Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Acessos

Acessos

Links relacionados

-

Similares em

SciELO

Similares em

SciELO

Compartilhar

Tourism & Management Studies

versão impressa ISSN 2182-8458

TMStudies vol.10 no.Especial Faro dez. 2014

MANAGEMENT - SCIENTIFIC PAPERS

Top-down and bottom-up approach to competence management implementation: A case of two central banks

Abordagem top-down (de cima para baixo) e bottom-up (de baixo para cima) para a implementação de gestão de competências: O caso de dois bancos centrais

Jerzy Rosinski1; Jacek Klich2; Agata Filipkowska3; Richard Pettinger4

1Jagiellonian University, Institute of Economics and Business, ul. Gronostajowa 3, 30-387 Krakow, Poland, jerzy.rosinski@uj.edu.pl

2The Economics University, ul. Rackowicka 27, 31-510 Krakow, Poland, uuklich@cyf-kr.edu.pl

3National Bank of Poland, HR Department, PL 00919 Warsaw, Poland, agata.filipkowska@papass.com.pl

4University College London, Department of Management Science and Innovation, Gower Street, London WC1E 6BT, UK, r.pettinger@ucl.ac.uk

ABSTRACT

The primary aim of this paper is to evaluate the contribution that competence based approaches to staff management can and ought to make to the overall effectiveness of organisations. The importance of competencies and their proper management is broadly acknowledged in the literature, and the first part of the paper is a literature review. This is followed with a comparison of the design and implementation of two competence management projects that were introduced in two central banks, one of a western European nation, and the other of a central European nation.

There is a brief presentation of two fundamental approaches to competence management implementation in organization (top-down (directive) and bottom-up (participative)), and this is juxtaposed with the actual implementation of competence management model that took place in two central banks.

What ensues from the comparison is the identification of potential threats to the implementation of competence management models in organizations, accompanied by suggestions on how to counteract them.

Keywords: Strategic HRM, competencies, competence management, organisation development, HR development strategies.

RESUMO

O objetivo principal deste trabalho é avaliar o contributo que as abordagens baseadas nas competências na gestão do pessoal pode e deve dar para a eficácia global das organizações. A primeira parte do artigo faz uma revisão da literatura, na qual a importância das competências e da sua correta gestão é amplamente reconhecida. Segue-se uma comparação entre o desenho e implementação de dois projetos de gestão de competências que foram introduzidas em dois bancos centrais, um de um país da Europa Ocidental e outro de um país da Europa Central.

Há uma breve apresentação de duas abordagens fundamentais para a implementação da gestão de competências numa organização (top-down (diretiva) e bottom-up (participativa)), sendo isto justaposto com a implementação do modelo de gestão de competências que ocorreu em dois bancos centrais.

O que resulta da comparação é a identificação de ameaças potenciais à implementação de modelos de gestão de competências nas organizações, acompanhada de sugestões sobre a forma de neutralizá-las.

Palavras-chave: Gestão estratégica de recursos humanos, competências, gestão de competências, desenvolvimento organizacional, estratégias de desenvolvimento de recursos humanos.

Introduction

The importance of competencies in the performance of firms is a theme that runs throughout the relevant literature; and the uniqueness of firms constitutes one clear basis for competitive advantage and long-term success (Coase, 1937; Penrose, 1959; Schumpeter, 1934). A key factor that constitutes and strengthens firms’ uniqueness is the capabilities – the competencies – of their employees. Although “competence” as a term is broadly applied, some definition problems occur when trying to distinguish between, for example “competence”, “capability” and “core competencies”. For the purpose here, we will follow Javidan’s (1998) proposition, that these three terms refer to the span of advantage within a firm, within a department, within a single strategic business unit (SBU) or across multiple SBUs; and that competencies may be seen as firm-specific technologies and production technologies whereas capabilities are firm-specific business practices, processes and culture (Marino, 1996).

