Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Acessos

Acessos

Links relacionados

-

Similares em

SciELO

Similares em

SciELO

Compartilhar

Tourism & Management Studies

versão impressa ISSN 2182-8458versão On-line ISSN 2182-8466

TMStudies vol.14 no.4 Faro dez. 2018

https://doi.org/10.18089/tms.2018.14405

TOURISM: SCIENTIFIC PAPERS

Cooperation in tourism and regional development

Cooperação em turismo e desenvolvimento regional

Teresa Costa1, Maria João Lima2

1Instituto Politécnico de Setúbal, Escola Superior de Ciências Empresarias, Campus do IPS, Estefanilha, 2914 - 503 Setúbal, Portugal, teresa.costa@esce.ips.pt

2Instituto Politécnico de Setúbal, Escola Superior de Ciências Empresarias, Campus do IPS, Estefanilha, 2914 - 503 Setúbal, Portugal, maria.lima@esce.ips.pt

ABSTRACT

The contribution of tourism to the economy in general and, i n particular, to the local economies, seems to be already unquestionable. This evidence is presented in several studies in the literature and reinforced by some official organisations. However, given both the increasing competitiveness and competition between destinations and the increasing complexity of the management of tourism destinations, the formation and development of cooperative relations between stakeholders has been pointed out as a requirement for its success and sustainability.

This study aims to understand business cooperation from the perspective of the complementarity of different territorial singularities, aimed at the tourist development of the sub-region Peninsula of Setúbal. The qualitative research was supported by a case study methodology. Documentary sources were used as collection instruments, which allowed the characterisation of the Setúbal Peninsula as well as interviews applied within a focus group, supported by a semi-structured script.

The results of the study indicate that stakeholders understand the importance of cooperation to obtain synergies that ensure the development of tourism and territory; they recognize and identify a set of benefits associated with cooperation and have a collective awareness of some of the difficulties associated with it, but which do not necessarily prevent their willingness to cooperate.

Keywords: Tourism, cooperation, sustainable regional development.

RESUMO

O contributo do turismo para a economia em geral e, em particular, para as economias locais, parece ser já inquestionável. Esta evidência é apresentada em vários estudos presentes na literatura e reforçada por um conjunto de organismos oficiais. Porém, atendendo quer ao facto de ser cada vez maior a competitividade e a concorrência entre destinos, quer ao aumento da complexidade da gestão dos espaços dos destinos turísticos, a formação e o desenvolvimento de relações de cooperação entre os stakeholders tem sido apontada como um requisito para o seu sucesso e sustentabilidade.

Este estudo tem como objetivo geral compreender a cooperação empresarial na perspetiva da complementaridade entre as diferentes singularidades territoriais, visando o desenvolvimento turístico da sub- região da Península Setúbal. A pesquisa, de natureza qualitativa, foi suportada na metodologia de estudo de caso. Como instrumentos de recolha de dados foram utilizados a análise de fontes documentais, que permitiu a caracterização da Península de Setúbal e entrevistas aplicadas no âmbito de focus group, apoiadas por um guião semi-estruturado.

Os resultados do estudo indiciam que os stakeholders compreendem a importância da cooperação para a obtenção de sinergias que assegurem o desenvolvimento do turismo e do território; reconhecem e identificam um conjunto de benefícios associados à cooperação e possuem, igualmente, uma consciência coletiva sobre algumas dificuldades a ela associadas, mas que não obstam, necessariamente, à sua disponibilidade para cooperar.

Palavras-chave: Turismo, cooperação, desenvolvimento regional sustentável.

1. Introduction

The importance of tourism for regional development seems to be increasingly recognised, and it should be seen as a tool that contributes to the sustainability of tourist destinations, both in the economic dimension and in the social and environmental dimensions. However, several authors point out the complexity of the management of tourist destination areas, reinforcing the pertinence of cooperation between them.

The Lisbon Region, already declared as a tourist destination, consists of two sub-regions: Greater Lisbon, centred in the city of Lisbon and undoubtedly recognised as a pole of tourist attractions, and the Peninsula of Setúbal, with equally attractive wealth and diversity, but still less widespread. This region includes a set of areas with different offers, whose attractiveness can be enhanced by the complementarity of the different territorial singularities, making the need for cooperation between the various agents that integrate it pertinent.

Thus, this study has as its primary objective to understand the business cooperation from the perspective of complementarity, aiming at the tourist development of the sub-region of the Peninsula Setúbal. The specific objectives were: 1) to regard the Setúbal Peninsula as an integrated territory in the Lisbon Region, in terms of tourist supply and demand; 2) to investigate how to enhance the attractiveness of this territory; 3) to know the integrated strategies, products and services; 4) to observe the availability of the various stakeholders involved in the sector for cooperation; 5) to appreciate the expected benefits of such a cooperation; 6) to understand the constraints of cooperation; 7) to recognise the areas of intervention available for future cooperation projects.

The study, which is organised in two parts, includes, in the first part, a literature review and a theoretical framework for tourism, sustainable development and regional development, as well as aspects related to cooperation. In the second part, an empirical study of a qualitative nature is developed to achieving specific objectives, through the collection of information from INE and the Lisbon Tourism Observatory; The Local Development Strategy Report for the Setúbal Peninsula 2014- 2020 and interviews conducted in the focus group

2. Literature review

2.1 Tourism and development

In 1987 the Brundtland Report presented a new development concept - sustainable development. This new concept emphasises aspects related to human resources and development, considering three crucial dimensions: economic, social and environmental (United Nations, 1987), showing a strong concern for the satisfaction not only of present but also future needs.

The understanding of tourism as a potential promoter of the general development of the economy, and particularly of local economies (Murphy, 1997, Yasuo & Shinichi, 2013) is increasingly consensual. Consequently, it is imperative that this activity takes on the values of sustainability reinforced in the Brundtland Report.

Thus, the concept of sustainable tourism must fit into sustainable development. This framework is visible in Agenda 21, chapter 7, on promoting sustainable development, which sets out as a priority the promotion and formulation of environmentally sound and culturally sensitive tourism programs as a strategy for the sustainable development of urban and rural areas and as a way of decentralizing urban development and reducing regional asymmetries (United Nations, 1992).

