Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Acessos

Acessos

Links relacionados

-

Similares em

SciELO

Similares em

SciELO

Compartilhar

e-Pública: Revista Eletrónica de Direito Público

versão On-line ISSN 2183-184X

e-Pública vol.3 no.3 Lisboa dez. 2016

DESTAQUE

The Unity of Global Administrative Law

A unidade do Direito Administrativo Global

Euan MacdonaldI

I School of Law, University of Edinbugh. Old College, South Bridge. Edinbugh EH89YL, United Kingdom.euan.macdonald@ed.ac.uk

ABSTRACT

In this article, I offer an account of the unity of the emerging Global Administrative Law. I do so by setting out an understanding – and justification – of each of the terms in the name, specifying the conditions under which GAL can plausibly be thought of as “global”, “administrative” and “legal” in nature. My central claim is that the key to unlocking these mysteries lies in the relation of GAL to the notion of legitimacy. My argument proceeds as follows. I begin by laying down the account of legitimacy that I rely on in the rest of the piece. I then outline a set of assumptions about GAL, and the implications of the account of legitimacy for those assumptions. This provides us with a statement of the conditions of possibility and success for a fully-emerged Global Administrative Law. I then sketch how framing the field in terms of its relation to legitimacy helps us to see how the use of each of the terms in the name was justified, by giving an account of the objects, nature and scope of GAL; and conclude with some reflections on what this might mean for its “unity” if and when it finally emerges.

Keywords: Global Administrative Law, legitimacy, Hohfeld, liberty, global governance, administration, public authority.

RESUMO

O meu objetivo neste artigo é explicar em que consiste a unidade do Direito Administrativo Global, que se encontra em vias de emergir. Faço-o propondo uma caracterização—e uma justificação—de cada um dos termos do nome “Direito Administrativo Global”, especificando as condições em que é plausível dizer-se do DAG que é “direito”, que é “administrativo”, e que é “global”. A minha tese central é a de que a chave destes mistérios se encontra na relação do DAG com a noção de legitimidade. A estrutura do argumento é a seguinte. Começo por esclarecer a noção de legitimidade que adoto. Apresento de seguida um conjunto de pressuposições respeitantes ao DAG, e exponho as consequências da noção de legitimidade para essas pressuposições. Isto permite-nos articular as condições de possibilidade e de sucesso de um DAG completamente formado. Passo então a caracterizar os objetos, a natureza, e o escopo do DAG, mostrando de que forma o seu enquadramento em termos da relação com a noção de legitimidade nos ajuda a compreender a justificação para o uso de cada um dos termos do nome; e concluo com algumas reflexões sobre o significado desta análise para a “unidade” do DAG, se e quando vier emergir completamente.

Palavras-chave: Direito Administrativo Global, legitimidade, Hohfeld, liberdade, governança global, administração, autoridade pública.

1. Introduction

When making collective decisions about how best to combine our existing terms in order to name a new phenomenon, there is a useful rule of thumb: we should take care to use the terms we are using because they are justified, so that we don’t end up merely justifying them because they are used. It has not always been clear that this rule was followed in the naming of Global Administrative Law. The use of each term here implies a claim about the phenomenon that under study: that it is recognisably “global”; that it relates to “administration”; and that it is in some plausible sense “legal” in nature. Some justifications have, of course, been offered: it is “global” because it is neither national nor international; it is “administrative” because neither legislative nor judicial; it is “legal” if we allow both “hard” and “soft” norms within that category; and so on.1

These, however, are somehow unsatisfying. They feel like half-definitions, offered faute de mieux in order to press on with the real business of the analysis of different regimes and norms that seem to fall into this new category. While there was sense in this approach, at least initially, these definitional issues have remained troubling: when the contours of the field are so lightly sketched as to include almost anything (or at least to render impossible a plausible explanation of what is included relative to what is excluded), then sceptics are entitled to query whether anything distinct is being picked out by the name at all. This is precisely the point raised recently by Joseph Weiler, when he warned that GAL “runs the risk of the overreaching empire”: “When all issues of transnational or international governance become GAL... [i]t loses its explanatory power and methodological rigour”.2

There is yet another, related problem. Despite all the disagreement, there is one thing on which everyone can probably agree: Global Administrative Law doesn’t exist. That this is common ground is suggested by the ubiquity of the metaphor of “emergence” even amongst proponents of GAL. To the extent that it is agreed that a new institutional reality (broadly understood) is emerging, it is accepted that that reality does not yet fully exist. But there can be no doubt that the promise of the name is not merely that we are dealing with something global, administrative and legal; it is also that we are dealing with some thing in the first place. That is, the name “Global Administrative Law” promises an account of a phenomenon that is, or can be usefully thought of as being, fundamentally unitary. The definitional issues outlined above, however, make it extremely difficult to see the sense in which this could be true. This makes pressing the following question: what would a Global Administrative Law look like that had finally, fully, emerged?

In what follows, I will defend the claim that the choice of terms was justified: that there is a plausible understanding of the phenomenon under study in which the application of the terms “global”, “administrative” and “law” is warranted, along with the unitary implications of their conjunction. My further claim is that the key to unlocking these mysteries is the notion of legitimacy. That GAL is intimately related to legitimacy is not a new insight;3 but I think that, when fully specified, that relation can have much greater structuring, explanatory and justificatory power than has hitherto been recognised. The purpose of this article is to outline the ways in which this is so.

