Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Acessos

Acessos

Links relacionados

-

Similares em

SciELO

Similares em

SciELO

Compartilhar

Observatorio (OBS*)

versão On-line ISSN 1646-5954

OBS* vol.9 no.Especial Lisboa dez. 2015

Not only a workplace. Reshaping creative work and urban space

Tanja Sihvonen*, Boukje Cnossen**

*Professor, Faculty of Philosophy, Communication Studies, University of Vaasa, Finland (tanja.sihvonen@uva.fi)

**Phd-Student, Tilburg School of Economics and Management, Tilburg University, the Netherlands (b.s.cnossen@tilburguniversity.edu)

ABSTRACT

This research article examines the intersection of two current topics: the ongoing flexibilisation of creative work on the one hand, and the emergence of urban temporary working landscapes on the other. Their interrelatedness is inspected through a case study of one particular creative hub, the former Volkskrant building in Amsterdam, and through analysing its transformation into a “creative’ hotel. Based on intensive qualitative fieldwork in 2012 and 2013, we argue that the importance of such temporary hubs lies beyond the fact that these places provide professionals in the creative industries with desk space. By mobilising the concept of engagement, we draw parallels between the ways in which creative urban professionals shape the physical spaces they use, and the ways digital media users appropriate virtual spaces. We argue that an understanding of the changing practices of creative workers might benefit from a revisiting of the concepts “loose space’ and “Thirdspace’, as these notions help challenge the false dichotomy between “real’ and “imagined’ space. We believe that this continuous re-imagining and repurposing of space while working in it, together with the possibility of actual, physical modification as afforded by the particular countercultural heritage of Amsterdam, reveals the creative potentialities of these flexible work practices.

Keywords: Amsterdam, creativity, work, engagement, ecosystem, loose space, Thirdspace.

Introduction

In the past two decades, academics across disciplines, politicians and policymakers have drawn attention to the idea of a global, innovative and technology-driven economy – the so-called creative economy. Defined by thinkers like Richard Florida (2005), Charles Landry (2008) and John Howkins (2013), the creative economy is a variety of the knowledge economy in which the loosely defined creative industries play a central part (Peters, 2010, Stankevičienė et al., 2011). In this line of thinking, creative businesses are expected to solve the economic crisis by sustaining economic growth in non-traditional ways as well as creating new forms of employment and wealth in the long term (Yigitcanlar et al., 2007). The core task of the creative industries is to develop and exploit intellectual property, which will ultimately generate prosperity and create jobs (Peters, 2010). The creative economy is therefore a variant of the larger concept of digital economy, which is seen as the result of vast transformative processes in modern life and work, brought about by information and communication technologies (OECD, 2014).

Policies aimed at stimulating the creative economy are closely connected to urban planning and regeneration projects. According to the Richard Florida-inspired reasoning of policymakers, the argument goes that cities have to be attractive first in order to appeal to those high-skilled and creative professionals who will give the local economy its much needed boost with their innovative businesses (Nathan, 2007). Another motivation is that creative workers, typically less demanding than corporations and government organisations when it comes to architectural qualities and housing, are the perfect workforce in cities’ tasks to revive old industrial areas because they arguably “constitute space with their communicative practices’ (Lange et al., 2008). Finally, creative cities are also supposed to attract a crowd of hip, art-loving tourists. The socio-cultural symbols of the creative class may thus render the remnants of industrialism not only useful, but also trendy (Pohl, 2008).

For these reasons, the creative city discourse has quickly become the justification for projects aimed at creating economic value by supporting “knowledge”, “creativity” and “innovation” on all levels of society (e.g. Landry, 2006). These buzzwords mark abstract ideals that are considered to play an important role in strengthening the dynamism, resilience and overall competitiveness of economies by enhancing the innovativeness of individuals, businesses and organisations alike, and thus improving the quality of life and the range of opportunities (Gertler, 2004). However, as Markusen and Gawda (2010) have shown, we still lack in-depth knowledge about which creativity-inspired urban regeneration strategies work and on which scale, urban or regional, these are the most effective. Furthermore, the urban regeneration strategies which have the influx of a “creative class” (Florida, 2002) at their core, have been criticized for driving out members of the working class, as their places of work and leisure are replaced by expensive and exclusive-looking bars, shops and cafes. As such, creative city policies are seen as rendering cities less socially equal, all whilst the causal relationship between this creative class and economic growth remains uncertain (Pratt, 2008).

It has also been challenging to define innovation and to see what drives it in different contexts. Some research has analysed the needs and desires of knowledge workers and concluded that creative people prefer intense, active and diverse urban environments (e.g. Yigitcanlar et al., 2007). The background for this thinking is often drawn from Richard Florida’s (2005; 2014) work, in which he regards creativity and knowledge production as essentially urban phenomena, requiring knowledge infrastructure as well as a vibrant urban life characterised by diversity and tolerance. It seems that the link between creativity and “urbanity” is assumed without question (Lawton et al., 2012, Miles, 2005), but exactly how this link is constructed requires further study.

Research in management and business has focused on innovation mainly on the level of the company (Arora, Belenzon & Rios, 2014, Karim & Mitchell, 2004), leaving a gap when it comes to understanding the processes of innovation in and between individuals who do not necessarily have any professional ties. And while recent research in this vein has argued in favour of flexible and adaptable office set-ups with large open spaces and no fixed arrangements so as to stimulate collaboration and creativity (Fayard & Weeks, 2011), other research has pointed out that people’s sense of ownership of their work environment correlates with a sense of ownership of their work (Pierce, O’Driscoll & Coghlan, 2004).

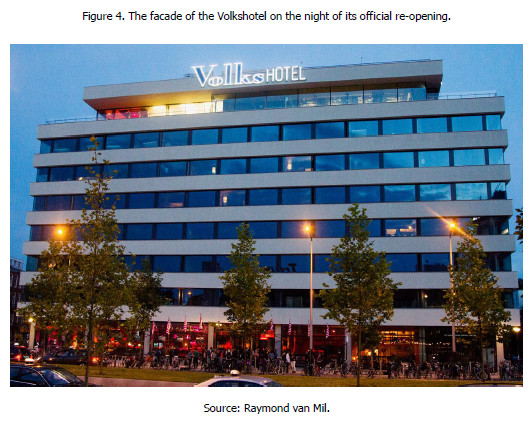

The purpose of our article is to fill these gaps by offering a micro-level analysis of the ways in which flexible urban structures facilitate new ways of organising work and recreation. We do so through a case study of what is now the Volkshotel, a building which was up until recently known as the Volkskrant building. This former newspaper office became a nexus for Amsterdam’s creative scene between 2007 and 2013. Due to its success, in 2014 it was turned into a multifunctional building comprising an “arty” hotel by commercial investors. We followed these processes from an insider position. The first author was working with a digital design agency, which resided in this building whilst completing a post-doctoral study. The second author was conducting a one-year ethnographic study on the entire building (see Cnossen & Olma, 2014). The extensive ethnographic fieldwork that led us to notice the parallels between the use of real space and virtual space eventually inspired this article.

Taking this building – arguably the most iconic hub of the Dutch creative industries – as the example, we will show how the constant reshaping of this workplace exemplifies the heritage of the squatting movement and its “mainstreamed” leftovers. In this text, we will contextualise the Volkskrant building in relation to the developments in city planning in Amsterdam, and in particular within the fast-growing trend of setting up so-called art factories or incubator spaces (Cnossen & Olma, 2014), which we call creative hubs, or hubs, for short. This analysis will be carried out from looking at the perspectives of policymakers and urban planners, as well as the creative workers themselves. Drawing from the ethnographic fieldwork – participant observation, interviews, photographs1 and focus groups – which was conducted on an almost daily basis at the Volkskrant building between 2012 and 2013, we will discuss how the needs of creative workers relate to the interests of local government and investors, as well as where the frictions and tensions are. We will show how the city of Amsterdam and its particular history of counterculture and experimental uses of urban space directly feed into the new ways of organising creative work, especially as these are taken over by commercial investors, as was the case with the Volkskrant building.

