Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Acessos

Acessos

Links relacionados

-

Similares em

SciELO

Similares em

SciELO

Compartilhar

Observatorio (OBS*)

versão On-line ISSN 1646-5954

OBS* vol.12 no.4 Lisboa nov. 2018

Tracking the distribution of non-professional subtitles to study new audiences

David Orrego Carmona*, Simon Richter**

*Aston University, United Kingdom/University of the Free State, South Africa

**Freie Universität Berlin, Germany

ABSTRACT

This paper analyzes the consumers in the context of non-professional subtitling (NPS). Using web scraping techniques to collect data about the downloading rate of non-professional subtitles we explore the behavior of consumers. Drawing on the case of the subtitles for House of Cards in Addic7ed.com, a popular multilingual non-professional subtitle distribution website, we describe the consumption of non-professional subtitles and the users’ response. After outlining the situation of the international audiences for audiovisual products and the relevance of consumers as the driving force behind NPS communities, we analyze the collected data in terms of their interest in the originality of the content and their wish to access the content immediately after it is available. Our findings indicate that the users of non-professional subtitles are highly engaged consumers, eager to access the content as soon as possible and interested in watching it in its original language (English), even with intralingual (same-language) subtitles.

Keywords: Non-professional subtitling, subtitles, translation, viewers, audience studies

Introduction

Non-professional subtitling (NPS) communities are seen as “knowledge disseminators in the Internet era” (Chen, 2010) which overcome geographical and linguistic barriers to distributing translated content. Two main characteristics have been attributed to fan subtitling (fansubbing) and NPS: immediacy and enlarged distribution. These communities work against the clock to complete the subtitles as soon as the audiovisual products are released (Gambier, 2013) and create new distribution channels for audiovisual content at a global level. The non-professional subtitlers engaging in these communities can be seen as what Tapscott and Williams (2006) call prosumers. They are active users who do not only act as consumers but who also enact powers traditionally allocated to producers. By taking on some of the tasks of producers and exerting the power that technology grants them, non-professional subtitlers challenge traditional distribution channels and create alternative networks of distribution of content.

Research in the field of NPS has so far concentrated on those more active participants and not on the users of the subtitles. In this article, we look at NPS from the consumption side to gain insights into the audience of the subtitles. Considering users make up the largest subgroup of members of online communities (Yang, Li, & Huang, 2016), our aim was to study their online behavior to illustrate the reach of NPS. We propose to use digital trace data, particularly the download figures of subtitles over time, as means to draw a broader picture of the generally hard to investigate majority of users. We track the number of downloaded subtitles for the third season of the series House of Cards (Netflix 2013-Present) from the non-professional subtitling website Addic7ed.com as a case study to explore, for the first time, the behavior of consumers of non-professional subtitles. Using web-scrapping techniques, we monitored the demand for subtitles in nine languages over a two-week period (27 February-13 March 2015). Our findings suggest consumers are primarily interested in accessing same-language subtitles in English, place great value in immediate access to the content and experience a high degree of engagement with the product over a relatively short period of time.

Online communities and lurkers

Collaborative and participatory communities such as those producing non-professional subtitles are made up of active users who engage in the community’s activities. While the main feature of these members is that they have an active role in how they engage with content production and consumption (unlike more passive users), it is also true that not all members engage and participate in the same way, nor do they invest the same amount of time and effort in the communities (Sun, Rau, & Ma, 2014). According to Nielsen’s 90-9-1 rule (2006), participation inequality causes a recurrent phenomenon in online communities. In most of these communities, there are three broadly defined profiles of members: a small 1% of users who are heavy contributors and produce the majority of the community’s content, 9% of users who are intermittent contributors, and the lurkers, users who read and observe the communities’ activities but do not contribute to content production. Lurkers are the largest group and makeup 90% of the members. This rule has been tested, in some cases confirming the estimation (van Mierlo, 2014), and in others proposing an adjusted alternative, such as a 70-20-10 distribution (Schneider, 2011). Regardless of the distribution of the three proposed categories, the largest share of community members does not participate actively in the creation of content but rather in the consumption of the material produced by the more committed members. Considering the prominence of lurkers, exploring their behavior in online subtitling communities should help us to better understand the societal impact of NPS.

Although they are not heavy or intermittent contributors, lurkers engage actively in the participatory culture. They share more characteristics with contributors than with traditional TV users. They are an essential part of the NPS phenomenon. As agents in the participatory culture environment, they comply with certain technical requirements and have a specific technological and content-specific expertise. In technical terms, they need to have working and stable Internet access, which in many cases is taken as a given but still is a barrier for a large part of the global population, limiting the possibilities of a portion of users to become lurkers. Additionally, they need to invest time and effort to follow the original scheduling of the audiovisual content, identifying when it is made available, locate trustable sources and download the content. The disposition of cultural and technological capitals is a pre-condition for this group of users; apart from their personal interest, lurkers should invest a variety of resources to access the audiovisual content they want.

Non-professional subtitle consumers

Non-professional subtitles, or fan subtitles (fansubs), are subtitles produced or distributed by volunteers in online communities. The practice dates back to the fansubbing of anime in the 1980s and saw an exponential growth in the 2000s when US shows became international hits with considerably large audiences in non-English speaking countries (Catania, 2015; Evans, 2011). Consumers of all types of audiovisual content realized that it was possible to create their own subtitles to distribute audiovisual content around the world over the internet; thus, groups dedicated to the distribution of underground films as well as US TV series and films emerged and adopted mechanisms similar to those used by the fansubbers.

Along with fansubbing’s expansion, there also came a change in the motivations behind NPS. While fansubbing came into existence as a way to fight the censorship exerted in the early translations of anime and the low number of anime products that were being imported to the US, the NPS of US TV series was an opposition to the lengthy delays in international releases (Cubbison, 2005; Lee, 2009). This growth also generated more complexity in the NPS sphere in general. While traditional fansubbing communities, formed by hardcore fans who were highly committed and emotionally attached to the content they translate (Díaz Cintas & Muñoz Sánchez, 2006; Ferrer Simó, 2005; Massidda, 2012), still exist, new communities are also made up of people who simply enjoy making subtitles, who find fulfillment in belonging to a community that provides access for a larger audience, or who see an opportunity to establish a network of like-minded people (Barra, 2009; Luczaj, Holy-Luczaj, & Cwiek-Rogalska, 2014; Orrego-Carmona, 2015).

