Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Acessos

Acessos

Links relacionados

-

Similares em

SciELO

Similares em

SciELO

Compartilhar

Tourism & Management Studies

versão impressa ISSN 2182-8458versão On-line ISSN 2182-8466

TMStudies vol.14 no.4 Faro dez. 2018

https://doi.org/10.18089/tms.2018.14402

TOURISM: SCIENTIFIC PAPERS

Memorable Tourism Experience (MTE): a scale proposal and test

Experiência Turística Memorável: proposição e teste de escala

Mariana de Freitas Coelho1, Marlusa de Sevilha Gosling2

1Universidade Anhembi Morumbi, Brazil, marifcoelho@gmail.com

2Federal University of Minas Gerais, Brazil, mg.ufmg@gmail.com

ABSTRACT

This paper aims to propose and test a scale to assess Memorable Tourism Experiences (MTE). It presents an instrument initially containing 49 tested items, organised into 12 dimensions: Environment, Culture, Relationship with Companions, Relationship with Tourists, Relationship with Local Agents (residents and service providers), Novelty, Emotions, Dream, Meaningfulness, Refreshment, Hedonism and Involvement. Data collection included a survey of 1,193 Brazilians with regular travel habits, aged from 18 years old. Data were analysed quantitatively via Structural Equation Modelling. Statistical tests of Exploratory Factor Analysis (EFA) followed the Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA). The results indicate that the scale is reliable and valid for the study of MTEs, at least for the studied sample. It attests to the multidimensionality of MTE construct, but Hedonism and Involvement are not appropriate dimensions. Thus, it confirmed the validity of the new MTE scale consisting of 35 items and ten dimensions of the second- order construct.

Keywords: Dimensions of the memorable tourism experience, environment and culture, interpersonal relationships, psychological dimension, confirmatory factorial analysis.

RESUMO

O objetivo desse artigo foi propor e testar uma escala destinada a avaliar Experiências Turísticas Memoráveis (MTE). Elaborou-se um instrumento inicialmente contendo 49 itens testados, organizados em 12 dimensões: Ambiente, Cultura, Relacionamento com Acompanhante, Relacionamento com Turistas, Relacionamento com pessoas Locais, Novidade, Emoções, Sonho, Significância, Renovação, Hedonismo e Envolvimento. A coleta de dados incluiu um survey com 1193 brasileiros com hábito de viagem e idade superior a 18 anos. Os dados foram analisados quantitativamente via Modelagem de Equações Estruturais. A Análise Fatorial Exploratória foi seguida de testes estatísticos da Análise Fatorial Confirmatória. Os resultados indicam que a escala demonstra-se confiável e válida para o estudo de MTEs para a amostra estudada. Comprovou-se a multidimensionalidade da MTE, mas Hedonismo e Envolvimento não são dimensões apropriadas, ao menos no estudo proposto. Logo, confirmou-se a validade de uma nova escala de MTE composta por 35 itens e 10 dimensões que são relativas ao construto de segunda ordem.

Palavras-chave: Dimensões da experiência turística memorável, ambiente e cultura, relações interpessoais, dimensão psicológica, análise fatorial confirmatória.

1. Introduction

Memorable Tourism Experience (MTE) requires the individual evaluation of the tourism experience (Kim, Ritchie & McCormick, 2012). MTE refers to the memory of visitors, particularly their feelings and emotions experienced during a tourism activity (Lee, 2015).

Based on the fact that both the tourism experience and the process of memory generation are the basis of MTEs (Coelho, 2017), not every tourism experience is memorable. MTEs seem to relate to individual choices, which tourists feel their activities are worth (Morgan, 2010). There are also indications that MTEs highlight, above all, positive experiences (Tung & Ritchie, 2011a).

Whether in qualitative or quantitative studies, MTE is a complex and multidimensional phenomenon, which is composed of several representative dimensions for the tourism experience. Several studies have proposed and measured the dimensions of MTE, such as Aroeira, Dantas, and Gosling (2016); Kim (2012, 2014); Kim and Ritchie (2014); and Kim et al. (2012) attesting to the multidimensionality of MTE. However, until then, MTE scales were ruled, especially in psychological characteristics of the tourism experience, such as Kim, Ritchie, and McCormick (2012), Kim and Ritchie (2014), Aroeira et al. (2016) and Tsai (2016).

Thus, the contribution of this study involves the proposition and test of an MTE scale that addresses the phenomenon more holistically. Theoretical models of tourism experiences not memorable experiences - such as Quinlan-Cutler and Carmichael (2010) and Walls, Okumus, Wang, and Kwun (2011) help on the proposed scale. It confirms that in addition to psychological factors (novelty, dream, emotions, refreshment and meaningfulness), cultural and environmental factors (local culture, attractions), as well as inter-relational factors (tourist-local agents, tourist-tourists and tourist-travel companions) also determine the memorability of the tourism experience. The study aims to propose and test a scale to assess MTEs in the Brazilian context, which addresses psychological factors alongside cultural, environmental and interrelational factors of MTE.

