Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Acessos

Acessos

Links relacionados

-

Similares em

SciELO

Similares em

SciELO

Compartilhar

Observatorio (OBS*)

versão On-line ISSN 1646-5954

OBS* vol.11 no.2 Lisboa jun. 2017

Reversal of Gender Disparity in Journalism Education- Study of Ghana Institute of Journalism

Kodwo Jonas Anson Boateng*

* University of Jyvaskyla, Finland

ABSTRACT

Journalism has practically become a feminine profession across the world. To understand the root of the flow of women into the Journalism profession it is pertinent to begin at the university education level. Gallagher’s 1992 worldwide survey of female students in 83 journalism institutions reveals a significant increase in number of female students. Djerf-Pierre (2007) and others argue along Bourdieu’s conception of education as a form of social capital which empowers, enables and enhances women’s competitiveness in a pre-dominantly androgynous social arena. The study analyses 16 years of enrolment data of the Academic Affairs Unit of the Ghana Institute of Journalism (GIJ), a leading Journalism, and Communication University in Africa, to understand the growing feminization of the journalism profession in Ghana. To this end the study, employs the UNESCO gender parity index model (GPI) to ascertain the gender parity ratio of male to female students enrolled at the University. Findings indicate a significant shift in the gender parity ratio in favour of women in the journalism education.

Keywords: gender parity gap, gender equity, Ghana Institute of Journalism, journalism education

Introduction

Global trends in journalism show a marked appreciation in the number of women entering and engaged in the profession. A starting point in examining the extent of the women’s activities in journalism is Gallagher’s seminal study, and report for the UNESCO some 20 years ago. It examined gender employment patterns in the media and confirmed the ‘feminization’ of journalism (Djerf-Pierre, 2011; Gallagher, 1995). This study ascertains the gender parity ratio of enrolment of women to men into journalism training institutions in Ghana within the last 10 years. It attempts to trace how the age old gender disparity ratio in favour of men is gradually being reversed in the field of journalism in Ghana. The paper forms part of an ongoing study that aims to explore challenges and experiences of female journalists in newsroom settings across Ghana.

The influx of women into journalism is a well-studied and discussed phenomenon (North, 2014 & 2009; Hanusch, 2013 &2008; Byerly, 2011; Fahs, 2011; Gadzekpo, 2009 & 2001; Frolich, 2007; Gil, 2007; Steiner, 2007; Tusan, 2005; de Bruin, 2004; Chambers, 2004; van Zoonen, 1998; Theus, 1985). The International Federation of Journalists’ (IFJ) survey carried out in 2001 attest to the upward trend of women journalists throughout the world. Countries like Australia, New Zealand, and the Nordic countries lead the field in percentages of women working in news production and in journalism (de Bruin, 2014 & 2011; Djerf-Pierre, 2011; IFJ, 2001). For Djerf-Pierre, the Scandiniavia and Nordic ‘success stories’ in attainment of gender equality in journalism has become a challenge and a standard to emulate by most countries. The Nordic gender success story is reflected in gender mainstreaming from journalism education to journalism employment and career mobility.

So far, studies in gender equity in journalism education point to similar growth rates of influx of women. Gallagher’s 1995 survey provides insightful evidence to the extent of the achievement of gender parity in journalism training institutions worldwide. For instance, African Universities and colleges offering journalism courses are experiencing some proportionate growth trends in female to male student parity. Meanwhile, global university enrolment figures point to a high preference for journalism major for female students (Berger, 2007).

While such achievements are laudable, studies on gender equality, gender parity, and gender biases in journalism organizations, report of embedded and invisible barriers that hinder women’s progress in newsrooms, career mobility and even in accessing education (Geertsema-Sligh, 2014). Issues of power play, hegemonic and cultural/traditional relativities come into play here. Feminist perspectives like Critical Feminist Approaches consider access to education, and inclusivity in higher education for women as empowering and critical tools in minimizing male socio-economic, and political dominance, power and hegemonic control. These are also significant factors in the quest to address gender biases and inequalities inherent in all spheres of social engagement. Djerf-Pierre (2007), therefore calls for comprehensive analysis of such contributory factors that impact on gender imbalances even in academia and in journalism newsrooms.

The arguments raised in this paper discuss journalism and mass communication education institutions as integral to attempts at breaking the institutionalized male dominance in journalism education in African countries. Secondly, it examines discourse on gender mainstreaming in terms of parity in access to journalism education. The assertion here is that any gender disparities and imbalances in journalism educational institutions may directly engender and entrench gender imbalances in the journalism profession. For instance, Rush, Oukrop, Sarikakis, Andsager, Wooten, and Daufin (2005) allude to some of these systemic biases in their study of equity for women and minority junior scholars in Communication Universities. Their findings highlight pertinent scholarly narratives that go to caution and deter male scholars from studying women’s issues in journalism.

The main objective of this study therefore is to determine the parity ratio of male-female enrolment at the Ghana Institute of Journalism (GIJ). Secondly, it attempts to identify periods that female enrolment reached its peak within a 16 year period from 2000 to 2016.

The structure of the paper is as follows: a review of related literature on women in journalism education; an analysis of the ‘feminization’ of journalism and of the critical nature of journalism education in the media economy of Ghana with a brief overview of the academic structure of the Ghana Institute of Journalism (GIJ). The second half of the paper then presents the methodology and data collection techniques including analysis of the findings and conclusions.

Women studying Journalism

Women’s enrolment into journalism education is a significant aspect of broader scholarly studies on women’s work in journalism, and women’s representation in the media. Golombisky (2002) and others, for instance, have studied women’s role and enrolment in journalism education from the perspective of gender equity, gender imbalances, sexual discrimination and sexism embedded in academia.

