Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Acessos

Acessos

Links relacionados

-

Similares em

SciELO

Similares em

SciELO

Compartilhar

Observatorio (OBS*)

versão On-line ISSN 1646-5954

OBS* vol.11 no.4 Lisboa dez. 2017

Dealing with viewers’ complaints: Role, visibility and transparency of PSB Ombudsmen in ten European countries1

Dolors Palau-Sampio*

*Universitat de València, Spain

ABSTRACT

The article shows the results of a comparative analysis of the complaints management mechanisms offered by ten European Public Service Broadcasting (PSB) systems on their corporate websites. Using a qualitative methodology, it maps the procedures and evaluates the visibility, transparency and dissemination of results. The findings show, firstly, great diversity in terms of responsible election and management, despite the converging media governance. Also noteworthy is the margin of substantial improvement in the transparency and dissemination possibilities, specially relating to the interaction offered by the digital environment. Among the ten public corporations analysed, the BBC is the best ranked, while RAI presents the worst performance. Finally, the comparative analysis shows some correlation within the Hallin and Mancini Mediterranean model, but less are evident among the countries included in the Liberal and Democratic Corporate model.

Keywords: Accountability, Ombudsman, social responsibility, transparency, visibility, Western European Public Service Broadcasting

Introduction

The different ways to manage viewers’ complaints and requests fall within the scope of the transparency and social responsibility framework, as an opening statement towards the citizens’ supervision, indicating the quality and ultimately the credibility of the audience. Concern about these issues has been manifest since the 1940s and has increased in recent decades, as the tension between business and public service has risen (Lauk and Kus, 2012). Hodges defined ‘responsibility’ as the theoretical approach to a proper conduct and ‘accountability’ as the practice, the way of compelling it (in Bardoel, 2007: 446). However, the concept of media accountability remains far from being clear or precise (Dennis, Gillmor and Glasser, 1989; Bardoel and d’Haenens, 2004; Groenhart, 2013). It involves, as Pritchard said, “the process by which media organizations may be expected or obliged to render an account of their activities to their constituents” (2000: 2).

Media researchers have described different media accountability instruments. Bertrand considered press councils, codes of ethics, journalism reviews or ombudsmen as some of the ‘Media Accountability Systems’ (MAS), “non-State means of making media responsible towards the public” (2000: 108), the boost of which stimulated the Hutchins Commission (Commission on Freedom of the Press, 1947), that emphasised the media’s social responsibility and accountability in order to avoid state regulation. McQuail underlines this complexity, pointing out that “accountable communication exists where authors (originators, sources or gatekeepers) take responsibility for the quality and consequences of the publication, orient themselves to audiences and others affected, and respond to their expectations and those of the wider society” (2003: 19). He identifies four different types of accountability: the market, the professional, the public and the legal/regulatory type. Bardoel and d’Haenens (2004) refer to the latter as political accountability (associated to media policy and regulation) and define marketaccountability in relation to the forces of the market and audience preferences; while considering that the public and professional accountability have a self-regulatory nature. The present research pays attention mainly to public accountability, but considering the character of the PSB studied, political accountability also has an influence, at least since the setting-up is supported by legal instruments.

Public Service Broadcasting (PSB)—and particularly the TV—plays an important role in the European context “as a social and political tool, accessible to all and contributing to pluralism, diversity and democratic expression” (Iosifidis, 2007: 6), a fundamental element in the public sphere in the Habermasian sense (Dahlgren, 1995). Authors have pointed out the necessity to evolve from a PSB to a real Public Service Media (PSM) in the new multimedia environment (Jakubowicz, 2010), that involves “serious audience implications” and brings to light the concept of communication rights (Bardoel, 2007). One of them is “the right to self-expression, which includes access to channels and platforms where citizens can make themselves seen and heard, and also listened to” (2007: 61). Hasebrink, Herzog and Eilders emphasise the need to promote the voice of the viewers and increase cooperation between the representative organizations (2007: 90-91).

Hasebrink highlights that viewers are not simply consumers but also citizens, owners of rights and members of a democratic society, and proposes a change in the paradigm of audience research, in order to consider this role in different types of media governance activities (2012). Taking into consideration the viewers’ participation options, Hasebrink, Herzog and Eilders describe two models: the one available through politics, regulators or media companies and the self-regulated one, such as viewers’ organizations1 (2007: 79-80). The first model includes representation in controlling bodies, communication platforms for discussion, qualitative audience research—mostly focused on the consumers’ role—and complaint procedures (2007: 79-82). The second one is a widespread measure that exists in almost every European country, but is provided as well for broadcasters themselves, regulatory authorities and self-regulatory organs like press councils. Amongst the diversity, the Ombudsman system originating in Sweden2 represents an independent advocate or moderator. Hasebrink, Herzog and Eilders regret that usually complaints do not enter the public discussion but they consider the existence of an institutionalised procedure indispensable and value the high degree of sensitivity for viewers’ concerns. “(A)s far as they are accomplished by rules, which secure that the respective cases become public and transparent, they can contribute to civil society discourse and control in media politics” (2007: 81-82).

Theoretical background

Evolution of the Ombudsman figure: from newspapers to TV

The press Ombudsman figure appeared in 19673 to face the crisis of credibility in two local newspapers from Louisville (Kentucky, USA), The Courier-Journal and The Louisville Times. Since the late sixties, the presence of the News Ombudsman has broadened throughout the world, not only in newspapers but also in audiovisual media. The Canadian Broadcasting Corporation (CBC) created in 1992 an office to investigate complaints made by listeners (Mollerup, 2011). In Europe, the first ombudsman began operating in the Spanish regional Radio y Televisión de Andalucía (RTVA), in 1995 (Sánchez-Apellániz, 1996).

The functions attributed to the Ombudsman constitute a wide range of tasks, a complex role that demands a combination of pedagogical and critical skills but also, as the ONO4 mission statement highlights, an independent and transparent behaviour: to listen to the audience complaints, investigate them and give answers to the readers or viewers, but also to make people understand the journalistic work, to correct mistakes and improve the quality, to publish the conclusions of the most significant cases and, all in all, to act as a supervisor of the newsroom self-regulation (Bertrand, 2000; Bernier, 2003; Goulet, 2004; Evers, Groenhart and Van Groesen, 2010; De Haan and Bardoel, 2012). Even in public broadcasting corporations, as Mollerup (2011) explains, the performance is a combination of activities: barking watchdog, head of appeals, radio or TV anchor in a complaints program, mediator between audience and media, responsive representative on what is of concern to the audience and internal quality supervisor.

