Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Acessos

Acessos

Links relacionados

-

Similares em

SciELO

Similares em

SciELO

Compartilhar

Medievalista

versão On-line ISSN 1646-740X

Medievalista no.28 Lisboa jul. 2020

https://doi.org/10.4000/medievalista.3348

ARTICLE

The Evolution of Different Fonts in the Coptic Churches Throughout the Centuries

A evolução das diferentes fontes de água nas igrejas coptas ao longo dos séculos

Mary Magdy Anwar1

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-8974-0598

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-8974-0598

1Faculty of Tourism and Hotels Alexandria University, Tourist Guidance Department. 21500 Alexandria, Egypt. marymagdy1982@gmail.com

ABSTRACT

Although Christianity was widespread in Egypt since the 1st century, Christians were only allowed to exercise their worship freely after the Milan decree. From this date, Christianity was recognized and the churches were built.

The architecture adopted in the foundation of the churches involved the construction of some basins for different uses such as the baptismal basin which changed shape and location over the centuries. The churches also contained "El Maghtas" used for holy water during the feast of the Epiphany. The basin called "El Laqân" of circular shape not deep was carved on the floor of the old churches. Besides these, other pools were used for washing and for exercising Extreme Unction.

Thus, we will explain in this research the difference between the basins, their evolution and their importance while referring to examples from various ancient Coptic churches.

Keywords: Architecture; Basin; Heritage; Maghtas; Laqân.

RÉSUMÉ

Bien que le Christianisme fût répandu en Egypte dès le premier siècle, les Chrétiens n'eurent le droit d'exercer librement leur culte qu'après le décret de Milan. A partir de cette date, le Christianisme fut reconnu et les églises furent édifiées.

L'architecture adoptée dans la fondation des églises impliquait la construction de quelques bassins pour différents usages comme le bassin baptismal qui changea de forme et d'emplacement au cours des siècles. Les églises contenaient également "El Maghtas" utilisé pour l'eau bénite durant la fête de l'Epiphanie. Le bassin appelé "El Laqân" de forme circulaire pas profond était sculpté sur le sol des anciennes églises. A part ceux-ci, on utilisait d'autres bassins pour se laver et pour exercer l'Extrême-Onction.

Ainsi, nous expliquerons dans la recherche la différence entre les bassins, leur évolution et leur importance tout en se référant sur des exemples figurant dans différentes anciennes églises coptes.

Mots clés: Architecture; Bassin; Patrimoine; Maghtas; Laqân.

Only after the promulgation of the Milan decree of Emperor Constantine I in 313 A. D. that Christians in Egypt had the right, after long years of persecution, to build churches by adopting the architectural styles of rectangular basilica and Byzantine known as domes. The church consisted of a nave, choirs, aisles and shrines. Baptisteries, fonts of the laqqān, as well as a basin named Al Maghtas were also built in the architecture of the Coptic Orthodox churches during the centuries that followed.

Our research aims to first of all emphasize the differences between these basins, their use and their evolution. Second to highlight their importance by exposing various examples appearing in the different ancient monasteries and churches, especially that these buildings represent a significant part of the Coptic Egyptian heritage that should not be overlooked.

The rite of Baptism and the Baptisteries

The baptism, in arabic El-Maʽmūdia (المعمودية) is derived from Greek baptisma (βάπτισμα) which means “dyeing”[1]. It is surnamed “gate of the mysteries” and represents the first sacrament of the Coptic Church where pure water is used[2].

The priest performs trine immersion[3], which symbolizes the three days since the death until the Resurrection of Christ. Those three days evoke also the crossing of the Red Sea by Moses and the Israelis and related to the Trinity[4]. In the first centuries, the immersion was total (that was why the baptisteries were deep in the old churches). Then the custom changed, only the last immersion remained total, the first two became partial; one to the half of the body and the other to the neck[5].

The priest pours oil of gladness (ghâlîlâû, الغاليلاون) and Chrism (Myron) on the baptismal waters, then he takes the Myron and applies 36 unctions to the different parts of the neophyte's body for confirmation[6].

Although, this rite recalls the one that was established by Saint John the Baptist on the banks of the Jordan and to which he invited the sinners as a sign of repentance, Jesus himself was baptized there (Matthew 3:6). The date of the beginning of baptism by the Apostles is not known. The ritual took place in the rivers, as happened to the first three thousand converts by Peter and the Apostles (Acts 2:41), and in the case of Philip and the Ethiopian's eunuch (Acts 8:36)[7].

We note that the timing of baptism was changeable. From the 2nd to the 4th century, baptism only took place during the feasts of the Resurrection or Pentecost. Then from the 4th to the 7th century, the Epiphany became the day consecrated to baptism[8]. However, Ibn El Sebaʽ wrote that in the first centuries, baptismal rites were held only on one day which was the Holy Friday: the baptized person is buried in the baptismal font in the image of Christ who died and who entered the tomb[9]. Thus, baptism is literally and symbolically not only cleansing, but also dying and rising again with Christ.

On the other hand, Butler and Ceres pointed out that it was forbidden to baptize during the Holy Week, Easter Time (Al-ḫmāsin, الخماسين)[10] as well as during all Lent except on the 6th Sunday of Lent at āḥdāl-tnāṣir, and this was according to the recommendations of Christodolus in the 11th century[11], who was the patriarch that applied baptism[12].

During the era of martyrdom and strong persecution, services took place in houses where baptism was carried out secretly. When Christians were allowed to build churches, they built baptismal tanks[13].

As for the age of the baptized person, in the first centuries he had to wait until the age of 30, exactly like the age of Christ when he was baptized[14]. Since many people died before that age, the newborns were baptized, 40 days after the boy's birth and 80 days for the girl[15].

The Baptistery: Forms, Evolution and Emplacement

The term “baptismal font - baptistery” is derived from the Latin word baptistērium and from the ancient Greek βαπτιστήριον, which comes from the Greek verb βαπτίζω (baptízô). This means “plunges” or “immerses”, while the Latin word fons means “source”, “fountain”[16].

According to the Didaskalia, the building of the font should be located at the end of the north-west aisle of the church, in the narthex to the left of the entrance[17]. However, this habit was not always respected[18]. Some historians explained that there was a difference between the location of the font and the location of the baptismal ceremony[19]. The baptistery usually consisted of a double portico: the baptized person entered the baptistery by one of the doors on the west side, then after baptism and confirmation, he passed through the other door on the east side which overlooked the church to receive the Eucharist[20].

In some early churches, the baptistery consisted of a single room, but in others it contained an adjoining “Myron anointing room” and a vestibule for dressing[21]. It is rare to find a baptistery outside the church building[22], with the exception of the one located in the place of Saint Mina in Mariout; and the one that exists in the Ashmunein Basilica in the northern part of the church and finally the one of Dayr Anba Shenouda (The White monastery) in Sohag, which is located in the northern part of the South aisle outside the church. The latter consisted of a square room, sometimes used as a chapel because it includes a limestone niche dating from the 4th century and which contained a deep font that was accessed by the help of steps[23]. Their importance lies in the fact that they represent Episcopal places or pilgrimage sites[24].

The Forms of the Baptismal Tanks

In certain places, the font stands on a central pillar or a support, which is considered as a symbol of the axis of the world, in others it is raised by four columns - the four cardinal points of the universe - that allude to the four evangelists[25]. The baptismal font is known among the Copts as “the Jordan”[26].

When the baptistery became a single room not separate from the church, it was built in a rectangular or square form that is due to:

1 - The influence of the normal form of rooms built inside houses.

