Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Acessos

Acessos

Links relacionados

-

Similares em

SciELO

Similares em

SciELO

Compartilhar

Tourism & Management Studies

versão impressa ISSN 2182-8458

TMStudies vol.11 no.1 Faro jan. 2015

TOURISM – RESEARCH PAPERS

Tourism research: A systematic review of knowledge and cross cultural evaluation of doctoral theses

Investigação em Turismo: uma revisão sistemática da literature e avaliação transcultural de teses de doutoramento

Cristiana Oliveira1; Adriaan De Man2; Sergio Guerreiro3

1Universidade Europeia, School of Tourism, Sports & Hospitality, UNIDE – BRU ISCTE, Estrada da Correia 53, 1500-210 Lisbon, Portugal, cristiana.oliveira@europeia.pt

2Universidade Europeia, School of Tourism, Sports & Hospitality, IEM-UNL, Estrada da Correia 53, 1500-210 Lisbon, Portugal, adriaan.de.man@europeia.pt

3Universidade Europeia, School of Tourism, Sports & Hospitality, CEG-UL - TERRITUR, Estrada da Correia 53, 1500-210 Lisbon, Portugal, sergio.guerreiro@europeia.pt

ABSTRACT

Tourism studies have become distinct in the past years due to the emergence of specialized journals, but also of universities, departments and research centers offering PhD programs, fundamental for the development of research and for the foundation of new scholars across the world.

The purpose of this paper is to assess the recent development of knowledge by evaluating the nature of the dominant scientific fields and their core research subjects, through a cross cultural approach considering the UK, Spain, France, Germany, Italy and Portugal. This study addresses this gap and provides an original contribution through the analysis of the doctoral theses published between the years 2000-2013 in these countries. The selected research methodology is based on content analysis of keywords and concepts. Recommendations are offered for future developments.

Keywords: Tourism, cross-national research, research subjects, doctoral theses.

RESUMO

Os Estudos de Turismo tornaram-se distintos nos últimos anos, devido ao surgimento de revistas especializadas, mas também à oferta de programas de doutoramento em universidades, departamentos e centros de investigação, fundamentais para o desenvolvimento da investigação e para o surgimento de novos estudiosos em todo o mundo.

O objetivo deste trabalho é avaliar o desenvolvimento recente do conhecimento através da avaliação da natureza das áreas científicas dominantes e dos seus temas de pesquisa nucleares, através de uma abordagem transcultural, considerando-se o Reino Unido, Espanha, França, Alemanha, Itália e Portugal. Este estudo aborda esta lacuna e proporciona um contributo original, através da análise das teses de doutoramento publicadas entre os anos de 2000-2013 nesses países. A metodologia de investigação adotada é baseada na análise de conteúdo de palavras-chave e conceitos. São feitas recomendações para futuros desenvolvimentos.

Palavras-chave: Turismo, investigação transnacional, temas de investigação, teses de doutoramento.

1. Introduction

Tourism as a research field has come a long way since its first developments in the mid 1930s. It is significant that knowledge about tourism has emerged primarily from official reports, government directives and sources alike (Tribe 1997; Tribe & Airey, 2007). A striking example is the fact that the European Commission has only quite recently recognized the full importance of tourism in Europe's economy, and has been heavily involved in this sector only since the 80s, in partnership with various countries and institutions. Tourism has since gained a strategic relevance, as an industry as well as an academic research field (Xiao, 2006).

During the 1960s, scientific production began to gain momentum, first through geography, economics of tourism developing in the 70s (Costa, 2013). It became closely attached to a vast multiplicity of disciplines, and new angles from fields formerly unfamiliar with tourism are providing new depths, challenges and results (Cooper, 2014), adding value to tourism and hospitality. Economics, anthropology and geography are prevailing, yet even a quick glance at any academic journal database shows more recent inputs from recreation, psychology, philosophy, history, and an array of other fields. There is furthermore an increasing relevance of relationships between tourism, environment and territory and the need to discuss, measure and evaluate the impacts of tourism activities (Martins & Albuquerque, 2013).

In order to legitimate further creation of knowledge in tourism, it might be significant to consider scientific production in itself – in other words, to study theses from university doctoral programs for European countries. This has been done for the North American reality, providing original contributions, not all in the form of a final dissertation but often as by-products of doctoral research – an interesting volume (Chon 2013) contained book chapters by graduate students and their advisors, following precisely a new scenario of growth in graduate studies in hospitality and tourism.