My argument will proceed as follows. In the next section, I will lay down (and briefly motivate) the account of legitimacy that will inform the rest of the piece. While I do think a fuller justification of this account is both necessary and possible, here I rely on its intuitive plausibility, as I want to focus on its implications for GAL if it is accepted. I will then outline a set of assumptions about GAL, and the implications of the definition for those assumptions. This will provide us with an idea of the goals of GAL, and how and when it might be successful in achieving these: its conditions of possibility and success, as it were. I will then sketch how framing the field in terms of its relation to legitimacy helps us to see how the use of each of the terms in the name was justified, by giving an account of the objects, nature and scope of GAL; and conclude with some reflections on what this might mean for its “unity” if and when it finally emerges.

A couple of final caveats. Firstly, lest this article itself be taken as an extended exercise in justifying-because-used, I should note that I take myself here to be expanding on a set of insights that have been present in the GAL project, more or less explicitly, since its inception;4 and which have since been developed – admittedly in somewhat different ways, or for different reasons – by a number of important figures within the field.5Secondly, what follows is little more than a sketch, depending for what plausibility it has on a range of contestable assumptions. Providing a defence of these assumptions and working out fully each step of the argument is the task of a book, not a paper. My hope at this stage is simply that the account I outline here will strike readers as suggestive and potentially fruitful, and at least not obviously wrong.

2. Legitimacy as Liberty

It might be thought that looking to legitimacy for answers is not particularly auspicious. Why think we can resolve the mysteries of GAL by invoking a concept that is, if anything, even more mysterious? My view, however, is that there is no great mystery to our concept of legitimacy; indeed, that it is a relatively straightforward matter to provide a useful, explicative account6 that captures (at least) most of our core uses of the term. I do not mean to suggest that the account I offer here is the only way to think of legitimacy; but I do think that this is “a good thing to mean” by that term.7 As noted above, however, I will leave the argument to this effect for another time,8 and simply explain how I will use the term for the remainder of this article, hoping that my stipulation seems an intuitively plausible one.

What are our intuitions about the meaning of “legitimacy”? It is a term that can be applied merely to describe something, or to endorse it. Such endorsements, however, are less than full-throated: to qualify something as “legitimate” is to state more that it is in some sense acceptable than that it is necessarily desirable (although it may of course be both acceptable and desirable). One way of capturing this is saying that legitimacy is about acting “within our rights”, about what we are entitled to do rather than what we ought to do. But legitimacy is also clearly related to both law and justice (and thus to moral and legal “ought”-claims), without being reducible to either (that is, something can be legal but illegitimate, or just but illegitimate, or illegal but legitimate, or unjust but legitimate). A plausible definition would also account for a range of other facts about our usage of the concept, such as its capacity to be aptly predicated of a wide range of different objects (States, institutions, laws, procedures, expectations, beliefs, children – to name but a few). Even more importantly for my purposes here, it would make sense of usages that suggest legitimacy can be either binary (something either is or is not legitimate) or a matter of degree (something can be more legitimate than something else – perhaps even whilst remaining illegitimate); and of our common intuition that the same action by the same actor might be (correctly) thought to be legitimate with regard to one actor or group of actors, but illegitimate with regard to another (or, indeed, overall).

The account of legitimacy that can, I think, fulfil all of the above desiderata, and which will inform the rest of this article, takes as its basic notion that of a legitimate action, defined as follows: an action φ is legitimate if and only if the actor is at liberty, under a given normative order, to φ.

A few words about this definition. Firstly, I take it that the notion of “liberty” is the only plausible candidate for a more rigorous expression of the idea that to act “legitimately” is to act “within one’s rights”, or in a manner in which one is entitled to do. It is drawn from the Hohfeldian understanding of fundamental legal positions, and I intend the well-known relations between these positions to hold. The “liberty to φ” referred to here means the same thing as the absence of a duty not to φ. The positions “liberty” and “duty not” are contradictories (if it is not the case that an actor is at liberty to φ, then they have a duty not to φ). This also provides us with a definition of illegitimacy: an action φ is illegitimate if and only if the actor in question has a duty not to φ. (This assumes, of course, that an action is either legitimate or illegitimate – or, put otherwise, that it is not possible for an action to be neither legitimate nor illegitimate. This assumption seems to me to be correct.) There are, however, two differences from the standard Hohfeldian schema in the basic definition above: the explicit relativisation to particular normative orders, and the absence of an explicitly relational/directed quality to the normative position. I discuss each briefly below.