Competencies

Core competencies as defined by Prahalad and Hamel (1990) are corporate, broad technologies and production skills that empower individual businesses to adapt quickly to changing opportunities. Following Walsh and Linton’s suggestion that the goal should be to identify competencies relevant to a specific industry (Walsh & Linton, 2002), we maintain that to make this operational is, by its nature, the most challenging part, namely, the process of development and implementation of competence management projects in organisations (Bergenhenegouwen, Ten Horn & Mooijman, 1997; Belkadi, Bonjour & Dulmet, 2007).

The notion of competence management is connected and equated with knowledge management (Sanchez, 2001; Sanchez & Heene, 2005). Effective identification of required knowledge and core competencies is a driving force leading to competitive advantage (Prahalad & Hamel, 1990). This in turn is closely related to the structuring and implementation of human resources strategies and practices (Hagan, 1996).

As Hamel and Prahalad (1994) stipulate, corporate management teams must understand and participate in five key competence management tasks: 1) identify existing core competencies, 2) establish a core competence acquisition agenda, 3) build core competencies, 4) deploy competencies, and 5) protect and defend core competence leadership (Hamel & Prahalad, 1994). Additionally, Berio and Harzallah (2007) distinguish between four classes of processes in competence management: competence identification, competence assessment, competence acquisition and competence usage.

In a rapidly evolving competitive environment, there is a growing concern about the ongoing updating of competency reference data and the accuracy in matching competencies with the tasks that need to be performed (Belkadi et al., 2007).

The question whether an organisation should embark on this task using its own resources or contract external expertise for this purpose (Vloeberghs & Berghman, 2003) remains unanswered.

Conceptually easy as it is, competence management proves difficult to implement (Cotora, 2007; Boucher, Bonjour & Matta, 2007) as it is a complex and challenging task. Additionally, the number of models and tools available to assist managers with competence management is far from sufficient (Harzallah, Berio & Vernadat, 2006; Zülch & Becker, 2007).

There is an extensive body of literature on firms that have achieved success by using strategies that focus on their firms’ core capabilities and competencies (Hitt & Ireland, 1985; Morone, 1993; Teece, Pisano & Shuen, 1990). Moreover, industry sectors have been more broadly studied in this respect (Kwangseek, Booth & Hu, 1997; Bergenhenegouwen et al., 1997) than service sectors (Seppänen & Skaates, 2001; Knudsen, 2005). In particular, the banking sector is virtually absent in the literature on this subject. This paper aims to fill one part of this gap by evaluating how competency-based approaches to organisation development and performance have been implemented by two central banks – one from central Europe, the other from Western Europe.

Top-down and Bottom-up Approach to Competence Management Implementation

The distinction between a top-down or a bottom-up approach to strategy development may be applied to the implementation of competence management in an organisation. Competence management embraces analysis of needs and subsequent design of competencies portfolios, provision of timely and place-relevant competencies, ways to encourage people to develop necessary competencies, analysis and evaluation of relationships between required competencies and achievable ones, and their subsequent alignment (Oleksyn, 2006: 186 – 187). Following the above models in practice as well as in theoretical reflection, we may distinguish between two contrasting approaches to competence management implementation:

1. Participative approach involving employees’ participation in competence management implementation, also known as the bottom-up approach.

2. Directive approach (or expert approach) whereby competence implementation is directed from the top of the organisation, and enabled by external consultants (Rzadkowska, 2006, 31-32; Filipowicz, 2004, 53), also known as the top-down approach.

Whichever approach is adopted, there are common elements and factors connected with the determination of specific competences (Filipkowska et al., 2004; Whiddett & Hollyforde, 2003).

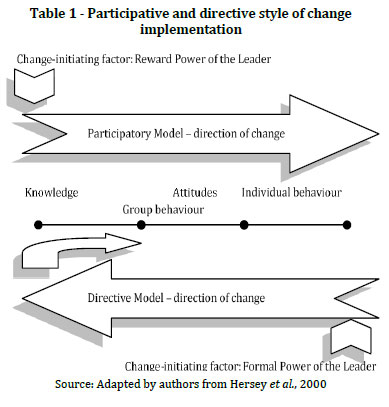

The value of the participative approach is featured extensively in literature on competence management implementation. However the directive approach is in many cases equally effective, recognising the contribution of external experts as a key part of a fundamentally different approach to the process of implementing change in organisations. The directive approach involves decisions made predominantly by top management; and therefore it is more accurate to replace the term “expert approach” with “top-down approach”. This duality is found in all aspects of organisational change, as well as in the distinctive features of participative and directive approaches to competence management implementation (Hersey et al., 2000, p. 390 – 392) (see Table 1).

