Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Acessos

Acessos

Links relacionados

-

Similares em

SciELO

Similares em

SciELO

Compartilhar

Observatorio (OBS*)

versão On-line ISSN 1646-5954

OBS* vol.13 no.1 Lisboa mar. 2019

"Who Does Not Dare, Is a Pussy." A Textual Analysis of Media Panics, Youth, and Sexting in Print Media

Burcu Korkmazer*, Sofie Van Bauwel*, Sander De Ridder*

*Centre for Cinema and Media Studies, Ghent University, Belgium

ABSTRACT

The social media use of young people has become a site of increasing public interest. Young people experiencing with sexuality and intimacy in digital media spaces, has evoked public debates on youth, sexuality and social media. Sexting in particular, has often been covered in print media articles as a 'risky' youth phenomenon, leading to media panics about the alleged risks of social media. Although the social media use of young people has been studied in previous research, there remains a need to understand the broader cultural discourses on youth, sexuality and social media in print media. With this article, we examine the discourses in news stories covering sexting. The qualitative research design of this paper exists of a textual analysis of print media articles. Our findings show that public discourses in newspapers and magazines mainly articulate youth sexting as a deviant behavior. This deviance discourse is strongly linked to a gendered representation of youth who engage in sexting, resulting in a victimization of girls and criminalization of boys. The article concludes that the binary discourse in print media may not only reinforce sexual double standards, but also leaves little space for a more diverse and active comprehension of sexting.

Keywords: Youth; sexuality; sexting; media panic; print media; social media

Introduction

"An increasing number of teenagers are texting sexy messages or even nudes to each other. As it is difficult to see that you are crossing boundaries on a mobile phone screen, sexting is a practice that is not that innocent." (Debruyne, 2012, 3 October, p. 64) [1]

Current media discourses on young people's social media use are heavily framed around 'risk' (Pascoe, 2011), and young people's sexual experiences in the context of social media are believed to be especially 'risky' (Gilbert, 2007; Naezer, 2017). News stories covering youth and their mediated sexual practices have, in the past five years, paid significant attention to one phenomenon in particular, namely sexting. Sexting is a recent neologism, combining the words 'sex' and 'texting,' referring to "the interpersonal exchange of self-produced sexualized texts and above all images via cell phone or the internet" (Döring, 2014, p. 1). It is claimed to be a very popular practice within young people's peer groups (Best & Bogle, 2014; De Ridder, 2017; Ringrose & Harvey, 2015).

News stories, such as the one cited at the beginning of this paper, often imply that sexting is widespread and only growing in significance by stating that "who does not dare [to sext], is considered to be a pussy" (Debruyne, 2012, 3 October, p. 64). Moreover, such stories also place a particular value on sexting; i.e., sexting is oftentimes framed as dangerous and therefore inappropriate sexual behavior (Best & Bogle, 2014). As such, news coverage in media may reinforce the message that young people are making bad decisions when it comes to their sexual experiences via social media. The combination of youth, sexuality, and social media is being represented, and thus is perceived, as a 'dangerous mix'. Such discourses may lead to moral panics about the alleged risks of the internet for young people (Pascoe, 2011). This paper argues that it is crucial to inquire into news media discourses on youth, sexuality, and social media in order to comprehend meanings related to young people's heavily mediated digital lives. As Livingstone, Mascheroni, and Staksrud (2015) argued, social norms and values on young people's social media uses cannot be separated from media representations. Mass media, including print media, are constructing norms and values on 'childhood,' 'good parenting,' 'the nature of risk,' and 'sexuality.' Media representations are abundant in culture and society, and therefore construct what it means for young people to 'sext' (De Ridder, 2017).

The role of media representations have only rarely been studied (Hasinoff, 2013). Most research has focused on young people's uses of social media. These studies analyzed youth's social media uses from feminist and queer theory perspectives (Attwood, 2011; De Ridder & Van Bauwel, 2013; Gill, 2007; Ringrose, 2011), but also from psychological (Cedillo & Ocampo, 2016; Etgar & Amichai-Hamburger, 2017) and youth studies perspectives (Bauermeister, 2013; Levine, 2013). Although these studies have been contributing greatly to our understanding of young people's social media uses and sexuality, there is need for understanding the broader cultural discourses in print media's representations of youth, sexuality and social media.

This paper aims to explore dominant discourses in print media on youth sexuality and social media by specifically examining youth sexting. We will use Döring's (2014) conceptualization, which argues that sexting has been framed by academics as either deviant or normal behavior. With this conceptual framework in mind we will conduct a textual analysis on the print media articles. We will analyze the dominant discourses on sexting and pay particular attention to how this discourse is gendered, while remaining attentive to how the agency of young people is discussed. As previous research has argued, focusing on agency is crucial, as young people are usually framed as passive victims (Angelides, 2013; Thiel-Stern, 2009), thereby stigmatizing those who are sexting (De Ridder, 2017). This paper draws on a textual analysis of news articles published in newspapers and magazines in Flanders (Northern Belgium) between 1 January 2009 and 31 December 2016.

Social Media, Youth, and Media Panics

Social media play an important role in the everyday lives of young people. Online communication via digital media has become a way of connecting with peers, which is leading to young people's public as well as private experiences being expressed via digital media platforms (Gabriel, 2014; Osgerby, 2004). Through these channels, they represent themselves, make moral decisions, and negotiate their identities, friendships, and sexuality. As Gabriel (2014) states, social media present young people with new possibilities for expression, social relations, and identity performance. Following this, the social media use of youngsters has become a site of increasing public interest. However, as research has shown, public discourses are rarely discussing the opportunities presented by social media, and are generally focusing on the associated risks instead (Gilbert, 2007; Ringrose, 2011; Albury, Crawford & Byron, 2013).

