Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Acessos

Acessos

Links relacionados

-

Similares em

SciELO

Similares em

SciELO

Compartilhar

Tourism & Management Studies

versão impressa ISSN 2182-8458

TMStudies vol.12 no.1 Faro mar. 2016

https://doi.org/10.18089/tms.2016.12109

TOURISM: SCIENTIFIC PAPERS

Health Tourism: Conceptual Framework and Insights from the Case of a Spanish Mature Destination

Turismo de salud: marco conceptual y perspectivas desde el caso de un destino maduro español

Antonio Padilla-Meléndez1, Ana-Rosa Del-Águila-Obra2

1Universidad de Málaga, Facultad de Estudios Sociales y del Trabajo, Campus de Teatinos (Ampliación), s/n; 29071, Málaga, España. E-mail: apm@uma.es

2Universidad de Málaga, Facultad de Estudios Sociales y del Trabajo, Campus de Teatinos (Ampliación), s/n; 29071, Málaga, España. E-mail: anarosa@uma.es

ABSTRACT

Despite the already published work around health tourism in the last two decades, there continues to be, firstly, a jungle of similar and mixed concepts (most of the previous studies have analysed different aspects of this type of tourism, mainly medical tourism, without providing a clear and integrated framework). And, secondly, an area of scarcity of research on mature destinations (mostly Asian countries have received the attention). Filling these gaps are the two research questions of the paper. To answer them, firstly, a simplified framework integrating the different concepts and approaches to health tourism is proposed. Secondly, the complexity of the continuum of different practices associated with the supply side of health tourism is illustrated with a case study of a mature destination. Empirical data from a web and telephone based questionnaire conducted on a randomly selected sample of health tourism establishments of a self-developed data set, and some personal interviews, have been analysed to describe health tourism in the Costa del Sol, a mature Mediterranean destination in the south of Spain. This paper contributes to the literature by showing the complexity of the several practices included in the conceptual umbrella of health tourism in a mature destination, and the main enablers and barriers for cooperation between tourism and health companies. Some managerial and political implications are also included.

Keywords: Health tourism, medical tourism, wellness tourism, Costa del Sol.

RESUMEN

A pesar del trabajo previo publicado sobre el turismo de salud en las dos últimas décadas, aún continua existiendo, en primer lugar, una jungla de conceptos similares y mezclados (la mayoría de los estudios previos han analizado diferentes aspectos de este tipo de turismo, principalmente el turismo médico, sin aportar un marco claro e integrado). Y, en segundo lugar, sigue habiendo una escasez de investigación en destinos turísticos maduros (la atención se ha centrado principalmente en países asiáticos). Las dos preguntas de investigación de este artículo son dar respuestas a estas necesidades. Para responderlas, en primer lugar, se propone un marco simplificado que integra los diferentes conceptos y aproximaciones al turismo de salud. En segundo lugar, se ilustra la complejidad del continuum de diferentes prácticas asociadas con la oferta del turismo de salud, con el estudio de un caso de un destino maduro. En concreto, se han analizado datos empíricos de un cuestionario basado en web y en teléfono, realizado a una muestra aleatoriamente seleccionada de una base de datos propia de establecimientos turísticos, y de varias entrevistas personales, para describir el turismo de salud en la Costa del Sol, un destino mediterráneo maduro ubicado en el sur de España. Este trabajo contribuye a la literatura mostrando la complejidad de las diversas prácticas incluidas en la sombrilla conceptual del turismo de salud en un destino maduro, y los principales facilitadores y barreras para la cooperación entre las empresas turísticas y de salud. También se incluyen varias implicaciones directivas y políticas.

Palabras clave: Turismo de salud, turismo médico, turismo de bienestar, Costa del Sol.

1. Introduction

Health tourism is a relatively recent phenomenon that has developed in the last two decades (García-Altés, 2005; Kaspar, 1990; Reisman, 2010). The health tourism trend was initially thought to be propelled by people seeking cheaper alternatives to cosmetic procedures; however, increasingly more vital health procedures (such as heart valve surgeries or knee transplants) are being offered and considered in destinations such as Thailand, Singapore, India, Taiwan (Ye, Qiu, & Yuen, 2011), or Malaysia (Musa, Thirumoorthi, & Doshi, 2012). Moreover, nowadays tourists, instead of seeking long-haul destinations, prefer shorter trips; short distance, medium, and known destinations. In addition, by 2030, visiting friends and relatives, health, religion, and other purposes will represent 31% of all international arrivals (UNWTO, 2013). Consequently, the emergence of a global market in health services is having profound consequences for other sectors, such as health insurance, delivery of health services, publicly funded healthcare, and the spread of medical consumerism (Turner, 2010). This has changed the regulations at a country level. Particularly in Europe, all 28 member states have declared themselves as a medical tourism destination, offering a multitude of treatments, and with the rati?cation of the EU Directive on Cross Border Healthcare 2013, a framework is provided for citizens of the European Union to exercise their rights to medical treatment in any member state (European Parliament, 2011). These European countries could become international health services, but, for example, data for the UK suggests that far from being a net importer of patients, the UK is now a clear net exporter of medical travellers. In 2010, an estimated 63,000 UK residents travelled for treatment, while around 52,000 patients sought treatment in the UK (Hanefeld, Horsfall, Lunt, & Smith, 2013). In the case of Spain, according to a Euromonitor (2014) study, medical tourism increased in current value terms by 1%, with many inbound tourists travelling to Spain for knee and back prosthesis from Germany and for dental surgery from the UK, and Russian and Arabic patients normally looking for beauty treatments. Treatments are also cheaper than in other European countries, and medical tourism is predicted to show a healthy growth in the coming years, due to promotional efforts by the Spanish Tourism Office and the private sector to position Spain among the main options for medical treatments in Europe. Consequently, it is expected that Spain will remain an attractive destination for foreign tourists, mainly due to price convenience and the quality of the medical service (Euromonitor, 2014).

The concept of health tourism recently emerged in the international academic community to refer to travelling to other countries to seek medical treatment at a lower price or to avoid waiting lists in the country of origin (Stojanovic, Stojanovic, & Randelovic, 2010). Medical tourism has been considered as an emerging niche (Connell, 2006; Hunter-Jones, 2005), around which a global offer of services has been built. It is considered to be a product innovation developed mainly by the hotel industry (Hjalager, 2010)with the healthcare hotel (Han, 2013)and medical organisations (Heung, Kucukusta, & Song, 2011), and aimed at both national and international tourism; in certain areas, it has become an alternative to the seasonal nature of tourism demand. Consequently, intermediaries (medical tourism companies) are of new signi?cance (Connell, 2013).

