Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Indicators

-

Cited by SciELO

Cited by SciELO -

Access statistics

Access statistics

Related links

-

Similars in

SciELO

Similars in

SciELO

Share

Observatorio (OBS*)

On-line version ISSN 1646-5954

OBS* vol.9 no.Especial Lisboa Dec. 2015

Marginal scenes and the changing face of the urban public library: The Vancouver Downtown Eastside’s Carnegie

Paulina Mickiewicz*

*Visiting Research Fellow, Frost Centre, Trent University, Peterborough, Ontario, Canada (paulina.mickiewicz@mail.mcgill.ca)

ABSTRACT

Through an analysis of one of North America’s earliest Carnegie libraries, located in Vancouver, the aim of this article is to question increasingly antiquated discourses of the urban public library as a static cultural institution in order to ascertain how contemporary urban libraries are both representative and generative media institutions that are increasingly central to marginalized urban communities. Marginalized communities, such as those living in Vancouver’s Downtown Eastside, are often overlooked as contributing to the cultural fabric of a city. The Carnegie Library is a site in which precarious, often pre-defined publics, whose members already suffer from established forms of discrimination and exclusion, come together to form a new iteration of the scene (Straw, 2004). I will argue that marginalization, when integrated into a semi-public space and institution such as the Carnegie Community Centre, creates a generative scene that holds the potential of fostering nascent forms of both cultural and political association and education amongst marginalized groups themselves. As a result, the contemporary urban public library emerges as a responsive medium of communication in its own right that is shaped by its siting across distinct urban environments.

Keywords: libraries, marginal communities, media spaces, digital citizenship, scenes

Introduction

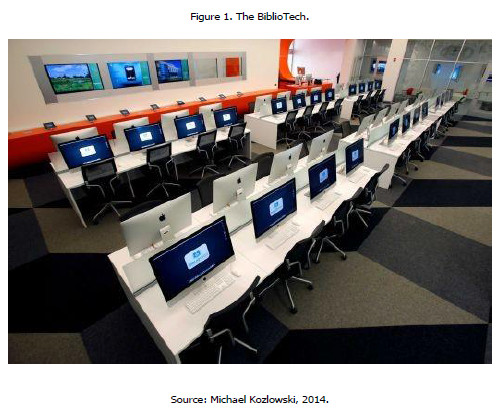

In fall 2013, the United States saw the opening of its very first bookless public library. Bexar, Texas, a sprawling county just fifteen kilometres outside of San Antonio, with a population of nearly two million people, built a 4,989 square foot futuristic looking e-library in the city’s economically depressed South Side. Not to be confused with an online portal to an existing library, this library, for some, can be seen as a confirmation of the much-feared and often talked about demise of the book. The bookless library is not an entirely new idea, as many academic and secondary school libraries in the United States have traded in books for e-readers and computers. However, the fact that Bexar County’s new BiblioTech is the first bookless public library is indeed novel. Through partnerships with e-book publishers, the BiblioTech offers approximately 10,000 titles to its patrons. The library has 100 e-readers available to its adult patrons, 50 to children, and houses 50 computer workstations, 25 laptops, and 25 tablets (Goodwin, 2013).

Patrons also have the opportunity to borrow e-reader devices for two weeks at a time. The design of this new library has been compared to an Apple Store, and renderings of the project depict it as more akin to an Internet café than an actual library (figure 1). The specific aim of the library — to bridge the digital divide between Bexar County’s wealthier residents and its lower income (primarily Latino) households — is unsurprising in the context of what has come to be known as the “information age.” More provocative, in the context of conventional ideas about what public libraries are and what they are for, is the BiblioTech’s radical booklessness. For, while we are accustomed to the idea that part of what a library does is to facilitate literacy (including digital literacy), we are perhaps still not quite ready for the idea that a library can be a library without books. In this respect, the prospect of Bexar County’s BiblioTech raises a much broader set of questions currently surrounding public libraries.

The increasingly rapid trend towards the substitution and supplementing of the book by other reading technologies is but one (albeit major) symptom of the shifting terrain upon which knowledge practices and cultural institutions meet. The library is being reinvented and reimagined, not only in its material infrastructure, both inside and outside library buildings the world over, but also in terms of its identity and purposes. The notion of “the library” inherited from past centuries has expanded considerably. The variety of roles that the contemporary library now takes on extends beyond preservation, dissemination, and access, to include providing individuals and communities with a new kind of social public space. In other words, although the preservation and dissemination of cultural memory remains central to the role of the contemporary library, the needs and interests of individual patrons have become equally, if not more, important. The book competes for space in the library not only with computers, but also with human beings.

Under the auspices of new and emergent media technologies the discourse around libraries has shifted from a modern pre-occupation with collections, pedagogy, and authoritative knowledge, towards a postmodern emphasis on interfacing, empowerment, democratization, communitarianism, and life-long learning (Hand, 2008). In his book Making digital cultures: Access, interactivity, and authenticity Martin Hand (2008) argues that,

[t]he narratives of digitization in the library shifts learning from ‘instruction’ to ‘empowerment,’ entailing an institutional move from custodialism to interfacing, and a promotion of citizen engaged in indefinite learning. In this sense, the Web (as the latest information machine) has become a powerful set of cultural discourses about the traditional purposes, functions, and effects of public libraries in contemporary information cultures (p. 10).