2. Literature Review

2.1 Memorable Tourism Experience (MTE)

Several authors have studied the MTE as a complex subject; in general, these authors indicate a plurality of dimensions inherent to it. Qualitative studies include the different categories of the MTE. Meanwhile, scales and theoretical models also follow similar directions. Nevertheless, there is no consensus among authors on what really makes some experiences more memorable than others.

Pioneers in the study of MTEs were Tung and Ritchie (2011a), who proposed a qualitative study in four dimensions of the memorable trip: affection, expectations, consequentiality and recollection. Affection includes positive emotions like happiness and excitement; in other words, critical components of the memorable experience. Expectations involve unexpected events and surprises for tourists. Consequentiality refers to trip outcomes perceived as important, such as progress in social relations, intellectual development and personal discovery. Recollection involves memories, photographs and stories to remember the trip. In the study of Tung and Ritchie (2011a), affection and expectations can be included in the psychological dimension of MTE, recollection is related to the memorability of the experience, and consequentiality can be seen as one of the MTE outcomes.

By studying the antecedents and consequences of the tourism experience with wild marine animals in Australia, Ballantyne, Packer, and Sutherland (2011, p. 770) sought to understand what led the tourists to have memorable experiences in these places. Four themes from the experience of visitors identified by the authors implied four processes: “1) what visitors actually saw and heard (sensory impressions), 2) what they felt (emotional affinity), 3) thought (reflexive response), and finally, 4) what they did about it (behavioural response)”. In this sense, the authors also focused mainly on the psychological dimension of MTE (sensory impressions, emotional affinity and thoughts), but also considered an MTE outcome (behavioural response).

From the perspective of quantitative studies, there are those grounded on the four domains of the experience of Pine and Gilmore (2011), assuming that the MTE is based at least on entertainment, escapism, aesthetics and education (e.g., Manthiou, Kang, Chiang, & Tang, 2016; Oh, Fiore, & Jeoung, 2007; Pezzi & Vianna, 2015; Song, Lee, Park, Hwang, & Reisinger, 2015).

There is also a widely used MTE scale by Kim et al. (2012), composed of 24 items and seven dimensions, which is based on Kim’s (2010) studies. Similarly, Kim and Ritchie (2014) developed a cross-country study (the USA and Taiwan) and assessed that hedonism, novelty, local culture, refreshment, meaningfulness, involvement and knowledge are dimensions of the MTE intention, preceding behavioural intention, which is the intention to recommend the destination or to revisit it. Kim (2014) shows the relationship between the attributes of a tourism destination and the MTE.

In the Brazilian context, Aroeira et al. (2016) point out that hedonism, involvement, novelty, local culture and knowledge, and refreshment are dimensions of the MTE. Thus, the proposed scale from the studies of Kim et al. (2012) demonstrated a fusion of the local culture dimension with the knowledge dimension, and meaningfulness was not considered significant in the Brazilian study.

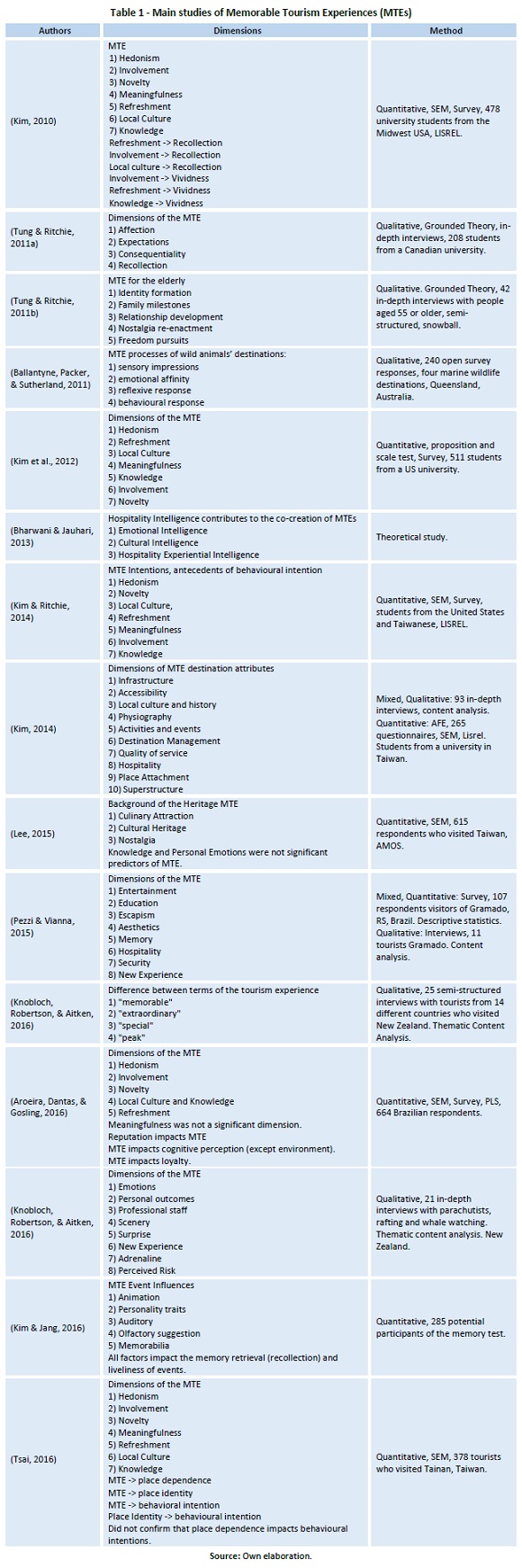

Lee (2015) found out that culinary attraction, cultural inheritance and nostalgia impact MTE of visitors of the Tainan Railway Station in Taiwan. Knowledge learning and personal emotions were not significant predictors of MTE in the studies of Lee (2015), which demonstrates the need for further studies on the antecedents of MTE in specific contexts. Table 1 lists the leading studies on MTE with a summary of the dimensions, as well as the adopted method of each study.