However, despite the described practical and academic relevance, there are few theoretical or empirical studies to delineate this sector and to characterise this new offering, so there remains a research gap on the topic (Smith & Kelly, 2006). In particular, there is a lack of an integrative perspective that takes into account all the emerging issues related to medical tourism (Novelli, Schmitz, & Spencer, 2006) and wellness tourism (Huijbens, 2011) and there is still a need to clarify the different concepts. In addition, a call for greater empirical research on medical tourism in Europe has been made (Carrera & Lunt, 2010), arguing that such research will contribute toward knowledge of patient mobility and the broader theorisation of medical tourism. Most of the empirical research has been conducted in some geographical areas, such as Asia, mostly regarding India, Hong Kong, and Korea. Nevertheless, the differences in the development of health (medical and wellness) tourism in different geographical areas, in particular emerging versus mature tourism destinations, needs more research. Importantly, with the projected growth of medical tourism, as it is considered to be one of the fastest-growing tourism sectors in the world (Han & Hwang, 2013), the need to know more about it is urgent (Cormany & Baloglu, 2011), particularly regarding its implications for regulation (Hall, 2013).

The Costa del Sol, a mature destination in Spain, has received growing interest in the literature regarding seasonal demand (Fernández-Morales & Mayorga-Toledano, 2008) and residents perceptions of tourism development (Almeida-García, Peláez-Fernández, Balbuena-Vázquez, & Cortés-Macias, 2016). However, to the authors knowledge there is no academic research about health tourism in this destination, and it is very scarce in Spain (with the exception of the study on Gran Canaria by Medina-Muñoz and Medina-Muñoz (2013)), making this paper the first academic attempt to describe and analyse this sector in the Costa del Sol.

To sum up, despite the already published work around health tourism, there continues to be, firstly, a jungle of similar and mixed concepts (most of the previous studies have analysed different aspects of this type of tourism, mainly medical tourism, without providing a clear and integrated framework to analyse it). And, secondly, an area with scarce research on mature destinations (mostly Asian countries have received the attention). To answer these two research gaps, the two main research questions of this paper are defined as: (RQ1) Which kind of activities are involved in the health tourism segment? (RQ2): Could tourism sector companies develop strategies of expansion based on health tourism in mature destinations? To answer RQ1, a conceptual framework has been proposed. To answer RQ2, four stages have been followed: a literature review, web content analysis, questionnaires, and interviews. Based on a mixed method, empirical data from a telephone-based questionnaire conducted on a random sample of health tourism establishments of a self-developed data set, and from personal interviews, have been analysed to describe the case study of a mature and seaside tourism destination on the Spanish Mediterranean coastline (Costa del Sol in Andalucía). The gathered data has allowed a description of the sector, identification of enablers of and barriersto the health tourism sector in the Costa del Sol, and the proposal of some future strategies. Consequently, this paper addresses these gaps by, firstly, providing a simplified framework that integrates the different concepts and approaches to health tourism and, secondly, illustrating all the complexity of the continuum of different practices associated with the supply side of health tourism through a case study of a mature destination.

2. Theoretical framework

According to the OECD (Lunt et al., 2011), medical tourism is related to the broader notion of health tourism, which includes historical antecedents of spa towns and coastal localities and other therapeutic landscapes. In the literature, health and medical tourism has been considered as a combined phenomenon with different emphases. Health tourism is the organised travel outside ones local environment for the maintenance, enhancement or restoration of an individuals well-being in mind and body and medical tourism is delimited to organised travel outside ones natural health care jurisdiction for the enhancement or restoration of the individuals health through medical intervention (Carrera & Bridges, 2006, p. 449). It has been suggested that sometimes the boundaries between these terms are not always clear as a continuum exists from health (or wellness) tourism involving relaxation exercise and massage, to cosmetic surgery (ranging from dentistry to substantial interventions), operations (such as hip re-placements and transplants), to reproductive procedures and even 'death tourism? (Connell, 2013, p. 2). Health tourism is the sum of all the relationships and phenomena resulting from travel and accommodation of tourists, whose main purpose is to preserve or promote their health (Mueller & Kaufmann, 2001), this being the definition adopted in this paper. Tourists are increasingly demanding general health-related services, such as mental and spiritual renewal, recreational activities, sports, etc. (Witt, 1990), so health tourism is becoming more and more popular (Goodrich & Goodrich, 1987). These tourists require a comprehensive package of services including beauty care and fitness, nutrition and healthy diet, and relaxation and meditation (Smith & Kelly, 2006).

More recently, Chuang, Li, Lu, and Lee (2014), using main path analysis, a unique quantitative and citation-based approach, have analysed the signi?cant development trajectories, important literature, and recent active research areas in medical tourism, finding two distinctive development paths. One path focuses more on the evolution of medical tourism, the motivation factors, marketing strategies, and economic analysis, while the other path emphasises organ transplant and related issues. Interestingly, these two paths eventually merge to a common node in the citation network, which foresees transplantation to beauti?cation being the future research direction trend. However, the current literature still uses the terms health tourism, medical tourism, and wellness tourism very loosely and unsystematically (Fetscherin & Stephano, 2016). Consequently, there is a need to differentiate these terms.

