Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Acessos

Acessos

Links relacionados

-

Similares em

SciELO

Similares em

SciELO

Compartilhar

Observatorio (OBS*)

versão On-line ISSN 1646-5954

OBS* vol.10 no.4 Lisboa dez. 2016

Broadcast television flow scheduling and the viewers’ zapping: conflicting practices

Eduardo Cintra Torres*

* Professor at Portuguese Catholic University, Lisbon, Portugal (ect@netcabo.pt)

ABSTRACT

Broadcast television and its audiences live a paradoxical situation: on the one hand, channels still schedule according to the concept of flow; on the other hand, viewers’ zapping counters it. This paper wishes to ascertain the audiences’ practices regarding their fidelity to flow. The research tries to answer these questions: how many viewers watch the same channel during a long consecutive period? How many viewers watch a complete programme? Are there significant differences in zapping versus flow faithfulness according to sex, age, socio-demographic class and cable TV access? Is “companionship television” still a viewers’ consume practice? The research verifies the effectiveness of flow scheduling, which, while being an ideology and a scheduling and self-promotion practice, is not a practice of most viewers. The results show that flow faithfulness flow is a minority behaviour mainly of older people, women, lower classes and viewers without occupation.

Keywords: Scheduling, zapping, ratings, flow, audience, television.

Introduction

The concept of television flow as “perhaps the defining characteristic of broadcasting, simultaneously — as technology and as a cultural form” was developed by Raymond Williams (1992, 8, 80-85) after his first impact with the “characteristic American sequence” of programmes, self promotions and advertising “available in a single dimension and in a single operation”. He was “not prepared” for this “planned flow” lived as an “experience” by viewers. In this new way to consider the media, flow took the place of discrete programmes as the main material for analysis.

Flow is partly the result of scheduling, the programmers’ “last really creative art” (Ellis 2000, 25) of putting the pieces together in a puzzle attracting the highest number of viewers available during their transmission. The main objective of the macro-narrative of scheduling is to avoid zapping: the scheduler’s art is “in creating a seamless televisual flow that secures channel loyalty” (Casey et al. 2002, 206) for both flow and discrete programmes. Flow is also a never ending discourse of self promotions of segments or programmes “still to come”, “coming up”, “next”, “stay with us”, catch-phrases insistently repeated in the British parodic series Broken News (2005). Self promotions inside and out of programmes and inside commercial breaks are part of the “political economy of the television (super) text” (Browne 1987), or “super-flow” (Bjur 2009).

When Williams had his flow epiphany in Miami, four decades ago, the access to live television from far away countries was impossible. No archive preserved the flow emissions.1 Only individual programmes travelled from one country to another. Satellite television was used only for special programmes. Broadcast was the only kind of television available: either one watched programmes, or lost them; cable was just beginning in the US. Remote controls and the first equipments to privately record TV contents were being introduced. In this context, the flow concept could be an effective practice of American commercial, broadcast television. It developed a “mode of address” (Brunsdon 1990, 62) urging the viewer to stay tuned to the channel as if it was the only one.

Williams’s notion of flow “is primarily textual” (Uricchio 2004, 167) and most academic references to the flow notion share with it that perspective (e.g. Brunsdon 2010); the institutional sphere of television is also studied, since media convergence puts “flow under pressure” (Bulck and Enli 2014). In what regards audiences, technology, fragmentation and viewing practices invite to a “viewer-centered notion” of flow (Uricchio 2004, 168). Scholars cannot assume the audiences’ compliance to or refusal to flow without using ratings or other empirical materials, like surveys or interviews.

The viewer’s empowerment in the last decades has not deterred producers, advertisers, and programmers from “redoubling their efforts to maximize something like Williams’s notion of flow in its most literal sense, linking program units in such a way as to maximize continued viewing” (Uricchio 2004, 173). The control devices have “greatly disrupted flow as a fundamental characteristic of the medium, at least in terms of television flow being determined by someone other than the individual viewer” (Lotz 2014, 39), but the ideological discourse of flow is common practice, specially, but not only, of free-to-air channels. While new ways of accessing contents, as Netflix, adopted the “publishing model”, broadcast and cable television have still to work within their “flow model” ontology, to use Miège’s concepts (Miège 1989, 145). This paper deals with free to air channels, but, opposite to Gripsrud (2002, 213), who defended flow as a quality built into broadcasting but not television in general, it is easy to verify that most if not all cable channels also use flow practices and discourse, due to the inescapable ontology of being organized by time, or, as Uricchio (2010) says in another context, for being “time machines”.

The practices of flow described by Williams were already in a tandem with television ideology. Broadcast media presupposed a live, simultaneous and in great part unknown audience at a distance; liveness stresses the simultaneous contact between channels and viewers; television was part of daily life and was developed as a family media and as a suburb reality and design of “white, Christian, and middle class” families “living in single-family homes” (Spigel 1992). As it developed in the US, “network television works to preserve a specific fantasy of the American family” (Hatch 2002, 76; Paterson 1990).

Thus, flow was a practice of the broadcast television agency based on a concept of uninterrupted viewing. For network executives and advertisers, in “this ‘audience-flow’ theory, the audience is viewed as a river that continues to flow until it is somehow diverted” (Epstein 1973, 93). Williams (1992, 87) also mentioned this “belief - which some statistics support - that viewers will stay with whatever channel they begin watching”. It was a programming and scheduling strategy based on, or at the origin of an ideology, intended to attract and maintain the viewers, that became a discourse practice of television also for economic reasons: the “continuity flow or narrative normalcy [...] must be economic (commercials, station IDs, or promos) or deathly” (Mellencamp 1990, 244).