The Ombudsman is an atypical position, not only because of his place in the newsroom—separate from it, whilst being part of the editorial structure with a special independency—but also due to his performance in different phases of the production process (critical, preventive or encouraging professional awareness) (Elia, 2007: 21). Despite his establishment in different countries and media culture environments, the Ombudsman is still an exotic position—the Organization of News Ombudsmen (ONO) has 55 regular members from 23 countries. Reasons for this are mainly financial—this position can be seen as a kind of luxurious addition—, nevertheless, it is also possible to find managerial inconveniences related to the thread to the redactor-in-chief authority or the demoralising effect on the staff, or divergences over the effectiveness of the role (Glasser, 1999; Aznar, 1999; Evers, Groenhart and Van Groesen, 2010). A good deal of these issues are reflected in empirical research that tries to define their role between the readers and newsroom—Readers' Advocates or Newspapers' Ambassadors?, quoting Van Dalen and Deuze (2006)—or the management of relations, credibility and legitimacy (Evers, Groenhart and Van Groesen, 2010; Evers, 2012), pointing out the personality of the Ombudsman (Agnès, 2008; Bernier, 2011; Lauk and Kus, 2012).

To protect and enhance the quality of journalism is the first aim listed on the ONO mission statement. This clearly shows the demand of excellence that the accountability instruments involve, and also the narrow relationship with another concept linked to the readers and viewers’ perception: credibility. Quality and credibility are both polyhedral and elusive concepts, originally associated to the economic field as a combination of professional solvency and—more recently—social responsibility (Palau and Gómez Mompart, 2013).

In recent decades, many researchers have underlined the quality-credibility correlation in the journalistic field, mainly in the USA (Hovland and Weiss, 1951; Metzger et al., 2003; Kovach and Rosenstiel, 2001; Maier, 2005) and Germany (McQuail, 1992; Schatz and Schulz, 1992; Ruß-Mohl, 1994) but also in some Latin American countries (Freundt-Thurne, 2009; Gutiérrez-Coba, Salgado-Cardona and Gómez-Díaz, 2012).

Online Media accountability

As Bardoel and d’Haenens (2008) note, the media and particularly PSB have been reluctant to provide instruments for accountability, and only recent events have motivated a change of strategy (De Haan and Bardoel, 2011: 29). Often facing politicians and government critics, Mollerup insists that an independent, resident ombudsman—together with other mechanisms of self-regulation—is key in PSB (2011: 101). Media institutions and journalists prefer professional and public accountability mechanisms (De Haan and Bardoel, 2012: 3), but Groenhart estimates that much potential of public media accountability is wasted because professionals and companies identify it from an improvement-by-sanction perspective and subsequently reject it claiming professional autonomy (2013).

However, some scholars perceive a change in the motivations, moving from a concept rooted in the paradigm of social responsibility—more likely to see accountability instruments as a limitation—towards another focused on citizen participation—mainly as a reaction against the first one for failing to achieve the desired results (Christians et al., 2009; Von Krogh, 2012). In this sense, Groenhart observes “an emerging interest in transparency and dialogue in journalism by means of consumer loyalty and innovating journalistic practices”, that “shifts the focus from a punishment perspective towards more rewarding cooperative logics” (2013: 1). In recent years, the impact of the online MAS has focused the attention of many studies, related to issues such as participatory journalism or blogging (Domingo and Heinonen, 2008; Hermida, 2010; Singer et al., 2011). Projects like Media Accountability and Transparency in Europe (MediaAcT) incorporate online tools when mapping media accountability infrastructures and journalists’ attitudes towards media self-regulation in 14 countries (Eberwein et al., 2011). Heikkilä et al. (2012), on their behalf, analysed the emerging practices and innovations. Nevertheless, some scholars point out the concerns of verification, accountability and accuracy of some of the spaces (Fenton, 2010; Ruiz et al., 2013) or note that, despite the interesting contribution, “the technological ease of participating does not automatically create a more democratically involved citizenry” (Holt and Von Krogh 2010, 298). Others, after an international survey, are even more categorical: “(I)t becomes clear very quickly that the highly-touted online communication is in no way the new miracle cure in the general struggle for more journalistic responsibility” (Eberwein and Porlezza, 2014: 433), in line with the considerations of De Haan and Bardoel (2012: 17).

Advantages of online media accountability in terms of speed or costs could suggest that the internal Ombudsman has become an old-fashioned or irrelevant figure. Changes in candidate profiles, elimination of the post, or substitution of tasks5, all mainly justified by financial reasons, are emphasised in some studies (Evers, Groenhart and Van Groesen, 2010; Starck, 2010; Quixadá, 2010). Replacement was not the conviction of authors like Ruß-Mohl (1994: 22-23), Pritchard (2000: 186) or Bertrand, who considered that “while every existing media accountability instrument is useful, none is sufficient. None can be expected to produce great direct effects. They supplement each other” (2000: 154). Neither can the conclusion of more recent research, such as that conducted by Evers, Groenhart and Van Groesen, highlighting that, despite some trends, “there are amply sufficient points of departure to conclude that the news ombudsman contributes to fostering journalistic quality” (2010: 150).

Fengler, Eberwein and Leppik-Borg underline the advantages of audience-inclusive web-based media accountability instruments in terms of costs, efficacy and viewers’ participation (2011). Media around the world have implemented online mechanisms to handle audience collaboration as much for comments as for content contributions, voting, gaming or complaining. The aim of this article is to focus on the last interaction in order to know what kind of systems have been set up in ten PSB of Western European countries to deal with complaints. We are interested not only in who develops the functions, either an individual or a board, but also in how the complaints process is directed. Those aspects define the first research question:

RQ1: What kind of models can we identify among the variety of figures operating in Western Europe PSB?

