Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Indicators

-

Cited by SciELO

Cited by SciELO -

Access statistics

Access statistics

Related links

-

Similars in

SciELO

Similars in

SciELO

Share

Tourism & Management Studies

Print version ISSN 2182-8458

TMStudies vol.10 no.Especial Faro Dec. 2014

TOURISM - SCIENTIFIC PAPERS

Empirical analysis of the constituent factors of internal marketing orientation at Spanish hotels

Análisis empírico de los factores que conforman la orientación al marketing interno de los hoteles españoles

José Luis Ruizalba Robledo1; María Vallespín Arán2

1University of Málaga, Departamento de Economía y Administración de Empresas, Spain, jruizdealba@uma.es

2University of Málaga, Departamento de Economía y Administración de Empresas, Spain, mvallespin@uma.es

ABSTRACT

This study, which draws upon specialized literature and empirical evidence, aims to characterize the underlying structure of the construct ‘Internal Marketing Orientation’ (IMO). As a consequence six underlying factors are identified: exchange of values, segmentation of the internal market, internal communication, management concern, implementation of management concern and training. It also evaluates the degree of Spanish hotels’ IMO, classifying them into three different groups according to their level of IMO. Findings indicate that a higher degree of IMO is found when the company belongs to a hotel chain, while no other variables such as hotel size or category have proven to be significant.

Keywords: Internal Marketing Orientation, Hotels, Work Family Balance, Cluster Analysis, Internal Communication.

RESUMEN

Este trabajo apoyándose en la literatura y desde la evidencia empírica trata de recoger y caracterizar la estructura que subyace en el constructo de Orientación al Mercado Interno (OMI). Se concluye identificando seis factores subyacentes: intercambio de valores, segmentación interna, comunicación interna, interés de la dirección, implementación del interés a través de la conciliación entre la vida familiar y profesional y la formación. Asimismo se procede a evaluar el grado de OMI de los hoteles españoles resultando una clasificación en la que se encuentran tres grupos bien diferenciados según su nivel de OMI. Además, los resultados indican que se encuentran niveles de implementación más altos de OMI cuando la empresa pertenece a una cadena hotelera, no resultando significativas variables como la categoría o el tamaño del hotel.

Palabras claves: Orientación al marketing interno, hoteles, conciliación, análisis cluster, comunicación interna.

1. Introduction

Internal marketing has emerged as a central topic of great importance, both in the academic and in the professional discourse. Without minimizing the value of the external customer, organization is intended to consider itself as a market (domestic market) where human resources (internal customers) are the main consumers (Mendoza et al., 2011.)

Thus, it is found that the role of service employees is important in relation to customer satisfaction (Tornow and Wiley, 1991; Foster and Cadogan, 2000; Donovan and Hocutt, 2001), considered as a key element in commercial business strategy for value creation (Berry, 1981). In other words, studies show the relationship between the external customer and the internal customer satisfaction and indicate the need to focus on how to provide the quality of internal service so that it has a positive influence on external customer satisfaction (Gutierrez and Rubio, 2009).

Furthermore, market orientation has had a major impact on the practice of marketing, and has been empirically validated as a way to increase business performance. Gounaris (2006) suggests that the philosophy of Market Orientation concept is analogous to the Internal Market Orientation (hereinafter IMO) Domestic Market. As a result, in recent years, in addition to analyzing Internal Marketing from different perspectives, many studies are developing models to measure Internal Market Orientation (IMO) based on the paradigm of Market Orientation (Kohli and Jaworsky, 1990). In this sense, Piercy (1995) states that there is a parallelism between what happens in the external and the internal market.

In addition, the tourism sector and in particular the hotel industry, as long as they offer their customers an intangible product or service, face the problem of service quality. Berry et al. (1976) are the first to propose Internal Marketing (hereafter IM) as a solution to this problem, since the quality of internal services undoubtedly guarantees the quality of the product or service that the external customer expects (Mendoza et al. 2011). Greene et al. (1994) affirm that IM is the key to obtaining a superior service and successful results in external marketing.

