Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Indicators

-

Cited by SciELO

Cited by SciELO -

Access statistics

Access statistics

Related links

-

Similars in

SciELO

Similars in

SciELO

Share

Tourism & Management Studies

Print version ISSN 2182-8458

TMStudies vol.12 no.1 Faro Mar. 2016

https://doi.org/10.18089/tms.2016.12106

TOURISM: SCIENTIFIC PAPERS

Attitude and behavior on hotel choice in function of the perception of sustainable practices

Actitud y comportamiento de consumo de hoteles en función de la percepción de prácticas sustentables

Cristóbal Fernández Robin1, Jorge Cea Valencia2, Geraldine Jamett Muñoz3, Paulina Santander Astorga4, Diego Yáñez Martínez5

1Universidad Técnica Federíco Santa María, Departamento de Industrias, Avenida España 1680, Valparaíso, Chile, cristobal. E-mail: fernandez@usm.cl

2Universidad Técnica Federíco Santa María, Departamento de Ingeniería Comercial, Avenida España 1680, Valparaíso, Chile,. E-mail: jorge.cea@usm.cl

3Universidad Técnica Federíco Santa María, Departamento de Industrias, Avenida España 1680, Valparaíso, Chile. E-mail: geraldine.jm@gmail.com

4Universidad Técnica Federíco Santa María, Departamento de Industrias, Avenida España 1680, Valparaíso, Chile,. E-mail: paulina.santander@usm.cl

5Universidad Técnica Federíco Santa María, Departamento de Industrias, Avenida España 1680, Valparaíso, Chile,. E-mail: diego.yanez@usm.cl

ABSTRACT

Chile is one of the countries with higher GPB in Latin America and important sources of incomes and employment comes from tourism. Hotels are adopting sustainable practices but it is unknown whether customers value this. This research looks to measure consumer attitude, perception and preference for hotels based on their sustainable practices. A survey was applied to 208 guests at Chilean hotels. Correspondence and exploratory factor analysis was carried. Lack of knowledge about "Sustainability, but Willingness to pay extra for Sustainable Hotels, indicate a higher level of commitment and care for environment. Three clusters were obtained: non-Committed, Influenced and Committed.

Keywords: Sustainability, consumer behavior, image, ecological hotels.

RESUMEN

Chile es uno de los países con mayor PIB en América Latina y una importante fuente de ingresos y empleo proviene del turismo. Los hoteles están adoptando prácticas sustentables pero se desconoce si los clientes valoran esto. Esta investigación busca medir la actitud de los consumidores, la percepción y la preferencia por los hoteles en función de sus prácticas sostenibles. Se aplicó una encuesta a 208 huéspedes en hoteles chilenos. Se realizaron Análisis de Correspondencia y Factorial. Existe poco conocimiento respecto al concepto Sustentabilidad, pero una mayor disposición a pagar extra por hoteles sustentables indica mayor nivel de compromiso y cuidado con el medioambiente. Se obtienen 3 perfiles: No comprometidos, Influenciables y Comprometidos.

Palabras clave: Sustentabilidad, comportamiento del consumidor, imagen, hoteles ecológicos.

1. Introduction

Tourism as an industry is a phenomenon that has a growing presence in the dynamics of the international economy. For many nations and regions, it is a principal source of income, employment and development (Guzmán & Rebolloso, 2012). Tourism contributed to around 3.5% of the Chilean GDP in 2012, as well as being an important driver of employment and entrepreneurship activity (De Vicente, 2013).

Combined with the benefits on economic development, tourism is also the main promoter of environmental, patrimonial and cultural conservation of communities. For these reasons, practices can be encouraged to inspire sustainability and transmit these values to the rest of society (Estrategia Nacional de Turismo (ENT) 2012-2020, 2013).

There is evidence that travelers perceive sustainable practices and prefer sustainable products and destinations. In fact, 81% of tourists believe that in equal conditions, they would favor the tour operator that is most environmentally responsible, 34% would be willing to pay to stay in hotels and other destinations that were friendly to the environment, 38% of travelers state that they consider sustainability criteria when choosing touristic destinations; and 73% would like to identify greener vacation spots (Estrategia Nacional de Turismo (ENT) 2012-2020, 2013).

From these results, the contrast is appreciated from the national reality. Chile is behind in Sustainable Management, as is shown by WEFs Travel and Tourism Competitiveness Report (Blanke & Chiesa, 2013). In this report, Chile ranks number 56 among 140 countries. There are considerable advances compared to the last few years, in which the government and the private sector are adopting sustainable and resource management, but the problem associated to these efforts is to find out if they are actually valued by customers of the tourism industry. It is important to study attitudes, perceptions and preferences of hotel customers with respect to sustainable practices by the hospitality sector.

