Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Acessos

Acessos

Links relacionados

-

Similares em

SciELO

Similares em

SciELO

Compartilhar

Observatorio (OBS*)

versão On-line ISSN 1646-5954

OBS* vol.12 no.4 Lisboa nov. 2018

Silence or alignment. Organized crime and government as primary definers of news in Mexico

Rubén Arnoldo González*

*Institute of Government Sciences and Strategic Development, Benemérita Universidad Autónoma de Puebla, Mexico

ABSTRACT

The aim of this article is to explain, through the concept of Conflict Discourse System, the influence that Mexican government and organized crime exert on the news-making process. The results of the analysis prove that, considered as sources of information, authorities and cartels frequently determine the agenda and framing of the coverage of their activities. This the outcome of the use of bribes and/or violence. As a result, at the moment of covering these beats, journalists frequently are obliged to choose between silence or alignment. Therefore, rather than reporters, members of the government and drug lords have become the primary definers of news.

Keywords: Mexican journalism; organized crime; Conflict Discourse System; violence; bribery

Introduction

The Mexican press operates within a permanent context of conflict. Because of the violence against reporters and/or media’s economic limitations, journalism is constrained by external agents that exert pressure on news production. On the one hand, journalists have been working under dangerous conditions, especially in certain regions where criminal organizations operate and drug-related crimes are frequent. This situation has turned journalism into a highly risky profession in Mexico (IFJ 2016, Article 19 2018). On the other, as a result of a saturated media market with limited advertisers, Mexican news outlets trade favorable coverage for government advertising contracts. These commercial agreements are the new face of the patron-client relationship between political elites and media owners (Márquez 2014, González 2013a).

In both cases – violence and government advertising – the dissemination of information is not determined according to society’s right to know, but according to other interests instead. That is, rather than by journalists, the production of news is constantly influenced by drug lords and/or government officials. Therefore, the Mexican press is captive to two complex forces of a different nature: organized crime and government, both of which hinder the practice of free journalism through violent and/or economic means.

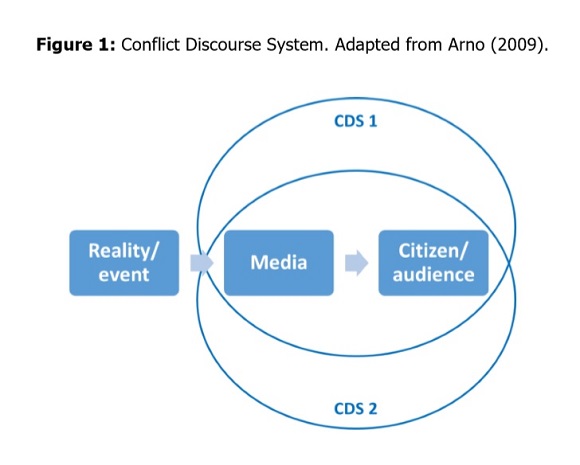

The aim of this study is to discuss the impact of these conflicting agents on the news-making process. For this purpose, this article draws on the concept of Conflict Discourse System – CDS - (Arno 2009), which refers to a set of ideas, values and norms that shape the way a specific group understands reality. Although CDS are immaterial entities, they are represented by institutions, either formal or informal. Regarding the production of news, the role of an institution is to provide a particular context to both media and audiences, so they could perceive any given event according to the parameters of the CDS that it represents. However, there is not only one institution – and, hence, points of view - involved. On the contrary, different CDS are in constant competition to be included in the account of that event. Consequently, the outcome of this struggle for attention is a conflict-centered news story, which is determined by the particular interests of the dominant CDS.

Based upon this framework, and using Mexico as a case study, this paper analyses drug cartels and political authorities as institutions that embody particular Conflict Discourse Systems (organized crime and government, respectively). By so doing, these institutions will be considered as sources of information for journalists, because both of them seek to impose their own story on the news and, thus, influence the coverage of their activities. It is important to mention that this is a theoretical proposal, which is built on previous findings taken from a vast review of literature. For this reason, rather than presenting first-hand empirical evidence, this inquiry discusses the implications of the aforementioned CDS for the news-making process.

This study also contributes to the understanding of the influence that sources exert on the practice of journalism. That is, the academic literature consistently stresses that, rather than reporters, sources are the primary definers of news content (e.g. Sigal 1986, Manning 2001). This is the result of their capability to exploit their symbolic and informative resources (Manning 2001:19-20). On this subject, the inquiry of sources has focused on relatively formal institutions such as government, political parties or armed forces (see for instance Berkowitz and Beach 1993, Voyer et al. 2013, Kim and Jahng 2016), yet other informal sources like organized crime have not been sufficiently studied.

Although there is an increasing interest in other forms of power to determine the media agenda in Mexico, such as the use of violence and/or money (e.g. Schneider 2011, González 2013a, Relly and González 2014, Holland and Ríos 2015), these works draw their conclusions from anecdotal or descriptive evidence, rather than developing an overarching explanation for such a complex process as the influence of sources. In this regard, the originality of this proposal is that it pulls together the evidence of previous studies, and takes it to a higher level of abstraction. Thereby, creating a single explicative framework.

The document is organized as follows: the first section is focused on defining the concept of the Conflict Discourse System. The second presents a basic literature overview on the history of violence against journalists in Mexico, and of government advertising. The following section discusses the implication of these CDS for the news-making process in Mexico. Finally, there are some concluding remarks.