Table 1 demonstrates how researchers commonly address MTE as a multidimensional construct. Also, there are qualitative and quantitative studies on the subject, with an advance in proposals and tests of scales in the last eight years. In some cases, the proposed dimensions present similarities. However, it is necessary to discuss the interdependence of the environmental, cultural, social and personal factors of the tourism experience, although they are recurrent factors in the literature of (broader) tourism experiences.

For example, Arnould and Price (1993) associate satisfaction of rafting adventure experiences with the connection to nature (environment), connection with others (interpersonal relationships) and self-refreshment (psychological and individual dimensions). Thus, the tourism experience associates with multiple interpretations, which permeate the environment, social relationships, and other components of the activity (Tussyadiah & Fesenmaier, 2009).

Finally, recent studies point to the prospect of finding the antecedents and consequences of the MTE. Therefore, the scale proposed in this study incorporates the dimensions as being interdependent and connected to the MTE. Moreover, it also tests the environmental, cultural, social and personal factors of the MTE, which is still a gap in MTE scales.

3. Method

The study aimed to propose and test a scale to assess MTEs. Therefore, we adopted a quantitative approach based on multivariate data analysis. Data were analysed using structural equation modelling software in Amos Graphics (CB-SEM), which involved a set of techniques and statistical tests aimed at proposing an exploratory model (Kline, 2011). The research universe is formed by Brazilians who have participated in at least one MTE in their life.

3.1 Sample

The sample consisted of 1,187 valid questionnaires and was nonprobabilistic, with some criteria set by the researchers. The criteria for voluntary participation in the study involved the need to be: a) Brazilian, over 18 years of age; b) have travelled at least once for leisure in the 24 months prior to data collection, and c) remember a memorable trip the respondent had already made to any national or international destination.

The sample complied with the recommendation of Hair, Anderson, Tatham, and Black (2005) to collect at least five times more observations than the number of variables to be analysed. The proportion of cases per variable in the study was 24.2, higher than the recommended number in the literature.

3.2 Instrument

This research assumes that the MTE is a second-order, multidimensional construct, according to studies indicated in the literature review. The research instrument is based on the study of Coelho (2017), which was supported by both qualitative studies and tested scales, already adapted to the Brazilian context. For the author, MTEs relates to tourists’ experiences with the environment, culture, interpersonal relationships and psychological perceptions. Besides, part of the scale, which included the dimensions Hedonism, Refreshment, Meaningfulness, and Involvement, had already been translated from the studies of Kim et al. (2012) and tested in the national context by Aroeira et al. (2016). A part of the items of the culture and novelty scales was translated by Aroeira et al. (2016), and other items were proposed and tested by Coelho (2017), such as Dream, Emotions, Relationship with Companions, Relationship with Tourists, and Relationship with Local Agents.

The knowledge dimension was excluded from the MTE scale based on studies by Aroeira et al. (2016), which indicated the merge of knowledge and local culture dimensions, indicating contextual features. The survey instrument also went through a pre-test, conducted with nine experts in tourism and marketing, which indicated, in writing, corrections and suggestions set out in the variables and pre-textual elements of the questionnaire. Also, 1,249 individuals responded to a pilot survey with the objective of scale refinement, as well as the test of the measurement model, confirming the exclusion of knowledge as an MTE dimension. Therefore, the final data collection (topic 3.3) took place without the knowledge dimension.

A 7-point Likert scale anchored all items. In other words, the respondents had a choice ranging from 1 to 7, with 1 being ‘strongly disagree’ and 7 ‘strongly agree’. The operation of each construct follows the guidelines of authors such as Hair et al. (2005) and Malhotra (2006) for research conduction, using multivariate data analysis. All scales were forced, without the response option ‘do not know’, in order to verify the perception of respondents about their trips.

3.3 Data Collection

The sample was non-probabilistic, collected through a survey according to the accessibility to the respondents. It took place online for three months of 2017 and used Google Docs. More than 3,000 emails were sent to educational institutions and included education and research centres, universities and colleges from all degrees. There was no restriction on the type of course or area of study. We requested that the contacts of educational institutions disseminate the research internally, either for employees, students or alumni.

The questionnaires were self-report and the survey guaranteed responses from residents of all five Brazilian regions, and from each of the 27 federative units of the country. Brazilians who live abroad were also considered and could respond to the questionnaire. This strategy was evaluated as positive because it was able to reach people who go beyond the personal contact of authors and/or students of a single educational institution, which is usually an emphasis of academic research. Thus, the data collection process has optimised the distribution of the questionnaire and fulfilled the goal to generate a variability of respondents.