News stories express concern about the potential harm that social media might cause to young people, especially to young girls (Buckingham & Jensen, 2012; Ringrose, 2011). Girls' social media practices are usually central to the discursively constructed panic in the media (Dobson, 2015). Such discourses are known for victimizing young girls as passive subjects, therefore making them blame-worthy social media users (Thiel-Stern, 2009). This not only fuels parental concern, but also reinforces the message that social media and youth sexuality are a dangerous mix (Pascoe, 2011). As Goggin states (2010, p. 128), "societal concerns and anxieties over mobile media can quickly turn into panics". This panic-driven discourse can be seen as a symptom of a broader moral panic that has emerged in recent years regarding social media and youth sexuality. A moral panic is defined by Cohen (1972) as follows:

Societies appear to be subject, every now and then, to periods of moral panic. A condition, episode, person or group of persons emerges to become defined as a threat to societal values and interests; its nature is presented in a stylized and stereotypical fashion by the mass media; the moral barricades are manned by editors, bishops, politicians and other right-thinking people; socially accredited experts pronounce their diagnoses and solutions; ways of coping are evolved or (more often) resorted to; the condition then disappears, submerges or deteriorates and becomes more visible. (Cohen, 1972, p. 1)

Following this definition, we can state that there is a moral panic about the supposed threats of social media to the well-being of young people. Moreover, this moral panic has resulted in a media panic as the fear of social media is being channeled through mass media.

Hence, media themselves are the subject of the current moral panic, generating what Drotner (1992) describes as a 'media panic,' meaning that media are both the subject and the source of the debate (Krijnen & Van Bauwel, 2015; Lim, 2013). According to Critcher (2003), media panics rework the theme of the innocent corrupted by culture, in this case the corruption of childhood innocence by social media; and the panic in public debates about youth and social media is actually about broader societal anxieties, in this case the concerns that come along with technological innovations such as the internet (Buckingham & Jensen, 2012). However, technological innovations such as the internet are now integral elements of contemporary youth cultures, in which online and offline lives are intertwined. They play a crucial role in processes of identity development, including sexual communication and exploration (Pascoe, 2011).

Sexting: Deviant or Normal Youth Behavior?

Although sexual curiosity is a natural feature of adolescent sexual development, adults find it difficult to give meaning to new forms of sexual expression within contemporary youth cultures (Best & Bogle, 2014). Youth cultures in Western societies are especially characterized by increasing digitalization; new media technologies such as smartphones are now an essential part of a youth's everyday life. They provide access to social media platforms on which young people can be active and online at every moment of the day (Mediaraven & LINC, 2016). Popular applications, such as Facebook and Snapchat, offer young people new platforms for self-expression, including sexual self-representations. Sexual self-representations can thus be seen as performing (sexual) identity. Yet, the online visibility of youth's sexual expressions/negotiations leads to greater concerns about the 'sexualization' [2] of young people, especially that of young girls. Practices such as sexting, taking sexy selfies, and joining dating apps are being seen as threats to the healthy development of adolescents, who supposedly lack the required maturity to fully understand the consequences of the sexual content they are producing and consuming online. The risk of not being able to control what happens to personal data once it is uploaded only serves to fuel public concern about youth, sexuality, and social media (Dobson, 2015; Gabriel, 2014; Thiel-Stern, 2009).

Hence, young people's social media activities, especially those that are related to sexuality, have been widely discussed in public and academic discourses. One phenomenon has been covered extensively in the past few years. Sexting, which is "the interpersonal exchange of self-produced sexualized texts and above all images via cell phone or the internet" (Döring, 2014, p. 1), is considered to be a new, high-risk, and sexualized practice among youth (Best & Bogle, 2014; Lenhart, 2009; Ringrose, Harvey, Gill, & Livingstone, 2013). The rise of smartphones with mobile internet connections has made the production, distribution, and consumption of sexualized self-portraits easier than ever before. These self-portraits include sexually revealing pictures taken in swimwear or underwear, nude or semi-nude, and sometimes depicting sexual activities.

The public and many academic discourses concerning this sexting debate are mainly formulated within two theoretical frameworks that are used to analyze this youth phenomenon as it relates to sexuality: first is the deviance discourse, where the focus is on the risks of sexting; and second is the normalcy discourse, where the focus is on the opportunities it offers.

Deviance Discourse

According to Döring's (2014) conceptualization, the deviance discourse is the predominant theoretical framework used when considering the sexting phenomenonboth by society and academics. Hereby, sexting is framed as a new type of deviant sexualized behavior present in digital youth cultures that carries with it many risks (Ahern & Mechling, 2013; Draper, 2012; Hua, 2012). Risks such as the unwanted distribution and/or circulation of private sexts, (cyber)bullying by peers, exclusion from educational and future career opportunities, mental health problems, and criminal charges are among the most often cited. It is also remarkable that private sexts going viral are seen as an almost inevitable consequence of sexting (Mediaraven & LINC, 2016). Even if the sexts stay private, sexting remains linked to other forms of deviant sexual behavior, such as unsafe sex, promiscuity, sexual objectification, sexual violence, and sexual abuse by peers or adults (Fontenot & Fantasia, 2011; Hua, 2012; Jewell & Brown, 2013). Other prominent features of this deviance discourse are the attempts to explain this type of sexual behavior by referring to the 'thoughtlessness' of youth, peer pressure, and high-risk personality traits, and by emphasizing the need to better educate young people on the possible risks and consequences of sexting (Döring, 2014).

Normalcy Discourse

However, contradicting the discourse of 'deviance,' sexting is also framed as a 'normal contemporary form of sexual expression and intimate communication in romantic and sexual relationships' (Döring, 2014, p. 6). Interpreting sexting as a normal part of contemporary sexual development is an indicator of the growing normalcy discourse around youth and sexting. Within the heavily mediated lives of young people, intimate communication and sexual exploration take place via both online and offline channels. Sexting behavior can thus be understood as just another form of how young people express sexuality, facilitated by current new media technologies. Among the opportunities associated with youth sexting are sexual exploration and expression, bonding, trust, and learning to communicate and deal with sexual feelings (Hasinoff, 2013; Bond, 2011). Hence, normalcy discourse states that sexting is not consistently linked with risky behavior, unlike what deviance discourse suggests (Döring, 2014).

