Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Acessos

Acessos

Links relacionados

-

Similares em

SciELO

Similares em

SciELO

Compartilhar

Tourism & Management Studies

versão impressa ISSN 2182-8458

TMStudies vol.10 no.1 Faro jan. 2014

TOURISM - SCIENTIFIC PAPERS

Influential factors in the competitiveness of mature tourism destinations

Os fatores que influenciam a competitividade dos destinos turísticos maduros

Margarida Custódio SantosI; Ana Maria FerreiraII; Carlos CostaIII

IUniversity of the Algarve, School of Management, Hospitality and Tourism, Campus da Penha, 35, 8005-139, Faro, Portugal, mmsantos@ualg.pt

IIUniversity of Évora, Department of Sociology, 7004-516, Évora, Portugal, amferreira@uevora.pt

IIIUniversity of Aveiro, Department of Economics, Management and Industrial Engineering, GOVCOPP, 3810-193, Aveiro, Portugal, ccosta@ua.pt

ABSTRACT

With a few exceptions, the traditional models that aim at identifying the factors that influence the competitiveness of tourism destinations are very difficult to operationalise because they need a large number of indicators to inform the concepts. This paper presents a different approach that postulates that researchers should try to identify the specific factors that impact competitiveness of tourism destinations according to the stage of the destinations life cycle. With the aim of identifying these specific factors, an extensive literature review was undertaken, focusing in particular on the papers that explicitly recognised that the destinations under analysis in the studies were in the mature stage of their lifecycle.

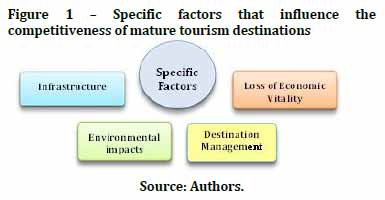

From the literature review, we concluded that the specific factors able to negatively influence the performance of mature tourism destinations can be grouped into four areas. The first area concerns the deterioration of the destinations infrastructure; the second is related to the destinations management, namely the lack of a shared strategic vision among stakeholders; the third area is associated with the loss of economic vitality in the destinations; finally, the fourth area includes the impact of tourism development over the years on the territory, specifically social, environmental and cultural impacts.

The results obtained from the empirical study allow us to conclude that the lack of environmental problems, not being overdeveloped in terms of construction and having maintained authenticity are all perceived by tourists as more important for the competitiveness of tourism destinations than factors normally considered more relevant, such as prices and the quality of accommodations.

Keywords: Competitiveness, specific factors, mature tourism destinations.

RESUMO

Muitos dos modelos de competitividade dos destinos turísticos apresentados até ao momento, para além de serem modelos genéricos que visam principalmente identificar os diferentes fatores que influenciam a capacidade de competir dos destinos turísticos e de serem muito difíceis de operacionalizar devido ao elevado número de indicadores que comportam, não equacionam a possibilidade de introdução de elementos explicativos da performance dos destinos.

Uma abordagem diferente propõe que se identifiquem os fatores específicos suscetíveis de influenciar a competitividade dos destinos turísticos de acordo com a fase de desenvolvimento em que se encontram. Com o objetivo de identificar esses fatores específicos capazes de influir na capacidade de competir dos destinos turísticos maduros foi efetuada uma extensa revisão da literatura, privilegiando artigos que de forma explícita referissem que os respetivos destinos se encontram na fase de maturidade.

Decorrente da revisão da literatura efetuada verificou-se que os fatores suscetíveis de influenciar negativamente a capacidade de competir dos destinos turísticos em fase de maturidade se podem agrupar em torno de quatro grandes áreas. A primeira área reporta-se à deterioração das infraestruturas do destino, a segunda relaciona-se com a gestão dos destinos, nomeadamente a falta de visão estratégica com que são conduzidos, a terceira área refere-se a alguma perda da vitalidade económica desses destinos e a quarta grande área identificada diz respeito aos impactos que a atividade do turismo teve sobre o território, nomeadamente os impactos ambientais, sociais e culturais.

Os resultados obtidos no estudo empírico permitem-nos concluir que a ausência de problemas ambientais, não apresentar excesso de construção e ter mantido a autenticidade são percecionados pelos turistas como mais importantes para a competitividade dos destinos turísticos em fase de maturidade do que fatores habitualmente considerados mais relevantes, como os preços e a qualidade do alojamento.

Palavras-chave: Competitividade, fatores específicos, destinos turísticos maduros.

1. Introduction

The concept of competitiveness has been analysed and discussed across different disciplines, mainly in economics, management, and political sciences. Each of these disciplines has offered distinct perspectives on defining, understanding and measuring this concept. The complexity and scope of the competitiveness have thus contributed to the difficulty in developing a clear and universally accepted definition in the research community. However, we can identify two different broad perspectives in conceptualising and evaluating this concept. On the one hand, as a relative concept, there have been attempts to evaluate the competitiveness of one destination in relation to its competitors. On the other hand, as a multidimensional concept, there have been attempts to develop models that encompass the factors that explain the variable capacity of destinations to compete (Dwyer & Kim, 2003; March, 2004).

More recently, Wilde and Cox (2008), Enright and Newton (2005) and Dwyer and Kim (2003) have argued that researchers should make efforts to identify the underlying specific factors that influence the capacity of the destination to compete according to their stage of development in the destinations life cycle. In this paper, we attempt to characterise mature tourism destinations by identifying the factors that might have a negative impact on these destinations´ competitiveness (Bieger, 2002; Seaton and Alford, 2001; Go & Govers, 2000). After identifying these factors, this paper aims to assess the importance given in tourist demand to each of the factors identified and to determine whether different methodological approaches have influenced the results obtained.

