Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Acessos

Acessos

Links relacionados

-

Similares em

SciELO

Similares em

SciELO

Compartilhar

Observatorio (OBS*)

versão On-line ISSN 1646-5954

OBS* vol.12 no.4 Lisboa nov. 2018

TV news and social audience in Europe (EU5): On-screen and Twitter Strategies

Matilde Delgado*, Celina Navarro*, Nuria Garcia-Muñoz*, Pau LLuís*, Elisa Paz*

*Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona, Spain

ABSTRACT

Social networks have altered how viewers watch television and consume information. This new context has obliged broadcasters to adapt their practices to reach viewers in all platforms. In this article, we focus on how the evening news programmes from the general-interest DTT channels in the five main European markets (France, Germany, Italy, Spain, and the United Kingdom) appeal to their social audience. This concept, although ambiguous, refers to the activity of viewers on social networks in relation to the contents broadcast by the television industry in its multiple forms. We analyse both the screen strategies and their activity on their official Twitter accounts. Although the evening news is the anchor of the prime time and one of the main assets to instil the channels with prestige and influence, the conclusions point to a certain neglect of the social audience from the industry in these key programmes. But mostly, our research reveals how the specificities of the format and the nature of the content distinguish the evening news from other live TV shows.

Keywords: Social Audience, Television, Europe, Evening News, Second Screen, Twitter

Introduction

One of the recurring topics in academic and informative dialogue in recent years is that of social audience’. The concept, although ambiguous, refers to the activity of viewers on social networks in relation to the content broadcast by the television industry in its multiple forms. For the general-interest channels there is no escape from this practice since their viewers also interact to a lesser or greater extent on social networks in a synchronously (giving rise to the phenomenon of the second screen) or asynchronously with the broadcast. In general, the digital context and social media are reformulating how broadcasting corporations produce their content and, at the same time, how audiences consume television allowing them to have a more active and communicative role. Since the launch of television, this media’s consumption has always been social (Katz & Lazarsfeld, 1955; Lull, 1980), but the new technological possibilities are increasing this dimension. The use of secondary screens while watching television has become an established practice by viewers, especially young ones (Kätsyri, Kinnunen, Kusumoto, Oittinen, & Ravaja, 2016; Voorveld & Van der Goot, 2013), and has enabled a participatory media system (Hermida, 2010; Jenkins, 2006).

As a consequence of this new audience behaviour, broadcasters are adapting their industry practices to reach viewers on all available platforms and use these new opportunities to add value to their broadcast content (Andrejevic, 2008). Furthermore, digitalization has increased the number of players in each national market with the appearance of Subscription Video on Demand (SVoD) services and online platforms with user-generated content (Iosifidis, 2011). These players are competing with traditional broadcasters for the time and attention of audiences, hindering the economic amortization of linear television.

Regarding news, digital journalism and the speed of online flows have changed how audiences have access to news in the Information era (Castells, 2009). The frenetic exchanges of information make social media platforms, particularly Facebook and Twitter, a central player in these new practices due to their quick and easy reach to audiences. In contrast, traditional media, despite technological advances increasing the speed of their professional routines, are losing their hegemony as a news source for audiences (Newman, Fletcher, Kalogeropoulos, Levy, & Nielsen, 2017), independently of the quality of the information.

Notwithstanding, information is still one of the bases of European general-interest channels. Furthermore, these programmes occupy a vast majority of public channels’ schedules (Delgado, Prado, & Navarro, 2017; Prado & Delgado, 2010) and most public media corporations such as the BBC, RTVE or RAI have channels exclusively dedicated to news. Nevertheless, while European generalist channels have not decreased in their commitment to inform their audiences through linear schedules, they have also expanded their platforms by sharing news content on their websites and creating profiles on social media to reach a broader audience.

Social media has become an essential part of journalism, altering news consumption and helping to increase engagement with each media company but also altering news production (Gearhart & Kang, 2014). In addition, from a format point of view, news programmes are also live and, eventually, as Couldry points out (2004: 3) "liveness or live transmission guarantees a potential connection to shared social realities as they are happening".

This paper focuses on how these changes inflicted by social media are affecting the practices in television news and how they manifest in linear programmes. Therefore, this article studies if and how general-interest channels appeal to their social audiences during news programmes through what we define as on-screen calls-to-action’ (CTAs). We also review the programmes’ official Twitter accounts to evaluate the strategy the corporations follow and if it associates in any way to the television news programmes. The sample includes the most popular prime time news programmes from general-interest channels in the five main European television markets: Germany, Spain, France, Italy and the United Kingdom.

Television Social Audiences

The multiplatform and convergence context (Jenkins, 2006) has enabled a higher participation by audiences regarding television content (Webster & Ksiazek, 2012) than when the active audiences theory was formulated (Fiske, 1987; Hall, 1987; Morley, 1992). Viewers are increasingly sharing and commenting on television content through second screens (Kätsyri et al., 2016; Lochrie & Coulton, 2012; Sørensen, 2016), which is a secondary device, such as a smartphone or a tablet, that is used for something related to television consumption (Giglietto & Selva, 2014). In addition, the creation of content by parts of the audience (user-generated content) has created a more active audience or, said in another way, prosumers (Halpern, Quintas-Froufe, & Fernández-Medina, 2016).

One of the most prominent and studied activities into second screens is commenting on and reading about television content on social media, which is referred to as social television (Gross, Fetter, & Paul-Steuve, 2008). In general terms, social television has been defined as “the communicative exchange about linear television content or that which is at least stimulated by it” (Buschow, Schneider, & Ueberheide, 2014: 129). Selva (2016) emphasises the social connection created between those participating in the conversation: “the social practice of commenting on television shows with peers, friends and unknown people, who are all connected together through various digital devices” (Selva, 2016: 160).

