Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Acessos

Acessos

Links relacionados

-

Similares em

SciELO

Similares em

SciELO

Compartilhar

Observatorio (OBS*)

versão On-line ISSN 1646-5954

OBS* vol.12 no.1 Lisboa mar. 2018

Social and Media Repercussion of Anonymous Suicides in Spain during the financial crisis

Miguel Vicente Mariño*

*Facultad de CC. Sociales, Jurídicas y de la Comunicación, Universidad de Valladolid

ABSTRACT

Suicide accounts for more than 3000 casualties in Spain every year, turning into one of the most prevalent causes of death. These figures are similar to other Western countries, meaning that suicides are common in these societies, although one might not be aware of their occurrence. Media attention is voluntarily outside of this daily phenomenon, as a way to avoid replication and proliferation of suicidal behaviours, even there is not clear evidence about this causal linkage between coverage and imitation. There is not a solid line of research about the causes lying behind suicides, so the economic and social factors are present, even their influence is not well determined yet. The unexpected impact of the financial crisis in Spain led to a growing number of cases with a direct relation between life conditions and the fatal decision. This article explores the coverage (and the lack of it) in the Spanish media of several cases of “economic” suicide, most of them linked to eviction processes and critical financial situations. We aim to shed some light on a controversial issue regarding media effects and public policies.

Keywords: Suicide, Financial Crisis, Spain, Media Coverage.

Introduction

After several years collectively and, to a great extent of the population, unconsciously inflating a housing and financial bubble, Spain experienced a dramatic recession since 2009. The times of the Spanish economic miracle led into a cruel situation for a big part of the population. Individuals and families, suffering a record unemployment rate within the European Union and asphyxiated by a growing private debt, claimed against a mortgage system placing the banks’ interests at the forefront, while citizens remained at a secondary stage. Suicides can be considered as a signal that a wide amount of the population simply cannot keep up facing the same conditions for a long and lasting period of time. This dramatic individual behaviour easily accessed the media platforms and social media, even these acts are always presented with a remarkable distance towards the audience, in order to avoid replication. Social movements, ranging from wide approaches as the 15 May to more target-oriented groups of action as the Platform of Mortgage Victims, represented the interests of these voiceless individuals, leading to a political action partially renewing the mortgage law in Spain and to a growing crystallization of these critical discourses in the Spanish political system, with Podemos as an important reference in this transition from the streets to the parliaments.

This article is focused on acts of suicide committed by anonymous individuals in Spain since the irruption of the financial global crisis in this country. It is composed by six sections. The first one provides the readers with a basic background about the specificities of the financial crisis in Spain and how these singularities, both related with structural and punctual factors, are useful to understand better the way suicide is portrayed by the media and interiorised by society. The second section shortly deals with the basic facts about suicide in Spain, advancing from the macro to the micro level. The third section tries to reflect on the theoretical relations established between media and suicide, presenting approaches where the effects of mediated messages on individuals are explained to a better understanding of the problem. The fourth and fifth sections are devoted to the analysis of the way of individual acts of suicide in Spain are, first, covered by the media and, second, used by social actors as a symbolic resource of the political struggle against austerity measures imposed to the society. To conclude, the sixth section presents some brief conclusions about the social and media repercussion of anonymous suicides in Spain, collecting some of the central ideas of this article.

Basic coordinates to understand the financial crisis in Spain

The first consequences of the financial crisis in Spain were not perceived as early as in other countries within the Western world. The news about the 2007 and 2008 global financial crisis arrived to the Spanish media as a direct consequence of the centrality of the United States of America in the national political and media agendas. However, it was not clear that the effects of these threatening processes would be affecting the Spanish economy: it initially seemed more a matter of Wall Street brokers than a real threat to the established lifestyle.

The general elections to the Spanish Parliament were held in March 2008 and the word crisis started to be present among the topics to be discussed during an intense campaign. But, Prime Minister José Luis Rodríguez Zapatero kept his position for a second 4-years mandate, getting a slightly better result than after his unexpected triumph back in March 2004, in an election held only three days after the suicidal Madrid bomb attacks that killed 192 people.

During this 2008 campaign, the Socialist Party (Partido Socialista Obrero Español, PSOE) presented a record of social measurements developed between 2004 and 2007 as their main political contribution, refusing to talk about the risks that were growingly perceived in the Spanish economy. The good evolution of national finances during the previous ten years was mainly supported by a strong construction sector: the revenues were mainly invested in building houses and infrastructures, so the bubble kept on growing without almost any alarm signal coming from the political or media spheres.

In August 2011, the two political parties holding the strongest citizen support in Spain (PSOE and Partido Popular, PP) during the whole democratic period started in 1978 agreed on a modification of the Spanish Constitution in order to set some limits to the public expenditure and deficit. One should be aware that the process to modify the main Spanish law requires a solid majority, so the collaboration between the two leading parties at that time was unavoidable. Surprisingly and after a fast and hidden negotiation process, this agreement was reached, discussed and approved by the Parliament in the middle of the summer holidays. In order to put this decision into context, one might remember that the Spanish Constitution was only reformed twice since its very first approval in 1978: it was in 1992 to include a small adaptation to allow the application of the Maastricht Treaty. This decision symbolically meant a final movement for governing PSOE, which three months after was clearly defeated by the conservatives in the General elections of November 2011. The intense pressures coming from the stronger countries in the European Union partially explain the unexpected and extremely fast procedure to modify the Constitution, also questioning the national sovereignty, as it happened in other EU countries.

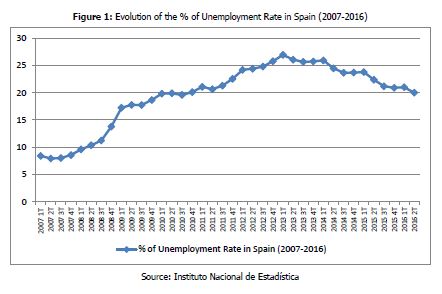

Between 2009 and 2014, the economic situation of Spain was extremely negative. The unemployment rate was on a dramatic rise, climbing up to more than a 20% of the population and reaching more than a half of the young people (see figure 1).

Even unemployment can be considered as a structural factor in the Spanish labour system, the intensity and the continuity of these figures were the crudest evidence of the problems suffered by the people during this period, as all public opinion polls have showed.

The Spanish political authorities relied on extreme austerity at the macro level, following the instructions coming from global financial actors, such as the International Monetary Fund, the European Central Bank, and the European Commission. The two main political parties kept the same position along these critical years and the difference between conservatives and social democrats was reduced to a minimum expression, in the eyes of lay people. In this political scenario, collective social action needed to show up, as the effects of the crisis started to be manifest, being acts of suicide one of the most sensitive ones.

