Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Indicators

-

Cited by SciELO

Cited by SciELO -

Access statistics

Access statistics

Related links

-

Similars in

SciELO

Similars in

SciELO

Share

Revista de Gestão Costeira Integrada

On-line version ISSN 1646-8872

RGCI vol.16 no.1 Lisboa Mar. 2016

https://doi.org/10.5894/rgci616

ARTICLE / ARTIGO

An attempt to assess horizontal and vertical integration of the Italian coastal governance at national and regional scales *

Uma tentativa de avaliar a integração horizontal e vertical da governança costeira italiana em escalas nacionais e regionais

Simone Martino @, 1

@Corresponding author to whom correspondence should be addressed.

1University of Tuscia, Department of Ecology and Biology, Viterbo, Italy. e-mail: <sim.marty@libero.it>.

ABSTRACT

This paper assesses the level of achievement of horizontal and vertical coordination needed to facilitate the governance of the Italian coast at national and regional scales. A questionnaire survey envisions a sectoral management of the coast and the lack of a uniform national strategy, even though a more integrated picture is found at regional scale. However, horizontal and vertical coordination is quite inhomogeneous between Regions, and different are the mechanisms put in place to accomplish it. Overall, it emerges a greater difficulty in coordinating policies and sectors at horizontal scale (i.e. same level of government) rather than at vertical level (different scales of government). To overcome the limited horizontal cooperation, some Regions have developed institutions based on an inter-sectoral coordination, committee or an advisory body. Others opted for an internal proactive collaboration that may resolve conflicting interests between General Directorates, without the mediation of any third party (advisory board). From the questionnaire survey emerges that several Regions have promoted pilot site projects to address specific sectoral issues, but only Emilia-Romagna has developed an integrated plan for the coastline to achieve integration across sectors. In addition, Emilia-Romagna and Toscana Regions have been promoting a bottom-up participatory vision for the coastal governance through forums or other discursive platforms to facilitate local participation. These Regions are also extending coastal management into the maritime spatial planning, a strategy recognised by the European Commission as the best compelling way to facilitate sectoral and institutional coordination and fully implement ICZM in Europe.Keywords: horizontal and vertical integration; ICZM policy process assessment; national and regional coastal management; Italy.

RESUMO

Este trabalho avalia o nível de realização de coordenação horizontal e vertical necessária para facilitar a governança da costa italiana em escalas nacionais e regionais. Através de um inquérito concluiu-se que existe uma gestão sectorial da costa e a ausência de uma estratégia nacional uniforme, apesar da existência de um quadro mais integrado à escala regional. No entanto, a coordenação horizontal e vertical não é homogénea entre as regiões, tendo sido criados diferentes mecanismos para a realizar. No geral, existe maior dificuldade na coordenação das Políticas e dos sectores à escala horizontal (ou seja, mesmo nível de governança), do que ao nível vertical (diferentes escalas de governança). Para superar a limitada coordenação horizontal, algumas regiões têm desenvolvido instituições baseadas num comité de coordenação inter-sectorial ou de um órgão consultivo. Outras optaram por uma colaboração pró-ativa interna que pode resolver conflitos de interesses entre Direcções-Gerais, sem a mediação de terceiros (conselho consultivo). O questionário permitiu verificar que diversas regiões promoveram projectos-piloto locais para tratar de questões sectoriais específicas, mas apenas Emilia-Romagna desenvolveu um plano integrado para o litoral como forma de alcançar a integração entre os setores. Além disso, as regiões de Emilia-Romagna e da Toscania têm vindo a promover uma visão participativa de baixo para cima na governança costeira através de fóruns ou outras plataformas discursivas para facilitar a participação local. Estas regiões também estão estendendo a gestão costeira para o ordenamento do espaço marítimo, estratégia esta reconhecida pela Comissão Europeia como a forma mais convincente de facilitar a coordenação setorial e institucional e implementar integralmente a gestão integrada das zonas costeiras da Europa.

Palavras-chave: a integração horizontal e vertical; avaliação do processo da política de ICZM; gestão costeira nacional e regional; Itália.

1. Introduction

This paper provides an overview of how significantly coordination is achieved at national and regional administrative scales in Italy, in order to identify those constraints limiting an Integrated Coastal Zone Management (hereafter ICZM) approach.

Nowadays in Italy, there is no overall coordinating policy for coastal management at national level. A review of the legal framework showed that territorial coordination is fragmented by a high number of sectoral laws and plans (Ministero dell’Ambiente, 2001a; MELS, 2011), even though a similar context is identifiable in other European countries (Humphrey & Burbridge, 1999). In order to counteract this model of governance, the EU launched since the middle of 90’ several initiatives to reach a consensus on the necessary measures for ICZM in Europe, and to identify and implement concrete actions.

An important initiative was the EU ICZM demonstration programme of 35 pilot studies articulated around three key words: co-ordination, co-operation, and concertation (CEC, 1995; CEC, 1999).

In 2000, based on the experiences and outputs of the demonstration programme, the European Commission (EC) adopted a Communication to the Council and the European Parliament in which ICZM is considered the instrument “…to balance environmental, economic, social, cultural and recreational objectives, all within the limits set by natural dynamics” (CEC, 2000).

In 2002, the Recommendation 2002/413/EC on the implementation of ICZM in Europe was adopted by the Council and Parliament (CEC, 2002), suggesting, among others, the “support and involvement of relevant administrative bodies at national, regional and local levels amongst which appropriate links should be established or maintained with the aim of improving coordination of the various existing policies”. In other terms, this vision demands good communication among governing authorities (local, regional and national). However, thirteen years later, coordination of sectors remains a critical issue in ICZM: the on-line consultation process held in 2011 on the impact of a Directive on Maritime Spatial Planning (MSP) showed that cooperation between the different competent bodies at different scales in the maritime governance remains a challenge (EC, 2011a). The incorrect use of the maritime space, caused by the lack of cross-sector coordination in granting sea spaces is considered one of the inefficiencies that could be compulsory addressed by the promulgation of a Directive on ICZM (EC, 2013) that was drawn in 2014.

Considering the importance of coordination and cooperation between competent bodies at different levels, this paper wants to show the state of the art of the coordinating strategies adopted at national and regional scales in Italy. In the literature, there are not many papers issuing this topic while the recent literature on Italian ICZM is more oriented to the formulation of decision support systems rather than analysing institutional processes (Pirrone et al.et al., 2005; Zanuttigh et al.et al., 2005; Marotta et al.et al., 2011; Giordano et al.et al., 2013). Some studies focused on the integration of several tools to support public administrations in limiting land use conflicts such as GIS, Emergy Analysis and Cost Benefit Analysis, mainly applied to coastal erosion and beach nourishment (Koutrakis et al.et al., 2008; Koutrakis et al.et al., 2010; Koutrakis et al.et al., 2011; Martino & Amos, 2015; Marzetti et al.et al., 2016).

