Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Acessos

Acessos

Links relacionados

-

Similares em

SciELO

Similares em

SciELO

Compartilhar

Observatorio (OBS*)

versão On-line ISSN 1646-5954

OBS* vol.12 no.spe1 Lisboa set. 2018

Channels produced by LGBT+ YouTubers: gender discourse analysis

Marian Blanco-Ruiz*, Clara Sainz-de-Baranda**

*Rey Juan Carlos University, Spain

**Carlos III of Madrid University, Spain

ABSTRACT

YouTubers are idols, and influence millions of people who follow their channels every day. These new media stars, born in transmedia, create their own content outside the major corporations. Across the millions of YouTube channels, Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transsexual, Intersexual and Queer (LGBTIQ or LGBT+) YouTubers are gaining more young followers who identify with their content and, also, are able to have direct contact with these YouTube “stars”. The objective of this research is to explore and analyse the content of the YouTube channels of the most popular LGBT+ YouTubers among Spanish young people and to assess whether there are gender biases in their content. The results show that content created by these YouTubers is more diverse than mainstream channels, with content ranging from personal stories to bullying. In spite of this, these channels continue to reproduce some gender stereotypes.

Keywords: LGBT+, social media, YouTube, gender identity, gender stereotypes

Introduction

The transmedia paradigm places us, in communicative matters, in a digital, global, interactive, participative, viral and open space, where any person-user can become in turn a content generator (Carrera et al., 2013). This directly results in, for the first time in history, common people becoming communicators with great influence, gatekeepers or non-official agents who determine the message flow to their community (Scolari, 2013; Jenkins et al., 2015) thanks to their use of YouTube platform and their social networks.

Those bridges have been culturally appropriated by users and have shaped the way in which media participate within our lives (Jenkins, 2006; Livingstone, 1999). Additionally, the rise of digital and multimedia technologies enables the so-called traditional media (press, radio and television) to become more multifunctional, integrating functions such as information, communication, transaction, entertainment, sociability, education and identity building (van Dijk, 2006).

Media is one of the socializing agents that serves to transmit sociocultural learning, and hence it has a key role in identity construction, especially through the transmission of gender stereotypes. Identity construction constitutes one of the main challenges of adolescence (Zacarés et al., 2009), where media helps teenagers shape a coherent conception of themselves, including the formation of a satisfactory gender and sexual identity (Erikson, 1971). Constant exposure to the flood of cultural prompts through the media allows unnoticed assimilation of a series of codes and sub-codes within a universe of signs that transmit a previously established ideology that contributes to legitimizing some identity models over other ones. Carrera (2017) warns that the Internet’s ideological power as mass media has not vanished with the emergence of the prosumer

“beyond the obvious demagogy on this representation of the Internet as tabula rasa, where power relationships in favour of a global communicative democracy would have been diluted, but what is true is that Internet users experiment closeness and a sense of control over the medium that they do not feel when they watch a TV program or when they go to the cinema. As Internet, the first mass medium also used to manage intimacy and private affairs, has been increasingly merging media experiences with the intimate and experiential territory” (Carrera, 2017, p.38).

Therefore, it is important to explore from a gender point of view what discourses are being spread on the Internet, and, more specifically, on YouTube channels, because, as Zafra (2011) states, patriarchal power relationships are inherently inserted in digital culture and on the ‘occupation’ of those digital spaces.

“Let’s think who makes what on the Net and how she or he gets benefits from that work; who the prosumers who feed their digital ‘I’s’ on social nets are (maybe we should mainly say: female prosumers) and who the ones who capitalizes those sites (YouTube, Facebook, Google or Tuenti, among others) are. Let’s see that the creators of these tools match, in this case, with a distinctive profile of this technological era: young boys who used their computer – and in many cases, their garages – as the centre of a technological company. However, the value of these companies in each case is not the device itself, but to conceive it as ‘spaces’ who gather millions of ‘I’s’, spaces that become as a part itself of affective relationships and that turn users into producers and into contents. These relation structures certainly talk about ways of distribution of people and spaces that are not exempt of political significance” (Zafra, 2011, p.121).

Therefore, even though the Internet has become a reference medium for interpersonal communication, economy, education or entertainment, it is not disjoint from ideological components and the logic of power. “There is nothing natural or inevitable about the practices, discourse, and behaviour emerged on the Internet. To the contrary, the Internet is quintessentially unnatural; that is, it has certainly not arisen organically out of state of nature” (Mantilla, 2015, p.189).

YouTuber phenomenon

According to Watkins (2009), the Internet is, after the hegemonic position of television over the decades, a reference source for leisure, information and entertainment at home, as social networks and shared video platforms are the most frequented places by teenagers in Spain (García et al., 2013).

The platform has changed the way of consuming audiovisual content, but it has also redefined the audiovisual business model, with a fragmentation of audiences and an upward trending presence of minors as authorized issuers through their YouTube channels, accompanied by a great presence of trademarks (advertent or inadvertent) and the consequent blurring of advertising intent (Burgess, 2012; Tur-Viñes et al., 2018).

However, the prevailing discourse is still determined by major media and institutional corporations, attracting to their business the emerging YouTube stars and the group of users related to them. Through this participative and co-creative drill, institutional issuers increase their knowledge about audiences – in this case about youths – and maintain control of the agenda (Carrera, 2016). Even though not all the teenage surfers become prosumers with their own video channel, watching video is one of the most prevalent habits in the media diet of teenagers (Holloway et al., 2013). According to Ramos-Serrano et al. (2016), in YouTube there is a difference between “standard YouTubers”, who are the ones who create and share their videos with their immediate environment; and the “special YouTubers” who interact with their online followers’ community, who have subscribers and who offer recommendations and/or suggestions. This last group encompasses the YouTuber phenomenon, YouTube channels with thousands of subscribers who have turned the young producers into media stars born from transmedia storytelling outside major channels of media conglomerates, who succeed in creating their own content, setting their own agenda together with their followers with whom they establish direct communication. According to Jenkins et al. (2015, p.116), they manage to create “successful careers for themselves by actively responding to other users they see and comment, inviting them explicitly to subscribe and to answer”. It is precisely this direct contact on which the success of YouTubers is based.

“this type of contact generates, on one side, an individual who assumes the video production, and at the same time, an active viewer who leaves his sign on the interface and actively takes part by commenting, expressing his likes and dislikes, subscribing to the channel and making contact with the YouTuber through other media, such as Twitter” (Scolari & Fraticelli, 2017, p.16).

