Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Accesos

Accesos

Links relacionados

-

Similares en

SciELO

Similares en

SciELO

Compartir

Observatorio (OBS*)

versión On-line ISSN 1646-5954

OBS* vol.9 no.4 Lisboa dic. 2015

A peaceful pyramid? Hierarchy and anonymity in newspaper comment sections

João Gonçalves*

*Investigador – Colaborador, Centro de Estudos Comunicação e Sociedade, Universidade do Minho, Campus de Gualtar, 4710-057 Braga, Portugal. (id5322@alunos.uminho.pt)

ABSTRACT

Several studies have linked deindividuation to an increase in aggression and incivility. This paper seeks to ascertain the influence of anonymity and hierarchy in online aggression by comparing two different newspaper comment sections: one with a hierarchical system and the other with an equalitarian setting. This study distinguishes itself form previous works by analyzing systems where identification is optional and where identified and anonymous users coexist.

The hierarchical solution might be relevant to dissuade aggression when optional identifiability is seen as an essential asset. Results show that a hierarchical system provides some improvements in terms of civility and comment moderation, but that poor implementation of the hierarchy causes perversions in the system and affects its effectiveness.

Keywords: Comment Sections; Participation; Online Aggression; Anonymity.

The Community Memory public bulletin board system, set up in Berkeley in 1973, clearly illustrates the optimism that surrounded the advent of new Information and Communication Technologies. This enthusiasm was patent in the project’s instruction manual: “With this, we can work on providing the information, services, skills, education, and economic strength our community needs”(Cybernetics, 1972). The technology that allowed Community Memory to surface soon became obsolete, but the idea that new communication technologies could bring social change through public debate lived on. This perspective found its echo in the words of some authors (Barton, 2005; Dahlgren, 2000; Lévy, 2003), who saw the possibilities offered by the Internet as a way of generating a public discursive and deliberative structure with the contours of the Great Community (Dewey, 1927) or of a critical Public Sphere (Habermas, 1989).

On the same line of thought as these authors, several projects1 have appeared all over the Internet that strive to embody and operationalize the concept of democratic civic intelligence: “Civic intelligence is the ability of groups and organizations and, ideally, society as a whole to conceive and implement effective, equitable, and sustainable approaches to shared problems.” (Schuler, 2008, p. 83). The thought that any individual, provided that they have access to the internet and the digital literacy to use it, can actively interevene on the discussion and deliberation of current events (Dahlberg, 2001), along with the central role that ICT’s have played in major political events of the last few years (Castells, 2012), generates great expectations about the potential of the Internet as a medium to revitalize democracy and stimulate public debate and social change.

However, while some studies find traces of democratic quality on online speech (Ruiz et al., 2011; Strandberg & Berg, 2013), many others raise concerns over the presence of a significant amount of offensive, aggressive and deviant messages on Internet debates (Benson, 1996; Chung, 2007; Coe, Kenski, & Rains, 2014; Silva, 2013). This kind of toxic contributions, along with some social and political discoursive inequalities that are reproduced in the online environment (Papacharissi, 2002), prevent the emergence of an online public sphere and give strenght to those who, like Walter Lippman (1997, p. 233), doubt the ability of the public to contribute to the government of a nation: “Our own democracy, based though it was on a theory of universal competence, sought lawyers to manage its government, and to help manage its industry”.

In spite of the fact that aggressive messages might reduce the quality and salubrity of online discussions, it would be hasty to disregard all forms of aggression and deviance as pointless and irrational, since these can also be a strategy to fight power inequalities. The more oficial and formal a linguistic market is, the more dominated it is by the dominant (Bourdieu, 1998). Aggression is way for those with less argumentative resources to reverse the power balance through the use of discoursive force. As Dahlgren (2006, p. 157) puts it: “the perspective of deliberative democracy risks downplaying relations of power that are built into communicative situations.” Nevertheless, this use of aggression as a power strategy cannot explain, by itself, why aggression surfaces so easily on online environments and it certainly does not account for all cases of deviant speech.