Over the years, the European Commission has provided some guidelines that reinforce the relevance of tourism to sustainable development. In 2007, the Tourism Sustainability Group, in the "Action for More Sustainable European Tourism" report, reinforces its objective of stimulating actions that allow more sustainable European tourism through a continuous process. In the same year, through the "Agenda for a Sustainable and Competitive European Tourism", the European Commission took on a long-term commitment, supported by the Tourism Sustainability Group report, contributing to the

implementation of the relaunched Lisbon Strategy, in line with the Sustainable Development Strategy. In this document, the Commission invites all stakeholders directly and indirectly involved in tourism to respect the principles set out in the Sustainability Group’s "Action for More Sustainable European Tourism" report.

2.2 Contribution of tourism to regional development

Several studies reveal an understanding of the relevance of tourism to development, in particular, to regional development. Some approaches have been undertaken, including that of Murphy (1997), which refers to the importance of sustainable tourism for increasing the well-being of the local community, which in itself is a determining factor for local development. Marujo and Carvalho (2010) also point out that tourism is a phenomenon of great importance from a political, economic, environmental and socio-cultural point of view. For these authors, the economic and socio-cultural importance of tourism has turned this activity into a fundamental axis for the economy and development of many regions, attracting the attention of regional and local governments interested in promoting growth in their territories. Other authors emphasise the relevance of exploiting the agricultural potential of the regions, preserving and recognising the richness of natural, cultural, historical and landscape resources, as relevant development and competitiveness factors (Fons, Ferro &Patino, 2011, Park, Lee, Choi & Yoon, 2012).

In the case of the Lisbon Region, tourism has gained importance in its economy. According to the Strategic Plan for Tourism in the Lisbon Region 2015-2019, tourism should develop a set of strategies, namely: 1) to deepen the relationship between the city of Lisbon and the Region - introduction of a tourism development model that fosters an integrated vision; 2) to reinforce the diversity of the tourist offer in the Lisbon Region, and 3) to value existing assets in the Lisbon Region by developing appropriate tourism products.

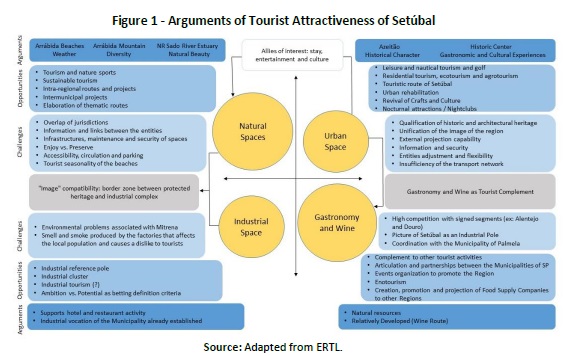

The Lisbon Regional Tourism Plan 2015-2019 (ERTL, Turismo de Lisboa) considers five centralities: Cascais, Sintra, Arrábida and Arco do Tejo, as well as the existence of a set of aggregating elements that guarantee the identity, coherence and relevance of these Territories. Setúbal is part of the central Arrábida. According to the Strategic Development Plan - Prospective Diagnosis - 2016, in the region of Setúbal there are a set of arguments and tourist attractiveness, explained in figure 1.

2.3 Cooperation, tourist destinations and regional development

The concept of a tourist destination should be understood as a space that integrates tourism as a set of cumulative attractions that, due to the impression they offer and set of tourism infrastructures, is recognised as Tourism Hotspots (Pirjevec & Kesar, 2002). The management of the spaces in these destinations is complex and issues such as "quantity of attractions that a space needs" and "maximum intensity of the simultaneous presence of tourists in the space" are important. In this sense, the concept of tourist destination must go further, that is, it must consider the "group of agents linked by mutual relationships with specific rules, where the action of each actor influences that of the others, so that common objectives must be defined and attained in a coordinated way "(Fyall, Garrod & Wang, 2012). As such, it is essential that tourist destinations present a holistic offer that incorporates the values of different entities but with experiences that are individually significant.

Also, the authors Zach and Racherla (2011, p.98) state that a tourist destination, from the perspective of the current tourist, is increasingly interpreted as "a series of interrelated activities and attractions that have to work in unison in order to achieve a satisfactory and healthy experience”. Besides, Albrecht (2013) mentions that cooperation, involving the various organisations of the sector, is worked in such a way as to combine the natural, cultural and social aspects of a destination, associating the services related to tourism, favouring the perception of a "total tourist product" and responding more effectively to tourists’ expectations.

According to Saito and Ruhanen (2017), no tourism organisation, even if it is pre-eminent in the sector, is capable of developing an effective tourist destination in its own right. The formation and development of cooperative relations among stakeholders thus appear as a prerequisite for the development of sustainable tourism (Albrecht, 2013).

On the other hand, as competitiveness and competition between destinations are increasing, cooperation between them can be an essential tool for their success and to ensure their longevity. Such co-operation is essential for increasing demand and for destinations to achieve growth and sustainable development, reconciling economic growth and social well- being while respecting environmental constraints. As Porter and Kramer (2011) point out, the creation of added value generates a greater economic worth that creates a higher value for society, responding to its needs and challenges.

The development of public and private partnerships and a decrease in competition between entities and economic agents in a tourist destination can be achieved by building common values, where all parties involved contribute to the common purpose of economic, social and environmental sustainability (Vaidyanathan & Scott, 2012). To this end, Pearce (2015) advocates long-term management of these tourist destinations, enabling optimal economic development, a high standard of living, as well as environmental, social and cultural preservation.

The management of tourist destinations should, therefore, be understood as a network of virtual organisations made up of independent organisations that have a set of resources and business objectives, with common management of segments (Maga, 2010). In this way, tourism functions and activities, which would hardly be carried out or offered individually, become feasible through cooperation which, in turn, allows for a response and superior performance.

This issue of cooperation for competitiveness and sustainability of organisations becomes particularly important in the dynamic and competitive environment in which we live, characterised by intense competition, high volatility, rapid changes and increasingly empowered consumers. Jesus and Franco (2016, p.66) even say that "very little can happen in this sector without the various organisations working together to serve and satisfy the consumer" and create value for themselves. Also, this aspect of the value created for stakeholders in the context of cooperation is a relevant issue for the success of this practice. According to Bititci, Martinez, Albores and Parung (2004, p.253), cooperation practices should be understood in the context of a win-win situation, that is, "an organisation that satisfies the expectations of its clients must create wealth for its stakeholders: creating value for both parties."

