Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Acessos

Acessos

Links relacionados

-

Similares em

SciELO

Similares em

SciELO

Compartilhar

Observatorio (OBS*)

versão On-line ISSN 1646-5954

OBS* vol.10 no.2 Lisboa abr. 2016

ARTIGO ORIGINAL

Flows of communication and influentials in Twitter: A comparative approach between Portugal and Spain during 2014 European Elections

Inês Amaral*, Rocío Zamora**, María del Mar Grandío***, José Manuel Noguera****

*Centro de Estudos de Comunicação e Sociedade da Universidade do Minho / Universidade Autónoma de Lisboa / Instituto Superior Miguel Torga (inesamaral@gmail.com)

**Faculty member, Departament of Information and Communication, University of Murcia, España.

***Faculty member, Departament of Information and Documentation, University of Murcia, España.

****Profesor de Tecnología en la Facultad de Comunicación, Universidad Católica de Murcia, España.

ABSTRACT

The research about the concept of influence on Twitter is still underdeveloped. This work is a theoretical and empirical approach on how politicians are engaging with citizens and/or journalists, and how these social conversations are framed under specific topics and users. The idea of new influentials on political communication in the new media ecosystem, as some studies found (Dang-Xuan et al, 2013), can offer empirical pursuit of the suggested two-step flow model as applied to the agenda-setting process (Weimann et al., 2007) in the case of the microblogging for campaigning online.

Following the recent research about how politicians try to reach their potential audience (Vaccari and Valeriani, 2013; 2013a), this paper analyses the social conversations on Twitter driven by politicians, the main topics in these political conversations and the kind of flows of communication (direct or indirect) between politicians, journalists and citizens. This research explores the differences and similarities about influence on Twitter during European elections in two countries with similar political and economic contexts: Portugal and Spain.

Keywords online influence; political communication; social interaction; European elections

Introduction

The decentralized network structure of the Internet has changed the diffusion of information and its effects of communication. While one-sided (from the media to the audience) and direct effects dominate in the context of mass media, indirect effects and multistep flow of communication in all directions are more common on the Internet. In this sense, the process of influence is assumed to be more complex that a single group of opinion leaders listening to the mass media, and then feeding their opinions to a group of passive followers. Instead, in the context of social media, people who influence others are themselves influenced by others in the same topic area, resulting in an exchange. Opinion leaders are, thereby, both disseminators and recipients of influence. With this in mind, a more accurate portrayal of the communication flow would be a multi-step process, rather than simply two-step process (Weimann, 1982). In fact, Twitter literature supports the thesis that gatekeepers have become increasingly atomized and fragmented, as users receive and pass on information without the mediation of media outlets, and with new gatekeepers (Jürgens et al., 2011). In fact, only a small portion of tweets received by ordinary users comes from media outlets.

If gatekeeping was previously identified with mass media channels, it is now shared among a number of unidentified elites who ensure that information flows have not become egalitarian. Clearly, ordinary users on Twitter are receiving their information from many thousands of distinct sources, most of which are not traditional media organizations. Thus, while attention that was formerly restricted to mass media channels is now shared amongst other elites, information flows have not become egalitarian by any means. Elites can be defined as the new influentials – users who may take over as new gatekeepers with the power to influence and direct access to the media and the audience. Some are ordinary users, but most are corporate and/or specialized. Social networks are important social thermometers, either for national or local audiences. Its appropriation by the various actors involved in the network and induces even if involuntarily to the receiver, the transmission of content/opinions mediated. The distortion of reality is common. Disseminate mass content with misleading or false messages are regular practices on the Internet. These elites have access to many users via a profitable use of digital tools. Among their audience are the media.

In that sense, Twitter has revealed a new class of individuals who often become more prominent than traditional public figures, such as entertainers or official gatekeepers, whose function is neither of broadcasting nor narrowcasting, but rather a form of directed-casting (Toledo et al, 2013). But who are these new influentials on Twitter and how can they be identified? Can politicians be new influential by the appropriation of the tools of the new media ecosystem? This study is analysing influence in terms of creation of flows of conversation and tacit support to some messages with native actions of Twitter such as retweets (RT).

New actors, New influentials?

The theoretical framework of this paper is based on the assumption that there are new influentials on political communication in the new media ecosystem (Dang-Xuang et al, 2013). Our aim is to analyze direct influence of Portuguese and Spanish candidates on Twitter in order to examine their flows of communication, activity, agenda issues, social interactions (direct and indirect conversation), influence in Twitter sphere, engagement with audience and social authority. Does Spanish and Portuguese politicians running for European Elections in 2014 became real opinion leaders on Twitter during the campaign by assuming the characteristics of the new influentials?

Decades of social science research have demonstrated that there is a group of people in any community to whom others look to help them to form opinions on several issues and matters (Weimann, 1994). Whether they are called opinion leaders or influentials, these people literally lead the formation of attitudes, public knowledge and opinions. Such opinion leaders also referred to as the influentials that often provide information and advice to followers. Therefore, they are more likely to influence purchasing behaviour through word-of-mouth communication.

Thinking about influence in public communication means the ability of a media outlet or a single communicator as a node in the communication network to steer the diffusion of innovations, issues, information, and words (memes) or to achieve certain effects within the audience (Dang-Xuan et. al, 2013). According to the traditional understanding, influence means the ability or qualities of someone to spread ideas to others (Rogers, 1962) and change their opinions (Katz and Lazarsfeld 1955).