Participatory cycles of change as well as implementing change/competence management in an organisation starts with group leaders exercising their influence, be it by referent power, reward power, or expert power. This in turn affects and modifies attitudes and behaviour as well as capability and knowledge. This type of change implementation is recommended in situations requiring positive attitudes, and with employee consent expressed at the onset. The elements of a directive approach may also be found in a bottom-up approach in the form of formalised behaviours that are novel and beneficial for change implementation. These activities are undertaken when positive changes can be observed on the level of individuals, and we intend to spread the positive effects

throughout the group.

The directive strategy of implementation is connected with leaders who exercise influence on employees by imposing on them an obligation to embrace new types of behaviour. Such directives (often in some form of official writing) create new conditions affecting the behaviour/conduct of the entire group and only then modify individual behaviour. Over time, attitudes change and employees start to learn more about reasons for their new behaviour (knowledge build-up), which in turn alters attitudes of employees. Change implementation in organisations with the use of a participative approach takes a relatively long time. However it is more likely that employees will embrace it more willingly (“our change”), finding internal motivation to embrace new behaviours. Employee accountability will emerge. A change implementation with the use of participative approach may take a shorter time yet may be perceived as externally “imposed”, and results will vary depending on the external motivation (reward/punishment). Employees will attempt to transfer accountability to their superiors.

The process of implementation: how to implement competence management on the basis of a participatory or a directive approach

Certain universal stages in competence management implementation can be distinguished (Sidor-Rzadkowska, 2006, p.33-34). Typically, a directive approach features a four-stage project implementation:

1. Establish the mission statement /company values

2. Establish base and organisation-specific competencies

3. Deploy competencies according to the formal structure of the organisation

4. Evaluate employees

In practical terms, the first three stages do not require employees’ participation, as at these stages the decisions are made in groups of top managers or within the HR Department. If the path of decision-making is well-defined and the circle of decision-makers is unequivocal, then the project has a chance of being implemented effectively and according to schedule.

Problems may appear at this stage when employees are likely to display pervasive and wide-ranging passive resistance (e.g., all employees who are also trade union members hand in empty evaluation sheets).

Organisations with authoritarian or strongly hierarchical management culture will order their employees to carry out the activities relevant at stage four, leaving aside considerations of employee attitudes towards the evaluation system or the degree of employee approval of changes.

However, often implementation carried out in line with a directive model causes the evaluation system to be regarded as “red tape”, an activity that has to be done only to preclude possible repercussions. Often the system itself does not foster the development of organisations. Conversely, it may at times generate negative attitudes in employees, who may consider the implemented system to be a tool of punishment or manipulation.

Typically, the participatory approach consists of four phases of yet a different character:

1. Job Description – realisation of tasks

2. Job Description – competencies indispensable for the realisation of tasks

3. Evaluation of Level of Competencies Development

4. Personal Evaluation/Development Interviews

The above-presented models overlap in two aspects, namely, they both feature four stages, and one of the stages is nominally the same.

A notable distinguishing feature of the second model rests in the fact that it involves the participation of employees at the first stage. It rests on the assumption that employees are best-suited to describing the scope of tasks and responsibilities entailed in their job. This approach – involving job descriptions produced by employees and subsequently reviewed and endorsed by their direct superiors – appears to be the best option, in particular in organisations that employ specialists with specific and advanced qualifications.

A job description including competencies (Stage 2) is also generated by employees and subsequently endorsed by their superiors. A new quality at this stage is that of

the description of specialist competencies drawn up for the organisation. Indeed, the description of specialist competencies truly reflects the range of tasks in a given organisation.

