Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Acessos

Acessos

Links relacionados

-

Similares em

SciELO

Similares em

SciELO

Compartilhar

Observatorio (OBS*)

versão On-line ISSN 1646-5954

OBS* vol.12 no.2 Lisboa jun. 2018

To be or not to be the media industry – Delineation to a fuzzy concept

Marlen Komorowski*, Heritiana Renaud Ranaivoson**

*Imec - SMIT, Studies on Media, Innovation & Technology, Vrije Universiteit Brussel, Belgium

** Imec - SMIT, Studies on Media, Innovation & Technology, Vrije Universiteit Brussel, Belgium

ABSTRACT

Even though media industry studies are on the rise, there is a major issue: the concept itself is “fuzzy”. The goal of this paper is to shed light on the concept. To do so, the paper analyses existing approaches, combining academic references as well as sources commonly used by practitioners (e.g. the OECD, the EU, DCMS). It allows to give three delineations to the media industry: (1) A novel theoretical delineation, (2) a sectoral delineation, and (3) a delineation through the NACE statistical classification system. The main research findings are: (i) the development of a so-called circling model that shows how “mediated content” is at the core of the definition of the media industry; (ii) through the convergence tendencies, many different media activities can play a supporting or facilitating role; (iii) a list of NACE codes to guide statistical analysies.

Keywords: Media industry, Delineation, NACE, Media sectors, Definition

Introduction

The European Commission states that the media industry ‘plays a key economic, social and cultural role in Europe’, which ‘creates growth and jobs’ (European Commission, 2015). 2.5 million people are employed in the media industry in Europe making up 1.5 % of the total employment (Simon & Bogdanowicz, 2012). Additionally, media content has been acknowledged as a key driver for technological development – the uptake of broadband connections, the update of mobile devices, the replacement of video and music players are a consequence of the consumer’s will to access content in new and personalised ways (KEA European Affairs, 2006). Because of media’s apparent influence, academics are more and more interested in studying the media industry. While the field of media industry studies is prospering (Wasko & Meehan, 2013) it also becomes more and more complex. The study fields handling the media industry rank from political economy, cultural studies, communication, to law, business, film and television studies, to name just a few (cf. Havens, Lotz, & Tinic, 2009; Wasko & Meehan, 2013). The label of the media industry has been numerously applied in the scholarly field, but this also made the meaning of this term questionable (Hesmondhalgh, 2010). As an industry is widely acknowledged as a ‘collective word’ for ‘productive institutions, and for their general activities’ (Williams, 1983) it is not so clear what these institutions and their activities related to media are. There is a major issue: the concept of the media industry is still fuzzy.

There are many reasons for this fuzziness. First, the theoretical idea of the media industry is not sufficiently discussed. What is media? Second, the media industry as part of the cultural and creative industries represents a significant set of different sectors that are highly dependent on technological development. These observations make it hard to fully grasp what sectors are part of the media industry and where its boundaries are. For example, is the telecom sector part of the media industry? Should festivals and the live music sectors be included? And third, activity categorisations exist but no guideline is given, which of the codes belong to the media industry and which not. In general, there has been considerable conceptual dissent and debates around the topic (see Part 1 for more details). It is necessary to understand and delineate what the media industry encompasses before universally understandable, comparable research can be undertaken (see Part 2 for more details). The main question of this paper is therefore: How can the media industry be delineated?

The analysis in this paper is built on existing approaches. It relies on an in-depth study of previous institutional and academic analyses of the media industry, through an inductive research process. The insights gained were used to create the novel delineations that are developed by recognizing patterns as differences and similarities among the approaches and their underlying logical arguments are found. Reliability is given as the approaches do cover different geographical scales (from national to international approaches) and different institutions (see below for more details).

Part 1 identifies and discusses the roots of approaches to media industry studies and analyses their strength and weaknesses. Second, in Part 2, a novel delineation of the media industry is introduced at three different levels: (1) A novel theoretical delineation, (2) a sectoral delineation, and, a (3) delineation through a statistical classification system (NACE). In the Final considerations, the implications for future research are discussed.

Part 1: Existing approaches in media industry studies

What is striking when investigating existing approaches to the media industry is the variety of terminologies and scopes. The ‘foundational ideas’ of the media industry emerged as early as the 1920s in ‘critical/scholarly writing’ (Holt & Perren, 2009, p. 1961). These foundations and related concepts include but are not limited by studies on “cultural industries” and “creative industries”, “copyright industries”, “content industries”, “experience economy”, “creative business sector”, “art centric businesses”, “cultural and communication industries”, “mass media” and “knowledge economy”. In this part, the paper will provide a selection of essential concepts related to the media industry and discusses the issues that derive from delineating the media industry.

From culture to content

CULTURAL INDUSTRIES. Haven, Lotz and Tinic (2009) argue that media industry studies have been from its beginnings part of the cultural studies field. Culture constitutes products and services, which is either non-reproducible (a concert, an art fair) or aimed at reproduction, mass-dissemination and export (a book, a film, a sound recording) (KEA European Affairs, 2006). While the term “cultural industry” (in the singular) can be traced back to Horkheimer & Adorno (2002) although then in a derogative way. The term “cultural industries” (in the plural) appeared in the 1970s (KEA European Affairs, 2006). The UNESCO Convention on the Protection and the Promotion of Cultural Expressions defines “cultural industries” as “industries producing and distributing cultural goods or services” with cultural goods and services described as “those activities, goods and services, which at the time they are considered as a specific attribute, use or purpose, embody or convey cultural expressions, irrespective of the commercial value they may have” (2005 Article 4). 148 countries agreed on the content of the Convention (KEA European Affairs, 2006). Obviously, the media industry produces cultural goods. However, the approach of cultural industries leads towards a much broader interpretation of the media industry.