2.3.1 Benefits of cooperation

As the literature produced in different areas of knowledge attributes multiple benefits to inter-organisational cooperation, including the tourism sector, the positive values derived from it are particularly captivating for organisations.

Through cooperation, organisations reduce the costs of actions in the market, define joint strategies to achieve greater efficiency and scale (Mendonça, Varajão & Oliveira, 2015). Also, it is possible for them to share resources, skills and knowledge, risks, responsibilities and rewards (Bititci et al., 2004) and to have access to other experiences and more business opportunities (Zach & Racherla, 2011). Zee and Vanneste (2015, p.52) also mention as benefits of cooperation, "the improvement of tourism product quality, a better quality of services, a more efficient production process, growing sustainability of the tourist destination and a more competitive tourist destination. "Jesus and Franco (2016), based on a study carried out in a region in the interior of Portugal, revealing that cooperation between tourism companies contributes to higher satisfaction of tourists, as well as generating a positive impact on regional development, both in terms of economic growth and social benefits generated for the local community.

As seen, there are many advantages derived from the cooperative relationships established between organisations. However, according to Cao and Zhang (2010, p.359) these advantages "may not be immediately visible."

Also, as one would expect, some factors make it difficult to establish cooperative relations, to consolidate and maintain them. Nonetheless, the same authors point out that the potential rewards of a long-term relationship are so attractive and strategic to the organisations involved that they "should invest their efforts to make it work" (Cao & Zhang, 2011, p.175).

2.3.2 Difficulties to inter-organisational cooperation

In the case of relations between organisations, cooperation presents some complexity, and there are a set of factors, already identified in the literature that can obstruct its operationalisation. These factors are usually associated with power relations established between stakeholders (Saito & Ruhanen, 2017), often associated with their different dimensions (Jesus and Franco, 2016), which in themselves have other constraints; disagreeing visions, divergent and sometimes competing interests (Saito & Ruhanen, 2017), lack of dialogue and leadership (Jesus & Franco, 2016) but also different styles of communication (Saito & Ruhanen, 2017). It should be noted that both trust and commitment are dimensions that are referred to as being critical to the success of inter- organisational relationships (Zach & Racherla, 2011; Zee &Vanneste, 2015 and Jesus & Franco, 2016).

In the tourism sector, networks for cooperation are particularly crucial to 1) improve the designing and promotion of tourist initiatives (Cawleya, Marsatb & Gillmor 2007; Lemmetyinen & Go 2009) and 2) develop a tourism product or service that meets the expectations of consumers and increases the demand (Petrou et al., 2007; Sfandla & Bjork 2013). However, essential preconditions are crucial in the creation and development of these networks, namely mutual trust between the participants. Several authors considered that trust is essential in establishing relationships between partners (Gulati & Singh, 1998; Gabor, 2015). In inter-organisational relationships, trust involves both expecting correct behaviour from other members and having confidence in their competence (Das & Teng 2002).

The long-term success of the business relationship also depends on the ability of the participants to cooperate and coordinate (Adair and Brett, 2004). In this sense, the development of a set of negotiation strategies is essential to involve participants who are willing to cooperate (Yin, Wu & Tsai, 2012). The role of governance is also essential in encouraging coordination and supervision of the members of the network (Sherer, 2003; Zafiropoulos, Vrana & Antoniadis, 2015).

Finally, other aspects referred to by several authors are essential, such as the understanding by all participants of the purpose of the network, the equality of assets between partners (Kuittinen, et al., 2008), the amount of capital and knowledge-based investment in the network (Hoethker & Mellewigt, 2009) and the costs of coordination (Gulati & Singh, 1998).

3. Methodology

Considering the objectives described above, qualitative research was defined as more appropriate. Qualitative research allows the interaction with the subject of the research becoming, in Yin’s perspective (2011), adequate to study both the motivational basis and the dynamics that support the behaviour, interactions and decisions of individuals in a given context of daily life.

A particular methodology of this type of research is the case study because it enables the "investigation of a contemporary phenomenon in its real context, especially when the boundaries between phenomenon and context are not clearly defined" (Yin, 2003, p.13). This study aims to understand the propensity of companies and other organizations linked to the tourism sector for cooperation, considering the need to promote tourism in the Setúbal Peninsula and to increase its own competitiveness.

Also, within the methodology of a case study, this study can be presented as a single case study, given that it reveals the opinions and motivations of a group, constituted by a representative but with a delimited set of organizations belonging to a given sector, which for Yin (2003, p.40) "represents an extreme or unique case".

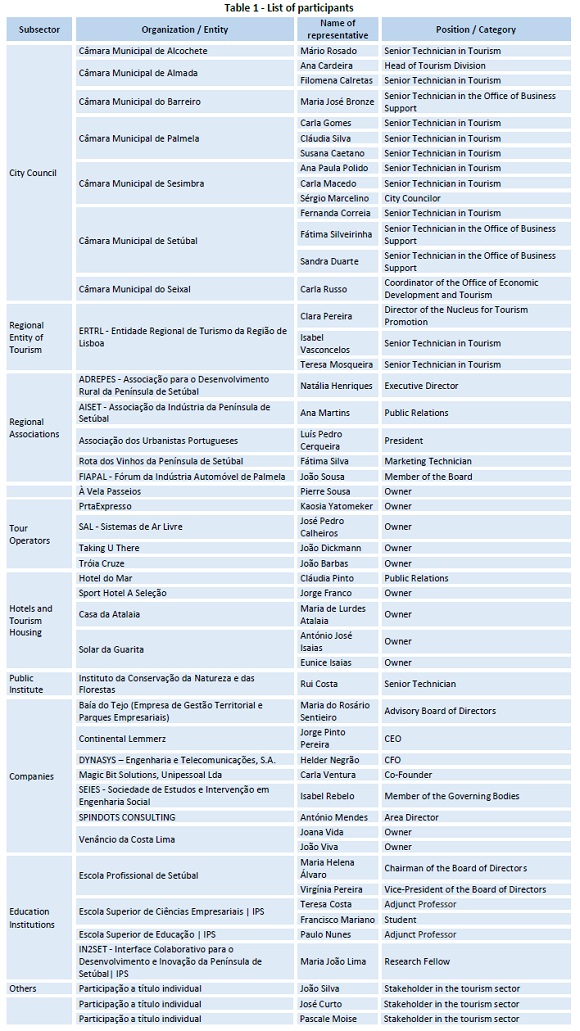

It should also be noted that, as qualitative research, given the heterogeneity of the participants, with a strong representation of the most relevant stakeholders in the region (ERTL, ADREPES, City Councils, Economic Agents with activity in several areas), it was possible to obtain rich and detailed information.