According to Sachs (1986), the concept of sustainable tourism development has six dimensions: social, economic, ecologic, cultural, political and spatial. In this manner, sustainable tourism embarks development with diverse goals. Some of these goals are reducing poverty, economic development of a touristic locality, natural resource conservation, and the conservation of cultural heritage, among others (De Macedo, de Almeida Medeiros & Enders, 2012). This is evidenced on a national level through the reiterated use of the concept of sustainable tourism, which has been empowered by those who want to justify new forms of development and not necessarily use tourism as a tool for sustainability (Hunter, 1995). This situation is observed in sustainability policies that have taken the same mercantilist angle, where the emphasis is on the sustainable production and consumption, but without deeper critique (Henderson & Seth, 2006). Furthermore, there exists a lack of information on principal tourism actors because tourists and tour operators do not have the tools to recognize within the Chilean offer, destinations and businesses that are actually sustainable. Regarding the offer, the majority does not recognize the benefits of sustainable practices and is not motivated nor has the capacity to adopt them, and the market does not recognize those that do adopt them.

Based on the detection of the sustainability problem in the hotel sector and on the attitudes of the current consumers, the present research aims to measure the attitude, perception and consumption preference of returning customers of hotels on the relationship of the implementation of sustainable practices. The study centers on the analysis of how conscious people are concerning ecological problems, as well as analyzing how familiar they are with the concept of sustainability.

2. Literature Review

Due to the various debates centered on sustainability, environmental consciousness has germinated in contemporary society. As a consequence, consumers have been influenced by this debate in their buying habits (Sales & Alencar de Farias, 2013). In effect, during the last 20 years, it has been reaffirmed that that buying habits and activities are influenced by ecological and sustainability topics (Pereira & Ayrosa, 2010). However, some researchers indicate that the consumer still does not plainly comprehend the implications of his or her actions with regards to environmental impact. In this manner, the consumer faces difficulties perceiving the benefits that can be generated by a more efficient management of environmental resources (Lages & Neto, 2002).

Particularly in the tourist industry, Chou (2014) affirms that the adoption of green practices is beneficial for the hotel and tourism industry, even more, a proactive environmental strategy positively affect organizational competitiveness (Leonidou, Leonidou, Fotiadis & Aykol, 2015) and global financial performance (Fraj, Matute & Melero, 2015). However, the success of a business in the adoption of these green practices does not only depend on enterprise attitudes but also the competitive environment, as stated before by Leonidou, Leonidou, Fotiadis & Zeriti (2013) there is an effect of environmental marketing strategy on competitive advantage that is stronger in the case of intense competitive situations. Moreover, Tsai, Lin, Hwang and Huang (2014) indicate that the environmental care, especially regarding energy consumption and CO2 emissions in tourist lodging should be as much the responsibility of the industry and government as the decisions of the tourist. In this way, authors such as Manaktola and Jauhari (2007), study consumer attitudes and behaviors in relation to green practices, and they demonstrate that consumers are more apt to elect products and services with sustainable characteristics, but not willing to pay more for them. Clients choose based on the combination of attributes that best suits their needs.

In the same line, Robinot and Giannelloni (2010) observe that in overall hotel satisfaction, environmental attributes are evaluated as basic. This means that they are seen as an integral part of the services offer, and not as differentiating criteria. Contrastingly, authors such as Okada and Mais (2010) conclude that individuals are very sensitive to environmental issues and are willing to pay more for green products and services. Similarly, Trevisan (2002) shows that a large part of consumers prefers products from businesses that are committed to the environment. Also, Cardozo (2003) considers that ecological marketing contributes to the strengthening of the brand, and in consequence, the consumer tends to be influenced by that image. Even more, Saraiva and Pinto (2015) stated that social marketing enables the corporation to engage clients in the practice of positive behavior changes including environmental issues.

2.1 General Image

The global image projected by a business or company is an important factor in consumer decision-making. In the beginning of the 1990s, studies about image leaned toward consumer behavior, given that image constitutes precisely an element of management that occupies a space in the mind of the consumer, having influence on the selection of products or brands (Cruz, Nápoles, Ramos & de Ávila-Cuba, 2012).

One of the most acceptable definitions is that describes image as the conceptualization that reflects the conjunction of beliefs, ideas and impressions that people have about a product, service, destination, individual, enterprise or brand, which is processed over time (Haider & Rein, 1993). As stated by Matos, Mendes, and Pinto (2015) considering that is impossible for tourists to experience the desired holidays prior to visitation, the importance of destination image is that it influences consumers during the decision-making process and the consumption even before the experience.