In addition, an important starting point is the recognition of women’s role in the history of journalism education around the world. In the USA, Martha Louis Rayne of Michigan is generally acknowledged in journalism history as a pioneer in establishing journalism education specifically for women in 1886 (Beasley, 1985). However, journalism historians conveniently omit Rayne’s role in the development of journalism training and the role of women in journalism. In their paper Women in Journalism Education: the formative period 1908-1930, Beasley and Theus (1988) attempt to trace the antecedents to the feminization of journalism education. In the United States of America, women’s issues have often dominated discussions at the same pace as journalism was experiencing professionalization and ‘academisation’. In the meantime, all attempts at achieving gender mainstreaming in journalism education through creation of gender-neutral newsrooms have often met with pejorative tags - describing journalism as becoming ‘pink collar ghetto’ (Franks, 2013) or ‘velvet ghetto’ (Golombisky, 2002). It is pertinent to note that the issue of feminization of journalism has become indispensable to any general empirical study of journalism education (Nordenstreng, 2009).

Global surveys by Gallagher (1995), Peters (2013), Golombisky (2002), Densem (2006), Becker, Vlad and Olin (2009) all provide statistical evidences of the growing influx of women enrolling into journalism courses (North, 2010). According to Gallagher’s 1995 survey of 83 countries, for instance, Africa has shown significant comparative improvement in enrolment of female journalism students. In countries like Ghana and Ivory Coast in West Africa, male to female journalism student populations are almost at parity. In Egypt and Tunisia in North Africa, women make up over 80 percent of students studying journalism or mass communication at the University level.

In addition, Gender Links’ 2009 audit provides latest figures on the extent of female students in Journalism University in Southern African. According to the Gender Link’s report, 60 percent of journalism students are now women. Meanwhile only three out of the 13 countries surveyed - Malawi, Swaziland, and Mozambique - had more men than women studying journalism (Made, 2009). At the University of Zambia enrolment records indicate that about 56 percent of its first year students in the mass communication department are female students. The figure increases to 81 per cent female students when students choose their study majors during their third year of study (Nyondo, 2009).

Melki and Farah (2014) cite Melki’s (2009) study to indicate that in countries like Lebanon, in the Middle East, women currently make up two-thirds of students in journalism and mass communication departments. This is in spite of the fact that these countries are predominately-Arab countries with patriarchal cultural systems.

De Bruin (2014) among others have criticised such quantitative surveys as ‘the body count’ approaches to examining and understanding a more complex problem. Evidence of such body count however, provide valuable indicators like those from American Society Newspaper Editors’ (2005) survey that reveal that one out of two journalism undergraduates in the United States are women. Audit of member institutions of the Accrediting Council on Education in Journalism Mass Communication (ACEJMC) from 1989 to 2002 shows a widening gap in the enrolment of women in journalism. Figures from 1987 indicate that 21.4 percent more women than men studied for graduate journalism degrees in the US. By 2001, the number had increased to 34.8 percent more women than men studying journalism.

Historical data from the United Kingdom from the 1930s show a ratio of 33 women to 27 men studying journalism at the tertiary level. Enrolment figures from City University, UK indicate a ratio of 2.01:1 female to male students were studying for journalism in 2012 (Franks, 2013).

Feminization of Journalism

Conceptual discussions on feminization find roots in feminists’ arguments that emphasize the gradual transformation in socially assigned roles for the men and women. The transformative nature of feminization is particularly accentuated in the inter-play of ‘power and hegemony’ embedded in gender relations. Thus, Djerf-Pierre (2007) situates the feminization of journalism within arguments of Bourdieuian social capital perspectives.

Thus, any conceptual discussion of social capital that concentrates solely on the economics of the concept ignores certain contestable values. Such symbolic, cultural, and social values revolve round education, prestige, titles et cetera. Such fundamental propositioning conveys the enormity of women’s struggle in the access and acquisition of education as a form of social capital. It transforms, enables, and empowers women to compete equitably in a highly competitive ‘social field’ (Djerf-Pierre, 2007, p. 82).

Djerf-Pierre, therefore focuses on Bourdieu’s conception of the social field as an artificial social arena relevant to the feminism arguments. The social field/arena can be an intangible locale or institutional systems where social actors relate and compete, ultimately attaining social rewards. ‘The actors use different strategies to acquire positions and influence. What is at stake is success, prestige, status and, ultimately, the power to decide who shall be recognized as a member of the profession…’ (Djerf-Pierre, 2007, p.82).

Hence, social arenas or fields such as journalism and educational institutions are enabling tools utilized by both gender in competitive social games for acquisitions of prestigious rewards and awards of social entitlements and professional degrees. Feminist theorists discuss power in similar vein, as ‘a resource and […] a form of empowerment’ and as instrument of socio-political and economic domination. In addition, various feminist perspectives analyse social interactions between the genders in any social field, in terms of men’s sole preserve to mechanisms of power. Men have continually manipulated power, hegemony and access to scarce social, political, and economic resources that empower them to dominate competitive allocation of scarce cultural, economic, or political resources (Allen, 2014).

In certain jurisdictions, sociological approaches perceive formal education as a scarce social resource. Sociologically, formal education imbued with transformative, developmental, and empowering qualities that enhance competitiveness in some social systems. Consequently, formal education becomes one key indicator of socioeconomic advancement and a means of social and economic success. According to Philips (2013), Apple (1990) classified education and schools not only as arenas for transmission of knowledge but also ‘[…] a form of cultural capital that comes from somewhere that often reflects the perspectives and beliefs of powerful segments of our social collectivity [….]’. Hence, social and economic values already embedded in the political and social institutions, form the basis of ‘formal corpus of school knowledge’ (Phillips, 2013).

Rice (1999) re-emphasises Martin’s (1999) influential role in analytic discourses on feminists’ contributions to the philosophy and theoretical developments of education. Martin’s seminal argument relates to conscious or unconscious attempts to blackout the ‘ideas and experiences’ of women in education. Such historical erasure of memories of contributions by social minorities, like women, invariably affects any analysis of gender inequalities. Radical feminists therefore, tend to fixate on the inherent social inequalities and on patriarchal nature and dominance of the male gender in formal and institutional ‘production of knowledge’ (Rice, 1999). Unlike other feminists’ perspectives, radical feminists theorize the ‘sexual politics of schooling’, by examining entrenched historical inequalities, imbalances, and insidious discriminatory biases deep-rooted in contemporary educational systems, that call for radical means of elimination (Mendick & Allen, 2013).