Toxic desinhibition

Toxic disinhibition is an expression coined by John Suler (2004) to describe the behavior people adopt online that they would never consider as an option in the ‘real’ world. On his paper, Suler (2004) listed the psychological effects that contributed to online disinhibition, which often was manifested in its negative, toxic form. Of the six factors he named, two are of particular interest for our work: dissociative anonymity and dissociative imagination. The difference between the two is best explained in Suler’s (2004, p. 324) own words: “Under the influence of anonymity, the person may attempt an invisible non-identity, resulting in a reducing, simplifying, or compartmentalizing of self-expression. In dissociative imagination, the expressed but split-off self may evolve greatly in complexity.” In our work, this difference is mirrored in the distinction between anonymous users and pseudonyms.

Although Gustave Le Bon (1947) advanced the idea that deindividuation is linked to aggression, the connection between anonymity and aggressive behavior was established in an experiment designed by Zimbardo (1969), in which he observed that anonymous hooded subjects were more aggressive when administering electric shocks than clearly identifiable subjects. If we direct our attention to studies that analyze the online implications of this phenomenon, we will find a landscape of mixed conclusions. One study by Moore, Nakano, Enomoto, and Suda (2012), analyzing the online forum Formspring.me, revealed that posts without online identifiers (anonymous) tended to be more aggressive than identified posts. Similarly, in an experimental setting, a higher number of threats was detected under an anonymous condition then under an identifiable status (Lapidot-Lefler & Barak, 2012). However, a study by Douglas and McGarty (2001) showed that strategic motivations made identifiable subjects use more stereotype-consistent language than anonymous users. This study was developed on the framework of the Social Identity model of Deindividuation Effects (SIDE), which considers the strategic uses of anonymity depending on the nature and composition of the in-group and the out-group. Another study, by Tanis and Postmes (2007), shows that identity cues might have a paradoxical effect, they positively affect interpersonal perceptions but decrease perceptions of solidarity.

In face of the complexity of the anonymity problem, other variables need to be introduced in order to better understand the role of anonymity in computer mediated communication (CMC). Anonymity means different things in different websites and any analysis of online speech outside a laboratorial setting cannot afford to ignore the technical specifications that surround it.

In order to analyze the discursive variations induced by the different features associated with anonymity, we will direct our attention towards newspaper online comment sections. Many major newspapers have adopted this mechanism that allows readers to leave small messages or comments liked to a specific news article. This feature opens a new space for dialogue and discussion in the media, a space that could help save journalism from its economic crisis and stimulate public debate on current issues. These goals are, however, frustrated by the lack of civility and proliferation of aggression that is also present on other online spaces. The World Editors Forum recognizes that “(…) comment threads on websites can frequently shock due to abusive, uninformed, not to mention badly-written contributions” (Goodman & Cherubini, 2013, p. 5). Some of the studies cited above to illustrate the problem of toxic disinhibition used these comment sections as empirical material (Schuler, 2008; Silva, 2013) and others can be added to these (Blom, Carpenter, Bowe, & Lange, 2014; Santana, 2014). In face of these problems, news companies have implemented different moderation strategies and comment mechanisms in order to fight incivility.

Newspapers like The Guardian require users to register and create an account before they can comment. Some publications take the quest for identification one step further. In 2013, The Huffington Post, for example, forced commenters to associate their accounts to a Facebook profile in an effort to reduce incivility. The differences in the amount of civility caused by this Facebook integration measure were the object of Santana’s study (2014). The opposite strategy can also be found, where newspapers like the Houston Chronicle allow comments from unregistered users. Different approaches can also be seen regarding to moderation. While some newsrooms can spare the resources to moderate every comment before it is published (pre-moderation), others remove toxic comments after they are published (post-moderation). Facing the impossibility of finding an effective strategy, some websites like Popular Science resorted to the drastic measure of closing their comment sections altogether. Variations like these can be found and combined on several levels: user registration, anonymity policies, moderation systems, online social network integration, and user and comment reputation systems are some of the components that are decided by each newspaper when managing their comments section.