2. The competiveness of tourism destinations

In regards to gauging the competitiveness of tourism destinations, it is possible to identify a vast body of work, the most well-known being the model developed by Ritchie and Crouch (2003). Although this is considered the most complete model developed to date (Mazanec et al., 2007; Hong, 2008; Dwyer & Kim, 2003), one of its weakness lies in that it is a purely descriptive model. According to Mazanec et al. (2007), regardless of how elaborate the concept-definition systems may be, they cannot provide explanations for observable phenomena. Other weaknesses include the difficulty in obtaining data that allows us to assess all the factors and the absence of a weighting system to indicate the order of importance of the different factors and elements identified.

In order to overcome these weaknesses, the authors Dwyer and Kim (2003) developed an alternative model that, despite containing many of the factors and elements identified by Ritchie and Crouch (2003), is different mainly in that it explicitly acknowledges tourist demand as an influential element in destination competitiveness. Another significant difference lies in the fact that this model expressly acknowledges that competitiveness should not be viewed as the final goal of a destination development policy, but rather as an intermediate objective, enabling the local, regional or national community to attain socio-economic prosperity.

Mazanec et al. (2007) take the view that the considerable research conducted into the concept of destination competiveness has identified a large number of factors that shape the concept, including factors that facilitate or provide on the supply side as well as factors that create preferences on the demand side. Nevertheless, the efforts made to date have been unable to provide a response regarding the type of mechanism that channels all these factors into one construct, termed destination competitiveness. According to the authors, the scientific community should focus its attention on developing models that establish a causal relationship between the factors identified as being part and parcel of destination competiveness and destination performance, thereby allowing for the implementation of measures to determine which changes should be made to boost the success of tourism at a given destination.

The authors Wilde and Cox (2008) argue that the concept of tourist destination competitiveness and understanding the importance of the factors that inform the concept should be linked to the stage of development and evolution of the tourism destination in question. This view is also highlighted by Mazanec el al. (2007), Dwyer and Kim (2003), and by Enright and Newton (2005), who state that destinations should adopt a more specific approach adapted to the destination in question, in order to add value to and develop the destinations competitiveness, paying special attention to those factors that determine the competitiveness of a given destination at different stages of its development.

3. Identifying the specific factors capable of influencing competiveness

A considerable number of research studies have suggested that tourism destinations undergo a cycle of development over time, but that these changes are not always positive ones and may even lead to the destinations decline (Buhalis, 2000; Agarwal, 1997; Haywood, 1986; Hovinen, 1982; Butler, 1980; among others).

Hovinen (1982) was one of the first researchers to apply the destination lifecycle model proposed by Butler (1980), concluding that tourism development in Lancaster County, Pennsylvania fit perfectly within the first three stages of Butlers model. However, the destination in question provides no empirical evidence that would allow us to prove the existence of the consolidation and stagnation stages. The development at this particular destination diverges significantly from the characteristics of the consolidation and stagnation stages, evidencing characteristics of both stages at the same time, which is why Hovinen (1982) suggests merging them into one single stage, which he calls the maturity stage.

Based on the empirical evidence gathered by Hovinen (1982), Foster and Murphy (1991), Getz (1992), Agarwal (1997) and Briossoulis (2004), we can say that destinations at the maturity stage may simultaneously show characteristics of the consolidation, stagnation, decline and recovery stages discussed by Butler (1980).

On the basis of our extensive review of the literature that states explicitly that the destination in question is at the maturity stage, as well as on the research conducted by Wilde and Cox (2008), we can conclude that there are specific factors that may adversely affect the competitiveness of mature tourism destinations. This includes the lack of maintenance and modernisation of the existing infrastructure, difficulty in creating a shared vision as to how the destination should develop, difficulty in getting the different stakeholders to cooperate, the loss of the destinations economic vitality and, finally, social, cultural and environmental impacts on the destinations as a result of their involvement in tourism over the years (Figure 1).

3.1 Lack of maintenance and failure to modernise infrastructure

At mature destinations, basic infrastructure development does not always keep pace with the speed and level of effectiveness needed in the construction of accommodations and residential units (Buhalis, 1999; Priestley & Mundet, 1998; Priestley, 1995; Ioannides, 1992; Smith, 1992). According to Ritchie and Crouch (2003), this may hinder the competitiveness of the destination on two fronts. First, a tourists perception of the destinations infrastructure may be a factor in choosing or rejecting that particular destination and, second, the quality of the infrastructure affects the level of effectiveness and efficiency of the organisations that carry on or intend to carry on their activities at the destination.

According to Mo et al. (1993), tourism infrastructure comes second to the atmosphere at the tourism destination as the factor that exerts the greatest influence on the tourists experience. Given the importance that the infrastructure holds in the tourists experience as well as the business opportunities it can offer to the private sector (Dwyer & Kim., 2003; Mo et al., 1993; Murphy et al., 2000), it can only be expected that tourism destinations should attach special emphasis to their ongoing development and modernisation.

However, Twining-Ward and Baum (1998) argue that tourism destinations recognise the need to innovate only when signs of decline have already appeared and, in this situation, many destinations invest in diversifying the products they offer in order to stave off this decline. This diversification strategy includes building golf courses, spas, conference rooms, casinos, marinas, and developing natural and cultural tourism (Rodríguez-Díaz & Espino-Rodríguez, 2008; Faulkner & Tideswell, 2005; Vera Rebollo & Ivars Baidal, 2003; Briassoulis, 2004; Agarwal, 2002; Foster & Murphy, 1991).