Patton (2002) and Stake (2010) point out that one of the most common qualitative research instruments is the interview, which according to Yates and Leggett (2016, p.226) can be applied to a specific group since "A focus group can be considered an in-depth group interview.”

Regarding the characterisation of the Setúbal territory, information was collected from INE; the Lisbon Tourism Observatory and the Local Development Strategy Report for the Setúbal Peninsula 2014-2020. Besides, data collection was carried out through group interviews, supported by a semi- structured questionnaire, with the objective of obtaining and describing in detail the empirical evidence in the field of research. According to Patton (2002, p. 4) in this contact the "people’s experiences, perceptions, opinions, feelings and knowledge" should be retained, and "the data constitute a literal citation with enough context to be interpretable." In this sense, the guidance of Yates and Leggett (2016, p.226) was followed, which refers that the researcher initiates discussion by asking open-ended questions so that the participants are motivated but not guided to discuss the relevant topic. The researcher listens and observes the discussions that follow, intervening as little as possible as long as the discussion remains on the topic. In such a discussion, the participants are expected to reveal their knowledge and express their opinions about the subject matter.” In this data collection, several agents from the tourism sector in the region were involved (Table 1), organised in working groups with a maximum of ten participants and coordinated by a moderator. In total 50 participants were involved. These groups were invited to reflect, discuss and respond to each of the six questions that were presented to them and which intended to infer about business cooperation in the perspective of complementarity, aiming to promote tourism and the socioeconomic development of the Setúbal Peninsula.

The focus group was guided by a semi-structured script, which included the following questions:

1. The promotion of the territory of the Setúbal Peninsula is essential for the development of Tourism in the region. How can the attractiveness of this territory be enhanced as an integral part of the Lisbon Region?

2. Integrated strategies should be developed, in which tourism is reconciled with other activities and interests through local partnerships. What strategies, products and services should be integrated (considering all the councils of the Setúbal Peninsula in an integrated way)?

3. I can leverage my business by cooperating with other partners. What are the expected benefits of this cooperation?

4. What are the main difficulties and/or constraints of cooperation? What factors do you consider critical to the success of the cooperation?

5. Cooperation in the tourism sector in Portugal is a reality and has led to positive results. What successful cooperation cases can be identified?

6. I have projects that would be successful with the right partners. What areas of intervention are available for future cooperation projects?

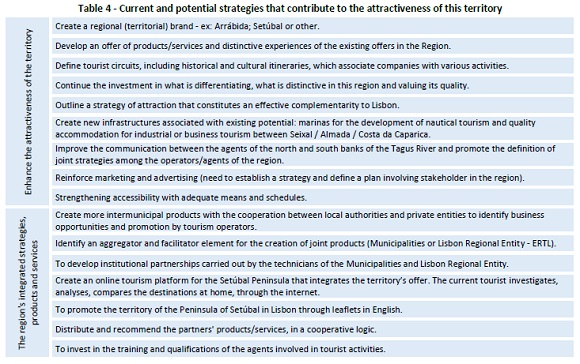

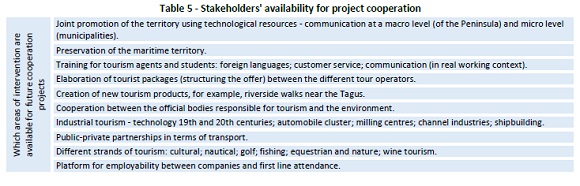

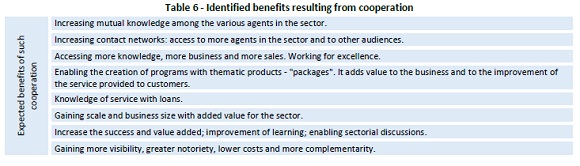

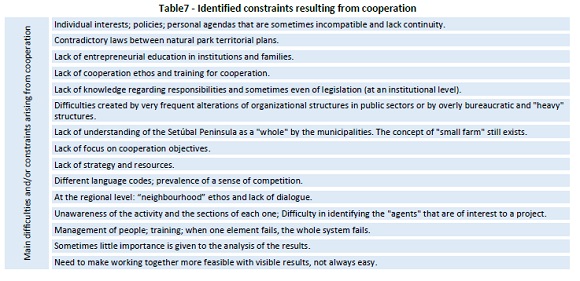

As previously referred, the participants were organised in six working groups, each one coordinated by a moderator who was responsible for asking the question assigned, moderating the debate and taking note of the information. Each question was discussed and closed after roughly twenty minutes. After that, the moderators rotated to another group, following the same procedure of asking the question, moderating the debate and annotating the information. The process was repeated until all the moderators had gone through all the groups. A final discussion was had about each question in order to all to reflect on the most relevant aspects collected during the work with the groups. The moderators were then responsible for the content analysis, which resulted in tables 4, 5,6 and 7.

The final results of the study are eminently descriptive elements showing what the researchers have been able to collect, analyse, develop and interpret.

In conclusion, it should be noted that due to the complexity and peculiarity of the case study, the final objective is to distinguish, in a meticulous and detailed way, the case itself and not its generalisation (Stake, 2010).

4. Empirical Study

The data collected allowed us to obtain answers that enable reaching specific objectives previously presented: 1) to regard the Setúbal Peninsula as an integrated territory in the Lisbon Region, in terms of tourist supply and demand; 2) to investigate how to enhance the attractiveness of this territory; 3) to know the integrated strategies, products and services; 4) to observe the availability of the various stakeholders involved in the sector for cooperation; 5) to appreciate the expected benefits of such a cooperation; 6) to understand the constraints of cooperation; 7) to recognise the areas of intervention available for future cooperation projects.