However, there is little empirical research dedicated to this particular field (IMO in the hotel industry), so further research is needed (Lings and Grenley, 2005; Gounaris, 2008; Kaur et al. 2010; Avlonitis and Giannopoulos, 2012). Besides, and according to Tortosa-Edo et al. (2010), the dimensions that constitute IMO together with its validity are the next challenges for the scientific community.

2. Theoretical framework

2.1. Internal market orientation: Concept and dimensions

The concept of IM was first introduced in the 1970s, derived from the need of companies to meet customers’ needs in order to achieve greater success (Berry et al., 1976; Sasser and Arbeit, 1976). It was based on the assumption that in order to have satisfied customers, companies also need to have satisfied employees, as staff play a key role in providing quality service (Sasser and Arbeit, 1976; García et al. 2011).

After a thorough literature review we have focused on authors who have conceptualized and empirically tested the IMO construct (Lings, 2004; Lings and Greenley, 2005; and Gounaris, 2006, 2008). The construct of Internal Marketing Orientation is consequently constituted by three dimensions: (a) generation of intelligence through data collection from the company internal market, (b) communication of internal market intelligence and its dissemination in the organization, (c) response to internal market intelligence by the company.

A. Generation of intelligence from the internal market

The first dimension, generating internal market intelligence, involves collecting information to identify possible improvements. It refers to activities such as the identification of value exchange ??and the detection of inner segments with different characteristics and needs.

This generation of intelligence is initially produced by a value exchange. Thus, in the employee-employer relationship, an exchange of values takes place, consisting of a balance between the value each employee brings to the company and the value the company brings to them. Similarly, the equity theory suggests that employees evaluate their work by comparing what they bring to the company in which they work with what they obtain from it (Huseman and Hatfield, 1990). In this sense, this balance should lead to a mutually satisfactory environment because otherwise the relationship can easily break or become very asymmetrical forming a poor quality bond.

On the other hand, the detection of specific employee segments with different characteristics can be carried out in terms of their needs and demands. This will then allow a more detailed analysis focused on customized solutions. Accordingly, strategies vary depending on the various segments since the problems are different for each of them. Lings (2004) argued the desirability of targeting depending on the degree of employees’ relationship with external customers. In this sense, this segmentation would aim to seek a greater focus on the external customer with the benefits that this entails.

B. Communication of internal market intelligence

The second dimension makes reference to the fact that after obtaining market information, it is necessary to communicate or disseminate it within the company in order to analyze it.

This is mainly done through communication activities, which play an important role in nurturing the identification with the company (Smidts, Pruyn and Riel, 2001). In this sense, several authors have shown that bidirectional informal communication between managers and employees has very positive effects on the results carried out by employees who are in direct contact with external customers (Johlke and Duhan, 2000).

Therefore, internal communication refers to stimulus that the company is able to generate in workers, with the purpose of fostering interaction across different (internal and external) channels and their awareness of the importance of knowledge sharing (Chen and Cheng, 2012).

Furthermore, Grönroos (2000) considers that the organization must communicate both its views and its strategies and methods through brochures, newsletters, magazines, and other media to facilitate employees’ understanding and acceptance. In this regard, the concept of internal communication is broad, ranging from employees’ needs to strategic objectives - goals, future plans, etc., - which must be communicated properly.

On the other hand, while Greene et al. (1994) argue that it is necessary to "sell" the company concept - objectives, strategies, structures, leaders and other components – as a way to make employees feel part of the organization and to achieve results in productivity (Mendoza et al. 2011); Townley (1989) defines the process of internal communication as a sale itself, especially when face to face communication is delivered and when content covers the ideas and objectives that managers want to "sell" to their employees.

C. Response to internal market intelligence

Once information has been generated and spread within the organization, the next step is to decide what kind of response will be offered.

This dimension is formed by factors such as the managers’ concern for employees, the company efforts to cater for the staff training, and the reconciliation of personal and professional life.

According to Lings (2004), the social nature of Internal Marketing is reflected clearly in the concept of "managers’ concern", which does not mean that managers have to give their employees’ carte blanche to meet all their needs, but simply measures the degree to which supervisors recognize employees as individuals and treat them with dignity and respect. "Concern" in this context refers to the extent to which managers develop a work climate of psychological support, aid, friendship and mutual trust and respect (Johnston et al. 1990).

