Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Acessos

Acessos

Links relacionados

-

Similares em

SciELO

Similares em

SciELO

Compartilhar

Tourism & Management Studies

versão impressa ISSN 2182-8458versão On-line ISSN 2182-8466

TMStudies vol.13 no.1 Faro mar. 2017

TOURISM - SCIENTIFIC PAPERS

Liminality and the possibilities for sex and romance at an international bike meeting: a structural modeling approach

Liminaridade e as possibilidades de encontros sexuais e românticos numa concentração internacional de motos: uma abordagem de modelação estrutural

Milene Lança*, João Filipe Marques**, Patrícia Pinto***

*University of Algarve - Faculty of Economics and CIEO, Campus de Gambelas, 8005-139 Faro, Portugal, mglanca@ualg.pt

**University of Algarve - Faculty of Economics and CIEO, Campus de Gambelas, 8005-139 Faro, Portugal, jfmarq@ualg.pt

***University of Algarve - Faculty of Economics and CIEO, Campus de Gambelas, 8005-139 Faro, Portugal, pvalle@ualg.pt

ABSTRACT

Sex and romance are part of the everyday life and the tourism experiences. Tourism is a liminal space-time which enables liminoid experiences such as a greater willingness for romance and sex, which can be the main motivators for travelling or an incidental activity, although possibly at a higher intensity. This research falls over an event where the festive environment combined to the liminoid states may contribute to enhance the availability for romance and sex. This correlation was tested using structural equation modeling applied to data collected in a sample of 449 individuals at Faro International Bike Meeting. The results suggest that bikers are motivated by the expectations of having sex and getting involved in a romance. The meeting environment influences the liminoid experiences which, in turn, activate sexual and romantic pleasures. Bikers are satisfied and intend to return, proving that a new market segment is rising up in the Algarve.

Keywords: Faro international bike meeting, liminoid experiences, romance, sex, structural equation modeling with latent variables.

RESUMO

O sexo e o romance fazem parte do quotidiano e das experiências turísticas. O turismo constitui um espaço-tempo liminar que possibilita experiências liminóides, tais como uma maior disponibilidade para o romance e o sexo. Estes podem ser os principais motivadores da viagem ou atividades acidentais, ainda que com maior intensidade durante a viagem turística. Esta investigação retrata um evento onde o ambiente festivo, combinado com os estados liminóides, pode contribuir para aumentar a actividade sexual ou romântica. Esta correlação foi testada através da modelação de equações estruturais, aplicada a 449 questionários recolhidos durante a Concentração Motard de Faro. Os resultados mostram que os motards vêm motivados pela expectativa do envolvimento sexual ou romântico. O ambiente vivido influencia as experiências liminóides que, por sua vez, atuam sobre os prazeres sexuais e românticos. Os motards estão satisfeitos e pretendem regressar, demonstrando que um novo segmento de mercado está a crescer no Algarve.

Palavras-chave: Concentração motard de Faro, experiências liminóides, romance, sexo, modelação de equações estruturais com variáveis latentes.

1. Introduction

Tourist trips are increasingly part of the imagination of individuals and being sex an integral part of life, it is natural that people engage in sexual activities also when traveling. Sexual behaviour does not stay at home, goes as well on vacation (Larsen, 2008). However, most of the studies on the relationship between sex, romance and tourism has been conducted within the context of the “sex tourism” paradigm. The analysis focus of the majority of these studies has been sex as the main driver to choose a destination, having the established relationships almost always a commercial or even an exploitation character (Bauer & McKercher, 2003; Carr & Poria, 2010, Ryan & Hall, 2001; Ryan & Kinder, 1996; Trauer & Ryan, 2005).

The majority of the literature on tourism and sex tends to focus on the unequal and exploitation nature of the encounters between tourists and their sexual partners (Kempadoo, 1999; Kibicho, 2009). Specifically, literature concerns trafficking in women and children for prostitution, the exploitation of sex workers, the sex crimes, etc. In fact, many activities relating sex and tourism have negative, traumatic or exploitation characteristics, however the use of prostitution or other forms of commercial sex represent only a small part of the sexual activity that unfolds in tourism context. Nevertheless, the relationship between sex and tourism does not exhaust in its dark side. When one thinks in overall romantic, erotic or sexual encounters that take place in a tourism context, many of them, if not even the large part, are positive and gratifying for both intervenients. As Selänniemi puts it,

even though sex tourism and its most repulsive form, child sex tourism, often steals the scene when tourism and sex are discussed, one must keep in mind that the transitions tourists go through on holidays most often lead to positive results (both personally and morally), (2003: p.28).

Concerning romance, some authors have been stressing that when women travel to destinations in developing countries where sex and romance with local men are the main attractions, they are designated as “romance tourists”, while men travelling to those countries for the same purposes are designated as “sex tourists” (Bauer, 2014; Jeffreys, 2003; Omondi & Ryan, 2017; Pruitt & LaFont, 1995). However, another group of writers consider that women’s behaviour should be included within the category “sex tourism” (Bauer, 2014; Kempadoo, 1999). They prefer to use the expression “female sex tourism” to argue that women can be just as exploitative as men or even that there is nothing necessarily gendered about prostitution. Given that the focus of this paper is to test empirically the practices related to sexuality and romance in a specific tourism setting, using a special methodology for data analysis, we do not go into any great detail about this theoretical discussion. Thus, we use the concept of “romance” in Jackson’s point of view, who designated it as a “way to express feelings and emotions; where sexual «knowledge» connects with feelings and desires” (1993: p.46), and we do centre this research on a new approach, that of “sex and the sexual during tourism experiences” (Carr & Poria, 2010).