In spite of this quest to find the ideal strategy, most comment sections still maintain the same backbone structure. This basic message structure, together with the diversity found in online newspapers’ websites and their comment sections makes them the ideal empirical object to study discursive differences in CMC induced by technical options. Any comparative study done in this framework should, however, take under consideration the possible variations in the composition of each newspaper’s publics that might be linked to editorial options and the publication’s tradition and history.

Hierarchy versus Equalization

One of the features of CMC is the absence of physical cues about the identity and status of other participants in one given interaction. This particular characteristic has led academics to theorize about the possibility of the Internet allowing for equal discursive opportunities for all, including underrepresented and/or stereotyped social groups that do not have a say in traditional discursive spaces. This hypotheses has been labelled the equalization hypothesis (Dubrovsky, Kiesler, & Sethna, 1991) and it represents one of the strongest arguments in favor of allowing anonymity on an online setting.

The absence of physical cues, on the other hand, is also one of the factors associated by Suler (2004) to online disinhibition, who calls this factor invisibility. According to Suler (2004, p. 322), this factor differentiates itself from anonymity: “Even with everyone’s identity known, the opportunity to be physically invisible amplifies the disinhibition effect. People don’t have to worry about how they look or sound when they type a message.” Of course this mitigation of status might just be an illusion when we speak about environments that allow for repeated interactions between individuals, since new identities and relations of power tend to emerge within the online sphere. Depending on the technical framework of the website, formal or informal hierarchies might arise from the equalized publics.

When we introduce the concept of hierarchy into a given system we are necessarily speaking of relations of power and authority between participants. The idea that the implementation of a formal hierarchical structure can reduce online speech aggression does not come necessarily from the concept of authority. The technical authority of moderators is present even when there is no distinction between users and, additionally, minimization of authority and status is one of the factors that cause online disinhibition (Suler, 2004). The effectiveness of hierarchies comes from the added incentive that cooperative behavior might allow one to rise through the ranks and reach the top of the influence and power pyramid (Halevy, Y. Chou, & D. Galinsky, 2011). When given the choice between deviant and cooperative behavior, users would chose to be cooperative because of the higher incentive, even if deviant behavior does not bring substantial consequences. On the other hand, users who are already climbing the hierarchical ladder would have no incentive for deviance, for they would risk losing all their reputation and accumulated capital.

The introduction of a hierarchical setting could be a viable solution for newspapers that want to allow anonymous comments, but cannot successfully moderate all published comments. It is our purpose to determine the effectiveness of these hierarchies in preventing the proliferation of aggressive and uncivil discourse.

Research design

We have now presented the main framework that supports our work proposition for this study. What we seek to observe are the differences in user behavior in a hierarchical system and an equalitarian system, where the first one offers the possibility of acquiring formal status to registered users and the second one creates a homogeneous mass of users. We will also analyze the differences between anonymity and identification in both systems, studying their effects on aggression and user investment in speech.

For the purpose of tackling these issues, we will analyze two different systems for online newspaper comment sections. The system adopted by the Portuguese newspaper Jornal de Notícias2 presents itself as an equalitarian setting: users may give their real name, adopt a pseudonym or remain anonymous without any formal implications. From a purely technical point of view, there is no practical disadvantage in remaining anonymous and every user has equal rights and opportunities. Comments are published immediately and are reviewed and removed by journalists only when they are signaled by other readers.