2.1 Medical tourism

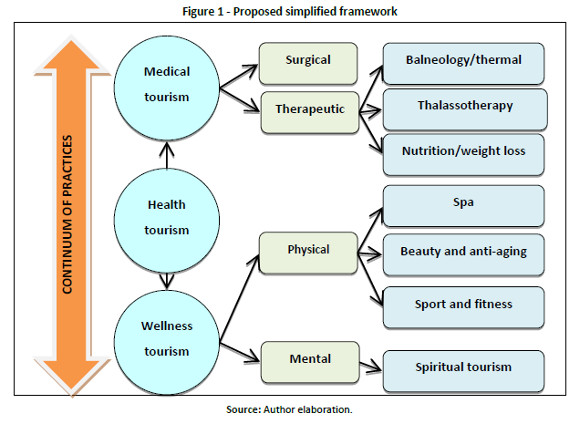

Medical tourism is the act of travelling overseas for treatment and care (Carrera & Lunt, 2010; Singh, 2013). See Connell (2013), for a complete and in-depth review of medical tourism definitions. It is marketed as a niche product that incorporates both medical services and tourism packages (Connell, 2006; Yu & Ko, 2012), provided that the relation of medical travel with tourism is old (Hjalager, 2009). The treatments may range from highly invasive surgeries (heart, hip resurfacings, and plastic surgeries) to less invasive procedures (dental work) and wellness treatments (Reddy, York, & Brannon, 2010). Wellness will be considered separately in this paper. This medical tourism trend was initially thought to be propelled by people seeking cheaper alternatives to cosmetic procedures, however, increasingly more vital health procedures (such as heart valve surgeries or knee transplants) have been offered and considered in destinations such as Thailand, Singapore, India, Taiwan (Ye et al., 2011), or Malaysia (Musa et al., 2012). In fact, there are different practices such as surgical (which involves certain operations) and therapeutic tourism (which involves healing treatments) (Smith & Puckzó, 2008). Much medical tourism is short distance and diasporic, despite being part of an increasingly global medical industry that is linked to the tourism industry (Connell, 2013). There is a need for a delimitation and integration of concepts. In addition, while health tourism is a potential revenue source, it also competes with the domestic health sector. Consequently, it could transfer some of the healthcare problems of the developed world to the developing world (Vijaya, 2010). Consequently, analysis of this topic is needed.

As market drivers for medical tourism, push and pull factors can be considered. Push factors in the traveller origin region, which explain the demand for medical tourism, have been known to include the lack of advanced medical technology or expertise, the quality of services, and the existence of legal, moral, or religious ethical issues, for example in the case of reproductive tourism (Moghimehfar & Nasr-Esfahani, 2011). In terms of pull factors, which shape patients decisions (Crooks et al., 2010), tourists may assess a potential destination based on its record of accomplishment in providing a healthy environment to visitors. More recently, Fetscherin and Stephano (2016) have consider push and pull factors for medical tourism. Pull factors focus on the offer for medical tourism. They are mainly related to the medical tourism destination, such as the countrys overall environment (e.g., stable economy, countrys image), the healthcare and tourism industry of the country (e.g., healthcare costs, popular tourist destination), and the quality of the medical facilities and services (e.g., quality care, accreditation, reputation of doctors). As a consequence, a number of governments, for example, the Singapore government (Lee, 2010), have sought to develop medical tourism to further enhance their tourism industries, believing that such efforts can increase both the number of tourists and tourist revenues. More recently, a medical tourism index has been developed to measure the attractiveness of a country as a medical tourism destination in terms of overall country environment, healthcare costs and tourism attractiveness, and quality of medical facilities and services (Fetscherin & Stephano, 2016).

Medical wellness is similar to medical tourism and different types of medical wellness can be considered from the literature: balneology/thermal therapy, thalassotherapy, and nutrition/weight loss. Balneology/thermal therapies are comparable to spas, but they require professional medical services and supervision and sometimes are known as balneotourism. Thalassotherapy includes the development of therapeutic practices using the beneficial aspects of the marine environment, such as the climate, seawater, seaweed, algae, mud, and sand (Smith & Puckzó, 2008). Nutrition/weight loss includes a wide range of treatments related to weight loss, diets, healthy eating programmes, detoxing, anti-obesity prescription, and treatment of eating disorders such as anorexia and bulimia.

2.2 Wellness tourism

According to Bushel and Sheldon (2009) wellness tourism is an all-encompassing term relating to medical, health, sports/?tness, adventure, or transformational types of travel that improves ones well-being. They de?ne wellness tourism as a holistic mode of travel that integrates a quest for physical health, beauty, or longevity, and/or a heightening of consciousness or spiritual awareness, and a connection with community, nature, or the divine mystery (p. 11). The term wellness is widely used in relation to tourism (Clarke, 2010; Hjalager & Flagestad, 2012) and in historical terms wellness tourism is the first manifestation of health tourism, when considering the activities of ancient Rome and Greece and the European elite during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries (Smith & Kelly, 2006). More recently, Voigt and Pforr (2014) have focused on wellness destination development, including the importance of authenticity and uniqueness, providing international case studies and examples from established and emerging wellness tourism destinations. Wellness tourism is the sum of all the relationships and phenomena resulting from a trip whose main purpose is to preserve and promote health, which, from the supply side, needs a specific tourism infrastructure in order to be developed (specifically it needs facilities that include health services and overnight guest accommodation) (Mueller & Kaufmann, 2001). Wellness is more of a psychological than a physical state (Smith & Kelly, 2006), being a state of health that features the harmony of body, mind, and spirit. After the literature review, the following topics are covered: spa, beauty and anti-aging, sport and fitness, and spiritual tourism.

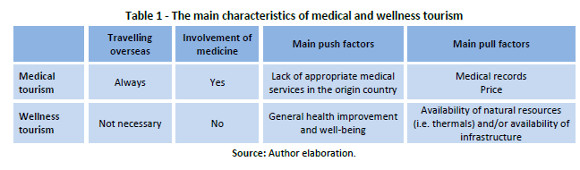

Spa is an acronym for Sanus per Aquam (Latin: health through water), meaning water-based therapies, and it has been defined as an entity devoted to enhancing overall well-being through a variety of professional services that encourage the renewal of mind, body, and spirit. It is currently one of the fastest growing subsectors of health tourism (Mak, Won, & Chan, 2009). Normally, spas are served by plain tap water to which some salt or additives are added. The benefits of spas for the body are focused on temperature changes and the action of water pressure on the body. Beauty and anti-aging includes different programmes that can help women or men to obtain the perfect physique, concerning beauty services, cosmetics, dermatology, as well as services that specifically address age-related health and appearance issues (Smith & Puckzó, 2008). Sport and fitness are wellness-promoting experiences that feature participation in sports at leisure or in an organised competitive setting, including opportunities to assess and improve ones fitness level with a specialist (Sheldon & Park, 2009). Finally, spiritual tourism is all-purpose travel that is based on an intentional search for connection with the spiritual self (Mansfeld & McIntosh, 2009). This is commonly achieved by consciously visiting a revered site to engage in religious devotion. The next table summarises the main differences between the two described types of health tourism (Table 1).

