Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Acessos

Acessos

Links relacionados

-

Similares em

SciELO

Similares em

SciELO

Compartilhar

Observatorio (OBS*)

versão On-line ISSN 1646-5954

OBS* vol.11 no.2 Lisboa jun. 2017

No Hate Speech Movement: evolving genres and discourses in the European online campaign to fight discrimination and racism

Sole Alba Zollo*

*Universitá Degli Studi di Napoli L´orientale

ABSTRACT

In March 2013, the Council of Europe (COE) launched the No Hate Speech Movement, a media youth campaign against hate speech in cyberspace. In this paper, we analyze a corpus collected from the COE’s website. The corpus includes web site pages designed by the COE’s campaigners, as well as materials such as self-made videos and photos posted on the blog by the general public. We focus on the No Hate Speech Movement landing page and the Hate Speech Watch page. Following the tradition of social semiotics, we propose to investigate the verbal and visual features across a range of different genres, in an attempt to verify whether the interaction of different modes involves any contamination in discursive practices, which could lead to the evolution of existing genres or to the birth of new text types. Moreover, we focus on the relationship between community and context in order to verify whether web-based communication alters the terms for determining genre. Finally, we try to understand the role of the audience by concentrating on the notion of participation.

Keywords: online hate speech, multimodality, hybridity, web-based genres.

Introduction

Hate speech: a difficult concept. Hate speech or freedom of expression?

When we refer to ‘hate speech discourse’, we usually consider three elements: the target (i.e., the group of people to which it refers), the content (the tone of the written or spoken text) and its possible consequences. It is difficult to give a precise definition of this concept. Clearly, its main feature is that it incites to violence. This lack of an exact definition means that the concept is relatively fluid, and can thus be adapted to the full range of possible situations between two forms of abuse: the abuse of freedom of expression and the abuse in limiting this. A definition, however, is necessary: without an internationally accepted definition, most offensive speech is protected by the right to freedom of expression (Cohen-Amalgor, 2011). It is quintessential to establish where the right to offend the others ends and where illegal hate speech starts. The most commonly used definition is the formulation laid down in the Council of Europe’s Committee of Ministers’ Recommendation 97(20), which also applies to online hate speech.

The term “hate speech” shall be understood as covering all forms of expression which spread, incite, promote or justify racial hatred, xenophobia, anti-Semitism or other forms of hatred based on intolerance, including: intolerance expressed by aggressive nationalism and ethnocentrism, discrimination and hostility against minorities, migrants and people of immigrant origin. (Committee of Ministers of the Council of Europe, Recommendation on hate speech 1997)

Moreover, the Council of Europe’s Additional Protocol to the Convention on Cybercrime has sought to clarify this concept by defining online hate speech as: any written material, any image or any other representation of ideas or theories, which advocates, promotes or incites hatred, discrimination or violence, against any individual or group of individuals, based on race, colour, descent or national or ethnic origin, as well as religion if used as a pretext for any of these factors. (Additional Protocol to the Convention on Cybercrime 2003)

Hate speech is dangerous, because it not only expresses ideas or dissent, it also promotes fear, can cause depression and even drive some victims to attempt suicide (Titley et al., 2012). Today, the Internet is increasingly used to expand the reach of hateful opinions to a wider audience. It has become an effective tool to disseminate racism by people who aim to incite intolerance or racial and ethnic hatred (Cohen-Amalgor, 2011).

The digital revolution has given birth to the so-called Information Age. Internet users can freely express their views and reach others directly, without intermediaries. Because of this, it is often considered a means of promoting democracy. However, there are negative consequences, as well. Because of the anonymity and ease of access, there are users who do not feel responsible for what they say, who often feel free to adopt the kind of antisocial behavior that encourages hate speech.