Gender, Agency, and Victimization

As previous studies have shown, discourses on youth sexting are gendered (Hasinoff, 2016; Ringrose, Harvey, Gill, & Livingstone, 2013; Albury, Crawford & Bryon, 2013), especially when it comes to young girls and sexuality, as they are generally portrayed as 'foolish' and 'innocent victims' (Attwood, 2011; Ringrose & Harvey, 2015; Thiel-Stern, 2009). The sexual self-representations ('sexy selfies') found on social media are mainly linked with 'self-sexualization' or 'self-objectification,' referring to a female who is "sexually objectifying herself by willingly presenting her body as a sexual object for others' use" (Hall, West, & McIntyre, 2012, p. 3). These discourses are changing the perception of the internet; while the internet has been understood as an empowering platform for gender and sexuality, the internet is now associated with 'risks' and being a 'sexualized digital environment' (Dobson, 2015). Discussions on (new) media are often characterized by both optimistic as pessimistic understandings (Storey, 2012), yet the debates surrounding youth sexting are specifically interpreting every sign of sexual expression by young girls as evidence of their vulnerability to (negative) sexualized media influence (Dobson, 2015). Moreover, protectionist and moralist discourses position young girls as vulnerable to potential harm, but at the same time blame-worthy for producing sexualized content (Best & Bogle, 2014; Thiel-Stern, 2009). However, it is important to be aware of the sexual double standards that exist, and to avoid gender stereotyping. As it cannot be the case that all girls are victims and all boys are sexually aggressive perpetrators, we need to examine the mediated discourses about young boys and their sexual identities as well (Döring, 2014; Thiel-Stern, 2009).

The panic over sexualization of youth through social media tends to ignore the agency of young people when it comes to their sexuality. By dividing them into binaries of either 'innocent' or 'sexualized,' these discourses fail to acknowledge the sexual development of young people (Dobson, 2015). Representing them as passive victims through the use of terms such as 'foolish,' 'shame,' and 'inappropriate,' these discourses frame youth as incapable of having any form of positive sexual agency (Angelides, 2013; Karaian, 2012). Femininity in particular is once again associated with a lack of power and control (Thiel-Stern, 2009). Yet, it is important to take agency into consideration when discussing/analyzing young people's social media use. According to Gabriel (2014), youth are self-aware when it comes to their self-representations on social media: they worry about their appearance, how others perceive them, explore their sexual and romantic interests, and try to fit in with their peers. This contradicts the image of youths as passive consumers and victims found in the deviance discourse spread via media.

Through this theoretical lens, we examine the following research question: "What are the media discourses on youth sexting in print media in North Belgium?" We analyze the media discourses on youth sexting published in the print media in Flanders (Northern Belgium) between 2009 and 2016. Deviance discourse and normalcy discourse will both serve as conceptual frames to better understand the binary logic of the media panic on youth sexting in Flanders. Hereby, we will pay specific attention to (1) gender issues, by examining both the femininity and masculinity discourses within the sexting debate; and (2) agency issues, by analyzing the representation of youths as passive victims.

Methodology

The qualitative research design underpinning the research presented here consists of a textual analysis of print media articles published in newspapers and magazines in Flanders about youth, sexuality, and social media. As Buckingham & Bragg (2004) explain, print media is of primary importance to understand how young people's digital media cultures are shaped and co-constructed by broader society. The current societal debates on the portrayal of youth, social media, and sexuality do not only occur in print media news stories, but are also based on it, which is making print media a decisive actor in the shaping and circulating of public discourses. We have opted for a textual analysis because of the narrative character of the data and its potential as (1) a site of ideological negotiation; and (2) a site in which current societal debates on representations of youth, digital media, and sexuality are played out (Fürsich, 2009). By conducting a textual analysis of newspaper coverage of youth sexting, we can focus on the latent meanings of the text, such as their underlying ideological and cultural assumptions, in order to make sense of youth sexuality and social media (Fürsich, 2009; McKee, 2003).

First, a search of Gopress [3], which is a large database of newspaper and magazine articles published in Belgium, was conducted. We analyzed both quality newspapers and magazines as well as the more popular ones (Hauttekeete & De Bens, 2005; De Vuyst, Vertoont & Van Bauwel, 2016) [i].This yielded 392 popular press articles in total, of which 232 were relevant because of the specific focus on youth. For the purpose of this paper, we took a sample of these articles that fell under the theme 'sexting and nude photos'. Our sample exists of 28 articles from Flemish newspapers and magazines published between 1 January 2009 and 31 December 2016. We chose this time span for two reasons. First, the social networking site Facebook became available in the Dutch language in 2008. After its release, the site hit a peak number of 200 million active users in April 2009. Since then, the popularity of the social networking site has increased, thus making it a relevant element of Flemish public discourse. Second, Snapchat was also released during this period (in 2011), reaching a peak amount of shared content in April 2015. We searched for articles published within this time span by using the following keywords: sexting, naked pictures, youth and sexuality, youth and social media. The articles in our sample are mainly drawing on the topics of sexting, sexuality and cyberbullying.

The selected articles were analyzed using textual analysis, mainly because of its flexibility and openness as a method (Dhaenens & Van Bauwel, 2017). First, we began with an initial reading of the articles. We looked at the discourses that were used in describing youth sexting, relating the articles to the deviance and normalcy discourses on sexting. Next, we deconstructed the texts by paying particular attention to the concepts of gender and agency; we analyzed the femininities and masculinities that were implicitly or explicitly outlined in the texts, and looked at the genders of the individuals who were framed as being responsible for this phenomenon. We also interpreted the language used in these articles by looking at the words used to describe youth sexting from a specific deviance or normalcy perspective. Through this methodological approach, we aimed to answer the following research question: What is the media discourse on youth sexting in print media articles published between 2009 and 2016 in Northern Belgium (Flanders)?

Findings

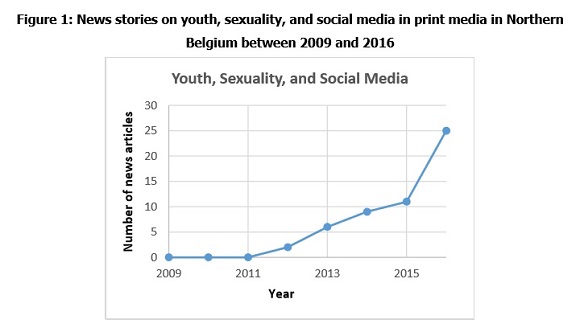

The digitization of young people's livestheir intimacies in particularis currently a site of public interest. As Figure 1 illustrates, there has been a gradual rise in the number of print media articles published covering youth, sexuality, and social media since 2011. In 2015, there was a sudden and sharp rise in the number of stories being published on the subject.

From 2015 onwards, 'sexting' was added to mainstream vocabulary in the Flemish region as a new word to describe young people sharing their self-produced sexual materials using digital media. Also in 2015, there was a rapid adoption of Snapchat among youth in Flanders, which allowed them to experiment with sharing picture-based, ephemeral content (Mediaraven & LINC, 2016), which received media attention. As such, news stories covering young people's sexualities in the context of digital media focused from that moment on 'sexting'. Generally speaking, those stories about sexting highlighted the potential risks and harm sexting might cause. They were usually evidenced by authoritative voices, such as academics and spokespersons for organizations and foundations promoting sexual health, education, and the prevention of sexual abuse.