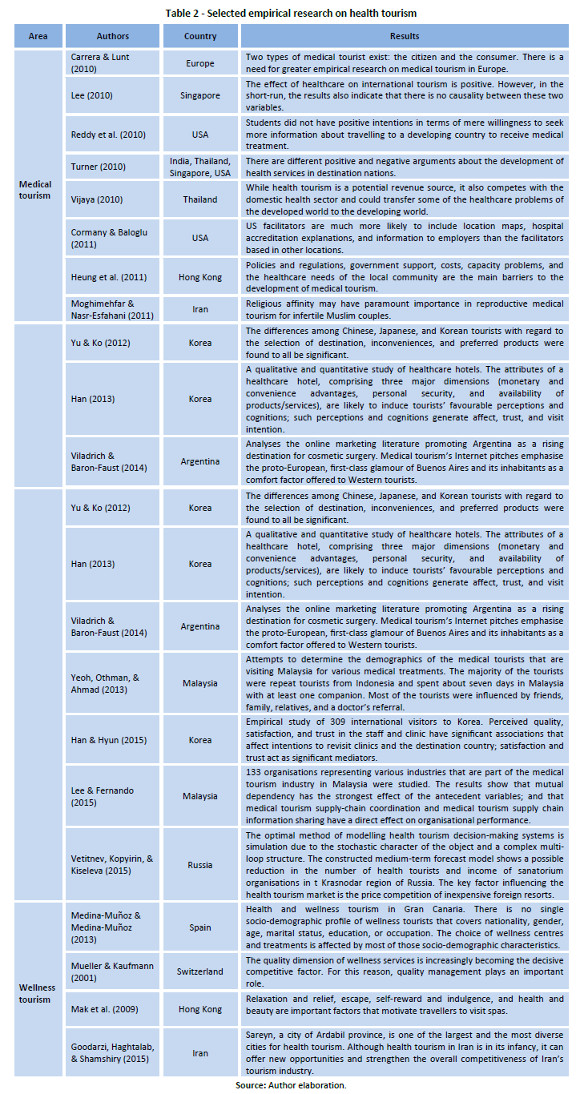

2.3 Empirical studies

In order to find, analyse, and organise the different practices around health tourism to be able to later describe the case study, a literature review was conducted in three phases: data collection, data analysis, and synthesis. Data on papers published in this area was collected from databases such as ISI Web of Knowledge and Scopus, among others. Different combinations of the items health, medical, and wellness tourism were searched for. Papers were selected according to their topic and inclusion of empirical data. Several papers were found, including literature reviews (Crooks, Kingsbury, Snyder, & Johnston, 2010), quantitative studies (Lee, 2010), and qualitative studies (Heung et al., 2011; Yu & Ko, 2012) (see Table 2).

Regarding the practices included in health tourism, the OECD (Lunt et al., 2011) considers: cosmetic surgery (breast, face, liposuction), dentistry (cosmetic and reconstruction), cardiology/cardiac surgery (bypass, valve replacement), orthopaedic surgery (hip replacement, resurfacing, knee replacement, joint surgery), bariatric surgery (gastric bypass, gastric banding), fertility/reproductive systems (IVF, gender reassignment), organ, cell, and tissue transplantation (organ transplantation, stem cells), eye surgery, diagnostics, and check-ups.

In addition, in a recent attempt to produce a complete taxonomy, McKercher (2016) has identified five broad need families (pleasure, personal quest, human endeavour, nature, and business), incorporating 27 product families and 90 product classes. Medical and wellness tourism has been included in the personal quest need family, which re?ects the fact that some people travel today for more personal reasons associated with self-development and/or learning, in this case for the desire for enhanced physical and mental health. Included in the medical/wellness product family are (McKercher, 2016) procedures (lifestyle: dental, eye care, cosmetic; surgical: minor invasive, major invasive (transplant, gender reassignment, reconstructive, other forms )), health (routine check-up, general treatments, physical healing: non-surgical), and wellness (spa, massage, beauty treatments, spiritual, psychological, detoxification, new age treatments).

After analysing the mentioned literature and the proposed lists, the complexities of health tourism, as a varied sector have to be recognised. Therefore, a simplified framework is proposed to help understand and describe the mentioned case (see Figure 1).

3. Methods

Since we wanted to carry out an in-depth study on the sector in a mature destination (Costa del Sol) and no database is available with all the existing establishments, a data set was built of companies developing activities related to health tourism in order to describe their activities and analyse their main strategies in terms of marketing and cooperation strategies. As there were no official lists of establishments, a snowball method was applied to identify the population of companies in the sector. The companies in the Costa del Sol developing activities related to health tourism were identified using a preliminary directory from the Chamber of Commerce of the province, several contacts with specialised agents, use of other directories, and searches using Google with keywords such as Málaga, Costa del Sol, spa, balnearies, etc. The total number of companies identified in this sector in the region was 109 establishments.

Information from the sector has been collected following a three-pronged strategy: (1) Web content analysis or collection of information on the identified companies through analysis of their web pages; (2) Administration of a web-based questionnaire, assisted by phone calls to the managing directors of the identified establishments (69 valid answers, answer rate 63.30%); and (3) Interviews with ten managers of the sector in order to better interpret the initial results.

The web content analysis produced an inventory of a wide range of treatments and specific complementary services that made a comparison between them difficult, even within the same type of establishment. For this reason, this inventory has utility as an approximation of the subsector. It was completed with a web and phone based questionnaire about the characteristics of the health establishments, equipment, treatments, commercialisation strategies (tour operator, direct sales, and internet), and needs in terms of promotion and internationalisation. Finally, a qualitative data from transcripts of ten in-depth interviews with managers of spa hotels completed the empirical information (Strauss & Corbin, 1990). Quantitative and qualitative data were analysed to describe the sector and answer the research questions.

4. Results and interpretation

Health tourism in the Costa del Sol

The Costa del Sol is a mature destination, located in southern Spain in the Andalucía region. In 2014, international tourist arrivals in Spain reached 64.9 million (Instituto de Estudios Turísticos, 2015), and Andalucía, where the Costa del Sol is located, received 10.7% of that total. This area is highly dependent on seasonal tourism, as there is a seasonal concentration of hotel demand in the Costa del Sol (Fernández-Morales & Mayorga-Toledano, 2008). Consequently, exploring new products such as health tourism to reduce that seasonality is relevant. Well-known related companies, such as the Molding Clinic or the Ritz-Carlton Hotel Villa Padierna Marbella, are located in the Costa del Sol. In addition, in 2012 the Málaga Health Foundation (2015) was established as a private non-profit institution created to promote Málaga and the Costa del Sol as an international healthcare destination. It is conceived as a local self-regulated club and as a quality label for its members. Any organisation related to medical travel or health tourism activities may become a member of Málaga Health, provided that it is considered to offer first-class services in the Costa del Sol area.