The infrastructure referred to above is built to attract tourists with greater spending power and to reduce seasonal tourism (Markwick, 2000; Briassoulis, 2004), yet this type of development may accentuate some of the adverse environmental repercussions, namely by aggravating conflicts related to water use or worsening coastal erosion (Malvárez García & Pollard, 2003; Ioannides, 2001). Besides environmental repercussions, the construction of this type of infrastructure does not always help these destinations to stand out from their most direct competitors, as it is easy to imitate and the destination itself becomes even farther removed from its original geographical features (Cooper & Jackson, 1989; Butler, 1980).

In regards to accommodation, the first and biggest flaw in mature tourism destinations is exceeding the available capacity, whether of official establishments or unofficial beds (Faulkner & Tideswell, 2005; Briassoulis, 2004; Rebollo & Baidal, 2003; Formica & Uysal, 1996; Ioannides, 1992). Secondly, the factors that make these accommodation units unsuitable for the demands of todays tourists are the absence of leisure and well-being facilities, and the lack of care taken in the architecture, design and surroundings, which are very often characterised by large-scale construction where very little heed has been paid to aesthetics (Aguiló et al., 2005; Priestley & Mundet, 1998).

3.2 Environmental repercussions

It is widely recognised that tourism has both positive and negative effects on the environment, and there is a large body of research work that has discussed this theme. The best resources we found on this relationship are the following works: Gössling, 2002; Sun and Walsh, 1998; Hunter and Green; 1995; OECD, 1980; and Pigram, 1980. In this section, we will examine how the impact of tourism on the environment makes itself felt at mature tourism destinations and how it is able to influence the competitiveness of such areas.

According to the OECD (1980), tourism may have many repercussions in the environment, including:

Sound, air, water and area pollution

Loss of natural landscapes (agricultural and grazing land) and the inaccessibility of some areas

Destruction of flora and fauna

Deterioration of built-up areas

Crowding as a result of excessive concentration

Conflict as a result of changes in the resident populations way of life

Abandonment of traditional activities, which are unable to compete with tourism in terms of existing resources

Apart from the repercussions mentioned in the OECD Report (1980) and evident in the literature, we have noted that tourism development may also have a very significant impact on the aesthetics of the areas where it appears, which Inskeep (1991) terms visual pollution. This usually stems from (i) the construction of accommodation units and other infrastructures that are very poor in architectural and design terms and do not blend in with the surroundings, (ii) the use of unsuitable building materials for facades, (iii) inadequate infrastructural planning, (iv) unsuitable landscaping arrangements, (v) the use of large and aesthetically poor advertising signs, (v) the proliferation of telecommunications and energy support structures, (vii) the obstruction of panoramic views by buildings and (viii) the poor upkeep of buildings and the surrounding areas.

Mature tourism destinations have been exposed to tourism development for a greater period of time and, as Haywood (2005) states, the tourism industry makes many demands on the areas involved and may even lead to the depletion of such areas, since the development process and mass use, concentrated in terms of time and space, may compromise their attractiveness if the activities carried on in these areas are not properly managed and their load capacity is not respected.

Bearing in mind that todays tourists not only prize a well-preserved environment, without excess development and crowding and also maintaining high aesthetic standards, a failure to solve the problems related to adverse environmental impacts is a factor that may drastically reduce the competitiveness of the tourism destinations affected (Aguiló et al., 2005; Hu & Wall, 2005). As Milhalic (2000) points out, they will only be able to compete for tourists with less spending power, who are less demanding in terms of environmental aesthetics and quality. Consequently, the way tourism destinations are managed takes on vital importance and will be discussed in the following section.

3.3 Tourist destination management

Mature tourism destinations need to improve coordination and management to make them more diversified, so as to be able to compete with new tourism destinations that use new management models (Bieger, 2002). Knowles and Curtis (1999) call these destinations third-generation tourism destinations and state that this type of destination is characterised by a high degree of quality planning, control and specification. Bieger (2002) believes that the centralised management of these destinations confers major benefits with regards to the planning, financing and implementation of activities that are of interest to the destination in comparison to tourism destinations that are characterised by a high level of fragmentation at the decision-making level.

In parallel, there have been changes in terms of tourist demand, particularly towards a focus on the usefulness of the trip and the possibility of making reservations at increasingly later times, which makes the existence of a central distribution system indispensable. A further two aspects to be taken into consideration are the increase in customer demand for an optimised chain of services – that is to say, for all the elements of the product to be in harmony and guaranteed in terms of quality – and the need to provide customers with a much wider range of products (Bieger, 2002).

Traditionally, the organisations responsible for destination management (DMOs) have limited their activities to promoting the destination (Jamal & Jamrozy, 2006; Dwyer & Kim, 2003) and have not exerted enough control over the product and the way in which it is commercialised, as well as neglecting to develop new tourism products. Like Dwyer and Kim (2003) and Hassan (2000), Pechlaner and Tschurtschenthaler (2003) take the view that DMOs should also be facilitators with regards to marketing management. That is to say, in addition to promoting the destination, they should gather, process and publicise information about the characteristics, values and needs of the main market segments. This in-depth knowledge would enable a systematic focus on researching comparative advantages that, according to Pechlaner and Tschurtschenthaler (2003), lead to the development of new innovative tourist products that are able to satisfy the needs of the main segments of the market.

Faulkner and Tideswell (2005) examined the necessary measures that a mature tourist destination should take to enhance its competiveness and avoid going into decline, concluding that it is essential to involve all stakeholders in the process. This broader set of participants reflects the need for a holistic approach to destination management and planning and also recognises that social and environmental aspects are as important and merit as much attention as economic aspects. In addition, this broader level of participation makes it possible to develop a shared vision about the future of the destination. This shared vision creates a reference point for the individual actors operating at the destination.