In Portugal, scientific research over the relationship between these three variables (romance, sex and tourism) almost does not exist. Knowledge produced prior respects to phenomena like prostitution, striptease or escort (Coelho, 2009; Oliveira, 2004; 2011). Sex, when related with tourism - even if that relation is very incipient - appears in the national literature suggesting “illegal” behaviours. This is the case of the research carried out by Ribeiro et al. (2007), which portraits the work of some prostitutes in the border between Portugal and Spain, being the majority of their clients of Spanish origin. Even so, one cannot properly speak about a relationship between sex and tourism, since in this case technically the clients are not tourists but visitors. One of the first studies made until now by Portuguese authors, which address the relationship between sex and tourism is the one of Ribeiro and Sacramento (2006), but the focus is also on the ‘sex tourism’ issue, in this case, in the northeast of Brazil.

The Algarve, in the South Portugal, is a recognized tourism destination and it is annually sought by thousands of national and foreign tourists. Although it is not considered a “sex tourism” destination, at least in the sense that the term has commonly assumed, it is stage for friends, couples or families on vacation, where sexuality plays certainly an important role. Further, the setting of Faro International Bike Meeting can be seen as a form of materializing the tourist experience in the Algarve.

Faro International Bike Meeting started in 1982 with about two hundred bikers (only four of them were Portuguese, except the staff members). Since then, this meeting was never been interrupted and it has been registered a significant increasing in the number of participants and a greater diversity of countries of origin. Currently, this meeting receives about 30,000 visitors on an annual basis and most of them are regular. It is the biggest bike meeting in Europe and one of the biggest in the world. Visitors demonstrate not only a huge passion for motorcycling, but also for the event attractions: concerts with international singers, striptease shows, bike shows and a wide range of products related to motorcycling. Considering that most of the participants are male, the cultural offer is based on the eroticism provided mainly by the female strippers and dancers. This meeting happens every year in mid-July, near the city of Faro, and it means four days of pure fun and adventure, where almost all is allowed.

The option for studying the visitors’ behaviour of this bike meeting results from an explicit necessity of breaking the stereotypes usually associated to bikers and to this sort of events. Generally, bikers are considered extravagant, crazy and wild, much due to their unique ethos or set of common values: the search for personal freedom, pleasure and flow (Schouten & McAlexander, 1995). In the same sense, they are seen as excessive alcohol consumers, dangerous riders and the embodiment of machismo (Chen & Chen, 2011; Schouten & McAlexander, 1995). These stereotypes are clearly visible, for instance, at Walt Becker’s movie “Wild Hogs” (2007).

Thus, in an apparently unruly and eroticized environment, will the bikers adopt behaviours that lead to romantic or sexual encounters? In which ways this type of tourism provides liminoid experiences? And will liminoid experiences be directly related, in one way, with the availability for sexual encounters and, in other way, with the satisfaction and the intention to return?

The aim of this paper is to test empirically a proposed model using structural equation modeling with latent variables, in order to better understand, on the one hand, the relationship between tourism and liminoid experiences and the influence of these in the availability for sex and romance, and on the other hand, the influence of sexual and romantic activities in satisfaction and intention to return. Therefore, through the analysis of the answers of Faro International Bike Meeting’ visitors to a questionnaire, we examined the relationships between the following constructs: environment, liminoid experiences, sex and romance, satisfaction and intention to return.

2. Literature review

Tourism is one of the social phenomena that characterizes modern societies and it is linked with the contemporary need for place consumption (Urry, 1990). This means that, in the era of Globalization, free time arouses the conquest of places through travel opportunities. Therefore, tourist trips are possibilities of liberation, in the sense of physical and psychological transportation from the fastidious reality of the everyday life (Bauer & McKercher, 2003).

According to Urry (1990), tourism results precisely from a basic binary division between the ordinary/everyday and the extraordinary. In the same sense, Ryan and Hall (2001) warn for the liminal character of tourism experiences which stimulate the adoption of radically different behaviours from those of the everyday life. At the destination, tourists may exteriorize aspects of their self that are repressed by the social constraints in everyday situations. Thus, travelling provides anonymity and evasion from the social control, the duty and the obligations, meaning as well the freedom for fantasy, imagination and adventure. This expression of self is related with two aspects of the individual’s intimacy. First, in everyday life, intimacy is constantly “watched over”. This means that intimacy or, more specifically, the aspects related with love or sexual activities are restrained by the social morality and by the “double standard” that tightens sexuality (Giddens, 1992). Second, in tourism contexts the individual may feel free to act the way he/she wants, since he/she is away from the belonging society (Pritchard & Morgan, 2000). Tourism contexts seem to provide a greater availability and freedom to engage in sexual activities, either with the conventional partners or in casual encounters with strangers.

Although eroticism and sexuality are part of life, they are often seen as human activities during which individuals get away from everyday life. As controversial as it may sound, sex and sexuality are elements with decision power over the self-esteem and the well-being of the individuals because of its extraordinary character. Then, which will be the connection between sexuality and the need of place consumption through the tourism trips?

According to some scholars, sex and tourism have been inextricably linked since the earliest days of travel (Bauer & McKercher, 2003; Jordan & Aitchison, 2008; Ryan & Hall, 2001). For as long as people have been travelling they have been engaging in romantic and sexual encounters of various types. Moreover, tourism may be viewed as sexualised - sex and tourism are truly connected and sex is an accepted part of tourism. Ryan and Hall (2001) propose that the linkage between sex and tourism is viewed as a natural continuum going from the non-commercial sexual encounters (such as holiday love stories and romances) to the commercial sexual encounters (such as prostitution, sex slavery and trafficking). Supporting their argument is the notion that “the commodification of sexuality is wider than just individuals. It also has to be seen in relation to places” (Ryan & Hall, 2001: p.148). Sexuality, therefore, cannot be understood without the spaces and places through which it is constituted and practised, as sexuality manifests itself through relations that are specific to particular spaces (Johnston & Longhurst, 2010). In the broadest sense, both sexual activity and tourism are forms of liberation in a particular space, allowing individuals escape from the constraints of a perceived mundane existence.