For socialist feminists, contemporary educational systems are patriarchal in nature but are also a manifestation of gender inequality and an entrenchment of capitalistic political economic system. Along these lines of thinking, Ferguson (2004) also examines Rubin’s (1975) stance that stages in capitalist development prompt transition moments enable women to move into the productive work systems. These transition periods allow women to transit between housework and formal wage earning employment at different stages or during the swings in the capitalist market economies (Ferguson & Hennessy, 2010). Consequently, Rubin’s statement fits the phenomenon of growing feminization of journalism education or the production of knowledge systems.

Rubin further points to the extent women can access education and parity of male-female ratio in formal educational systems. As men continue to dominate access to educational institutions, the resulting consequence becomes obvious at the workplace. Radical feminists therefore argue for and recommend that educational and training institutions must aim at gender equity and parity in education, especially at the tertiary level to empower women compete equitably in other social arena.

Therefore, governments and multilateral organizations have attempted to intervene to achieve gender equality and gender parity at all levels of education. For instance, Goal 2 of the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs), and the Goals 2 and 3 of the Dakar Framework of Action of Education for All – EFA – are typical instances of international multilateral initiatives aimed at eliminating gender inequalities and achieving gender parity.

The twin key concepts of gender equality and gender parity aim at the eventual elimination of innate inequalities and discriminations at all levels of formal education. Any critical analyses of these concepts show some distinguishing but inter-related features. Gender equality goals are achievable on the corresponding successful achievements of gender parity goals. Gender equality therefore underscores the equal rights of access to and participation in education with the principle goal of ‘ensuring equality between boys and girls’. It further emphasizes the idea of ‘sameness’ of sexes … “as well as rights within education gender-aware educational environments, processes, and outcomes, and rights through education meaningful education outcomes that link education equality with wider processes of gender justice” (Subrahmanian, 2003, p. 2)

On the other hand, gender parity compliments efforts at achieving gender equality by providing measurements that Subrahmanian describes as ‘numerical concepts’ that quantify the extent of gender access and participation at all levels of education within certain timelines. “… gender parity tell us about the ‘peopling’ of institutions of education by gender, and indicate whether men and women, boys and girls are represented in equal numbers. Thus the right ‘to’ education is measured in terms of access, survival, attendance, retention, and to some extent transition between levels of education” (Subrahmanian, 2003, p. 8). However, this study focuses on the measuring parity in terms of access within a given period.

Media economy and Journalism Education in Ghana

Karikari’s (2007) overview of African media since Ghana’s Independence posits that the current African media policies tilt towards neo-liberal thinking. Studies of Africa’s media landscape confirm the impact of the neo-liberal shifts even in journalism education. The African media systems are presently highly privatized with less state interference and control (Skjerdal, 2011). In addition, various African Barometer Reports on Ghana (2011 & 2013) place the country at the forefront of Africa’s efforts at media liberalization, media pluralism, and diversification.

Utuka (2008) and Karikari (2007) among others point to the sweeping waves of democratization in Africa in the 1990s and particularly the impact of 1991 UNESCO Windhoek Declaration that prompted media freedoms and private media operations. Article 2 and 3 of the Windhoek Declaration called for media pluralism and encouraged private business participation in information production and dissemination (Declaration of Windhoek- 3 May, 1991).

Meanwhile, a liberal economic atmosphere further encouraged participation of entrepreneurs, and religious bodies in provision of commercial university education in Ghana. As at 2014, the National Accreditation Board of Ghana had granted 67 private universities licences and accreditation to offer university level courses. In addition, 15 public-funded universities and professional institutions operate offering undergraduate and graduate level education. A majority of these universities offer journalism, and communication related courses (National Accreditation Board).

In Ghana, access to University level education is unrestricted. Gender discriminatory policies or legislation, especially those barring girls from any form or level of education are non-existent. The Government of Ghana education policy initiatives like the Free Compulsory Universal Basic Education – FCUBE-provides fee free basic education for children. Volume two of the government of Ghana Education Strategic Plan of 2010-2020 highlights the need to achieve gender parity in second cycle and technical education enrolment by the end of 2018. (Ghana Ministry of Education, December 2010)

UNESCO’s statistics reveal that over 2.5 million Ghanaian students pursue studies at diploma, degree, and post- graduate levels of education. As at 2010, Ghana had 65.3 per cent female adult literacy and 83.2 percent female youth literacy. Meanwhile, gross enrolment ratio of female to males in tertiary institutions stood at 11.1:17.6 as at 2013 (UNESCO Institute of Statistics 2014). Female dropout rates in tertiary institutions is rather high due to incidences of early marriages and teenage pregnancies. Nyondo (2009) attributes this trend to socialization processes in most African communities that tend to malign women who pursue formal education, ‘…females who pursued any formal education were even labelled prostitutes’ (Nyondo, 2009, p. 5)

However, economic factors play a major role, acting as impediments to women accessing higher education. For instance, the ‘ability to pay’ and cost-sharing’ policies introduced as a result of the Ghana government’s cost cutting measures contribute to impeding women’s access to University education. It is pertinent to point out that in Ghana tuition is however free in all public funded universities (Utuka, 2008).

Ghana Institute of Journalism – GIJ

The study uses the Ghana Institute of Journalism as a case for study. The Ghana Institute of Journalism (hereafter GIJ), the foremost journalism educational institution in Africa was established in 1959 with the initial mandate to offering professional diploma certificates in Journalism and Public Relations ‘toward the development of a patriotic cadre of journalists to play an active role in the emancipation of the African continent’ (Ghana Institute of Journalism, 2015).

GIJ initially offered a two-year professional diploma certificate in Journalism, and trained reporters, stringers, and media and public relations officers. The Institute is reputed to have trained over 60% of journalists in Ghana. In 2006, a Parliamentary Act 717 granted the Institute autonomy to operate as an autonomous public university awarding its own Bachelor of Arts degrees in Communication Studies. Students can major in Journalism and Public Relations. In 2013, the Ghana National Accreditation Board (NAB) granted the Institute accreditation to award post-graduate Master of Arts degrees in Journalism, Public Relations, Media Management, and Development Communication, under the School of Graduate Studies and Research - SOGSAR (Ghana Institute of Journalism, 2015).