The following developments in television originated an evolution in the theory of the “continuousness of television” (Brunsdon 1990, 62), with Ellis (1982) adding the concept of text fragmentation, the fragment becoming the main unit in the televisual discourse. Also, the notion of flow was further diverted to an audience perspective by considering that it was built by the viewer in “viewing strips” (Newcomb and Hirsch 2000, 567). As part of his theory on the character of televisuality, Caldwell stated that “the televisual flow demands active decipherment and critical facility on the part of the viewer”, opening to a “construction of pluralism” (Caldwell 1995, 165). He or she is empowered to construct the individual flow independently of the channels’ offers: each viewer being “able to create his or her own absolutely unique viewing experience” (Heath 1990, 283).

Meanwhile, the righteousness of the flow concept was considered to be proved by ratings measurements. Among industry professionals, certain programmes were the right choice to induce audiences to stay on the same channel until the next programme begins. A good example is analyzed below, the RTP1 programme O Preço Certo (The Price Is Right), considered as a treasure by the public service operator, because of its supposed capacity to induce the audience to watch the following programme, the night news at 8:00, Telejornal. The opposite was known to a private competitor, TVI, in the 2000s, losing a great part of its juvenile telenovela Morangos com Açúcar audience — without being able to attract older viewers — as soon as the night news began,.2

Three striking elements, to my knowledge, have not been stressed by television studies. First, the fact that public service television channels, which didn’t practice the flow concept so extensively as private channels, came to fully adopt this commercial television ideology and practice. In 1989, flow could still be been defined as “the heterogeneous text of commercial television”, and an instrument to “produce the audience as commodity” (Budd and Steinman 1989, 17), but competition pushed State owned channels to the same programming strategy, especially in countries like Portugal, where the main State owned channel (RTP1) has included advertising since its inception in 1957. Flow came to be defended in Portugal as a public service main channel strategy needed to keep audiences: “the broadcast television emission not only means the resilience of the notions of sequence and flow but has also cultural, social, institutional and political meaning as public service” (Lopes et al. 2013, 41). Second, broadcast television maintains the practice of “TV for all the family” and the discourse and practice of flow television when it is proved that fragmented viewing is a norm of television viewing.3 Third, flow is an accepted concept to analyse programming and scheduling, but has not been studied, to my knowledge, as an audience practice through audience ratings. Thus, a “consideration of flow renders abundantly clear the need for audience analysis” (Gray and Lotz 2012, 128).

Television is now a multiplatform and multichannel media; audiences evolved from largely familial to largely individual viewing; new, alternative media and leisures now compete with television; TV operators are now compelled to produce contents that are conceived for a multiplataform environment (Suárez-Candel 2012; Theodoropoulou 2014; Klein-Shagrir 2014). The individualisation in viewing is validated by audience ratings, one of its variables being the channel switching in a larger spectre of choice, specially among the younger, men and more educated demographic groups (Bjur 2009). Still, flow kept its deserved analytical appeal:

“The academic study of television and its effects, too, remains bound to a number of concepts and paradigms that emerged with the broadcast era. Sometimes, as in the case of the notion of flow, the meaning of a particular term has modulated to keep pace with shifting distribution and viewing practices, serving as a barometer of change” (Uricchio 2009, 61).

In short, although “the media landscape has dramatically changed, flow remains a valuable tool for understanding television” and “the concept is still important as a structuring mechanism and branding strategy” (Thompson 2013, 283). Bjur (2009, 57) summarized a set of three types of flow: the “super-flow”, or the institutional production offer in each country (only public service, commercial channels or both, etc.), the “content flow”, coinciding with Williams’s notion, and the “viewer flow”, built by each TV consumer according to the available choices provided by the two other forms of flow. In this article, I use elements of the “viewer’s flow” to challenge resisting ideas of academic and industry uses of the concept. Thus, the research does not deal with differences between State-owned and private-owned channels mandates or programming practices; neither does it deal with multi-platform practices by both public and private channels. Its sole objective is to assess if the still existing flow ideology and practice by public and private broadcast channels has a counterpart in viewers’ practices. Since rating do not measure the multi-platform practices of the viewers who watched broadcast programmes, the research focus exclusively on the viewers’ practices with broadcast channels and programmes.

Data

To verify the fragmentation of television viewing, I analysed Portuguese empirical, statistic audience ratings data through MediaMonitor programmes analysis software provided by Marktest Audimetria / Kantar Media.<4 Academic studies seldom rely on ratings, considered a commercial production and out of the academics control, a capitis deminutio that Bourdon and Méadel (2014) invite scholars to surpass. True, ratings hardly provide insights in the meanings that viewers extract from programmes, contriving academics to more adequate, qualitative methods, or by a mixture of statistical and qualitative data (Vicente-Mariño, 2014). While also considering that it is vital to recourse to qualitative methods to understand viewers’ practices, uses, gratifications and appropriations, ratings are a useful source to access audiences within an academic perspective. Only they must be properly explored. With the collaboration of ratings companies, as Bjur (2009) has shown, it is possible to explore data beyond the simplified statistics normally published. In this presentation, I use “normal” ratings data but also “on demand” data, provided at my request by Marktest Audimetria. The data are from the four free-to-air Portuguese channels, a universe marked by competition and the flow practices and discourse.5 Most of the statistics used in this article had to be done in a case by case analysis, a time consuming process that did not allow to analyse extended periods. In most cases, I chose Friday, February 14, 2014, a normal day, with a fixed, regular programmes schedules, without any special TV event or flow disruptive programme in any of the channels. Ratings show that Portuguese viewers’ habits on Fridays are identical to other weekdays.