Looking at the institutional aspects, Portman et al.et al. (2012) assessed the performance in eight countries (Belgium, India, Israel, Italy, Portugal, Sweden, UK, and Vietnam), of five ICZM mechanisms (environmental impact assessment; planning hierarchy; setback lines; marine spatial planning, and regulatory commission) and their role in achieving integration. The authors found that environmental impact assessment enhances science–policy integration, planning hierarchy and regulatory commissions are effective mechanisms to integrate policies across government levels, and marine spatial planning is a multi-faceted mechanism with the potential to promote all types of integration. Gusmerotti et al.et al. (2013) pointed out the reciprocal benefits of integrating nature protection planning (marine protected areas) and ICZM policies, and suggested market-based approaches as self-financing mechanisms for marine and coastal zones. Finally, Rochette (2009) focusing on the Italian ICZM framework, proposed a regional scale approach to ICZM as a necessary step to correct the deficiency of the national legislation, even though this does not necessarily guarantee the implementation of a coherent coastal policy. To the knowledge of the author, there is not any research on the quantitative valuation of horizontal and vertical integration for the Italian case and on the evaluation of the maturity of the ICZM policy by using the EU indicators for a good coastal governance (WGID, 2003). Although integration has a wide scope, in this paper it is considered the way to analyze the relationships between different levels of government (vertical dimension) and between institutions operating at the same administrative level (horizontal dimension). The main objectives of this research are:

1. Identifying the institutional arrangements for the management of the coastal zone in Italy;

2. Getting information on the perceived most suitable arrangements to achieve integration;

3. Assessing the vertical and horizontal integration of the Italian coastal management at national and regional levels, by a tailored questionnaire survey;

4. Evaluating the status or maturity of the ICZM policy process by using the EU indicators for coastal governance.

This paper describes initially the idea of ICZM adopted in this research, and then presents the methodology employed to assess coordination. Results are shown for the national and regional dimensions, and finally commented under the recent EU ICZM strategy based on a compulsory integrated maritime spatial planning approach.

2. ICZM as concerted action

The development of the ICZM model has facilitated the implementation of various initiatives both in developing and developed countries based on sharing “collective or concerted approach” as a key element to achieve sustainable coastal management (Steins, 1999). Of primary importance is the identification of those institutional arrangements able to “facilitate cooperative behaviour by which sustainability may be achieved” (Taussik, 2001).

Amending governance is a required condition and co-management strategy may offer an appropriate solution to cooperative behaviour as suggested for the fishery sector by Dubbink & van Vliet (1996). However, a unique solution for an integrated perspective of the coast cannot be found, depending its implementation on the local conditions (social, economic, political, etc.) of each country. Assessing the governance process may provide insight on the need to improve coordination between and within different administrative levels. From a bibliographic review, it emerges that there are different methods for planning, implementing and assessing ICZM strategies. These are based mainly on the presence and the status of indicators describing the outputs of coastal governance. The methodology adopted by Knecht et al.et al. (1996) is based on surveying different experts and stakeholders asking them to rate indicators of the coastal management process indicators along with an ordinal scale. Scores for each issue are summed up and then averaged. A similar framework is presented by Olsen et al.et al. (1997), Olsen (2003) and Henoque (2003).

To facilitate effective ways of achieving conservation and sustainable use of marine and coastal biodiversity, the working group on indicator and data of the EC proposed two different sets of indicators to test the implementation of the eight ICZM principles proposed by the 2002 Recommendation (Table 1): the first set concerns the analysis of the progress of an integrated governance of the coast (WGID, 2003) (indicators used in this research are reported in the SI-I); the second one describes the level of sustainability of the coastal zone (WGID, 2003).

These principles can be used as a checklist for internal action to assess whether the governance of each country (at different scales) is leading to improved sustainability of the coastal resources. To assess the grade of implementation of these principles, pilot tests have been conducted in some countries (Ireland, Belgium and England), showing that the most challenging are those dealing with adaptive management, working with natural processes, participatory approaches stakeholders involvement of all stakeholders (Pickaver & Ferreira, 2008; Ballinger et al.et al., 2010).

However, no equivalent studies have been carried out for the Italian ICZM. Focusing our attention on principle 7 of the ICZM Recommendation (Table 1), concerning the relationships between administrative bodies at national, regional and local levels, the analysis of the partnership between and within different tiers of government can be assessed by the progress indicators 9, 18, 19, 25, 26 and 30 (shown in Table 2) proposed by Pickaver & Ferreira (2008). In this research, progress indicators of an integrated governance of the coast developed by the EU working group on indicators and data (WGID, 2003) are used. These partially overlap with the progress indicators suggested by Pickaver & Ferreira (2008). A recent application from Pickaver & Ferreira (2008) shows that principle 7 is not well attained in the EU member states ICZM policy, while some exceptions can be found where formal mechanisms are enforced by regular stakeholders meetings.

As a whole, the questionnaire survey revealed that there were some promising results to achieve a better stakeholders’ engagement at local scale, providing a useful contribution to the wider debate on the eight principles of the EU ICZM Recommendation and their evaluation (McKenna et al.et al., 2008).

3. Methodology

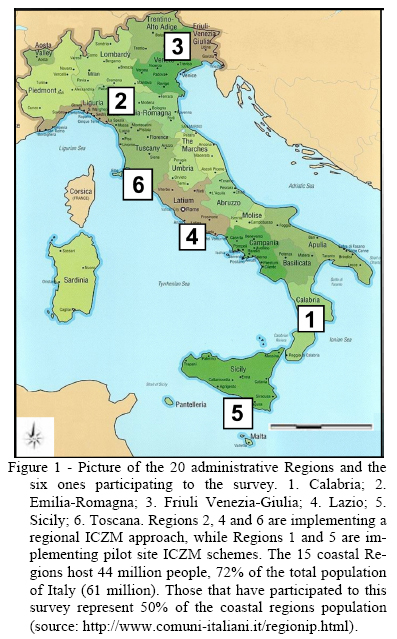

The ICZM “process” was evaluated by direct interview and questionnaire survey, and results were integrated with recent findings from the literature. An introductive letter, accompanying the questionnaire and explaining the aim of the research, was sent to the Environment and Territorial Planning Officers of the 15 coastal Regions. Regions that participated to the questionnaire survey are 6, a small selection of those that are implementing ICZM strategies (Figure 1). According to the non-statutory character of the EU ICZM Recommendation, no Region is obliged to adopt integrated measures for the coast. However, good practices developed by these six Regions are making others awareness of the importance of the ICZM approach.