Urban planning is constrained by technological, economic and political (regulatory) forces. The focus of this article, however, is to regard urban space and its design as a result of ongoing process on a micro-level, rather than as the execution of top-down decision-making (e.g. Carmona et al., 2003). In order to understand the characteristics of these micro-level processes, it is essential to unravel the associated politics of these (Crang & Graham, 2007). Instead of trying to analyse the much more common “fixed” spaces, their meanings and uses, we conceptualise spaces as being always in a process of emergence, as resulting from social practices that continuously have to sustain them or mould them into new spatial articulations. We are particularly interested in the type of threshold spaces and in-between areas that relate rather than separate (see Stavrides, 2008, p. 174), and we argue that these in-between areas increasingly merge virtual and real space. We assert that the practices shaping these spaces show similarities to the way a computer user “conquers” digital spaces.

Situatedness, or the involvement within a context (Vannini, 2008, p. 816), is the result of constructive practices that the users and inhabitants of specific spaces engage in. Spatial settings sometimes explicitly invite their users for appropriation and modification. These space shaping practices are nowhere more evident than in those urban sites that explicitly invite their users to make of them what they want, to adept them to their needs. The first tenants who rented workspace in the Volkskrant building when the newspaper had vacated the premises in 2007, were actively encouraged to alter their new workspace. Thus, although the Volkskrant building provides workspaces, it is much more than a place to work in. By allowing its users to continuously shape the place they use, the space helps negotiate the creative practices and identities the tenants want to engage in their professional lives.

Thus, we use the concept of engagement in order to discuss how flexible spaces and creative work practices are mutually constitutive. We seek to study how the processes of engagement work in the context of navigating and orientating oneself in these work-related urban spaces. Situating engagement design in a particular spatial setting and learning from comparisons with usages of digital space allows us to articulate insights about design elements and choices that can eventually have an impact on the wider contexts of architecture and urban planning.

First, we will show how the global push for the creative city and the local, rich histories of squatting intersect in Amsterdam in general, and in the Volkskrant building in particular. Second, we argue that the spaces that emerge as a result of this intersection can be conceptualised as “loose space”, and that an understanding of the interactions between their users and occupants benefits from a revisiting of the concept “Thirdspace”, or the coming together of real and imagined space (Soja, 1996). We believe that this continuous re-imagining of space while working in it, together with the possibility of actual, physical modification as afforded by the particular countercultural heritage of Amsterdam, reveals the creative potentialities of these flexible work practices.

Subsequently, we propose that an analysis of the interaction between users and these spaces will be substantially enriched through use of the concept of engagement. The ways in – and extent to – which engagement occurs will provide a valuable new approach in looking at current urban development, flexible work space and how it can best serve the needs of today’s connected city dwellers and workers. Through this analysis we want to articulate the issues inherent within creativity-led urban development of this kind, allowing for a greater focus on what might be termed the “respatialisation” of creative activity, and its links to ongoing societal and academic debates on, for instance, the dynamics of gentrification and the commodification of subcultural aesthetics. As a concrete example of this, we will analyse the transformation of the Volkskrant building from independent creative hub into a hotel, which is branded as “creative”.

The Volkskrant building as a new “freespace”?

Although Amsterdam is replete with empty buildings, it is still hard to find a place to live and work. As buying a house is traditionally not an option, and the average waiting time to get a municipal rent-controlled flat is currently more than ten years (Van Zoelen, 2012; Arnold, in this special issue), Amsterdammers get by with temporary solutions. A popular one is the so-called antikraak [anti-squatting] agreement, which gained its reputation as a tool for landlords to keep their property safe from squatters. Ever since the law against squatting has been installed in 2010, the term huisbewaring [house watch] is more often used for the same construction. The rent prices in these agreements are usually very modest, but along comes a temporary rental contract with a measly two weeks’ notice period and no tenant rights.

The property crisis following the global financial crisis that began around 2008 has hit the Netherlands as well as many other countries. Many large office buildings were left unoccupied, so much so that in 2013, the Netherlands had the highest number of vacant office buildings in Europe (Eigenraam, 2013). The housing corporations and property firms which own these building have no interest in making expensive investments, so they offer them for temporary use against a very low rent. Between pre-crisis extravagances and mid-crisis apathy, a range of bottom-up initiatives has ceased the opportunity to set up temporary communities to live, work, or combine the two. Examples of these include social enterprises or small collectives of individuals who use empty buildings for social and cultural purposes, but also commercial enterprises who negotiate low rents on an entire building in order to then rent them out to self-employed professionals (Van den Berg, 2014; Miazzo & Kee, 2014). Whether located in one building or spread across a cluster, such initiatives are found in cities across all around the world (Gibson et al., 2012).

While the effects of the financial crisis and related property crisis are evident in almost any major European city, there is a remedial policy typical to Amsterdam which has come to define the city’s approach to spaces for creative (work) purposes. It is the so-called broedplaatsen policy, a programme put in place in 2000 to protect and enhance the city’s cultural climate (Cnossen & Olma, 2014, Wolsink, 2014, Pot, 2011). At the core of this policy lies an attempt to prevent gentrification and promote independent culture, rooted in the tradition of squatting buildings. In the 1970s and 1980s, Amsterdam had a thriving subcultural scene the main intersections of which were located in squats (Soja 2000). Squats were not only places of living but also places of work – or more, a way of life. Squatted buildings were considered as vrijplaatsen or “freespaces” where creativity and DIY attitudes were regarded as tools to becoming completely autonomous. Some of them employed people and took part in economic activity. Many squats stimulated the local cultural scene with their own radio and TV broadcasts, newspapers, music, restaurants and bars (Keizer, 2014, Van de Geyn & Draaisma, 2009).

Towards the end of the 1980s, many initially squatted buildings were legalised and continued as autonomous social and cultural centres (Breek & De Graad, 2001). In the 1990s, however, rapid economic growth caused the Amsterdam city government, led by the social democrats, to push various areas of the city towards gentrification. One of this era’s most fundamental political decisions was the privatisation of the housing corporations, making social rent-controlled housing the responsibility of privatised firms and turning originally working-class neighbourhoods like the Pijp and Oud-West into hipster areas for the new middle classes (Van de Geyn & Draaisma, 2009). Freespaces became limited and the remaining underground scene was under threat. This caused an uproar amongst a group of activists, who in 1998 adopted the slogan “No culture without subculture”. They convinced the city of Amsterdam to protect (former) squatters from being priced out of the city, using the argument that the city owed its rich clubbing scene and many cultural initiatives to the freespaces.

Eventually, the city decided to use some of the funds acquired from selling off land to commercial investors to install a budget aimed at protecting its subculture (Cnossen & Olma, 2014). This was the beginning of the broedplaatsen policy, in which derelict property is temporarily regenerated and repurposed by and for artists and other creative professionals. What broedplaatsen and other local bottom-up initiatives have in common is that they can be realised not in spite of, but because of the property crisis. They use temporariness as a diplomatic tool to push things through, and can count on young creative professionals to agree to renting spaces for a few years at most. In 2005, the broedplaatsen policy was transferred from the cultural agenda to the economic agenda when Richard Florida visited Amsterdam and convinced the city officials that the creative city could be thought of as a method for economic growth in a time of global competition (see Peck, 2012). From then on, broedplaatsen were not only aimed at social and cultural activity, but had to instigate entrepreneurship as well, although many struggled to live up to that task (De Jong, 2012). This transformation is aptly exemplified by the redevelopment of the Volkskrant building. The building stands as a veritable totem between the heritage of the squatting movement and the promises of creative city policies.