The second aim is to characterise and classify how visible and helpful the complaint services allocated on the website of the PSB are, since they can represent an advantage in terms of provision of information, accessibility (access/contact) or transparency in respect to former options such as letters or phone calls. Besides, they can facilitate a more spontaneous contact and a pedagogical task. Finally, we will compare the data collected with the models defined by Hallin and Mancini (2004). The two last concerns are specified in the following research questions:

RQ2: To what extent does the website implement the ombudsman role and facilitate the audience access?RQ3: Are the models coherent with the Mediterranean, Democratic Corporate and Liberal systems?

Method

This article presents a qualitative desk research analysis of the online accountability instruments in ten European PSB: ZDF (Zweites Deutsches Fernsehen, Germany); BBC (British Broadcasting Corporation, UK); FTV (France Télévisions, France); RAI (Radiotelevisione Italiana, Italy); RTVE (Radio Televisión Española, Spain); RTBF (Radio Télévision Belge Francophone, Belgium); RTP (Rádio e Televisão de Portugal); ORF (Österreichische Rundfunk, Austria); SRGSSR (Schweizerischen Radio- und Fernsehgesellschaft, Switzerland) and RTÉ (Raidió Teilifís Éireann, Ireland). Considering the characteristics of some of the PSB, they have been studied as overall corporations: the three France TV médiateurs; the RTP provedor for TV and provedora for Radio; and, due to the regional organisation in Switzerland, the ombudsmen of the three most representative media—Schweizer Radio und Fernsehen (SRF), Radio Télévision Suisse (RTS) and Radiotelevisione Svizzera (RSI).

The first step in our analyses tries, among the diversity of options, to identify and categorise different models to deal with viewers’ complaints. The method combines the analysis of data included in the website sections with indirect information from legal regulatory documents and bibliography. Our first aim was to obtain direct information from those responsible for the service but only a few of them filled in our questionnaire. For that reason and in order to homogenize the gathering of data, we finally decided on an indirect process. The data collection took place between May and June 2016.

In order to answer the second research question, a datasheet with a combination of questions about the website service was designed, aiming to audit visibility on the main page, accessibility, transparency of the process, publication of results, dissemination of legal and self-regulatory documents, use of social networks or disclosure on TV programmes.

The choice of countries and public service broadcasting –one for each country– is based on two criteria: firstly, the representativeness in the country (including the state versus regional emission character) and, secondly, the accessibility to the vehicular language by the researcher. Related to the first option, in Germany the Zweites Deutsches Fernsehen (ZDF) has been chosen instead of Das Erste (ARD) and, in Spain, RTVE instead of other regional broadcasters. The second rule determined the amount of countries included, representative of Western Europe, but also the election of the Radio Télévision Belge Francophone (RBTF) instead of the Flemish Vlaamse Radio- en Televisieomroep (VRT). The Swiss SRGSSR represents a special case, since the corporation itself comprises four regional media, three of which—except the Radiotelevisiun Svizra Rumantscha—have been analysed.

Discussion

Models of procedure

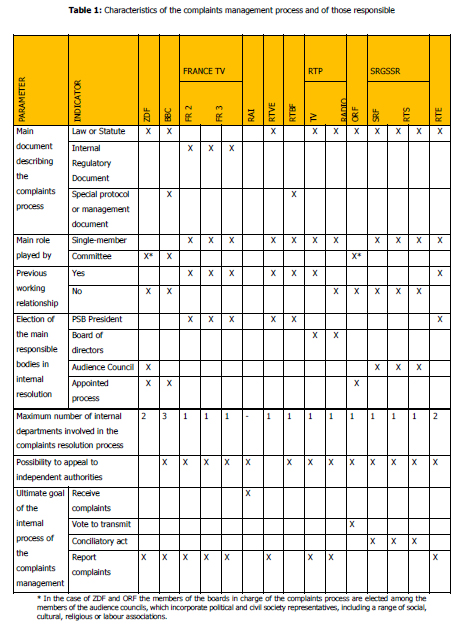

With the goal of identifying, among the highest diversity of systems, some models of handling and resolving complaints, seven parameters relating to the procedure have been analysed (see Table 1): the regulatory document, the characteristics of those responsible (single member or a committee), the existence of previous labour links, the election of the main responsible bodies, the number of departments involved in the internal process, the possibility of an external appeal and the ultimate goal of the complaints process.

Depending on the PSB, the procedure is described in a wide variety of documents, from laws (BBC, RTP, ORF, RTÉ, SRGSSR) and statutes (ZDF, RTVE) to internal governing texts (Chartre des Antennes, launched by the president of France Télévisions) or management documents (Quatrième contract de gestion de la RTBF). Together with the Royal Charter and the Framework Agreement, the BBC details their activity through different procedures. However, the RAI makes no reference to the complaints procedure, neither in the Legge Gasparri nor in the Code of Ethics.

Concerning the identity of the commissioner, the Western PSB map offers a majority of individual role players in charge of replying to viewers’ complaints: defensor del espectador in RTVE, médiateur (médiatrice) in France TV, RTBF and French-speaking Switzerland, provedor in RTP, Head of Complaints in RTÉ, mediatore in the Italian-speaking Switzerland and ombudstelle or ombudsmann—as the new responsible Roger Blum is named—in the German-speaking SRF. There is also an unidentified service—the Italian RAI, that offers an email address and a phone number to contact the Social secretariat of RAI, part of the Communications and External Affairs Department (Santori and Ferrigni 2005: 162)—or a board of members, as have three corporations that choose to implement a collegiate decision. This is the case of the ZDF and the Austrian ORF, which channels complaints through the Fernsehrat (Television Council) and the Publikumsrat (Audience Council), respectively. The BBC presents different committees, on the top of which, making the last internal decision, is the BBC Trust, “the sovereign body within the BBC” (BBC).

The last three PSB also coincide on the independent election of the members, since they do not have any previous labour relationship and should be appointed by representative entities or, in the case of the BBC, by the Queen on advice from Ministers after an open selection process. The first group is completed by the Swiss SRGSSR, whose three regional médiateurs are independent. A second group is made up of France TV, RTVE, RTBF and RTÉ, all of which with an individual role player in charge with previous working relationships and directly elected by the management responsible, even though they are autonomous, as specified in the regulatory documents. RTP constitutes a kind of hybrid, with a radio provedora without labour links and a previous anchor as a TV provedor, but unlike other Mediterranean PSB, with an election conducted by the Board of directors with the consent of the Audience Council.