The questionnaire was answered only by one person for each Region, the responsible of the ICZM programme or the closest officer involved in decision and policy-making for the coastal zone. These answers reflect the subjective vision of the person interviewed rather than the official position of the Regions. Although this could reduce the robustness of results, findings reflect the authoritative vision of the staff responsible for the implementation of the ICZM policy. The questionnaire is divided in four sections and composed of 21 questions (see Supporting Information II). The first section is an introduction exploring a general idea on the meaning of ICZM, the motivations for starting an ICZM programme, and the reasons, if they exist, for the limited implementation of the programme. The second part investigates current policies and programmes enforced to deal with coastal problems. Thirdly, mechanisms that operate for achieving horizontal and vertical integration are surveyed. Finally, the last section evaluates the status of ICZM implementation using the indicators posed by the EU working group on indicators and data (WGID, 2003).

In order to assess the preferences of ICZM institutional processes, several mechanisms, capable to provide coordination both at horizontal and vertical levels, have been proposed to officers that were asked to rank these mechanisms along an ordinal scale ranging from 1 to 4, where 1 is the highest value and 4 the lowest. In addition, the perceived level of integration achieved by each Region is assessed through the same ordinal scale to which respondents replied ticking only one level. Finally, the first version of the EU Working Group Indicators (WGID, 2003) is used to measure the evolution of the policy process towards the integrated “dimension” of the coastal governance. These indicators were originally proposed in 26 levels and grouped in 8 clusters (Pickaver et al.et al., 2004). Later they were revised in 31 levels and 4 clusters and adopted in 2005 to measure the progress of ICZM in some Member States (Pickaver & Ferreira, 2008). In this research, the first series of indicators was adopted, because of the unavailability of the final 2005 version when the questionnaire survey was carried out (see Supporting Information). The first cluster does not comprise any activities achieving ICZM and no coastal planning is implemented; the second one indicates coastal planning is occurring, but it may not be of integrated nature. The third one indicates that non-systematic ICZM schemes are occurring. The fourth cluster is indicative of the presence of a framework for ICZM, while clusters 6 and 7 are indicative of vertical and horizontal integration, respectively. Cluster 8 indicates efficient participatory planning and, finally, cluster 9 the full implementation of all the ICZM levels.

Data analysis

Analysis of data is performed through descriptive statistics (means and frequencies of the answers provided). Responses ranked along an ordinal scale were averaged to produce a synthetic figure of the level of horizontal and vertical coordination (Veal, 2011). In addition, cluster analysis is used to reduce the information acquired and show common patterns (similarities) between Regions.

4. Results

4.1 The national dimension of coastal management

During a telephonic survey carried out in 2005 with the Ministry of Environment Land and Sea (MELS) emerged a clear uncertainty on the need to formulate a national integrated strategy for the coast. The aim of the national government was the acquisition of adequate knowledge on the likely environmental and geological risks for the coast (i.e., coastal erosion, pollution, eutrophication, etc.) (Ministero dell'Ambiente, 2001b). It is not in place any definition of the coast, and a uniform legal framework for coastal management is still lacking. However, although there is no specific law for ICZM, there are several legal provisions that are relevant to coastal management. Article 822 of Civil Code states that seashores, beaches, roads, ports and rivers belong to the State as part of the Public Domain. The same code introduces a 300 metres zone behind the public maritime domain in which the consent of maritime authority must be obtained for the implementation of civil engineering works. Italy claims the 12nm (Law 14 nº .359) and the continental shelf limits are agreed with the neighbouring countries, while there are no 200nm rights in the Mediterranean basin (Vallega, 1999; Scovazzi, 1994). In strictly legal terms, the Italian coastal zone has an extension ranging from 300m landwards to 12nm seawards.

Several central agencies are involved in coastal management: Supporting Information II reports a view of the main competencies in coastal management by national institutions. The foremost responsibility for the protection of the coastal zone rests with MELS, instituted by the law 349/86 and reorganized by the Decree of the Republic President 178/2001. The latter gives MELS responsibilities on safety for navigation (to be operated by the Coast Guard), gazettment of marine protected areas, formulation of strategies against pollution, and conservation of marine biodiversity (art.7.3), among others. Other sectoral policies are provided by other Ministries (Supporting Information II), but conflicts between sectors and coastal policies are evident and slowly sorted out.

Supporting Information III presents a synthesis of the main laws affecting the governance of the coast both at national and regional scales, showing that for addressing the coastal governance, a redistribution of administrative powers between State and Regions has been operated. The Law Decree 112/98 has transferred to the Regions accountability for nature protection, pollution control, waste management, planning in the coastal zone and defence against erosion. Moreover, Regions are responsible for the management of small harbours, monitoring and formulation of plans for water quality improvement. At lower tier, Provinces are empowered to produce water survey and prepare provincial territorial management plans, while Municipalities to carry out operative actions for maintaining coastal defence structures, managing aqueducts, wastewater treatment plants and collecting environmental charges and taxes (Caravita, 2000).

Notwithstanding the prominent position of the regional administrations in managing the coast, national ICZM activities have been promoting since 2008 when a dedicated group to ICZM was established. For example, MELS has recently reviewed the 2006-2010 evolution of ICZM, the legal framework and plans of the 15 coastal Region administrations to coordinate the incoming effort of an integrated sub-national coastal and marine strategy. In addition, MELS has recently defined the roadmap (topics, timelines and actors), in agreement with the Regions and local authorities, to elaborate the “National Strategy for Integrated Coastal Zone Management”, and has established a permanent technical table on ICZM. Parallel to this, MELS is working on the “National Biodiversity Strategy” that can be considered a positive input and a strong commitment to ICZM-related activities. In addition, Italy, among others, has ratified the 1992 International Convention on Maritime Rights (UNCLOS), and the Barcelona Convention for the Protection of the Marine Environment and the Mediterranean Coastal Region with its protocols, including the 2008 ICZM Protocol. However, difficulties in coordinating ICZM efforts persist. Several factors delay an effective integrated strategy at national scale: from the non-binding requirement of the EU ICZM Recommendation, the devolution of more powers to the regional administrations, that made less important the need for a national ICZM strategy, and the reduction of funds for environmental protection (MELS, 2011).