Demographics

As mentioned, a questionnaire-based study was conducted in the Costa del Sol (Andalucia, Spain). Regarding the demographics of the respondents, most had a university degree. As for the type of company, they were primarily spa hotels (47), private health clinics (10), beauty centres (5), spa and thalassotherapy centres (4), balneology centres (2), and an oncology clinic (1). Regarding the capacity of the facilities, there was also great variability between establishments, from centres with very low capacities (usually spas) to large capacities (usually hotels with a spa). The main players in the Costa del Sol health tourism sector are the hotels and beauty centres (wellness tourism), the private health clinics (medical tourism), and the balneology and thalassotherapy centres (medical wellness).

Description of the services

In terms of the customers capacity of the health establishments, there is great variability of centres, being the hotels with spa the largest ones. 56.52% of cases have a commercial department in the establishment, and a 21.74% have an international sales department. Other languages (98.55%) are spoken almost in all establishments (including English (97.06%), French (57.35%), and Portuguese (8.82%)).

In terms of the equipment of each establishment, the most common feature among the surveyed establishments was the inclusion of their own gym, with 86.96% of establishments having one. The least common feature is the sale of sports equipment (8.70%). The five most cited available facilities related to health tourism were a gym, swimming pool, massages/spa saloon, Jacuzzi, and sauna. Additionally, the most cited offered services for medical wellness and wellness (thalassotherapy/spa) were topical treatments (bath pressure, massage therapy, bath without pressure, stoves, and physiotherapy). For beauty and anti-aging, they were skincare, body treatments, body aesthetics, and aesthetic plastic surgery. For clinical oncology, they were brachytherapy, radiotherapy, and a prostate unit. Finally, for private health clinics, they were ophthalmology, oral and maxillofacial surgery, and orthopaedic surgery and traumatology.

Marketing strategy

56.52% of companies have a specific marketing department, employing an average of five employees. As for the origin of the customers, most of the clients where from countries other than Spain, with the UK and Germany being the main origin countries. Regarding the marketing activities, the clients had found out about the services of these companies through Internet publicity (30.41%), word of mouth from previous clients (25.35%), direct publishing of the company in newspapers (24.32%), and search engine marketing (16.22%). International clients has found out about the offer through tour operators (49.28%) and by recommendation from previous clients (40.58%). Only 15.94% of international customers access was through specialised agencies. 48.57% of the international tourists used the companys own established e-commerce facilities to buy the product. Regarding private hospitals and oncology clinics, 81.82% of them accepted the foreign health insurance policies of the patients. Respondents proposed some promotional actions that policymakers could use to promote this sector, such as its specific promotion at tourism fairs or specifically addressed publicity campaigns. Additionally, respondents indicated the need for better regulation in this sector, as sometimes people without appropriate qualifications conducted these activities, which had a negative effect on the quality offered to customers.

Interviews

Regarding the analysis of the interviews transcripts, some pull factors, for example marketing strategy, barriers, and the need for public support, emerged. Health tourism was mentioned as a different tourism sector that has to be managed, promoted, and sold in a specific manner. Moreover, strategies might be formulated by destination managers and tourism operators to avoid losing market share and to develop tourism in a sustainable way (Dwyer et al., 2009). Regarding the pull factors, all of the surveyed hotels mentioned the existing demand as the main reason for the existence of this type of activity. For example, some participants mentioned, At first it was only to give luxury services to golf customers, but now we have customers who demand health, beauty, and wellness. This was mentioned together with the bigger margins: For us, the main reason for offering wellness services is because they offer much higher returns and breaks with the seasonal demand. Consequently, there is a clear tendency in hotels to include wellness services, which act as pull factors for the demand, contributing to differentiating and diversifying the hotels. Some interviewees mentioned that the beach is not enough and tourists demand complementary services such as wellness services. Furthermore, medical services remain separate from hotels in hospitals, clinics, etc., dividing the sector between medical treatments for sick people and wellness services for peoples well-being. Although the same hotel can host medical and wellness guests at the same time, these two subsectors have to be considered separately when deciding on marketing strategy (Mueller & Kaufmann, 2001).

Concerning the marketing strategy, the analysed establishments use their own marketing departments and mention the Internet and word of mouth recommendation as being important to selling the services directly. The health insurance policies in the case of medical tourism were also mentioned as relevant. Moreover, services are organised according to the main offer of the establishment, around medical, medical/wellness, or wellness. Finally, there is a clear distinction between medical and other services, but not regarding medical/wellness and wellness services. For example, nutrition/weight loss establishments normally also have spa facilities.

Finally, concerning the need for public support, there is a general call for this support from the explored sector. Thus, several strategies have been proposed, such as new promotional activity policies, government action to encourage investment in the medical tourism market, and cooperative efforts by all involved organisations to develop medical tourism products (Heung et al., 2011). As Denicolai, Cioccarelli, and Zucchella (2010) mention, tourism policies at the destination management level should create a local learning environment by promoting network initiative. Public support is needed to promote the sector and to promote collaboration among the different players.

Taking into account the different collected data, the enablers and barriers that exist in the sector to the development of health tourism can be analysed. Firstly, the factors that can be considered enablers include the richness, diversity, and complementarity of the offer of medical and wellness tourism in the Costa del Sol, the great diversity of specialised treatments, the complementarities with other tourism products available in the Costa del Sol (rural tourism, cultural tourism), high customer loyalty (a significant percentage of international customers (40.58%) comes to establishments on the recommendation of former customers), and the possibilities of e-commerce (direct sales on establishments own web pages already accounts for 24.64% of customers and 65.22% of customers use the Internet to find out about the companies services). Regarding loyalty, this is consistent with the findings of Yeoh et al. (2013), who found that 60% of patients were returning patients, indicating that almost every one of the medical tourists that has used the medical facilities in Malaysia has brought another new medical tourist into Malaysia.

Secondly, the factors that can be mentioned as barriers include insufficient tourism products developed specifically for health and wellness tourism, the low penetration in distribution channels, the training gaps in human resources, the lack of cluster relationships that would enhance the development of tourism (the association of companies that comprise the segment is recent, and devoted to medical tourism), and companies have to compete in prices with high quality services (which need large investment). There is a fragmentation of the sector in terms of the number of employees and capacity (in particular the centres of aesthetics, some of which have a single employee and the capacity for a single client), the lack of marketing departments, and the high concentration of sales through tour operators, which produce a margin reduction (49.28% of international customers come through tour operators).

