Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Acessos

Acessos

Links relacionados

-

Similares em

SciELO

Similares em

SciELO

Compartilhar

Observatorio (OBS*)

versão On-line ISSN 1646-5954

OBS* vol.10 no.2 Lisboa abr. 2016

ARTIGO ORIGINAL

Television sex education panics? An analysis of three public debates in The Netherlands

Anouk Mols*

Erasmus University Rotterdam, Burgemeester Oudlaan 50, 3062 PA Rotterdam, Netherlands (mols@eshcc.eur.nl)

ABSTRACT

In 2013, television sex education show Dokter Corrie instigated a heated public debate in the Netherlands. This study places the Dokter Corrie uproar in a broader perspective and identifies the moral dimensions in the reactions to three Dutch television sex education shows: Open en Bloot (1974), Spuiten en Slikken (2005) and Dokter Corrie (2013). A contemporary notion of moral panics and media panics provides a suitable theoretical basis for understanding the multiplicity of voices, the reflexive relationships between interest groups and the deliberate use of media tools in the debates about Dutch television sex education. The qualitative frame analysis and quantitative content analysis led to a detailed account of the three public debates and showed that moral attitudes concerning the problematic conditions of television sex education recurred over time. The resulting four frames each revolve around the claim that sex education needs to be handled carefully. The Indispensable education frame and the Inadequate attempt frame regard television as the right channel for this goal. In contrast, voices within the Degenerating media frame and the Religious anxiety frame claim that television sex education threatens the social sexualisation of children.

Keywords television sex education, media panic, public debate, sexual morality, framing.

Introduction

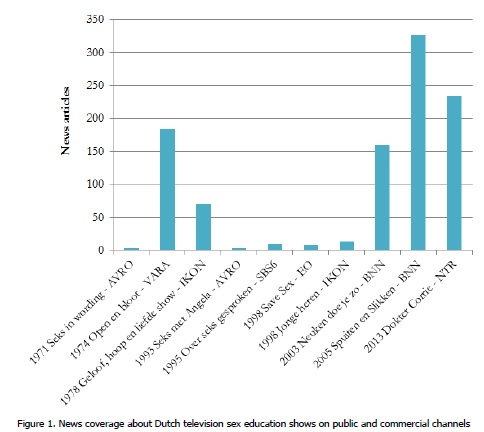

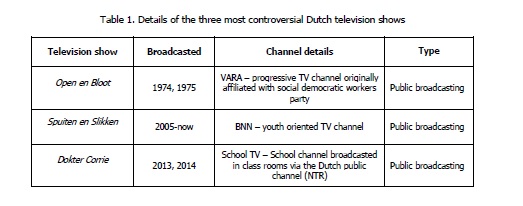

In November 2013, Dutch parents presented a petition to the Dutch parliament with 8.000 signatures to stop the broadcasting of Dokter Corrie (translation: Doctor Corrie, NTR, 2013), a weekly item on the national school channel. In her show, Dokter Corrie offers sex education in a playful manner. Christian, Islamic and non-religious parents united in a collective of worried parents (Reformatorisch Dagblad, 2013). The collective feared that their children would be confronted with inappropriate ideas about sex, and argued that sex education needs to be handled carefully in a safe environment instead of in an entertaining television show (Bol and Van Soest, 2013). Their arguments were opposed by sexologists and by the producers of the show who stated that Dokter Corries playful tone initiated a necessary discussion about sexuality (Heerlien, 2013), and that the show provided useful tools to start this discussion (Van Paridon, 2013). When parliamentary questions about the content of Dokter Corrie were posed by a Christian politician, the Dutch parliament expressed their confidence in the school television channel (De Telegraaf, 2013). The debate about Dokter Corrie shows the characteristics of a classic media panic. Media panics are phases of public consternation about the introduction of a new medium or a specific media production (Biltereyst, 2004). The emotionally charged discussions focus primarily on the effect of media on children and young people and are morally polarised (Drotner, 1992). This study presents a contextual notion of moral attitudes towards television sex education in the Netherlands. Context is provided through an overview of the history of Dutch television sex education and via the analysis of public debates about controversial television shows. Figure 1 shows that Open en Bloot (translation: Open and Naked, Vara, 1974), Spuiten en Slikken (translation: Shoot and Swallow, BNN, 2005) and Dokter Corrie caused an outstandingly large amount of news coverage. Therefore, these three television shows are selected for an analysis of moral attitudes in Dutch public debates about television sex education. Details of the shows are included in Table 1. Public debates revolve around attitudes and opinions; socially constructed accounts of a topic or event influenced by life histories, social interactions and psychological predispositions (Gamson & Mogdigliani, 1989). In this paper, I aim offer a comprehensive overview of the prevailing attitudes and opinions in public debates about Dutch television sex education. The guiding research question is: Which moral dimensions are present in the public debates about Dutch television sex education shows Dokter Corrie, Open en Bloot and Spuiten en Slikken, and can these be typified as media panics?[1]

While prior studies about television sex education touch upon moral attitudes, researchers primarily concentrate on specific content (Boynton, 2006, 2007) and audience reactions (Diamond, 1979; Gunter, 2009; Overste, 1974). This study focuses on the moral dimensions of public debates about television sex education and builds on media panic theory (Drotner, 1992; Biltereyst, 2004) to provide a unique examination of the debates and to address central concerns about society, children and morality. This study contributes to the academic understanding of media panics by means of a descriptive quantitative analysis and a qualitative frame analysis. The findings are relevant for societal groups engaged in public debates about sex education. Television producers, television producers and sexual education organisations (for example Rutgers WPF, SOAIDS and GGD Nederland) are offered an in-depth overview of the moral concerns and actors in public debates about television sex education. To contextualise the topic at hand, the analysis is preceded by a description of the Dutch context of television sex education, based on secondary literature and expert interviews with producers of the shows and media experts. These experts formally approved of

The Dutch context

The sexual revolution

In the Netherlands, television sex education was introduced in the seventies. According to Schnabel (1990), this was during the sexual revolution. The Dutch sexual revolution took place in the late 1960s and early 1970s, similar to other Western countries (Hekma and Giami, 2014). In Europe, the sexual revolution started in Scandinavian countries and expanded to the Netherlands, England and Germany, before it spread to Southern Europe (Hekma & Giami, 2014). Schnabel (1990) describes the sexual revolution as a period that was mainly driven by mass media and ideological organisations. A process of normalisation took place whereby the public notion of sex shifted from innocence, guilt and mystery to the idea of sex as a normal, fun and pleasurable act (Schnabel, 1990). According to Buijs et al. (2013), the sexual revolution was a paradoxical process full of contradictory ideologies. The celebration of liberated, free and harmless sexuality was short-lived. Soon, the drawbacks of sex prevailed in the public debate and sexual education became a social issue (Schnabel, 1990).

The history of Dutch television sex education

In 1971, Sex in Wording translation: Sex in the making, AVRO, 1971) was broadcasted, the first Dutch television sex education show. The show featured several doctors in a medical setting who treated sex as a health issue (Geelen, 2003, Feb. 22). Open en Bloot was broadcasted in 1974, this show radically opposed Sex in Wording as it presented sex as an ordinary activity. The shows title sequence contained an alphabet of naked people and the presenters encouraged the use of explicit language. The producers of the show claimed that sex can be pleasurable, fun and liberating, but that it is important to be aware of the consequences (Van Lieshout and van Schaik, 1994). According to Hedda van Gennep, producer of Open en Bloot, the show received many reactions in the form of letters and phone calls. Most reactions came from audience members in search of information about the topics discussed in the show (personal communication, May 7, 2014). News magazine Vrij Nederland stated that reactions via the telephone were primarily positive, while letters from viewers were mainly negative. The most prevalent complaint concerned the use of explicit language (Vrij Nederland, 1994).

While the producers stated that the show was aimed at anyone willing to watch (Van Lieshout & Van Schaik, 1974, p. 7), Open en Bloot was broadcasted around 10 PM. Hence, it is safe to assume that the show was targeted at young adults and adults. Television show host Koos Postema describes the early 1970s in the Netherlands as an era of openness wherein sexuality was freely discussed. This mentality is visible in the straightforward manner in which Open en Bloot discussed sexuality (Postema, personal communication, May 30, 2014). However, television producer Bert van der Veer states that many people watched Open en Bloot with closed curtains (personal communication, May 10, 2014). Postema and Van der Veers ideas indicate a contradiction between a notion of sexual freedom and feelings of shame.

Other Dutch television sex education shows are Geloof, hoop en liefde show (translation: Faith, hope and love show, IKON, 1978), Sex met Angela (translation: Sex with Angela, AVRO, 1993), Over seks gesproken (translation: Speaking of sex, SBS6, 1995), Save Sex (EO, 1998), Jonge heren (translation: Young Men, IKON, 1998), and Neuken doe je zo (translation: Fucking goes like this, BNN, 2003). While Neuken doe je zo led to a fair amount of reactions due to its open discussion about a variety of sexual topics, Figure 1 illustrates that news coverage broke all records in 2005 when BNN announced to broadcast an educational television show featuring live drugs and sex experiments (De Jong and Langeslag, 2005). Television expert Geelen believes that the show instigated a heated debate because the sex experiments were very explicit and quite extreme" (personal communication, May 22, 2014). Spuiten en Slikken is targeted at young adults, the shows website states that the content is not appropriate for anyone younger than 16 years old (BNN, 2014).