4.2 Coastal management at regional scale

The questionnaire survey showed the presence of local ICZM experiences in Calabria, Sicilia and Friuli Venezia Giulia (in this Region a local management of the integrated marine reserve of Miramare is enforced by means of a voluntary environmental management scheme), while the other Regions (Toscana, Lazio, Emilia-Romagna) have been coordinating ICZM efforts at regional scale. In this region of Giulia a local management of the integrated marine reserve of Miramare is enforced by means of a voluntary environmental management scheme-EMAS

Lazio Region has legally appointed a non-executive ICZM Commission, a technical board that coordinates and supports the development of the littoral and provides further assistance in organising campaigns for public education. Moreover, an overarching executive committee takes legal decisions, prioritising the needs raised by the ICZM commission. From the survey emerges that the relationships between different organisations at the same institutional level are considered very good and integration successfully-achieved by using ad-hoc round tables, while vertical coordination is considered critical, even though specific accords with local authorities and with the Ministry of the Environment are in force. In the Toscana Region, coastal planning is not specifically coordinated by an ICZM committee, but by the territorial planning office. This institution seems to provide only a moderate integration with central (national) government, but good relationships with Provinces and Municipalities, which set up agreements with the Regional government for the preparation of an integrated plan. Emilia-Romagna Region is the first and unique Italian Region to have an integrated plan for the coast at regional scale since 2003. There is not any specific institution dedicated to ICZM, but sectoral directorates and other operative services interact with some degrees of cooperation. However, this cooperation is not always successfully achieved, especially along the horizontal dimension, and informal mechanisms are recognized as a useful way to improve coordination.

At vertical level, the Conference between Regions and State (this institution is adopted to coordinate the themes that are of common interests and involve State and Regions negotiation; DPCM 19 October 1983) is considered a good consolidated mechanism, while other more informal consultations for vertical integration are not taken into account. This institution was adopted to coordinate the themes that are of common interests and involve State and Regions negotiation; DPCM 19 October 1983. The other Regions have not an integrated plan, but only sectoral schemes for arranging coastal erosion problems (Sicilia), and hydro-geological disasters (Calabria). It is clear that coordinating mechanisms are not well consolidated as depicted by the responses provided by the interviewees.For the Sicilia Region a negative opinion has been expressed about the suitability of inter- and intra-government relationships. Of greater interest appears the vertical coordination with ISPRA (the national agency for the protection of and research on the environment) that promotes a good exchange of scientific information, even though contacts with local communities remain limited. In analogue way, a regional officer of Calabria Region expressed a negative view about relations at horizontal level. A dedicated committee for integrated coastal management is not in place, even though the “Environmental Regional Board” leads coastal-related operations. Conversely, vertical co-operation is guaranteed by periodical meetings with the central (national) level through the monitoring activities carried out by ISPRA, as it happens for Sicilia. The Friuli Venezia Giulia Region has not a plan for the integration of coastal sectoral activities, but a strong policy concerning the protection of nature by the creation of a network of natural reserves, the majority of them located in the coastal zone. In particular, the Region had a primary role in institutionalizing the marine reserve of Miramare, managed by WWF, and in funding it. A common mechanism used for coordinating the numerous directorates is given by consultations, with the possibility to operate in a scenario of urgency under the procedures of the Conference of Service. This institution is adopted to simplify procedures and time of access to resources and obtain shortly authorizations from the public organizations. Law n.241 1990

A synthesis of the mechanisms coordinating the governance of the coast for each of the Regions that participated to the questionnaire survey is reported in Supporting Information IV.

In order to assess the maturity of the horizontal mechanisms for coordination, the respondents were requested to provide their opinion using an ordinal scale ranging from 1 to 4, where 1 stays for great success; 2 for moderate success; 3 for moderate failure; and 4 for great failure. Half sample responded that a moderate success is achieved (3 responses: Calabria, Sicilia and Friuli Venezia Giulia). Lazio interviewee considers horizontal coordination achieved with a great success, while EmiliaRomagna respondent declared horizontal coordination achieved with great failure. Finally, Toscana officer considers horizontal integration achieved with moderate failure. The average value of the ranking scores is higher than 2, highlighting that a little proportion of failures exists.

A similar consideration can be formulated for the vertical integration: the average score of 1.8 suggests that this dimension is easier to be achieved than horizontal one. The proportion of answers is oriented towards a “moderate success”, as expressed by 80% of the sample (4 responses: Sicilia, Lazio, Friuli and Calabria interviewees). Only the Toscana Region, although has a reduced informal communication with the central level, considers vertical integration achieved with great success, in particular for the good relationships with Provinces and local Municipalities. The Emilia Romagna officer, that was very critic in valuing horizontal coordination, has not expressed any opinion, manifesting strong uncertainty.

4.3 Perception of the most effective horizontal and vertical mechanisms and level of implementation of ICZM at regional scale

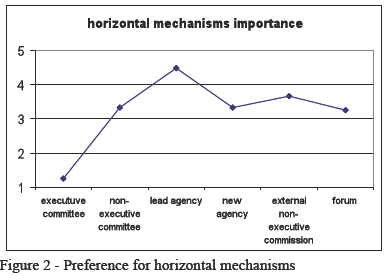

A few common horizontal mechanisms have been proposed to investigate the most effective way of addressing an integrated strategy. The mechanisms proposed are an inter-sectoral committee (executive and non-executive), a lead existing agency, a new lead agency, a consultative commission and regular forums. In Figure 2, it is reported the final score obtained averaging the ranking provided by the respondents. The lowest number represents the preferred choice.

It seems clear that an executive inter-sectoral committee is the best choice, as showed by Cicn Sain & Knecht (1998). A lead agency is not considered a good option probably because of the necessity of reducing the power of other agencies or directorates. Conversely, importance is given to a technical and advisory commission, as adopted by the Lazio Region, while Friuli Venezia Giulia and Emilia-Romagna Regions mainly advocate regular forums.

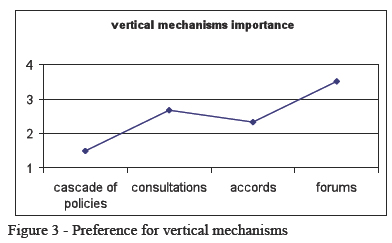

Vertical coordination seems to be more easily achieved by the well-consolidated State-Regions Conference. However, the other Regions use alternative mechanisms for obtaining formal and informal agreements with nanational agencies and local municipalities. Calabria and Sicilia Regions have facilitation in interacting with the Ministry of Environment by means of ISPRA, while Lazio Region has a direct dialogue with the same Ministry. Toscana Region, in particular way, shows good relationships with the Provincial administrations and local Municipalities, having agreed with them an integrated management strategy of the coast based on specific protocols. As regards the preferred choice, all Regions, apart from Emilia–Romagna and Friuli Venezia Giulia, consider the definition of a cascade of policies, from the strategic to operative level, fundamental to harmonise different tiers of government (Figure 3).

Emilia Romagna Region considers the cascade of policies the least important option among the mechanisms proposed and only the consequence of a previously adopted bottom-up strategy, involving consultations, accords and forums. This choice shows clearly that ICZM in Emilia Romagna has been achieving through a participative bottom-up process. Conversely, the analysis of the sample shows that, as for the horizontal integration, the least considered mechanism is forum and that coastal governance is far to be a participative process and still administered by a restricted number of policy makers, in line with a top-down approach. The best and worst options for each respondent on both horizontal and vertical coordinating mechanisms are proposed in Table 3.