Questionnaires have gone through a rigorous procedure of answer review. We removed any evidence of questionnaires with duplication problems, unique responses and fraud. The sample had 1,193 answers and six excluded cases, totalling 1,187 valid answers. A Google Docs feature required every questionnaire response, eliminating missing data from the data collection.

3.4 Data Analysis

The Structural Equation Modelling is suitable for situations to test large-scale relationships (Hair et al., 2005). Besides Structural Equations Modelling, data analysis was supported by the software Microsoft Excel, SPSS and Amos. Data analysis had four distinct stages. First, after database preparation, the assumptions of the multivariate analysis were tested (Hair et al., 2005).

In a second stage, an Exploratory Factor Analysis (EFA) aimed at verifying the MTE factors and reducing the number of indicators (questionnaire items). The third procedure involved a Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA), and enabled the validation of the proposed scale, as shown in the results.

4. Results

4.1 Assumptions of Multivariate Analysis

Some tests were performed aiming to adapt the data to the general linear model, according to recommendations of Hair et al. (2005). Database presented no multicollinearity and singularity problems. Outlier analysis indicated 95 univariate atypical cells were identified. Following the recommendation of Hair et al. (2005), all cases were maintained, since none was very different from the rest of the sample. That is, no case (set of responses of each who answered the questionnaire) presented more than eight cells of atypical observations. This action is also important for increasing the generalisation capacity of the model, although non-probabilistic sampling is a limitation of this research.

We used the criterion of kurtosis and skewness for assessing the normality, whose values should be less than 3 for skewness and less than 10 for kurtosis (Kline, 2011). All skewness values were negative and significant, with variations between -0.526 and -2.427. The kurtosis values ranged from -1.616 to 7.236. Thus, these tests ensured the data were adequate for the use of SEM and the proceed with the EFA.

4.2 Exploratory Factor Analysis (EFA)

EFA has two central purposes in the study: the first is the verification if the latent variables are unidimensional. That means that each construct used in the model has been tested for the number of dimensions which specify it.

The second is the removal of observed variables (questionnaire items) that did not add to the scale composition. Thus, EFA reduces the number of variables in a database, in order to maximise the explanatory power of a set of variables (Hair et al., 2005).

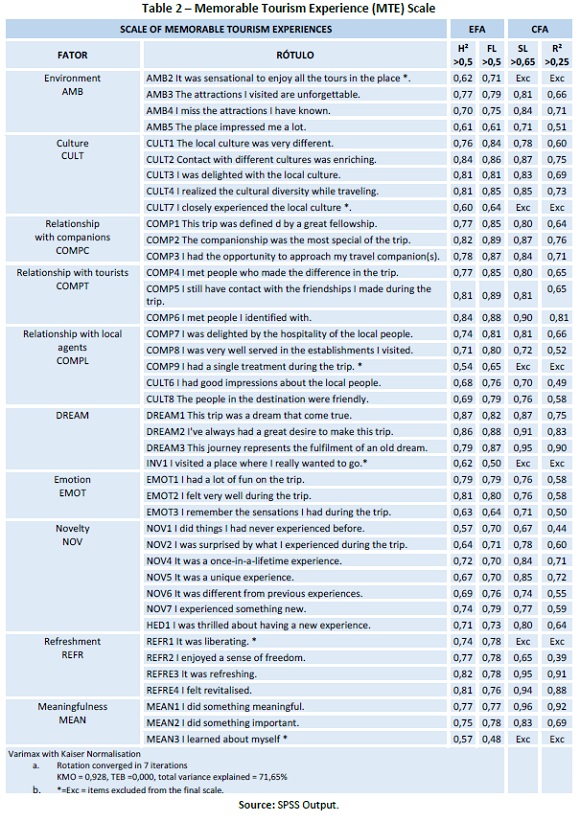

MTE is a complex variable and has already been studied as a multifactorial construct in previous studies. Hence, initially, we expected 12 factors adjacent to the MTE, but only 10 were confirmed. The factorial solution presented in Table 2 demonstrates the existence of 10 factors, with Hedonism and Involvement having a different pattern from that proposed by Kim et al. (2012). Table 2 shows that the MTE construct is multidimensional and composed of 10 distinct dimensions, whose names were proposed by the authors. It also shows the labels, commonalities (H²) and Factorial Loadings (FL) of each of the construct’s items, divided into factors. All values are within the recommended in the literature, which ensures the presented factorial solution. The table also presents data from the CFA of the standardised loadings (SL) and squared multiple correlations (R²) of the items maintained in the scale.

We used the extracting method of principal components and varimax rotation method. The principal component analysis is preferable when seeking to summarise the variance in a minimum number of factors (Hair et al., 2005). The varimax rotation is orthogonal, which is suitable when the research aims to reduce the number of original variables (Hair et al., 2005). The KMO test showed the excellent suitability of the sample for the application of EFA, based on the value greater than 0.9.