Up until 2013, most television sex education shows[2] were directed at adolescents and young adults. In December 2012, the Dutch government established sex education as one of the core objectives for primary education. Sex education became mandatory by law (Rijksoverheid, 2012). Dokter Corrie was broadcasted on the national school channel to provide elementary school teachers with tools to address sexuality in class (Van Paridon, 2013). Dokter Corrie producer Juliette van Paridon stated that, while the public debate about the show mainly revolved around the concerns of worried parents, the producers received many positive reactions from children and educators (personal communication, May 26, 2014). Since 2015, Dokter Corrie has been aired on Zapp, a Dutch public broadcasting channel targeted at children. The show is no longer broadcasted in schools.

Literature

This paragraph provides an introduction to research about television sex education and audience reactions, which addresses personal and general attitudes towards television sex education. Because these attitudes display strong moral attitudes, moral panics and media panics are presented as guiding concepts for the content analysis.

Sex education television research: sexperts and audience reactions

Content-oriented studies about television sex education address different types of media. Boynton (2007) critically analysed sex education content on television and in magazines. She claims that media sex advisors often lack knowledge. Therefore, she calls them sexperts; sex educators without an informed background whose education is neither critical, nor evidence-based (Boynton, 2006). Focusing on television musical drama, Prior (2013) criticises the educational value of Glee (Murphey et al., 2009), a show that is condemned as well as acclaimed for its approach to sex and sexuality in high school. She notes that, while the show mocks sex education lessons and challenges existing notions of teen sexuality, it fails to address important topics like consent and coercion (Prior, 2013).

Apart from the analytical approach of Boynton (2006, 2007) and Prior (2013), audience reactions are key to television sex education studies. Diamond (1979) presents an overview of letters-to-the-editor in Hawaiian newspapers about Human Sexuality (PBS, 1973). He describes that the few negative reactions were outweighed by many appreciative responses (Diamond, 1979). In addition, United Kingdom panel research about Sex Talk (Channel4, 1985) showed that explicit images and sex-related topics in the show led to relatively moderate audience reactions (Wober, 1990, as cited in Gunter, 2009). Similarly, focus groups that were conducted in New Zealand about Sex (Clucas, 1992) showed predominantly positive reactions. Only a small portion of the respondents felt embarrassed by the subject matter because of the explicit nudity and controversial topics (Watson, 1993, as cited in Gunter, 2009). Furthermore, audience reactions were examined outside of the academic field. For instance, the day-time scheduling and explicit presentation style of Love bites (LWT, 1998) were prevalent in thirteen formal complaints received by a UK media watchdog (Ofcom, 1998). While Open en Bloot provoked many negative responses (Vara, 2013), Koolhaas states that the bulk of the reactions was positive (2013, Nov. 20). In 1974, the Dutch public broadcasting organisation published four reports about Open en Bloot (Overste, 1974a,b,c,d). These reports confirm that the audience was mainly positive. However, complaints addressed the use of explicit language and the reassuring and trivialising tone towards sex issues (Overste, 1974a).

Moral dimensions

The aforementioned studies and reports touch upon moral beliefs and fears of audience members. Moral beliefs and fears are key ingredients of moral panics. A classic text about moral panics is written by Cohen (1971), who defined them as periods in which a condition, episode, person or group is defined as a folk devil; a deviant actor who poses a threat to societal values and interests (Cohen, 1971). An example of a classic moral panic study is Hall et al.s (1978) analysis a large-scale moral panic about mugging that was incited by the robbery and murder of one elderly man. Groups of (coloured) youths were designated as a folk devil in the newspapers while there was no evidence of increased mugging rates (Hall et al., 1978). Critcher (2006) claims that moral panics occur when the core moral values of a society are unsettled by an identifiable enemy and societal actors need a reconfirmation of moral values. The classic folk devil-theory is challenged by Ungar (2001), who proposes a contemporary notion of moral panics that involves reflexive relationships between diverse interest groups. Ungars approach emphasises the possibilities for enemies to offer resistance (2001). In addition, David et al. (2011) argue that present-day moral panics are less in need of folk devils because they concern issues that are often depersonalised and more diffuse than before. Moreover, McRobbie and Thornton (1995) state that a proliferation of voices and an increase of media strategies shook up the original moral panic concept. More participants are involved in public debates that contain a multiplicity of voices. Media no longer rely on established voices, as they incorporate different agencies, interest groups and experts to provide opposing perspectives (McRobbie, 1994). Consequently, recent moral panics became less monolithic than the classic model suggests (McRobbie & Thornton, 1995). Contemporary panic debates are characterised by various opposing voices that speak from different positions and are aware of the use of effective strategies to get their message across (McRobbie, 1994). Whereas moral panics once were an unintended outcome of journalistic practice, they now became a ubiquitous goal and a media tool for actors to make social issues newsworthy (McRobbie & Thornton, 1995). According to Goode and Ben-Yehuda (2009), contemporary moral panics are almost always instigated by certain actors. These actors are coined moral entrepreneurs; individuals or groups of people that create the crusade of a folk devil. Moral entrepreneurs make an effort to influence public opinion, form alliances, or generate social movements. They inform the public and attempt to involve educators and legislators in their crusade (Goode & Ben-Yehuda, 2009).

This study provides an in-depth understanding of the moral dimensions of the public debates about Dutch television sex education shows. With a focus on the societal values and interests under threat (Cohen, 1971), the analysis maps the various voices in the debates (McRobbie & Thornton, 1995), and assesses if moral entrepreneurs (Goode & Ben-Yehuda, 2009) are present. The conclusion reflects on the question whether the debates are targeted at identifiable enemies (Critcher, 2006) or folk devils (Cohen, 1971), or if the issues are depersonalised (David et al., 2011). Media panics

Media not only function as a strategic field for moral panics, but are also often regarded as threats to society. New types of media and media content became folk devils. Biltereyst (2004) states that media panics are moral panics based on media subjects, which address a variety of different opposing actors. These phases of public consternation are concerned with the introduction of a new medium or novel media content (Biltereyst, 2004). According to Drotner (1992), media panics reveal broader problems and touch upon cultural quality, personal development, and social change issues. Emotionally charged media panics focus primarily on children and young people and are morally polarised. The negative pole is often most visible in a classic media panic cycle which contains a single instigating case, a peak revolving around a public or professional intervention and a fading-out phase with a seeming resolution (Drotner, 1992). The opposition between form and content is crucial in media panics: voices are raised in the name of reason, but express a language of emotions loaded with metaphors and symbolism. Drotner claims that the symbolism in media panics often relates to bodily functions, food, and sexuality; media is described as indecent, seductive, and junk food (1992, p. 615).

Media panic theory functions as a starting point to obtain a contextual notion of the moral attitudes towards television sex education because it addresses both the media at hand and the debates underlying beliefs and attitudes. In the analysis of the reactions to television sex education in the Netherlands, I examine the different phases of the debates whereby I identify metaphors and symbolism (following Drotner, 1992).

Methods

To enable a detailed account of the debates about Open en Bloot, Spuiten en Slikken and Dokter Corrie, and to examine whether they can be typified as media panics, I combined a quantitative descriptive analysis and a qualitative frame analysis.

Data

According to Ungar (2001), contemporary moral panics transcend traditional media coverage because media producers are several steps removed from the general public (2001, p. 279). The data collection aims to capture comprehensive public debates. Therefore, both traditional media (offline, traditional news sources) and opinions of the general public (as voiced in online media and in letters-to-the-editor) are included. The public discussions about Spuiten en Slikken and Dokter Corrie are recent phenomena and these debates took partially place online. For these debates all retrievable written offline and online media content was gathered. For Open en Bloot, newspaper archives were consulted. The corpus (see Table 2) contains all offline newspaper articles that were available from Dutch national news sources in news database LexisNexis and from the newspaper collection of the Koninklijke Bibliotheek (quality newspapers, popular newspapers, regional newspapers, free newspapers, newsmagazines and wire service reports). These results included news articles, profiles, interviews, reviews, letters-to-the-editor, opinions and editorial comments. The online search results contain blogposts, forum threads, and columns on opinionated websites.[3]

The articles about Open en Bloot were collected via Delpher.nl, an online database with the historical collection of the Koninklijke Bibliotheek. The search terms used were: open en bloot and open & bloot. Articles about the two recent television sex education shows were collected in a two-fold search. First, the offline articles were retrieved from the news database LexisNexis. The search terms used were Spuiten en Slikken, Spuiten & Slikken, Dokter Corrie and Dr. Corrie. Afterwards, a comparable Google-search was carried out. The time collection periods varied for each television show. For Open en Bloot, all reactions were collected over a time period of six months (one before and five after the first broadcast), because the episodes were broadcasted on a monthly basis. Press releases which announced the first episode of Spuiten en Slikken caused quite a stir beforehand. Therefore, all articles were selected that were published in the one month before and the two months after the first broadcast. Because Dokter Corrie was not mentioned until two weeks after the first broadcast, the data collection time period spanned the three months after the first broadcast. Not all search results proved to be noteworthy; sometimes only the title of the television show was mentioned, and in other cases the title referred to something unrelated to the television show. Hence, irrelevant results were omitted. While the corpus is extensive, I cannot fully guarantee completeness due to the dependency on (historical) databases and the volatile nature of the internet.