On 15 May, 2011 the Spanish civil society stood up in a pacific manner to claim against the very diverse political and economic institutions in charge of the situation. The social protests were pointing out the contradictions of the classical system of political representation and the negative effects of the close relation between politicians and the main private companies in the country. Under an apparently improvised appearance, the squares of the Spanish capitals were appropriated by thousands of citizens willing to replace a seemingly exhausted political system by new grounds where decisions were taken in a more active and participatory way by individuals. Víctor Sampedro and Josep Lobera (2014) highlighted the transversal nature of this social movement, identified with labels like ‘Indignados’ or 15 May that successfully reached the international media and stood at the forefront of the wave of social protests against the austerity measures adopted at most of the countries around the world to challenge the global final crisis.

Among the most active organizations in the 15 May Movement, the Platform of Mortgage Victims (Plataforma de Afectados por la Hipoteca, PAH) dealt with the financial problems experienced by the individuals as a consequence of more than a decade where the access to credits was facilitated in an excessive and not justified way by the Spanish banks. The national economy was on the rise mainly due to a powerful housing sector and this required a constant feed in terms of acquiring new properties and, consequently, fostering new projects. The radical transformation of natural landscapes like those in the Spanish seaside are solid proofs to perceive the dimension and consequences of the housing bubble artificially created during the first years of the current century, also in terms of its relevant environmental impacts.

The end of the virtuous cycle arrived a little later than the Great recession of 2008, but it certainly modified the reality of thousands of Spanish families. Unsustainable private debts led to direct actions from the banks and the courts, increasing drastically the amount of evictions and placing the individuals on the edge, both from the economic and psychological perspectives. This policy derived into outrage and despair among the medium and low-income social groups, unable to face this situation with their own resources and opening the doors to dramatic decisions, as the ones related to suicide that will be explained in the next section.

The very last events in Spain point to a slow recovery in the main economic indicators, even the unemployment rate is still above the 20% of the active population. But the political disaffection is on the rise due to the big amount of Corruption cases present in all the public and personal agendas. Investigations about illegal relations between business professionals and political representatives during the last years are proliferating and questioning the viability of the classical system of political representation. Uncertainty is high when it comes to look for a future scenario, whereas the irruption of new political parties is challenging the traditional forms of politics.

Explaining suicides in Spain: from macro perspectives to individual approaches

This section aims to provide some main aspects about the way suicide has been researched in Spain during the last decades, in order to point out the dominant research topics and frames. The prevalence of psychological and psychiatric approaches is obvious, but there are also some systematic attempts to explore the social and economic dimensions of this behaviour.

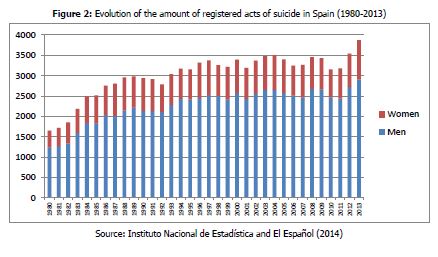

As an updated indicative measurement, Spain registered 3910 suicides during 2014 with an imbalanced gender distribution, as 2938 were men and 972 were women, following a similar longitudinal path as the one presented in figure 2 taking the 1980-2013 as a period of reference.

More than 3500 acts of suicide a year means that there are 10 suicides every day in the country, added to a significantly higher number of attempts, leading to a suicidal rate of 8’42 deaths per every 100.000 citizens. Suicide has kept its position as the first main non-natural cause of death for several years, since reaching that place in 2008.

An in-depth report about suicide elaborated by 93 metros and El Español (2014) presents abundant information about the way these practices are distributed among the Spanish territory (regions, provinces and municipalities or more than 10,000 inhabitants) and it also highlights the fact that Spain has not a different behaviour compared to other similar countries. In fact, the above mentioned rate of 8 suicides per 100,000 citizens is below the 11-12 established as both the European Union and the World average. Consequently, there is nothing extraordinary in the way suicide is being conducted in Spain, as it is usually placed in the middle to last positions within global statistics.

It is worth mentioning that another important cause for external deaths in Spain has traditionally been traffic accidents. This was until 2007 was the first cause of external deaths, reaching its highest peak in 1989 with 5940 casualties. However, in 2014 the official data are recording 1132 deceases following a successfully constant drop down, as figure 3 show.

How can we explain this reduction? The economic efforts to renew the national road system, increasing the amount of highways, together with a persistent and active promotional campaign about safety have paid off, as the risks of accidents have been significantly dropped down. There are diverse concurrent and structural factors, but one of them points to the fact that all news media are constantly tracking the accidents and deaths on roads. Every newscast is reporting traffic accidents, mainly when they are occurring in periods of the year where a dense circulation is on the roads, following but an immediate season and year balance: data are constantly in the agenda, available and reachable to everyone willing (or not) to listen about them and creating a kind of common consciousness regarding the benefits of a safe conduct while driving.

Contradictorily, one will not find almost a single mention about suicide of anonymous citizens in the media due to an arguable understanding of the imitational risk model that will be explained in the following section. In the meantime, official figures have remained almost stable during the last 25 years, with around 3500 suicides per year and a progressive increase in the last two years with official data (2013-2014), due to a methodological modification in the way data about deceases are registered and processed in Spain.

The stable, but growing, curve described points to the absence of official programs oriented towards suicide prevention. This situation illustrates the fact that this issue is not a priority for current social policies in Spain, given the fact that the national rate is among the lower ones within the European Union.

Another good example of different policy and media strategy is the attention paid to gender violence, an execrable practice that leads to approximately 70 women killed in Spain every year. Since 2003, there is a common agreement between political parties, social actors and media companies to keep this issue alive and present in daily agendas. Every episode is registered, screened and portrayed extensively as a consequence of the evidence breach of human rights that women are suffering. Nevertheless, the figures are not returning a similar success as in the previous case of traffic accidents, as the minimum record achieved in 2012 of 52 women killed expanded up to 60 in the last year with full data (2015).

There is a long and wide discussion about the connections between suicide and the factors behind these acts. Spanish scholars have also approached this controversy (Roca et al., 2014; Domènech et al., 2014; Serrano and Heredia, 2018). Even there is not an agreement about the economic explanation to suicide acts yet; the influence of the financial crisis is one of the aspects to be taken into consideration when explaining individual behaviours, as most of them are related to a deprived individual situation. Therefore, we are not claiming here a direct relation between the financial crisis and suicides, even we tend to identify diverse cases where the economic circumstances are key to understand the final decision taken by a given individual.

Media, imitation and suicide

This section develops the existing connection between media and suicide from a general perspective, dealing with the existing protocols and recommendations to report about these episodes and the theories regarding their effects on individual behaviours.

