Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Indicators

-

Cited by SciELO

Cited by SciELO -

Access statistics

Access statistics

Related links

-

Similars in

SciELO

Similars in

SciELO

Share

Tourism & Management Studies

Print version ISSN 2182-8458

TMStudies vol.12 no.1 Faro Mar. 2016

https://doi.org/10.18089/tms.2016.12113

TOURISM: SCIENTIFIC PAPERS

Corporate social responsibility in tourism: The case of Zoomarine Algarve

Responsabilidade social no turismo: O caso do Zoomarine Algarve

Joaquim Pinto Contreiras1, Virgílio Miguel Machado2, Ana Patrícia Duarte3

1University of Algarve, School of Management, Hospitality and Tourism, Largo Engº Sárrea Prado, nº 21, 8501-859 Portimão, Portugal, Research Centre for Spatial and Organizational Dynamics (CIEO). E-mail: jcontrei@ualg.pt

2University of Algarve, School of Management, Hospitality and Tourism, Largo Engº Sárrea Prado, nº 21, 8501-859 Portimão, Portugal, Research Centre for Spatial and Organizational Dynamics (CIEO). E-mail: vrmachado@ualg.pt

3Instituto Universitário de Lisboa (ISCTE-IUL), Business Research Unit, (BRU-IUL), Avenue Forças Armadas, 1649-026 Lisbon, Portugal; Research Centre for Spatial and Organizational Dynamics (CIEO). E-mail: patricia.duarte@iscte.pt

ABSTRACT

This study had a threefold purpose. First, it sought to examine the opinion of three important stakeholders – employees, visitors and members of the local community – about the corporate social responsibility (CSR) practices of the theme park, Zoomarine Algarve. Second, this study evaluated the perceptions of the public regarding the impact of the companys activities on regional development and environmental awareness. Last, the study sought to understand if stakeholders opinions regarding this companys engagement in CSR practices are related to the impacts attributed to Zoomarine Algarves regular functions. The methodology comprised quantitative research based on a survey administered to convenience samples of the target groups (n = 405). The results reveal that stakeholders have an extremely positive view of the theme parks engagement in CSR practices and feel that it contributes significantly to regional development, as well as to raising the environmental awareness of visitors and local communities. The findings also show that perceptions of CSR engagement are positively related with perceived impacts.

Keywords: Corporate social responsibility, sustainability, tourism, theme park, stakeholders.

RESUMO

Este estudo teve um triplo propósito. Primeiro, examinar a opinião de três importantes partes interessadas – empregados, visitantes e membros da comunidade local – sobre as práticas de responsabilidade social empresarial (RSE) do Zoomarine Algarve. Segundo, avaliar as perceções destes públicos relativamente ao impacto das atividades desta empresa no desenvolvimento regional e ao nível da sensibilização ambiental. Terceiro, perceber se as opiniões das partes interessadas relativamente ao envolvimento da empresa em práticas de RSE estão relacionadas com os impactos que são atribuídos ao seu funcionamento. A metodologia envolveu uma pesquisa quantitativa baseada na aplicação de um inquérito a amostras de conveniência dos grupos-alvo (n total=405). Os resultados revelaram que as partes interessadas apresentam uma visão bastante positiva do envolvimento do parque temático em práticas de RSE e consideram que o mesmo contribui de forma importante para o desenvolvimento regional e para a sensibilização ambiental de visitantes e comunidade local. Os resultados revelaram também que as perceções de envolvimento em RSE estão positivamente associadas aos impactos percebidos.

Palavras-chave: Responsabilidade social empresarial, sustentabilidade, turismo, parque temático, partes interessadas.

1. Introduction

Corporate social responsibility (CSR) is not a new topic (Carroll & Shabana, 2010), but its importance in debates about tourism management has grown in recent years (Coles, Fenclova & Dinan, 2013; Holcomb, Okumus & Bilgiham, 2010). The importance of this topic was recognised by the World Tourism Organisation (WTO) almost 15 years ago, in the Global Code of Ethics for Tourism published in 1999, in which the obligations of major players were emphasised in terms of tourism development, sustainability and the safeguarding of the environment and natural resources.

