Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Acessos

Acessos

Links relacionados

-

Similares em

SciELO

Similares em

SciELO

Compartilhar

Observatorio (OBS*)

versão On-line ISSN 1646-5954

OBS* vol.9 no.2 Lisboa jun. 2015

Into the Groove - Exploring lesbian and gay musical preferences and 'LGB music' in Flanders

Alexander Dhoest*, Robbe Herreman**, Marion Wasserbauer***

* PhD, Associate professor, 'Media, Policy & Culture', University of Antwerp, Sint-Jacobsstraat 2, 2000 Antwerp (alexander.dhoest@uantwerpen.be)

** PhD student, 'Media, Policy & Culture', University of Antwerp, Sint-Jacobsstraat 2, 2000 Antwerp (robbe.herreman@uantwerpen.be)

*** PhD student, 'Media, Policy & Culture', University of Antwerp, Sint-Jacobsstraat 2, 2000 Antwerp (marion.wasserbauer@uantwerpen.be)

ABSTRACT

The importance of music and music tastes in lesbian and gay cultures is widely documented, but empirical research on individual lesbian and gay musical preferences is rare and even fully absent in Flanders (Belgium). To explore this field, we used an online quantitative survey (N= 761) followed up by 60 in-depth interviews, asking questions about musical preferences. Both the survey and the interviews disclose strongly gender-specific patterns of musical preference, the women preferring rock and alternative genres while the men tend to prefer pop and more commercial genres. While the sexual orientation of the musician is not very relevant to most participants, they do identify certain kinds of music that are strongly associated with lesbian and/or gay culture, often based on the play with codes of masculinity and femininity. Our findings confirm the popularity of certain types of music among Flemish lesbians and gay men, for whom it constitutes a shared source of identification, as it does across many Western countries. The qualitative data, in particular, allow us to better understand how such music plays a role in constituting and supporting lesbian and gay cultures and communities.

Keywords: Lesbian and gay; Music; Preference; Flanders; Identity

Introduction

There is a lot of anecdotal evidence connecting certain music and artists to gay and lesbian culture. For instance, in Belgium and the Netherlands, annually a top 100 list of 'gay and lesbian' music is drawn up, with ABBA's Dancing Queen as a perpetual favourite (see http://www.homotop100.be/ and http://homo100.bnn.nl/). There is also an entry on 'Gay and Lesbian Music' in the key encyclopedia on music, the New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians, discussing divas like Judy Garland and Madonna, among others (Brett & Wood, 2001). Although a lot of academic research has explored the importance of music in lesbian and gay cultures, as will be illustrated below, studies on the individual musical preferences of lesbians and gays are scarce, particularly outside the Anglo-Saxon world. Hence, statements about music tastes in lesbian and gay culture are often made on a more abstract and collective level, leaving aside questions about the meanings attached to certain music by individuals.

The purpose of this article is to start filling this gap by exploring the musical preferences of a broad cross-section of Flemish (North-Belgian and Dutch-speaking) LGBs (lesbians, gays and bisexuals), and to discuss the (perceived) connections of these individual preferences to broader LGB culture.1 In a preparatory stage, we used a quantitative survey to get a first view on their patterns of musical preference. In the main stage of the project, based on in-depth interviews, the connections between these musical preferences, gender and sexuality were explored. Two issues, in particular, were discussed in-depth in order to better understand the reasons for certain music preferences and the specific LGB meanings attached to this music: the importance of the musicians' sexual orientation (music by lesbians and gays); and the importance of music associated with lesbians and gays (music perceived as lesbian and gay). By exploring these issues, we aimed to get a better view on the ways in which gay and lesbian cultures and communities are constructed and supported through music.

Our analysis focuses on contemporary musical preferences, but before we start, it is necessary to review the literature in order to better understand the connections between music, music tastes, and lesbian and gay cultures. As the literature on lesbian and gay culture in Belgium is extremely limited and hardly makes any reference to music at all, we start by discussing the more established Anglo-American literature on this topic.