The Volkskrant building is situated in the eastern part of Amsterdam city centre, at number 150 of the busy Wibautstraat. As the name suggests, the building used to house the major Dutch newspaper De Volkskrant, and it was part of the former publishing cluster known as the “Parool Triangle”. When the newspaper editing offices moved out in 2007, the building was considered ready for demolition. Then a non-profit organisation Urban Resort – consisting of members of the 1980s squatter movement – approached housing corporation Het Oosten – which owned the building - with a request to turn it into a temporary community for social, cultural and artistic experiment. Backed by the financial support from the broedplaatsen policy, Urban Resort set out to draw a business plan for the building based on rents below market standards and flexible rental contracts. As they managed to secure a contract with the owner, anyone who wanted a space in the building was invited to apply. In order to deal with the large scale of the building, everyone had to apply as a group. This way, or so it was thought, collectives and communities would eventually settle in, rather than a mass of individuals.

Those groups that were selected differed a lot from one another in terms of their artistic discipline, level of professionalism and socio-economic background. Each group was given (parts of) a floor and they were encouraged to run the space themselves. They were expected to organise events, collaborate on projects, mobilise their potential for the wider community and the city, but also to take care of maintenance issues collectively. Although the building was used for professional activities and not for living, rent did not cover facilities such as cleaning and hence tenants were supposed to take care of such tasks themselves. In hindsight, it is clear that on many floors this plan did not succeed. The first years of the Volkskrant building were marked by thefts and vandalism on various floors, as well as Urban Resort’s budgeting problems which together resulted in angry tenants.

Many of these problems relate to the fact that the initiators of the hub, Urban Resort, directly drew on their expertise with squats in the 1980s, when people willingly put a lot of time and effort in managing occupied buildings (Cnossen & Olma, 2014). Urban Resort faced the need to raise the rents in order to deal with the building’s outdated heating and air ventilation systems and the lack of security. After a while, about half of the original tenants left. In order to tackle the financial issues Urban Resort had at that point, many of the new tenants had to be charged a higher rent. This meant the Volkskrant building started to attract the type of creative professional that had more disposable income than the artists and musicians who had made up the majority of the tenants in the beginning. Gradually, design agencies, consultants and high tech start-ups started to rent workspace in the hub as well.

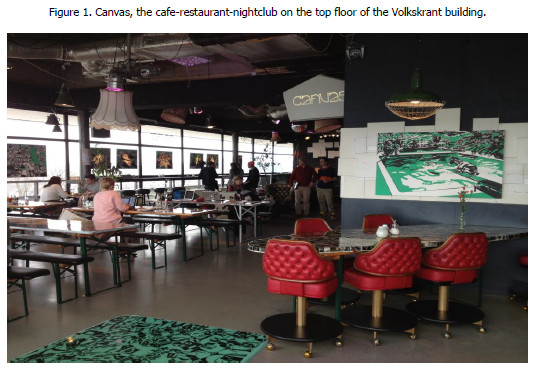

Altogether, up until the spring of 2013, the Volkskrant building comprised the offices and studios of more than 300 professionals in the cultural and creative industries. Among the tenants were charities and social initiatives, as well. The building was the second (and sometimes secretly the first) home to painters, musicians, sound engineers, dance teachers, writers, coders, graphic designers, independent project managers, architects, communication experts, filmmakers and journalists. The top floor was used by Canvas, a cafe and lunch spot by day and restaurant, nightclub and cocktail bar by night (see figure 1). It attracted a wide variety of customers and brought the creative work of the building accessible to larger audiences, for instance by hiring DJs who had their studios in the building, or by having their artwork done by graphic designers who were also tenants. Over the course of the six years that the Volkskrant building was run in this way, it became one of the most important hubs for the creative workforce of Amsterdam and perhaps even in the whole country.

The Volkskrant building as loose space

Many investment firms and governments strive to turn post-industrial urban sites and areas into cool and hip places, but what are these spaces actually composed of? Contrary to the images we may have of such places, the Volkskrant building did not have a very open appearance to visitors and passers-by. Its windows were blinded and there was no sign that announced the building’s function as you approached the façade. Nevertheless, the Volkskrant building was accessible for tenants at all times, so there was always a lot going on. There were meetings and social gatherings, parties and after-parties at art studios over the weekends. On an average day, one was likely to run into several loose dogs and encounter the occasional smell of marijuana in the hallways. While there was a vague awareness of office hours on most floors, the basement and fifth floor, mostly filled with musicians and artists, were most active at night time. Throughout the entire building, less than half of all workspaces would have their doors open. Many people used the common spaces of the building to make phone calls. The bad cell phone reception was not the only reason for this. Many freelancers sharing an office with other freelancers mentioned that the staircases, although they were used by other tenants, offered a type of privacy that their shared office did not. There were also some larger spaces which Urban Resort rented out as lecture halls to institutions of higher education close by, causing the building to be occupied by masses of students from time to time. On most days, there were hundreds of people using the premises, all in their different ways.

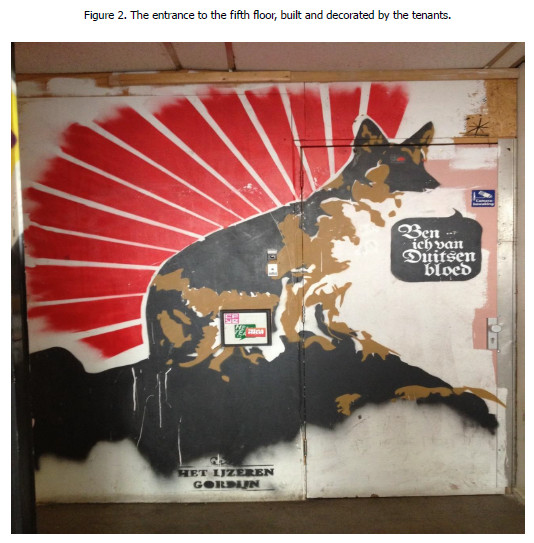

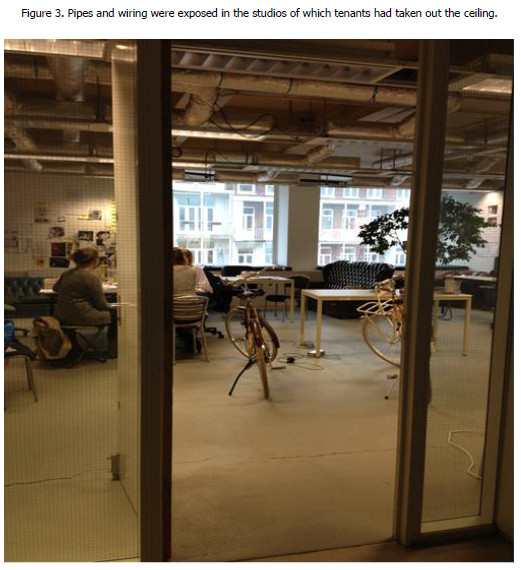

Urban space, work space and virtual space were constantly intertwining and informing one another in the Volkskrant building. Most of the creative professionals that we observed appropriated their allocated office space in a way or another. The artists working on the fourth floor had turned one toilet block into a kitchen, and the fifth floor had decorated the door giving entrance to their floor with extensive mural paintings (see figure 2). A collector of pianos put second hand furniture in the hallway in front of his studio in order to create a lounge for him and his neighbours, and many tenants took out the outdated ceiling systems in order to have a higher ceiling, albeit one with exposed pipes and wiring (see figure 3).