They are becoming the new personal cults that make that thousands of people identify themselves with the charm of the YouTuber’s personality (Cocker & Cronin, 2017). This YouTuber personal charisma is what Dare-Edwards (2014) or Tolson (2010) consider key for surviving on the net.

YouTubers are perceived by teenagers as their equals (Pérez-Torres et al., 2018), which enables identification with them (Westenberg, 2016). YouTubers as well as their subscribers’ communities mostly belong to the Net Generation (Tapscott, 1998), a generation that not only uses the Internet for communicating, but also for self-realizing and forging their own identity (Feixa, 2000).

Gender identity and YouTube

Open sites on the Internet and social networks, such as Instagram or YouTube, have become one of the most relevant contexts for teenage identity construction thanks to the fact that they allow the possibility to interlink and to establish relationships with their equals (Barker, 2009; Pérez-Torres et al., 2018).

It is demonstrated that mass media are a very important tool when it comes to developing a gender identity (Hill, 2005). In media content, generated by users or also by media groups, different roles are still assigned depending on gender, which contributes to gender socialization and to affirming false beliefs about gender inequality. The analysis from the gender point of view of media stories as popular as The Simpsons (Grandío, 2008), the Disney universe (Aguado et al., 2015; Guarinos, 2011), Friends (Grandío, 2009) or The Diary of Bridget Jones (Gill, 2007; 2009) has shown the relevance media have on the construction of sexual and gender identity. Furthermore, Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transsexual, Intersexual and Queer (LGBTIQ or LGBT+) characters are underrepresented and stereotyped in mass media (Pullen & Cooper, 2010; Ramírez & Cobo Durán, 2013).

Teenage identity formation is a negotiating process where approaching and distant dialectics are produced with the models shown in the media (Pindado, 2011), which is why it is important to analyse how much they contribute to gender socialization and to affirming false beliefs about gender inequality.

YouTube is still a highly masculinized space (Maloney et al., 2017). Male producers predominate on YouTube. For example, in Spain, out of the 30 YouTube channels with the highest number of subscribers, there is only one produced by a woman. Apart from the glass ceiling, traditional gender roles are perpetuated in user-generated content, as the majority of men focus on toilet humour and gaming, while women seem to be obsessed with make-up tutorials and knowing ‘what to wear’ (Rey & Romero-Rodríguez, 2016; Scolari & Fraticelli, 2017; Blanco-Ruiz, 2017).

However, there is a growing number of LGBT+ YouTubers emerging to offset the flow of male, chauvinistic and misogynistic accounts (Caballero-Gálvez et al., 2017). This freedom of content creation by LGBT+ YouTubers has enabled the creation of a space for cultural production (Fink & Millet, 2013) that the traditional media (press, radio and television) agenda does not offer. In his analysis about transgender vlogs, Raun (2012, p.165) found that the camera serves as an external interlocutor, “a companion you can trust and tell everything”.

Among these LGBT+ YouTubers, Pérez-Torres et al. (2018) identifies two types of identity treatment: gender identity together with sexual identity, and vocational identity. In this research, we want to focus on the former, as in the LGBT+ YouTuber videos one can observe how they explain the process they have followed (and still follow) on the construction of their gender and sexual identity, explaining to their audiences what their reasons were to decide between one orientation or the other, what gender they identify with, how and when it happened, what the problems were and the doubts they had, how they were supported or not by their environment and family, etc. Ultimately, these YouTubers transmit their emotional experiences about their processes of gender and sexual identity construction, as their videos related to sexual orientation are the most viewed ones (Pérez-Torres et al., 2018).

If we were to compare LGBT+ YouTubers’ content with the representation of this group on the traditional media, we can see that these channels offer the possibility to the least represented groups – such as LGBT+ collectively – to develop new bonds of global citizenship, empowerment and voice on formal and informal education. YouTube starts being used as an informal space for education, where LGBT+ youths can benefit from the content created by YouTubers who have been through the same life experiences. Nevertheless, Internet’s patriarchal nature (Zafra, 2011; Mantilla, 2015) is not foreign to YouTube, and, besides homophobia and the misogyny of haters and trolls, new content policies are making it difficult for many YouTubers to continue making content on LGBT topics [1].

This research intends to explore what the topics and discourses introduced by LGBT+ channels are, which of those channels have an increasing number of subscribers, and if these, despite increased visibility, continue to perpetuate gender stereotypes, despite the fact, in some cases, that YouTubers are facing a double discrimination: sexual and gender.

Research aims and methods

The objective of this research has been to explore and analyse the content of the YouTube channels produced by Spanish LGBT+ YouTubers to check whether there are gender biases in their content.

The selection of the sample was made from the analysis of an open-ended question of a survey conducted by researchers to 1,550 adolescents living in Spain aged between 12 and 18 years (M = 15.24; DT = 1.73) on overall media consumption.

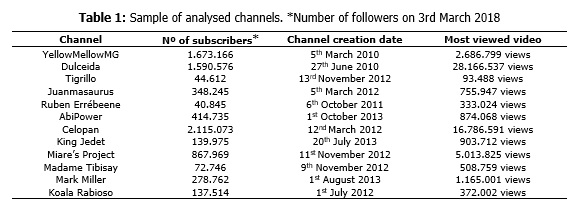

Answers about their favourite YouTube channels were analysed. Twelve channels, whose producers had publicly declared their gender and sexual identity, were selected. Selected channels were named by between 2.88% and 0.047% of the sample and are as follows: YellowMellowMG, Dulceida, Tigrillo, Juanmasaurus, Rubén Errébeene, AbiPower, Celopan, King Jedet, Miare’s Project, Madame Tibisay, MarkMiller and Koala Rabioso (Table 1).

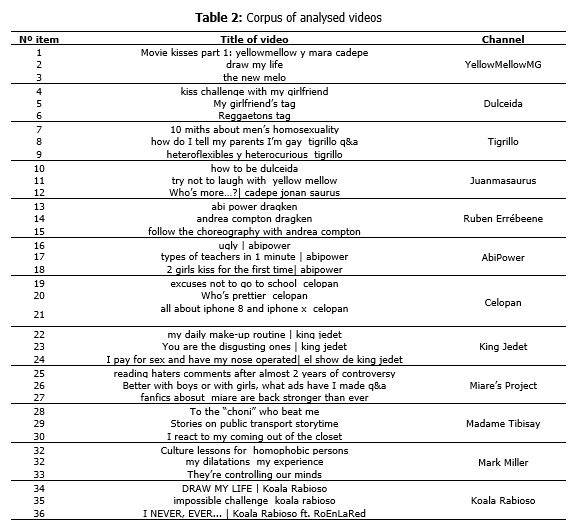

The final corpus consisted of 36 videos, three videos from each one of the selected channels. The selection criteria of the videos that would make up our analysis unit were based on popularity. The selected videos have been included in the "Popular Videos" playlist, given that they are the most viewed by the channel's audience (Table 2). According to Burgess & Green (2009) the influence of a YouTuber can be measured by the number of subscribers and the numbers of video views on their channel.