CREATIVE INDUSTRIES. The concept of “creative industries” has been described by some scholars as concept that emerged out of media industry studies (Wasko & Meehan, 2013). The term defines industries on the basis of types of inputs and generative processes that characterize their creation (Nielsén & Power, 2011). The idea of creative industries emphasises the significance of creativity, such as artistic, scientific and economical creativity (United Nations & Bureau de Liaison Bruxelles-Europe, 2010). The emphasis on creative inputs and processes can be interpreted as even wider in scope than cultural outputs as in “cultural industries” and the media industry. However, the Lisbon Treaty recognizes culture being crucially related to, as well as being an essential catalyst for, creativity. It is difficult to locate the origin of the concept of “creative industries”. It is thought to have emerged in Australia in the early 1990s. In Europe, the terminology “creative industries” is attributed to the UK, when in the late 1990s the first Blair administration set up its Creative Industries Task Force to outline the promotion of creative industries as economic drivers. The concept was formalised in the central government Department for Culture, Media and Sport (DCMS) (KEA European Affairs, 2006). Also the European Cluster Observatory (2011) adapted the approach of the creative industries defining them as activities “drawing on advertising, architecture, art, crafts, design, fashion, film, music, performing arts, publishing, R&D, software, toys and games, TV and radio, and video games.”

COPYRIGHT INDUSTRIES. Much closer to the media industry is the idea of the “copyright industries”. They are defined by intellectual property and in particular intellectual property subject to copyright (United Nations & Bureau de Liaison Bruxelles-Europe, 2010). Copyright is one of the main branches of intellectual property and applies to “every production in the literary, scientific and artistic domain, whatever may be the mode or form of its expression” (Article 2 Berne convention for the protection of literary and artistic works, 1967). A distinction is made between industries that actually produce the intellectual property, those that are necessary to transfer the goods and services to the consumer and “partial” copyright industries where intellectual property is only a minor part of their operation (United Nations & Bureau de Liaison Bruxelles-Europe, 2010). However, literary and artistic works are defined as outputs based on original work of authorship and include books, music, plays, choreography, photography, films, paintings, sculptures, computer programs and databases (World Intellectual Property Organization WIPO, 2015).

CONTENT INDUSTRIES. The OECD has developed one of the first definitions of what “media and content industries” (MCI) entails: “The production (goods and services) of a candidate industry must primarily be intended to inform, educate and/or entertain humans through mass communication media” and “these industries are engaged in the production, publishing and/or the distribution of content (information, cultural and entertainment products), where content corresponds to an organized message intended for human beings” (OECD, 2011). The interest in the “content industry” originated with the rapid transformation and diffusion of ICT as these would have a significant impact on industries that create and distribute content (e.g. text, audio, video) (OECD, 2011). The OECD has therefore developed the concept of the “information economy” as a combination of the ICT sector and the content sector (OECD, 2011). Consequently, the “content sector” consists of industries, which produce “information content products” while the “electronic content sector” (like digital goods) is a subset of the “content sector”. Also the European Commission adopted the approach of the “media and content industries” (MCI) referring to the definitions of the OECD in their JRC Scientific and Policy Report (Leurdijk et al., 2012). Within this report the MCI covers “the book, broadcasting, cinema, music, newspapers, and video games industries” (Leurdijk et al., 2012).

Issues in delineating the media industry

The above-described approaches that are connected to the media industry show how complex the term can be perceived. Nonetheless, all approaches have their legitimation when trying to find a delineation of the media industry as studies in the field are highly linked to these foundational ideas. Public institutions so far have not installed a widely-acknowledged delineation of the media industry as it is the case for the more expanded approaches of the “creative or cultural industries”.

Firstly, the existing approaches introduced above encompassed a purely theoretical description of how to delineate an industry. For instance, the “creative industry”-approach, which is widely adopted, especially concentrates on the creational process. The “cultural industry”-approach focuses on the value of the product. The “copyright”-concept emphasises a specific characteristic of the product in a similar way as the “content industry”-approach. However, it can be easily shown that not all kind of creative production leads to media content and not all kind of cultural, copyright and content products necessarily belong to the media industry. The approaches highlighted certain activities in their theoretical delineations. For instance, the OECD highlights that the “media and content industries” are engaged in the production, publishing and distribution of content. The “copyright industries” particularly focus on the production similar to the “creative industries” approach. However, it can be questioned if not also other activities are part of the media industry, like retail.

Secondly, the before introduced approaches highlight certain sectors or focus on actual products. The European Cluster Observatory focuses in their analysis of the “creative industries” on advertising, architecture, art, crafts, design, fashion, film, music, etc. The WIPO highlights the sectors that produce books, music, plays, choreography, photography, films, among others. But also within one chosen approach the subsectors can diversify. For instance, the LEG group of the European Commissions started their delineation of the “cultural industries” by adapting the UNESCO definition but departed significantly from it as sport, environment, and games were excluded and new areas such as architecture were introduced. However, it needs to be kept in mind that the media industry is undergoing remarkable structural changes caused by technological, economic and social transformations, while the convergence opened up the definition of the traditional media sector (Krätke, 2003). Driven by these changes, entirely new sectors and products have emerged within the media industry, making it difficult to frame the concept (e.g. computer games, web design, mobile apps) (Nielsén & Power, 2011).