Qualitative frame analysis

To identify different opinions, attitudes and moral aspects in the public debates, a qualitative frame analysis was carried out. There are multiple explanations of framing and frame analysis within media and communication studies (see Vliegenthart and Van Zoonen, 2011). In this study, I apply Gitlins (1980) definition of frames as principles of selection, emphasis and presentation composed of little tacit theories about what exists, what happens, and what matters, that organise the world both for journalists who report it and, in some important degree, for us who rely on their reports (Gitlin, 1980, p. 6). An important distinction is made between two different types of frames, namely substantive (Entman, 2004) or advocacy (De Vreese, 2012) frames and procedural (Entman, 2004) or journalistic (De Vreese, 2012) frames. Substantive/advocacy frames are provided by a variety of actors in debates (De Vreese, 2012). They focus on problematic conditions or effects of specific causes, they suggest improvements, and often convey a moral judgment (Entman, 2004). These content oriented frames are opposed by procedural/journalistic frames focused on evaluating political actors legitimacy (Entman, 2004) and political strategies (De Vreese, 2012). The analysis at hand focuses on frames as presented in public debates whereby substantive/advocacy frames are to be expected.

The research method at hand is an inductive frame analysis (following Van Gorp, 2007, inspired by grounded theory by Strauss and Corbin, 1990). Inductive frame analysis enables an examination of the origin, relevance and cultural context of both the issue at stake and the respective frames (Van Gorp, 2007). The qualitative frame analysis was carried out in a three-step procedure with 60 articles (a representative sample which included articles from all three debates). First, all meaningful text elements were listed. These are the framing devices; metaphors, examples, catchphrases, depictions and visual images (Gamson & Mogdigliani, 1989). For example, phrases like artificial openness and cultural decay. Second, these devices were clustered in a frame matrix and complemented with reasoning devices. Reasoning devices concern causes and consequences (Gamson & Mogdigliani, 1989), as visible in explicit and implicit statements from the texts (for example sex education is a parental duty). In the final stage, the clusters were labelled. In the results section, I present thick descriptions of the four resulting frames. This approach is based on Geertz (1973) notion of thick descriptions which is aimed at capturing the complex nature of culture and interpreting the role of culture in collective life. Ponteretto (2006) states that thick descriptions require both descriptive and interpretative attention whereby the context, motivations, intentions and (inter)relations are taken into consideration to create thick meaning (Ponteretto, 2006, p. 543). Thick descriptions of the frames address the specific contexts whereby the opposing voices and different positions in the debates are examined.

Quantitative analysis

The complete data set of 316 articles formed the basis of the quantitative descriptive analysis. First, the author, media type, ideological background of the source and type of reaction were coded. Moreover, the types of actors mentioned were listed and the main topic of the reaction was identified. The main topics were established through an open coding of 60 articles, which resulted in the categories: 1) international attention, 2) political interest in the show, 3) parliamentary questions, 4) specific episode (a specific episode was described), 5) television show in general (reaction about the television show in general), 6) sex education on television (reaction about television sex education in general, displaying a broader scope than discussion of the television show at hand), 7) audience ratings, 8) review of episode (reaction or discussion of a specific review about the show), 9) conflict with TV news organisation (only applicable to Spuiten en Slikken), 10) drugs education (only applicable to Spuiten en Slikken), 11) petition against the show (only applicable to Dokter Corrie), and 12) petition in favour of the show (only applicable to Dokter Corrie). Finally, the most important attitudes were interpreted according to the six frames distilled in the frame analysis.

Quality criteria

The quantitative coding process was operationalised in a detailed coding instruction. And while the general characteristics (such as source) are not open to interpretation, there can be disagreement about the main topic of the reaction and about which frame is visible. Thus, an intercoder reliability test was conducted for these two variables. The test resulted in Cohens Kappa values of .725 (main topic) and .778 (frame), scores that are sufficient for a descriptive analysis (Pallant, 2010).

To establish quality in the qualitative research, thick descriptions of the frames were added which safeguards credibility (following Shenton, 2004). According to Creswell and Miller (2000), thick descriptions provide a detailed and in-depth account of a phenomenon to determine the transferability of the findings to other contexts. The multi-method design of this study functions as a form of triangulation. Shenton (2004) states that different methods can be combined to exploit their respective benefits and to compensate their individual limitations. Besides the combined frame analysis and quantitative analysis, secondary literature (Vrij Nederland, 1974 and Overste, 1994a,b,c,d) was consulted to provide additional information about Open en Bloot (because this was the only debate that took place in offline, traditional media).

Results

In this results section, I present an outline of the debates about Open en Bloot, Spuiten en Slikken and Dokter Corrie focusing on the distribution of the reactions over time, the different voices and the main topics. Subsequently, I explore the moral dimensions of the debates thick descriptions of the four overarching frames.

1974 – Reactions to Open en Bloot

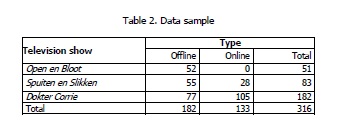

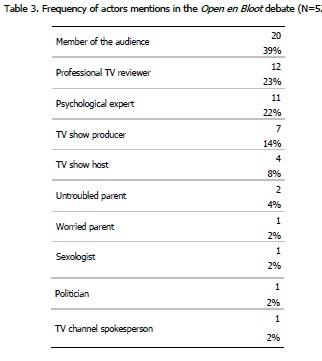

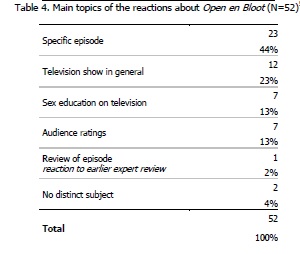

The 1974 debate about Open en Bloot took place offline. Figure 2 shows that the coverage started a week before the first broadcast. These articles introduced Open en Bloot via interviews with the producers and a psychological expert who was part of the production team. Table 3 shows that they belong to the most often mentioned voices in the debate. The first articles focused on the television show in general (see Figure 2) and exclusively mentioned people affiliated with the show. After the first episode, audience members voiced their opinion in letters-to-the-editor and television reviewers criticised and praised the show. Audience members were mentioned in 39% of the reactions. The second peak in Figure 2 contains news coverage about audience ratings. This news was based on the first report by Overste (1974a) and addressed the predominantly positive reactions. Audience ratings were the main topic in 13% of the total news coverage (see Table 4). The third episode generated only one reaction in the newspapers. The audience ratings report of this particular episode stated that 41% of the respondents thought the episode was appropriate for all ages, opposed to much lower scores on this topic for the first two episodes (17% and 22%). Overstes findings (1994c) indicate that this episode was considered less objectionable by the audience. The fourth and fifth episode were only discussed by professional television reviewers. A recurring topic in 13% of the reactions is sex education on television in general (see Table 4). Six out of seven articles addressed this theme in an appreciative tone; these articles discussed sex education, audience attitudes, and the use of explicit language in a constructive manner (see for example Heil, 1974, May 16).[4][5]