We draw from the premise that the apparent offer of diversity in YouTube and the appearance of new media stars (YouTubers) with different gender and sexual identities does not significantly enlarge the diversity of media content, either in terms of story or in ways of representation. Even though the Internet allows users to create new content, this apparent diversity has not resulted in changes in the forms of gender representation or the corresponding ways this is received. This research uses the technique of descriptive content analysis, which enables the interpretation of media stories on the selected YouTube channels (Piñuel, 2002). Content analysis has focused on finding the characteristics and the main topics that is expressed in the discourse on these channels. An inductive analysis of the discourse of emerging topics has been carried out, focusing on the new representations of gender and the breaking (or not) of gender stereotypes (Berger, 2016). The videos were fully transcribed, and these transcripts, together with the field notes and reflective comments, formed the raw data for further analysis. It allowed us to identify textual quotes and to see the relationship networks in YouTubers’ discourses. A content analysis was conducted using the computer program Atlas.ti.

We have focused on the following aspects of their videos:

1) Characteristics and formats used by LGBT+ YouTubers and if they follow or they break with YouTube business model;

2) What the main topics of LGBT+ channels are, and whether they are related to personal and life experience;

3) Whether their circumstance as LGBT+ YouTubers affects their gender representation and if they break or not of gender stereotypes, through the language and/or through the content of their videos.

Results

Characteristics of LGBT+ channels: continuity of business model

Entertainment is the primary motive for mainstream YouTube channels, and also of the analysed LGBT+ YouTuber channels. Scolari & Fraticelli (2017) divide the types of videos on YouTube channels into six broad genres: gameplay videos, tutorials, videoclips, interviews, vlogs (life experiences) and television-like videos. Looking at the genre of the video, most of them are television-like videos – as sketches in collaboration with other YouTubers, interviews – in the popular format Questions&Answers made by the fans community through the hashtags in another social networks such as Twitter or Instagram and vlog (life experiences). Within the analysed videos it is observed that fads generalized on YouTube are followed due (to a large extent) to their fans’ demand, and they replicate likewise on every channel (like the ice-bucket challenge or ‘draw my life’) copying one to another:

“Let’s make a video I have never made, the ‘Most Likely to’ TAG, that I have never made with anyone and it is a very used TAG, a challenge. So, let’s go!” (video 12).

“You have asked for it many times, so today at last, I have brought the Kiss Challenge. And for that, as I can’t kiss myself, I’m going to need my adored to come in, the most beautiful woman in the whole planet: Alba Paul (girlfriend)” (video 4)

This type of formats used by LGBT+ YouTubers follow the same logic as mainstream YouTube channels. We must highlight that in the analysed sample it is observed that these categories are not rigid, in just one video, for example, personal experiences can be treated in terms of humour (with sketches or popular ‘TAG’) or in Questions&Answers format (with the audience interaction) during the videos.

Likewise, challenge videos (which could be included within the television-like category), together with collaborations with other YouTubers, are the types of videos which are most popular within our analysed LGBT+ YouTuber channels sample:

“Well, here we are with RoEnLaRed (YouTuber), I have occupied his house to make a challenge that I think is going to be very funny” (video 36).

In the analysed videos, collaborations were found to be very popular among LGBT+ YouTubers, appearing as half of the videos in the analysed sample.

Personal relationships were seen to be a natural part of their conversations. Friends and couples are an important referent among young people and they are also incorporated on YouTubers videos (Pérez-Torres et al., 2018), creating in this way a feeling of virtual community.

“Although you don’t believe it, underneath this make-up and this Barbie-like wig there is Miss Andrea Compton (YouTuber) and today we are going to make a challenge I’ve seen to Mister Jonan (YouTuber) and to Miss Dulceida (YouTuber), who follows the choreography. So, my husband, who loves to make us suffer, has been in charge of choosing the song” (video 15)

This collaboration between LGBT+ YouTubers is very frequent and recurrent, as we can observe in the analysed videos with collaborations between Yellow Mellow and Juanmasaurus or Ruben Errébeene and AbiPower. The objective of these collaborations within the YouTube business model is to bring together different fan communities and they help to feed the content of some channels into others. A good example of synergy between the YouTubers is the video no. 10, one of the most popular videos of Juanmasaurus’ channel, where Juanmasaurus imitates Dulceida and she participates in the joke.

Analysed videos of YouTube channels were identified for having a similar format (with more or less editing, depending on the aesthetics or the intention of the YouTuber) consisting of a natural communication where the YouTuber speaks directly to the camera, as if they were establishing a conversation by Skype (Biel et al., 2011). Analysed LGBT+ channel videos following this video format were also generally located in a private space (YouTubers’ habitual residence), mainly in their bedroom, although they can occasionally be seen in the living room. These locations create a confidence link between YouTubers and their audiences, a link that traditional media does not achieve. It is important to take into account the importance this location has for young audience, where the ‘bedroom culture’ phenomenon takes place (Feixa, 2005), their own place where they can play their videogames, consume cultural products (series, films, YouTube videos ), change the decoration according to each person’s taste, admire ‘stars’, listen to music, dance, they can be with friends without being interrupted by adults. In the analysed cases, space creates complicity with the audience, with whom they feel reflected and identified with the cultural references which they included within the bedroom-film set, and the comments about this home-locations are typical:

“I have to tell you something, if you hear some street noise I’m very sorry but I am filming with the window open, but I have shut the door, and with the door closed there is no power supply, and it really is a pity but I wasn’t going to show you all my apartment and so ” (video 26)

One of the most controversial issues of YouTubers is their business model, as trademark influencers. Publicity and promotions [2] are also present in LGBT+ YouTubers channels in Spain.