2 - The baptisteries that underwent the same evolutions of cubic frigidarium rooms in public baths (Thermee).

3 - The shape of square or cubic mausoleums[27].

The baptismal fonts are divided into two types:

I - One is dug in the ground. It consists of a basin with stairs on both sides by which the catechumen descends to receive the baptism and an upper step for the priest to apply baptism by immersion[28]. This shape is inspired by the image of the Jordan River which contains marble steps[29].

Several kinds of geometric shapes are derived from this type:

1 - The square-rectangular form represents the shape of the tombs of the martyrs of the first centuries with internal steps and also symbolizes the tomb of Christ[30].

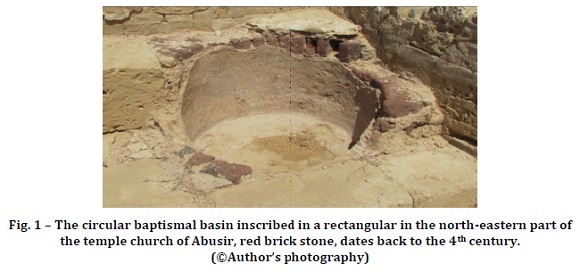

Examples illustrate this aspect as the circular baptismal basin inscribed in a rectangular form without steps, located in the north-eastern part of the temple church of Abusir (Taposiris Magna, Borg El Arab) (Fig. 1) discovered in 1990, which dates back to the 4th and 5th centuries and the reminiscent of the form of the baptistery of the monastery of Saint Simon in Aswan[31].

2 - The hexagonal form refers to the 6th day of the week (Good Friday).

3 - The octagonal, 8th day of the week, evokes the day of the resurrection; a rare form in Egypt.

4 - The cylindrical shape symbolizes the matrix: baptism is the second birth of the church matrix. It also symbolizes eternity: the circle is the infinity of God[32]. This is the most common form, with two steps to get down. There are many examples, such as:

The Basilica in Ashmunein and the North Basilica of Abu Mina in Mariout[33], the patriarchal residence, located in the southern part of the church, surrounded by small chapels and that includes a cylindrical font surmounted by a dome supported by six columns. It dates back to the 6th century[34]. An adjoining baptistery room with three niches in the east was likely to contain the Myron[35].

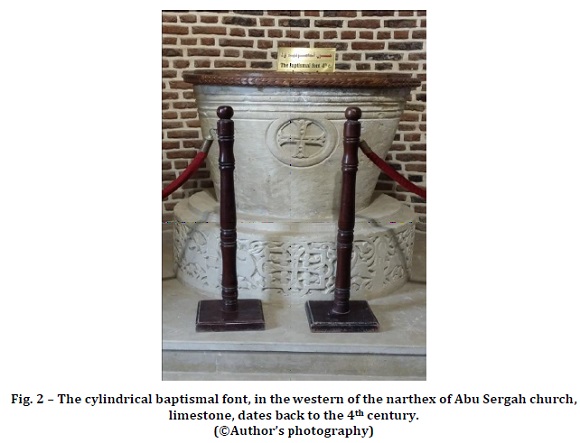

Cylindrical forms without stairs appear in the Old Cairo churches as the one situated in the western of the narthex of Abu Sergah church[36] (Fig. 2), constructed in limestone sculpted in high relief with cross forms, with a pedestal decorated with crosses surrounded by birds and gazelles, placed inside a niche; it dates back to the 4th century.

The exceptional example is the stone baptismal font recently discovered in the south-eastern part inside the Holy Family crypt in Abu Sergah dates back to the 4th/5th centuries[37].

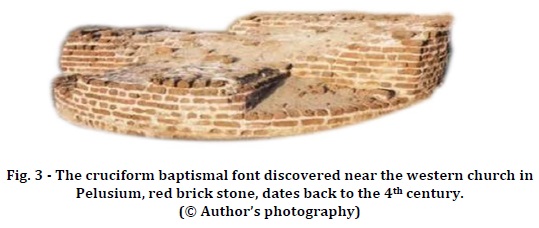

5 - The cruciform shape that symbolizes the crucifixion of Christ, with stairs like the one in Pelusium (Al-Farama) (Fig. 3), discovered near the western church, dates back to the 4th century. These remains exist actually in the north-western side, with a marble sailing and ruins of steps in the eastern and the western of the pool[38].

6 - The shape of four-petal flowers that resemble the cross[39].

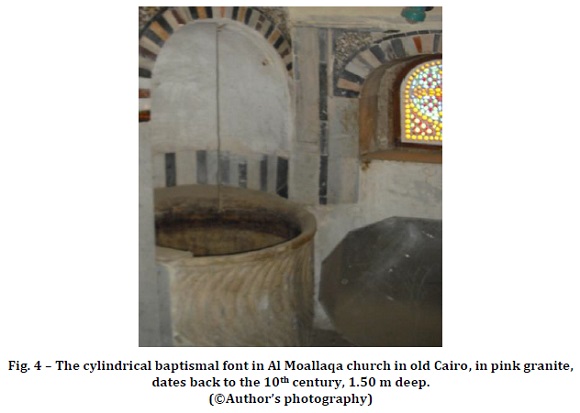

II - The other kind is built above the floor level. It contains a cylindrical basin not deep but which suits children to plunge into the water. It is built in marble or stone, its diameter varies between 0.80 to 1m. It stands on a pedestal fixed to the wall inside the niche usually ornamented by the image of Jesus Christ’s baptism. In this way, water is filled and emptied manually. It is a current model which we find it in Al Moallaqa church in old Cairo. This font goes back to the 10th century (Fig. 4). It is a cylindrical shape in pink granite decorated with lines in the form of waves that represent the hieroglyphic sign of water (MW) fixed to the wall in a niche ornamented with mosaic with different geometrical forms and lotus flowers[40].

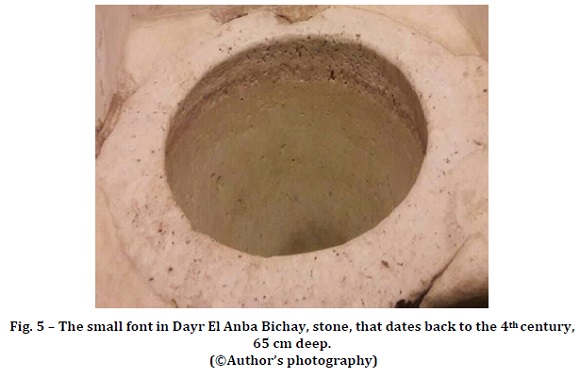

In Abu Hennes at Melawi, the font is dug inside a wall in the western of the north sanctuary with two openings from the two sides that serve in maintaining the jars of the holy oil[41]. In Dayr El Anba Bichay (Red monastery), we find a small font that dates back to the 4th century[42], flanked to the wall without any decorations, only with a small hole in its pedestal that helps to empty the water after baptism (Fig. 5).

In ancient times, the large capitals of columns sometimes served as baptismal basins. A hole was made to clear the water after baptism. The splendid marble capital found in the Coptic Museum in Cairo provides a good example. It was discovered in the ruins of the Suspended Church of Saint Mark in Alexandria, which dates back to the 6th century. It takes the shape of a basket with reliefs of palm trees in the four corners[43].