5. Discussion and Conclusions

This paper proposes a simplified framework integrating the different concepts and approaches to health tourism. In addition, the complexity of the continuum of different practices associated with the supply side of health tourism is illustrated with a case study of a mature destination (Costa del Sol). It has been made clear that, similarly to what is happening in other tourist regions of the world (Reddy et al., 2010), in the Costa del Sol, as a mature destination, the health tourism sector has developed in recent years. However, there is still work to do to integrate, rationalise, and provide quality services around this activity. The lack of clarity in the offer of these services creates confusion in demand, and this is reflected in the marketing strategythis is a barrier to the development of the sector. Moreover, there is some resistance to introducing these services in traditional hotels.

Regarding RQ1 about the kind of activities involved in the health tourism segment, there are some important problems to differentiate the related practices, such as spa, wellness, and other health-oriented industries. From the literature review, these different practices have been defined. Health tourism includes medical tourism and wellness tourism. Medical wellness is very similar to wellness tourism, but there is the involvement of medicine. In medical wellness, there is balneology/thermal, thalassotherapy, and nutrition/weight loss. Medical tourism takes place when individuals decide to travel overseas with the primary intention of receiving medical (usually elective surgery) treatments and includes surgical tourism and therapeutic treatment. Wellness tourism is the sum of all the relationships and phenomena resulting from a trip whose main purpose is to preserve and promote health and includes spa, beauty and anti-aging, sport and fitness, and spiritual tourism. The majority of studies on health tourism are from the USA or Asia, while Europe is underrepresented. For example, Spain is a mature tourism destination, different to Taiwan or Singapore, and this could change the way health tourism is organised; tourists do not go from rich countries to less developed countries, largely as a result of the low treatment costs in other European countries.

Concerning RQ2 on whether the tourism sector companies could develop strategies of expansion based on health tourism in mature destinations, as mentioned, the existence of the health tourism sector and the main involved players has been identified in the empirical study. It is clearly considered as a different tourism sector that has to be managed, promoted, and sold in a specific manner. Regarding the marketing and distribution channels, the analysed establishments use their own marketing departments and, similarly to Connells (2013) findings, their brands are primarily spread by word of mouth, with the Internet being the next most important marketing channel. Health insurance policies are also mentioned as being relevant in the case of medical tourism. There is a clear distinction between medical and the other services, but not regarding medical/wellness and wellness services. For example, nutrition/weight loss establishments normally also have spa facilities. Incumbents can develop strategies for expansion based on enablers such as the already existing diversity in the offered services, the complementarity with other types of tourism, and the high loyalty of existing customers.

In addition, some improvements have to be made in the promotion strategy of health tourism, as some barriers have been found related to health tourism not being recognised as a different tourism product, the low penetration of the distribution channels, the fragmentation of the sector, and the need for more cooperation actions between the existing companies. Action such as the above-mentioned Málaga Health Foundation could contribute to reducing the relevance of this barrier. In addition, there is a dynamic of change in the sector, as wellness is not a static concept and is subjective and relative, thus always in flux. There is a clear tendency in hotels to include wellness services as pull factors for the demand and as a form of differentiation and diversification strategy. It has been mentioned how the beach is not enough and tourists demand complementary services such as wellness services. Furthermore, medical services remain separate from hotels in hospitals, clinics, etc., dividing the sector between medical treatments for sick people and wellness services for peoples well-being. Although the same hotel can host medical and wellness guests at the same time, these two segments have to be considered separately when deciding on marketing strategy (Mueller & Kaufmann, 2001).

There is also a need for more specialisation. Medical tourism companies, or medical brokerages, play a crucial role in advertising and selling health services across a global market. Wellness hotels should therefore specialise in providing relevant information, individual care, and a wide range of cultural and relaxation programmes. Barrier factors that have been mentioned include the need to keep costs low to compete on price and the necessary high quality of these services requiring large investment. Some of the market considers well-being not as a need, but rather as a luxury expense, so this is an additional barrier to the development of wellness tourism. In addition, the needs of wellness tourists will clearly vary enormously at different times and stages of their lives (Smith & Kelly, 2006).

Finally, the need for public support and regulation of this activity has been mentioned. This will be relevant for the future of the sector, as it would guarantee the mentioned minimum quality level. There is a general call for this support, with several strategies, such as new promotional activity policies, government action to encourage investment in the medical tourism market, and cooperation strategies by all involved organisations to develop medical tourism products (Heung et al., 2011) and a local learning environment around health tourism (Denicolai et al., 2010).

As conclusions, two main ideas arise. Firstly, the existence of a specific sector of health tourism that encompasses a wide range of tourist facilities and that is becoming an alternative to the seasonal nature of tourism demand has been revealed in a mature destination. In a time of economic crisis, consolidated destinations with an adequate mix of care and quality will be better positioned to respond to changes in the demand of tourists through the development of new products that meet these specific demands and building partnerships between service providers related to health. For hotels and hospitals, there are clear opportunities for collaboration in the creation of integrated packages aimed at this emerging niche. This indicates the potential of this sector. Secondly, and although there has been a rich and varied offer, it became apparent that there is a lack of specific sectorial organisation and relationships and the absence of intra-specific marketing initiatives that encompass the entire supply of health tourism, promoting it together. These elements are indicators that there is still no clear understanding about the sector as a different offer that requires different marketing activities.

As contributions, this paper contributes to the literature by showing the complexity of the several practices included in the conceptual umbrella of health tourism, describing them in a mature destination. The paper highlights a lack of a shared understanding of health tourism in the literature. The proposed typology addresses this gap by identifying the key services that can be included in this activity and integrating them into a transparent and structured simplified framework. A major benefit of the proposed typology is that it can help to advance research in this area, providing a consistent framework to support the academic study of the phenomenon. Another contribution of the study is its capacity to bridge the gap between theory and practice, linking the proposed framework with the real supply identified in an important mature destination, such as the Costa del Sol in Spain. With this, evidence has been provided about the existence of several actors that offer health-related services.