As happens in other channels, advertising comments about products are still linked to the channel subject. In the sample of the analysed videos, the express reference of trademarks is very present in the channels of King Jedet and Dulceida, in the case of fashion and beauty products: “Before I start, the Justin Bieber’s T-shirt I’m wearing is from H&M, because you always ask me” (video 22); “My pants are new, from TopShop, and I love them, they are the best jeans because they are elastic, very comfortable and high. And the t-shirt is from Pull&Bear, from the Coachella collection” (video 4); and the comparatives in technology in the case of Celopan: “Today I’m here and we’re going to talk about something which makes me very happy, we’re going to talk about Iphone 8 and iPhone X” (video 21). In the analysed sample, the videos with direct presence of trademarks (through express reference or product placement) is observed in 22% (n=7). Furthermore, trademarks offer personal discounts for the elaboration of branded content:

“I have a new watch! And why am I so excited about it? This was my old watch, very shabby, shredded and disgusting. Then when Daniel Wellington contacted me and asked me ‘do you want a watch?’ I said ‘Please’ I was really excited. And not only that, they have also given me a discount code in case you also want a watch as beautiful and nice as this one” (video 30)

LGBT+ YouTubers also use the platform as a business model linked to their personal brand. This implies that YouTuber's promote products and participate in events at the same time as they promote themselves: "I am studying French at an online school called Lingoda" (video 32). Mark Miller tells his followers that he is studying languages while promoting the language school by offering a discount code.

This duality in the identity construction, which moves between the individualism of the YouTuber and the individualization of society (Beck & Beck-Gernsheim, 2003), is not only a characteristic of virtual spaces, but the YouTuber phenomenon brings it to light in public and with a perennial character. It must not be ignored that the Internet, as Carrera warns (2016, p.245), “requires an active audience, not by virtue of the supposed democratic nature of the medium, but by virtue of the controlling nature of the medium”, an idiosyncrasy that directly lays on the intimate life of the teenager.

Associated with the professionalization of the channel, we can see that LGBT+ YouTubers imprint their personal brand on the aesthetics of the video, from the filming to aesthetics assembly and elements of gay culture. “To be a successful YouTuber not only implies the recognition of a growing audience, but also the fact of being able to generate revenues” (Murolo & Lacorte, 2015). Even though there are cases in the sample, such as the videos of Miare’s Project, Tigrillo or Madame Tibisay, where they intentionally seek an amateur appearance as a distinguishing feature of the channel: “It may be a bit sloppy” (video 22); “As my computer is broken, I now have the script handwritten. Chss! Next level” (video 29); “Have you liked the intro? Don’t get used to that because with my levels of shabbiness this is almost a superproduction” (video 25). This common practice between microcelebrities, social media influencers and YouTubers is termed by Abidin (2017) as "Calibrated amateurism”:

“a practice and aesthetic in which actors in an attention economy labor specifically over crafting contrived authenticity that portrays the raw aesthetic of an amateur, whether or not they really are amateurs by status or practice, by relying on the performance ecology of appropriate platforms, affordances, tools, cultural vernacular, and social capital” (Abidin, 2017, p.1).

They also become accomplices with the audience in this simulation of horizontality by exhibiting the professionals who edit the videos: “Lucas, from now on won’t edit my videos anymore, but don’t you worry because you hadn’t even noticed” (video 6). The professionalization of video recording and editing is evident.

LGBT+ Identity and activism: Beyond specific labels and fads

Even though audiovisual genres used by LGBT+ YouTubers are common to other YouTube channels, their sexual identity and life experience are always present on every discourse. In fact, LGBT+ topics are usually very interconnected to the desires of the audience to know details about their personal life in order to make entertainment and educational videos about collective issues. Videos with an interview format or vlogs that reveal their way of life, things about their couples and families, their favourite series, their feelings, their life history are very popular: “Hello beauties, welcome yet another day to my YouTube channel. This is, this is Alba, my girlfriend, and as all of you had already asked for it, here we are with the tag ‘my girlfriend’” (video 5): “Hello, as you all know about ‘Draw my life’ I’ll send you a smiley face. I was born in a cold January morning ” (video 2).

Furthermore, this tendency to use interaction with the audience in order to generate content, mainly linked to their personal life, is characteristic of the YouTube phenomenon, where the viewer is proactive in the generation of content. Interaction strategy is linked to other social networks, in which they invite their followers to participate and ask questions through the use of hashtags: “Let’s answer some of the questions you have asked via Twitter with the hashtag #AskDulceAlba” (video 5); “Let’s make a challenge you have sent to my Instagram account, if you still don’t follow me in Instagram, you can follow me, here’s the link” (video 35). Or they challenge their followers with sentences such as “if this video reaches 100,000 likes we will kiss each other” (video 1), in order to gain a major engagement with their audience. Through these shared stories, teenagers increase their sense of belonging:

The identity of a fan remains, in some sense, to claim an improper identity, a cultural identity based on one’s commitment to something as seemingly unimportant and trivial as a film or TV series. Even in cultural site where the claiming of a fan identity may seem to be unproblematically secure within fan cultures, at a fan convention, say or on a fan newsgroup a sense of cultural defensiveness remains, along with a felt need to justify fan attachments. (Hills, 2002, p.12)

This high presence of personal issues implies that the LGBT+ diversity issue is very present in most of the analysed videos. 59% (n=19) of analysed videos contain issues about their personal life, which shows that LGBT+ YouTubers have a greater tendency to create videos about their personal issues. Moreover, within these videos about their life experience, 19% (n=6) talk to their audience about their sexual identity and their reasons to identify as being a lesbian, bisexual or homosexual: “You’ll probably not know it if you are new in the channel. Hello, my name is Laura and I consider myself bisexual, I identify myself as being a bisexual girl” (video 30); “According to you, is sex better with guys or girls? I couldn’t answer to this question before because I had had more sex with guys rather than with girls ( ) but now I believe I can affirm that I have liked better sex with girls” (video 26).

In most of the analysed videos, YouTubers talk about their personal experience about coming out of the closet, or about the bullying they suffered at school, in order to help their audience: “How was your childhood as a LGBT+, was it difficult? Yes, to be honest it was difficult. I suffered from homophobic bullying during high school” (video 8). This is especially relevant as stories about LGBT+ inequality and discrimination are excluded from mainstream content or treated in a morbid way by traditional media.

Moreover, some YouTubers such as Mark Miller, Koala Rabioso or Tigrillo go further and, apart from telling their personal experience, they create educational content about LGBT+ issues (16%; n=5), denouncing homophobia, explaining different concepts related with gender identity or impinging on the importance of respect towards diversity:

“My advice always is to ‘not come out of the closet’, to always treat your sexual orientation and your gender identity as something completely natural, without hiding it, the same as cisheterosexual people don’t say it” (video 8).

In this case, the vlog seems to work as a therapeutic tool (Raun, 2012).