In the last fifteen years, NPS has become a common topic in Translation Studies and neighboring areas. Since the first publications appeared, at the beginning of the 2000s (Cubbison, 2005; Leonard, 2005; Nornes, 1999), researchers have become interested in the area (Barra, 2009; Bold, 2011; Casarini, 2014; Fernández Costales, 2013; Luczaj et al., 2014; Massidda, 2012; O’Hagan, 2008, 2013; Olohan, 2014; Orrego-Carmona, 2011, 2016; Pérez-González, 2007, 2010, 2012; Pym, Orrego-Carmona, & Torres-Simón, 2016; Wilcock, 2013). Regardless of their specific objectives, the majority of the studies have focused on two elements of NPS: the production agents (i.e. the individuals and the communities involved in creating the subtitles), and the subtitles produced by those communities or individuals. While studying the active participants of virtual communities provides a good understanding of their culture, analyzing the traces left by the lurkers might enlarge our understanding of the exchange occurring in the community and its societal impact. Also, from a rather system theory based perspective, we may conclude what broader function the system of NPS may fulfill at an international scale.

Exploring non-professional subtitling consumers

The use of non-professional subtitles for audiovisual products is generally associated with two underlying reasons related to access. First, viewers want to access audiovisual products as soon as the materials are released in the US. Second, viewers resist dubbing as a traditionally accepted audiovisual translation mode, and prefer subtitling as a way of accessing a more original version of the products. These two reasons interact and strengthen the interest in NPS as a valid option to access audiovisual content.

Readily accessing the audiovisual content available has always been a motivation for users of NPS (Barra, 2009; Díaz Cintas & Muñoz Sánchez, 2006). The viewers’ reluctance to wait for the international release of their favorite shows moved them to do their own subtitles to support the distribution of content online (Leonard, 2005; Massidda, 2012). Due to their attachment to the audiovisual products, fans have the pressure to “know about [the audiovisual products] as soon as possible” (Gambier, 2014) when they are released. In an interconnected world, viewers want to consume the products shortly after they are available, in some cases even binge-watching them as soon as they can get hold of them (Orrego-Carmona, 2018). For these users, time is so important that Jiménez-Crespo claims that “the speed at which the translation is needed” (2017, p. 124) is one of the factors that defines the type of quality that suits collaborative translation environments. The fixation with immediate access has even altered the rhythms of official distribution channels. To counter the effects of piracy, producers, official distributors, TV channels and video streaming services have reduced the delays in the international distribution of their products.

Equally, the chase for originality is also deeply embedded in the fansubbing tradition. Viewers started to fansub because the official sanitized versions did not allow them to access the source culture through the audiovisual products (Bold, 2011; Nornes, 1999; Schules, 2012). This is particularly true in the case of anime (Díaz Cintas & Muñoz Sánchez, 2006; Dwyer, 2012), when non-professional subtitles are used as a way to access Japanese culture. The popularization of fansubbing in traditionally dubbing countries such as Spain, Italy and France seems to be associated to a mistrust of dubbing or a preference for subtitling as a mode of translation that allows for a better understanding of the source culture. According to Massidda in her exploration of fansubbing in Italy, dubbing “is nowadays perceived as an outmoded, unreliable, and ultimately unsuitable mode of audiovisual transfer” (2012, p. 14). On the contrary, unlike the traditional TV and film industries, Western NPS communities seem to be more interested in producing source-oriented subtitles that emphasize the foreign nature of the contents (Casarini, 2014; Nornes, 2007).

Departing from these key motivations for relying on non-professional subtitles, we derived two guiding research questions for our exploratory study of the demand for non-professional subtitles. Based on the immediacy motivation to use non-professional subtitles we would assume the demand for non-professional subtitles to be highest shortly after the audiovisual products are released and subsequently weaken over time.

Immediacy question (Q1): Is the demand for non-professional subtitles dependent on the time since the release of the audiovisual content?

The originality motivation emphasizes the interest of the audiences on subtitling as a tool to access a more original version of the audiovisual content. Considering this interest might be stronger among audiences who are normally exposed to dubbing, we wanted to learn about which languages are more popular among the users of non-professional subtitles and whether these languages can be associated with traditionally dubbing countries.

Originality question (Q2): What are the more popular languages in non-professional subtitles?

In this paper, we draw on the case of the distribution of Netflix’ House of Cards via the Addic7ed.com platform to provide insights into the distribution of NPS. We did so by using data about the downloads of subtitles as a tool to understand the behavior of non-professional subtitle users and assess the assumptions which are present in literature.

The case of House of Cards in Addic7ed.com

Many NPS communities are established according to the language into which its members translate or the content that interests them. However, there are also those that double as producers of subtitles and re-distributors of the subtitles made by other NPS communities. The latter thus have the possibility of reaching larger multilingual audiences. Addic7ed.com is a NPS community that creates and distributes its own subtitles and also operates as a repository and redistributor of subtitles produced by other NPS groups. The subtitles distributed by this group are mostly, but not only, for TV shows and films produced in the United States. Due to its nature, Addic7ed.com represents a research opportunity for analyzing the creation and distribution of subtitles. By exploring the public data it offers, it is possible to know which languages are more relevant for a certain product, how long it takes for communities to create and publish non-professional subtitles and how many people access the subtitles.

In this study, we analyzed the creation and distribution of the subtitles for the series House of Cards (Netflix 2013-Present) in Addic7ed.com. The show revolves around Frank Underwood, a Texan senator who is working his way towards the White House, in close collaboration with his wife, Claire. The couple’s main goal is achieving power and the methods they use to advance towards their goal are mostly unlawful, legally questionable, plainly unethical or morally condemnable. The series’ story draws highly on the US political system and requires the viewership to have certain knowledge of the system, or at least, to be willing to learn more about it. House of Cards and its international success aptly exemplify the discussion about a cultural homogenization debate.

The first season of House of Cards was released on February 1, 2013, and Netflix used the series to launch its own original programming. Starting a new distribution strategy, all the episodes of the first season were released at once. This distribution strategy continues to be Netflix’ brand, not only for the subsequent seasons of House of Cards but also for other original Netflix series. On February 27, 2015, Netflix released the twelve episodes of the third season of House of Cards Since the series was in its third season and enjoys worldwide success, it had already built a strong fan-based community that was expectant and eager to watch the episodes as soon as they were released. At the time, Netflix already operated at a global scale, but it did not have the same penetration it currently enjoys. Netflix expanded to Latin America in 2011, the UK and Ireland in 2012, and the Netherlands in 2013. However, it only launched in Austria, Belgium, France, Germany, Luxembourg, and Switzerland in 2014, and in Australia, New Zealand, Italy, Portugal and Spain in 2015. This creates a complicated issue due to entangled licensing deals for its originally produced content which is pertinent to this article, as will be explained in the Discussion section below.

Methods

One important reason for the lack of studies focusing on the lurkers in the NPS scene is the fact that they are not easy to observe or interview. Lurkers are by far not as actively involved into the community as other users. However, when searching for and downloading subtitles on non-professional subtitle platforms they leave behind digital traces that can be analyzed to understand their behavior.