Hate speech is defined as bias-motivated, hostile, malicious speech aimed at a person or a group of people because of some of their actual or perceived innate characteristics. It expresses discriminatory, intimidating, disapproving, antagonistic, and/or prejudicial attitudes towards those characteristics, which include gender, race, religion, ethnicity, color, national origin, disability or sexual orientation. Hate speech is intended to injure, dehumanize, harass, intimidate, debase, degrade and victimize the targeted groups, and to foment insensitivity and brutality against them. A hate site is defined as a site that carries a hateful message in any form of textual, visual, or audio-based rhetoric. (Cohen-Amalgor, 2011, pp. 1-2)

Hate speech is related to a broad range of phenomena, among which racism, anti-Semitism, xenophobia, discrimination, human rights, freedom of expression, gender, LGBTQI issues, religions, extremism, disabled people. Moreover, it occurs in different fields: everyday life-privacy, politics, governmental structures-institutions, schools-bullying, social ‘science’, hate crime-law and order, media – printed media, TV, radio, Internet (Titley et al., 2012)

The Council of Europe and the No Hate Speech Movement

Cyberspace has become inundated by an overflow of discrimination (Press release 2013)1. In recent years, hate speech online has become one of the most frequent forms of human rights violations. It is difficult to monitor its online manifestation and to measure its impact, especially because of the development of social networks (see Figure 1). As the number of young people who are active in cyberspace continues to rise, the Council of Europe (COE) has launched the No Hate Speech Movement (2012-2014), a media youth campaign against hate speech in cyberspace. Designed to allow for national, cultural and linguistic diversity, the online campaign focuses on human rights education and particularly on the active role of young people aged from 13 to 30 years. It is based on online communities of young people who are willing to discuss and take action against hate speech online. Young people play a central role in the campaign, as they are the ones who take part in online and offline activities. They have become the most important agents. The main objective of this project is to fight racism and discrimination in online hate speech by equipping young people and youth organizations with the skills necessary to recognize and act against such human rights abuse.

Corpus and research questions

In this paper, a corpus collected from the COE’s website (http://nohate.ext.coe.int/) devoted to this campaign is analyzed from a multimodal perspective. It includes web site pages designed by the COE’s campaigners, as well as materials such as self-made videos and photos posted on the blog by the general public. Following the tradition of social semiotics, we will investigate the verbal and visual features across a range of different genres, in an attempt to verify whether the interaction of different modes involves any contamination in discursive practices, thus leading to the evolution of existing genres or to the birth of new text-types. Given the ephemeral and mutable nature of hyperlinks, we decided to direct our attention at the No Hate Speech Movement landing page, where we focused on the homepage and the Hate Speech Watch page. On the Hate Speech Watch page, we investigated a sample of English-language posts that had been uploaded in the period from January to December 2014, on the basis of which we propose to answer the following main research questions:

- Does the interaction of different modes involve any contamination in discursive practices?

- Does the verbal and visual interplay lead to the evolution of existing genres or to the birth of new text-types?

- Given the focus on the relationship between community and context, does web-based communication alter the terms for determining genre?

- What is the role of the audience?

Before proceeding to our analysis, we first present our multimodality theoretical framework.

Multimodality

In this day and age, as cultures are increasingly tending to intermix and the amount of available information continues to expand, boundaries are becoming more and more blurred. Moreover, the different means of communication are merging together and intermingling, creating multimodal texts. For many discourse analysts (Jewitt, 2002; Lemke, 2002; Bezemer, 2008) it has become evident that in order to understand web communication, the analysis of language alone is not sufficient. Even though multimodality and multimediality have always been present in most communicative contexts, they have been ignored by academics for a long time. It was not until relatively recently, with the emergence of the various possibilities for merging modes in the ‘new’ media such as the computer and the Internet, that scholars started to investigate the peculiar characteristics of these modes and how they semiotically work and combine in the contemporary communication world (Burn, 2009; Adami, 2013).

The methodological framework of social semiotics (Hodge and Kress, 1988) has been developing for some decades, starting from Visual Grammar (Kress and van Leeuwen, 1996, 2006) and given definite shape by Multimodal Discourse Analysis (Kress and van Leeuwen, 2001). Since then, many scholars have been investigating this field and have produced a number of valuable works, in some cases elaborating on the original results, such as, for example Baldry and Thibault (2006) have done. Although referring explicitly to Hallidayan linguistics, social semiotics and multimodal analysis demonstrate that a multimodal approach to texts affords new perspectives on the interpretation of language and communication.

There is increasing interest among scholars from various disciplines (linguistics, education, sociology, media studies) in the role of modes in representation and communication. These modes are perceived as closely connected in the communicative process, which has led to the analysis of multimodal discourses in a range of contexts, including workplaces, museum exhibitions, online environments, across a range of genres and technologies (Zammit and Downes, 2002; Ravelli, 2005; Knox, 2007).