Data analysis

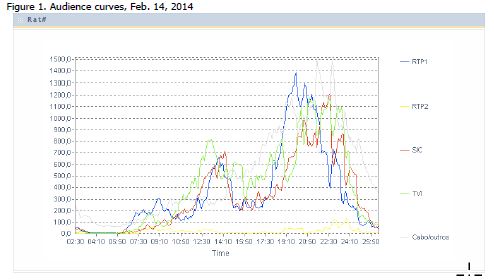

The most basic information, the daily ratings evolution (Figure 1) show two big mountains with several picks and several valleys. Viewers come and go to TV viewing and from channel to channel. The balance between ins and outs of each channel (a variable that, ironically, the industry calls “flow”) is intense minute by minute in all four channels during the 24 hours of Feb. 14, a pattern registered daily. This repeated reality is a reminder that the viewers’ flow experience could never be but a limited practice and of part of the audience.

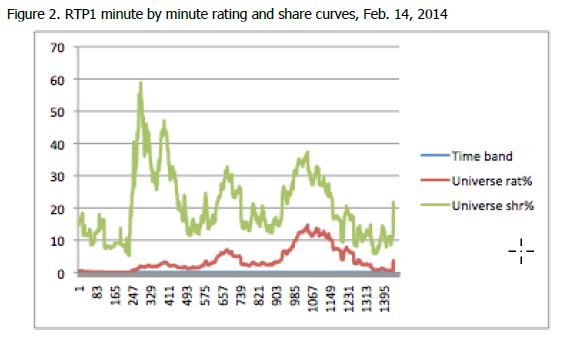

Minute to minute rating evolution shows strong variations. Figure 2 exemplifies the minute by minute rating (red) and share (green) of just one of the channels, RTP1, on the same day. For instance, in five minutes, from 2:48 to to 2:53, RTP1 lost half its audience (from 0.6 percent to 0.3 percent); the reverse movement can be as quick: from 7:11 to 7:16, the rating rose from 1.4 percent to 2.1 percent. An attractive entertainment programme and people getting home can produce a rise in ratings: from 18:40 to 19:24, during the regional news Portugal em Directo, preceding O Preço Certo, audience went from 7.5 percent to 12.5 percent. The channel rating changes almost every minute as a result of people (dis)connecting the TV sets in the household and the horizontal zapping through TV channels, but also the action of giving a different use to the TV set, like connecting a console, a DVD, an external drive or the Internet in the Smart TV, etc., a vertical zapping. The share curve shows the relation of one channel audience attraction in relation to the others, a strong vibration in the curve providing a first look at the viewers’ activity. We can see that most TV viewers in the early hours of the morning chose RTP1, giving it up to almost 60 percent of the share at 7:16.

At 18:00, RTP1 had an average of 441,790 viewers. During the sixty seconds until 18:01, 399,050 stayed on the channel; the increase came from 42,740 coming in, while 4,460 left the channel. Those who came in were viewers from RTP2 (3,490), SIC (13,700), TVI (11,200), and the remaining 14,280 were viewers who turned the TV on. In that minute, RTP1 only lost viewers to cable/other channels. Changes can be more dramatic. At the last two minutes of O Preço Certo, before Telejornal, RTP1 lost 275,680 viewers, while attracting only 55,730. The balance of ins and outs represented an audience loss of around 18 percent. The 275,680 who did not “respect” the flow ideology of the link between O Preço Certo and Telejornal represented 22.4 percent of the audience. Later in the evening, around 23:30, RTP1 lost more than half its audience of 581,260 viewers to 284,990 in only five minutes, when the quiz show Quem Quer Ser Milionário (Who Wants to Be a Millionaire) gave place to a talk show oriented to a younger audience, 5 para a Meia-Noite (5 to Midnight). Less than half (120,000) turned the TV set off, while the rest changed to other channels or TV set options.

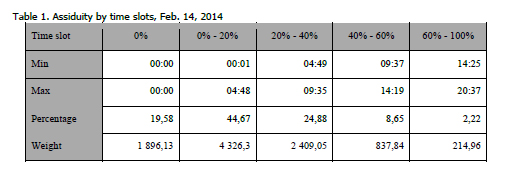

People spend time very differently watching television. As shown in Table 1, on our day of choice 19.6 percent of the universe didn’t watch television at all, 44.7 percent watched up to 20 percent of the 24 hours of the TV day (4:48); one quarter (24.9 percent) watched between 20 percent and 40 percent of the 24 hours (4:49 to 09:35); 8,7 percent of the TV audience in that day watched between 40 percent and 60 percent of 24 hours (09:37 to 14:19), and above that period the number is residual (2.2 percent). On average, each viewer watched 05:05 on this day. These numbers do not mean that people were faithful to one channel for a long period, although that can be expected from long time viewers.