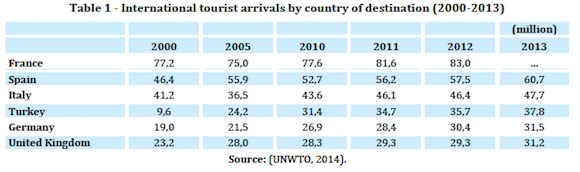

Regarding the countries examined below, the first of the selection criteria was their weight in terms of the ranking of international tourist arrivals. In fact, France, Spain, Italy, Germany and United Kingdom have been top European destinations for a long time, sharing a set of common challenges that will ultimately have an impact in terms of research. The increasing competition from Eastern countries is one of these, as can be seen from the recent entry of Turkey in this group (Table 1). At a different scale, Portugal also shares such challenges, and needs to compare its research with that of its European partners. On the other hand, apart from important tourism destinations, these countries are major, worldwide outbound markets, and of strategic interest to Portugal. In 2013, these five countries were among its top ten markets (Turismo de Portugal, 2014).

The aim is to reach a thorough analysis of theses defended between 2000 and 2013, in a European environment, according to literature on the dominant scientific fields, the core research subjects, and on how research has been conducted in different countries. Content analysis of key words, as well as concepts in the PhD thesis is deemed adequate to the selected research methodology (Smith, 2010).

2. Literature review

2.1 Tourism knowledge and previous studies

According to Airey & Tribe (2008), the origins of the sociology of European Tourism might be traced back to the 1930s. Norval (1936), Ogilvie (1933), Brunner (1945) and Pimlott (1947) are among the first contributors, counting on immediate precursors, such as Rae (1891). Early definitions of tourism do relate to traveling in pre-modernity, yet the combination of statistical needs and the concept of free time point especially to the early 20th century (Vukonic, 2012) for attempts of theoretical understanding of tourism. But when seriously addressing modern tourism studies one has necessarily to turn to economic, demographic or business history (Walton 2009), probably even at early modern level (Verhoeven, 2013). As stated above, many scientific disciplines have largely contributed to the expansion of the knowledge in this field, hence it is common to find tourism scholars with other scientific backgrounds using them in order to explain the tourism phenomenon (Dann & Parrinello, 2009). The sheer definition of a tourism system includes an increasingly broader vision, including the human, geographic and economic elements (Liper, 1981; Gartner, 1996). Works from Jafar Jafari and J.R. Brent Ritchie (1981) are particularly relevant since they provide evidence that tourism theories emerges from a variety of disciplinary backgrounds, without however forming a new science (Salgado & Costa, 2011). The term tourismology is sometimes used (e.g. Cunha, 2006) as a facilitating expression for a fragmented reality that does not lend itself to a holistic understanding (Echtner & Jamal, 1997; Horner, 2000). Affirming that tourism has only recently gained the status of a scientific subject, but not that of a discipline (Tribe, 2004) has become something of a truism for some years now.

Jafari (1990) defined a systematization of tourism, through a set of four seminal platforms, to which other dimensions have been added (Macbeth 2005, Moscardo 2008). Still tourism studies remain heavily reactive to academic myths. Even the fundamental premise of being the worlds largest industry is very much debatable. Another persistent myth is that of tourism and leisure studies lacking theory; it has been said that tourism suffers in fact from too many theories (McKercher & Prideaux, 2014). Even so, insufficient knowledge on tourism resulting from a comparatively late research development is a fact, yet it did not prevent the activity to grow significantly, being today one of the largest economic activities worldwide, with more than 1,087 million tourist arrivals and international tourism receipts of US$ 1,159 billion, growing around 5% in real terms in 2013 (UNWTO, 2014a). It is only natural that many university programs, scientific journals, research conferences, international associations and specialized newspapers now have emerged. They started at a fairly low rate The first specialized journal - Tourism Review – was established in 1945 and other international research journals appear only from the 60s onwards, as is the case with the Journal of Travel Research in 1962, Annals of Tourism Research in 1973, and Tourism Management in 1980. Nowadays, academic leaders in tourism studies can even be ranked according to their publication index (Zhao & Ritchie, 2007).