Buhalis (2000) specifically states that the greatest challenge posed to DMOs is that of having the necessary leadership capacity to develop innovative tourism products by creating, at a local level, partnerships which are capable of offering unique tourism experiences to prospective visitors.

3.4 Economic vitality

The loss of economic vitality as a characteristic of mature tourism destinations derives essentially from exceeding the accommodation capacity, a fall in the number of tourists or reducing the prices charged in order to attract a larger number of tourists. The price-reduction strategy is mostly seen at destinations that are highly dependent on powerful intermediaries capable of influencing tourist flow (Aguiló et al., 2005; Knowles & Curtis, 1999; Priestley & Mundet, 1998; Twining-Ward & Baum, 1998; Cooper, 1990; Ioannides, 1992).

Correcting the flaws referred to in the preceding points – that is, by careful construction and maintenance of the infrastructure, solving environmental and aesthetic impact problems, and managing the destination in a way that is capable of creating a shared vision of how it will develop – may help to attract tourists with greater spending power and less price sensitivity, thus contributing also to the economic sustainability of the region as a whole.

The development of innovative tourism products that take into consideration the specific needs of given market segments and are capable of affording unique, authentic tourism experiences may significantly enhance the competitiveness of mature tourism destinations. Unlike tourism products developed in the past, which actually added to adverse repercussions on the environment, these innovative products should help mitigate the existing problems and add to the sustainability of tourism destinations, allowing them to stand out from their competitors.

4. Methodology

The objectives of this paper deal, on the one hand, with the identification of the specific factors that are likely to adversely affect the competitiveness of tourism destinations in the maturity stage and, on the other hand, assessing the importance given by the tourism demand to factors that potentially influence the competitiveness of these tourism destinations in the maturity stage. To this end, we created a scale that combines factors normally used to measure the competitiveness of tourism destinations with factors identified in the literature review in Section 3, which specifically focus on tourism destinations in the maturity stage. The specific factors identified of destination management and loss of economic vitality are not included in the scale, since in a pre-test the tourists surveyed evidenced some difficulties in deciding on these aspects.

At the same time, this paper also aims to assess to what extent the form of the questions could influence results, i.e., if the use of a quantitative methodology (closed-ended questions) or a qualitative method (open-ended questions) influences the importance attributed to different factors or even reveals the existence of factors that are not usually taken into consideration.

In order to achieve the outlined objectives, a questionnaire was prepared that included two open-ended questions, in which respondents were asked to indicate first the characteristics that in their opinion make a tourism destination attractive and then the features that make a tourist destination unattractive. The third question consisted of a scale with a total of twenty items (Table 1), which included the factors identified in accordance with the literature review.

Data collection was carried out in August and September 2010 at Faro International Airport and a total of 392 valid responses were obtained. The data obtained from the two open-ended questions were subjected to content analysis using the SPSS Text Analysis for Surveys 3.0 that enables the development of categories.

For the closed-ended question, a Likert scale of five points was used from 1 "unimportant" to 5 "very important" to assess the importance of each item. The Cronbach's alpha coefficient for the scale was 0.809, indicating that the internal consistency and validation of the instrument is good.

5. Results

5.1 Sample characterisation

The majority of respondents or 53.6% are men, and 46.4% are women, mostly residing in the UK (38.6%), followed by Germany (27.1%), the Netherlands (14.8%) and Ireland (7.7%). The average age stands at 43.1 years. The age group between 45-64 years is the most significant, followed by the age group of individuals between 25 and 44 years. With regards to the education of the respondents, it was found that most had higher education, 62.2%, and only 1.3% of respondents had only a primary education. In specific, 22.2% had completed a professional course and 13.5% had only completed their secondary education. The most frequently mentioned motivation for the trip was leisure (98.2%), only 1.8% were in the destination for professional reasons, 3.1% for health reasons and 11.3% were visiting family and friends.

5.2 Factors influencing the competitiveness of destinations: Qualitative analysis

Categories were extracted by grouping words and expressions in answers into broader sets, with the result that the words or expressions associated with the weather were mentioned by the largest number of respondents, i.e., of the 392 individuals in the sample, 257 respondents (corresponding to 65.5% of the sample) mentioned the weather. The second most mentioned category was the one that encompasses references to natural attractions, with 245 respondents (62.5%) mentioning a word or phrase that refers to that category. To a lesser extent, respondents mentioned words or phrases associated with cultural attractions (32.1%), social attractions (28.3%) and infrastructures (20.2%). The remaining categories were mentioned by less than 20% of respondents, i.e., the cleanliness category was mentioned by 14.0% of respondents, the specific factors category by 13.5% of respondents, the global trends category by 12.8%, and location was mentioned by 10.7% of the sample.

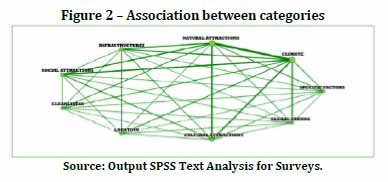

The use of SPSS Text Analysis for Surveys enables us to verify the associations between the categories mentioned, i.e., it is possible to determine that a respondent mentioned simultaneously words or expressions that refer to the x category and to the y category. The strength of the association is given by the frequency, i.e., the association between two categories is more significant if a larger number of respondents mentioned both categories simultaneously. Figure 2 shows that there is a strong association between the categories natural attractions and the climate and between the natural attractions and cultural attractions, and three triangles can also be seen. The first is formed by the categories natural and social attractions and climate, the second by the natural attractions and cultural attractions and the weather and a third by the infrastructures, natural attractions and the climate.