2.2 Attitude towards behavior

Humans consider possible implications of their actions before carrying out a behavior (Ajzen & Fishbein, 1980). The Theory of Reasoned Action tries to understand and predict human behavior on the base of a limited number of variables, which are: attitude toward the behavior, the subjective norm, and the behavioral intention (Espí, 2005).

The Behavioral intention is the most immediate determinate of any social behavior, but only in those conditions where the conduct in question is under voluntary control, and behavioral intention is without changes. The Attitude Towards Behavior is explained by beliefs about the results of the behavior, and the evaluation of those results; showing the degree to which the behavior is positively or negatively valued. The Subjective Norm is determined by the perceived pressure from others to carry out the behavior and the motivation to capacitate the wishes of others (Espí, 2005).

In context of environmental sustainability in tourism, Juvan and Dolnicar (2014) indicate that there exists a gap between attitude and conduct, evidencing within persons a tension between their projection attitudes towards the environment, and their behavior during vacations, resulting in cognitive dissonance. This evidence gives an explanation for why it is difficult to motivate people to reduce their negative environmental impact during their vacations. Contrastingly, Chiu, Lee and Chen (2014) using a value-attitude-behavior approach, showed that responsible conduct towards the environment develops during and after the travel experience. In this sense, a higher perceived value during the experience improves responsible conduct toward the environment.

2.3 Environmental Behavior

The problem of the environment is evermore seen as a problem of perceptions and behavior (Cerda, García, Díaz & Núñez, 2007). Tikka (2000) says that the environmental crisis that many countries suffer is fundamentally due to the behavior and the thought patterns that people have. Thus, the principal solutions to environmental problems pass through an alteration or modification of human behavior (Benton & Funkhouser, 1994). There is extensive research focused on responsible ecological conduct such as actions that support the conservation and care of the environment (Axelrod & Lehman, 1993). Straughan and Roberts (1999) suggest that for an individual to participate in environmental programs, they must be convinced that their pro-environmental action will be effective in the fight against its deterioration. The question the consumer asks is why join a losing fight? (Straughan & Roberts, 1999). As a consequence, people act motivated by subjective perception that generates for them a critical environmental problem. The fact that a person behaves in a certain way or carries out a certain ecological practice does not imply that these acts are repeated in every aspect of their life. It is for this reason that people tend to act in a different way or manifest their commitment to the environment in different ways (Corral-Verdugo, 2002).

2.4 Socio-demographic Variables

Age, educational level, sex and income are the most important variables related to environmental behaviors in general. According to Dunlap and Van-Liere (1978) young people with a high level of education are those that present pro-environmental attitudes that are consistent with the realization of environmental behavior. In the other hand Amérigo and González (1996) found a low correlation between having a positive attitude towards pro-environmental behavior and age.

With respect to sex, Chen and Chai (2010) indicate that the variable does not exert a significant influence on these behaviors, although in other studies it is shown that women are significantly more likely to protect the environment than men (Amérigo & González, 2001; Stern & Dietz, 1994; Stern, Kalof, Dietz, & Guagnano, 1995). In the same line Zelezny, Chua and Aldrich (2000) conclude that there exists empirical evidence that shows that women do more pro-environmental behaviors than men. Generally, these studies that apply socio-demographic factors to pro-environmental behaviors have little concurrence and are even contradictory (Saphores, Nixon, Ogunseitan & Shapiro, 2006).

3. Methodology

This research is of exploratory nature, with the aim of tackling the issue of tourism sustainability; descriptive with respect to the generation of client profiles that manifest some type of common characteristic or property; correlational, considering aspects such as age, gender and culture in order to find any relation with consumer behavior, as well as the relationship between the principal variables of the study. These variables can be defined as: attitude towards ecological behaviors, general image, mouth to mouth and probability of paying more. The study also takes an explicative approach in the development and explanation of the existing problem, which is to find out if sustainable practices by hotel companies are valued by the attitudes, perceptions and preferences by customers. This research considers a methodological structure that is quantitative as well as qualitative, to which the research is confined.

3.1 Instrument

With respect to the instrument applied, a 17 question survey was constructed from an exploratory phase which considers both interviews with hotel owners and literature review, that focused on three specific points:

• Identifying the level of understanding of the term sustainability.

• Analyze how variables such as General image, mouth to mouth and probability of paying more, influences consumer perception and to determine if there exists any relation with the real characteristics of Ecological or Sustainable hotels.

• To know and understand socio-demographic behavior.

The survey was presented in various hotels in the Valparaiso region, and two of them opted to participate. Later, the survey was given to each traveler to answer during his or her stay. In a complementary manner, the survey was sent by e-mail to frequent hotel customers. In total, 208 surveys were validly received and accepted, and are considered the final sample.

