Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Indicators

-

Cited by SciELO

Cited by SciELO -

Access statistics

Access statistics

Related links

-

Similars in

SciELO

Similars in

SciELO

Share

Tourism & Management Studies

Print version ISSN 2182-8458On-line version ISSN 2182-8466

TMStudies vol.16 no.1 Faro Mar. 2020

https://doi.org/10.18089/tms.2020.160103

TOURISM: SCIENTIFIC PAPERS

Key success factors on loyalty of festival visitors: the mediating effect of festival experience and festival image

Principais fatores de sucesso na lealdade dos visitantes de festivais: o efeito mediador da experiência e da imagem do festival

Ali Dalgıç*, Kemal Birdir**

* Isparta University of Applied Sciences Tourism Faculty, Eğirdir/Isparta, Turkey, alidalgic@isparta.edu.tr

** Mersin University, Tourism Faculty, Çiftlikköy Campus, Yenişehir/Mersin, Turkey, kemalbirdir@mersin.edu.tr

ABSTRACT

This study, based on systems theory, information processing theory, image theory, stimulus-organism-response theory, and reasoned action theory, was conducted with festival visitors to investigate the effects of key success factors on festival experience, festival image, and festival loyalty. In addition, the effect of key success factors on festival loyalty through the mediator role of festival experience and festival image was investigated. This research developed a model by bringing together festival key success factors, festival experience (emotional and cognitive experience), festival image (emotional and cognitive experience), and festival loyalty. Study data were gathered from participants joining the Orange Blossom Festival in Turkey. Path analysis and structural equation modelling analysis showed that key festival success factors, festival experience, and festival image all significantly increase festival loyalty. Festival experience and festival image both play a mediating role on the effect of key festival success factors on festival loyalty.

Keywords: Festival key success factors, festival image, perception of festival experience, festival loyalty, events.

RESUMO

Este estudo, baseado na teoria dos sistemas, teoria do processamento da informação, teoria da imagem, teoria do estímulo-organismo-resposta e teoria da ação racional, foi realizado com os visitantes de um festival para investigar os efeitos dos principais fatores de sucesso na experiência, imagem e lealdade do festival. Além disso, foi investigado o efeito dos principais fatores de sucesso na lealdade do festival, através do papel mediador da experiência e da imagem do festival. Esta pesquisa desenvolveu um modelo reunindo os principais fatores de sucesso, a experiência (experiência emocional e cognitiva), a imagem (experiência emocional e cognitiva) e a lealdade do festival. Os dados do estudo foram coletados dos participantes do Orange Blossom Festival na Turquia. A path analysis e a análise de modelagem de equações estruturais mostraram que os principais fatores de sucesso, a experiência e a imagem do festival aumentam significativamente a lealdade do festival. A experiência e a imagem do festival desempenham um papel mediador no efeito dos principais fatores de sucesso na lealdade do festival.

Palavras-chave: Festival key success factors, festival image, perception of festival experience, festival loyalty, events.

1. Introduction

As Buhalis (2000) notes, events are important attraction elements for tourist destinations that can have economic, commercial, physical, environmental, socio-cultural, psychological, and political impacts on the region and local people (Fredline, Jago & Deery, 2003; Bowdin, Allen, O’Toole, Harris & McDonnell, 2006). Festivals are activities or forms of entertainment organized at certain periods or on certain dates (Janiskee, 1980). Because it is important to ensure that festival participants are happy and satisfied with the events for sustainability of the organization, it is necessary to focus on the key factors that make festivals successful (Saleh & Ryan, 1993; Getz, 1997; Özdemir & Çulha, 2009; Wan & Chan, 2013). Suitable areas, appropriate facilities, accessibility, delicious food and beverage selections, risk management, agreements with different businesses, quality services, and crowd management are some of the most cited key factors (Getz, 1997).

Events, which may be organized once or infrequently, can have any theme and offer participants a unique experience outside of their daily life (Getz, 1989; Jago & Shaw, 1998). The critical point here is the emphasis on experience outside of everyday life. This experience significant impacts on the overall satisfaction of visitors (Papadimitriou, 2013; Geus, Richards & Toepoel, 2016). In addition, the image of the event influences the behavior of participants as well as their participation. Although both variables are frequently investigated in the event literature, they have never been used in a single model.

In this study, we aimed to reveal the effects of key success factors, festival experience, and festival image on visitors’ festival loyalty. Another key objective was to reveal the mediating role of festival experience and festival image on the effect of key success factors on the visitors’ festival loyalty. The next section provides a comprehensive literature review regarding the study variables (key success factors, festival experience, festival image, and festival loyalty). The hypotheses are then presented, developed based on previous findings and related theories (Systems theory, Information processing theory, Image theory, Stimulus-Organism-Response theory and Reasoned action theory). The methodology section explains the sampling and data collection processes and the survey scales used. The findings section reports the data analysis, before the conclusion and summary.

2. Literature revıew

2.1 Key success factors in festivals

For a successful event, some factors, which can be described as key success factors, must be present both before and during it. These are factors that can change the perceptions and behaviors of participants and provide them with unique experiences. Many factors can be considered as key success factors, such as suitable festival location, sufficient employees and volunteers, ease of access to the festival area, provision of necessary information, availability of festival program, food and beverage, and accommodation facilities (Özdemir & Çulha, 2009; Yoon, Lee & Lee, 2010; Anil, 2012; Manners, Kruger & Saayman, 2012; Mason & Paggiaro, 2012; Wan & Chan, 2013; Kim, 2013; Wu, Wong & Cheng, 2014).

These factors may also vary according to the festival themes and locations Yuan and Jang (2008), in their study of wine and food festival participants in Indiana, identified three factors to explain successful events: facilities (ideal space, suitable parking areas, etc.), wine (variety of wines, etc.), and organization (short waiting time, good food, reasonable prices etc.). According to Lee, Lee, Lee and Babin (2008), the factors necessary for festivals are convenience, information, facilities, employees, program content, souvenirs, and food. Morgan (2008) suggested physical organization (venue of events, sound quality, seating, food and drinks, etc.), social interaction (with employees, local people, new and old friends, family, etc.), design (image and professionalism, diversity, environment, etc.), culture (society, region, the activity itself, etc.), personal benefits (relaxation, entertainment, self-development, sense of achievement, etc.), and symbolic areas (authenticity, tradition, nostalgia).