While Facebook is more often used to create fan pages of programmes, Twitter is considered a backchannel for television programmes (Bruns & Burgess, 2011; D’heer & Verdegem, 2014). The simplicity of Twitter use and its encouragement of interaction among users through the use of hashtags are considered the main reasons for using Twitter to comment simultaneously while watching something on-screen (Saavedra Llamas, Rodríguez Fernández, & Barón Dulce, 2015). Some authors argue that commenting on a programme on Twitter or any other social media site adds enjoyment to the consumption of television (Bellman, Robinson, Wooley, & Varan, 2014). Taking the BBC programme Question Time as an example, those who comment actively on Twitter have been referred to as viewertariat due to their simultaneous reviews (Anstead & O’Loughlin, 2011). This role has also been explained traditionally under the umbrella of creative audiences, which includes a part of the social audience that interacts and creates opinion (Deltell Escolar, 2014).

Taking this into account, studying hashtag strategy is substantial since it points to a key Twitter element which aims to coordinate the network’s discussion, as well as revealing users’ intentions in relation to ad hoc audiences/publics (Bruns & Burgess, 2011) around specific hashtags created for the programme. On the other hand, users may decide to post their messages on pre-existing hashtag communities’; however, in particular cases, “the sender is simply unaware of how to effectively target their message to the appropriate community of followers” (Bruns & Burgess, 2011: 5). Regardless, these are all specific audiencing’ practices (Fiske, 1992 as cited by Highfield, Harrington, & Bruns, 2013) of relevant analysis which leads the way in detecting industry’s strategies or the lack of them.

All in all, this group of practices has created a need for the audiovisual industry and media scholars to measure social audiences as a very relevant factor that indicates the level of success of television programmes. Accordingly, social media is seen as an opportunity for traditional media, including linear television, to increase the engagement with their audiences on other platforms and a chance to attract new viewers to their linear schedule (Andrejevic, 2008).

As previously mentioned, the environment in which news facts are consumed nowadays has evolved considerably over the last few years, so journalistic practice has had to adapt to these circumstances when developing news pieces. Social media has altered how journalists in television, newspapers, magazines or the Internet are working and producing news stories. In the current context, there is more information than ever, as well as more platforms to access news. In relation to this, it is convenient to keep in mind the paradigm of network journalism’ (Heinrich, 2011, 2012; Van Leuven, Heinrich, & Deprez, 2015), based on the concept formulated by Castells of network society (2006), which affirms that information moves through a complex network of global information nodes.

This interconnected ecosystem is composed of many nodes, with media companies being just one type of them. It is relevant to note that “the gates of information flows formerly controlled by mainstream media have become permeable” (Van Leuven et al., 2015: 575). However, the size and reach of the nodes differ considerably. As an example, big news organizations such as CNN or the BBC have a significant impact on the information network, while smaller corporations have a lower level of influence but are still needed to make the network work properly. In other words, “traditional news organizations as nodes within a complex system of interconnected nodes cannot ignore the other nodes, big or small” (Van Leuven et al., 2015: 576).

In addition to this networked context with multiple sources of information, audiences can access news through an increasing number of platforms. As a consequence, the news practice of traditional broadcasters has to adapt to this new situation and construct new strategies to maintain its audience and engage with new viewers. Social media enables news producers to be permanently connected to the public and either drive audiences to their other platforms through links or appeal to the traditional broadcast news programmes. Furthermore, corporations have added calls-to-action (CTAs) on-screen that we define as ways of driving their conventional audience to social platforms while they are watching a programme by a printed text or an oral mention by the news anchor, for example.

According to the report published by Reuters Institute analysing 36 countries worldwide, including the countries of the sample (France, Germany, Italy, Spain, and the United Kingdom), social media has become an important source of news in recent years, going as far as surpassing television for ages between 18 and 24 (Newman et al., 2017). This trend is particularly significant in Spain where in 2017 more than half of the population with Internet access used social media as a news source closely followed only by the United States. The report also highlights the relevance of messaging apps for accessing news with Whatsapp being the most prominent (Newman et al., 2017).

Nonetheless, the characteristics of social media, and Twitter in particular, limit the information that can be shared through these sites. Some authors consider that the presence of headlines on social media stimulates audience interest of being informed and, as a consequence, the use of social media by news companies or sections tend to direct users from those profiles to different sites that belong to the same company. This results in strong data/interaction traffic between the corporation's social media profile and its other areas of activity (Newman, Dutton, & Blank, 2012). This interaction is very important for traditional broadcasters since the platform where media corporations have the majority of advertising income is linear television, even in today’s digital context. Therefore, the strategy to transfer users from social media or online platforms to linear broadcasting is essential and should be at the core of journalism practice today. In addition to these economic reasons, having a presence on social media allows broadcasters to reach younger audiences which is of huge importance for traditional television. (Cameron, & Geidner, 2014).

In terms of news production, social media has also altered the sourcing practices of journalists, questioning the perception of the truth and the validity of these sources (Gearhart & Kang, 2014). Some authors argue that the use of social media as a credible source is more accepted and used during breaking news or in situations where information is difficult to access (Lotan et al., 2011; Van Leuven et al., 2015). The Arab Spring is an example where media organizations used social media messages to create information due to the difficulty in getting on-the-ground information (Harlow & Johnson, 2011). However, the use of Twitter by some politicians, Trump being the paradigmatic example, has obligated newsrooms to use this platform as a regular valid source. “This practice does not come without dangers, as issues of accuracy, impartiality or interpretive problems due to language and translation difficulties, do complicate the process of sourcing social media” (Van Leuven et al., 2015: 577). Related to this, one of the biggest dangers with the use of Twitter as a news source is the easy spread of intentional misinformation, which is a growing concern worldwide (WEF, 2014).