3.2 Sample

Subjects were selected through a convenience sampling, and were defined according to the variables Age (persons over the age of 18), frequent travelers that stay in Chilean hotels and Location (principally people that stayed in the Valparaiso region, but also on a national level).

4. Results

A profile was done of the surveyed participants. 59% of the respondents were women. The most concentrated age ranged corresponded to 36% of the participants between the ages of 41 and 54, followed by 33% between the ages of 25 and 40. Most of the travelers were full-time employees (72%) followed by part-time employees (12%) and students (10%). The educational level of the participants was 67% with a university degree. 58% of those surveyed said to be traveling for pleasure, and not for work.

Perception Analysis: Sustainability

In relation to the knowledge about the concept of Sustainability, as well as the relation of this concept with the actual situation of the Ecological Hotels in Chile, it was shown that 47% of those surveyed did not even know if they had stayed in a hotel with ecological characteristics, followed by a 30% that affirmed that they had, while 23% responded that they had not stayed in a hotel with these characteristics. From this, it can be deduced that in the hotel industry, sustainable practices have taken a great force, and are carried out with higher frequency. This is a result of the saturation of this sector of the economy, that corresponds to important income and support on a productive level. On the other hand, persons do not possess a clear definition of the concept of a hotel that is 100% Ecological. Additionally, interesting to note is the degree of knowledge by those surveyed about the existence of laws or regulations regarding Sustainable Tourism, and furthermore the perceived value regarding the regulations in relationship to this topic. In this analysis, there is evidence of a large quantity of answers associated to persons that do not know if laws currently exist, and do not know if there is any differences in this aspect, represented by 39% of the sample. This demonstrates the low level of preoccupation directed at environmental issues, and above all Sustainable Tourism. At the same time, 38.5% of those surveyed did recognize differences in terms of Sustainable Tourism in Chile.

Perception Analysis and Correspondences: Attitude

Attitude was categorized under two concepts: Practices realized more frequently and Level of commitment with environmental care. Within PF the 16.8% responded with Use of energy efficient light bulbs, 15.9% responded Responsible use of lights and water, 12.5% Savings and the value use of light colors to favor illumination (11.5%). In this manner, the most recurrent practices were related to more tangible and natural attitudes. Meanwhile, practices that required a level of knowledge or commitment such as Reuse water, Recycle and separate trash or build with recycled materials were lesser realized. This suggests that the concept of sustainability is not fully rooted in these consumers. This takes even more weight upon analyzing the level of commitment with environmental care, where medium took first place with 51.4%, followed by High with 27.3% of the consumers describing their environmental commitment in this way.

Perception Analysis and Correspondences: Image

In order to determine the level of importance assigned to the different forms of measuring Image, a correspondence analysis test was carried out. The characteristics that define Image were selected as Reputation of the Hotel and 5 Star hotels are more ecological. These were the most relevant for this model, in contrast to the importance of Loyalty program. In effect, upon observing the high value placed on Hotel Reputation, it can be affirmed that this characteristic is considered very important for the concept of a positive image by these establishments.

Perception Analysis and Correspondences: Word of mouth

Word of mouth and its implication with the Intention to visit hotels seeks to explain the importance that users place on the comments that they receive regarding hotels that they occupy. To establish the level of association and representation, correspondence analysis was used. The most significant and important variable was The importance of looking for third-party opinions. Thus, it can be assumed that clients depend on this information, of comparison and of observation to be able to form a perception that finally translates in the Intention to visit and Attitude towards ecological behaviors.

Perception Analysis and Correspondences: Probability of paying more

When asked, Would you visit an ecological hotel? 98% of those surveyed manifested that they would, while 2% said they did not know, and this suggests the existence of the Intent to visit. In the same line, of those who would visit an ecological hotel, 57% affirmed that they would pay more, and 23% said that they would not. 20% answered that they did not know if they would pay more or not to stay in an ecological hotel. The results show that there is not only intent, but also a good probability of paying more for staying at ecological hotels. Of those that said that they would pay more, 40% answered that they would pay up to 15% extra for the ecological services offered; 27% said that they would pay up to 5% additional; and finally 21% of the persons surveyed said that they would pay up to 25% additional for these services. Therefore, as stated above, people feel the intention of visiting hotels with sustainable practices and consider the option of paying more for these services, this arrangement results in a level of extra payment of 15% on the values of their current preferences.

In order to establish relationships between the relevant variables to this research and to generate a final model, a comparison was done between the three possible links generated between Attitude toward green behaviors: General image of the hotel, Word of mouth and the Probability of paying more, with the goal of determining if the model is or is not consistent.