Overall, compared to the directive approach, a project carried out with a participative approach:

- is of longer duration

- incurs more cost (e.g., costs of training)

- is more time-consuming for employees

However, the benefits of the participatory approach appear to outweigh the costs. The main benefits include:

- change in the attitudes of employees and internalised acceptance of

the evaluation system.

- stronger (internal) organisational motivation to evaluate staff and for staff to attend evaluation interviews

- the organisation acquires real-life insight into tasks performed by employees and ways in which work is carried out

- knowledge of the type and level of competence development needed for the realisation of tasks at a level required by the organisation

As in the directive model, the participatory approach may produce negative results for the organisation. However, the source of negative effects lies not so much in the methodology of the project as in inappropriate internal public relations actions relating to the project.

The third option – a combination of both – looks attractive (and in practice was used by both case examples studied, as described below). However, there are substantial risks, and these have to be noted and understood as follows:

- employees do not comprehend objectives of the project (“it was something dreamed up at the Board of Managers Meeting”);

- difficulties in persuading employees to describe specialist competences;

- drawing an equation between the project and the “highest command level” or particular interests of the HR Department (attitude of: this is not “our” project, it is “theirs”);

- tendency to shift responsibility for the project and ensuing activities to external consultants if they are being used (which increases project costs and dilutes accountability in the organisation).

Selection of the method of competence management implementation in an organisation

A series of factors have to be considered prior to making a decision about the right method of competence management implementation. The most important include available resources of time and finances, degree of specialisation and complexity of tasks carried out by employees, prevailing organisational culture, acknowledged ways of formulating strategies. Each of these elements is presented below (Table 2).

Another crucial consideration in deliberating over the method of competence management implementation is the degree to which specialisation of tasks will be carried out by employees. The participative approach will yield more benefits in organisations with a prevalence of so-called “knowledge workers” who typically display a strong need for autonomy and want to be in control of their work. Therefore, by engaging these workers at all stages of the project, their needs will be fulfilled (Davenport, 2007). As the competence model requires the description of specialist competencies of knowledge workers, these workers have to be involved in the conceptual work, as only they can accurately identify the range of knowledge to be quantified (Rosinski, 2007; Filipkowska, 2004).

It is important to note that in large power distance cultures, organisations may not be suitable for participative competence management implementation. Subordinates who acknowledge and respond to autocratic or paternalistic power will avoid expressing opinions that diverge from the opinions of their direct and indirect superiors, and so a diversity of perspectives is sometimes not gained (Hofstede, 2000; Sikorski, 2002; Trompenaars & Hampden-Turner, 2002; Cameron & Quinn, 2003).

Additionally, organisations that tend to operate on a top-down basis in all activities are much more likely to comfortably embrace the top-down approach to competencies, and those that are used to being consulted on all aspects of organisation practice are much more likely to embrace the bottom-up approach (Krawiec, 2003; De Wit & Meyer, 2007).

Competence management implementation in Bank A using the directive method

Implementation objectives

The objective behind competence management implementation in Bank A was to provide mechanisms for monitoring and development of human resources in line with the strategic objectives of the organisation.

Schedule

Implementation commenced after the Board of Managers of bank A granted permission. A pilot programme was carried out earlier that supported the relevance of methodology and tools to achieve defined objectives.

Team

The team in charge of the project implementation consisted of three employees of the HR Department; and they were supported by a group of 40 coordinators employed across all parts of the bank.

Reasons for adopting the directive approach

A decision to adopt the directive approach stemmed from the intention to ensure the highest possible engagement with employees and acceptance of the project results.

In spite of the fact that the approach was directive, it became clear at an early stage that universal buy-in was essential. A key reason also was the fact that a majority of jobs at Bank A require highly specific, expert knowledge. In most cases, only the people in these jobs or their direct superiors are able to correctly quantify the competence requirements involved. Hence, it did not seem useful to have an external company provide a competence description.