Thirdly, besides theoretical and sectoral delineations, more practical approaches have been established in the above-described approaches. For instance, UNESCO developed its Framework for Culture Statistics (FCS) already in 1986 (UNESCO, 2009). It consists of a classification of categories to be considered when producing cultural statistics. Also in the EU, from 1995 onwards the awareness of the lack of cultural statistics was raised, with the results that the Leadership Group on Cultural Statistics (LEG-Culture) was consequently set up in 1997. It conducted a three year-project aimed at determining a common definition, suggesting changes in statistical classification, reviewing existing data collections and producing indicators to enable assessment (KEA European Affairs, 2006). However, for the media industry, such an acknowledged classification for statistical purposes does not exist yet.

Extensive literature already debates cultural and creative industries (Caves, 2000; Galloway & Dunlop, 2007; Miller, 2016), cultural economy and industries (Hesmondhalgh, 2013; Power & Scott, 2004; Pratt & Jeffcutt, 2009; Scott, 2000) or media industries and economics (Doyle, 2013; Havens et al., 2009; Holt & Perren, 2009). But, still no acknowledged delineation for the media industry exists.

Part 2: A novel delineation of the media industry

This section proposes a novel delineation of the media industry. The analysis of the existing approaches and their respective strengths and weaknesses shows they are following a similar logic of delineation (see Part 1). These approaches have been translated into three different angles: the media industry will be delineated (1) conceptually, (2) through sector distinctions and (3) through existing classification systems. Still, this paper acknowledges that the delineation of the media industry is a matter of professional judgement. Additionally, the delineation of the media industry requires taking the above-described issues into account. The following requirements have been built based on the identified weaknesses. Therefore, the delineation of the media industry should (i) consider the main approaches existing; (ii) encompass the complicated features of media goods and services; (iii) be flexible to overcome limits that might be encountered; (iv) be simultaneously straight forward to be scrutinized through defining integrated and excluded aspects; (v) consider besides traditional media sectors also converging trends caused by the ICT development in the media.

A theoretical delineation

A theoretical delineation of the media industry means to find conceptually a way to describe the very essence of what the media industry is. As has been discussed above, existing approaches do not sufficiently describe the media industry as the concepts miss certain aspects and activities that should be included or excluded. We propose to delineate the media industry by its outcome; i.e. mediated content. The media industry is determined by mediated content for mass distribution. This delineation is essentially following the idea of the OECD and its definition of the “media and content industries” as described above. However, the distinction is that mediated content gives a much clearer idea of what kind of content is meant. It includes all outputs that are distributed through a carrying media, like paper, the TV, the Internet, etc. These mediated contents can be traditional (for example a book, a film, a sound record) or not, as the Internet has made new, dematerialised content possible (for example video games, mobile applications). However, the medium used for the content should enable the distribution to a large group of consumers. This mediated content can embody values of culture, creativity, education, information or simply be entertaining. This has explicit consequences in what kind of products are included in the industry (see below for more information). The core role of mediated content should not be confused with mediatization, a concept used to analyze critically the interrelation between changes in media and communications on the one hand, and changes in culture and society on the other (Couldry Nick & Hepp Andreas, 2013). In this paper, we remain focused on media industry, with a view to better understand and delineate them, and assessing its impact on the rest of society is outside of our scope.

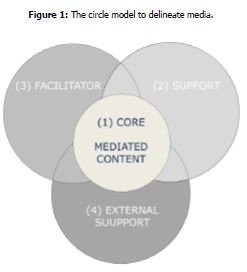

While the OECD only focuses on certain activities of the “media and content industries” including production, publishing and distribution of content, we acknowledge that there are more activities that are essential for the theoretical dimension of the media industry. We therefore suggest to use an industrial systems approach inspired by the work of Porter (1990) to delineate the media industry, which means that all kind of activities need to be integrated that add value to the mediated content. We propose to present activities in the media industry through a circling model (see Figure 1). This model centres around the main idea of “mediated content” as the starting point of the definition is production and publishing, and circles outwards as those ideas become combined with more and more other activities necessary to grasp the whole process of bringing mediated content to the consumer. The circling process enables identifying the different categories of activities and entities (actors) covered by the media industry. This paper distinguishes hereby four different categories1:

- Core entities: actors that directly contribute to the production and publishing of mediated content consumed/used by the final consumer.

- Supporting entities: actors that either indirectly contribute to the production and publishing of the mediated content, or actors who play a supporting role in the process.

- Facilitators and peripheral entities: supporting actors that are not directly involved in the process of production, in the narrow sense, but do actually play relevant roles, such as for valorisation, support, professionalization, etc. (like universities, other public institutions, etc.).

- External entities from other sectors: actors that belong to another sector in a strict sense, but which have a direct or indirect effect on the process, and are included for the sake of completeness (for instance telecommunication companies and artistic creation

Each circle overlaps as entities of the media industry could be active in not only one but several circle’s activities. Also, entities can be part of the media industry while also being part of other industries. For instance, not all IT activities are included in the definition. Even though the car industry features IT activities, only those IT activities are considered as part of the media industry, which support the publishing and production of mediated content, like certain app developers. In our view, the circling process is more inclusive and provides a truer illustration of the media industry and its activities compared to existing approaches.