4.1 Data analysis

4.1.1 Characterization of the Setúbal Peninsula as an integrated territory in the Lisbon Region

At this point, through the collection of information from INE, the Lisbon Tourism Observatory and the Local Development Strategy Report for the Setúbal Peninsula 2014-2020, aims to meet the objective: 1) to know the Setúbal Peninsula as an integrated territory in the Lisbon Region regarding supply and demand Tourist. Thus, a characterisation of the Lisbon Region is presented, with emphasis on the Setúbal Peninsula.

The Lisbon Region corresponds, in terms of the Nomenclature of Territorial Units for Statistical Purposes, to the Lisbon Metropolitan Area which includes two sub-regions: Greater Lisbon covering the counties of Amadora, Cascais, Lisbon, Loures, Mafra, Odivelas, Oeiras, Sintra and Vila Franca de Xira and the Peninsula of Setúbal constituted by the counties of Alcochete, Almada, Barreiro, Moita, Montijo, Palmela, Seixal, Sesimbra and Setúbal.

Due to its soil and climate as well as its cultural and landscape diversity, the Lisbon Region has the necessary attributes to develop a distinctive tourist offer in European terms and in line with the specificity of each of the two sub-regions. These factors are also vital elements to guarantee the competitiveness and sustainability of the Region, since they allow the design of tourist products that raise their comparative value proposition and respond in a complementary way to a changing tourist profile, from a tourist that instead of "go to", seek experiences that make him feel "part of".

The Lisbon 2020 document of CCDRLVT (2007), which, based on an exhaustive diagnosis, outlined a strategy for the development and affirmation of the Lisbon Region in Europe and in the World, highlights the Region as a destination for City Breaks and Touring; Business Tourism and Cruises and validates what has already been said that the Lisbon Region, besides having singular resources, enjoys the "complementarity between diverse motivations, attractions and products", extraordinary opportunities to become a competitive European Region. In this sense and specifically on the Peninsula of Setúbal, the document highlights the existence of high potential in the segments of "Golf, Residential Tourism, Sol & Mar and Nature Tourism.”

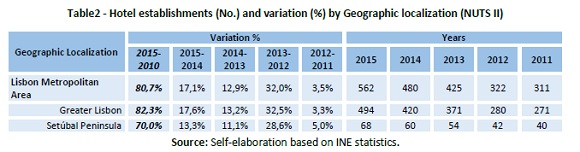

Regional offerConcerning the accommodation availability, the Lisbon Region has been able to develop a diversified and increasingly qualified offer, with hotels representing 42.2% of the Region’s hotel establishments in 2015 and 73% of accommodation capacity, meaning, an offer of 51,205 beds (INE, 2015).

Despite the increasing number of hotel establishments in the Lisbon Region in recent years (Table 2), it is observed that around 88% of them are concentrated in the sub-region of Greater Lisbon.

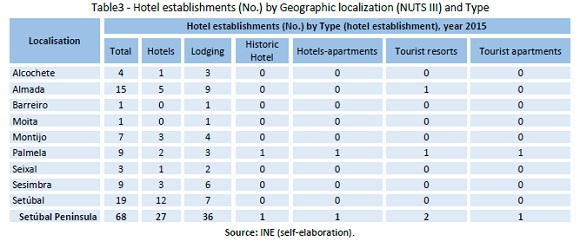

In the Setúbal Peninsula, accommodation capacity does not reach 11% of the existing supply in the Region, with an evident concentration in the municipalities of Almada and Setúbal (Table 3).

Also, at the gastronomic level, in the catering area and in response to an increasingly challenging market, a continuous improvement of the offer in recent years and investment in innovation was verified. According to data from the "Consumer Food Service in Portugal" (Euromonitor, 2016) related to the year 2015, trends such as "locally produced" and gourmet foods associated with the introduction of regional products and new products led to an improved menu, highly appreciated by tourists who tend to prefer traditional, typical establishments, whose offer is hugely varied.

The Setúbal Peninsula also has a number of natural areas (Tagus Estuary, Sado Estuary, Serra da Arrábida, Lagoa de Albufeira), ecological corridors (between Canha and Marateca, extending in the direction of Sesimbra), which constitute a potential for the development of nature tourism, with particular emphasis for dolphins and bird watching.

The region also has high agricultural and forestry potential (in particular in the municipalities of Montijo and Palmela), with conditions for the development of rural and housing tourism. All over the municipalities of the Peninsula, it is possible to find tourist companies that develop activities related to water, the outdoors, nature and environment, as well as culture.

Wine tourism is also an activity with great potential in the territory and has shown, in recent years, an increase significantly associated to the international recognition of the quality of the wines produced here, in consecutive years.

Horse breeding and the development of equestrian activities, such as equestrian education and horseback riding, are also offers that can develop Equestrian Tourism in this territory.

Despite the Peninsulas definite potential for tourism, which has been well illustrated, the Region has not been able to promote its singularities and the various tourist products effectively, nor has its environmental and natural preservation been appropriately valued, either by businesspeople or tourist agents. The transformation of resources into tourist products that can potentially make up an integrated offer, thus creating a genuine tourist destination, is lacking. The tourist demand in the Setúbal Peninsula can only grow when the destination indeed provides a distinctive and unforgettable experience to tourists and other visitors.

Tourist demandRegarding tourist demand, and despite the growth observed in recent years in the Lisbon Region as a whole, be it in the number of tourists, reflected in the growth of overnight stays and the increase in occupancy rates (Lisbon Tourism Observatory 2014, 2015, 2016), and in the revenues generated by the tourism sector, which include accommodation and catering and which represent approximately 4% of the Region’s GVA (Strategic Plan for Tourism of the Lisbon Region 2015-2019), the city of Lisbon has, in these indicators, a very expressive weight.

According to the mentioned Observatory, in 2015the Lisbon Region renewed the positive performance that has been registered in recent years in all the indicators considered, with Room Occupancy reaching 71.74% (an increase of 4.1 % compared to 2014); the Average Price per Room Sold (RevPor) reaching 83.13 euros (+ 13.9%) and the Average Price per Available Room (RevPar) to 59.64 (+ 11.9%). The year 2016, still with provisional data and only verified until November, also validates the growth trend: + 2% in Room Occupancy, + 7.3% in RevPor and + 9.4% in RevPar.