Furthermore, Eisenberger et al. (1986) developed an interesting study whose findings suggest that if employees perceive that the organization is interested in them, seeks their well-being and provides help with personal problems when necessary, the consequences are very favorable for the organization in terms of enhanced performance and permanency desires.

In the same line, Hammer et al. (2009) developed a multidimensional model for measuring managers’ degree of performance in relation to the support provided to employees regarding their work family balance. During the last 30-40 years there has been a great change in reconciliation of personal and working life, due to the massive incorporation of women into the workforce. As a result, managers must deal with a strong demand for support and policies in terms of work and family.

2.2. Internal marketing orientation in the hotel sector

The hotel sector, where the importance of customer service is essential (Sigala, 2005), is especially well positioned to take advantage of IMO.

IM was developed in the context of services (Avlonitis and Giannopoulos, 2012). The hotel industry has a number of features that are particularly relevant when developing relationship marketing strategies: lower degree of tangibility, inseparability of production and consumption, heterogeneity, and non-storability (Robledo, 1998). This means that in hotels, the role of frontline employees who have direct interaction with customers is of special importance to the quality of service provided.

Furthermore, recent studies on the tourism sector in the European Union (EU) warn that tourism enterprises are more driven by the product than by the consumer. Besides, the industry presents a great lack of innovative solutions to face relevant challenges, which suggests that little attention is paid to creating added value (García et al., 2011). Additionally, hotel companies are confronting an increasingly competitive and complex market, where customer loyalty and brand fidelity is declining (Piccoli et al., 2005; Padilla and Garrido, 2012).

The role of human factor through professional and personal expression, particularly in innovation-oriented companies, has also been highlighted in recent research (Martínez-López and Vargas-Sánchez, 2013). However, according to Reynolds (2013), much of the hotel industry is renowned for not being the most progressive industry in the adoption and application of latest thinking areas such as human resource strategies and motivation. Consequently all efforts aimed at improving customer satisfaction by acting on employees’ performance are of special value.

In this sense, Berry and Parasuraman (1992) propose "internal marketing" as a basis for encouraging "external marketing" and thereby facilitate customer satisfaction. In other words, in order to generate high value for customers, satisfied, loyal, committed and productive employees are required (Heskett, Sasser and Schlesinger, 2003; Lescano, 2011). Employees in hotel service companies have an important weight, not only because their wages constitutes 27% of the total costs -and as expressed by Gemar and Jiménez (2013) this cost share has continued to increase in 2012-, but also because their interaction with clients is important for the service inseparability.

For all the above reasons and following Gounaris (2006), IMO is presented as a key strategy in the hotel industry for obtaining the best results, thus the relevance of the chosen field of study to develop this research is justified.

3. Methodology

3.1. Research objectives

Literature indicates the desirability of analyzing through field studies the extent to which hotel companies in Spain apply IMO. Consequently, the specific objectives of this study are:

a) To develop a valid and reliable instrument to measure the degree of IMO, identifying the various underlying factors;

b) To use this instrument to measure the IMO degree of Spanish hotel companies;

c) To classify hotel companies according to their IMO level, in order to draw conclusions regarding the differences that may occur in relation to various characteristics such as number of employees, category and hotel chain.

3.2. Empirical analysis

Due to the exploratory nature of our study, empirical research was initially developed through a qualitative phase. As stated by Lings (2004), any changes in the Markor scale for its use in IM should be preceded by qualitative research. Therefore, this phase has been focused on the development of the scales and the items, which were presented to Marketing, Human Resources and Senior Management professionals of the hotel sector. Specifically, five interviews with top professionals - working at their company headquarters - and nine interviews with academic experts were conducted. Thanks to the analysis of these in-depth interviews some questionnaire items were removed and the wording of some questions was modified so that they could be better understood.

The data extracted from this qualitative analysis and literature review justify the structure and content of a survey addressed to key informants from each of the Spanish hotels that have later been subjected to quantitative analysis.

The sample was composed by hotel key informants, since in the majority of cases this position represents the link between the company top management and the rest of employees. Most of them were middle-level managers with a great vision of the company and the ability to interact at different levels of the organization. Moreover, these key informants constitute an important element in the development of a hotel IMO, regardless of top management and ownership policies, since they act as moderators - either positively or negatively - with their own management style.