Thus, the result of the factorial solution showed a reduction of 12 initial MTE factors to 10 factors, a reduction from 49 to 41 items and a total variance explained of 71.65%. The hedonism dimension was excluded from the study, because the items hed1, hed2, and hed3 were removed for not aggregating in the analysis. Moreover, the items amb1 and cult5 nov3 were removed by low commonality (0.44 and 0.45, 0.38 respectively). Moreover, inv1 and inv2 have been removed in the pre-test for model adequacy of index adjustment.

4.3 Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA)

To evaluate the reliability and validity of the measurement model, we run the CFA. The CFA is used to ensure the quality of the adjustment of a theoretical measurement model to the correlation structure between the items (Marôco, 2014).

The CFA was performed with the statistical package Amos (v.21.0). We chose to use the input matrix as ML (Maximum Likelihood), in which the estimates maximise the probability of the data being withdrawn from the population. Therefore, this method presents estimates that are efficient and consistent in large samples as long as both the statistical requirements and the model are correctly specified (Kline, 2011, p. 155).

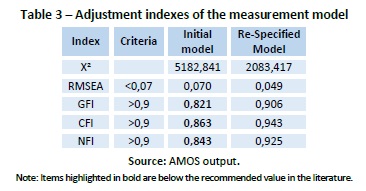

After the theoretical model estimation, we performed the validity test and scale adjustments. A first activity necessary to evaluate the measurement model involves ascertaining the adjustment indexes of the model. The adjustment test of the proposed model was based on the analysis of the data of the fit indexes of Table

3. The evaluation of the index of adjustments of the initial model indicated the need to continue with the model refinement, according to the literature guidelines (Table 3). In order to improve the adjustments of the initial model, we followed a two- step analysis procedure. Firstly, we evaluated the standardised loading and the R² of the observed variables (items) of the model according to Marôco (2014), R² values lower than 0.25 indicate possible adjustment problems with this variable, given the ability to explain less than 25% of it. The variables amb2, comp9, cult7, inv1 and refr1 were extracted due to the standardised loadings below 0.65 (0.64, 0.6, 0.64, 0.575, 0.64).

Modification indexes (MI) of the model were also used to correlate the errors with values of MI above 20 when in the same variable. Therefore, the model re-specification extracted five variables and added 10 correlations among errors of items of the novelty construct and another three correlations between errors of the relationship with local agents construct. With this, we obtained a significant improvement in the adjustment indexes of the re-specified model, concerning the data obtained in the initial model. The values of the RMSEA, CFI, NFI and GFI indices of the re-specified model are above the value recommended by the literature, according to Table 3. Also, Table 2 shows the factor loadings and squared multiple correlations coefficients of each item of the final model, all loadings being statistically significant.

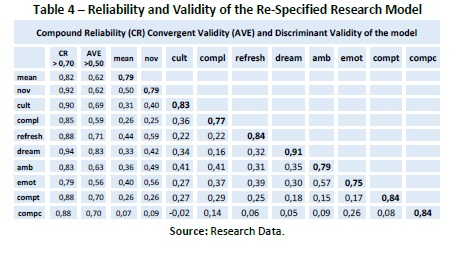

Among the tests, the composite reliability is responsible for measuring the extent to which there is internal consistency between the variables. That is, it evaluates the reliability of each model of the construct as its consistency replication capacity (Marôco, 2014). The convergent validity contributes to the degree of explanation of the indicators sharing constructs converge or variances (Hair et al., 2005). It shows when the constructs present positive and elevated correlations among themselves (Marôco, 2014). Moreover, the discriminant validity is necessary to demonstrate the degree to which a construct differs from the other constructs of the model, i.e., if they are different or similar (Hair et al., 2005).

Table 4 presents the results of the composite reliability (CR) and convergent validity (AVE) and discriminant validity of the re- specified research model, indicating validity and reliability in the model.

Notes: CR values were above 0.70, AVE values were greater than 0.50. The values in bold are higher than the other items in the column, which indicates discriminant validity.

Thus, the MTE scale presented is formed by 10 factors (Environment, Culture, Relationship with Companions, Relationship with Tourists, Relationship with Local Agents, Novelty, Emotions, Dream, Meaningfulness, and Refreshment) and 35 items of the MTE, a second-order and multifactorial construct.

5. Discussion

The results reinforce the need to address the MTE from a broader perspective, as by looking for tourism experience studies. One of the dimensions addressed in tourism experience study is the physical environment, including the natural and built environment and the tourist attractions of the tourism destination. Pine and Gilmore (2011) and Oh et al. (2007) highlight the importance of the aesthetic dimension of experience, which involves all aspects of the environment perceived by tourists and hasn’t been evoked in previous scales such as those of Kim et al. (2012). The involvement of tourists in the experiences comes from the observation of the environment and the sensations and feelings arising from external stimuli (digital objects, non-digital objects, music, etc.) (Tung, Lin, Zhang Qiu, & Zhao, 2016).

The immersive and non-routine experience allows for the unfolding of the relationship between an individual and the environment, enabling the development of meaningful interactions between the two parties (Davis, 2016). Tourist environmental aspects include various natural and man-made elements as the geographical dimension (space and place) (Pearce, 2014), servicescape, hardware, and service systems (Komppula, Ilves, & Airey, 2016), design attractiveness, layout/ease of navigation, upkeep and physiological ambience (Walls, 2013), signs and visual communication (Tussyadiah & Fesenmaier, 2009).