Then there were people who did not alter the physical space at all, but who played an active part in the city’s social-professional networks. Not only did the building facilitate meet-ups between the ex-squatters running it and the local politicians funding it, but the Volkskrant building also acted as a nexus amid many different types of professionals. If visual artists hosted parties, this would bring many of their peers to the building. Similarly, an office party thrown by a start-up would bring entrepreneurs from the entire Dutch software development scene to the place. But there were also events organised by a charity working to improve the lives of Somali immigrants, and they brought in a largely Somali crowd. In general, the creative industries are characterised by a high degree of mobility, thereby connecting various cultural spaces across the country and even globally (Kong 2014), and this is precisely what’s visible in the Volkskrant building. Over the years that it acted as a hub for creative professionals, its tenants were involved in initiatives that came to mark Amsterdam’s (underground) cultural life, such as music festivals Appelsap and Magneet, and performing arts festival De Parade. Musicians and DJs working in the building spread their wings out to many nightclubs around town, but also to venues across the globe (Cnossen & Olma, 2014). This shows that the building was more than a physical space. It was an ecology that linked cultural, alternative, creative and other types of spaces, both virtual and geographical, that reached all over town and far beyond.

Many researchers have underlined the importance of locality for the emergence of such ecologies. Place-based clusters of creative enterprises ensure that the collective aspect of creative production can happen easily, because enterprises are situated in the same area. This fits the dynamic, project-based type of working that is common for the creative industries (Grabher, 2001). An empirical study on the choice of creative enterprises for certain locations revealed the importance of other location-based externalities as well, such as the reputation of a certain neighbourhood, the fact that there was a “buzz”, or the presence of certain materials needed for certain products (Drake, 2003). Research into the preferences of professionals in the advertising industry in London revealed that proximity to other businesses was one of the main factors in choosing a location to set up a business (Clare, 2013). Furthermore, a study of cultural workers in the UK revealed this group has a strong desire to make a place interesting (Warren, 2014). So although creative professionals carrying around their laptops may see the entire city as their office, a preference for certain areas may find things such as atmosphere and buzz of vital importance. No matter how “open source” the city becomes, creative workers will build their temporary settlements somewhere and cluster together.

When asked how they felt about the fact that their studios were there only temporarily, quite a few of our interviewees mentioned that their lives were structured like that anyway. All of their work was precarious – project-based, lowly paid – and on top of that, most of these people were young who are known to have “flexible” private lives as well (I37, I47, I58). The tenants would habitually work on different projects at the same time which could be done on various locations, and they could also work from home. Some mentioned that living in Amsterdam was always defined by insecurity. A music producer lived in his studio for a while after he had to leave the room which he rented from a landlord who had become aggressive due to drug addiction (I58). A landscape architect lived in his work space in the Volkskrant building after his relationship ended (I16). A visual artist mentioned she did not feel like vacating her studio at all because her home was being renovated, causing her to temporarily live elsewhere (I49). These examples indicate that this population is used to moving in and out of houses and work spaces, and also that in Amsterdam, space is scarce.

As these brief examples demonstrate, the workspaces of the Volkskrant building have been used in a multitude of ways. They also have been heavily repurposed and appropriated according to their users’ wishes. Therefore we think the building is more than a mere place of work to the occupants. Conceptualising the creative hub of the Volkskrant building as a “Thirdspace” (Soja, 1996) allows us to analyse how the space is as much the canvas for people’s imagining of new creative and social practices as it is an actual physical space. Imagining space opens up the way for shaping it according to your own wants and desires, which puts the user of that space into the position of a maker or creator. Arguably, this is true for any space, but spaces, which aim to facilitate creative activities, might inspire its users to apply their creativity onto the physical environment even more. Urban Resort also actively stimulated tenants’ initiatives to alter the spaces they used, something which was a direct result of the squatting heritage that the organization brought to the building (Cnossen & Olma, 2014). That heritage also manifested itself in the tenants’ active participation in maintenance issues and the reluctance to “play by the book” concerning the use of communal areas.

Furthermore, many of the activities that were going in the Volkskrant building were not so much associated with work but rather with leisure, entertainment, self-expression or political expression, reflection and social interaction. In line with what Franck and Stevens have called “loose space” (2007, p. 3), these activities produce threshold spaces, in-between areas that relate rather than separate their users. Loose space employs the qualities of possibility, diversity and disorder, and can be understood through looking at places that are open to people’s own initiatives and actions as well as reinterpretation (Franck & Stevens, 2007, p. 17). Loose space can also be thought of as “third places” which sustain informal public socialisation (e.g. Oldenburg, 1991, p. 21), and, as we have suggested, it even echoes Thirdspace – originally a Situationist term – brought back into academic debate as a place in which “everything comes together […] subjectivity and objectivity, the abstract and the concrete, the real and the imagined” (Soja, 1996, p. 57).

Our aim is not to empirically prove the existence of such concepts nor to challenge them theoretically, but rather to pick up upon them in order to use them as a lens through which to make sense of our fieldwork. In this sense, we do believe the Volkskrant building can effectively been seen as a loose space. It was a mixed-use environment: people worked there, socialised, went for dinner or drinks and dancing at Canvas, or took classes with one of the many musicians or at one of the three dance studios in the building. Even though many urban spaces have the physical and social possibilities to be loose and open for appropriation, it is ultimately always up to people to grasp the possibilities and act upon them. The emergence of a loose space is far from self-evident, as it needs “first, people’s recognition of the potential within the space and, second, varying degrees of creativity and determination to make use of what is present, possibly modifying existing elements or bringing in additional ones” (Franck & Stevens, 2007, pp. 10–11). Temporary working spaces allowed themselves to be modified and appropriated as their users pleased. This resulted in the emergence of a new kind of space – a hybrid between private and public, personal and shared, professional and recreational.

As the workspaces in the Volkskrant building had been designed to be flexible and customisable from the start, it was an ideal place to study people’s engagement with their social surroundings and the working environment. In the design of computer-based applications and games the concept of engagement is being used to understand the user’s behaviour and level of investment in the programme in order to make them more appealing and attractive (O’Brien & Maclean, 2009). We argue that similar principle applies to its uses in urban design: by analysing how and through what kinds of practices people shape their environments it would be possible to indicate how to build a structure that supports commitment and positive interaction from the start. Furthermore, by looking at what kinds of choices people make in shaping their workspaces might add to our understanding of the needs of creative professionals. In order to get a grasp of these, we examined the incentives of people that rented workspaces in the Volkskrant building.

Towards creative ecosystems

So far we have shown how the flexible and mixed uses of the Volkskrant building went hand in hand with ongoing interactions of all kinds, and how this resulted in an inspiring place to work and pass time. The spatial negotiations of the tenants in the Volkskrant building should be understood in relation to the creative industries, and the rapid changes this part of the economy is undergoing (Hesmondhalgh & Baker, 2013, Friebe & Lobo, 2006). In reviewing the recent literature on these changes, we noticed the presence of metaphors drawn from biological discourse. In order to understand and further analyse the findings from our fieldwork, we will contextualise the social networks identified in the hub within the discourse of organic, creative ecosystems and ecologies.