Activities undertaken at subsequent stages of the project

This project of competence management implementation encompassed three areas of operation: conceptual work on project methodology; preparation and execution of a series of training and development activities to prepare employees for participation in the project; and a design of information systems to support the process of competence-based professional development. Even with the directive approach, it is important to acknowledge significant contributions made by employees to the project. These employees are considered co-authors of effects realised at later stages of the implementation (see Table 3)

Competence management implementation in Bank B using the directive method

Implementation objectives

The overall purpose was to ensure full buy-in and ownership of both competencies themselves and also subsequent HR strategy, of which agreed and defined competencies would be the core. The priority was to ensure that stated competencies were identified by staff; and this set the tone and structure for the participative approach chosen.

Schedule

The process had to be resourced, and this meant that both the schedule and proposed implementation method had to be agreed on with the governor of Bank B. Following this, the twin priorities that drove the schedule were sufficient time to ensure full participation and ownership and the need not to lose momentum and impetus.

Team

A project champion led the team. The role of project champion was to be the foundation of HR director as an energiser, facilitator, counsellor/counselling director, problem solver, reporter, monitor/reviewer and evaluator. A firm of consultants, working to a precise brief, facilitated the process by monitoring the following:

- the need for buy-in and ownership by all staff

- the need to produce a tangible and acceptable HR strategy

- the need to determine the competencies themselves

- the need to assess which competencies would be demanded for each job/grade/job family

Reasons for adopting the participative approach

As stated above, the overriding reason for adopting this approach was to ensure that both the process and also the overall HR strategy was bought into and subsequently fully owned by the staff of the bank. There was the additional motivation that some highly valuable, qualified and sought after staff had excellent technical skills and knowledge (e.g., PhD in economics), but lacked softer and (especially) ‘people’ skills. These skills would have to be agreed upon and written into the competency demands and frameworks, as well as job descriptions/person specifications at points in the implementation stages.

Activities undertaken at subsequent stages of the project

The priority was to ensure that everything was implemented and evaluated, while ensuring that competencies remained at the centre both of HR strategy and also HR activities. The additional objective was to ensure that what was agreed upon formed part of a process capable of allowing maintenance, review, upgrade, development and advancement, as and when circumstances dictated or allowed (see table 4).

Once the project had been agreed, resourced and commissioned, the process had to be begun. This involved full consultation with all groups and categories of staff and their representatives, including recognised trade unions. It was also essential to be able to demonstrate that this would lead to delivering an HR and HRD strategy capable of being placed at the heart of all HR priorities, drives, activities and practices, including:

- job descriptions and personal specifications;

- job and work analysis and evaluation;

- grade and graded work, task and expertise definitions;

- recruitment and selection;

- employee and career development, including promotions;

- performance appraisal;

- reward strategies;

- employee relations;

- organisation development;

- the promotion of equality and fairness of treatment and opportunity.

Findings and conclusions

The literature and the case examples indicate key findings which can be classified as risks in both approaches and longer term issues.

Risks

Both approaches entail certain risks. Presented below are examples of risks that may occur during the implementation of each model, along with suggestions on how to minimise these risks.

The participative approach

The key risk in the participative approach is that staff have widely varying opinions on required competencies. Especially,

those competencies relating to their own jobs are critical and of great value, and therefore to be guarded and protected; and so it is essential that project leaders engage with all staff as early as possible and describe the method for identifying and defining competencies, and assuring staff that theirs are covered.

Lack of cohesion in profiles of similar jobs is also an issue. A method for the definition of job families and competence clusters is required, and again staff need to be briefed and reassured on these points.

A competency matrix therefore does not have to encompass all the groups of jobs in an organisation. It does require a way of classifying all of competencies present, and a way of communicating these to everyone involved. Staff engagement is paramount at all levels, and this is dependent on effective communication, as follows:

- communicate objectives of the project clearly;

- involve leadership in the organisation in the process of communicating

objectives and milestones of the project; - inform the employees of ongoing undertakings, even if these do not affect them directly; use all available channels of communication for this matter (Intranet, company’s newsletter, and briefings) ;

- inform employees about project-related undertakings/activities scheduled for the nearest future; remind them of benefits;

- react promptly to any signal of information deficit; ensure that employees may easily access people in charge of the project;

- remain open to critiques and use them to enhance the process implementation;

- respond promptly if there are difficulties in making decisions or if the process gets delayed, again using all forms of communication as above.