From their study of a wrestling event in Izmir-Ephesus, Özdemir and Çulha (2009) concluded that the key success factors were the content of the festival program, employees, facilities, food and beverage, souvenirs, appropriate facilities (resting places, toilets, and parking places), and information (provided in leaflets). Yoon et al. (2010) identified information services, festival program, souvenirs, food, and facilities. Anil (2012) suggested festival area (size of festival area, variety of activities, etc.), food (traditional, variety, quality, reasonable pricing), and appropriate facilities (toilets, parking areas, resting areas). Manners et al. (2012) listed the important factors as management, souvenirs, marketing activities, space, technical specifications, accessibility, parking, accommodation facilities, and food and beverage enterprises.

For a food and wine event, Mason and Paggiaro (2012) showed that food (food and beverage quality), entertainment, and comfort (clean toilets, resting areas, etc.) were important for the event’s success. Saayman, Kruger and Erasmus (2012) explored the factors affecting visitor experiences at an art festival in South Africa. They listed security and staff, marketing and accessibility, venue event, accommodation facilities, activities, local people, parks, restaurants, shows, and sales as important success factors. Wan and Chan (2013) reported that participants at the food festival in Macau were particularly impressed by location, accessibility, food, facilities (sufficient seating, etc.), environment and ambience (sound, crowds, etc.), quality service, festival size, entertainment, and timing. For two events in Taiwan, Lee and Chang (2017) found that the two key success factors were the festival program and facilities.

Combining these previous findings, it appears that the following play critical rols across a range of festivals: program (Özdemir & Çulha, 2009), facilities (Yuan & Jang, 2008; Saayman, et al., 2012), convenience (Özdemir & Çulha, 2009; Anil, 2012), food (Anil, 2012; Manners et al., 2012; Wan & Chan, 2013), accessibility (Manners et al., 2012; Saayman et al., 2012), information about festival (Özdemir & Çulha, 2009), festival area (Anil, 2012), souvenirs (Özdemir & Çulha, 2009; Manners et al., 2012), employees (Özdemir & Çulha, 2009), and security (Mason & Paggiaro, 2012; Saayman et al., 2012).

2.2 Festival Experience

The essence of a festival experience is that it should be a non-standard event organised at an unusual time so that it can be memorable for individuals (Geus et al., 2016). Experience can be categorized under three dimensions related to what happens in an event, information, and emotions (Biaett, 2013). The behavioral dimension of the experience concerns the behavior of individuals in physical activities. The cognitive dimension relates to participants’ awareness, perception, memory, and learning. The emotional dimension refers to feelings, emotions, preferences, and values (Getz, 2007). Kim (2013) divides festival experiences into two: external and inner festival experiences. External festival experience relates to the cognitive dimension (Akyıldız & Argan, 2010a; Tung & Ritchie, 2011; Kim, 2013) whereas inner festival experience relates to the emotional dimension (Kaplanidou & Vogt, 2010; Akyıldız, Argan, Argan & Sevil, 2013; Lee, Fu & Chang, 2015). Research on the experience perceptions of event participants shows that the activity dimension can be examined as emotional and cognitive activity perceptions.

Akyildiz and Argan (2010a) divided visitor experiences into three categories: the experience of thinking (sounds and smells, emotions in the festive atmosphere, etc.), experience of movement and interest (inspiration from festival activities, sharing of festival experiences, festive atmosphere causing behavior change), and the experience of feeling (quality of sound, appropriate level of music, good performances, etc.). Drawing on their research on the Rock’n Coke festival in Turkey, Akyildiz and Argan (2010b), categorized visitor experiences as social relationships, lifestyle, emotions, and sensory perceptions whereas Mason and Paggiaro (2012) categorized festival visitor experiences in terms of product (attractive food and wine products) and activity (festival atmosphere, pleasure of spending time outside, etc.). Akyildiz, et al. (2013), suggested three categories from studying a kite festival in Turkey: emotional experiences, relaxing and escaping from daily life, and social and nostalgic experience.

Papadimitriou (2013) focused on just one dimension for a festival in Greece: meeting new people and the opportunity of entertainment. From studying a music festival in Australia, Ballantyne, Ballantyne and Packer (2014) suggested four categories: the music experience (relaxing, enjoying new music, etc.), social experience (meeting new people with similar interests, etc.), experience of the festival itself (enjoying the festive atmosphere, revitalizing the festival environment, etc.), and experience of leaving. Lee, Fu and Chang (2015) identified two dimensions from a religious festival in Taiwan: emotional experience (finding peace, hope, etc.) and experiencing authenticity (enjoying the religious and spiritual experience).

2.3 Festival Image

Image is a criterion that affects individuals’ daily decisions, a prejudice they hold, and the sum of impressions, beliefs, and perceptions about a particular event, behavior, or individual (Crompton, 1979). Regarding events, image refers to participants’ general impressions and perceptions (Cheon, 2016). Festival image can be both cognitive (event organization, destination characteristics) and emotional (emotions, social aspects) (Koo, Byon & Baker, 2014). Wu and Ai (2016) argue that festival image is the sum of beliefs, attitudes, and impressions about it. Kaplanidou (2010) lists the components of event image as emotional, physical, social, organizational, environmental, and unique. According to Sia, Lew and Sim (2015), a festival’s image is determined by having unique experiences, attractions, entertainment opportunities, fun day trips, family/friendship, friendly environment, world-wide recognition, and security.

Wu and Ai (2016) highlighted the cognitive dimension of festival image in their study of a food festival in China. They found that values such as prestige, brand, and reputation influence participants’ cognitive image of the event. Cheon (2016) found that characteristics of the region, and festival activities and events influenced the event’s image. Research on festival and event participants’ image perceptions has focused on the emotional dimension. Therefore, another dimension to measure the images of participants may be the cognitive image (Lee, Chang & Luo, 2016). Currently, many studies use only one dimension to examine the activity or festival image (Cheon, 2016; Wu & Ai, 2016).

2.4 Festival Loyalty

Loyalty is the tendency of people to choose the same product and service in the future despite the changing conditions and marketing efforts (Oliver, 1997). Loyalty is categorized into several dimensions: cognitive (knowledge-based adherence to a brand), emotional (emotional adherence to a brand), behavioral (behavioral intention to buy the brand), and loyalty to the movement (readiness to act for the brand) (Martin, 2007). Studies of loyalty dimensions measure them through word of mouth communication, intention of recommending to others, intention of re-purchasing the product, and tolerating high prices (Cronin & Taylor, 1992; Zeithaml, Berry & Parasuraman, 1996). Festival loyalty is the commitment shown by people to attend the same festival every year. This is naturally a desired situation for festival organizers as regular participation has many benefits for both the local population and the region (Li & Lin, 2016).