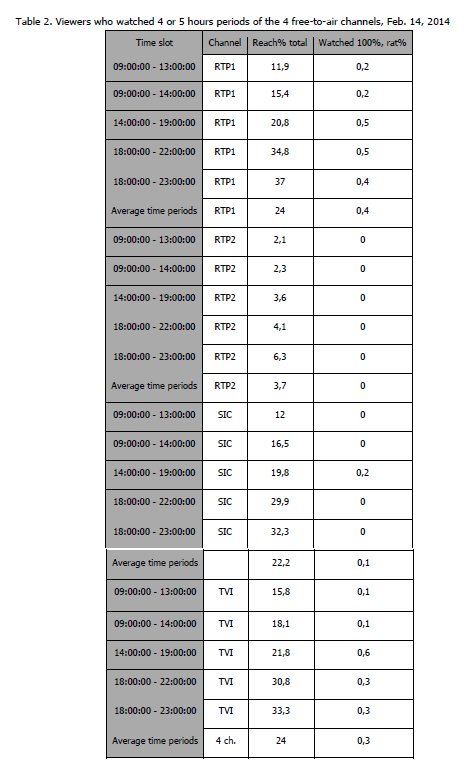

These statistics show the variance in the global audience, while not showing how individual viewers are connected to one channel and for how long. If flow is an audience practice, than a reasonable number of viewers should be watching the same channel without interruption for long periods. I chose to verify the flow audience in periods of four or five hours coinciding approximately with the morning, afternoon and night periods. Table 2 shows that the faithful audience of any of the four national channels is residual, especially when compared to the reach obtained by the channel in the same periods (that is, comparing the number of viewers who watched the programme for at least one minute with the faithful audience who never left the channel in the same periods). 6

The audience faithful to the flow in the considered periods is always under 0.7 percent. RTP1 is the channel showing in average a larger audience faithful to flow in the time slots considered here (0.4 percent in average). Those 35,400 viewers in average represent a very limited part (1.5 percent) of the 2,327,200 who watched the channel in those time slots during the day for at least one minute (that is, the reach in numbers, or 24.0 percent of the universe). The highest level of faithfulness occurs in the daytime, in the 14:00-19:00 time slot, but it never goes beyond 2.4 percent of the reach. The second State owned channel shows a zero faithfulness. The private channels show different audience behaviour regarding flow, with SIC with an average of only 0.1 percent and TVI with 0.3 percent. The audience faithful to flow in SIC is marginal (0.2 percent of the total average audience in the day), while TVI has managed to maintain a faithful audience, albeit small (1.2 percent), in all time slots studied. All in all, the evidence is that only a small minority of TV audiences of the four channels in the average of all periods considered (0.96 percent) practices the flow invitation constantly made by the channels.

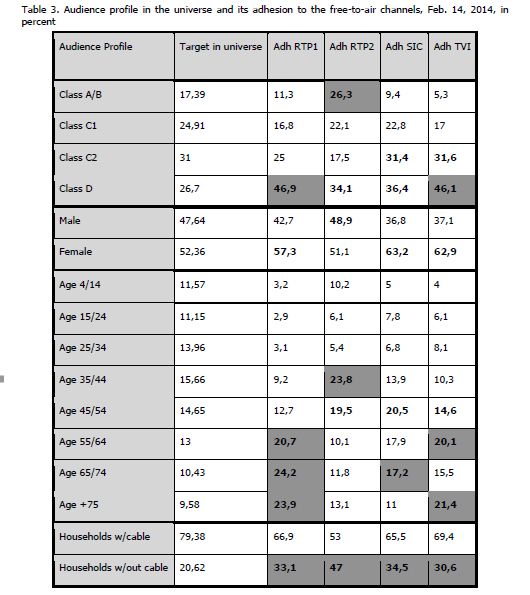

Who are the faithful to flow? Before entering the specifics, it is useful to, first, take note of the daily time devoted to watch TV, and then to check the audience profile of the four national channels. The time devoted by the Portuguese to television, amounted to 4:21 in the week Feb 28 - Mar 06. Considering only the TV audience, in the same period each viewer dedicated in average 5:24 to television viewing. In Table 3, I put side by side the targets dimensions and their adhesion to each channel. The targets are those defined by the television industry and ratings companies. “Classes” refer to socio-demographic characteristics of the households, taking in account the ownership and type of the house, education level and income. Numbers in bold show percentages larger than the target profile in the universe; numbers highlighted in grey are 50 percent or more above the target in the universe. Of the four channels, only RTP2 has a balanced profile in relation with the targets in the audience. Commercial broadcast channels, either public or private (RTP1, SIC and TVI), have similar audiences by targets: Class D, women, people aged fifty-five or more. Audience with access to cable have a lower adhesion to the four channels than their weight in the universe.