The directive approach

The directive approach also has risks which include employees may reject the entirety of the project if it is imposed from the top. Even if a prescriptive approach is used, it is therefore essential that resistance is identified and managed. This means that:

– there has to be no doubt that the approach is to be implemented, and this in turn means that the steering group or project manager needs the full backing of the organisation and the authority to implement the programme in all situations;

– opinion leaders, middle managers and staff and employee representatives have to be engaged as part of the initial groundwork;

– real concerns have to be identified and addressed at the earliest possible stage.

Employees do not understand objectives of the competence management implementation. This can generate gossip about (real, potential or fictional) staff reductions or other changes detrimental to the employee status quo. Again this requires constant communication and the ability to meet with and address the concerns of groups or individuals that raise them.

It is also essential that the top-down approach does not get bogged down in its own bureaucracy and administrative processes. These processes need to be transparent and driven by the project leader or team and related closely to the timelines prescribed.

Longer-term implications

Irrespective of which approach is adopted for competence management implementation. The fact that an approach was determined and implemented brings about both organisational change and also collective and individual development. Drawing on both the literature and the above case studies, the process appears to have a number of clearly defined stages:

- Stage 1. Increased training and development.

- Stage 2. Optimisation of costs and benefits of training and development.

- Stage 3. Creating extensive development systems; frequently of a flexible and strategic cafeteria type

- Stage 4. Identification and implementation of job, career, professional/occupational and organisation development activities for all.

- Stage 5. Underpinning the whole with regular and participative appraisals.

- Stage 6. Promoting coaching and informal consulting, and creating the conditions required for wider organisation development (e.g., through project work, secondments, mentoring systems).

All of this requires commitment and resources, including top management commitment, whether the top-down or bottom-up approach is implemented. It also means that HR functions change. Much operational HR work has to be filtered down to middle and junior managers and supervisors, and staff especially have to participate actively in their own collective and individual development. HR shifts, therefore, in turn from an operational and task driven function, to a strategic function, aligning organisation development with business strategy.

References

Belkadi, F., Bonjour, E. & Dulmet, M. (2007). Competency characterisation by means of work situation modelling. Computers in Industry, 58(2), 164-178. [ Links ]

Bergenhenegouwen, G. J., Ten Horn, H. F. K. & Mooijman, E. A. M. (1997). Competence development – a challenge for human resource professionals: Core competences of organisations as guidelines for the development of employees. Industrial & Commercial Training, 29(2), 55-62. [ Links ]

Berio, G. & Harzallah, M. (2007). Towards an integrating architecture for competence management. Computers in Industry, 58(2), 199-209. [ Links ]

Boucher, X., Bonjour, E. & Matta, N. (2007). Competence management in industrial processes. Computers in Industry, 58(2), 95-97. [ Links ]

Cameron, K. S. & Quinn, R. E. (2003). Kultura organizacyjna – diagnoza i zmiana. Krakow: Oficyna Ekonomiczna. [ Links ]

Coase, R (1937, November). The nature of the firm. Economica, 4(16), 1937, 386-405. [ Links ]

Cotora, L. (2007). Managing and measuring the intangibles to tangibles value flows and conversion process: Romanian Space Agency case study. Measuring Business Excellence, 11(1), 53-60. [ Links ]

Davenport T. H. (2007). Zarzadzanie pracownikami wiedzy. Warszawa: Wolters Kluwer Polska. [ Links ]

De Wit, B. & Meyer R. (2007). Synteza strategii. Tworzenie przewagi konkurencyjnej przez analizowanie paradoksów. Warszawa: PWE. [ Links ]

Filipkowska, A., Jurek, P. & Molenda, N. (2004). Pakiet kompetencyjny. Metodologia i narzedzia. Warszawa: Wydawnictwo ProFirma. [ Links ]

Filipowicz, G. (2004). Zarzadzanie kompetencjami zawodowymi. Warszawa: PWE. [ Links ]