A fundamental aspect of multimodality is the analysis of language; this, however, is embedded within a wider semiotic frame. It is part of a multimodal ensemble. In fact, many studies have focused on the relationship between language and images, such as the early work of Kress and van Leeuwen (1996), Lemke’s work on science textbooks (1998), works by Martinec and Salaway (2005) and research by Bezemer and Kress (2008), to name but a few. They draw on Systemic functional grammar to identify the dependency relations between image and text. Martinec and van Leeuwen’s (2008) research on the inter-semiotic interplay in new media texts suggests that the word-image relations are remade through their reconfiguration in digital media, even though these relations are not completely established.

Theoretical exploration of the interaction between image and language has demonstrated that technological developments have caused images increasingly to take center stage in communicative events. Furthermore, screens have been shown to be displacing the media of the printed page to an ever-growing extent (Jewitt, 2002, 2008). Consequently, it is difficult to consider writing in isolation from the multimodal ensembles in which it is embedded.

People have always used non-verbal elements to communicate, but technology now allows modes to be configured in different ways. New technologies play an essential role in how modes are made available, configured and accessed (Jewitt, 2006) and they can impact on design and text production and on interpretative practices. Much has been written about the dominance of the visual in contemporary society. Several multimodal studies have focused on how the different modes are organized on the page or screen of textbooks, websites and other digital learning resources (Bezemer and Kress, 2008; Jones, 2005, Norris, 2012; O’Halloran and Smith, 2011) as well as films, adverts and other new media texts (O’Halloran, 2004; Burn, 2009; Baldry, 2004). Other studies have focused more in general on the technologization of practices and communication and interaction (Marsh, 2005; Unsworth et al., 2005). Much of this research examines the dynamics of the interaction between image and writing in narratives, relations between book and computer-based versions of texts, and the role of on-line communities, including hypertexts, which enmesh writing, image and other modes in digital technologies (Luke, 2003; Lemke, 2002). Over the past few years, attention has increasingly gone out to the specialized communication in English used in institutional contexts (Martin and Christie, 1997; Gotti, 2003) and many multimodality studies have been conducted on text making in digital and online environments (Lemke, 2002; Adami, 2013).

Multimodality is gaining importance as a methodological approach, since writing no longer seems sufficient to understand representation and communication in a range of fields. Also, it has become necessary to understand how writing interacts with non-verbal modes in the online communicational landscape. A web page cannot create meaning through the use of language alone, but relies on a combination of linguistic, graphic and spatial meaning-making resources. The interdependence of semiotic resources in text, particularly written and visual resources, is becoming the norm; likewise, the shape of discourse communities is changing with the changing shape of texts.

No Hate Speech Movement: a verbal and visual analysis of the COE’s online youth campaign

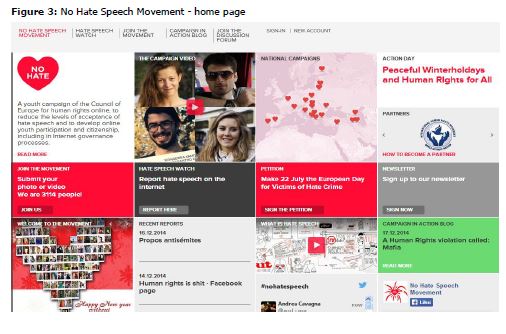

No Hate Speech Movement is the main landing page of the campaign. It is an online platform for everyone interested in joining the movement. People can upload their personal statement or message about hate speech, including self-made videos and photos. Young moderators work behind the site to guarantee respect for the campaign’s values. This page has become an instrument of self -expression, as Figure 2 shows, a place where people express their own ideas about hate speech by uploading personal photos and videos. It seems that the combination of different modes and genres has become essential in order to build an effective message and convince others to join the movement. The most interesting aspect is that users themselves become persuaders, yet remarkably, they not only help the Council of Europe’s campaign against hate speech online, they also produce the campaign material themselves. They are actors and initiators who are giving birth to new kinds of participation genres. The users decide what the point of their engagement will be — what application, what device, what time and what place. All the pictures present mostly smiling people in medium size and looking at the audience. They hold a sign with a slogan or sentence or the campaign’s slogan. They demand that the reader take part in the campaign. Moreover, the phrase ‘we are 3333 people!’ on the left side of the page, is a persuasive strategy of sorts, as the use of the inclusive ‘we’ is a way to make the audience part of the community and functions as an invitation to join the campaign. The number of supporters, which is intended to increase, is typically used to emphasize the fact that the users have already been able to build a big and active community.