When the question was formulated in the negative, 62.5% of respondents mentioned words or phrases that were grouped in the category designated as specific factors, which gathers references to excessive construction, lack of maintenance of spaces and noise. The second category comprises references to the lack of cleanliness and the existence of garbage that were reported by 45.7% of respondents. The third category global trends, mentioned by 30.9% of respondents, contains expressions related to high prices and aspects associated with the lack of security. The fourth category social attractions brings together words that refer not only to the lack of friendliness of local residents but also to other tourists who frequent the destination, mentioned by 28.1% of respondents. The categories climate and infrastructures were mentioned respectively by 27.0% and 20.7% of respondents. The categories cultural attractions, natural attractions and location include words or phrases mentioned by less than 10% of respondents.

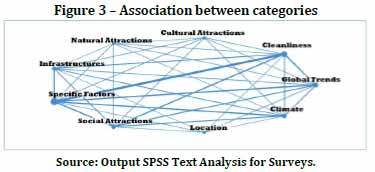

Figure 3 visually translates the associations established between the different categories. It is possible to detect a triangle formed by the category specific factors, which mainly includes the impacts of tourism development in the territory, the category cleanliness and the category global trends, which is strongly influenced by issues related to price and security.

The most common expressions relate to climate and were mentioned by 31.4% of respondents. However, if we add to this expression also the word sun and the expression pleasant climate, it was found that 64.8% of respondents consider the quality of the environment a decisive factor in the attractiveness of the destination. Then come words referring to the beauty of the landscape (23.7%) and beaches (23.5%), i.e., to the beauty of the natural resources of the destination, assuming that the respondents were referring only the natural landscape. The expressions to be potentially included in natural attractions were mentioned by 65.8% of respondents.

In fourth place appears the issue of overbuilding and the fifth most mentioned word expresses the importance of the impact of dirt on the attractiveness of tourism destinations. On the whole, the words that refer to these specific factors were mentioned by 63.5% of respondents and the question of cleanliness or lack of it by 52.7%.

The sixth most mentioned factor is concerned with the friendliness of the people with whom the respondents interact in the destination, be these the resident population, service providers or other tourists. If to this factor we join expressions that refer explicitly to the friendliness of the resident population, 27% of respondents consider this as having a significant influence on the attractiveness of destinations.

In seventh place comes the price, i.e., beyond climate, natural attractions, cleanliness, friendliness of the people and the fact that the destination is not overbuilt, respondents then consider the costs associated with the trip in the attractiveness of tourism destinations.

In tenth place comes the expression bad weather that reinforces the importance attributed to the climate, and eleventh and twelfth are two factors that refer back again to tourism over-development that may adversely affect the attractiveness of the destination, which is materialised here in the expressions too many people/tourists and noise.

Gastronomy comes in fifteenth in the attractiveness of the destination and is the most used word in the category cultural attractions, mentioned by 23.2% of respondents.

The words or phrases that refer to security appear at a surprising low rate given the importance that is attributed to security in the literature when this element is assessed through a quantitative methodology. However, expressed spontaneously, issues related to security appear only eighteenth in importance. Although this is not expected compared to results produced by other methods, this can be understood in that the evidence found in other research areas that used a combination of quantitative and qualitative methodologies.

The same analysis applies to some extent to the position assigned to accommodations, usually regarded as decisive. In spontaneous answers, the respondents did not ascribe to this a strong role in the attractiveness of the destination. One possible reason for this finding may be linked to the fact that in the 1960s and 1970s accommodations quality was relatively scarce in destinations. However, at present there is a huge number of destinations that provide a wide range of high quality accommodation and in some cases very poorly differentiated.

5.3 Factors influencing the competitiveness of destinations: Quantitative analysis

Items to assess the attractiveness of mature tourism destinations in the analysis had a varying number of responses, including items that were evaluated by all respondents (having a friendly and welcoming resident population) and others for which there was a greater difficulty in assessment as expressed by a greater number of respondents who chose not to evaluate the element. Regarding the item destination, no negative comments to present on social networks, it was found that a high number of respondents chose the option do not know/no answer.

Regarding the items that were considered most important in the choice of destination, there is the climate, security and friendliness of the resident population. Then follows the items no environmental problems and the existence of an attractive natural landscape. Only in sixth comes the quality of accommodations. The next four items are again related to the region and respective development. Is not overbuilt and has kept authenticity appear in seventh and eighth place. The existence at the destination of villages, towns and beautiful cities to visit and a well preserved and harmonious cultural (traditional) landscape follow in ninth and tenth place. These items are considered more important in choosing the destination than the existence of historical monuments and museums to visit because this factor appears only in sixteenth place.

The eleventh place is occupied by price, which is usually considered a decisive factor in the competitiveness of tourism destinations (Dwyer et al., 2000). The existence of a typical, good and varied gastronomy follows in twelfth place and two subsequent ranks (thirteenth – possible to obtain information on the Internet about the destination – and fourteenth – offers products that confer unique and memorable experiences) are occupied by factors that integrate global forces with greater ability to induce changes worldwide. The fifteenth place is occupied by an item that incorporates the environmental impacts identified as influencing the competitiveness of tourism destinations in the maturity stage. The item does not have negative comments on social networks appears only in seventeenth place; however, it is noteworthy that this factor has the highest standard deviation among the twenty factors in analysis, being indicative of widely divergent opinions among respondents.

The last three positions are occupied by the items existence of health and wellness equipment, measures to protect natural resources and events to attend. The item that was intended to assess the importance of measures to protect natural resources presents a comparatively modest result compared to the item that assessed the presence of environmental problems in the destination. This discrepancy in the evaluation can mean that tourists do not have a clear perception that the practice of certain actions, e.g., producing excessive waste, results in the emergence of environmental problems at the destination level. The item considered less relevant to the choice of a destination is the existence of events to attend, which usually incorporates factors assessing the attractiveness of tourism destinations.