In the 6th century, a double font was built; one of small size for infants and the other larger for adults, accompanied by an annex that contains the holy oil[44]. The baptistery of Saint Mina at Mariout, west of Martyrium, discovered in 1905-1907, bears witness to this type. It dates back to the 6th century in the time of Pope Timothy and consists of several pieces: the first large square-shaped on the outside and octagonal on the inside. It contains a large circular marble basin, 1.55 m deep and 2.30 m diameter covered with a dome with steps on both sides for adults. Its walls are composed of four niches covered with two layers of mosaics. As for the second, it also consists of several niches, with a small font made for children[45].

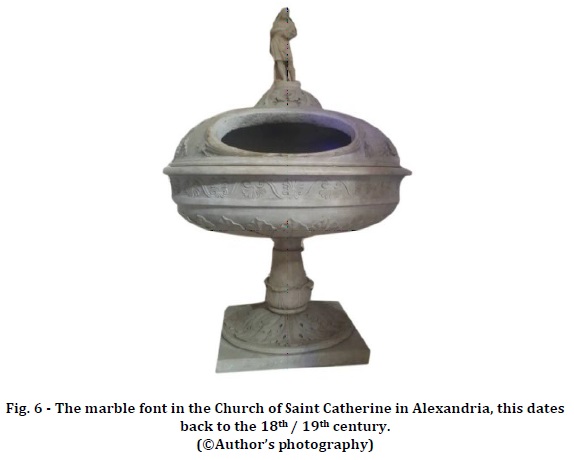

A different type of baptismal font exists in Catholic churches known as the "chalice cup" where the practice of baptism is by aspersion.This font is built of marble and is adorned with different motifs[46], such as that which appears in the font of the Church of Saint Catherine in Alexandria, which dates back to the 18th/ 19th century and is decorated by the statue of Christ, surrounded by high relief motifs[47] (Fig. 6).

Other Examples of Ancient Baptisteries

The “Sultan's Baptistery” found in the Abu Seifein Church in Old Cairo dates back to the 10th century and is erected in stone. It is located to the right of the chapel of Mari Yacub el Mocata', 92 cm deep, 1.58 cm high and 33 cm wide[48].

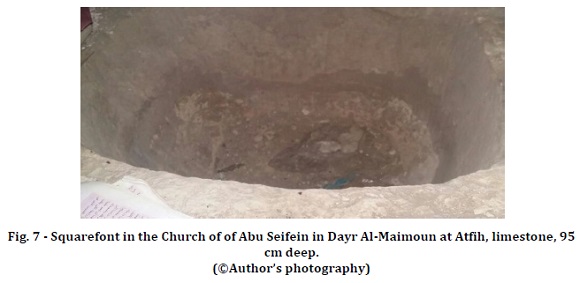

Dayr Al-Maimoun at Atfih embraces two baptismal fonts; one in the church of Saint Anthony placed in the left sanctuary in the shape of a circular limestone, the other is in the church of Abu Seifein a square shaped shallow stone used for children (Fig. 7)[49]. Gothic graffiti of pilgrims with escutcheons decorate their walls[50]. The Wadamon El Armanty Church also contains a circular large hole for emptying the water[51].

The “Laqan” Basin

This basin, which appears in the ancient churches, is used in three ceremonies by the sanctification of water: the eve of the Epiphany (19-20 January), to memorize the baptism of Christ; Holy Thursday, when Christians commemorate the washing of the feet made by Christ to all his Apostles, and the feast of the Apostles (12th of July)[52].

It is a 60 cm long and 30 cm wide tank that is dug into the ground, in the center of the western end of the third khurus[53], of the central nave[54]. It is filled with pure water and a pottery jar is placed at its side. The priest wears the epitrichalion[55] during the ritual[56].

The ancient sources insist on the importance of laqân. Sawiris Ibn El Moqaffa in the 10th century considered the laqân as purgatory and explained in Tartib al-Kahanŵt that all the churches were provided with a basin so that the faithful wash their feet on Holy Thursday[57]. This basin was located to the west of the church, because the priest officiates while directing his eyes during the ritual towards the East in the direction of the sanctuary[58].

Abu El Makarm (12th century), also testified to the presence of laqân at Deir Abu Maqar in Wadi Habib (Wadi El-Natroun). After the celebration of Holy Thursday, the monks took water from the laqân and poured it into the Nile to bless it and thus served its flood[59]. Otherwise, Ibn El Saba (13th century) noted the ritual of laqân in his book, chapter 99, saying that the priest takes a cloth and wraps it round his waist as Jesus has done before (John 13, 4), begins to wash the feet of the faithful and then wipe with the linen with which he is girded[60].

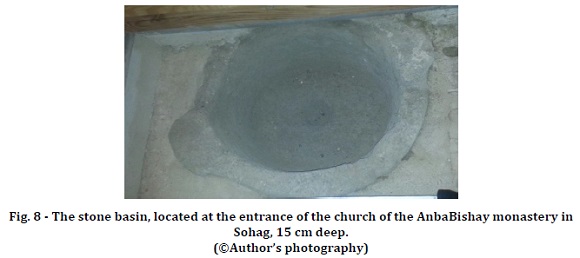

Butler pointed out that the first Christians who entered the church barefoot, following the recommendations of the decree of Pope Christodolus in the 11th century, were to purify their feet in these pools called “basins of purification, washing or ablution”[61]. However, this habit fell into disuse in the 14th century. In fact, these vats recall the basins that were held at the entrance of ancient Egyptian temples[62].

Butler asserted the existence of such basins. Indeed, a stone basin, below the level of pavement, devoted to washing, located at the entrance of the main church of the Anba Bishay monastery (The Red Convent) in Sohag, was discovered in 2017 (Fig. 8)[63].

The Forms of Laqân Basins:

1 - Octagonal form, inscribed in a square, exists to the west of the nave in the temple church of Habou in Luxor and it dates back to the 4th century[64]. The other is at Abu Seifein Church in Old Cairo. It is made of marble, inlaid with red and black marble, 90 cm x 90 cm (length and width), 25 cm deep, decorated on the inside with semi-circular shapes of the four corners[65].

2 - Square shape inscribed in a rectangle with interrupted sides by circular beads, in the church of the Virgin Mary in the village of Oskar in Helwan, and dates back to the 18th/ 19th century[66].

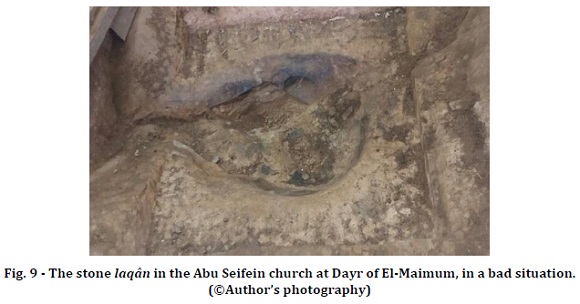

3 - The most famous form in Egypt is the circular laqân inscribed in a rectangle or a square. The oldest was located at the Basilica El Ashmunein in the central nave between the sixth and seventh columns, which dates back to the 4th century[67]. In the monasteries of Wadi El-Natroun, to the west of the central nave of the churches, there is the marble laqân, like that of the Baramus, which dates back to the 7th century, with a depth of 14 cm, 35 cm diameter[68]. It is also found in Anba Bishoy and El-Surian monasteries. At Dayr of El-Maimun, in the Abu Seifein church in front of the entrance, there is a stone laqân (Fig. 9)[69].