The interaction between the images and words is therefore fundamental. As Figure 3 illustrates, the important point is that the texts are embedded in, and help to define the context in which they work. Verbal and visual texts are inseparable parts of the meaning-making activities in which they take part. The intrinsic properties of the different multimodal texts and their organization on the page enable them to create meaning.

If we analyze these images, taking into account Halliday’s metafunctions (see also Harrison, 2003, who discusses these metafunctions while referring to Kress and Van Leeuwen, 2006), the participant-process relationship is given by a single participant, a man or woman, or a group of people, and a vector which goes from their eyes towards the viewer. Interpersonally, we have a direct gaze, which creates eye contact between the members and the viewers and gives rise to a visual demand. There is a medium-close distance, establishing the possibility of a personal relationship with the users. A frontal perspective locates the participants within the same world of the viewer and they are on the same level, establishing a relationship of equality and, particularly, of solidarity. All the participants are equal and together they can contribute to the fight against hate speech.

Font size and type are salient. The visual, linguistic and graphic dimensions are combined. The logo obviously has a specific organizational identity. It has an anchoring function, which grounds the map here in relation to a specific cause, with which the user of the hypertext can identify.

No finite verbs are used in the main headings of each hyperlink; instead, these contain truncated grammatical structures, which have an appeal function. This use of addressee-directed imperative verbs is a feature typical of an exhortation genre aiming to persuade viewers to adopt a desired action.

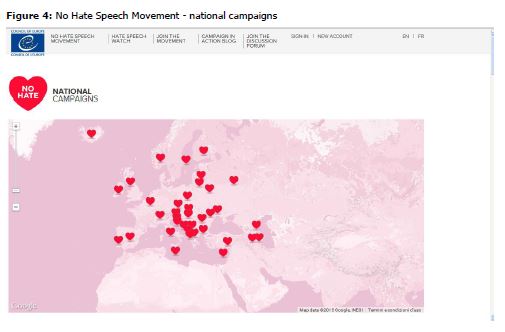

Maps are another common visual element used by websites. A map is an immediately recognizable text, which also offers cross-cultural availability. Texts recontextualize meanings and practices in one modality to some other modality, from one context to another context. The map is a recontextualization of the typical google maps used to help users to visualize the places they are looking for. So here, using this iconic and symbolic resource will prompt users to evoke these sights in their mind’s eye. It works on the assumption that users know what this map is and will have previously seen similar maps.

On this website (Figure 4), the map is not only used as an iconic resource through which users can understand where the different European communities are located. It also has a subtler communicative function. By using a heart instead of a flag, this map draws attention and symbolically relates to the movement purpose. The red hearts increase the salience, which is further stressed by the use of centering (Kress and van Leeuwen, 1996). The use of concentric circles provides a centered, salient focus that contributes to meaning making: the importance of a central cross-cultural united movement to fight hate speech. This map seems to have been created to communicate an image of Europe as a united entity. The use of a map and, in particular, the design chosen, thus become a projection of the online community’s vision of a Europe that has symbolically come together to share the same goal. In that light, the map here would seem to become an expression of a collective European identity.

What is interesting is the inclusion of a sketch video, a technique which has become very popular in advertising discourse. It is often used to make sales videos, since this type of video, in which a hand is shown that moves quickly across the screen, sketching words and images (http://www.sketchvideos.com.au/), draws the attention of high level corporate executives.

‘No Hate Ninja Project - A Story About Cats, Unicorns and Hate Speech’ is a hand drawn video about hate speech in which the interaction of different modes – music, words, drawing, colour and typography – work together to create a message against hate speech and online bullying. In addition, the interrelation among the different modes is supported by the voice-over, which, by explaining step by step all the movements of the hand, contributes to creating a coherent and effective message.