The Twitter ecosystem is well suited to studying the role of influencers (Bakshy et al., 2011). In general, influencers are thought to be special individuals who disproportionately impact the likelihood that information will spread broadly (Weimann, 1994; Keller and Berry, 2003) From this broad perspective definition, ordinary individuals communicating with their friends, at the same time that experts, journalists, and other semi-public figures, as may highly visible public figures like media representatives, celebrities, and government officials are capable of influencing very different numbers of people, but may also exert quite different types of influence on them, and even transmitting hence via different media. That all of these sorts of individuals can be and have been referred to as influencers means only that the label itself is not terribly meaningful absent further refinement (Bakshy et al., 2011).

Typical characteristics of influentials are being informed, respected, and (strategically) well connected (Schenk et al. 2009; Cha et al. 2010). There are more specific terms related to influence ranging from opinion leaders (Lazarsfeld et al., 1948; Katz and Lazarsfeld, 1955) over innovators in the diffusion of innovations theory (Rogers, 1962) to hubs or connectors in other works (Gladwell, 2000). Overall, opinion leaders can be described by their social rather than personal characteristics; they influence people with similar socio-demographic characteristics in particular (Schenk et al. 2009).

Nevertheless, so-called political influentials or opinion-makers exist who are said to have an impact on the political opinion making and agenda-setting processes as well as on communication behaviour of other users. However, little research has been devoted to address the measurement of influence on Twitter (Cha et al., 2010; Kwak et al., 2010; Weng et al., 2010; Bakshy et al., 2011).

Influence on Twitter is connected to network topology. As Dang-Xuan et al. (2013) recently pointed out, there are basically three different approaches which the notion of influence is based upon: (1) followership influence, (2) retweet influence, and (3) mention influence.

The first approach refers to the quantity of followers of a user. Beyond the mere number of followers, recent studies have proposed other followership-based measurements based on PageRank and TwitterRank algorithms which take into account both the topical similarity between users and the followership structure (Kwak et al., 2010; Weng et al., 2010; Krishnamurthy et al., 2008).

The second approach is based on retweeting, which indicates the ability of that user to generate content with pass-along value. Alternatively, some other studies have proposed influence in terms of the size of the entire diffusion tree associated with each event which is more directly associated with the diffusion and dissemination of information (Kwak et al., 2010; Bakshy et al., 2011).

The final approach for influence emphasizes mentioning as an indicator the ability of a user to engage others in a conversation. Here, the number of mentions a user receives may serve as measure of influence.

Most of the studies about the influence on Twitter have combined a mixed measure of these three parameters. For example, Kwak et al. (2010) compared three different measures of influence – number of followers, page-rank and number of retweets – and they found that the ranking of the most users differed depending on the measure. Cha et al. (2010) also compared three different measures of influence – number of followers, number of retweets, and number of mentions – and also found that the most followed users did not necessarily score highest on the other measures. Weng et al. (2010) compared number of followers and page-rank with a modified page-rank measure that accounted for topic, again finding that ranking depended on the influence measure. Finally, Bakshy et al. (2011) studied the distribution of retweet cascades on Twitter, finding that although users with large follower counts and past success in triggering cascades were on average more likely to trigger large cascades in the future, these features are in general poor predictors of future cascade size.

However, broader understanding of influence on Twitter should thus not be limited to the audiences that one can address directly, but also those that can be reached indirectly through ones direct audience (Vaccari and Valeriani, 2013; 2013a). In this regard we should consider not only the specific activity of politicians, but also their followers activity and numbers of followers. Consequently, these followers personal networks on social media could highly expand the reach of the campaign beyond the candidate or the partys direct audiences. In this sense, the potential for indirect communication depends on how active, engaged, and connected are the people who follow that politician. The task is, therefore, to identify who are these power followers (Vaccari and Valeriani, 2013) that become into powerful channels of indirect communication for politicians.

In this research we analyze direct influence on Twitter driven from candidates to their followers with a comparative perspective. And indirect influence is included with the attempt to identify with whom candidates indirectly interact more through the practice of retweeting. However, in a second phase of the research, we will also include a deep analysis of the social network of those power followers that can better explain the indirect influence of main candidates. Results will respond to the research question related in what extend politicians are using the technology for social dialogue or, by contrary, they continue considering social networks as a one-way communication tool, so that they are missing an opportunity to enchance democracy.

Methodology

The research question of this paper is to answer who is talking about what and with whom in Twitter in the case of the Spanish and Portuguese politicians running for EU 2014 elections. The European Elections is a suitable scenario for a comparative approach for two countries with a similar political and media landscape. Portugal and Spain are two culturally similar countries, with political and media traditions very similar. A study of André Freire (2006) demonstrates that, in European politics, Portugal and Spain share similar values both to politicians as their voters. In this sense, the author presents the findings of a study that concludes that the two countries populations have a lower degree of positioning in the ideological scale and a strong resemblance to the argument that the ideological positioning of the individual depends on the political, parties sympathies and positioning in the socio-cultural structure. In both countries, two parties have always dominated the European elections: PP and PSOE in Spain and PSD and PS in Portugal. However, the tendency to the end of bipartisanship is substantially identified on the Iberian Peninsula with the appearance of new parties, the strengthening of smaller parties and a strong substantially of citizens' movements. Therefore, we consider that the comparison between the campaigns for the European elections on Twitter by candidates from Portugal and Spain is a contribution to analyze the online political strategies in both countries and its repercussions. We also emphasize that this study is developed in a specific moment where the internal politics of each country are facing similar changes.