The complaints handling process involves in most cases only one responsible body or department, since the complainant does not have the possibility of an internal appeal in case of disagreement. This model is typical of the most self-oriented style practiced in the PSB that created a special figure, such as the cases of Portugal, Spain, Switzerland, Belgium or France. The latter incorporated a revision system, considering the Médiateur des programmes as a kind of second internal instance for complaints, but in practice this is not clearly differentiated on the website. On the contrary, the BBC and the ZDF as well as the RTÉ propose a process involving several steps. The Irish PSB offers the possibility to contact first with the RTÉ's complaints office and, if members of the public who complain are not satisfied with the response, with the Head of Broadcast Compliance, for a review that “will always be carried out by an Editorial Manager senior to the member of staff who replied to the complaint in the first instance”6. The ZDF centralises the management of the complaints in the Fernsehrat but clearly differentiates between the first review in charge of the general manager and a second, in charge of a special commission (Programmbeschwerden) on the audience council. The BBC has designed a three step process that involves BBC Information or an editorial manager (stage 1), the BBC's Editorial Standards Board (stage 2) and the BBC Trust (stage 3), “ensuring that complaints are properly handled, and acting as a final arbiter on complaints previously handled by the Editorial Complaints Unit and divisional directors” (BBC).

Together with the internal procedure, BBC viewers in the UK can also complain to the broadcasting regulator Office of Communications (Ofcom) about public service content—except about bias or inaccuracy—, some commercial issues and Internet material. This system, with an external authority to appeal, is also available in Switzerland (Unabhängige Beschwerdeinstanz für Radio und Fernsehen, UBI (Independent Complaints Authority for Radio and Television)), Ireland (Broadcasting Authority of Ireland, BAI), Belgium (Conseil Supérieur de l’Audiovisuel, CSA (Superior Audiovisual Council)) and Austria, through the Bundeskommunikationssenat (BKS, Federal Communications Board, FCB). In France viewers can alert the Conseil Supérieur de l’Audiovisuel (CSA) (Superior Audiovisual Council) about law or regulation infractions, in Portugal the Entidade Reguladora para a Comunicação Social (ERC) (Media Regulatory Entity) and in Italy, the Consiglio nazionale dei consumatori e degli utenti (National Council of Consumers and Users)) acting within the Autorità per le garanzie nelle comunicazioni (Agcom) (Communications Regulatory Authority) attends the viewers’ complaints. In Spain, regional Audiovisual Councils are operative in Navarra (CoAN), Andalusia (CAA) and Catalonia (CAC), but none exist at state level.

Considering the ultimate goal of the internal complaints process, it is possible to differentiate between four functions: complaints reception (RAI), transference to external instances (ORF), conciliation (Swiss) or delivery of an opinion (ZDF, BBC, France Télévisions, RTVE, RTBF, RTP, RTÉ).

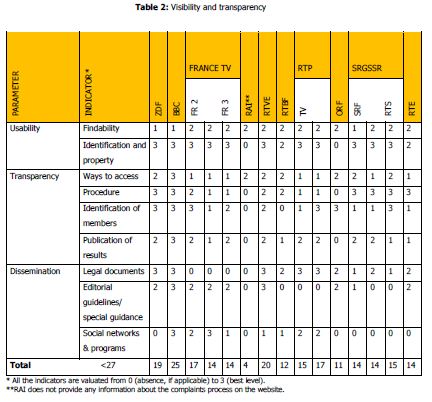

Visibility of the complaints sections

In order to define how the complaints sections are enclosed on the websites, the datasheet designed observes three main questions: usability, transparency and dissemination, all of which are itemised and evaluated on a scale from 0 (absence, if applicable) to 3 (best level). Usability is a key concept directly connected to the information architecture and navigation system, a quality attribute (Nielsen 2012) that determinates how useful an interface is. To measure this point we have analysed the findability—the quality of being locatable or navigable (Morville and Rosenfeld, 2007)—and functionality of the section. According to the character of the navigation component (front page or major section, sub-site or lower tier) and its placement (top or bottom), we have assigned a value. None of the websites analysed places this section on the most visible point, the front page. However, most of them locate it on the fat footer (value 2) or on a top or bottom sub-site (value 1).

In the functionality case, the score has been assessed taking into consideration three aspects: the clear identification, the specific use for complaints and the organisation of the section in view of the title and contents. This parameter (evaluated on a scale from 0 to 3) is revealed to differentiate, far from the placement of the section, the suitability of the service. While the BBC and ZDF place the section at a lower level, both clearly identify the objective of the division, devoted to complaining about the broadcasting contents, and offer a proper organisation of the information allocated there. The BBC not only introduces the keyword on the section label and devotes it to the announced purpose, but also clearly organises the section. On the contrary, ORF obtains good qualifications in terms of findability but fails from a functional point of view. The Austrian public broadcaster does not present a clear identification since the section is labelled with the name of one of the organs of the Austrian Broadcasting Corporation —Publikumsrat (Audience Council)—and reserves the space for the complaints committee in a sub-site, separated from the complaints formulary. The Belgian francophone broadcaster rebuilt the section in January 2015 in a more logical order.

The parameter transparency tries to evaluate the information offered in terms of access, identification of the responsible body, complaints management and publication of results. Each of these four aspects has been ranked from 0 to 3, so the maximum score for transparency is 12 points. All of the PSB, except the Swiss RSI and SRF, offer a digital formulary to complain, which guarantees the optimum management. Less common are mail addresses, phone or fax numbers together, an option that only BBC or RSI present, while the rest choose between one of them. Taking into consideration the possibilities offered by the website, in terms of information, it is noteworthy that some PSB present scarce details about the responsible body, barely the name (RTÉ) or not even that (RTBF), and some corporations present different strategies depending on the figure, as do France TV, SRGSSR or RTP. The Portuguese PSB presents an extended CV from the radio provedora in the same section and only the name and a picture from the TV provedor. In order to check the transparency of the process three aspects have been observed: the information about deadlines, about the procedure and the possibility or not to appeal, scoring a point for every item incorporated. The complete information is enclosed in BBC, ZDF, SRGSSR and RTÉ, but ORF and RTP only respond to one of them, while France TV presents a special case: the médiateur of France 2 is the only one that explains that the corporation has two first instance médiateurs (France 2 and France 3) and a third one (médiateur des programmes) that acts in second instance, although this fact is not explicit in the concerned section, not even in France 3.