The same idea of tourism development in academia was advanced some three decades ago, when a study led to 157 theses defended in the United States, between 1951 and 1987 (Jafari & Aaser, 1998). The general findings were, first of all, a general growth in number over time, some ascendancy of economics over other subjects – although anthropology, geography and recreation were very close to becoming second. It was noted that, contrary to expectations, business administration and sociology were not particularly trendy fields for writing a doctoral thesis in tourism studies. These observations have been refined in more recent years; the general scenario seems to have shifted mainly in terms of a major prominence of recreation, and of a larger fragmentation of other academic areas, such as environmental studies, history, psychology or literature (Meyer-Arendt & Justice, 2002). More recently, the generic framework continues to register a proportional decline in economics as a primal research discipline (Weiler, Moyle, & McLennan, 2012). This significant increase in scientific production in the area of tourism is particularly relevant in countries where tourism plays a strategic role as, for example, Portugal and Spain, where historical cycles are comparable as far as tourism research is concerned (Almeida Garcia 2014). Sánchez (2013) identified more than 1,079 articles on tourism published there between 2001 and 2012, and they grew annually in number at a rate of about 10 times, with a third of research topics being registered in the broad category of hospitality, leisure, sport & tourism – that is, before management studies.

Another trend, perhaps not linearly translatable to a European continental reality, is the very close link between theory and practice. European tradition used to form students, at bachelor or graduate level, to assume very specific, entry-level duties in the tourism and hospitality sector (Formica, 1996), but this pattern, focusing the acquisition of technical abilities, lacked the research dimension subjacent to doctoral education. In the UK and US there are, for instance, many interesting examples of PhD candidates with a solid professional background in the tourism industry (Baum, 1998), whose personal experience often gives a practical dimension to what would elsewise be a strict academic environment (e.g. Pike, 2003). It has indeed become crucial for tourism education to converge with practice, and in line with national policies on the industry (Amoah & Baum, 1997). As a partial result, the focus on cross-curricular skills has become a concern in study plans and internal evaluations (including comparative quality control; Teng, Horng, & Baum, 2013), as shown by a recent Spanish study (Rodríguez-Antón, Alonso-Almeida, Rubio Andrada & Celemín Pedroche, 2013).

This leads to a fundamental division between business-oriented approaches to tourism studies, as opposed to other advances, which are not directly linked to the commercial aspects of a given subject. This epistemological question has been suggestively called the indiscipline of tourism (Tribe, 1997). The relationships between higher education and the industry are sometimes taken as self-evident but need substantiation (Peacock, Ladkin, 2002). In any case, there is much to gain for the university in potentiating this diversity in the form of doctoral research. There has also been space for defending more specialized education formats, not only divided in generic or functional, but also adding a product-based, thematic track (Dale, Robinson, 2001) that has the advantage of linking with case studies and stakeholders active in the industry. When thinking of the future of tourism studies, there is currently a growing emphasis on matters such as pluralism, experiential learning critical thinking, complexity, value of arts and sciences (Sheldon, Fesenmaier, Woeber, Cooper & Antonioli, 2008), which is reflecting directly on the steady growth of tourism and hospitality tertiary programs, with a tendency to mature even more (Rappole, 2000).

3. Methodology: evidences from the tourism academy

Six online databases that catalogue and inventory doctoral research were explored, and countries were selected on the basis that they are important both as tourism destinations (by International Tourist Arrivals relevance) as well as central in the tourism research and scholarship scene (by number of completed PhD). This method was used as to identify the search terms from the titles, abstracts and keywords of theses. In order to ensure a correct selection of the patterns and trends of disciplines and subjects, a list of was used according to previous studies on this topic as reference: Hall & Pedrazzini (1989), Meyer-Arndt & Justice (2002), Weiler & Laing, (2008), Chen & Wu (2005). The resulting subjects are the following: hotel, hospitality, leisure, tourism, tourist, travel, tour, recreation, holiday, vacation, guide, trip and heritage, education, tourism management, and environment (Weiler, Moyle, & McLeannan, 2012).

Data was collected from the Portuguese Repositório Científico de Acesso Aberto de Portugal (RCAAP), the Spanish Base de Datos de Teses Doctorales (TESEO), the French Moteur de Recherche des Thèses de Doctorat Françaises (THESES.FR), the British Electronic Theses Online Service (ETHOS), the Deutsche Nationalbibliothek Online-Dissertationen (DissOnline.de), as well as the Italian Portale per la Letteratura scientifica Elettronica Italiana su Archivi aperti e Depositi Istituzionali (PLEIADI). Data gathering through other means, such as visits to public libraries, was not considered at this point. Following validation, an Excel database was created in which the country of origin, discipline and research, and year of completion were inserted for coding (ABES, 2011; DissOnline, 2012; Ministerio de Educación, Cultura y Deporte, 2013; PLEIADI, 2004; RCAAP, 2008; The British Library Board, 2008).