5.4. Results of factor analysis

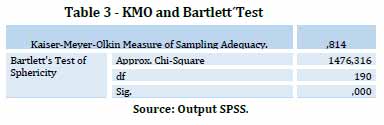

The results of the Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO) test was 0.814, which allows us to conclude that our data is appropriate to use in factor analysis. At the same time, the Bartlett's test of sphericity shows a value of 0.000, allowing us to reject the null hypothesis and conclude that indeed the variables under analysis are correlated (see Table 3).

Regarding the extraction method, we chose the method of principal components and varimax rotation, which aims to get a factor structure in which each of the original variables is strongly associated with only a single factor, thus allowing an easier reading of the results obtained (Maroco, 2003). To determine the number of principal components to retain, there are, according to Pestana and Gageiro (2008), different possible procedures: (i) the proportion of explained variance is greater than 60%, (ii) the variance of the components (eigenvalues) is greater than 1, and (iii) in the scree plot, the points in the larger slope are indicative of the number of components to retain. Thus – and in accordance with the second procedure – in our case six components or factors must be retained, since 56.7% of the total variance is explained.

The factors identified and shown in Table 4 corroborate the evidence found throughout our literature review. They are also manifest in the description and commentary of the empirical results of our research. In addition to structural factors, such as the existence of natural and cultural resources, there are also specific elements capable of influencing the competitiveness of destinations, according to the stage of the destinations life cycle.

As can be seen, the first factor extracted encompasses all items that result from impacts on the territory as a result of tourism development and are likely to constitute a potential obstacle to the competitiveness of tourism destinations in the maturity stage. The second factor extracted, which we call natural resources and provided experiences, encompasses the natural landscape, the unique and memorable experiences, which can, of course, also include gastronomy – the third item integrated in this factor. Prices, quality of accommodations and security make up the third extracted factor, which makes clear that the existence of quality accommodations, one of the items commonly measured in studies of attractiveness of destinations, should also be linked to the issues of costs and safety (See Table 4).

The fourth factor is comprised of cultural resources and information available on the Internet. Again, here emerge factors usually considered in studies of attractiveness associated with factors that are critical for the attractiveness of tourism destinations (see Table 4).

The fifth factor extracted concerns feeling welcome at the destination, both in terms of the reception offered by the host community and ease of movement at the destination, including also the weather. This factor is complemented by the item regarding comments about the destination on the Internet. This item can in a virtual way anticipate the feeling of being welcome that respondents are likely to experience through the personal experiences of other tourists (see Table 4).

The sixth factor extracted includes items that can be considered complementary and perceived as not fundamental but that, under certain circumstances, may be decisive. The question of measures to protect natural resources only becomes important for tourists when there are visible problems in terms of resources. In addition, the availability of health facilities will only be decisive if the tourists, in the course of their holiday, need to use a hospital (See Table 4).

6. Conclusion

Increased global competition means some established tourism destinations face major challenges in maintaining their competitiveness, leading a high number of researchers to look for the best way to conceptualise and measure the competitiveness of tourism destinations. In this context, one of the goals of our paper is to prove that, according to the stage in the life cycle of a destination, there are specific factors able to influence the competitiveness of the destination. Since the focus of our work is tourism destinations in the maturity phase, we tried, at first, to establish the characteristics of these destinations in order to evaluate which characteristics would have, in the present and future, the ability to influence the competitiveness of these destinations.

We find that the specific factors identified should join the factors commonly used to measure the attractiveness of tourist destinations, including the existence of infrastructures; natural, cultural and social attractions; and, more recently, safety.

Measured through a quantitative methodology, the results allow us to conclude that, among the factors considered relevant for the competitiveness of tourism destinations in the maturity stage, the lack of environmental problems comes in fourth place, after factors already known as crucial, such as climate, safety and the friendliness and hospitality of the resident population. At the same time, we note that the fact that the destination is not overbuilt and has kept its authenticity is considered more relevant than having cultural resources. Any of these three items (does not present environmental problems, has not been overbuilt and has kept authenticity) comes ahead of factors normally considered crucial in the competitiveness of tourism destinations, such as price. The fact that a destination does not present environmental problems is considered more important than the existence of quality accommodations in that destination.

The use of a qualitative methodology changed the importance given to certain items. However, we note that, among the words or phrases listed spontaneously and more often, appears excessive construction, mentioned by around 63.5% of respondents. Only natural attractions (65.8%) and climate (64.8%) were mentioned by a higher number of respondents.

The factor analysis conducted regarding the importance of each factor allowed us to detect that the latent variable with the greatest explanatory power, i.e., responsible for explaining 22.5% of the variance, includes four items that we call impacts of tourism development in the region and that are exactly the specific factors identified as likely to adversely affect the competitiveness of tourism destinations in the maturity stage.

The use of a qualitative methodology allowed the detection of two items that were not included in quantitative methodology but that, for a considerable number of respondents, have a significant relevance. The scale did not include any item relating to the cleanliness of the destination. However, it was found that 40.5% of respondents said, spontaneously, that the presence of dirt and litter makes a tourist destination unattractive. The location of the destination was not integrated in the scale; however, noting the fact that 10.7% of respondents referred explicitly to the convenient location of the destination, i.e., being not too far from home and having good air connections makes the destination more attractive – we find it appropriate that, in future research processes, these two items be considered.