The relationship between sex and tourism can also be explained by the liminal nature of tourism (Andrews & Les Roberts, 2012; Bauer & McKercher, 2003; Ryan & Hall, 2001; Selänniemi, 2003). The sociological reflection about tourism is relatively unanimous in the use of the concept of liminality, though much of the tourism literature uses preferably the Turner’s concept of “liminal states”. In Turner’s lexicon, liminal refers to the transition stage of rites of passage and in the broadest sense, liminality refers to “any condition outside or on the peripheries of everyday life” (Turner, 1974: p.47). According to the author, however, liminality implies a kind of ritual process. The obligatory nature may be its essential attribute, lacking the voluntary aspect of ludic phenomena. In this sense, Turner (1974) suggests that in Western industrial societies, liminality have declined in importance as voluntary play has gained ascendency over obligatory rituals. So, Turner has coined the term liminoid to describe those activities that have liminal attributes but lack ritual associations. In contrast to liminality,

liminoid experiences are generally emphasized in societies with organic rather than mechanic solidarity; they are generally associated with leisure activities rather than calendrical rites; and they generally center upon activities that involve individual participation and idiosyncratic symbolism rather than upon activities that involve collective participation and collectively held meanings (Lett, 1983: p.45).

Tourism, as a liminoid period, provides a totally different space-time from that of production and work. Also Graburn (1977) regards tourism as one of “those structurally-necessary, ritualized breaks in routine that define and relieve the ordinary” (Graburn, 1977: p.19). Thus, traveling can provide behaviours of transgression or, at least, opportunities for people to do things that they would not normally do at home. The vacation trip constitutes a space-time in which it seems possible to realize all the fantasies and wishes that are denied to the social actors during their everyday life (Lett, 1983; Ryan & Kinder, 1996). The liminal nature of the vacation trip and of the tourism activities pass effectively by the transition in terms of place and time - tourists are doubly “out of time and out of place” (Wagner, 1977) - by the detachment from the worries of work, by the suspension of the social control, by the unusual consumption of food, alcohol or even drugs (Thorpe, 2012), by the “carnivalization” (Diken & Laustsen, 2004) and “staging” of these practices. All of these aspects, if not propitiate at least allow a certain level of “depersonalization”, of transgression and excess (Jaimangal-Jones, Pritchard & Morgan, 2010) that may provide increased opportunities for seduction and sex. As Selänniemi wrote,

Understanding tourism from this perspective, as a transition/transgression of both personal and social boundaries, which on the one hand liberates the tourist from certain norms and on the other hand accentuates the awareness of senses, may help us in understanding the multifaceted and complicated relation between tourism, romance and sex (2003: p.27).

If people participate in sexual activities at home, then certainly one must expect them to participate in sex when they travel (Bauer & McKercher, 2003; Larsen, 2008). Moreover, sexual encounters during tourism are not necessarily associated to prostitution or escort, as stated by Ryan and Hall (2001), although these are the most studied. The term liminoid may be used likewise in the analysis and explanation of the non-commercial sexual activities. Romances lived by those who travel with the purpose of developing a vacation relationship or by couples who want to invest in their relationship - may also occur (Ryan & Hall, 2001; Ryan & Kinder, 1996).

Further, romance and sex may be the main motivators for travel, but even when they are not - when sexual or romantic relationships represent an incidental aspect of the trip - it is certain that they enhance the relationship between the tourist and the place (Jordan & Aitchison, 2008) and consequently, their place attachment (He, 2013). Place attachment, linked to satisfaction, potentially explains repeat visitation. The more “connected” the tourists are to the destination, bigger will be their probabilities of return, as well as of giving a positive message to family and friends. Wu (2016) also argues that when tourists visit a place they develop emotional links with it, and this is important in understanding their behaviour. Accordingly, place attachment and the sexualised portrayal of people and places have been encouraged by the destinations and the tour operators which are engaged in selling a particular place (He, 2013; Jordan & Aitchison, 2008). The economic benefits for the host regions and countries are evident as well as the importance to better know this market segment.

These are the main reasons that underline the will to understand pleasure and emotions during vacation trips, namely the way individuals live and perform their sexuality in destinations such as the Algarve. The tourism experience in the Algarve is materialized, in this case, at Faro International Bike Meeting. The subsequent data analysis takes into account the answers given to a questionnaire by the bikers who attended this event in 2010.

3. Research model and hypotheses

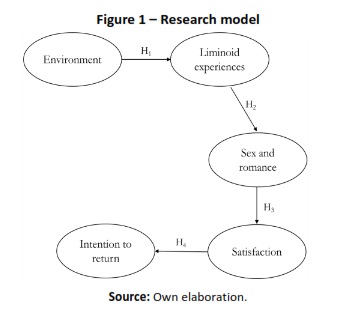

Based on the literature review and considering the unique context of this study, in other words, a liminal space-time par excellence (Lett, 1983; Ryan & Kinder, 1996) - the proposed research model is the following (Figure 1):

First, the model intends to analyse the relationship between the environment at the Bike Meeting and the liminoid experiences of the participants, suggesting that they are positively correlated. Second, the model evaluates the relationship between the liminoid experiences lived during the event and the availability for sex and romance, suggesting that the excesses and the transgressive behaviours influence the availability for sexual or romantic activities. Third, it intends to understand the relationship between the availability for sex and romance and the individuals’ satisfaction, suggesting that it has a positive effect on tourists’ satisfaction. Finally, in fourth place, it seeks to realize the relationship between tourists’ satisfaction and their intention to return, suggesting that the satisfaction has a positive effect on the intention to return.