It is commonly argued that libraries have continued to thrive in the face of digitization and the supposed decline of books because they have, as can be seen with the example of the BiblioTech, embraced the technologies that have threatened their existence and have become spaces of free access to wireless networks that work to bridge the digital divide. However, libraries have continued to thrive, not only because they have embraced new and emergent media technologies (libraries have always done so throughout their history), but primarily because they have become new social and educational institutions for the 21st century. There is a tension that lies within this transformation as libraries struggle to hold on to an older version of themselves while simultaneously coming under pressure to fill in the gaps that other cultural and educational institutions often leave behind.

The transformation of the library is not a new phenomenon, the library has continuously reinvented itself and adapted to new cultural environments. The contemporary challenge that libraries face, to become more like something else or to step in where other institutions might be struggling or failing, is a new kind of challenge; a challenge that is specific to the library finding itself within a new digital cultural reality. Tensions surrounding old media vs. new media, copyright vs. open source, the increasing privatization and corporatization of education troubling our notions of democratic access to knowledge, precarious employment and flexible work arrangements, as well as the formations of new digital literacies, have all put an unprecedented demand on libraries not only to retain their traditional roles as preservers and disseminators of cultural memory and knowledge, but also to play a role in addressing social problems and controversies that far exceed the cataloguing, storage and retrieval of texts.

Through an analysis of one of North America’s earliest Carnegie libraries, located in Vancouver, the aim of this article is to question increasingly antiquated discourses of the urban public library as a static cultural institution in order to ascertain how contemporary urban libraries are both representative and generative media institutions that are increasingly central to marginalized urban communities. Marginalized communities, such as those living in Vancouver’s Downtown Eastside, are often overlooked as contributing to the cultural fabric of a city. The Carnegie Library is a site in which precarious, often pre-defined publics, whose members already suffer from established forms of discrimination and exclusion, come together to form a new iteration of the scene (Straw, 2004). I will argue that marginalization, when integrated into a semi-public space and institution such as the Carnegie Community Centre, makes the library into a medium of communication in itself that holds the potential of fostering nascent forms of both cultural and political association and education amongst marginalized groups in the city.

The Eastside Living Room

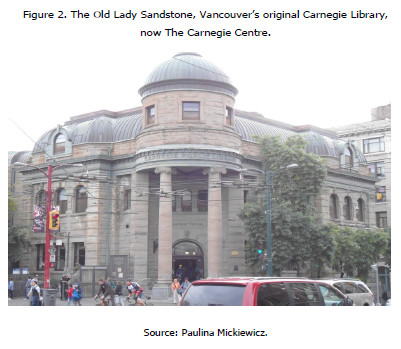

At the corner of Hastings and Main, in the heart of Vancouver’s Downtown Eastside, stands the Old Lady Sandstone, Vancouver’s original Carnegie Library (one of only three that were built in the province of British Columbia) (figure 2). The building’s cornerstone was laid in 1902, and when the library opened to the public in 1903, it shared its facilities with the Vancouver Art, Historical and Scientific Society, which opened a museum on the second floor of the building. During the early part of the 20th century, Vancouver’s Downtown Eastside was not overwhelmed as it is today with the poverty, homelessness, crime, drug addiction, and prostitution for which the neighbourhood also currently provides a home.

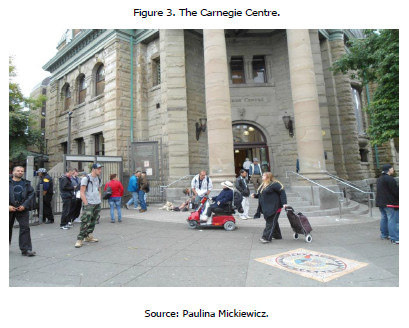

In fact, Vancouver’s Downtown Eastside was considered “the ‘old’ heart of the city” (Curry, 2007, 62) in relation to the newer up and coming West End. Over the years, as the affluent residents of the Eastside began to relocate westward following the business boom that was taking place on the other side of the city, the Downtown Eastside devolved into a neglected part of the city’s core and became a home for some of the poorest residents in Canada. The Downtown Eastside has been characterized by the rest of the city as, what Yasmin Jiwani and Mary Lynn Young have described as a degenerate zone “designed to demarcate degenerate bodies—those that society deems as being unwanted, unmissed, and ultimately disposable” (Jiwani & Young, 2006, p. 900). Only a few blocks to the northwest of Main and Hastings is the city’s oldest neighbourhood, Gastown, which is characterized by trendy fashion and interior design boutiques, as well as a hot spot for chic restaurants and tourist attractions. Gastown renders Hastings and Main all the more invisible and simultaneously exacerbates the shocking disparity that exists in such proximity between the most affluent and the poorest residents of Vancouver. What is particularly poignant about the history of this Carnegie Library is that it has become a space where those that are ‘unmissed’ and ‘unwanted’ can become visible where they may otherwise have been invisible. Indeed, in the fall of 2013, when I was standing across the street from the Carnegie Library, I was struck by how visible the library seemed to make those who took to milling about in front of it or sitting on its front steps (figure 3). The library made those without a home, with addictions, with criminal records, seem all the more “legitimate” or “credible” because they not only sought out a haven to read and to be with others, but also because the library invited them in, as it would anyone.

They became patrons and readers, that library’s public. Ann Curry (2007) writes that,

the Carnegie Library established itself as a place where all were treated with respect, no matter how poor or ill-dressed, where one could find a friendly atmosphere very different from the shabby hotel room, litter-strewn alley, or cold dumpster where patrons spent many hours alone. At the Carnegie, even patrons who had veered farthest from society’s norms were treated “like everyone else”— valued as having intelligence and a right to access information and read for pleasure (p. 72).