Conflict Discourse System

The aim of this section is to define and explain the concept of Conflict Discourse System (Arno 2009). However, before doing so, it is worth discussing two fundamental issues that will allow us to understand this framework: the news as a constructed reality and the news as a conflict-centered message. Both topics will provide the context in which the CDS develops.

The ultimate goal of news reporting is to make sense of the world we live in, but this is only possible through the vision of journalists. Therefore, a news story is the outcome of a set of filters that shape the raw information in order to transform it into a message (Allan 2004:53-55). These filters represent the whole process of planning, reporting, editing and of packaging facts. Nevertheless, instead of a first-hand account of reality, in many cases the reported fact is actually a created’ fact. This is because reporters tend to rely on specific sources that provide information, which is biased most of the times, since it only represents those sources’ own points of view (Iggers 1999, Seib 2004, Berkowitz 2009). Thus, rather than a mere reflection of reality, news is a constructed reality’ (Schudson 1989).

This idea is closely connected with the notion of news as a conflict-centered message. Since we live in a conflictive world, journalists must cover conflictive situations on a regular basis and, hence, the media has become the arena where conflicts are discussed (Allan 2004, Okunna 2004). Therefore, news stories represent accounts of – actual or perceived – threats and disorders. Nonetheless, members of the audience are only interested in those conflicts that may affect their own interests. In other words, news consumers tend to pay greater attention to news about collective and close conflicts, rather than to those perceived as individual and distant (Priest 2005, Arno 2009, Tumber 2009).

Due to the constant interest in conflict-centered messages, media owners have constantly exploited the commercial potential of this kind of content. Thus, it is a journalistic commonplace that bad news’ is always good news’, at least in economic terms (Chibnall 1980, Okunna 2004, Tumber 2009). But beyond the mere commercial realm, reporting on conflicts involves certain ethical concerns: very often, journalists emphasize the dramatic or violent aspects of the event, to the detriment of a more accurate and balanced account. As a result, news workers might act as mouthpieces of a source, openly take a side or, even worse, create a sense of conflict through – for instance – the he said she said logic’ (Chibnall 1980, Allan 2004, Tumber 2009).

Based upon the notions of news as a constructed reality and news as a conflict-centered message, it is possible to fully understand Arno’s (2009) concept of the Conflict Discourse System. According to him, the origin of this framework is the Civic Consensus News Scenario (CCNS), which is the most basic way to explain how an event is transformed into a news story. The CCNS is integrated by three factors: the event, the media and the citizen. The first element basically represents the situation that took place, which was covered by a journalist, and diffused amongst the audience afterwards. In this scheme, the media play a surveillance role when they publish or broadcast useful information. In so doing, through the diffusion of civic-oriented information, news outlets suggest rational solutions for public affairs. As a result, the informed citizen acts appropriately in personal and political issues; for instance, voting on the day of elections or paying taxes (Arno 2009: 40-42).

The CCNS is supposed to rely on both reporters’ and citizens’ rational choices in terms of news production and consumption, respectively. For that reason, it assumes a general consensus between the interests of media and their audience. Therefore, every aspect of reality that news workers cover is the outcome of an evaluation of its newsworthiness. However, this judgment is based upon journalistic values that, to a certain extent, are shared with society. In other words, journalists are expected to acknowledge what the audience needs – or even wants - to know and, hence, provide that information accordingly (Arno 2009, Sambrook 2016).

Taking the CCNS as a starting point, Arno (2009: 42-50) elaborates the Conflict Discourse System (CDS) illustrated in Figure 1. The CDS model does not eliminate the CCNS, rather it overcomes its limitations: whilst the latter provides rational information for rational decisions, the former provides the identity of the actors. Furthermore, the interaction between media and audience does not take place in a bubble, but instead within a specific social context that determines the values of the news stories, and the receiver’s interpretation of those messages.

According to the CCNS, journalists and audiences are homogeneous groups and, thus, tend to share a common set of cultural insights. The CDS model, however, assumes that those groups are also integrated by different subgroups that are in a continuous state of conflict with one another. For that reason, communities have developed diverse institutions – both formal and informal – to deal with these conflicts. Those institutions represent a Conflict Discourse System, because they offer their members a set of values, beliefs, images, prejudices, knowledge, and so forth. In simpler terms, a CDS is an immaterial entity represented by institutions, whose members share a common way to define themselves and understand the world.

Regarding Figure 1, a CDS is a specific social context that has a twofold impact on the CCNS. Firstly, it determines the way a journalist perceives, understands, evaluates and transmits the information that he or she collects from the field. Secondly, it shapes the audience’s interpretation of each news story. That is, the CDS acts as a mediator between reality/event and media and audience. Nonetheless, there are several CDS influencing the process at a time, not just one. However, since each one of them struggles to impose their view on both reporter and receiver, then, the interaction between different CDS could be either conflictive or collaborative. Therefore, as a result of the CDS influence, journalists can choose to emphasize either conflict or consensus between communities and/or institutions, or even ignore the issue.

In more concrete terms, any given news report should include at least two sides of the story. For instance, an account of a demonstration may include a list of the protesters’ demands, and a summary of the effects on traffic. Both versions came from two different CDS, which are represented by two different institutions: organizers of the protest and the police department, respectively. According to its editorial line, a certain news outlet may stress one side to the detriment of the other, whilst another may even decide not to cover the event at all.