Music and the constitution of lesbian and gay cultures

Music has consistently been important in the construction and evolution of Western lesbian and gay cultures. These “collectivities of lesbian and gay life organized around erotic identity” (Irvine, 1994) started to develop at the end of the 19th century in several larger American and European cities (d’Emilio, 1983; Chauncey, 1994). Over the years, subcultural meeting places gave way to lesbian and gay bars. This ‘scene’ expanded remarkably from the 1960s onwards with the development of the lesbian and gay movement and often made a distinction based on sex, leading to separate lesbian and gay cultures (e.g. Davis & Lapovsky Kennedy, 1986; Haslop et al., 1998; Jennings, 2006; Moore, 2001). Hellinck (2004, 2007), one of the few historians writing about LGB culture in Belgium, comes to similar conclusions.

Music contributed to the evolution of lesbian and gay cultures on several levels. Both a powerful and expressive everyday medium and part of a sophisticated system of subcultural meanings (Chauncey, 1994; Davis & Lapovsky Kennedy, 1986), it not only provided means to meet other lesbians and gays, whether on the streets, in public or private meeting places, but it also contributed to the creation of a sense of belonging to a community and the construction of lesbian and gay identities (e.g. Chauncey, 1994; Taylor, 2012). Indeed, several scholars in the emerging lesbian and gay or queer subfield of musicology and popular music studies have written about the polysemic nature of music and the possibility to read it from different perspectives, including lesbian or gay ones (Brett et al., 1994; Taylor, 2012; Whiteley & Rycenga, 2006). These readings disclose the existence and importance of shared codes associated with lesbians and gays, which Irvine (1994) considers a significant component in talking about ‘lesbian and gay cultures’.

In these lesbian and gay reading processes, various components can be taken into account. For instance, the sexual orientation of the artist can give music a gay or lesbian meaning to knowing audiences (Chauncey, 1994; Lareau, 2005; Valentine, 1995). Subcultural and often gender-related codes also play a crucial role in such processes of 'decoding' lesbian and gay culture. Camp is a prime example in this respect, as a set of ‘effeminate’ subcultural codes, shared especially by gay men. Camp can be considered as a sensibility, connected to gay culture and characterized by a predilection for style for style’s sake (Dyer, 2002) and ‘failed taste’ (Ross, 2002). According to Booth (2002), camp bespeaks a commitment to the marginal, that is “the traditionally feminine, which camp parodies in an exhibition of stylised effeminacy” (p. 69). Several ‘gay icons’, like Judy Garland (before gay liberation in the late 1960s) or, more recently, Lady Gaga are associated with camp (Cohan, 2005; Jennex, 2013). Some of them, mostly women, are also known as divas: spectacular strong personae with a performative extravagance (Farmer, 2005). In a musical context, camp can be identified not only at the level of the performer and their stage performance; it is also audible through lyrics and musical execution. According to Jarman-Ivens (2009), three auditive criteria play a role in musical camp: exaggeration, flamboyance and playfulness.

While camp taste and diva worship are mostly linked to gay culture, lesbian culture is more likely to be associated with women’s music. This genre came up in the 1960s and is defined originally as “music by women, for women about women and financially controlled by women” (Lont, 1992, p. 242). Women’s music consists of a plethora of genres and styles (Rodnitzky, 1999), but historically ‘alternative’ genres like punk, folk and rock have been more prevalent than others (Whiteley, 2000). Again, gender codes come into play, as some of these genres have been perceived as ‘masculine', especially in relation to their so called opposite, namely commercial and mainstream popular music (Bayton, 1992, p. 52; Frith & McRobbie, 1978). According to Biddle & Jarman-Ivens (2007, 1-20) both musical (e.g. the sound) and non-musical codes (e.g. the performance) are at work in the gendering of this music.

The gay and lesbian movement paved the way for these gay and lesbian ‘scenes’ to expand and become more visible. From the 1960s onwards more bars, clubs, discos and other meeting places for gay men and women were founded, where older shared codes were given new meanings. For instance, as argued by Dyer (1998), disco had its roots in capitalism, but its musical and ideological characteristics are linked to gay culture: “It is a ‘contrary’ use of what the dominant culture provides, it is important in forming a gay identity, and it has subversive as well as reactionary implications” (p. 410). Although dance music has evolved drastically since then, it does remain particularly important for contemporary gay audiences. For instance, the ethnographic studies of both Amico (2001) and Buckland (2002) demonstrate that dance music can be one of the necessary factors in the making of a male ‘queer world’.