As of 2014/2015 academic year, 3012 students enrolled at the GIJ. The student population were fall within these programme categorises:

- Two-Year Diploma Courses in Communication Studies

- Four-Year Bachelor of Arts Degree Programme in Communication Studies

- Two-Year Top-up (Evening/Weekend) Bachelor of Arts Degree Programme for students with diploma and working experience

- 12-month postgraduate Masters Programme in Communication Studies

(Ghana Institute of Journalism, 2015)

Other journalism training schools include the public-funded University of Ghana’s School of Communication Studies established 1972 and privately owned Jayee University College, University of Winneba and the African University College of Communications.

Approach and method

The approach to this study consists of identifying appropriate enrolment data set over a period; analysing and processing data to estimate the parity gap and male-female ratio. Finally, it attempts to identify trends and peak periods in the parity gap since 2000.

Convenience sampling technique was therefore used to extrapolate data from over 50 years of composite data set of the Academic Affairs Unit of the GIJ. However, and typical of most African educational institutions, GIJ faces challenges related to record keeping and archiving of students data. The University lacks a comprehensive, digitalized, and computerized filing and retrieval system for managing students’ data. Record Management System for the University is traditional, utilizing old paperback files, filing systems store, archive of critical student data, and records. The filing system still employs manual data retrieval systems with files arranged on shelves and in boxes. These challenges impair any systematic process in retrieving pre-2000 data.

With these challenges and as Salkind (2010) argues convenient sampling could be an appropriate sampling method to enable the selection of relevant sample out of population that are often difficult to access. In this study, it became obvious that the stated challenges posed inconvenient difficulties in data collection. However, data from year 2000 was easily accessible and offered a convenient means suitable for the objectives of the study.

Data set for diploma students enrolled in the year 2000 and graduating in 2017 was easily available. Data for undergraduate students between 2003 until 2013 was also difficult to access. Thus, two separate sets of data of students studying for two-year professional diploma and those for four-year Bachelor of Arts degrees are analysed.

Empirical model

To measure the gender parity ratios for male and female students, the study adopts the UNESCO Institute of Statistics model for Gender Parity Index – GPI (United Nations Statistics Division:Department of Economic and Social Affairs). United Nations agencies like the UNICEF, UNESCO, and other international agencies including the World Bank use the GPI as determinant models for measurement and ascertaining the parity ratio for enrolment of boys and girls in education in various countries.

FHI360, an international Educational Policy and Data Center, describes the GPI as “Measures of gender parity in education help to explain how participation in and opportunities for schooling compare for females and males” - (See more at http://www.epdc.org/topic/gender-parity-indices#sthash.U9sRlNGv.dpuf)

The GPI measures the ratio of male to female or the number of female students enrolled at various levels of education to the number of male students at similar levels. “A GPI of 1 indicates parity between the sexes; a GPI that varies between 0 and 1 typically means a disparity in favour of males; whereas a GPI greater than 1 indicates a disparity in favour of females” (United Nations Statistics Division:Department of Economic and Social Affairs).

Thus, GPI is expressed as the:

Findings and Analysis

GPI at diploma level

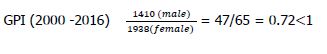

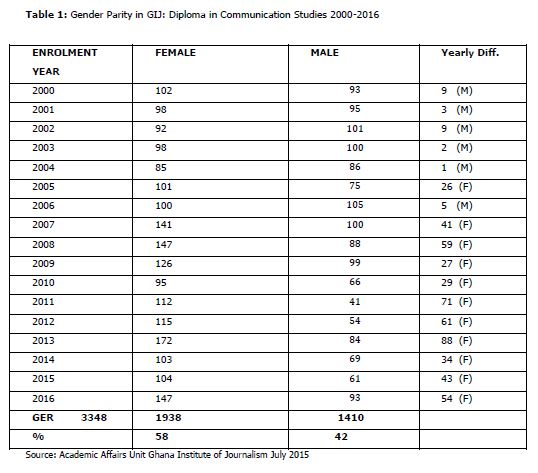

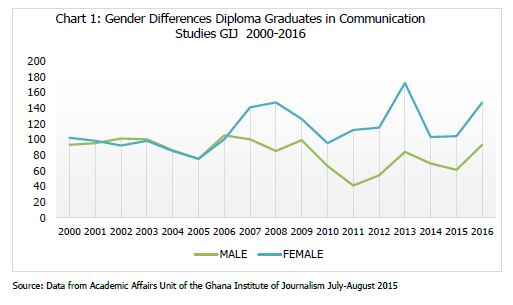

From 2000 to 2016, the Gross Enrolment figures of diploma students at GIJ from (see Table 1) stands at 3348. While, Gross Enrolment figures of female students for the same period is 1938, that for male students is 1410.The Gross Enrolment Rate for male to female or male to female ratio was 47:65. Therefore calculating for Gross Parity Index:

The Gender Parity Index therefore, indicates a disparity in favour of female students at GIJ at the diploma level for the period between the years 2000 to 2016. The male to female ratio at the diploma level at GIJ for the same period stands at 1:1.53.

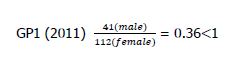

The disparity ratio narrows slightly in 2010 to a ratio of 1:1.43 female students; however, by 2011 to 2013 the percentage ratio had increased significantly in favour of female students. Figures from 2010 to 2013 show a 70% increase in female enrolment for professional diploma in communication studies. Meanwhile, data show (see Table 1) that 2011 recorded the highest enrolment figures for the 16 years. By 2011, there were thrice as many female students for every male student registered to student for a professional diploma. The Gross Parity Index shows a disparity in favour of female students.