Relevant implications for policymakers and for managers can be drawn from the results. For policymakers, intermediate promotional tourism organisations could take some actions. By recognising the richness, diversity, and complementarity of health tourism and through joint actions of the various players in the sector, they could develop an interesting and non-seasonal tourism sector, creating a comprehensive offer of health and wellness tourism through the joint actions of diverse agents in the sector, which would also help to develop an awareness of them belonging to a specific segment. As Medina-Muñoz and Medina-Muñoz (2013) stated, the important differences in the socio-demographic characteristics of this tourist make it necessary to develop and promote specific wellness packages with a view to better satisfying the precise needs of the different market segments that could be identi?ed. Furthermore, they could promote the complementarity of this sector with other tourist activities and target specific demand for international health tourism, taking advantage of their own specialised value chain activities. For managers, they could base their marketing strategy in this sector so as to develop non-seasonal demand for their products, to improve promotion and direct sale through internet, and to search for international alliances in emerging origin countries such as Russia and Arab countries, among others.

Finally, this research has a number of limitations. Firstly, it is a study that, while developing a non-existent theoretical and conceptual framework, relies on empirical evidence that relates only to a destination in southern Spain, which may detract from the generality of the findings. Consequently, more empirical studies are needed in other developed countries (Reddy et al., 2010). Secondly, the study only considers the supply side. Conducting an empirical study on the characteristics, expectations, and tourism demands of tourists would contribute to completing the analysis of the characteristics of this sector and the conclusions. In particular, more research is needed about the available information, how patients understand the risks of care abroad, and the push and pull factors involved (Heung et al., 2011).

References

Almeida-García, F., Peláez-Fernández, M.A., Balbuena-Vázquez, A., & Cortés-Macias, R. (2016). Residents' perceptions of tourism development in Benalmádena (Spain). Tourism Management, 54(June), 259-274. [ Links ]

Bushel, R., Sheldon, P.J. (eds.) (2009). Wellness and Tourism: Mind, Body, Spirit, Place. New York: Cognizant Communication Corporation. [ Links ]

Carrera, P., & Lunt, N. (2010). A European perspective on Medical Tourism: the need for a knowledge base. International Journal of Health Services, 40(3), 469-484. [ Links ]

Carrera, P.M., & Bridges J.F.P. (2006). Globalization and healthcare: understanding health and medical tourism. Expert Review Pharmacoeconomics Outcomes Research, 6(4), 447–454. [ Links ]

Chuang, T.C., Liu, J.S., Lu, L.Y.Y., & Lee, Y. (2014). The main paths of medical tourism: From transplantation to beautification. Tourism Management, 45(December), 49-58. [ Links ]

Clarke A. (2010). Wellness and tourism: Mind, body, spirit. Annals of Tourism Research, 37(1), 276–278. [ Links ]

Connell, J. (2006). Medical tourism: Sea, sun, sand and surgery. Tourism Management, 27(6), 1093–1100. [ Links ]

Connell, J. (2013). Contemporary medical tourism: Conceptualisation, culture and commodification. Tourism Management, 34(February), 1-13. [ Links ]

Cormany, D., &Baloglu, S. (2011). Medical travel facilitator websites: An exploratory study of web page contents and services offered to the prospective medical tourist. Tourism Management, 32(4), 709-716. [ Links ]

Crooks, V.A., Kingsbury, P., Snyder, J., & Johnston, R. (2010). What is known about the patients experience of medical tourism? A scoping review. BMC Health Services Research 10(266), 1-12. [ Links ]

Denicolai, S., Cioccarelli, G., & Zucchella, A. (2010). Resource-based local development and networked core-competencies for tourism excellence. Tourism Management, 31(2), 260–266. [ Links ]

Dwyer, L, Edwards, D., Mistilis, N, Roman, C, &Scott, N. (2009). Destination and enterprise management for a tourism future. Tourism Management 30(1), 63-74. [ Links ]

Euromonitor (2014). Health and Wellness Tourism in Spain. Retrieved January, 11, 2016 from: http://www.euromonitor.com/health-and-wellness-tourism-in-spain/report [ Links ]

European Parliament (2011). Directive 2011/24/EU of the European Parliament and of the Council of 9 March 2011 on the application of patients rights in cross-border healthcare. Official Journal of the European Union. L 88/45. [ Links ]

Fernández-Morales, A., & Mayorga-Toledano, M.C. (2008). Seasonal concentration of the hotel demand in Costa del Sol: A decomposition by nationalities. Tourism Management 29(5), 940-949. [ Links ]

Fetscherin, M., & Stephano, R.M. (2016). The medical tourism index: Scale development and validation. Tourism Management, 52(February), 539-556. [ Links ]

García-Altés, A. (2005). The development of health tourism services. Annals of Tourism Research, 32(1), 262–266. [ Links ]

Goodarzi, M., Haghtalab, N., & Shamshiry, E. (2015): Wellness tourism in Sareyn, Iran: resources, planning and development, Current Issues in Tourism, DOI: 10.1080/13683500.2015.1012192 [ Links ]

Goodrich, J.N., & Goodrich, G.E. (1987). Health-care tourism – an exploratory study. Tourism Management 8(3), 217-222. [ Links ]

Hall. C.M. (2013). Medical Tourism: The Ethics, Regulation and Marketing of Health Mobility. Oxford: Routledge. [ Links ]

Han, H. (2013). The healthcare hotel: Distinctive attributes for international medical travellers. Tourism Management, 36(June), 257-268. [ Links ]

Han, H., & Hwang, J. (2013). Multi-dimensions of the perceived bene?ts in a medical hotel and their roles in international travelers decision-making process. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 35(December), 100-108.

Han, H., & Hyun, S.S. (2015). Customer retention in the medical tourism industry: Impact of quality, satisfaction, trust, and price reasonableness. Tourism Management, 46(February), 20-29. [ Links ]

Hanefeld, J., Horsfall. D., Lunt, N., Smith, R. (2013) Medical tourism: A cost or benefit to the NHS? PLoS ONE 8(10): e70406. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0070406 [ Links ]

Heung, V.C.S., Kucukusta, D., & Song, H. (2011). Medical tourism development in Hong Kong: An assessment of the barriers. Tourism Management, 32(5), 995-1005. [ Links ]

Hjalager, A.M. (2009). Innovations in travel medicine and the progress of Tourism-Selected narratives. Technovation, 29(9), 596–601. [ Links ]

Hjalager, A.M. (2010). A review of innovation research in tourism. Tourism Management, 31(1), 1–12. [ Links ]

Hjalager, A.M., & Flagestad, A. (2012). Innovations in well-being tourism in the Nordic countries, Current Issues in Tourism, 15(8), 725-740. [ Links ]