The data collection took place over two weeks, starting on 27 February 2015, when the third season of the series was released in the US, until 13 March 2015. We used the statistical software package R (R Development Core Team, 2011) to collect data directly from Addic7ed.com through web scraping methods. As shown in Image 1, when a user visits Addic7ed.com, the website offers a list of entries displaying the details of the subtitle files available in every language. We registered all subtitles and the information featured on the website repeatedly over the course of our period of study. More precisely, our scripts performed three tasks every fifteen minutes: (1) downloading the webpage of available subtitles for each episode, (2), automatically extracting information about the subtitles offered exploiting the html structure of the page, and (3) storing the processed data. Our script registered the time and date the operation was carried out, the subtitles available, the language of the respective subtitles, the number of downloads for each set of subtitles, the alias of the person who uploaded or edited the subtitles and the number of times the subtitles were edited in Addic7ed.com.

In total, our data collection registered at least one subtitle during 1234 runs during the period under study. The final data sample consists in a total of 185053 data points. Each data point represents one registered subtitle for a specific episode at a given time point. For each data point we documented the above-mentioned information concerning the individual subtitles. Our dataset identified 180 distinct subtitles for the 13 episodes studied in nine languages. The data was aggregated – e.g. through summarizing the number of downloads by language – in order to facilitate further data analysis. For further information, the obtained data can be retrieved online (Richter & Orrego-Carmona, 2018, August 7)

Furthermore, the obtained data were cleaned and checked for consistency. Our scripts did produce some small amount of damaged data. These inconsistent data points were overwritten either by the value of the preceding data points or by the mean of the values of the neighboring data. Considering the small fraction of damaged data, we refrained from more elaborated procedures of missing value imputation. The information collected allowed us to track the actions of the users in terms of which languages were involved, how long it took for them to create the subtitles and post them online, how the number of downloads progressed and how the demand changes over time.

Results

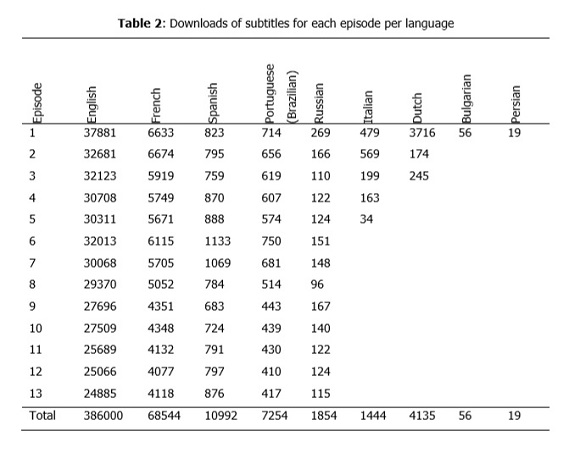

In terms of the types of subtitles offered by Addic7ed.com, the website distributes different types of subtitles: interlingual and intralingual subtitles, as well as regular subtitles and subtitles for the deaf and hard of hearing (SDH). Intralingual subtitles, also known as same-language subtitles, are written in the same language as that of the audiovisual product, while interlingual subtitles refer to the subtitles that are translated from a language into another. The difference between regular subtitles and SDH subtitles is that the latter include descriptions of verbal non-speech elements. Regarding the languages represented, the data collected include subtitles in nine languages: Bulgarian, Dutch, English, French, Italian, Portuguese, Persian, Russian and Spanish.

Regular subtitles

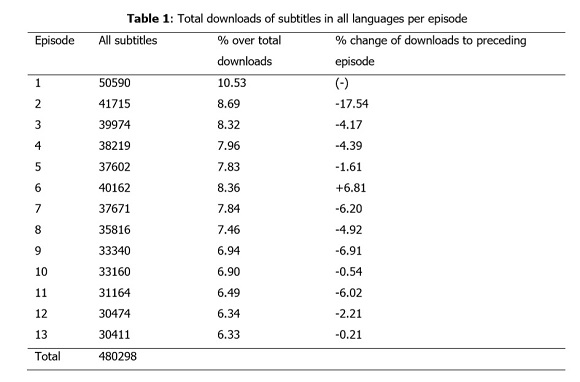

The total number of downloads of subtitles for all episodes and languages was 480298. Table 1 shows the total download figures per episode for all languages at the end of our investigation. The most downloaded subtitles were those for episode one (10.53% of all downloads). After episode one, the total downloads for each episode constantly decrease compared to the figure of the preceding episode, with the exception of episode six.

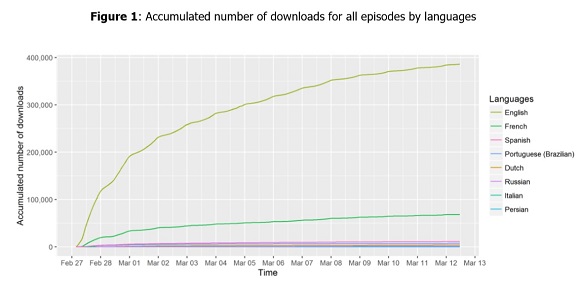

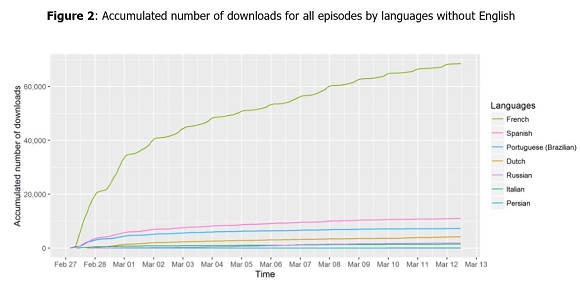

We started running the script on 27 February. The first subtitles were tracked on the website at 3:19:35 [1] CET on 28 February. This first observation included subtitles in English, French, Portuguese and Spanish. At this time, the subtitles in English had already been downloaded 125 times; the subtitles in French, 19 times, and the subtitles in Spanish and Portuguese had 4 downloads each. The teams created and published the subtitles in a progressive order from episode one to episode thirteen. By 28 February at 08:08:51, the subtitles for all thirteen episodes in English, French, Spanish and Portuguese had been published. Figure 1 and Figure 2 show the downloads for all episodes by languages during the time of the study.

The figures for the downloads of the subtitles for each language and episode are shown in Table 2. English is by far the most downloaded language, accounting for 80.37% of the total downloads. The subtitles in English for the first episode are the most downloaded ones, with 37881 total downloads. The number of downloads per episode then steadily decreases and the subtitles in English for episode thirteen are downloaded 24885 times only. This trend seems to be repeated in the number of downloads in French, Spanish, Portuguese and Russian, which are the languages that offer subtitles for all thirteen episodes.

Particularly significant was the fact that this decreasing pattern is interrupted, in all languages in which it is available, by downloads of subtitles for episode six, which shows an increase in relation to downloads for episode five (+6,81%). The fact that episode six is the best-rated episode of the season on IMDB (9.2 while season’s average rating is 8.6 as of 27 October 2016) suggests an effect related to audiovisual content rather than to the subtitles themselves. We elaborate on these results in the discussion.

