Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Indicators

-

Cited by SciELO

Cited by SciELO -

Access statistics

Access statistics

Related links

-

Similars in

SciELO

Similars in

SciELO

Share

Observatorio (OBS*)

On-line version ISSN 1646-5954

OBS* vol.9 no.Especial Lisboa Dec. 2015

Of time and the city: Urban rephotography and the memory of war

László Munteán*

* Assistant professor, Department of Literary and Cultural Studies, Radboud University Nijmegen, the Netherlands (l.muntean@let.ru.nl)

ABSTRACT

The increasing public interest in the urban past has recently gained expression in a new genre of photography which consists of an old photograph superimposed over a new one in such a way as to capture exactly the same physical setting at a later point in time. The trend is called rephotography and it finds its roots in geographical surveys designed to show changes in an environment. With easy access to image editing software rephotography enjoys great popularity on a wide array of Internet sites. It has the capacity to invest the most mundane locations with a ghostly aura as we recognize corresponding objects in the new photo as evidence of the event shown in the old photo. My goal in this article is twofold. First, I will put forward the notion of indexicality as a performance, rather than merely an ontological quality, to account for these images’ appeal as traces of the past, despite their obvious use of digital manipulation. Second, through two case studies of war-torn cities, Jo Teeuwisse’s rephotography of Cherbourg and Peter Macdiarmid’s project on Arras, I will examine techniques of superimposition and the affective engagements with the urban past that they generate. Finally, I will explore rephotography’s close kinship with the StreetMuseum, an augmented reality application, which matches historic photographs of London with present-day locations providing an embodied experience of the temporal layers of the city.

Keywords: affect, indexicality, materiality, rephotography, time-bridges.

Introduction

The advance of digital technology over the past decades has offered radically new ways to navigate our physical environment. Easy access to online GPS services has not only minimized our chances of getting lost but also increased our dependence on these services in our everyday life. We use our smart phones to gain information about the opening hours of offices, restaurants and shops thereby making efficient use of our time. Social media plays a similarly crucial role in mobilizing crowds, granting visibility to communities, and instigating a variety of social and political changes. The virtual, in other words, is no longer a realm existing alongside the material but, as the affordances of new media and digital technology reveal, the two have become inextricably enmeshed.

Cities provide a particularly fertile environment for the convergence of the material and the digital. As multilayered economic, political, and cultural centers, cities are simultaneously material and digital. In this article I am interested in the way in which digital technology is used to unravel invisible layers of the urban past. In particular, I am interested in an increasingly popular trend of photography that has been burgeoning on the Internet over the past decade. Known as rephotography,1 this trend entails the superimposition of an old photograph onto a new one in such a way that both would show the exact same location at different times. Although natural landscapes often appear in rephotography projects (especially in those inspired by tourist photography), urban locations are more frequently featured. Streets, buildings, and furniture, though less persistent than mountains, fields, and rivers, hold a particular appeal as objects that have played important roles in the lives of people captured by the camera. Buildings, in particular, are integral parts of urban landscapes that serve both as architectural reference points and surfaces for the inscription of individual and collective identities and memories (Bachelard, 1994; Lakoff, 2001; Leach, 2006). Urban rephotography projects have the potential to highlight the persistence of buildings that outlast generations of inhabitants as well as to reveal their vulnerability to enemy bombardment or the wrecking ball of urban renewal. They compel viewers to scrutinize details that have weathered the storms of time and contend with the changes that have taken place between the two time-layers.

With anniversary celebrations of World War I and World War II in full swing cities that had experienced battle and bombardment have become favored sites of rephotography projects. Some rephotographers digitally blur the edge between the old and the new photographs, while others accentuate the borders and disclose imperfections in alignment. Such different techniques trigger diverse engagements with the urban past. However, regardless of the techniques they feature, these projects find their appeal in their reality-effect. Paradoxically, even if we know that the images have been digitally doctored, the superimposed images reinforce each other’s quality as indexical traces of the past. I will problematize this paradox by formulating the indexicality at work in rephotography as a performative, rather than an ontological quality. Then, through the lens of two case studies, one on Cherbourg in World War II and another on Arras in World War I, I will explore how different techniques of digital superimposition cater to different affective engagements with the materiality of urban space.