The main purpose is to reach people emotionally, which is achieved, among other things, by using kinetic typography instead of static texts. Even if technological developments have increased the interaction between modes in most websites, the relationship between moving images and static texts is still restricted. In a society that is increasingly driven by the media on the basis of improvements in computer technology, it is mainly image and text information which represents the central point in people’s daily lives. As a result, the role of movement has changed radically. ‘Motion is no longer a cause of anxiety, or desperation; motion has become a tool for seduction. Kinetic information hunts us down, whilst we are increasingly drawn towards it’ (Hillner, 2005, p. 67). As people desire to be seduced, kinetic typography would therefore appear to be far more powerful than printed texts. In order to analyze typography, we should not only consider it in terms of typefaces size and kerning, but, according to Hillner (2005), in relation to motion, as well. To communicate effectively, we have to take into account people’s sensual needs. Kinetic typography creates tension between the form and the content. It emphasizes some aspects gradually by synchronizing different modes and stirring interest in the audience.

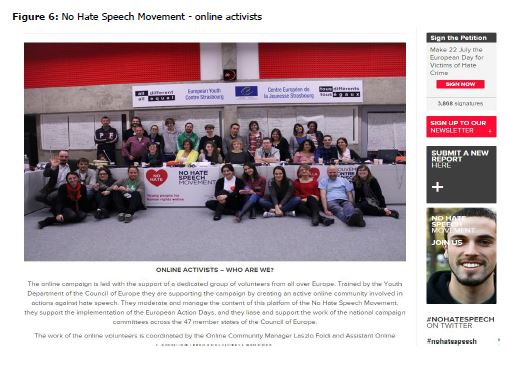

Contrary to the photos uploaded by the community members, the online activists are depicted in a blank, empty setting (see Figure 6). A few props, such as a pc, a microphone and a conference table, index a public place for official events; according to Kress and van Leeuwen (1996) the absence of an articulated background lowers modality. So through dynamic hyperlinks, the images move from naturalistic representations to more abstract and aseptic space. In the photos uploaded by the users, colors play a key role in the modality, all the more so as the colors of the slogans and other objects present in the frame are closely coordinated. In the bloggers’ photos, the use of an abstract setting evokes a staged space, giving more authority to the actors and legitimizing their role as moderators: they are in charge of managing the content of the platform.

In this multilingual and multicultural virtual environment, visual discourse could work as a cross-culturally communicative strategy because of its iconic accessibility. No semiotic mode exists in isolation from other meaning-making practices. Language is understandable only in relation to other non-verbal modes.

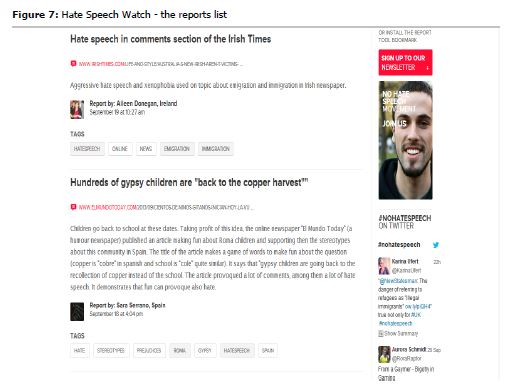

Hate Speech Watch is an online database that aims to collect, monitor, share and discuss hate speech content of the Internet. Registered users can link to any hate speech content from the Internet. They can tag the posts, comment on them and discuss them. Moderators monitor the site and every month they create focus topics according to the main interest of the online community.

The reports list has a recurrent structure. As Figure 7 shows, the page includes a headline, the link to the website containing the examples of hate speech, a short sentence or paragraph summarizing the content, the user’s details (name, country) and tags.

The reports list could be defined as a new hybrid form of interactive communication. According to the Oxford dictionary a report is:

an account given of a particular matter, especially in the form of an official document, after thorough investigation or consideration by an appointed person or body;

a spoken or written description of an event or situation, especially one intended for publication or broadcasting in the media. (http://oxforddictionaries.com)

Contrary to the Oxford dictionary’s definition of report, a reports list on the Council of Europe’s website fulfills different functions. Firstly, it is an online monitored collection of hate content of the Internet. It is both an educational tool and a place for taking action, as users can read reports, but also comment on them and upload new reports. Some features typical of genres such as reports and social networks, such as facebook and forums, have been transformed and recontextualized, giving birth to a new mixed form of online communication. This new hybrid genre also presents a blending of different discourses, such as news discourse and personal/conversational discourse.