Hagan, C. M. (1996). The core competence organisation: Implications for human resource practices. Human Resource Management Review, 6(2), 147-164. [ Links ]

Hamel G. & Prahalad, C. K. (1994). Competing for the future. Boston: Harvard Business School Press. [ Links ]

Harzallah, M., Berio, G. & Vernadat, F. (2006). Analysis and modelling of individual competencies: Toward better management of human resources. Systems, Man & Cybernetics, 36(1), 187-207. [ Links ]

Hersey, P., Blanchard, K. H. & Johnson, D. E. (2000). Management of organisational behavior: Leading human resources, 8th edition. Upper Saddle River: Prentice Hall. [ Links ]

Hitt, M. A. & Ireland, R. D. (1985). Corporate distinctive competence, strategy, industry and performance. Strategic Management Journal, Vol. 6, 273–293. [ Links ]

Hofstede, G. (2000). Kultury i organizacje. Zaprogramowanie umyslu. Warszawa: PWE. [ Links ]

Javidan, M. (1998). Core competence: What does it mean in practice. Long Range Planning, 31(1), 60-71. [ Links ]

Knudsen, M. P. (2006). Patterns of technological competence accumulation; A proposition for empirical measurement. Industrial & Corporate Change, 14(6), 1075-1108 [ Links ]

Krawiec, F. (2003). Strategiczne myslenie w firmie. Warszawa: Difin. [ Links ]

Kwangseek, C., Booth, D. & Hu, M. (1997). Production competence and its impact on business performance. Journal of Manufacturing Systems, 16(6), 409-421 [ Links ]

Marino, K. E. (1996). Developing consensus on firm competencies and capabilities. Academy of Management Executive, 10(3), 40-51. [ Links ]

Morone, J. (1993). Wining in high tech markets. Boston: Harvard Business School Press. [ Links ]

Oleksyn, T. (2006). Zarzadzanie kompetencjami. Teoria i praktyka. Krakow: Oficyna Ekonomiczna [ Links ]

Penrose, E. T. (1959). The Theory of the Growth of the Firm. New York: John Wiley. [ Links ]

Prahalad, C. K., Hamel, G. (1990, May-June). The core competence of the corporation. Harvard Business Review, 68(3), 79-91 [ Links ]

Sanchez, R. (2001). Knowledge management and organisational competence. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

Schumpeter, J. A. (1934). The theory of economic development. Boston: Harvard University Press. [ Links ]

Seppänen, V. & Skaates, M. A. (2001). Managing relationships and competence to stay market-oriented: the case of a Finnish contract research organisation. AMA Winter Educators’ Conference Proceedings, Vol. 12, 98-107. [ Links ]

Sidor-Rzadkowska, M. (2006). Kompetencyjne systemy ocen pracowników. Warszawa: Wolters Kluwer Polska. [ Links ]

Sikorski, Cz. (2002). Kultura organizacyjna. Warszawa: Wydawnictwo C. H. Beck. [ Links ]

Teece, D. J., Pisano, G. & Shuen, A. (1990). Firm capabilities, resources, and the concept of strategy. Berkeley: Haas School of Business, University of California. [ Links ]

Trompenaars F. & Hampden-Turner, Ch. (2002). Siedem wymiarów kultury. Znaczenie róznic kulturowych w dzialalnosci gospodarczej. Kraków: Oficyna Ekonomiczna. [ Links ]

Vloeberghs, D. & Berghman, L. (2003). Towards an effective model of development centres. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 18(1), 511-540 [ Links ]

Walsh, S. & Linton, J. D. (2002). The measurement of technical competencies. Journal of High Technology Management Research, 13(1), 63-86 [ Links ]

Whiddett, S. & Hollyforde S. (2003). Modele kompetencyjne w zarzadzaniu zasobami ludzkimi. Krakow: Oficyna Ekonomiczna. [ Links ]

Zülch, G. & Becker, M. (2007). Computer-supported competence management: Evolution of industrial processes as life cycles of organisations. Computers in Industry, 58(2), 143-15. [ Links ]

Article history

Submitted: 30 May 2013

Accepted: 21 November 2013