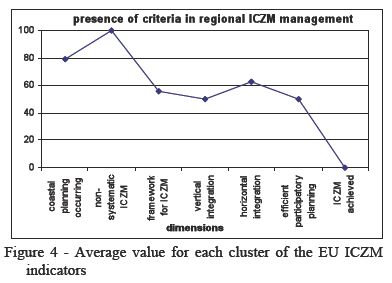

A way of measuring the status of integration is employed here by adopting the UE indicators. Twenty-six questions test the presence (YES/NO answer) of five ICZM-related dimensions: 1) presence of general planning and management for the coast; 2) presence of local pilot projects on ICZM; 3) framework for, but not yet, an ICZM implemented programme; 4) vertical and horizontal scope; 5) sound participatory planning achievements. The result of this survey is proposed in Figure 4, by aggregating the levels of each dimension (cluster).

From the Figure 4 emerges that while all the sampled Regions declare activities in coastal planning, positive answers on the presence of an ICZM framework drop to 50%, with integration perceived to be stronger at horizontal than vertical scale.

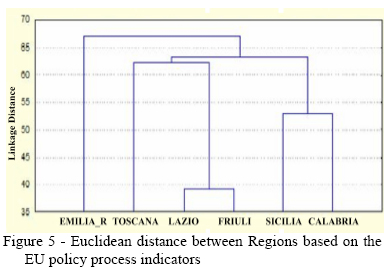

Finally, the cluster analysis is used to aggregate the Regions and to verify if there are some patterns of similarity, according to the responses given on the implementation of horizontal and vertical coordination mechanisms and the EU ICZM indicators. These similarities are assessed in terms of Euclidean distance between clusters (aggregations of Regions): the lower is Regions. From Figure 5 it is possible to individuate the presence of three clusters: one that contains only Emilia Romagna, the second encompassing Calabria and Sicilia, and the third Lazio, Friuli Venezia Giulia and Toscana. It is possible to note that there are no specific “regionalisms” (i.e., specific differentiations in the cluster aggregation due to different geographic positions): Regions with different geographical and socio-economic settings are in the same cluster and position in the cluster dendrogram, and it is likely that this result is given by the presence of a more mature activity in coastal management. Emilia Romagna is the unique Region that has in operation an integrated plan, and probably this has matured a new awareness of integrated coastal management. One of the most important features that differentiate Emilia Romagna from the other Regions is the consciousness of the importance of forums, public participation and informal exchange of information in tailoring an efficacious bottom-up ICZM programme.

5. Discussion

As suggested by the primary survey (2005) and re-affirmed in the literature (Rupprecht Consult & International Ocean Institute, 2006; EC, 2011b), Italy lacks a “uniform” national ICZM strategy, and is not developing policies equivalent to ICZM, but only the implementation of fragmented initiatives. This sectoral approach to coastal management has determined fragmented competencies between State and Regions and a general overlap of laws and regulations, facilitated by the Law Decree 112/98, which has institutionalised the devolution of administrative procedures for coastal planning and management to the regional governments. In addition, this has limited the importance of the national role, as confirmed by the responses given by the Toscana Region officer. Finally, the last review on the ICZM state of art, conducted by the Ministry of Environment Land and Sea, has evidenced not only the lack of a specific national policy on ICZM, but also the lack of ad-hoc planning and programming tools and the unavailability of adequate financial support (MELS, 2011).

Notwithstanding the aforementioned concerns, new cross-cutting institutions have recently been put in place to intensify dialogue with the peripheral administrations, such as specific policies and round tables, addressing and coordinating biodiversity issues. These are the national working group on the Integrated Maritime Policy; the Joint Committee for the National Strategy for Biodiversity (composed of representatives of the central Administrations, Regions and Autonomous Provinces); and the national Observatory for Biodiversity (coordinated by the Ministry for the Environment, and composed of representatives of the Regional Observatories on Biodiversity, Protected Areas, and the national main scientific institutions) (MELS, 2011). In addition, from the stock tacking provided by the Ministry of Environment Land and Sea, it emerges that a great effort was channelled to improve coordination between fisheries stakeholders through specific commissions (“tables”) within the Ministry of Agriculture Forestry and Fishery. In particular, the “Light-blue Table” was set up to guarantee coordination in fisheries management with the support of the Regions, while the central “Committee for fisheries and aquaculture” to guarantee exchange of information between administrators, researchers and entrepreneurs.

Notwithstanding the absence of any official positions from MELS on the ideal ICZM institution, we could expect, based on other European and international experiences (Sorensen, 1993; Cicin-Sain & Knecht, 1998), that an (executive) inter-agency commission might be appropriate to coordinate a national ICZM strategy, in conjunction with an act reducing conflicts and amending legal instruments governing sectoral interests.

Analogue perspective is found in the Mediterranean Action Plan (Pavasovic, 1996), where a networked approach (Born & Miller, 1988; Knecht et al.et al., 1996) is advocated. The latter is the most adopted approach in developed countries, where sectoral interests are unlikely harmonised by a lead-planning agency (Boelaert-Suominen & Cullinam, 1994; Cinin-Sain & Knecht, 1998). However, the UK approach based on building consensus from the bottom by integrating sectoral divisions inside forums and arenas (Kennedy, 1995; Inder, 1996; Jones, 1996; Scott, 1996; Taussik, 1997; Ballinger, 1999) seems to be exportable into the Italian context, especially after the devolution of many administrative functions to the regional governments. Recently, voluntary bottom-up strategies have been emerging at regional and local scales, facilitated by consolidated negotiated planning tools and pilot projects experimenting local ICZM strategies.

The results of the questionnaire survey, supported by the most recent institutional review (MELS, 2011), showed clearly the materialization of an integrated spatial plan for the implementation of ICZM in Emilia Romagna, while in other Regions coastal planning was addressed to specific issues (coastal erosion, landscape protection, etc.). Examples are given by the Lazio Region where specific programmes were oriented to the defence of the coast from erosion (Koutrakis et al.et al., 2008; 2010, Martino & Amos, 2015), and by the Toscana Region, that has developed a specific Plan for the National Park of the Tuscany Archipelago and for the Regional Park of Maremma. However, the possibility to improve coordination in Regions with only sectoral coastal planning in place seems to be related to the creation of new cross-fertilising institutions as already verified by Cicin-Sain & Knecht (1998).