There are certain items that, regardless of the method chosen, are always considered very relevant, such as the climate or the existence of attractions. However, the same is not true with regard to security, because using quantitative methodology, this has been considered the second most important factor, but through our qualitative methodology, the words that refer to the importance of safety are only mentioned in eighteenth place, i.e., only 11.2% of respondents spontaneously referred to safety as a competitiveness factor. Similarly to scientific evidence found in other research areas and also in studies about the competitiveness of tourism destinations, it was found that the way the questions are formulated can very significantly influence the results. In this sense, we can conclude that a triangulation of methodologies offers the most guarantees to more completely access the factors that influence the competitiveness of tourism destinations.

References

Agarwal, S. (1997). The resort cycle and seaside tourism: An assessment of its applicability and validity. Tourism Management, 18(2), 65-73. [ Links ]

Agarwal, S. (2002). Restructuring seaside tourism. Annals of Tourism Research, (29)1, 25-55. [ Links ]

Aguiló, E., Alegre, J. & Sard, M. (2005). The persistence of the sun and sand tourism model. Tourism Management, 26(26), 219–231. [ Links ]

Bieger, T. (2002). Management von Destinationen (5ª ed.). Munique: Oldenbourg. [ Links ]

Briassoulis, H. (2004). Crete: Endowed by nature, privileged by geography, threatened by tourism? In B. Bramwell (ed.), Coastal mass tourism: diversification and sustainable development in Southern Europe (48-67). Clevedon: Channel View. [ Links ]

Buhalis, D. (1999). Tourism on the Greek Islands: Issues of peripherality, competitiveness and development. International Journal of Tourism Research, 1, 341-358. [ Links ]

Buhalis, D. (2000). Marketing the competitive destination of the future. Tourism Management, 21(1), 97-116. [ Links ]

Butler, R. (1980). The concept of a tourist area of life cycle of evolution: implications for management of resources. Canadian Geographer, 24(1), 5-12. [ Links ]

Cooper, C. & Jackson, S. (1989). Destination life cycle: The Isle of Man case study. Annals of Tourism Research, 16(3), 377-398. [ Links ]

Cooper, C. (1990). Resorts in decline: The management response. Tourism Management, 11(1), 63-67. [ Links ]

Cracolici, M. F. & Nijkamp, P. (2008). The attractiveness and competitiveness of tourist destinations: A study of Southern Italian regions. Tourism Management, 30, 336-344. [ Links ]

Dwyer, L. & Kim, C. (2003). Destination competitiveness: Determinants and indicators. Current Issues in Tourism, 6(5), 369-414. [ Links ]

Dwyer, L., Edwards, D., Mistilis, N., Roman, C. & Scotte, N. (2009). Destination and enterprise management for a tourism future. Tourism Management, 30(1), 63-74. [ Links ]

Dwyer, L., Forsyth, P. & Rao, P. (2000). The price competitiveness of travel and tourism: A comparison of 19 destinations. Tourism Management, 21(1), 9-22. [ Links ]

Enright, M. J. & Newton, J. (2005). Determinants of tourism destination competitiveness in Asia Pacific: Comprehensiveness and universality. Journal of Travel Research, 43(4), 339-350. [ Links ]

Faulkner, B. & Tideswell, C. (2005). Rejuvenating a maturing tourist destination: The case of the Gold Coast: Australia. In R. Butler (ed.), The Tourism Area Life Cycle, Vol. 1 (pp. 306-337). Channel View Publications.

Formica, S. & Uysal, M. (1996). The revitalization of Italy as a tourist destination. Tourism Management, 17(5), 323-331. [ Links ]

Formica, S. & Uysal, M. (2006). Destination attractiveness based on supply and demand evaluations: An analytical framework. Journal of Travel Research, 44(4), 418-430. [ Links ]

Foster, D. M. & Murphy, P. (1991). Resort cycle revisited - the retirement connection. Annals of Tourism Research, 18(4), 553-567. [ Links ]

Gearing, C. E., Swart, W. W. & Var, T. (1974). Establishing a measure of touristic attractiveness. Journal of Traval Research, 12(4), 1-8. [ Links ]

Getz, D. (1992). Tousim planning and destination life cycle. Annals of Tourism Research, 19(4), 752-770. [ Links ]

Go, F. & Govers, R. (2000). Integrated quality management for tourist destinations: A European perspective on achieving competitiveness. Tourism Management, 21(1), 79-88. [ Links ]

Gössling, S. (2002). Global environmental consequences of tourism. Global Environmental Change, 12(4), 283–302. [ Links ]

Hassan, S. (2000). Determinants of market competitiveness in an environmentally sustainable tourism industry. Journal of Travel Research, 38(3), 239-245. [ Links ]

Haywood, K. M. (1986). Can the tourist-area lifecycle be made operational? Tourism Management, 7(3), 154–167. [ Links ]

Haywood, K. M. (2005). Evolution of tourism areas and the tourism industry. In R. Butler, The Tourism Area Life Cycle (51-70). Clevedon: Channel View. [ Links ]

Hong, W. C. (2008). Competitiveness in the tourism sector. Heidelberg: Phisica-Verlag. [ Links ]

Hovinen, G. R. (1982). Visitor cycles: outlook for tourism in Lancaster County. Annals of Tourism Research, 9(3), 565–583. [ Links ]

Hu, W. & Wall, G. (2005). Environmental management, environmental image and the competitive tourist attraction. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 3(6), 617-635. [ Links ]

Hu, Y. & Ritchie, B. J. R. (1993), Measuring destination attractiveness: A contextual approach. Journal of Travel Research, 32(2), 25-34. [ Links ]

Hunter, C. & Green, H. (1995). Tourism and the environment: A sustainable relationship? Londres: Routledge. [ Links ]

Inskeep, E. (1991). Tourism planning - an integrated and sustainable development approach. New York: Van Nostrand Reinhold. [ Links ]