The Carnegie Library has established itself as “the living room of the Downtown Eastside” (The Carnegie Centre). Following a tumultuous history and a twelve-year closure, the library reopened on January 20, 1980, this time as The Carnegie Community Centre. The new Centre includes a library and reading room that is run as a special Vancouver Public Library branch, which was specially designed to accommodate the needs of the neighbourhood’s potential patrons (no proof of address is required to borrow a book at this location, for instance). Furthermore, as Curry (2007) writes: Providing a sanctuary amid the hard and unforgiving reality on the streets outside is not always easy, and the Carnegie library staff have special mettle, deeper compassion, and true grit. It is not uncommon for drug addicts and alcoholics to be using the Library facilities at the same time as senior citizens and children (p. 72).

While Curry may be extolling a compassionate librarianship that may or may not exist, it is true that its varying community services range from offering a low-cost not-for-profit kitchen to organizing theatre and dance workshops. The Carnegie Centre in partnership with the Library also has a strong educational program in place that attempts to combat the high levels of illiteracy that are common for the neigbourhood. Since it opened in the 1980s, the Centre has offered English as second language courses for new immigrants, and dedicated itself to not only addressing literacy issues but also social ones as well, offering a wide range of books and programs that deal with “poverty, addiction, housing, and mental health” (Curry, 2007, p. 73). Currently, the Carnegie’s learning centre is run by Capilano University on a volunteer basis, where patrons are offered one-on-one tutoring in reading and writing, are helped with completing high school courses, and are also offered computer training. During a recent visit to the library it was clear that this was a highly valued and essential site but still very obviously in need of more resources, not only monetary but also in terms of volunteers, who were needed to run the kitchen, the educational programs, the library, etc.

As I toured the building (figure 4) it was interesting to find that most people were in fact in the library proper (and I don’t have images of people within the library as when I asked for permission to take photographs, they asked that I avoid taking any with people in them), either reading, on the computers, napping, or chatting with the librarian, as opposed to the other spaces that they could have occupied, such as the lounge or the dining hall. The library was crowded in a comforting way; although small and cramped it was a space to which people seemed to gravitate. This could in part be explained by the fact that, as Rebecca Gray (2012) writes: “At the library, some of the people who share our city but are mostly ignored become fellow book-lovers, and it’s a great equalizer. In the rest of their lives, they are asking for help, or being told what to do; here they are just people who are welcome to take a book” (p. ix).

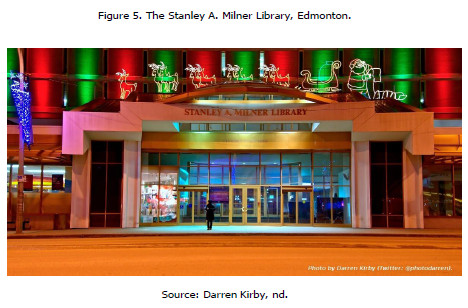

Vancouver’s Downtown Eastside public library is not the only library to have made the transition from library to hybrid community or learning resource centre (at least in Canada and the North American context). In May of 2011, the Edmonton Public Library (EPL) received a $605,402 grant from the Provincial Government in order to create a community safety and outreach program (The Edmonton Public Library, Press Release, 2011). The program operates out of the Edmonton Public Library’s Stanley A. Milner Library located in Edmonton’s downtown core (figure 5).

Whereas the old Carnegie in Vancouver was renamed a community centre, the Stanley A. Milner Library still remains first and foremost a library with a focus on offering special types of services that answer the needs of the city’s marginalized communities. The Library describes this mission as follows:

The project’s goal is to reduce the social disorder, victimization and isolation that at-risk individuals encounter. The Stanley A. Milner Library is seen as a safe daytime refuge for many Edmontonians, and the goal of this program is to empower them through literacy and social support as offered by both EPL community librarians and outreach workers working within and outside the library walls (The Edmonton Public Library, Press Release, 2011).

Before the program was created, library officials found that many troubled individuals preferred to seek refuge within the walls of the library, rather than at actual community centres or shelters. Most patrons find the anonymity of a library comforting, and it is a space within which they can find resources without feeling as though their privacy is being infringed upon. Yet those who are marginalized also feel trusted within the library, where in other contexts they might not be. Gray writes that “[I]t’s a symbol of trust that when you’re on the streets, and someone lends you a book, it builds your confidence and becomes an emotional investment” (Gray, 2012, viii). The goal is therefore to target “individuals who may not access existing social services, but will access libraries because they are safe and welcoming places” (The Edmonton Public Library, Press Release, 2011). What is particularly unique about the outreach program at the Stanley A. Milner Library is that, in addition to librarians, they have also hired outreach workers specially trained to assist people struggling with addiction, poverty, and homelessness, and pointing them to the necessary resources.

The Vancouver Carnegie and Stanley A. Milner examples highlight both an ideological and organizational shift that has taken place within the contemporary public library. There has been a significant move away from the library as a space of autonomous learning to the library as an institution now offering more formal educational programming, and increasingly, as I touched on above, a community service oriented outlook. The role of libraries in the production of human subjects was once confined to providing access to great cultural and literary works that would cultivate the intellect. Today’s urban public library is still charged with contributing to the cultivation of human subjects, but it has moved from stimulating intellects, to caring for citizens in ways that are both more pragmatic and more comprehensive. What the library today wants to improve is not only an individual’s intellectual capacity but also their quality of life by, for example, providing them with the skills necessary to survive in a digital economy and culture. Beyond this, to care for their patrons, libraries must equally be spaces where people might have the opportunity to get back on their feet, spaces to meet other people, sites where people can come together in protest or simply safe spaces to be alone but with others. These are the numerous, almost therapeutic, roles society currently needs the library to perform.