Our main hypothesis is exploring the idea that political candidates still do not reach the microblogging to become a real influential or opinion leader in the Twittersphera. Other actors like ordinary citizens, journalists and political activist are more prominent and active in Twitter to lead the public discussion, even during electoral times. This hypothesis comes from studies that are underlining the role of Twitter as venue for politicians to connect with journalists and politically engaged citizens (Grant et al., 2010). It is important to study politicians as influential for a better understanding of the nature of diffusion of political issues on Twitter (Dang-Xuan et al., 2013).

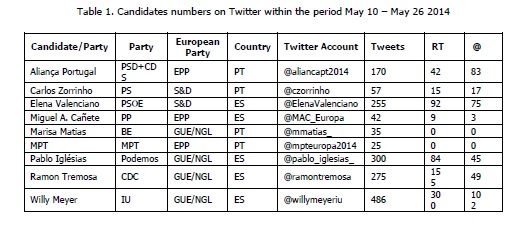

The sample of this paper has been the main candidates of each political party running for EU 2014 Elections. The Spanish sample is made with the Twitter accounts of the five main candidates who obtained representation in the last European elections (May 25, 2014). They were Arias Cañete (PP, @Canete2014_), Elena Valenciano (PSOE, @ElenaValenciano), Willy Meyer (IU, @WillyMeyerIU), Pablo Iglesias (Podemos, @Pablo_Iglesias_) and Ramón Tremosa (CIU, @ramontremosa). The Portuguese sample consists of four Twitter accounts of the five parties that were elected to represent Portugal at the European Parliament in the last European elections. The Twitter accounts are from Carlos Zorrinho (PS – left wing party, @czorrinho – the 3rd on the party list of candidates), Aliança Portugal (account created by the coalition of PSD and CDS – right wing parties – to represent them on Twitter during the elections, @AliancaPT2014), Marisa Matias (BE – left wing party, @mmatias_) and MPT (the account of this left wing party was used to communicate with the voters through Twitter).

The empirical design is based, firstly, on a quantitative content analysis of each candidate tweet feeding for data collection. Data were recorded and downloaded with the social tool Facepager, during the period May 10 – May 26 2014 (a total of 17 days), collecting of the tweets during the two weeks before elections day, the day itself and the day after. Following the literature suggestions about the opportunity of Twitter for framing the campaign strategy (Capella & Jamieson, 1997; Parmelee & Bichard, 2012) we also looked to what type of frame are more used on the candidates Twitter accounts – considering strategic, issue and personal frames. Concretely, we compared number or tweets, retweets, replies and mentions of each candidate Twitter account. We also pay attention to type of topics they mostly used and how they where framed (what they were talking about? in what terms?) and people that where mentioned on the replies (with who they were talking about?). The use of an integrated methodology (including both quantitative and qualitative approaches) helped us make a characterisation of each Twitter account and discern what the strategy behind.

Findings and Discussion

a) Candidates activity in Twitter sphere

Twitter was a tool mainly used as a unidirectional channel by the Spanish candidates to offer information more than an interactive way to interact with other politicians, journalists or regular citizens in an authentic culture of participation. There are significant differences among the five main Spanish candidates regarding the quantity of tweets used for this purpose (in this regard, the IU candidate Willy Mayor is the one who used more frequently Twitter in comparison with the PP candidate Arias Cañete, who barely used this tool). However, they all have in common the lack of used of this tool as a full communicative way taking into account the responds of other to these messages. During the period of analysis, the Twitter account of Miguel Arias Cañete (@MAC_Europa) only wrote 42 tweets, followed by Elena Valenciano (@ElenaValenciano) with 255 tweets, Pablo Iglesias (Podemos, @Pablo_Iglesias) with 300, Ramón Tremosa (CIU, @ramontremosa) with 275 tweets and Willy Meyer (IU, @WillyMeyerIU) with 486 tweets. As there is a lack of direct conversation, the data reveals that indirect conversation (retweets) was a very intense activity for almost Spanish candidates (except Arias Cañete).

The accounts analysed reveal specificities of online communication of Portuguese politicians, including the fact that some parties do not have any representation on Twitter (like PCP - left wing party) or others that create accounts for specific elections. It was also found that the main opposition party (Socialist Party - left wing party) has an official account without practically address to the European elections and only the 3rd candidate on the list have a Twitter account. An aspect to be highlighted from this analysis is that the candidate of BE, Marisa Matias, never wrote directly on Twitter. During the analysed period, her account has been a repository of feeds from Facebook and YouTube. Another interesting aspect to emphasize was that the MPT initially have a specific account for the European elections but deleted it without any warning to the users who followed them. The account of the party began to be used for communication on the European elections. Yet another fact to be noted is that the main opposition party (Socialist Party) has not considered the European elections in their official account. The Socialist candidate who we followed in this study, Carlos Zorrinho, has an account where he publishes political content and personal content.