Journalists produce news stories. For that reason, their work must rely on diverse sources of information, which may be individuals or organizations. As the embodiment of a CDS, an institution could be considered a source as well, because it produces information that news outlets use as an input for content production. Due to the wide array of sources that a reporter can use, and the limited access to media that most of those sources actually have, there is a constant struggle to attract reporters’ attention. In other words, different CDS are compelled to compete in order to get publicity within an increasingly saturated marketplace of ideas (Priest 2005, Berkowitz 2009, Arno 2009).

In so doing, a CDS depends on its source power’, which is built upon its resources to actively participate in the agenda management process (Barlow, Barlow and Chiricos 1995, Berkowitz 2009). Such resources may be the access to useful and ready-to-print information, expertise on the field, authority, and money. Therefore, the fittest CDS – through its institutions - will determine not only the information that will be covered by journalists, but also the framing. That is, it will impose both the issues and the spin. As a result, it legitimizes its own discourse of truth, which represents the measure by which the relationship between the event and the journalistic account is evaluated (Seib 2004, Arno 2009).

Going back to the previous example, it might be the case that several local small businesses (book stores, coffee shops ) were affected during the demonstration. However, since they were not organized as a group with a proper spokesperson, their version may have been neglected or even ignored by media. On the contrary, protestors and police are used to interact with reporters on a regular basis, and know how to get coverage.

News is a constructed reality and it is built upon the journalist-source relation. Nonetheless, this relation is constantly and carefully negotiated, because each actor seeks to achieve a particular interest: the reporter needs information and the institution publicity (Berkowitz 2009). In order to fulfil their daily quota of news stories, reporters ought to cultivate good relations with the most important sources, which will supply the information that they demand (Arno 2009). Despite this, an excessive dependence on institutionalized sources to the detriment of a proper journalistic investigation pushes the media to become the mouthpieces of those sources. Even if the provided information would meet the standards that news workers require, it will not be free from the CDS bias (Berkowitz 2009, González 2016). For that reason, news is, after all, not what journalists think, but what their sources say (Sigal 1986:26). This statement summarizes the core argument of this article: Mexican press is frequently constrained by organized crime and government authorities, which are competing CDS whose institutions exert pressure on news workers through violence and/or bribes.

Violence Against the Press and Government Advertising

According to different reports, both academic and journalistic, Mexico is one of the most dangerous countries in the world for journalism and, hence, freedom of press is very limited (Estévez 2010, Hernández and Rodelo 2010, Schneider 2011, Relly and González 2014, Holland and Ríos 2015, IFJ 2016, González and Relly 2016). Even though this is not a new phenomenon, there is a general agreement that it drastically increased with the so-called War on Drugs’, as declared by the then-president Felipe Calderón at the beginning of his administration in December 2006. From that moment, news about aggressions towards reporters have become common, especially attacks on those who have exposed drug lords and/or political authorities (IFJ 2016, Article 19 2018). The violent acts range from verbal threats, stealing their equipment and beatings, to kidnappings, torture and killings.

Although the number of attacks on news workers is not particularly consistent amongst the diversity of organizations that monitor this phenomenon, all of them found very high levels of violence. For instance, the International Federation of Journalists – IFJ - (2016) reports that – from 1990 to 2015 – 120 members of the press have been murdered, positioning Mexico as the third most dangerous country for journalistic practice. On the other hand, the Committee to Protect Journalists – CPJ - (2018) argues that 108 reporters have been killed from 1992 to October 2018. However, only 51 of those crimes can be considered as a direct reprisal for their investigations, whereas in 57 cases the motives are still unclear. Finally, the Human Rights Organization Article 19 (2018) reports 119 assassinations of journalists during the 2000-2018 period, as a possible consequence of their profession.

Despite the inconsistencies regarding their methodological criteria, all of these reports coincide in at least three issues: First, the number of aggressions is significantly high for any modern democracy. Second, most of the victims used to cover stories related to organized crime and/or government corruption. Finally, there is almost a complete impunity regarding those crimes, because the vast majority of them are still not solved, and many were not even properly investigated (Shelley 2001, Waisbord 2002, Estévez 2010, Relly and González 2014, Holland and Ríos 2015, Shirk and Wallman 2015, Márquez 2015, IFJ 2016, Article 19 2018, González and Relly 2016, Brambila, 2017).

In spite of the high number of murdered journalists, previous studies have consistently stressed that violence against the press is not a common practice across the country. In other words, there are specific dangerous areas where news workers face more risks; such as Veracruz, Tamaulipas, Chihuahua or Sinaloa. Since Mexico City is the capital of the country and, hence, the federal government is located there, it was considered a haven for the press (Rodelo 2009, Estévez 2010, Relly and González 2014, Holland and Ríos 2015, Del Palacio 2015; Shirk and Wallman 2015, Article 19 2016, González and Relly 2016, Hughes et al, 2017). This situation changed in August 2015, when the photojournalist Rubén Espinosa was found dead in that city with four other people, all of them tortured and shot to death. He had just moved from Veracruz, where he received several death threats (CPJ 2018). Nevertheless, more recent assassinations during 2018 have taken place in states such as Chiapas and Quintana Roo, which were not previously considered as particularly dangerous spots. This indicates that anti-press violence is becoming an increasingly complex phenomenon and, thus, it can hardly be predicted.