In a more detailed analysis, observing data from INE (Tourism Statistics, 2015), the Region accounted for about 25.3% of overnight stays in Portugal, ranking as the primary destination of the Brazilian market (60.0%), North-American (56.5%) and Italian market (53.4%), but also, and although with less relevance, the Belgian, Spanish, French, Swedish and Swiss markets. The average stay of tourists in hotel establishments was 2.34 nights, a decrease of 0.5% over the year 2014 nevertheless, lower than the variation registered in the country -1.7% (2.82 nights in 2014 for 2.77 nights in 2015).

The Lisbon Region also registered a net rate of bed occupancy in hotel establishments of 55.2%, standing above Portugals average, which was 47.3%.

The forecasts published by the World Tourism Organization estimate an annual growth rate in the number of international tourists of 4% by 2020 and the forecast by the consultancy Price-Water-House-Coopers (PwC) in its study "European Cities Forecast" states that Lisbon will be one of the five European cities that will most grow in the next two years, estimated to be the 2nd city with the highest growth expected in 2017.

This data, combined with what has been said about the complementary potential of the territory, indicates that the Lisbon Region, aiming to maintain its strong reputation, will develop a holistic and integrated approach, embodied in a portfolio of tourism products, with a strategy of branding and communication which asserts tourism in the Region, valuing the singularity, as well as the complementarity of its subregions, namely of the Setúbal Peninsula.

4.1.2 Enhance the attractiveness of the territory: which integrated strategies, products and services of the region.

The information shown in table 4 reflects the collection carried out in the focus group, with the objective of obtaining answers to the specific objectives: 2) to investigate how to enhance the attractiveness of this territory and 3) to identify its integrated strategies, products and services.

4.1.3 Availability for cooperation of the various stakeholders involved in the sector

The information presented in table 5 showsinterest and identifies the areas in which the focus group participants are available for cooperation, allowing a response to the specific objective: 4) observe the availability for the cooperation of the various stakeholders involved in the sector and 7) know the areas of intervention available for future cooperation projects.

4.1.4 The expected benefits of cooperation

The information presented in Table 6 describes the benefits resulting from the cooperation identified by the participants in the focus group. This information meets the specific objective: 5) to observe the expected benefits of this cooperation.

4.1.5. The constraints arising from cooperation

The information presented in Table 7 describes the constraints resulting from the cooperation identified by the participants in the focus group. This information answers the specific objective: 6) to understand the constraints of cooperation.

4.2 Discussion of results

The characterisation of the Setúbal Peninsula as an integrated territory in the Lisbon Region and the identification of important tourism allies in the territory such as accommodation, recreation and culture, natural spaces, gastronomy and wines allow us to recognise interesting potential. The results confirm the importance of the existence of a series of interrelated activities and of attractions that have to work harmoniously in order to make an experience that is valued by the tourist viable. Several authors (Pirjevec & Kesar, 2002; Fyall et al., 2012; Zach & Racherla, 2011) corroborate this idea.

On the other hand, these arguments, together with the opportunities revealed by the ERT, in particular regarding the development of sport and nature tourism, golf, residential tourism, ecotourism and agrotourism, the revitalization of crafts and culture, tourism sustainable development, thematic routes, inter- and intra-regional projects, confirm the potential of this activity as an instrument of economic, social and environmental development. Also, this idea regarding the importance of a tourism activity linked not only to economic values but also to social and environmental values is defended by a group of authors (Murphy, 1997; Marujo & Carvalho, 2010; Fons, Ferro & Patino, 2011; Park et al., 2012).

The data analysis, regarding the availability of the various stakeholders for cooperation in the tourism sector, makes it possible to understand that the interviewees perceive it as necessary in obtaining cooperation that allows the creation of new forms of tourism, new products and service packages. These agents also recognise the importance of cooperation as an instrument for improving and solving existing problems in the territory, in particular in regards to the transport network, promotion of the territory, relationship between public and private entities, as well as unemployment problems.

This availability and recognition of the importance of cooperation for the development of tourism and territory, is in line with the results of studies presented in the literature review, which show that cooperation can favour the perception of "total tourist product" and meet the expectations of the tourists in a very effective way, enabling sustainable tourism through the greater involvement between stakeholders (Albrecht, 2013). It also generates greater economic and social value to the communities and to the various stakeholders (Porter & Kramer, 2011; Bititci et al., 2004), reducing competition and contributing to the construction of shared values that allow environmental, social and cultural long-term management (Vaidyanathan & Scott, 2012; Pearce, 2015).

Regarding the expected benefits of cooperation, the results revealed that the interviewees recognize and identify a set of benefits, namely associated to the increase of the mutual knowledge of the various stakeholders and the sharing of experiences and learning that can lead to greater effectiveness and success of their actions: greater economies of scale, lower costs and greater visibility and notoriety of territories, strategies and projects.

These benefits are also seen as relevant in several studies presented in the literature review, particularly with regard to the aspects related obtaining lower costs and greater economies of scale (Mendonça et al., 2015), of significant improvements in the knowledge and skills, as well as in the increase of available resources (Mendonça et al., 2015 and Zach & Racherla, 2011) and consequently more business opportunities, namely through a greater and better supply of tourism products and more quality of services due to more efficient processes (Zach & Racherla, 2011; Zee &Vanneste, 2015).

With regard to the constraints arising from cooperation, there seems to be a collective consciousness about a set of difficulties that are essentially related to the existence of individual interests that make the focus on collective interests difficult; complex planning legislation often leading to inaction; excessive bureaucracy; lack of education and entrepreneurial conduct; lack of dialogue or sharing at various levels (resources, knowledge, etc.); fear of competition and little evidence of cooperation in the territory, or at least of its results. Also, many of these constraints are reinforced in the literature, particularly concerning self-interests and power relations that hinder a common and convergent view of joint ventures and increase competition, preventing a higher added value (Saito & Ruhanen, 2017). Similarly, the need for negotiating strategies between participants and determine the common purpose (Yin, Wu& Tsai, 2012) and expected right conduct from members and confidence on their competence (Das and Teng 2002) are pointed out in the literature review as essential constraints.