2005 – Reactions to Spuiten en Slikken

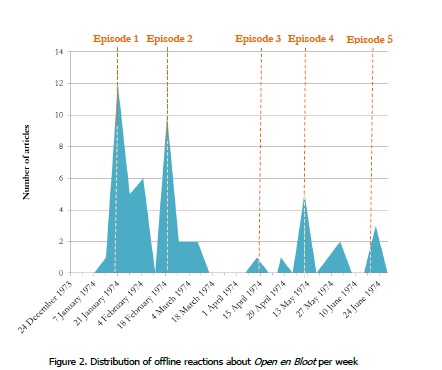

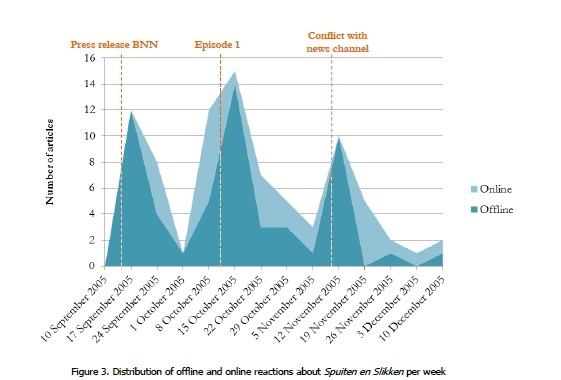

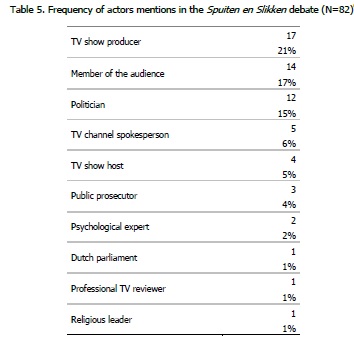

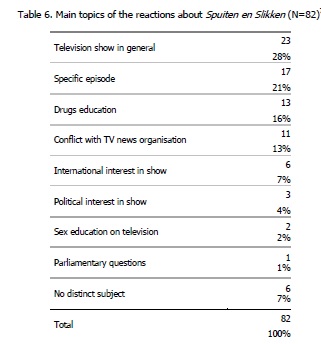

In September 2005, press releases announced Spuiten en Slikken as a show with live sex and drugs experiments. Figure 3 shows that offline sources first responded to the announcement. The wave of reactions shows three distinct peaks. The announcement transcended Dutch borders, newspapers and websites mentioned international interest in the show. Table 5 displays the most prominent voices in the debate. Television producers dominated the reactions in the first peak. Up until October 2005, the reactions were mainly published offline. After the initial excitement died down, the first critiques arrived from politicians that wanted to forbid the drugs experiments. Political concerns formed the main topic of the first online reactions about Spuiten en Slikken. Drugs education is not related to the subject of this study, yet it was important in the debate about Spuiten en Slikken. The political concerns about drugs and reactions to the first episodes were the main topics of the second peak in the wave of reactions, which took place before and after the first episode. After this first episode, the amount of reactions decreased steadily until the second week of November. The third peak of reactions was instigated by a conflict with the television news organisation caused by a practical joke in the episodes (De Telegraaf, 2005, Nov. 23). [6][7]

2013 – Reactions to Dokter Corrie

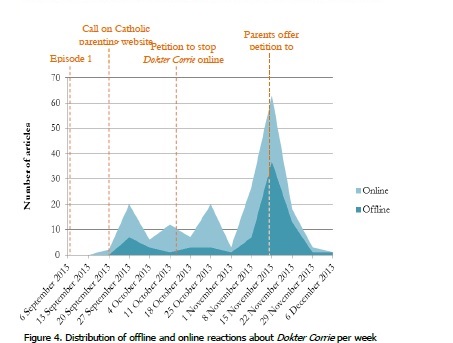

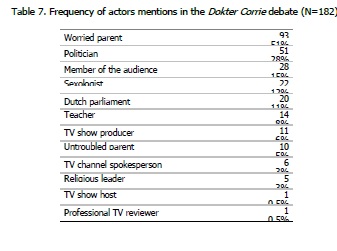

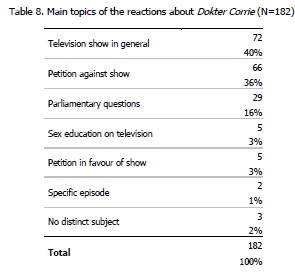

Figure 4 shows that first reactions to Dokter Corrie were published two weeks after the show premiered. That day, a Catholic parenting website called on parents to take action against the school television channel in order to stop the broadcasting of Dokter Corrie (Katholiekgezin, 2013, Sept. 21). Figure 4 displays three smaller peaks of online and offline reactions leading to a zenith almost three months after the first broadcast. Following the call to action, concerned parents published an online petition to stop Dokter Corrie (October 15, 2013). Through the petition, the collective of worried parents pursued a form of public intervention (Drotner, 1992, p. 596), to stop Dokter Corrie. Online media enabled the construction of an easily accessible campaign against Dokter Corrie. These online reactions were subsequently picked up by traditional media. The offline debate grew exponentially in November 2013, when the worried parents offered their petition to the Dutch parliament (Katstra, 2013, Nov. 18). One traditional newspaper with a Christian background covered Dokter Corries opponents extensively; the newspaper offered a stage for the moral entrepreneurs of the Catholic website and the collective of worried parents. Table 7 and Table 8 show that the worried parents dominated the debate; their opinion was mentioned in 51% of the total news coverage and their petition was the second most often used main topic.

Later in the debate, the fear-driven reactions were nuanced by different voices. The third and largest peak in Figure 4 contained arguments countering the worried parents concerns. Producers of the show, the Dutch parliament, untroubled parents and viewers spoke out in favour of Dokter Corrie. Meanwhile, the school television channel reacted to the discussion by publishing the Dokter Corrie items online a day in advance in order to give parents and educators the opportunity to screen the show (Grutterink, 2013, Nov. 11). This is a clear example of a resolution (Drotner, 1992).[8][9]

Media panic cycles?

The debate about Dokter Corrie showed all the features of a classic media panic cycle (Drotner, 1992): a distinct instigating case (the first episodes of Dokter Corrie), a form of public intervention (the call to action followed by the online petition) and a clear fading out phase with a resolution (publishing the show online a day in advance). The debates about Spuiten en Slikken and Open en Bloot did not follow a classic media panic cycle. This can be explained by three aspects. The first is the target audience. As Drotner (1992) states, media panics focus mainly on children and young people. Dokter Corrie was indeed targeted at primary school children from 10-12 years old, while Open en Bloot and Spuiten en Slikken focused on young adults (older than 16). Secondly, episodes of Open en Bloot and Spuiten en Slikken were easier to avoid. Dokter Corrie was broadcasted in classrooms on school days (out of parents reach), while the other shows were broadcasted at 10 PM on public broadcasting channels. Finally, in the Dokter Corrie debate, the people responsible for the call-to-action on the catholic parenting website and the concerned parents who started an online petition can be considered moral entrepreneurs (Goode and Ben-Yehuda, 2009); they successfully attempted to draw public attention to, what they consider to be, immoral behaviour in Dokter Corrie, and took action to eliminate this moral threat. The debates about Open en Bloot and Spuiten en Slikken lacked moral entrepreneurs. However, all three debates share strong overarching moral attitudes which I discuss in the next section.

Framing television sex education

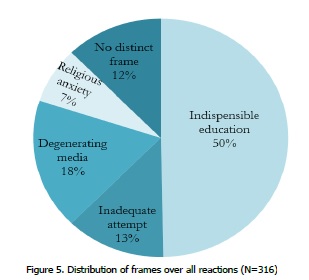

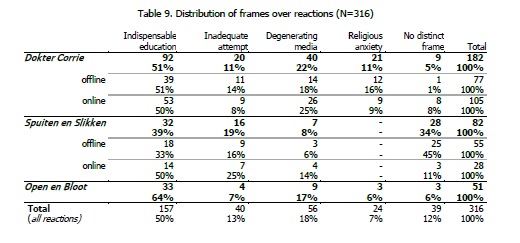

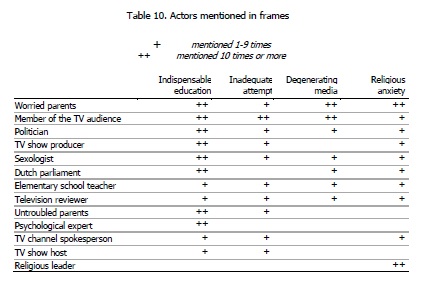

The inductive frame analysis resulted in four distinct frames. Figure 5 and Table 9 show how the Indispensable education frame, Inadequate attempt frame, Degenerating media frame and Religious anxiety frame are distributed over the corpus of 316 reactions. Table 10 displays which actors are mentioned within the different frames. These findings are substantiated in thick descriptions of the frames. [10][11]

Indispensable education frame

The most often recurring frame is characterised by an appreciative attitude towards the television shows, which is expressed in key words like taboo-breaking, necessary and educational. Table 9 shows that this frame is identified in 50% of all 316 reactions. Voices within this frame emphasise the necessity of television sex education and praise the manner in which it is carried out. Table 10 shows that this frame mentions a great variety of actors, which indicates that multiple opinions are addressed. For example, an article about Dokter Corrie addresses the concerns of the collective of worried parents and cites a worried mother. Moreover, the author mentions the opinions of a producer of the show and a television reviewer to counter the parents arguments (Van Houwelingen, 2013, Oct, 19). Another example is provided by an Open en Bloot audience member who refers to the opinions of psychological experts and other audience members to substantiate his main argument: sex is only natural (Hagen, 1974, Apr. 29).

The reactions about Open en Bloot with the Indispensable education frame often address the producers and psychological experts affiliated with the show; The producers of Open en Bloot want to stress the importance of talking about sex (Dagblad van het Noorden, 1974, Jan. 23). Audience members describe their appreciation of the shows approach to sex education; It is clear that the current state of sex education for adults and children is bad. (..) The producers address sex as civilised adults without diffidence (Van Vonderen, 1974, Jan, 24). Open en Bloots audience ratings form a recurring theme in the Indispensable education frame; Five million people watched the episode about sexuality (..) Afterwards, hundreds of viewers called the VARA [broadcasting channel] for information about the topics addressed in the show. The reactions were very positive. (De Tijd, 1974, Feb. 7).