A sectoral delineation

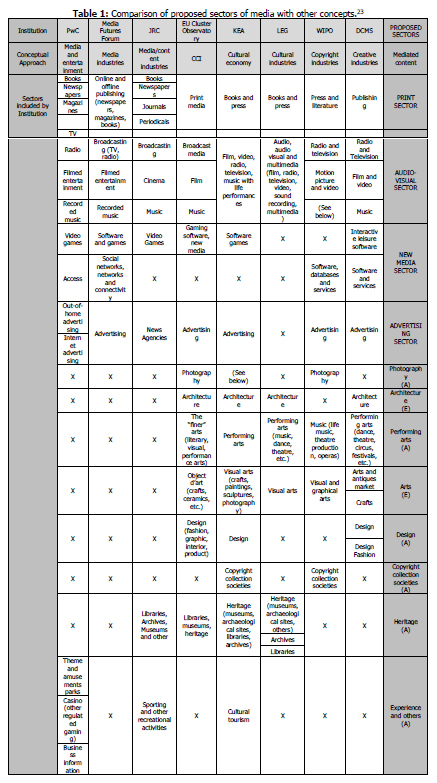

A sectoral delineation of the media industry provides a clear distinction into certain sectors that are part of the industry. There are many debates in what kind of sectors to include or exclude from the media industry and no consensus has been found so far. Additionally, existing approaches as described above do not sufficiently delineate the different sectors of the media industry. Therefore, the so-called “borderline” sectors need further investigation and included and excluded sectors need to be identified. This was here built on the findings of the previous conceptual delineation of the media industry and the circle model is considered. Additionally, for a clear comparison, a comprehensive review of the approaches of leading institutions working on media related topics was carried out. At an international level, the works of PwC (2015) and WIPO (2015) were investigated as well as, at the European level, the different approaches of the European Commission based on their work on the EU Media Futures Forum (2012), the Joint Research Centre (JRC) (Leurdijk et al., 2012), the European Cluster Observatory (Nielsén & Power, 2011) and Eurostat’s LEG Task Force (LEG Eurostat, 2000). Also analysed was the work of UK’s DCMS (2001) representing the national level. Table 123 gives an overview of the comparison of existing approaches and our proposed delineation of the media industry into sectors.

The first two lines, list respectively the institution and the conceptual approach it has developed. The lines under list the sectors identified by each approach. Thus, Table 1 shows that a large number of sectors were recurrent in the different approaches to the media industry. Additionally, different institutions grouped sectors while others distinguished them into several. For instance, the EU Cluster Observatory includes the sector of “print media” while the JRC specifically differentiates between “books”, “newspapers”, “journals” and “periodicals”. Further, it can be observed that besides differences in sectors included also differences in terminologies occurred, for example PwC talks about “video games” while DCMS defines them as “interactive leisure software”.

Besides these differences it can be observed that the approaches of media and content as adapted by PwC, the Media Futures Forum and the JRC include less sectors but differentiate them further. Approaches of cultural, creative and copyright industries as adapted by the other institutions scope unsurprisingly much more sectors. The media industry is seen as part of the cultural and creative sector, which explains this occurrence.

Sectors that have been included in the here-proposed delineation are built on the existing concepts presented in Table 1. As mediated content has been the delineating conceptual factor of the media industry (see above) the following delineation into four broad sectors (see column on the far right) is suggested: (1) print, (2) audio-visual, (3) new media, and (4) advertising sector. These sectors have been chosen in order to enable the delineation to be flexible concerning defining the respective sector-scope. The print sector for instance has been chosen as a core sector and not one of the sub-sectors characterised by its products such as books, newspapers, and magazines. This “built-in” flexibility allows the addition of novel products in the future, like comics and other formats.

It is also important to understand that the four chosen sectors are not perfectly mutually exclusive. There is a permeable border between them as dynamics can occur along several sectors. For instance, the new media sector is highly interlinked with the audio-visual sector as numerous mobile applications feature or handle audio-visual content. The convergence of the media industry and the upsurge of the Internet as the main media consumption medium make this necessary. Still, we argue that such a distinction is helpful when the media industry is delineated as this allows a comparative view.

As the central concept is mediated content, many sectors that have been taken into account by other institutions are excluded in our approach. Nonetheless, these sectors can still be considered to play a facilitating or external function (see circle model in Figure 1). Consequently, they are marked as “associated” (A). “Associated,” means in this context to cover mostly the most outer circle of the circle model as. However, there are also possibilities to include them into more inner circles. For example:

- While KEA combines music and life music events like concerts, this is to be excluded for the audio-visual sector here, as live music is not carried by a medium. The recording of a concert however is carried by a medium and would then be integrated in the core. The same goes for sport events and other life entertainment. This is also possible for casinos, where poker tournaments have become a TV format.

- Another example is the telecommunication sector, which is used in many approaches. Telecom operators produce some of the most visited news websites today and would be therefore core. However, the main activity is only to be understood as distribution of digital content.

- Photography is an integral part of journalism and therefore within the content production of the print sector. However, not the whole photography sector should be included, as many photography activities are not directed towards producing mediated content for mass distribution but for private consumption.

- Design is not included. Although web designers could play an important role in the new media sector, not all designers should be included. Fashion designers for instance are producing products that can be mass distributed. Still, clothes are manufactured products and not mediated content.

- Copyright collection societies are associated as they are enabling the monetization of many mediated content products.

- Libraries and archives are distributors of printed media and audio-visual media. However, not all are active in that area. Still, interrelations with the media industry could be observed and therefore are considered as they have been marked as “associated”.

It should be noted that even though some sectors have been excluded (E) such as architecture, crafts and the heritage sector, all these sectors are acknowledged as important cultural and creative assets for media and can therefore play an external role. Looking at the media industry also means to look at the environment, in which the production and distribution of mediated content takes place and these cultural and creative sectors can have an important influence on the social and economic environment. In conclusion, we propose the delineation of the media industry into four core sectors: audio-visual, print, advertising and new media. This distinction is helpful to understand the main activities in the industry while at the same time they are flexible enough to acknowledge the converging trends in the media industry.