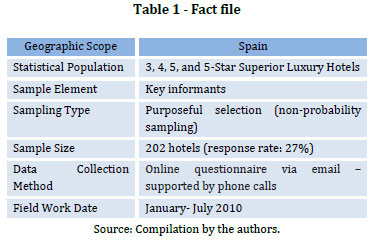

Table 1 below shows the fieldwork fact file.

3.3. Variables measurement

The questionnaire was divided into two parts:

· The first block includes 22 questions regarding the IMO level of the hotel company. The variables are presented as statements on a 7-point Likert scale, from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree).

· The second block comprises classification questions: respondent gender, hotel category, company size - by number of employees -, and hotel chain.

Previous studies were reviewed for the construction of this questionnaire. The works by Kohli and Jaworsky (1990), Lings (2004), Thompson and Prottas (2005), Gounaris (2008) and Hammer et al. (2009) were primarily taken as a reference.

In this sense, we have simplified Lings’ model (2004) since it has only been tested empirically once (Lings and Grenley, 2005), being therefore the development of IMO measuring models in a very experimental phase. In fact, the author suggests incorporating new factors and even considers some factors may not necessarily make sense in other cultures (Hofstede, 1994). We have respected Lings’ three dimensions and have incorporated the work family balance subdimension, which comprehends what Lings (2005) identifies as social elements.

4. Results

4.1. Reliability and scale underlying dimensions

In order to assess the measurement scale used in the first section of the questionnaire, three basic scale aspects were analyzed: the conceptual definition, reliability and dimensionality (Hair, Anderson, Tatham and Black, 2007).

To ensure content validity, thirteen professionals including top professionals at senior management positions as well as academian experts were selected to conduct a pre-test. As already stated, they ratified the suitability of this instrument and provided useful suggestions which were taken into account and incorporated in due course.

As for the reliability of the scale, it was tested by Cronbach's alpha coefficient. The Cronbach coefficient is over 0.7 in all cases (see Table 2), therefore higher than the minimum accepted in the exploratory stages of scale development (Miquel et al., 1997).

Furthermore, we analyze the scale dimensionality through three exploratory factor analysis (EFA), one for each dimension: intelligence generation, internal communication and response to intelligence. After performing the reliability analysis and exploratory factor analysis, results suggest the elimination of variable V7. As a consequence, the initially proposed scale was refined, obtaining a 21-item scale that will be used in the next section for the descriptive analysis.

The extraction method was the principal component analysis (PCA) with Varimax rotation. Data are suitable for PCA implementation, because as Hair et al. (2007) stated, the number of observations is at least five times higher than the number of variables to be analyzed. Besides, the prior existence of a correlation structure among the variables was verified. The value of Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO) index was greater than 0.8 and Bartlett's test of sphericity was always significant. In addition, extracted communalities and factor loadings exceeded 0.6 in all cases.

Table 2 below shows the reliability and unidimensionality analysis results.

4.2. Degree of internal marketing orientation in Spanish hotels

Once the underlying factors of the IMO construct had been identified, the dimension set was used to conduct a descriptive analysis in order to examine the IMO level of hotels in Spain.

Table 3 shows that the most developed dimension by the Spanish hotel industry is Internal Communication with a mean score of 5.6. On the contrary, Internal Intelligence Generation is the dimension with a lower score - 4.9 in value exchange identification and 4.1 in segmentation -, exceeding in any case the scale midpoint. The relevance of this situation for business practice will be discussed later in the conclusions.

If we compare these results with an analogous study by Chen and Cheng (2012) with 346 hotels in Taiwan, Spanish hotels seem to have a similar degree of IM implementation. While the hotels in Taiwan scored an average of 3.56 out of 5 in Spanish hotels the mean score is 4.95 out of7.

4.3. Hotel classification according to their level of internal market orientation

A cluster analysis was performed with the aim of detecting the existence of hotel groups clearly differentiated by their IMO levels (Pung and Stewart, 1983).

As suggested by Hair et al. (2007), both hierarchical and non-hierarchical methods were used for the selection of the final cluster solution, thereby obtaining the benefits of each. Squared Euclidean distance was taken as a distance measure, and the Ward method as the hierarchical procedure, concluding that three was the appropriate number of clusters.