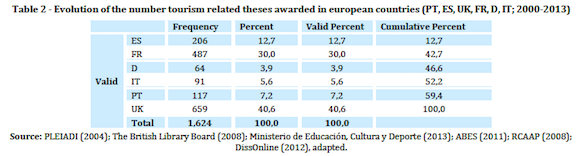

A total of 6,189 doctoral dissertations were considered; cases with missing data, such as title, abstract or award date, were withdrawn, whilst other were excluded based on the fact that abstract or title content was not tourism related. Subsequently, only 1,624 theses were effectively considered valid.

As a liability test this research incorporated two independent researchers performing the coding review of every dissertation included in the study. The role of these individuals was to confirm or not the evaluation of the dissertation coding, regarding the scientific field and the subject, but also the selection criteria. In accordance with Adams and White (1994), the assessment result was over 90% of the abstracts considering the leading researchers. The remaining were subject to a discussion between the two independent researchers until some level of compromise was accomplished (Weiler, Moyle, & McLennan, 2012). However there was a list of over 10% of theses that were considered difficult to assess and hence not included in the study.

4. Results

The results of this investigation will be presented and discussed separately, taking into account the previously defined objectives.

As shown by table 2, the majority of doctoral dissertations were undertaken in the United Kingdom, followed by France. Portugal produced a total of 117 theses (8%) and Spain with almost twice as much as PT. Italy and Germany appear to count for a lesser number. These results are clearly related to the fact that Spain and Portugal have recently started to develop tourism-related research (Sánchez, 2013). The results are not aligned with the importance of these regions in terms of inbound tourism, where France assumes the lead followed by Spain, Italy Germany and UK (UNWTO, 2014).

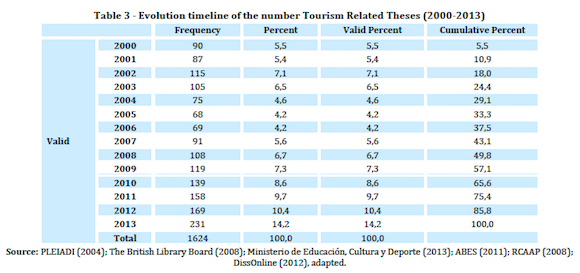

It is also of major importance to analyze the timeline patterns between 2000 and 2013. For instance, according to table 3, a moderate growth of some extent has been registered between the years 2000 and 2003, followed by a decrease until 2008. From this year onwards, the growth in doctoral-level tourism research in all countries considered has been exponential. This trend seems to be consistent until 2013, reaching over 100 doctoral theses completed each year.

These results suggest that until 2004 there may be an important shortage of up-and-coming doctoral students – and probably also of academic supply. Moreover, these numbers point at a growing demand for tourism-focused doctoral research from that year on.

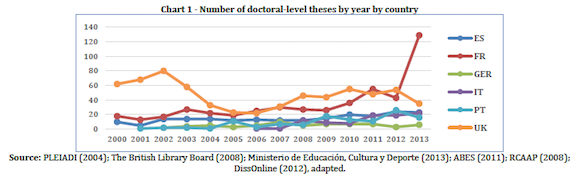

Looking closely at the distribution by year and by country, no clear pattern emerges, apart from a consistent growth in the number of theses written between 2007 and 2013. France has registered a peak in 2013, which can be explained by the focus on sharing online theses in this country (Chart 1).

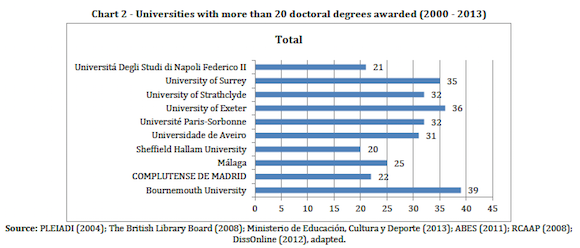

During this period of time, a total of 343 universities have been found to develop tourism-focused doctoral theses in the four countries analysed in this study. 37 universities were selected, as they registered over than 10 doctoral tourism theses. The top ten identified in this paper are Bournemouth University with 39 theses (UK), University of Exeter with 36 (UK), University of Surrey with 35 (UK), University of Strathclyde with 32 (UK), Université Paris-Sorbonne counting 32 (FR), Universidade de Aveiro with 31 (PT), University of Malaga with 25 (ES), Universidad Complutense de Madrid with 22(ES), Sheffield Hallam University with 20 (UK) and Universitá Degli Studi di Napoli Frederico II with 21 (IT).