Indexicality

The popularity of rephotography is symptomatic of the use of digital technology to engage with and represent space as temporally layered. To experience the layered temporality of space it is necessary for the viewer to recognize both photographic layers as material traces of the past. In light of the heated debates about indexicality (Kember, 1998; Green & Lowry, 2003; Gunning, 2004; Elkins, 2007; Lister, 2008; Batchen, 2009; Gunthert, 2010) rephotography’s juxtaposition of analogue and digital images raises the question as to how such superimpositions affect the indexical quality of photographs. While the superimposition of images has been possible ever since the inception of photography, this kind of layering is the central “affordance” of digital editing softwares at the disposal of the rephotographer. Image production in Photoshop is conceived (and operationalized) in terms of producing images as “layers” that, in turn, jeopardize the indexicality of a single photographic image by undermining its original material space-time connection. In what follows, however, I will demonstrate that, rather than merely an indicator of the photograph as a material trace, indexicality is at once a performative gesture of pointing, which plays a crucial role in our affective response to rephotography projects.

The nature of the relationship between the photographic image and its referent is described, in semiotic terms, as indexical. In his theory of signs Charles Sanders Peirce (1965) defines indexicality as follows: “If the Sign be an Index, we may think of it as a fragment torn away from the Object, the two in their existence being one whole or a part of such whole” (p. 2.230). In photographic terms this existential relationship between the indexical sign and its object translates into the material connectivity between the photograph and its referent. Viewed as an indexical sign of reality, the photograph has been conventionally recognized as evidence. In his essay “Rhetoric of the Image” Roland Barthes (1991) articulates the same quality of the photographic image when he talks about an “analogical perfection” (p. 17) that exists between the photograph and its referent. “The type of consciousness the photograph involves,” Barthes writes later, “is indeed truly unprecedented, since it establishes not a consciousness of the being-there of the thing (which any copy could provoke) but an awareness of its having been there. What we have is a new space-time category: spatial immediacy and temporal anteriority, the photograph being an illogical conjunction between the here-now and the there-then” (p. 44). This realization is brought to a phenomenological level in his seminal work entitled Camera Lucida. “The photograph,” Barthes (1993) contends, “is literally an emanation of the referent. From a real body, which was there, proceed radiations which ultimately touch me, who am here; the duration of the transmission is insignificant; the photograph of the missing being, as Sontag says, will touch me like the delayed rays of a star” (p. 80). Although Barthes’ use of the word “touch” harkens back to the Peircean concept of the indexical sign, it also adds a personal touch to his argument, which he sustains throughout the whole book. Photography, he writes, is a “carnal medium, a skin I share” (p. 80). In other words, the photograph is a physical interface which literally brings the “touch” of the past to the present. This material connection is, however, paradoxical, for what is present in the form of the photograph is always already absent in real life. Barthes articulates this innate paradox in a language that abounds in words denoting affective states. Touch, in this sense, signifies affect no less than it denotes immediacy.

The affective dimension of perceiving the indexical power of the photograph comes to the fore most lucidly in Barthes’ formulation of the punctum, which he conceives of as a particular detail in a photo, an “accident which pricks me (but also bruises me, is poignant to me).” The punctum is the counterpoint of what he calls the studium, which he regards as a mode of processing the information inferred from the photograph. “It is by studium that I am interested in so many photographs, whether I receive them as political testimony or enjoy them as good historical scenes: for it is culturally (this connotation is present in studium) that I participate in the figures, the faces, the gestures, the settings, the actions (1991, p. 26). While the studium is anchored onto the cultural context and works at the level of connotation, the punctum cannot be reduced to semiotic codes (Jay, 1993, pp. 452–453). It can be a physical detail that captivates the viewer but what interests Barthes even more is that the punctum can also manifest itself in the temporality of the photographic image. What is depicted in it also gestures toward a future that, from the viewer’s standpoint, has already happened (Barthes, 1991, p. 96). Barthes illustrates this paradox through Alexander Gardner’s 1865 photo of a young man sitting in shackles and awaiting his execution:

The photograph is handsome, as is the boy: that is the studium. But the punctum is: he is going to die. I read at the same time: This will be and this has been; I observe with horror an anterior future of which death is the stake. By giving me the absolute past of the pose (aorist), the photograph tells me death in the future. What pricks me is the discovery of this equivalence. (p. 96)

The punctum here is what Barthes calls the “anterior future” (p. 96), a phenomenologically upgraded version of the space-time relations he developed in his essay “Rhetoric of the Image.” Anterior future implies the viewer’s awareness of a past that is only yet to come in the photograph. It marks a liminal temporality located between what “will be” and what “has been”. The juxtaposition of these two temporal realms “bruises” the beholder once the photograph is recognized as a physical imprint of what is no longer there.