This is a definition of legitimate action; in order for it to form the basis of a general account of legitimacy, it must be possible to account for all of our other core applications of the concept in terms of actions.9 This, I think, is indeed possible; in fact, given what I will say below of the relation between legitimacy claims and overall “oughts”, and the centrality of “owned” oughts to normativity in general,10 it may even be desirable. Moreover, I think doing so might help us to avoid equivocations in certain claims. Thus, for example, the claim that an institution is legitimate might simply be that it is at liberty to take the actions that it takes or proposes to take; or it might instead by the claim that whoever established it was at liberty to do so. While these claims may be related, they do not mean the same thing; and any argument that sought to assert the former by providing reasons for the latter alone would be a non sequitur. Similarly plausible reductions to action can, in my view, be given for all of our core, and at least most of our marginal, predications of legitimacy.11

The first of the deviations from the standard representation of a Hohfeldian position – the relativisation to a particular normative order – is not a particularly significant alteration, as it merely makes explicit something that was already implicit in Hohfeld’s account (given that his account is of fundamental legal positions, each one must be relativised to a legal order, and a particular one at that). While it does go beyond Hohfeld in extending this to normative orders more generally, this is not an unusual extension. This addition does, however, help us to provide an account of the relationship of legitimacy and legality, and our sense that at times these are close to synonymous, at others quite distinct. Put simply, if the liberty in question is a legal liberty, then “legitimacy” and “legality” will mean the same, or nearly the same,12 thing. If, however, the relevant normative order is morality, then the act could be one that the actor is not at liberty to take, regardless of its legality. Put simply, the act may be legal(ly legitimate), but morally illegitimate. (There will be times when the puzzle of the manner in which legitimacy relates to justice can also be solved in an analogous manner – an action can be unjust, but nonetheless legally legitimate. More complex is the claim – which I take to be relatively common – that an action is unjust but nonetheless morally legitimate. I show how an understanding of legitimacy as liberty can account for this usage too in the next section.)

The second deviation from the standard representation of Hohfeldian positions is that my definition does not assume that liberties (or normative positions more generally) are necessarily “relational” positions. Hohfeld assumes that every legal position must correlate with a legal position of someone else. But many authors have argued we can have relational as well as non-relational duties and liberties, a point which my definition is meant to reflect.13 At the very least, the term “duty” is often used to mean two different things: a relational duty owed to another individual (as understood by Hohfeld) and as a synonym for an overall “ought”.14 This means that “liberty” can also have (at least) the two meanings that correspond to the negations of the two meanings of duty: a relational liberty (the absence of a relational duty) or an overall not-the-case-that-ought. These meanings, although related, are importantly distinct. My account of legitimacy implies that it also has these two distinct uses: one relational, the other overall.

How does all of this relate to global governance in general, and GAL in particular? It is a commonplace that GAL is one proposed response to the problems thrown up by globalisation; that it might help us solve the perceived “legitimacy crisis” of globall governance. We are now in a position to state precisely what this crisis might consist in, and whether and how GAL might contribute to addressing it. The first point to make is that, for the sake of simplicity, I will take no position here on whether or not there actually is a legitimacy crisis in global governance, and focus instead on the perception that this is the case, and on GAL’s ability to successfully address this perception.15 Secondly, I take it that this “crisis” refers primarily to a lack of moral and not legal legitimacy (although this is certainly not universally taken to be true, it seems to me to underpin most analyses). For this to be the case, then, it must be true that in general, the institutions of global governance are not morally at liberty to – that is, have a moral duty not to – take the actions that they take. For there to be a generally perceived legitimacy crisis, there must be a general perception that this is the case. For this perceived crisis to be in principle addressable, it is very likely necessary that there is general agreement on the reasons why this is the case. For this perceived crisis to be in practice addressable, it is very likely that there must also be general agreement on the considerations that could either deny or defeat the reasons mentioned above. For GAL to be able to at least partially contribute to the resolution of the crisis, it must either reflect or engender agreement that it provides us with a set of considerations that support the claim that the institutions in question are at liberty to take the actions that they take.

In a nutshell: in order to substantiate the claim that an institutional actor is lacking in legitimacy, we need to know that there are at least prima facie reasons why it ought not to be taking the actions that it takes. GAL, if it is to be successful, must then provide us with considerations that support the claim that it is not the case that the actor ought not to be taking these actions (or, put otherwise, that the actor is at moral liberty to take those actions).

3. Legitimacy-enhancing considerations

Illegitimacy claims – claims of the form “A’s φ-ing is illegitimate”, where “A” stands for some actor – can be opposed in two different ways: either by considerations that deny the reasons why (we ought to believe that) A’s φ-ing is illegitimate, or considerations that acknowledge those reasons, but seek to outweigh them. Illegitimacy deniers, thus understood, have no weight of their own; they are “spent”, so to speak, in cancelling the putative weight of reasons in support of the claim that A’s φ-ing is illegitimate. Deniers of this sort can be contrasted to legitimacy reasons, properly so called: these are considerations that themselves count in favour of A’s φ-ing being legitimate, even as they leave the reasons against this claim intact.

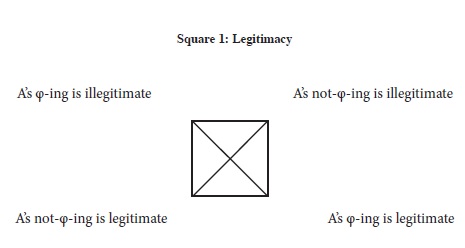

Two types of considerations can function as legitimacy reasons for any act of φ-ing: either those that count in favour of an actor having a duty to not-φ, or those that merely count in favour of the actor being at liberty to φ (or, put in terms of the “overall” level: those that count in favour of it being the case that the actor ought to φ; or those that merely count in favour of its not being the case that the actor ought to not-φ). These two types of claims are not synonymous; the former entails the letter, but the reverse is not the case. In fact, the relations between these statements can be depicted as follows:

This is to be understood as a traditional square of opposition. The top pair of statements are contraries: they cannot be simultaneously true, but could be simultaneously false. The diagonals are contradictories: one must be true, the other must be false. Most importantly, each contrary implies the position directly below it (its subaltern). And to complete the picture, the lower pair are sub-contraries: they can be simultaneously true, but not simultaneously false.