“If you are a man and you feel attracted 99% by women and 1% by men, you already are bisexual. In fact, that is what we have Kinsey scale for. It is a scale to classify the different levels of bisexuality” (video 9)

“LGBT+ collective is persecuted in 73 countries around the world, going from the restriction of freedom of speech to death penalty” (video 32).

In this video, humour is also used as a social denunciation. This is the case of Miare’s Project who declares that “it is literally impossible to control all the negative comments I receive” (video 25) and she counteracts it reading haters comments in public by using satire to impugn not only her haters but also society in general, positioning herself in a critical position, as bisexual and as a woman. Likewise, Mark Miller also denounces the homophobia suffered on the Internet: “Every time I upload a video I find these kinds of comments: ‘Your shitty faggot, you’re disgusting’” (video 32). To these comments from haters he responds with an ironic video where he offers a History class about homosexuality, where he directly says: “If you also think that being gay is a contagious disease, I have really bad news for you: then it’s in your blood” (video 32).

Especially relevant is the issue of sexual harassment for YouTubers who are lesbian or bisexual women; this harassment reflects transversally in the discourse of the different videos about her personal experience, and it explicitly appears on 12% (n=4) of the analysed videos. As Mantilla (2015, p.190) points out, “although some of the harassing and abusive online speech might well be popular due to its sensationalistic aspects and therefore is a ‘winning’ meme, such speech nonetheless causes harm to those to whom it is directed. And threats, whether they are made off- or online, have real effects, in real life, to actual people”.

Another of the most frequent topics on the discourses of LGBT+ channels is sexuality, very prevalent in interview videos or vlogs. In contrast to how it is treated in the traditional media, these channels approach sexuality from their own experience. Videos include content about their living as a couple or ex-couples, their sexual identities, their reflexion about their decision, how they were aware of their sexual orientation:

“I was watching a romantic movie, don’t remember what film it was, and the thing is that when they kissed, OMG they were going to live happily ever after, I realized that I was envious of the boy, and I clearly remember I thought ‘I wish I were him to be able to kiss her!’ And in that moment my brain asked, ‘what’s the matter here?’ I was 12 years old ( ) In no moment did I want to avoid it, I faced it but said ‘ok, surprise, now I like women ’ My problem came with the question ‘and what am I going to do next?” (video 30).

“I think sex cannot be divided by genders and it is not definitive at all, right now my experience is like this, and who knows how it will be like in 10 years’ time” (video 26).

This content shows affective-sexual diversity beyond the normative and stereotyped model, and at the same time the channels serve to create a community and to show a critical view of the inequalities and discrimination that LGBT+ communities suffer. Many of these keep adopting what Lovelock (2017) calls a position of ‘successful’ gay/lesbian/bisexual adulthood, defined through the neoliberal ideals of authenticity, self-branding and individual enterprise bound to the phenomenon of YouTube celebrity. Hence, although sexual identity, intended or unintended, is a transversal feature that appears on the LGBT+ YouTubers content, the way to autorepresent their LGBT+ condition differs widely between the YouTubers that were studied, from humour in the case of YellowMellow, Madame Tibisay or Juanmasaurus, to reaffirmation in the case of Dulceida or Celopan.

Presence of gender stereotypes

One of the enablers of persistence of gender socialization lies in the repetition of gender stereotypes, which become internalized by each person who then acts according to that socialization (De Miguel, 2015). The beauty imperative, the natural predisposition to love, the identity of women linked to maternity, the care and preoccupation about others’ wellness, characteristics such as sweetness, tenderness, (feminine) intuition, but also the image of gossiping and smart, worried about the concrete and incapable of being interested in universal issues, sentimental, intuitive, unthinking and visceral, are some of the stereotypes linked to women (Fisas, 1998).

Unlike what happens when analysing the principal content produced by the women who lead the rankings in YouTube in Spain, beauty and fashion entails 11% (n=4) of the analysed videos. It is interesting to mention here King Jedet’s channel, a YouTuber without labels, who creates make-up tutorials that break gender stereotypes that usually associate this kind of content to women. King Jedet never defines his or her gender identity, he or she uses sentences such as “a female servant or a male servant, call it X”.

On the other hand, Dulceida, the other LGBT+ YouTuber channel with content related to fashion and make-up, produces content over standards of beauty and the triumph of the logic of the body and the consequent valuation of sex appeal (Walter, 2010), with a post-feminist discourse (Caballero-Gálvez et al., 2017), without criticism of the patriarchal system.

Gill (2007) points out in her analysis of the post-feminism in the media that contemporary characters, such as Bridget Jones or Ally McBeal, do not break the traditional gender roles. These female characters represent women that defend their personal autonomy like an own value, but continue reinforcing imaginary patriarchal through the importance of physical appearance, sex appeal and family care are an intrinsic part of women’s life project.

However, even post-feministic YouTubers such as Dulceida have contributed to the educational sense of YouTube towards LGBT+ community, opening the door to new discourses and media representations (King, 2009; Fink et al., 2013). In her content, she shows openly her sexuality and talking naturally about the relationship with her girlfriend, which contributes to making visible the sexual diversity between the star system.

It is noted that not only YouTubers like King Jedet or Dulceida, whose videos deal with fashion and beauty issues, perpetuate the imperative beauty stereotype; there is also a reiteration of the idea that wearing make-up implies being prettier, as it can be seen on the analysed video of “La nueva Melo” (“New Melo”) of YellowMellowMG, where a professional make-up artist applies make-up on her: “OMG, (make-up artist: you’re so pretty) as I had never put on make-up, no better way than doing it with a professional artist” (video 3). The non-verbal communication also confirms the idea that YellowMellow is prettier and sexier with makeup, she is gawking at herself and expresses her surprise, the makeup artist and another YouTuber (Juanmasaurus who only his voice is heard in the video 3) are also perplexed and amazed at the look of the YouTuber with makeup.

Under the label of joke or gag, some YouTubers reproduce gender stereotypes. There is also reference to stereotypes about “types” of women when there is humorous content or personal experiences are told. Reference is made to the “sexy morbid secretary” when YellowMellow sees herself with her make-up on her video “La nueva Melo”(“New Melo”) (video 3); “The chav" [3] references women who go out partying to disco clubs and wearing tight clothing in the case of Madame Tibisay (video 28); the Abi Power YouTuber adopts a sweet attitude and a squeaky voice in order to imitate a girl; or “la madre controladora” (Controlling mother) in the case of Celopan All these examples reinforce sexist stereotypes which classify women in the imaginary and traditional roles. Because, even though they are constructed from an “individual free choice” of each YouTuber (De Miguel, 2015, p.37), they create stories which perpetuate the social status-quo which establishes how people should be or behave depending on their gender-sex.