Looking at the ICZM institutions in some European Countries, we can find three different main typologies: a national body serving mainly as an advisory board, such as the Direcion General de Costas in Spain; the UK national planning and marine policy guidelines addressing voluntary bottom-up coastal management strategies; and the planning approach adopted by Sweden (Taussik, 1997) to integrate terrestrial and maritime domain. While the Spanish choice is based on a central national top-down framework, the UK approach promotes voluntary local coastal partnerships, coordinated by the National Coastal Forum that brings together representatives of central and local governments, industry and commerce, recreation and conservation sectors (Humphrey & Burbridge, 1999). Amongst the EU Member States, the UK shows that informal links between different coastal stakeholders can provide interesting results in the achievement of major cooperation whereas other countries (Italy, Bulgaria, Cyprus, Ireland, Estonia, and Greece) have not shown any progress in the implementation of the principle 7 (see Table 1) of the EU ICZM Recommendation (Pickaver & Ferreira, 2008). Overall, a qualitative measure of ICZM implementation is about 50%. In other words, Europe is about halfway in implementing the ICZM principles (ECb, 2011).

The implementation of the subsidiarity principle in Italy makes high expectation for ICZM to be implemented by regional governments and local administrations. This caused different Regions to react in different ways to the formulation of an integrated strategy: from the new planning system of Emilia Romagna, to the centralised board of Lazio Region, and the enforcement of agree agreements between the Regional Government, Provinces and Municipalities adopted by the Toscana Region. In addition, some forms of voluntary participation in local isolated project have been experienced at municipal level, showing that local forums are a good way to hear the dissent from public. Addressing this point, however, is not an easy task because coastal management was perceived in Italy as a public issue only in the early 1990s. Italy has a limited tradition in public discussion and stakeholders engagements during disputes and conflicts, as it generally occurs in the UK or USA. “Conflicts are numerous, but they are considered largely within the sanctuary of policy-makers and bureaucracy and are not topics of broad-ranging public debate” (Vallega, 2001). One of the rare moments of open debates was the gazettment of the important marine protected area of Portofino (Salmona & Verardi, 2001) that triggered an intense conflict between local authorities and users.

The third ICZM strategy is the integrated sea-land planning, adopted in Sweden. In 2013, the EU Commission opted for this approach to homogenise ICZM efforts in all members states, presenting a Directive (Directive 2014/89/EU) that establishes a framework for maritime spatial planning (MSP) as a tool to integrate sectoral activities at sea and land, to ensure the involvement of stakeholders, and to consider economic, social and environmental aspects in supporting sustainable development and growth (EC, 2007). A recent study revealed that a binding framework to implement MSP/ICZM would be the most effective way of achieving the operational objectives by the reduction of transaction costs for maritime businesses and coordination costs for public authorities (EC, 2013). The binding act will require Member States to establish coastal management strategies that build on the principles of the 2002 Recommendation and the Protocols of the Barcelona Convention on Integrated Coastal zone Management. This choice, for the first time in the European Union, will bring a set of obligations, including development of best practices, but a reduced emphasis for voluntary approaches, such as guidelines and recommendations that are not considered to produce the desired results in improving the sea-land interface planning. At the time of this script, no change in the governance of the Italian coastal zone, according to the Directive 2014/89/EU, is visible, whose maritime planning authority must be chosen by September 2016, and ICZM plans organised by 2021.

This paper is a first effort to evaluate approaches employed for coordinating levels of government for coastal management in Italy, and to assess the maturity of the ICZM policies at national and sub-national scales. As described in the literature and confirmed by the national survey, Italy lacks a uniform national ICZM strategy. An attempt of integrating initiatives for coastal management is evident at sub-national scale mainly in Emilia-Romagna, Toscana, Liguria, and Lazio Regions, even though with different approaches and grades of maturity. Although since 2014 a binding act (Directive 2014/89/EU) requires Member States to establish coastal management strategies within a revised maritime spatial planning, no change to this direction in the governance of the Italian coastal zone is visible. However, results from the questionnaire survey show that some of the indicators suggested by the working group on ICZM indicators are achieved at regional scale, such as the presence of a framework for the evaluation of coastal activities; the promulgation of laws for planning protected areas; the promotion of isolated ICZM pilot projects; the integration of natural and social information; and the adoption of a monitoring programme.

The unfulfilled indicators refer to the absence of a national master plan for the coast, the lack of integrated legislation for coastal planning and management, and the limited communication between institutions at the same tiers of government. The latter point suggests that principle 7 of the EU Recommendation on ICZM is not yet fulfilled. Among the indicators reported in Table 2, only those numbered 9, 18 and 19, covering the presence of formal mechanisms, open channels of communication, and dedicated staff to ICZM implementation, respectively, are satisfied. However, it is not possible to say that an effective political support, routine cooperation across coastal and marine boundaries, and mechanisms for reviewing progress in implementing ICZM are achieved.

From the results of the direct survey, integrated by the recent national stocktaking and the literature review, it is possible to state that an inter-sectoral committee is emerging as the best solution for the horizontal coordination, while a cascade of policies from central to local governments and accords are considered a good way to reinforce dialogue between administrations at different scales. Conversely, forums both at national and regional levels were not well appreciated, probably for the lack of consensus-building approach in policy-making and the adoption of a top-down territorial planning strategy.

The low level of integration between ICZM policies is a common issue in many European countries, probably caused by the non-statutory requirements of the 2002 EU Recommendation. Considering the limited results achieved, integrating sectoral policies for the coast within maritime planning has been the choice of the EU. Beyond the recent decision of the EU to implement a directive on ICZM under a marine spatial planning strategy, and considering the pressures for organizational changes, the sectoral division may be unified through informal discursive platforms, especially at local scale where limited ICZM programme capacity exists, as promoted by the Toscana Region. The latter strategy would provide flexible decentralised arrangements to local organisations and involve public interests in order to raise awareness of the importance of the coastal zone. This strategy seems a good solution to win the policy dictates of a top-down approach, typical of the Italian planning system, before achieving the new binding requisites of the maritime spatial planning Directive 2014/89/EU.

References

Ballinger, C.R. (1999) - The evolving organisational framework for integrated coastal management in England and Wales. Marine Policy, 23(4-5):501-523. DOI: 10.1016/S0308-597X(98)00054-2 [ Links ]

Ballinger, R.; Pickaver, A.; Lymbery, G.: Ferreria, M. (2010) - An evaluation of the implementation of the European ICZM principles. Ocean & Coastal Management, 53(12):738-749. DOI: 10.1016/j.ocecoaman.2010.10.013 [ Links ]

Boelaert–Suominen, S.; Cullinan, C. (1994) - Legal and institutional aspect of integrated coastal area management in national legislation, 124p., FAO.

Born S.M.; Miller A.H. (1988) - Assessing networked coastal zone management programs, Coastal Management, 16: 229-243. doi: 10.1080/08920758809362060 [ Links ]

Caravita, B. (2000) - Diritto pubblico dell’ambiente, seconda edizione, Il Mulino, Bologna.

CEC (1995) - Communication from the Commision to the Council and the European Parliament on the integrated management of the coastal zone, COM 511/95, Bruxelles, Luxembourg. ISBN 92-828-6463-4. [ Links ]

CEC (1999) - Lessons from the European Commission’s demonstration programme on integrated coastal zone management (ICZM), Bruxelles, Luxembourg.