The environment was also the most critical dimension for hotel guest experiences, according to Walls (2013). The environmental attributes allied to management decisions are mediators of the destination experience, besides the destination choice present a significant influence on the likelihood of a satisfying experience (Breejen, 2007). Relationships between tourists and the environment are built through attachment and feeling of belonging to a place (Davis, 2016).

The cultural dimension is longer as discussed and demonstrated significant in MTE studies. Cultural considerations and local activities as well as previous experiences of clients impact on the way in which individuals perceive the experience (Pine & Gilmore, 2011). Visitors who interact with local culture build a unique and memorable travel experience (Kim & Ritchie, 2014).

It is also known that the degree of empathy and shared cultural proximity between travellers and employees influence the delivery of the tourism experience (Bharwani & Jauhari, 2013). Bharwani and Jauhari (2013) suggest that the cultural orientation between the employee and the client can be very distinct, demanding employees who are sensitive to the values and expectations of global consumers. Thus, to experience the local culture, whether, through cooking, crafts, dance, language, a way of life, values and other cultural expressions can impact on the tourism experience.

The study highlights the interpersonal dimension, which incorporates the relationship between people. Tourism experience literature refers to the interpersonal influences, but this is less explored in MTE studies. Schmitt (2000) considers that one of the providers of experience is attributed to the contact or observation of other individuals. To Tussyadiah and Fesenmaier (2009), the involvement between people usually works as a mediator of the tourism experience, allowing the interpretation, sharing and re-signification of the trip.

Schmitt (2000) emphasises that interpersonal interaction can be positive or negative and is highly recommended in complex services such as tourism. Findings of Jennings et al. (2007) suggest that the key elements for the quality of adventure experiences for young people lie precisely in the interaction between people, either in an individualised or social perspective.

Several authors have stressed the importance of people to the tourism experience (Caru & Cova, 2003; Komppula et al., 2016; Quinlan-Cutler & Carmichael, 2010; Walls, 2013), but this study shows that for a tourism experience to be memorable, at least the relationships between tourist-local agents, tourist-tourists and tourist-companions are significant.

Studies have shown that personal characteristics, past experiences and previous motives can affect the results of the experience. Among the MTE scales, the most outstanding items of the authors affecting memorability of experience are precisely the psychological factors of who lived it. Six of the seven dimensions of MTE proposed by Kim et al. (2012) and Kim and Ritchie (2014) refer to the psychological, personal and cognitive aspects of the tourists: novelty, involvement, refreshment, meaningfulness, hedonism and knowledge. Besides psychological factors, the only culture is evaluated as significant for a memorable experience on their scale. On the one hand, this demonstrates the importance of individual factors to tourism experiences. On the other, it reinforces the need to incorporate new dimensions in MTE studies.

The scale tested here goes beyond the psychological dimension attested in previous studies and confirms the following dimensions/factors: 1) traveller’s emotions and 2) dream or desire to visit a tourist destination. Emotions are the focus of discussions of experience studies (Matos, 2014). Emotions are emotional states generated by specific stimuli (Schmitt, 2000). The emotion in tourism experiences in parks was also measured by Andreu, Gnoth, and Bigne (2005), demonstrating that it is composed of two dimensions: pleasure and enthusiasm (excitement). The authors also proved that emotions impact on visitor satisfaction and loyalty.

Finally, dreams are part of the activities that can lead people to grow and lead a happy life (Sirgy, 2012) and can be one of the travel motivations (Damijanić & Sergo, 2013). To visit a tourist destination, in particular, can be seen as the fulfilment of a dream or old wish (Matteucci & Filep, 2015), sometimes not realised due to constraints such as time and financial resources (Karl, Reintinger, & Schmude, 2015). Diverse tourism experiences such as parachute jumping, whale watching and river rafting can be the great fulfilment of a dream, or just part of a spontaneous activity that affects the individual experience (Knobloch et al., 2016). Thus, MTEs are known to be multidimensional and complex, requiring further investigation.

6. Conclusion

This work attests to the multidimensionality of MTE, proving that the dimensions of previous scales can be refined and some aspects previously neglected in MTE studies as the physical environment; relationship with companions, tourists, and local agents; as well as dreams and emotions are dimensions of the MTE. The scale proposed in this study goes beyond the psychological dimension proposed in previous studies and covers environmental, cultural and interrelational factors as necessary to the memorability of tourism experiences.

Because it is an exploratory model and tested only in a non- probabilistic sample with Brazilians, it is still possible to improve this scale and improve the fit indexes. One of the concerns is related to dimensions already proven in other studies such as Hedonism and Involvement, which did not add to the study sample, demonstrating possible cultural factors that interfere with MTEs. Moreover, the factor of meaningfulness is composed of only two indicators, which is not desirable and deserves further investigation. Future studies can perform tests with the proposed scale in different cultural contexts and cross- country studies in order to contribute to the refinement and validation of the scale.