From the 1990s onwards, LGB culture has become even more visible in mainstream media and music. In the process, many of the subcultural codes discussed above have gained widespread recognition, such as camp in the context of the Eurovision Song Contest (Lemish, 2004; Singleton et al., 2007). Scholars have continued to explore the connection of certain music to LGB culture. For instance, research on contemporary musicians like Madonna, Lady Gaga, and kd lang demonstrates the importance of certain artists in lesbian and gay culture as well as in the identity formation and self-acceptance of LGBs, not least because they openly and purposefully explore their sexuality, stand up for LGBT rights, and incorporate diverse forms of femininity and masculinity in their work and performance (Clifton, 2004; Fouz-Hernandez & Jarman-Ivens, 2004; Horn, 2012; Kourtova, 2012; Leibetseder, 2012; Valentine 1995).

While the above account shows that much has been written about the importance of music in lesbian and gay culture, most of this research focuses on Anglo-Saxon cultures, which is why our focus on Flanders, where the authors live and work, offers a novel perspective. Although Flanders (and Belgium more generally) is one of the international forerunners in terms of LGBT rights and legislation (Borghs & Eeckhout, 2010), its lively LGBT culture has hardly been studied to date. Hence, the first aim of this paper is to explore the importance of music in lesbian and gay culture in the Flemish context.

Moreover, a lot of the Anglo-Saxon literature focuses on the collective consumption and appreciation of music in lesbian and gay cultures, whether in bars or discos or events organized by the lesbian and gay movement. Few studies have also taken individual musical tastes or experiences into account, with some exceptions such as Valentine (1995) on the consumption of music by the lesbian artist kd lang by lesbian fans, and Lemish (2004) and Singleton et al. (2007) on the meaning of the Eurovision Song Contest for gay fans. More recently, several scholars have researched pop phenomenon Lady Gaga and her influence on gay and lesbian individuals (Jennex 2013) and communities (Jang & Lee 2014). While these authors started from a specific musician or event, there is virtually no research exploring broader musical preferences in relation to sexual orientation. Hence, the second aim of this paper is to empirically explore individual music preferences among LGBs, and the specific LGB meanings attached to this music. In this analysis, we follow the example of similar (popular) music research relating musical preferences to other social categorizations such as class (e.g. Katz-Gerro, 1999; Mark, 1998; Van Eijck, 2001), age (Hargreaves and North, 1999; Hepper and Shahidullah, 1994), and gender (Christensen & Peterson, 1988; Colley, 2008).

Methodology

While the focus in most of the research mentioned above lies on the past, our research is firmly situated in the present and aims to explore contemporary musical preferences of lesbians and gays. Before we proceed, however, a few notes on terminology are indispensable. First, although we used the term 'lesbian and gay' in our overview of literature, in our own research we will use the term LGB (Lesbian, Gay and Bisexual) as a translation of 'holebi', the acronym currently most used in Flanders. We will not use the more inclusive terms 'LGBT', because (to our knowledge) no trans* individuals participated in the research, or 'queer', which is hardly used in Flanders (Eeckhout, 2011).

Second, we also need to reflect on the terms 'taste' and 'preference'. Both are seen as an affective evaluation (Rentfrow & McDonald, 2010), but while 'musical preference' mostly refers to a short term commitment (Abeles & Chung, 1996), 'musical taste is generally considered as the overall patterning of an individual’s preferences over long time periods' (Hargreaves et al., 2006, p. 135). In the results section of this paper we will use the term ‘musical preference’, as our empirical focus is on current rather than long term evaluations. For this purpose, we draw on a definition by Lamont & Greasley (2009), but add two terms: genre and musicians. Our concept of ‘musical preference’ therefore refers to the music, whether style, genre, piece or musicians that people like and choose to listen to at any given moment and in time. Through analysis of individual musical preferences we will attempt to obtain a clearer view on shared musical preferences, which we consider as indicative of the lesbian and gay musical cultures discussed in the literature review.