Hearn, Roodhouse and Blakey (2007) use the term “value creating ecology” to describe the economics of the creative industries. The creative industries are characterised by a shift from thinking in product value to thinking in network value, they assert. Diverse and socially intense environments, often characterised as co-operative networks between entrepreneurs, consumers and creators, drive creativity and innovation. Hence, the value chain, a classic economic notion that stands for a linear, static and competitive model of value-creation, is outdated. In order to understand network value, we must take into account characteristics which economists have referred to as externalities, e.g. in the way the product is connected to other products, the atmosphere location were it is produced, and other seemingly uneconomic factors (Hearn et al., 2007, pp. 10–11).

In order to capture the characteristics of networks, a variety of organic metaphors have entered the stage. For example, Ward Thompson put forward the term “work ecology” in order to describe an organic ecosystem that brings many disciplines together to produce a dynamic, holistic view of the workplace and its relationship to its environment (Ward Thompson, 2002). Dvir and Pasher (2004, p. 18) claim that it is the work environment that supports a climate for innovation and that enables, fosters and encourages the generation of ideas and the creation of value out of them. Similar to Hearn et al., Howkins (2010) turns to biological discourse to describe new economic developments. He uses the term “creative ecology”, which he defines as “a network of habitats where people change, learn and adapt [...]. If we include resilience and sustainability, which is a system’s capacity to cope with disturbance and still retain its basic function, we have a good base to build on” (Howkins, 2010). The verbs “learning”, “changing” and “adapting” suggest processes of production that are not purely economic, but entail social aspects as well. This is what Olma refers to as the Topologisierung ökonomischen Raums, or the situation in which a typically economic space (for instance a commercial firm) becomes infused with other rationalities as well (Olma, 2011). He suggests that these new economic practices challenge the classic way of imagining the economy – where organisations are portrayed as entities in a nondescript void called the market – and propose new topologies of organising in which the social, the cultural, and the economic exist in the same spaces (Olma, 2007).

During our yearlong fieldwork at the Volkskrant building, we found that the relationships between people were very much tied up with the spatial set-up, but certainly not governed by the space. The social structures manifest in the building reflected how the spaces had been allocated – in the sense that immediate neighbours would have more day-to-day contact than people from different floors – but were also outcomes of the ongoing flexible uses and modifications of the spaces. The building was characterised by different communities of which only two were a continuation of the groups that had applied and been accepted at the launch of the creative hub in 2007. These communities shared knowledge, know-how, and sometimes actual work. But most of all, they were never static: people entered and left, communities connected with other communities in and outside of the building, and the building very much acted as a sort of climate or sphere within which creative work was performed and organised.

We observed that in the different types of uses of the Volkskrant building, the boundaries between living and working, producing and consuming, as well as the social and the professional spheres, were always challenged. It was also clear that the tenants of the Volkskrant building had a good understanding – conscious or not – of the potentials and threats of a creative ecosystem. From our first observations and interviews it emerged that most of them perceived the Volkskrant building as more than just a place to work. They often described the value that was added to their products – artworks, ideas, services and experiences – as shaped by their externalities, which seems to resonate with the argument proposed by Hearn, Roodhouse and Blakey (2007).

In 61 semi-structured interviews we conducted with tenants of the Volkskrant building, we asked our interviewees to elaborate on their reasons for renting space in the hub. After having collected all of our material we categorized these into four categories: (1) the overall feel or “energy” of the place, (2) the Volkskrant building as a brand and the effect of that on clients, (3) the benefit of having a workplace away from home, and (4) the value of the networks between people within the building. About 20 of our 61 interviewees emphasised the importance of the fourth category, meaning they valued networks within the building as crucial to their work and working processes. Just as with the concepts of loose space and Thirdspace, thinking in terms of an ecology, an ecosystem, allows for a sort of integrated view on how economic, social, artistic and recreational activities are not contained in separate categories, but how they all impact one another.

Some interviewees mentioned the location of the building, which was regarded important for buying materials (for those working with textiles or other physical components, e.g. I24), having clients visit by car or public transport (more established companies, e.g. I8), and rapid transfers to project meetings elsewhere (almost everyone). These findings shed light on how these working practices fit into ways of using urban space, i.e. using public transport versus cycling, meeting with people, having access to resources. This illustrates, again, that the boundaries between work space, private space and public space are blurry, and how there are continuous processes of interaction between the different spaces and the ways they are appropriated to their users’ needs. How exactly these processes of interaction worked, however, were only discovered through a serendipitous occurrence during the period of our participatory observation.

Becoming the Volkshotel

In 2011, a former IT entrepreneur bought the Volkskrant building for a sum far above its estimated value with the financial support of one of the most important property investors of the Netherlands. His plan was to turn the building into a “creative hotel” aimed at an international, arts-minded audience, and as of July 2014, it has become exactly this. A third of the building, which is now called Volkshotel, still houses artist studios and workspaces for creative workers, and this section is still managed by Urban Resort, who now work for the new owners. The rest of the building is used as a hotel, which has several rooms and suites designed by people who still rent a studio in the building. Canvas, the club and restaurant on the top floor, has been expanded into a two-story club with jacuzzis on the rooftop. The basement has a jazz bar with a 24-hour license, enabling travellers coming from different time zones – or locals in different stages of their creative process – to have a cocktail whenever they want to. In this last section of this article we describe the events leading up to this change and indicate at which points we think these events are indicative of the type of engaged space-shaping practices we have outlined so far.

Upon their purchase of the Volkskrant building, the new owners established partnerships with both Canvas, which had become quite successful over the years, and the managing organisation Urban Resort. The new owners asked Urban Resort to inquire whether the tenants would be willing to either move into a smaller studio in order to make space for the hotel rooms in the building, or vacate from the building altogether in exchange for financial compensation. Most rental contracts of the Volkskrant building would expire in 2014, but the new owners wanted to start their construction work in 2013 and therefore needed the cooperation of the tenants. In September 2012, the new owners with the help of Urban Resort did an investigation among all 185 legal tenants. This took on the shape of meetings, held with groups of tenants from different floors. Often people would bring the people they shared a workspace with, even if they would not hold a rental contract.

At these meetings, during which one of the authors was allowed as an observer, the new owner would present his plans and explain the need for cooperation from the broedplaats tenants in order to commence construction prior to the expiration date of their rental contracts. These meetings and the other events taking place as a result of the remodelling plans provided an excellent laboratory to observe the workings of creative ecosystems. We theorised that if people really functioned within a creative ecosystem – i.e. if they understood the added value of social exchanges for their economic output and had an attitude of contribution towards their community – they would try to adept that social collective to the changing circumstances. This is exactly what happened, and the strategies used for this revealed the levels of engagement of the tenants, which in this specific course of events concretely effected the spatial reconfigurations of the building.

Unsurprisingly, those who most valued their spaces in the Volkskrant building – whether it was just their own studio or the shared spaces with their neighbours and collaborators – turned out to be the most critical towards the new owners’ plans. A group of tenants from the second floor got together and wrote a letter in which they stated they would stay as long as their rental contract allowed them to, and would not cooperate with an earlier transition. This group consisted of a mixture of internet entrepreneurs and creatives. This “conspiracy” quickly dispersed into single elements once it became clear that each of them had very different positions when it came to the level of investment they had put into their workspace, their willingness to pay a higher rent elsewhere, and their ability to negotiate with the new owners. Most importantly, these people did not rely on one another to add value to their work practices.