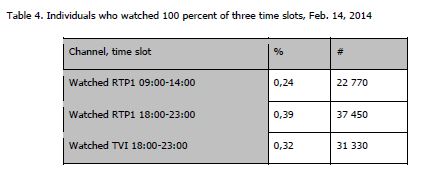

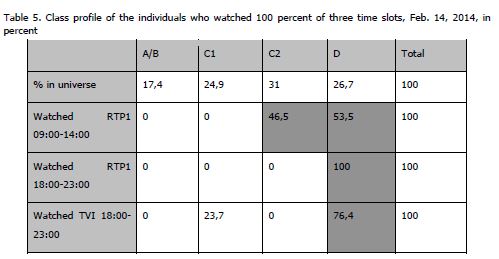

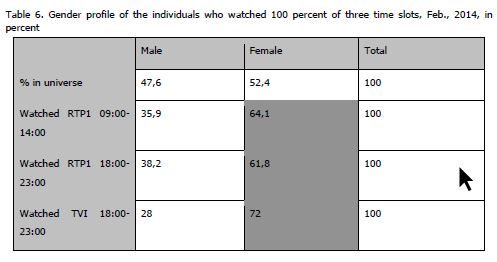

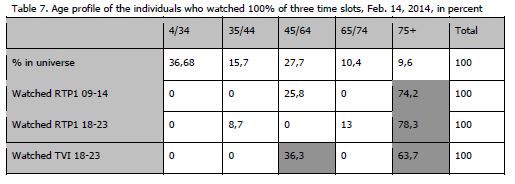

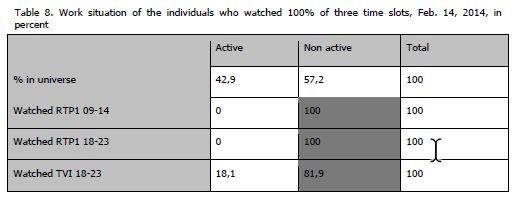

Let us look in more detail at the faithful to flow. Although the number of cases of viewers in the sample watching the same channel without interruption is small, the socio-demographic characterisation gives us clear signs of the faithful. I chose examples, shown in Tables 4 to 8, identifying the viewers who watched RTP1 from 9:00 to 13:00, from 18:00 to 23:00 and TVI from 18:00 to 23:00, on 14 February. They represent less than 0.40 percent of the total universe of 9,684,280 people. The majority belongs to the lower socio-demographic class, D, and also C2 in one of the examples. No one from classes A/B and C1 watched RTP1 without interruption in the examples chosen; in the TVI example, 76,4 percent came from class D. Two-thirds were women. No one younger than thirty-five watched these three time slots; three quarters were older than seventy-four in all cases. All of them were non active persons (retired, unemployed) in the two RTP1 examples and 82 percent in the TVI example. In short, in these examples the viewers faithful to flow are mainly old, non active, women, from the lower socio-demographic classes. They are the “old faithful”. The flow experience was unknown to the other audience targets.

In the following examples we can verify the faithfulness level of audiences inside programmes themselves, considering neither the flow connecting with contiguous programmes nor the faithfulness to the commercial breaks. The first programme I chose was A Tarde É Sua, a TVI daily talk show. The programme had four parts, with three commercial breaks. In total, it lasted for 2:13:55 in the afternoon. The total average rating of the programme (commercial breaks excluded) was 6.1 percent, or 588,900, with only one part exceeding that rating. The programme was watched in its entirety by 103,900, or 6.5 percent of the programme’s reach, the 1,595,400 individuals who watched it for at least one minute.

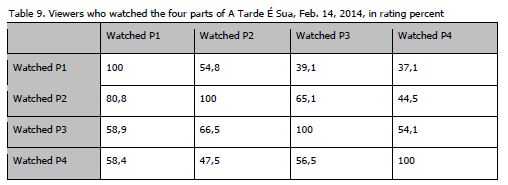

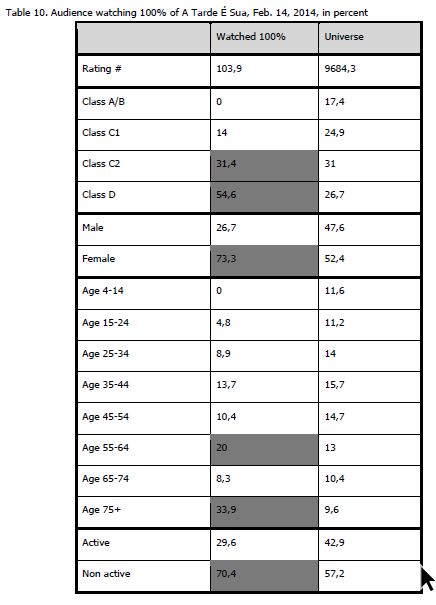

The next analysis checks the amount of viewers that watched each of the parts of the programme and also watched any of the other parts. Table 9 (read vertically) includes the rating in percentage of each part in relation to the attendance of the other parts by the same individuals. The results show great variations in attendance. The talk show had lost in its fourth part 41.6 percent of those who had watched the first part; of those who watched the fourth part, only 37.1 percent had watched the first one. The faithful audience of the programme — the viewers who watched all its four parts - is mainly feminine (73.3 percent), D class (54.6 percent), aged fifty-five or more (62.2 percent) and non active (70.4 percent). Table 10 allows us to compare these data with their actual presence in the universe of the Portuguese population.

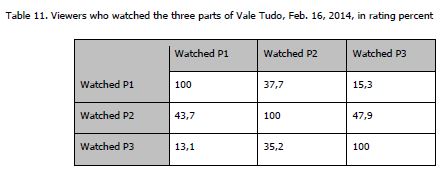

I did the same analysis with the entertainment programme Vale Tudo, beginning its second season Sunday night Feb 16 at SIC.7 It occupied almost all prime time, three hours beginning at 21:22. Vale Tudo attracted an audience different from A Tarde É Sua. It is a programme of pure fun, with celebrities in difficult situations for comic effect. It had a rating of 9.7 percent, or 939,700, reaching 3,050,800 people, who watched at least one minute. Like A Tarde É Sua, it had four parts, but the last took only 19 seconds. Looking at the three parts with action contents, only 13.1 percent of those who watched the first part watched also the third part (Table 11). The reverse is similar: of the viewers who watched the third part, only 15.3 percent had watched the first part. Although more than 3m people watched at least one minute of the programme, only 300,600 watched the whole first part, and of those, only 39,200 watched also the whole third.

