critical situations regarding human rights. Our answer to that question is No’ - the ultimate interest of a State has to be its citizens and their well-being, and cases like the Greek one have showed us that austerity measures will not always produce the desired economic recovery.

Thirdly, concerning the interaction between the two decision-making bodies (involved in these cases), we have come to the conclusion that the cooperation only happens in one direction, i,e. from the Court to the Committee, since the ECHR does not attach too much importance to Committee jurisprudence. Therefore, despite the fact that there is some convergence between their decisions is not enough to say that the two institutions’ rulings are harmonized. One of the reasons for that is the fact that their differences of purpose, background, nature and enforceability are obstacles to a deeper exchange of knowledge, that could possibly allow for a wider and stronger protection of human rights, or at least to an innovative and progressive one.

6. Bibliography

ANA GÓMEZ HEREDERO, Social security as a human right : the protection afforded by the european convention on human rights, Human Rights files, n. 23 Council of Europe publishing, Strasbourg, 2007, Available at https://www.echr.coe.int/LibraryDocs/DG2/HRFILES/DG2-EN-HRFILES-23(2007).pdf (Accessed last on 8th April 2019). [ Links ]

CRAIG SCOTT, The interdependence and permeability of human rights norms : towards a partial fusion of the international covenants on human rights, Downsview-Ontario (York University, Osgoode Hall Law School), 1989, pp. 769-878. [ Links ]

CRISTINA SÂMBOAN, The Role of the European Committee for Social Rights (ECSR) in the European System for the Protection of Human Rights – Interactions with ECHR Jurisprudence, Perspectives of Business Law Journal, vol. 2, n.1, 2013, pp 228-233, Available at http://www.businesslawconference.ro/revista/articole/an2nr1/33%20Samboan%20Cristina%20EN.pdf (Accessed last on 14th March 2019). [ Links ]

GONZALO CAVERO / IRENE MARTÍN CORTÉS, The True cost of austerity. Inequality in Greece, Oxfam International, Oxford, 2013, English Version.201310.13140/RG.2.1.1739.2168 Available at https://www-cdn.oxfam.org/s3fs-public/file_attachments/cs-true-cost-austerity-inequality-greece-120913-en_0.pdf https://www.researchgate.net/publication/256840394_Intermon_Oxfam_The_True_cost_of_austerity_

Inequality_in_Greece_Gonzalo_Cavero_english_Version (Accessed last on 14th March 2019). [ Links ]

ILO - INTERNATIONAL LABOUR OFFICE, Report on the High Level Mission to Greece, Athens, 2011, Available athttp://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/@ed_norm/@normes/documents/missionreport/wcms_

170433.pdf (Accessed last on 17th March 2019). [ Links ]

PAUL GRAGL, The Right to Secondary Industrial Action under the ECHR and International Human Rights Law, Journal of International and Comparative Law, vol.1, 2014, pp. 101-110, Available at https://ssrn.com/abstract=2443708 (Accessed last on 14th March 2019). [ Links ]

POLONCA KONC?AR , On the European Social Charter – One of the Two Core Human Rights Instruments in Europe, Law of Ukraine, n.5/6, 2011, pp. 136-142. [ Links ]

SAMANTHA BESSON, Evolutions in Non-Discrimination Law within the ECHR and the ESC Systems: It Takes Two to Tango in the Council of Europe, The American Journal of Comparative Law, vol.60, n.1, 2012, available at https://academic.oup.com/ajcl/article/60/1/147/2571365 (Accessed last on 8th April 2019). [ Links ]

TIAGO DIAS, The True Cost of Austerity and Inequality - Portugal Case Study, Oxfam Case Study, Oxfam international, Oxford, 2013, [ Links ] Available at https://www-cdn.oxfam.org/s3fs-public/file_attachments/cs-true-cost-austerity-inequality-portugal-120913-en_0.pdf (Accessed last on 8th April 2019).