There are several theoretical and empirical studies on the relationships between the environment, liminality, sexuality, satisfaction and loyalty to the destination (Andrews & Les Roberts, 2012; Bauer & McKercher, 2003; Carr & Poria, 2010; Herold, Garcia & DeMoya, 2001; McKercher, Denizci-Guillet & Ng, 2012; Oppermann, 1999; Ryan & Hall, 2001; Trauer & Ryan, 2005; Weichselbaumer, 2012; among others). However, none of them offers a simultaneous relationship between all of these constructs. Some scholars, for instance, (Andrews & Les Roberts, 2012; Bauer & McKercher, 2003; Ryan & Hall, 2001) argue that the environment at the destination or, in other words, the festive and relaxing atmosphere, enhances liminoid experiences, because the true nature of tourism as a liminoid period is to represent a rupture in the everyday life. Following this line, is presented the first hypothesis of this research: H1 - Environment has a positive effect on the liminoid experiences.

Other authors (Carr & Poria, 2010; Lett, 1983; Selänniemi, 2003; Thorpe, 2012) claim that liminality - as a transition stage of everyday roles and responsibilities for new experiences that go beyond the norms - which in turn enables liminoid states, is inwardly related with the availability for sex and romance in tourism context. In this sense, the second hypothesis is presented: H2- Liminoid experiences have a positive effect on the availability for romance and sex.

The engagement in romantic or sexual activities thus contributes to the tourists’ satisfaction: with the vacation trip, with the destination, with themselves (Bauer & McKercher, 2003; Oppermann, 1999; Weichselbaumer, 2012). On this basis, it is proposed the third hypothesis of this study: H3 - The availability for sex and romance has a positive effect on satisfaction.

Finally, the literature suggests that high levels of satisfaction lead to high levels of loyalty, so it is possible to say that satisfaction has a direct impact over the intention to return (McKercher, Denizci-Guillet & Ng, 2012; Trauer & Ryan, 2005). This study is no exception, so it is presented the fourth hypothesis of this research: H4 - Satisfaction has a positive effect on the intention to return.

4. Methodology

The findings presented here are based on data collected through a questionnaire. The questionnaire was designed with 26 open and closed questions derived from the literature about sexuality and tourism (Bauer & McKercher, 2003; Herold, Garcia & DeMoya, 2001; Ryan & Hall, 2001; Ryan & Kinder, 1996; Giddens, 1992; among others). It was selected a convenience sample, calculated for a confidence level of 95.0% and a maximum error margin of 4.5%, based on 30,000 annual visitors. From the 470 questionnaires collected during the 29th Faro International Bike Meeting, in 2010, 449 were validated by presenting non-response rates below 10.0%.

To ensure confidentiality, the names of participants were not requested and it was assured that their responses would remain completely confidential and anonymous, and would only be used for academic purposes. Participation in this study was also voluntary. The questionnaire was self-administered in order to guarantee the respondents’ freedom of expression, as well as the absence of the researcher’s influence. According to Ghiglione and Matalon (1978) the self-administered questionnaire is also applied when the questions are likely to cause some embarrassment, as it is the case of sexuality. The specificity of the event also determined this choice: people are constantly moving around and the noise of the concerts and motorbikes is also high, preventing to conduct in loco interviews. This is why the quantitative approach was elected instead of the qualitative one.

The variables in this study are of ordinal categorical type, following the recommendations of Chin (1998), Fornell and Larcker (1981) and Gefen and Straub (2005). A Likert scale of five points was used (scale of importance: 1 - not important; 2 - somewhat important; 3 - moderately important; 4 - very important; 5 - extremely important | scale of agreement: 1 - strongly disagree; 2 - disagree; 3 - neither agree nor disagree; 4 - agree; 5 - strongly agree), except for the latent variable ‘intention to return’ (1 - no; 2 - maybe; 3 - yes). The reduced dimension of the questionnaire, considering the specificity of the event, did not allow gathering other useful indicators. Even so, the adopted procedures are guarantee of the validity/reliability as well as of the fulfilment of the main objective of this study.

Partial Least Squares (PLS) was chosen to conduct the data analyses. PLS is a non-parametric strand of Structural Equation Modeling (SEM), and it aims to examine the significance of the relationships between research constructs and the predictive power of the dependent variables (Chin, 1998). Thus, PLS is suitable for predictive applications and theory building. PLS also does not place a very high requirement of normal distribution on the source data (Chin, 1998; Gefen & Straub, 2005) and has the ability to handle a relatively small sample size (Chin, 1998). SmartPLS 2.0 was specifically used in this study.

5. Data analysis and results

5.1 Sample characteristics

Faro International Bike Meeting is, by its nature, a homosocial event. Like the majority of the leisure sports involving risk and physical effort, motorcycling is also typified as an activity of the male-domain. It is deeply rooted in a subculture that has traditionally promoted the image of the "macho", emphasizing at the same time the power of masculinity - particularly that of hegemonic masculinity (Bird, 1996) - and the sexual subservience of women (Roster, 2007; Schouten & McAlexander, 1995). Even so and like other studies suggest, the female emancipation has been bringing more women to the motorcycling (Roster, 2007), contributing to reduce gender inequalities in this type of sport. These results are not an exception: in fact, the great majority of Faro International Bike Meeting’ participants are male (67.0%), although many women already attend the event (33.0%). The participants’ age ranges from 18 to 76 years old, and the average age is 35. They are Portuguese (52.1%), Spanish (22.0%) or British (18.0%), the majority is married or is living together (56.8%), but others are single (30.7%). Their education level lies on the high school (49.7%) or the university level (37.9%) and they are employed (82.4%). They arrive into the Algarve by motorcycle (72.4%), in the companion of friends (44.8%), spouse/conventional partner (27.4%), or even alone (10.0%). Most of them stay at the Bike Meeting camping (79.5%) for about five nights, reason why they are designated as tourists.