Attitude v/s Image

In relation to the proportion of inertia of the first two dimensions, this analysis resulted in 83% of the explanation of the total variance, however at a significance level of 0.129, which indicates the inexistence of a significant causal relationship between the variables. Considering the level of association or dependence of both variables on a global level, it is possible to indicate a significance level of 0.021 < 0.05, which signifies that there exists a dependency between them that moves in the direction Image ? Attitude.

Attitude v/s Word of mouth

The analysis of Attitude v/s Word of mouth showed that if the proportion of inertia is of 90% for the two first dimensions that explains the total variance, the level of significance is 0.575. This means that Word of mouth is not influential in the moment of perceiving in a positive or negative fashion a Ecological Hotel. This is finally reflected in a positive (or negative) attitude toward commitment. The significance of the global variables such as Attitude v/s Word of mouth corresponds to 0.575 > 0.05, and for this reason it is not possible to establish a level of association or relationship between them.

Attitude v/s Probability of paying more

Lastly, between Attitude and Probability of paying more, a significance level was obtained of 0.003. The proportion of inertias in the first two dimensions explains the 83.5% total variance of the model. Furthermore, within the group that is willing to pay more, 15% is the most accepted level in this sense, followed by 5% and finally 25% more. The significance found in the measurement of the variable Attitude vs. Probability of paying more as global variables is of 0.003 < 0.05, which means that it is possible to affirm the inexistence of the causal relationship between the variables. However, there does exist a level of dependence in the direction of Probability of paying more ? Attitude.

Consumer attitude and preference for ecological services achieved by the perception of the clients at the root of independent variables can be justified by the association of the latter with the variable General image of the hotel and the Probability of paying more for these services. In base of the General image, it can be inferred that through clear and defined consumer cognitive beliefs, as well as through sensations and intentions of conduct that link the idea of General image as a concept of favorable attitudes, a positive General image is achieved. With respect to the disposition to pay more, it is justified through the personal value placed on the environment and the landscape, which indicates a better attitude means a better probability of paying more.

Factor Analysis

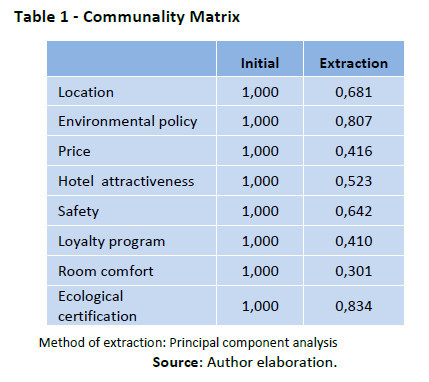

With the objective of determining the number of optimum values to establish influential relationships in terms of perceptions and preferences of the possible consumer clusters of hotel services, a factor analysis is carried out considering the importance of the following exogenous variables: Location, Environmental policy, Price, Hotel attractiveness, Safety, Loyalty program, Room comfort and Ecological certification. Table 1 shows the Communality Matrix where it can be seen that variables Room comfort, Loyalty program and Price have low communality.

Then a second factorial analysis took into account only the 5 variables with the highest communality, and these were Location, Environmental policy, Hotel attractiveness, Safety and Ecological certification. The measures of appropriateness of Factor Analysis are: Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin measure of sampling adequacy of .632 and Bartlett's test of sphericity with a level of significance of .00. Factor 1 contains the variables Location, Hotel attractiveness and Safety and explains 39.688% of the variance. Meanwhile Factor 2 composed of Environmental policy and Ecological certification explains 35.481% of the variance.

The determination of clusters is then based on the following variables: Location, Environmental policy, Hotel attractiveness, Safety and Ecological certification.

Cluster analysis

Using K-Means analysis, the data was grouped through the present distances between them with respect to the five variables mentioned earlier. Later, an iteration process was initiated with two clusters to finally conclude on four. The characterization of the clusters does not depend on any mean of the socio-demographic variables, and the ideal level of significance stands out. A possible characterization can be distinguished in the relationships shown by the data in each cluster:

Cluster 1: The Non-Committed receives this denomination given that it groups persons that give a high importance to the presence of subjective-type attributes such as the Location, Hotel attractiveness, and Safety. For these consumers, it is important that the hotel in which they are staying is in a good or strategic location that favors the activities that they take part in during their stay, whether it is for business or pleasure. These consumers also highly value the attractiveness of the hotel, which can be reflected in a certain status that the consumer wants to find, as it is synonymous with comfort. These consumers also place a very high value on security and safety, and this can be an inflection point on their intention to visit. Contrarily, these consumers do not fit with the profile of committed consumers with the environment, giving low priority to characteristics such as Environmental Policy and Ecological certification.