If the photograph served Barthes as a material interface between the past and the present and convinced André Bazin (1960) that in it “we are forced to accept as real the existence of the object reproduced” (p. 8), one may argue that the electronic, rather than chemical, operation of digital photography undercuts claims about the indexical power of photography. Emphasizing the ontological difference between the analogue and the digital, William J. Mitchell (1992) saw digital photography as the harbinger of a “post-photographic” era. Indexicality, according to such claims, is the ontological quality of analogue photography, no longer sustained in the digital era. André Gunthert (2010) nuances Mitchell’s ontological distinction between digital and analogue photography, by identifying a “remarkable continuity of form and practice, despite a considerable technological leap… Although all our images are now made up of pixels,” Gunthert argues, “we continue to open our newspapers, switch on our televisions and trust the information they provide us. We continue to photograph our children or our holidays, and although we now look through our family albums on a computer screen, we do not doubt these pictures any more than we did those that the local photographer took in times past” (p. 424). Sarah Kember (1998) similarly brings indexicality to the level of affect when she writes that “[t]he power of affect in photography seems to derive — perversely — from the ‘real’ that critical languages can reason away but cannot finally expunge from the subject’s experience of photography” (p. 31). Likewise, Tom Gunning (2004) urges a departure from indexicality as a purely semiotic category and demands a more in-depth engagement with the visual experience that photography offers.

Recent scholarship on photographic indexicality (Green & Lowry, 2003; Elkins, 2007; Batchen, 2009) has resulted in the rethinking of the term and evaluating its performative dimensions. David Green and Joanna Lowry (2003) emphasize not only the existential relationship between photograph and object but, reiterating J.L. Austin’s theory of speech acts, they foreground the performative function of the camera in claiming the event that it captures in the form of the photograph. In this sense, Green and Lowry argue, the “frame is not so much a delimitation of a semiotic space, but more an arbitrary event, a performance, a gesture that points to the scene and in doing so points to our inability to read it” (p. 60). Understanding indexicality as a performative gesture of pointing, rather than merely an indicator of the photograph as a material trace sustained at an affective register, is helpful to account for the complex visual experience rephotography projects offer.

Rephotography

We have already seen how Barthes identifies a new space-time category brought forth by photography, a concept he develops into his notion of the anterior future in Camera Lucida. The photographs that he describes in his book are, however, analogue images. Digital photography, bereft of the chemical connection analogue images have with their referents, jeopardizes the notion of material indexicality. Insofar as rephotography blends analogue and digital photography within the same frame notions of indexicality predicated on the material connection between photograph and referent are complemented, as well as complicated, by a digital image, which frames the analogue picture. While the Barthesian space-time categories provide a useful theoretical apparatus, they need to be adjusted to account for the visual experience offered by these layered images. Likewise, indexicality as pointing, rather than a pure indicator of material connection, allows for a more nuanced articulation of this experience.

Let us now revisit the phases of rephotography with Barthes’ terminology in mind. In the first phase, when the rephotographer tracks down the location depicted in the old photograph, details of the environment that match up with the photo serve as reference points — streets, buildings, statues, curbs, street furniture, etc. Once the image is mapped on its original setting, space is experienced temporally as though in a virtual archeological excavation. What Barthes formulates as an anterior future is here augmented by the embodied encounter with the materiality of the environment as the actual location of the photographed event. The recognition of these corresponding details leads to the experience of place as a haunted terrain, imbued with the lingering presence of the past. As a result, what Barthes describes by looking at Gardner’s photograph as “this has been” gains a spatial dimension in the first phase of rephotography: this has been here. What pricks me, to borrow Barthes’ word, is the sense of hereness, which consists in the sensation of the material relation between the details of the environment and its photographic representation. In Barthesian terms, the “awareness of the having-been-there” (1991, p. 44) is here supplemented by the sensation of having-been-here: this photograph was taken right here and the street corner that I see in front of me is exactly the same as the one depicted in the photograph. The matching details thus gather a sense of aura. Despite their spatial proximity they serve as signifiers of a past that survives only in the photo. Present in both the photograph and in physical reality, they become gateways for the past to encroach on the present. It is for this reason that I call them time-bridges. In Peirce’s sense, these time-bridges are first engaged as iconic signs, for it is the congruence between the details in the photograph and the environment that attracts the rephotographer’s attention in the first place. It is by way of assuming the same perspective and adjusting the photograph to fit the physical background that iconicity is complemented by indexicality as an experience of hereness. The time-bridges stand as survivors that have witnessed the event depicted in the photograph. If, as Barthes claims, the photograph is an “illogical conjunction between the here-now and the there-then” (1991, p. 44), time-bridges are material buttresses of this conjunction, by which the here-now, which Barthes identifies as the photograph’s unreality, “for the photograph is never experienced as illusion, is in no way a presence” (p. 44), emanates, as it were, into the materiality of the present.