Suicides are acts based on an intimate and, most of the times, individual decision. However, as events that step outside of average daily life, they are usually attracting not only our attention but also the one of those who works to tell us what is happening in the world we live in. Journalists and media outlets are always eager to present salient news to their audiences and suicides bring together diverse news values turning them into a potentially interesting news topic. If this interest is complemented with a popular profile as the main character, then the media attention will significantly rise. But the strategy seems to be different when the suicide is conducted by an anonymous subject. Additionally, As Gupta et at. (2017) underlined these individual deaths do have political resonances.

Media influence has always been a strong area for both public discussion and scientific research. Exploring the relation between what media present to the public and the reactions of these audiences is one of the core keys to understand Media Studies and Communication Research as a scientific field. From the initial approaches, back on the 1920’s, based on direct and powerful media effects to the empirically well-grounded current knowledge about limited media effects, the evolution has been remarkable. Nevertheless, the idea of a direct correlation between what the media say and what the people do is still very present when some decisions regarding media coverage are being taken.

In a short essay published in The Lancet , Belinda Jack (2014) provides a brief explanation about what is widely known as ‘the Werther effect’, named after one of the most prominent books of the German author Johann Wolfgang von Goethe:

“It is difficult to ascertain today whether or not there was a sudden rise in the suicide rates of broken-hearted young people in the 18th century, but modern psychiatric research suggests the existence of a so-called Werther effect of suicide contagion. As a result, many countries now have guidelines for the media when reporting suicides. It turns out that it is not simply the fact of a suicide that might affect the actions of others, but the manner in which it is reported” (Jack, 2014: 19).

This essay points out that an imitational behaviour might be stimulated with in-depth media coverage of these acts. Even within her text, Jack is also presenting the limits of this approach. She explores some of the narrative aspects that could help to find more solid explanations to the supposed increase in suicides after the unarguable success of Werther at the social level. The discussion about the existence of this effect, also known as the “copycat” one has led to an intense debate in very different settings, ranging from academics to media spheres. Traditionally, the prevalence of the suicide rate would increase if the portrayed act is committed by a famous individual, so the lack of information about anonymous suicidal attitudes might also be related to other cultural and social aspects.

The World Health Association (WHO, 2008: 3) synthetized the conclusions of a working group exploring the relation between media content, imitation and suicide in the following eleven recommendations:

- Take the opportunity to educate the public about suicide

- Avoid language which sensationalizes or normalizes suicide, or presents it as a solution to problems

- Avoid prominent placement and undue repetition of stories about suicide

- Avoid explicit description of the method used in a completed or attempted suicide

- Avoid providing detailed information about the site of a completed or attempted suicide

- Word headlines carefully

- Exercise caution in using photographs or video footage

- Take particular care in reporting celebrity suicides

- Show due consideration for people bereaved by suicide

- Provide information about where to seek help

- Recognize that media professionals themselves may be affected by stories about suicide

Trying to reinforce the key role attributed by experts to media content and effects, this report clearly presents both strengthens and weaknesses of broadcasting suicide attempts or acts:

“The factors contributing to suicide and its prevention are complex and not fully understood, but there is evidence that the media plays a significant role. On the one hand, vulnerable individuals may be influenced to engage in imitative behaviours by reports of suicide, particularly if the coverage is extensive, prominent, sensationalist and/or explicitly describes the method of suicide. On the other hand, responsible reporting may serve to educate the public about suicide, and may encourage those at risk of suicide to seek help” (WHO, 2008: 5).

Therefore, it is widely accepted that the media has something to say about suicide, as they can sometimes activate the keys to display individual behaviours or to refrain them, being also a good set of tools to reach certain risk groups. Diverse guidelines and norms were developed by health authorities, but most of them agree on setting safety measurements to spread detailed information about the acts and on including punctual information and guidance to avoid any dramatic decision.

It is striking, however, that the very first guideline opening is not getting -at least in Spain- a solid development in terms of social policies. Placing education first means an explicit effort to make citizens aware of the significance and implications of suicide. As far as we are aware of, the investment to educate population in the Spanish case is minimal, whereas the media respect to the other recommendations should be considered as high.

Another exception that is linked with the absence of public investment in this matter is the absence of information about where to seek help: the scarce resources devoted to publicly fight against suicide makes it impossible to the journalists to address this information. Whereas news reporting gender violence are always finished with a clear invitation to victims and people aware of potential episodes of sexist violence in order to use a free-of-charge phone number offered, there is no psychological attention to those facing suicide attempts daily, despite the worrying figures we have presented so far.

Suicides related to the financial crisis seemed to have increased during the last years, so drawing a causal clear line between economic conditions and acts of suicide could be perceived as contrary not only to some of the guidelines previously mentioned but also to a strong taboo in the Spanish society and culture. However, as the following sections will prove, this connection is, to a different extent, suggested -when not openly claimed- in most of the collected reports.

Media coverage of anonymous suicides in Spain during the financial crisis

This section explores the main features of the way Spanish printed and online news outlets are reporting about suicides related to economic causes. It points to the predominant strategies when dealing with sensitive news topics and it also highlights some of the perceived limitations of these approaches.

Individual acts of suicide are most of the times voluntarily hidden by the media in Spain. At least, they are not receiving the same attention as other similar episodes of violence. As we outlined in the previous section, there is a mainly unwritten professional agreement among media workers that attributes an exemplary effect to the published content towards their audience. Following this rule, a strong coverage of acts of suicide would lead to an increase in the amount of suicides attempted and committed, as people will receive useful information about how to take and execute such a final decision. And alternatively, a predominant silence would keep things in a better way, even the statistics showed in the second section of this article illustrate that trends seem to be clearly stabilized, when not increasing the rates.

Paradoxically, the main Spanish news media tend to pay attention to macro sociological information about suicide and they explore the connections between big figures and the potential causes explaining them. So one can find a lot of news pieces searching for evidence about the connections between the financial crisis and the suicide rate, mainly coming from external research conducted in diverse countries, but with similar schemes and purposes. In June 2014, the leading quality newspaper in Spain, El País, reported more than 10,000 suicides in Europe, Canada and the United States because of the crisis (Prats, 2014), drawing on the conclusions of an article published at the British Journal of Psychiatry (Reeves, McKee and Stuckler, 2014). As a proof of the ongoing statistical debate at this level of analysis, and using a similar time period (from 2007 until 2011), Domènech et al. (2014) state that there is no correlation between suicide rates and the ongoing financial crisis neither in Spain nor in Europe. In this confusing scenario in terms of empirical evidence, journalists deal with a controversial topic and reproduce these contested explanations.