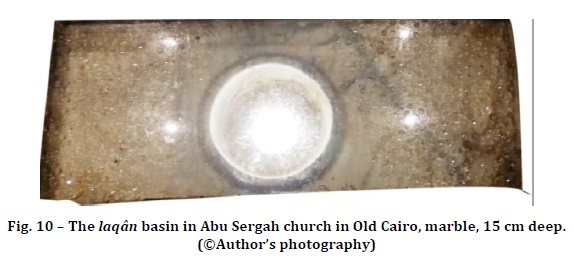

These forms of laqân are also numerous in the old churches of Old Cairo: in El-Moallaqah where a laqân is located west of the central nave between the first and the second column[70]; in the church of Santa Barbara and Abu Sergah (Fig. 10).

El Maghtas (Epiphany Pool):

Formerly, according to an ancient Coptic tradition, a region of the Nile was chosen to plunge in before the Epiphany celebration, and children were brought down there, in spite of the cold, to imitate Christ who had descended into the Jordan[71].

El Maqrizi specified that sometimes several governors participated in the celebration of this festival, as Mohamed Ibn-Tougague in 941 A.D. and some Fatimid Caliphs like El Zaher Aziz Allah. Others completely canceled the celebration, like El-Moazz and El-Aziz. As for El-Hakim (according to his mood), he participated a few times but in 1008 A.D. he promulgated a decree that totally prohibited this kind of celebration[72]. This is why the pool of the Maghtas is currently inside the churches as an alternative to the Nile[73].

In the 10th century, Sawiris Ibn El Moqaffa wrote that the faithful, men and women, required the presence of the Maghtas inside the church to help them to be purified from their sins[74]. Abu El Makarem also mentioned the presence of the Maghtas that was cleaned from sand and filled with water at Abu Maqar Monastery[75]. In turn, Ibn El Seba' in the 13th century, quoted that the Epiphany celebration was held at night, in front of the Maghtas and that it was better to seek water from the Jordan and pour it into the Maghtas[76]. Ibn Kabr confirmed the presence of the Maghtas in the 14th century churches[77].

The Form of el Maghtas:

No details indicate its exact location, outside or inside the church. It is an underground room in cubic, rectangular, round or parallelogram shape, 1.5 m deep. This basin is capped with a wooden cover (no longer used)[78].

Different examples of the Maghtas in the old churches:

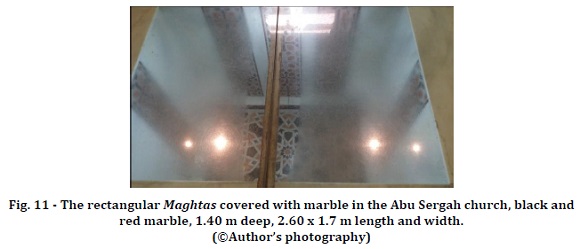

1 - Inside the churches of Old Cairo at Abu Sergah, there is a sumptuous rectangular Maghtas covered with marble (Fig. 11) in the middle of the narthex to the west of the central nave, 1.40 m deep (2.60 x 1.7 m length and width)[79]. It is in laid with black and red marble.

2 - A beautiful Pharaonic lotus shaped Maghtas with circular pearls, located at the ancient church of Saint Mina in Taha El-Ama'da at Samalut, 1.75 m deep,[80] was used until 1975, then it was abandoned because of a strange conflict between two families. Each of these two families sought to descend first into this Maghtas. Then, to take revenge, one of them decided to throw in it pieces of glass. Following this aggressive act, several people were seriously injured; therefore, the priests forbade the use of this Maghtas[81].

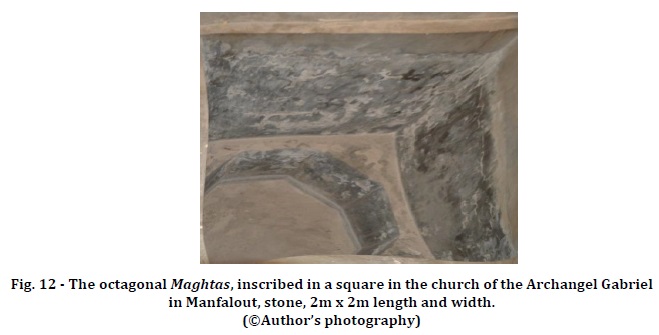

3 - The church of the Archangel Gabriel in the Beni-Magued village in Manfalout, has an octagonal Maghtas, inscribed in a square behind the sanctuaries in the East, 2m x 2m (length and width)[82] (Fig. 12).

4 - In the west wall of a special room at Saint Anthony's Church in Deir El-Maimoun, there is a 2.60 x 2.50 cubic stone Maghtas with two steps[83].

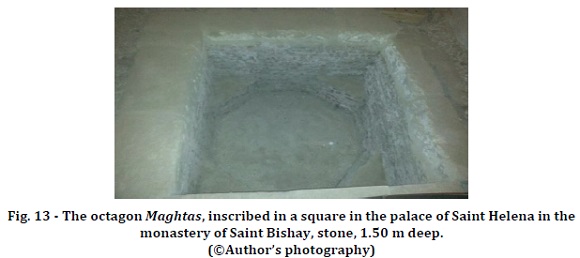

5 - The palace of Saint Helena in the monastery of Saint Bishay (Deir El Ahmar), which is being restored, embraces the ancient monumental Maghtas of stone octagon form inscribed in a square. It was used previously by lay people and not monks[84] (Fig. 13).

6 - In the ancient Monastery of Anba Moussa El Baramus, discovered between 2002 and 2005, which fell into ruins, a 1.5 cubic meter limestone Maghtas was found dug in the plastered rocks, with steps. It appears in a room in the East next to the sanctuary of the second church[85].

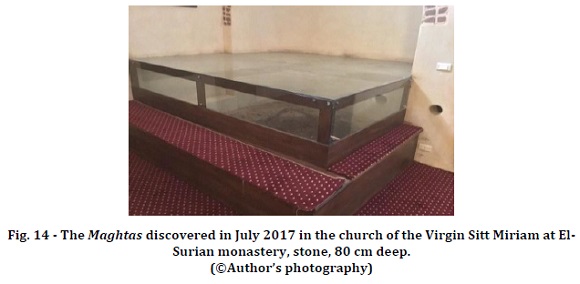

7 - Finally in July 2017, by undertaking extensions to the church of the Virgin Sitt Miriam at El-Surian monastery, accidentally a Maghtas was also discovered towards the western end glued to the wall, 80 cm deep, higher than the ground of the church of two bleachers because this Maghtas belonged to another church (the church of MariRutaʼ)[86] (Fig. 14).

The Pool of Extreme Unction

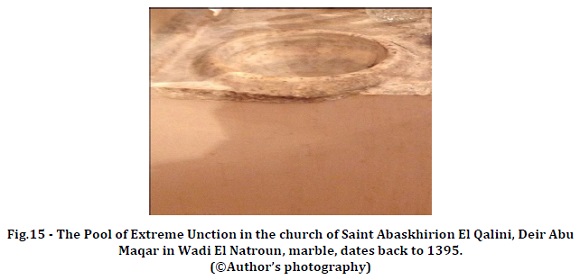

We found only one example of this basin. It is the one that dates back to 1395, and that exists in the church of Saint Abaskhirion El Qalini, Deir Abu Maqar in Wadi El Natroun, in the sanctuary on the left, towards the North-West part, flanked on the wall[87] (Fig. 15).

This demonstration confirms that

1 - The fonts (baptismal vessels) of the ancient Orthodox Coptic churches are varied and totally different from those of the Catholic churches in their structure and form. They are generally simpler than others that are artistically made.

2 - The basin of el laqân and the Maghtas are confined to the Coptic Orthodox Church.

3 - The fonts erected in the monasteries, churches of the province and the countryside are simpler than those built in the urban churches; inlaid with marble and mosaic.