The producers of Spuiten en Slikken are often cited in reactions to the show. They emphasise Spuiten en Slikkens experimental setting, educational basis and realistic approach to sex and drugs (De Jong and Langeslag, 2005, Sept. 22). Audience members often express their opinions on online forums and weblogs. For instance, Teknomist published a forum post wherein he expresses his appreciation for the producers intention to overcome taboos about sex and drugs (2005, Nov. 23). His view is supported by a blog post which acknowledges that Spuiten en Slikken addresses societal taboos in a provocative manner (Roggeveen, 2005, Dec. 12).

51% of the reactions to Dokter Corrie contains the positive Indispensable education frame. A recurring statement is I wish Dokter Corrie existed when I was young (Van Dam, 2013, Nov. 21). The main attitude of this frame is often voiced by producers and experts: psychologists, sexologists and doctors. For example, one doctor states in an online reaction that Dokter Corrie positively contributes to childrens development (Paauw, 2013, Nov. 13). Another influential supporter of Dokter Corrie proved to be the secretary of state responsible for media (Sander Dekker on behalf of VVD). In an interview, he stated that Dokter Corrie is informative and pretty funny (Katstra, 2013, Nov. 19). This statement was repeated in several newspapers and online sources.

Inadequate attempt frame

While voices within the Inadequate attempt frame are in favour of television sex education, they disapprove the manner in which it is carried out. Members of the audience are the most often mentioned actors in this frame, which is characterised by expressive personal sentiments. While young people call the television shows childish, juvenile, or goody-goody, experts and parents object to the light-hearted, simple way of informing and the producers desire for entertainment. Critics state that the intentions of the producers of television sex education are targeted at high audience ratings and amusement instead of education. The main argument of this frame is that sex education needs to be handled with more care and sincerity.

Only 7% of the Open en Bloot reactions contains the Inadequate attempt frame. The authors of these reactions are in favour of television sex education, but criticise the shows artificial openness (Y.G., 1974, Feb. 22), the childish sketches (Ris, 1974, Feb. 22), and the use of explicit language (Kuthe, 1974, Jan. 31). Another author calls Open en Bloot hypocritical and demands sincere openness (Kramer, 1974, Mar. 7). 19% of the Spuiten en Slikken reactions displays the Inadequate attempt frame. These reactions express a sense of disappointment following the grand announcement of the show. One television reviewer states that the excitement was not necessary (Bloemkolk, 2005, Oct. 11), while another reviewer criticises Spuiten en Slikkens shock-effects and entertainment style (Van de Beek, 2005, Nov. 5). Online reactions contain similar claims: Apparently it is necessary to shock on television to attract viewers (..) Raise the quality and be original! (Fleischbaum, 2005, Sept. 27). On a weblog, Spuiten en Slikken is accused of following trodden paths (Roggeveen, 2005, Oct. 11) and a forum member calls the show volatile and superficial (Golfer, 2005, Oct. 25).

In the Dokter Corrie debate, 11% of the reactions contains the Inadequate attempt frame. News articles mention expert opinions, such as a sexologist who disapproves of Dokter Corries mixed messages and confusing emotions (De Gooi- en Eemlander, 2013, Nov. 19). Various opinion articles criticise the presentation style and describe it as giggly and tacky. One weblog author states: I feel shame and pity for the pre-teen audience (Nagel, 2013, Nov. 20).

Degenerating media frame

Voices within the Degenerating media frame speak out against television sex education. According to them, television is unfit to carry out sex education. Media are described as a folk devil that plays a harmful role in the sexual socialisation of children and young people. Sex education is the responsibility of parents and suitable authorities. This frame is characterised by key terms such as moral decay, tasteless and false pretences. This frame contains personal expressions of fear for the consequences of television sex education. The most often mentioned actors are worried parents and members of the audience. This frame lacks interest in the shows producers, spokespersons or hosts, or in untroubled parents and experts. In the Open en Bloot debate, this frame occurs in letters-to-the-editor in which viewers describe the show as uncivilised filthiness while expressing a fear of moral decay. Fear for the demoralising consequences is frequently expressed. One audience member claims that this educational content is venom (Donners, 1974, Mar. 3), while another author complains about the filth they use to make children unhappy. He or she also asks Do they really have to destroy youth? (Janssen, 1974, Feb. 23). Not only do the Open en Bloot reactions articulate concerns, they also often express a degrading tone. For example, one reviewer describes that he cannot escape the impression that the educators enjoy to play, under the guise of salvation of mankind, with dirty words and nakedness (Van Herwen, 1974, Feb 22) and one letter-to-the-editor mentions: For me it is incomprehensible how a person with brains and a normal emotional life, civilised with normal moral values, can appreciate Open en Bloot. (Hoogstraten, 1974, Jan. 30). There are only seven Spuiten en Slikken reactions (8%) displaying the Degenerating media frame. These reactions address the show as a source of moral decay. For example, one letter-to-the-editor blames broadcasting organisation BNN for exceeding all bounds of decency (Zilvers, 2005, Nov. 22).

The Degenerating media frame is the second most common frame in the debate about Dokter Corrie and occurs in 18% of all reactions about the show. The initiator of this frame is the collective of worried parents which started an online petition to stop the show. The worried parents are supported by a politician and a sexologist who raised parliamentary questions and published an opinionated article in four newspapers. In this article, they state that sex education requires carefulness and safety (Borger & Voordewind, 2013, Nov. 16). This protective attitude is connected to the responsibility of parents. Newspapers offered a stage to supporters of this frame, but remained neutral about their own standpoints.

Religious anxiety frame

The Religious anxiety frame displays religious concerns. Voices within this frame state that television embodies a dangerous form of indoctrination that imposes bad sexual norms on children. The basis of this frame is religious and covers both Christian and Islamic concerns. Sex education is the responsibility of parents and the church. Interference of government institutions and schools is undesirable and wrong. The frame shows a distinct moral basis expressed in key words such as indoctrination, moral standards, manipulation and inappropriate. The most often mentioned actors are worried parents, this is the only frame that mentions religious leaders. An example is the blog of a bishop, who links his own opinion about sex education to texts of pope Fransciscus (Hendriks, 2013, Oct. 11).

The Religious anxiety frame occurs in three reactions about Open en Bloot. These letters-to-the-editor of Christian audience members were published in newspapers with different ideological backgrounds (Christian, progressive and neutral). One reaction criticises the show by asking Why do they always have to use blasphemous language? (Kramer, 1974, Jul. 03). Another author complains that the show lumps together Christian and non-Christian visions about sex (Wenckman, 1974, Feb. 4). De Haas is the most outspoken in his accusation of the glorification of impurity, as he concludes with: ignoring Gods commandments will lead to the decay of cultural, religious, political and economic life (De Haas, 1974, Feb. 28). While the Spuiten en Slikken debate lacks a religious dimension, the Religious Anxiety frame is visible in 11% of the reactions in the Dokter Corrie debate. The occurrence of this frame is marginal (7% of all 316 reactions). Nevertheless, this frame proved to be powerful because it is expressed by the moral entrepreneurs who instigated the Dokter Corrie debate. Their fear of moral decay is mainly voiced online. For example, the author of a Christian weblog claims that Dutch culture lost its sense of sacredness (Habakuk.nu, Nov. 11, 2013). Whereas the main part of these reactions shows a Christian background, there are also Islamic contributions. On an Islamic forum, a forum member states that Dokter Corrie offers porn for children instead of sex education. It is our duty as parents to provide our children with the proper Islamic style of thinking and living (Vesper, 2013, Nov. 20).

Most newspapers handled this frame in a neutral manner; they mention the opinions of the moral entrepreneurs but balance them with counter-opinions. An exception is a Christian newspaper that published an article about the discussion wherein the collective of worried parents is supported in a latent manner. The words justly and logically are repeatedly used in the description of the parents opinions and actions (Reformatorisch Dagblad, 2013, Nov. 20). This newspaper shows a distinct bias.

Conclusion

This study examined the moral dimensions of public debates about the television sex education shows Dokter Corrie, Spuiten en Slikken and Open en Bloot. This analysis resulted in four content oriented substantive/advocacy frames (De Vreese, 2012; Entman, 2004). These four morally charged frames display recurring fears, critiques and moral attitudes. The Indispensable education frame, Inadequate attempt frame, Degenerating media frame and Religious anxiety frame focus on the problematic conditions of television sex education. All four frames convey moral judgments expressed through metaphors and symbolism, such as filth, tasteless, the glorification of impurity, and a sense of sacredness. The moral dimensions in these debates revolve around the sexual socialisation of children. The societal values at stake (Cohen, 1971) concern (the responsibility for) the sexual education of children and young people. While all frames argue that sex education needs to be handled with care and sincerity, the Indispensable education frame and the Inadequate attempt frame regard television as the right channel for this goal. In contrast, voices within the Degenerating media frame and the Religious anxiety frame claim that television shows threaten the social sexualisation of children. The collective of worried parents targets Dokter Corrie, a fictional character, as the identifiable enemy responsible for this threat (Critcher, 2006). For other actors, the folk devil (Cohen, 1971) seems to be depersonalised (David et al., 2011). They target their fear towards the television shows in general instead of one distinct actor, this reflects Ungars (2001) notion of a reflexive relationship between interest groups.