As is evident from excerpts 1, 2 and 3, direct and indirect speech typical of news discourse often alternate. The activists report the facts through their own words, but in order to reinforce the message, they often report what external sources said, thus incorporating other texts into their text through direct intertextual references (Fairclough, 2003). Moreover, the use of personal pronouns such as ‘I’ or ‘we’ contributes to reinforce the reporters’ beliefs and ideas.

Excerpt 1

A French politician sparked outrage by telling2 a group of travellers that, perhaps, not enough gypsies were killed during Adolf Hitler's Nazi regime. Report by: Ana López, Spain July 23 at 7:30 am

Excerpt 2

We would like to post a quotation from this blog "Fags don't realize that their existence fucks shit up for every other homosexual.” Report by: D K, Italy September 18 at 3:16 pm

Excerpt 3

Article in Irish daily newspaper about gangland culture in Marseilles, with hate speech in the comments. “JimGentry: It is the same anywhere that a ghetto of unwanted immigrants exists.. I like Marseille but it is more African than Africa. My impressions of the French, in particular Parisiens is that they dislike everyone, including the Irish.” Report by: Aileen Donegan, Ireland September 12 at 9:52 am

Reporting is often mixed with personal comments expressed by evaluative adjectives, particularly comparatives and superlatives, which emphasize the danger of hate speech online.

Excerpt 4

This is not the only tweet but is the most worrying one. He is going to a EDL demo in Birmingham on Saturday and is posting threatening tweets. Report by: Michelle Murphy, United Kingdom July 18 at 9:34 pm

Excerpt 5

This is in Hungarian but subtitled in English. The comments are in English. A man, who claims himself gypsy is explaining that gypsy crime exists and supports with facts. He explains how it should be prevented. Many of his ideas may make sense in terms of prevention, the 'only' mistake he makes is that he uses the term 'gypsies' instead of criminals, which of course is welcomed by many people. When reading/listening this speech one can easily fall in the same trap. Very dangerous! And look at the comments. They are even stronger. Report by: Community Manager, Hungary March 21 at 3:10 pm

Colloquial expressions (see excerpts 6 and 7), which are very common in social networks, here become an instrument to shorten the distance to the audience by trying to create involvement.

Excerpt 6

This page is created to "judge" LGBT people and religious minorities. Full of hate speech pages hasn't been closed by FB administration after several reports. Report by: Arman Sahakyan, Armenia August 7 at 7:48 am

Excerpt 7

Aggressive hate speech and xenophobia used on topic about emigration and immigration in Irish newspaper. Report by: Aileen Donegan, Ireland September 19 at 10:27 am

We also find definitions taken from official sources, the use of which serves to give added authority to the Hate Speech Watch message. We find tags, such as the following, where in order to explain the word ‘victim’, the user has resorted to the official definition given by the UN Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights.

Victim: A person, who as a result of certain acts or omissions suffers harm, including physical or mental injury, emotional suffering, economic loss, or impairment of that person's fundamental legal rights. A "victim" may also be a legal person, or a member of the immediate family or household of the direct victim, as well as a person who, in intervening to assist a victim or prevent the occurrence of further violations, has suffered physical, mental, or economic harm. Source: UN Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights

Conclusions

The findings have enabled us to provide satisfactory answers to the research questions stated in section 1.3. The high level of interaction among different modes, in particular words, images and typography, involves a contamination in online discursive practices, which leads to hybridization and spawns new web-based text-types. In fact, the analysis has demonstrated that the Council of Europe’s online platform against hate speech ‘exploits’ features borrowed from different media such as blogs, Facebook and YouTube. The reports contain links to other media, which are often directly mentioned in the report. This platform can be considered a new form of digital communication, the product of the blending of different genres (news report, commentary, diary) and discourses (news discourse, conversational discourse, official discourse).