CEC (2000) - Communication from the Commission to the Council and the European Parliament on integrated coastal zone management: a strategy for Europe. COM (2000) 547 final. Brussels: CEC. [ Links ]

CEC (2002) - Recommendation of the European parliament and of the council of 30 May 2002 concerning the implementation of integrated coastal zone management in Europe. 2202 413/EC [ Links ]

Cicin-Sain, B.; Knecht, R. (1998) - Integrated coastal and ocean management, 543p., Island Press, Washington, U.S.A. ISBN: 9781559636049. [ Links ]

Dubbink, W., van Vliet M. (1996) - Market regulation versus co-management? Marine Policy, 60(6):499-516. 10.1016/S0308-597X(96)00035-8 [ Links ]

EC (2007) - An Integrated Maritime Policy for the European Union. COM(2007) 574 final [ Links ]

EC (2011a) - Public hearing on integrated coastal zone management, 30 May 2011 hearing report. [ Links ]

EC (2011b) - Support study for an impact assessment for a follow-up to the EU ICZM recommendation (2002/413/EC). [ Links ]

EC (2013) - Proposal for a Directive of the European Parliament and of the Council establishing a framework for maritime spatial planning and integrated coastal management, COM(2013)133. [ Links ]

Giordano, L.; Alberico, I.; Ferraro, L.; Marsella, E.; Lirer, F.; Di Fiore, V. (2013) - A new tool to promote sustainability of coastal zones. The case of Sele plain, southern Italy. Rendiconti Lincei, 24(2):113-126. DOI: 10.1007/s12210-013-0236-2 [ Links ]

Gusmerotti, N.M.; Marino, D.; Testa, F. (2013) - Environmental policy tools to improve the management of marine and coastal zones in Italy: the self-financing instruments. In:

E. Creighton & P. Danovich, Environmental Policy: Management, Legal Issues and Health Aspects, Nova Science Publishers, New York, U.S.A. ISBN: 978-1628084979. [ Links ]

Hunphrey, S.; Burbridge, P. (1999) - Planning and management process: sectoral and territorial cooperation. Available at http://europa.eu.int/comm/environment/iczm/themd_rp.pdf. [ Links ]

Inder, A. (1996) - Partnership in planning and management of the Solent. In: J. Taussik & Mitchell J., (org.), Partnership in the coastal zone Management. Cardigan Samara Publishing limited. [ Links ]

Jones, S. (1996) - A comparative analysis of coastal zone management plans in England and The Netherlands. In: Jones, Healy & Williams (org.), Studies in European coastal management, pp. 143-154, Samara Publishing Limited, Cardigan, U.K. ISBN: 978-1873692073 [ Links ]

Kennedy, K.H. (1995) - Producing management plans for majors estuaries - the need for a systematic approach: a case study of the Thames estuary. In: Healy and Doody (org.), Directions in European coastal Management, pp. 451-459, Samara publishing Limited, Cardigan, U.K. ISBN: 978-1873692066. [ Links ]

Knecht, R.; Cicin-Sain, B.; Fisk, W.G. (1996) - Perception of the performance of state coastal zone management programs in the United States. Coastal Management, 24:141-163. DOI: 10.1080/08920759709362325 [ Links ]

Koutrakis, E.T.; Sapounidis, A.; Marzetti, S.; Giuliani, G.; Cerfolli, F.; Nascetti, G.; Martino, S.; Fabiano, M.; Marin, V.; Paoli, C.; Vassallo, P.; Roccatagliata, E.; Salmona, P.; Rey-Valette, H.; Roussel, S.; Carnus, F.; Bellet, F.; Povh, D., Malvarez, C.G. (2008) - Le Sous-projet ICZM-MED - Actions concertées, outils et critères pour la mise en oeuvre de la Gestion Intégrée des Zones Côtières (GIZC) Méditerranéennes. In: BEACHMED-e (org.) - La gestion stratégique de la défense des littoraux pour un développement soutenable des zones côtières de la Méditerranée, 159p., GIER Graphic srl, Rome, Italy [ Links ]

Koutrakis, E.T. ; Sapounidis, A. ; Marzetti, S.; Giuliani, V.; Martino, S.; Fabiano, M.; Marin, V.; Paoli, C.; Roccatagliata, E.; Salmona, P.; Rey-Valette, H.; Roussel, S.; Povh, D.; Malvárez, C.G. (2010) - Public Stakeholders' Perception of ICZM and Coastal Erosion in the Mediterranean. Coastal Management, 38(4):354-377. DOI: 10.1080/08920753.2010.487148 [ Links ]

Koutrakis, E.T.; Sapounidis, A.; Marzetti, S.; Marin, V.; Roussel, S.; Martino, S.; Fabiano, M.; Paoli, C.; Rey-Valette, H.; Povh, D.; Malvárez, C.G. (2011) - ICZM and coastal defence, perception by beach users: lessons from the Mediterranean coastal area. Ocean & Coastal Management, 54:821-830. DOI: 10.1016/j.ocecoaman.2011.09.004 [ Links ]

Marotta, L.; Ceccaroni, L.; Matteucci, G.; Rossini, P.; Guerzoni, S. (2011) - A decision-support system in ICZM for protecting the ecosystems: integration with the habitat directive. Journal of Coastal Conservation, 15(3):393-405. DOI: 10.1007/s11852-010-0106-3 [ Links ]

Martino, S.; Amos, C.L. (2015) - Valuation of the ecosystem services of beach nourishment in decision making: The case study of Tarquinia Lido, Italy. Ocean & Coastal Management, 111:82-91. DOI: 10.1016/j.ocecoaman.2015.03.012 [ Links ]

Marzetti S.; Disegna M.; Koutrakis E.; Saponidis A.; Marin, V.; Martino, S.; Roussel, S.; Rey-Valette, H.; Paoli, C. (2016) - Awareness of ICZM and WTP in European Mediterranean regions: a case study. Marine Policy, 63:100-108. DOI: 10.5367/te.2013.0360 [ Links ]

McKenna, A.J.; Cooper, A; O’Haganm A.M. (2008) - Managing by principle: A critical analysis of the European principles of Integrated Coastal Zone Management (ICZM). Marine Policy, 32(6):941–955. DOI: 10.1016/j.marpol.2008.02.005

Ministero dell’Ambiente (2001a) Relazione sullo stato dell’ambiente 2001, Ministero dell’Ambiente, Rome, Italy.

Ministero dell’Ambiente (2001b) - Strategia d’azione ambientale per lo sviluppo sostenibile in Italia, Ministero dell’Ambiente, Rome, Italy.