4 - The largest number of basins has fallen into disuse; however, we continue to cover them in glass to preserve them as witnesses of Coptic heritage.

5 - All ancient churches and monasteries contain treasures often hidden that must be discovered, so it would be necessary to conduct continuous excavations in different locations.

The fonts were only used as baptisteries in the first centuries while other fonts were added successively for other uses and celebrations.

In conclusion, the fonts are an authentic legacy that links the past to the present and reflects our traditions. It is a heritage difficult to find elsewhere and of which we should be proud.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

ABŪ AL-MAKARAM - Tāriḫ ālkanā’s wa ālādiraʼ. Edited by Bishop Samuel. Cairo: 1984. [ Links ]

ANWAR, Mary Magdy - “Des pièces représentant les insignes et les vêtements liturgiques coptes conservés dans les musées archéologiques d’Egypte”. Journal of the Faculty of Tourism and Hotels 12 (2015), pp. 13-35 [ Links ]

ATHANASIUS EL MAKARY - Mʽğm ālmṣṭlḥāt ālknsiaʼ. 3 vols. Cairo: Nubar Publishing company, 2002-2011. [ Links ]

AWAD ALLAH, Mancarius - Mnārt ālāqdās fi arḥtqws ālknisaʼālqbṭiaʼwaālqdās. Cairo: ālmṭbʽaāltğāriaʼālḥdiṯa, 1969. [ Links ]

Archibishop BASILIOS - “Baptism”. in The Coptic Encyclopedia. Edited by Aziz S. Atiya, Vol. II. New York: Macmillan publishing company, 1991, pp. 339-342. [ Links ]

Archibishop BASILIOS - “Epiphany (liturgy of)”. in The Coptic Encyclopedia. Edited by Aziz S. Atiya, Vol. III. New York: Macmillan publishing company, 1991, pp. 967-968. [ Links ]

BEATRICE, P. F. - “Foot washing”. in Encyclopedia of Ancient Christianity. Edited by Angelo Di Berardino, Vol. II. Dowhers Grove, Illinois: IVP Academic, 2014, pp. 49-51. [ Links ]

BURMESTER, Oswald Hugh Ewart - A Guide to the Monasteries of the Wadi ‘N-Natrun. Le Caire: Société d’Archéologie Copte, 1954. [ Links ]

BURMESTER, Oswald Hugh Ewart - A Guide to the Ancient Coptic Churches of Cairo. Le Caire: Société d’Archéologie Copte, 1955. [ Links ]

BURMESTER, Oswald Hugh Ewart-The Egyptian or Coptic Church (A detailed description of her liturgical services and the rites and ceremonies observed in the administration of her sacraments). Le Caire: Société d’Archéologie Copte, 1967. [ Links ]

BUTLER, Alfred - The Ancient Coptic Churches in Egypt. Translated by Ibrahim Salama Ibrahim, 2 vols. Cairo: ālhiaaʼālʽmallktāb, 2001. [ Links ]

CAPUANI, Massimo - Christian Egypt: Coptic Art and Monuments Through Two Millenia. Cairo: AUC Press, 2002. [ Links ]

CHEVALIER, Jean; GHEERBRANT, Alain - A Dictionary of Symbols. Translated by John Buchanan-Brown. Oxford (USA): Basil Blackwell, 1994. [ Links ]

COQUIN, Charalambia - Les Edifices chrétiens du Vieux Caire. Vol. I (Bibliographie et topographique historiques). Tome XI. Le Caire: Institut Français d’Archéologie du Caire, 1974. [ Links ]

CROSS, F. L. - The Oxford Dictionary of the Christian Church. Oxford: Oxford UniversityPress, 1990. [ Links ]

DAOUAD, Nabih; FAKHRY, Adel - Tāriḫ ālmsiḥiʼ waālrhbnaʼ waʼātārhmā fi āibāraitālğizaʼ. Cairo: Saint Marc Foundation of Coptic history, 2011. [ Links ]

DUVAL, N. - “Church buildings: baptistery”. in Encyclopedia of Ancient Christianity, edited by Angelo Di Berardino, Vol. II. Dowhers Grove, Illinois: IVP Academic, 2014, pp. 524-537. [ Links ]

EL FARAS, Robert - Mbānymnbḫwr (knāʼs waādirt mṣriaʼ). Cairo: ālhiaʼālʽmāllqṣwrālṯqāfaʼ, 2012. [ Links ]

EL HEWMY, Youssef - ālāḥtfālbʽ idālġṭāsālmğid (Epiphania) fi ktbālmwrḫinālʽrb. Alexandria-Cairo: Biblioteca Alexandrina, 2016. [ Links ]

EL MAQRIZI - Ktāb ālmwāʽz waālʽtbār fi ḏkr ālḫṭṭ waālaʼṯār. Edited by Ayman Fouad El Saïd. London: ālfrqān institute, 2002. [ Links ]

EL MESKIN, Matta - ālrhbnaʼ ālqbṯiaʼ fi ʼaṯr ālqdis AbwMaqār. Wadi El Natrun, Egypt: Monastery of Saint Maqar, 1972. [ Links ]

EL MESKIN, Matta - ālmʽmwdiaʼ (ālāṣwl ālāwly llmsiḥin). Wadi El Natrun, Egypt: Monastery of Saint Maqar, 2000. [ Links ]

EVELYN WHITE, H. G. - The Monasteries of the Wadi N-Natrun, Part III (The Architecture and Archeology). New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1973. [ Links ]

GARIN, Alberto - Abu Sirga: la iglesia copta de San Sergio y San Baco del Viejo Cairo: las primeras huellas del cristianismo en Egipto. Madrid: Ministerio de Asuntos Exteriores, Agencia Española de Cooperación Internacional, Fundación Carolina, El Viso, 2004. [ Links ]

GODLEWSKI, W - “Baptistery (Architectural elements of churches)”. in The Coptic Encyclopedia. Edited by Aziz S. Atiya, Vol I. New York: Macmillan publishing company, 1991, pp. 197-200. [ Links ]

GROSSMANN, Peter - “Epiphany Tanks”. in The Coptic Encyclopedia. Edited by Aziz S. Atiya. Vol. III. New York: Macmillan publishing company, 1991, p. 968. [ Links ]

GROSSMANN, Peter - “Abu Mina”. in The Coptic Encyclopedia. Edited by Aziz S. Atiya. Vol I. New York: Macmillan publishing company, 1991, pp. 24-29. [ Links ]

GROSSMANN, Peter - “Khūrus”. in The Coptic Encyclopedia. Edited by Aziz S. Atiya, vol. I. New York: Macmillan publishing company, 1991, pp. 212-213. [ Links ]

GROSSMANN, Peter - “A new church at Taposiris MagnaAbusir”. Bulletin de la Société d’Archéologie Copte 31 (1992), pp. [ Links ] 24-30.