The disparity rate shows a significant increase from 2011. Table 1 and chart 1 shows that still twice as many female students enrolled at the professional diploma than male students a ratio of 1:1.90 female students. chart 1 displays the annual parity gap trends over the 16-year period. The chart shows that the enrolment numbers of female student population begun to ascend from 2007 onwards.

chart 1 further indicates the male and female enrolment gap from 2000 was at a low level with the widest disparity of only nine male students than female students. However, the parity gap begun to widen in favour of women from the year 2007. For instance, with a gap of 41 female students in 2007, the gap increased and widened to 88 students in 2013.

GPI AT UNDERGRADUATE LEVEL

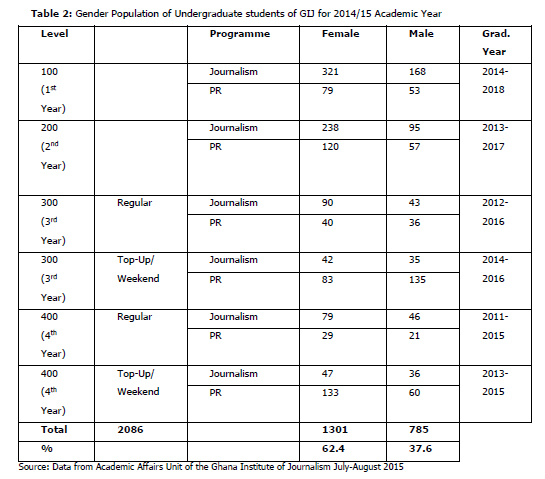

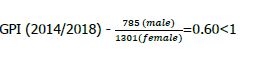

At the undergraduate level, (see Table 2) 2086 students were studying for Bachelor of Arts degree in Journalism and Public Relations for the 2014/15 academic year. Of this figure, 1301 students were females, making up 62.4 percent of the entire registered student body. Significantly, the figures indicate that there are over 500 more female students than male in the Institute for the academic year 2014/15.

Gross Enrolment Indicators (see Table 2) for aggregate population of undergraduate students at GIJ was 2086 for the 2014/2015 academic year. The number comprises of Journalism and PR major students. As Table 3 indicates 59% or 1237 of the gross population of Bachelor students intend to major in Journalism. Table 2 further indicates that female students make up 62.4 percent of the proportion of combined population of PR and Journalism students; this gives a proportional ratio of 1:1.65 male to female students enrolled.

The GPI indicates a disparity in favour of girls taking Bachelor of Arts degree in Communication studies at GIJ.

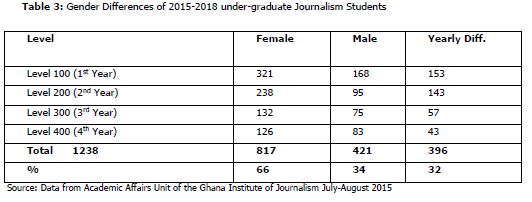

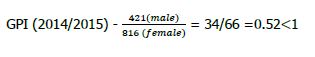

The GEI for journalism major students (see Table 3) for the 2014/2015 were 1237 students the academic year. Gross Enrolment for male students stand at 421 to 816 female students, a ratio of 66:34.

The GPI for the 2014/2015 academic year shows a significant level of gender disparity in favour of female students.

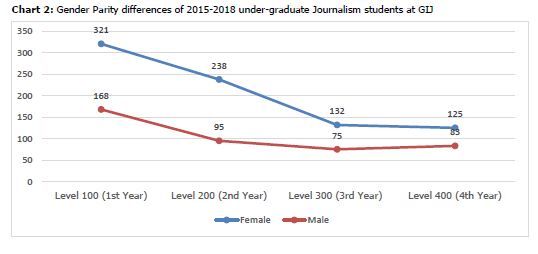

Analysis of data from Table 2 indicates that of the 208 final year Journalism students enrolled in 2011 and 2013 graduating in 2015, 61% are females. Women make up 62% of the 210 third year Journalism undergraduate students admitted in 2012 and 2014 who intend to graduate by 2016. While, female students make up 70% of 333 second year journalism undergraduates to graduate in 2017. Female students also make up 66% of the 489 first year journalism students enrolled for the 2014/2015 academic year at the undergraduate level.

Table 2 gives gross enrolment figures of students for PR and Journalism for 4-year Bachelor of Arts degree. As the table indicates, over 2086 students are enrolled at the GIJ at the bachelor level. The Gross Enrolment levels of Journalism (see Table 3) students stand at 1237, 59 percent of the entire population of students at the Bachelor level of study for the 2014/15 academic year. It is pertinent to explain that as indicators in chart 2 show that any significant increase in students’ enrolment population triggers a corresponding growth in the gender gap in favour of women’s enrolment. Analysis of chart 2 shows, for instance, that the male-female ratio for final year Journalism enrolled in 2011 to graduate in 2015 is 1:1.5. The parity gap widens slight to a ratio of 1:1.76 male to female for third year students enrolled in 2012 to graduate in 2014. Further analysis show a significant growth in the gender parity gap for second and first year students at the Institute. The ratio grows significantly to 1:2.50 male to female journalism students in the second year. However, chart 3 indicates a slight decrease in the male: female ratio of 1:1.91. The aggregate male: female ratio of first to final year journalism students registered to study in the 2014/2015 academic year is 1:1.93.

Available figures (see Table 2) provide indications that even the Public Relations profession may experience similar feminization. Evidence from Table 2 point to a disparity in the gender gap at the undergraduate level skewed toward female students. For instance, the aggregate student population enrolled for PR from 2011/12 academic year until 2017/2018 year show 398 males students to 484 females making a ratio of 1:1.21

Table 2 also shows the number of students offering Journalism and Public Relations as a major. The table indicates that female students make up 66 percent compared to men offering journalism for the 2014/15 academic year.

Data of the students for post-graduate studies had yet to be compiled at the time this fieldwork was carried out.

Conclusion

This study set out to trace the growing feminization of journalism by analysing enrolment figures students’ data sets of the Ghana Institute of Journalism. The two-fold objective of the study was to determine the parity ratio of male-female enrolment at the Ghana Institute of Journalism (GIJ) and to identify periods that female enrolment reached its peak within a 16 year period.