Why libraries?

In 1976, André Cossette (2009), a Québécois librarian, published a short text entitled Humanisme et bibliothèques: Essaie sur la philosophie de la bibliothéconomie (Humanism and Libraries: An Essay on the Philosophy of Librarianship). Cossette was in search of a coherent philosophy of his profession, which he claimed it had hitherto been without. He argued that librarianship was mostly oriented towards the more practical or scientific applications of the profession rather than to its philosophical raison d’être. The question that Cossette (2009) was attempting to answer within his insightful essay was: ”why libraries?”. For him, “[t]he philosophy of librarianship consists […] of research into the ends that justify the existence of libraries” (ibid., p. 5).

The contradictory reality that libraries face in being both necessary while simultaneously expendable institutions, stems from a disconnect between the social, ethical, and philosophical needs for the existence of the library and the economical and quantifiable priorities that are used today in order to assess the relevance of public institutions. What Cossette bemoaned in 1976 as the lack of a consistent philosophy of librarianship still rings true today, and might explain in part the difficulties libraries (and librarians) have in defending the library as a vital contemporary social and cultural institution. As Rory Litwin (2009) writes in the introduction to Humanism and Libraries:

Cossette’s intention was to build a foundation for the practice of librarianship that was a simple, solid and comprehensive structure, and not a mixture of diverse ideas that sound appealing but are never thought through one against another. This is not a familiar approach for American librarians. We tend to find our philosophical foundations, such as they are, in inspiring statements of ideals that become fuzzy when inspected closely or juxtaposed, but find them useful enough to keep us going. We are generally not concerned with their logical connections or lack of connections (p. viii).

Indeed, the role of the library and of librarians, as well as their place in society at large, is almost always and unanimously described in idealistic and honourable terms. The description of the Carnegie Library in Vancouver that I put forward above, attests to this. Libraries are the pillars of democracy, they are ”centers of applied technological innovation” and ”key sites in the creation and transmission of knowledge” (Winter, 1994, p. 118). Libraries are free; they provide access to knowledge for everyone irrespective of their social, cultural, or economic backgrounds. Libraries are inclusive; they offer services for those with disabilities, for those who are unemployed, for those who are homeless, and so on. Librarians are similarly described as ”innovators, activists, and pioneers” (Johnson, 2010, p. 7), they are facilitators, educators, social workers, they fight censorship, and protect patron privacy. These somewhat romanticized, so easily ironized iterations of what libraries and librarians are or mean to society have become all the more prevalent as the need for libraries in an increasingly digital cultural reality has been called into question. The point here is not to claim that all the above characterizations are false or that they are even exaggerations, for the most part they are in fact relatively accurate descriptions of what libraries and librarians are, or at least what they strive to be. Strung together, however, the above descriptions do not necessarily form a cohesive philosophy of libraries, or librarianship for that matter. They are, as Litwin aptly points out, ”fuzzy” ideals at best which, although essential, make it difficult to form a strong argument about what the library is and why it should be protected. Furthermore, if the definition of the public library is ambiguous (and perhaps this has been helpful to its transformative abilities, and, by extension, survival over the course of its history), so too is the line by which it is measured. In other words, it is then very difficult to say when the public library has stopped being a library and has become a different cultural institution altogether.

As in 1976, the library today is still considered to be a secondary or supplemental institution to the university, school, or college, and its reason for being is increasingly embedded in the language of ‘service’ to the public. At present, this secondary role seems also to extend to other institutions such as community, career placement, and language centres, with an increasing number of library programs offering similar types of extended learning curricula. In Libraries and Identity, Joacim Hansson (2010) writes that this organizational shift seen taking place within libraries is due to ”the new economised ideology which tends to formulate public endeavours and institutions in the same economic terms as private enterprises” (p. 40). A library’s future has become dependent on whether or not the services that it offers can in some way be measured and quantified. This is of course an extremely problematic way of considering an institution such as the public library which has garnered public trust because it ”constitute[s] a non-regulated sphere around citizens for them to be able to create meaning in their lives” (ibid. p. 40). Yet it could in part explain why libraries have moved away from offering patrons an informal educational space to providing more formal educational services alongside varying types of social support, which are on some level being sold and advertised to the public in the language of empowerment, access, and freedom. As Hansson writes: ”By attaching librarianship to the educational sector user needs are much easier to define and it thus becomes easier to put an adequate price tag on library activities” (ibid. p. 41). This is not to say that the new kinds of services and support that are seen offered at Vancouver’s Carnegie Library, amongst others, are not worthwhile, progressive, and even necessary endeavours, only that there seems to be a mutually enabling dynamic between contemporary notions of literacy and education and the future of public libraries in general.

More specifically, the question would appear to be whether the library’s traditional role as a support for radically democratic self-education can withstand its repositioning as a location for the provision of educational services that are more socially and pedagogically purposeful. There is no doubt that libraries are much more instructional in their approach to learning than they once were, yet the question worth asking is what kind of education is the contemporary library offering? Due to their accelerated privatization, institutions of higher education have become increasingly inaccessible (particularly within the North American context), even to those within the middle class. This has created a need for alternative spaces of learning. As other institutions of knowledge collapse, the contemporary library is picking-up the burden (Tattoni, pers. comm., July 14, 2011). In this context, the public library could be viewed as having become ”the working man’s university” (Prentice, 2011, p. 4). The contemporary library is not offering the traditional, formal education of the university, but rather a more hands on, practical and professional education, the teaching of skills, that of late seem to be in higher demand than a more conventional post-secondary education. New and emergent media technologies have created a need for more instructional learning. In the past, patrons did not visit the library with the assumption that they would be taught how to read; rather they were offered a space in which they could access the tools that would facilitate their literacy. Today the library is faced with new forms of literacy, most notably digital literacy. It is no longer a space that merely facilitates literacy, one that offers the tools for engagement with the digital, for instance, but also a site in which literacy (primarily digital) is taught. Digital literacy has come to be understood within the space of the library as a way of combatting societal ills and a tool for promoting equality. The library, once a central institution for promoting old-fashioned bookish literacy, is now at the forefront of new forms of digital and technological literacy, and these new forms of digital literacy, are often understood in quite a broad sense.