Key success factors are one of the most important determinants of the loyalty of festival visitors (Anil, 2012; Wu & Ai, 2016; Lee & Cheng, 2016). Because these factors are essential for the successful completion of the festival, they can determine festival loyalty (Ayob, Wahid & Omar, 2013; Wu, et al., 2014; Choo, Ahn & Petrick, 2016). Two other factors that directly influence festival loyalty are participants’ experience (Mason & Paggiaro, 2012; Papadimitriou, 2013) and image perceptions (Kaplanidou & Gibson, 2012; Koo, et al., 2014).

2.5 Hypotheses development

Key success factors and festival experience

System Theory argues that a combination of environmental factors (society, ambiguities, networks), inputs (human resources, materials, facilities), and management (planning, organization, and control) may lead to different outputs (Getz & Frisby, 1988). The event management depends on the environment and requires many materials to ensure the continuity of the event (Mallen & Adams, 2008). In addition to the external environment, input, transformation, and output processes constitute the whole body of system theory (Getz & Frisby, 1988). The input process is the provision of resources for the formation of the activity, expansion, transformation, and creation of activities while the output process is producing meaningful results for participants and stakeholders. These three systems are essential to the success of an event (Mallen & Adams, 2008). The input process involves combining key success factors for the creation of festivals while the process from the beginning to the end of the festival is dissemination and the attitude and behavior changes of the participants by the end of the festival are the output process. Research shows that key success factors can have a significant positive effect on participants’ festival experiences (Cole & Chancellor, 2009; Mason & Paggiaro, 2012; Ayob et al., 2013; Lee & Chang, 2017). Based on systems theory and the relevant literature, we proposed the following hypothesis:

H1: Festival key success factors positively affect festival experience

Key success factors and festival image

Image, which is one of the critical factors to ensure an event’s continuity is the sum of participants’ perceptions of the activity (Wu & Ai, 2016). To create a strong image, it is necessary to effectively combine the factors that make the event successful (Sia et al., 2015; Wu & Ai, 2016). Program, physical environment (facilities, parking places, etc.), interaction (employees and volunteers, participants, etc.), and benefits (output quality) all affect participants’ perceptions about the festival and help form an image of it (Wu & Ai, 2016). According to systems theory, the successful combination of environmental factors, inputs, and management of process lead to successful outputs (Getz & Frisby, 1988). Effective implementation of the process will change the attitudes and behaviors of estival participants positively. That is, successful festivals create a positive image in the minds of the participants (Wu & Ai, 2016). Based on systems theory and the related literature, we propose the following hypothesis:

H2: Festival key success factors positively affect festival image

Key success factors and festival loyalty

System theory can also be used to link key success factors and loyalty. In addition to the external environment, a combination of many resources (people, equipment, technologies, facilities, information, etc.) are required for a successful event (Getz & Frisby, 1988; Mallen & Adams, 2008), which will in turn produce many positive outcomes (Mallen & Adams, 2008). The factors that play a role in the success of an event (employees, volunteers, food, adequate information, fitness, souvenirs, programs, facilities, festival area, accessibility, security, etc.) have significant effects on participants’ perceptions and behavior (Saayman, et al., 2012; Anil, 2012; Wu & Ai, 2016; Lee & Cheng, 2016). Based on this research, we propose the following hypothesis:

H3: Festival key success factors positively affect festival loyalty

Festival experience and festival loyalty

According to the theory of information processing, individuals’ attitudes, behaviors, and beliefs are shaped by their own experiences or by observing the social environment and taking part in events (Salancik & Pfeffer, 1978). Lindsay and Norman (1977) argue that the information that individuals remember from earlier experiences plays a significant role in later decision-making. If festival participants experience something outside of their daily life their attitudes and behaviors towards the event will likely change (Biaett, 2013). In particular, those with positive emotional and cognitive experiences will develop positive ideas about the festival, which will make them more likely to participate in future. In addition, participants’ recommendations of an event to others, their preference for the event despite changing conditions, and their enthusiasm to attend it despite increasing prices all show that experience is an important variable in festival loyalty (Mason & Paggiaro, 2012; Papadimitriou, 2013). Based on this literature, we propose the following hypothesis:

H4: Festival experience positively affects festival loyalty

Festival image and festival loyalty

Image is a complementary element in the decision-making process. That is, image is an important input in fulfilling a particular purpose. It is therefore important for the continuation of an event (Beach & Mitchell, 1987). Image theory asserts image can shape behaviors (Beach & Mitchell, 1987; Beach, 1998) due to remembered information and emotions related to an activity. Participants’ memories of an event play an important role in their decision to participate again. Thus, a positive image can increase participants’ loyalty to the event (Kaplanidou & Gibson, 2012). Based on this research, we propose the following hypothesis:

H5: Festival image positively affects festival loyalty

The mediating effect of festival experience

Stimulus-Organism-Response theory has been applied to behavioral psychology to study how individuals respond to their physical environment. The theory is mainly used by environmental psychologists Mehrabian and Russell (1974). In this theory, the physical and social environment is the stimulus, invididuals’ internal evaluations are organisms, while their positive or negative behaviors are the responses (Lee, 2009). The perception and interpretation of physical and social environment will influence individuals’ feelings. More specifically, feelings of pleasure, revival, and power will determine whether the individual avoids or approaches the environment (Lee, 2009). Mason and Paggiaro (2012) theorize that festive features can affect a participant’s experience and satisfaction, which in turn influences loyalty. As discussed above, success factors when organizing events also play an important role in festival loyalty (Saayman et al., 2012; Anil, 2012; Wu & Ai, 2016; Lee & Cheng, 2016). Thus, it is possible that the relationship between these two variables may be mediated by experience, which several studies have confirmed. (Mason & Paggiaro, 2012; Ayob, et al., 2013). Based on this literature, we propose the following hypothesis:

H6: Festival experience plays a mediating role in the relationship between key success factors and visitors’ festival loyalty