Beyond the mere number of attacks or the region where they took place, aggressions towards journalists have – at least – a threefold set of implications: Individual, organizational, and social. The individual impact of the attacks on media staff is evident, because news workers are the direct victims. Notwithstanding, there are different types of repercussions such as psychological, personal, and professional. The former refer to mental health problems associated with post-traumatic stress, depression, anxiety, and apathy (Estévez 2010, Flores, Reyes and Reidl 2014). The latter are related to, on the one hand, the alteration of personal dynamics (e.g. constant change of phone/mobile number, address, and even city/country of residence). On the other, there is also an impact on the professional routines of the victim (self-censorship, suppressing by-lines, beat swap, increasing use of technology ) (Rodelo 2009, Relly and González 2014, Holland and Ríos 2015, Cottle, Sambrook and Mosdell 2016, González and Relly 2016, Hughes and Márquez 2017).

Regarding the organizational impact of anti-press violence, the most recurrent repercussions are related to the alteration of newsrooms routines. The more frequent changes are, for instance, the decline of investigative journalism, fostered by the implementation of organizational censorship on compromising issues or stories, and the increasing dependence on official press releases (Rodelo 2009, Schneider 2011, Relly and González 2014, Cottle, Sambrook and Mosdell 2016, Hughes and Márquez 2017). As a result, media face limited professional autonomy and, hence, an underdeveloped freedom of expression (Garcés and Arroyave, 2017).

Finally, a scarcely documented impact of the violence against reporters is related to its social repercussions. In broad terms, the aforementioned individual and organizational effects of the attacks on the press foster an uninformed citizenry, whose right to know is not fulfilled due to the lack of information about important issues. Since mainstream news outlets cannot perform their expected watchdog role, social media have been gaining relevance as sources of information. However, online content is saturated with fake news and propaganda. This kind of messages also facilitate the erosion of trustworthiness on both media and government and, ultimately, hinder the consolidation of a democratic society (Rodelo 2009, Estévez 2010, González and Relly 2015, Cottle, Sambrook and Mosdell 2016, Hughes and Márquez 2017).

It is important to mention that members of the cartels are not the only attackers. On the contrary, there are several documented cases – such as the aforementioned Rubén Espinosa’s murder – in which certain government authorities are the main suspects (WOLA and PBI 2016, Article 19 2018, CPJ 2018). However, as an institution, the government also threatens journalism through more refined means, such as advertising contracts.

The use of government advertising as a means of coercion towards the media is not a new phenomenon, neither in México nor in other developing countries (Waisbord 2002, Di Tella and Franceschelli 2011). Even before the evolution of the concept of government advertising, as it is known today, Mexican political authorities have sponsored friendly media. As a result, news outlets have historically been subject to instrumentalization, and not always against their own will (Rodelo 2009, De León 2011, González 2013a, Márquez 2014).

In normative terms, the aim of government advertising should be to facilitate communication between a government and its constituency, by informing the latter about the performance of the former. This suggests that people have the right to know and authorities have the obligation to inform. In so doing, public servants would boost accountability through this kind of publicity (Ruelas and Dupuy 2013). The rationale of the authorities for having one of these contracts with media is to guarantee that the government, despite the political times, has a permanent presence in the news. By a monthly or yearly investment, the news outlet offers a certain amount of pages, or airtime to the government, so it can diffuse its press releases and advertisements. The amount of public money that each media organization receives depends on its reach and impact (González 2013a, 2013b).

The arrival of these formal agreements between political and media power holders was supposed to inaugurate a renewed and more professional way in which political communications operate in Mexico. Notwithstanding, these agreements have been subjected to a permanent halo of suspicion, as this new class of cooperation did not remain at a commercial level. Since the very beginning, these contracts have been used as a means of coercion towards the media and, as a result of that, they have had an evident impact on the way political agents have been covered by media. That is, this commercial relation generally involves an editorial alignment towards the official discourse (Lawson 2002, Rodelo 2009, De León 2011, Márquez 2014, González 2013a, 2013b).

Negotiating a favorable coverage has had different media actors across the time. Especially during the regime of Institutional Revolutionary Party (Partido Revolucionario Institucional, PRI), politicians used to negotiate coverage directly with reporters, because the latter were able to sell advertising besides reporting. Since reporters had to complement their incomes by selling advertising, their pens were compromised because their professional values were put at stake whenever they had to write a story about their customers, who only expected to be treated in a friendly way. In other words, money determined newsworthiness, and economic interest were more important than journalistic interest (Lawson 2002, González 2013a).

However, the weakening of the PRI regime and the opposition victories at local and state level brought a different logic to the journalist-politician relationship, when instead of creating antagonism with the former, the latter started negotiating with their bosses (De León 2011, González 2013a). The political conjuncture strengthened the media owners position by putting them right in front of their customers and, hence, letting them set the new conditions for the official advertising contracts. Notwithstanding, these commercial agreements became instruments of control in both directions: on the one hand, politicians might have lost their influence over individual reporters, but they also gained direct access to director-generals and editors, who actually decide which information is published or not. Despite this, although media owners may have set advantageous conditions for these kinds of contracts, news outlets proved to be economically weak to survive without government advertising revenues too. In summary, these new official advertising contracts have made the interaction between news organizations and political elites more sophisticated, because their commitment towards a mutually supportive relationship is built upon a mercantile logic (Rodelo 2009, De León 2011, González 2013a, Márquez 2014).