The publication of results is a fundamental point to certify the transparency of the service, but not all the PSB ombudsmen assume this task or carry it out at the highest level (Hasebrink, Herzog and Eilders, 2007: 81), as the BBC does, with a variety of options that includes regular responses to recent complaints—which have either generated significant numbers of complaints or raised relevant issues—, recently upheld or resolved complaints—after referral to the independent Editorial Complaints Unit, those findings are archived in half-yearly reports—and finally, quarterly reports including the appeals to the BBC Trust about Editorial, Fair Trading, TV Licensing and other complaints. Also ranked from 0 to 3, this indicator has been valuated taking into consideration the inclusion on the website of general statistics or resolved cases, the last annual or quarterly reports and a series of them, provided that the website allows the storage. Notwithstanding that, ORF offers no information about the considered issues in the section and RTBF only includes the two last reports (after the rebuilding of the section in January 2015). Once again the differences within a PSB are notable. In France TV, the médiateur from France 2 publishes some answered questions and the most recent reports, while the médiateurdes programmes and the France 3 médiatrice barely offers the last one or two reports. The mediatore from RSI refers to some cases, in contrast with the other Swiss ombudsmann and médiatrice, which provide a series of resolved complaints and an annual report, the first, and the full set of statistics since 1991, the second. RTVE and RTP have similar strategies, supporting quarterly or annual reports and storing the series since the implementation of the figure in both countries in 2006.

The third parameter considered, the dissemination, refers to a range of options including legal and self-regulatory documents in the section but also the dissemination of the activity through social networks and programmes allocated on the website. It is important, in order to raise awareness, to make the audience know the main documents that guarantee the viewer’s rights and the self-regulatory norms imposed by the professionals to ensure compliance of the social responsibility. The legal documents considered were the laws, statutes or legal statements that regulate the procedure in the section or that are linked to others. All of these are available in ZDF, BBC, RTVE and RTP, which clearly facilitate the access to this legal background. ORF and RTBF link with the legal regulation while RTS and RTÉ only do so with some legal articles, and SRF and RSI barely mention the legislative texts relating to this activity. Neither RAI nor France TV offer information or links from the ombudsman section.

Together with the previous documents, the self-regulatory norms constitute the basis to settle the PSB performance, so it is crucial that the viewer knows them (Lauk and Kus, 2012: 171). Half of the PSB offer in the ombudsman sections the possibility to consult these rules. Taking into consideration this fact, the presence but also the findability has been valuated from 0 to 3 in this item. Once again the BBC is the most exhaustive, completing the Editorial Guidelines—the BBC's values and standards—with Editorial Policy Guidance Notes, with further explanation of their themes and practical tips. RTVE and ORF joined the programming guidelines with child protection standards while RTÉ offer only the first, consigning other self-regulatory documents in the corporate section, as RTP and two of the Swiss regional broadcasters do exclusively. ZDF, SRF and France Télévisions include these documents in a related sub-site, but not directly as a part of the complaints (Programmbeschwerden) or the ombudstelle and médiateurs section.

Media literacy is an important point in the perception and pressure for media accountability, as the Unesco (2011) and other international organisations (Celot, 2009) as well as researchers (Lauk and Kus, 2012: 171; Groenhart, 2012: 201) have noted. This is why in the dissemination section, the use of social networks or broadcast programmes has been analysed in order to contribute to the knowledge of this activity but also to promote critical thinking competences and participatory abilities. The médiateurs of France TV and provedores of RTP have a Facebook or Twitter account—sometimes both—and the BBC Trust only the latter. However, the use is very dissimilar, with a more remarkable intensity on the BBC and France 3. Together with the social networks (valuated depending on the account activation and use up to two points in Table 2), another element has been considered that has a pedagogical function, such as the dissemination of programmes dealing with the audience complaints or questions (valuated with one more point). Not all PSB broadcast these programmes7, but all that do it offer to the viewers the possibility of accessing it from a section on the website, compensating untimely transmissions. BBC and RTP have both a weekly radio and TV programme—Feedback and Newswatch, on the British broadcaster and Em Nome do Ouvinte and Voz do Cidadão on the Portuguese—while France 3 and RTVE offer the monthly spaces Votre télé et vous and RTVE responde. RTBF broadcast MediaLog, a monthly media magazine, the contents of which are devoted to answering audience questions and reactions collected by the mediation service, but not conducted by the médiatrice herself (until January 2015 it was not possible to find any link or mention in the section).

Comparative with the Hallin and Mancini model

The PSB complaints procedures analysed are only partially coherent with the Mediterranean, Democratic Corporate and Liberal systems proposed by Hallin and Mancini (2004). While we can clearly identify common traits among three of the Mediterranean PSB, the similarity between those originally included in the Democratic Corporate is not so evident when trying to define them. So in this way, RTP, RTVE and France TV opt for versions of the ombudsman role, with resolute and conclusive functions, a personality-centred profile and a pedagogical orientation, including TV programmes conducted by them. In these cases the election and professional links with the PSB are quite high, as in the Belgian RTBF. The Swiss SRGSSR share the election of a single player but with different characteristics, since in the Helvetian country the audience council makes the appointment of the ombudsman and its role has a conciliator profile.

Austria and Germany, both representatives of the Democratic Corporate system in the Hallin and Mancini classification, also left the complaints management in the hands of the audience councils but the scope of their work is quite different, because the Austrian ORF acts mainly as a filter to support complaints addressed to the Federal Communications Board. The German ZDF Fernsehrat, however, offers a complaints resolution and follows a process at various stages, inspired by the British BBC (Polenz, 2009). The Irish RTÉ, framed as the BBC within the Liberal system, shares the multistage resolution model but, instead of the British BBC Trust, the internal process does not incorporate any independent board. In addition, in both cases it is possible to find significant differences in visibility and transparency between the two representatives of the Liberal and Democratic Corporate model.