Subtitles for the deaf and hard of hearing

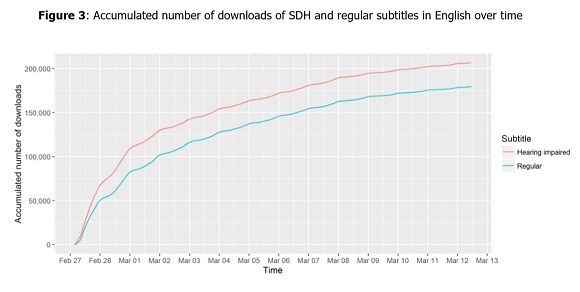

The SDH are marked as such on the website. In our dataset, only the subtitles in English offered an SDH version. The first SDH version was recorded at the same time as the regular English subtitles. In the first observation, the SDH already had 97 downloads while the regular English subtitles had 28 downloads only. Figure 3 shows the evolution of downloads of the SDH and regular subtitles during the data collection period. In total, the SDH of the subtitles in English were downloaded 206454 times, compared to the 179455 downloads of the regular subtitles in English. Considerably more than half of the downloads in English in the dataset correspond to SDH. However, SDH subtitles always appeared at the top of the list of the subtitles. Under the assumption that lurkers did not consciously discriminate between the two subtitles, the higher download rates might be due to a type of a primacy effect. Carney and Banaji (2012) showed that people tend to choose the first of two alternatives when they do not extensively deliberate over their choice. The fact that these downloads still surpass those of the regular subtitles suggests that users might have been satisfied with the SDH. Unfortunately, our data only allow us to guess about the possible reasons for these results. Further investigation would be needed to understand whether this pattern is dependent on conscious decisions made by users.

Temporal perspective

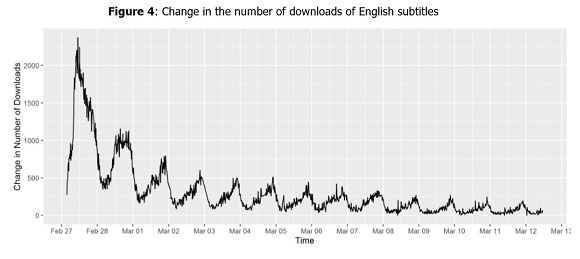

Extending the data collection over a period of two weeks also allowed us to study how the downloads progress over time. Figure 4 shows the change in the number of downloads of the English subtitles over the data collection period. The highest peaks in the downloads occur from 28 February to 3 March. The number of downloads during these four days account for 66.1% of the total downloads, which constitutes the heaviest interaction activity by the users. After the initial high traffic the demand for subtitles slows down, the curve displaying the accumulated number of downloads steadily flattens over time ( Figure 1).

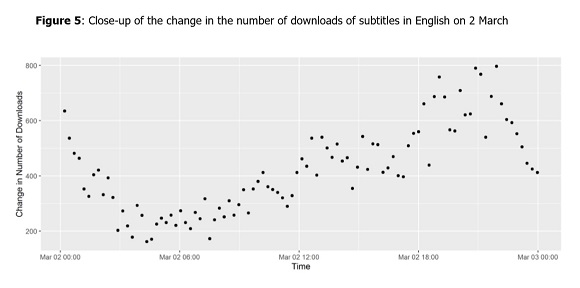

Unfortunately, the collected data do not include geographical information, so it is impossible to pinpoint from where the subtitles were accessed. However, we can observe another pattern in the download progress from 2 March on. Figure 5 shows a close-up of the downloads registered every fifteen minutes on 2 March. We can observe peaks in download numbers in the late afternoon and evening in Europe, hinting that a large number of users being based in Central Europe. If we take the Central European Time as a reference point, there is a daily decline in the number of downloads from midnight until the morning. Then, the number of downloads starts to increase, reaching a peak late in the evening. The same intra-day pattern can be found for the following days of the analysis for English, as well as for the downloads of subtitles in French and Spanish.

Initially, we considered that the date and time on which the subtitles for episode thirteen were downloaded for the first time could serve as a proxy indicator of how long it took the first users to go through all the episodes. This is not the case. The first subtitles for episode thirteen were published at 08:08:51 on 28 February, only five hours after the release of the first subtitles, and downloads were tracked as soon as the subtitles were published. This makes it impossible for anyone to have watched the whole season using the subtitles from Addic7ed.com before downloading the subtitles for episode twelve. It seems that once subtitles become available online, some users hurry to download and store them until they need them; they do not necessarily return to the site each time they watch an episode to download the subtitles for the next one. However, the group of people that decides to download all the subtitles at once is still a minority, since there is a notable general decline in the number of downloads with each episode.

Discussion

To answer the questions proposed above, the following discussion will focus on the relevance of immediacy as an essential aspect in viewers engagement and the languages that are represented in our dataset. Our discussion on originality will focus particularly on the popularity of the intralingual subtitles on the platform as an indicator of a growing interest in becoming close to the original version. Additionally, we discuss the case of episode six as an example viewer engagement in transmedia narrative.

Immediacy

Our first question was related to the idea that non-professional subtitles are popular because they allow users to access the content as soon as it is released. Our data confirm that immediacy continues to be an important motivation behind non-professional subtitle users. The subtitles in French, Spanish and Portuguese for all episodes were uploaded within five hours of the publication of the subtitles in English.

Our results come to emphasize that immediacy is an important factor for the users of subtitles: the first four days of the two weeks under study accounted for 66% of the total downloads. We can assume users were eagerly waiting for the series to come out and use subtitles to watch it shortly after it was made available. The decline after the initial excitement could have different readings. It could simply be that after an initial hype, the community was satisfied. In an interconnected world, it is important for passionate fans to watch their series as soon as possible, particularly in the case of Netflix shows (DeWerth-Pallmeyer, 2016), which release seasons at once and who have motivated the emergence of binge watching (Jenner, 2016). Also, we should consider the possibility that after a couple of days, users turned to their local licensed providers to access the content when it was made available. At the time the third season was released, House of Cards was distributed by local licensed third parties in some countries or regions. In some of these places, the content would be distributed online one or some days after the original release by Netflix in the US.

Netflix model intensifies the audience’s fixation with immediacy and speedy access. Netflix has capitalized the idea of self-scheduling of TV and pushed an idea of global content distribution. In a broader sense, Netflix’ distribution ideas align with the viewers’ disregard of geographical licensing and wishes of accessing audiovisual content as soon as it is released. However, as pointed out above in the case of House of Cards, users cannot simply rely on Netflix. Due to pre-existing licensing agreements, Netflix is not allowed to offer House of Cards in some regions and countries where it operates. For instance, Movistar has exclusive distribution rights for House of Cards in Spain, as do CanalPlus in France and Sky in Germany and Italy. In these areas, even if the viewers are paid subscribers of Netflix, they still must adapt to the local broadcaster’s distribution conditions when they want to access the content. Under these circumstances and within the culture of speed (Catania, 2015), if the audiences can have access to the content using alternative methods, they will do so. NPS makes possible for these audiences to fully rely on these alternative distribution channels to access audiovisual content.