Cluster 2: The Influenced. They receive this denomination and characterization because in this group the consumer gives a medium importance to the presence of subjective-type attributes such as Location, Hotel attractiveness and Safety. In this way, the persons in this group can be indecisive, given that the partially comply with the profile of the committed consumer with the environment, and the can be more informed and consider the necessity to do something extra to contribute to the care of the environment. However, until the moment, it is not completely relevant to them.

Cluster 3: The Committed. They receive this denomination because they unite the important characteristics to be considered as the most committed group with the care of the environment and with sustainable practices. The clients of this cluster are characterized by their consideration of a hotel that has a good location, but also attractive and with good security measures. Additionally, the hotel must comply with all of the subjective characteristics as well as demanding a clear Environmental policy that must be communicated to the clients and an Ecological certification that reflects good practices and strategies followed by the hotel chain.

6. Discussion and Conclusions

The present study gives evidence for the lack of clarity that consumers have regarding the definition of Sustainability and its implications. The results indicate that the consumer does not consider it necessary to inform him or herself about the ecological quality of a hotel before visiting it, nor about the presence of measures that certify the realization of sustainable practices in the hotels they visit. It was discovered that sustainable practices that consumers carry out more frequently are related to tangible attitudes, while those that require a higher level of knowledge and commitment are lesser realized. This coincides with the study by Miller, Rathouse, Scarles, Holmes, and Tribe (2010) that says that consumers identify tangible elements such as those with higher impact on tourism: there is much confusion around issues related to sustainability. This result is concurrent with previous studies (Becken, 2007; Gossling, Bredburg, Randow, Sandstrom & Svensson, 2006), who all identify the low level of association between the general comprehension about the environment and possible impacts on tourism.

Recent incorporation of topic associated to sustainability and care for the environment to the countrys agenda is evidenced by the lag and the disadvantaged position facing other societies. In this sense, the role that organizations play is fundamental; deliberation, dialogue, systematic learning through reflection, evaluation and feedback have converted into the most significant attributes of good practices by organizations that promote sustainability (Berkes, 2010; Cundill, 2010; Cundill & Rodela, 2012). It is for that reason that the promotion of social learning appears to be the most indicated practice to approach issues of sustainability in the community. In this model, the government, as an educator and auditor, business owners and consumers play the part as relevant actors. This coincides, in part with the results of the research by Miller et al. (2010) that identifies that consumers attribute to the government a higher responsibility in sustainable tourism issues.

Results indicate that the reputation of hotels is relevant and can positively influence in the moment of generating an attitude and a preference towards adopting a consciousness about practices that favor the environment. Additionally, the search for third-party opinions appears a determining factor. Halpern, Bates, Mulgan, Aldridge, Beales and Heathfield (2004) states that the co-production of solutions and more frequent contact with support networks increase the confidence of the message, and this has an empowering and reinforcing effect on the perceived behavior of individuals. Within tourism, a better empowerment of tourists could serve to create new norms about the way in which different industry activities are carried out and marketed.

To inform themselves about the related hotels and services, consumers prefer online systems that permit them a better level of information, comparison and opinions, which help to generate an image of the hotel. This situation coincides with the results of the research of Lepp, Gibson and Lane (2011), that concludes that the website of a tourist destination can be a crucial element in image generation. However, the results of the present research indicate that there is not a fixed conduct that determines the selection process of sustainable hotels, principally because of the fact that in Chile there is not a comparison parameter that permits the investigation of behavior patterns of clients that visit sustainable hotels.

Socio-demographic variables affirm that age presents a higher moderating effect; in fact, clients within 25-40 years are those that manifest higher intention to visit hotels with sustainable practices. Thereby, this research permitted the identification of three clusters that indicated characteristic profiles associated to clients of these types of services. The existence of a client that is committed ecologically, denominated Committed, which values above all else the presence of an established environmental policy and an ecological certification, as well as the presence of subjective values corresponding to Location, Attractiveness of the hotel, and Security. The two remaining groups do not fit with the profile of the objective client: the so-called Non-committed and the Influenced.

References

Ajzen, I., & Fishbein, M. (1980). Understanding attitudes and predicting social behavior. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall. [ Links ]

Amérigo, M., & González, A. (1996). Preocupación medioambiental en una población escolar. Revista de Psicología Social Aplicada, 6(1), 75-92. [ Links ]

Amérigo, M., & González, A. (2001). Los valores y las creencias medioambientales en relación con las decisiones sobre dilemas ecológicos. Estudios de Psicología, 22(1), 65-73. [ Links ]

Axelrod, L. J., & Lehman, D. R. (1993). Responding to environmental concerns: What factors guide individual action? Journal of environmental psychology, 13(2), 149-159. [ Links ]