In a sense then, libraries are doing what they have always done, they are providing access to information that will hopefully produce a more active citizen. Information literacy understood in this way is within the range of what libraries have always taught people, whether it was a matter of teaching patrons how to use an index or catalogue, or how to differentiate between reference books and other sorts of volumes, for instance. In the contemporary media environment, ‘information literacy’ programming could then be considered access to the necessary ‘tools’ that are required in order to provide people with the possibility of teaching themselves. Yet, information literacy programming, is not the only kind of educational programming being offered and promoted by libraries. With the development of more official educational programming, libraries are not only offering a space of teaching of the neutral sort of skills that allow for self-education. The contemporary public library is not only offering a space of the neutral kind of teaching that might allow people to learn how to learn. On the contrary, the more important issue is a broader range of educational programming that public libraries are now taking on as service points. It is the emerging pressures of ‘need’ and ‘service’ that libraries, such as Vancouver’s Carnegie Library, are facing and responding to, that are becoming even more crucial aspects of library programming than information literacy. It is these sorts of civic education and social work that are taking public libraries well beyond their traditional roles as places where people can come to learn by engaging with texts in a more or less self- directed way, and signals the real change in the status and role of the public library. In the spirit of Cossette’s (2009) argumentation then, it could be concluded that libraries are no longer neutral (perhaps they never truly were) when it comes to what and how people learn, they are no longer only ”liberalism in operation” (p. 57), but possibly (inadvertently) promoting a specific kind of (digital) cultural citizenship.

Constructing the “third place”

The Vancouver Carnegie’s pivotal role in the lives of the marginalized communities that have made it both their metaphorical and literal “living room” attests to the aforementioned changing face of the library’s mission within society. However, it equally points to the importance of where in a city a library is situated and how the ‘siting’ of a library can affect the kind of public space that it becomes. Over the past several decades, there have been two general trends that have stood out within library development when it comes to decisions about its placement. The first being that, on some level, as Shannon Mattern (2007) has argued, “[p]ublic libraries have always been businesses, taking on commercial functions and forms, and they have always played important roles in civic culture and urban revitalization efforts” (p. 1). This is not to say that the civic and democratic nature of the public library has somehow been lost, only that the politics surrounding the construction of new downtown public libraries have often had to do with regenerating a section of a city’s downtown core that has lost some of its commercial and cultural appeal. As Norma Rantisi and Deborah Leslie (2006) write: “New governance regimes have embraced the view of a city as a space of consumption and creativity, and have set out as their objective an interurban competitive strategy based on the marketing of their locales as distinctive destinations for work and play” (p. 365). These kinds of strategies can be seen taking place in most major cities in the world, especially with regards to libraries. The commissioning of high profile architects such as Moshe Safdie and Rem Koolhaas to design modern, ambitious, and daring new architectural library forms, exemplified by the Vancouver and Seattle public libraries, respectively, is one of the ways large metropoles have sought to put themselves on the international map. For Rantisi and Leslie (2006), these types of library projects perfectly exemplify what they call the “hard branding” of a site, “i.e. an altering of a physical site and the symbolic attributes of a place to create a unique tourist experience” (p. 366). They explain that,

Hard branding introduces order, certainty and coherence into an unruly urban landscape, making it easier to ‘read’. Governments will often appropriate star architects, designers or literary figures in the construction of a signature brand for a ‘city’ […] In this process there is a fetishization of the individual designer and a privileging of the building’s status as architectural monument over its functional use value (p. 366).

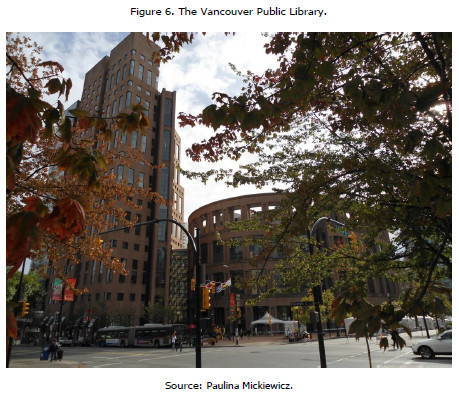

There are numerous examples of this kind of hard branding happening in cities all over the world, from Frank Gehry’s Dancing House in Prague to Will Alsop’s Sharp Centre for Design at the Ontario College of Art and Design in Toronto. What is interesting in the case of the history of the Vancouver Carnegie is that it too was built in the city’s downtown core, the Eastside once serving as Vancouver’s central commercial district (figure 6). At the time, the purpose behind its construction would not be considered as a hard branding tactic, however once the Eastside’s affluent residents began to move westward, the Carnegie, once considered Vancouver’s downtown public library, was replaced with another Central Library for the city, Moshe Safdie’s creation which opened in 1995, and which is currently located on West Georgia Street in Vancouver’s west end. Safdie’s version of the Vancouver Public Library could indeed be construed as fitting into Rantisi and Leslie’s idea/model of the hard branding of a site, but paradoxically, it is the Carnegie, left in what can now be considered the unruly and poverty-stricken downtown Eastside, that can be deemed the institution that has brought attempts at cohesion and stability to an otherwise volatile and unpredictable neighbourhood. And rather than trying to influence any kind of transformation on the demographic of its patrons, the Carnegie has allowed itself to be shaped by the community that has made a home of its walls.