Sexual Double Standards for Youth: Promiscuous Girls and Aggressive Boys

A review of the majority of the news stories in our database indicated the presence of a gendered discourse in the reporting on sexting as new phenomenon in the lives of young people. When discussing the online sexuality of young people, this mainly resulted in focusing on the sexting practices of young girls. This is in line with earlier studies carried out by scholars like Thiel-Stern (2009), Draper (2012), and Dobson (2015), showing that societal concerns about youth sexuality and social media mainly focus on girls. Our findings showed that this pattern extends to news articles discussing sexting as a general youth phenomenon, as the terms 'young people' and 'girls' are used interchangeably, often switching tacitly from one to the other. Youth is almost unconsciously being replaced by girls, which may lead to the perception that mostly girls engage in sexting. This gendered representation has not only created sexual double standards within youth sexting, but has also highlighted the risks that are associated with this practice, specifically for young girls. The risk of a private sext circulating on the internet is being illustrated as something that is almost inevitable and unavoidable, since "a lot of these sexy selfies are just being dropped on the internet" (HLN, 2015, 7 December, p. 11). This is mainly in line with the tendency of newspapers and magazines to use alarming words to describe sexting, but also to give a voice to those experts focusing on the potential risks of sexting.

By illustrating sexting as a practice in which young people are "guilty" of participating (Van Huffel, 2013, 4 January, p. 2), these stories frame sexting as a deviant practice that "often leads to big dramas when hot pictures are suddenly shared with the entire school or online" (B.H.L., 2016, 12 May, p. 19). This deviancy is usually linked to victimization. The dominant idea that "nudes are being misused most of the time" (Van Gestel, 2015, 15 December, p. 147), implies that the young people sending nudes are victims. This victimization is mainly targeted at young girls, by describing them as naïve victims "who don't even realize that they are presenting themselves as objects" (Van Huffel, 2013, 4 January, p. 2). Our analysis found that most of the articles on sexting indeed focused on the risks, thereby creating a gendered division by emphasizing the sexuality of young girls and referring to the 'thoughtlessness' of them as victims. In this sense, we can draw on the conceptualization of Döring (2014) and state that the deviance discourse is dominant in news stories on youth sexting.

However, there are also news stories challenging this deviance discourse by highlighting sexting as a practice that "is not necessarily problematic, as it is part of the sexual development of adolescents" (Vancaeneghem, 2016, 19 May, p. 5) and "belongs to the 'modern love game' nowadays" (Metro, 2014, 3 September, p. 7). These articles are indicators of the increasing normalcy discourse in which sexting is understood as just another form of sexual expression. Nevertheless, this 'normalization' of sexting still pays attention to its potential risks, such as the unwanted circulation of sexts: "Sexting is not at all stupid and dangerous. But it gets so when the receiver shares these pictures with others" (Van Wynsberghe, 2016, 22 September, p. 28).

It is also interesting that news stories covering sexting as a 'normal' practice still chose to take quotes from youngsters that presented young girls as victims:

A study of 14 to 18 year olds by the University of Antwerp states that young people are experimenting more and more with sexy pictures on social media, such as Instagram or Snapchat. "A girl in my class had sent a photo of her bra to her boyfriend at that moment. That picture was shared with others just like that." (Van Remoortere, 2016, 15 November, p. 5)

Hence, stories reporting on youth sexting were strongly gendered. Sexting was described as a practice that is specifically risky for young girls. Some articles interviewed investigative journalists who insinuated that young girls have a "secret life on social media" (Depecker, 2016, 6 December, p. 14), where they promote their sexual selves in an attempt to gain popularity or to please boys. These boys are so-called "fuckboys" who "treat girls without respect ( ) and focus on other victims " (Depecker, 2016, 6 December, p. 14). Interviews such as these show a very one-sided representation that is heavily gendered. First, girls are portrayed as the only victims, mostly due to their promiscuity and naivety. This leads to victim blaming, as articles refer to cases where "youth themselves think that the person who took the photograph in the first place is the one to blame when these nude pictures circulate" (Van Wynsberghe, 2016, 22 September, p. 28). Second, boys are portrayed as sexually aggressive and assertive, since they "pressure girls to send sexy pictures" (Van Huffel, 2013, 4 January, p. 2) and "sext faster than girls" (B.H.L., 2016, 12 May, p. 19). These news stories are often built upon quotes taken from young people themselves, such as quoting young boys who have compared sexting to "collecting Panini stickers" [4] (HLN, 2015, 7 December, p. 11), and young girls who have discussed their insecurities and how they have been "bullied by everyone" (Van Gestel, 2015, 15 December, p. 174) after their sexts have gone viral. Such stories again reinforce the deviance discourse on sexting while at the same time frame sexting as 'normal' among young people.

This gendered discourse can be understood as the projection of sexual double standards on youth sexuality. Depictions of young boys and girls mainly rely on stereotypical and heterosexual masculinities and femininities (Dobson, 2015; Albury, Crawford & Byron, 2013); the masculinity of boys consists of sexual aggressiveness, implying that teenage boys can be sexual predators, and presenting the femininity of young girls as that of naivety, implying that all girls can fall victim to sexual practices/predators. The focus on the risks of sexting implies a personal responsibility without clarifying the gendered and socially-constructed nature of such risks, leading to an intensifying of potential harms (Dobson, Rasmussen & Tyson, 2012). In this sense, we can state that these discourses frame sexting within a gendered deviance discourse by focusing on the risks and gender stereotyping the sexuality of young people.