In order to detect significant differences among the clusters, multivariate analysis of variance (MANOVA) and univariate analysis of variance (ANOVA) were performed. As shown in Table 4, mean scores reveal significant differences in all cases - at a 1% significance level - with respect to the three groups detected.

The first cluster comprises 80 hotels. They all show a significantly high mark on their IMO, that we called ‘hotels with a clear internal market orientation.’ These hotels score over 6 for internal communication and managers’ concern, while the rest of variables score above 5. The second cluster includes 89 hotels. It is the largest cluster and its variables take mean values around 4.8. In contrast, the third and smallest cluster consists of 33 hotels. These companies display a lower IMO and their valuations do not reach the scale midpoint, except for the internal communication dimension with 4.21.

Once the presence of the three groups had been detected, their characteristics were identified (see Table 5). For that purpose, contingency tables were built and Phi and Cramer’s V coefficients were analyzed.

Clusters are not defined by characteristics such as manager gender, hotel category and hotel size by number of employees. On the contrary, hotel chain membership has proven to be significant. Consequently, it can be concluded that the IMO degree and hotel chain membership variables are correlated, and hotels belonging to chains develop a greater IMO. In cluster 3 – hotels with low IMO - 75.8% of the hotels are not part of any chain.

5. Limitations, future research and conclusions

As any piece of research, this work presents some limitations. Firstly, this study was only carried out in the hotel industry. Secondly, a multilevel analysis of different categories of employees could have been performed in order to analyze possible differences in their IMO perception. Nonetheless, in an attempt to alleviate this drawback, key informants were selected taking into consideration their multilevel interaction with employees and managers across the organization.

These two limitations suggest two lines for future research. On the one hand, this study should be extended to other sectors. On the other hand, a multilevel analysis could compare the perspectives of different status employees.

To conclude, it should be noted that the literature review has allowed the compilation of the main findings concerning the current state of the art of IMO research, and has revealed the need to develop an instrument to measure and analyze the different construct dimensions. Moreover, the empirical evidence is sufficient to conclude that the scale used shows positive validity and reliability indexes.

Additionally, the IMO degree of hotel companies in Spain was measured. Internal communication was the factor with a higher score. On the contrary, the generation of internal intelligence dimension obtained the worst score. It should be highlighted that this dimension includes variables on which companies can act with low economic cost. Hence, findings suggest business practice should devote resources to find employees’ needs, which, with low investment, may have a positive impact on the IMO and consequently improve the company results.

The study has built a classification of Spanish hotels according to their IMO level. Three groups with significant differences. The first group is constituted by hotels with a higher IMO. This group consists of 80 hotels, where 36 of them are medium sized. The second cluster is the largest and consists of 86 hotels, all of them with a medium IMO degree but with very diverse characteristics. The third group is formed by hotels with ratings below 4 in most of the factors, and therefore lower than those of the other two groups. Only 33 hotels belong to this cluster, in which 75.8% of them are not members of any hotel chain.

Finally, in order to define each of the obtained groups, it was detected that hotels belonging to a chain have greater IMO levels, and no other significant variables such as category or hotel size were relevant. This finding is not only coherent, since it suggests that hotel chains foster IMO, but also surprising, as long as the hotel category does not exert any influence. In this sense, it would seem logical to expect that higher category hotels are more worried about the service quality provided and therefore adopt greater IMO levels.

References

Avlonitis G.J & Giannopoulos A. A. (2012). Balanced market orientation: qualitative findings on a fragile equilibrium. Managing Service Quality, 22(6), 565-579. [ Links ]

Berry, L.; Hensel, J.S. & Burke, M.C. (1976). Improving retailer capability for effective consumerism response. Journal of Retailing, 52(3), 3-14. [ Links ]

Berry, L.; Parasuraman, A. (1992). Services marketing starts from Within. Marketing Management, 1(1), 24-34. [ Links ]

Berry, L. (1981). The employee as Customer. Journal of Retailing Banking, 3(1), 33-40. [ Links ]

Bollen, K.A. (1989). Structural equations with latent variables. Wiley-Interscience Publication: New York. [ Links ]