In fact, the economic globalisation and free movement of capital, goods, services and people has required new ways of thinking and acting in terms of responsibility (Carroll & Shabana, 2010). Several calls for more responsible forms of tourism production and consumption have been issued (e.g. Goodwin & Francis, 2003; Spenceley, 2008), and research on CSR and tourism has increased over recent years. These studies have focused generally on public policy and sustainability strategies and on CSR in destinations and local communities (Cordeiro, Leite & Partidário, 2009; Figueira & Dias, 2011; Machado, 2010; Tao & Wall, 2009). Researchers have analysed and discussed CSR and sustainability issues in several tourism organisations, including restaurants (e.g. Gimenes, 2004; Kim & Kim, 2014; Moratelli & Barros, 2004; Pacheco & Martins, 2004), hotels (e.g. Contreiras, 2011; Ferraz, Schön & Gallardo-Vásquez, 2011; Kucukusta & Chan, 2013; Pazos, 2004; Youn, Hua, & Lee, 2015), air transport companies (e.g. Cowper-Smith & Grosbois, 2011; Valente & Souza, 2004), cruise companies (e.g. Bonilla-Priego, Font & Pacheco-Olivares, 2014; Font, Guix & Bonilla-Priego, 2016) and tourism press organisations (Falcetta, 2004).

A new addition to this body of research, the present study focused on CSR in a theme park company. Since theme parks attract a large number of visitors, their activity has a considerable effect on local economies (Holcomb et al., 2010) and is considered an important driver in tourism and hospitality (Milman, 2008). Theme parks have also other significant positive impacts on local communities, including impacts resulting from CSR practices (e.g. discretionary, community involvement, environment and diversity practices) (Holcomb et al., 2009; Martins & Costa, 2009). Nevertheless, the existent knowledge about CSR and sustainability activities in this specific type of tourism company remains scarce (Holcomb et al., 2010; Lyra & Souza, 2013, 2015; Martins & Costa, 2009). This is especially true in Portugal, where, to the best of our knowledge, only one study by Martins and Costa (2009) has analysed CSR in this type of company.

Therefore, this particular organisational context provides fertile ground for exploring CSR. The present study had a threefold purpose. First, it sought to examine the opinions of three important stakeholders – employees, visitors and members of the local community – about the CSR practices of Zoomarine Algarve (ZA), a well-known theme park located in the south of Portugal. A second objective was to evaluate the perceptions of the public regarding the impact of the companys activities on regional development (i.e. employability, tourism and the economy) and environmental awareness. Finally, a third goal was to understand if stakeholders opinions regarding this companys engagement in CSR practices were related to the impact they attributed to ZAs regular functions. By adopting a descriptive case study approach, the present study differentiates itself from previous research, not only by focusing its attention on a theme park company but, more importantly, by examining the opinions of three kinds of stakeholders simultaneously, a procedure that is still uncommon in tourism research (Coles et al., 2013).

This paper is organised in the following manner. The next section reviews the literature on CSR. The organisational context in which the case study took place is then presented. The methodology used for empirical proposes is described in the fourth section, followed by the presentation of results. The conclusions are presented and discussed in the last section, in which some of the studys limitations are also indicated and suggestions for future studies offered.

2. Literature review

Studies on CSR reflect a complex framework in which companies internalise societal, economic and environmental concerns in their policies, strategies and behaviours, as part of an on-going process of validation and justification of their existence to society (Araya, 2003; Toldo, 2004). CSR involves dimensions that go far beyond legal obligations in social and environmental issues, and compliance with the law is only the minimum prerequisite for meeting this responsibility (European Commission, 2001; UNCTAD, 2003, as cited in Figueira & Dias, 2011). CSR implies an on-going effort to act with sensitivity and to demonstrate a strong commitment to society, including meeting the publics expectations and development challenges (Figueira & Dias, 2011; Jesus & Batista, 2014). CSR also implies the constant surveillance of impacts on society, in order to maximise the creation of shared value for all stakeholders and society at large and the prevention and mitigation of possible negative impacts (European Commission, 2011). Stakeholders are any groups or individuals that can affect or be affected by a companys business operations (Freeman, 1984), such as employees, clients, suppliers and local communities.

The range of socially responsible practices that a company can implement is vast, including, for instance, practices seeking to reduce environmental impacts, improve occupational health and safety, invest in people management and development, support communities or ensure a firms economic sustainability (Carroll & Shabana, 2010; Dahlsrud, 2008; Duarte, Gomes & Neves, 2014; Neves & Bento, 2005). These practices have been included in different CSR models and dimensions (e.g. Carroll, 1979; Dahlsrud, 2008; Neves & Bento, 2005). An extensively adopted three-dimensional perspective on CSR distinguishes between economic, social and environmental dimensions, based on enduring principles of ecological prudence, social equity and economic efficiency (e.g. Li, 2005; Martinez, Pérez & Del Bosque, 2013; Panapaan, Linnanen, Karvonen, & Phan, 2003; WTO, 2004).