In order to counteract these risks within the news industry, the New York Times and other news organizations, such as the BBC, have generated a framework for the use of social media within the corporation. In the case of RTVE, the Spanish public media corporation, a polemic code was established by its board of directors, where they forbid journalists working for them to post information on their social media profiles until the organization publishes it on theirs (Borraz, 2015). What does seem to be certain is the critical role of Twitter in shaping the news agenda (Deller & Hallam, 2011). Most studies analysing television information programmes and social media have focused on political shows with interviews or debates (elections) or current affairs (D’heer & Verdegem, 2014; Olof Larsson, 2013). In this paper, instead, we will focus on news programmes. This type of programme and other television formats share the aspect of being broadcast in real-time, that is, they are live television formats. Regarding the synergy between live television programmes and the social network Twitter, Highfield et. al.(2013) point out to the role of Twitter as a backchannel for live television. Some other authors, like Bourdon (2000) or Couldry (2004), refer to the concept of liveness’ in the sense that real-time programmes may increase the connection to a reality that is happening at that very moment. Nevertheless, as Deller and Hallam (2011) mention, this concept has created a large number of responses, especially because it is a media-built phenomenon. In the specific case of prime time news programmes, which is our study’s focus, liveness’ refers to events that are not necessarily taking place at that exact moment, but could have happened during the day. Considering this, the concept liveness’ also concerns events that are already part of the public debate everywhere, including, of course, Twitter. This would entail significant differences in both the capacity of creating a community that is interested in the particular television event, as well as the industry's strategy when appealing to its social audience.

Based on this theoretical and contextual framework, this study aims to answer the three following questions:

RQ1: What are the on-screen strategies created by evening news programmes in order to appeal to their audience and guide them to digital platforms?

RQ2: What are the corporations’ strategies on their official Twitter accounts? What relations, if any, exists between these strategies on the social network and the programme itself?

RQ3: Are there differences in the strategy of corporations by countries and by type of ownership?

Methods

This study has been carried out within the GRISS research group (Research Group on Image, Sound and Synthesis) from the Audiovisual Communication and Advertising Department at the Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona (Spain). It has been developed within the framework project “Social Networks and European General-Interest Television (EU-5): Screen Uses and Network Activity of Audiences” (RSTV), of the National R&D Plan, funded by the Spanish Ministry of Economy and Competitiveness (MINECO-FEDER) (ref.: CSO2015-65350-R). The focus of this project is to explore and explain the synergies that allow broadcasters to innovate in their social network strategies through the most popular European television content, including a comparison between different genres, and to identify correlations between the broadcaster’s actions and the social audience’s response.

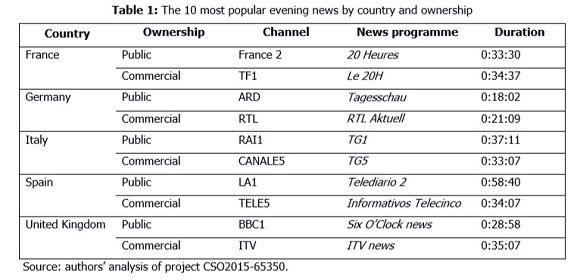

This paper focuses on how television industry appeals to social audiences in the most successful information programmes in France, Germany, Italy, Spain, and the United Kingdom, the main five European television markets. It also delves into the industry’s strategies on their Twitter profiles and how they are articulated in relation to the sampled programmes. To define which the most successful’ programmes are, we selected ten information programmes with the highest audience ratings broadcast by general-interest channels on DTT, both public (France 2, France 3, Das Erste, ZDF, Rai Uno, Rai Due, Rai Tre,La1, La2, BBC One, andBBC Two),and commercial(TF1, M6, ProSieben, Sat.1, RTL, Canale 5, Italia 1, Rete 4, Antena 3, Cuatro, La Sexta, Telecinco, ITV1, and Channel 4). The criteria that we followed was to find the two highest-rated programmes for each country, one broadcast by a public channel and one by a commercial channel, composing a sample of 10 information programmes.

To find the highest-rated programme by country and by each type of ownership, we used the share data from different sources for each market. In France, the data was collected from Mediametrie, in Germany from the AGF company, in Italy from Auditel, in Spain from Kantar Media and in the United Kingdom from BARB. With these figures, the most successful information programmes in the European countries analysed were all evening news broadcasts. The sample contains the following programmes:

All evening news programmes considered were recorded on 16th of March, 2017 and content analysis was used to explore and describe the calls-to-action (CTAs) of each programme. As mentioned previously, we describe this unit of analysis as the on-screen call to the use of digital platforms and this could be joining the programme's community on social media, using the programme's specific hashtags on social media, visiting the website or using the programme's app. This aims to describe the level that producers or schedulers attract and encourage social audience’s participation on news programmes, how they do it (forms of insertion), how these actions eventually are related to the content and which social networks or online platforms (Facebook, Youtube, Twitter, Instagram, app or website) they highlight.

As mentioned before, we also look into their social media activity and study which strategy corporations use on their official Twitter accounts during the entire day in which the sample was broadcast. Twitonomy was used to download all the tweets present on the timeline of the news programme’s accounts during 16th March, 2017. Initially, the tweets were divided between original, retweet or replies. In addition, in order to be able to describe the strategy of the news Twitter accounts, we analyse all media objects that can appear on tweets: Hashtags, text, links, videos, images, mentions and emojis. For this analysis, we have to highlight that, due to the nature of these accounts, most tweets will be related to a news story. Furthermore, the tweets analysed will only be the originals and replies, that is, the ones written by the same account since, as pointed out above, one of the research questions asks if there is any relationship or association between the tweets posted on the official Twitter accounts and the broadcast programmes themselves.

Hashtags are the most characteristic media object on Twitter. In this paper, we have counted the number of hashtags present (and their number of reiterations) on the official accounts included in the sample and their typology according to if they appeal to a more or less specific hashtag community, linked to a greater or lesser extent to the programme itself (Programme), to a piece of news (News Fact) or to a generic topic (Generic). That is to say, if the hashtag appeals to a community not built specifically around the programme nor a news fact and we find hashtags referred to locations, personalities, organizations or companies and others (such as the name of a disease, or a universal topic).

The body of text in the tweet is also capital and we specifically look for references to the content of the programme, or if the tweets are used mainly as a different channel of information to reach the audience. The links included on tweets also represent significant information on their strategy with the aim of knowing whether they link to other online platforms in the corporation and which type of content they want to promote. Mentions, a username preceded by the asperand or at’ sign (@), are explored to see who corporations actively decide to highlight and appeal to in their news accounts.