Portuguese candidates used Twitter primarily as a tool for disseminating information in a unidirectional perspective and, in most cases, without consistency. There are significant differences among the accounts regarding the quantity of tweets and the kind of messages, however it is absolutely clear the reduced number of publications from the four accounts. During the period of analysis, Twitter account of MPT wrote 25 tweets, Marisa Matias have tweeted 35 times, followed by Carlos Zorrinho with 57 tweets and Aliança Portugal 2014 with 170. These numbers reveal the lack of used of Twitter as a tool for political communication, either through direct or indirect conversation with the audience.

b) Candidates agenda of issues

Almost all the Spanish and Portuguese candidates prioritize metacampaign issues as main topic framing their content on Twitter. For instance, the 80% of the content published by Aliança Portugal (@Aliancapt2014) on this social media was related directly to metacampaign issues such as information about rallies or meetings. In Pablo Iglesias case, 70,3% of his tweets were about this issue, followed by Ramon Tremosa with 67,8%, Elena Valenciano with 65,5% and Marisa Matías with 45,7%. Regarding the second topic addressed, there are significant differences between Spanish and Portuguese candidates, as long as between left wing parties and right wing ones. Spanish candidates focused more on social politics and corruption than the Portuguese. In Portugal, just Marisa Matias talked on social issues such as education or health-care (31,1% of her tweets). In Spain, Willy Mayer (20,4%) and Elena Valenciano (16,5%) are the candidates who spoke the most on these issues. Pablo Iglesias focused more on the deep crisis of the Spanish political system talking mainly about issues linked to corruption, fraud or political disaffection (20,7%).

European Elections were framed within a national debate by the running candidates taking into account specific national problems and challenges more than European ones. Pablo Iglesias framed his discourse on Twitter in national issues (96,7%), followed by Elena Valenciano (82%) and Aliança Portugal (63,5%). Willy Meyer (61,3%), Ramon Tremosa (55,7%) and Marisa Matias (54,3%) framed their discourse in an European perspective. Despite the possibilities offered by Twitter, the personal frame barely had presence in any of the candidates. Only Carlos Zorrinho shows significant numbers on this (54,4%). The others candidates used mainly a generic frame based on a strategic horse race.

c) Candidates social interaction in Twitter sphere

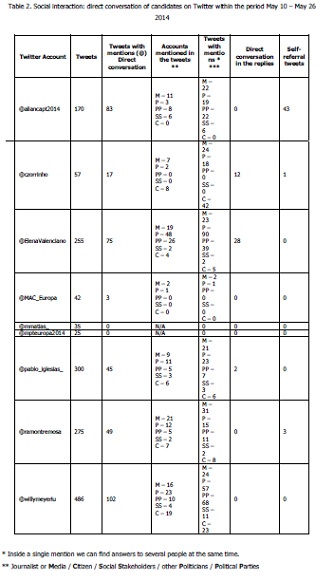

There are meaningful disparities among the four accounts from the Portuguese candidates regarding the interaction with other citizens, politicians or journalists and a lack of direct conversation with other social agents. Aliança Portugal 2014 was the account that has published more mentions to others to contextualize information or referencing content, people or events. However, never interacted directly in conversation with anyone. MPT and Marisa Matias have no replies at all during all the analysed period. Carlos Zorrinho is the only candidate who used Twitter to interact in a more productive way, answering to questions or mentioning other users in a political and personal context.

In order to see with whom the candidates interact to in a direct conversation on Twitter, we analysed the people mentioned in the replies and the direct conversation conducted from their own Twitter accounts. Only Carlos Zorrinho talked to journalists, citizens and other politicians. Aliança Portugal mentioned journalists, citizens, other politicians and social agents but just to contextualized information.

As stressed before, Twitter has been not used by Spanish candidates to build a direct conversation on their own political ideas with other social agents such as journalists or media, citizens, social stakeholders like civic association or just other politicians. The number of tweets with direct replies is significantly low, illustrating the lack of direct conversation with other social agents. Elena Valenciano is the exception with 28 direct replies within 75 tweets of direct conversation.

All the Spanish candidates mentioned journalists, other politicians and political parties to contextualize their tweets. Mainly Willy Meyer mentioned citizens. Elena Valenciano, Pablo Iglesias and Ramon Tremosa also referred Twitter accounts from citizens but in a small proportion. With the exception of Arias Cañete, all the Spanish candidates use direct conversation through mentions of other social agents also in order to referencing content, people or events. Political parties, politicians and media (journalists and media outlets accounts) were referred more often. Willy Meyer and Elena Valenciano were the most active candidates, mentioning several accounts in each tweet.

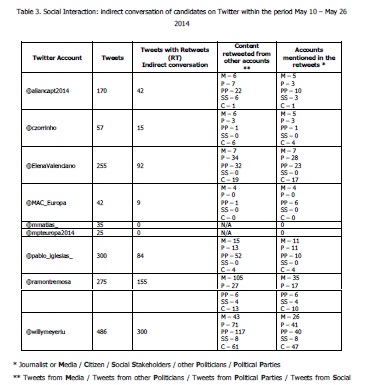

Spanish candidates often used indirect conversation, as it can be seen in table 3. Tweets from political parties other politicians and media were more often retweeted. From the Portuguese candidates, only AliançaPT2014 and Carlos Zorrinho did retweets.