Missing: Agency

When we look at news stories offering explanations for the sexting behavior of youth, we can see that one of the most recurring explanations is the concept of peer pressure. This implies that youngsters are getting pressured by their peers or feel a societal pressure for acting in a particular way to gain popularity, as the following quote suggests: "Friendship groups also play an important role. Girlfriends challenge each other to cross boundaries. [ ] The peer pressure is so high that teenagers are shutting down their own sound judgments" (Van Huffel, 2013, 4 January, p. 2). Döring (2014) stated that peer pressure is a common feature of the deviance discourse. It is used in an attempt to explain the incomprehensibly deviant behavior of 'innocent' young people. Peer pressure is often presented as a gendered burden that is mostly carried by young girls. The assumption that girls engage in sexting because of their peers tends to deny the capacity of girls to act individually. By focusing on acting under pressure, the femininity of young girls is associated with a lack of power and control (Thiel-Stern, 2009). Moreover, young girls are framed as incapable of any form of sexual agency (Angelides, 2013), as they "don't realize that those selfies can circulate very quickly over the internet" (Van Gestel, 2015, 15 December, p. 174). As the following excerpt shows, these discourses assume that young girls are not aware of the consequences of sexting:

Parents of teenage girls are very worried today. They discovered that a (male) classmate shared nudes of pupils with others. He most likely received these pictures from the girls themselves, which is not a smart thing to do. But, we can assume that neither the offender nor the victims were aware of the consequences. The brains of adolescents lead to more impulsive behavior. (B.C.L., J.A.B. & R.D.K, 2016, 20 September, p. 10)

Although there were examples of news stories within the normalcy frame that acknowledged the sexual development of young people and described sexting as a form of "sexual exploration" (Alsteens, 2016, 12 May, p. 6), the concept of peer pressure also emerged in these discourses.

Articles attempting to explain sexting as a normal experimental phase also feature research outcomes that state that "most of the time girls are the ones being pressured for a picture" (Alsteens, 2016, 12 May, p. 6). News stories encouraging parents to talk to their adolescents and increase their resilience to sexting, advised parents to ask their adolescents why they engaged in sexting: "Do they want attention? Do they need confirmation?" (HLN, 2015, 7 December, p. 11). These questions can be confusing for both parents and youth as they implicitly suggest that sexting is an irrational practice. Another recurrent piece of advice was to send pictures that could not be connected to them individually when sexting with peers or loved ones such as nude pictures without the sender's face, or to "not pose in front of a camera in a way you wouldn't dare in public" (Klifman, 2015, 12 September, p. 15). This implies that there is a constant risk of pictures being circulated, thus underlining the belief that sexting is not a safe practice. Since the normalcy discourse aims to frame sexting as typical sexual behavior, these discourses can be seen as contradictory as they might imply that sexting is actually an unusual sexual practice.

Hence, our findings have shown that these discourses may assume that young people lack agency. First, the focus on peer pressure in news stories on sextingwithin both deviance and normalcy discoursescan be seen as disregarding the capacity of young people to act autonomously. Second, the advice given to parents to make their adolescents 'resilient' might be understood as a call to protect (passive) youngsters against their own 'thoughtlessness,' again neglecting to recognize their ability to independently act and evaluate within certain circumstances.

Criminalization of Sexting

As already stated, the deviance discourse-based news articles mainly focused on the potential risks of sexting. One of the most common risks presented was the possibility of facing criminal charges (Döring, 2014; Albury, Crawford & Byron, 2013). In our analysis, we found that news articles framing sexting as a deviant practice were mainly based on criminalization and victimization. Victims were portrayed as suffering from emotional harm, because "being exposed on the internet can have far-reaching consequences. Youngsters isolate themselves, become anxious, depressive, and in some cases even suicidal" (Van Gestel, 2015, 15 December, p. 174). The unwanted circulation of sexts can be "traumatic" (M.K.M., 2015, 12 September, p. 17) for young people. Most of the time, print media has chosen to quote young girls who have been victims of sexting, insinuating once again that girls are passive victims without agency, as the following quote suggests:

My breasts were not meant to be seen by everyone, but suddenly they were public property. [ ] And that makes you insecure. Because you want to take back control over your own body, but that is impossible after the picture goes viral. (B.D.C., 2016, 9 February, p. 42)

However, these news stories rarely paid attention to the victimization of boys. Young boys were almost systematically portrayed as sexually aggressive offenders who were "distributing massive amounts of nude pictures of female classmates" (Het Nieuwsblad, 2016, 20 September, p. 1). The assumption that sexting turns young boys into criminal offenders was strengthened by quotes taken from experts that referred to sexting as a "crime" (M.K.M., 2015, 12 September, p. 17), or as a form of "child pornography" (B.C.L., J.A.B. & R.D.K., 2016, 20 September, p. 10), and that insinuated that "smartphones are weapons" (Neyt, 2014, 6 August, p. 6). This reinforced the tonality that sexting is a deviant and dangerous practice. The discourses that emphasized the criminality of sexting created a sense of authority by quoting statistics, such as "88% of the nudes of young girls and boys are put on the internet" (HLN, 2015, 7 December, p. 11). Reports and campaigns on youth sexting stated that "this phenomenon is disturbing" (M.K.M., 2015, 12 September, p. 17).

Our analysis explored the binary in media representations on youth sexting. First, young people are divided into the roles of victim or offender. Second, this binary is strongly linked to gender stereotypes. Victims are mostly young girls who are passive and thoughtless and offenders are mostly young boys who are sexually aggressive and criminal. The strong emphasis on the criminalization of sexting as a practice and the victimization of young people reflects the deviant tonality within these discourses.

Conclusion

In recent years, the social media use of young people has become a site of increasing public interest. Youth experimenting with and experiencing sexuality and sexual identities in digital media spaces has evoked public debates on youth, sexuality, and social media. Sexting, in particular, has often been covered in newspapers and magazines. Although the social media use of youths has been studied in previous research, there remains a need to understand the broader cultural discourses on youth, sexuality, and social media (De Ridder, 2017). In this paper, we examined the dominant discourses on sexting in print media. To do so, we used Döring's (2014) conceptual framework, which states that there is a distinction between the deviance and normalcy discourses in covering sexting as a phenomenon. We conducted a textual analysis of 28 articles published in newspapers and magazines in Flanders (Northern Belgium) between 1 January 2009 and 31 December 2016, and we paid specific attention to gender and agency in our analysis.

In line with Döring's (2014) work, the findings of this study revealed that the deviance discourse is predominantly present in the public debate. Sexting as a phenomenon is perceived as a deviant behavior that brings with it several risks, such as the unwanted distribution and/or circulation of private sexts, (cyber)bullying by peers, and criminal charges. Our data indicated that there were also news stories challenging the dominant deviance discourse by covering sexting as a normal part of adolescent sexual development. These stories pointed to the growing normalcy discourse used when discussing youth sexting. Yet, in some cases these stories could be confusing in the sense that sexting, despite being presented as a normal sexual practice, was still emphasized as being a risky practice. The advice given to youngsters to send pictures that do not identify them, and the recommendation for parents to talk with their adolescents and try to find out the reasons for why they are engaging in sexting, insinuates that sexting is still assumed to be an 'unusual' sexual practice.