In this context, indexicality is not so much the property of the analogue photograph per se but the result of a performance whereby the photograph is recycled into the physical environment. While in Green and Lowry’s (2003) reading of Peirce it is the very act of photography, the pointing of the camera, that constitutes this performative gesture, here, indexicality constitutes the very act of choosing an analogue photograph and fitting it into its physical setting. In the second phase of rephotography the sensation of hereness is transferred to the new photograph. The camera, in this phase, is simultaneously pointed at the time-bridges and the event that they signify. If the photograph, to evoke Barthes, bespeaks what has been, the camera of the rephotographer, as well as the new image that it yields, recontextualizes the original photo along spatial and temporal lines. Upon looking at this new image the experience of hereness appears at a remove from the viewer and is perceived as thereness. Likewise, the temporality of the new image relocates the analogue photo into the realm of the past perfect tense. To rephrase Barthes’s formulation of the anterior future, what I read at the same time: this had been and this has been. The new digital image reveals what is still a future in the old one. While the so-called before-and-after photographs allow the viewer to scrutinize the similarities and differences between the old and the new image placed side by side, rephotography frames the old within the new, thereby subjecting the analogue to the digital. Once the superimposition is complete, the old image will blot out the terrain behind it and the time-bridges will only work along the border of the old and the new picture. Therefore, the digital construction of these borders and frames plays a crucial role in the affective experience of the photo.

Different techniques of framing offer different affordances for affective engagements with the temporality of space. I will explore these affordances through two case studies that map instances of two world wars on contemporary urban environments. The two projects represent popular techniques of digitally framing the old photograph within the new. While these techniques cater to different affective engagements, I will also demonstrate that understanding indexicality as an act of pointing, rather than a mere ontological quality, is helpful to account for the reality-effect that these images convey, despite their obvious use of digital layering.

Blurred contours: Jo Teeuwisse’s Ghosts of History

Rephotography has been booming on the Internet over the past few years. Urban locations that have suffered war damage are particularly popular targets, especially with the series of World War I and World War II anniversaries on the way. In his photo-series entitled Blitz Ghosts,2 Nick J. Stone maps archival images of the German bombing of Norwich onto the city’s modern streetscapes. His images went viral shortly after the 70th anniversary of the Blitz (Welch, 2011, n.p.). Perhaps the most well known among rephotographers of World War II sites is Sergey Larenkov. His website Связь времен / Link to the Past3 features sites from war-torn Berlin to Moscow and, most prominently, his native St. Petersburg. A typical characteristic of these projects is that they project archival images of destruction onto their present-day settings in such a way that the border between the old and the new photograph is blurred and the former emerges as a ghostly apparition from the latter. Similarly to Stone’s and Larenkov’s technique, the Dutch historian Jo Hedwig Teeuwisse’s 2012 series Ghosts of History4 merges photographs of the liberation of Western Europe with contemporary streetscapes. I will now use one of Teeuwisse’s superimpositions to explore the affective dimensions of the blur.

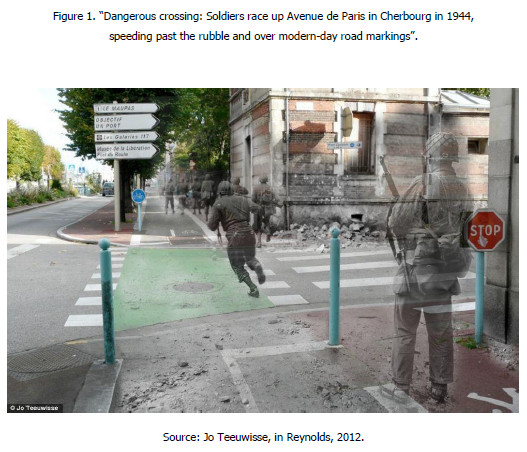

The photograph is one of the widely circulated ones in the series, especially after its appearance in the online version of the Daily Mail in October 2012. The image shows an intersection at a street corner with the lower façade of a building occupying the top right quarter of the photo with a crosswalk alongside a green bike lane in the foreground. As though transparent, ghostly figures, a group of American soldiers are visible in black and white, trying to cross what seems to be a dangerous intersection and move ahead (figure 1).