Originality

Interlingual subtitles

During this study, Addic7ed.com offered subtitles in eight languages apart from English: Bulgarian, Dutch, French, Italian, Persian, Portuguese, Spanish, and Russian. However, only four languages had subtitles for all the episodes: French, Spanish, Brazilian Portuguese and Russian. Only subtitles for the first episode were made available in Bulgarian and Persian. In the case of Dutch, the subtitles for the first episode were downloaded 3716 times, which makes them the third most downloaded subtitles for the first episode in the dataset, but the subtitles for the second and third episode were downloaded fewer than 300 times.

NPS communities in Spanish and Brazilian Portuguese have been previously studied (Bold, 2011; Feitosa, 2009; Orrego-Carmona, 2011; Pym et al., 2016) and these seem to enjoy considerable acceptance among the audience. In the case of French, it can be said that up to 4000 people consistently used the subtitles. Although scholars have not mapped the French non-professional subtitle sphere yet, the topic has been featured in newspapers and magazines such as Rue89 (Pouchard, 2010, June 15), Le Monde (Soullier, 2014, April 22), and Le Monde Diplomatique (Bourdaa & Chollet, 2014, April). The presence of Russian is interesting considering that season three of House of Cards relied significantly on the political relation between Washington and Moscow. However, according to the download figures, the subtitles in Russian were downloaded about a hundred times only, indicating a rather small audience.

The figures show a remarkable contrast between French and all the other languages. This might reflect the different roles that Addic7ed.com plays for different language communities. The French subtitles are offered by Addic7ed.com directly (Gerzymisch-Arbogast & Nauert, 2005). That is, these subtitles are internally produced by a community that is maintained by the website. However, communities working into other languages have their own independent websites and might have created and maintained their own followers and users. For these communities, Addic7ed.com works as an additional outlet which might have minor relevance when compared to the main distributors. Such is the case of Italian, for instance. Italy has two traditional and well documented NPS communities, Subsfactory and ItaSA (Barra, 2009; Casarini, 2014; Massidda, 2012). The subtitles that were made available on Addic7ed.com after the release of House of Cards were made by Subsfactory. However, only the subtitles for the first five episodes were posted there and the number of downloads is rather low.

The predominance of intralingual subtitles

The subtitles in English were the most downloaded subtitles by a very large margin. In total, 80.37% of all downloads during the time under study are of subtitles in English. The results come as a surprise since this suggests a viewer profile which is not the user most traditionally portrayed when discussing non-professional subtitles. Judging by this high representation of downloads, we can claim that the website, at least in this case, caters primarily to an audience interested in watching content with intralingual subtitles. Up to now, scholars in Translation Studies see NPS as a primarily interlinguistic activity involving at least two languages. Within NPS studies, intralingual subtitles in English are normally referred to as the source version on which non-professional translators rely to create the translations in their target languages, not as the end product that people will be using. Researchers in audiovisual translation normally address intralingual subtitles in two circumstances only: as SDH (Szarkowska, Krejtz, Krejtz, & Duchowski, 2013) and as a teaching aid in language learning contexts (Kruger, Hefer, & Matthew, 2013). Intralingual subtitles are not normally seen as translations serving entertainment purposes. However, the figures in our dataset show that intralingual subtitles in English are largely used by viewers.

The extended use of intralingual subtitles might indicate that this audience wants to move a step closer to the original, reinforcing the idea that subtitles allow to access a more authentic version of the product. Traditionally, people advocating in favor of subtitling, as well as many non-professional subtitle users, have praised subtitling for providing a less altered version of the translated content, in opposition to dubbing, which replaces the original voices (Casarini, 2014; Feitosa, 2009; Massidda, 2012). The use of intralingual subtitles in English for a TV series such as House of Cards seems to indicate the emergence of a new, more active type of audience, which could be related to what Casarini refers to as viewership 2.0 (2014). According to Casarini (2014), viewership 2.0 tends to follow high-quality shows, consciously decide which shows are worth their time and make “an active effort to follow them with the shortest possible delay after their original broadcast” (2014, p. 60). We know that the preference for subtitling over dubbing in many traditionally dubbing countries is related to the audience’s belief that subtitling gives them the opportunity to have a viewing experience which resembles that of the target audience of the original product (Casarini, 2014; Orrego-Carmona, 2014). For this audience, using interlingual subtitles does not seem to be the best option. To have a more original experience, they want to access the content in its original language version, without the intrusion of another language. The viewers that participate in this new form of viewership are interested in engaging with the audiovisual content in what they consider a more original manner.

Lurkers are not regular, passive users. They invest a battery of resources to access the content they want in their own terms. Thanks to their linguistic knowledge and the technological resources, they have the means to fulfill their expectations of accessing the audiovisual content whenever they want and in the form that they find more suitable to their expectations. The intralingual subtitles are the first ones to be published since they are made readily available by volunteers who use Optical Character Recognition (OCR) software to create the subtitles as soon as the content is released. These viewers do not need to wait for subtitles in their mother tongue since they probably have a certain degree of knowledge of English. The fluctuation in our data led us to assume that most of the users of the website were based in Europe. According to Eurostat (2013), in 2011, 66% of the population aged 25-65 in EU28 stated that they knew English at a fair, good or proficient level. This percentage could be even higher among younger people since the data provided by Eurostat in 2017 shows that in 2015, 83.5% of pupils in primary education in EU-28 and 95.8% of EU-28 students in secondary general education programs study English as a foreign language. Good knowledge of English resulting from the expansion of English as a first, second or foreign language is a worldwide phenomenon, and this does not seem to be a situation restricted to Europe. Although calculating the total number of speakers of a language is difficult due to overlapping estimates or incompatible measuring techniques, Ethnologue [2] estimates the number of speakers of English to be around 942 million, out of which around 603 million speak English as a second or foreign language. The English language has become a global language that is not completely foreign to people in many parts of the world.

Undoubtedly, the circumstances of this new consumption scenario allow viewers to exploit subtitles in different ways. Orrego-Carmona (2015) shows the impact of the democratization of the access to audiovisual content by providing evidence of the viewers’ awareness of these resources and the conscious use they make of them. When engaging with subtitled content, the viewers’ knowledge of the source language allows them to partially or almost completely access the verbal linguistic information available on the soundtrack. For these viewers, subtitles do not act as the primary source of verbal information, subtitles are an additional resource in the communication process that supports the comprehension of the content. As Gottlieb (2005, p. 11) puts it, subtitles “become supplementary in the reception of foreign-language productions”. These active, conscious viewers have taken on an additional challenge when watching content with intralingual subtitles but recognize the limitations of their capacities and use the subtitles to support their viewing process.

Viewer Engagement and Transmediality

The findings in our dataset indicate that episode six had an extraordinary popularity among viewers. The number of downloads for the subtitles of this episode breaks with the steady decline in the number of downloads from an episode to another: the subtitles for episode six were downloaded more often than the subtitles for episode five. In view of this, we can only assume that viewers somehow were prompted by an external factor to go to the website and download the subtitles for this episode. Another piece of the transmedia narrative might be causing the increased engagement with this episode as indicated by the larger number of downloads.