Overall, five universities were identified as providing the leading doctoral-level tourism research output. As illustrated in chart 2, the UK clearly stands out, with 4 universities among the first 5. This fact may be partly explained by the considered period itself, meaning that in its earlier phases, tourism research was particularly active in the UK. In addition, Portugal and Spain are ranked second in the top ten and France contributes with one university to this count. So it is remarkable that the top 10 was responsible for 85% of the output, and that it is does not follow the general university rankings in terms of publication. Furthermore, it was found that 112 universities produced one single tourism related thesis over this timeline. This might be explained by the fact that some universities may be starting to be recognized by their tourism research output, while other have not established a strategic focus in this field.

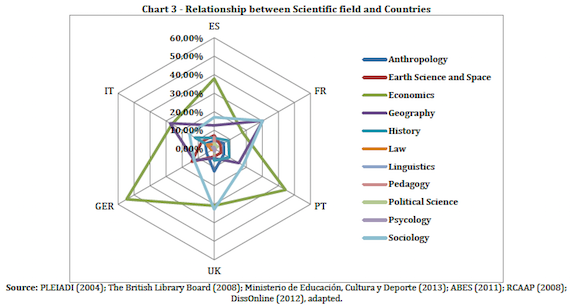

According to table 4, it is not at all surprising that the three more relevant disciplines overlapping tourism-focussed doctoral research are economics, sociology, geography and anthropology.

Chart 3 reveals some interesting cross-national differences. While the United Kingdom reveals a predominance of sociology, economics and anthropology, in France the second most popular discipline is geography, which in Italy ranks first, ex aequo with economics. In Germany and Spain and Portugal, economics has a definite preponderance. In the two latter this might be somehow linked to the need to demonstrate the economic importance of the sector as a way to achieve greater political recognition, which has been a relevant topic of the tourism stakeholders agenda in the latest years.

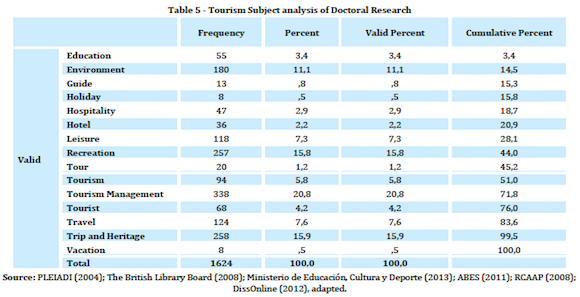

Revised literature confirms the deep-rooted tradition of economics, geography and sociology predominance in European tourism-related research (Vukonic, 2012). These results might become especially interesting for adequately seeking funding opportunities, and to identify disregarded research angles and multidisciplinary approaches (Weiler, Moyle, & McLeannan, 2012), in the area of tourism law, political frameworks, new technologies, and so forth. Table 5 shows the tourism subject analysis of doctoral thesis.

These results might be explained by the appeal of urban and regional planning, sustainability, heritage and tourist-related issues present in the strategic touristic plans of the studied countries over the last decade (OECD, 2014).

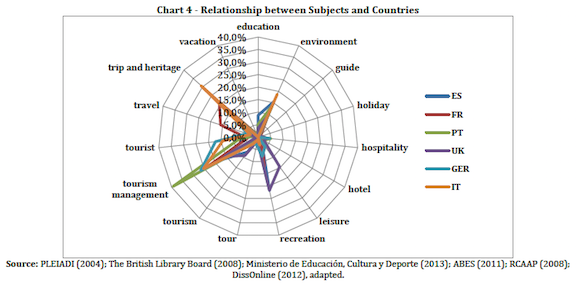

The links between countries and core research subjects (chart 4) show a preference for recreation, tourism management and leisure, in the UK. Tourism Management comes first in France, Portugal and Germany too, and second in Spain and Italy. Again the results seem to reinforce the idea that all countries share some common core subjects. Apart from the natural primacy of economics, this pattern could be justified by the fact that organizations such as UNWTO, UNESCO and OECD have given a special attention to tourism and projects associated to sustainable development and heritage. Themes like recreation seem to establish a mutual interest for countries such as United Kingdom and Spain. This could be particularly interesting for the design of future research in this area but also in the top ranked subjects. Hotel, hospitality, tours, guides, vacation or education appear as less popular and hence are a great prospect for further research. This trend is reinforced by other case studies (Meyer-Arendt & Justice, 2002).