Finally, the MTE studies can contribute to improving the quality of tourism services once an essential indication of the study is the need for managers to identify the tourist’s dreams and provide innovative products/service. To establish possible points of interaction between customers and local people should also be considered in the manager’s strategies. Providing information and highlighting local cultural aspects such as history, arts, slangs, souvenirs and cuisine could enhance tourist experience and place attachment. Such actions can provide more remarkable experiences to tourists and could generate intentions to recommend and return to the destination.

For travellers, this study can help with destination planning and choice. Tourists should be aware of their dreams and emotions before and during their travel experience, once they can evoke memorable experiences. Travellers should reflect on their past experiences and do at least minor research about destination culture and environment before choosing a destination. The closer an experience might be to a previous one, less novelty will unfold, providing a rather ordinary experience instead of a memorable one. Also, not only will their companionship affect their trips, but the contact with local agents and tourists might underlie remarkable moments that might become meaningful for their lives.

REFERENCES

Andreu, L., Gnoth, J., & Bigne, J. E. (2005). The theme park experience: An analysis of pleasure, arousal and satisfaction. Tourism Management, 26(6), 833-844. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2004.05.006 [ Links ]

Arnould, E. J. & Price, L. L. (1993). River magic: Extraordinary experience and the extended service encounter. Journal of Consumer Research, 20(1), 24. http://doi.org/10.1086/209331 [ Links ]

Aroeira, T., Dantas, A. C., & Gosling, M. (2016). Experiência Turística Memorável, Percepção Cognitiva, Reputação E Lealdade Ao Destino : Um Modelo Empírico. Revista Turismo Visão e Ação, 18(3), 584-610. [ Links ]

Ballantyne, R., Packer, J., & Sutherland, L. A. (2011). Visitors’ memories of wildlife tourism : Implications for the design of powerful interpretive experiences. Tourism Management, 32(4), 770-779. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2010.06.012

Bharwani, S. & Jauhari, V. (2013). An exploratory study of competencies required to co-create memorable customer experiences in the hospitality industry. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 25(6), 823-843. http://doi.org/10.1108/IJCHM-05-2012-0065 [ Links ]

Breejen, L. D. (2007). The experiences of long distance walking: A case study of the West Highland Way in Scotland. Tourism Management, 28(6), 1417-1427. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2006.12.004 [ Links ]

Carù, A. & Cova, B. (2003). Revisiting consumption experience: A more humble but complete view of the concept. Marketing Theory, 3(2), 267- 286. http://doi.org/10.1177/14705931030032004 [ Links ]

Coelho, M. de F. (2017). Viagens De Brasileiros: Um Modelo De Relações Entre Experiência Turística Memorável, Mindfulness, Transformações Pessoais E Bem-Estar Subjetivo. Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais.

Coelho, M. F., Gosling, M. S., & Berbel, G. (2016). Atratividade de destino turístico: a percepção dos atores locais de Ouro Preto, MG , Brasil. PASOS- Revista de Turismo e Patrimônio Cultural, 14(4), 929-947. [ Links ]

Damijanić, A. T. & ergo, Z. (2013). Determining travel motivations of wellness tourism. Ekonomska misao i praksa, 1, 3-20.

Davis, A. (2016). Experiential places or places of experience? Place identity and place attachment as mechanisms for creating festival environment. Tourism Management, 55, 49-61. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2016.01.006 [ Links ]

Hair, j. F. J., Anderson, r. E., Tatham, r. L., & Black, W. (2005). Análise Multivariada de Dados. Porto Alegre: Bookman. [ Links ]

Jennings, G.R., Lee, Y-S., Ayling, A., Ollenburg, C., Carter, C. and Lunny,B. (2007). What do Quality Adventura Tourism Experiences Mean for Adventure Travelers and Providers? An Industry Report to the Gold Coast Adventure Travel Group.

Karl, M., Reintinger, C., & Schmude, J. (2015). Reject or select: Mapping destination choice. Annals of Tourism Research, 54, 48-64. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2015.06.003 [ Links ]

Kim, J.-H. (2010). Determining the factors affecting the memorable nature of travel experiences. Journal of Travel & Tourism Marketing, 27(8), 780-796. http://doi.org/10.1080/10548408.2010.526897 [ Links ]

Kim, J.-H. (2014). The antecedents of memorable tourism experiences: The development of a scale to measure the destination attributes associated with memorable experiences. Tourism Management, 44, 34-45. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2014.02.007 [ Links ]

Kim, J.-H., & Ritchie, J. R. B. (2014). Cross-cultural validation of a memorable tourism experience scale (MTES). Journal of Travel Research, 53(3), 323-335. http://doi.org/10.1177/0047287513496468 [ Links ]

Kim, J. H. (2012). Development of a scale to measure memorable tourism experiences. European Journal of Tourism Research, 3(2), 123- 126. http://doi.org/10.1177/0047287510385467 [ Links ]

Kim, J., Ritchie, J. R. B., & McCormick, B. (2012). Development of a scale to measure memorable tourism experiences. Journal of Travel Research, 51(1), 12-25. http://doi.org/10.1177/0047287510385467 [ Links ]

Kline, R. B. (2011). Principles and practice of structural equation modeling. New York: The Guilford Press. [ Links ]

Knobloch, U., Robertson, K., & Aitken, R. (2016). Experience, emotion, and eudaimonia: A consideration of tourist experiences and well-being. Journal of Travel Research, 1-12. http://doi.org/10.1177/0047287516650937 [ Links ]