As mentioned above, a lot of the existing literature in this field deals with particular genres, styles or artists. In our research, we used a more open, exploratory approach to chart broader patterns of musical preference. Hence, our first research question was: What characterizes the musical preferences of contemporary Flemish LGBs? To answer this question, we used an online survey, a method which is particularly suited to study LGBs because it offers a low-threshold, anonymous, familiar way to quickly reach a large group of participants (Dewaele, 2008). To avoid a lack of diversity in the sample —which in LGB research tends to be predominantly constituted of white, well-educated, upper middle class men (Sandfort, 2000)— we used a diverse range of recruiting channels.2 This recruiting strategy led to a sample of 761 participants, which is sufficiently large for the level of statistical analysis. Although this is not a random sample (as in most if not all quantitative research on sexual minorities), so generalizations to the larger Flemish LGB population are tentative, the various ways of recruiting participants led to a varied and relatively balanced sample in terms of gender (57% male, 43% female) and age (43% of the participants were 30 or older at the time of research, in 2010). On a seven point scale of sexual identity, a large majority of the sample identified as exclusively (65.4%) or predominantly (24.3%) gay or lesbian, the remaining 10.2% considering themselves as bisexual (6%) or rather bisexual (4.2%).3

The online survey took a broad, exploratory approach, asking questions about different media, including music uses and preferences. However, our interest was not in simply charting these preferences but in understanding them and the meaning of music in relation to sexual identities and gay and lesbian culture. Therefore, our second research question was: How do Flemish LGBs perceive the connection between music and sexual orientation? In particular, two subquestions were addressed: What is the importance of the musicians' sexual orientation? And which genres and artists are associated with LGB culture, and why? To gain a deeper insight into those questions, 60 in-depth semi-structured interviews were conducted with participants who filled in the online survey and indicated their interest in participating in further research (31 men and 29 women).4 The interviews were conducted by different interviewers within the framework of a student research seminar under the supervision of the first author in 2010. The interviewers received extensive training in qualitative interviewing, also stressing the importance of informed consent to safeguard the interviewees rights. The interviews were fully transcribed and analyzed by the authors, using the Atlas.ti software to identify and code topics and opinions in relation to music preferences and appreciations.

LGB musical preferences

In order to answer the first, overarching research question What characterises the musical preferences of contemporary Flemish LGBs?, one question from the online survey provides a good starting point: "What is your favourite music genre?", offering a list of genres to choose from. While we are aware of the limitations of this —and any— list of musical genres, among other things because of the blurry and continuously evolving borders between genres, we do think this limited list with relatively broad and clear genres provides a useful tool for the preliminary exploration of musical preferences. While analyzing the responses we came across consistent, strong and significant differences between men and women. Therefore, we will structure our account by focusing on differences along the lines of the participants' gender, fully aware of the fact that this is but one of the relevant dimensions of variation. We do not aim to present an essentialist account of gender differences —or indeed, of lesbians and gay men— but rather to explore the number and nature of gendered variations in musical preferences, leading up to our more in-depth analysis of the meanings attached to this music.

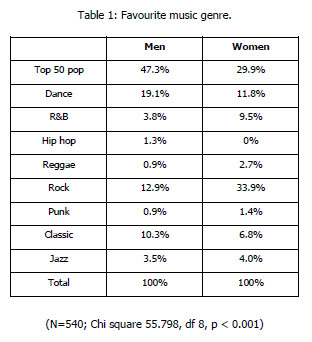

As Table 1 shows, there are clear and significant gender differences in relation to the preferred music genre, most noticeably in relation to pop and dance music, which are more popular with men, and rock and R&B, which are more popular with women. This finding is echoed by the answer to several other music-related questions. For instance, when asked about their favourite radio station, men more often mention the pop-oriented Q-Music (21.5% as opposed to 14.5% among women), while women prefer the mostly rock-oriented and alternative Studio Brussel (34.6% as opposed to 26.6%).5 As discussed above, these genres are usually associated with the opposite gender, as 'pop' is coded as rather feminine while 'rock' is coded as masculine.

The answers to these closed questions are further corroborated in an open question asking: “What is your favourite singer or band?” A wide variety of 344 names are mentioned, many by one person only, so although our analysis focuses on patterns, it is worth stressing from the outset that musical preferences present a wide individual variation. However, there are 40 artists who are mentioned by three people or more, even though each participant could only name one artist. We decided to take a closer look at these 'shared' musicians and their music to see to what extent they might be associated with lesbian and gay cultural meanings.