GROSSMANN, Peter; HAFEZ, Mohamed - “Results of the 1997 excavations in the North-West church of Pelusium (Faramawest)”. Bulletin de la Société d’Archéologie Copte 40 (2001), pp. 109-116. [ Links ]

GROSSMANN, Peter; KOSCIUK, Jacek - “Report on the excavations at Abu Mina in spring 2000”. Bulletin de la Société d’Archéologie Copte 40 (2001), pp. 97-108. [ Links ]

GUIRGUIS, Habib - Āsrār ālknisaʼ ālsbʽa. Cairo: El Tawfik Coptic Publisher,1934. [ Links ]

GUIRGUIS, Benjamin - Ttbʽtāriḫy lāğrāʼāt srālmʽmwdiaʼ ālmqds ldy ālāqbā ālārṯwḏk. Cairo: Institut of Coptic studies, n.d. Master unpublished. [ Links ]

HABIB, George - Almʽmwdiaʼ fi ālknisaʼāwāḥdh ālğmʽaʼ ālrswliaʼ. 1st book. Cambridge: 2012. [ Links ]

HELMY, Bishoy - Knisty ālārṯksiaʼ..mā āğmlk‼ Cairo: Nubar Publishing Company, 2013. [ Links ]

IBN ALMOQAFFAʽ - Die Ordnung des Priestertums ein altes liturgisches Handbuch der koptischen Kirche (Tartīb al-Kahanūt). II Teil. Edited by Julius Assfalg. Le Caire: Publications du Centre d’Etudes Orientales de la Custodie Franciscaine de Terre Sainte, 1955. [ Links ]

IBN ELSEBAʽ- Ktāb ālğwhraʼ ālnfisaʼ fi ʽlm ālknisaʼ. Edited by Victor Mansur El-Francicie. Le Caire: Institut Franciscaine chrétienne orientale, 1966. [ Links ]

IBN IAA’S - Bdāʽ ālzhwr fi wqāʽ āldhwr. Cairo: Dārālktb, 2008. [ Links ]

IBN KABR - Msbāḥ ālzlmʼ fi āidāḫ ālḫdmʼ. Edited by Samuel El Suriany. Cairo: Dayr al-Suryan 1992. [ Links ]

INNEMÉE, Karel - Excavations at the site of Deir Al-Baramus 2002-2005. Leiden: Leiden University, 2005. [ Links ]

KHALIL, Morcos - Ālqdis ālʽzim ālahid Filwbātir Mrqūriũs ālahir baby Sifin. Cairo: AnbaRwiyas Publisher, 1995. [ Links ]

KILLEN, William - The Ancient Church: Its History. Doctrine, Worship and Constitution. Alexandria: The Library of Alexandria, 2005 (Original Publishing 1859). [ Links ]

MALATY, Tadros - Alknisaʼ bit Allah. Alexandria: church of Saint Georges Sporting, 1979. [ Links ]

MARTIN, Maurice - Monastères et Sites Monastiques d’Egypte. Le Caire: Institut Français d’Archéologie Orientale, 2015. [ Links ]

MOHAMED, Hagagy - “āllaqān fi ālknisaʼsālāṯriaʼ mn ālGizaʼḥty Aswān”. Journal of the faculty of Arts in Tanta (n.d): pp. 819-823. [ Links ]

MULDER, Nicole. F. - “The early Christian Pilgrimage: The Case of Abu Mena”. Essays on Coptic Art and Culture 1 (1994), pp. 18-35. [ Links ]

PERKINS, Ward - “The Monastery of Taposiris Magna”. Bulletin de la Société Royale d’Archéologie d’Alexandrie 36 (1944), pp. 48-53. [ Links ]

QASD ALLAH, Nusrat - Tāṯir āsālib wa ṭrqālānaaʼʽlyāltʽbirālmʽmāry llʽmārʼ. Cairo: Ain Shams University, Faculty of Engineering, 2006. Master unpublished. [ Links ]

Bishop SAMUEL - Dlilāl knās wa ālādiraʼ ālqdimh fi mṣr. Vol. I. Cairo: 2002. [ Links ]

SIMAIKA, Marcus - A Brief Guide to the Coptic Museum and the Ancient Coptic Churches and Monasteries. 2 vols. Cairo: El Amiriaʼ publishing, 1932. [ Links ]

STATY, Essam - Mqdmaʼ ālfwlklwr ālqbṭy. Cairo: ālhiāālmṣriaʼālʽmaʼllktāb, [ Links ] 2010.

TROSTYANSKIY, Sergey - “Baptism”. in The Encyclopedia of Easter Orthodox Christianity. Edited by John Anthony Mcguckin, Vol I. Singapore: Wiley Blackweell, 2011, pp. 65-67. [ Links ]

VIAUD, Gerard - La liturgie des coptes d’Egypte. Paris: Librairie d’Amérique et d’Orient, 1978. [ Links ]

WACE, Alan John Bayard - Hermopolis Magna, Ashmunein: the Ptolemaic sanctuary and the basilica. Alexandria: Alexandria University Press, 1959. [ Links ]

WALTERS, Colin Christopher - Monastic Archeology in Egypt. Warminster: Aris et Phillips, 1974. [ Links ]

WASSEF, Céres W. - Pratiques rituelles et alimentaires coptes. Le Caire: Institut Français d’Archéologie Orientale, 1971. [ Links ]

YOUSSEF, Hanan - Tṭwrʽm ārtālṭrāz ālbāziliky fi mṣr fi ālʽṣrālrwmāny. Tanta: Tanta University, faculty of Arts, 2008. Master unpublished. [ Links ]

YOUSSEF, Samer - Tāṯir ālātğāht ālʽqādiaʼʽlytṣ mim ālknisa. Cairo: Helwan University, faculty of Arts, 2004-2005. Master unpublished. [ Links ]

YOUSSEF, Youhanna - “The Book Order of the Priesthood, by Severus Ibn Al-Muqaffaʼ Bishop of Al-Ashmunein”. Bulletin de la Société d’ Archéologie Copte 45 (2006), pp. 135-145. [ Links ]

Como citar este artigo | How to quote this article:

ANWAR, Mary Magdy - “The Evolution of Different Fonts in the Coptic Churches Throughout the Centuries”. Medievalista 28 (Julho - Dezembro 2020), pp. 335-362. Disponível em https://medievalista.iem.fcsh.unl.pt.

Data recepção do artigo / Received for publication: 10 de Fevereiro de 2020

Data aceitação do artigo / Accepted in revised form: 15 de Maio de 2020

[1] GUIRGUIS, Benjamin - Ttbʽtāriḫylāğrāʼātsrālmʽmwdiaʼālmqdsldyālāqbāālārṯwḏk. Cairo: Institut of Coptic studies, n.d. Master unpublished., p.95; GUIRGUIS, Habib - Āsrārālknisaʼālsbʽa. Cairo: El Tawfik Coptic Publisher, 1934, p. 44.

[2] TROSTYANSKIY, Sergey - “Baptism”. in The Encyclopedia of Easter Orthodox Christianity. Edited by John Anthony Mcguckin, vol. I. Singapore: Wiley Blackweell, 2011, pp. 65-67.

[3] WASSEF, Céres. W. - Pratiques rituelles et alimentaires coptes. Le Caire: Institut Français de l’Archéologie Orientale, 1971, p.156.

[4] TROSTYANSKIY, Sergey - “Baptism” …, p. 66.

[5] WASSEF, Céres. W. - Pratiques rituelles …, pp. 156-157.

[6] VIAUD, Gerard - La liturgie des coptes d’Egypte. Paris: Librairie d’Amérique et d’Orient, 1978, pp. 78-79.

[7] El MESKIN, Matta - ālmʽmwdiaʼ (ālāṣwlālāwlyllmsiḥin). Wadi El Natrun, Egypt: Monastery of Saint Maqar, 2000, p.322; KILLEN, William - The Ancient Church: Its History. Doctrine, Worship and Constitution. Alexandria: The Library of Alexandria, 2005, p. 306.