In a sense, although not a new and improved or dazzling architectural statement in the city, the Carnegie is also representative of the second trend that has made itself apparent within the contemporary library context: the reimagination or rebranding of the library itself.

Not only have new library projects been considered possibly revitalizing forces for somewhat run down urban districts, but building innovative and architecturally impressive downtown public libraries has also been considered a form of revitalization for the institution of the library itself. Moreover, with major cities under pressure to centralize their library services in the face of costly decentralized systems, libraries have also been trying to transform their own image. Similarly to the branding strategies taken up by cities, libraries are also trying to brand themselves in new ways. They too are looking to become “distinctive destinations for work and play” (Rantisi & Leslie, 2006, p. 365). Mattern (2007) writes that

contemporary libraries have made various programmatic and spatial changes in order to assert their continued relevance in a new age. Yes, we have ever-spreading suburbs, edge cities, and “exurbs”; we are indeed becoming more decentralized in our living patterns, our communication, our consumption, and so forth. But just as many sociologists, geographers, historians, and political scientists have acknowledged the continued, perhaps increased, importance of “place” in global economies, networks of information and library systems have retained a “center,” too. There is a continued need for some centralized services, for hubs, in decentralized systems. Downtown libraries serve as hubs for their systems of branches. They provide a backbone for decentralized information systems (p. ix).

The branding of a library has required not only the transformation of its facade, but a transformation of its interior elements as well. The interior space of the library has needed to shift from being solely a space of knowledge, to one that combines knowledge with education, sociability, and recreation. The library has needed to become a space for citizens as much as it has needed to remain one for books. Some scholars have argued that the library has needed to become akin to what Ray Oldenburg (1997) has termed the “third place.”

In his book The Great Good Place: Cafés, Coffee Shops, Bookstores, Bars, Hair Salons, and Other Hangouts at the Heart of a Community, Oldenburg (1997) introduces the notion of “third place.” Reminiscent of Edward Soja’s (1996) assessment of Thirdspace, which Soja claims “is a purposefully tentative and flexible term that attempts to capture what is actually a constantly shifting and changing milieu of ideas, events, appearances, and meanings” (p. 2), and also in line with Jürgen Habermas’ (1989) theories of the public sphere wherein rational, critical, and un-coerced opinion-making and debate can occur, Oldenburg defines the “third place” as that place that exists between the work place and the space of the home. For Oldenburg (1997), the third place is not only about escaping from the everyday realities of the spaces of the home and the work place. One of the more important aspects of third places is the differences that they make apparent to us when compared to the habitual places within which we normally reside and work. He writes that “[t]he raison d’être of third place rests upon its differences from the other settings of daily life and can best be understood by comparison with them” (ibid., p. 22). Focusing on various examples of how third places have evolved in Europe and the United States over time, such as the German-American lager beer garden, the French bistro, and the main street of small town America, Oldenburg argues that Americans, in particular, have lost their sense of community as the social functions of informal public gathering places have lost their importance. This phenomenon is primarily the result of decentralization (the move to the suburbs, for example) and the transformation of our urban landscapes into mainly spaces of work and consumerism, leaving little room for spaces of leisure. According to Oldenburg:

The examples set by societies that have solved the problem of place and those set by the small towns and vital neighborhoods of our past suggest that daily life, in order to be relaxed and fulfilling, must find its balance in three realms of experience. One is domestic, a second is gainful or productive, and the third is inclusively sociable, offering both the basis of community and the celebration of it (ibid., p. 14).

Oldenburg identifies various characteristics for his definition of the “third place.” For him, third places should be those places that allow people to come and go as they please, they should be inclusive, accessible, playful, and the main activity should be conversation. His list of potential “third places” includes cafés, pubs, diners, hair salons, and bookstores, but somewhat surprisingly excludes libraries. In their article “Seattle Public Library as Place: Reconceptualizing Space, Community, and Information at the Central Library,” authors Fisher, Saxton, Edwards and Mai (2007) argue that while the space of the library (in their example, the Seattle Public Library) “does not support [all of Oldenburg’s] third place propositions […] it is consistent with other third place characteristics that Oldenburg notes, as offering such personal benefits as novelty, perspective, spiritual tonic, and friendship via its collection, staff, services, and clientele” (p. 152).1 Although Oldenburg omits libraries, most likely because conversation, recreation, and forms of play have always been at odds with traditional perceptions of what appropriate behaviour within these institutions should be, it could be argued that with cities engaging in novel efforts to revitalize informal public leisure spaces, newly designed libraries are incorporating Oldenburg’s functions of the third place more and more. Furthermore, the space of the public library, unlike Oldenburg’s other third places, has no direct monetary cost to visitors, making it that much more accessible and inclusive as a place. However, for Oldenburg the loss of the third place, at least in the United States, has a great deal to do with location, or rather “dislocation,” in the sense that as Americans have moved further and further away from downtown, and as a result away from the pleasant café or lively pub, they have by necessity had to expand their homes into spaces of leisure (home entertainment systems might come to mind). They have “dislocated” themselves from those places where they might otherwise go to relax. Consequently, in order for the public library to potentially become a contemporary third place, its siting cannot be arbitrary; access, proximity, and neighbourhood are all central in establishing whether the library could in fact function as a third place.