The mediating effect of festival image

According to the Theory of Reasoned Action (Fishbein & Ajzen, 1975), personal behaviors are influenced by both attitudes and subjective norms. Attitudes are positive or negative reactions to an object that can be learned by individuals. Attitudes in turn are related to behavior. Thus, individuals who are positively affected by the key festival success factors will change their attitudes and turn this experience into a behavior. In other words, key success factors will create a positive image of the festival, which strengthen the loyalty of festival visitors. Hede and Jago (2005) suggest that the activities that are successful in terms of reasoned action theory will create positive perceptions and contribute to positive image, thereby encouraging participants to visit again (Getz, 2007). Kaplanidou and Gibson (2012) argue that perceived image, attitudes, and norms in events affect festival loyalty. Research shows that key success factors significantly increase festival loyalty (Saayman et al., 2012; Anil, 2012; Wu & Ai, 2016; Lee & Cheng, 2016). However, some meditating variables should be taken into consideration. In addition to experience, which is frequently used in event definitions, image may also have a mediating role (Wu & Ai, 2016). Since the image of the festival is an assessment in the minds of the participants, it can play a mediating role between key success factors and festival loyalty (Wu & Ai, 2016). Thus, based on this literature and the theory of reasoned action, we propose the following hypothesis:

H7: Festival image plays a mediating role in the relationship between key success factors and visitors’ festival loyalty

3. Methods

3.1 Sample and data collection

The participants in this study were individuals who are over 18 and who had participated in the 2017 Orange Blossom Festival in Adana, Turkey, which attracted more than 350,000 visitors. Since the universe was more than 100,000, 384 people were targeted for the sample (Sekaran & Bougie, 2013). The data were collected between 3 and 9 April 2017 using convenience sampling and face-to-face surveying to collect 923 completed questionnaire forms. Before the data analysis, multiple normal distribution tests and multiple slingshot analysis were performed to ensure normal distribution. Based on them, 32 questionnaires were excluded (20 and 12 questionnaires respectively). The analysis was thus continued with 891 questionnaires.

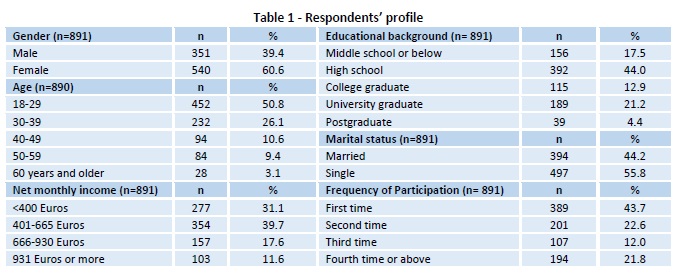

The respondents’ profile is shown in Table 1. Nearly two thirds were females while about half were aged between 18 to 29 and high school graduates. Most had net monthly incomes of 665 euros or below, and more than half had participated before.

(clique para ampliar ! click to enlarge)

3.2 Measures

The scales for four of the key success factors were derived from Anil (2012): four items from the “employees and volunteers” dimension, four items from the “food” dimension, five items from the “information” dimension, and three items from the “convenience” dimension. The souvenir dimension was adapted from Lee and Chang (2017) as three items. The program dimension was adapted from Yoon et al. (2010) as six items. The festival area and facilities dimension was adapted from Lee, et al. (2008) as six items. Accessibility was adapted from Wu and Ai (2016) with 3 items. The security dimension was adapted from Saayman et al. (2012) with 3 items.

Cognitive image was adapted from Wu & Ai (2016) with 3 items. Emotional image was adapted from Koo, et al. (2014) as 6 items. Cognitive experience was adapted from Akyıldız (2010) and Geus et al. (2016) with 5 items. Emotional experience dimension was adapted from Lee and Chang (2017) with 6 items. Finally, festival loyalty was measured on one dimension with six items adapted from Lee (2009). The following five-point Likert scale was used for all items: 1 Strongly Disagree, 2 Disagree, 3 Neutral, 4 Agree, 5 Strongly Agree. All items were translated from English to Turkish and then back translated (Brislin, 1970).

The comprehensibility of the questionnaire items was then tested on several research assistants in Mersin University Faculty of Tourism. Based on their feedback, punctuation and meaning shifts were corrected. In addition, several faculty members responded to an “Expert Opinion Form” to obtain expert opinions about the questionnaire. Based on their feedback, further corrections were made to ensure that participants would find the final questionnaire form easy to understand.

To pilot test the variables measured in the questionnaire, 258 participants at a festival held in Mersin on 9-20 January 2017 completed online or face-to-face questionnaires. This comprehensibility study of the questionnaire items indicated that no changes were needed since the participants made no objection to any scale items. Reliability and validity analyses was performed on the data obtained from 252 usuable completed questionnaires. These tests confirmed that the scales were both reliable and valid.