The media objects of videos and images are relevant in order to analyse if corporations post their content from the linear programme on Twitter. Therefore, we will consider if these objects are extracted from any of their television programmes or if they add any brand distinction, such as the channel’s logo, to them. Finally, the emojis can be a strategic element to make tweets relate emotionally with the audience or to guide users through categories or themes using routines or common elements between tweets.

With this methodological design that contains two parts clearly distinguished (the analysis of the on-screen CTAs on linear news programme and the analysis of Twitter) we try to find patterns, strategies or the lack of them, as well as taking a comparative approach on two main levels: differences amongst countries and distinctions regarding channel’s ownership.

Intercoder reliability tests were conducted for both the content analysis of the CTAs in the programmes and the variables of the media objects. For broadcast news programmes, a reliability test was executed based on the viewing and analysis of one of the programmes with an overall coefficient of .868 (Holsti Proceed, 1969). In second place, the tweets of the German public news programme, Tagesschau (60 tweets during the day of the sample), were analysed by the three coders to verify the intercoder reliability in all the variables of the media objects. All coefficients surpassed .85 which are considered to be above acceptable levels.

Results

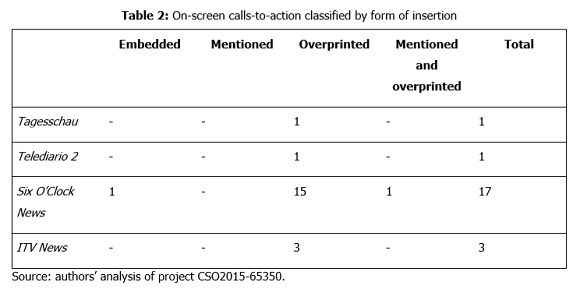

The first result regarding the strategies of the television industry when attracting social audiences during the evening news broadcast is the apparent lack of interest. Only four out of the ten most popular European evening news programmes use calls-to-action (CTAs) to appeal to theirsocial audience. In our sample, the total number of CTAs reach 22, most of them performed by Six O’Clock News along the whole duration of the programme. In this title, the vast majority of the CTAs are shown on the lower part of the screen at the same time as the name of the reporter. At a significantly lower amount, ITV News used 3 CTAs when there was a printed presentation of a news reporter. Finally, Tagesschau and Telediario 2, with only 1 CTA each, did so right before their ending credits.

As it can be seen in Table 2, when analysing how the CTAs are portrayed, the most-used method by broadcasters is overprint, that is, they choose to display the information on a part of the screen without interrupting the oral discourse of the anchor or reporter. Six O’Clock News is the only programme that has an oral mention to a second screen platform while overprinting the same information and an embedded CTA, referring to an appeal to a digital platform in the same set of the programme, in this case shown on a screen behind the anchor. In contrast, it has to be highlighted that none of the evening news programmes use CTA mentions exclusively.

Regarding the content of the CTAs, on the BBC most of them refer to the news website of the corporation and show its URL on-screen. Only one of their CTAs overprints a hashtag (#BBCNewsatSix), an element that can refer, mainly, to the social networks of Twitter and Instagram. In the case of Tagesschau the information about their news app is overprinted. Finally, all CTAs by Telediario 2 and ITV News are mentions. In the first case, they direct to their Twitter official news account (@telediario_tve) and in the latter, they choose to showcase the accounts of some of the reporters (@Peston, @MMGeissler and @RagehOmaar).

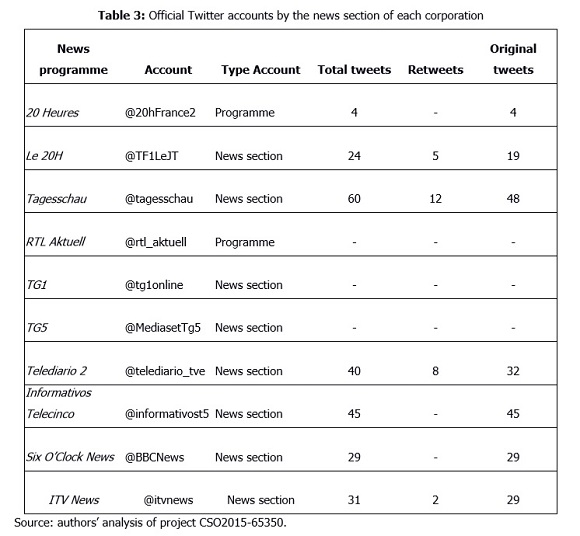

In general terms, as shown above, broadcasters choose not to place their efforts to appeal to social audiences at the centre of their strategy when airing the evening news, with the exception of Six O’Clock News. In this case, the corporation uses a significant number of CTAs (17) during its 29-minute programme. Nevertheless, they have all created Twitter accounts with different strategies across the five main European markets. Due to the specific broadcast routines of television news programmes, in contrast to other genres such as fiction or reality shows, the same information section of corporations produces different news programmes during the day and even, in some cases, across different channels. Furthermore, time is a key element in news events, particularly on social media, where news flows have increased their speed significantly.

In consequence, while in the other television genres mentioned have their specific Twitter account, the specificities of news programmes have compelled most European corporations to create accounts where all the newsworthy content produced is shared beyond the titles of each television programme or, in the case of the BBC, even including their radio stations. In this case they have a main account (@BBCNewsUK) and other secondary accounts that target a more specific topic (i.e., @BBCSport, @BBCNewsEnts, @BBCWorld). The case of the public Spanish corporation is also unusual since they have chosen to create a Twitter account for their main channel’s news programmes and another for their 24h information channel. Another strategy, only used by 20 Heures and RTL Aktuell, is to opt to have an exclusive account for the evening news programme.

Moving on to the analysis of the 233 tweets posted by these accounts during the date the sample, the results show that there is a clear disparity in broadcaster usage. The first piece of data analysed is the number of tweets posted during the date of the sample. The news service with the largest number of posted tweets is the German public corporation (@tagesschau) with a total of 60 tweets on May 16th, 2017. The other accounts with some activity vary from 4 to 45 tweets (Table 3). In contrast, three news accounts had no activity whatsoever on that specific day: German RTL Aktuell, broadcast on commercial channel RTL; Italian TG1 from on public broadcaster RAI 1 and Italian TG5, which is aired on a commercial channel, Canale 5.