Komppula, R., Ilves, R., & Airey, D. (2016). Social holidays as a tourist experience in Finland. Tourism Management, 52, 521-532. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2015.07.016 [ Links ]

Lee, Y. (2015). Creating memorable experiences in a reuse heritage site.Annals of Tourism Research, 55, 155-170. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2015.09.009 [ Links ]

Manthiou, A., Kang, J., Chiang, L., & Tang, L. (Rebecca). (2016). Investigating the effects of memorable experiences: An extended model of script theory. Journal of Travel & Tourism Marketing, 33(3), 362-379. http://doi.org/10.1080/10548408.2015.1064055

Marôco, J. (2014). Análise de Equações Estruturais: Fundamentos Teóricos, Software & Aplicações. Pêro Ribeiro: CAFILESA. [ Links ]

Malhotra, N. K. (2006). Pesquisa de Marketing: Uma Orientação Aplicada. Porto Alegre: Bookman. [ Links ]

Matos, N. M. S. (2014). The impacts of tourism in the destination image. A marketing perspective. PhD Thesis, University of Algarve. [ Links ]

Matteucci, X. & Filep, S. (2015). Eudaimonic tourist experiences: The case of flamenco. Leisure Studies, 4367(October), 1-14. http://doi.org/10.1080/02614367.2015.1085590 [ Links ]

Morgan, M. (2010). The experience economy: 10 years on: Where next for experience management? In M. Morgan, P. Lugosi, & J. R. Brent Ritchie (Orgs.), The Tourism and Leisure Experience (pp. 63-77). Bristol: Channel View Publications. [ Links ]

Oh, H., Fiore, a. M., & Jeoung, M. (2007). Measuring experience economy concepts: Tourism applications. Journal of Travel Research, 46(2), 119-132. http://doi.org/10.1177/0047287507304039 [ Links ]

Pearce, D. G. (2014). Toward an integrative conceptual framework of destinations. Journal of Travel Research, 53(2), 141-153. http://doi.org/10.1177/0047287513491334 [ Links ]

Pezzi, E. & Vianna, S. L. G. (2015). A Experiência Turística e o Turismo de Experiência : um estudo sobre as dimensões da experiência memorável. Turismo em Análise, 26(1), 165-187. [ Links ]

Pine, B. J. P. & Gilmore, J. H. (2011). The experience economy. Boston: Harvard Business Review Press. [ Links ]

Quinlan-Cutler, S. & Carmichael, B. (2010). The dimensions of customer experience. In B. Morgan, M.; Lugosi, P., Ritchie (Org.), The tourism in leisure experience: Consumer and managerial perspectives. (pp. 3-26). Bristol: Aspects of Tourism. Recuperado de http://books.google.com.br/books/about/The_Tourism_and_Leisure_Experience.html?id=52ReGta3HDIC&pgis=1 [ Links ]

Schmitt, B. (2000). O modelo das experiências. HSM Management, 4(23). [ Links ]

Sirgy, M. J. (2012). The psychology of quality of life: Hedonic well-being, life satisfaction, and eudaimonia. New York: Springer. [ Links ]

Song, H. J., Lee, C.-K., Park, J. A., Hwang, Y. H., & Reisinger, Y. (2015). The influence of tourist Experience on perceived value and satisfaction with temple stays: The experience economy theory. Journal of Travel & Tourism Marketing, 32(4), 401-415. http://doi.org/10.1080/10548408.2014.898606 [ Links ]

Tsai, C. S. (2016). Memorable tourist experiences and place attachment when consuming local food. International Journal of Tourism Research, 548(January), 536-548. http://doi.org/10.1002/jtr [ Links ]

Tung, V. W. S., Lin, P., Qiu Zhang, H., & Zhao, A. (2016). A framework of memory management and tourism experiences. Journal of Travel & Tourism Marketing, 00(00), 1-14. http://doi.org/10.1080/10548408.2016.1260521 [ Links ]

Tung, V. W. S. & Ritchie, J. R. B. (2011a). Exploring the essence of memorable tourism experiences. Annals of Tourism Research, 38(4), 1367-1386.

Tung, V. W. S. & Ritchie, J. R. B. (2011b). Investigating the memorable experiences of the senior travel market: An examination of the reminiscence bump. Journal of Travel & Tourism Marketing, 28 (March 2015), 331-343. http://doi.org/10.1080/10548408.2011.563168

Tussyadiah, I. P. & Fesenmaier, D. R. (2009). Mediating tourist experiences. Access to places via shared videos. Annals of Tourism Research, 36(1), 24-40. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2008.10.001 [ Links ]

Walls, A. R., Okumus, F., Wang, Y. R., & Kwun, D. J. W. (2011). An epistemological view of consumer experiences. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 30(1), 10-21. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2010.03.008 [ Links ]

Walls, A. R. (2013). A cross-sectional examination of hotel consumer experience and relative effects on consumer values. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 32(1), 179-192.http://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2012.04.009 [ Links ]

Received: 15.05.2018

Revisions required: 28.07.2018

Accepted: 16.10.2018