5. Conclusion

As mentioned above, the purpose of this paper is to assess the recent development of knowledge in the field of doctoral research in Tourism and to evaluate both its nature and structure. To do so, evolutions of the scientific fields and their core research subjects were analyzed.

It can also provide relevant indicators that might be used as decision-making tools for the assessment and state of the art in tourism based research (Cooper, 2014). The study also delivers insights that can lead to strategic choices by decision-makers at a research level, for instance regarding the introduction of new subjects in PhD programs.

There is a clear and growing interest of universities and PhD candidates in the study of tourism, especially in recent years. This trend indicates that the economic significance of tourism in global terms, claimed by the whole community and by international organizations has been followed by a scientific effort to study the phenomenon and its implications.

It should be noted that subjects such as hotel management, hospitality and education do not have a significant expression, which suggests that in the countries under analysis this is an area yet to explore. This can be a fine topic for further analysis, particularly in terms of comparison with other national realities with important tourism research units, such as the US, Canada, Australia and New Zealand, where these realities have been studied systematically.

One limitation to this paper has to do with the data collection methods, which were exclusively online-based. In order to include additional data in the analysis, contacts with national libraries should be pursued in the near future. This study has also performed a single discipline analysis and it would indeed be desirable to conduct a multidisciplinary examination in order to assess if there are some significant differences between disciplines and also between countries.

A second constraint is due to the fact that for comparing purposes, a particular category designation under which theses are registered locally might not be differentiating with regard to the subject itself. This has to do with circumstances both of national guidelines and traditions, and of research centres, which have different strengths, often in line with the work developed by certain leading scholars. This could only be solved through the reading of each dissertation and it is thus conceivable only in a major cooperation project between dozens of universities. Finally, there might be little conceptual distinctions between a dissertation generically integrating economics and a second, in a different country, perhaps registered under the label of (economic) sociology. The same goes for political science and law, or anthropology and history, or a range of other combinations.

Yet economics and sociology representing the vast majority of research fields under which theses are listed, it might be interesting to separate a pure management approach from organizational and structural analysis. Again, this requires meta-analysis at a scope far beyond that of this current paper.

The so-called Bologna process has induced new curriculum formats, including at doctoral level. Taking Spain and Portugal as an example, few universities are currently favouring individual dissertation-based initiatives, and prefer fostering doctoral track programmes that involve group activities, attending seminars and writing intermediate research papers. This state of affairs may contribute to change the matter of subject analysis, as these doctoral courses bear the same generic designation for a considerable and growing number of students. So even though the multiplicity of research subjects will likely continue to increase, a reduction in the range of core disciplines is very plausible.

References

ABES, A. B. (2011). Theses.fr. Retrieved February, 12, 2014 from: http://www.theses.fr/?q=tourism. [ Links ]

Adams, G. B., & White, J. D. (1994). Dissertation research in public administration and cognate fields: An assessment of methods and quality. Public Administration Review, 54(6), 565–576. [ Links ]

Airey, D., & Tribe, J. (2008). Educação Internacional em Turismo. São Paulo: Senac São Paulo. [ Links ]

Almeida Garcia, F. (2014). A comparative study of the evolution of tourism policy in Spain and Portugal. Tourism Management Perspectives 11, 34-50. [ Links ]

Amoah, V. A. & Baum, T (1997). Tourism education: policy versus practice. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management 9(1), 5-12. [ Links ]

Baum, T. (1998). Mature doctoral candidates: the case in hospitality education. Tourism Management 19(5), 463–474 [ Links ]

Brunner, E. (1945). Holiday Making and the Holiday Trade. London: Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

Chen, C. F. & Wu, C. C. (2005). A study on overseas travel motivations and market segmentation for the seniors. Tourism Management Research, 5(1), 1-16. [ Links ]

Chon, K. S. (Ed.) (2013). The practice of graduate research in hospitality and tourism. New York & Oxon: Routledge. [ Links ]

Cooper, C. (2014). Editorial. Tourism & Management Studies, 10(1), [ Links ] 1-1.