The second system, adopted by Portuguese general information newspaper Público3, presents itself as a hierarchical structure with power asymmetries. Firstly, there is a major gap between registered users and anonymous users: only registered users can rise through the ranks of the hierarchy and acquire technical power, however, they need to register an identity indicating their real name and email address. Once they are registered, users can rise in the hierarchy by publishing comments, answering polls, listing arguments that are upvoted in newspaper polls and signaling uncivil comments. On the other hand, users lose their rank by submitting comments that are rejected, approving comments that are later signaled and deleted and answering polls with arguments that receive low feedback. Users with a high reputation level are trusted with the task of moderating comments from other users. This simultaneously makes comment moderation manageable and offers an attractive reward for those willing to make their way up the ranks.

The comparison of user behavior in these two systems aims to verify four main hypotheses that are linked to the effects of anonymity and hierarchy in online settings, supported by the theoretical framework presented above:

H1. There are less anonymous comments in a hierarchical setting than in an equalitarian setting.

H2. There is less aggression in a hierarchical setting than in an equalitarian setting.

H3. Anonymous users are more aggressive than identified users.

H4. Identified users put more effort into their comments than anonymous users.

H1 and H2 are directly linked to the incentives offered by a hierarchical system, while H3 and H4, despite being oriented to the issue of behavioral differences related to anonymity, will also explore the behavioral differences between both systems.

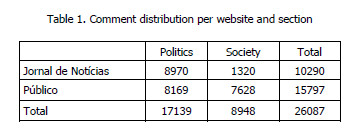

These hypotheses will be tested by comparing the contents of both newspapers’ comment sections. Their audiences are similar, although Público’s content is traditionally aimed at a universe with a slightly higher education. It should also be noted that both systems have a reply button that allows users to reply to comments from other users. We collected and analyzed all comments from the Politics and Society sections of each newspaper from 12th June 2013 to 11th July 2013, totaling 26087 comments distributed as follows:

Our analysis will exclude comments that are repeated in the same article (n=355) and SPAM/Advertising comments (n=25). The selection of a month-long period and of similar newspapers and sections seeks to minimize the impact of other factors in the comparability of both systems. For each comment, the following variables were coded: newspaper, section, aggression, author identification and word count.

The newspaper, section and word count variables are self-explanatory and were operationally defined. The presence of aggression was determined through the use of ad hominem arguments or expressions that directly or indirectly offend other individuals or groups. The use of uncivil language was also coded as a form of general aggressive behavior.

The author identification variable was divided into three categories: anonymous, pseudonym and believable name. Users who presented a name that could be their real name were classified under the last category, while the anonymous and pseudonym categories are self-explanatory. The distinction between pseudonyms and believable names was not always clear, but coders relied on their knowledge of common names to judge threshold situations and a high intercoder reliability value was achieved (α=0.801). In Jornal de Notícias, users who used the username field to give a title to their comment were also classified as anonymous. Unfortunately, the data collection method did not allow us to register the reputation level of Publico’s users, which would have been useful in order to measure the effectiveness of the hierarchy.

Krippendorff's Alpha (α) was used to measure intercoder reliability. Two students were asked to code 253 cases from our sample after receiving two hours of training. The following values for intercoder reliability were achieved:

User identification = 0.801 α

Aggression = 0.595 α

Results

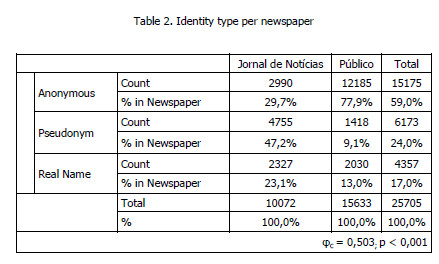

In order to test our first hypotheses, we compared the number of anonymous comments in both newspapers. The results, shown in Table 2, contradict our hypotheses and reveal that the majority (77,9%) of comments in the hierarchical system are, in fact, anonymous. On the other hand, almost half of the equalitarian system’s comments are submitted under pseudonyms. This translates to very strong relation between the type of system and commenter identification.