5.2 Measurement model

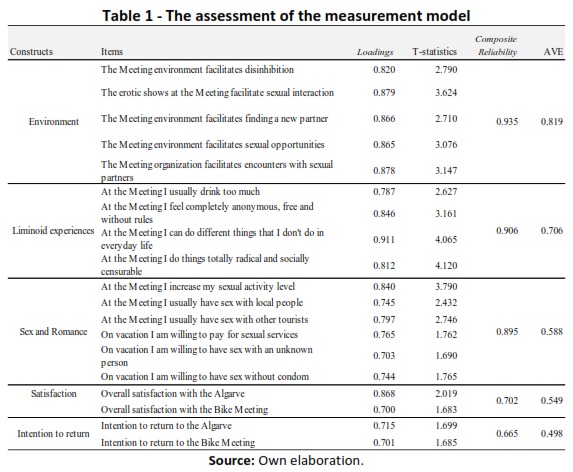

To assess the measurement model, we analysed reliability, convergent validity and discriminant validity, following the guidelines of Fornell and Larcker (1981), Gefen and Straub (2005) and Hutchinson et al. (2009).

In PLS, the individual reliability of each item is evaluated by the loadings’ magnitude (or simple correlations) of the measures with their constructs. The rule accepted by most researchers is that one should retain all of the items with loadings above the cutoff of 0.70 (Chin, 1998). In our model, loadings range from 0,700 e 0,911. In order to assess the quality of the measurement model, some authors (Fornell & Larcker, 1981; Hutchinson et al., 2009) propose a composite measure that takes into account the weight of each item in the respective construct and that corresponds to a measure of overall correlation between a construct and its indicator. In this case, composite reliabilities in our measurement model range from 0.665 to 0.935, above the recommended cutoff of 0.60 (Henseler et al., 2009).

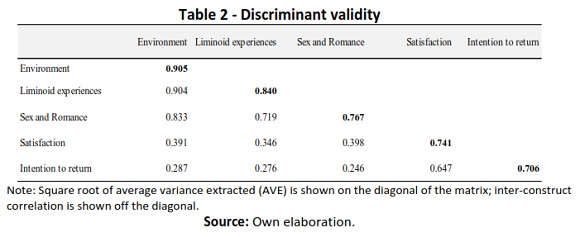

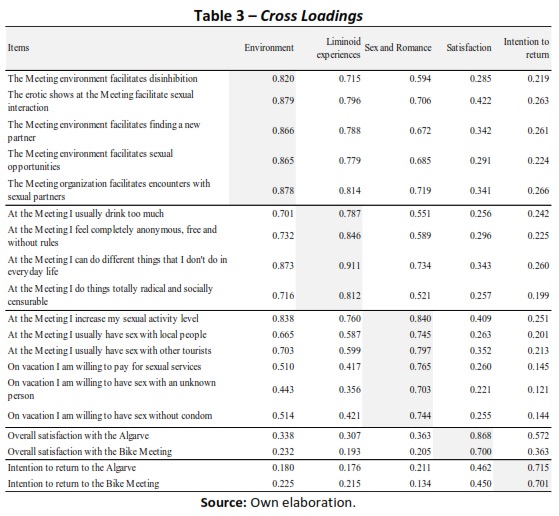

Convergent validity is given by the weight of each item (loadings) in the construct and the corresponding t-bootstrap. As mentioned above, the loadings ranged from 0.700 to 0.911 (p <0.05). Another measure of convergent validity is given by the Average Variance Extracted (AVE), that is, the variance shared between indicators and the construct, which should be higher than 0.50 (Bagozzi & Yi, 1988). In the case, all constructs fulfill this requirement with the exception of ‘Intention to return’ that, however, is very close to the threshold 0.50. Discriminant validity was assessed by comparing the AVE of each individual construct with shared variances between this individual construct and all the other constructs (Fornell & Larcker, 1981). For each construct, this aspect was observed by comparing the AVE of each latent variable and the squared correlations between this and the remaining latent variables. Other measure of discriminant validity is the observation of the cross-loadings, i.e., the loadings of each indicator in the other latent variables. Higher AVE of the individual construct than shared variances, on one hand, and cross loadings higher on the corresponding latent variables than on the remaining, on the other hand, suggests discriminant validity. Comparing all the correlations and square roots of AVEs shown on the diagonal, the results indicated adequate discriminant validity. The same applies to the cross-loadings. Tables 1, 2 and 3 show all the requirements for convergent validity and discriminant validity.

5.3. Structural model

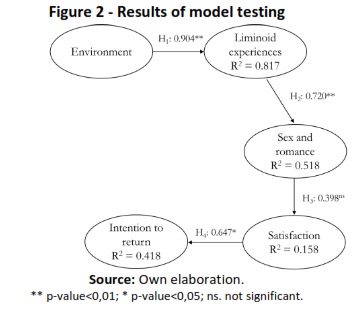

To test the proposed hypotheses, the structural model was fitted using the full sample. Assessment of the structural model involves estimating the path coefficients and the R2 values for each construct. Path coefficients indicate the strengths of the relationships between the constructs, while R2 values measure the predictive power of the structural model and indicate the amount of variance of latent dependent variables that is explained by the exogenous variables (Hutchinson et al., 2009). Through estimation via PLS, path coefficients were calculated for the hypotheses and the R2 values for the endogenous constructs. The results are shown in Figure 2.

As indicated by path coefficients and the associated significance level, only the influence of the availability for sex and romance on satisfaction is not significant at the 0.05 level (β = 0.398, t = 1.173, p >0.05), suggesting the rejection of H3.