According to the caption in the Daily Mail, the old photograph was taken in 1944 at an intersection in Cherbourg (Reynolds, 2012, n.p.) and, scrolling further down, the article shows both the old black and white image and the new color photo that Teeuwisse used for her project. Once superimposed on one another, the two images form a photographic palimpsest where both layers are exposed in such a way that the old photo seems to emerge, as it were, from the new image.

This technique allows Teeuwisse to make choices regarding details and the temporal layers she wants to foreground. The difference between the black and white tones of the old photo and color patterns of the new one serves the viewer as a temporal reference point. However, Teeuwisse’s composition is not without a tinge of humor. For instance, the peaceful scene with the green bike lane and the red stop sign in the foreground puts an ironic gloss on the soldiers’ effort to cross the street in the midst of enemy gunfire. Similarly, the lowest one of the white arrows in the top left corner already points the modern-day tourist in direction of the Musée de la Libération in Fort du Roule, a detail poignantly juxtaposed with the ongoing liberation itself, performing the anterior future that is still yet to come at the temporal level of the old photograph.

This stark contrast between the events at the exact same street corner at war and in peacetime gives a poignant edge to the sensation of thereness. The mundane details of the corner, the bike lane, the signs, the façade of buildings are all defamiliarized once they give way to the uncanny emergence of a violent past that has transpired in their midst. The photograph taken in the turmoil of war by the photographer following the advancing soldiers is similarly defamiliarized by a peaceful present that Teeuwisse constructs digitally, presenting a future of which the soldiers on the ground are unaware. However, what Barthes describes as an anterior future in the case of Gardner’s photograph here gains a spatial dimension. It is in the sensation of thereness, rather than in the knowledge of what is still the future in the photograph, that governs the affective register of the juxtaposition of the two images. In other words, the visual experience of what had been (in the form of the old photograph) and what has been (in the form of the new one) translates into a heightened sense of the temporality of place. The anterior future, in Teeuwisse’s image, materializes in the “present perfect” of the new photograph, framing the “past perfect” of the old one.

Time-bridges play a particularly important role in generating the sensation of thereness. The soldier on the right appears as though standing on the new pedestrian path, indicated by a walking sign in the bottom right corner. Ironically, not only is he on the appropriate side of the pavement, he also “obeys” the stop sign on his right. At the same time, this humorous juxtaposition of metonymic signifiers of war and peace is supplemented by the soldier’s ghostly presence at a temporal plain where he is out of place. The grey blocks of the corner of the building to his right seamlessly connects black and white and color, offering a time-bridge between two temporal plains. This bridge acts as a material witness to the presence of the soldier then (had been) and the presence of the pedestrian path now (has been). The corner façade of a building visible in the top right quarter of the image operates slightly differently and elicits a rather different affective response. While the grey tones of the corner in the foreground make it impossible to guess where the past begins and the present ends, in the case of the building on the opposite side of the street the black and white image gradually morphs into the lighter tone of red brick, accentuating the persistence of that wall section for over seventy years. Reinforcing this material correspondence the drain, which runs vertically along the wall, smoothly joins up with its counterpart from 1944. The exposed façade, in this sense, functions as a time-bridge where points of congruence come forth from the digital fog along the border of two temporalities.