In the present study, a similar three-dimensional perspective was adopted, based on Duarte, Mouro and Nevess (2010) work. After assessing the social meaning of CSR for a sample of Portuguese respondents, the cited authors found that people can have three different conceptions of a socially responsible company. For some individuals, a socially responsible company is one that behaves in a community and ecologically friendly way (e.g. supports social or environmental causes). For others, CSR means companies carry out their business operations in an efficient and ethical manner (i.e. revealed ethical behaviour), and, for a third group of people, CSR is companies that adopt human resource management practices that promote the welfare of employees and their families (e.g. promote work-family balance).

Keeping in mind the multidimensional nature of the CSR construct, the first objective of this study was to examine the opinion of employees, visitors and members of the local community regarding the engagement of ZA in socially responsible practices towards employees, communities and the environment, as well as on an economic level. Accordingly, a triangular construction of the perceptions of three kinds of stakeholders (i.e. employees, visitors and the local community), in three dimensions of CSR (i.e. economic, employees and the environment and communities), was measured, parameterised and compared, in order to evaluate the image of ZA from an integrated perspective. In fact, CSR research is many times an exercise of alignment and detection of consensus or disagreements between stakeholders, assessing the consistency between external objectives and internal organisational incentives (Pavlovich, 2003). The perceptions of stakeholders regarding a companys engagement in socially responsible and sustainable practices can be a key element in the evaluation of that companys corporate social performance.

This analysis appears to be particular relevant in tourism organisations, for which image and reputation are a highly valued intangible asset. Nonetheless, as stated previously, the analysis of different stakeholders opinions at the same time is uncommon in tourism research (Coles et al., 2013). Lyra and Souzas (2013, 2015) study is an exception. The cited authors analysed the perceptions of five stakeholder groups (i.e. employees, visitors, managers, members of the local community and members of local government) of the Brazilian thematic park Beto Carrero World, using a survey and semi-structured interviews. The findings revealed that stakeholders felt that the theme park implemented practices pertaining to different CSR dimensions.

Theme parks provide entertainment and recreational services for immediate consumption, usually in a one-day tourism experience. At the same time, theme parks need to reconcile their activities consistently with the social, cultural and environmental context in which they operate, taking into account the constraints of efficiency inherent to for-profit organisations (Vera, Palomeque, Gómez & Clavé, 2011).

As suppliers of tourism services, theme parks should develop activities that respect the environment, cultural heritage and local communities. In turn, tourists need to adopt ethical and sustainable consumption patterns of tourism products. These obligations are legal provisions in Articles 20 c) and 23 d) of the law on public policy on tourism in Portugal (DL nº 191/2009 of 17 August). Moreover, ethical, responsible and sustainable behaviour should be part of any organisation, with a special focus on leadership and management roles (Figueira & Dias, 2011). Mobility patterns inside, and individual satisfaction with, theme parks require urban functions, collective services and infrastructures, such as energy, water, food, communications, waste collection and security, health, hygiene and cultural services. Therefore, theme parks – as a part of leisure infrastructure – face special problems in terms of CSR and sustainability for local communities, beyond the simple logic of a tourism product. These problems constitute a serious challenge to tourism management and underline the importance and relevance of research on CSR in theme parks.

As mentioned above, theme parks can have several types of impacts on local communities. Martins and Costa (2009) analysed the environmental, sociocultural and economic impacts of Portuguese theme parks. According to their analysis, theme parks can make positive contributions to environmental conservation, employability, local economies and the quality of life of specific social groups, but they also have negative effects such as the seasonality of touristic demand, road traffic and car accidents or the destruction of local heritage. Taking this into account, a second objective of the present study was to evaluate the perceptions of employees, visitors and members of the local community regarding the impact of ZAs activities on regional development (i.e. employability, tourism and the economy) and environmental awareness. A third goal of this study was to explore if stakeholders opinions regarding the selected companys engagement in CSR practices are related to the impact attributed to the companys regular functions. In the next section, a description of this theme park is presented.