4. Results

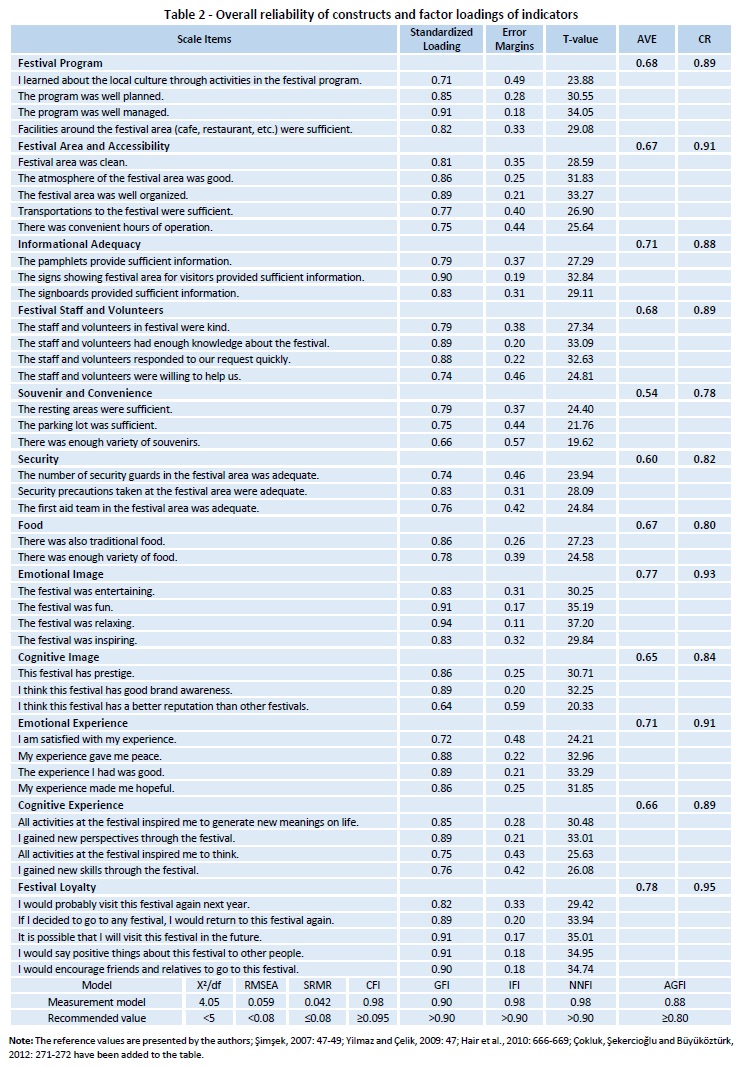

Confirmatory factor analysis was conducted on the scales used in the study, after checking for various specific assumptions. We first confirmed that the items had standardized values greater than 0.50 (Hair, Black, Babin, Anderson & Tatham, 2006) and t-values greater than ±1.96 (Schumacker & Lomax, 2004). In addition, we confirmed that the average variance extracted (AVE) value was 0.50 (Hair, Black, Babin & Anderson, 2010) and that the composite reliability (CR) value was greater than 0.70 (Hair et al., 2010). In addition, the goodness of fit model yielded the following values: normalized Chi-Square = 4.05; RMSEA = 0.059; AGFI = 0.88; GFI = 0.90; SRMR = 0.042; CFI value = 0.98; NFI = 0.97. Since these values meet the required reference values, the measured model was compatible with the theory.

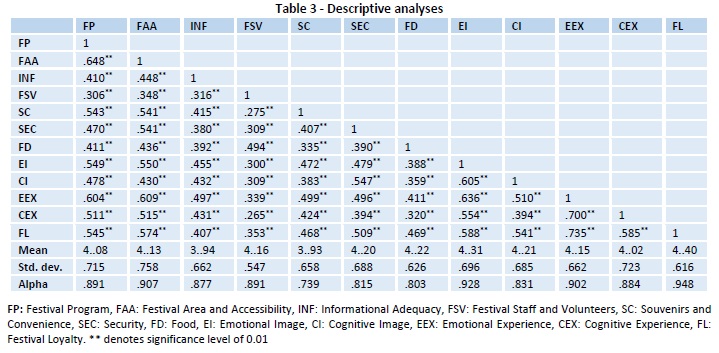

Table 3, which presents the correlations, means, and standard deviations of the variables, indicates that there are significant positive relationships between all variables.

(clique para ampliar ! click to enlarge)

(clique para ampliar ! click to enlarge)

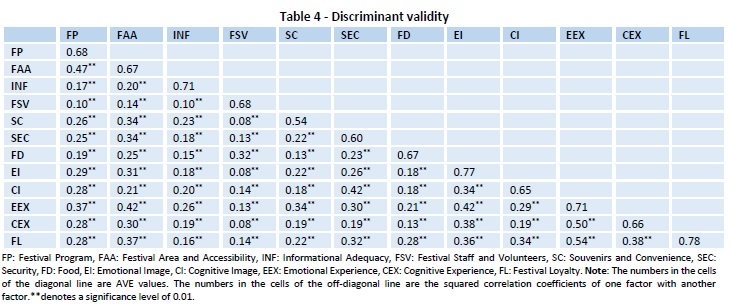

Table 4 presents the discriminant validity, which shows the degree of distinguishing (specifying the differentiation) of the factors in the model (Hair et al., 2010). For discriminant validity, the AVE values each variable should be greater than the square of the correlation coefficients between the variables (Fornell & Larcker, 1981). The analyses indicated that there was discriminant validity between the dimensions.

(clique para ampliar ! click to enlarge)

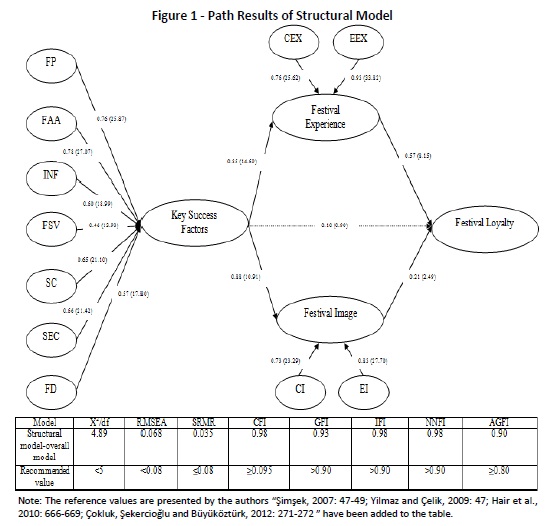

A path analysis was conducted to test the hypotheses using structural equation modeling. This showed the following significant positive relationships: between key success factors and festival experience (β= 0.83; p≤0.001); between key success factors and festival image (β= 0.85; p≤0.001); between key success factors and festival loyalty (β= 0.75; p≤0.001); between festival experience and festival loyalty (β= 0.81; p≤0.001); and between festival image and festival loyalty (β= 0.73; p≤0.001). Based on these findings, H1, H2, H3, H4, and H5 were all supported.

Figure 1 presents the path analysis results of the implemented model. When examining mediation effects, three possibilities were considered: a significant direct effect of the predictor variable on the mediator; a significant direct effect of the mediator on the outcome variable; and a direct path from the mediator to the outcome variable (Lee & Ok, 2012). In the model for this study, all the individual direct paths from the predictor variable to its corresponding outcome variable were significant at least at p < 0.05.

The model shows that key success factors had a significant positive influence on festival loyalty through the effect of festival experience (β=0.85*0.57=0.48). Since the indirect effect (β=0.48) was stronger than the direct effect, we can conclude that festival experience fully mediates the effect of key success factors on festival loyalty. Thus, H6 is fully supported. Furthermore, key success factors had a significant positive influence on festival loyalty through the influence of festival image (β=0.88*0.21=0.18). Since the indirect effect (β=0.18) was stronger than the direct effect, we can conclude that festival image fully mediates the effect of key success factors on festival loyalty. Thus, H7 is fully supported.

5. Conclusions

This study, based on systems theory, information processing theory, image theory, stimulus-organism-response theory, and reasoned action theory, was conducted on festival visitors in Turkey to investigate the effects of key festival success factors on the participants’ festival experience, festival image, and festival loyalty. It also investigated the effects of key success factors on festival loyalty through the mediator roles of festival experience and festival image. The study findings fully supported the study’s seven hypotheses: (1) key festival success factors improved festival experience; (2) key festival success factors improved festival image; (3) key festival success factors increased festival loyalty; (4) festival experience increased festival loyalty; (5) festival image increased festival loyalty; (6) festival experience fully mediated the relationship between key festival success factors and festival loyalty; (7) festival image fully mediated the relationship between key success factors and festival loyalty.