Besides, the lack of sharing knowledge, different communication styles and lack of trust are also corroborated by several studies (Zach & Racherla, 2011, Zee & Vanneste, 2015, Jesus & Franco, 2016 and Saito & Ruhanen, 2017). Finally, some of the constraints pointed out in the focus group (lack of considering the Setúbal Peninsula as a whole by the municipalities; the concept of "small farm" that still exists; the different language codes; the prevalence of a sense of competition”; at the regional level, the "neighbourhood” ethos and lack of dialogue"; the difficulties related to the management of people; lack of formation; the perception that "when one element fails, the whole system fails”) confirm the importance of certain conditions for cooperation, namely the role of governance in order to assure coordination and supervision of the network members (Sherer, 2003; Zafiropoulos et al., 2015). Also, constraints concerning lack of resources” confirm the importance of the amount of capital and knowledge-based investments in the network (Hoethker & Mellewigt, 2009). This is confirmed by the need pointed out by the focus group regarding the necessity of a facilitator and aggregator for the creation of products and services through cooperation, as well as the need for joint promotion of the territory using technological resources, as these actions reflect high costs related to the lack of coordination (Gulati & Singh, 1998).

5. Conclusions and final considerations

The literature review allowed a theoretical framework on tourism, development and cooperation, with particular emphasis on its benefits and constraints. By contextualising these topics in tourism, it was possible to find, in the empirical study, results that corroborate the various studies and perspectives presented.

In this way, this study shows the availability and interests of the main stakeholders of the tourism sector in the Peninsula of Setúbal regarding cooperation and, at the same time, assesses their interests regarding the development of future projects, while evaluating their perception of the benefits and constraints that are involved in cooperation.

The study confirmations the attractive worth of the territory of Setúbal as a tourist destination, reinforcing and highlighting its singularities and potential to become a region with a prominent tourist demand, from both national and international tourists. It was also possible to identify a set of action and management strategies based on differentiation, quality, innovation and sustainability, which emphasise the importance of affirming the identity of the Setúbal Peninsula. These distinctive strategies are mainly associated to unique tourism activities and products: the Sado Estuary and the Serra da Arrábida (nautical activities, nature and rural tourism); regional gastronomy and wines (Enoturismo); golf courses and beaches (beach tourism and historical and cultural heritage).

Finally, the consensual understanding of the importance of cooperation in this area, with very different characteristics and a great variety and disparity of projects, as well as the generalized awareness of the benefits and constraints of this cooperation, lead to understanding the urgency of continuing to raise awareness of this issue among the various stakeholders (economic agents and public entities, but also in the community, among others). This study and the workshops that have been carried out with the various stakeholders have contributed to the reawakening of an already existing awareness of the need for cooperation oriented towards results that can increase the region’s competitiveness and bring about widespread gains for all related parties. However, the recognised constraints indicate the need to continue promoting this type of awareness, either through concrete actions, such as workshops, seminars, conferences, training and qualification of human resources, but also the support for entrepreneurial activity in the tourism sector.

REFERENCES

Adair, W. A. & Brett, J. M. (2004). Culture and negotiation processes. In M. J. Gelfand & J. M. Brett (eds.), The Handbook of Negotiation and Culture (pp. 158-176). Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

Albrecht, J.N. (2013). Networking for sustainable tourism - towards a research agenda. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 21(5), 639-657. DOI: 10.1080/09669582.2012.721788 . [ Links ]

Bititci, U. S., Martinez, V., Albores, P. & Parung, J. (2004). Creating and Managing Value in Collaborative Networks. International Journal of Physical Distribution and Logistics Management, 34(3-4), 251-268. DOI: 10.1108/09600030410533576 . [ Links ]

Cao, M. & Zhang, Q. (2010). Supply chain collaborative advantage: a firms perspective. International Journal of Production Economics, 128, 358-367.DOI: 10.1016/j.ijpe.2010.07.037 . [ Links ]

Cao, M. & Zhang, Q. (2011). Supply chain collaboration: impact on collaborative advantage and firm performance. Journal of Operations Management, 29, 163-180. DOI: 10.1016/j.jom.2010.12.008 . [ Links ]

Cawleya, M., Marsatb, J.B. & Gillmor, D. (2007). Promoting Integrated Rural Tourism: Comparative Perspectives on Institutional Networking in France and Ireland. Tourism Geographies, 9(4), 405-420. DOI: 10.1080/14616680701647626 . [ Links ]

Das T.K. &Teng B.S. (2002). The dynamics of alliance conditions in the alliance development process. Journal of Management Studies, 39(5), 725- 756. DOI: 10.1111/1467-6486.00006 . [ Links ]

ERTL, Turismo de Lisboa. Plano Regional de Turismo de Lisboa 2015- 2019. Retrieved 24 October 2015 from https://www.visitlisboa.com/sites/default/files/2016-10/2015_19_Plano%20Estrat%C3%A9gico_0.pdf. [ Links ]

Euromonitor (2016). Retrieved 24 October 2015 from http://www.euromonitor.com/consumer-foodservice-in-portugal/report.

Fyall, A., Garrod, B., & Wang, Y. (2012). Destination collaboration: A critical review of theoretical approaches to a multi-dimensional phenomenon. Journal of Destination Marketing & Management, 1(1), 10-26. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jdmm.2012.10.002. [ Links ]

Fons, M., Fierro, J. & Patino, M. (2011). Rural tourism: a sustainable alternative. Applied Energy, 88, 551-557. DOI: 10.1016/j.apenergy.2010.08.031 . [ Links ]

Gabor, M. (2015). A content analysis of rural tourism research. Journal of Tourism, Heritage & Services Marketing, 1(1), 25-29. DOI: http://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.376327 . [ Links ]

Gulati, R. & Singh, H. (1998). The architecture of cooperation: managing coordination costs and appropriation concerns in strategic alliances. Administrative Science Quarterly, 43, 781-814. [ Links ]

Hoetker, G. & Mellewigt, T. (2009). Choice and performance of governance mechanisms: matching alliance governance to asset type. Strategic Management Journal, 30, 1025-1044. DOI: 10.1002/smj.775 . [ Links ]

Instituto Nacional de Estatística (2016). Estatísticas do Turismo 2015. Lisboa-Portugal: Instituto Nacional de Estatística.