Currently, the experience of following a TV series, particularly for committed viewers, does not simply entail watching the series episodes. In today’s media environment, viewers also become engaged with all the promotion, merchandising, advertising material and user-generated discussion that emerges from the audiovisual content (Proulx & Shepatin, 2012). Users are exposed to teasers, trailers, reviews, comments, memes and other types of content on traditional media (TV channels, newspapers, magazines) and social media outlets. Even before the products are released, these parallel products start feeding the expectation in the consumers which ultimately translates into an emotional investment (Askwith, 2007).

The type of interactive engagement found among lurkers can be understood in terms of the horizontal activities that Jenkins defines as part of the spreadability of content (Jenkins, 2006) in the time of media convergence. Lurkers are interested in accessing the content, they are willing to commit their additional resources to follow the schedule of a foreign country and they purposefully look for the video and subtitle files that are made available online. However, they do not necessarily provide feedback to the producers of the content and take a relatively short period of time to consume the content that is available to them. Their behavior depicts a rather ephemeral, though intensive, engagement with the content.

Although binge watching as such tends to be an individual practice, there exists a subsequent layer of socialization when people share on Facebook, tweet or discuss the content (Jenner, 2016). Given that the data we collected is restricted to the dissemination of the subtitles, our understanding of the circuit of engagement that could be generated in the audiovisual content consumption dynamics is limited. However, within the media convergence, we can interpret the consumption of subtitles produced by non-professionals as a constituent of the enlarged level of engagement of users who not only watch the audiovisual content but also connect with it through other channels and platforms. We can only assume that the increased interest in episode six, which cannot be explained according to the pattern in the data, has been influenced by factors which are not directly related to Addic7ed.com or the subtitles, thus hinting at the type of transmedia experience exposed this group of committed users.

Conclusion

Focusing on the lurkers of the online subtitling community Addic7ed.com, this article explored how the number of downloads of the non-professional subtitles for the third season of Netflix’s House of Cards can be used to learn about the users of non-professional subtitles. To do this, the article traced downloads of subtitles for all the episodes of this season over a period of two weeks to analyze the users’ behaviors in the NPS website Addic7ed.com.

We proposed two research questions to explore the behavior of users in terms of the concepts of originality and immediacy, which are normally associated to NPS. In relation to immediacy, our findings support the idea that NPS is used to consume audiovisual content as soon as it is released. Most of the downloads of the subtitles in all languages occur within the first few days after they are released. The pressure that NPS communities have to publish their subtitles is a response to the needs of an audience with a clear and concrete demand for speedy access. The subtitles are mostly popular right after the content is released. After a couple of days, the demand weakens. If NPS communities are not ready to produce the subtitles quickly, they would probably lose their users. Regarding originality, we found that the subtitles in French and Spanish very popular in the website, which is interesting considering the popularity of dubbing in Spanish and French. However, the most revealing finding was that users of the subtitles have a clear inclination towards using intralingual subtitles. The tendency to access intralingual subtitles might be construed as an attempt to experience the audiovisual content in a more original manner, without the inclusion of an additional language. Our research reveals the profile of the lurkers of NPS as heavily engaged viewers of audiovisual products. They wait eagerly for the products and go through an intense, although short, period of engagement. The NPS scene allows for this type of relationship and the producers of content are clearly willing to respond to these demands.

The demands of the lurkers and the actions of the producers have larger implications for the international media flows and the global media environment. While anime fansubbing used to take a product of a locally bounded market to a larger international audience, thus augmenting its representation and disseminating the embedded cultural aspects, NPS of US TV series essentially reinforces the power of one of the major audiovisual content producing markets that already has the largest share in the television and film export business (Doyle, 2014). Currently, TV series are distributed globally. Still, the US market is setting the tone and people around the world follow the scheduling of US products. Although other regional markets in South America and East Asia have also grown considerably, the US remains the most powerful agent at a global scale (Doyle, 2013). The distribution of US series and films through alternative distribution channels helps in the popularization of these products and increases their impact on the receiving culture. Viewers from non-English speaking countries have become more and more used to accessing audiovisual products through these channels. Now, it seems, they are even watching them with subtitles in the same language. The extended use of intralingual subtitles in English to watch US products in non-English speaking areas should spark an interest in exploring the implications this has for the viewers at societal and cultural levels. The significant reach of US products comes intertwined with an expansion of the English language as an international language and US culture as an example of what life is.

Additionally, the data suggest that the figures of non-professional subtitle downloads could serve as an indicator of different forms of audience engagement. The irregularly high number of downloads for the subtitles of episode six suggests that the consumption of audiovisual content with non-professional subtitles is also influenced by other factors, extrinsic to the subtitles, that might attract the audiences’ attention towards a particular aspect. In that sense, the NPS consumption activities should be understood within a larger framework of consumption that not only involves the audiovisual content per se but also other transmedia elements accessible to consumers.

This project constitutes a first attempt to examine the interaction of consumers on a NPS platform from a quantitative perspective to gain some insights into their behavior. It is important to highlight its exploratory nature. Given that we are drawing on one specific season of one particular series in a specific website, it is not our intention to claim that our findings offer a picture of the entire distribution of non-professional subtitled products. We draw our conclusions from aggregated data, hence we are not able to directly observe individual consumer behavior. However, the data serve to aptly describe a broader picture and highlight trends among the consumers and/or languages. Further studies could assess whether these trends become more stablished, and could also analyze whether the global impact of Netflix’s expansion and their growing offer of subtitled and dubbed content affects piracy and the consumption of NPS.

Translation Studies, in general, has given little attention to the role of reception (Brems & Ramos Pinto, 2013; Chesterman, 2007; Gambier, 2009) and, more specifically, to the role of the reflexive consumers (Pérez-González, 2013). The benefits of the project lay on the quantification of the consumption community and the exploration of the lurkers’ behavior. This study opens an avenue to continue examining the users’ behavior to better understand NPS communities and their impact. In a context in which the users of translations have a prominent role, it is of the essence to understand when and how people are using translations to understand the reach of the phenomenon. Given the impact of lurkers, it is essential for scholars both in Translation Studies and Media Studies to recognize their role in defining new rules of engagement with the audiovisual content which might, in the end, have a direct effect on mainstream media as we know it.