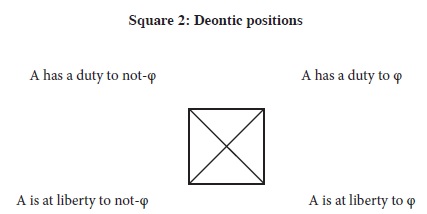

Now, given the definition of legitimate action in terms of liberty that I proposed in Section 2, the following square – depicting the logical relations between duty- and liberty-ascribing statements – is an equivalent way of depicting the contents of Square 1:16

This helps me to bring out an interesting point, if what I said above about GAL potentially providing legitimacy reasons is accepted. For it now appears that there are two types of such reasons. Given that the proposition “A’s φ-ing is legitimate” is the subaltern of “A’s not-φ-ing is illegitimate”, and that the truth of a proposition implies the truth of its subaltern, any consideration that can be offered in support of the claim that an actor A has a duty to φ is also a consideration in support of the claim that A is at liberty to φ. But not every consideration that can be offered in support of the claim that an actor A is at liberty to φ is also a consideration in support of the claim that A has a duty to φ (because the relevant relationship is one of entailment, not equivalence).

(This accounts, I think, for much of the puzzling relation between justice and legitimacy. If A’s φ-ing is just, then that counts in favour of A’s φ-ing, and is therefore one consideration that can be offered in support of the claim that A has a duty to φ. But any such consideration is also a consideration that supports the claim that A is not under a duty not to φ. And if A is not under a duty not to φ, then, equivalently, A is at liberty to φ. And if A is at liberty to φ, then A’s φ-ing is legitimate. Thus all justice reasons are also legitimacy reasons; but the inverse does not hold – precisely because there may be some moral reasons why A is at liberty to φ which are not at the same time reasons why A has a duty to φ. The consent of those who would be negatively affected by A’s φ-ing, for example, can often function in this manner.)

Thus, GAL could legitimise (or contribute to the legitimimation of) some global governance action φ by some actor A by providing one of three types of legitimacy-enhancing considerations: firstly, those that simply deny that putative reasons why φ-ing would be illegitimate are true (for example, by showing that any putative reasons why A might be thought to have a duty to not-φ are false or inapplicable); secondly, reasons in support of the proposition it is not the case that A has a duty to not-φ (or, put otherwise, considerations that count in favour of the claim that A is at liberty to φ); and thirdly, considerations that count in favour of the claim that A has a duty (or ought overall) to φ. Call the second kind of consideration direct legitimacy reasons, and the third indirect ones.

For an example of the first of these, consider the role that fair trial guarantees play in legitimating imprisonment. If one reason that could plausibly be given in support of the claim that we have a duty not to imprison people is the high risk that we would punish innocents, then procedural fair trial guarantees serve simply to cancel that reason. Note that procedural guarantees do not, in and of themselves, give us any reason to imprison someone; they simply remove one reason that would otherwise count against imprisoning someone.

A direct legitimacy reason is something that counts in favour of the actor being at liberty to φ without also counting in favour of the actor’s having a duty to φ. One example might be found in the freedom to manifest religious belief: we might think that the fact that a religious belief in traditional forms of marriage is genuinely held counts in favour of the holder of that belief being at liberty to discriminate against, say, gay couples in the provision of certain services (even if overall, we think, as the law today tends to confirm,17 that the considerations counting against the permissibility of such discrimination are sufficient to outweigh, all things considered, that belief, creating an overall duty not to discriminate). Note that whatever the principle of liberty to manifest religious belief does, it does not create reasons why people ought to discriminate in such manner; only (defeasible) reasons why it is not the case that they ought not do so. This is the essence of what I am calling a direct legitimacy reason.

Examples of the indirect legitimacy reasons are not hard to conceive: if a particular institutional action φ will negatively affect the interests of some private individuals, then that is a consideration in favour of the claim that the relevant actor has a duty not to φ; however, if φ-ing is also necessary to further some important common or public good, such as the prevention climate change, then those initial reasons, although still applicable, can be outweighed on the basis that the insitution is not merely at liberty, but actually has a duty, to φ. Given that a duty to φ entails a liberty to do so (where both are understood at the overall level), then such reasons support the claim that φ-ing is legitimate indirectly, via the claim that not-φ-ing would be illegitimate.

4. Administration: The Objects of GAL

We now have an account of what it means for there to be a legitimacy crisis in global governance: that there is good reason to think that the relevant actors have a moral duty not to be taking – are not at liberty to take – the actions they are taking. We also have an account of the conditions of possibility and success of GAL: that it can provide us, and actually does provide us, with a set of legitimacy-enhancing considerations, of the kinds outlined above, that support of the claim that it is ultimately not the case that the relevant actors are not at liberty to take the actions they are taking.