However, the analysis of the remaining path coefficients reveals statistically significant relationships between the constructs. The significant path coefficient (β = 0.904, t = 6.551, p <0.01) indicates that the environment has a positive effect on the liminoid experiences during the event, supporting H1. Liminoid experiences also have a positive effect on the availability for sex and romance (β = 0.720, t = 3.133, p <0.01), supporting H2. Finally, the model shows that satisfaction has a positive effect on the intention to return (β = 0.647, t = 1.687, p <0.05), supporting H4.

As shown in Figure 2, the proposed model has a reasonable predictive power. It is the construct 'liminoid experiences' which has a greater predictive power (R2 = 0.817) indicating that the model explains 81.7% of the variance in this construct. The latent variables 'sex and romance', 'satisfaction' and 'intention to return’ have lower levels of R2 (51.8%, 15.8% and 41.8%, respectively), thus anticipating the possibility to improve the model, including other latent variables such as the expectations, the motivations for travelling and the psychographic profile of the respondents. Still, it is noted that the variance explained by the constructs 'sex and romance' (around 52%) and 'intention to return' (around 42%), confirms the importance suggested by the literature, of sex and romance in the tourism context (Jordan & Aitchison, 2008), and the role they play in tourists’ attachment (He, 2013).

6. Discussion and conclusions

This study tests a structural equation model with latent variables applied to the relationships between environment, liminoid experiences, sex and romance, satisfaction and intention to return. The aim of the study is to understand the relationships between these variables and in which way they manifest in the behaviour of bikers attending Faro International Bike Meeting. To this end, 449 visitors were inquired at the 29th Faro International Bike Meeting, and the main results are presented below.

In first place, one must say that motorcycling is a homosocial practice. In other words, it is an activity of the male-domain. This assumption is supported by the data collected, taking into account that the great majority of Faro International Bike Meeting’ visitors are male (67.0%). The representativeness of women in this kind of sport is still minimal (33.0%) and many of them go to the meeting with their conventional partners (47.3%). This aspect is relevant in the way that sexual and romantic practices (measured through the items ‘at the Meeting I increase my sexual activity level’, ‘at the Meeting I usually have sex with local people’, ‘at the Meeting I usually have sex with other tourists’, ‘on vacation I am willing to pay for sexual services’, ‘on vacation I am willing to have sex with an unknown person’ and ‘on vacation I am willing to have sex without condom’) are barred to more than half of the male visitors, in other words, to those who go alone or with friends to the meeting. For them, the opportunity of finding “available” women (at least at the Bike Meeting enclosure) is virtually non-existent - only 3.4% of the single women were alone at the meeting and none of them confessed to have sex with locals or tourists. This means that sexual or romantic practices during the event mostly occur with the usual partners. It is, therefore, a (re)investment in the conventional relationships, more than the search or the concretization of occasional sexual relationships. According to Larsen, “home is part of tourists’ baggage and bodily performances” (2008: p.25) and, in this case, performing sexuality is a continuation of regular lives, although at a higher intensity.

In second place, the relationship between most of the constructs proposed in the model is statistically significant. It is the case of the relationship between the environment and liminoid experiences (β = 0.904, t = 6.551, p < 0.01), supporting H1 (environment has a positive effect on liminoid experiences), in accordance with Andrews and Les Roberts (2012), Bauer and McKercher (2003), and Ryan and Hall (2001). In fact, an atmosphere that facilitates disinhibition and that is characterized by a strong eroticism, invites to the excesses and to the transgressions of the social norms. The item ‘the erotic shows at the Meeting facilitate sexual interaction’ is the one that mostly contributes to the construct ‘environment’ (loading = 0.879), and the item ‘at the Meeting I can do different things that I don't do in everyday life’ is the one that has higher “weight” in the construct ‘liminoid experiences’ (loading = 0.911). Besides these, the focus goes to the items ‘at the Meeting I feel completely anonymous, free and without rules’, ‘at the Meeting I do things totally radical and socially censurable’ and ‘at the Meeting I usually drink too much’, which significantly contribute for the ‘liminoid experiences’ (loadings = 0.846, 0,812 and 0.787, respectively). This means that the environment at Faro International Bike Meeting undoubtedly authorizes transgression behaviours or, at least, behaviours susceptible of some critic in another social context, such as the consumption of alcohol and drugs, or a certain “carnivalization” (Diken & Laustsen, 2004).

In third place, the results of this study show that the liminoid experiences lived at the meeting have a positive effect on the availability for sex and romance (β = 0.720, t = 3.133, p < 0.01), supporting H2 in conformity with the literature (Andrews & Les Roberts, 2012; Bauer & McKercher, 2003; Carr & Poria, 2010; Lett, 1983; Ryan & Hall, 2001; Selänniemi, 2003; Thorpe, 2012). Indeed, it is easy to understand that the consumption of psychoactive substances combined to the loosening of social rules, may facilitate the search of new sexual partners or a major availability for (re)investment in the established relationships. Moreover, the items ‘at the Meeting I increase my sexual activity level’ and ‘at the Meeting I usually have sex with other tourists’ are those that more contribute for the construct ‘sex and romance’ (loadings = 0.840 and 0.797, respectively). Their importance is evidence that the availability for sexual and romantic activities concerns to conventional partners. Although some individuals manifest the willingness of getting involved with strangers, their sexual opportunities are compromised, at least at the Bike Meeting enclosure, where the number of lonely visitors is relatively small. So, the results suggest that bikers’ behaviours related to sexuality are not as promiscuous as one might initially think.

Despite of the strong erotic atmosphere, H3 (the availability for sex and romance has a positive effect on satisfaction) was not confirmed by the results (β = 0.398, t = 1.173, p < 0.05). The visitors’ satisfaction seems to be more associated to the event and the region, than to the romantic or sexual practices. In addition, the relatively low predictive power of the construct ‘satisfaction’ (R2 = 0.158) denotes the need of including more specific indicators to assess the participants’ satisfaction.