The debates include a multiplicity of voices (McRobbie and Thornton, 1995); members of the audience, politicians, producers of the show and psychological experts are among the often mentioned actors. The collective of worried parents that strategically instigated the Dokter Corrie debate proved to be influential. They function as moral entrepreneurs (Goode and Ben-Yehuda, 2009) who deliberately envisioned and realised a media panic. This idea is substantiated by McRobbies and Thorntons (1995) claim that voices in panic debates have become aware of the use of effective media strategies. The moral entrepreneurs played an important role in the media panic about Dokter Corrie, which was the only show that provoked a classic media panic cycle with a distinct instigating case, a form of public intervention and a clear fading out phase with a seeming resolution (Drotner, 1992). Its young target audience, the fact that the show was broadcasted in classrooms and the moral entrepreneurs were crucial in this process. The analysis of the moral dimensions of the three television sex education debates led to a contextual perspective wherein the Dokter Corrie debate confirmed the basic assumptions of media panic research. In addition, the results shows how moral attitudes about television sex education recur over time; moral aspects of the Dokter Corrie debate were also visible in the debates about Spuiten en Slikken and Open en Bloot that took place in 2005 and 1974. This study complements media panic research because it points to the crucial role of moral entrepreneurs, a concept derived from moral panic theory. This indicates that it is useful to take moral entrepreneurs into account in media panic research.

Whereas my study provides a detailed account of moral attitudes about television sex education, there are a three limitations that need to be addressed. First, the analysis is limited to text while television and radio could also provide relevant reactions to the shows. Second, while the selection of the three television sex education shows indicates that public debates display recurring frames about television sex education, the scope remains limited. To ensure a full overview of moral dimensions of Dutch television sex education debates, the analysis of reactions to other television sex education shows could substantiate the results. Third, the drugs-section of Spuiten en Slikken complicated the analysis of the moral dimensions of the show. This complexity needs to be accounted for with regard to the findings about the Spuiten en Slikken debate.

Nevertheless, the research design leaves room for future research to adopt a similar approach in order to determine how the four resulting frames resonate in an even broader context. The findings ask for an exploration of the sensitivity of topics like children and sex education over the years and of the moral responsibility with regard to these topics. Finally, future analysis of reactions to television sex education in other countries[12] is needed to shed light on the moral dimensions in a crossnational perspective.

References

Biltereyst, D. (2004). Media audiences and the game of controversy. Journal of Media Practice, 5 (1), 117-137. Retrieved from http://academic.csuohio.edu/kneuendorf/frames/phx/creativegeography/biltereyst_04.pdf [ Links ]

Boynton, P. (2006). Enough with tips and advice and thangs: The experience of a critically reflexive, evidence-based Agony Aunt. Feminist Media Studies, 6 (41), 541-546. [ Links ]

Boynton, P. (2007). Advice for sex advisors: a guide for agony aunts, relationship therapists and sex educators who want to work with the media. Sex Education: Sexuality, Society and Learning, 7 (3), 309-326. Retrieved from http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/14681810701448119. [ Links ]

Buijs, L., Geesink, I. and Holla, S. (2013). De seksparadox. Nederland na de seksuele revolutie. Sociologie, 9 (3), 245-257. Retrieved from http://dx.doi.org/10.5553/TS/157433142013009003001. [ Links ]

Cohen, S. (2002) [1971]. Folk Devils and moral panics; the creation of the Mods and Rockers (3rd edition). London: Routledge. [ Links ]

Creswell, J.W. and Miller, D.L. (2000). Determining Validity in Qualitative Inquiry. Theory Into Practice, 39:3, 124-130. Retrieved from http://dx.doi.org/10.1207/s15430421tip3903_2. [ Links ]

Critcher, C. (2006). Introduction: More questions than answers. In: Critical Readings: Moral Panics and The Media (pp. 1-23). Berkshire: Open University Press. [ Links ]

David, M., Rohloff, A., Petley, J. & Hughes, J. (2011). The idea of moral panic – ten dimensions of dispute. Crime, Media, Culture, 7 3), 215-228. Retrieved from http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/1741659011417601. [ Links ]

Diamond, M. (1979). Sex Education on Television: an early history of some firsts. Journal of Sex Education and Therapy, 11 (2), 30-34. [ Links ]

De Vreese, C.H. (2012). New Avenues for Framing Research. American Behavioral Scientist, 56(3), 365-375. [ Links ]

Drotner, K. (1992). Modernity and Media Panics, pp. 42-62 in M. Skovmand and K.Chr. Schroder (Ed.) Media Cultures. Reappraising Transnational Media. London: Routledge. [ Links ]

Entman, R. M. (2004). Projection of power. Framing news, public opinion and U.S. foreign policy. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [ Links ]

Gamson, W. A. & Modigliani, A. (1989). Media discourse and public opinion on nuclear power: A constructionist approach. American Journal of Sociology, 95 (1): 1–37. [ Links ]

Geelen, J.P. (2003, Feb. 22). Van geneuzel naar geneuk; BNN begint met zevendelige cursus seksuele voorlichting op tv. De Volkskrant. Retrieved from http://academic.lexisnexis.nl. [ Links ]

Geertz, C. (1973). Thick description: Toward an interpretive theory of culture. In: The interpretation of cultures. Selected essays (pp. 1-30). New-York: Basic Books. [ Links ]

Gilbert, N. (2008). Researching social life. London: Sage. [ Links ] Gitlin, T. (2003) [1980]. The Whole World is Watching: Mass Media in the Making & Unmaking of the New Left. Berkeley: University of California Press. [ Links ]

Goode, E. & Ben-Yehuda, N. (2009). Moral Panics: The Social Construction of Deviance (2nd edition). Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell. [ Links ]

Gunter, B. (2009). Media Sex: What are the Issues? Mahwah, New Jersey: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. [ Links ]

Hall, S., Critcher, C., Jefferson, T., Clarke, J.,& Roberts, B. (1978). Policing the Crisis: Mugging, the State, and Law and Order. Critical Social Studies. Houndmills: Palgrave Macmillan. [ Links ]

Hekma, G. & Giami, A. (2014). Sexual revolutions. Houndmills: Palgrave Macmillan. [ Links ]

McRobbie, A. (1994). The Moral Panic in the Age of the Postmodern Mass Media. In Postmodernism and Popular Culture (pp. 193-212). London: Routledge. [ Links ]

McRobbie, A. & Thornton, S.L. (1995). Rethinking moral panic for multi-mediated social worlds. British Journal of Sociology, 46 (4), 559–74. Retrieved from http://theholeinfaraswall-2.nethouse.ru/static/doc/0000/0000/0232/232513.n92swqqmxd.pdf [ Links ]

Ofcom (1998, April 1). Complaint reports. Ofcom Independent regulator and competition authority for the UK communication industries. Retrieved from http://www.ofcom.org.uk/static/archive/itc/itc_publications/complaints_reports/programme_complaints/show_complaint.asp-prog_complaint_id=69.html. [ Links ]

Overste, A.M. (1974a). Sexuele voorlichting op de buis: Open en Bloot. Rapport nr. 107. Hilversum: NOS Afdeling Kijk- en Luisteronderzoek. Retrieved from https://easy.dans.knaw.nl/ui/datasets/id/easy-dataset:33302. [ Links ]

Overste, A.M. (1974b). Sexuele voorlichting op de buis: Open en Bloot. Rapport nr. 108. Hilversum: NOS Afdeling Kijk- en Luisteronderzoek. Retrieved from https://easy.dans.knaw.nl/ui/datasets/id/easy-dataset:33302. [ Links ]

Overste, A.M. (1974c). Sexuele voorlichting op de buis: Open en Bloot. Rapport nr. 110. Hilversum: NOS Afdeling Kijk- en Luisteronderzoek. Retrieved from https://easy.dans.knaw.nl/ui/datasets/id/easy-dataset:33302. [ Links ]

Overste, A.M. (1974d). Sexuele voorlichting op de buis: Open en Bloot. Rapport nr. 111. Hilversum: NOS Afdeling Kijk- en Luisteronderzoek. Retrieved from https://easy.dans.knaw.nl/ui/datasets/id/easy-dataset:33302. [ Links ]

Ponteretto, J.G. (2006). Brief Note on the Origins, Evolution, and Meaning of the Qualitative Research Concept Thick Description. The Qualitative Report, 11 (3), 538-549. Retrieved from http://www.nova.edu/ssss/QR/QR11-3/ponterotto.pdf. [ Links ]

Prior, S. (2013). Scary Seks: The Moral Discourse of Glee. In: B. Fahs, M.L. Dudy, S. Stage (Eds.), The Moral Panics of Sexuality (pp.92-116). Houndmills: Palgrave MacMillan. [ Links ]