2.1 The case study – Zoomarine Algarve

This paper discusses a descriptive case study focusing on the theme park ZA. This theme park was created in 1991, in Guia, a town in the south of Portugal. ZA is one of the best-known tourism offers of the Algarve region. Its mission is to promote knowledge and, in particular, environmental education regarding the preservation of marine fauna and life, in a fun and passionate way (ZA, 2015). Its premises currently comprise an area of ??more than 10 hectares, and the company has around 170 workers with permanent or fixed-term employment contracts. The park is opened from April to October and is visited by approximately half a million visitors per year, where they can enjoy diverse leisure, entertainment and environmental education activities. These are based on easy access to a world of marine fauna and fantasy, which stimulates unique sensations and emotions. The company has several objectives (ZA, 2015), notably:

• Education – providing unique experiences that create a link with nature and stimulate a passion to learn in order to make todays young people tomorrows knowledgeable adults

• Fun – carrying adults and children to a world of adventure and fantasy, waking smiles and dreams and giving new life to emotions

• Preservation – creating a deeper understanding, awareness and active participation in the conservation and preservation of life in the oceans, including marine species and habitats

• Knowledge – researching, building knowledge and sharing the secrets of life in the oceans; promoting and integrating knowledge and collaborating with scientific, national and international communities

• Development – creating and strengthening ties with the local community, valuing individuals and actively contributing to their economic and social development

Its mission and action plan indicate that this organisation is committed to sustainable development objectives and CSR, especially regarding park visitors, through offering learning services, strengthening ties with and roots in the local community, along with valuing individuals by providing knowledge, education and the preservation of living nature. However, a number of questions still remained. How do stakeholders perceive the engagement of ZA in CSR practices? Is there a consensus in perceptions or, on the contrary, marked differences between the way each group assesses the companys performance in CSR dimensions? What about the impact of the company on regional development and environmental awareness? Is there a relationship between perceived engagement in CSR practices and perceived impacts? These were the research questions that guided this study. The methodology implemented in the resulting study is described in the next section.

3. Methodology

3.1 Instrument

The methodology comprised a quantitative descriptive case study based on a survey administered to convenience samples of the target groups. The survey was developed by the research team based on the available literature and approved by ZA before being administered to the different stakeholders. Given the data collection procedure, the number of questions included in the survey was necessarily limited. The survey was divided into three sections.

In the first section, information regarding the perceived impact of the theme parks activities was collected. Participants were asked to indicate their level of agreement with five items about impacts on regional development (e.g. Zoomarine contributes to the development of tourism in the Algarve; a = 0.76) and two items about impacts on environmental awareness (e.g. Zoomarine promotes the environmental education of tourists and the local community; rho = 0.53). A five-point Likert type response scale was used (1 = totally disagree to 5 = totally agree).

In the second section, information regarding the perceived engagement of ZA in socially responsible practices was obtained. Participants were asked to indicate their level of agreement with 18 items adapted from the Perceived Corporate Social Responsibility Scale developed by Duarte (2011). These items measure the level of engagement in three dimensions of CSR: economic CSR – four items (e.g. Zoomarine strives to be one of the best organisations in its business sector; a = 0.70); CSR towards employees – six items (e.g. Zoomarine invests in the promotion of work-family balance; a = 0.80) and CSR towards the local community and the environment – eight items (e.g. Zoomarine supports sports events; a = 0.81). Again, a five-point Likert type response scale was used (1 = totally disagree to 5 = totally agree).

The third and final section included questions regarding sociodemographic characteristics of respondents, namely, gender, age and educational level. In addition, employees were asked to indicate tenure in the organisation, the type of employment contract and any management functions they had. Visitors were asked to indicate nationality, number of visits to ZA and any family or friends working for ZA. Members of the local community were asked to indicate their parish of residence, number of visits to ZA and any family or friends working for ZA.

3.2 Data collection procedure

The survey was administered in three phases. Employees were surveyed in November 2013, before the theme park closed for the season. All permanent employees (approximately 100) were invited to take part voluntarily in the study on the companys premises. Members of the local community were surveyed in January 2014. Three surrounding parishes were selected for this purpose: Algoz (23%), Guia (19%) and Armação de Pêra (58%). Participants were approached in public areas (e.g. streets, central squares and post offices) and invited to participate voluntarily in the study. Only individuals who knew or had heard of ZA were surveyed. Visitors were surveyed in May 2014, after the season opening of the theme park. Visitors were addressed on the ZA premises and invited to take part voluntarily in the survey. Given the habitually large influx of non-Portuguese visitors, Portuguese and English versions of the survey were made available.

All participants were informed that the survey was part of a research project on the opinions of employees, the regions residents and visitors – depending on the target group – about some aspects of the activities of ZA and its importance to the region. The anonymity and confidentiality of all responses were safeguarded. Given the sampling procedures, the subsamples are convenience samples, which limits the generalisation of results to the original sample populations.