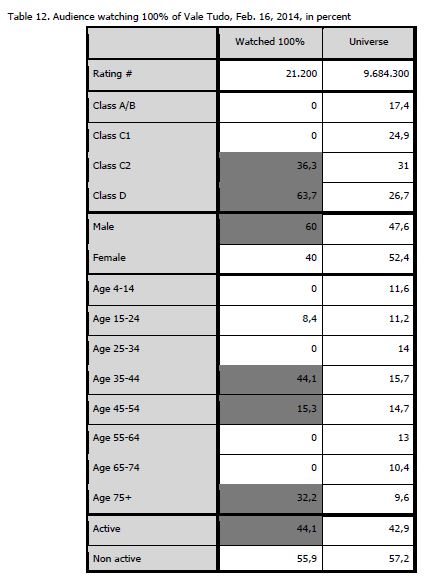

Unlike A Tarde É Sua, this programme attracts younger people: more than half (52.5 percent) were forty-four or less. And more than a quarter (22.8 percent) was in the age groups four-fourteen (11.6 percent) and fifteen-twenty-four (11.2 percent). But, checking the flow audience — those who watched the entire show —, we see that younger groups have lesser ratings than the same groups in the universe. The largest acceptance of the flow character of the programme comes from age groups thirty-five-forty-four, seventy-five or more and forty-five-fifty-four (Table 12). Regarding class, the adhesion to flow was larger in class D than in the others. Although the average rating was 939,700 and the reach was 3,050,800, only 21,200 viewers, or 2,6 percent of the average rating of the programme, and less than 0.7 percent of the reach, watched the complete programme (commercial breaks not included). Two-thirds were from class D (63.7 percent), more men than women watched it (60.0 percent), more than half were non active (55.9 percent) and only 8.4 percent were under thirty-five years old.

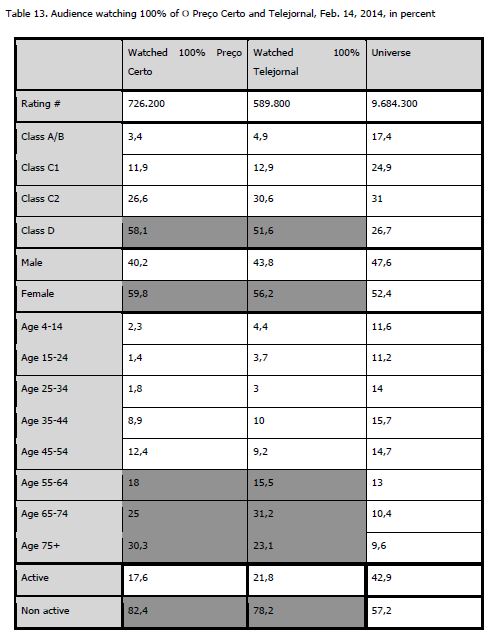

As mentioned above, Preço Certo is frequently singled out as a programme allowing RTP1 to keep its audience to the next programme, Telejornal. Since a lot of experts, politicians and commentators vabe considered in press articles that Preço Certo does not fit a public service programming, ideological supporters of RTP use it as an example of a correct choice to fix audiences in the public broadcaster main channel, thus defending it as a programming correct choice. Table 13 tests this common idea of Preço Certo fixing the audience of the primetime access time slot to the primetime. On Feb. 14, Preço Certo attracted an average rating of 12.8 percent. Telejornal had a slightly lower average rating, 12.3 percent. Preço Certo was watched in its entirety by a high number of viewers, 726,000, corresponding to 40.1 percent of the reach. The following programme, Telejornal, had a faithful audience of 589,800 viewers, corresponding to 26.4 percent of the reach. How did the flow worked between the two programmes? Of the 726,000 who watched the entire Preço Certo, 389,100 also watched the entire Telejornal, that is, more than half of the viewers (53.6 percent) that watched Preço Certo from the beginning stayed tuned to RTP1 until at least the end of Telejornal. The 389,100 who watched both programmes represent 66.0 percent of those watching Telejornal entirely: the majority of the faithful Telejornal viewers were also faithful Preço Certo viewers. Thus, in this case, flow is a real practice of an important part of RTP1 viewers at this time of day, or shall we say, of these two programmes. Who are the faithful viewers of the two programmes (Table 13)? The faithful to Preço Certo e Telejornal have identical profiles: 58.1 and 51.6 percent came from class D, 26.6 and 30.6 percent from class C, or 84.7 and 82.2 percent in total from the lower socio-demographic classes; the majority were women (59.8 and 56.2 percent) and were sixty-five year old or more (55.3 and 54.3 percent); the vast majority were non active (82.4 and 78.2 percent).