UNITED NATIONS - OFFICE OF THE HIGH COMMISSIONER FOR HUMAN RIGHTS, Report on Austerity Measures and Economic and Social Rights, 2012, , Available at https://www.ohchr.org/documents/issues/development/rightscrisis/e-2013-82_en.pdf (Accessed last on 14th March 2019). [ Links ]

VASSILIS MONASTIRIOTIS, A Very Greek Crisis in Austerity Measures in Crisis Countries – Results and Impact on Mid-term Development, Intereconomics,vol.48, n.1, 2013, pp. 4-32, Available at https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s10272-013-0441-3 (Accessed last on 14th March 2019). [ Links ]

1 LLM Student at University of Groningen ( h.m.oliveira.evangelista@student.rug.nl - Kijk in ’t Jatstraat 26, 9712 EK, Groningen, The Netherlands) and Master Student at Catholic University of Portugal – Porto Law School (marta.prata.domingos@gmail.com - Rua Diogo Botelho 1327, 4169-005, Porto, Portugal), respectively.

2 A. G MEZ HEREDERO, Social security as a human right: the protection afforded by the european convention on human rights, Human Rights files, n. 23 Council of Europe publishing, Strasbourg, 2007, A vailable at https://www.echr.coe.int/LibraryDocs/DG2/HRFILES/DG2-EN-HRFILES-23(2007).pdf (Accessed last on 8th April 2019).

3 In the Social Security Convention n.102.

4 Decision by the European Committee of Social Rights delivered at 20 December 2012 – Case Pensioners’ Union of the Athens-Piraeus Electric Railways (I.S.A.P.) vs. Greece (Complaint n. 78/2012); Available at hudoc.echr.coe.int.

5 Decision by the European Court of Human Rights delivered at 8 October 2013 – Cases António Augusto DA CONCEIção MATEUS against Portugal and Lino Jesus SANTOS JANUáRIO against Portugal (Applications nos. 62235/12 and 57725/12); Available at hudoc.echr.coe.int.

6 Decision by the European Court of Human Rights delivered at 1 September 2015 – Case Maria Alfredina Da SILVA CARVALHO RICO against Portugal (Application n. 13341/14); Available at hudoc.echr.coe.int.

7 As observed by: POLONCA KONC?AR, On the European Social Charter – One of the Two Core Human Rights Instruments in Europe, Law of Ukraine, n.5/6, 2011, pp. 136-142.

8 Formal agreement signed between the country requesting help and the European Commission on behalf of the Eurogroup, the International Monetary Fund (IMF), and the European Central Bank (ECB). In this document, the parties establish the economic goals that the requesting party has to reach, and the aid provided.

9 According to the information in: VASSILIS MONASTIRIOTIS, A Very Greek Crisis in Austerity Measures in Crisis Countries – Results and Impact on Mid-term Development, Intereconomics,vol.48, n.1, 2013, pp. 4-32, Available at https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s10272-013-0441-3 (Accessed last on 14th March 2019).

10 The value of the minimum wage is 683,76 since the second semester of 2012.

11 Pensioners’ Union of the Athens-Piraeus Electric Railways (I.S.A.P) v Greece” (Complaint n.78/2012), paragraph 44.

12 Except for pensioners under 60 years old in the conditions referred in paragraph 21 of the Decision on the Merits in question.

13 Paragraph 17 to 19, 53 and 54.

14 Human Rights Compliance Criteria for The Imposition of Austerity Measures in: UNITED NATIONS- OFFICE OF THE HIGH COMMISSIONER FOR HUMAN RIGHTS, Report on Austerity Measures and Economic and Social Rights, 2012, Available at https://www.ohchr.org (Accessed last on 14th March 2019).

15 These are only two (n. 2 and 3) of the conditions established by the United Nations, in a total of six.

16 ILO - INTERNATIONAL LABOUR OFFICE, Report on the High Level Mission to Greece, Athens, 2011, A vailable at http://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/@ed_norm/@normes/documents/missionreport/wcms_170433.pdf (Accessed last on 17th March 2019).