Following previous research, we analyzed how the current discourse on sexting is gendered (Attwood, 2011; Hasinoff, 2013; Thiel-Stern, 2009). Our study of news articles discussing sexting as a youth phenomenon found that these almost tend to switch unconsciously between 'youths' and 'young girls,' thereby emphasizing girls' sexual activities. This emphasis mainly results in a gendered binary in which girls are presented as 'thoughtless victims' and boys as 'sexually aggressive predators.' This leads to a very one-sided discourse in which young girls, due to their 'naivety,' are depicted as the only victims of sexting. Our analysis focused on this victimization of girls by mass media particularly because of its link to peer pressure in youth cultures (Döring, 2014). Assuming that youngsters engage in sexting only because of peer pressure denies the sexual development of young people and insinuates that they are incapable of having any form of sexual agency (Angelides, 2013). The femininity of young girls is especially, and again, associated with a lack of power and control (Thiel-Stern, 2009). This study also showed that along with the victimization of girls went the criminalization of boys. In the articles studied, young boys were depicted as sexually assertive and unreliable, pressuring girls to engage in sexting. Through the use of alarming terms such as 'child pornography,' 'crime,' and 'offender,' this discourse reinforced the message that sexting is a deviant practice, turning young boys into criminal convicts and young girls into passive victims. Hence, this binary discourse in describing sexting reinforces sexual double standards.

This paper has presented views on youth, sexuality and social media that may have implications for current and future research. First, we argue for a rethinking of the victimization and criminalization of youths, especially because of the tenuous link to their presumed lack of agency. Attwood (2011, p. 211) defined agency as "the self-reflexive adoption of a specific discourse," meaning that individuals who draw on the available hegemonic social discourses are still able to act as autonomous subjects. Since we can assume that peer pressure affects both boys and girls, we can think of their actions as individual anticipations of the hegemonic discourse on sexuality. Young girls engaging in sexting are not necessarily unconscious victims of either social media or their peers, but can be seen as active participants anticipating the hegemonic norms of femininity (Attwood, 2011). When we look at sexting, it may be a way for girls to create and perform their sexual identity (Ringrose, 2011). Therefore, instead of labeling young girls as passive victims, we should focus on empowering them by minimizing the stigma surrounding sexting and raising awareness of the opportunities social media might present in terms of their sexual development. Second, instead of criminalizing young boys for being sexually demanding, we should question the common masculine ideals that are patriarchal and heterosexist in society. As the study of Albury, Crawford & Byron (2013) suggests, the mediated circulation of sexual images is not unique to young people. For instance, the publication of celebrity pictures taken by paparazzi implies that adult culture also approves sexual shaming and the non-consensual circulation of sexual images. The supposed pressure for boys to build a collection of nudes in order to gain popularity, with or without the nude parties' consent, may be leading to sexually assertive behavior. In this sense, we can see both boys and girls as active agents in negotiating their sexual identities while securing their place within their peer groups.

Furthermore, the print media discourses pay little attention to consensual sexting. As the news articles examined in this study mainly focused on the risky side of sexting, such as succumbing to peer pressure and the circulation of private sexts, they ignored the fact that sexting can also be consensual (Döring, 2014). This deviant discourse adds to the generally intolerant attitude towards sexual self-representation of youth through social media, thereby leading to further stigmatizing youth sexting and overlooking the importance of consent (De Ridder, 2017). Moreover, by denying the agency of young people to consent to sexting, these discourses paid no attention to the diversity within youth cultures. In this sense, we can speak of a symbolic annihilation (Tuchman, 1979) in this discourse on youth sexting. The representation of young people is mainly heteronormative and white, leaving no space to discuss the sexual experiences of LGBTQ youth or ethnic-cultural minorities. Assuming that all young people are at risk and share the same experiences not only denies their unique identities, but also overlooks the importance of intersectionality within the identity politics of young people. This study has shown how public discourses in newspapers and magazines in Flanders have mainly articulated youth sexting as a deviant behavior. This discourse is not only stereotypical and gendered, but also leaves little room to engage in a more diverse and active comprehension of this phenomenon.

References

Ahern, N., & Mechling, B. (2013). Sexting: Serious problems for youth. Journal of Psychosocial Nursing and Mental Health Services, 51(7), 22-30. [ Links ]

Albury, K., Crawford, K. & Byron, P. (2013). Young people and sexting in Australia: ethics, representation and the law. Australia: ARC Centre for Creative Industries and Innovation/ Journalism and Media Research Centre. Australia: The University of New South Wales. [ Links ]

Alsteens, L. (2016, May 12). "A Selfie With A Bare Chest." [Een selfie met bloot bovenlijf]. De Standaard, p. 6. [ Links ]

Angelides, S. (2013). Technology, hormones, and stupidity: The affective politics of teenage sexting. Sexualities, 16 (5/6), 665-689. [ Links ]

Attwood, F. (2011). Through the looking glass? Sexual agency and subjectification online. In R. Gill & C. Scharff (Eds.), New femininities. Postfeminism, neoliberalism and subjectivity (pp. 203-214). New York: Palgrave Macmillan. [ Links ]

Bauermeister, J. A. (2013). Significant and non-significant associations between technology use and sexual risk: A need for more empirical attention: The author replies. Journal of Adolescent Health, 53, 148-149. [ Links ]

B. C. L., J. A. B., & R. D. K. (2016, September 20). "Being Angry Will Not Help Now."[Kwaad zijn, dat helpt nu écht niet]. Het Laatste Nieuws, p. 10. [ Links ]

B. D. C. (2016, February 9). "I Was Ashamed of My Body, Even Though It Was Very Beautiful." [Ik schaamde me voor mijn lichaam, terwijl het net heel mooi is.] Humo, p. 42. [ Links ]

Best, J., & Bogle, K. A. (2014). Kids gone wild. From rainbow parties to sexting, understanding the hype over teen sex. New York: New York University Press [ Links ]

B. H. L. (2016, May 12). "A Quarter of Flemish Youngsters Receives Sexy Pictures." [Kwart Vlaamse jongeren krijgt pikante foto's.] De Morgen, p. 19. [ Links ]