Chen W-J & Cheng H-Y (2012). Factors affecting the knowledge sharing attitude of hotel service personnel. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 31(2), 468– 476. [ Links ]

Donovan, D.T. y Hocutt, M.A. (2001). Customer evaluation of service employee´s customer orientation. Extension and application. Journal of Quality Management ,6 (2), 293-306. [ Links ]

Donovan, D. T.; Brown, T. & Mowen, J. C. (2004). Internal benefits of service-worker customer orientation: Job satisfaction, commitment and organizational citizenship behaviours. Journal of Marketing, 68(1), 128-146. [ Links ]

Eisenberger, R; Hungtington, R.; Hutchinson & S.; Sowa, D. (1986). Perceived organizational support. Journal of Applied Pshychology, 71, 500-507. [ Links ]

Foster, B.D. & Cadogan, J.W. (2000). Relationship selling and customer loyalty: an empirical investigation. Marketing, Intelligence and Planning, 18(4),185-99. [ Links ]

García, N., Álvarez, B. & Santos, M.L. (2011). Aplicación de la lógica dominante del servicio en el sector turístico: El marketing interno como antecedente de la cultura de co-creación de innovaciones con clientes y empleados. Cuadernos de Gestión, 11(2), 53-75. [ Links ]

Gemar, G. & Jiménez, J.A. (2013). Retos estratégicos de la industria hotelera española del siglo XXI: Horizonte 2020 en países emergentes. Tourism & Management Studies, 9(2), 13-20. [ Links ]

Gounaris, S. (2006). Internal-market orientation and its measurement. Journal of Business Research, 59 (4), 432-448. [ Links ]

Gounaris, S. (2008). The notion of internal market orientation and employee job satisfaction: some preliminary evidence. Journal of Services Marketing, 22(1), 68-90. [ Links ]

Greene, W. E., Walls, G. D. & Schrest, L. J. (1994). Internal marketing, the key to external marketing success. Journal of Services Marketing, 8(4), 5-13. [ Links ]

Gronroos, C., (2000). Service Management and Marketing – a Customer Relationship Management Approach. 2nd ed. Wiley and Sons, New York. [ Links ]

Gutiérrez S. &Rubio M. (2009). El factor humano en los sistemas de gestión de calidad del servicio: un cambio de cultura en las empresas turísticas. Cuadernos de Turismo, 23, 129-147. [ Links ]

Hair, J.F.; Anderson, R.E.; Tatham, R.L. and Black, W.C. (2007): Análisis multivariante. 5ª: Pearson-Prentice Hall. [ Links ]

Hammer, L.B; Kossek, E.E; Yragui, N.L; Bodner, T.E & Hanson G.C (2009). Development and validation of a Multidimensional Measure of Family Supportive Supervisor Behaviors (FSSB). Journal of Management, 35(4), 837–856. [ Links ]

Heskett, J.; Sasser, W. E. & Schlesinger, L. (2003). The value profit chain. The free press, New York. [ Links ]

Hofstede, G. (1994). Cultural constrains in management theories. International Review of Strategic Management, 5, 27-47. [ Links ]

Huseman, R. & Hatfield, J.D. (1990). Equity theory and the Managerial Matrix. Trainning and Development Journal, 44(4), 98-102. [ Links ]

Johlke, M.C. & Duhan, D.F. (2000). Supervisor communication practices and service employee job outcomes. Journal of Service Research, 3 (2), 154-65. [ Links ]

Johnston, W; Parasuraman, A.; Futrell, C. & Black, W. (1990). A longitudinal assessment of the impact of selected organizational influences on sales-peoples´s organizational commitment during early employment. Journal of Marketing Research, 27, 333-344. [ Links ]

Kaur, G., Sharma, R.D. & Seli, N. (2010). An assessment of internal market orientation in Jammu and Kashmir bank through internal supplier’s perspective. Journal of Services Research, 10 (2), 117-41. [ Links ]

Kohli, A & Jaworski, B. (1990). Market Orientation: The Construct, Research Propositions and Managerial Implications, Report No. 90- 113, Marketing Science Institute, Cambridge, MA.