Empirical data was gathered from enrolment records of the Academic Affairs Unit of the GIJ, a leading journalism training University in Accra, Ghana. The indicators confirm and affirm the hypothesis of the growing feminization of the journalism profession and the gradual erosion of the numerical strength of men in the journalism profession. It also confirms the findings, conclusions and assertions of studies by Byerly (2011), International Federation of Journalists (2009), Jones-Ross et al. (2007), Gallagher (2014, 1981 & 1995), and Rush et al. (2005).

It is also pertinent to point out that the progressive admission of women into journalism education are not deliberate institutional policies by the GIJ but a result of interventions by national and international development agencies aimed at achieving gender parity at all levels of educational cycles. Intervention initiatives like the Gender Affirmative Education Sector policy incorporated in the state’s Free Compulsory Universal Basic Education (FCUBE) mandate; the Gender Parity in Second Cycle and Technical Education by 2018 and the establishment of the Girls’ Education Unit in 1997 have all contributed to the increase of female students at the tertiary level of education.

Interestingly, for media and journalism practice, despite Ghana’s National Media Policy which emphasizes much on plurality and diversity, the policy is particularly silent on mainstreaming of gender or issues to do with eliminating gender inequalities or discrimination even in newsrooms. However, Article G of the policy call on broadcast media operations to: “Show a high sensibility to the dignity and respect of womanhood and defend and protect women’s rights and interests” (National Media Commission, n.d.).

Meanwhile, the feminization of journalism and the reversal of entrenched gender disparities in education can be partly explained by the preference of girls for courses in the arts, humanities, social sciences, education and health care. Audit studies conducted for the Ghana Country Profile 2013 Final report funded by the Japan International Co-operation Agency (JICA) indicate that of the 33 per cent of female studying in 2009/10 academic year, a majority were registered in the health sciences, education, liberal arts, humanities and social sciences (M&Y Consultants Ltd. 2013, p.33). Similar trends pertain in most African countries. This trend is not confined to Ghana’s educational system. Results of empirical surveys carried out in South African for instance, indicate low enrolment levels of girls into faculties of natural sciences. (Sader et al., 2005).

Bradley (2000) studying gender differentation by academic disciplines found that despite impressive progress of women’s enrollment into University education, women still gravitate toward arts and humanities instead of natural science studies. “Educational choices also build on normative assumptions that associate so-called feminine values with fields, such as the humanities and arts, and masculine values with business, the natural sciences, mathematics, and engineering”(Bradley, 2000, p. 4). Feminist theorists and thinkers however, give philosophical explanations to the low level of women in natural science studies. Barr and Birke (1998) attribute this to the systemic and unconscious efforts at ignoring women’s peculiar learning and social needs.

There are expectations that the high levels of female enrollment in journalism training institutions can enable profound transformations in the journalism profession. However, this numerical strengths may not engender fundamental structural or systematic changes if ‘entrenched male privileges’ in newsrooms are not radically challenged (Ross & Carter, 2011; North, 2010 p.111; van Zoonen, 2002). This notwithstanding, Geertsema-Sligh (2004) points to the significance of journalism as an ‘agent of change’ ....” thus any interventions meant “to transform gender relations in media….need[s] to start with the journalists of tomorrow".

The high enrolment of women into journalism may not also translate into high females journalists in newsrooms. Gallagher’s 1995 survey for UNESCO concluded from findings that most young female journalists tend to experience ‘career interruptions’ in other to tend to family obligations such as marriage, childbirth and childcare (van Zoonen,1998). In addition, anti-social work schedules put undue strain on married and child caring female journalists, contributing to high attrition rates of female journalists from the profession (International Federation of Journalists, 2009). This confirms to a large extent Rush’s (1989, 2004) Ratio of Recurrent and Reinforced Residuum (R3) hypothesis. The R3 provides a holistic explanation of this phenomenon and predicts that in spite of the numerical strength of female journalism students few transfer directly into the profession. Valenti (2015) therefore emphasizes the need for formulation of progressive policies that obligate men to share the burden of childcare and domestic unpaid work. Such policies can safeguard the successful gains of gender equality and gender parity at workplace.

Finally, it is pertinent to link the findings of the study to the eighth goal of the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals achievable by 2030 which aims to “Promote sustained, inclusive and sustainable economic growth, full and productive employment, and decent work for all” (Sustainable Development Knowledge Platform, 2015). For successful achievement of these ideals, educational and professional bodies and associations must formulate viable policies that eradicate gender-based discrimination in education while including mainstreaming gender issues in journalism education curricula to sensitize and create awareness about the social and economic essence gender parity and gender diversity in society.

References

Africa Development Bank. (2008). Ghana Country Gender Profile.

Allen, A. (2014, Summer). "Feminist Perspectives on Power". Retrieved from The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy: http://plato.stanford.edu/archives/sum2014/entries/feminist-power/

Anderson, E. (2015, Winter). Feminist Epistemology and Philosophy of Sciences. (E. Zlatna, Ed.) Retrieved September 12, 2015, from Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy: http://plato.stanford.edu/archives/fall2015/entries/feminism-epistemology/

Applegate, E., Bodle, T. J., Farwell, M. T., & Livigston, R. (2011, Summer). A Fifteen-year Census of Gender-based Convention Research: Scholarship Rates by Women in AEJMC Divisions, Interest Groups, and Commissions (1994 to 2008). Journalism & Mass Communication Educator, 66(2), 134-159. [ Links ]

Asare, A. (2015, August 19th). National Gender Policy Receives Cabinet Approval. Retrieved from Modern Ghana: http://www.modernghana.com/news/637441/1/national-gender-policy-receives-cabinet-app.html

Barr, J., & Birke, L. (1998). Common Science? Women, Science and Knowledge . Bloomington, Indiana: Indiana University Press. [ Links ]

Beasley, M. H. (1985). Women in Journalism Education:The Formative Period 1908-1930. Paper presented at the Annual Meeting of the Annual Meeting of the Association for Education in Journalism and Mass Communication August 3-6 1985 (p. 23). 68th, Memphis, Tennesse: Education Research Information Center.