By selectively investing in advertising in news organizations, which could hardly survive otherwise, and which suddenly became friendly towards the official authorities after the injection of public resources, the government has also - in practice - structured the Mexican media market to an important extent (Ruelas and Dupuy 2013). Nevertheless, being rescued by the State was not for free, because it necessarily involved an editorial alignment towards the official discourse. In the short terms, an exchange of advertising revenue for favorable coverage became the rule of the journalist-politician relation. However, this interaction was a matter of power and control mediated by a commercial agreement (Lawson 2002, De León 2011, González 2013a). As discussed in the next section, both government advertising and violence against journalists are constraints on Mexican journalism.

Cartels and government as primary definers of news

The aim of this section is to discuss the implications of the violence against journalists and the government advertising for the captivity of the Mexican press. Journalistic practice in Mexico is captive to two strong Conflict Discourse Systems: organized crime and government, which compete with each other to control the media agenda. As has been said before, the news-making process does not take place in a void. On the contrary, it develops within a specific cultural context. However, due to the complexity of our reality, journalists ought to engage with at least three different sets of ideas and values: those from the audience, sources, and themselves (Seib 2004, Arno 2009). Nonetheless, and despite the expected homogeneity between reporters and audience stressed by the aforementioned Civic Consensus News Scenario, sources of information are the primary definers of news content.

The salience of sources is evident in the case of the Mexican press, whose content is determined - to a significant extent - by the aforementioned competing CDS. Each one of them exerts its influence through different institutions and means. Thus, the rest of this article will focus on examining this phenomenon. Regarding the first agent, organized crime, it is worth stressing that its massive media attention started in December 2006. At that time, news accounts about drug cartels gained significant prominence, because those reports were published on a daily basis. They were also considered top stories, and the coverage had an evidently spectacular tone (Gómez and Rodelo 2012). Furthermore, under the bad news’ is good news’ logic, this kind of content proved to be highly profitable (Schack 2011).

Since then, the coverage of the War on Drugs’ has undergone transformations. At the beginning, journalists were taken by surprise and, since hardly any of them had any experience covering armed conflicts, they basically adapted certain features of crime news and sports journalism. By doing so, and without proper investigation, reporters emphasized the daily casualties count and the expectation of who was winning’ the battle. This situation was problematic for the federal government, because its side of the story was neglected. Therefore, the authorities blamed the news outlets, arguing that their reporting was helping the bad guys’, rather than contributing to the accurate evaluation of the actions taken by the police and army. For that reason, a second phase of coverage was determined by a stricter control of information by the government. This was the breaking point of the battle for the control of media agenda by these competing CDS (Hernández and Rodelo 2010, Reyna 2015, Lozano 2016).

Both of these phases exposed one of the main historic limitations of the Mexican press: the lack of investigative journalism. The absence of proper contextualization and the press release dependency, amongst other factors, fostered a poor understanding of the phenomenon and, thus, a lack of criteria for reporting on these stories. Furthermore, in order to compete for revenues, there was a trend towards the tabloidization of media coverage. By stressing only the gory details, mainstream press clearly tended to emphasize the spectacular angle of the events (Hernández and Rodelo 2010, Schack 2011, Gómez and Rodelo 2012, Reyna 2015, Lozano 2016).

Considering organized crime as a Conflict Discourse System – and specific cartels as sources - offers an explanation for this phenomenon. Members of the cartels quickly understood the agenda management process, which involves having control of the information, framing and timing of the news stories. Their strategy proved to be successful, not only in terms of covering their own activities, but also by making the media adopt their own slang in the news.[1] This was achieved in quite a simple way: bribe or bullet. In other words, the source power’ of this CDS was built upon its economic resources or, when this was not persuasive enough, the guns did the talking. Therefore, the outcome was either silence or alignment (Hernández and Rodelo 2010, Gómez and Rodelo 2012, Relly and González 2014, Holland and Ríos 2015).

Beyond the bribe or bullet logic, certain drug lords even had some rustic media strategies. For instance, they leaked information to certain reporters and also provided images (videos or pictures), they monitored press coverage and analyzed how they were portrayed by each news outlet, and they even had spokespersons for dealing with journalists (Hernández and Rodelo 2010, Gómez and Rodelo 2012). Notwithstanding, the more violent gangs also used their own crimes as statements, because certain killings were messages as well. Through torture or beheadings of specific victims, most of them displayed in public places, criminals sent messages either to rivals or authorities (Gómez and Rodelo 2012, Relly and González 2014, Shirk and Wallman 2015, Lozano 2016).

Under these circumstances, the coverage of criminal activities represented a dilemma for news outlets. They had to decide whether to publish a story or not. Either way involved a risk. If they exposed a drug lord, they might have faced a violent retribution. If they decided to self-censor the information, the drug lord might have rewarded’ them with money or something else. However, organized crime is not the only agent that uses violence against journalists. On the contrary, state and local governments utilizes it too. Veracruz, for instance, is one of the places with the most aggressions towards reporters, and many of them are linked to local authorities (Del Palacio 2015, IFJ 2016, WOLA and PBI 2016; Article 19 2018). Nonetheless, the government has other more refined methods to exert pressure on media, such as advertising contracts, which is one of the main features of the second competing CDS that keeps Mexican press captive.