Hence, the attraction of the suicide topic is present at the general level, but it is also evident that this interest is blocked when it descends to the individual cases, where a quite strict policy is conducted in terms of ethics and standards. This ambivalence could help us to understand the weak attention paid to individual acts of suicide and the generic interest in setting a strong connection between economic and individual decisions.

Most of the times, the information about the individual committing suicide is limited to very basic information about his or her name -sometimes name and surname; others, only initials-, and age. Other personal data, such as the age, the marital status and the relatives that the suicidal might have are also included in the reports, depending on the length of the article, which is usually quite reduced. If these suicides are anonymous, it is very unlikely to find a news piece exclusively devoted to explaining what has happened and provide their audiences with additional contextual information, apart from mentioning the way that suicide was committed.

Most of identified news stories share some aspects that are worth to be mentioned, in order to establish some recognisable trends when Spanish media are facing a case of anonymous suicide with, at least, an apparently economic motivation.

- In most the cases, the identification of the suicided people is only completed with his/her name and/or initials. Information about given or family names is not always provided, as a way to avoid an excessive identification of the victim and the family.

- There is a short description about the suicidal technique applied by the individual, detailing the way that life came to an end. The distance kept by the journalists is often correct and and they usually stick their report factual evidence.

- Families are, either directly or indirectly, mentioned, increasing the human interest of the news story and, sometimes, opening the door for approaches prioritizing entertainment over factual news reporting.

- There is a longer explanation about the economic context of the individual and his/her closer relatives. These descriptions are more detailed and usually backed up by testimonials gathered onsite.

- Evictions and debts with banks are most of the times the trigger for suicide. This connects with one of the relevant aspects of the Spanish economic system before the crisis mentioned in the initial sections of this article.

These news pieces are hardly ever included in the most prominent sections of the newspapers, as they are not framed as political or economic issues. Even they might count with an explicit mention to the social and financial reasons behind the individual decision, they are always presented as belonging to the individual and anonymous sphere, leading to a shorter and lighter attention.

Another significant aspect about how suicide is approached by media companies points to the fact that there is no tracking about suicide cases along time and space. Local media outlets might pay a little more attention to these aspects, as they recall similar episodes in their area, but one cannot find a continuous screening in terms of the human consequences of the crisis. As we explained before, in Spain gender violence has experienced a similar process as other violent causes of death, but the explicit political decision was oriented towards using media as the main space to publicly educate the society. The professional effort to make a social problem visible is translated into a continuous screening of the dimensions and consequences of the problem, in terms, for example, of the amount of victims or affected people. Consequently, there are strategical priorities when it comes to report about suicides and other causes of death, and the models applied to each of them are significantly different.

Suicide is, to some extent, a common topic in Spanish media coverage. Its potential impact in audiences’ minds and the attention generated by these acts justify its entrance to the media discourse. However, there is an important different when reporting about emotionally controversial topics as suicides: the kind of coverage granted to them is mainly based on the macro-sociological level, taking the whole society as a point of reference. We can find good examples of in-depth reports about suicide in Spain, some of them dealing with the question about the causes behind some of these acts and relating them to the general economic situation, but it is more difficult to find news report about specific and individual acts of suicide.

At a very first level, journalism is about news and it is striking that some salient and traumatic episodes for any given society, such as suicides, are not reported in daily media coverage in Spain. There is enough evidence about the economic influence in a small part of the suicides that are committed, but they are not included in media agendas as a result partly because of the authorities’ recommendations and partly due to the widely spread effect of the potential imitation behaviour.

One good example of the journalistic effort to understand the complexity lying behind suicides can be found in the previously mentioned monograph edited by El Español, an exclusively-online news portal, and produced by 93 Metros. Departing from a data-driven approach, this resource explores the diverse explanations to suicidal behaviours in Spain during the period running between 1980 and 2013. This monograph works with official data from Spanish authorities and presents the information in a friendly and understandable manner, turning into an interesting resource to explore suicide from a general and international perspective. Poverty is included in a list of five keywords synthetizing the main factors to be considered when explaining suicide: age, sex, climate, mental illnesses and poverty.

“One of the great myths, which have become popular in the last few years, draws a link between suicide growth and economic crisis. Many of these deaths are said to be a direct result of an eviction or a redundancy. But it is a serious mistake to attribute suicide to a single cause, for this oversimplifies the issue . All the experts agree that it is a multifactor phenomenon, a result of risk and triggering factors, but also of protective factors” (93 Metros and El Español, 2014).

The following quote by Maurice Halwachs, included in this monograph, explains briefly but precisely the complexity of direct attributions between crisis and suicides, at the same time it points clearly to the relevance of social and economic factors:

“What has an impact on suicide figures is not so much the crisis itself, as the progressive weakening of the inclusive and supporting capacity of the community generating the crisis.”

One of the direct consequences of the reigning anti-austerity measures adopted, at least, in the European Union is the reduction of public budget for facing social needs. As far as the main social services (health, education, pensions and social services) are suffering a persistent drop of resources, programs to tackle the challenges put forward by individual acts of suicide see their chances to be developed significantly reduced.

Consequently, stating a direct relation between the economic climate and the suicidal behaviours cannot be presented as a solid connection across time and space, but it must be included within the factors potentially leading to them, mainly when one can read testimonials that are clearly pointing to this reality as a driving force in the final decision taken by the suicidal:

“My husband committed suicide 20 days ago due to the economic problem we had. He was receiving the unemployment subsidy, he was only 45 years old and he was told that he was too old to work. (…) He chose taking the easiest way and leaving me, my daughters and my grandsons. This is a call to make everyone aware that there is a lot of people like me, and I would like to see that someone is doing something to avoid these situations.”1 (ABC, 2012)

This excerpt was taken from a direct phone call to a leading radio general magazine and was echoed by a lot of printed and online media, as it was one of the very first public statements from a first-person-affected voice exposing not only the relation between suicide and crisis, but also calling for an institutional action to fight against this problem. These arguments are also presented by professional journalists within their reports:

“The crisis kills. In Italy, in Greece… and in Spain. Joaquín did not even want to hear talking about subsidies. He only wanted to work. Two years of unemployment buried him down: he decided to hang while he was preparing the lunch for his wife.”2 (Checa, 2012)

“He spent two years without anything, two years that stole his self-esteem. Another life buried down the collapse of the construction sector. He was not asking nothing else (and nothing less) than an employment in a country where 4’7 millions of people are queuing at the INEM (National Institute of Employment). (…) On April the 3rd something broke inside him, inside a man missing the word depression in his vocabulary, without a single antecedent of psychological problems and with a solid spiritual vitalism. Until that moment. One week before he went to the bank trying to renegotiate the mortgage payment. Once he ran out his unemployment coverage, he would only receive 400 euros as a subsidy and he must pay 500 euros per month for his house, a house he refurbished with his own hands, a destroyed building standing still for more than half a century and that is still under a 90,000 euros debt. The bank did not budge. And Joaquín could not keep the pulse of life.”3 (Checa, 2012)

News articles like this one are a good example of a clear position taken by journalists and media companies. Local newspapers, in this case, are clearly pointing to, on the one hand, political authorities not able to keep unemployment figures under control and, on the other, to the individual decisions taken by the financial power. This mix between structural instances and individual decisions is very often presented as an aftermath fostering suicide, as a way to connect the structure and the agency in a complex combination.