We appear, however, still no closer to the justification, which I promised at the outset, of the name “Global Administrative Law”. Can understanding GAL in terms of its relation to legitimacy, so understood, achieve this?

Let’s begin with the object of GAL: the notion of “administrative action”. It has long been thought that, in the context of the State, this can be relatively straightforwardly defined as action by public authorities that is not legislative or judicial in nature.18 Even within States, however, this understanding has come under pressure, as more and more activities that were once carried out by public bodies are “contracted out” to private ones; and as obviously administrative bodies take on rule-creating or rule-applying roles that were normally thought of as paradigmatically legislative or judicial. When we move beyond the State into the extra-national arena, these issues are exacerbated. It is clear from the literature that GAL is not to be limited to formally public bodies; indeed, the proliferation of different kinds of private and hybrid bodies exercising what we loosely take to be some kind of “governance function” is often cited as one of the main drivers of the demand for GAL. And it is equally clear that many of the bodies that are making or applying rules in global governance are some of the main targets of GAL: in part precisely because they cannot sensibly be thought of as legislative or judicial in nature, despite the character of their activities.

Can the concept of legitimacy help us to make sense of this, and ground a plausibly discrete account of what constitutes “public”, or “governance”, or “administrative” activity, such that the actor and activities in question are properly thought of as falling under the scope of GAL? I think so. My proposal is essentially that we think of the set of “public” activities as a set that is characterised by a particular legitimacy problem; we should focus, not (or not only) on the nature of the activities themselves, but (also) on the particular considerations that may legitimise them.

As a first step, an approach like this enable us to distinguish “administrative” activity from “legislative” or “judicial” acts, whilst still allowing individual acts of rule-making and rule-applying to fall within the first category (what we commonly refer to as “quasi-legislative” or “quasi-judicial” acts). My goal here is not to give a full account of these for each category, but very crudely we might think today that for an activity to be genuinely legislative, it must in part be legitimated democratically (whatever that may involve); and for it to be genuinely judicial it must be legitimated by the particular set of considerations that justify the activities of courtroom processes and actors. This provides us, I think, with a more precise understanding of the sense in which it is correct to say that a “public” activity is “administrative” if it is not legislative or judicial in nature.

But this is still only half a definition. We may not feel the need to justify the “public” or “governance” nature of activities when these consist in the creation or application of legal rules; but this cannot be thought to exhaust the domain of “administrative” activity. Particularly in the context of GAL, we want to include the setting of standards that are not obviously legal; even acts of certification or, in some instances, the collection and publication of data or other forms of information. So we still need an account of what it is that ties the members of the set of “administrative activities” together, even if we accept that certain activities are obviously members.

Here is my suggestion: the set of “administrative activities” includes (a) any and all action (a1) by a formally public actor that modifies the legal positions of others or (a2) that is given force of law in such a manner as to be a material element in the creation or modification of the duties (or liabilities to duties) of third parties regardless of their consent (with the exception of extinguishing duties owed exclusively to the actor in question); and (b) that cannot be legitimated by the considerations applicable to legislative or judicial action.

A few words about this admittedly somewhat cumbersome definition. The first disjunct (a1) combined with (b) merely restates the “half definition” offered immediately above. Disjunct (a2) is intended to specify the extension of the set of administrative activities to non-public actors. The scope of actions covered by (a2) is clearly much less than (a1), and this is, I think, as it should be: it seems plausible that there are some actions that do count as administration if undertaken by public actors, but do not if taken by private ones. (That is: there are some actions that are administrative merely as a function of the nature of the actor, and others that are adminsitrative as a function of the nature of the action. This definition captures this intuitively plausible point). The requirement in (a2) that the normative positions of third parties be altered without their consent, and the limitation of the relevant normative positions to duties and/or liabilities to duties,19 are meant to distinguish this set of activities from those regulated by private law (parties can, of course, create or alter their own legal positions through contract; and we can create new powers for third parties simply by violating our legal duties towards them). Further, in (a2), the activity need not itself change normative positions; it suffices that it be a material element in such change. By a “material element” I mean that the activity or any of its outcomes features as one reason (if not the reason) behind the creation or modification of the relevant legal positions. Crucially, the activity must itself be (part of) the reason for the change, and not merely a reason to belief that a change has occurred or is warranted.20 This allows us, for example, to think of the production of information – for example, in the form of indicators – as administrative activity, even if carried out by a private actor, if those indicators are then given force of law in such a manner that the normative positions of third parties are modified regardless of their consent. Lastly, the normative change must be in legal positions. I unpack this last point more fully in the next section.

5. Legality: The Nature of GAL

I have just offered a definition of administrative (or “governance”, or “public”) activity which speaks of activities that are given “force of law”. If this is correct, then the encoding of the activity in question within legal norms can be one necessary condition of that activity being properly characterised as administrative. This would mean, for example, that while a private certification scheme is not in and of itself administrative, it would become so if such certification became, for example, a component of public procurement rules within a given State or international organisation. This makes legality, in some sense, necessary for administration; but it does not speak to the nature of the rules governing administration. We could have global administration without any global administrative law.