More than half of tweets published by Willy Meyer and Ramon Tremosa were retweets (300 and 155, respectively). Pablo Iglesias and Elena Valenciano also had an intense activity of indirect conversation.

The most central players in retweets network are accounts of political parties, politicians and media. We found that they are user accounts with recognized influence (online and/or offline). Few ordinary users fit this profile. We noted that usually these users receive more referrals than they do and have more followers than follow.

As media accounts were often retweeted to referencing an event or data from polls, retweets from other politicians from the same party (or European party) and political parties (essentially regional accounts of the parties) intended to validate and give credibility to the candidate's political messages as well as refer political events (rallies and debates in the media).

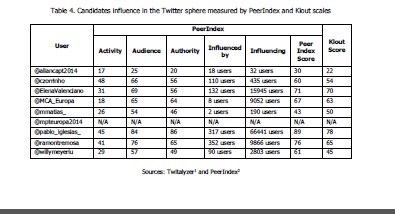

d) Candidates influence in Twitter sphere

In order to analyze the influence of the candidates in the Twitter Sphere, we applied two scales of influence that allow us to understand the main features of the profiles. Klout assesses the sphere of influence of users in a scale of 1 to 100, which is based on 35 variables and evaluates range, likely audience and amplification by the authorities multiplication network. The PeerIndex scale measures the user authority making an assessment of the impact of the activities and the social and relational capital built by examining authority (confidence measure), audience (user range) and activity (quantification of shares) to establish results of representations between 1 and 100.

Both scales weigh factors such as the following, mutual followers, friends, total retweets, ratio followers/followed, percentage of followers to reciprocate the bond, total mentions, references to lists, references in lists of followers, number of users that have made retweets of messages, number of messages that received retweets, percentage of retweets by followers, number of users that reference profile, percentage of followers who mentioned the user, total messages posted, influence of followers, influence of users that make retweet and users that mention the profile.[1][2]

There are significant differences in the three analytical levels scores of the PeerIndex scale (activity, audience and authority) in almost candidates. Users with higher confidence levels can overcome lower activity records. In terms of audience, the levels are relatively consistent. These inconsistencies can be explained by the elements of the assessments. PeerIndex examines the social and relational capital on the basis of the activities, which may explain that accounts as less interaction with other users have reduced scores compared with the results of Klout scale (@aliancapt2014, @willymeyeriu, @ramontremosa, @pablo_iglesias_). Users with more followers have higher results, with a higher correspondence between the scores on the two scales. In most cases, high levels of audience and authority allow to infer social and relational capital with a significant dimension in the Twitter network users in terms of influence.

All the Spanish candidates score above 50 points in both scales, with the exception of Willy Meyer on Klout scale (45 points). Portuguese candidates, only Carlos Zorrinho is consistent in both scales. Marisa Matias has 50 points in Klout scale and have high scores audience and authority, but despite scoring 43 points in PeerIndex scale has a reduced level of direct influence (190 users).

The number of users directly influenced by the candidates is very significant in the case of Elena Valenciano, Arias Cañete, Pablo Iglesias and Ramon Tremosa. Willy Meyer and Carlos Zorrinho have lower numbers, although significant in our sample (2803 and 435 users respectively). The other Portuguese candidates reveal lack of direct influence of capacity on others users.There is no connection between the number of users that influence the candidates and the number of users influenced by them.[3]

Elena Valenciano is the candidate with a higher percentage concerning the direct conversation with other users. However, amounts to only 7.5%. Willy Meyer has a percentage of 4% of direct conversations, while Carlos Zorrinho and Pablo Iglesias have a proportion of 3.5%. Arias Cañete has only 1% and Ramon Tremosa has 0%. The remaining candidates have accounts with highly reduced activity, making it impossible to gauge the percentage of retweets and direct replies through this tool.

All candidates (whose data was possible to measure) reveal interesting percentages in terms of retweets, although Arias Cañete and Pablo Iglesias are below 50%.

The engagement with the audience summarizes the sum of the percentages of engagement by retweeting (indirect conversation) and replies (direct conversation). Again, only Arias Cañete and Pablo Iglesias are below 50%. Elena Valenciado is the candidate with the highest percentage, showing consistency with the data of hearing and PeerIndex scale of authority and the scores on the two scales.

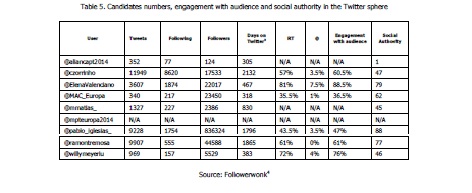

In table 5, social authority is composed of the retweet rate of users' in the last few hundred tweets, the recency of those tweets and a retweet-based model design by Followerwonk on user profile data. All the candidates have a score above 45 except AliançaPT2014, a Twitter account created for the campaign. The account from MPT was deleted from Twitter just after the elections and it was also created for the campaign. Therefore, there is no data concerning the influence of this user.

Conclusions

In this paper we have present a study about flows of communication from Portuguese and Spanish politicians on Twitter. Our main goal was to identify in to what extend the Spanish and Portuguese politicians running for European Elections in 2014 became real opinion leaders on Twitter during the campaign. The theoretical framework was based on the idea of new influentials on political communication in the new media ecosystem.