Kossek, E.E. & Lambert, S. (2005). Work-family scholarship: voice and context. In Kossek, E.E. & Lambert, S. (Ed.), Work and life integration: organizational, cultural and individual perspectives (pp 3-18). Mahwah. [ Links ]

Lescano, L.R (2011). Liderazgo de servicios de los mandos intermedios. Cuadernos de gestión, 11, 73-84. [ Links ]

Lings, I.N. (2004). Internal market orientation: constructs and consequences. Journal of Business Research, 57(4), 405-13. [ Links ]

Lings, I.N. & Greenley, G.E. (2005). Measuring internal market orientation. Journal of Service Research, 7 (3), 290-305. [ Links ]

Martínez-López, A.M. & Vargas-Sánchez, A. (2013). Factores con un especial impacto en el nivel de innovación del sector hotelero español. Tourism & Management Studies, 9(2), 7-12. [ Links ]

Mendoza, J.; Hernández, M. & Tabernero, C. (2011). Retos y oportunidades de la investigación en marketing interno. Revista de Ciencias Sociales (RCS), XVII (1), 110-125. [ Links ]

Miquel, S.; Bigné, E.; Lévy, J.P.; Cuenca, A.C. & Miquel, M.J. (1997). Investigación de mercados. McGraw-Hill, Madrid. [ Links ]

Neal, M.B. & Hammer, L.B. (2007). Working couples caring for children and aging parents: Effects on work and well-being. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc.

Padilla, A. & Garrido, A. (2012). Gestión de relaciones con clientes como iniciativa estratégica: implementación en hoteles. Revista Venezolana de Gerencia (RVG), Año 17(60), 587-610 [ Links ]

Piccoli, G. & Ives, B. (2005). Review: IT-dependent strategic initiatives and sustained competitive advantage: a review and synthesis of the literature. MIS Quaterly, 29(4), 747- 776. [ Links ]

Piercy, N. (1995). Customer satisfaction and the internal market: Marketing our customers to our employees. Journal of Marketing Practice and Applied Marketing Science, 1, 22-24. [ Links ]

Punj, G. & Stewart, D.W. (1983). Cluster analysis in marketing research. Review and suggestions for applications. Journal of Marketing Research, 20, 134-148. [ Links ]

Reynolds, P. (2013). Hotel companies and corporate environmentalism. Tourism & Management Studies, 9(1), 7-12. [ Links ]

Robledo, M.A. (1998): Marketing Relacional Hotelero. EPE, S.A. [ Links ]

Sasser, E.W. & Arbeit, S.P. (1976). Selling jobs in the services sector. Business Horizons, 19 (3), 61-65. [ Links ]

Sigala, M. (2005). Customer relationship management in hotel operations: managerial and operational implications. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 24(3), 391-413. [ Links ]

Smidts, A.; Pruyn, A. & Riel, C. (2001). The impact of employee communication and perceived external prestige on organizational identification. Academy of Journal Management, 44(5), 1051-62. [ Links ]

Thomas L.T. & Ganster, D.C. (1995). Impact of family-supportive work variables on work-familiy conflict and strain: a control perspective. Journal of Applied Psychology, 80 (1), 6-15. [ Links ]

Thompson, C.A., Beauvis, L.L., & Lyness, K.S. (1999). When workfamily benefits are not enough: the influence of work-family culture on benefit utilization, organizational attachment, and work-family conflict. Journal of Vocational Behaviour, 54, 392-415. [ Links ]

Thompson, C.A. & Prottas, D. (2005). Relationships among organizational family support, job autonomy, perceived control, and employee well-being. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 11 (1), 100-118. [ Links ]

Tornow, W.W. & Wiley, J.W. (1991). Service quality and management practices: a look at employee attitudes, customer satisfaction, and bottom-line consequences. Human Resource Planning, 14 (2), 105-16. [ Links ]

Tortosa-Edo V., Sánchez-García J. & Moliner-Tena, M.A. (2010). Internal market orientation and its influence on the satisfaction of contact personnel. The Service Industries Journal, 30 (8), 1279-1297. [ Links ]

Townley, B. (1989). Selection and appraisas: reconstituting “social relations”. In Storey, J. (Ed.), New perspectives on human resource management (pp. 92-108). Routledge, London. [ Links ]

Article history

Submitted: 28 June 2013

Accepted: 22 November 2013