A delineation through classification system (NACE)

Traditionally, industrial sectors are defined using statistical nomenclatures. This is done in order to make statistical analysis possible. Nomenclatures divide activities of the economy into sectors and then differentiate these into more specific activities. The statistical classification of economic activities in the European Community, abbreviated as NACE, is the classification used in the European Union (Eurostat, 2015).4 The NACE classification is important in research, when data on media institutions needs to be extracted from national sources but also Eurostat databases. For the sake of precision, this paper concentrates on NACE codes at the four-digit level, which gives a great level of detail for economic activities.

The process of defining the NACE codes of the media industry has been two-fold. First, existing delineations of public organisations and scholars have been investigated and strengths as well as weaknesses analysed. Second, the delineation of the media industry, as developed above, has been used to include or exclude codes used by other institutions and additional codes to include have been screened. In cases where the delineation of codes was not clear beyond doubt, official definitions were consulted and samples of institutions that are identified by the NACE code in question investigated to enable a definite decision.

The NACE codes have been grouped into the circles or categories of activities in the media industry that have been identified above. These categories have been complemented with additional sub-categories that were identified through screening of included codes. The sub-categories are not claiming to show the whole range of activities possible in the media industry as they only show possible groupings through the NACE code. However, it is deemed necessary to understand all activities in more detail.

Additionally, the chosen NACE codes have been grouped into the four core sectors of the media industry identified above. The convergence of the media industry makes this distinction quite complex as the capabilities of the NACE system are a limiting factor with regards to categorisation attempts such as the one undertaken in this paper. In case of doubt, NACE codes were mostly classified as “comprehensive” (in Tables in Appendix as COMP) because of the convergence trends taking place in the sector. If possible, NACE codes were classified within a certain sector based on where the activities perform traditionally in (for example are the broadcasters distributing content online but are considered as part of the audio-visual sector). The identified sub-categories that were depicted from the circle model (Figure 1) are as follows:

Besides the groupings into the activity categories, sub-categories and four media sectors, it was possible to delineate NACE codes through a comprehensive review of codes adopted by existing approaches of organizations and scholars. At an international level, the approach of the OECD towards the information economy and media and content industries (OECD, 2011), at an European level Boix et al. (2015) and the approach towards creative and cultural industries (CCI) of the European Cluster Observatory (Nielsén & Power, 2011) and KEA’s delineation of the cultural economy (KEA European Affairs, 2006); as well as on a national level, UK’s creative industries classification by the DCSM (DCMS, 2001) and Belgium’s IdeaConsult report on media clusters (Verheyen & Pierre-Alain, 2012) were investigated.5

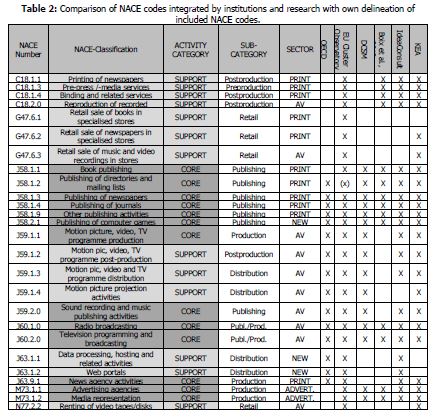

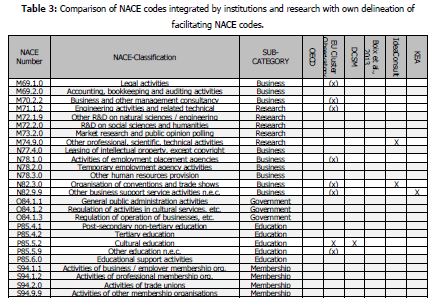

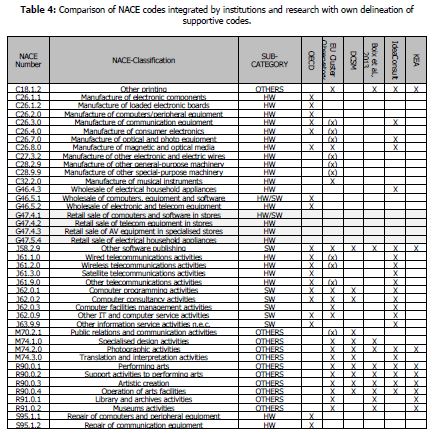

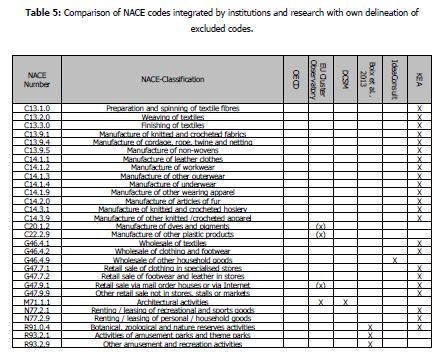

Table 2 provides a sum of the analysis. For each NACE code the name is given, then the activity category and sub-category, the corresponding sector (cf. Table 1) and for each investigated approach whether the NACE code is taken into account. Tables 3, 4 and 5 follow roughly the same approach, applied to respectively facilitated, supportive and excluded codes.

Firstly, the review shows that several NACE codes could be unerringly identified as core and supporting activities (see Table 2 for included core and supporting codes). These codes can be acknowledged through different means: (a) they have been included by all or most other approaches investigated (cf. J58, J59, J60); (b) they have in their description a “mediated content” product included, like a book, newspaper or television programme (cf. C18.1.1, G47.6.1); (c) they have in their description the identified activity categories or sub-categories included, like publishing, production or distribution (cf. J58.1.9, J59.2.0); and (d) can be clearly differentiated into the four sectors, print, audio-visual, new media and advertising. The core and support NACE codes are the primary focus when analysing the media industry, which means that all institutions identified through the codes are part of the media industry as here delineated.