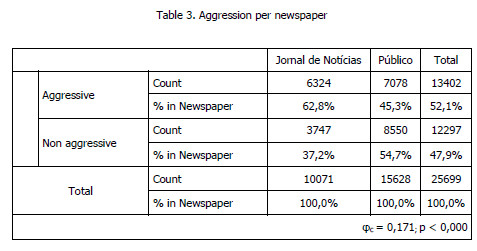

To tackle our second hypothesis, we compared the aggression rates in both newspapers. The data (Table 3) show that Público’s comments have a lower percentage of aggression than Jornal de Notícias, confirming our hypothesis. However, we must consider that Público has a pre-moderation system, where comments need to be approved by users with higher reputation before they are published. The newspaper’s comment approval rate on June and July was around 85%, and, although we do not have the approval rate for Jornal de Notícias, the 15% deleted comments may account for the reduction in aggression, showing that the hierarchical system, by itself, might not offer a strong improvement in reducing aggressive comments.

We now turn towards the effects of anonymity on aggression. First we look at the general comparison between author identification degrees and then we observe the differences between both systems.

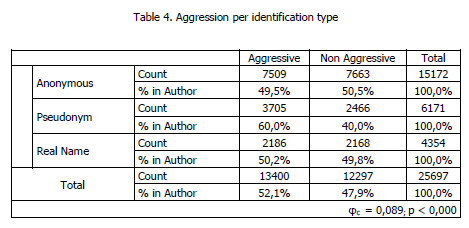

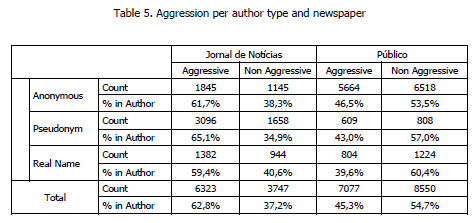

Table 4 shows that anonymity is not a relevant factor to determine aggression, although a slightly higher percentage of aggressive comments is found on users who use a pseudonym. But are there any relevant differences between the systems?

Table 5 shows that although the aggression profiles are similar, aggression in the hierarchical system declines with higher identification degrees and anonymous users are the most aggressive by a short margin.

Finally we look at the average word count in order to determine which users put more effort in their comments. Since the character limit on Público is 100 characters higher than Jornal de Notícias, we should look at both newspapers separately in order to get accurate results. A one-way ANOVA was conducted to compare the effect of author identity on the comment word count for anonymous, pseudonym and real name authors on both newspapers.

For Jornal de Notícias, there was a significant effect on the number of words commented for the three categories (F (2, 10069) = 50,21, p = 0,00). Post hoc comparisons using the Scheffe test indicated that the mean number of words for pseudonymous users (M = 43.55, SD = 36.35) was significantly lower than the real name users (M = 53.11), SD = 40.20) and slightly lower than anonymous users (M = 46.84, SD = 37.81). Although significant, the difference between the anonymous and pseudonymous users was much smaller. As expected, real name users invest more in their comments, but the difference is not so clear between pseudonymous and anonymous users, which might lead us to conclude that there is no real difference between both categories in an equalitarian setting.

In Público, we can also note a significant effect on the number of words commented for the three categories (F (2, 15630) = 191,85, p = 0,00). In this case, post hoc comparisons using the Scheffe test indicated that the mean number of words for anonymous users (M = 42.46, SD = 38.10) was significantly lower than the pseudonymous users (M = 50.18, SD = 38.62). The average word count for real name users was also higher than the other categories (M = 60.15, SD = 43.30). In this hierarchical setting, we are able to observe the predicted values, with the investment in comments, measured by the word count, increasing as identification also increases.

Discussion

What are the implications these results have to our hypothesis? H1 was completely disproved, since the hierarchical system had significantly more anonymous users than the equalitarian one. Our interpretation of these results is that the incentive of rising through the hierarchy was not enough for users to have the trouble of registering themselves in the system. This belief is supported by the fact that some users signed their comments with a pseudonym or a believable name in the comment text, although they would still appear as anonymous to the system. In this regard, it is noteworthy to mention that, one month after our sampling period, Público forbid comments from unregistered users, which reduced the total number of comments to about half.