The Italian RAI, as previously noted, represents a quite exceptional case on the European PSB complaints management field, because of the lack of explanation about the process or the absence of a section on the website. In this country, framed in the Mediterranean or pluralistic Polarized Model, apart from viewers’ associations, two and oficial reports—Monitoraggio della qualità dei programmi Rai (Quality monitoring programs) and Rapporto Corporate Reputation (Rai Report Corporate Reputation)8—are responsible for supervising the compliance of the PSB standards (Santori and Ferrigni, 2005: 162).

Conclusions

Media accountability in Europe has been defined as “a highly fragmented picture” (Baldi, 2007: 18) and we can use the same expression to identify the complaints procedure established in the analysed PSB, as it is possible to find a great diversity of options, despite the converging media governance arrangements in Europe (Bardoel, 2007; Wagner and Berg, 2015). The differences concern not only the number of responsible bodies in charge but also their performance. Three of the PSB have more than one figure playing the ombudsman role—either regionally (Switzerland), for radio and TV (RTP), or for channels and contents (France Télévisions)—and the results in terms of visibility and transparency present some internal differences.

Even though the research is confined to complaint procedures, this mechanism represents an important tool in the accountability system, since it deals with viewers’ concerns on both the citizen and consumer sides (Hasebrink et al., 2007). The PSB considered in the study have implemented a particular mechanism to deal with viewers’ complaints but one can find substantial differences among the corporations, in a range between the less developed, as is the case of the Italian RAI, and the BBC, presenting the most elaborate process.

The election of staff members and their designation are critical points, in terms of independency (Hulin, 2005: 93; Van Dalen and Deuze, 2006; Evers, 2012: 241), in five PSB (RTVE, RTP, France Télévisions, RTÉ and RTBF). According to the visibility and transparency ranking, three of the ombudsmen figures meet two thirds of the criteria, but most of them barely overcome the half way point (14–17 points out of 27). Three of the PSB complaints services analysed (RAI, ORF and RTBF) do not even reach this amount.

There is also an important task in improving the commitment to media literacy in two directions. Firstly, increasing the transparency, giving regular account of the activity (Lauk and Kus, 2012) or taking advantage of the social networks and of the broadcasting programmes to engage the debate and the dialogue (Leal et al, 2012). Secondly, providing access—from the complaints sections—to legal and self-regulatory documents, besides the annual reports of activity, which contributes to a better understanding of the PSB (Glasser and Ettema, 2008; Lauk and Kus, 2012).

The results show that there is no complete equivalence between the Hallin and Mancini models and the PSB viewers’ complaints management. Although there are some Mediterranean coincidences (between France Télévisions, RTVE and RTP), the heterogeneity of models and procedures is predominant in the complaints sections of the West European PSB.

Our concern was to analyse the mechanisms implemented by ten European PSB to deal with complaints, this is, institutionalised online instruments provided by the media corporations. This means a specific area in the accountability and audience rights field. As other researchers have pointed out, we should look at accountability institutions as a system or a network of infrastructures (Ruß-Mohl in Glowacki, 2012: 287) and improve the study of the underrepresented users’ perception of media accountability (Groenhart, 2012).

References

Agnès, Y. (2008). Les médiateurs de presse en France. Les Cahiers du journalisme 18(8), 34-46. [ Links ]

Aznar, H. (1999). Comunicación responsable. Deontología y autorregulación de los medios. Barcelona: Ariel Comunicación. [ Links ]

BBC (British Broadcasting Corporation). Section 19: Accountability BBC Trust. In: Editorial Guidelines. Retrieved from http://www.bbc.co.uk/editorialguidelines/guidelines

Bardoel, J. (2007). Converging media governance arrangements in Europe. In: Terzis G (ed.) European media governance: national and regional dimensions. Bristol: Intellect Books, pp. 446-458. [ Links ]

Bardoel, J. and D’Haenens, L. (2004). Media meet the citizen: Beyond market mechanisms and government regulations. European Journal of Communication 19 (2), 165-194. doi:10.1177/0267323104042909

Bardoel, J. and D’Haenens, L. (2008). Reinventing public service broadcasting in Europe: prospects, promises and problems. Media, culture, and society 30 (3), 337-355. doi:10.1177/0163443708088791.

Béal, F. (2008). Médiateurs de presse ou press ombudsman. La presse en quête de crédibilité a-t-elle trouvé son Zorro? Alliance internationale de journalistes. Retrieved from http://www.alliance-journalistes.net/IMG/pdf/mediateur_int_exe_bat.pdf

Bernier, M.-F. (2003). L'ombudsman français de la Société Radio-Canada: un modèle d'imputabilité de l'information. Canadian Journal of Communication 28(3), 341-357. [ Links ]

Bernier, M.-F. (2011). La crédibilité de médiateurs de presse en France chez les journalistes du Monde, de RFI et de France 3. Les Cahiers du journalisme 22/23, 200-215.

Bertrand, C.-J. (2000). Media ethics and accountability systems. New Brunswick: Transaction Publishers. [ Links ]

Celot, P. (2009) (ed.). Media Literacy European Policy Recommendations. EAVI’s version. Retrieved from http://ec.europa.eu/assets/eac/culture/library/studies/literacy-criteria-report_en.pdf

Christians, C.G., Theodore, G.L., McQuail, D. et al. (2009). Normative Theories of the Media: Journalism in Democratic Societies. Urbana and Chicago: University of Illinois Press. [ Links ]

Dahlgren, P. (1995). Television and the public sphere: Citizenship, democracy and the media. London: Sage. [ Links ]

De Haan, Y. and Bardoel, J. (2011). Coming out of the ivory tower. Dutch Public Broadcasting’s accountability policy. Medien Journal 35 (3), 29-43. Retrieved from http://hdl.handle.net/2066/125904

De Haan, Y. and Bardoel, J. (2012). Accountability in the newsroom: Reaching out to the public or a form of window dressing? Studies in Communication Sciences 12 (1), 17-21. doi:10.1016/j.scoms.2012.06.005.

Dennis, E.E., Gillmor, D.M. and Glasser, T.L. (Eds.). (1989). Media freedom and accountability. New York: Greenwood Press.

Domingo, D. and Heinonen, A. (2008). Weblogs and journalism. Nordicom Review 29(1), 3-15.