[8] BASILIOS -“Baptism”. in The Coptic Encyclopedia. Edited by Aziz S. Atiya, Vol. II. New York: Macmillan publishing company, 1991, pp. 339-342; BUTLER, Alfred - The Ancient Coptic Churches in Egypt. Translated by Ibrahim Salama Ibrahim, vol. II. Cairo: ālhiaaʼālʽmallktāb, 2001, p. 208.

[9] IBN EL SEBAʽ- Ktābālğwhraʼālnfisaʼ fi ʽlmālknisaʼ. Edited by Victor Mansur El-Francicie. Le Caire: Institut Franciscaine chrétienne orientale, 1966, p. 78.

[10] WASSEF, Céres W. - Pratiques rituelles …, p. 157.

[11] BUTLER, Alfred - The Ancient Coptic Churches …, vol. II, pp. 208-213; CROSS, F.L. - The Oxford Dictionary of the Christian Church. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1990, p.126.

[12] DUVAL, N. - “Church buildings: baptistery.” in Encyclopedia of Ancient Christianity. Edited by Angelo Di Berardino, vol. II. Dowhers Grove, Illinois: IVP Academic, 2014, pp.524-537.

[13] HABIB, Georges - Almʽmwdiaʼ fi ālknisaʼāwāḥdhālğmʽaʼālrswliaʼ. 1st book. Cambridge: 2012, p.113.

[14] IBN EL SEBAʽ - Ktābālğwhraʼālnfisaʼ…, p. 78.

[15] BASILIOS - “Baptism” …, p. 338.

[16] ATHANASIUS EL MAKARY - Mʽğmālmṣṭlḥātālknsiaʼ. Vol. III. Cairo: Nubar Publishing company, 2002, p. 233.

[17] BURMESTER, Oswald Hugh Ewart - A Guide to the Ancient Coptic Churches of Cairo. Le Caire: Société d’Archéologie Copte, 1955, p. 14; MALATY, Tadros - Alknisaʼ bit Allah. Alexandria: church of Saint Georges Sporting, 1979, p. 402; EL FARAS, Robert - Mbāny mn bḫwr (knāʼswaādirt mṣriaʼ). Cairo: ālhiaʼālʽmāllqṣwrālṯqāfaʼ, 2012, p. 39.

[18] GODLEWSKI, W. - “Baptistery (Architectural elements of churches)”. in The Coptic Encyclopedia. Edited by Aziz S. Atiya, vol. I. New York: Macmillan publishing company, 1991, pp.197-200.

[19] ATHANASIUS EL MAKARY - Mʽğm ālmṣṭlḥāt ālknsiaʼ. Vol. I. Cairo: Nubar Publishing company, 2011, p. 342.

[20] AWAD ALLAH, Mancarius - Mnārt ālāqdās fi arḥtqws ālknisaʼālqbṭiaʼwaālqdās. Cairo: ālmṭbʽaāltğāriaʼālḥdiṯa, 1969, p. 105; QASD ALLAH, Nusrat - Tāṯir āsālib wa ṭrq ālānaaʼʽlyāltʽbirālmʽmāryllʽmārʼ. Cairo: Ain Shams University, Faculty of Engineering, 2006. Master unpublished, p. 12.

[21] DUVAL, N. - “Church buildings” …, p. 534.

[22] ATHANASIUS EL MAKARY - Mʽğm ālmṣṭlḥāt …, p.343.

[23] WALTERS, Colin Christopher - Monastic Archeology in Egypt. Warminster: Aris et Philips, 1974, p.73; BUTLER, Alfred - Ancient Coptic Churches…, p. 289.

[24] GODLEWSKI, W - “Baptistery (Archeological elements of churches)” …, p. 197.

[25] CHEVALIER, Jean; GHEERBRANT, Alain - A Dictionary of Symbols. Translated by John Buchanan-Brown. Oxford (USA): Basil Blackwell, 1994, p. 397.

[26] GUIRGUIS, Benjamin - Ttbʽtāriḫy…, p. 182.

[27] El MESKIN, Matta - ālmʽmwdiaʼ (ālāṣwlālāwlyllmsiḥin). Wadi El Natrun, Egypt: Monastery of Saint Maqar, 2000, p. 329.

[28] YOUSSEF, Samer - Tāṯir ālātğāht ālʽqādiaʼʽly tṣmim ālknisa. Cairo: Helwan University, faculty of Arts, 2004-2005. Master unpublished, p. 145; GUIRGUIS, Benjamin-Ttbʽtāriḫy, pp. 188-189.

[29] YOUSSEF, Hanan - Tṭwrʽmārtālṭrāz ālbāziliky fi mṣr fi ālʽṣr ālrwmāny. Tanta: Tanta University, faculty of Arts, 2008. Master unpublished, p. 322.

[30] GUIRGUIS, Benjamin - Ttbʽtāriḫy…, p. 187; HELMY, Bishoy - Knisty ālārṯksiaʼ..mā āğmlk‼ Cairo: Nubar Publishing Company, 2013, p. 62.

[31] PERKINS, Ward - “The Monastery of Taposiris Magna”. Bulletin de la Société Royale d’Archéologie d’Alexandrie 36 (1944), pp. 48-53; GROSSMANN, Peter - “A new church at Taposiris MagnaAbusir”. Bulletin de la Société Royale d’Archéologie d’Alexandrie 31 (1992), pp. 24-30.

[32] MALATY, Tadros - Alknisaʼ bit Allah…, p. 407; EL FARAS, Robert - Mbāny mn bḫwr…, p. 40.

[33] GODLEWSKI, W. - “Baptistery” …, p. 199.

[34] GROSSMANN, Peter - “Abu Mina.” in The Coptic Encyclopedia. Edited by Aziz S. Atiya, vol. I. New York: Macmillan publishing company, 1991, pp. 24-29.

[35] Bishop SAMUEL - Dlilāl knās wa ālādiraʼ ālqdimh fi mṣr. Vol. I. Cairo: 2002, p. 37.

[36] SIMAIKA, Marcus - A Brief Guide to the Coptic Musueum and the Ancient Coptic Churches and Monasteries. 2 vols. Cairo: El Amiriaʼpublishing, 1932, p. 211; COQUIN, Charalambia - Les Edifices chrétiens du Vieux Caire. Vol. I. Le Caire: Institut Français d’Archéologie Orientale, 1974, p. 103.

[37] CAPUANI, Massimo - Christian Egypt: Coptic Art and Monuments Through Two Millenia. Cairo: AUC Press, 2002, p.108; GARIN, Alberto - Abu Sirga: la iglesia copta de San Sergio y San Baco del Viejo Cairo: las primeras huellas del cristianismo en Egipto. Madrid: Ministerio de Asuntos Exteriores, Agencia Española de Cooperación Internacional, Fundación Carolina, El Viso, 2004, p. 35.

[38] GROSSMANN, Peter; HAFEZ, Mohamed -“Results of the 1997 excavations in the North-West church of Pelusium (Faramawest).” Bulletin de la Société d’Archéologie Copte 40 (2001), pp. 109-116.

[39] El MESKIN, Matta - ālmʽmwdiaʼ…, pp. 323-324.

[40] SIMAIKA, Marcus - A Brief Guide to the Coptic Museum…, p. 190; BURMESTER, Oswald Hugh Ewart - A Guide do The Ancient Coptic Churches …, p. 30; BUTLER, Alfred - The Ancient Coptic Churches…, p. 195.

[41] Visit on the field.

[42] WALTERS, Colin Christpher - Monastic Archeology …, pp. 73-74.

[43] Visit on the field.

[44] DUVAL, N. - “Church buildings” …, p. 534.