Government advertising is a controversial issue in the relationship between media and political power. As long as there is an advertising contract, Mexican publishers will remain docile. For that reason, these commercial agreements have become a token to trade for favorable coverage. However, this new form of bribery is now negotiated directly between publishers/broadcasters and politicians, leaving individual news workers out of the game. Nonetheless, its purpose remains the same: to influence the news-making process (Rodelo 2009, De León 2011, González 2013a, Márquez 2014, Salazar 2018, Maldonado 2018). Therefore, the differences in coverage and framing could be explained through those differences in advertising investments. This suggests that the more money, the higher and friendlier media attention. In simpler terms, adopting a watchdog or lapdog position towards political elites depends to a significant extent on each news organization’s revenues from government advertising, not just on their own goodwill (Rodelo 2009, De León 2011, González 2013a, Márquez 2014, Salazar 2018, Maldonado 2018).

By trading favorable coverage for mere business purposes, notions of balance, fairness and other newsworthiness values become irrelevant (Champagne 2005, Mosco 2009). As diverse studies prove, most of the Mexican media relies on public money (e.g. De León 2011, González 2013a, Espino 2016, Salazar 2018, Maldonado 2018). As a consequence, their newsrooms work under the logic of not making harsh criticism of their advertisers and, hence, not risking contracts. Accepting this kind of intrusion opposes the foundations of the Civic Consensus News Scenario and stresses the relevance of the Conflict Discourse System model. In other words, the news-making process is not solely determined by rational decisions, but by other external interests as well.

In this regard, the source power’ of the Mexican government is broadly similar to that of organized crime. Both of them utilize their economic strength in order to dominate the agenda management process. In a similar way, political authorities expect either silence or alignment from (paid) news outlets. As a consequence of advertising contracts, news stories are supposed to stress or ignore certain issues, according to the advertiser’s interest. Once again, rather than the public interest, it is a powerful external force that determines the media content that the audience receives.

However, this phenomenon did not just suddenly happen overnight. On the contrary, it is the outcome of a set of conditions that fostered it. On the one hand, rather than hinder it, the War on Drugs’ has proved that organized crime is an influential actor, which – in most of the cases – operates within an environment of almost complete impunity. In addition, the lack of explicit regulations regarding the use of government advertising, plus an increasingly saturated media market, and a highly fragmented audience, have forced Mexican news outlets to neglect journalistic values in order to – literally – survive.

To sum up, contemporary journalism in Mexico is influenced by two competing CDS, whose successful imposition of issues and frames has a threefold explanation. First, news outlets are economically weak and operate within a highly saturated media market. Besides this, most Mexican journalists are under-paid and work under poor conditions. Since organized crime and the government offer significant amounts of money, both media organizations and individual reporters respond to the interests of these paymasters (Rodelo 2009, De León 2011, González 2013a, Márquez 2014, Maldonado 2018). Second, Mexican journalism is easy prey for these dominant CDS due to its historic limitations, such as a lack of investigative reporting and a high dependency on press releases from sources (Hernández and Rodelo 2010, González 2016, Reyna 2015, Salazar 2018). Third, violence against news workers has become a major issue when covering specific events and stories, especially the War on Drugs’ or government corruption. The actual risk of suffering an attack affects the decision of whether to publish or not to publish a news report (Gómez and Rodelo 2012, Relly and González 2014, Holland and Ríos 2015, Hughes and Márquez 2017).

Considering this situation, it is clear that for the news media, the interactional path to both making money and being listened to is not objectivity, but rather the reinforcement of one or the other side’s threatened identity (Arno 2009:177). This is also a feature of an authoritarian media system, in which in order to get legitimization, competing CDS exert overt censorship through different means (Vladisavljevic 2015).

Conclusions

The final argument of this article is that the Mexican press is captive to both organized crime and the government. It means that journalistic practice is constrained by those external forces that exert permanent pressure on news production in order to impose their agendas. As a result of that, democracy is undermined because journalists cannot perform their role as watchdogs and, hence, foster accountability. Nonetheless, these CDS are not the only aspects that constrain media’s performance, because inherent journalistic limitations also play a significant role. In other words, both exogenous (competing CDS) and endogenous factors (lack of investigative reporting and press release dependence) contribute to hold the Mexican press captive.

Considering organized crime and government as Conflict Discourse Systems facilitates the analysis of the implications of sources for the news-making process. Through their own institutions (specific drug cartels or ministries, respectively), these social entities are in constant conflict regarding the coverage of the War on Drugs’. In order to impose their views and values on news stories, they exert pressure via violence and/or money. The expected outcome is either silence or alignment. In this regard, this paper offers a discussion not focused on news organizations per se, but on the conflicting agents around them. That is, besides the product of a process, news is also the outcome of a conflict between competing sources.

Furthermore, through the adaptation of the Conflict Discourse System framework, this document contributes to the explanation of the cartels and government authorities as primary definers of news. That is, this article fosters a better understanding of the pressure that sources exert on the journalistic practice, especially those which are informal such as drug lords. Nonetheless, the theoretical nature of this proposal still requires further fieldwork. In other words, this analysis represents only the first step towards a more robust research program, which would provide empirical evidence of specific cases to support this argument.

Funding

This research has been funded by the Autonomous University of Puebla, through the Research and Postgraduate Studies Vice-chancellor (Vicerrectoría de Investigación y Estudios de Posgrado, VIEP).