Eberwein, T., Susanne, F., Epp, L. et al. (eds) (2011). Mapping Media Accountability in Europe and Beyond. Cologne: Herbert von Halem. [ Links ]

Eberwein, T. and Porlezza, C. (2014). The Missing link: Online media accountability practices and their implications for European media policy. Journal of Information policy 4: 421-443. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.5325/jinfopoli.4.2014.0421

Elia, C. (2007). Gli ombudsman dei giornali come strumento di gestione della qualità giornalistica. PhD Thesis, Università della Svizzera italiana. Retrieved from https://doc.rero.ch/record/7972/files/2007COM006.pdf

Evers, H.J., Groenhart, H., and van Groesen, J. (2010). The News Ombudsman: Watchdog or Decoy? Diemen: AMB.

Evers, H.J. (2012). The news ombudsman: Lightning rod or watchdog? Central European Journal of Communication 5 (2), 224-242. [ Links ]

Faria, J. (1998). O ombudsman e o público. Extract of the Master dissertation, Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro, Brasil. Retrieved from http://www.observatoriodaimprensa.com.br/news/showNews/mo051098.htm

Fengler, S., Eberwein, T. and Leppik-Borg, T. (2011). Mapping Media Accountability in Europe and Beyond. In: Eberwein, T., Fengler, S., Lauk, E. et al. (eds). Mapping Media Accountability in Europe and Beyond. Cologne: Herbert von Halem, pp. 7-21. [ Links ]

Fenton, N. (2010). Drowning or waving? New media, journalism and democracy. In: Fenton, N. New media, old news: journalism and democracy in the digital age. London: Sage, pp. 3-16. [ Links ]

Freundt-Thurne, U. (2009). El manejo de la confianza y la credibilidad periodísticas como activos intangibles en las empresas de comunicación. Folios 18-20, 83-93 [ Links ]

Glasser, T.L. (1999). L'ombudsman de presse aux Etats-Unis. In: Bertrand JC (ed.) L'Arsenal démocratique: Médias, déontologie et M*A*R*S. Paris: Economica, pp. 277-284. [ Links ]

Glasser, T.L. and Ettema, J.S. (2008). Ethics and eloquence in journalism: An approach to press accountability. Journalism Studies 9 (4), 512–534. doi:10.1080/14616700802114183.

Glowacki, M. (2012). Media accountability and transparency. Interview with Prof. Dr. Stephan Ruß-Mohl. Central European Journal of Communication, 5.2 (9), 285-288. [ Links ]

Goulet, V. (2004). Le médiateur de la rédaction de France 2. L’institutionnalisation d’un public idéal. Questions de communication 5, 281-299.

Groenhart, H. (2012). Users’ perception of media accountability. Central European Journal of Communication 5.2 (9), 190-203.

Groenhart, H. (2013). Improving journalism students or the profession? Five arguments for public media accountability. In: 3r World Journalism Education Conference, [ Links ] 3-5 July, Mechelen (Belgium).

Gutiérrez-Coba, L., Salgado-Cardona, A. and Gómez-Díaz, J.A. (2012). Calidad vs. Credibilidad en el periodismo por internet: batalla desigual. Observatorio (OBS) Journal 6 (2), 157-176. Retrieved from http://obs.obercom.pt/index.php/obs/article/view/564

Hallin, D.C. and Mancini, P. (2004). Comparing Media Systems. Three models of media and politics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Hasebrink, U, Herzog, A. and Eilders, C. (2007). Media users’ participation in Europe from a civil society perspective. In: Baldi, P. and Hasebrink, U. (eds). Broadcasters and Citizens in Europe: Trends in Media Accountability and Viewer Participation. Bristol: Intellect Books, pp. 75-91.

Hasebrink, U. (2012). The role of the audience within media governance: The neglected dimension of media literacy. Medijske studije 3(6), 58-72. [ Links ]

Heikkilä, H., Domingo, D., Pies, J. et al. (2012). Media accountability goes online. A transnational study on emerging practices and innovations (MediaAct working paper). Retrieved from http://links.uv.es/2Nr11lH

Hermida, A. (2010). Let’s talk: How blogging is shaping the BBC’s relationship with the public. In: Monaghan G and Tunney S (eds) Web Journalism: A New Form of Citizenship. Eastbourne: Sussex Academic Press, pp. 306-316.

Holt, K. and Von Krogh, T. (2010). The citizen as media critic in periods of media change. Observatorio (OBS) 4.4, 287-306. Retrieved from http://obs.obercom.pt/index.php/obs/article/view/432

Hovland, C.I. and Weiss, W. (1951). The influence of source credibility on communication effectiveness. Public opinion quarterly 15 (4), 635-650.

Hulin, A. (2005). France. In: Baldi, P. (ed). Broadcasting and Citizens: Viewers' Participation and Media Accountability in Europe. [ Links ]

Iosifidis, P. (2007). Public television in the digital era: Technological challenges and new strategies for Europe. New York: Palgrave. [ Links ]

Jakubowicz, K. (2010). From PSB to PSM: A new promise for public service provision in the information society. In: Klimkiewicz, B. (ed.) Media Freedom and Pluralism: Media Policy Challenges in the Enlarged Europe. Budapest: Central European University Press. [ Links ]

Kovach, B. and Rosenstiel, T. (2001). The elements of journalism. What Newspeople should know and the Public should expect. New York: Crown.

Lauk, E. and Kus, M. (2012). Editors’ introduction: Media accountability—between tradition and innovation. Central European Journal of Communication, 5.2 (9), 168-174.

Leal, F.O., Leal Filho, L. and Martins da Silva, L. (2012). Radio ombudsman services of Brazilian Public Radio (EBC) as media accountability instruments. Central European Journal of Communication 5.2 (9), 275-283.