Bradley, K. (2000, January ). The Incorporation of Women into Higher Education: Paradoxical Outcomes? Sociology of Education, 73(1), 1-18. [ Links ]

Byerly, C. (2011). Global Report on the Status of Women in News Media. Washington D.C: International Women's Media Foundation. [ Links ]

Cheater, A. (1986). The Mode and Position of Women in Pre-Colonial and Colonial Zimbabwe. Zambezia, XIII, 65-79. Retrieved from http://archive.lib.msu.edu/DMC/African%20Journals/pdfs/Journal%20of%20the%20University%20of%20Zimbabwe/vol13n2/juz013002002.pdf

De Bruin, M. (2014). Gender and newsroom cultures. In A. V. Montiel (Ed.), Media and Gender:A Scholarly Agenda for the Global Alliance on Media and Gender. Paris: UNESCO. [ Links ]

Declaration of Windhoek: 3 May, 1. E.-s.-1. (1991, May 3). Declarations of Promoting Independent and Pluralistic Media. Retrieved from Windhoek 1991 Declaration : http://www.unesco.org/webworld/fed/temp/communication_democracy/windhoek.htm

Djerf-Pierre, M. (2007). The Gender of Journalism: The Structure and Logic of the Field in the Twentieth Century. Nordicom Review(Jubilee), pp. 81-104.

Fahs, A. (2011). Out of Assignment: newspaper women and the making modern public space. Capital Hill: University of North Carolina Press. [ Links ]

Fallon, K. M. (1999). Education and Perceptions of Social Status and Power among Women in Larteh, Ghana. Africa Today, 46(2), 67-91. [ Links ]

Ferguson, A., & Hennessy, R. (2010, October 1). Feminists Perspectives on Class and Work. (E. N. Zalta, Ed.) Retrieved August 15, 2015, from Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy: http://plato.stanford.edu/entries/feminism-class/#4

Gadzekpo, A. (2009). African Media Studies and Feminist Concerns. Journal of African Media Studies, 1(1), 69-80. doi:doi: 10.1386/jams.1.1.69/1 [ Links ]

Gadzekpo, A. (2013). Ghana: Women in Decision-Making, New Opportunities, Old Story. In C. M. Byerly (Ed.), The Palgrave International Handbook of Women and Journalism (pp. 371-). UK: Palgrave McMillan. [ Links ]

Gallagher, M. (1995). An Unfinished Story: Gender Patterns in Media Employment (Reports and Papers on Mass Communication 110). Paris: UNESCO Publishing. [ Links ]

Geertsema-Sligh, M. (2014). Gender Mainstreaming in Journalism Education. In A. V. Montiel (Ed.), Media and Gender: A Scholarly Agenda for Global Alliance for Media and Gender (pp. 70,73). Paris: UNESCO. [ Links ]

Gender Links for Equality and Justice. (2010). Gender and Media Baseline Study. Retrieved October 20, 2014, from http://www.genderlinks.org.za/page/media-gender-and-media-baseline-study

Ghana 1992 Constitution. (1992). Ghana Publishing Corportation.

Ghana Institute of Journalism. (2015, September 7). About GIJ-Overview. Retrieved from Ghana Institute of Journalsim: Specialised Communications University: http://web.gij.edu.gh/index.php/about-gij/about-gij-overview

Ghana Institute of Journalism. (2015). Ghana Institute of Journalism. Retrieved September 10, 2015, from http://web.gij.edu.gh/

Ghana Ministry of Education. (December 2010). Education Strategic Plan 2010-2020 ESP Volume 2 -Strategies and Work Programme. Accra: Ministry of Education. [ Links ]

Holmarsdottir, H. B. (2013). Moving Beyond the Numbers: What Does Gender Equality and Equity. In H. Holmarsdottir, V. Nomlomo, A. Farag, & Z. Desai, Gendered Voices: Reflections on Gender and Education in South Africa and Sudan (Vol. 23, pp. 11-24). Rotterdam/Taipei, The Netherlands: Sense Publishes. [ Links ]

International Federation of Journalists. (2009). Gender Equality in Journalism. Brussels: International Federation of Journalists. [ Links ]

Jones-Ross, F., Carolyn, A. G., Linda, F., Dates, J., Chetachi, E., & Evonne, W. (2007, Spring). Final Report of a National Study on Diversity in Journalism and Mass Communication Education Phase II. Journalism and Mass Communication Educator, 62(1), 10-26. [ Links ]

Karikari, K. (2007). Africa media since Ghana's Independence. In E. Barratt, & G. Berger (Eds.), 50 Years of Journalism: Africa media since Ghana's Independence (pp. 9-20). Johannesburg, South Africa: The African Editors' Forum, Highway Africa and Media Foundation for West Africa. [ Links ]

Korokiewicz, M. (n.d.). Gender Parity Index. Statistical Capacity Building Workshop (pp. 1-9). Pattay: United Nations Institute of Statistics. [ Links ]

M&Y Consultants Ltd. (2013). Country Gender Profile: Republic of Ghana Final Report. Accra Ghana: Japan International Co-operation Agency (JICA). [ Links ]

Made, P. A. (2003). Gender and Media Baseline Study: Southern African Regional Overview. Johannesburg,: Media Institute of Southern Africa (MISA) and Gender Links. [ Links ]

Made, P. A. (2009). Audit of Gender in Media Education and Journalism Education Training at the Polytechnic of Namibia and University of Namibia. Gender Links for Equality and Justice, Gender and Media Diversity Centre,MDG Achievement Fund.

Melki, J., & Farah, M. (2014). Educating Media Professionals with a Gender and Critical Media Literacy Perspective: How to battle gender discrimination and sexual harrassment in media workplace. In A. V. Montiel (Ed.), Media and Gender: A Scholarly Agenda for the Global Alliance on Media and Gender. Paris: UNESCO. [ Links ]

Mendick, H., & Allen, K. (2013, January 15). Gender and Education Assoication. Retrieved August 20, 2015, from http://www.genderandeducation.com/resources/contexts/feminism/

National Accreditation Board, G. (n.d.). National Accreditation Board, Ghana. Retrieved November 16, 2015, from http://www.nab.gov.gh

National Media Commission. (n.d.). National Media Policy. Accra: Nationa Media Commission.