Bond, E. (2011). The mobile phone = bike shed? Children, sex and mobile phones. New Media & Society, 13(4), 587. [ Links ]

Buckingham, D. &, Jensen, H. S. (2012). Beyond 'media panics': Reconceptualising public debates about children and media. Journal of Children and Media, 6(4), 413-429. [ Links ]

Cedillo, M. J., & Ocampo, R. (2016). Levels of self-monitoring, self-expression and selfie behavior among selected Filipino youth. The Bedan Journal of Psychology, 1, 45-52. [ Links ]

Cohen, S. (1972). Folk devils and moral panics. London: MacGibbon and Kee. [ Links ]

Critcher, C. (2003). Moral panics and the media. Buckingham: Open University Press. [ Links ]

Debruyne, H. (2012, October 3). "Who Does Not Dare, Is A Pussy." [Wie niet durft, is een watje.] Knack, p. 64. [ Links ]

De Ridder, S. (2017, July). Sexting as sexual stigma: The paradox of sexual self-representation in digital youth cultures. [ Links ] Paper presented at the International Association for Media and Communication Research annual conference, Leicester.

De Ridder, S. (2017). Social media and young people's sexualities: Values, norms and battleground. Social Media + Society, 3(4), 1-11. [ Links ]

De Ridder, S., & Van Bauwel, S. (2013). Commenting on pictures: Teens negotiating gender and sexualities on social networking sites. Sexualities, 16(5/6), 565-586. [ Links ]

De Vuyst, S., Vertoont, S. & Van Bauwel, S. 2016. "Sekse-ongelijkheid In Vlaams Nieuws. Een Kwantitatieve Inhoudsanalyse Naar De Aanwezigheid En Hoedanigheid Van Vrouwen En Mannen In Vlaamse Nieuwsverhalen." Tijdschrift Voor Communicatiewetenschap, 44 (3): 253-271. [ Links ]

Depecker, K. (2016, December 6). "The Secret Life of Teenager Girls on Social Media: Cool Picture! Wanna Have Sex?" [Het geheime leven van tienermeisjes op sociale media: 'Coole foto! Zin in seks?'] Humo, p. 14. [ Links ]

Dhaenens, F., & Van Bauwel, S. (2017). On conducting textual analysis in media and cultural studies. Unpublished paper, Ghent University, [ Links ] Department of Communication Sciences.

Dobson, A. S. (2015). Postfeminist digital cultures. Femininity, social media, and self-representation. New York: Palgrave Macmillan. [ Links ]

Dobson, A. S., Rasmussen, M. L. & Tyson, D. (2012). Submission to the Victorian law reform committee inquiry into sexting. Law Reform Committee, Parliament of Victoria, viewed, 12. [ Links ]

Don't Send Nude Pictures of Yourself. [Stuur geen naaktfoto's van jezelf door.] (2015, September 12). De Standaard, p. 17. Retrieved from http://destandaard.be.

Döring, N. (2014). Consensual sexting among adolescents: Risk prevention through abstinence education or safer sexting? Cyberpsychology: Journal of Psychological Research on Cyberspace, 8(1). Retrieved from: https://cyberpsychology.eu/article/view/4303/3352 [ Links ]

Draper, N. R. A. (2012). Is your teen at risk? Discourses of adolescent sexting in United States television news. Journal of Children and Media, 6(2), 221-236. [ Links ]

Drotner, K. (1992). Modernity and media panics. In M. Skovmand & K. C. Schroder (Eds.), Media cultures: Reappraising transnational media (pp. 42-62). New York: Routledge. [ Links ]

Etgar, S., & Amichai-Hamburger, Y. (2017). Not all selfies took alike: Distinct selfie motivations are related to different personality characteristics. Frontiers in Psychology, 8, 1-10. [ Links ]

Explained: How to Protect Your Pictures of Hackers. [Uitgelegd: Hoe bescherm je je foto's tegen hackers.] (2014, September 3). Metro, p. 7. Retrieved from http://metro.be.

Fontenot, H. B., & Fantasia, H. C. (2011). Issues and influences on sexual violence within the adolescent population. Journal of Obstetric, Gynecologic, & Neonatal Nursing, 40(2), 215-216. [ Links ]

Francien, Show Us Your Boobs Again. [Francien, laat je tieten nog eens zien] (2016, February 4). Het Laatste Nieuws, p. 9. Retrieved from http://hln.be.

Fürsich, E. (2009). In defense of textual analysis: Restoring a challenged method for journalism and media studies. Journalism Studies, 10(2), 238-252. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616700802374050 [ Links ]

Gabriel, F. (2014). Sexting, selfies and self-harm: Young people, social media and the performance of self-development. Media International Australia, 151(1), 104-112. [ Links ]

Gilbert, J. (2007). Risking a relation: Sex education and adolescent development. Sex Education, 7(1), 47-61. [ Links ]

Gill, R. (2007). Postfeminist media culture. Elements of a sensibility. European Journal of Cultural Studies, 10(2), 147-166. [ Links ]

Goggin, G. (2010). Official and unofficial mobile media in Australia: youth, panics, innovation. In Donald, S., Anderson, T. D. & Spry, D. (Eds.), Youth, Society, and Mobile Media in Asia (pp. 120-134). London: Routledge. [ Links ]

Hall, P. C., West, J. H., & McIntyre, E. (2011). Female self-sexualization in MySpace.com personal profile photographs. Sexuality & Culture, 16(1), 1-16. [ Links ]

Hasinoff, A. A. (2016). How to have great sext: Consent advice in online sexting tips. Communication and Critical/Cultural Studies, 13(1), 58-74. [ Links ]

Hasinoff, A. A. (2013). Sexting as media production: Rethinking social media and sexuality. New Media & Society, 15(4), 449-465. [ Links ]

Hauttekeete, L. & De Bens, E. 2005. "De Tabloidisering Van Kranten: Mythe Of Feit? De Ontwikkeling Van Een Meetinstrument En Een Onderzoek Naar De Tabloidisering Van Vlaamse Kranten." Gent: Ghent University. [ Links ]

Hua, L. (2012). Technology and sexual risky behavior in adolescents. Adolescent Psychiatry, 2(3), 221-228. [ Links ]

Jewell, J., & Brown, C. (2013). Sexting, catcall, and butt slaps: How gender stereotypes and perceived group norms predict sexualized behavior. Sex Roles, 69(11/12), 594-604. [ Links ]