Rijksoverheid (2012). Vakken en kerndoelen basisonderwijs. Rijksoverheid.nl. Retrieved from http://www.rijksoverheid.nl/onderwerpen/basisonderwijs/vakken-en-kerndoelen. [ Links ]

Schnabel,(1990). Het verlies van de seksuele onschuld. In: G. Hekma, B van Stolk, B. van Heerikhuizen and B. Kruithof (Eds.), Het verlies van de onschuld. Seksualiteit in Nederland (pp. 11-50). Groningen: Wolters-Noordhoff

Shenton, A. K. (2004). Strategies for ensuring trustworthiness in qualitative research projects. Education for information, 22, 63-75. [ Links ]

Strauss, A. & Corbin, J. (1990) Qualitative Data Analysis. Beverly Hills: Sage. [ Links ]

Ungar, S. (2001). Moral panic versus the risk society: the implications of the changing sites of social anxiety. British Journal of Sociology, 52 (2), 271-291. Retrieved from http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/00071310120044980. [ Links ]

Van Gorp, B. (2007). The Constructionist Approach to Framing: Bringing Culture Back In. Journal of Communication, 57 (1), 60-78, Retrieved from http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1460-2466.2006.00329.x. [ Links ]

Van Lieshout, J. & van Schaik, C. Th. (1974). Open & Bloot. Amsterdam: Wetenschappelijke Uitgeverij. [ Links ]

Vara (2013). Gebeurtenis Open en Bloot op televisie. Retrieved from http://biografie.vara.nl/#/gebeurtenis/194/open-en-bloot-op-televisie?item=317&type=video&title=open-en-bloot-leader&totop=1. [ Links ]

Vliegenthart, R. & van Zoonen, L. (2011). Power to the frame: Bringing sociology back to frame analysis. European Journal of Communication, 26 (2), 101-115. Retrieved from http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0267323111404838. [ Links ]

Reactions to Open en Bloot, Spuiten en Slikken en Dokter Corrie

Algemeen Dagblad. (2005, Oct. 19). Seks- en drugstest verkeerd Voorlichtingsprogramma BNN gaat minister Donner te ver. Retrieved from http://academic.lexisnexis.nl. [ Links ]

Beestmensen. Een bloemlezing uit de reacties op Open en Bloot (1974, Jun. 8). Vrij Nederland, 35, 7. [ Links ]

Bloemkolk, J. (2005, Oct. 11). Eerst even de Het Parool. Retrieved from http://academic.lexisnexis.nl. [ Links ]

BNN (2014). Spuiten en Slikken. Retrieved from http://spuitenenslikken.bnn.nl. [ Links ]

Bol, S. and Van Soest, A. (2013, Oct. 3). Voorlichting van dokter Corrie slaan wij altijd over. Nederlands Dagblad. Retrieved from http://academic.lexisnexis.nl [ Links ]

Borger, A. and Voordewind, J. (2013, Nov. 16). Prop dokter Corrie niet in een paar minuten schooltv Brabants Dagblad. Retrieved from http://academic.lexisnexis.nl. [ Links ]

De Haas, Th. (1974, Feb. 28). Open en Bloot (2). Limburgsch Dagblad. Retrieved from http://resolver.kb.nl/resolve?urn=ddd:010560522:mpeg21:a0106. [ Links ]

De Jong, G. (2013, Nov. 21). Blonde seksdokter. Habakuk.nu. Retrieved from http://www.habakuk.nu/opinies/item/3912-blonde-seksdokter. [ Links ]

De Jong, A. and Langeslag, M. (2005, Sept. 22). Seks, drugs en BNN Omroep zoekt in Spuiten&Slikken opnieuw de grenzen op. Algemeen Dagblad. Retrieved from http://academic.lexisnexis.nl. [ Links ]

Dokter Corrie. (2013, Nov. 20). Reformatorisch Dagblad. Retrieved from http://academic.lexisnexis.nl. [ Links ] Dokter Corrie zendt te veel dubbele boodschappen uit.(2013, Nov. 19). De Gooi- en Eemlander.Retrieved from http://academic.lexisnexis.nl. [ Links ]

Donners, M. (1974, Mar. 3). Open en Bloot (3). Limburgs Dagblad. Retrieved from http://resolver.kb.nl/resolve?urn=ddd:010560911:mpeg21:a0093. [ Links ]

Fleischbaum (2005, Sept. 27). CDA slikt het niet. Geenstijl.nl. Retrieved from http://www.geenstijl.nl/mt/archieven/2005/09/cda_slikt_het_niet.html. [ Links ]

Golfer (2005, Oct. 25). Ouwe Jongen. Retrieved from http://forum.fok.nl. [ Links ]

Grutterink, B. (2013, Nov. 11). Kabinet zit niet zo met seksles dr. Corrie. Algemeen Nederlands Persbureau. Retrieved from http://academic.lexisnexis.nl. [ Links ]

Hagen. (1974, Apr. 29). Gezond bloot. Leeuwarder Courant. Retrieved from http://resolver.kb.nl/resolve?urn=ddd:010619627:mpeg21:a0139. [ Links ]

Heerlien, L. (2013, Nov. 19). Van seks maakt ze een slechte grap. De Gooi- en Eemlander. Retrieved from http://academic.lexisnexis.nl. [ Links ]

Heil, (1974, May 16). Schutting. Het Vrije Volk. Retrieved from http://resolver.kb.nl/resolve?urn=ddd:010958462:mpeg21:a0234. [ Links ]

Hendriks, J. (2013). Veel commotie rond Dokter Corrie. Retrieved from http://www.arsacal.nl/?p=contentitem&id=445. [ Links ]

Hoge kijkdichtheid voor Open en Bloot. (1974, Feb. 7). De Tijd: dagblad voor Nederland. Retrieved from http://resolver.kb.nl/resolve?urn=ddd:011236407:mpeg21:a0037. [ Links ]

Hoogstraten, J.C.W. (1974, Jan. 30). Open en Bloot. Het Vrije Volk. Retrieved from http://resolver.kb.nl/resolve?urn=ddd:010958341:mpeg21:a0120. [ Links ]

Janssen, I.W. (1974, Feb. 23). Open en bloot. Limburgsch dagblad. Retrieved from http://resolver.kb.nl/resolve?urn=ddd:010560518:mpeg21:a0417 [ Links ]

Kabinet zit niet zo met seksles dr. Corrie. (2013, Nov. 11). Nujij.nl. Retrieved from http://www.nujij.nl/media/kabinet-zit-niet-zo-met-seksles-dr-corrie.25836672.lynkx. [ Links ]

Katstra, J. (2013, November 18). Boze ouders protesteren tegen Dokter Corrie. Algemeen Nederlands Persbureau. Retrieved from http://academic.lexisnexis.nl. [ Links ]

Katstra, J. (2013, November 19). Dekker vindt Dokter Corrie best grappig. Algemeen Nederlands Persbureau. Retrieved from http://academic.lexisnexis.nl. [ Links ]

Koolhaas, M. (2013, November 20). Kritiek op seksuele voorlichting door dokter Corrie. Het begon in 1974 met Open en Bloot. Geschiedenis24. Retrieved from http://www.geschiedenis24.nl/nieuws/2013/november/Seksuele-voorlichting-dokter-Corrie-Open-en-Bloot-Joop-van-Tijn-neuken.html. [ Links ]

Kramer, J. (1974, Mar. 3). Open en Bloot. Leeuwarder Courant. Retrieved from http://resolver.kb.nl/resolve?urn=ddd:010619584:mpeg21:a0223. [ Links ]

Kuthe, M. Ch. (1974, Jan 31). Open en bloot. De Telegraaf. Retrieved from http://resolver.kb.nl/resolve?urn=ddd:011239196:mpeg21:a0244. [ Links ]

Meijer, H. (2013, Oct. 16). Schooltv komt bezorgde ouders tegemoet. Nederlands Dagblad. Retrieved from http://academic.lexisnexis.nl. [ Links ]

Nagel, J. (2013, Nov. 20). Sorry dokter Corrie, maar noem je dat seksuele voorlichting? Ad Rem.Retrieved from http://www.adremonline.nl/columns/sorry-dokter-corrie-maar-noem-je-dat-seksuele-voorlichting/. [ Links ] Niets mis met seksles dokter Corrie (2013, Nov. 12) De Telegraaf. Retrieved from http://academic.lexisnexis.nl. [ Links ]

Nieuwslezers NOS woedend na seksgrapjes. (2005, Nov. 23). De Telegraaf. Retrieved from http://academic.lexisnexis.nl. [ Links ]

Niet shockeren, waarschuwen! (2005, Oct. 16). De Telegraaf. Retrieved from http://academic.lexisnexis.nl. [ Links ]

Paauw, S. (2013, Nov. 13). Dr. Corrie kan doorgaan met seksles. Medisch Contact. Retrieved from http://medischcontact.artsennet.nl/actueel/nieuws/nieuwsbericht/139063/dr.-corrie-kan-doorgaan-met-seksles.htm. [ Links ]