Costa, C. (2013). Investigação em Turismo: A experiência da Revista Turismo & Desenvolvimento. Revista Turismo & Desenvolvimento 20, 9-19. [ Links ]

Cunha, L. (2006). Economia e Política do Turismo. Lisboa: Editorial Verbo. [ Links ]

Dale, C., & Robinson, N. (2001). The theming of tourism education: a three-domain approach. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management 13(1), 30-35. [ Links ]

Dann, G. M., & Parrinello, G. L. (2009). The Sociology of Tourism - European origins and developments. Bingley: Emerald Group Publishing Limited. [ Links ]

DissOnline, G. N. (2012). DissOnline.de. Retrieved February, 12, 2014 from: http://www.dnb.de/DE/Wir/Kooperation/dissonline/dissonline_node.html [ Links ]

Echtner, C. M., & Jamal, B. T. (1997). The discipline dilemma of Tourism Studies. Annals of Tourism Research, 24(4), 868-883. [ Links ]

Formica, S. (1996). European hospitality and tourism education: differences with the American model and future trends. International Journal of Hospitality Management 15(4), 317-323. [ Links ]

Gartner, W. C. (1996). Tourism development: principles, processes and developments. New York: Jonh Wiley & Sons, [ Links ] Inc.

Hall, C., Williams, A., & Lew, A. (2014). Tourism: conceptualisations, disciplinarity, institutions and issues. In A. Lew, C. Hall, & A. Williams, The Wiley Blackwell Companion to Tourism (pp. 3-24). Chichester: John Wiley. [ Links ]

Hall, C. M., & Pedrazzini, T. (1989). Australian higher degree theses in tourism, recreation and related subjects. Occasional Paper No. 2. Lismore: Australian Institute of Tourism Industry Management, University of New England, Northern Rivers. [ Links ]

Horner, J.-M. (2000). Pour la reconanaissance d'une science touristique. Espaces, 173, Juillet-Aout. [ Links ]

Jafari, J. (1990). Research and Scholarship - The basis of tourism education. Journal of Tourism Studies, 1(1), 33-41. [ Links ]

Jafari, J., & Aaser, D. (1998). Tourism as the subject of doctoral dissertations. Annals of Tourism Research, 15(3), 407-429. [ Links ]

Jafari, J. & Ritchie, J.R.B. (1981). Toward a framework for Tourism Education: problems and prospects. Annals of Tourism Research, 8 (1), 13-34. [ Links ]

Jamal, T. (2005). Bridging the interdisciplinary divide: towards an integrated framework for heritage tourism research. Tourist Studies, 5(1), 55-83. [ Links ]

Leiper, N. (1981). Towards a cohesive curriculum in tourism: the case for a distinct discipline. Annals of Tourism Research, 8(1) , 69-84 [ Links ]

Macbeth, J. (2005). Towards an ethics platform for tourism. Annals of Tourism Research 32(4), 962-984. [ Links ]

Martins, F., & Albuquerque, H. (2013). Turismo de base natural - um instrumento de apoio à conservação de áreas húmidas. Revista Turismo & Desenvolvimento, 20, 81-90. [ Links ]

McKercher, B. & Prideaux, B. (2014). Academic myths of tourism. Annals of Tourism Research 46, 16–28. [ Links ]

Meyer-Arendt, K., & Justice, C. (2002). Tourism as the subject of North American doctoral dissertations, 1987-2000. Annals of Tourism Research, 29(4), 1171-1174. [ Links ]

Ministerio de Educación, Cultura y Deporte. (2013). TESEO. Retrieved from: https://www.educacion.gob.es/teseo/listarBusqueda.do [ Links ]

Moscardo, G., (2008). Building community capacity for tourism development. Oxfordshire: CABI. [ Links ]

Norval, A.J. (1936). Tourist industry. A national and international survey. London: Pitman &Sons. 343 [ Links ]

OECD (2014). OECD Tourism trends and policies 2014. Paris: OECD Publishing [ Links ]

Ogilvie, F.W. (1933). The tourism movement. London: Staples Press. [ Links ]

Peacock, N. & Ladkin, A. (2002). Exploring relationships between higher education and industry: a case study of a university and the local tourism industry. Industry and Higher Education, 16(6), 393-401. [ Links ]

Pike, S. (2003). A Tourism PhD reflection. Tourism Review – Revue de Tourisme, 58 (1), 16-18. [ Links ]

Pimlott, J. (1947). The Englishmans holiday. London: Faber and Faber. [ Links ]

PLEIADI. (2004). Portal for the Italian Electronic Literature in Open and Institutional Archives. Retrieved February, 12, 2014 from Portal for the Italian Electronic Literature in Open and Institutional Archives: http://www.openarchives.it/pleiadi/. [ Links ]

Rappole, C. L. (2000). Update of the chronological development, enrollment patterns, and education models of four-year, master's, and doctoral hospitality programs in the United States. Journal of Hospitality & Tourism Education, 12(3), 24-27. [ Links ]