References

Barra, L. (2009). The mediation is the message: Italian regionalization of US TV series as co-creational work. International Journal of Cultural Studies, 12(5), 509–525. https://doi.org/10.1177/1367877909337859 [ Links ]

Bold, B. (2011). The Power of Fan Communities: An Overview of Fansubbing in Brazil. Tradução Em Revista, 11(2), 1–19. https://doi.org/10.17771/PUCRio.TradRev.18881 [ Links ]

Bourdaa, M., & Chollet, M. (2014, April). Sous-titrage en série. Le Monde Diplomatique, p. 27. Retrieved from https://www.monde-diplomatique.fr/2014/04/BOURDAA/50330 [ Links ]

Brems, E., & Ramos Pinto, S. (2013). Reception and Translation. In Y. Gambier & L. van Doorslaer (Eds.), Handbook of Translation Studies (pp. 142–147). Amsterdam and Philadelphia: John Benjamins Publishing Company. https://doi.org/10.1075/hts.4.rec1 [ Links ]

Carney, D. R., & Banaji, M. R. (2012). First is best. PloS One, 7(6), e35088. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0035088 [ Links ]

Casarini, A. (2014). The Perception of American Adolescent Culture Through the Dubbing and Fansubbing of a Selection of US Teen Series from 1990 to 2013 (PhD thesis). Università di Bologna, Forlì, Italy. Retrieved from http://amsdottorato.unibo.it/6672/

Catania, A. (2015). Serial Narrative Exports: US Television Drama in Europe. In R. Pearson & A. N. Smith (Eds.), Storytelling in the Media Convergence Age (pp. 205–220). London: Palgrave Macmillan UK. https://doi.org/10.1057/9781137388155_12 [ Links ]

Chen, J. (2010). Voluntary Virtual Teams' Interaction Styles in Online Communities: an Example of the Subtitle Teams (MA Thesis). National University Chengchi, [ Links ] China.

Chesterman, A. (2007). Bridge concepts in translation sociology. In M. Wolf & A. Fukari (Eds.), Benjamins translation library: v. 74. Constructing a sociology of translation (pp. 171–183). Amsterdam and Philadelphia: John Benjamins Publishing Company. [ Links ]

Cubbison, L. (2005). Anime Fans, DVDs, and the Authentic Text. The Velvet Light Trap, 56(1), 45–57. [ Links ]

DeWerth-Pallmeyer, D. (2016). Assessing the role audience plays in digital broadcasting today and tomorrow. In J. V. Pavlik (Ed.), Electronic media research series. Digital technology and the future of broadcasting: Global perspectives (pp. 143–156). New York: Routledge. [ Links ]

Díaz Cintas, J., & Muñoz Sánchez, P. (2006). Fansubs: Audiovisual Translation in an Amateur Environment. JoSTrans, the Journal of Specialised Translation, 6, 37–52. Retrieved from http://www.jostrans.org/issue06/art_diaz_munoz.php [ Links ]

Doyle, G. (2013). International trade in audiovisual products. In R. Towse & C. Handke (Eds.), Handbook on the digital creative economy (pp. 178–186). Cheltenham: Edward Elgar. [ Links ]

Doyle, G. (2014). Audiovisual Services: International Trade and Cultural Policy. In C. C. Findlay, H. K. Nordås, & G. Pasadilla (Eds.), World Scientific studies in international economics: volume 36. Trade policy in Asia: Higher education and media services (pp. 301–334). Hackensack, NJ: World Scientific.

Dwyer, T. (2012). Fansub Dreaming on ViKi: "Don't Just Watch but Help When You Are Free". The Translator, 18(2), 217–243. https://doi.org/10.1080/13556509.2012.10799509 [ Links ]

Ethnologue. English. Retrieved from https://www.ethnologue.com/language/eng [ Links ]

Eurostat. (2013). Two-thirds of working age adults in the EU28 in 2011 state they know a foreign language. Retrieved from http://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/en/web/products-press-releases/-/3-26092013-AP [ Links ]

Eurostat. (2017). Foreign language learning statistics. Retrieved from http://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php/Foreign_language_learning_statistics [ Links ]

Evans, E. (2011). Transmedia television: Audiences, new media, and daily life. Comedia. New York: Routledge. [ Links ]

Feitosa, M. P. (2009). Legendagem Comercial e Legendagem Pirata: Um Estudo Comparado (Postgraduate thesis). Faculdade de Letras da UFMG, Minas Gerais.

Fernández Costales, A. (2013). Crowdsourcing and collaborative translation: mass phenomena or silent threat to Translation Studies? Hermeneus, 15, 85–110. [ Links ]

Ferrer Simó, M. R. (2005). Fansubs y scanlations: La influencia del aficionado en los criterios profesionales. Puentes, 5, 27–44. Retrieved from http://wpd.ugr.es/~greti/revista-puentes/pub6/04-Maria-Rosario-Ferrer.pdf [ Links ]

Gambier, Y. (2009). Challenges in research on audiovisual translation. In A. Pym & A. Perekrestenko (Eds.), Translation Research Projects 2 (pp. 17–25). Tarragona: Intercultural Studies Group. [ Links ]

Gambier, Y. (2013). The Position of Audiovisual Translation Studies. In C. Millán & F. Bartrina (Eds.), Routledge handbooks in applied linguistics. The Routledge Handbook of Translation Studies (pp. 45–59). London, New York: Routledge. [ Links ]

Gambier, Y. (2014). Changing Landscape in Translation. International Journal of Society, Culture & Language, 2(2), 1–12. [ Links ]

Gerzymisch-Arbogast, H., & Nauert, S. (Eds.) 2005. Challenges of Multidimensional Translation. Retrieved from http://www.euroconferences.info/proceedings/2005_Proceedings/2005_proceedings.html [ Links ]

Gottlieb, H. (2005). Multidimensional Translation: Semantics turned Semiotics. In H. Gerzymisch-Arbogast & S. Nauert (Eds.), Challenges of Multidimensional Translation. [ Links ]

Jenkins, H. (2006). Convergence Culture: Where Old and New Media Collide. New York: New York University Press. [ Links ]

Jenner, M. (2016). Is this TVIV? On Netflix, TVIII and binge-watching. New Media & Society, 18(2), 257–273. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444814541523 [ Links ]

Jiménez-Crespo, M. A. (2017). Crowdsourcing and Online Collaborative Translations. Benjamins translation library: Vol. 131. Amsterdam, Philadelphia: John Benjamins Publishing Company. [ Links ]

Kruger, J.-L., Hefer, E., & Matthew, G. (2013). Measuring the Impact of Subtitles on Cognitive Load: Eye Tracking and Dynamic Audiovisual Texts. In Proceedings of Eye Tracking South Africa (pp. 62–66). [ Links ]

Lee, H.-K. (2009). Between Fan Culture and Copyright Infringement: Manga Scanlation. Media, Culture & Society, 31(6), 1011–1022. https://doi.org/10.1177/0163443709344251 [ Links ]

Leonard, S. (2005). Progress against the law: Anime and fandom, with the key to the globalization of culture. International Journal of Cultural Studies, 8(3), 281–305. https://doi.org/10.1177/1367877905055679 [ Links ]

Luczaj, K., Holy-Luczaj, M., & Cwiek-Rogalska, K. (2014). Fansubbers: The Case of the Czech Republic and Poland. Journal of Comparative Research in Anthropology and Sociology – Compaso, 5(2), 175–198. [ Links ]

Massidda, S. (2012). The Italian Fansubbing Phenomenon (PhD Thesis). Università degli Studi di Sassari, Sassari, [ Links ] Italy.