Ris, E. (1974, Feb. 22). De eerste keer. Het Vrije Volk. Retrieved from http://resolver.kb.nl/resolve?urn=ddd:010958361:mpeg21:a0371. [ Links ]

Roggeveen, H. (2005, Dec. 12). Laatste Spuiten & Slikken: tijd om de balans op te maken. Zappen.blog.nl. Retrieved from: http://zappen.blog.nl/varabnn/2005/12/12/laatste_spuiten_amp_slikken_tijd_om_de_balans_op_te_maken. [ Links ]

Roggeveen, H. (2005, Oct. 11). Spuiten & Slikken: platgereden paden en puberaal gegichel. Zappen.blog.nl. Retrieved from http://zappen.blog.nl/varabnn/2005/10/11/spuiten__slikken_platgereden_paden_en_puberaal_gegiechel. [ Links ] Schooltv zet ouders buiten spel bij seksuele opvoeding (2013, Sept. 21). Katholiekgezin.nl. Retrieved from http://www.katholiekgezin.nl/index.php?option=com_content&task=view&id=2590&Itemid=1. [ Links ] Seks- en drugstest verkeerd Voorlichtingsprogramma BNN gaat minister Donner te ver (2005, Oct. 19). Algemeen Dagblad. Retrieved from http://academic.lexisnexis.nl. [ Links ] Sex onderwerp van nieuwe televisieserie Open en bloot. (1974, Jan. 23). Nieuwsblad van het Noorden. Retrieved from http://resolver.kb.nl/resolve?urn=ddd:011016841:mpeg21:a0194. [ Links ]

Teknomist (2005, Nov. 23). No subject. Retrieved from http://forum.fok.nl. [ Links ]

Van Dam. (2013, Nov. 21). Dokter Corrie. PZC.nl. Retrieved from http://www.pzc.nl/extra/columns/columns-willem-van-dam/dokter-corrie-1.4107568.

Van de Beek. (2013, Nov. 5) Gezien: Coole shit van BNN. Elsevier. Retrieved from http://academic.lexisnexis.nl. [ Links ]

Van Herwen (1974, Feb. 22). Wat bracht de tv? De Telegraaf. Retrieved from http://resolver.kb.nl/resolve?urn=ddd:011239215:mpeg21:a0246.

Van Houwelingen (2013, Oct. 19). Ouders klagen over seksles van Dokter Corrie op School TV. Algemeen Dagblad. Retrieved from http://academic.lexisnexis.nl. [ Links ]

Van Paridon, J. (2013, Oct. 2). Dr Corrie maakt gesprek over seks ontspannend. Nederlands Dagblad.Retrieved from http://academic.lexisnexis.nl. [ Links ]

Van Vonderen, J.P. (1974). Open en bloot neemt geen blad voor de mond. De Telegraaf. Retrieved from http://resolver.kb.nl/resolve?urn=ddd:011239190:mpeg21:a0149. [ Links ]

Vesper. (2013, Nov. 20). Stop Dokter Corrie. Marokko Community. Retrieved from http://forums.marokko.nl/archive/index.php/t-4832942-stop-dokter-corrie-p-9.html. [ Links ]

Wenckman, W.J. (1974, Feb. 4). TV-recensie. De Tijd: dagblad voor Nederland. Retrieved from http://resolver.kb.nl/resolve?urn=ddd:011236404:mpeg21:a0072. [ Links ]

Y.G. (1974, Feb. 22). Britse Mijnwerkers. De Waarheid. Retrieved from http://resolver.kb.nl/resolve?urn=ddd:010375173:mpeg21:a0073. [ Links ]

Zilvers, R. (2005, Nov. 22). BNN. De Telegraaf. Retrieved from http://academic.lexisnexis.nl. [ Links ]

Television shows about sex and sex education in chronological order

AVRO (Producer) (1971). Sex in wording. The Netherlands: AVRO. [ Links ]

PBS (Producer) (1973). Human Sexuality Hawaii: PBS. [ Links ]

Steinebach, M. (Producer) (1974). Open en Bloot. The Netherlands: VARA. [ Links ]

Stephens Kerr (Producer). (1985). Sex Talk. United Kingdom: Channel4. [ Links ]

Veronica (Producer) (1987). De Pin Up Club. The Netherlands: Veronica. [ Links ]

IKON (Producer) (1987). Geloof, hoop en liefde show. The Netherlands: IKON. [ Links ]

Clucas, T. (Producer) (1992). Sex. Australia: Nine Network Australia. [ Links ]

AVRO (Producer) (1993). Sex met Angela. The Netherlands: AVRO. [ Links ]

SBS6 (Producer) (1995). Over seks gesproken. The Netherlands: SBS6. [ Links ]

Holland Media House (Producer) (1997). Sex voor de Buch. The Netherlands: Veronica. [ Links ]

EO (Producer) (1998). Save Sex. The Netherlands: EO. [ Links ]

IKON (Producer) (1998). Jonge heren. The Netherlands: IKON. [ Links ]

LWT (Producer) (1998). Love Bites. United Kingdom: ITW Network. [ Links ]

BNN (Producer) (2003). Neuken doe je zo. The Netherlands: BNN. [ Links ]

BNN (Producer) (2005-2014). Spuiten en Slikken. The Netherlands: BNN. [ Links ]

Weller/Grossman Productions (Producer) (2005). Strictly Sex with Dr. Drew. United States: Discovery Health. [ Links ]

Murphy, R., Falchuk, B., Brennan, I., & De Loreto, D. (Producers) (2009). Glee. Beverly Hills, CA: 20th Century Fox Television. [ Links ]

Pride Toronto (Producer) (2011). Sex Matters. Canada: CP24. [ Links ]

Genemans, E. (Producer) (2012). Passie in de Polder. The Netherlands: RTL 5. [ Links ]

NTR (Producer) (2013). Dokter Corrie. The Netherlands: NTR. [ Links ]

Notes

[1] The news coverage is measured over a timespan of six months (two months prior to first broadcast and four months afterwards), source 1971-1978: www.delpher.nl, source 1978-2013: www.academic.lexisnexis.nl.

[2] Dutch television also offered several controversial entertainment shows about sex. Examples are De Pin Up Club (Veronica, 1987), Sex voor de Buch (Veronica, 1997) and Passie in de Polder (RTL 5, 2012). Because this study focuses on educational television, these entertainment shows are excluded from analysis.

[3] Examples of sources in the data sample: Offline: quality newspapers such as NRC Handelsblad, popular newspapers such as De Telegraaf, regional newspapers such as De Gelderlander, free newspapers such as Metro, newsmagazines such as Elsevier and wire service reports from Algemeen Nederlands Persbureau (ANP). Online: Forum threads on forums such as Fok Forum, online petitions such as www.stopdoktorcorrie.nl, columns on opinionated websites such as Joop.nl, blogs such as zappen.blog.nl and GeenStijl, and online-only news such as Broadcast Magazine.

[4] This table describes the persons that give their own opinion, that are cited or whose opinions are mentioned. The percentages indicate which part of the total amount of reactions to Open en Bloot mentions this specific actors opinion.

[5] This table shows the main topics of all the reactions to Open en Bloot (topics that were not visible in the reactions are excluded from the table, see page 9 for the complete list of topics).

[6] This table describes the persons that give their own opinion, that are cited or whose opinions are mentioned. The percentages indicate which part of the total amount of reactions to Spuiten en Slikken mentions this specific actors opinion.

[7] This table shows the main topics of all the reactions to Spuiten en Slikken (topics that were not visible in the reactions are excluded from the table, see page 9 for the complete list of topics)

[8] This table describes the persons that give their own opinion, that are cited or whose opinions are mentioned. The percentages indicate which part of the total amount of reactions to Dokter Corrie mentions this specific actors opinion.

[9] This table shows the main topics of all the reactions to Dokter Corrie (topics that were not visible in the reactions are excluded from the table, see page 9 for the complete list of topics).

[10] For 39 reactions it was not possible to determine a frame because these texts proved to be too ambiguous or short. This relatively large number can be explained by 28 articles about Spuiten en Slikken that focused on drugs instead of sex education. These articles did not contain distinct moral ideas about television sex education.

[11] I chose to visualise the mentioning of actor in the various frames instead of showing numbers. This because the table enables an overview of the important actors per frame whereby specific number are not necessarily relevant. In addition, the uneven distribution of the frames over the complete reactions leads to distorted numbers. E.g. members of the TV audience are mentioned 28 times in the Indispensable education-frame and 10 times in the Inadequate attempt frame. This can be explained by the fact that the former is more often present in the reactions than the latter, but it can lead to false assumptions about the importance of actors or their weight in specific frames.

[12] Other countries also broadcasted various television sex education shows. A couple of examples: Hawaii: Human Sexuality (PBS, 1973); United Kingdom: Sex Talk (Channel4, 1985) and Love Bites (LWT, 1998); Australia: Sex (Nine Network, 1992); United States: Strictly Sex with Dr. Drew (Weller/ Grossman Productions, 2005) and Canada: Sex Matters (Pride Toronto, 2011).