17 Further clarification on this matter will be done in the following pages.

18 T. DIAS, The True Cost of Austerity and Inequality - Portugal Case Study, Oxfam Case Study, Oxfam international, Oxford, 2013 available at https://www-cdn.oxfam.org/s3fs-public/file_attachments/cs-true-cost-austerity-inequality-portugal-120913-en_0.pdf (Accessed last on 8th April 2019).

19 Data provided by Eurostat.

20 Paragraph 44 of the Decision under analysis.

21 In the following year, the CES scope of application was extended with the purpose of covering pensions from 1350 onward.

22 Furthermore, in the case we refer to, this also happens in the Decision delivered by the European Committee of Social Rights at 7 December 2012 in the Case Federation of employed pensioners of Greece (IKA-ETAM) v. Greece (Complaint n. 76/2012) and in the Case Pensioners’ Union of the Agricultural Bank of Greece (ATE) v. Greece (Complaint n. 80/2012).

23 The Convention was drafted in 1950 and entered into force in 1953.

24 The Charter became effective in 1965.

25 As noted in: P. GRAGL, The Right to Secondary Industrial Action under the ECHR and International Human Rights Law, Journal of International and Comparative Law, vol.1, 2014, pp. 101-110, Available at https://ssrn.com/abstract=2443708 (Accessed last on 14th March 2019).

26 C. SâMBOAN, The Role of the European Committee for Social Rights (ECSR) in the European System for the Protection of Human Rights – Interactions with ECHR Jurisprudence, Perspectives of Business Law Journal, vol. 2, n. 1, 2013, pp 228-233, Avaible at http://www.businesslawconference.ro/revista/articole/an2nr1/33%20Samboan%20Cristina%20EN.pdf (Accessed last on 14th March 2019).

27One of the authors defending the complementarity is: P. KONC?AR, On the European Social Charter – One of the Two Core Human Rights Instruments in Europe, Law of Ukraine, n. 5/6, 2011, pp. 136-142.

28 S. BESSON, Evolutions in Non-Discrimination Law within the ECHR and the ESC Systems: It Takes Two to Tango in the Council of Europe, The American Journal of Comparative Law, vol.60, n.1, 2012, pp. 147-180, available at https://academic.oup.com/ajcl/article/60/1/147/2571365 (Accessed last on 8th April 2019).

29 Cfr. no mesmo sentido, C. DE ALBUQUERQUE, On The Right Track, Good Practices in Realising the Rights to Water and Sanitation, E.R.S.A.R., 2010, p.23, disponível em: http://www.businesslawconference.ro/revista/articole/an2nr1/33%20Samboan%20Cristina%20EN.pdf (Accessed last on 14th March 2019).

30 Ibid.

31 We consider this even more anomalous when we look into the Court’s decision on the Airey Case, which admits that there is no “water-tight division” separating the sphere of social and economic rights from the field covered by the Convention.

32 Decision by the European Court of Human Rights delivered at 13 December 2016 in the Case Béláné NAGY v. HUNGARY (Application n. 53080/13); Available at hudoc.echr.coe.int

33 Mentioned by the Committee in the case under analysis. Parliamentary Assembly – Austerity Measures – a Danger for Democracy and Social Rights, June 2012, §38, refers to OECD – Divided We Stand: Why Inequality Keeps Rising.

34 Decision by European Court of Human Rights delivered at 12 November 2008 in the Case Demir and Baykara v. Turkey (Application n. 34503/97); paragraph 67; Available at hudoc.echr.coe.int.

35 C. SCOTT, The interdependence and permeability of human rights norms : towards a partial fusion of the international covenants on human rights, Downsview-Ontario (York University, Osgoode Hall Law School), 1989, pp. 769-878 - A similar concept of permeability was developed about the provisions of the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, and the norms in the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights.

36 According to Article 267 of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union (TFEU).

37 According to article 23 of the Protocol No 3 On the Statute of the Court of Justice of the European Union.

38 According to article 25 of Protocol No 3 On the Statute of the Court of Justice of the European Union.