An essential component of Teeuwisse’s technique, the blur operates at two affective registers. Occupying a liminal position between the two layers of the photographic palimpsest the blur allows the eye to perceive similarities, rather than differences. Here, the time-bridges are never sharp details or edges but fluid forms and shades of color that morph into each other.5 On the other hand, the porousness of the borders between the two temporal plains vests the old image of its identity as a photograph and transforms it into a repository of the past that cannot be kept at bay as it uncannily resurfaces in the new photograph and demands to be contended with. As Teeuwisse reflects, “I knew what happened there, but knowing the exact spot of some detail will etch it into your visual memory” (qtd. in Reynolds, 2012, n.p.). Paradoxically, it is through the blur’s potential to hide incongruent details that the past manifests itself in her work as a spatial presence.6 This paradox also makes itself felt at the level of indexicality. The blurring of the frame is digital manipulation of the most obvious kind, which jeopardizes the material indexicality conventionally ascribed to analogue images. However, the acclaim she has received for her work suggests that the photo’s indexical power lies not so much in material connectivity as it does in the performative gesture of “spacing” the old image in a contemporary setting. Paradoxically, while digital manipulation weakens the indexical power of the two superimposed frames, it nonetheless amplifies the indexicality of the Teeuwisse’s photographic palimpsest.

Sharp contours: Peter Macdiarmid’s rephotography of World War I

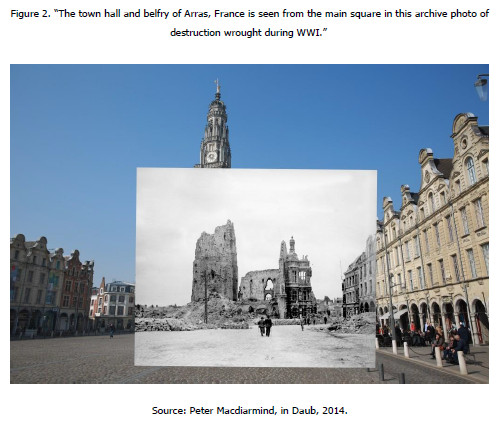

I will now turn to a technique of rephotography where the border between the old and the new is clearly distinguishable. Getty Images photographer Peter Macdiarmid’s 2014 series of World War I photographs superimposed on their present-day urban settings is among the few war-related projects that refrain from blurring the border between the past and the present. Created as a photographic gesture to commemorate the First World War, Macdiarmid’s project has received publicity on PBS Newshour7 and In Focus.8 In one of his images Macdiarmid superimposes a photograph of the destroyed belfry of the French city of Arras on a new photo of the rebuilt tower (figure 2). Instead of blurring the borders, which, in Teeuwisse’s project induces the sensation of the past welling from within the present, he positions the old photograph as though overlain on the new. As a result, the old photograph blots out a significant portion in the new one, allowing the rebuilt spire to hover, in the anterior future, above its own ruin.9

Although the element of defamiliarization is no less poignant here than in Teeuwisse’s work, the absence of blurred contours makes time-bridges operate in a different way. While the blur allows the viewer to easily overlook discontinuities, this version of rephotography rather accentuates the borders between old and new. Consequently, it foregrounds, rather than hides, the imperfections in aligning the two images. For instance, the curb that separates the sidewalk from the square in the old photograph is perfectly matched up with the curb in the new image but the buildings on the right are aligned much less seamlessly. While Teeuwisse’s technique fashions the past as an uncanny force that haunts the present, Macdiarmid allows no transparency between the two images, thus keeping the two temporal plains apart. The stark contrast between the temporal layers keeps the ruins of the belfry at a remove from the vivid colors of the contemporary city. Unlike in the Normandy street-scene, the photograph of the destroyed belfry appears as if “laid over” the color image. This performative aspect of the project is most conspicuous in a video created by Getty Images where the old images are laid over their present-day settings (Macdiarmid, 2014, n.p.).

While Teeuwisse blends the two time-levels so that the past can lay claim on the present in the form of haunting, Macdiarmid does the opposite by foregrounding the photographic quality of the old image, thus withholding the past from infiltrating the present. This is not to say, however, that the latter is more truthful or realistic than the former. On the contrary, the black and white photos Macdiarmid uses are just as much subject to digital manipulation as those of Teeuwisse. The blur and the sharp contours are two sides of the same (digital) coin. Both serve as techniques of building time-bridges that put the attentive viewer into the role of the archeologist scrutinizing corresponding details between two time-levels. Because any detail can potentially be a time-bridge, rephotography grants a distinguished role to the built environment.

Conclusion

The technologies of “time-bridging” featured by these two case studies present us with a paradox: despite the obviousness of digital doctoring, which jeopardizes the indexical properties of the individual frames, once superimposed, the layered image acquires strong indexical appeal, as evidenced by comments on Teeuwisse’s and Macdiarmid’s work posted on the Internet. This paradox indicates the emergence of new conditions of photographic referentiality, which seems to have shifted from the Barthesian formulation of material connectivity between image and referent towards the dissolution of traditional hierarchies between analogue and digital. As Martin Lister observes,

It matters not whether an image was captured by the photosensitive cells of a digital camera (clearly a form of indexical registration), or, perhaps more surprisingly, was a conventional photograph that is subsequently scanned by a computer and altered, or is a combination of two digitised photographs and computer generated elements. All of these images address us as photographs (Lister, 2008, p. 316).