Among the male participants, 26 artists are mentioned by three people or more. In line with the abovementioned literature on the importance of female icons among gay men, several of the artists mentioned are known as 'divas'. While most of them (for instance Anni-Frid Lyngstad and Agnetha Fältskog (ABBA), Celine Dion, Tina Turner, Beyoncé and the Flemish singer Natalia) are renowned because of their vocal qualities, some of them (like Madonna, Britney Spears, P!nk, the Icelandic singer Björk, the 'French Madonna' Mylène Farmer, the Irish Róisín Murphy and above all Lady Gaga) also gained fame because of their extravagant, 'camp' appearances and/or the performative use of (homo)sexuality at public events, concerts or in video clips. However, it is important to note that not all the artists mentioned by several gay men have a clear affiliation with lesbian and gay culture, for example bands like U2 and Coldplay or solo artists like Johnny Cash and Tom Waits.

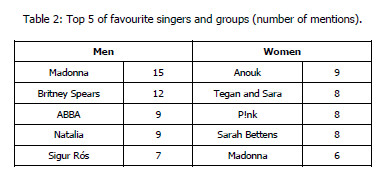

Similar results can be found among the musical preferences of lesbian and bisexual women. Yet, the list of favourite artists shared by three or more female participants consists of only 14 names (as opposed to 26 among the men). This lower number of shared preferred artists might suggest a higher diversity in the female participants’ music preference. Six of these artists also appear in the men’s list: P!nk, Sarah Bettens (both a solo artist and the lead singer of the Flemish rock band K’s Choice), Madonna, Natalia, ABBA and the Belgian dance formation Milk Inc. Here, too, female solo artists predominate (7 out of 9), but the emphasis is on a different kind of artists, which could be described as strong, independent women. Perhaps the top 5 among men and women is best suited to illustrate this difference (see Table 2).

While the male top 5 contains two international (Madonna, Britney) and one national diva (Natalia), plus a band closely associated with 'camp' gay culture (ABBA) and a band with a gay lead singer (Sigur Rós), the female top 5 contains only female artists, all with a strong and/or independent image. Some are known as strong personalities, like the Dutch rock singer Anouk, pop rock diva P!nk and the ‘Queen of pop’ Madonna. Others, like the lesbian singer-songwriters Tegan and Sara and the lesbian rock singer Sarah Bettens, can rather be described as independent ‘Do-It-Yourself’ musicians. Female performers dominate in both lists, but despite the overlaps there is a different emphasis corresponding to the overall male preference for pop and the female preference for rock. The historical tendencies of subverting heteronormative gender norms through music within LGB subcultures seem to persist in these preferences: the glitter and glamour of divas and camp still seems to attract gays more than lesbians, while the latter still seem to prefer the self-made, independent woman image which was a major component of women’s music from the 1970s.

In the interviews, the abovementioned divas and other icons were discussed more in-depth. For instance, Madonna is an interesting and important figure, appreciated by gay men as well as lesbians. Part of her status as an icon is linked to her openness towards sexual diversity. As mentioned by a few participants, Madonna has always supported her openly gay brother. Hanna (f, 21) emphasizes her strong personality:

I am a huge fan of Madonna, and her fanbase is incredibly gay-based. I think this is probably part of what made me become a fan back in time. I like the fact that more and more stars come out of the closet; they are a good example especially for young people who are in doubt about their sexual orientation.

Peter (m, 49) confirms this view: “Madonna is a very special lady to me. Really, she has created paths for us. Thanks to her homosexual brother, of course.” Madonna is a good example of the great importance attached to certain artists as 'idols', who can play a role in the identity formation and self-acceptance of LGBs. Similarly, two lesbian Flemish artists are frequently named as the personal icon of male as well as female participants: Sarah Bettens, the lead singer of the former rock band K's Choice, and singer-songwriter Yasmine, whose status as a beloved lesbian icon was reinforced after she sadly committed suicide in 2009. Several other female stars like Kylie Minogue, Britney Spears and Beyoncé were also discussed with the participants. While their music does not necessarily coincide with the personal musical preferences of many of the participants, it is clearly more appreciated by gay men than by lesbians.

Finally, in terms of cultural specificity it is telling (if not surprising) that most of the artists discussed are 'global', often American stars. Not only do the preferences we identified in Flanders correspond to international patterns, in particular in relation to the gay male predilection for divas; moreover, the actual artists which are mentioned by our Flemish participants are often international stars, suggesting the existence of LGB icons which are shared across borders –which, again, is not surprising in view of the broad appeal of these stars among the wider population.