I tested a last check of faithfulness analysing the relation between those who saw two self promotions of Vale Tudo and also watched at least one minute of the programme. Self promotions may in fact attract viewers, or at least they coincide in viewing the show after watching the promotions (Table 14). For instance, of the 109,100 viewers who watched Vale Tudo promotion in SIC at 10:28, around eleven hours before the programme began, 51.7 percent watched at least one minute of the programme. The same proportion (50.5 percent) is found among the 673,200 viewers who watched the self promotion at 13:51, around seven and a half hours before the programme began. These data seem to indicate that there is a faithfulness to the channel, to its brand, but not necessarily to its flow. In any case, we are far from a massive coincidence of audiences of self promotions and programme promoted, since Vale Tudo had a total reach of 3,050,800 viewers and an average rating of 939,700.

Conclusions

The flow theory began as a result of commercial television marketing and content practices of connecting programmes breaks and including continuous references to other programmes of the same channel in the golden age of broadcast, at a time of inexistent or extremely limited alternatives. Today flow is still a widely used discourse and scheduling practice of broadcast, either State or privately owned, and also of cable channels. It is part of their marketing discourse: in average each of the four free-to-air Portuguese channels presented eighty-one self promotions per day just in commercial breaks, or almost forty-one minutes per channel during the week of May 19-25, 2014.8 Flow also originated an ideology of State public service television, according to which the State operator should maintain “low quality” programmes, of limited or null public interest contents, in order to keep its grip over audiences and, in consequence, a certain share to legitimise its existence and public funding.

Going back to the ontology of broadcast television helps explain its persistence flow discourse when most viewers do not abide to it: television as a media occupies time, and time flows; a channel has a timeline, a narrative, like a human being giving a certain unity to daily life created by the individual’s identity. In the case of a TV channel, that identity is the brand, and the brand, transmitting all day, wishes to present itself with an identity and a logic, in order to capture viewers, translated to flow discourse and practices. Adding to this the personalization of the brand in communication made by self promotions and presenters, mostly based in the mode of public address, the flow discourse and practice by broadcasters is a “natural” consequence of the media’s ontology.

Using audience ratings examples, this research shows that, while being an ideology practiced by broadcasters, flow is not an extended audience practice. The large majority of viewers are not faithful to programmes’ or channels’ flow. Persistent viewing of the same channel, either in time slots of several hours or inside the same programme, is statistically negligible. Still, we saw an example between consecutive programmes where flow is a practice of approximately half their viewers, clearly identified with the less dynamic socio-demographic groups. The viewers faithful to flow in that case are mainly old, women, non active and classes D and C2, the targets specially sought by flow discourse since they constitute the larger audience groups. Younger, more affluent and active audiences are zapping practitioners, unfaithful to flow ideology. In any case, flow audiences contribute to better ratings and share; while not increasing advertising revenues, they improve other revenues, as the generated by premium-rate telephone calls, and guarantee national relevance to the programmes.

For broadcasters, aware of the fragmented viewing practices, it is understandable that any gain from flow marketing contents and from a “logic” sequence of programmes to maintain audiences in the channel is a valuable gain in the overall audience ratings and shares. It is also understandable that broadcasters use flow ideology as a marketing device to attract viewers to their scheduling. As a discourse, flow assumes an “imagined family” (Hatch, 2002: 76) and the fictional idea that viewers are watching and will watch the same channel all day. Broadcasters, programmers, schedulers and audiences alike know that this is not true. What is unexpected is that television studies academics may use an ideological and marketing discourse to defend a State public service programming strategy including programmes with no public interest based on the flow ideology.

This article was based on a number of examples; more data exploration is needed, creating stable statistical series in the same path. Also, other venues of research could be explored, like second by second channel switching, the collective viewing in the household and relation between them: it is expected that zapping is less frequent in family viewing practice (a reality that is diminishing, although not measured), but it remains to be tested; viewers’ “multi-platform flow” should also be tested when the television industry will put in place measuring techniques not in existence in the time of writing. In any case, the data explored here indicate that Television Studies should pay more attention to the gigantic amount of audience ratings data available.

Bibliographical references

Bjur, J. 2009. Transforming Audiences. Gothenburg: University of Gothenburg. [ Links ]

Browne, Nick. 1987. “The Political Economy of the Television (Super) Text”. In Television: The Critical View, 4th ed., edited by Horace Newcomb, 585-99. New York, Oxford University Press.

Brunsdon, C. 1990. “Television: Aesthetics and Audiences”. In Logics of Television, edited by P. Mellencamp, 59-72. Bloomington and London: Indiana University Press.

Brunsdon, Charlotte. 2010. “Bingeing on Box-Sets: The National and the Digital in Television Crime Drama”. In Relocating Television, edited by Josstein Gripsrud, 63-75. London and New York: Routledge.

Budd, M., and C. Steinman. 1989. “Television, Cultural Studies, and the ‘Blind Spot’ Debate in Critical Communications Research”. In Television Studies, edited by G. Burns and R. J. Thompson, 10-20. New York, Praeger.

Bulck, Hilde Van de, and Gunn Sara Enli. 2014. “Flow under Pressure: Television Scheduling and Continuity Techniques as Victims of Media Convergence?”. In Television and New Media, July, 15: 449-52.

Caldwell, J. (1995) Televisuality. New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press. [ Links ]

Casey, B., N. Casey, B. Calvert, L. French and J. Lewis. 2002. Television Studies. The Key Concepts. London: Routledge. [ Links ]

Ellis, J.. 1982. Visible Fictions. London: Routledge. [ Links ]

Ellis, J. 2000. “Scheduling: the Last Creative Act in Television”. Media, Culture and Society, 22 (1): 25-38.