A micro approach, nevertheless, can also be found in the Spanish media. It might be lacking the same periodicity as the macro perspective, because of the absence of periodical publications of statistical data and the ethical implications explained before-, but it is persistently present in diverse “soft-news” approaches to the information. The human interest is pursued in order to understand not only the committed acts but also and mainly, the reaction from those surrounding the suicidal and facing their lives after this traumatic turning point. Regarding this approach, a good example can be found when the newspaper with the highest circulation in Spain, El País Semanal, published a 12-page in-depth report within its weekend special issue focused on individual having attempted suicide and families having experienced suicides among their members (Hermida, 2016). Its presentation synthetizes most of the important aspects in the complex relation between suicide, media and society:

“It is the silent drama that no one wants to talk about. Neither It causes heated discussions on television nor forces politicians to rule. But suicide takes 4,000 lives every year in Spain. Their families have charged for centuries with a stigma that forced them to hide, as if they were carrying a shame. Some have had enough and have banded together to break the taboo. They do not mind sharing their pain if that serves at least to open a social debate. These are their stories.”4 (Hermida, 2016)

In most of the stories shaping this report, the word crisis is present, but not exclusively from a financial perspective. The critical phase leading to a suicide is faced by the interviewees, as a concept unarguably linked to explaining the facts.

In a similar way, but from a less-involved perspective, El Español departed from statistical data to detect a certain geographical area where the suicide rates are consistently among the higher ones in Spain. In “The triangle of suicidals: villages where suicide is a costum”, López Frías (2016) mixes up the diverse sources of explanation to suicide, ranging from local superstitions to legacy traditions and habits, but always including in this equation the pervasive effects of social and economic conditions in an area with a high rate of unemployment and a long tradition of unsuccessful processes of industrialization.

“There are many hypotheses: a strange chemical compound present in the water, the abundance of olive and walnut trees in the area, the altitude of these municipalities (nearly all are on the border of a thousand meters), the existence of a mineral called pyrite in the basement (which presumably cause psychological disturbances), the isolation of these villages, poor employment opportunities, genetic predisposition, a macabre tradition…”5 (López Frías, 2016)

Besides that report, the documentary 800,000 mentioned before is also a good example of audio-visual production enriching the data analysis and the journalistic immersion in complex social practices.

Another important remark comes from the fact that, as far as our collected data have shown, one cannot talk about political suicides in Spain. Most of the acts of suicide were committed in intimal scenarios and following the individual desperation of suicidals. There is no strong evidence of suicides attributing responsibilities to economic and political actors. One partial exception to this trend could be the case of Francisco J. Lema. After an attempt of suicide he featured a YouTube video titled “With blood up to the neck” (Con la sangre al cuello) explaining his personal story and pointing to some of the instance involved in his case: some weeks after he ended up committing suicide.

Even there is a diversity of types of suicide which is common to other countries and cultures, we cannot find a differentiated strategy to cover them by the Spanish media. Actually most of the information regarding the way suicide was conducted is limited to a short and basic description, contributing to the effort on not providing potential replicants information about how to proceed.

The presence of direct mentions to suicide notes in the Spanish press coverage is very rare. This fact does not necessarily mean that there are no notes written before committing suicide, as some of them can be kept in the intimacy circle of the family.

“Antonio was 42 years old and, although he was married for a decade to his wife, the couple did not have children. As farewell, he left written a shocking letter, to the point that the police sergeant who read it to the local mayor could not finish due to the emotion.”6 (Tallón, 2013)

A suicide note is something directly appealing to a micro and individual universe, but it might sometimes turn into a macro and collective process if they are disclosed and able to initiate an alternative circuit of social and cultural production. However, the content of these notes have traditionally been kept away from the public sphere in Spain and its social impact has not been influential.

Alternative sources of information about suicides

This section explores alternative routes created and followed by individuals in order to access and produce -mainly online- content related to the consequences of the financial crisis and, more concretely, of suicides linked to it.

One of the most visible consequences of the crisis at the societal level was the uprising of a strong social movement challenging the classical leading institutions within the Spanish society. The 15 May is a grassroots initiative converging different organizations acting in the civil society but with some operational objectives well established.

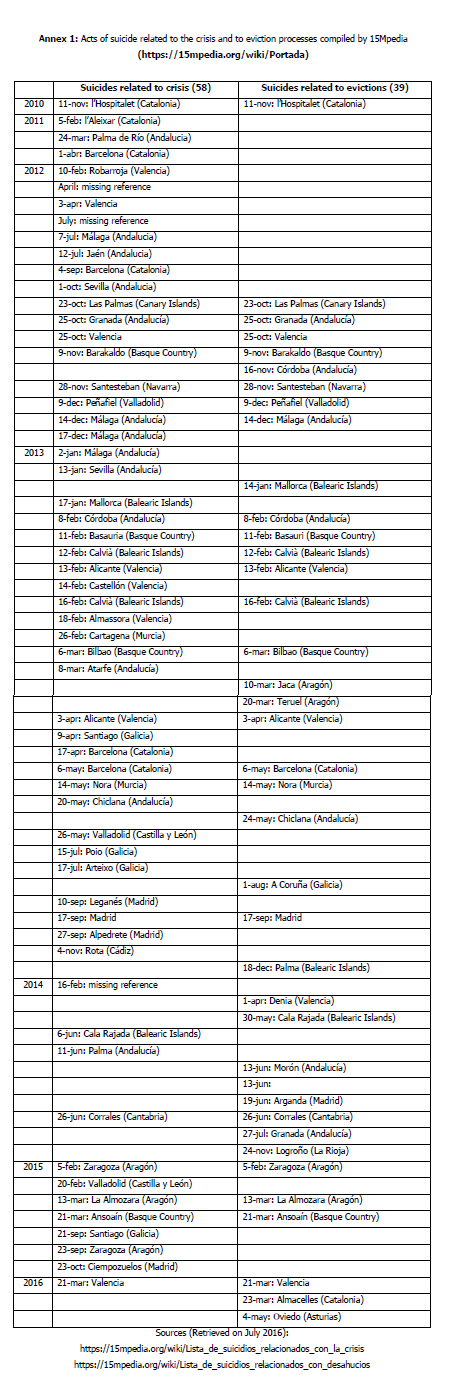

Among the diverse actions conducted under the still open and active umbrella of the 15 May movement, one can find interesting resources as the 15Mpedia, a collaborative space to develop and share common projects, tracking different aspects relevant to the social movement…. Within the period covered by this book, there are two different collections of references about suicide: one is compiling 58 acts of suicide related to the crisis, whereas the other one is devoted to the 39 suicide acts that were related to eviction processes. None of these two lists are exhaustive or official, as both of them are open to external contributions. One can find cases included in both lists and some of them are missing enough references to draw a complete vision, but they are a valuable resource produced by the very own social tissue, that is actively fighting against the social and individual consequences of the financial crisis in Spain.