Huijbens, E. H. (2011). Developing wellness in Iceland. Theming wellness destinations the Nordic way. Scandinavian Journal of Hospitality and Tourism, 11(1), 20-41. [ Links ]

Hunter-Jones, P. (2005). Cancer and tourism. Annals of Tourism Research, 32(1), 70–92. [ Links ]

Instituto de Estudios Turísticos (2015). Balance del turismo: Resultados de la actividad turística en España. Ministerio de Industria, Energía y Turismo. [ Links ]

Kaspar, C. (1990). A new lease on life for spa and health tourism. Annals of Tourism Research, 17(2), 298–299. [ Links ]

Lee, CG. (2010). Health care and tourism: Evidence from Singapore. Tourism Management, 31(4), 486–488. [ Links ]

Lee, H.K., & Fernando, Y. (2015). The antecedents and outcomes of the medical tourism supply chain. Tourism Management, 46(February), 148-157. [ Links ]

Lunt, N., Smith, R., Exworthy, M., Green, S., Horsfall, D., & Mannion, R. (2011). Medical tourism: Treatments, markets and health system implications: A scoping review. Paris: OECD. Retrieved date from: http://www.oecd.org/dataoecd/51/11/48723982.pdf [ Links ]

Mak, A.H.N., Wong, K.K.F., & Chang, R.C.Y. (2009). Health or self-indulgence? The motivations and characteristics of spa-goers. International Journal of Tourism Research, 11(2), 185–199. [ Links ]

Málaga Health Foundation (2015). Málaga Health. Retrieved January, 11, 2016 from: http://www.malagahealth.com/ [ Links ]

Mansfeld, Y., & McIntosh, A. (2009). Wellness through Spiritual Tourism Encounters. In R. Bushell & P.J. Sheldon (eds). Wellness and tourism: Mind, body, spirit, place (pp. 177-191). New York, NY: Cognizant Communication Corporation. [ Links ]

McKercher, B. (2016). Towards a taxonomy of tourism products. Tourism Management, 54(June), 196-208. [ Links ]

Medina-Muñoz, D.R., & Medina-Muñoz, R.D. (2013) Critical issues in health and wellness tourism: an exploratory study of visitors to wellness centres on Gran Canaria. Current Issues in Tourism, 16(5), 415-435. [ Links ]

Moghimehfar, F., & Nasr-Esfahani, M.H. (2011). Decisive factors in medical tourism destination choice: A case study of Isfahan, Iran and fertility treatments. Tourism Management, 32(6), 1431-1434. [ Links ]

Mueller, H., &Kaufmann, E.L. (2001). Wellness tourism: Market analysis of a special health tourism segment and implications for the hotel industry. Journal of Vacation Marketing, 7(1), 5-17. [ Links ]

Musa, G., Thirumoorthi, T., & Doshi, D. (2012). Travel behaviour among inbound medical tourists in Kuala Lumpur. Current Issues in Tourism, 15(6), 525-543. [ Links ]

Novelli, M., Schmitz, B., & Spencer, T. (2006). Medical tourism: the importation and exportation of care in a global economy. Tourism Management, 27(6), 1141–1152. [ Links ]

Reddy, S., York, V.K., & Brannon, L.A. (2010). Travel for Treatment: Students Perspective on Medical Tourism. International Journal of Tourism Research, 12(5), 510–522. [ Links ]

Reisman, D. (2010). Health Tourism: social welfare through international trade. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing. [ Links ]

Sheldon, P.J., & Park, Y. (2009). Development of sustainable wellness destination. In R. Bushell & P.J. Sheldon (eds.). Wellness and tourism: Mind, body, spirit, place (pp.177-191). New York, NY: Cognizant Communication Corporation. [ Links ]

Singh, N. (2013). Exploring the factors influencing the travel motivations of US medical tourists. Current Issues in Tourism, 16(5), 436-454. [ Links ]

Smith, M., & Kelly, C. (2006). Wellness tourism. Tourism Recreation Research, 31(1), 1-4. [ Links ]

Smith, M.K.,&Puczkó, L. (2008). Health and wellness tourism. Burlington MA: Butterworth-Heinemann. [ Links ]

Stojanovic, M., Stojanovic, D., &Randelovic, D. (2010). New trends in participation at tourist market under conditions of global economic crisis. Tourism & Hospitality Management, Conference Proceedings, 1260-1268. [ Links ]

Strauss, A. & Corbin, J. (1990). Basics of qualitative research: Grounded theory procedures and techniques. Newbury Park, CA: Sage. [ Links ]

Turner, L. (2010). Medical tourism and the global marketplace in health services: US patients, international hospitals, and the search for affordable health care. International Journal of Health Services, 40(3), 443–467. [ Links ]

UNWTO (2013). UNWTO Tourism highlights 2013 edition. Retrieved October, 31, 2013 from: http://www.e-unwto.org (31/10/2013). [ Links ]

Vetitnev, A., Kopyirin, A., & Kiseleva, A. (2015). System dynamics modelling and forecasting health tourism demand: the case of Russian resorts, Current Issues in Tourism, DOI: 10.1080/13683500.2015.1076382 [ Links ]

Vijaya, R.M. (2010). Medical tourism: Revenue generation or international transfer of healthcare problems?. Journal of Economic Issues,44(1), 53–70. [ Links ]

Viladrich, A. & Baron-Faust, R. (2014). Medical tourism in tango paradise: The internet branding of cosmetic surgery in Argentina. Annals of Tourism Research, 45(March), 116–131. [ Links ]

Voigt, C. & Pforr. C. (eds.) (2014). Wellness tourism: A destination perspective. London: Routledge. [ Links ]

Witt, S.F. (1990). Reviving spa tourism - The AIEST congress. Tourism Management, 11(1), 80-81. [ Links ]

Ye, B.H., Qiu, H.Z., & Yuen, P.P. (2011). Motivations and experiences of Mainland Chinese medical tourists in Hong Kong. Tourism Management, 32(5), 1125-1127. [ Links ]

Yeoh, E., Othman, K., & Ahmad, H. (2013). Understanding medical tourists: Word-of-mouth and viral marketing as potent marketing tools. Tourism Management, 34(February), 196-201. [ Links ]

Yu, J.Y., & Ko, T.G. (2012). A cross-cultural study of perceptions of medical tourism among Chinese, Japanese and Korean tourists in Korea. Tourism Management, 33(1), 80-88. [ Links ]

Article history:

Submitted: 30.04.2015

Received in revised form: 11.01.2016

Accepted: 11.01.2016