One other factor that might account for the low number of registered users in Público is that some users do not understand how the system works. This claim finds its roots in the fact that there were many occurrences where users would blame journalists for the way they were ‘censuring’ comments, although the approval of comments is the job of high reputation users. The ability of users to understand how a system works should always be considered when studying online interaction, and online comment sections are no exception.

On the equalitarian system, almost half of the users adopted a pseudonym (47,2%). When submitting a comment, users always needed to give an email address, although this email was not displayed publicly, even when they wished to remain anonymous. This means that the choice of identity was purely a choice of self-presentation, with no other advantages or disadvantages like in the hierarchical system. Therefore, the high percentage of pseudonyms shows that users prefer to create an alternate identity online, one that gives some coherence to their comments and allows them to build a reputation, but that does not allow anyone to associate that identity to their real name.

One curious phenomenon on Jornal de Notícias was the fact that certain comments were addressed to certain users, even if those users did not comment that specific article yet. This was the case with certain frequent users whose pseudonym reached the status of comment section celebrity. After reading a certain amount of comments, one starts to realize the existence of an inner community of frequent users that interact with each other, something that is less notorious in the hierarchical system of Público. Finally it would be important to note that no significant differences were found in user identification between the Politics and Society sections.

Our second hypothesis (H2) stated that there would be less aggression in a hierarchical system than in an equalitarian system. This hypothesis was verified, but not for the reasons we initially advanced. The incentive for rising through the hierarchy is not enough to reduce aggressive behavior. This becomes clear when we see that the incentive is not enough to make most users register themselves in the system. The reason why aggression is reduced is that assigning the moderation function to users makes it manageable to pre-moderate all comments, something that is impossible to achieve with a just a handful of journalists.

However, one cannot avoid asking how is it possible to have such a high percentage of aggression when all comments are pre-moderated. On the equalitarian setting, comments were only deleted based on the reader’s initiative and this requirement allows us to understand the proliferation of aggressive discourse since most users do not bother to signal uncivil or aggressive comments. In Público, this is not the case. All published comments must be moderated by higher ranked users and these users are punished for allowing comments that break the rules. Therefore, we must assume that the flaw is in the top of the hierarchy and that these highly reputed users do not follow the rules and can still maintain their status.

The community manager of Público, Hugo Torres, explains to us that when the hierarchical system was adopted, certain users quickly grasped the way reputation levels worked and started to publish short and simple comments like ‘very good’ and ‘well done’ that, in spite of making no real contribution to the topic, allowed them to rise very quickly to the top of the pyramid. Some of these users, Hugo Torres explains, became “small independent states” of the comments section, making their own rules and approving comments as they wished and according to their own views. The problem with a hierarchical system is that once the top is biased, the whole structure suffers the effects. Therefore, a hierarchy is only effective if it is enforced correctly, and a lack of legitimacy (Halevy, Chou, & Galinsky, 2011) can account for why the hierarchical system does not prevent aggression in Público.

The results that relate aggression to identification contradict the idea that anonymous users are more aggressive than identified users (H3). This is especially true in Jornal de Notícias, where pseudonyms are the most aggressive category by a short margin. In Público, aggression percentages are lower when users have a higher degree of identification, but this relation is actually very weak (φc = 0,048). In face of these data, one can conclude that anonymity is not a determinant factor for aggression inside systems where anonymity is optional. Even in the hierarchical system of Público, where identification requires registration and offers additional benefits, the differences between anonymous and identified users where not meaningful.

These results seem to contradict what was concluded in the study by Santana (2014, p. 29): “commenting forums of newspapers that disallow anonymity show more civility than those that allow it.”. We could attribute these differences to the fact that the Portuguese and American audiences are different or to the conceptual distinction between uncivility and aggression. However, according to our view, there is an important difference that justifies the discrepancy in results: while Santana’s study compared newspapers that allow and disallow anonymity, we are comparing anonymity and identification in the same system. Therefore, it is not the self-presentation option between anonymity and identity that is correlated with aggression, but the technical definitions of the system as a whole that may condition aggressive behavior. It is not the mask that that defines the user’s behavior, but the environment where this mask is worn.