All those cases are recorded with short descriptions and, when possible, further developed by digital news reports. They are also directly associated with political decisions regarding the financial crisis management, so they are a useful window to approach the consequences of anti-austerity measures and illustrate the contradictions suffered by individuals and groups.

The first documented case in the series remits to 11 November 2010, when a 45 year-old man hang himself in a street of Hospitalet de Llobregat, in the Barcelona metropolitan area (Quelart, 2010). He spent the last nine months of his life occupying with his wife and daughter an empty flat, after finishing his unemployment compensation and not being able to pay the rent of the previous flat where they lived. The information about the act of suicide is limited to the modus operandi , only highlighting the fact that it was committed in the middle of the street, making it visible to those nearby. The news piece gives much more detail about the economic reasons behind the final decision of this individual, who is only named after his initials. The journalist provides the readers with a vivid description of the agony of this blue-collar worker, mainly caused by his struggle to find resources to survive in a context of crisis.

The compiled collection of online references reaches 39 acts of anonymous suicides directly related to eviction processes, as the Annex to this article reports. The trend is reducing its intensity across time, but one should never forget that this is not an official census compiling all occurrences.

The overall portrayal of those cases arriving to the media sphere is predominantly correct, as journalists are more often respecting their professional standards and ethical codes than presented biased narrations of histories with a strong emotional background. However, one can find, even within the own media system, critical voices about the kind of coverage completed by journalists, as Javier Cárdenas, a morning radio-show anchor-man that blamed on their colleagues of keeping silence about some suicides happened in Spain.

A significant question coming from this fact points to the different attention granted to evictions in Spain compared with the one achieved by suicides. This is pointing to the existence of journalistic norms and cultures that tend to privilege some topics and approaches over others. In September 2011, the president of ADICAE, the association of users of banks, saving banks and insurances reported more than 300 evictions per day in Spain, and these figures remained stable during the whole crisis severely affecting the daily lives of thousands of Spanish families.

The centrality acquired by the PAH within the complex organization of the 15 May movement is a good proof of the relevance that housing issues are an unavoidable factor to understand the effect of the financial crisis in the Spanish society and, as an extension, in the Spanish media landscape. A valid proof is the attention paid to the actions conducted by Stop Evictions (Stop Desahucios) during the crisis: the high pressure developed by these initiatives was present -from different positions and arguments- on the official media discourses, mainly when their actions turned their focus towards political authorities publicly targeted and blamed as liable of the dramatic situations suffered by individuals.

Criticizing the media silence towards suicide and its causes

The growing space gained by civil society in Internet has also opened windows presenting a critical view towards the dominant social and media practices regarding the media coverage of suicides and, more acutely, of suicides in the frame of the current financial crisis.

“The crisis ruins and kills. In Spain there are daily cases of suicide that are not reported by the media. It is all about not creating a social alarm and to mitigate the tragedy, it is alleged. Once again, the effects are on top of the causes. And the causes have name and surnames: political and financial castes. One of the last cases was the one of a disabled woman in Málaga. The press hided the event, even the ostentation of her death, witnessed live from the street by more than a hundred people.”7 (Alerta Digital, 2012)

There is a silent agreement within the profession in order to avoid providing too much information about data surrounding suicides, even sometimes we can found headlines not meeting some of the recommendations and providing a detailed description of both the suicide act and its attribution of responsibility:

“Woman dies after burned herself on a bank while shouting: 'You have taken me everything!'”8 (EFE, 2013)

Direct appeals to political and financial actors are accessing the news when individuals perform a public statement about them:

“The priest Joaquín Sánchez, member of the Platform of Mortgage Victims (Plataforma de Afectados por la Hipoteca, PAH), deeply regretted what happened in La Ñora and he showed himself as a critical voice. «Those defending the system and the Mortgage Act are criminals and both the Government and the banks are complicit in this», stated. The churchman explained that «there are people that, due to poverty and social embarrassment situations, are helpless and opt for drastic measures» and added that «these people needs to be loved, be respected and be at their side. Doing that would avoid dramas like this»”9 (Tallón, 2013).

Struggling against the predominant silence around suicides, the civil society has recently developed their own initiatives. The absence or insufficient application of regional and national plans to act against suicides has pushed these individuals to join their efforts in associations that mix their actions between giving support to the victims and raising awareness about the issues related to suicide.

“The first association of survivors, Després of Suïcidi (After Suicide), was founded in 2013 by Cecilia Borras, a psychologist from Barcelona, after losing her son Miquel, 19. In Madrid AIPIS existed since 2009, created by Javier Jiménez for suicide prevention activities supplying the lack of official programs. Cecilia and Javier have been like two guardian angels for hundreds of people. They have past -and still pass- hours on the phone with strangers who call them desperate, not aware of anywhere else to turn to. Their apostolate begins to bear fruit. Under their inspiration, survivors of Huelva have created the platform A tu lado (Close to you). And there are other groups breaking the silence in the Canary Islands, Basque Country and Galicia. They argue that a portion of suicides could be avoided. For this, it is essential that the problem is not hidden and that the prevention plans drawn up by the health authorities are applied, ast they are hardly met nowadays.”10 (Hermida, 2016)

Media silence about suicides, or the dominant approach to their coverage, seems one of the questions to be, at least, reconsidered in this process of public education and information, as it should not necessarily lead to an imitational conduct or to an increase in the suicidal rate, but it can help to a better attention and care to those facing difficult times in their lives, both due to individual (psychological) or collective (social and economic) circumstances.