Furthermore, in contrast, when there is a mention of professions that require strength or knowledge, a masculine figure is referred to – as, for example, bricklayers or scientist. In the case of Abi Power’s videos, where she imitates YouTuber or people, what she reiterates again is hegemonic masculinity linked to strength, knowledge, power of reason and the capacity for being a provider (Bonino, 2000).

Other gender stereotypes that constantly appear in a more or less explicit way in the videos is the role of a caring woman. In most of the cases, YouTubers have no children, but they do show this willingness about caring for their family, their couple, and their pets. They show women that, even if they move away aesthetically from the aesthetic canon, are sentimental, worry about others’ well-being, especially about those in her close circle: “You know that my main objective is to buy a house for each of the members of my family and to help them as much as I can” (video 2); and they have a natural predisposition towards love and its power to leave everything behind: “I left everything and I went to a little house in the mountains, in the Basque Country, with Chisme (dog) and Tigrila (girlfriend). And to complete the family, we will adopt a cat, Ninja” (video 34).

However, if we pay attention to the use of language, in contrast to mainstream YouTubers (Rey & Romero-Rodríguez, 2016) or the traditional media (Guerrero Salazar, 2017), we do find a preoccupation with the use of inclusive language [4]. Every YouTuber starts their videos with a greeting, which forms part of their personal brand, and we observed that 72% (n=23) among the analysed videos they make an inclusive use of the language in their audience greeting, although later during the videos, inclusive language is often lost in favour of the custom of using the generic masculine. However, this political and performative use of the language is observed in videos of the transgender YouTuber King Jedet, who speaks in feminine language and greets his or her subscribers “Welcome (girl)friends”. Also, other YouTubers such as Miare’s Project, Madame Tibisay, Celopan or Tigrillo use inclusive presentation formulas using the words people or men or women. However, the use of these more inclusive presentation formulas is not linked to the fact of being a LGBT+ YouTuber, as 28% of the analysed videos, among which those of Ruben Errébeene or Dulceida videos can be found, continue to use the masculine generic.

Conclusion

Transmedia culture, and particularly, the YouTuber phenomenon, has radically changed the audiovisual industry, allowing people outside of big media conglomerates to become communicators with a global influence. Although there are no differences in format or characteristics of the business model between mainstream channels and LGBT+ channels, the accessibility YouTube enables when creating content opens the door to new media stars with a more diverse gender identity, and which moves away from the hegemonic and stereotyped models from the traditional mainstream.

LGBT+ YouTubers have diversified the topics in the videos on their channels, and although they still produce mainly entertaining videos, they have succeeded in introducing subjects related to sexuality, life experiences of the LGBT+ collective, or non-normative gender identities into the media agenda. This new content provides an opportunity for LGBT+ audiences to find referents and to feel recognized.

It is interesting to note the emergence of themes of social denunciation, especially those related to the discrimination that women suffer from being LGBT+ or being women. In the analysed videos, mentions of subjects such as homophobia, sexual harassment, machismo, cyberbullying, online misogyny and homophobia, violence as a false solution to problems, social mandates on canons of beauty, or racism can have a positive educational influence among its audience. It is also important to highlight the appearance of other topics of a feminist nature – although it doesn’t have to come together with a recognition by the YouTuber as feminist – where they denounce or narrate situations such as sexual harassment, misogyny or machismo that they suffer because we live in a patriarchal society.

However, the greater diversity of sexual and gender identities among young YouTubers does not imply a total break with traditional gender stereotypes. Although some YouTubers through their aesthetics move away from traditional stereotypes (men with color-treated hair, women who don't wear make-up or wear tight clothing, transgender or gender fluid), and even criticize the existing gender mandates, they continue to reiterate, more or less explicitly, ideas from traditional gender mandates such as beauty in make-up and physical appearance care, with an increasing presence of video sponsorship and brands.

Gender stereotypes prevail, mainly related to women, and appear linked to humour, a field very resistant to change and which directly connects with thoughts and concepts learnt during gender socialization. They are not outsiders to patriarchal culture.

Even though some gender stereotypes are still reproduced in certain positions adopted by YouTubers, topics introduced by LGBT+ YouTubers constitute an opportunity to change hegemony of traditional discourses and representations. However, it cannot be forgotten that their channels are part of a social network where patriarchal power relationships are inherently inserted. That is why those videos addressing LGBT+ topics are suffering harassment, even the same platform blocks those videos, what has provoked that many YouTubers had to leave the platform or had received sanctions on their views.

Ultimately, LGBT+ YouTubers do expand scrutiny of gender stereotypes, openly showing their sexuality and giving visibility to affective-sexual diversity. Identity expression by LGBT+ YouTubers and their discourses join together reflexivity, commitment with the community, desire for freedom while they adhering to a business model based on selfishness and consumerism (same as all YouTubers). However, part of their job consists in this combination of being, for all eyes in the audience, coherent and authentic.

References

Abidin, C. (2017). #familygoals: Family Influencers, Calibrated Amateurism, and Justifying Young Digital Labor. Social Media + Society, 3(2), 1-15. https://doi.org/10.1177/2056305117707191 [ Links ]

Aguado-Peláez, D., & Martínez-García, P. (2015). ¿Se ha vuelto Disney feminista? Un nuevo modelo de princesas empoderadas. Área Abierta, 15(2), 49-61. http://revistas.ucm.es/index.php/ARAB/article/view/46544/46082 [ Links ]

Berger, A. A. (2016). Media and Communication research methods (4th ed.). United States: SAGE. [ Links ]

Barker, V. (2009). Older adolescents’ motivations for social network site use: The influence of gender, group identity, and collective self-esteem. Cyberpsychology & Behavior, 12(2), 209-213. https://doi.org/10.1089/cpb.2008.0228

Beck, U., & Beck-Gernsheim, E. (2003). La individualización. El individualismo institucionalizado y sus consecuencias sociales y políticas. Barcelona: Paidós. [ Links ]

Biel, J.-I., Aran, O., & Gatica-Pérez, D. (2011). You Are Known by How You Vlog: Personality Impressions and Nonverbal Behavior in YouTube. In ICWSM. http://www.aaai.org/ocs/index.php/ICWSM/ICWSM11/paper/download/2796/3220 [ Links ]

Blanco-Ruiz, M.A. (2017). Las mujeres YouTubers: ¿Ruptura o Perpetuación de los Estereotipos de Género? In Capdevilla, D. (Coord.), Perfiles actuales en la información y en los informadores (pp. 25-36). Madrid: TECNOS. [ Links ]

Bonino, L. (2000). Varones, género y salud mental: Deconstruyendo la “normalidad” masculina. In M. Segarra y A. Carabí (Eds.), Nuevas Masculinidades (pp. 41-64). Barcelona: Icaria.