Nordenstreng, K. (2009). Soul-Searching at the Crossroads of European Journalism Education. In G. Terzis (Ed.), European Journalism Education (pp. 511-515). Bristol, UK. Chicago, USA: Intellect.

North, L. (2009). The Gendered Newsroom: How Journalists Experience in the Changing World of Medi. Creskill, NJ: Hampton Press. [ Links ]

North, L. (2010, January). The Gender ‘problem’ in Australian Journalism Education. Australian Journalism Review, 32(2), 103-115.

Nyondo, R. (2009). Career Choice for Female Journalism Students: A Case Study of Zambia. In R. Brand (Ed.), Focus On Fame (pp. 4-6). Konrad Adenaeur Stiftung and WITS Journalism. [ Links ]

Okunn, C. (1992). Female Faculty in Journalism Education in Nigeria:Implications for the Status of Women in Society. Africa Media Review, 16(1), 47-58. [ Links ] Retrieved November 14, 2014

Peters, J., & Tandoc, E. C. (2013, October 8). "People Who Aren't Really Reporters At All, Who Have No Professional Qualifications"?: Defining A Journalist And Deciding Who May Claim the Privileges. NYU Journal of Legislation and Public Policy Quorum. New York, New York, USA: 2013-14 Editorial Board of the N.Y.U Journal of Legislation and Public Policy. Retrieved November 20, 2014, from http://www.nyujlpp.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/03/Peters-Tandoc-Quorum-2013.pdf

Phillips, D., & Siegel, H. (2013, Winter). Philosophy of Education. (E. N. Zalta, Editor) Retrieved August 14, 2015, from The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy: http://plato.stanford.edu/archives/win2013/entries/education-philosophy/

Rice, S. (1999, July 6). Feminism and Philosophy of Education. Retrieved August 20, 2015, from http://eepat.net/doku.php?id=feminism_and_philosophy_of_education

Ross, K., & Carter, C. (2011). Women and News:A Long and Winding Road. Media, Culture and Society, 33, 1149-1165. [ Links ]

Rush, R., Oukrop, C. E., Sarikakis, K., Andsager, J., Wooten, B., & Daufin, E.-K. (2005). Junior Scholars in Search of Equity for Women and Minorities.

Rush, R., Oukrop, C., & Sarikakis, K. (2005). A Global Hypothesis for Women in Journalism and Mass Communication. Gazette, 67(3), 239-253. [ Links ]

Rush, R., Oukrop, C., & Sarikakis, K. (2005). A Global Hypothesis for Women in Journalism and Mass Communications: The Ratio of Recurrent and Reinforced Residuum. Gazette: The International Journal for Communication Studies, 67(3), 239-253. [ Links ]

Rush, R., Oukrop, C., Bergen, L., & Andsager, J. (2004). "Where are the broads?"been there, done that...30 years ago:An update of the original study of women in journalism and mass communication education, 1972 and 2002. In R. Rush, C. Oukrop, & P. Creedon (Eds.), Seeking Equity for Women in Journalism and Mass Communication Education: A 30-Year Update (p. Chapter 5). Mahwah, New Jersey: Lawrence Erlbaum. [ Links ]

Sader, S. B., Odeendaal, M., & Searle, R. (2005). Globalization, Higher Education, Restructuring and Women in Leadership:Opportunities or Threats? Agenda:Empowering Women for Gender Equity, 19(65), 58-74. [ Links ]

Salkind, N. J. (2010). Convenience Sampling. In S. Neil (Ed.), Encyclopedia of Research Design (p. 255). Thousand Oaks, California: Sage.

Skjerdal, T. (2011). Teaching Journalism or teaching African Journalism? Experiences from Foreign Involvement in a Journalism Programme in Ethiopia. Global Media Journal, 5(1), 24-51. [ Links ]

Subrahmanian, R. (2003). Gender Equality in Education: Definitions and Measurements: Global Monitoring Report. UNESCO. Paris: UNESCO. [ Links ]

Suraj-Narayan, G. (2005). Women in Management and Occupational Stress. Agenda:Empowering Women for Gender Equity, 19(65), 83-94. [ Links ]

Sustainable Development Knowledge Platform. (2015, August). Open Working Group proposal for Sustainable Development Goals. Retrieved September 16, 2015, from https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/focussdgs.html

Theus, K. (1985). Gender Shifts in Journalism and Public Relations. Public Relations Review, 11(1), 42-56. [ Links ]

UNESCO Institute of Statistics. (2014). Ghana Country Profile. Retrieved from UNESCO Institute of Statistics Data Centre: http://www.uis.unesco.org/DataCentre/Pages/country-profile.aspx?code=GHA

United Nations Statistics Division:Department of Economic and Social Affairs. (n.d.). Milliennium Development Goals Indicators. Retrieved from http://mdgs.un.org/unsd/mdg/Metadata.aspx?IndicatorId=9

Utuka, G. (2008). The Emergence of Private Higher Education and the Issue of Quality Assurance in Ghana, the Role of National Accreditation Board (NAB). Conference 2008, At Victoria University of Wellington, New Zealand , (pp. 1-15). Wellington.

Valenti, J. (2015, September 28). Feminism Jessica Valenti Column: Gender Inequality is a Problem Created by Men - Now They Must Help to Fixt. Retrieved September 28, 2015, from The Guardian: http://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2015/sep/28/gender-inequality-men-created-they-fix-it

Walters, M. (2006). Feminism: A Very Short Introduction. Oxford, UK : Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

van Zoonen, L. (1998). One of the Girls?: The Changing Gender of Journalism. In S. Allan, G. Branston, & C. Carter (Eds.), News, Gender and Power (pp. 33-46). London, New York: Routledge, Taylor and Francis Group. [ Links ]

World Journalism Education Council. (2008-2014). World Journalism Education Council. Retrieved from http://wjec.ou.edu/index.php: http://wjec.ou.edu/census.php