In a general way, bikers’ satisfaction with Faro International Bike Meeting and the Algarve is high (89.1% and 90.6%, respectively). Thus, according to the literature over this topic (Herold, Garcia & DeMoya, 2001; McKercher, Denizci-Guillet & Ng, 2012; Trauer & Ryan, 2005), the intention to return is also high, supporting H4 (satisfaction has a positive effect on the intention to return). The item that mostly contributes to the ‘intention to return’ is the ‘intention to return to the Algarve’ (loading = 0.715), showing some degree of uncertainty about returning to the Bike Meeting. First, because the Bike Meeting is scheduled and it may collide with individual availabilities; second, because the economic context of the country has been constraining family budgets, limiting the participation in this type of events (namely for the Portuguese bikers).

The results of this study contribute for the existing literature in several ways. On the one hand, it is a study about romance and sexual behaviours that relates environment, liminality, satisfaction and intention to return. It was proven the relationship between the most of these constructs. On the other hand, this study is about tourists with very specific characteristics: even if bikers come mainly motivated by the participation in Faro International Bike Meeting, many of them show availability and also the expectation of getting involved in sexual or romantic activities, either with the usual partners or occasional ones. Thus, the potential of sex and romance forms an important dimension to tourist experience and destination choice. They live liminoid experiences during the meeting, they are very satisfied with the Algarve and the Bike Meeting, showing as well a strong desire to return.

A new market segment has been growing up in the Algarve due to Faro International Bike Meeting. Because many extend their stay beyond the event, choosing to spend a short vacation in the region, the economic impacts are fairly significant. However, considering the informal feedback given by some members of Moto Clube Faro, the financial support from public entities has been declining over the years. The quality and the continuation of this event, which brings many benefits to the region (not only economic, but also social and cultural), may be concerned. For these reasons, the commitment of the public and private sectors, namely those which directly benefit from this kind of tourism, is extremely important, as well as a deeper knowledge of the bikers’ characteristics and behaviours. Ultimately, this study provides evidence that the Algarve may implement strategies on the basis of a comprehensive partnership approach. Partnership, including private and public sector collaboration is viewed as a prerequisite to bring about innovation and quality that is required to sustain the event in the medium to long term.

Despite the contribution of this study to the literature, it has some limitations. The dimension of the questionnaire is one of them and the context did not allow exploring more questions. It was imperative that the questionnaire was as short as possible to ensure good acceptance from the respondents. The peculiar nature of this event also prevented the inclusion of other important questions. To further determine the potential of the model, additional research is needed, such as monitoring the study throughout other editions of the event, as well as for instance, identifying differences according to gender or nationality.

REFERENCES

Andrews, H. & Les Roberts (Eds.) (2012). Liminal Landscapes: Travel, Experience and Spaces In-between. London: Routledge.

Bagozzi, R. & Yi, Y. (1988). On the Evaluation of Structural Equation Models. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 16, 74-94. [ Links ]

Bauer, I. (2014). Romance tourism or female sex tourism? Travel Medicine and Infectious Disease, 12, 20-28. [ Links ]

Bauer, T. & McKercher, B. (Eds.) (2003). Sex and Tourism: journeys of romance, love and lust. New York: The Haworth Hospitality Press.

Bird, S. (1996). Welcome to the men’s club: homosociality and the maintenance of hegemonic masculinity. Gender and Society, 10(2), 120-132. [ Links ]

Carr, N. & Poria, Y. (Eds.) (2010). Sex and the sexual during people’s leisure and tourism experiences. Newcastle: Cambridge Scholars Publishing.

Chen, C. & Chen, C. (2011). Speeding for fun? Exploring the speeding behavior of riders of heavy motorcycles using the theory of planned behavior and psychological flow theory. Accident Analysis and Prevention, 43, 983-990. [ Links ]

Chin, W. (1998). The partial least squares approach to structural equation modelling. In G. Marcoulides (Ed.), Modern Methods for Business Research (pp. 295-336). New Jersey: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers. [ Links ]

Coelho, B. (2009). Corpo Adentro: Prostitutas acompanhantes em processo de invenção de si. Lisbon: Difel. [ Links ]

Diken, B. & Laustsen, C. (2004). Sea, sun, sex and the discontents of pleasure. Tourist Studies, 4(2), 99-114. [ Links ]

Fornell, C. & Larcker, D. (1981). Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. Journal of Marketing Research, 18(1), 39-50. [ Links ]

Gefen, D. & Straub, D. (2005). A practical guide to factorial validity using PLS-graph: tutorial and annotated example. Communications of the Association for Information Systems, 16(5), 91-109. [ Links ]

Ghiglione, R. & Matalon, B. (1978). Les enquêtes sociologiques, théoriques et pratiques. Paris: Armand Colin. [ Links ]

Giddens, A. (1992). The Transformation of Intimacy: Sexuality, Love and Eroticism in Modern Societies. California: Stanford University Press.

Graburn, N. (1977). Tourism: The Sacred Journey. In V. Smith (Ed.), Hosts and Guests: The Anthropology of Tourism (pp. 17-31). Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press. [ Links ]

He, L. (2013). Assessing Visitors’ Place Attachment and Associated Intended Behaviours Related to Tourism Attractions. Master thesis in Business by Research (Hospitality and Tourism). Melbourne: College of Business, Victoria University. Retrieved September, 10, 2015 from http://vuir.vu.edu.au/ 24390/1/Li%20He.pdf.