Becken, S. (2007). Tourists perception of international air travels impact on the global climate and potential climate change policies. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 15(4), 351–368. [ Links ]

Benton Jr, R. & Funkhouser, G. R. (1994). Environmental attitudes and knowledge: an international comparison among business students. Journal of Managerial Issues, 6(3), 366-381. [ Links ]

Berkes, F. (2010). Devolution of environment and resources governance: trends and future. Environmental Conservation, 37(04), 489-500. [ Links ]

Blanke, J., & Chiesa, T. (2013). The travel & tourism competitiveness report 2013. In The World Economic Forum. [ Links ]

Cardozo, J. S. (2003). Geração de valor e marketing social. Valor Econômico, 4, 712. [ Links ]

Cerda, A., García, L., Díaz, M., & Núñez, C. (2007). Perfil y conducta ambiental de los estudiantes de la Universidad de Talca, Chile. Panorama Socioeconómico, 25(35), 148-159. [ Links ]

Chen, T. B. & Chai, L. T. (2010). Attitude towards the environment and green products: Consumers perspective. Management Science and Engineering, 4(2), 27-39. [ Links ]

Chiu, Y. T. H., Lee, W. I., & Chen, T. H. (2014). Environmentally responsible behavior in ecotourism: Antecedents and implications. Tourism management, 40, 321-329. [ Links ]

Chou, C. J. (2014). Hotels' environmental policies and employee personal environmental beliefs: Interactions and outcomes. Tourism Management, 40, 436-446. [ Links ]

Corral-Verdugo, V. (2002). A structural model of proenvironmental competency. Environment and behavior, 34(4), 531-549. [ Links ]

Cruz, E. C., Nápoles, Y. N., Ramos, E. E. C., & de Ávila-Cuba, C. (2012). Imagen percibida-satisfacción. La analogía para complacer al cliente. Estudios y perspectivas en turismo, 21, 706-726. [ Links ]

Cundill, G. (2010). Monitoring social learning processes in adaptive comanagement: three case studies from South Africa. Ecology and Society, 15(3), 28. [ Links ]

Cundill, G., & Rodela, R. (2012). A review of assertions about the processes and outcomes of social learning in natural resource management. Journal of environmental management, 113, 7-14. [ Links ]

De Macedo, R. F., de Almeida Medeiros, V. C. F., & Enders, W. T. (2012). Factores humanos que influyen en el éxito o fracaso del turismo ambientalmente sustentable. Percepción de los gestores públicos en el Polo Costa das Dunas de Rio Grande do Norte-Brasil. Estudios y Perspectivas en Turismo, 21(6), 1433-1455. [ Links ]

De Vicente, F. (2013). Ministro De Vicente: Queremos transformar a Chile en una potencia turística. Retrieved March 30, 2014, from http://informa.gob.cl/comunicados-archivo/ministro-de-vicente-queremos-transformar-a-chile-en-una-potencia-turistica/. [ Links ]

Dunlap, R. E., & Van Liere, K. D. (1978). The new environmental paradigm. The journal of environmental education, 9(4), 10-19. [ Links ]

Espí, V. (2005). Variables conductuales y psicológicas relacionadas con la intención y la conducta del ejercicio. Doctoral dissertation. Universidad de Valencia, Spain. [ Links ]

Estrategia Nacional de Turismo 2012-2020 (2013). Ministerio de Economía, Fomento y Turismo. Gobierno de Chile. [ Links ]

Fraj, E., Matute, J., & Melero, I. (2015). Environmental strategies and organizational competitiveness in the hotel industry: The role of learning and innovation as determinants of environmental success. Tourism Management, 46, 30-42. [ Links ]

Gossling, S., Bredburg, M., Randow, A., Sandstrom, E., & Svensson, P. (2006). Tourist perceptions of climate change: A study of international tourists in Zanzibar. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 9(4-5), 419–433. [ Links ]

Guzmán, M., & Rebolloso, F. (2012). Turismo y sustentabilidad: paradigma de desarrollo entre lo tradicional y lo alternativo. Gestión y estrategia, (41), 71-86. [ Links ]

Haider, D. H., & Rein, I. (1993). Marketing places: Attracting investment, industry, and tourism to cities, states, and nations. New York: MaxwellMacmillan International. [ Links ]

Halpern, D., Bates, C., Mulgan, G., Aldridge, S., Beales, G., & Heathfield, A. (2004). Personal responsibility and changing behaviour: The state of knowledge and its implications for public policy. London: Cabinet Office, Prime Ministers Strategy Unit. [ Links ]

Henderson, H. & Seth, S. (2006). Ethical markets: Growing the green economy. Vermont: Chelsea Green Publishing. [ Links ]