The most enduring sounds of protest against the renovation plans were provided by groups of tenants from the fourth and sixth floor. They managed to mobilise their communities in order to collectively negotiate with the new owners, and to articulate the values of their group along the way, which we were able to observe. The fourth floor was the only one selecting new tenants during the transition. A female illustrator (I50) had had a studio there since the beginning and initiated the construction of a kitchen for the entire floor: “I got to know the other people very well through that building project, and of course it’s not something you do if you plan to leave within a year.” The fourth floor tenants insisted on speaking to the new owners as a group. Among them was a theatre set designer who expressed how she felt the knowhow of creative places that was already present was not being recognised: “[The new owner] wants to create a Berlin-like place. Well, I work there a lot and you cannot compare it to here. Rents are much lower, there is more space available. Their plan might work for people who work on laptops, but we need space. It feels as if that which has been made by us is now being used by them” (I35). The “we” to which this respondent refers is a specific group of people on the fourth floor, consisting of set designers, fashion designers and visual artists, who all need a significant amount of space for experimentation with and storage of their materials. What we see here is a group whose creative practices and usage of space coincided: many of them were working with physical material, many of them shared space and some of them had even built the kitchen together. Their engagement with their shared work space led to an awareness of what they would miss should they have to move.

Although very conscious of their value to the Volkskrant building, and convinced that their group was worth more than the sum of its parts, the fourth floor artists eventually did not manage to speak with one voice throughout the processes of negotiation. In conversations we had with them, they indicated separately from one another that the point of no return was when they had a meeting on their floor to discuss a collective strategy, which was being interrupted by phone calls from the new owners to urge them to make individual choices as to whether they wanted to stay in the building or not. Some people agreed to cooperate with the plans for the hotel, and this naturally undermined their collective acting power. Eventually, many tenants of this group strategically signed for co-operation because they figured that if everyone said they wanted to stay, no smaller broedplaats or creative hub could be created anyway, and everything would remain the same or would at least get delayed. The fact that the fourth floor artists valued each other’s feedback and company turned into their willingness to share a smaller space together. A positive outlook on this might be that although their group included fewer people than they themselves thought at first, those who were motivated enough to stick together were able to adapt to changing circumstances and would continue to function. On the other hand, as the group’s needs for appropriating work spaces were not met, they eventually dispersed.

A more recently conceived creative community of collaborators was situated on the sixth floor. Independent filmmakers and editors had moved there together from another creative hub in the city, joined by a duo of a photographer and another film editor later on. They divided a large space into different sections so that they could each have their own studio, but could still collaborate very easily. In their meeting with the new owners, they did not only express their concern about the effect that the construction would have on their work, but also stressed the importance of collective effort in making a creative space of particular value. A male filmmaker (I61): “When you say that the creativity of this building will stay, you have to acknowledge that that has emerged organically, and that you will disrupt that”. When the new owner mentioned the option of a lower rent for artists in exchange for an effort for the creative hub from their side, this was met with much protest. A female illustrator (I50) said: “If those things don’t happen spontaneously, it won’t work at all.” The filmmaker said: “When we organise a documentary night we don’t do that for bloody tourists. It has to be ours. The way you put it in your letter, sounds as if we are puppets in your show, while we have actually created it” (N1). Similar to the group of the fourth floor, this group demonstrated an ongoing engagement not just with their work or with the friendly atmosphere that characterised their group, but with the ways in which these two things were linked to, and constituted by, the use of their shared space, for instance by building their own studios upon moving into the building.

Although some of its members moved out of the building, the largest part of this group managed to negotiate to having work spaces in the new broedplaats close to one another. They were also given additional possibilities for financial compensation during construction works and these new regulations apply to all tenants now. They articulated the benefits they got from working in close proximity of one another, as well as the value this provided to the broedplaats and eventually the creative scene of the city, and thereby managed to adapt to the transformation. At the same time, one must admit that these self-employed creative workers had little agency in choosing their new environment. Nevertheless, the limited agency that they had did emerge from the fact that they could show how they had shaped the spaces of the building into something worthy of the attention of property investors.

The self-acclaimed “nerds” from the second floor provided another example of a recently conceived and fast-evolving community. From 2010 onwards, some of them started by renting desk space in the office of an independent computer coder, after which they went on to rent their own space on the same floor. Many of these start-ups hired coders or designers who also worked on the second floor, turning this section into a living room-like environment where wearing shoes was considered unnecessary. These companies moved at a rapid pace, needing extra space one month, perhaps dying out the other. They benefited from flexible, low-rent spaces because it allowed them to keep expenses low. On the basis of interviews, it turned out that place was important to them for other reasons as well: “For us this place really works. We have a great atmosphere in which it is very easy to ask each other questions”, a male entrepreneur said (N2). A user experience designer whose expertise entailed using technology for cultural purposes, confirmed it that mixing the arts with more technological professions worked well: “Why do you think these developers are here? Of course they want to be part of a fun and creative place. They might work for large American companies, but I think they easily leave to do something more fun”, she said (N3).

The second floor nerds have since set up their workspace in the centre of Amsterdam. Their network has grown exponentially, attracting start-ups and independent coders and engineers from different nationalities. Their story is a good example of how a network which rather coincidentally came into being in the Volkskrant building, lived on to grow elsewhere in the city. By making serious attempts to organise the collective, a loose network of collaborators acknowledged that the value of their group went beyond being a group of friends. At the same time, they distanced themselves from more formal incubator spaces aimed specifically at the technology sector, because they wanted to maintain the infusion of their economic space with their own social and cultural elements. In the building they work in now, they have a backyard where they can have barbecues, and an unlicensed cocktail bar in a storage cupboard below the staircase. This way of shaping their work space is as much the result of their personal economies (the fact that they have decent wages) as it is of their social practices (they enjoy spending time together). Their space-making feeds back into their ways of working and socialising.

The last community we identified through the observation of this strategic process in which the creative hub became the Volkshotel, was perhaps the most complicated one. It existed between the fifth floor, various musicians who were located at different spots in the building (most importantly in the basement), and the nightclub Canvas. The latter acted as the centre: many musicians had DJ-ed there over the years and many of the creatives had been involved in programming or styling events. Starting out at Canvas some DJs were able to make the step to larger venues such as Trouw. A male DJ and event organiser who had an office in the Volkskrant building stressed the importance that Canvas has had for this loosely knit but very sociable network: “All producers and programmers [in Amsterdam] have been involved with Canvas and the Volkskrant building, whether directly or indirectly” (I22). Interestingly, although this group had a very strong sense of their value to the place, they were far from opposed to the investors’ plans of turning the building into a hotel. Very early on in the negotiation process, they said to be willing to move into different studios if necessary and to cooperate in whichever way needed to remain part of the place. Factoring into this attitude was the fact that many of them were hired by the new owners, whether it was to provide artwork for flyers, make a website, design a room or perform at events.

Even though their interactions and negotiations in this transformation went relatively smoothly, certain power dynamics were involved in the process. In the end, these young, recent art school graduates had to wait and see whether the new owner would still grant them studio space which was effectively funded by the revenue from the hotel, since the Volkshotel would not fall under the broedplaatsen policy any more. Interestingly though, and without denying these power dynamics, their creative work and continued presence in the building – whether for work or socialising – has had an impact on how this hybrid “creative” hotel now performs and functions.

Conclusions: Reconfigurations of urban space

We started this article by showing how the Volkskrant building was shaped by the local heritage of the squatter movement, which is an important part of the recent history of Amsterdam (Soja, 2000). The organisation which set up the broedplaats in the Volkskrant building in the first place and is still managing a section of the Volkshotel, Urban Resort, was founded by people who were active in the squatter scene of the 1980s. This heritage was most concretely visible in the fact that Urban Resort gave the tenants of the Volkskrant building the ability – and responsibility – to alter the physical space in order to make it their own, and to save on overhead costs. The Volkskrant building tenants mixed business and pleasure and brought people to the building for parties and projects. This, combined with the fact that people often worked in different places at the same time, and that tenants swiftly moved in and out of the building, turned the building into a nexus for the Dutch creative industries.