3.3 Sample

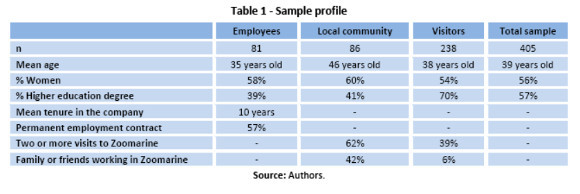

A total of 405 individuals were surveyed: 20% worked for ZA, 21% lived in the local community and 59% were visitors. Overall, participants were aged between 18 and 80 years old, with a mean age of 39 years (SD = 12 years). The sample was relatively balanced in terms of gender distribution (56% women). With regard to formal education, 57% of participants had at least some higher education, 32% had attended between 10 to 12 years of school and 11% had completed ninth grade or less.

Regarding the sub-sample of employees (n = 81), these were aged between 19 and 64 years old (M = 35 years; SD = 9 years), and 58% were women. Their formal education was as follows: 20% had completed the ninth grade or less, 41% had attended 10 to 12 years of school and 39% had a higher education degree. More than half of respondents (57%) had a permanent employment contract. The remaining had a fixed-term employment contract. Their tenure varied between 1 and 22 years, with a mean tenure of 10 years (SD = 6 years). Most participants performed duties without managerial responsibilities (75%).

Concerning the sub-sample of members of the local community (n = 86), the respondents lived in several villages of the region, in particular in the parishes of Silves (27%), Pera (22%) and Ferreiras (15%), which surround the area directly influenced by the theme park. Participants were aged between 22 and 80 years old (M = 46 years; SD = 13 years), and 60% were women. The residents education was as follows: 19% had completed ninth grade or less, 40% had attended between 10 and 12 years of school and 41% had a higher education degree. About a fifth of the respondents (19%) reported never having visited ZA, but the majority had visited it twice or more times (62%). One-fifth (20%) had visited it only once. It should be noted that 42% of respondents had a family member or friend working at ZA.

Concerning the sub-sample of visitors (n = 238), they were from different countries, mainly the United Kingdom (53%), Portugal (19%) and Ireland (14%). Other nationalities were less frequently represented. Visitors were aged between 18 and 75 years old (M = 38 years; SD = 12 years), and 54% were women. The visitors education was as follows: 5% had completed ninth grade or less, 25% had attended between 10 and 12 years of school and 70% had a higher education degree. Most visitors were visiting the ZA for the first time on the day they took the survey (61%). Only 6% of the participating visitors said they had a family member or friend working at ZA. Table 1 summarises the sociodemographic profile of the sample.

4. Results

Data were analysed using the IBM Statistical Package for the Social Sciences, version 20.0.

4.1 Engagement in CSR practices

The first objective of this study was to examine the perceptions that three stakeholder groups have of ZAs CSR practices. Accordingly, respondents were asked to indicate their opinion about this companys engagement in 18 practices in three CSR dimensions – the economy, employees and the local community and environment.

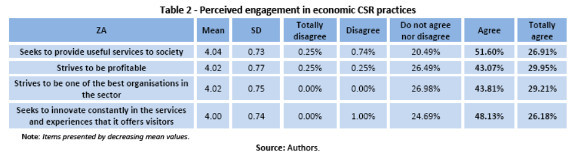

Concerning economic CSR, respondents revealed a positive perception of ZAs engagement in practices pertaining this dimension. As can be seen in Table 2, respondents believed that the theme park tries to provide a useful service to society, to be a profitable company and one of the best companies of its sector and constantly to innovate in the services it delivers to visitors. The mean rating of perceived engagement in the four proposed practices was 4.00 or above.

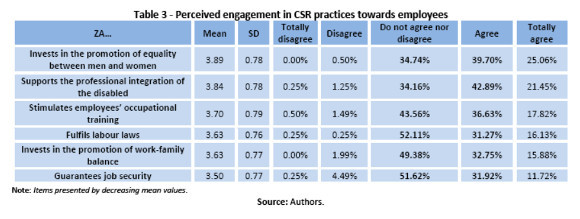

Regarding the companys engagement in CSR practices involving employees, the participants perceptions were also favourable. As can be seen in Table 3, most respondents selected a score of three or four on the response scale to express their opinion on this matter. The mean rating of engagement in the six proposed items varied between 3.50 and 3.89. The company was perceived as promoting gender equality, supporting the integration of the disabled in the job market, fostering the training of its staff, fulfilling the labour laws, investing in work-life balance and guaranteeing job security.