[45] MULDER, Nicole F. - “The early Christian Pilgrimage: The Case of Abu Mena”. Essays on Coptic Art and Culture 1 (1994), pp. 18-35; GROSSMANN, Peter; KOSCIUK, Jack -“Report on the excavations at Abu Mina in spring 2000”. Bulletin de la Société d’Archéologie Copte 40 (2001), pp. 97-108.

[46] YOUSSEF, Samer - Tāṯir ālātğāht…, p. 141.

[47] Visit on the field.

[48] KHALIL, Morcos - Ālqdis ālʽzim ālahid Filwbātir Mrqūriũs ālahir bāby Sifin. Cairo: AnbaRwiyas Publisher, 1995, p. 109.

[49] DAOUAD, Nabih; FAKHRY, Adel - Tāriḫālmsiḥiʼwaālrhbnaʼwaʼātārhmā fi āibāraitālğizaʼ. Cairo: Saint Marc Foundation of Coptic history, 2011, p.361.

[50] MARTIN, Maurice - Monastères et Sites Monastiques d’Egypte. Le Caire: Institut Français d’Archéologie Orientale, 2015, p. 69.

[51] Visit on the field.

[52] VIAUD, Gerard - La liturgie des coptes…, p.76.

[53] Khurus (greek choros) presumably derived from a row of columns, unconnected to the ceiling, that was set up in front of the opening of the apse and whose purpose was purely aesthetic, to enrich the appearance of apsidal openings that in some churches appeared small. It can be as a row in the western wall (as a type of cancelli). GROSSMANN, Peter - “Khūrus”. in The Coptic Encyclopedia. Edited by Aziz S. Atiya, vol. I. New York: Macmillan publishing company, 1991, pp. 212-213.

[54] Archibishop BASILIOS - “Epiphany (liturgy of)”. in The Coptic Encyclopedia. Edited by Aziz S. Atiya, vol. III. New York: Macmillan publishing company, 1991, pp. 967-968; MOHAMED, Hagagy - “āllaqān fi ālknisaʼsālāṯriaʼmn ālGizaʼḥty Aswān”. Journal of the faculty of Arts in Tanta (n.d), pp. 819-823.

[55] Epitrichalion of the priest named sadriah is a long band that covers the chest and a small part of which descends on the back, with an interlock in the middle for the head [ANWAR, Mary Magdy - “Des pieces représentant les insignes et les vêtements liturgiques coptes conservés dans les musées archéologiques d’Egypte”. Journal of the Faculty of Tourism and Hotels 12 (2015), pp. 13-35].

[56] BURMESTER, Oswald Hugh Ewart - The Egyptian or Coptic Church (A detailed description of her liturgical services and the rites and ceremonies observed in the administration of her sacraments). Le Caire: Société d’archéologiecopte, 1967, pp. 256-261.

[57] YOUSSEF, Youhanna - ”The Book Order of the Priesthood, by Severus Ibn Al-Muqaffaʼ Bishop of Al-Ashmunein”. Bulletin de la Société d’Archéologie Copte 45 (2006), pp. 135-145.

[58] IBN AL MOQAFFAʽ - Die Ordnung des Priestertums ein altes liturgisches Handbuch der koptischen Kirche (Tartīb al-Kahanūt). II Teil. Edited by Julius Assfalg. Le Caire: Publications du Centre d’Etudes Orientales de la Custodie Franciscaine de Terre Sainte, 1955, p.20.

[59] ABŪ AL-MAKARAM - Tāriḫ ālkanā’s wa ālādiraʼ. Edited by Bishop Samuel, vol.1. Cairo: 1984, p. 100.

[60] IBN EL SEBAʽ - Ktāb ālğwhraʼālnfisaʼ…, p.333.

[61] BUTLER, Alfred - The Ancient Coptic Churches …, pp. 35-36.

[62] QASD ALLAH - Tāṯir āsālib…, p. 14.

[63] Visit on the field.

[64] YOUSSEF, Hanan - Tṭwrʽmārtālṭrāz …, p. 263.

[65] BURMESTER, Oswald Hugh Ewart - A Guide to the Ancient Coptic Churches …, p. 42.

[66] Bishop SAMUEL - Dlilāl knās …, p. 26.

[67] WACE, Alain John Bayard - Hermopolis Magna, Ashmunein: the Ptolomaic sanctuary and the basilica. Alexandria: Alexandria University Press, 1959, p. 38.

[68] EVELYN WHITE, H. G. - The Monasteries of the Wadi ‘N-Natrun, Part III (The Architecture and Archeology). New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1973, p. 146; BURMESTER, Oswald Hugh Ewart - A Guide to the Monasteries of the Wadi ‘N-Natrun. Le Caire: Société d’archéologiecopte, 1954, p. 26.

[69] DAOUAD, Nabih; FAKHRY, Adel - Tāriḫ ālmsiḥiʼwa ālrhbnaʼ…, p. 361.

[70] BURMESTER, Oswald Hugh Ewart - A Guide to the Ancient Coptic Churches …, p. 26.

[71] GROSSMANN, Peter - “Epiphany Tanks”. in The Coptic Encyclopedia. Edited by Aziz S. Atiya, vol. III. New York: Macmillan publishing company, 1991, p. 968; STATY, Essam - Mqdmaʼ ālfwlklwr ālqbṭy. Cairo: ālhiāālmṣriaʼālʽmaʼllktāb, 2010, p. 119.

[72] EL MAQRIZI - Ktāb ālmwāʽz waālʽtbār fi ḏkr ālḫṭṭ waālaʼṯār. Edited by Ayman Fouad El Saïd, vol. I. London: ālfrqān institute, 2002, pp. 256-266; IBN IAA’S - Bdāʽ ālzhwr fi wqāʽ āldhwr. Vol. I. Cairo: Dārālktb, 2008, p. 190.

[73] WASSEF, Céres. W. - Pratiques rituelles …, p. 192.

[74] IBN AL MOQAFFAʽ - Die Ordnung des Priestertums …, p. 18.

[75] ABŪ AL-MAKARAM - Tāriḫālkanā’…, p. 98.

[76] IBN EL SEBAʽ - Ktābālğwhraʼālnfisaʼ…, p. 313.

[77] IBN KABR - Msbāḥālzlmʼ fi āidāḫālḫdmʼ. Edited by Samuel El Suriany. Cairo: Dayr al-Suryan, 1992, p. 227.

[78] BURMESTER, Oswald Hugh Ewart - The Egyptian or Coptic Church…, pp. 251-252.

[79] GROSSMANN, Peter - “Epiphany Tanks”, p. 968; BURMESTER, Oswald Hugh Ewart - A Guide to the Ancient Coptic Churches…, p. 19.

[80] Bishop SAMUEL - Dlilālknās …, p. 53.

[81] EL HEWMY, Youssef - ālāḥtfālbʽidālġṭāsālmğid (Epiphania) fi ktbālmwrḫinālʽrb. Alexandria-Cairo: Biblioteca Alexandrina, 2016, p. 18.

[82] YOUSSEF, Samer - Tāṯir ālātğāht ālʽqādiaʼʽ…, p. 150.

[83] Visit on the field.

[84] Visit on the field.

[85] INNEMÉE, Karel - Excavations at the site of Deir Al-Baramus 2002-2005. Leiden: Leiden University, 2005, p. 4.

[86] Visit on the field - first publication.

[87] EVELYN WHITE, H. G. - The Monasteries of the Wadi ‘N-Natrun …, p. 117; El MESKIN, Matta - ālrhbnaʼ ālqbṯiaʼ …, pp. 675-676.