In the case of Vancouver’s Carnegie, it could be argued that it not only functions as Oldenburg’s third place, providing the Eastside’s community with a central space to socialize and unwind, but it simulatenously acts as their first and second places of home and/or work, as the majority of Carnegie’s patrons have neither. In this sense, the Carnegie can be seen as an institution that straddles various (precarious) spatial boundaries. It acts simultaneously as a space of home, work, and leisure for the Eastside’s low-income residents, yet it is also offers services to all members of the community, meaning that the Carnegie is where people considered to be living on opposite sides of an (economic) boundary often come together. It is where those who read might come into contact with those who do not, where those who have homes might witness those who do not. On a more symbolic level, the Carnegie is simultaneously representative of its neighbourhood’s past, present, and future. The library’s architectural properties allude to what could be considered the institution’s and more generally the Eastside’s golden age of commercial expansion and development. Furthermore, its educational role within the city as well as its accessibility as a sanctuary or safe space for those who may find themselves on the margins of society, are representative of its present role within the community. Finally, the tensions that come with being “on the border of things,” with straddling several borders at once, points to both the present and future situation that libraries more broadly are facing as institutions that are not only harbingers of books, memory and culture, but equally spaces in which basic human needs are being reflected in their modes of spatial organization and to some extent answered in their newfound spatial arrangements.

“The Community Garage”

Libraries are not only popping up within urban margins but are also being re-appropriated by those who feel marginalized. Individuals are constantly transforming and re-appropriating public spaces, often regardless of the kinds of uses those spaces were originally conceived for. Marginalized communities, such as those living in Vancouver’s Downtown Eastside, are often overlooked as not contributing to the cultural fabric of a city. Libraries are sites in which precarious publics, whose members already suffer from established forms of discrimination and exclusion, come together to form a new iteration of what Will Straw (2004) has coined as the scene. Straw writes that:

Scenes take shape, much of the time, on the edges of cultural institutions which can only partially absorb and channel the clusters of expressive energy which form within urban life. Just as they draw upon surpluses of people, scenes may be seen as ways of “processing” the abundance of artifacts and spaces which sediment within cities over time (ibid., p. 416).

These marginal scenes offer novel institutional possibilities for what libraries mean and what and whom they are for in the contemporary city. Marginalization, when integrated into a semi-public space and institution such as the library, creates a generative scene that holds the potential of fostering nascent forms of both cultural and political association and education amongst marginalized groups themselves. They are a scene with a particular set of knowledge practices that the library shapes and is actively shaped by. As such, marginal scenes can serve to situate knowledge regimes, both self-produced from below and administered from above, that are both responsive to and generative of new institutional iterations of the urban public library, as the cases of Vancouver and Edmonton bring to light.

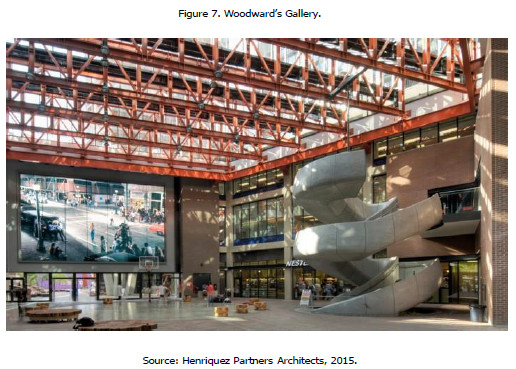

The Carnegie Library in Vancouver’s downtown Eastside is a fascinating example of a media institution that has allowed itself to be shaped by its patrons, although these patrons do not necessarily fit into the traditional mold of whom library patrons are expected to be. For the past 20 years, the Downtown Eastside has been the site of major redevelopments. One of the most significant revitalization efforts in the neighbourhood can be seen in the Woodward’s redevelopment. Located just three blocks west of the Carnegie Library, what was once known as Woodward’s Department Store, and considered the heart of Vancouver’s shopping district, is now “a mix of 536 market and 200 non-market housing units, anchor food and drugstore, retail, urban green space, a public plaza, federal and civic offices, a daycare, and a new addition to the Simon Fraser University downtown campus: the School for Contemporary Arts” (Henriquez Partners Architects). Woodward’s became subject to a redevelopment effort following its bankruptcy in 1993. Subsequent to its decline the building was destined to become a space of gentrified private housing, but after a week’s squatting in the building by a small group of community activists in 2002, who saw the space as an opportunity to offer social housing to the community that surrounded it, the building was eventually purchased by the provincial government and later resold to the city of Vancouver. The building became a major site of public consultation that eventually led to the Woodward’s that exists today. The new Woodward’s featured in the image below (figure 7), can, similarly to the Carnegie, be considered a new kind of social space, a new kind of media space. Woodward’s is considered to be a city within the city, or a media city within the city. It is a space that is meant to reflect the marginal scenes that inhabit the streets around it by recognizing these scenes as part of the cultural fabric of the city of Vancouver. Rather than taking a space like Woodward’s and gentrifying it by pushing away the community that surrounds it, it has embraced the cultural, political, and self-produced knowledge regimes that have made the Downtown Eastside their home. In this sense, spaces such as Woodward’s and the Carnegie can be considered as alternative and contested media spaces that give new meaning to the ways in which these sites are not only produced but also re-appropriated by marginal communities.