Conclusions

Even there is no scientific consensus about the direct linkage between economic conditions and the rate of suicide in our societies yet, a brief approach to the consequences of the growing economic unsafety at the individual level face us with a hard reality. The struggle to survive in a much more competitive environment leaves a lot of people behind: they are not only men and women with psychological or psychiatric problems; they are common people that were unable to generate or to keep the resources they need to live due to a growing inequality. So, pointing at specific cases lead us to the evidence that there are economic suicides: it does not matter if they are a lot or if they are just a few; the important thing is to reveal this situation and put forward

Following Arnoldo Kraus (2011, p. 42), “suicide is another aspect of human condition that is inscribed in the right of people to choose the circumstances of their own death”. However, most of the anonymous acts of suicide that are appealed in this book point to a certain moment of time when the final decision is influenced by a given political and economic context. It is worth questioning to which extent some of these suicides were voluntary acts of freedom or the outcome of a certain political crisis management expelling thousands of people out of the system. And when this is the predominant explanation about a suicide, then both society and media need to react and rethink the validity of the current social structure and media representations.

Media coverage of anonymous suicides in Spain, before and after the long and still ongoing financial crisis, have relegated social criticism in order to explain and frame these behaviours, placing the privacy rights of the suicidal as a priority and reinforcing the idea of a direct connection between what is on the media and what people think and do afterwards.

As far our research is concerned there are no political consequences connected with the acts of suicide reported, or under-reported, by the media during the financial crisis. The fact that suicide is still condemned to the sphere of intimacy makes that its social impact is most of the times eclipsed, not acknowledged and absent of the public arena. Keeping in mind the risk of establishing direct connections between acts of suicide and the economic climate, the amount of episodes presumably related with the austerity measures taken by political and financial instances seems too high. However, neither media nor most of the actors belonging to the third sector of social activities are claiming for political responsibilities in a clear manner. Suicide is most of the times outside from the political statements, reproducing the alleged social and culturally-grounded fear of contagious that is usually also behind the media coverage.

Claims for an alternative approach to media coverage and social attention to suicide are coming from those having a closer relation with these practices. Both scientific experts and relatives are sharing their experiences and priorities in order to increase the pressure towards political authorities, in order to update or, at least, apply policies tackling this challenge to our societies. A respectful but informative media approach could be helpful in reaching this objective.

List of references

93 Metros and El Español (2014). “800,000. Evolución de suicidios en España 1980-2013”. Online monograph. Retrieved from:

Spanish version: http://www.elespanol.com/documental/suicidios/

English version: http://www.elespanol.com/documental/suicides/

ABC (2012, April 23). “Mi marido se quitó la vida hace 20 días por la crisis. Por favor, seguid luchando”. ABC . Retrieved from: http://www.abc.es/20120423/sociedad/abci-crisis-lucha-201204231216.html

Alerta Digital (2012, July 29). “Alarmante incremento del número de suicidios en España motivados por la crisis y silenciados por los medios”. Alerta Digital . Retrieved from: http://www.alertadigital.com/2012/07/29/alarmante-incremento-del-numero-de-suicidios-en-espana-motivados-por-la-crisis-y-silenciados-por-los-medios/

Checa, Arturo (2012, May 6). “La maldita crisis mató a mi marido”. Las Provincias . Retrieved from: http://www.lasprovincias.es/20120506/mas-actualidad/sociedad/crisis-mato-marido-201205061845.html

Domènech, Aloma; Gili, Margarida; Salvá, Joan; Homar, Clara; Sánchez de Muniain, María; Llobera, Joan; and Roca, Miquel (2014). “Variables socioeconómicas asociadas al estudio”. Cuadernos de Psicosomática y psiquiatría de enlace , 111, pp. 15-21.

EFE (2013, May 10). “Muere la mujer que se quemó a lo bonzo en un banco al grito de: '¡Me lo habéis quitado todo!'”. El Mundo - Comunidad Valenciana . Retrieved from: http://www.elmundo.es/elmundo/2013/05/10/castellon/1368188154.html

Gupta, Suman; Katsarska, Milena; Spyros, Theodoros; and Hajimichael, Mike (2017). Usurping Suicide. The Political Resonances of Individual Deaths . London: ZED Books.

Hermida, Xosé (2016, July 10). “Suicidio, el gran tabú”. El País Semanal . Retrieved from: http://elpaissemanal.elpais.com/documentos/suicidio-el-gran-tabu/

Jack, Belinda (2014). “Goethe’s Werther and its effects”. The Lancet Psychiatry , vol. 1, nº 1, pp. 18-19. DOI: 10.1016/S2215-0366(14)70229-9

Kraus, Arnoldo (2011). “Suicidio: notas y alegatos”. Letras Libres , febrero 2011, pp. 36-43.

López Frías, David (2016, July 30). “El triángulo de los suicidas: en los pueblos donde quitarse la vida es una costumbre”. El Español . Retrieved from: http://www.elespanol.com/reportajes/grandes-historias/20160729/143736438_0.html

Prats, Jaime (2014, June 12). “10.000 suicidios más en Europa, Canadá y Estados Unidos”. El País . Retrieved from: http://sociedad.elpais.com/sociedad/2014/06/12/actualidad/1402570506_011995.html

Quelart, Raquel (2010, November 10). “Un padre de familia a punto de ser desahuciado se ahorca en plena calle”. La Vanguardia . Retrieved from: http://www.lavanguardia.com/sucesos/20101111/54067710058/un-padre-de-familia-a-punto-de-ser-desahuciado-se-ahorca-en-plena-calle.html

Reeves, Aaron; McKee, Martin; and Stuckler, David (2014). “Economic Suicides in the Great Recession in Europe and North America”. The British Journal of Psychiatry , June 2014. DOI: 10.1192/bjp.bp.114.144766

Roca, M; Gili, M.; García-Campayo, J.; and García-Toro, M. (2014). “Economic crisis and mental health in Spain”. The Lancet , 382, pp. 1977-1978.

Sampedro, Víctor; and Lobera, Josep (2014). “The Spanish 15-M Movement: a consensual dissent?”. Journal of Spanish Cultural Studies , 15 (1-2), pp. 61-80 . DOI: 10.1080/14636204.2014.938466

Serrano, Rafael; and Heredia, Adrián (2018). “Spanish Attitudes Towards Euthanasia and Physician-assisted Suicide”. Revista Española de Investigaciones Sociológicas, 161, pp. 103-120. (http://dx.doi.org/10.5477/cis/reis.161.103)

Tallón, Manuel G. (2013, May 16). “Un hombre se suicida en La Ñora cuando iba a ser desahuciado”. La Opinión de Murcia . Retrieved from: http://www.laopiniondemurcia.es/murcia/2013/05/15/hombre-suicida-nora-iba-desahuciado/469518.html

WHO, World Health Organization (2008). “Preventing Suicide. A Resource for Media Professionals”. Report included in Preveting Suicide: a Resource Series. Retrieved from: http://www.who.int/mental_health/resources/preventingsuicide/en/

List of audiovisual materials

El suicidio se puede evitar.