The paper is focused in the assumption that campaigning on Twitter ecosystem could reveal politicians as new influentials. Therefore, we conducted a study based on quantitative and qualitative measures to analyse the influence of the most representative politicians, candidates in the European Elections, from Spain and Portugal on Twitter.

We found that in the Spanish case there is significantly more content publishing on Twitter, although the reduced direct interaction with other users. In the Spanish case, journalists and citizens are the social agents more presence in the direct conversation. In the Portuguese case, the culture of social interaction is lower, almost residual. There is only one candidate that makes a direct conversation with journalists, politicians and other citizens. There is another account that does more mentions, however all for contextualization of information. In both case studies, we find out that the flow of conversation and interaction by direct replies with other social agents is residual, being almost insignificant. There are no evidence, through this kind of direct conversation, that the candidates have any social influence on voters due to their presence and activity on Twitter.

The results demonstrated that Twitter was not used to build a direct conversation with other social agents. Social conversations of candidates on Twitter were mainly achieved through indirect interaction (retweets). There is no evidence of direct influence through mentions and indirect conversation was often focused on social actors like media, political parties and other politicians. Therefore, it is possible to infer that the flows of conversations of Portuguese and Spanish candidates to 2014 European Election were essentially unidirectional channels to disseminate information and capitalize social reputation through regular references to social actors recognized in the sphere offline. So that, results showed that political candidates still do not reach the microblogging to become a real influential or opinion leader in the Twittersphera.

Although the Internet has introduced a multistep flow of communication, political communication on Twitter evidences that is still based in a one-way communication model for diffusion of information. The lack of engagement through direct interaction reveals that politicians cannot be considered new influentials. Therefore, measures of audience, authority and social authority are an almost direct transposition from their offline influence to the online sphere.

References

Aharony, N. (2012) Twitter use by three political leaders: an exploratory analysis, Online Information Review, Vol. 36 Iss: 4, pp. 587- 603. [ Links ]

Ammann, S. L., (2010) A political campaign message in 140 characters or less: the use of Twitter by U.S. Senate Candidates in 2010, Social Science Research Network, http://ssrn.com/abstract=1725477 (visited 2/09/2011). [ Links ]

Ancu, M., From Soundbite to Textbite. Election 2008 Comments on Twitter, en Hendricks, J. A., y Kaid, L. (eds.) (2011) Techno Politics in Presidential Campaigning. New Voices, New Technologies, and New Voters, New York, Routledge, pp. 11-21. [ Links ]

Arroyo, L. (2012) 10 razones por las que Twitter no sirve para (casi) nada en política, in blog http://www.luisarroyo.com/2012/05/06/10-razones-por-las-que-twitter-no-sirve-para-casi-nada-en-politica/, 2012 (visited 20/07/2012). [ Links ]

Bakshy, E.; Hofman, J.; Mason, W. and Watts, D. (2011) "Everyone´s an influencer: quantifying influence on twitter" in Proceedings of the Fourth ACM International Conference on Web Research and Data Mining, 2011, Hong Kong, China, 9-12 February. [ Links ]

Beas, D. (2011) La reinvención de la política: Obama, Internet y la nueva esfera pública, Península, Madrid. [ Links ]

Bimber, B., y Davis, R. (2003) Campaigning online. The Internet in U.S. elections, Oxford University Press, Oxford. [ Links ]

Bruns, A., y Burgess, J. E. (2011) #Ausvotes: How Twitter covered the 2010 Australian federal election, Communication, Politics and Culture, 44 (2), p. 13. [ Links ]

Caldarelli, G., Chessa, A., Pammolli, F., Pompa, G., Puliga, M., (2014) A Multi-Level Geographical Study of Italian Political Elections from Twitter Data. PLoS ONE 9(5): e95809 (DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0095809) [ Links ]

Cha, M.; Haddadi, H.; Benevenuto, F. and Gummad, K. P. (2010) "Measuring user influence on Twitter: the million follower fallacy", in Proceedings of the 4th International AAAI Conference on Weblogs and Social Media, Washington, DC, 23–26 May 2010, AAAI Press, Menlo Park, CA, pp. 10–17

Criado, J. I., Martínez-Fuentes, G. and Silván, A. (2012): Social Media for Political Campaigning. The Use of Twitter by Spanish Mayors in 2011 Local Elections. En Reddick, C.G. y Aikins, S. K. (eds.): Web 2.0 Technologies and Democratic Governance. Nueva York: Springer. pp. 219-232. [ Links ]

Dang-Xuan, L., Stieglitz, S., Wladarsch, J., & Neuberger, C. (2013). An investigation of influentials and the role of sentiment in political communication on Twitter during election periods. Information, Communication & Society, 16(5), 795-825. [ Links ]

D´heer, E. and Verdegem, P. (2014) Conversations about the elections on Twitter: Towards a structural understanding of Twitter's relation with the political and the media field, European Journal of Communication (in press). [ Links ]

Dang-Xuan, L., Stieglitz, S., Wladarsch, J. and Neuberger, Ch. (2013) An Investigation of Influentials and the Role of Sentiment in Political Communication on Twitter during Election Periods, Information, Communication & Society, vol.16, issue 5, pp. 795-825 (DOI 10.1080/1369118X.2013.783608) [ Links ]

Deltell, L., Claes, F. y Osteso, J. M. (2013): Predicción de tendencia política por Twitter: Elecciones Andaluzas 2012. Ámbitos. Revista Internacional de Comunicación Vol. 22. Disponible en http://ambitoscomunicacion.com/2013/prediccion-de-tendencia-politica-por-twitter-elecciones-andaluzas-2012/ [ Links ]

Keller, E. and Berry, J. (2003) The Influentials: One American in Ten Tells the Other Nine How to Vote, Where to Eat, and What to Buy. Free Press, New York, [ Links ] NY.