Karaian, L. (2012). Lolita speaks: 'Sexting teenage girls and the law. Crime, Media, Culture, 8(1), 57-73. [ Links ]

Klifman, M. (2015, September 12). "Child Focus: Do Not Send Nude Pictures Of Yourself." [Child focus: 'Stuur geen naaktfoto's van jezelf door.'] Het Nieuwsblad, p. 15. [ Links ]

Krijnen, T., & Van Bauwel, S. (2015). Gender and media. Representing, producing, consuming. New York: Routledge. [ Links ]

Lenhart, A. (2009). Teens and sexting. Pew Internet & American Life Project, 1, 1-26. [ Links ]

Levine, D. (2013). Sexting: A terrifying health risk or the new normal for young adults? Journal of Adolescent Health, 52(3), 257-258. [ Links ]

Lim, S. S. (2013). On mobile communication and youth "deviance": Beyond moral, media and mobile panics. Mobile Media & Communication, 1(1), 96-101. [ Links ]

Livingstone, S., Mascheroni, G., & Staksrud, E. (2015). Developing a framework for researching children's online risks and opportunities in Europe. London: EU Kids Online. [ Links ]

McKee, A. (2003). Textual analysis: A beginner's guide. London: Sage. [ Links ]

Mediaraven & LINC (2016). Onderzoeksrapport Apestaartjaren 6. Ghent: Mediaraven. [ Links ]

Naezer, M. (2017). From risky behavior to sexy adventures: Reconceptualising young people's online sexual activities. Culture, Health & Sexuality, 20(6), 1-15. [ Links ]

Neyt, G. (2014, August 6). "Teenagers Don't Shower Naked Anymore Out of Fear for the Smartphone." [Tieners niet meer bloot onder douche uit vrees voor smartphone.] Het Nieuwsblad, p. 6. [ Links ]

Osgerby, B. (2004). Youth media. London: Routledge. [ Links ]

Pascoe, C. J. (2011). Resource and risk: Youth sexuality and new media use. Sexuality Research and Social Policy, 8(1), 5-17. [ Links ]

Ringrose, J. (2011). Are you sexy, flirty, or a slut? Exploring 'sexualization' and how teen girls perform/negotiate digital sexual identity on social networking sites. In R. Gill & C. Scharff (Eds.), New femininities. Postfeminism, neoliberalism and subjectivity (pp. 99-116). New York: Palgrave Macmillan. [ Links ]

Ringrose, J., & Harvey, L. (2015). Boobs, back-off, six packs and bits: Mediated body parts, gendered reward, and sexual shame in teens' sexting images. Journal of Media & Cultural Studies 29(2), 205-217. [ Links ]

Ringrose, J., Harvey, L., Gill, R., & Livingstone, S. (2013). Teen girls, sexual double standards and "sexting." Gendered value in digital exchange. Feminist Theory, 14(3), 305-323. [ Links ]

Storey, J. (2012). Cultural Theory and Popular culture: An Introduction. London: Routledge. [ Links ]

Thiel-Stern, S. (2009). Femininity out of control on the Internet. A critical analysis of media representations of gender, youth, and MySpace.com in international news discourses. Girlhood Studies, 2(1), 20-39. [ Links ]

Thiel-Stern, S. (2007). Instant identity: Adolescent girls and the world of instant messaging. New York: Peter Lang. [ Links ]

Teenager Massively Distributing Naked Pictures of Students. [Tiener verspreidt massaal naaktfoto's van medeleerlingen.] (2016, September 20). Het Nieuwsblad, p. 1. Retrieved from http://nieuwsblad.be.

Vancaeneghem, J. (2016, May 19). "Even Sexting in Primary School." [Zelfs in lagere school al sexting.] Het Nieuwsblad, p. 5. [ Links ]

Van Gestel, G. (2015, December 15). "Suddenly My Boobs Appeared on Facebook." [Plots stonden mijn blote borsten op Facebook.] Dag Allemaal, p. 147. [ Links ]

Van Huffel, E. (2013, January 4). "New Trend: Sexy Picture as Proof of Sexiness." [Nieuwe trend: Sexy foto als bewijs van vrouwelijkheid.] Het Laatste Nieuws, p. 2. [ Links ]

Van Remoortere, R. (2016, November 15). "1 out of 5 Youngsters is Posting Sexy Pictures Online." [1 op de 5 jongeren zet pikante foto's online.] Gazet van Antwerpen, p. 5. [ Links ]

Van Wynsberghe, H. (2016, September 22). "Make Sexting a Discussable Topic Within the Family." [Maak sexting bespreekbaar in het gezin.] Gazet van Antwerpen, p. 28. [ Links ]

1 out of 4 Youngsters is Sending Nude Pictures to Others. [1 op 4 jongeren stuurt naaktfoto's van zichzelf door (2015, December 7).] Het Laatste Nieuws, p. 11. Retrieved from http://hln.be.

Submitted: 14th December 2017

Accepted: 12th February 2019

Note

[1] Authors' own translation. In this paper, all direct quotations taken from our data have been translated by the authors into English.

[2] Sexualization refers to a societal trend that tends to connect everything, from clothing and music to driving a car and eating dinner, with sex and sexuality (Krijnen & Van Bauwel, 2015, p. 159).

[3] Gopress is the online database and press monitoring service for all Belgian newspapers and magazines. Gopress is enabled by the Belgian publishers Mediahuis, Editions de l'Avenir, IPM, Mediafin, De Persgroep Publishing, Rossel and Roularta Media Group.

[4] Panini stickers are collectible stickers of famous football/soccer players.

[i] Our database consists of print media articles written and published in Northern Belgium. We analyzed both quality newspapers and magazines as the ones considered to be more popular/tabloid. The quality newspapers (N=3) are: De Morgen, De Standaard and De Tijd. We also explored the articles in Knack, which is acknowledged as a quality magazine (N=1). Furthermore, we studied the more popular and regional newspapers (N=6) such as: Gazet van Antwerpen, Het Belang van Limburg, Het Nieuwsblad, Het Laatste Nieuws, Krant Van Vlaanderen and Metro. In addition to the newspapers, we also examined the popular magazines (N=8) as Dag Allemaal, Flair, Goed Gevoel, Humo, Joepie, Libelle, Trends and TV Familie. Finally, we analyzed articles published by Belga, which is the Belgian news agency (N=1).