Nielsen, J. (2006). The 90-9-1 Rule for Participation Inequality in Social Media and Online Communities. Retrieved from http://www.nngroup.com/articles/participation-inequality/ [ Links ]

Nornes, A. M. (1999). For an Abusive Subtitling. Film Quarterly, 52(3), 17–34. [ Links ]

Nornes, A. M. (2007). Cinema Babel: Translating Global Cinema. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press. [ Links ]

O’Hagan, M. (2008). Fan translation networks: An accidental translator training environment? In J. Kearns (Ed.), Continuum Studies in Translation. Translator and Interpreter Training: Issues, Methods and Debates (pp. 158–183). New York: Continuum. [ Links ]

O’Hagan, M. (2013). Understanding fan-translation: pop culture and geeks too cool for translation schools? In S. Bayó Belenguer, E. Ní Chuilleanáin, C. Ó Cuilleanáin, & G. Zuodar (Eds.), Translation Right or Wrong (pp. 230–245). [ Links ]

Olohan, M. (2014). Why Do You Translate? Motivation to Volunteer and TED Translation. Translation Studies, 7(1), 17–33. https://doi.org/10.1080/14781700.2013.781952 [ Links ]

Orrego-Carmona, D. (2011). The Empirical Study of Non-Professional Subtitling: A Descriptive Approach (Master’s minor dissertation). Universitat Rovira i Virgili, Tarragona.

Orrego-Carmona, D. (2014). Subtitling, Video Consumption and Viewers: The Impact of the Young Audience. Translation Spaces, 3, 51–70. https://doi.org/10.1075/ts.3.03orr [ Links ]

Orrego-Carmona, D. (2015). The Reception of (Non)Professional Subtitling (PhD thesis). Universitat Rovira i Virgili, Tarragona, [ Links ] Spain.

Orrego-Carmona, D. (2016). Internal Structures and Workflows in Collaborative Subtitling. In R. Antonini & C. Bucaria (Eds.), Non-professional Interpreting and Translation in the Media (pp. 211–230). Bern: Peter Lang. [ Links ]

Orrego-Carmona, D. (2018). New Audiences, International Distribution, and Translation. In Y. Gambier & E. Di Giovanni (Eds.), Reception Studies and Audiovisual Translation. Amsterdam, Philadelphia: John Benjamins Publishing Company. [ Links ]

Pérez-González, L. (2007). Intervention in New Amateur Subtitling Cultures: A Multimodal Account. Linguistica Antverpiensia, 7, 67–80. [ Links ]

Pérez-González, L. (2010). 'Ad-Hocracies' of Translation Activism in the Blogosphere: A Genealogical Case Study. In M. Baker, M. Olohan, & M. Calzada Pérez (Eds.), Text and Context: Essays on Translation & Interpreting in Honour of Ian Mason (pp. 259–287). Manchester, UK, Kinderhook, NY: St. Jerome Pub.

Pérez-González, L. (2012). Co-Creational Subtitling in the Digital Media: Transformative and Authorial Practices. International Journal of Cultural Studies, 16(1), 3–21. https://doi.org/10.1177/1367877912459145 [ Links ]

Pérez-González, L. (2013). Amateur Subtitling as Immaterial Labour in Digital Media Culture: An Emerging Paradigm of Civic Engagement. Convergence: the International Journal of Research into New Media Technologies, 19(2), 157–175. https://doi.org/10.1177/1354856512466381 [ Links ]

Pouchard, A. (2010, June 15). Le « fansub », sous-titrage illégal des séries télé par passion. Rue89. Retrieved from https://www.nouvelobs.com/rue89/rue89-rue89-culture/20100615.RUE7079/le-fansub-sous-titrage-illegal-des-series-tele-par-passion.html [ Links ]

Proulx, M., & Shepatin, S. (2012). Social TV: How marketers can reach and engage audiences by connecting television to the web, social media, and mobile. Hoboken, N.J.: John Wiley and Sons.

Pym, A., Orrego-Carmona, D., & Torres-Simón, E. (2016). Status and Technology in the Professionalization of Translators: Market Disorder and the Return of Hierarchy. JoSTrans, the Journal of Specialised Translation. (25), 33–53. Retrieved from http://www.jostrans.org/issue25/art_pym.php [ Links ]

R Development Core Team. (2011). R: A Language and Environment for Statistical. Retrieved from http://www.R-project.org/ [ Links ]

Richter, S., & Orrego-Carmona, D. (2018, August 7). Distribution of NPS. Retrieved from osf.io/s7upk [ Links ]

Schneider, P. (2011). Is the 90-9-1 Rule for Online Community Engagement Dead? Socious: Online Community Blog. Retrieved from http://blog.socious.com/bid/40350/Is-the-90-9-1-Rule-for-Online-Community-Engagement-Dead-Data [ Links ]

Schules, D. M. (2012). Anime fansubs: translation and media engagementas ludic practice (PhD Thesis). University of Iowa. Retrieved from http://ir.uiowa.edu/etd/3532/ [ Links ]

Soullier, L. (2014, April 22). Dorothée, passion sous-titres. Le Monde. Retrieved from https://www.lemonde.fr/pixels/article/2014/05/22/dorothee-passion-sous-titres_4412885_4408996.html [ Links ]

Sun, N., Rau, P. P.-L., & Ma, L. (2014). Understanding lurkers in online communities: A literature review. Computers in Human Behavior, 38, 110–117. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2014.05.022 [ Links ]

Szarkowska, A., Krejtz, I., Krejtz, K., & Duchowski, A. T. (2013). Harnessing the potential of eyetracking for media accessibility. In S. Grucza, M. Pluzyczka, & J. Zajac (Eds.), Warschauer Studien Zur Germanistik Und Zur Angewandten Linguistik: Band 6. Translation Studies and Eye-Tracking Analysis (pp. 153–183). [ Links ]

Tapscott, D., & Williams, A. D. (2006). Wikinomics: How Mass Collaboration Changes Everything. New York: Portfolio. [ Links ]

Van Mierlo, T. (2014). The 1% rule in four digital health social networks: an observational study. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 16(2), e33. https://doi.org/10.2196/jmir.2966 [ Links ]

Wilcock, S. (2013). A Comparative Analysis of Fansubbing and Professional DVD Subtitling (Master's thesis). University of Johannesburg, Johannesburg. Retrieved from http://hdl.handle.net/10210/8638 [ Links ]

Yang, X., Li, G., & Huang, S. S. (2016). Perceived Online Community Support, Member Relations, and Commitment: Differences Between Posters and Lurkers. Information & Management, 54(2), 154–165. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.im.2016.05.003 [ Links ]

Note

[1] Given that the data collection was carried out from Barcelona (Spain), all times are expressed in Central European Time.