Hunter, C. J. (1995). On the need to re-conceptualize sustainable tourism development. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 3(3), 155-165. [ Links ]

Juvan, E., & Dolnicar, S. (2014). The attitude–behaviour gap in sustainable tourism. Annals of Tourism Research, 48, 76-95. [ Links ]

Lages, N. & Neto, A. V. (2002). Mensurando a consciência ecológica do consumidor: um estudo realizado na cidade de porto alegre. In Anais Encontro da Anpad, Salvador, 26:1-16. [ Links ]

Leonidou, L. C., Leonidou, C. N., Fotiadis, T. A., & Zeriti, A. (2013). Resources and capabilities as drivers of hotel environmental marketing strategy: Implications for competitive advantage and performance. Tourism Management, 35, 94-110. [ Links ]

Leonidou, L. C., Leonidou, C. N., Fotiadis, T. A., & Aykol, B. (2015). Dynamic capabilities driving an eco-based advantage and performance in global hotel chains: The moderating effect of international strategy. Tourism Management, 50, 268-280. [ Links ]

Lepp, A., Gibson, H., & Lane, C. (2011). Image and perceived risk: A study of Uganda and its official tourism website. Tourism Management, 32(3), 675-684. [ Links ]

Manaktola, K., & Jauhari, V. (2007). Exploring consumer attitude and behavior towards green practices in the lodging industry in India. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 19(5), 364-377. [ Links ]

Matos, N., Mendes, J., & Pinto, P. (2015). The role of imagery and experiences in the construction of a tourism destination image. Journal of Spatial and Organizational Dynamics, 3(2), 65-84. [ Links ]

Miller, G., Rathouse, K., Scarles, C., Holmes, K., & Tribe, J. (2010). Public understanding of sustainable tourism. Annals of Tourism Research, 37(3), 627-645. [ Links ]

Okada, E. M., & Mais, E. L. (2010). Framing the "green" alternative for environmentally conscious consumers. Sustainability Accounting, Management and Policy Journal, 1(2), 222-234. [ Links ]

Pereira, S., & Ayrosa, E. (2010). Atitudes relativas a marcas e argumentos ecológicos: um estudo experimental. Revista de Gestão Organizacional, 2(2), 1-12. [ Links ]

Robinot, E., & Giannelloni, J. L. (2010). Do hotels "green" attributes contribute to customer satisfaction? The Journal of Services Marketing, 24(2), 157-169. [ Links ]

Sachs, I. (1986). Ecodesenvolvimento: crescer sem destruir. In Ecodesenvolvimento: crescer sem destruir. Vértice. [ Links ]

Sales, F., & Alencar de Farias, S. (2013). Identidad de los destinos turísticos en los sitios web: Su relación con las evaluaciones y actitudes del consumidor. Estudios Y Perspectivas En Turismo, 22(5), 893-907. [ Links ]

Saphores, J. D. M., Nixon, H., Ogunseitan, O. A., & Shapiro, A. A. (2006). Household willingness to recycle electronic waste an application to California. Environment and Behavior, 38(2), 183-208. [ Links ]

Saraiva, A., & Pinto, P. (2015). Placing social marketing in the practice of corporate social responsibility: Focusing on environmental issues. Journal of Spatial and Organizational Dynamics, 3(3), 227-238. [ Links ]

Stern, P. C., & Dietz, T. (1994). The value basis of environmental concern. Journal of social issues, 50(3), 65-84. [ Links ]

Stern, P. C., Kalof, L., Dietz, T., & Guagnano, G. A. (1995). Values, beliefs, and proenvironmental action: attitude formation toward emergent attitude objects. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 25(18), 1611-1636. [ Links ]

Straughan, R. & Robert, J. (1999). Environmental segmentation alternatives: a look at green consumer behavior in the new millennium. Journal of Consumer Marketing, 16(6), 558-575. [ Links ]

Tikka, P.M. (2000). Effects of educational background on students attitudes, activity levels, and knowledge. The Journal of Environmental Education, 31(3), 12-19. [ Links ]

Trevisan, F. A. (2002). Balanço social como instrumento de marketing. RAE-eletrônica, 1(2), 1-12. [ Links ]

Tsai, K. T., Lin, T. P., Hwang, R. L., & Huang, Y. J. (2014). Carbon dioxide emissions generated by energy consumption of hotels and homestay facilities in Taiwan. Tourism Management, 42, 13-21. [ Links ]

Zelezny, L. C., Chua, P. P., & Aldrich, C. (2000). New ways of thinking about environmentalism: Elaborating on gender differences in environmentalism. Journal of Social issues, 56(3), 443-457. [ Links ]

Article history:

Submitted: 31.03.2015

Received in revised form: 06.01.2016

Accepted: 19.01.2016