One difficulty faced by GAL in this respect is that it is offered precisely as a solution to the legitimacy problems created by the various different forms of fragmentation characteristic of global governance; and it seeks to do so in an environment in which providing some sort of overarching systemic unity seems neither possible nor desirable. This means that it is likely to be fruitless to look for determinate or discrete “sources” of GAL, or to attempt to determine the validity of rules by reference to any single accepted criterion shared by some relevant class of public officials. No such system currently exists, and the prospects for its “emergence” seem dim.

The prospects for GAL would be similarly dim, therefore, if such a system were necessary to vindicate the “legal” claim contained in the name. Fortunately, this is not necessary. If my argument to this point is accepted, an extra-national activity only counts as administration if and to the extent that it is given force of law within some legal order in such a manner as to be a material element in the alteration of the normative positions of third parties without their consent.

Now, any such administrative activity gives rise to a legitimacy problem if and to the extent that there is good reason to think that it should have been given that force. And a successful response to that legitimacy problem would be one that either denied or defeated that reason. GAL can then be understood as the set of rules, processes and procedures that make it morally legitimate for a given legal order to give administrative activity – as defined in the previous section – force of law. Or, to put it differently – since I am taking the very ascription of legal force to certain activities as a definitional aspect of their administrative nature – GAL can be understood as the set of rules, processes, and procedures that make the legal ascription of administrative character to certain activities morally legitimate. To the extent that legal orders come to reflect these moral requirements as legal rules – that is, to the extent that they come to make the legal legitimacy of that ascription of legal force depend upon its moral legitimacy – then the relevant rules, processes and procedures will be of a legal nature.

In this way, the legal nature of GAL norms can be understood, not in terms of a single system or fundamental norm, but simply as a product of their recognition by and acceptance into different legal orders. There will be as many sources and rules of recognition of GAL as there are legal orders implicated in giving force to global governance activities. To a great degree, the question of the “emergence” of GAL will turn on the extent to which these legal orders do in fact come to accept these norms as binding requirements for the legitimate ascription of legal force to administrative action.

6. Globality: The Scope of GAL

We now have the outlines of an account of how GAL relates to “administration”, and why it is “legal”. What about the third element of the name, GAL’s “globality”?

GAL scholarship has focused on two phenomena that might at first appear entirely distinct. The first is the increasing prevalence of the appropriate standards for regulating national administrative activity being set at the extra-national level. Here, the reasoning presumably goes, we have administrative law norms that have a “global” source. The second focuses on the rules regulating the activities of administrative actors that operate beyond the national level; here, it is the subject of GAL that is presented as in some sense “global”. There are two problems with this account: the first is that the application of the term “global” remains dubious (the mere fact that something is happening beyond the State seems insufficient for it to be properly thought of as global); the second is that it is not clear how these two phenomena interrelate or combine to produce something we can justifiably call GAL.

The argument of the preceding section suggests, I think, a different analysis of GAL’s potential globality, but does so in a way that accounts for the two trends in the scholarship identified immediately above. Global governance is comprised of a vast array of different legal and normative orders – national, regional, sectoral, functional – arranged heterarchically rather than hierarchically, overlapping and often in conflict. Each legal order will have its own rules on how the activities of administrative actors belonging to another will be treated: whether ignored, rejected, or ascribed legal force. If GAL represents, as I have argued, a set of moral reasons legitimising the ascription of legal force to administrative activity; and if the emergence of GAL depends, as I have also suggested, on the extent to which legal orders reflect these aspects of moral legitimacy in their requirements for legal legitimacy; then GAL will only have fully emerged – that is, be global in scope – when there is genuinely widespread agreement on the kinds of rules, principles and processes that can provide such moral reasons (what I called above the condition of possibility of GAL), and when most if not all of the legal orders implicated in what we loosely refer to as “global governance” have accepted such rules, principles, and processes as binding requirements for the legally legitimate ascription of legal force to administrative activity.

Understood in this way, GAL might, of course, be a long time in the emerging. But this perspective does allow us to account for the two different trends within GAL scholarship outlined above as part of a single, unitary phenomenon: as two distinct trends contributing to the emergence of general agreement on the requirements for the morally legitimate ascription of legal force to administrative action; and as different ways in which this agreement is becoming translated into binding law. The more these trends come to inform each other – that is, the more demand for mechanisms to legitimate administrative action at all levels come to resemble each other – the closer we will come to a fully-emerged GAL.

7. Conclusion: The Unity of GAL

It is a mistake to think of the unity of GAL in the same way as we might think of the unity of Scots law, or of Portuguese law, or of public international law: as something systemic. Indeed, GAL’s great advantage over other proposals for addressing the legitimacy crisis of global governance is that it is able to take that governance as it finds it without simply “wishing away” the dense and fragmented array of overlapping, interlocking and conflicting normative orders that characterise that realm. If it is to be able to do this, the lawyerly temptation to establish normative hierarchy and identify a single locus of ultimate authority must be resisted. I hope that, in the preceding pages, I have been able to sketch an outline of how we might go about resisting that temptation whilst still justifiably affirming the emergence of something properly called “Global Administrative Law”.