Ioannides, D. (1992). Tourism development agents - The Cypriot resort cycle. Annals of Tourism Research, 19(4), 711-73. [ Links ]

Ioannides, D. (2001). The dynamics and effects of tourism evolution in Cyprus. In Y. Apostolopoulos, P. Loukissas & L. Leontidou (eds.), Mediterranean tourism: facets of socioeconomic development and cultural change (pp. 112-145). Londres: Routledge. [ Links ]

Jamal, T. & Jamrozy, U. (2006). Collaborative networks and partnerships for integrated destination management. In D. Buhalis e C. Costa (eds.), Tourism management dynamics - trends, management and tools (pp. 164-172). Oxford: Elsevier Butterworth-Heinemann. [ Links ]

Kim, H. (1998). Perceived attractiveness of Korean destinations. Annals of Tourism Research, 25(2), 340-361. [ Links ]

Knowles, T. & Curtis S. (1999). The market viability of European mass tourist destinations: A post-stagnation life-cycle analysis. International Journal of Tourism Research, 1, 87-96. [ Links ]

Kozak, M. & Rimmington, M. (1998). Benchmarking: Destination attractiveness and small hospitality business performance. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 10(5), 184-188. [ Links ]

Malvárez García, G. & Pollard, G. (2003). The planning and practice of coastel zone management in Southern Spain. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 11(2&3), 204-223. [ Links ]

March, R. (2004). A Marketing-Oriented tool to assess destination competitiveness. Gold Coast, Queensland: Cooperative Research Centre for Sustainable Tourism.

Markwick, M. (2000). Golf tourism development, stakeholders, differing discourses and alternative agendas: The case of Malta. Tourism Management, 21(5), 515-524. [ Links ]

Maroco, J. (2003). Análise estatística - com utilização do SPSS (2nd ed). Lisboa: Sílabo. [ Links ]

Mazanec, J., Wöber, K. & Zins, A. (2007). Tourism destination competitiveness: from definition to explanation? Journal of Travel Research, 46(1), 86-95. [ Links ]

Mihalic, T. (2000). Environmental management of a tourist destination - A factor of tourism competitiveness. Tourism Management, 21(1), 65-78. [ Links ]

Mo, C., Howard, D. R. & Havitz, M E. (1993). Testing an international tourist role typology. Annals of Tourism Research, 20(2), 319-335. [ Links ]

Murphy, P., Pritchard, M. P. & Smith, B. (2000). The Destination product and its impact on traveller perceptions. Tourism Management, 21(1), 43-52. [ Links ]

OECD (1980). The impact of tourism on the environment: General reports. Paris: OECD. [ Links ]

Pechlaner, H. & Tschurtschenthaler, P. (2003). Tourism policy, tourism organisations and change management in Alpine regions and destinations: A European perspective. Current Issues in Tourism, 6(6), 508-539. [ Links ]

Pestana, M. H. & Gageiro, J. N. (2008). Análise de dados para ciências sociais - A complementaridade do SPSS (5th ed.) Lisboa: Edições Sílabo. [ Links ]

Pigram, J. J. (1980). Environmental implications of tourism development. Annals of Tourism Research, 7(4), 554-583. [ Links ]

Pike, S. & Ryan, C. (2004). Destination positioning analysis through a comparison of cognitive, affective, and conative perceptions. Journal of Travel Research, 42, 333-342. [ Links ]

Priestley, G. & Mundet, L. (1998). The post-stagnation phase of the resort cycle. Annals of Tourism Research, 25(1), 85-111. [ Links ]

Priestley, G. (1995). Problems of tourism development in Spain. In H. Coccossis & P. Nijkamp (eds.), Sustainable tourism development (pp. 187-198). Brookfield: Avebury. [ Links ]

Rebollo, J. F. V. & Baidal, J. A. I. (2003). Measuring sustainability in a mass tourist destination: pressures, perceptions and policy responses in Torrevieja, Spain. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 11(2&3), 181-203. [ Links ]

Ritchie, J. R. B. & Crouch, G. I. (2003). The competitive destination – A sustainable tourism perspective. Wallingford: CABI Publishing. [ Links ]

Rodríguez-Díaz, M. & Espino-Rodríguez, T. F. (2008). A model of strategic evaluation of a tourism destination based on internal and relational capabilities. Journal of Travel Research, 46(4), 368-380. [ Links ]

Seaton, A.V. & Alford, P. (2001). The effects of globalisation on tourism promotion. In S. Wahab & Cooper, C. (eds.), Tourism in the age of globalisation (pp. 97-122). Londres: Routledge. [ Links ]

Smith, R. A. (1992). Beach resort evolution - implications for planning. Annals of Tourism Research, 19(2), 304-322. [ Links ]

Sun, D. & Walsh, D. (1998). Review of studies on environmental impacts of recreation and tourism in Australia. Journal of Environmental Management, 53(4), 323-338. [ Links ]

Turismo de Portugal (2009). Atratividade dos destinos turísticos: estudo de avaliação. Lisboa: Turismo de Portugal. [ Links ]

Twining-Ward, L. & Baum, T. (1998). Dilemmas facing mature island destinations: Cases from the Baltic. Progress in Tourism and Hospitality Research, 4(2), 131-140. [ Links ]

Wilde, S. & Cox, C. (2008). Linking destination competitiveness and destination development: findings from a mature Australian tourism destination, Proceedings of the Travel and Tourism Research Association (TTRA) European Chapter Conference - Competition in tourism: business and destination perspectives. Helsinki, Finland, 467-478.

World Economic Forum (2008). The travel & tourism competitiveness report 2008. Genebra: World Economic Forum. [ Links ]

Article history:

Submitted: 06 June 2012

Accepted: 5 March 2013