Concerning the actors’ role, the results presented in this paper show that they are active agents in creating a new type of communication that is reshaping the framework of determining genre. The users report the events the same way journalists do, but they often express their point of view, as well. The audience, i.e young people, therefore, become actors and initiators who are creating new kinds of participation genres. Today, young people are often called ‘Web 2.0’ generations (Elia, 2008). They are also participants. This platform is a completely new approach to addressing cyberhate. These young people are non-expert participants on cyberhate but they are experts in young people and are therefore more likely to recognize the sites that will attract their peers and the type of issues engaging the people of their generation.

Moreover, since the campaign does not limit their role to that of spectator, but invites them to participate, comment and to make suggestions, we need to reconsider the relationship between community and context; the new hybrid medium alters the terms of determining genre. “It is the context that seems to create genres, and communities emerge around them. The concept of the genre-regulating, pre-existing community does not apply to web-based genres” (Mauranen, 2013, p. 57). In this digital networked age, audiences have new possibilities for action, interaction and participation.

Audiences are also participants in society, democracy and culture. Expert and non-expert competences mix together, generating new participatory genres. Many scholars have focused on audience and its role in the digital era, in particular, on how people today interact and connect each other in the different ways of communication through media especially the net. The attitude of the audience has changed: today, genres are built in discourses, not in a pre-existing community.

Where once, people moved in and out of their status as audiences, using media for specific purposes and then doing something else, being someone else, in our present age of continual immersion in media, we are now continually and unavoidably audiences at the same time as being consumers, relatives, workers, and – fascinating to many – citizens and publics. (Livingstone, 2013, p. 22)

References

Adami, E. (2013). A Social Semiotic Multimodal Analysis Framework for Website Interactivity, NCRM Working Paper (http://eprints.ncrm.ac.uk/3074/).

Baldry, A. (2004). Phase And Transition, Type and Instance: Patterns in Media Texts as Seen through a Multimodal Concordance. In K. O’Halloran (Ed.), Multimodal Discourse Analysis: Systemic Functional Perspectives. London and New York: Continuum.

Baldry, A., & Thibault, P. J. (2006). Multimodal Transcription and Text Analysis. A Multimedia Toolkit and Coursebook, London: Equinox. [ Links ]

Bezemer, J., & Kress, G. (2008). Writing in Multimodal Texts: A Social Semiotic Account of Designs for Learning, Written Communication 25 (2), 165-195. [ Links ]

Bhatia, V. K. (2004). Worlds of Written Discourse, London: Continuum International Publishing Group. [ Links ]

Burn, A. (2009). Making New Media: creative production and digital literacies, New York: Peter Lang. [ Links ]

Cohen-Amalgor, R. (2011). Fighting Hate and Bigotry on the Internet, Policy and Internet 3 (3) art. 6, 1-26.

Elia, A. (2008). ‘Cogitamus Ergo Sumus’ Web 2.0 Encyclopedi@s: The Case of Wikipedia, Roma: Aracne.

Fairclough, N. (1992). Discourse and Social Change, London: Polity. [ Links ]

Fairclough, N., & Wodak, R. (1997). Critical Discourse Analysis. In T. A. van Dijk (Ed.), Discourse as Social Interaction. Discourse Studies: A Multidisciplinary Introduction. Vol. 2. London: Sage. [ Links ]

Gotti, M. (2003). Specialized Discourse. Linguistic Features and Changing Conventions, Bern: Peter Lang. [ Links ]

Hall, C., Sarangi, S. et al. (1999). Speech Representation in Social Work Discourse, Text 19 (4), 539-70.

Halliday, M. A.K. (1994). An Introduction to Functional Grammar, London: Arnold. [ Links ]

Harrison, C. (2003). Visual social semiotics: Understanding how still images make meaning,Technical communication 50 (1), 46-60. [ Links ]

Hillner, M. (2005). Text in (e)motion, Visual Communication 4, 165-171. [ Links ]

Hodge, R., & Kress, G. (1988). Social Semiotics, Cambridge: Polity Press. [ Links ]

Jewitt, C. (2002). The Move from Page to Screen: the Multimodal Reshaping of School English, Visual Communication 1 (2), 171-196. [ Links ]

Jewitt, C. (2006). Technology, Literacy and Learning: A multimodal approach, London and New York: Routledge. [ Links ] (2008; 2nd ed.).

Jones, R. (2005). ‘You show me yours, I’ll show you mine’: The negotiation of shifts from textual to visual modes in computer mediated interaction among gay men, Visual Communication 4 (1), 69-92.