Finally, we take a look at the commitment differences between different identification degrees by looking at the word count (H4). Similarly to what happened with aggression, the results corroborate our hypothesis in Público but not in Jornal de Notícias, where pseudonym is the category with the lowest word count. It seems that registered users are less prone to aggression and invest more on their comments. However, the lower word count in pseudonyms in Jornal de Notícias, together with the higher aggression percentage should not be disregarded. In this setting, users who chose to create an alternate identity have more disinhibition and invest less, something that is in line with the distinction established by (Suler (2004)) between dissociative anonymity and dissociative imagination.

Our study concludes that the self-presentation options are not necessarily correlated with aggressive behavior, but some differences can be observed between hierarchical and equalitarian systems. Although the hierarchical system shows some potential to reduce aggression and enhance discussion quality, an implementation of this system that can be exploited by deviant users can disrupt the purpose of establishing an effective reward and promotion system. The hierarchical solution adopted by Público makes moderation manageable and further work on perfecting and adapting this system might lead to a significant improvement in the quality of discourse.

Bibliography

Barton, M. D. (2005). The future of rational-critical debate in online public spheres. Computers and Composition(22), 177-190. [ Links ]

Benson, T. W. (1996). Rhetoric, civility, and community: Political debate on computer bulletin boards. Communication Quarterly, 44(3), 359-378. doi: 10.1080/01463379609370023 [ Links ]

Blom, R., Carpenter, S., Bowe, B. J., & Lange, R. (2014). Frequent Contributors Within U.S. Newspaper Comment Forums: An Examination of Their Civility and Information Value. American Behavioral Scientist. doi: 10.1177/0002764214527094

Bon, G. L. (1947). Psychologie des Foules. Paris: Presses Universitaires de France. [ Links ]

Bourdieu, P. (1998). O Que Falar Quer Dizer. Algés: DIFEL. [ Links ]

Castells, M. (2012). Networks of Outrage and Hope. Cambridge: Polity Press. [ Links ]

Chung, D. S. (2007). Profits and Perils: Online News Producers' Perceptions of Interactivity and Uses of Interactive Features. Convergence: The International Journal of Research into New Media Technologies, 13(1), 43-61. [ Links ]

Coe, K., Kenski, K., & Rains, S. A. (2014). Online and Uncivil? Patterns and Determinants of Incivility in Newspaper Website Comments. Journal of Communication, n/a-n/a. doi: 10.1111/jcom.12104

Cybernetics, L. G. (1972). Community Memory!!! flyer. Retrieved 04-07-2014, from http://www.well.com/~szpak/cm/cmflyer.html

Dahlberg, L. (2001). The Internet and Democratic Discourse: Exploring The Prospects of Online Deliberative Forums Extending the Public Sphere. Information, Communication & Society, 4(4), 615-633. [ Links ] doi: 10.1080/13691180110097030

Dahlgren, P. (2000). The Internet and the Democratization of Civic Culture. Political Communication, 17(4), 335-340. doi: 10.1080/10584600050178933 [ Links ]

Dahlgren, P. (2006). The Internet, Public Spheres, and Political Communication: Dispersion and Deliberation. Political Communication, 22(2), 147-162. [ Links ]

Dewey, J. (1927). The Public and its Problems. New York: Holt. [ Links ]

Douglas, K. M., & McGarty, C. (2001). Identifiability and self-presentation: Computer-mediated communication and intergroup interaction. British Journal of Social Psychology, 40(3), 399-416. doi: 10.1348/014466601164894 [ Links ]

Dubrovsky, V. J., Kiesler, B. N., & Sethna, B. N. (1991). The equalization phenomenon: status effect in computer-mediated and face-to-face decision-making groups. Human–Computer Interaction, 2(2), 119-146.