In terms of the specific time when corporations post their tweets, results show that messages are launched throughout the day with very low synchrony with the linear broadcasting of the evening news programme or, in the case of general news accounts, any of the news programmes of the channel (not including the 24 hours news channels). From the total of 233 tweets, the vast majority are original (206), meaning that the tweets were produced by the official account that was captured. The remaining 27 are retweets, these texts being a repost, a message created by another user that by clicking the “retweet” button appears on the official account’s profile. Lastly, it is significant that none of the accounts replied to users, which highlights the lack of interest in establishing any dialogue with their social audience.

Delving into the differences between corporations, the accounts retweeting posts by other users are @TF1LeJT (n = 5), @tagesschau (n = 12), @telediario_tve (n = 8), and, to a lesser extent, @itvnews (n = 2). However, in these cases, retweeted posts are mainly from profiles of the same corporation or from their journalists, that is in-house retweeting. For example, three of the posts retweeted by @tagesschau were written by the account @tagesthemen, which is an account that a different foreign correspondent is in charge of each week. Another example is the two retweets by @TinaHassel, the director of ARD-Hauptstadtstudio (one of the studios of ARD, the German public corporation). In the case of @telediario_tve the retweets are from the account of the news only channel (@24h_tve, n = 5), the official account of the corporation (@rtve, n = 2) and the profile with the weather forecast updates (@ElTiempo_tve, n = 1).

For the rest of the accounts, the aim of diffusing their own information, through original content, is the prime and only objective. This data can provide us with a preliminary finding: in general terms, corporations do not use this platform to create a more horizontal communication with their audiences, they rather use it as an extension to spread and expand their content.

Media Objects Strategy

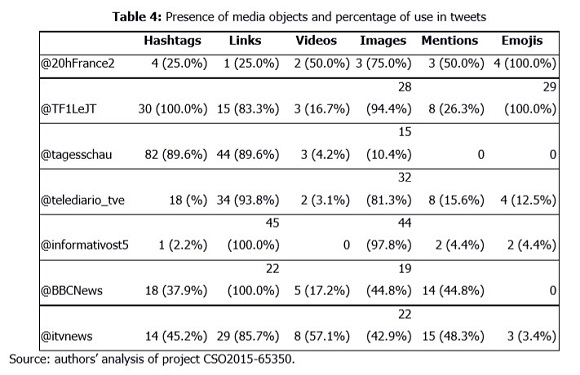

Moving on to the analysis of the media objects, this section will only refer to the seven official news accounts with activity during the sample day. As can be seen in Table 4, links and images are the most commonly used elements by the news accounts in the majority of the original tweets in the sample. In contrast, videos are, surprisingly, less frequent elements despite the fact that television corporations are the ones creating the tweets’ content.

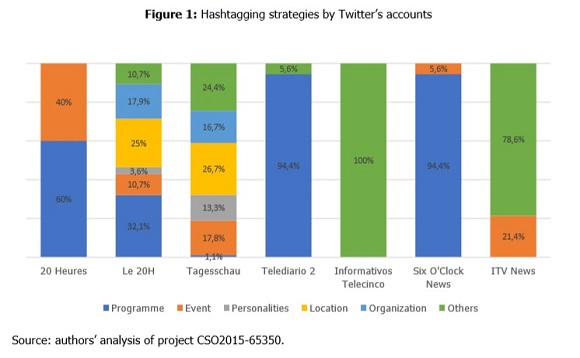

Hashtags, as previously noted, are the media objects with more significance when describing the general strategy of the channel since they greatly influence the position of tweets within Twitter, as well as their visibility to general users (Bruns & Burgess, 2011). They also highlight specific strategies on audiencing, using the term that comes from cultural studies research as Highfield et al. (2013) point out. The hashtag recurrence and usage strategy is diverse and does not respond to specific logic or general guidelines among the different countries or ownerships.

In the first general analysis, the number of hashtags used by the news accounts in their original tweets has been focused on. The accounts of @tagesschau and the two French @20hFrance2 and @TF1LeJT use more than one hashtag per tweet on average. The German public news account is the one with the most recurrent use of hashtags with almost two per tweet (82 hashtags/48 original tweets). From this total, there are 60 unique ones with an average repetition ratio of 1.4. According to Bruns and Burgess (2015) and their concept of “ad-hoc publics”, the strategy of using a significant number of hashtags could be interpreted as a method to try to position the brand (programme, section or channel) in as many pre-existing communities as possible.

In the case of the public corporations of Spain (@telediario_tve) and the United Kingdom (@BBCNews), only one hashtag is ever used at the end of each tweet while the remaining @informativost5 and @itvnews use this media object sporadically. In the case of the Spanish commercial corporation, they only use the generic hashtag #Últimahora (#Breakingnews in English) in one tweet. ITV uses hashtags more frequently, in 14 of their 29 original tweets.

As can be seen in Figure 1, the use of highly generic hashtags (personalities, locations, organizations and others) is significant, as well as the practice of posting hashtags referring to particular events but with no relation to or identification with the programme or the channel whatsoever. A paradigmatic case of this phenomenon is @tagesschau. The German news section uses a wide range of hashtags (a total of 82), all of them being either vastly generic (e.g., #China, #USA) or related to the news fact but without using any identification of the brand. These practices note that the programme could be dismissing the idea of creating specific audiences related to the programme or the corporation, or that it could be trying to increase its presence on pre-existing hashtags communities. Another possibility is the total lack of a specific hashtag strategy. As Bruns and Burgess (2011) indicate, a generic hashtag like #China will rarely create a community with a common interest around it. In addition, very rarely will the posts in such a generic hashtag make any reference to the specific news story.