MELS (2011) - Italian National Report on the implementation of ICZM based on the EU ICZM Recommendation (2006-2010). Available on-line at http://www.minambiente.it/home_it/menu.html?mp=/menu/menu_attivita/&m=argomenti.html%7CMare.h tml%7CGestione_Integrata_delle_Zone_Costiere__.html. [ Links ]

Olsen, B.S.; Tobey, J.; Kerr, M. (1997) - A common framework for learning from ICM experience, Ocean & Coastal Management, 37:155-174. DOI: 10.1016/S0964-5691(97)90105-8 [ Links ]

Olsen, S.B. (2003) - Frameworks and indicators for assessing progress in integrated coastal zone management initiatives, Ocean & Coastal Management, 46, 347-361. DOI: 10.1016/S0964-5691(03)00012-7 [ Links ]

Pavasovic, A. (1996) - The Mediterranean Action Plan Phase II and the revised Barcelona Convention: new prospective for integrated coastal management in the Mediterranean region, Ocean & Coastal Management, 31:133-182. DOI: 10.1016/S0964-5691(96)00036-1 [ Links ]

Pickaver, A.; Ferreira, M. (2008) - Implementing ICZM at sub national/local level-recommendation on best practices. EUCC The Coastal Union. [ Links ]

Pickaver, A.H.; Gilbert, C.; Breton, F. (2004) - An indicator set to measure the progress in the implementation of integrated coastal zone management in Europe. Ocean & Coastal Management, 47: 449-462. DOI: 10.1016/j.ocecoaman.2004.06.001 [ Links ]

Pirrone, N.; Trombino, G.; Cinnirella, S.; Algieri, A.; Bendoricchio, G.; Palmeri, L. (2005) - The Driver-Pressure-State-Impact-Response (DPSIR) approach for integrated catchment-coastal zone management: preliminary application to the Po catchment-Adriatic Sea coastal zone system. Regional Environmental Change, 5:111–137. DOI: 10.1007/s10113-004-0092-9

Portman, M.E.; Esteves, L.S.; Le, X.Q.; Khan, A.Z. (2012) - Improving integration for integrated coastal zone management: An eight country study. Science of The Total Environment, 439:194–201. DOI: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2012.09.016.

Rochette, J. (2009) - Challenge, dialogue, action… Recent developments in the protection of coastal zones in Italy. Journal of Coastal Conservation, 13(2-3):131-139. DOI: 10.1007/s11852-009-0051-1

Rupprecht Consult & International Ocean Institute (2006) - Evaluation of Integrated Coastal Zone Management in Europe -Final Report, Cologne, Germany. [ Links ]

Salmona, P. ;Verardi, D. (2001) - The marine protected area of Portofino, Italy: a difficult balance. Ocean & Coastal Management, 44: 39-60. DOI: 10.1016/S0964-5691(00)00084-3 [ Links ]

Scott A. (1996) - The role of the coastal forum in coastal zone management: case study of Cardigan Bay forum. In: J. Taussik and Mitchell J., (org.), Partnership in the coastal zone Management, pp.557-564, Samara Publishing, Cardigan, U.K. [ Links ]

Scovazzi, T. (1994) - International law of the sea as applied to the Mediterranean. Ocean and Coastal Management, 24(1):71-84. DOI: 10.1016/0964-5691(94)90053-1 [ Links ]

Sorensen, J. (1993) - The international proliferation of integrated coastal zone management efforts. Ocean & Coastal Management, 21:45-80. DOI: 10.1016/0964-5691(93)90020-Y [ Links ]

N.A. (1999) - All hands on deck. An interactive perspective on complex common-pool resource management based on case studies in the coastal waters of the Isle of Wight (UK), Connemara (Ireland) and the Dutch Wadden Sea. Wageningen, Ponsen and Looijen. ISBN: 90-5808-097-8 [ Links ]

Taussik, J. (1997) - The influence of the institutional system on planning the coastal zone: experiences from England and Sweden, Planning Practice & Research, 12(1):9-19. DOI: 10.1080/02697459716671 [ Links ]

Taussik, J. (2001) - Collaborative planning in the coastal zone. PhD thesis, University of Cardiff, U.K. [ Links ]

Vallega, A. (1999) - Fundamentals of integrated coastal management. 267p., Kluwer Academic. ISBN: 9780792358756. DOI: 10.1007/978-94-017-1640-6 [ Links ]

Vallega, A. (2001) - Focus on integrated coastal management- comparing perspectives. Ocean & Coastal Management, 44: 119-134. DOI: 10.1016/S0964-5691(00)00083-1 [ Links ]

Veal, A.J. (2011) - Research methods for leisure and tourism, a practical guide. 2nd ed., Pitman Publishing, London, U.K. ISBN: 978-0273717508 [ Links ]

WGID -Working Group on Indicators and Data (2003) - Measuring sustainable development on the coast. A report to the EU ICZM Expert Group by the working group on indicators and data under the lead of ETC TE. Available on-line at http://ec.europa.eu/environment/iczm/pdf/report_dev_coast.pdf [ Links ]

Zanuttigh, B.; Martinelli, L.; Lamberti, A.; Moschella, P.; Hawkins, S.; Marzetti, S.; Ceccherelli, V.U. (2005). Environmental design of coastal defence in Lido di Dante, Italy. Coastal Engineering, 52(10):1089-1125. DOI: 10.1016/j.coastaleng.2005.09.015 [ Links ]

Legislation

Civil Code approval, Royal Decree 16 March 1942, n. 262, GU, nº. 79, Suppl. Straord. 4th April 1942.

Law nº.359/74, 14 August 1974, GU 218 21st August 1974.

Law nº. 349/86, 8 July 1986, Institution of the Ministry of the Environment and legislation for environmental damage, GU 162 Suppl. Ord.59, 15th July 1986.

Decree of the Republic President, nº. 178/2001, 27 March 2001, Organisation of the Minster of Environment, GU 114, 18th May 2001.

Law Decree nº. 112/98, 31st March 1998, handing over administrative roles of the State to Regions and local administrations to enforce the law 15th March 1997, n. 59, GU 92, Suppl. Ord n. 77, 21st April 998.

Barcelona Convention - Convention for the Protection of the Marine Environment and the Coastal Region of the Mediterranean. 16th February 1976. http://www.unep.org/NairobiConvention/docs/Barcelona_Convention_full_version.pdf

Protocol on Integrated Coastal Zone Management in the Mediterranean. 21st January 2008. http://www.unep.org/NairobiConvention/docs/ICZM_Protocol_Mediterranean_eng.pdf

* Submission: 1 AUG 2015; Peer review: 3 OCT 2015; Revised: 28 JAN 2016; Accepted: 30 JAN 2016; Available on-line: 1 FEB 2016

Appendix

This article contains supporting information online at http://www.aprh.pt/rgci/pdf/rgci-616_Martino_Supporting-Information.pdf