Goodman, E., & Cherubini, F. (2013). Online comment moderation: emerging best practices: World Editors Forum.

Habermas, J. (1989). The Structural Transformation of the Public Sphere: An Inquiry into a category of Bourgeois Society. Cambridge: Polity. [ Links ]

Halevy, N., Chou, E. Y., & Galinsky, A. D. (2011). A functional model of hierarchy: Why, how, and when vertical differentiation enhances group performance. Organizational Psychology Review, 1(32), 32-52. doi: 10.1177/2041386610380991 [ Links ]

Halevy, N., Y. Chou, E., & D. Galinsky, A. (2011). A functional model of hierarchy: Why, how, and when vertical differentiation enhances group performance. Organizational Psychology Review, 1(1), 32-52. doi: 10.1177/2041386610380991 [ Links ]

Lapidot-Lefler, N., & Barak, A. (2012). Effects of anonymity, invisibility, and lack of eye-contact on toxic online disinhibition. Computers in Human Behavior, 28(2), 434-443. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2011.10.014 [ Links ]

Lévy, P. (2003). Ciberdemocracia. Lisboa: Instituto Piaget. [ Links ]

Lippman, W. (1997). Public Opinion. New York: Free Press Paperbacks. [ Links ]

Moore, M. J., Nakano, T., Enomoto, A., & Suda, T. (2012). Anonymity and roles associated with aggressive posts in an online forum. Computers in Human Behavior, 28(3), 861-867. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2011.12.005 [ Links ]

Papacharissi, Z. (2002). The virtual sphere: The internet as a public sphere. New Media & Society, 4(9), 9-27. [ Links ]

Ruiz, C., Domingo, D., Micó, J. L., Díaz-Noci, J., Meso, K., & Masip, P. (2011). Public Sphere 2.0? The Democratic Qualities of Citizen Debates in Online Newspapers. The International Journal of Press/Politics, 16(4), 463-487. doi: 10.1177/1940161211415849 [ Links ]

Santana, A. D. (2014). Virtuous or Vitriolic. Journalism Practice, 8(1), 18-33. doi: 10.1080/17512786.2013.813194 [ Links ]

Schuler, D. (2008). Civic intelligence and the public sphere. In M. Tovey (Ed.), COLLECTIVE INTELLIGENCE: Creating a Prosperous World at Peace (pp. 83-94). Virginia: Earth Intelligence Network. [ Links ]

Silva, M. T. d. (2013). Participação e deliberação: um estudo de caso dos comentários às notícias sobre as eleições presidenciais brasileiras. Comunicação e Sociedade, 23, 82-95. [ Links ]

Strandberg, K., & Berg, J. (2013). Online Newspapers’ Readers’ Comments - Democratic Conversation Platforms or Virtual Soapboxes? Comunicação e Sociedade, 23, 110-131.

Suler, J. (2004). The Online Disinhibition Effect. CyberPsychology & Behavior, 7(3), 321-326. [ Links ]

Tanis, M., & Postmes, T. (2007). Two faces of anonymity: Paradoxical effects of cues to identity in CMC. Computers in Human Behavior, 23(2), 955-970. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2005.08.004 [ Links ]

Zimbardo, P. G. (1969). The human choice. Individuation, reason, and order vs. deindividuation, impulse and chaos. Nebraska Symposium on Motivation (Vol. 17, pp. 237-307).

Date of submission: May 30, 2015

Date of acceptance: November 11, 2015

NOTAS

1 See as examples the websites http://thedemocracytwoexperiment.wordpress.com/action/, https://www.causes.com/ and https://petitions.whitehouse.gov/, accessed in 23-11-2014.

2 http://www.jn.pt, accessed in 23/11/2014

3 http://www.publico.pt, accessed in 23/11/2014