Henseler, J., Ringle, C. & Sinkovics, R. (2009). The use of Partial Least Squares Path Modeling in international Marketing. Advances in International Marketing, 20, 277-319. [ Links ]

Herold, E., Garcia, R. & DeMoya, T. (2001). Female tourists and beach boys: romance or sex tourism? Annals of Tourism Research, 28(4), 978-997. [ Links ]

Hutchinson, J., Lai, F. & Wang, Y. (2009). Understanding the relationships of quality, value, equity, satisfaction and behavioral intentions among golf travelers. Tourism Management, 30(2), 298-308. [ Links ]

Jackson, S. (1993). Love and romance as objects of feminist knowledge. In M. Kenned, C. Lubelska & V. Walsh (Eds.), Making Connections: women’s studies, women’s movements, women’s lives (pp. 39-50). London: Taylor & Francis. [ Links ]

Jaimangal-Jones, D., Pritchard, A. & Morgan, N. (2010). Going the distance: locating journey, liminality and rites of passage in dance music experiences. Leisure Studies, 29(3), 253-268. [ Links ]

Jeffreys, S. (2003). Sex tourism: do women do it too? Leisure Studies, 22, 223-238. [ Links ]

Johnston, L. & Longhurst, R. (2010). Space, place, and sex: geographies of sexualities. New York: Rowman & Littlefield Publishing Group, Inc. [ Links ]

Jordan, F. & Aitchison, C. (2008). Tourism and the sexualisation of the gaze: solo female tourists’ experiences of gendered power, surveillance and embodiment. Leisure Studies, 27(3), 329-349. [ Links ]

Kempadoo, K. (Ed.) (1999). Sun, Sex, and Gold. Tourism and Sex Work in the Caribbean. USA: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, Inc. [ Links ]

Kibicho, W. (2009). Sex Tourism in Africa: Kenya’s Booming Industry. Surrey: Ashgate Publishing Limited. [ Links ]

Larsen, J. (2008). De-exoticizing tourist travel: everyday life and sociality on the move. Leisure Studies, 27(1), 21-34. [ Links ]

Lett, J. (1983) Ludic and liminoid aspects of charter yacht tourism in the Caribbean. Annals of Tourism Research, 10, 35-56. [ Links ]

McKercher, B., Denizci-Guillet, B. & Ng, E. (2012). Rethinking loyalty. Annals of Tourism Research, 39(2), 708-734. [ Links ]

Oliveira, A. (2011). Andar na Vida: Prostituição de Rua e Reacção Social. Coimbra: Edições Almedina. [ Links ]

Oliveira, A. (2004). As Vendedoras de Ilusões: Estudo Sobre Prostituição, Alterne e Striptease. Lisbon: Editorial Notícias. [ Links ]

Omondi, R. & Ryan, C. (2017). Sex tourism: romantic safaris, prayers and witchcraft at the Kenyan coast. Tourism Management, 58, 217-227. [ Links ]

Oppermann, M. (1999). Sex tourism. Annals of Tourism Research, 26(2), 251-266. [ Links ]

Pritchard, A. & Morgan, N. (2000). Privileging the male gaze: gendered tourism landscapes. Annals of Tourism Research, 27(4), 884-905. [ Links ]

Pruitt, D. & LaFont, S. (1995). For love and money: romance tourism in Jamaica. Annals of Tourism Research, 22(2), 422-440. [ Links ]

Ribeiro, F. & Sacramento, O. (2006). A ilusão da conquista: sexo, amor e interesse entre gringos e garotas em Natal. Cronos, 7(1). [ Links ]

Ribeiro, M., Silva, M., Schouten, J., Ribeiro, F. & Sacramento, O. (2007). Vidas na Raia: Prostituição feminina em regiões de fronteira. Porto: Edições Afrontamento. [ Links ]

Roster, C. (2007). “Girl Power” and Participation in Macho Recreation: The Case of Female Harley Riders. Leisure Sciences, 29(5), 443-461. [ Links ]

Ryan, C. & Hall, M. (2001). Sex Tourism: marginal people and liminalities. London: Routledge. [ Links ]

Ryan, C. & Kinder, R. (1996). Sex, tourism and sex tourism: fulfilling similar needs? Tourism Management, 17(7), 507-518. [ Links ]

Schouten, J. & McAlexander, J. (1995). Subcultures of consumption: an ethnography of the new bikers. Journal of Consumer Research, 22, 43-61. [ Links ]

Selänniemi, T. (2003). On holiday in the liminoid playground: place, time, and self in tourism. In T. Bauer & B. McKercher (Eds.), Sex and Tourism: journeys of romance, love and lust (pp. 19-31). New York: The Haworth Hospitality Press. [ Links ]

Thorpe, H. (2012). ‘Sex, drugs and snowboarding’: (il)legitimate definitions of taste and lifestyle in a physical youth culture. Leisure Studies, 31(1), 33-51. [ Links ]

Trauer, B. & Ryan, C. (2005). Destination image, romance and place experience - an application of intimacy theory in tourism. Tourism Management, 26(4), 481-491. [ Links ]

Turner, V. (1974). Dramas, Fields and Metaphors. New York: Cornell University Press. [ Links ]

Urry, J. (1990). The tourist gaze: Leisure and travel in contemporary societies. London: Sage. [ Links ]

Wagner, U. (1977). Out of time and place: mass tourism and charter trips. Ethnos: Journal of Anthropology, 42(1-2), 38-52. [ Links ]

Weichselbaumer, D. (2012). Sex, romance and the carnivalesque between female tourists and Caribbean men. Tourism Management, 33(5), 1220-1229. [ Links ]

Wu, C. (2016). Destination loyalty modeling of the global tourism. Journal of Business Research, 69, 2213-2219. [ Links ]

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to express their gratitude to all the bikers who collaborated in this study, to Moto Clube Faro and to the fieldwork team.

Received: 30 April 2016

Accepted: 16 December 2016