Enli, G. S. and Skogerbo, E. (2013) Personalized-campaigns in party-centred politics: Twitter y Facebook as arenas for political communication, Information, Communication and Society, 16 (5), pp. 757-774. [ Links ]

Freire, A. (2006). Esquerda e Direita na Política Europeia: Portugal. Espanha e Grécia em Perspectiva Comparada, Lisboa, ICS. [ Links ]

Gladwell, M. (2000) The Tipping Point: How Little Things Can Make a Big Difference, Little Brown, New York. [ Links ]

Glassman, M.E., Straus, J.R. and Shogan C.J. (2010) Social Networking and Constituent Communication: Member Use of Twitter during a Two-Week Period in the 111th Congress Congressional Research Service. [ Links ]

Golbeck, J., Grimes, J.M. and Rogers, A. (2010) Twitter Use by the U.S. Congress. Journal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology, 61(8): 1612–1621. [ Links ]

Grant, W.J., Moon B. and Grant, J.B. (2010). Digital Dialogue? Australian Politicians use of the Social Network Tool Twitter, Australian Journal of Political Science, 45(4): 1-37. [ Links ]

Guardián, C., Topología de la comunidad política española en Twitter, en K-government blog http://www.k-government.com/2011/11/18/topologia-de-la-comunidad-politica-espanola-en-twitter/, 2011 (visitado 6/06/2012). [ Links ]

Harfoush, R. (2010) Yes we did. Cómo construimos la marca Obama a través de las redes sociales, Planeta, Barcelona. [ Links ]

Hendricks, J. A. and Denton, R. E. (eds.) (2010) Communicator-in-chief. How Barack Obama used new media technology to win the Withe House, Lexington Books, Lanham. [ Links ]

Hendricks, J.A. and Jerry K. Frye Social Media and the Millennial Generation in the 2010 Midterm Election. In H.S. Noor Al-Deen and J.A. Hendricks (eds.) (2011) Social Media: Usage And Impact, PA: Lexington Books.

Holotescu, C., Gutu, D., Grosseck, G., y Bran, R. (2011) Microblogging meets politics. The influence of communication in 140 characters on Romanian presidential elections in 2009, Romanian Journal of Communication and Public Relations 13 (1), pp. 37-47. [ Links ]

Honeycutt, C., and Herring, S. C. (2009) Beyond microblogging: Conversation and collaboration via Twitter, In Proceedings of the Forty-Second Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences.Los Alamitos, CA IEEE Press. (conference paper) [ Links ]

Hong, S and Nadler, D. (2011) "Does the early bird move the polls? The use of the social media tool "Twitter" by U.S. politicians and its impact on public opinion", in Proceedings of the 12th International Conference on Digital Government Research, College Park, MD, 12-15 June 2011, pp. 182-186.

Hong, S. y Nadler, D. (2012) Which Candidates Do the Public Discuss Online in an Election Campaign?: The Use of Social Media by 2012 Presidential Candidates and its Impact on Candidate Salience, Government Information Quarterly, Vol. 29, pp 455-461.Available at SSRN: http://ssrn.com/abstract=2323214. [ Links ]

Izquierdo, L. (2012): Las redes sociales en la política española: Twitter en las elecciones de 2011. Estudos em Comunicaçao Nº 11. pp. 139-153. [ Links ]

Jungherr, A. (2010) Twitter in politics. Lessons learned during the German superwahljahr 2009, paper presented at the Workshop on Microblogging at the CHI 2010, Atlanta (USA), 10-15/04/2010: http://andreasjungherr.net/2010/04/10/twitter-in-politics-lessons-learned-duringthe-german-superwahljahr-2009/, 2010 (visitado 16/09/2010).

Jürgens, P., Jungherr, A., & Schoen, H. (2011, June). Small worlds with a difference: New gatekeepers and the filtering of political information on Twitter. In Proceedings of the 3rd International Web Science Conference (p. 21). ACM. [ Links ]

Katz, E. and Lazarsfeld, P. (1955) Personal Influence. The part played by people in the flow of mass comunication. Glencoe, Il: Free Press. [ Links ]

Kruikemeier, S., Van Noort, G., Vliegenthart, R., y De Vreese, C. H. (2013) Getting closer: The effects of personalized and interactive online political communication, European Journal of Communication, 28 (1), pp. 53-56. [ Links ]

Kwak, H., Lee, Ch., Park, H. and Moon, S. (2010) What is Twitter, a social network or a news media? paper presented at the 19th International Conference on World Wide Web, Raleigh. [ Links ]

Larsson, A. O., and Moe, H. (2013) Representation or Participation? Twitter use during the 2011 Danish Election Campaign, Javnost-The Public, 20 (1), pp. 71-88. [ Links ]

Lazarsfeld, P. F., Berelson, H. & Gaudet, H. (1948) The Peoples Choice. How the Voter Makes Up His Mind in a Presidential Campaign, Columbia University Press, New York. [ Links ]

Medvic, S.K. Campaign Management and Organization. "The Use and Impact of Information and Communication Technology En Medvic, S. K. (ed.) (2011) New Directions in Campaigns and Elections, Routledge: New York (pp. 59-78).