Second, the review revealed that the investigated approaches do not account for additional institutions that have a facilitating character. However, we have decided to depict the media industry through the approach of “institutional thickness” (see Table 3). Amin and Thrift (1995) describe that a strong institutional presence is depicted of a plethora of diverse institutions, which is one of the key elements6 for “institutional thickness”. These institutions are for instance employment organizations (cf. N78), chambers of commerce, trade associations and other business associations (cf. S94), local authorities (cf. O84), financial and legal institutions (cf. M69) and research and innovation centres (cf. M72, P85). These institutions are integrated as facilitators because of the importance these institutions play in the media industry. However, the codes cannot be purely identified as media-related. Therefore, not all entities of these codes are to be included.

Third, the review illustrated that the investigated organisations have different approaches on whether to include ICT and culturally relevant NACE codes. As mediated content is the core, we have indicated that the codes in question do not belong to the media industry. However, these activities could play a supportive role and have therefore been integrated as external activities (see Table 4). The codes included are related to manufacturing of ICT products (cf. C26), telecom and other ICT related activities (cf. J62). No organization chose retail (cf. G46). Cultural activities rank from design (cf. M74) to performing arts (cf. R90). These codes can hardly be related to the media industry. However, especially the ICT and telecom sectors are important in this context.

Fourth, the review of the delineations of other organisations and scholars showed that the scope of the analysis influences the chosen NACE codes. This led to the exclusion of several NACE codes that have been integrated in other studies (see Table 5 for excluded NACE codes). The fashion industry for example (cf. C13, C14, G46, G47) is seen by KEA as part of the cultural economy. Additionally, KEA and Boix et al. (2015) have chosen to include other cultural activities that relate to life entertainment (cf. N77, R91, R93). Both are not identifiable as mediated content. The European Cluster Observatory has chosen a very broad approach7 to CCI and included codes like “manufacture of dyes and pigments”. These types of excessively broad codes have been excluded as well (cf. C20, C22). Typical cultural and creative products and activities in particular are often not part of the media industry when identified as “mediated content” industry. This led to the exclusion of activities related to fashion, architecture and live entertainment. This decision is also supported by the investigated organisations, as only one organisation at most included these codes. Additionally, many codes were excluded in the first place, as there is no relation to media at all (e.g. A-Agriculture, forestry and fishing).

The delineation of NACE codes to include for delineating the media industry has shown many obstacles. However, the choice of NACE codes can enable data collection from an economical point of view to analyse the media industry and is therefore important when delineating the concept in a practical process. This macro approach is exogenous. However, the here-chosen NACE codes are not to be seen as fixed activities. Here excluded NACE codes could still in later research and in practice be found as relevant. Additionally, the delineation of media through NACE codes and further grouping into sectors allow considerations that go beyond the description of activities towards a network of interactions between institutions.

Final considerations

We have shown that, even though the media industry is already a highly important topic in academia, the concept of the media industry is itself still quite “fuzzy”. There is no consensus among scholars concerning what to include into the media industry and what to exclude when bringing media into their agendas. The reasons for this lack in unanimity are manifold. Especially the influence that technological changes have on the media industry makes it hard to delineate new rising sectors that are part of many other concepts, e.g. the “creative industry” and “cultural industry”. This is troublesome because in order to research the media industry, it is of the utmost importance to know how to delineate it.

The goal of this paper was to shed light on the concept of the media industry by proposing three different ways: (1) a theoretical delineation, (2) a sectoral delineation and (3) a delineation through NACE. To achieve this goal, existing approaches by leading public and private institutions, such as the OECD, the European Union, PwC and scholars were analysed.

The research demonstrated that what distinguishes the media industry from other concepts is the theoretical core of the “mediated content”. We have also shown that through the convergence of the media industry many other sectors and activities can now be considered part of the same industry. Therefore, the circling model was developed to show how the core of the media industry can be influenced by supporting, facilitating and external activities. The circling model can be used as a guide to make the real borders of the media industry more tangible.

In addition to the circling model, this paper claims that when delineating the media industry the definition of sectors to include and exclude is necessary. The audio-visual, advertising, print and new media sectors have been clearly identified as part of the media industry. On the other hand, this paper highlights the limits of this approach. There is a clear indication of the existence of associated sectors which do not belong to the core sectors but which should still be considered important.

Besides, this paper proposed a list of NACE codes that belong to the media industry and can guide statistical analyses. The analysis shows that a group of NACE codes could be clearly identified as belonging directly to the media industry, while others should be seen as supportive or facilitating.

In conclusion, we have found that researchers should be aware of the hurdles that occur when delineating the media industry. It should be always kept in mind, that there is no clear delineation so far and when the word “media industry” is used it can mean something different from person to person and publication to publication. The main outcome of the here-proposed delineation is to provide first insights into streamlining future research on the media industry. It should be noted however that even if the delineation of the paper is followed, discrepancies between the reality of media and the delineation could still be prevalent.

References

Amin, A., & Thrift, N. (1995). Globalization, institutions, and regional development in Europe. Oxford University Press. Retrieved from http://EconPapers.repec.org/RePEc:oxp:obooks:9780198289166 [ Links ]

Berne convention for the protection of literary and artistic works. (1967) (Revised at Stockholm on July 14, 1967). Geneva: United International Bureaux for the Protection of Intellectual Property.