Redes (TVE, 2009 December 6). Retrieved from: http://www.rtve.es/alacarta/videos/redes/redes-suicidio-se-puede-evitar/644326/

La muerte silenciada. Suicidio, el último tabú.

Documentos TV (TVE, 2013 September 8). Retrieved from: http://www.rtve.es/alacarta/videos/documentos-tv/documentos-tv-muerte-silenciada-suicidio-ultimo-tabu/1692885/

Suicidios, la ley del silencio.

Informe Semanal (TVE, 2012 April 14). Retrieved from: http://www.rtve.es/alacarta/videos/informe-semanal/informe-semanal-suicidios-ley-del-silencio/1376327/

Los suicidios de la crisis

Hispan TV, Punto de Mira (2013 April 12). Retrieved from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=m5cZHhGWIIU

“800,000. Evolución de suicidios en España 1980-2013”.

93 Metros & El Español (2014).

Spanish version retrieved from: http://www.elespanol.com/documental/suicidios/#/chapters/los-supervivientes-video

Subtitled in English version retrieved from http://www.elespanol.com/documental/suicides/#/chapters/los-supervivientes-video

“Con la sangre al cuello” (2011). Video Testimonial from an activist affected by an eviction case and leading to a suicide on 8 February 2012 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=fUsZ45u1Nsw&feature=youtu.be

NOTES

1 “Mi marido se suicidó hace 20 días por los problemas económicos que teníamos. Cobraba el subsidio por desempleo, solo tenía 45 años y le decían que ya era mayor para trabajar. (…)Él decidió coger el camino más fácil y dejarnos a mí, a mis hijas y a mis nietos. Esto es una llamada para que se sepa que hay mucha gente como yo, y que me gustaría que alguien hiciera algo para evitarlo.”

2 “La crisis mata. En Italia, en Grecia... y en España. Joaquín no quería ni oír hablar de subsidios. Sólo deseaba trabajar. Dos años en paro lo sepultaron: decidió ahorcarse mientras hacía la comida para su mujer”

3 “Llevaba dos años sin nada, dos años que le robaron la autoestima. Otra vida sepultada bajo el derrumbe del sector de la construcción. Él no pedía nada más (y nada menos) que un trabajo en un país donde 4,7 millones de personas ya hacen cola en el INEM. (…) El 3 de abril algo se rompió dentro de él, en el interior de un hombre en cuyo vocabulario no existía la palabra depresión, sin un solo antecedente de problemas psicológicos y con un espíritu vitalista sin fisuras. Hasta entonces. Una semana antes había ido al banco a intentar renegociar la cuota de la hipoteca. Le iban a quedar 400 euros de subsidio después de agotar el paro y debía pagar 500 al mes por su vivienda, una casa que se había reformado con sus propias manos, en un edificio destartalado que lleva más de medio siglo en pie, y sobre la que aún pesa una deuda de 90.000 euros. El banco no dio su brazo a torcer. Y Joaquín no pudo aguantar más el pulso de la vida.”

4 Es el drama más silencioso, del que nadie quiere hablar. No provoca encendidas discusiones en televisión ni obliga a los políticos a pronunciarse. Pero el suicidio se lleva la vida de 4.000 españoles cada año. Sus familias han cargado durante siglos con un estigma que las obligaba a esconderse, como si arrastrasen una vergüenza. Algunos han dicho basta y se han agrupado para romper el tabú. No les importa compartir su dolor si eso sirve al menos para abrir un debate social. Estas son sus historias.”

5 “Las hipótesis son numerosas: un extraño compuesto químico presente en el agua, la abundancia de olivos y nogales en la zona, la altitud de dichos municipios (casi todos se hallan en la frontera de los mil metros), la existencia de un mineral llamado pirita en el subsuelo (que presuntamente provocaría alteraciones psicológicas), el aislamiento de estos pueblos, las escasas oportunidades laborales, la predisposición genética, una macabra tradición…”

6 “Antonio tenía 42 años y, aunque llevaba una década casado con su mujer, la pareja no tenía hijos. Para despedirse dejó escrita una carta estremecedora hasta el punto de que el sargento policial que se la leyó al alcalde pedáneo no pudo acabarla por la emoción.”

7 “La crisis arruina y mata. En España se producen a diario casos de suicidio ante los que los medios no informan. Se trata de no provocar alarma social y de atenuar la tragedia, se dice. De nuevo los efectos por encima de las causas. Y las causas tienen nombre y apellidos: casta política y financiera. Uno de los últimos casos ha sido el de una mujer minusválida en Málaga. La prensa ocultó el suceso, pese a la aparatosidad de su muerte, presenciada en vivo desde la calle por más de un centenar de personas.

8 “Muere la mujer que se quemó a lo bonzo en un banco al grito de: '¡Me lo habéis quitado todo!'”

9 El cura Joaquín Sánchez, miembro de la Plataforma de Afectados por la Hipoteca (PAH), lamentó ayer profundamente lo ocurrido en La Ñora y se mostró crítico. «Quienes defienden el sistema y la ley hipotecaria son criminales y tanto el Gobierno como los bancos son cómplices de esto», manifestó. El sacerdote explicó que «hay personas que, por situaciones de pobreza y vergüenza social, se encuentran indefensas y optan por medidas drásticas» y añadió que «a estas personas hay que quererlas, respetarlas y estar a su lado. Haciendo eso se evitarían dramas como éste».

10 “La primera asociación de supervivientes, Després del Suïcidi (https://www.despresdelsuicidi.org/), la fundó en 2013 Cecilia Borrás, una psicóloga de Barcelona, tras perder a su hijo Miquel, de 19 años. En Madrid ya existía desde 2009 AIPIS (http://www.redaipis.org/), creada por Javier Jiménez para actividades de prevención supliendo la carencia de programas oficiales. Cecilia y Javier han sido como dos ángeles de la guarda para cientos de personas. Han pasado –y pasan– horas hablando por teléfono con desconocidos que los llaman desesperados, sin saber otro sitio al que recurrir. Su apostolado empieza a dar fruto. Bajo su inspiración, los supervivientes de Huelva han creado la plataforma A tu Lado (http://atuladohuelvaspain.blogspot.de/). Y ya hay otros grupos en marcha para romper el silencio en Canarias, País Vasco o Galicia. Defienden que una parte de los suicidios se podría evitar. Que para ello es esencial que no se oculte el problema y que se apliquen los planes de prevención elaborados por las autoridades sanitarias, pero que apenas se cumplen.”

ANNEX

Acts of suicide related to the crisis and to eviction processes compiled by 15Mpedia ( https://15mpedia.org/wiki/Portada)