Rodríguez-Antón, J. M., Alonso-Almeida. M. M., Rubio Andrada, L., & Celemín Pedroche, M. (2013). Are university tourism programmes preparing the professionals the tourist industry needs? A longitudinal study. Journal of Hospitality, Leisure, Sport & Tourism Education 12, 25–35. [ Links ]

RCAAP, R. C. (2008). RCAAP. Retrieved February, 12, 2014 from: http://www.rcaap.pt/ [ Links ]

Rae, W. F. (1891). The business of travel. London: Thos. Cook & Son. [ Links ]

Salgado, M., & Costa, C. (2011). Science and Tourism Education: national observatory for Tourism Education. European Journal of Tourism Hospitality and Recreation, 2(3), 143-157. [ Links ]

Sánchez, A. V. (2013). Investigación Científica en Turismo: la experiencia ibérica. Revista Turismo e Desenvolvimento, 20, 21-29. [ Links ]

Sheldon, P., Fesenmaier, D., Woeber, K., Cooper, C., & Antonioli, M. (2008). Tourism education futures, 2010–2030: building the capacity to lead. Journal of Teaching in Travel & Tourism, 7(3), 61-68 [ Links ]

Smith, L. (2010). Practical tourism research. Oxford: CABI Publishing. [ Links ]

Teng, C. C., Horng, J. S., & Baum, T. (2013). Academic perceptions of quality and quality assurance in undergraduate hospitality, tourism and leisure programmes: a comparison of UK and Taiwanese programmes. Journal of Hospitality, Leisure, Sport & Tourism Education, 13, 233–243. [ Links ]

The British Library Board. (2008). Ethos. Retrieved February, 12, 2014 from: http://ethos.bl.uk/SearchResults.do [ Links ]

Tribe, J. (2004). Knowing about tourism. Epistemological issues. In J. Phillimore & L. Goodson (Eds.), Qualitative research in tourism. Ontologies, epistemologies and methodologies. London and New York: Routledge. [ Links ]

Tribe, J. (2010). Tribes, territories and networks in the tourism academy. Annals of Tourism Research, 37(1), 7–33. [ Links ]

Tribe, J., & Airey, D. (2007). A Review of tourism research. In J. Tribe & D. Airey, Developments in tourism research (3-17). Oxford: Elsevier. [ Links ]

Turismo de Portugal. (2014). Os resultados do Turismo. 4.º trimestre e ano 2013. Retrieved February, 15, 2014 from: http://www.turismodeportugal.pt/Portugu%C3%AAs/ProTurismo/estat%C3%ADsticas/an%C3%A1lisesestat%C3%ADsticas/osresultadosdoturismo/Anexos/4.%C2%BA%20Trim%20e%20Ano%202013%20-%20Os%20resultados%20do%20Turismo.pdf [ Links ]

UNWTO. (2014). UNWTO World Tourism Barometer, Volume 12, April 2014. Madrid: UNWTO.

UNWTO. (2014a). UNWTO Tourism Highlights, 2014 Edition. Madrid: UNWTO. [ Links ]

Verhoeven, G. (2013). Foreshadowing tourism. Looking for modern and obsolete features – or some missing link – in early modern travel behavior (1675–1750). Annals of Tourism Research, 42, 262–283. [ Links ]

Vukonic, B. (2012). An outline of the history of tourism theory. In C. H. Hsu, & C. W. Gartner, The Routledge Handbook of Tourism Research (3-20). New York: Taylor & Francis Group. [ Links ]

Walton, J. K. (2009). Prospects in tourism history: evolution, state of play and future developments. Tourism Management 30, 783–793. [ Links ]

Weiler, B., & Laing, J. (2008). Postgraduate tourism research in Australia: A trend analysis of 1965–2005. [ Links ] Paper Presented at CAUTHE, Gold Coast, Australia, 2008.

Weiler, B., Moyle, B., & McLeannan, C. (2012). Disciplines that influence tourism docotral research: the United States, Canada, Australia and New Zealand. Annals of Tourism Research, 39(3), 1425-1445. [ Links ]

Xiao, H. &. (2006). The making of tourism research: insights from asocial sciences journal. Annals of Tourism Research, 33(2), 490–507. [ Links ]

Zhao, W. & Ritchie, J. R. B. (2007). An investigation of academic leadership in tourism research: 1985–2004. Tourism Management, 28, 476–490. [ Links ]

Article history:

Received: 22 May 2014

Accepted: 12 November 2014