Boix, R., Hervás‐Oliver, J. L., & Miguel‐Molina, D. (2015). Micro‐geographies of creative industries clusters in Europe: From hot spots to assemblages. Papers in Regional Science, 94(4), 753–772. https://doi.org/10. 1111/pirs.12094

Caves, R. E. (2000). Creative industries: Contracts between art and commerce. Cambridge, Massachusetts, and London, England: Harvard University Press. [ Links ]

Couldry Nick, & Hepp Andreas. (2013). Conceptualizing Mediatization: Contexts, Traditions, Arguments. Communication Theory, 23(3), 191–202. https://doi.org/10.1111/comt.12019

DCMS. (2001). Creative industries mapping document 2001. London: Department for Culture, Media & Sport. [ Links ]

Doyle, G. (2013). Understanding media economics (2nd ed.). Los Angeles, London, New Delhi, Singapore, Washington, DC: SAGE Publications Limited.

EU Media Futures Forum. (2012). Fast-forward Europe - 8 solutions to thrive in the digital world. Retrieved from http://ec.europa.eu/digital-agenda/sites/digital-agenda/files/forum_final_report_en.pdf [ Links ]

European Commission. (2015, July 22). Media Policies - Digital Economy & Society. Retrieved 18 August 2016, from https://ec.europa.eu/digital-single-market/en/media-policies [ Links ]

Eurostat. (2015, August 14). Glossary:Statistical classification of economic activities in the European Community (NACE) [Encyclopedia]. Retrieved 1 October 2015, from http://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php/Glossary:Statistical_classification_of_economic_activities_in_the_European_Community_%28NACE%29 [ Links ]

Galloway, S., & Dunlop, S. (2007). A critique of definitions of the cultural and creative industries in public policy. International Journal of Cultural Policy, 13(1), 17–31.

Guitte, A., Schramme, A., & Vandenbempt, K. (2010). Creatieve industrieën in Vlaanderen anno 2010: een voorstudie. Antwerp: Flanders DC - Antwerp Management School. Retrieved from http://www.antwerpmanagementschool.be/media/296192/FDC_voorstudie_Creatieve %20industrieën%20in%20Vlaanderen.pdf [ Links ]

Havens, T., Lotz, A. D., & Tinic, S. (2009). Critical media industry studies: A research approach. Communication, Culture & Critique, 2(2), 234–253.

Hesmondhalgh, D. (2010). Media industry studies, media production studies. Media and Society, 145–163.

Hesmondhalgh, D. (2013). The Cultural Industries. London: SAGE Publications. [ Links ]

Holt, J., & Perren, A. (2009). Media industries: history, theory, and method (1st ed.). Chichester, West Sussex: John Wiley & Sons. [ Links ]

Horkheimer, M., & Adorno, T. W. (2002). Dialectic of Enlightenment. Philosophical Fragments (Edited by Gunzelin Schmid Noerr). Standford, CA: Stanford University Press.

KEA European Affairs. (2006). The Economy of Culture in Europe (Study prepared for the European Commission). Retrieved from http://ec.europa.eu/culture/library/studies/cultural-economy_en.pdf

Krätke, S. (2003). Global media cities in a world-wide urban network. European Planning Studies, 11(6), 605–628.

LEG Eurostat. (2000). Cultural statistics in the EU - Final report of the LEG (Eurostat Working Paper). Luxembourg: Eurostat. [ Links ]

Leurdijk, A., De Munck, S., Van den Broek, T., Van der Plas, A., Manhanden, W., & Rietveld, E. (2012). Statistical, Ecosystems and Competitiveness Analysis of the Media and Content Industries: A Quantitative Overview (JRC Technical Reports). Luxembourg: European Commission. Retrieved from http://ftp.jrc.es/EURdoc/JRC69435.pdf [ Links ]

Miller, T. (2016). The New International Division of Cultural Labor Revisited. Icono 14, 14(2), 26–55. https://doi.org/10.7195/ ri14.v14i1.992

Nielsén, T., & Power, D. (2011). Priority sector report: creative and cultural industries (European Commission: The European Cluster Observatory). Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union. Retrieved from http://ec.europa.eu/DocsRoom/documents/615/attachments/1/translations/en/renditions/pdf [ Links ]

OECD. (2011). OECD Guide to Measuring the Information Society 2011. Paris: OECD Publishing. Retrieved from http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/10.1787/9789264113541-en [ Links ]

Porter, M. E. (1990). The competitive advantage of nations. Harvard Business Review, 68(2), 73–93.

Power, D., & Nielsén, T. (2011). Priority Sector Report: Creative and Cultural Industries. European Cluster Observatory. Retrieved from https://www.google.be/url?sa=t&rct=j&q=&esrc=s&source=web&cd=1&ved=0CB8QFjAAahUKEwiQqPTZ2a7IAhWCRxoKHUkYCYw&url=http%3A%2F%2Fec.europa.eu%2Fenterprise%2Fnewsroom%2Fcf%2F_getdocument.cfm%3Fdoc_id%3D7070&usg=AFQjCNGhAVnSI6AfcBIvUqXwOL4ObQsiaQ&sig2=2pW4yodD5coZsISi_O0DxQ&cad=rja

Power, D., & Scott, A. J. (2004). Cultural industries and the production of culture. London, New York: Routledge. [ Links ]

Pratt, A. C., & Jeffcutt, P. (2009). Creativity, innovation and the cultural economy. London, New York: Routledge. [ Links ]

PricewaterhouseCoopers. (2015). Global entertainment and media outlook 2015-2019. Retrieved from http://www.pwc.com/gx/en/industries/entertainment-media/outlook.html [ Links ]