Theoretical contributions

This study developed and tested for the first time a model to integrate key festival success factors (festival program, festival area and accessibility, informational adequacy, festival staff and volunteers, souvenirs and convenience, security, and food), festival experience (emotional and cognitive experience), festival image (emotional and cognitive image), and festival loyalty.

The test of the model revealed that the leading variable of key festival success factors has a positive effect on the attitudes and behaviours of festival participants. The festival program, festival area and accessibility, informational adequacy, festival staff and volunteers, souvenirs and convenience, food, and security affect the behavior of participants. This in turn plays an important role in shaping the participants’ decisions about attending future festivals. The positive effect of the key success factors on the loyalty of festival visitors reported in this study aligns with the results of the following studies: Özdemir and Çulha (2009), Yoon et al. (2010), Anil (2012), Manners et al. (2012), Mason and Paggiaro (2012), Wan and Chan (2013), Wu et al. (2014), and Kim (2015). Furthermore, the effect of festival key success factors on festival loyalty can also be explained by systems theory. This theory posoits that positive results can be achieved by combining certain inputs (human resources, material resources, financial resources, facilities, etc.) and environmental factors. In addition to the inputs indicated in system theory, the festival program, the festival area, accessibility, security, and information factors should also be included in the inputs.

The research findings from the model indicate that festival experience and festival image are determined by key festival success factors, such as festival program, festival area and accessibility, informational adequacy, festival staff and volunteers, souvenirs and convenience, security, and food. These influence the festival participants’ emotions (happiness, satisfaction, peace of mind) and cognitive experience (gaining skills, acquiring different knowledge, gaining different perspectives). These results are similar to those of Cole and Chancellor (2009), Mason and Paggiaro (2012), Ayob et al. (2013), and Lee and Chang (2017).

The key festival success factors also influence participants’ emotional and cognitive image of the event. Consequently, key success factors also shape their attitudes. This finding is supported by Wu and Ai (2016). Applying systems theory to festivals, our model test results show that the positive outcomes mentioned in this theory should also include experience, image, and loyalty.

Our findings further suggest that the positive attitudes and perceptions of festival participants produce positive behaviours. In addition to emotional experience, such as excitement, satisfaction, and happiness, participants can also gain more knowledge about the cultural aspects of destinations and cognitive experiences through festivals, such as new skills. This may increase their intention of attending future festivals. The effect of festival experience on festival loyalty reported here confirms the findings of Mason and Paggiaro (2012), and Papadimitriou (2013). This indicates the importance of the concept of experiences outside of daily life, which is frequently reflected in the definitions of festival activities. In terms of information processing theory, the positive emotional and cognitive experiences of the festival participants lead to positive behaviors.

Our study shows that image also affects participants’ behavior of the participants in the same way as experience. This effect of festival image on festival loyalty resembles the findings of Kaplanidou and Gibson (2012), and Koo et al. (2014). A positive emotional and cognitive image of the festival encourages participants to attend future festivals. Festival experience and festival image are both important components of festival loyalty, along with factors like the participants’ attitudes, beliefs, values, emotions, and learning.

In the model tested here, festival experience and festival image fully mediated the relationship between festival loyalty and key festival success factors. These results underline the significance of integrating festival inputs (festival program, festival area, accessibility, informational adequacy, festival staff and volunteers, souvenirs and convenience, security, food) and shows that two variables (festival experience and festival image) play an important role in strengthening participants’ loyalty and creating a positive and successful festival image in their minds.

According to Stimulus-Organism-Response theory, the perception and interpretation of the physical or social environment will affect the feelings of individuals. Feelings of pleasure, revival, and power will determine whether they avoid or approach the environment (Lee, 2009). Festival participants who perceive these key factors will respond with an internal assessment of whether to participate in the next festival or not. This findingsupports research by Mason and Paggiaro (2012), and Ayob, et al. (2013). Moreover, our finding that festival image fully mediates the relationship between key success factors and festival loyalty can be explained through reasoned action theory in that the perceived factors in the festival will affect participants’ attitudes. These positive attitudes will in turn make them more likely to participate in the next event. This finding aligns those of Wu and Ai (2016).

Practical implications

This study confirmed that key success factors positively influence festival experience, festival image, and festival loyalty. It is therefore important for event practitioners to ensure that many factors are considered, such as sufficient employees and volunteers, easy access to the festival area, provision of necessary information, a good festival program, adequate and tempting food and beverages, and good accommodation facilities. This will in turn bring positive outcomes. The first goal of festival organizers is to provide participants with an extraordinary experience and a positive image from the activities. This directly determines the success of the festival. It is also important for festival organizers to present a program that appeals to the participants both emotionally and cognitively, as experience reflects the overall success of the event (Biaett, 2013). A similar situation applies to image. It is important to create a festival program that will will excite potential participants as well as cultural information that will provide a positive experience (Ayob et al., 2013; Lee & Chang, 2017) and image perception (Wu & Ai, 2016). If participants have positive experiences and a positive image perception of the festival, they will be more loyal to that festival, which is critical for the festival’s continuity. Interviews with the festival participants may help organizers to address visitors’ problems and guide organizers on the issues they need to pay attention to in future events.

This study showed that both festival experience and festival image increase festival loyalty and that both variables fully mediate the relationship between festival success factors and festival loyalty. Festivals can be successful when they offer unusual experiences because people participate not only to gain cultural knowledge but also to escape from the stress of daily life and seek excitement. The festival program, access to the festival area, food, and convenience all play significant roles in the formation of the visitor’s experiences. Participants who have positive experiences are more likely to participate in future events.

A similar situation applies to the image. A successful organization will increase the likelihood of participants participating in the next event with positive impressions and perceptions about the festival. The inclusion of key success factors in the festival event will create loyal participants. The introduction of experience or image as a mediator increases positive perceptions and potential participation. It is therefore important for festival organizers to create a festival that appeals to participants both cognitively (related to the participants’ cultural learning) and emotionally (excitement, happiness, pleasure, etc.).

Limitations and future research

As in every study, this study has limitations, of which the most important is the sampling method. Since reaching all individuals in the relevant population was nearly impossible in terms of material and human resources, sampling was preferred, so data was collected using convenience sampling. However, this method may create some problems for generalizing the study results. Future studies could obtain more generalizable results by using quota sampling. This study was limited to participants at one festival in Turkey. Future studies could investigate the factors affecting festival loyalty. Finally, it is also crucial to identify the factors necessary to ensure the continuity of the festivals.