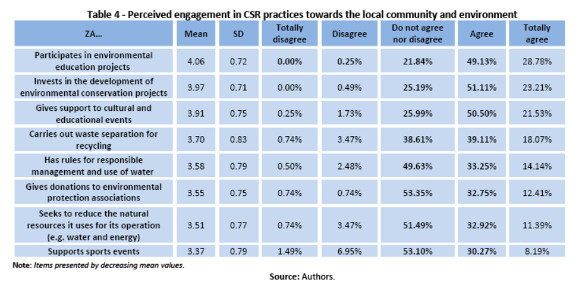

The engagement of ZA in CSR practices involving the local community and environment was also rated in a positive way. The mean rating of perceived engagement in the eight proposed items varied between 3.37 and 4.06 (see Table 4). ZAs participation in environmental education projects was the most salient practice for respondents, probably due to the companys mission and values. Its support for sport events was, in contrast, the least salient practice.

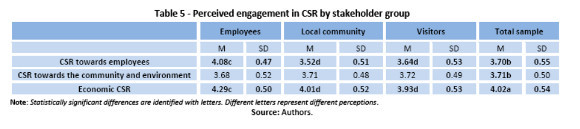

Although the ZAs perceived engagement in the three dimensions was relatively high (see Table 5), the performance of paired sample t-tests revealed that ZAs engagement in economic CSR practices (M = 4.02; SD = 0.54) was more salient for respondents than its engagement in other dimensions (t(404) = -14.475, p < 0.000; t(404) = -13.961, p < 0.000; t(404) = -0.396, n.s.). Therefore, while recognising the companys efforts towards meeting the needs and expectations of employees, the community and the environment, participants felt that the main focus of the companys social responsible performance is on the economic domain.

Moreover, the performance of analyses of variance (ANOVA), to compare the opinion of the three stakeholders groups, showed that employees had an even more positive perception of the companys engagement in practices regarding the economy (F(2,404) = 13.938, p < 0.000) and employees dimensions (F(2,404) = 29.291, p < 0.000) than visitors and local community members. No differences were found regarding the ZAs perceived engagement in CSR practices towards the community and environment (F(2,404) = 0.140, n.s.).

4.2 Perceived impact of ZAs business activities

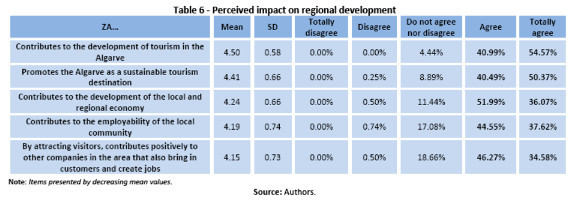

A second objective of the present study was to evaluate the perceptions of stakeholders regarding the impact of the companys activities on regional development (i.e. employability, tourism and the economy) and environmental awareness. Regarding the perceived contribution of ZA to regional development, the majority of respondents felt that the company has a high impact in this domain. As can be seen in Table 6, the mean rating of the five items that assessed this matter was 4.15 or above.

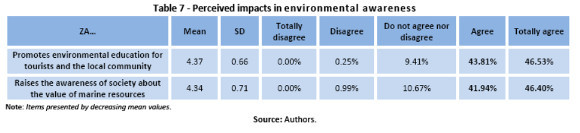

In the same way, participants felt that the company has a positive impact in terms of increasing the environmental awareness of visitors and members of the local community, namely, by raising awareness about marine resources (see Table 7).

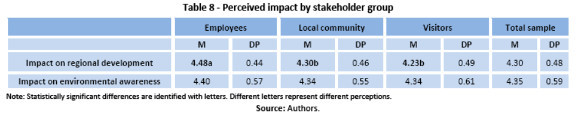

The performance of a paired sample t-test revealed that there were no differences in the level of impact attributed by respondents to the two dimensions (t(404) = 1,843, n.s.). This indicates that the company was regarded as having an equally important impact in both domains (see Table 8).

Nonetheless, comparing the responses of the three stakeholders by performing ANOVAs allowed the researchers to verify that employees perceived an even greater impact on regional development than visitors and members of the local community (F(2,404) = 7.844, p < 0.000). No differences were found regarding ZAs impact on environmental awareness (F(2,404) = 0.287, n.s.).

4.3 Relationship between perceived CSR practices and impacts

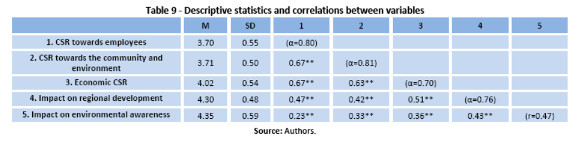

The third goal of the present study was to understand if stakeholders opinions regarding the selected companys engagement in CSR practices were related to the impact attributed to its regular functions. The performance of Pearson correlations revealed that these variables are positive and significantly related. As presented in Table 9, the perceived impact on regional development is moderately related to the companys engagement in economic CSR practices (r = 0.51, p < 0.01), practices towards employees (r = 0.47, p < 0.01) and also the community and environment (r = 0.42, p < 0.01). The ZAs perceived impact on environmental awareness is also positively related to CSR performance, but the coefficients are relatively lower (the economy r = 0.36; the community and environment r = 0.33; employees r = 0.23, all p < 0.01).