Scott, A. J. (2000). The cultural economy of cities: essays on the geography of image-producing industries. London, Thousand Oaks, New Delhi: Sage. [ Links ]

Simon, J. P., & Bogdanowicz, M. (2012). The Digital Shift in the Media and Content Industries: Policy Brief (Report EUR 25692 EN) (p. 20). Institute for Prospective and Technological Studies, Joint Research Centre. Retrieved from http://publications.jrc.ec.europa.eu/repository/bitstream/JRC77932/jrc77932.pdf [ Links ]

UNESCO. (2009). THE 2009 UNESCO FRAMEWORK FOR CULTURAL STATISTICS (FCS). Montreal, Canada. Retrieved from http://www.uis.unesco.org/culture/Documents/framework-cultural-statistics-culture-2009-en.pdf [ Links ]

United Nations. (2005). Convention on the Protection and Promotion of the Diversity of Cultural Expressions. Retrieved from http://portal.unesco.org/en/ev.php-URL_ID=31038&URL_DO=DO_TOPIC&URL_SECTION=201.html [ Links ]

United Nations, & Bureau de Liaison Bruxelles-Europe. (2010). Creative Economy: A Feasible Development Option. UNCTAD. Retrieved from http://unctad.org/en/Docs/ditctab20103_en.pdf

Verheyen, J., & Pierre-Alain, F. (2012). Etude de faisabilité d’un Pôle Média sur le site Reyers (Idea Consult). Brussels: L’Agence de Développement Territorial pour la Région de Bruxelles Capitale (A.D.T.). Retrieved from http://www.adt-ato.brussels/sites/default/files/documents/IdeaConsult_ADT_Pole_media%20_Rapport_13022013.pdf

Wasko, J., & Meehan, E. R. (2013). Critical crossroads or parallel routes?: political economy and new approaches to studying media industries and cultural products. Cinema Journal, 52(3), 150–157.

Williams, R. (1983). Culture & Society 1780-1950 (Vol. 1). New York: Doubelday Anchor Books. [ Links ]

World Intellectual Property Organization WIPO. (2015). Guide on surveying the Economic contribution of the copyright industries (WIPO Publication No. No. 893 E). Geneva. Retrieved from http://www.wipo.int/edocs/pubdocs/en/copyright/893/wipo_pub_893.pdf [ Links ]

NOTES

1 The categories are inspired by the report Creatieve industrieën in Vlaanderen: mapping en bedrijfseconomische analyse published by Flanders DC (Guitte, Schramme, & Vandenbempt, 2010).

2 The findings were derived from the elaborations of the KEA (KEA European Affairs, 2006) and complemented with additional institutions.

3 C = core; A = associated; E = excluded.

4 NACE is a classification system providing the framework for collecting and presenting a large range of statistical data according to economic activity in the fields of economic statistics developed within the European statistical system (ESS). Other classification systems exist, that are similar to the NACE and are applied in other countries, like the SIC in the UK and the NAICS in the US.

5 The results within an exhaustive table can be found in the Appendix.

6 Amin and Thrift (1995) define “institutional thickness” through four key constitutive elements: (1) a strong institutional presence; (2) a high level of interaction amongst these institutions; (3) well-defined structures of domination; and (4) inclusiveness and collective mobilization (a common sense of purpose around a widely-held agenda).

7 The European Cluster Observatory indicated several codes through “cursive” differentiating between core and related activities. These codes are here shown as “(x)”.

8 Titles of NACE codes have been partly shortened.

9 Source (OECD, 2011)

10 Source (Power & Nielsén, 2011)

11 Source (DCMS, 2001)

12 Source (Boix, Hervás‐Oliver, & Miguel‐Molina, 2015)

13 Source (Verheyen & Pierre-Alain, 2012)

14 Source (KEA European Affairs, 2006)

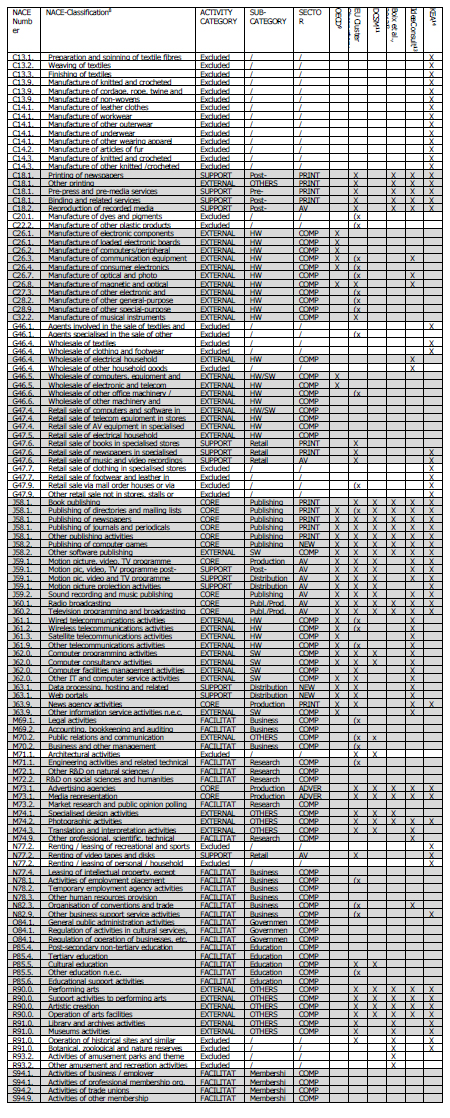

APPENDIX - Analysis of NACE codes.8 9 10 11 12 13 14