LGB musicians

So far, our findings on musical preferences rather descriptively yet empirically confirm the existence of the gay and lesbian musical tendencies discussed in the literature review. Unintentionally, our findings seem to confirm widely held stereotypes about gay and lesbian culture, at least on a surface level. However, our aim is to dig deeper and to better understand our LGB participants’ appreciation for and attachment to such music. Moving on to our second research question: How do Flemish LGBs perceive the connection between music and sexual orientation?, we will start by exploring the importance of the musicians' sexual orientation. In the online survey, a closed question was asked about listening to music made by LGB artists or groups with LGB members. While 35.3% occasionally, 13.2% regularly and 5.1% often listen to such music, there is a clear and significant difference between men and women, the latter more often indicating that they regularly or often listen to music by LGB artists (25% as opposed to 13.2%).6

The artists mentioned in the open question about favourite artists (which we discussed above) are also (but not significantly) more often lesbian, gay or bisexual among women than among men (21.8% as opposed to 17.8%). Taking a closer look at the list of 40 artists mentioned by three or more people, we find that among the male participants' favourites, four artists are openly gay or lesbian: Jón Þór Birgisson, the lead singer of the Islandic band Sigur Rós; Kele Okereke, the lead singer of the British band Bloc Party; George Michael; and Sarah Bettens. Madonna is said to be ‘bisexual chic’ or ‘faux bisexual’, having demonstrated homosexuality rather in a performative way on stage and in the media. Among the female participants' preferences, three musicians (the twins Tegan and Sara, and Sarah Bettens) are openly lesbian while one artist (Mika) is openly gay. David Bowie, like Madonna, can be considered to be ‘bisexual chic’. The sexual orientation of P!nk has been subject to many rumors; she is sometimes claimed to be bisexual but has officially denied this. This relatively high number of openly LGB shared favourite artists, especially in the top 5, indicates a certain inclination of LGB audiences towards preferring LGB artists.

Further discussion of this topic during the interviews sheds more light onto the importance of the artists' sexual orientation. Overall, the sexual orientation of artists is mostly seen as incidental or of secondary importance in relation to the actual music. Often, the sexual orientation of an artist is even unknown to the listener. However, various participants do indicate that knowing that their favourite artists are LGB is a ‘nice extra’. For instance, answering whether the sexual orientation of an artist matters to him, Kevin (m, 30) specifies: “It is not at all important for me. However, I probably have more sympathy for them, unconsciously. But I don’t generally get a kick out of it or search for [homosexual artists].” However, a small group (11 participants) indicates that they do consciously listen to music by LGB artists. Eight of them are female, which is in line with the overall quantitative tendency for female participants to show more interest in music made by lesbian artists. For instance, Kate (f, 44) states: “I mostly listen to lesbian music, if anything like that may be said to exist” and so does Manon (f, 46): “I do [listen to LGB music], especially if the artist is a lesbian.” Laura (f, 21) confirms that the artists’ openness towards and activism for sexual diversity can be a specific reason for listening to LGB musicians: “It plays a role, because Queen’s front man Freddy Mercury is very open about it. It speaks to me. He also died of AIDS […] I admire him”. As in the discussion about Madonna above, this quote bespeaks the deep investment in certain artists in relation to LGB issues and identification among our participants, across both genders.

LGB music

As the previous section demonstrates, the sexual orientation of artists generally is not a key element in the music our participants prefer; it does, however, create a certain connection and it seems to contribute to the establishment of a canon of 'LGB music' —that is: music perceived to be connected to LGB culture. To better understand the evaluation of such 'LGB music', we discussed the topic with our participants. To start with, the question was asked whether they thought ‘gay’ or 'LGB' music exists.7 While about a quarter of the participants who gave their opinion on this matter think it does not exist, roughly half think it does, giving a wide range of enthusiastic to laconic answers. “Yes of course, most definitely!”, Julie (f, 20) says. Carine (f, 21) specifies: “Well, yes, because you can feel that LGBs […] have a whole different music genre to themselves.” A sense of the perception of specific music as part and parcel of the LGB community emerges from her answer. Strikingly, quite a few answers are self-contradictory, making negative statements but implicitly confirming the idea of LGB or gay music:

No, it doesn’t really exist. But it is very characteristic. When you go out, you often hear 'hard' house or techno… and on the other hand, Madonna, ABBA and other artists of that genre are played. But I wouldn’t say that this is real gay music… no. However, they do of course play it a lot. (Christian, m, 30)

Whether or not the participants believe in the existence of gay or LGB music, most of them immediately connect the concept to specific genres, styles and artists. In fact, most participants confirm widely held stereotypical views about LGB music, even if some clearly resist them. Disco and pop music are the most frequently mentioned genres, in comments like “If it exists, I think it is situated in commercial music” (Daniel, m, 24) and “[gay music is] all flamboyant pop, actually, and disco too” (Hanna, f, 21). The associations of both men and women include Kylie Minogue, Madonna, Beyoncé, disco, 'party music', glitter and glamour, camp, kitsch, tacky and commercial music. Several 'gay anthems' are mentioned, most notably It's raining men by the Weather Girls/Geri Halliwell, I will survive by Gloria Gaynor and Dancing Queen by ABBA. Bart (40, m) stands out as an avid music listener and outspoken fan of various divas:

I like to listen to music of the 1970s and ‘80s; I think it has got something to do with my age. And I’m quite a fan of ABBA and Tina Turner. […] I went to see her in concert twice this year […] and my sister will try to get tickets for Whitney Houston. […] We also went to see Natalia in concert.

Interestingly, many participants seem to connect LGB music with what has been established above as the favourite gay male genres pop and dance. Steven (20, m) summarizes: “Essentially it boils down to this: a beautiful woman who makes a good show, wears great glittery fancy dresses and has a jet set life - that is what gays find cool”. These properties match one of the camp characteristics described above, namely the conscious yet affectionate parody of the traditionally feminine. Jennex (2013) makes a strong case for camp sensibility’s ongoing importance, also for younger generations of gay men; and our interview participants seem to confirm the validity of this claim in the Flemish context.

Some female participants, however, have a very different idea of what LGB music is. For Eve (f, 37), for example, LGB-music refers to independent underground bands:

There are certain groups which focus on LGBs, but most of the time those are not very successful. […] Sometimes there are small lesbian bands who write lesbian lyrics, and you encounter these things through ZiZo8 or other channels. […] They are very specific bands which don’t exist very long, they have one or two songs and then disappear again.

The kind of music she describes fits into the genre of women’s music, which is closely related to lesbian culture since the 1970s.

Repeatedly, gender comes to the fore as an important axis of differentiation, as many participants make a distinction between lesbian and gay music. For instance, Julie (f, 20) states:

I really think that my girlfriend listens to lesbian music. How can I explain this? I will give you some examples, because I can’t explain it any other way. She listens to K’s Choice, Tegan and Sara, Mira and Hannelore Bedert. That is really typical music to me, I don’t know any LGB who doesn’t listen to these things. All of my lesbian friends like Tegan and Sara and Mira, I don’t know why. When we’d go out and they played some pop-dance songs and I’d ask my friends, what kind of music this is, they’d all say "this is faggot music". (Julie, f, 20)

While not (known to be) lesbian, Flemish singer-songwriters Mira and Hannelore Bedert do fit in the list of 'independent' female artists preferred by many female participants.

Another lesbian participant tries to explain what lesbian music means to her: “I’d say it’s a bit calmer, like... singer-songwriters. I can’t really name it” (Kristien, f, 21). The tendency to like strong and independent women, who are mostly active in rock and singer-songwriter genres, is clearly present in the interviews with female participants, as it was in the online survey. The visible aspect of artists displaying strength seems to play an important role in the musical preferences of lesbians: “[Lesbians prefer] the rougher kind of woman. Like P!nk, you wouldn’t really call her very feminine, would you? I think appearance matters a lot [for lesbians]” (Carine, f, 21). Later, she reaffirms this, stating that lesbians prefer 'women with balls'. While not always clear to the participants, it seems that the music they like does provide them with role models and figures of identification, particularly in relation to gender expectations. These different views of what LGB music entails align with the earlier observed gender differences concerning favourite music genre.