5. Discussion and conclusions

This study sought to examine the opinion of employees, local community and visitors on the practices of ZA in the area of CSR. Surveying these three stakeholders simultaneously allowed the characterisation of the CSR practices of the selected organisation based on the perspectives of different internal and external stakeholders. This is a sustainable methodological approach still uncommon in tourism research (Coles et al., 2013). In addition, the present study adopted a three-dimensional approach to CSR measurement (i.e. the economy, employees and the community and environment) that allowed the triangulation of these perceptions from the perspective of each of the stakeholder groups surveyed.

The results reveal that employees, members of the local community and visitors have an extremely positive view of ZAs engagement in CSR practices. Most respondents emphasised the responsible economic practices of the theme park and felt that it was also involved in practices that benefit employees, the community and the environment. Interestingly, employees reported even more positive perceptions of internal CSR practices (i.e. the economic and employee dimensions) than the other stakeholders did. This difference could be based on a better knowledge of the companys practices, given that, as members of the theme park staff, employees have, at least theoretically, easier access to information about the companys regular functions. In fact, employees play an important role in terms of CSR, as agents, observers and many time beneficiaries of socially responsible practices (Collier & Esteban, 2007; Maignan & Ferrell, 2001). If this is the case, this finding indicates the need to disclose and communicate CSR practices better to external stakeholders.

Despite a positive appreciation of the companys engagement in the three CSR dimensions, participants felt that the company is particularly engaged in economic CSR practices. This finding is similar to those of previous studies, namely, Martinéz et al.s (2013) research, which found that the economic dimension tends to be the most highly rated factor, as compared to social and environmental dimensions of tourism companies, specifically in terms of their long-term sustainability.

The impacts of ZAs activities were also generously assessed by respondents, who valued the companys important economic role in terms of contributing to regional employment, the local economy and tourism, as well as ZAs contribution to increasing the awareness of visitors and members of the local community regarding the conservation of marine species and the environment as a whole. A significant difference between employees and other participating stakeholders also was found. Employees felt that the theme park has an even stronger impact on regional development than other groups did. This might be again the result of greater access to this tourism companys information based on employment, but future studies could explore the reasons underlying this difference, given that alternative explanations might also be valid. All perceptions are intercorrelated, emphasising that perceptions of CSR are positively related to the benefits and sustainability of the companys activities.

Despite these interesting and useful findings, they need to be interpreted carefully, taking into consideration the limitations of the present study. As a descriptive case study, the results describe a given organisational reality, and generalisation to other companies should be done cautiously. The non-probabilistic nature of the samples implies the same level of caution. Future studies could address these limitations and assess the stability of the results reported here.

Future research could also extend this study by surveying a larger number of stakeholders about a larger set of CSR practices and larger number of impacts. Regarding stakeholders, it would be interesting to include other groups such as partners, suppliers and local authorities (see Lyra & Souza, 2013, 2015). In the same way, a larger number of socially responsible practices could be assessed, namely, practices involving consumers, suppliers and corporate governance. In addition, the type of impacts considered in the present study could be extended. In this study, attention was focused on positive contributions, but, as argued by Martins and Costa (2009), theme parks also can have negative impacts on environmental, economic and sociocultural domains.

In summary, the three stakeholder groups were largely aligned in their perceptions, agreeing that the selected company engages in CSR and generates positive contributions to the community, both in economic and non-economic domains. Based on the results, this studys approach could constitute a useful methodology when evaluating and monitoring sustainable CSR practices in the long term.

Acknowledgments

1. The authors are very grateful to Zoomarine Algarve for its willingness to participate in the study, to all students that voluntarily helped to collect the data and to all participants that voluntarily took the surveyed.

2. This study was partially supported by Fundação para a Ciência e a Tecnologia through a postdoctoral fellowship to the third author (SFRH/BPD/76114/2011).