Only four sampled programmes with Twitter activity use identifying hashtags, either referring to the programme itself or to another of the channel’s news services. These are @20hFrance2 with the hashtags #JT20H (referring to the whole programme) and #olildu20h and #entretienpolitique (mentioning a specific section), @TF1LeJT also remarking on the different news editions with #Le13H and #Le20H, @telediario_tve using #TDMatinal, #TD1 and #TD2 (corresponding to the three news editions broadcast during the day) and, finally, @tagesschau with the hashtag of the section #videoblog. This latter case has been categorised as a programme hashtag because is the name of a regular section even though is a highly generic hashtag and it is doubtful that an ad hoc public around the section of the programme will be able to be created.

News programmes’ hashtag strategies need to be interpreted from their own content’s nature. News facts do not happen while the programme is being aired, thus it is complicated taking advantages of the liveness’ that other programmes such as reality shows have. Events happen throughout the day and the interested communities are prior to the programme’s broadcast and, probably, independent from it. As to our sample, the most evident examples concerning the exploitation of liveness are those that are related to the production’s sections, such as a live interview. This is the case with the hashtag #entretienpolitique used by the French 20 Heures to refer to the interview of a politician during a section of the news programme.

The analysis of the text has only focused on the presence, if any, of references to the broadcast programmes or channel. Only three corporations make a written reference to the television programmes: @informativost5 with one reference at the start of the programme, @20hFrance2 promoting the broadcast of a specific section of the evening news and finally @BBCNews in the same tweet that used the hashtag #BBCNewsatSix.

Regarding the URLs attached to the tweets, most of them are links to their own corporate websites aiming to redirect Twitter users to their own platform. Within their websites, there are three sections present. Firstly, and most broadly used by all corporations, is to provide the URL of a piece of news that includes text and images or videos. Secondly, a link to the catch-up service of the corporation. Focusing on the connection between Twitter accounts and the linear news programmes, the only corporations that post the link to watch their television evening news programme on catch-up are the Spanish and British public channels, La1 and BBC One respectively. Thirdly, links to the live stream of the 24 hours news channel are posted. This last case is used only by the Spanish public corporation (27 out of 32 links direct to the live stream). @20hFrance2 is the exception to this strategy, since it is the only profile which posted one link that redirects to an external site.

The use of mentions is also diverse among the different accounts but with this media object our results highlight some similarities between countries. We have analysed if the mentions are linked to a journalist, a programme or an anchorman/anchorwoman working on the channel. The French programmes, @20hFrance2 and @TF1LeJT, use mentions to refer to celebrities related to the current affairs or that were invited to their programmes. In Spain, even though they do not use a lot of mentions, especially @informativost5 with just two, both accounts use Twitter as a tool to link with journalists working on the channel or other programmes. On the British case, @BBCNews and @itvnews use the mention resource to relate the content of the tweet to journalists, news or programmes, fourteen times on @itvnews and fifteen times on @BBCNews.

When analysing the media objects defined as videos we refer exclusively to videos that can be watched directly on the social network platform. As previously mentioned, the scarce use of this object by the news accounts is significant and somehow surprising since broadcasters stream their videos online and they are made available later on catch up services. Considering only the active accounts, the corporations posting more videos in proportion to their total activity are those from France and the United Kingdom. @20hFrance2 includes videos on half of its tweets, although the account only posted 4 tweets during the day of the sample, and @TF1LeJT posted videos in 12.5% of their tweets, that is, in 3 out of 24. In the case of the UK, @BBCNews included 5 videos, while @itvnews used 8. In the majority of the cases all videos include the channel or the news programme’s logo. In spite of this habit, @itvnews posted 4 videos with logo and 4 without any reference to the brand.

Opposed to videos, images are used by all the corporations that are active on the platform. Notwithstanding, in general terms they do not include the corresponding logo or any reference to the news programme or corporation. Therefore, these images can end up circulating on the social network losing their link to the brand. At the same time, @tagesschau is the only corporation that posts its own infographics on Twitter, which are also used on their linear broadcasting, presented as static images or GIFs. Since in this situation it is always exclusive content, they include their logo so it is linked to their brand and anyone who reuses it automatically gives credit to the corporation and is indirectly pointing out to it.

Finally, the last media object that has been analysed is emojis. While their impact on the strategy of corporations is more limited, they can make tweets more appealing to users and can help on some occasions to easily identify the content of the tweet. Our results show that the only corporations using emojis regularly are from France, revealing a similarity between the public and commercial channels from the same country with this media object. The public @20hFrance2 uses an emoji at the beginning of each tweet and uses an arrow sign or a picture of a television. In the case of @TF1LeJT they use a television sign at the beginning of 10 tweets and a finger pointing to the link included in all tweets.

Conclusions

Despite how much the news media use Twitter as a new source of information as the paradigmatic case of Donald Trump and the publicity of his Twitter activity shows, there is a certain neglect of social audiences by the evening news programmes in the five main European markets. On-screen CTAs are barely used and the use of official Twitter accounts is weak, to say the least. However, there is the significant exception of Six O’Clock news (BBC One). The British public corporation has always stood out when adapting to new platforms. A good example of this is when they went from calling themselves a broadcasting’ company to being a media’ company, including VOD and other online platforms on the same level as their traditional content, as Smith, P. and Steemers, J. (2007) point out.

With a conservative approach, the most showcased platform in news programmes is their own website and the most common way in which the programmes use calls-to-action (CTAs) is by overprinting them on-screen. However, there are three programmes that promote the use of Twitter, the social network that is used mostly for news (Newman et al., 2017), by use of a hashtag (Six O’Clock news) or mentions (Telediario 2 and ITV News).

Regarding the official Twitter accounts, this research found out that while all have official profiles, the trend is to include in the same account all the news editions or even the 24h news channel. Furthermore, only seven out of ten had active accounts during our analysis. In terms of ownership, it does not seem to make an actual difference. However, there are some differences among countries related to their social network practices. In this sense, the Italian case has to be highlighted since there is no activity on either the account of the public corporation nor the commercial, which would be an interesting area for further investigation. This is significant since the most popular news programmes in each country are being analysed. In addition, while the German public corporation is the one with the highest activity on the social network, the commercial RTL channel did not post any tweets during the day of the sample and the level of activity is generally very low.