The history of the creative hub in the Volkskrant building has shown how grassroots-level squatting practices eventually led to the setup of creative hubs for workers in the creative industries whose practices are characterised by flexibility, mobility, and a mix of professional, social and recreational practices. Conducting intensive fieldwork in this building allowed us to understand the relationship between space and creative and social practice as a continuous iterative process, in which the former is always an outcome of the latter instead of a static given. We have conceptualised this processual relationship drawing on the notions of loose space and Thirdspace.

Our fieldwork revealed the importance of social atmosphere to those working in a creative hub. This social atmosphere may be paired with, or lead to, professional collaborations, but this was not necessarily the goal of tenants. Following the transformation of the hub into the Volkshotel, the economic value of this social atmosphere was revealed in the ways in which groups of tenants who knew each other and valued their exchanges and collaborations were able to impact the ways in which the Volkshotel was eventually set up. Whether this was to do with the allocation of the new studio space, or the interior design of the hotel rooms, the tenants who were responsible for this put up with a long period of inconveniences due to construction works, since they really wanted to stay as members of the community they felt they belonged to.

We have read this mixture of flexible working practices combined with sociality in relation to the recent literature on how creativity changes the economy, articulated through the notions of ecology and ecosystem, in order to understand these changes. By observing the social practices of the tenants and inquiring about their motivations to stay in or leave the Volkskrant building during its transformation into the Volkshotel, we have shown how these communities formed into creative ecosystems. By trying to hold their community together (or even expand it) under challenging circumstances, people recognised the value that this networked sociality had to their professional as well as private lives. In the end, some of the groups we identified moved out of the building in order to continue elsewhere, while others stuck together and are now tenants of the Volkshotel.

In sum, the Volkskrant building is a perfect example of engaging with and shaping of one’s own environment, even if this shaping does not always take place in concrete terms, with construction materials and tools. Rather, the shaping of space existed in the fact that seemingly loose networks of friends or occasional collaborators suddenly realised not only how valuable their “spatial organisation” (i.e. working in close proximity) was, but also, and most importantly, that they had the power to act on it. We have proposed that the term engagement would be useful in understanding these informal ways of shaping urban work-related spaces. As we have shown in this article, the collective navigation and appropriation that these creative ecosystems have gone through, resides somewhere between organised collectivity and the ad-hoc communality echoing the spirit of social media.

In today’s world, the reconfiguration of the urban space and its politics are being actively imagined and enacted through the production and dissemination of technological fantasies that dissect the urban worker from the physical workplace and downplay the importance of real-life social networks in the construction of a work identity (Georgiou, 2013). The ideal labourer of the information age seems to be a creative individual whose work is project-based, detached, mobile and very flexible time- and space-wise. However, unlike what the hype proclaimed in the 1990s and 2000s, digital media are increasingly tied to the material and architectural preconditions they add to (Graham, 2001). As our analysis shows, there are important reasons for creative workers to form alliances and fluid ecosystems with their co-workers and colleagues in precarious positions: in that way, they may just be able to negotiate better deals with corporate partners.

In the case of the Volkskrant building, many of the tenants who ended up staying in the Volkshotel asserted a position of power which was not officially granted to them. But by claiming (partial) ownership of the place they had helped shape, they have continued to influence the set-up of the Volkshotel until this day, whether making sure they share a studio space with their collaborators, DJ-ing during an event, or coming up with the design for the hotel rooms. The examples we have provided of actively changing one’s physical (work) environment would not have been possible without face-to-face contact and a shared sense of the everyday reality of being a creative worker. As such, our study reveals the inseparability of virtual interconnectedness and the physical, lived, day-to-day reality.

References

Interviews

I8. Interview with two male IT entrepreneurs. The Volkskrant building, 24-07-2012.

I16. Interview with a male landscape architect. The Volkskrant building, 06-08-2012.

I22. Interview with a male DJ and event organiser. The Volkskrant building,16-08-2012.

I24. Interview with a female fashion designer. The Volkskrant building, 26-08-2012.

I35. Interview with a female theatre set designer. The Volkskrant building, 27-09-2012.

I37. Interview with a female graphic designer. The Volkskrant building, 10-10-2012.

I47. Interview with a female performance artist. The Volkskrant building, 15-11-2012.

I49. Interview with a female visual artist. The Volkskrant building, 29-11-2012.

I50. Interview with a female illustrator. University of Amsterdam, 08-01-2013.

I58. Interview with a male music producer. The Volkskrant building, 18-01-2013.

I61. Interview with a male filmmaker. The Volkskrant building, 21-01-2013.

Excerpts from field notes

N1. Notes from meeting. The Volkskrant building, 03-10-2012.

N3. Notes from informal conversation. The Volkskrant building, 03-02-2013.

N3. Notes from informal conversation. The Volkskrant building, 10-03-2013.

Literature

Arora, A., Belenzon, S. & Rios, L.A (2014). Make, buy, organize: the interplay between research, external knowledge, and firm structure. Strategic Management Journal, 35(3), 317–337.

Breek, P. & De Graad, F. (2001). Laat duizend vrijplaatsen bloeien. Onderzoek naar vrijplaatsen in Amsterdam. Amsterdam: De Vrije Ruimte. [ Links ]

Carmona, M., Heath, T., Oc, T. & Tiesdell, S. (2003). Public places, urban spaces. The dimensions of urban design. Oxford: Architectural Press. [ Links ]

Clare, K. (2013). The essential role of place within the creative industries: boundaries, networks and play. Cities, 34(1), 52–57.

Cnossen, B. & Olma, S. (2014). The Volkskrant building: manufacturing difference in Amsterdam’s creative city. Amsterdam: Amsterdam Creative Industries Publishing.

Crang, M. & Graham, S. (2007). Sentient cities: ambient intelligence and the politics of urban space. Information, Communication and Society, 10(6), 789–817. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/13691180701750991

De Jong, V. (2012). Nodes of creativity: unlocking the potential of creative SME's by managing the soft infrastructure of creative clusters. Master’s Thesis, Cultural Economics and Cultural Enterpreneurship, Erasmus University Rotterdam, the Netherlands. Retrieved from: http://thesis.eur.nl/pub/12771

Drake, G. (2003). “This place gives me space’: place and creativity in the creative industries. Geoforum, 34(4), 511–524.

Dvir, R. & Pasher, E. (2004). Innovation engines for knowledge cities: an innovation ecology perspective. Journal of Knowledge Management, 8(5), 16–27.

Eigenraam, A. (2013, September 12). Leegstand van Nederlandse kantoren is hoogste in Europa. NRC Handelsblad. Retrieved from http://www.nrc.nl/nieuws/2013/09/12/leegstand-van-nederlandse-kantoren-is-hoogste-van-europa/

Fayard, A. & Weeks, J. (2011). Who moved my cube? Harvard Business Review. Retrieved from https://hbr.org/2011/07/who-moved-my-cube

Florida, R. (2005). Cities and the creative class. New York, NY: Routledge.

Florida, R. (2014). The rise of the creative class: Revised and expanded. New York, NY: Basic Books.

Franck, K. A. & Stevens, Q. (2007). Tying down loose space. In Franck, K. A. & Stevens, Q. (eds.) Loose space. Possibility and diversity in urban life. London: Routledge. [ Links ]

Friebe, H. & Lobo, S. (2006). Die digitale Boheme oder: intelligentes Leben jenseits der Festanstellung. München: Random House. [ Links ]

Gertler, M. S. (2004) Creative cities: what are they for, how do they work, and how do we build them? Background Paper F|48, Family Network. Canadian Policy Research Networks.