References

Araya, M. (2003). Negociaciones de inversión y responsabilidad social corporativa: Explorando un vínculo en las Américas. Revista Ambiente y desarrollo de CIPMA, 19 (3/4), 74-81. [ Links ]

Bonilla-Priego, M., Font, X., & Pacheco-Olivares, M. (2014). Corporate sustainability reporting index and baseline data for the cruise industry. Tourism Management, 44, 149-160. [ Links ]

Carroll, A., & Shabana, K. (2010). The business case for Corporate Social Responsibility: A review of concepts, research and practice. International Journal of Management Reviews, 12 (1), 85-105. [ Links ]

Carroll, A. (1979). A Three-Dimensional Conceptual Model of Corporate Performance. The Academy of Management Review, 4 (4), 497-505. [ Links ]

Coles, T., Fenclova, E., & Dinan, C. (2013). Tourism and corporate social responsibility: A critical review and research agenda. Tourism Management Perspectives, 6, 122-141. [ Links ]

Collier, J., & Esteban, R. (2007). Corporate social responsibility and employee commitment. Business Ethics: A European Review, 1, 19-33. [ Links ]

Contreiras, J. P. (2011). Gestão pela cultura ética e de responsabilidade social nas organizações hoteleiras de 4 e 5 estrelas no Algarve como fatores de atração de candidatos de potencial elevado. Unpublished doctoral thesis. Évora: Universidade de Évora. [ Links ]

Cordeiro, I., Leite, N., & Partidário, M. (2009). Considerações sobre instrumentos de avaliação de sustentabilidade de destinos turísticos. Revista Turismo e Desenvolvimento, 12, 81-95. [ Links ]

Cowper-Smith, A., & Grosbois, D. (2011). The adoption of corporate social responsibility practices in the airline industry. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 19 (1), 59-77. [ Links ]

Dahlsrud, A. (2008). How corporate social responsibility is defined: An analysis of 37 definitions. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management, 15, 1-13. [ Links ]

Duarte, A. (2011). Corporate social responsibility from an employees perspective: Contributes for understanding job attitudes. Unpublished doctoral thesis. Lisboa: ISCTE-IUL. [ Links ]

Duarte, A., Gomes, D., Neves, J. (2014). Finding the jigsaw piece for our jigsaw puzzle with corporate social responsibility: The impact of CSR on prospective applicants responses. Management Research: Journal of the Iberoamerican Academy of Management, 12 (3), 240-258. [ Links ]

Duarte, A., Mouro, C., & Neves, J. (2010). Corporate social responsibility: Mapping its social meaning. Management Research: Journal of the Iberoamerican Academy of Management, 8 (2), 101-122. [ Links ]

European Commission. (2001). Green paper: Promoting a European framework for corporate social responsibility. Brussels: EU Commission. [ Links ]

European Commission. (2011). A renewed EU strategy 2011-14 for corporate social responsibility. Bruxelas: EU Commission. [ Links ]

Falcetta, F. (2004). Responsabilidade social nas empresas turísticas: Os registros da imprensa. In M. Bahl (Org.), Turismo com Responsabilidade Social (pp. 393-404). São Paulo: Roca Editora. [ Links ]

Ferraz, F., Schön, M., & Gallardo-Vásquez, D. (2011). A divulgação da informação socialmente responsável nos estabelecimentos hoteleiros portugueses. In Book of Proceedings - International Conference on Tourism & Management Studies - Algarve 2011 (Vol. I, pp. 552-564). Faro: Universidade do Algarve. [ Links ]

Figueira, V., & Dias, R. (2011). A Responsabilidade social no turismo. Lisboa: Escolar Editora. [ Links ]

Font, X., Guix, M., & Bonilla-Priego, M. (2016). Corporate social responsibility in cruising: Using materiality analysis to create shared value. Tourism Management, 53, 175-186. [ Links ]

Freeman, E. (1984). Strategic management: A stakeholder approach. Boston: Pitman. [ Links ]

Gimenes, M. (2004). Alimentos e bebidas e responsabilidade social: Experiências e possibilidades. In M. Bahl (Org.), Turismo com Responsabilidade Social (pp. 457-470). São Paulo: Roca Editora. [ Links ]

Goodwin, H., & Francis, J. (2003). Ethical and responsible tourism: Consumer trends in the UK. Journal of Vacation Marketing, 9 (3), 271–284. [ Links ]

Holcomb, J., Okumus, F., & Bilgihan, A. (2010). Corporate social responsibility: What are the top three Orlando theme parks reporting? Worldwide Hospitality and Tourism Themes, 2 (3), 316-337. [ Links ]

Jesus, M., & Batista, T. (2014). The corporate social responsibility in the Algarve. Tourism & Management Studies, 10, 111-120. [ Links ]

Article history:

Submitted: 20.10.2015

Received in revised form: 27.12.2015

Accepted: 29.12.2015