In other words, digital images “touch” us, in Barthes’s sense, no less than analogue photographs, not because of material indexicality but because we engage with them as photographs. In the context of rephotography digital manipulation may indeed destroy the indexical appeal of the analogue and the digital frame but once blended in a single image, their indexical effects are amplified. Therefore it is not so much that the digital image gains its indexical effect from the analogue one as that it is through rephotography as a performative gesture that both the analogue and digital frames are ascribed indexical value. If the element of pointing is key to understanding indexicality in rephotography, it is no surprise then that a growing number of such projects operate as online interfaces that reveal urban space as a repository of photographically captured memories and designate mundane locations as sites of memory.

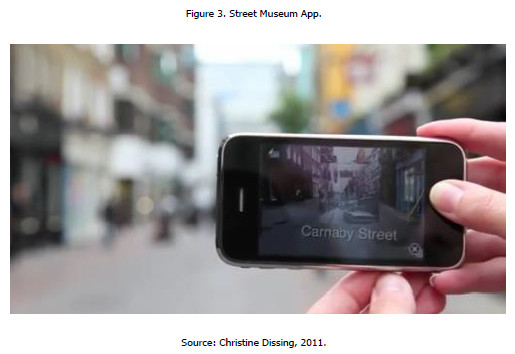

The increasing number of augmented reality applications offers new ways to engage with the urban past akin to rephotography. Emerging urban-image technologies, such as the Museum of London’s augmented reality application “StreetMuseum,”10 allow users to view historical photographs “in situ.” This application recognizes users’ location in the street and overlays corresponding historic photographs of London onto present-day locations. StreetMuseum shows close kinship with rephotography in the sense that what users see on the screen of their smartphones is the actual streetscape framing the old photograph (figure 3). However, this kind of affective engagement with the temporality of urban space is essentially different from engaging with Teeuwisse’s and Macdiarmid’s photographs on the Internet. What StreetMuseum offers is an embodied engagement with the city as a palimpsest whose layers unfold as one walks from location to location. In this sense, the application puts the user into the role of the rephotographer and the viewer simultaneously. While the GPS device assists in the process of identifying the historic image that corresponds with the location of the user, the joy of discovering time-bridges is comparable to the first phase of rephotography. Similarly, the image that appears on the screen is not unlike those of Macdiarmid’s superimpositions with their sharp borders. However, instead of catering to the experience of thereness, StreetMuseum allows users to engage with the layered temporality of the city in movement. Thus the screen of the smartphone is at once a gateway to the past and a window through which the city unfolds in the present continuous, surrounding the user. If the virtual and the material are indeed enmeshed in our navigation of urban space, applications such as StreetMuseum substantiate this tendency and pave the way for future development.

References

Bachelard, G. (1994). The poetics of space. Boston: Beacon Press. [ Links ]

Baer, U. (2002). Spectral evidence: The photography of trauma. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Elkins, J. (Ed.). (2007). Photography theory. New York and London: Routledge. [ Links ]

Barthes, R. (1991). Rhetoric of the image. Image, music, text. New York: The Noonday Press. [ Links ]

Barthes, R. (1993). Camera Lucida. London: Vintage. [ Links ]

Batchen, G. (Ed.). (2009). Photography degree zero: Reflections on Roland Barthes’s Camera Lucida. Cambridge MA: MIT Press.

Bazin, A., G., H. (1960). The ontology of the photographic image. Film Quarterly, 13(4), 8. [ Links ]

Daub, T. (2014). The town hall and belfry of Arras, France is seen from the main square in this archive photo of destruction wrought during WWI. 8 Apr. Retrieved from: http://www.pbs.org/newshour/updates/images-world-war-devastation-overlaid-modern-photos-france/

Dissing, C. (2011). Street museum app. Attention2Ads.com. Retrieved from http://attention2ads.com/post/2797866923/taking-arts-to-the-streets-the-street-museum-app

Elkins, J. (Ed.). (2007). Photography theory. New York: Routledge. [ Links ]

Green, D. & Lowry, J. (2003). From presence to the performative: rethinking photographic indexicality. In Gree, David (Ed.), Where is the photograph? (pp. 47–60). Maidstone: Photoworks; Brighton: Photoforum.