References

Allan, S. (2004). News culture. U.K.: Open University Press. [ Links ]

Arno, A. (2009). Alarming reports: Communicating conflict in the daily news (Vol. 1). U.S.A: Berghahn Books. [ Links ]

Article 19. 2018. Periodistas asesinados en México. Retrieved October 2018 from https://articulo19.org/periodistasasesinados/ [ Links ]

Barlow, M. H., Barlow, D. E. and Chiricos, T. G. (1995). Economic conditions and ideologies of crime in the media: a content analysis of crime news. Crime and Delinquency, 41(1), pp 3-19. [ Links ]

Berkowitz, D. A. and Beach, D. W. (1993). News Sources and News Context: The Effect of Routine News, Conflict and Proximity, Journalism and Mass Communication Quarterly, 70(1), pp 4-12 [ Links ]

Berkowitz, D. A. (2009). Reporters and their sources. In K. Wahl-Jorgensen and T. Hanitzch (eds.), The handbook of journalism studies (pp. 103-115). U.S.A.: Routledge. [ Links ]

Brambila, J. (2017). Forced silence: Determinants of journalists killings in Mexico’s states. 2010-2015. Journal of Information Policy, 7, pp 297-326

Champagne, P. (2005). The double dependency: The journalistic field between politics and markets. In R. Benson, and N. Erik (eds.), Bordieu and the journalistic field (pp. 48-63). UK: Polity Press. [ Links ]

Chibnall, S. (1980). Chronicles of the gallows: the social history of crime reporting. In H. Christian, The sociology of journalism and the press (pp. 179-217). U.K.: University of Keele. [ Links ]

Committee to Protect Journalists, (CPJ). 2018. Journalists Killed in Mexico Between 1992 and 2018/Motive Confirmed or Unconfirmed. Retrieved October 2018 from https://cpj.org/data/killed/?status=KilledandmotiveUnconfirmed%5B%5D=Unconfirmedandtype%5B%5D=Journalistandcc_fips%5B%5D=MXandstart_year=1992andend_year=2018andgroup_by=year [ Links ]

Cottle, S., Sambrook, R. and Mosdell, N. (2016). Reporting dangerously. Journalist killings, intimidation and security. UK: Palgrave McMillan [ Links ]

De León, S. (2011). Comunicación pública, transición política y periodismo en México: el caso de Aguascalientes. Comunicación y Sociedad, 15, pp 43-69. [ Links ]

Del Palacio, C. (2015). Periodismo impreso, poderes y violencia en Veracruz 2010-2014. Estrategias de control de la información. Comunicación y Sociedad, 24, pp 19-46. [ Links ]

Di Tella, R. and Franceschelli, I. (2011). Government Advertising and Media Coverage of Corruption Scandals. American Economic Journal: Applied Economics , 3(4), pp 119-151. [ Links ]

Espino, G. (2016). Periodistas precarios en el interior de la República mexicana: atrapados entre las fuerzas del mercado y las presiones de los gobiernos estatales. Revista Mexicana de Ciencias Políticas y Sociales, 28, pp 1-31. [ Links ]

Estévez, D. (2010). Protecting press freedom in an environment of violence and impunity. U.S.A: Wilson Center for International Scholars; Trans-Border Institute; University of San Diego. [ Links ]

Flores, R., Reyes, V. and Reidl, L. M. (2014). El impacto psicológico de la guerra contra el narcotráfico en periodistas mexicanos. Revista Colombiana de Psicología, 23(1), pp 177-193. [ Links ]

Garcés, M. and Arroyave, J. (2017). Autonomía profesional y riesgos de seguridad de los periodistas en Colombia. Perfiles latinoamericanos, 25(49), pp 1-19. [ Links ]

Gómez, G. and Rodelo, F. (2012). El protagonismo de la violencia en los medios de comunicación. In G. Rodríguez (coord.), La realidad social y las violencias. Zona metropolitana de Guadalajara (pp. 319-351). México: INCIDE; CIESAS; CONAVIM; ITESO. [ Links ]

González, C. and Relly, J. E. (2016). The practice and study of journalism in zones of violence in Latin America: Mexico as a case study. Journal of Applied Journalism and Media Studies, 5(1), pp 51-69. [ Links ]

González, R. A. (2013a). Economically-Driven partisanship: Official advertising and political coverage in Mexico: The case of Morelia. Journalism and Mass Communication, 3(1), pp 14-33. [ Links ]

________. (2013b). New players, same old game. Change and continuity in Mexican journalism. Germany: Lambert Academic Publishing. [ Links ]

________. 2016. Investigative journalism in Mexico: Between ideals and realities. The case of Morelia. Estudios sobre el Mensaje Periodístico, 22(1), pp 343-359. [ Links ]

Hernández, M. E. and Rodelo, F. (2010). Dilemas del periodismo mexicano en la cobertura de La Guerra contra el Narcotráfico: ¿Periodismo de guerra o de nota roja?. In Z. Rodríguez (coord.), Entretejidos comunicacionales. Aproximaciones a objetos y campos de la comunicación (pp. 193-228). México: Universidad de Guadalajara. [ Links ]

Holland, B. E. and Ríos, V. (2015). Informally governing information: how criminal rivalry leads to violence against press in Mexico, Journal of Conflict Resolution, 61(5), pp 1095-1119. [ Links ]

Hughes, S. and Márquez, M. (2017). Examining the practices that Mexican journalists employ to reduce risk in a context of violence. International Journal of Communication, 11, pp 499-521. [ Links ]

Hughes, S. et al. (2017). Expanding influences research to insecure democracies. Journalism Studies, 18(5), pp 645-665. [ Links ]

Iggers, J. (1999). Good news, bad news. USA: Westview Press. [ Links ]

International Federation of Journalists (IFJ). 2016. Journalists and media staff killed 1990-2015: 25 years of contribution towards safer journalism. Belgium: IFJ. [ Links ]