Burgess, J. (2012). YouTube and the formalisation of amateur media. In Hunter, D. Lobato, Richardson, R. M. y Thomas, J. (Eds.) Amateur Media: Social, Cultural and Legal Perspectives (pp. 53-58). Oxon: Routledge. [ Links ]

Burgess, J., & Green, J. (2009). YouTube: Online Video and Participatory Culture. Cambridge, UK: Polity Press. [ Links ]

Caballero-Gálvez, A., Tortajada, I., & Willem, C. (2017). Authenticity, personal brand and sexual agency: lesbian post-feminism on YouTube. Investigaciones Feministas, 8(2), 353-368. [ Links ]

Carrera, P. (2016). Nosotros y los medios. Prolegómenos para una teoría de la comunicación. Madrid: Biblioteca Nueva. [ Links ]

Carrera, P. (2017). Internet o la Sociedad sin espectáculo. EU-topías. Revista de interculturalidad, comunicación y estudios europeos, 13, 37-46. http://eu-topias.org/nosotros-y-los-medios-pilar-carrera/ [ Links ]

Carrera, P., Limón, N., Herrero, E., & Sainz-de-Baranda, C. (2013). Transmedialidad y ecosistema digital. Historia y Comunicación Social, 18, 535-545. https://doi.org/10.5209/rev_HICS.2013.v18.44257 [ Links ]

Cocker, H. L., & Cronin, J. (2017). Charismatic authority and the YouTuber: Unpacking the new cults of personality. Marketing Theory, 17(4), 455-472. https://doi.org/10.1177/1470593117692022 [ Links ]

Dare-Edwards, H. L. (2014). Shipping bullshit: Twitter rumours, fan/celebrity interaction and questions of authenticity. Celebrity Studies, 5(4), 521-524. https://doi.org/10.1080/19392397.2014.981370 [ Links ]

De Miguel, A. (2015). Neoliberalismo Sexual. El mito de la libre elección. Madrid: Cátedra. [ Links ]

Delgado, A. D. V., & Vozmediano, E. B. (2016). Desigualdad simbólica y comunicación: el sexismo como elemento integrado en la cultura. Revista de estudios de género: La ventana, 5 (44), 24-50. https://dialnet.unirioja.es/servlet/articulo?codigo=5608611 [ Links ]

van Dijk, J. A.G.M. (2006). The Network Society, Social Aspects of New Media. London: Sage Publications. [ Links ]

Erikson, E. (1971). Identidad, juventud y crisis. Buenos Aires: Paidós. [ Links ]

Falcón, L., Díaz-Aguado, M.-J., & Núñez, P. (2016). Advertising and Sexism with focus groups of preadolescents / Publicidad y sexismo analizados en grupos de discusión de preadolescentes. Infancia y Aprendizaje, 39 (2), 244-274. https://doi.org/10.1080/02103702.2015.1133089 [ Links ]

Feixa, A. (2000). Entre el mandato y el deseo: el proceso de adquisición de la identidad sexual y de género. In Flecha, C. & Núñez, M. (Eds.), La Educación de las Mujeres: Nuevas perspectivas (pp. 23-32). Sevilla: Secretariado de publicaciones de la Universidad de Sevilla. [ Links ]

Feixa, C. (2005). La habitación de los adolescentes. Papeles del CEIC (Centro de Estudios sobre la Identidad Colectiva), 16, 1-21 [ Links ]

Fink, M., & Millet, Q. (2013). Trans Media Moments: Tumblr, 2011–2013. Television & New Media., 15 (7), 611–626. https://doi.org/10.1177/1527476413505002 [ Links ]

Fisas, V. (ed.) (1998). El Sexo de la Violencia, Género y Cultura de la Violencia. Barcelona: Editorial ICARIA S.A. [ Links ].

García, A., Catalina, B., & López-de-Ayala, M. (2013). Hábitos de uso en Internet y en las redes sociales de los adolescentes españoles. Comunicar, 41(21), 195-204. https://doi.org/10.3916/C41-2013-19 [ Links ]

Gill, R. (2007). Gender and the Media. United States: Polity Press. [ Links ]

Gill, R. (2009). Mediated intimacy and postfeminism: a discourse analytic examination of sex and relationships advice in a women’s magazine. Discourse & Communication, 3(4), 345-369. https://doi.org/10.1177/1750481309343870

Grandío, M.M. (2008). Series para ¿menores? La realidad que transmite la ficción. Análisis de «Los Simpsons». Sphera Publica, (8), 157–172. [ Links ]

Grandío, M.M. (2009). Audiencia, Fenómeno Fan Y Ficción Televisiva El Caso de Friends. Buenos Aires: LibrosEnRed. [ Links ]

Guarinos, V. (2011). La edad adolescente de la mujer. Estereotipos y prototipos audiovisuales femeninos adolescentes en la propuesta de Disney Channel. Comunicación y Medios, (23), 37-46. https://doi.org/10.5354/rcm.v0i23.26339 [ Links ]

Guerrero Salazar, S. (2017). La prensa deportiva española: sexismo lingüístico y discursivo. UCOPress, Editorial Universidad de Córdoba. [ Links ]

Hill, D. B. (2005). Coming to terms: Using technology to know identity. Sexuality and Culture, 9 (3), 24-52. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12119-005-1013-x [ Links ]

Hills, M. (2002). Fan Cultures. United Kingdom: Routledge. [ Links ]

Holloway, D., Green, L., & Livingstone, S. (2013). Zero to eight. Young children and their Internet use. LSE, London: EU Kids Online. [ Links ]

Jenkins, H. (2006). Convergence Culture: Where Old and New media Collide. New York and London: New York University Press. [ Links ]

Jenkins, H., Ford, S., & Green, J. (2015). Cultura Transmedia: La creación de contenido y valor en una cultura en red. Editorial GEDISA, Barcelona. [ Links ]

Livingstone, S. (1999). New Media, New Audiences? New Media & Society, 1(1), 59-66. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444899001001010 [ Links ]