Epstein, E. J.. 1973. News From Nowhere. New York: Vintage Books. [ Links ]

Gray, Jonathan, and Amanda D. Lotz. 2012. Television Studies. Cambridge and Malden: Polity. [ Links ]

Gripsrud, Jostein. 2002. Understanding Media Culture. London: Arnold. [ Links ]

Hatch, K. 2002. “Daytime Politics: Kefauver, McCarthy, and the American Housewife”. In J. Friedman, ed., Reality Squared, edited by J. Friedman, 75-91. New Brunswick and London,:Rutgers University Press.

Heath, S. 1990. “Representing Television”. In Logics of Television, edited by P. Mellencamp, 267-302. Bloomington and London: Indiana University Press.

Klein-Shagrir, Oranit. 2014. “Public Service Television in a Multi-Platform Environment. A Comparative Study in Finland and Israel.” View, Vol.3 Issue 6, 14-23. Accessed December 12, 2016, http://viewjournal.eu/index.php/view/article/view/JETHC066/162

Lopes, F., L. M. Loureiro and I. Neto. 2013. “O Ecrã da (Hiper) Televisão: Novos Olhares a Partir das Emissões Dedicadas ao Euro 2012 na TV Portuguesa”. Observatorio (OBS*) Journal 7 -no3: 035-057.

Lotz, Amanda D. 2014. The Television Will Be Revolutionized. 2nd ed. New York and London: New York University Press. [ Links ]

Mellencamp, Patricia. 1990. “TV Time and Catastrophe, or Beyond the Pleasure Principle of Television”. In Logics of Television, edited by Patricia Mellencamp, 240-66. Bloomington and London: Indiana University Press.

Miège, Bernard. 1989. The Capitalization of Cultural Production. New York: International General. [ Links ]

Newcomb, Horace, and P. M. Hirsch. 2000. “Television as a Cultural Form”. In H. Newcomb, Television. The Critical View, 6th ed., edited by H. Newcomb, 561-73. New York and Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Paterson, R. 1990. “A Suitable Schedule for the Family”. In Understanding Television, edited by A. Goodwin and G. Whannel, 30-41. London: Routledge.

Spigel, Lynn. 1992. Make Room for TV. Chicago and London: University of Chicago Press. [ Links ]

Suárez-Candel, Roberto. 2012. Adapting Public Serve to the Multiplatform Scenario: Challenges, Opportunities and Risks. Hamburg: Hans-Bredow-Institut. Accessed December 8, 2016, https://www.hans-bredow-institut.de/webfm_send/661

Theodoropoulou, Vivi. “Convergent Television and ‘Audience Participation’. The Early Days of Interactive Digital Television in the UK. View, Vol.3, Issue 6, 69-77. Accessed December 7, 2016, http://viewjournal.eu/index.php/view/article/view/JETHC071/171

Thompson, Ethan. 2013. “Onion News Network: Flow”. In How to Watch Television, edited by E. Thompson and Jason Mittell, 2981-99. New York and London: New York University Press.

Torres, Eduardo Cintra. 2006. A Tragédia Televisiva. Lisboa: ICS. [ Links ]

Uricchio, William. 2004. “Television’s Next Generation: Technology/Interface Culture/Flow”. In Television after TV, edited by. L. Spigel and J. Olsson, 232-61. Durham: Duke University Press.

Uricchio, William. 2009. “Contextualizing the Broadcast Era: Nation, Commerce, and Constraint”. The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science: 60-73.

Uricchio, William. 2010. “TV as Time Machine: Television’s Changing Heterochronic Regimes and the Production of History”. In Relocating Television, edited by Jostein Gripsrud, 27-40. London and New York: Routledge.

Williams, R. 1992. Television: Technology and Cultural Form. Intr. L. Spiegel. Hanover and London: Wesleyan University Press.

NOTES

1 Archives of television flow can be vital to perform the textual analysis of certain phenomena, like the tragic events studied in A Tragédia Televisiva (Torres 2006), using non-professional VHS tapes with 24/24 hours of RTP1 emission, preserved at the Arquivo da RTP.

2 Information provided by TVI professionals to the author.

3 The flow ideology is imbedded in self promotions and presenters‘ discourse. For instance, the presenter of a RTP’s talk show on March 7, 2014 urged the viewer: “you should stay with RTP all day today”.

4 I express my deep gratitude to Marktest Audimetria / Kantar Media for providing the data I asked, specially to Manuel Monteiro, Technical Director, and for his time and patience. This article would not have been possible without Marktest Audimetria / Kantar Media and Manuel Monteiro’s help.

5 I excluded from the analysis the parliament channel, introduced in the free-to-air digital offer. It has negligible ratings, less than 1,000 viewers per day in 2015.

6 On the 10th of February, 2011, following a market decision, Markest Audimetria changed counting the reach in a second by second to a minute by minute measurement. The data of second by second are an excellent statistic indication of instant zapping, while the minute by minute data (that is, more than 30 seconds viewing a channel) indicate a more consistent decision to leave one channel for another.

7 The choice of a programme in a different day was due to its entertainment character and the wish to have an analysis of a SIC programme. On Feb 14, 2014, SIC did not show any programme of that kind.

8 Data provided at my request by Marktest Audimetria / Kantar Media.