Kim, Y. and Jahng, M. R. (2016). Who frames nuclear testing? Understanding frames and news sources in the US and South Korean news coverage of North Korean nuclear testing. The Journal of International Communication, 22(1), pp 126-142. [ Links ]

Lawson, C. H. (2002). Building the fourth estate. Democratization and the rise of a free press in Mexico. USA: University of California Press. [ Links ]

Lozano, J. C. (2016). El acuerdo para la cobertura informativa de la violencia en México: un intento fallido de autorregulación. Comunicación y Sociedad, 26, pp 13-42. [ Links ]

Maldonado, P. (2018). El salario de los periodistas, el ancla a su participación en las redes de clientelismo mediático. Global Media Journal México, 15(28), pp 1-16. [ Links ]

Manning, P. (2001). News and news sources: A critical introduction. U.K.: Sage. [ Links ]

Márquez, M. (2014). Professionalism and journalism ethics in post-authoritarian Mexico: perceptions of news for cash, gifts, and perks. In W. Wyatt (ed.), The ethics of journalism: individual, institutional and cultural influences (pp. 55-63). U.K.: I.B. Tauris; Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism, University of Oxford. [ Links ]

________. (2015). El impacto de la violencia criminal en la cultura periodística posautoritaria: La vulnerabilidad del periodismo regional en México. In C. Del Palacio (coord.), Violencia y periodismo regional en México (pp. 15-47). México: Juan Pablos Editor. [ Links ]

Mosco, V. (2009). The political economy of communication. U.K.: Sage. [ Links ]

Okunna, C. S. (2004). Communication and conflict: a commentary on the role of the media. Africa Media Review, 12(1), pp 7-12. [ Links ]

Priest, S. H. (2005). Risk reporting. Why can’t they ever get it right?. In S. Allan (ed.), Journalism: critical issues (pp. 199-209). U.K.: Open University Press.

Relly, J. E. and González, C. (2014). Silencing Mexico: A study of influences on journalists in the Northern states. The International Journal of Press/Politics, 19(1), pp 108-131. [ Links ]

Reyna, V. H. (2015). ¿El estado más seguro de la frontera? Periodismo, poder e inseguridad pública en Sonora. In C. Del Palacio (coord.), Violencia y periodismo regional en México (pp. 365-403). México: Juan Pablos Editor. [ Links ]

Rodelo, F. (2009). Periodismo en entornos violentos: El caso de los periodistas de Culiacán, Sinaloa. Comunicación y Sociedad, 12, pp 101-118. [ Links ]

Ruelas, A. C. and Dupuy, J. (2013). El costo de la legitimidad: el uso de la publicidad en las entidades federativas. México: Fundar/Article 19. [ Links ]

Salazar, M. G. 2018. ¿Cuarto poder? Mercados, audiencias y contenidos en la prensa estatal mexicana. Política y Gobierno, 25(1), pp 125-152. [ Links ]

Sambrook, R. (2016). Reporting in uncivil societies and why it matters. In Cottle, S., R. Sambrook and N. Mosdell, Reporting dangerously. Journalist killings, intimidation and security (pp 17-35). UK: Palgrave McMillan. [ Links ]

Schack, T. (2011). Twenty-first-century drug warriors: the press, privateers and the for-profit waging of the war on drugs. Media, War and Conflict, 4(2), pp 142-161. [ Links ]

Schneider, L. (2011). Press freedom in Mexico. Politics and organized crime threaten independent reporting. KAS International Reports, 11, pp 39-55. [ Links ]

Schudson, M. (1989). The sociology of news production. Media, Culture and Society, 11(3), pp 263-282. [ Links ]

Seib, P. (2004). Beyond the front lines. How the newsmedia cover a world shaped by war. U.S.A.: Palgrave McMillan. [ Links ]

Shelley, L. (2001). Corruption and organized crime in Mexico in the post-PRI transition’. Journal of Contemporary Crime Justice, 17(3), pp 213-231.

Shirk, D. and Wallman, J. (2015). Understanding Mexico’s drug violence. Journal of Conflict Resolution 59(8), pp 1348-1376.

Sigal, L. (1986). Who? Sources make the news. In Manoff, R. and M. Schudson (eds.), Reading the news (pp. 9-37), U.S.A.: Pantheon Books. [ Links ]

Tumber, H. (2009). Covering war and peace. In K. Wahl-Jorgensen and T. Hanitzch (eds.), The handbook of journalism studies (pp 386-397). U.S.A.: Routledge. [ Links ]

Vladisavljevic, N. (2015). Media framing of political conflict: A review of the literature. Media, Conflict and Democratisation Series [ Links ]

Voyer, M., et al. (2013). Who cares wins: The role of local news and news sources in influencing community responses to marine protected areas. Ocean and Coastal Management, 85, pp 29-38. [ Links ]

Waisbord, S. (2002). Antipress violence and the crisis of the State. The International Journal of Press/Politics, 7(3), pp 90-109. [ Links ]

Washington Office on Latin America (WOLA) and Peace Brigades International (PBI). (2016). Mexico’s mechanism to protect Human Rights defenders and journalists. Progress and continued challenges. U.S.A.: WOLA and PBI

Note

[1] For instance, instead of secuestrado or raptado (both formal synonyms of kidnapped), media referred to that victim as levantado, a term widely used by drug dealers. Another very common word was ejecutado (executed), rather than asesinado (assassinated).