Conclusion

It is undeniable that the contemporary library is becoming something other, and something more, than either a preserver and disseminator of cultural heritage and knowledge or a renovated space for reading. The library is no longer a site in which knowledge is preserved, disseminated, and reproduced, but also a space where culture and knowledge together are generated (Basu & Macdonald, 2007). The contemporary library might better be understood as not only a container in which we store the cultural artifacts that are made outside of its walls, but one from which culture is born. For some scholars, the library as a source of culture, as an institution where culture begins, also extends to possibly imagining the library as a foundation for future technological innovation. In Designing Culture: The Technological Imagination at Work, Anne Balsamo (2011) contends that the contemporary library has the potential to become a new “institutional form,” a site in which technologies, relationships, and physical communities not only come together but can also be made (pp. 180–181). The interaction between human and non-human actors has reshaped traditional conceptions of the library as a public space. People, things, concepts and technologies all come together to make up a whole that is constantly being reassembled or remade (Latour, 2005). As a result, according to Balsamo (2011), the contemporary library’s cultural and educational work could be extended to what might better be understood as “the community garage” or the “tinkering shop” (p. 180). In this way, the contemporary library could be seen as a communication medium in itself, one that not only contributes to our networked cities but embodies them as well, while simultaneously taking in those that find themselves outside of them or that seek refuge from them. Media — telegraph, radio, TV, Internet and I would argue that libraries, as converging media, could be included in this list as well — are propelled by, and absorb, materialize, and reflect the hopes and anxieties of their age, which are more often than not democratic hopes and anxieties.

References

Anand, A., Cleeves, A., Rai, B., Bathurst, B., Moran, C., Miéville, C. & Smith, Z. (2012). The library book. London: Profile Books. [ Links ]

Balsamo, A. (2011). Designing culture: The technological imagination at work. Durham: Duke University Press. [ Links ]

Cossette, A. (2009). Humanism and libraries: An essay on the philosophy of librarianship. (R. Litwin, Trans.). Duluth, MN: Library Juice Press.

Curry, A. (2007). A Grand Old Sandstone Lady: Vancouver’s Carnegie Library. In J.E. Buschman & G. Leckie (Eds.), The library as place (pp. 61–76). Westport, CT: Libraries Unlimited.

Fisher, K., Saxton, M., Edwards, P., & Mai, J. (2007). Seattle Public Library as place: Reconceptualizng space, community, and information at the Central Library. In J. Buschman & G. Leckie (Eds.), The library as place (pp. 135–160). Westport, Connecticut: Libraries Unlimited.

Goodwin, A. (2013, January 18). America’s first bookless library coming soon to Texas. Inhabitat. Retrieved from http://inhabitat.com/americas-first-bookless-library-coming-soon-to-texas/

Hand, M. (2008). Making digital cultures: Access, interactivity, and authenticity. Hampshire, UK: Ashgate. [ Links ]

Hansson, J. (2010). Libraries and identity: The role of institutional self-image and identity in the emergence of new types of library. Oxford: Chandos. [ Links ]

Henriquez Partners Architects. (2015). Woodwards redevelopment. Retrieved from: http://henriquezpartners.com/work/woodwards-redevelopment/

Jiwani, Y., & Young, M.L. (2006). Missing and murdered women: Reproducing marginality in news discourse, Canadian Journal of Communication 31(4), 895–917.

Johnson, M. (2010). This book is overdue! How librarians and cybrarians can save us all. New York: Harper Collins. [ Links ]

Kirby, D. (no date). Stanley A. Milner Library. LibraryThing. Retrieved from: https://www.librarything.com/pic/3839652

Kozlowski, M. (2014). BiblioTech digital library opens in Texas. GoodeReader. Retrieved from: http://goodereader.com/blog/digital-library-news/bibliotech-digital-library-opens-in-texas.

Latour, B. (2005). Reassembling the social: An introduction to actor-network-theory. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

Macdonald, S., & Basu, P. (Eds.) (2007). Exhibition experiments. Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishing. [ Links ]

Mattern, S. (2007). The new downtown library: Designing with communities. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press. [ Links ]

Oldenburg, R. (1997). The great good pace: Cafés, coffee shops, bookstores, bars, hair salons, and other hangouts at the heart of a community. New York: Marlowe & Co. [ Links ]

Prentice, A. (2011). Public libraries in the 21st century. Santa Barbara: Libraries Unlimited. [ Links ]

Rantisi, N. & Leslie, D. (2006). Branding the design metropole: The case of Montréal, Canada. In Area 38(4), 364–376.

Soja, E. (1996). Thirdspace: Journeys to Los Angeles and other real-and-imagined places. Cambridge: Blackwell. [ Links ]

Straw, W. (2004). Cultural scenes. Loisir et société / Society and Leisure, 27(2), 411–422.

Tattoni, J. (2011). Personal communication, July 14, 2011.

Winter, M.F. (1994). Umberto Eco on Libraries: A Discussion of ‘De Bibliotheca’. The Library Quarterly, 64(2), 117–129.

NOTES

1 In their article, Fisher, Saxton, Edwards and Mai (2007), point to certain Third Place characteristics that the Seattle Public Library in particular does not necessarily share. For instance, although conversation as a main activity is a feature of Third Places, this is not a primary activity withinthe Seattle Public Library per se, nor is it a place that would necessarily be described as playful; in fact patrons often emphasize the serious quality of the kind of learning that takes place within the library. Nor is the physical building itself understated as most Third Place structures are or should be. Rem Koolhaas, the architect who designed the Seattle Public Library, built it precisely in order to make an architectural statement within the city. These are several reasons for which Fisher et al. do not necessarily support all of Oldenburg’s third place propositions, at least in the case of the Seattle Public Library.