The tweets posted by the active accounts are mainly original, which highlights the clear aim of using the social network to diffuse their own information and not to create conversation among the other users. This is a clear strategy by media companies since they want to maintain on Twitter their prime role as gatekeepers (Hilbert, Vázquez, Halpern, Valenzuela, & Arriagada, 2017). In terms of referencing the content of the programme, we found that the tweets work as a parallel strategy, given the fact that the accounts post throughout the day and there are not a lot of specific references to the content of the programme in most of the media objects.

The hashtagging strategy followed by corporations is not oriented to trigger interaction with the primary text, which is in our case, regarding the news programmes. In the specific case of the news sections of broadcasters, the strategy followed by most Twitter official accounts is to use both generic hashtags and specific hashtags for the programmes. While in the first case they will rarely find pre-existing communities around the specific topic of the news, the latter will appeal almost entirely only to their own followers network. In contrast, less frequently used type of hashtags, such as those exclusively referring to an event, help to raise awareness in the topic among receivers of the tweet.

These questionable strategies are certainly motivated by the distinctive features of the news format. On the one hand, the broadcast routines of daily news programmes move at a slower pace than news on other types of media, such as social networks themselves. Hence, the content that constitutes the television programme, that is news pieces, is what makes it extremely difficult to create ad hoc publics linked to both the facts and the broadcast programme. Channels choose to encourage their followers and audiences to move from pre-existing hashtag communities to the corporation’s website. On the other hand, although the evening news is the most-watched news programme, it is part of the channel’s news service, which is the section that mainly takes control and expresses its own voice on social profiles.

With this hashtagging strategy it can be argued that they do not help their tweets to have a more successful impact. Nevertheless, all corporations use URLs to redirect traffic to their own website, as previous studies have also concluded (Newman et al., 2012), thereby greatly extending the range of the content on an active account. Therefore, we can affirm that broadcasters aim to create a strong connection with Twitter users and make it seem to be the centre of their digital platforms. Mentions is another media object that, to a lesser extent, is used to create a relationship between the Twitter account and the news brand by including accounts of the journalists or other news programmes by the corporation. Finally, videos are not a recurrent element on these accounts, surprisingly, and images rarely have a logo that links them to the brand.

Therefore, it can be affirmed that there is a dysfunctional relationship between the television news format and Twitter since the very significant differences of information speed and ways of production seems to hinder transfers between these two platforms when concerning news facts. Nevertheless, the website of the corporations is situated as a moderator since Twitter users as well as broadcast television viewers are directed to it. Besides, even though we are talking about live programmes, we also need to take into account that the lack of synchronicity between the broadcast and the news events decreases the power that is usually related to live programmes. Regarding the relationship between the concept of liveness’ and social network activity, it does not occur on the same terms as it does in other formats, such as domestic fiction or reality formats. In news programmes, news stories prevail on the broadcasters’ Twitter strategy.

To conclude, our results show either a lack of interest in social media by the news corporations or a lack of a defined strategy when it comes to appeal and interaction with sampled evening news’ social audience. As a basis for future research it would be of great interest to investigate the response to the on-screen calls-to-action and the posted tweets by analysing the account’s number of followers and impact that their posts receive in the form of retweets, likes and replies, which would shed light upon the industry strategy.

References

Andrejevic, M. (2008). Watching television without pity: The productivity of online fans. Television & New Media, 1(9), 24–46. [ Links ]

Anstead, N., & O’Loughlin, B. (2011). The emerging viewertariat and BBC Question Time: Television debate and real-time commenting online. The International Journal of Press/Politics, 16(4), 440–462.

Bellman, S., Robinson, J. A., Wooley, B., & Varan, D. (2014). The effects of social TV on television advertising effectiveness. Journal of Marketing Communications, 58(3), 400–419. [ Links ]

Borraz, M. (2015). TVE regula el uso de redes sociales por parte de sus periodistas. Eldiario.es. Retrieved from https://www.eldiario.es/sociedad/TVE-periodistas-difundir-Twitter-publicadas_0_370963280.html [ Links ]

Bourdon, J. (2000). Live television is still alive: on television as an unfulfilled promise. Media, Culture & Society, 22(5), 531–556. [ Links ]

Bruns, A., & Burgess, J. (2011). The use of twitter hashtags in the formation of Ad Hoc publics. In European Consortium for Political Research Conference (pp. [ Links ] 25–27). Reykjavik, Iceland.

Buschow, C., Schneider, B., & Ueberheide, S. (2014). Tweeting television: Exploring communication activities on Twitter while watching TV. Communications, 39(2), 129–149. [ Links ]

Cameron, J., & Geidner, N. (2014). Something old, something new, something borrowed from something blue: Experiments on dual viewing TV and Twitter. Journal of Broadcasting & Electronic Media, 58 (3), 400-419. [ Links ]

Castells, M. (2009). Communication power. New York: Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

Couldry, N. (2004). Liveness, “reality”, and the mediated habitus from television to the mobile phone. The Communication Review, 7, 353–361.

D’heer, E., & Verdegem, P. (2014). What social media data mean for audience studies: a multidimensional investigation of Twitter use during a current affairs TV programme. Information, Communication & Society, 18(2), 221–234.

Delgado, M., Prado, E., & Navarro, C. (2017). Ficción televisiva en Europa (EU5): Origen, circulación de productos y puesta en parrilla. El Profesional de La Información, 26(1), 132–140. [ Links ]

Deller, R., & Hallam, S. (2011). Twittering on: “Audience research and participation using Twitter.” Participations - Journal of Audience & Reception Studies, 8(1), 216–245.