Parmelee, J. H. and Bichard, S. L. (2012) Politics and the Twitter revolution. How tweets influence the relationship between political leaders and the public, Lexington Books, Lanham. [ Links ]

Rogers, E.M. (1962) Diffusion of innovations. The Free Press, New York. [ Links ]

Schenk, M.; Jers, C. and Tschörtner, A. "Wer ist Meinungsführer?" -zur Diffrenzierung des Meinungsführerkonzeptes", in Dahinden, U. and Süss, D. (eds) (2009) Kommunikationswissenchaft Medienrealitäten, UVK, Konstanz, pp. 187-200.

Schlozman, K., Verba, S., y Brady, H. E. (2010) Weapon of the Strong. Participatory Inequality and the Internet, Perspectives on Politics, 8, pp. 487-509. [ Links ]

Schweitzer, E. J. (2012) The Mediatization of E-Campaining: Evidence From German Party Websites in State, National, and European Parliamentary Elections 2002-2009, Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, 17, pp. 283-302. [ Links ]

Small, T.A. (2012) The Not-So Social Network: The Use of Twitter by Canadas Party Leaders. Paper submitted to the XXIInd World Congress of Political Science, Madrid Spain8-12 July 2012. [ Links ]

Solop, F. I. RT @BarackObama We Just Made History. Twitter and the 2008 Presidential Election, En Hendricks, J. A., y Denton, R. E. (eds.) (2009) Communicator-in-Chief. A Look at How Barack Obama used New Media Technology to Win the White House, Lexington Books, Lanham, pp. 37-50.

Toledo, M.; Galdini, R.L. and Travitzki, R. (2013) Gatekeeping Twitter: message diffusion in political hashtags, Media Culture and Society, vol. 35: 260, pp. 260-270. [ Links ]

Thimm, C., Einspänner, J. and Dang-Anh, M. (2012) Twitter als Wahlkampfmedium. Modellierung und Analyse politischer Social-Media-Nutzung, Publizistik, vol. 57, nº3, pp. 293-313. [ Links ]

Vaccari, C. and Valeriani, A. (2013)Follow the leader! Dynamics and Patterns of Activity among the Followers of the Main Italian Political Leaders during the 2013 General Election Campaign, paper presented at the conference Social Media and Political Participation New York University, Florence, May 11, 2013. [ Links ]

Vaccari, C. and Valeriani, A. (2013a) Follow the leader! Direct and indirect flows of political communication during the 2013 general election campaign, New Media & Society, Sage, pp. 1-18 (DOI: 10.1177/1461444813511038). [ Links ]

Vaccari, C. (2008) From the air to the ground. The Internet in the 2004 US presidential campaign, New Media & Society, 10 (4), pp. 647-665. [ Links ]

Vergeer, M. and Hermans, L. (2013) Campaigning on Twitter: micro-blogging and online social networking as campaign tools in the 2010 general elections in the Netherlands, Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, 18 (4), pp. 399-419. [ Links ]

Weimann, G. (1982) On the importance of marginality: One more step into the two-step flow of communication. American Sociological Review, 47, pp. 764-773. [ Links ]

Weimann, G. (1994) The influentials. People who influence people. Albany: State University of New York Press. [ Links ]

Weimann, G.; Tustin, D. H.; van Vuuren, D. and Joubert, J. P. R. (2007) Looking for opinion leaders: traditional vs. modern measures in traditional societies, International Journal of Public Opinion Research, Summer 2007, Vol. 19 Issue 2, pp173-190. [ Links ]

Weller, K., Bruns, A., Burgess, J., Mahrt, M., y Puschmann, C. (eds.) (2013) Twitter and Society, New York, Peter Lang. [ Links ]

Weng, J., Lim, E. P., Jiang, J. and He, Q. (2010) "TwitterRank: finding topic-sensitive influential twitterers", in Proceedings of the Third ACM International Conference on Web Search and Data Mining, New York City, NY, 3–6 February 2010, pp. 261–270.

Wu, S; Hofman, J.M; Mason, W.A and Watts, D.J. (2011) "Who says what to whom on Twitter?" In Proceedings of the 20th ACM International World Wide Web Conference, Hyderabad, India, 28 March-1 April 2011. [ Links ]

Yardi, S. and Boyd, D. (2010) Dynamic debates: An analysis of group polarization over time on Twitter, Bulletin of Science, Technology & Society, 30 (5), pp. 316-327. [ Links ]

Zamora, R. and Zurutuza, C. (2014) Campaigning on Twitter: Towards the Personal Style Campaign to Activate the Political Engagement During the 2011 Spanish General Elections, Communicación y Sociedad, 27(1), pp. 83-106. [ Links ]

NOTAS

[1] Available in http://www.twitalyzer.com

[2] Available in https://piq.peerindex.com

[3] Available in http://www.followerwonk.com/