A fully emerged GAL would thus be unified in a quite different sense: it would depend upon widespread agreement on the rules, principles and processes to be applied to administrative activity in order to render it morally legitimate (that is, in order to render it activity that the actor is morally at liberty to take); and on this agreement being translated into requirements for the legal legitimacy of granting force of law to administrative action. Note that this does not necessitate complete agreement on all aspects of morality – something even less likely (and perhaps even less desirable) than the establishment of a unitary global legal system. All that is required is consensus on the kinds of reasons that count against the ascription of legal force to administrative action, and consensus on the kinds of mechanisms that could either deny or outweigh those reasons. If no widespread agreement of this sort either exists or can be forged, the perception that there is a crisis of legitimacy in global governance simply cannot be successfully addressed; and, to the extent that an activity can only be legitimate if it is so perceived, then the project of legitimising global governance would be doomed to fail from the start. While this may turn out to be true, we have, I think, good reason to hope that it is not; reason that is in part drawn from the work already carried out in GAL scholarship relating to the increasing demand for and spread of a range of administrative law mechanisms at all levels of governance.

It would similarly be mistaken, however, to take from this that a fully emerged GAL would have no impact on the structure of global governance. Indeed, one thing that it would, I think, enable us to do is to move beyond the dichotomy between fragmentation and unity, which reduces fragmentation to the status of a mere problem and postulates unification as the only possible answer, and which still characterises much thought on this issue. It may be possible to conceive of global governance as an array of normative orders that are neither fragmented nor unified, but rather as characterised by a radically plural but relatively stable heterarchy. I use the phrase “radically plural” to refer to a pluralism between sites of public power where these are situated heterarchically as equals, and where relations between them are not bounded by an overarching order. And I use the phrase “relatively stable” to mean that these relations are characterised by neither hierarchy nor anarchy, but that conflicts between sites are managed, and prevented from becoming crises, on the basis of not merely of a “modus vivendi” but rather an “overlapping consensus” that is “stable for the right reasons” (to borrow some term from Rawls).21

A fully emerged GAL would be a key component of any such heterarchy. If its conditions of possibility and success are met, then each site of public power involved in global governance has good reason to treat the activities of all other sites as morally legitimate, and thus to view it as legally legitimate to give force of law to those activities within their own normative orders. And under such circumstances, institutional cooperation and accommodation between the different governance actors and normative orders implicated in global governance is likely to become the norm, and not the exception.

1 Justifications of this sort are briefly canvassed in Benedict Kingsbury, The Concept of Law in Global Administrative Law, 20 European Journal of International Law (2009) 23, at pp. 25-27. In that piece, of course, Kingsbury goes on to offer a much more detailed justification for the use of the term “law”. Much of what I have to say here is indebted to the arguments he advances, and my own engagement with them.

2 See Joseph Weiler, GAL at a Crossroads: Preface to the Symposium, 13 I:CON International Journal of Constitutional Law (2015) 463. [ Links ]

3 That GAL and legitimacy were closely related was evident even in the paper that initially launched and framed the project. See Benedict Kingsbury, Nico Krisch and Richard Stewart, The Emergence of Global Administrative Law, 68 Law and Contemporary Problems (2005) 15, at e.g. p. 27. My view is, however, that these authors erred in proposing an increase in accountability, rather than in legitimacy, as the key goal in terms of which GAL is to be defined. Not all accountability mechanisms are legitimacy-enhancing; and not every mechanism that is legitimacy-enhancing aims at increasing accountability (however understood). I will defend this view below.

4 For example, in the intruiging but under-theorised notion of the “global administrative space”. See Kingsbury, Krisch and Stewart, supra n. 3, at pp. 25-27.

5 I have in mind here particularly Benedict Kingsbury, International Law as Inter-Public Law, 49 Nomos (2009) 167; Kingsbury, supra n. 1; Nico Krisch, The Pluralism of Global Administrative Law, 17 European Journal of International Law (2006), 247; and Nico Krisch, Beyond Constitutionalism: the Pluralist Structure of Postnational Law, Oxford University Press, 2010.

6 By an “explicative” account I mean one that is neither purely descriptive (that is, purports to be adequate to all of our previous correct uses of a term) nor purely stipulative (that is, assigning meaning without making any claim as to capturing prior usage) in nature; rather, it is somewhere in between, aiming “to respect some central uses of a term [whilst being] stipulative on others”. See Anil Gupta, “Definitions”, The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Summer 2015 Edition), Edward N. Zalta (ed.): http://plato.stanford.edu/archives/sum2015/entries/definitions/.

7 This phrase is attributed to Alan Ross Anderson by Nuel Belnap in his discussion of explicative definitions. Belnap notes that this type of definition is characteristic of “most distinctively philosophical acts of definition”, in which the author “neither intends simply to be reporting the existing usage of the community, nor would his or her purposes be satisfied by substituting some brand new word. In some of these cases it would seem that the philosopher’s effort to explain the meaning of a word amounts to a proposal for ‘a good thing to mean by’ the word.” Nuel Belnap, On Rigorous Definitions, 72 Philosophical Studies (1993) 115, at pp. 116-117. See also Gupta, supra n. 6.

8 I seek to give a fuller defence of this definition in Euan MacDonald, Legitimacy as Liberty (unpublished manuscript on file with the author).