Gunning, T. (2004). What’s the point of an index? Or, faking photographs. NORDICOM Review, 5 no. 1(2), 39–49.

Gunthert, A. (2010). The digital imprint: the theory and practice of photography in the digital age. In Swinnen, Johan, Deneulin, Luc (Eds.), The Weight of Photography: Photography History Theory and Criticism. Brussels: Academic and Scientific Publishers. [ Links ]

Jay, M. (1993). Downcast eyes: The denigration of vision in twentieth-century French thought. Berkeley: University of California Press. [ Links ]

Kember, S. (1998). Virtual anxiety: Photography, new technologies and subjectivity. Manchester: Manchester University Press. [ Links ]

Krauss, R. (1986). The originality of the Avant-Garde and other modernist myths. Cambridge: MIT Press. [ Links ]

Lakoff, G. (2001). Metaphors of terror. The Days After. Chicago: University of Chicago. Retrieved from http://www.press.uchicago.edu/News/911lakoff.html

Leach, N. (2006). Camouflage. Cambridge MA: MIT Press.

Levy, L. (2009). The question of photographic meaning in Roland Barthes’ Camera Lucida. Philosophy Today, 395–406.

Lister, M. (2008). Photography in the age of electronic imaging. (3rd Ed.) In Wells, Liz (Ed.), Photography: A critical introduction (pp. 297–336). London: Routledge.

Macdiarmid, P. (2014). The First World War remembered. In Focus. Retrieved from http://infocus.gettyimages.com/post/the-first-world-war-remembered#.VPs5jxwQ5Zc

Mitchell, W. J. (1992). The reconfigured eye: Visual truth in the post-photographic era. Cambridge: The MIT Press. [ Links ]

Peirce, C. S. (1965). Collected papers. Cambridge MA: Harvard University Press.

Reynolds, E. (2012). The ghosts of World War II: The photographs found at flea markets superimposed on to modern street scenes. Mail Online. 18. Oct. Retrieved from http://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-2219584/Ghosts-war-Artist-superimposes-World-War-II-photographs-modern-pictures-street-scenes.html

Welch, J. (2011). Picture gallery: Norwich Blitz ghost photos are an Internet hit. Edp24. 1 Mar. Retrieved from http://www.edp24.co.uk/news/picture_gallery_norwich_blitz_ghost_photos_are_an_internet_hit_1_815661

Young, J. (2000). At memory’s edge: After-images of the Holocaust in contemporary art and architecture. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank the reviewers of the first draft of this article for their valuable comments for improvement.

NOTES

1 The trend does not have an official name and it is also referred to as superimposed photography. While the latter term generally emphasizes the layered structure of the resulting image, rephotography foregrounds the repeated photographic documentation of the same site, which finds its roots in the geographical practice of documenting changes that have occurred in a natural or urban setting over a period of time. Although the two terms are often used interchangeably, I will use rephotography because it implies both revisiting and re-documenting a particular location.

2 https://www.flickr.com/photos/osborne_villas/sets/72157625836754972

3 http://sergey-larenkov.livejournal.com/

4 https://www.flickr.com/photos/hab3045/collections/72157629378669812/

5 For more on the use of blur as a means of foregrounding continuities see James Young’s analysis of David Levinthal’s photographs of toy figures (2000, pp. 42-61).

6 This ghostly presence of the past is achieved in a completely different way in, for instance, Mikael Levin’s and Dirk Reinartz’s photographs of Holocaust sites, where it is through the unsettling absence of traces of the past that their photographs of nondescript landscapes gain ominous force (Baer, 2002, p. 61-85.)

7 http://www.pbs.org/newshour/updates/images-world-war-devastation-overlaid-modern-photos-france/

8 http://infocus.gettyimages.com/post/the-first-world-war-remembered#.VPs5jxwQ5Zc

9 This is not say, however, that Macdiarmid does not experiment with the blur. His most recent work on World War I-related sites featured on the online edition of The Telegraph subscribes to this technique (http://www.telegraph.co.uk/history/world-war-one/10993859/WWI-photographs-superimposed-into-modern-times.html).

10 http://www.museumoflondon.org.uk/Resources/app/you-are-here-app/home.html