Knox, J. S. (2007). Visual-verbal communication on online newspaper home pages, Visual Communication 6 (1), 19-53. [ Links ]

Kress, G. (1998). Visual and Verbal Modes of Representation in Electronically Mediated Communication: the Potentials of New Forms of Text. In I. Snyder (Ed.), Page to Screen: Taking Literacy into the Electronic Era. London: Routledge. [ Links ]

Kress, G. (2000). Text as the Punctuation of Semiosis: Pulling at some of the Threads. In U. H. Meinhof & J. Smith (Eds), Intertextuality and the Media: From Genre to Everyday Life. Manchester: Manchester University Press. [ Links ]

Kress, G., & van Leeuwen, T. (1996). Reading Images: the Grammar of Visual Design, London and New York: Routledge. [ Links ] (2006; 2nd ed.).

Kress, G., & van Leeuwen, T. (2001). Multimodal Discourse. The Modes and Media of Contemporary Communication, London: Arnold. [ Links ]

Lemke, J. (2002). Traversals in Hypermodality, Visual Communication 1 (3), 299-325. [ Links ]

Lemke, J. (2005). Multimedia Genres and Traversals, Folia Linguistica 39 (1-2), 45-56. [ Links ]

Livingstone, S. (2013). The Participation Paradigm in Audience Research, The Communication Review 16 (1-2), 21-30. [ Links ]

Luke, C. (2003). Pedagogy, Connectivity, Multimodality and Interdisciplinarity, Reading Research Quarterly 38 (3), 397-403. [ Links ]

Marsh, J. (Ed.) (2005). Popular Culture, New Media and Digital Literacy in Early Childhood, London: Routledge/Falmer.

Martin, J. R., & Christie, F. M. (1997). Genre and Institutions. Social Processes in the Workplace and School, London: Cassell. [ Links ]

Martinec, R., & Salway, A. (2005). A System for Image-Text Relations in New (and Old) Media, Visual Communication 4 (3), 337-371. [ Links ]

Martinec, R., & van Leeuwen, T. (2008). The Language of New Media Design, London: Taylor and Francis Ltd. [ Links ]

Mauranen, A. (2013). Why Take an Interest in Research Blogging?, The European English Messenger 22 (1), 53-57. [ Links ]

Norris, S. (2004). Analyzing Multimodal Interaction: A Methodological Framework, London: Routledge. [ Links ]

O’Halloran, K. L. (2004). Visual Semiosis in Film. In K. L. O’Halloran (Ed.), Multimodal Discourse Analysis: Systemic Functional Perspectives. London and New York: Continuum.

O’Halloran, K. L., & Smith B. A. (2011). Multimodal text analysis. In C. A. Chapelle (Ed.), Encyclopedia of Applied Linguistics. NJ: Wiley-Blackwell. [ Links ]

Ravelli, L. (2005). Museum Texts: Museum Meanings, London: Routledge. [ Links ]

Swales, J. M. (1990). Genre Analysis. English in Academic and Research Settings, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

Titley, G. et al. (2012). Starting Points for Combating Hate Speech Online. Three studies about online hate speech and ways to address it. Strasbourg: Council of Europe, http://theewc.org/library/category/view/starting.points.for.combating.hate.speech.online/ (last accessed April 2015).

Unsworth, L, Thomas, A, Simpson, A., & Asha, J. (2005). Childrens’ literature and computer based Teaching, Maidenhead: Open University Press.

Van Leeuwen, T. (2005). Introducing Social Semiotics, London: Routledge. [ Links ]

Wodak, R. & Wright, S. (2006). The European Union in Cyberspace. Multilingual Democratic Participation in a Virtual Public Sphere?, Journal of Language and Politics 5 (2), 251-75. [ Links ]

Zammit, K., & Downes, T. (2002). New learning environments and the multiliterate individual, Australian Journal of Language and Literacy 25 (2), 25-36. [ Links ]

NOTAS

1 It is available at: https://wcd.coe.int/ViewDoc.jsp?id=2046757&Site=DC&ShowBanner=no&Target=_self&BackColorInternet=F5CA75&BackColorIntranet=F5CA75&BackColorLogged=A9BACE

2 In the excerpts underlining is added by the authors.