Deltell Escolar, L. (2014). Audiencia social versus audiencia creativa: Caso de estudio Twitter. Estudios Sobre El Mensaje Periodístico, 20(1), 33–47. [ Links ]

Fiske, J. (1987). Television culture. London: Routledge. [ Links ]

Gearhart, S., & Kang, S. (2014). Social media in television news: The effects of Twitter and Facebook comments on journalism. Electronic News, 8(4), 243–259. [ Links ]

Giglietto, F., & Selva, D. (2014). Second Screen and participation: A content analysis on a full season dataset of tweets. Journal of Communication, 64, 260–277. [ Links ]

Gross, T., Fetter, M., & Paul-Steuve, T. (2008). Toward advanced social TV in a cooperative media space. International Journal of Human-Computer Interaction, 24(2), 155–173. [ Links ]

Hall, S. (1987). “Encoding-Decoding.” In S. Hall, D. Hobson, A. Lowe, & P. Willis (Eds.), Culture, media and language (pp. 128–138). London: Hutchinson Education.

Halpern, D., Quintas-Froufe, N., & Fernández-Medina, F. (2016). Interacciones entre la televisión y su audiencia social: Hacia una conceptualización comunicacional. El Profesional de La Información, 25(3), 367–375. [ Links ]

Harlow, S., & Johnson, T. (2011). The Arab Spring | Overthrowing the protest paradigm? How The New York Times, Global Voices and Twitter covered the Egyptian Revolution. International Journal of Communication, 5(16), 1359–1374. [ Links ]

Heinrich, A. (2011). Network journalism: Journalistic practice in interactive spaces. New York: Routledge. [ Links ]

Heinrich, A. (2012). Foreign reporting in the sphere of network journalism. Journalism Practice, 6(5–6), 766–775. [ Links ]

Hermida, A. (2010). From TV to Twitter: How ambient news became ambient journalism. M/C Journal, 13(2), 1–8. [ Links ]

Highfield, T., Harrington, S., & Bruns, A. (2013). Twitter as a technology for audiencing and fandom. Information, Communication & Society, 16(3), 315–339. [ Links ]

Hilbert, M., Vázquez, J., Halpern, D., Valenzuela, S., & Arriagada, E. (2017). One Step, two Step, network step? Complementary perspectives on communication flows in twittered citizen protests. Social Science Computer Review, 35(4), 444–461. [ Links ]

Holsti (1969). Content analysis for the social sciences and humanities. Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley.

Iosifidis, P. (2011). Growing pains? The transition to digital television in Europe. European Journal of Communication, 26(1), 3–17. [ Links ]

Jenkins, H. (2006). Convergence culture: Where old and new media collide. New York & London: New York University Press. [ Links ]

Kätsyri, J., Kinnunen, T., Kusumoto, K., Oittinen, P., & Ravaja, N. (2016). Negativity bias in media mutlitasking: The effects of negative social media messages on attention to television news broadcasts. PLos ONE, 11(5), 1–21. [ Links ]

Katz, E., & Lazarsfeld, P. (1955). Personal influence: The part played by people in the flow of mass communication. Glencoe, IL: Free Press.

Krippendorff, K. (2004). Reliability in content analysis: Some common misconceptions and recommendations. Human Communication Research, 30(3), 411–433. [ Links ]

Lochrie, M., & Coulton, P. (2012). Sharing the viewing experience through Second Screen. In EuroITV’ [ Links ]12. Berlin.

Lotan, G., Graeff, E., Ananny, M., Gaffney, D., Pearce, I., & Boyd, D. (2011). The revolutions were tweeted: Information flows during the 2011 Tunisian and Egyptian revolutions. International Journal of Communication, 1375–1405. [ Links ]

Lull, J. (1980). The social uses of television. Human Communication Research, 6(3), 197–209. [ Links ]

Morley, D. (1992). Television, audiences and cultural studies. London: Routledge. [ Links ]

Newman, N., Dutton, W., & Blank, G. (2012). Social media in the changing ecology of news: The fourth and fifth estates in Britain. International Journal of Internet Science, 7(1), 6–22. [ Links ]

Newman, N., Fletcher, R., Kalogeropoulos, A., Levy, D. AL, & Nielsen, L. (2017). Reuters Institute Digital News Report 2017. Retrieved from https://reutersinstitute.politics.ox.ac.uk/sites/default/files/Digital News Report 2017 web_0.pdf?utm_source=digitalnewsreport.org&utm_medium=referral [ Links ]

Olof Larsson, A. (2013). Tweeting the viewer - Use of twitter in a talk show context. Journal of Broadcasting & Electronic Media, 57(2), 135–152. [ Links ]

Prado, E., & Delgado, M. (2010). La televisión generalista en la era digital. Tendencias internacionales de programación. Telos, 84. [ Links ]

Saavedra Llamas, M., Rodríguez Fernández, L., & Barón Dulce, G. (2015). Audiencia social en España: Estrategias de éxito en la televisión nacional. Icono 14, 13, 215–237. [ Links ]

Selva, D. (2016). Social television: Audience and political engagement. Television & New Media, 17(2), 159–173. [ Links ]

Smith, P., & Steemers, J. (2007). BBC to the rescue! Digital switchover and the reinvention of public service broadcasting in Britain. Javnost, 14(1), 39–55. [ Links ]

Sørensen, I. E. (2016). The revival of live TV: Liveness in a multiplatform context. Media, Culture & Society, 38(3), 381–399. [ Links ]

Tuitele. (2014). Tuitele da paso a Kantar Twitter TV Ratings. Retrieved from http://blog.tuitele.tv/ [ Links ]

Van Leuven, S., Heinrich, A., & Deprez, A. (2015). Foreign reporting and sourcing practices in the network sphere: A quantitative content analysis of the Arab Spring in Belgian news media. New Media & Society, 17(4), 573–591. [ Links ]

Voorveld, H. A., & Van der Goot, M. (2013). Age differences in media multitasking: A diary study. Journal of Broadcasting & Electronic Media, 57(3), 392–408. [ Links ]

Webster, J. G., & Ksiazek, T. B. (2012). The dynamics of audience fragmentation: Public Attention in an Age of Digital Media. Journal of Communication, 62, 39–56. [ Links ]

World Economic Forum. (2014). The rapid spread of misinformation online. Available at: http://reports.weforum.org/outlook-14/top-ten-trends-category-page/10-the-rapid-spread-of-misinformation-online/ [ Links ]