Maier, S.R. (2005). Accuracy matters: A cross-market assessment of newspaper error and credibility. Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly 82(3), 533-551. doi: 10.1177/107769900508200304. [ Links ]

McQuail, D. (1992). Media Performance. Mass Communication and the Public Interest. London: Sage. [ Links ]

McQuail, D. (2003). Media accountability and freedom of publication. New York: Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

Metzger, M., Flanagin, A.J., Eyal, K. et al. (2003). Credibility for the 21st century: Integrating perspectives on source, message, and media credibility in the contemporary media environment. In: Kalfleisch, P. (ed). Communication yearbook 27. Mahwah: Lawrence Erlbaum, pp. 293-335. [ Links ]

Mollerup, J. (2011). On public service broadcasting and ombudsmanship. In: Unesco (ed) Professional journalism and self-regulation. New Media, Old Dilemmas in South East Europe and Turkey. Paris: Unesco, pp. 99-119. [ Links ]

Morville, P. and Rosenfeld, L. (2007). Information Architecture for the World Wide Web. Sebastopol: O’Reilly Media.

Nielsen, J. (2012). Introduction to Usability. Retrieved from http://www.nngroup.com/articles/usability-101-introduction-to-usability

Nilsson, P.E. (1986). El Ombudsman, Defensor del Pueblo o qué. In: Fix-Zamudio, H. (ed.) La Defensoría de los Derechos Universitarios de la UNAM y la institución del Ombudsman en Suecia. México: UNAM, pp. 9-21. [ Links ]

ONO (Organization of News Ombudsmen) Regular members. Retrieved from http://newsombudsmen.org/about-ono

Palau Sampio, D. and Gómez Mompart, J.Ll. (2013). La calidad como columna vertebral de la confianza en los medios. In: ICA Regional Conference, [ Links ] 18-19 July, Málaga (Spain).

Polenz, R. (2009). Nur die Befriedung von Querulanten? – Das Beschwerdemanagement des Fernsehrats. In: 2009 Themen des Jahres, pp. 57–60. Retrieved from http://www.zdf-jahrbuch.de/2009/themen_des_jahres/polenz.php

Pritchard, D. (2000). Holding the Media Accountable. Citizens, Ethics and the Law. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. [ Links ]

Quixadá, C. (2010). Newspaper Ombudsmanship in Canada: The Rise and Fall of an Accountability System. PhD Thesis, Carleton University, Canada. Retrieved from https://curve.carleton.ca/system/files/theses/30621.pdf

Ruß-Mohl, S. (1994). Der I-Faktor. Qualitätssicherung im amerikanischen Journalismus. Modell für Europa. Zurich: Edition Interfrom. [ Links ]

Ruiz, C., Masip, P., Domingo, D. et al. (2013). Participación de la audiencia en el periodismo 2.0. In: Gómez Mompart, J.Ll., Gutiérrez Lozano, J.F. and Palau Sampio, D. (eds). La calidad periodística. Teorías, investigaciones y sugerencias profesionales. Barcelona, Castellón and Valencia: UAB, UPF, UJI y UV, pp. 133-146. [ Links ]

Sánchez-Apellaniz, M.J. (1996). La nueva figura del defensor del telespectador. Comunicar 7, 68-72. [ Links ]

Santori, E. and Ferrigni, N. (2005). Italy. In: Baldi P (ed) Broadcasting and Citizens: Viewers' Participation and Media Accountability in Europe, pp. 157-177. [ Links ]

Schatz, H. and Schulz, W. (1992). Qualität von Fernsehprogrammen. Kriterien und Methoden zur Beurteilung von Programmqualität. Media Perspektiven 11, 690-712.

Singer, J.B., Hermida, A., Domingo, D. et al. (2011). Participatory Journalism: Guarding Open Gates at Online Newspapers. New York: Wiley-Blackwell. [ Links ]

Starck, K. (2010). The News Ombudsman: Viable or Vanishing? In: Eberwein, T. and Muller, D. (eds). Journalismus und Öffentlichkeit – Eine Profession und ihr gesellschaftlicher Auftrag. Wiesbaden: VS Verlag fur Sozialwissenschaften, pp. 109-118.

Unesco (United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization). (2011). Towards Media and Information Literacy Indicators. Background Document of the Expert Meeting 4-6 November 2010, Bangkok, Thailand. Retrieved from http://www.unesco.org/new/fileadmin/MULTIMEDIA/HQ/CI/CI/pdf/unesco_mil_indicators_background_document_2011_final_en.pdf

Van Dalen, A. and Deuze, M. (2006). Readers’ advocates or newspapers’ ambassadors? Newspaper ombudsmen in the Netherlands. European journal of communication, 21(4), 457-475. doi:10.1177/0267323106070011.

Von Krogh, T. (2012). Understanding media accountability. Media Accountability in Relation to Media Criticism and Media Governance in Sweden 1940-2010. PhD Thesis, Mid Sweden University, Sweden. http://www.diva-portal.org/smash/get/diva2:542409/FULLTEXT01.pdf

Wagner, M. and Berg, A.-C. (2015). Governance principles for media public services. Le Grand-Saconnex: European Broadcasting Union.

NOTES

1 Most of these organisations are grouped in the European Alliance of Listeners’ and Viewers’ Associations (EURALVA) and the European Association for Viewers’ Interests (EAVI).

2 The word Ombudsman has Scandinavian roots—it is a fusion of ombud (representative) and man (person)—, and first appeared in the Swedish Constitution in 1809, to refer—in a country exhausted by the war and the damaged harvest—to the public advocate, appointed by the Parliament to ensure citizens’ rights (Nilsson, 1986).

3 Although this is the official date recognised by the Organization of News Ombudsmen (ONO), which groups together the Ombudsmen around the world, some authors place the start in 1913, promoted by Ralph Pulitzer, who created the Bureau of Accuracy and Fair Play in The New York World (Béal, 2008). Other sources link their origin to even earlier, associated to the performance of some Japanese newspapers in the 1920s (Faria, 1998; Dorvkin, 2005). Elia (2007) contends that the character of the latter is not equitable with the current ombudsmen.

4 The mission statement and functions are detailed at http://newsombudsmen.org/about-ono

5 Patrick Pexton, the last Ombudsman of the Washington Post, was replaced by a person in charge of answering online readers’ comments: http://links.uv.es/yZbkm0W

6 The information is published at http://www.rte.ie/about/en/information-and-feedback/complaints/2012/0222/291660-complaints-procedure

7 Though not precisely a TV ombudsman programme, RAI offers since 2005 the weekly TV Talk, a magazine devoted to analyse and comment relevant TV events or controversies.

8 Reports are included on the website: http://www.rai.it/dl/rai/text/ContentItem-6ffdb289-