Georgiou, M. (2013). Media and the city: Cosmopolitanism and difference. Cambridge: Polity. [ Links ]

Gibson, C., C. Brennan-Horley, B. Laurenson, N. Riggs, A. Warren, B. Gallan and H. Brown (2012). Cool places, creative places? Community perceptions of cultural vitality in the suburbs. International Journal of Cultural Studies, 15(3), 287–302.

Grabher, G. (2001). Ecologies of creativity: the Village, the Group, and the heterarchic organisation of the British advertising industry. Environment and Planning, 33(2), 351–374.

Graham, S. (2001). Information technologies and reconfigurations of urban space. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 25(2), 405–410. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/1468-2427.00318

Hearn, G. N., Roodhouse, S. & Blakey, J. M. (2007). From value chain to value creating ecology:Implications for creative industries development policy. International Journal of Cultural Policy, 13(4), 419–436.

Hesmondhalgh, D. & Baker, S. (2011). Creative labour: media work in three cultural industries. New York, NY: Routledge.

Howkins, J. (2010). Creative ecologies., London: Transaction Publishers. [ Links ]

Howkins, J. (2013). The creative economy (revised). London: Penguin Books. [ Links ]

Karim, S. & Mitchell, W. (2004). Innovation through acquisition and internal development: A quarter-century of boundary evolution at Johnson & Johnson, Long Range Planning, 37(6), 525–547.

Keizer, F. (2014). Autonomy by dissent: EHBK/OT301. Amsterdam: Abnormal Data Processing. [ Links ]

Kong, L. (2014). Transnational mobilities and the making of creative cities. Theory, Culture, Society, 31(7/8), 273–289.

Landry, C. (2006). The art of city making. London: Earthscan Publications. [ Links ]

Landry, C. (2008). The creative city: a toolkit for urban innovators. London: Earthscan Publications. [ Links ]

Lange, B., Kalandides, A., Stoeber, B. & Mieg, H. A. (2008). Berlin's creative industries: governing creativity? Industry & Innovation, 15(5), 531–548.

Lawton, P., Murphy, E. & Redmond, D. (2012). Residential preferences of the “creative class’? Cities, 31(2), 47–56. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.cities.2012.04.002

Markusen, A. & Gawda, A. (2010). Creative Placemaking. National Endowment for the Arts. Retrieved from http://kresge.org/sites/default/files/NEA-Creative-placemaking.pdf

Miazzo, F. & Kee, T. (2014). We own the city: enabling community practice in Amsterdam, Hong Kong, Moscow, New York and Taipei. Amsterdam: Transcity. [ Links ]

Miles, M. (2005). Interruptions: testing the rhetoric of culturally led urban development.Urban Studies, 42(5/6), 889–911.

Nathan, M. (2007). Wrong in the right way?: creative class theory and city economic performance in the UK. In Geert Lovink & Ned Rossiter (eds.). My Creativity Reader: A Critique of Creative Industries. Amsterdam: Institute of Network Cultures. [ Links ]

O’Brien, H. L. & Maclean, K. E. (2009). Measuring the user engagement process. CHI 2009, 4–9 April, Boston.

OECD 2014. Addressing the tax challenges of the digital economy. DOI:10.1787/9789264218789- en

Oldenburg, R. (1991). The great good place: cafes, coffee shops, community centers, beauty parlors, general stores, bars, hangouts, and how they get you through the day. New York, NY: Paragon.

Olma, S. (2007). Vital organising: capitalism’s ontological turn and the role of management consulting. Unpublished doctoral thesis, Goldsmith's College, University of London, United Kingdom.

Olma, S. (2011). Die Topologisierung der Werterschoepfung: Ursprunge, Widerstaende und der empirische Fall betahaus. In Bergmann, M. & Lange, B. (eds.). Eigensinnige Geographien: Staedischen Raumaneigenungen als Ausdruck gesellschaflicher Teilhabe. Wiesbaden: VS Verlag. [ Links ]

Peck, J. (2012). Recreative city: Amsterdam, vehicular ideas and the adaptive spaces of creativity policy. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 36(3), 462–485.

Peters, M. A. (2010). Three forms of the knowledge economy: learning, creativity, and openness. British Journal of Educational Studies, 58(1), 67–88.

Pierce, J.L., O’Driscoll, M.P. & Coghlan, A. (2004). Work environment structure and psychological ownership: the mediating effects of control. The Journal of Social Psychology, 144(5), 507–534.

Pohl, T. (2008). Distribution patterns of the creative class in Hamburg: openness to diversity as a driving force for socio-spatial differentiation? Erdkunde, 62(4), 317–328.

Pot, M. (2011). Amsterdam’s creative breeding places. Similarities and differences regarding motivations, goals and practices of different actors engaged in the realisation of broedplaatsen. Master’s Thesis, Urban Geography, Utrecht University, the Netherlands. Retrieved from: http://dspace.library.uu.nl/handle/1874/209166

Pratt, Andy C. (2008). Creative cities: the cultural industries and the creative class. Geografiska annaler: Series B – Human geography, 90(2). 107–117.

Soja, E. (1996). Thirdspace: journeys to Los Angeles and other real-and-imagined places. Oxford: Basil Blackwell. [ Links ]

Soja, E. (2000). The stimulus of a little confusion, a contemporary comparison of Amsterdam and Los Angeles. In Deben, L. (ed.). Understanding Amsterdam, Essays on economic vitality, city life and urban form. Amsterdam: Het Spinhuis. [ Links ]

Stankevičienė, J., Levickaitė, R.,Braškutė, M. & Noreikaitė, E. (2011). Creative ecologies: developing and managing new concepts of creative economy. Business, Management and Education, 9(2), 277–294.

Stavrides, S. (2008). Heterotopias and the experience of porous urban space. In Franck, K. A. & Stevens, Q. (eds). Loose space. Possibility and diversity in urban life. London: Routledge, 174–192.

Vannini, P. (2008). Situatedness. In Given, L. (ed.). The Sage Encyclopedia of Qualitative Research Methods. Thousand Oaks: Sage. [ Links ]

Van de Geyn, B. & Draaisma, J. (2009). The embrace of Amsterdam’s creative breeding ground. In Porter, L, Shaw, K. (Eds). Whose Urban Renaissance? An International Comparison of Urban Regeneration Strategies. New York: Routledge.

Van den Berg, M. (2014). Stedelingen veranderen de stad. Amsterdam: Trancity. [ Links ]

Van Zoelen, B. (2012). “Actieplan tegen hoogopgelopen wachttijd”. Het Parool, August 22. Retrieved from http://www.parool.nl/parool/nl/6/WONEN/article/detail/3304633/2012/08/22/Actieplan-tegen-hoog-opgelopen-wachttijd-sociale-huurwoning.dhtml

Warren, S. (2014). “I want this place to thrive’: volunteering, co-production and creative labour. Area, 64(4), 278-284.

Ward Thompson, C. (2002). Urban open space in the 21st century. Landscape and Urban Planning, 60(2), 59–72.

Wolsink, L. (2014). Broedplaatsen in het cultureel ecosysteem van het Oostenlijk Havengebied en de Czaar Peterstraat: stedelijke ontwikkeling door middel van cultuurbeleid. Master’s Thesis, Art and Culture Studies, Erasmus University Rotterdam, the Netherlands. Retrieved from http://thesis.eur.nl/pub/17980/

Yigitcanlar, T. & Martinez-Fernandez, C. (2007). ““Making space and place for knowledge production: knowledge precinct developments in Australia’’, Proceedings of the State of Australian Cities 2007 National Conference, University of South Australia and Flinders University, Adelaide, 83–140.

NOTES

1 With the exception of figure 4, all figures used in this article are photographs taken by one of the authors.