REFERENCES

Akyıldız, M. (2010). Boş zaman pazarlanmasında deneyimsel boyutlar: 2009 Rock’n Coke katılımcılarına yönelik bir araştırma. Unpublished master’s thesis. [ Links ]

Akyıldız, M., & Argan, M. (2010a). Leisure experience dimensions: a study on participants of Ankara Festival. Pamukkale journal of sport sciences, 1(2), 25-36.

Akyıldız, M., Argan, M. T., Argan, M., & Sevil, T. (2013). Thematic events as an experiential marketing tool: Kite Festival on the experience stage. International journal of sport management, recreation and tourism, 12, 17-28. [ Links ]

Akyildiz, M. & Argan, M. (2010b). Factors of leisure experience: a study of Turkish Festival participants. Studies in physical culture and tourism, 17(4), 385-389.

Anil, N. K. (2012). Festival visitors’ satisfaction and loyalty: an example of small, local, and municipality organized festival. Turizam: znanstveno-stručni časopis, 60(3), 255-271. [ Links ]

Ayob, N., Wahid, N. A., & Omar, A. (2013). Mediating effect of visitors’ event experiences in relation to event features and post-consumption behaviors. Journal of convention & event tourism, 14(3), 177-192. [ Links ]

Ballantyne, J., Ballantyne, R., & Packer, J. (2014). Designing and managing music festival experiences to enhance attendees’ psychological and social benefits. Musicae scientiae, 18(1), 65-83. [ Links ]

Beach, L. R. (Ed.) (1998). Image theory: theoretical and empirical foundations. Abingdon, UK: Routledge.

Beach, L. R., & Mitchell, T. R. (1987). Image theory: principles, goals, and plans in decision making. Acta psychologica, 66(3), 201-220. [ Links ]

Biaett, V. (2013). Exploring the on-site behavior of attendees at community festivals a social constructivist grounded theory approach. Arizona State University.

Bowdin, G., O'Toole, W., Allen, J., Harris, R., & McDonnell, I. (2006). Events management. Abingdon, UK: Routledge. [ Links ]

Brislin, R. W. (1970). Back-translation for cross-cultural research. Journal of cross-cultural psychology, 1(3), 185-216. [ Links ]

Buhalis, D. (2000). Marketing the competitive destination of the future. Tourism management, 21(1), 97-116. [ Links ]

Cheon, Y. S. (2016). A Study on the relationship among physical environment of festivals, perceived value, participation satisfaction, and festival image. International review of management and marketing, 6(5), 281-287. [ Links ]

Choo, H., Ahn, K., & F. Petrick, J. (2016). An integrated model of festival revisit intentions: theory of planned behavior and festival quality/satisfaction. International journal of contemporary hospitality management, 28(4), 818-838.

Cole, S. T., & Chancellor, H. C. (2009). Examining the festival attributes that impact visitor experience, satisfaction and re-visit intention. Journal of vacation marketing, 15(4), 323-333. [ Links ]

Crompton, J. L. (1979). An assessment of the image of mexico as a vacation destination and the influence of geographical location upon that image. Journal of travel research, 17(4), 18-23. [ Links ]

Cronin Jr, J. J., & Taylor, S. A. (1992). Measuring service quality: a reexamination and extension. The journal of marketing, 56(3), 55-68. [ Links ]

Çokluk, Ö., Şekercioğlu, G. & Büyüköztürk, Ş. (2010). Sosyal bilimler için çok değişkenli istatistik: SPSS ve LISREL uygulamaları. Ankara: Pegem Akademi. [ Links ]

Fishbein, M., & Ajzen, I. (1975). Belief, attitude, intention, and behavior: an introduction to theory and research. Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley.

Fornell, C., & Larcker, D. F. (1981). Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. Journal of marketing research, 18(1), 39-50. [ Links ]

Fredline, L., Jago, L., & Deery, M. (2003). The development of a generic scale to measure the social impacts of events. Event management, 8(1), 23-37. [ Links ]

Getz, D. (1989). Special events: Defining the product. Tourism management, 10(2), 125-137. [ Links ]

Getz, D. (1997). Event management & event tourism. New York: Cognizant Communication Corporation. [ Links ]

Getz, D. (2007). Event studies: Theory, research, and policy for planned events. Oxford: Elsevier. [ Links ]

Getz, D., & Frisby, W. (1988). Evaluating management effectiveness in community-run festivals. Journal of travel research, 27(1), 22-27. [ Links ]

Geus, S. D., Richards, G., & Toepoel, V. (2016). Conceptualisation and operationalisation of event and festival experiences: creation of an event experience scale. Scandinavian journal of hospitality and tourism, 16(3), 274-296. [ Links ]

Hair, J. F., Black, W. C., Babin, B. J., & Anderson, R. E. (2010). Multivariate data analysis a global perspective. New Jersey: Pearson. [ Links ]

Hair, J. F., Black, W. O., Babin, B. J., Anderson, R. E., & Tatham, R. L. (2006). Multivariate data analysis a global perspective. New Jersey: Pearson. [ Links ]

Hede, T. M., & Jago, T. L. (2005). Perceptions of the host destination as a result of attendance at a special event: a post-consumption analysis. International journal of event management research, 1(1), 1-12. [ Links ]

Jago, L. K., and Shaw, R. N. (1998). Special events: a conceptual and definitional framework. Festival management and event tourism, 5(1-2), 21-32.