Lovelock, M. (2017). ‘Is every YouTuber going to make a coming out video eventually?’: YouTube celebrity video bloggers and lesbian and gay identity. Celebrity Studies, 8(1), 87-103. https://doi.org/10.1080/19392397.2016.1214608

Maloney, M., Roberts, S., & Caruso, A. (2017). ‘Mmm I love it, bro!’: Performances of masculinity in YouTube gaming. New Media & Society, 20(5), 1697-1714. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444817703368

Mantilla, K. (2015). Gendertrolling. How misogyny went viral. United States: Praeger. [ Links ]

Mascheroni, G., Vincent, J., & Jimenez, E. (2015). “Girls are addicted to likes so they post semi-naked selfies”: Peer mediation, normativity and the construction of identity online. Cyberpsychology: Journal of Psychosocial Research on Cyberspace, 9(1). https://doi.org/10.5817/CP2015-1-5

Murolo, N. L., & Lacorte, N. (2015). De los bloopers a los YouTubers. Diez años de YouTube en la cultura digital. Question, 1(45), 15-29. Retrieved from http://perio.unlp.edu.ar/ojs/index.php/question/article/view/2407 [ Links ]

Nölke, A.-I. (2018). Making Diversity Conform? An Intersectional, Longitudinal Analysis of LGBT-Specific Mainstream Media Advertisements. Journal of Homosexuality, 65(2), 224-255. https://doi.org/10.1080/00918369.2017.1314163 [ Links ]

Pérez-Torres, V., Pastor-Ruiz, Y., & Abarrou-Ben-Boubaker, S. (2018). YouTuber videos and the construction of adolescent identity. [Los YouTubers y la construcción de la identidad adolescente]. Comunicar, 55, 61-70. https://doi.org/10.3916/C55-2018-06 [ Links ]

Pindado, J. (2011). Los medios de comunicación y la construcción de la identidad adolescente. ZER - Revista de Estudios de Comunicación, 11(21), 11-22. http://www.ehu.eus/ojs/index.php/Zer/article/view/3712/3342 [ Links ]

Piñuel, J.L. (2002). Epistemología, metodología y técnicas del análisis de contenido. Estudios de Sociolingüística 3(1), 1-42. Retrieved from https://journals.equinoxpub.com/index.php/SS/article/view/2459/1671 [ Links ]

Pullen, C., & Cooper, M. (Eds.). (2010). LGBT identity and online new media. United Kingdom: Routledge. [ Links ]

Ramírez-Alvarado, M.D.M., & Cobo Durán, S. (2013). La ficción gay-friendly en las series de televisión españolas. Comunicación y sociedad, 19, 213-235. http://hdl.handle.net/11441/44152 [ Links ]

Ramos-Serrano, M., & Herrero-Diz P. (2016). Unboxing and brands: YouTuber phenomenon through the case study of EvanTubeHD. Prisma Social, 1 (Teens and Ads), 90-120. http://revistaprismasocial.es/article/view/1315 [ Links ]

Raun, T. (2012). DIY Therapy: Exploring Affective Self-Representations in Trans Video Blogs on YouTube. In Karatzogianni A., Kuntsman A. (eds). Digital Cultures and the Politics of Emotion (pp. 165-180). Palgrave Macmillan, London. [ Links ]

Rey, S. R., & Romero-Rodríguez, L. M. (2016). Representación discursiva y lenguaje de los «YouTubers» españoles: Estudio de caso de los «gamers» más populares. index.comunicación, 6(1), 197-224. http://journals.sfu.ca/indexcomunicacion/index.php/indexcomunicacion/article/view/271 [ Links ]

Scolari, C. (2013). Narrativas transmedia: Cuando todos los medios cuentan. Barcelona: Grupo Planeta (GBS). [ Links ]

Scolari, C. A., & Fraticelli, D. (2017). The case of the top Spanish YouTubers: Emerging media subjects and discourse practices in the new media ecology. Convergence: The International Journal of Research into New Media Technologies. https://doi.org/10.1177/1354856517721807 [ Links ]

Tapscott, D. (1998). Growing up digital: the rise of the net generation. New York: McGraw-Hill. [ Links ]

Tolson, A. (2010) A new authenticity? Communicative practices on YouTube. Critical Discourse Studies, 7(4), 277-289. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/17405904.2010.511834 [ Links ]

Tur-Viñes, V., Núñez-Gómez, P., González-Río, M.J. (2018) Menores influyentes en YouTube. Un espacio para la responsabilidad. Revista Latina de Comunicación Social, 73, 1211-1230. http://www.revistalatinacs.org/073paper/1303/62es.html [ Links ]

Walter, N. (2010). Muñecas vivientes. El regreso del sexismo. Madrid: Turner Libros. [ Links ]

Watkins, S. C. (2009). The young & the digital. What the Migration to Social-Networks Sites, Games, and Anytime, Anywhere Media Means for Our Future. Boston: Bacon Press. [ Links ]

Westenberg, W. M. (2016). The influence of YouTubers on teenagers: a descriptive research about the role YouTubers play in the life of their teenage viewers. The Netherlands: University of Twente. [ Links ]

Zacarés, J., Iborra, A., Tomás, J., & Serra, E. (2009). El desarrollo de la identidad en la adolescencia y adultez emergente: una comparación global frente a la identidad en dominios específicos. Anales de Psicología, 25 (2), 36-329. http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=16712958014 [ Links ]

Zafra, R. (2011). Un cuarto propio conectado. Feminismo y creación desde la esfera público-privada online. Asparkía. Investigació feminista, (22), 115-129. http://www.e-revistes.uji.es/index.php/asparkia/article/view/602 [ Links ]

Note

[1] On March, 20th 2018, YouTube had to apologize on Twitter for blocking all types of LGBTQ+ video content (including educational content). The platform's new filters rated these LGBT+ videos as "inappropriate" content. This filter can censor videos just because they have the word "gay" or "lesbian" in the headline with little regard for the content inside. YouTube users started to fight against this filter on social networks by reporting its use with the hashtag #YouTubeIsOverParty.

[2] The type of publicity and products promotion carried out by YouTubers and Influencers would be included within what the Spanish legal frame recognizes as surreptitious advertising. However, no action has been taken against any YouTuber or any preventive action has been adopted as in the USA, with the tag #ad to warn about the advertising content.

[3] In Spanish, the stereotype of a low class or working class woman with bad manners and tight clothing is called “la choni”.

[4] In the Spanish language, generic masculine is used to name the group of people, making other sexes invisible. Inclusive language advocates the use of neutral terms to include all sexes and genders (women, queer, intersex, etc.).