9 I will use the term “action” for simplicity’s sake in the context of this article; given my focus on governance, it is sufficient for my purposes here. It is also the most common way of thinking about the content of Hohfeldian positions (see e.g. Matthew H. Kramer, Rights Without Trimmings, in A Debate Over Rights: Philosophical Enquiries, Oxford University Press, 2001, pp. 13-14; and Luís Duarte d’Almeida, Fundamental Legal Concepts: The Hohfeldian Framework, 11 Philosophy Compass (2016, forthcoming) 1-16, at p. 3). As a more general matter, however, I see no conceptual reason to limit deontic positions to actions in this manner: any verb phrase would seem to be apt to form the content of such a position, not merely those denoting action types (there seems to be no conceptual reason why we could not, for example, be at liberty to believe, or to intend, or to desire). There are, of course, good reasons why the law should not be concerned with such mental states. Broome makes a related observation in rejecting the claim that “an owned ought can always be treated as a relation between an owner and an act-type”. See John Broome, Rationality Through Reasoning , Blackwell, 2013, at pp. 17-18.

10 I am here drawing on the work of John Broome, who distinguishes between “unowned oughts” (such as “life ought not to be so unfair”) and “owned oughts” (“Alison ought to get a sun hat”, or even “Alex ought to get a severe punishment” – the difference between the two being that Alison is the owner of the ought in the first case, whereas in Alex’s case the owner of the ought is left unspecified. Broome parses these – with apologies for violence to English grammar – as “Alison ought that Alison will get a sun hat” and “Some\one ought that Alex will get a severe punishment” respectively). See Broome, supra n. 9, at pp. 12-18. He argues persuasively that “owned” oughts are central to normative thought; indeed, he remains open on whether unowned normative oughts exist. An interesting parallel question is whether, if they exist, “unowned” normative oughts can be translated into legitimacy-talk in the same manner that, I suggest, “owned” ones can. My suspicion is they cannot, and if so this would remove one possible objection to defining legitimacy in terms of liberty. But again, this argument will have to wait.

11 See MacDonald, supra n. 7.

12 An action could be “legal” in the sense of being legally valid without being one that the actor was legally at liberty to take.

13 See Duarte D’Almeida, supra n. 9, at pp. 8-9.

14 For example, in a famous article on political obligation, Smith seems to treat the terms “pro tanto obligation”, “pro tanto duty” and “pro tanto reason” interchangeably; and an undefeated consideration of this type (that is, a consideration that is not outweighed by any countervailing reason) as an overall “obligation”, “duty” or “ought”. See M.B.E. Smith, Is There a Prima Facie Obligation to Obey the Law, 82 Yale Law Journal (1973) 50. Whether there is any space for a non-relational duty that is not either merely a pro tanto reason or an overall ought is an open question for another day.[1] See MacDonald, supra n. 7.

15 The interesting question of the relation between reasons why a particular action is legitimate, reasons to believe that it is legitimate, and an actual belief that it is legitimate is beyond the scope of the present paper.

16 I am aware that representing these normative positions in this way commits me to endorsing some controversial positions concerning the logic of deontic terms (viz., that duties imply liberties). This seems to me to hold in relation to the overall level only; that is, to those uses of duty/liberty that are synonymous with the presence (or absence) of an “overall ought”. What I have to say about the logical relations between different legitimacy-statements, and different duty/liberty statements, understood at the overall, and not at the relational, level. At the latter, conflicting duties seem a possibility. On this see e.g. Kramer, supra n. 9, at 18-20. But nothing in my argument turns on this.

17 Some balancing of conflicting reasons of precisely this sort seems to have been at play in the decision of the UK Supreme Court in Bull v Hall [2013] UKSC 73, which centered on a decision by Christian hotel keepers to refuse a double room to a same-sex couple.

18 Some balancing of conflicting reasons of precisely this sort seems to have been at play in the decision of the UK Supreme Court in em Bull v Hall /em [2013] UKSC 73, which centered on a decision by Christian hotel keepers to refuse a double room to a same-sex couple..

19 A characteristic of the content of normative positions in the Hohfeldian “family” of powers (powers/liabilities/immunities/diasbilities) is that they always refer to the action of changing some normative position. While these can themselves be positions in the family of powers (e.g. you can have a power to remove someone’s immunity), because the family of powers always refers to the change of some normative position, this must always ultimately cash out in a position in the family of rights. So when I refer to “liabilities” here, I have in mind those liabilities that ultimately refer to the duties of the party in quesiton being altered.

20 Put otherwise, the activity in question must itself be part of what makes it true that a duty or liability has been created or modified, and not merely part of what makes it true that we ought to believe that a duty has been created or modified. This seems to track closely the distinction between “practical” and “theoretical” authority, with the former providing a “reason for action” and the latter merely a “reason for belief”. On this distinction, see e.g. Grant Lamond, Persuasive Authority in the Law, 17 Harvard Review of Philosophy (2010) 16. This means that the definition of administrative action does not encompass things such as, for example, judicial adoption of a standard for discharge of a duty proposed by an academic: in such cases, the mere fact that the academic has proposed it is not itself a reason for the change, but merely a reason for believing the change is a warranted or desirable one.

21 See e.g. John Rawls, The Idea of an Overlapping Consensus, 7 Oxford Journal of Legal Studies (1987) 1. [ Links ] In this way, I arrive a a similar set of conclusions – albeit by a somewhat different route – to those advanced by scholars such as Benedict Kingsbury and Nico Krisch. See supra, n. 5.