Janiskee, B. (1980). South Carolina's Harvest Festivals: rural delights for day tripping urbanites. Journal of cultural geography, 1(1), 96-104. [ Links ]

Kaplanidou, K. (2010). Active sport tourists: sport event image considerations. Tourism analysis, 15(3), 381-386. [ Links ]

Kaplanidou, K., & Gibson, H. J. (2012). Event image and traveling parents’ intentions to attend youth sport events: a test of the reasoned action model. European sport management quarterly, 12(1), 3-18. [ Links ]

Kaplanidou, K., & Vogt, C. (2010). The meaning and measurement of a sport event experience among active sport tourists. Journal of sport management, 24(5), 544-566. [ Links ]

Kim, S. E. (2013). Experience and perceived value for participants of cultural and art festivals organized for persons with a disability: a Korean perspective (Doctoral dissertation, Purdue University). [ Links ]

Koo, S. K. S., Byon, K. K., & Baker III, T. A. (2014). Integrating event image, satisfaction, and behavioral intention: small-scale marathon event. Sport marketing quarterly, 23(3), 127. [ Links ]

Lee, J. Y. (2009). Investigating the effect of festival visitors’ emotional experiences on satisfaction, psychological commitment, and loyalty (Doctoral dissertation, Texas A&M University). [ Links ]

Lee, J.H. & Ok, C. (2012). Reducing burnout and enhancing job satisfaction: critical role of hotel employees’ emotional intelligence and emotional labor. International Journal of hospitality management, 31, 1101-1112. [ Links ]

Lee, T. H., & Chang, P. S. (2017). Examining the relationships among festivalscape, experiences, and identity: evidence from two Taiwanese Aboriginal Festivals. Leisure studies, 36(4), 453-467. [ Links ]

Lee, T. H., Chang, P. S., & Luo, Y. W. (2016). Elucidating the relationships among destination images, recreation experience, and authenticity of the Shengxing heritage recreation area in Taiwan. Journal of heritage tourism, 11(4), 349-363. [ Links ]

Lee, T. H., Fu, C. J., & Chang, P. S. (2015). The support of attendees for tourism development: Evidence from religious festivals, Taiwan. Tourism geographies, 17(2), 223-243. [ Links ]

Lee, Y. K., Lee, C. K., Lee, S. K., & Babin, B. J. (2008). Festivalscapes and patrons' emotions, satisfaction, and loyalty. Journal of business research, 61(1), 56-64. [ Links ]

Li, C. J., & Lin, S. Y. (2016). The service satisfaction of jazz festivals in structural equation modeling under conditions of value and loyalty. Journal of convention & event tourism, 17(4), 266-293. [ Links ]

Lindsay, P., & Norman, D. (1977). Human information processing: An introduction to psychology. New York and London: Academic Press. [ Links ]

Mallen, C., & Adams, L. J. (2008). Sport, recreation and tourism event management: theoretical and practical dimensions. Abingdon, UK: Routledge. [ Links ]

Manners, B., Kruger, M., & Saayman, M. (2012). Managing the beautiful noise: evidence from the Neil Diamond show!. Journal of convention & event tourism, 13(2), 100-120. [ Links ]

Martin, D. S. (2007). Cognitive scaling, emotions, team identity and future behavioural intentions: an examination of sporting event venues. (Doctoral dissertation, Auburn University). [ Links ]

Mason, M. C., & Paggiaro, A. (2012). Investigating the role of festivalscape in culinary tourism: the case of food and wine events. Tourism management, 33(6), 1329-1336. [ Links ]

Mehrabian, A., & Russell, J. A. (1974). An approach to environmental psychology. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press.

Morgan, M. (2008). What makes a good festival? Understanding the event experience. Event management, 12(2), 81-93. [ Links ]

Oliver, R. (1997). Satisfaction: a behavioral perspective of the consumer. New York: McGraw-Hill. [ Links ]

Özdemir, G., & Çulha, O. (2009). Satisfaction and loyalty of festival visitors. Anatolia, 20(2), 359-373. [ Links ]

Papadimitriou, D. (2013). Service quality components as antecedents of satisfaction and behavioral intentions: The case of a Greek Carnival Festival. Journal of convention & event tourism, 14(1), 42-64. [ Links ]

Saayman, M., Kruger, M., & Erasmus, J. (2012). Finding the key to success: a visitors' perspective at a national arts festival. Acta commercii, 12(1), 150-172. [ Links ]

Salancik, G. R., & Pfeffer, J. (1978). A social information processing approach to job attitudes and task design. Administrative science quarterly, 224-253. [ Links ]

Saleh, F., & Ryan, C. (1993). Jazz and knitwear: factors that attract tourists to festivals. Tourism management, 14(4), 289-297. [ Links ]

Schumacker, R. E., & Lomax, R. G. (2004). A beginner's guide to structural equation modeling. Psychology Press. [ Links ]

Sekaran, U., & Bougie, R. (2013). Research methods for business: a skill-building approach (Six Edition). New York: John Wiley & Sons Inc. [ Links ]

Sia, J. K., Lew, T. Y., & Sim, A. K. (2015). Miri City as a festival destination image in the context of Miri Country Music Festival. Procedia-Social and behavioral sciences, 172, 68-73. [ Links ]

Şimşek, Ö. F. (2007). Yapısal eşitlik modellemesine giriş: Temel ilkeler ve LISREL uygulamaları. Ankara: Ekinoks Yayınları [ Links ].

Tung, V. W. S., & Ritchie, J. B. (2011). Exploring the essence of memorable tourism experiences. Annals of tourism research, 38(4), 1367-1386. [ Links ]

Wan, Y. K. P., & Chan, S. H. J. (2013). Factors that affect the levels of tourists' satisfaction and loyalty towards food festivals: a case study of Macau. International journal of tourism research, 15(3), 226-240. [ Links ]

Wu, H. C., & Ai, C. H. (2016). A Study of festival switching intentions, festival satisfaction, festival image, festival affective impacts, and festival quality. Tourism and hospitality research, 16(4), 359-384. [ Links ]

Wu, H. C., Wong, J. W. C., & Cheng, C. C. (2014). An empirical study of behavioral intentions in the food festival: the case of Macau. Asia pacific journal of tourism research, 19(11), 1278-1305. [ Links ]

Yılmaz, V. ve Çelik, H. E. (2009). Lisrel ile yapısal eşitlik modellemesi: Temel kavramlar, uygulamalar, programlama. Ankara: Pegem Akademi Yayıncılık.

Yoon, Y. S., Lee, J. S., & Lee, C. K. (2010). Measuring festival quality and value affecting visitors’ satisfaction and loyalty using a structural approach. International journal of hospitality management, 29(2), 335-342. [ Links ]

Yuan, J., & Jang, S. (2008). The effects of quality and satisfaction on awareness and behavioral intentions: exploring the role of a wine festival. Journal of travel research, 46(3), 279-288. [ Links ]

Zeithaml, V. A., Berry, L. L., & Parasuraman, A. (1996). The behavioral consequences of service quality. The journal of marketing, 60(2), 31-46. [ Links ]

Acknowledgement

This study was presented and accepted as a Doctoral dissertation in Mersin University Institute of Social Sciences, Department of Tourism Management.

Received: 05 November 2019. Revisions required: 15 December 2019. Accepted: 10 January 2020.