Instituto Nacional de Estatística. Dados Estatísticos do Turismo. Retrieved 24 October 2015 from https://www.ine.pt/xportal/xmain?xpid=INE&xpgid=ine_base_dados . [ Links ]

Jesus, C. & Franco, M. (2016). Cooperation networks in tourism: A study of hotels and rural tourism. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 21(5), 639- 657. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jhtm.2016.07.005 [ Links ]

Kuittinen H., Kylaheiko K., Sandstrom, J. & Jauntunen, A. (2008). Cooperation governance mode: an extended transaction cost approach. Journal of Management and Governance, 4, 303-323. DOI: 10.1007/s10997-008-9074-5 .

Lemmetyinen, A. & Go, F. (2009). The key capabilities required for managing tourism business networks. Tourism Management, 30, 31- 40. DOI: 10.1016/j.tourman.2008.04.005. [ Links ]

Lisboa 2020 - Uma Estratégia de Lisboa para a Região de Lisboa. Retrieved 24 October 2015 from http://www.ccdr-lvt.pt/pt/documento-lisboa-2020/5093.htm. [ Links ]

Maga, D. (2010). Destinacijskimenadţment i sustavturističkihzajednica jovieraznolikosti. ČasopisUgostiteljstvo i turizam, 4, 27-29.

Marujo, M. & Carvalho, P. (2010). Turismo, planeamento e desenvolvimento sustentável. Turismo & Sociedade, 3(2), 147-161. [ Links ]

Mendonça, V., Varajão, J. & Oliveira, P. (2015). Cooperation networks in the tourism sector: multiplication of business opportunities. Procedia Computer Science, 64, 1172-1181. DOI: 10.1016/j.procs.2015.08.552 [ Links ]

Murphy, P. (1997). Tourism: a community approach. Oxford: International Business Press. [ Links ]

Park, D., Lee, K., Choi, H & Yoon, Y. (2012). Factors influencing social capital in rural tourism communities in South Korea. Tourism Management, 33, 1511-1520. DOI: 10.1016/j.tourism.2012.02.005. [ Links ]

Patton, M. Q. (2002). Qualitative Research & Evaluation Methods, USA: Sage Publication. [ Links ]

Pearce, D. G. (2015). Destination management in New Zealand: Structures and functions. Journal of Destination Marketing & Management, 4 (1), 112. [ Links ]

Petrou, A., Fiallo Pantzioua, E., Dimaraa E. & Skuras, D. (2007). Resources and activities complementarities: the role of business networks in the provision of integrated rural tourism. Tourism Geographies, 9(4), 421-440. DOI: 10.1080/14616680701647634. [ Links ]

Pirjevec, B. & Kesar, O. (2002.). Počelaturizma. Zagreb: Mikroradd.o.o.

Porter, M. & Kramer, M. R. (2011). Creating shared value. Harvard Business Review, 89(1-2), 62-77. [ Links ]

Saito, H. & Ruhanen, L. (2017). Power in tourism stakeholder collaborations: Power types and power holders. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Management, 31, 189-196. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jhtm.2017.01.001 [ Links ]

Sherer, S.A. (2003). Critical success factors for manufacturing networks as perceived by network coordinators. Journal of Small Business Management, 41(4), 325-345. DOI: 10.1111/1540-627X.00086 [ Links ]

Sfandla, C. & Bjork, P. (2013). Tourism experience network: cocreation of experiences in interactive processes. International Journal of Tourism Research, 15(5), 495- 506. DOI: 10.1002/jtr.1892 [ Links ]

Stake, R. E. (2010). Qualitative research: studying how things work. USA: The Guillford Press. [ Links ]

Turismo 2020 - Plano de ação para o desenvolvimento do turismo em Portugal 2014-2020. Retrieved 24 October 2015 from http://estrategia.turismodeportugal.pt/sites/default/files/Turismo2020_Parte%20I_mercados%20-%20SWOT.pdf. [ Links ]

Turismo de Lisboa. Observatório do Turismo de Lisboa (2014). Retrieved 24 October 2015 from https://www.visitlisboa.com/pt-pt/about-turismo-de-lisboa/observat%C3%B3rio.

United Nations (1987). Our Common Future, World Commission on Environment and Development, A/RES/42/187, General Assembly, 96th plenary meeting. Retrieved 24 October 2015 from http://www.un.org/documents/ga/res/42/ares42-187.htm . [ Links ]

United Nations (1992). United Nations Conference on Environment & Development, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 3 to 14 June 1992, AGENDA 21.Retrieved 24 October 2015 from https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/content/documents/Agenda21.pdf. [ Links ]

Vaidyanathan, L., & Scott, M. (2012). Creating shared value in India: The future for inclusive growth. The Journal for Decision Makers, 37(2), 108- 113. [ Links ]

World Tourism Organization (2016). UNWTO Annual Report 2015, Madrid: UNWTO. [ Links ]

Yasuo, O. & Shinichi, K. (2013). Evaluating the complementary relationship between local brand farm products and rural tourism: Evidence from Japan. Tourism Management, 35, 278-283. DOI: 10.1016/j.tourman.2012.07.003. [ Links ]

Yates, J. & Leggett, T. (2016). Qualitative research: an introduction. Radiologic Technology, 88(2), 226. Retrieved 24 October 2015 from http://www.radiologictechnology.org/content/88/2.toc. [ Links ]

Yin, R. K. (2003). Case study research: design and methods. USA: Sage publications. [ Links ]

Yin, R. K. (2011). Qualitative research from start to finish. New York, USA: The Guillford Press. [ Links ]

Zach, F., & Racherla, P. (2011). Assessing the value of collaborations in tourism networks: a case study of Elkhart County, Indiana. Journal of Travel & Tourism Marketing, 28(1), 97-110. DOI: 10.1080/10548408.2011.535446 . [ Links ]

Zafiropoulos, K., Vrana, V. & Antoniadis, K. (2015). Use of Twitter and Facebook by top European museums. Journal of Tourism, Heritage & Services Marketing, 1(1), 16-24. DOI: http://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.376326 [ Links ]

Zee, E. &Vanneste, D. (2015). Tourism networks unravelled: a review of the literature on networks in tourism management studies. Tourism Management Perspectives 15, 46-56. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.tmp.2015.03.006. [ Links ]

Received: 12.04.2018

Revisions required: 20.07.2018

Accepted: 23.09.2018