These distinctive female and male preferences in music are connected to the formation of separate yet overlapping lesbian and gay communities and cultures. In lesbian circles, the shared knowledge and appreciation of particular artists like Beth Ditto, Sarah Bettens, P!nk and Tegan and Sara makes individuals part of the community, thus contributing to the creation of a separate lesbian collective identity as mentioned in the introduction. Yet many female participants also enjoy 'gay' camp, kitsch and pop, with most women mentioning some affiliation to pop music and divas, especially when going out in the LGB scene —hence stressing the connection between this music and specific LGB-related locations and settings. While most interviewees have a clear idea which music is (seen as) gay and/or lesbian, they struggle to pinpoint why this music is so successful with LGBs.

Many participants associate 'gay' music with letting one’s hair down and partying, activities related to the abovementioned settings such as bars and discos. In the eyes of several participants, such music can also create a sense of community and safety: "With YMCA and similar things, people immediately respond to it: they create a certain bond. Anyone is allowed to let themselves go; it creates an atmosphere everyone feels good in” (Philip, m, 48). Often, connotations of a happy, free and peaceloving lifestyle are associated with gay music: “Essentially, gays will automatically like almost anything that is not aggressive. I have already noticed that: anything aggressive will not be received well [by a gay audience]” (George, m, 29). While the characteristics of music perceived as 'LGB music' as described by these participants closely correspond with the long-existing (sub)cultural codes within the LGB community as described above (for instance in relation to gender roles), it also clearly contributes to the creation of an affirmative context for LGB identification.

Although this music is clearly 'shared' —that is: known and associated with LGB culture— it is not necessarily liked by all: the very same genres and artists appear to have positive as well as negative connotations. One exemplary negative response shows that the interviewee thinks of this perceived gay or LGB music as “cheap, commercial junk, like Kylie Minogue” (Lorenz, m, 31). Although the music of this and other divas like Judy Garland, Gloria Gaynor or Celine Dion is not always appreciated in private, it is seen as a valuable part of LGB culture. For instance, when one female participant was asked whether she liked pop and disco music in private as well, she answers: ”I like that kind of music for a tacky party, but it’s rather unlikely that I would play it for myself. It’s fantastic music if you really want to let your hair down, but I wouldn’t buy it myself” (Chloe, f, 23). The outstanding role of music within LGB communities is confirmed by such statements: in the context of LGB culture, subverting one’s own taste parallels subverting heteronormative society. David (m, 19) summarizes these ambiguous feelings about the existence of LGB-music: ”There are some genres which speak to a large group of gays. I’m thinking of disco and glamrock, for example, but not every gay man thinks that it is good music.”

This and similar answers allude to a general sense of music which is claimed and appropriated by LGB culture: “What is gay music? Is it disco? […] Judy Garland, is that gay music? We have claimed it, which is something else!” (Peter, m, 49). The idea of gay or LGB music as a social construct of the LGB community, although not always expressed in such clear terms, arises throughout the interviews. Male and female participants share this sense. For instance, Alice (f, 41) recognizes and at the same time nuances the notion of LGB music:

Typical gay music? Yes, everything disco, glitter and glamour and all that, yes. But I think that heterosexuals can also have a lot of fun with that kind of music and that they don’t always associate [LGBs] with it. But you notice that there are certain people, certain artists and stars that are more appreciated by an LGB audience than others.

ABBA, as mentioned in the introduction, is a good case in point. Many confirm the perception that ABBA made gay music: “ABBA is so typically gay, isn’t it. I think everybody can sing along” (Bastien, m, 37). Some participants first deny that ABBA is related to gays, but then link the band to gay parties: “It’s not typically gay, but we adore it. Because they sing about love-related topics […] we can all relate to. […] Dancing Queen and such, that’s fantastic. It’s right, somehow, about gays. And it is very danceable” (Peter, m, 49). Other participants state that ABBA does not produce gay music but that their music is often perceived as such: “No, ABBA absolutely doesn’t [make gay music]. It’s what the people make of it. This has something to do with subculture and not with the music of ABBA as such” (Hilde, f, 39). Like Hilde, many participants connect the notion of LGB music to subculture and collective music consumption. In this sense, the appreciation of the music discussed throughout this article is at least partly an acquired taste. Its association with LGB culture is often based on joint consumption in social settings, which points to the importance of intermediaries such as DJs and party promotors who select and play this type of music.9

Conclusion

As demonstrated in our overview of the academic literature on the topic, music has long been and still is an important part of lesbian and gay lives and cultures. Nevertheless, the actual musical preferences of lesbians and gays have not been empirically and systematically studied to date. In order to complement research focusing on a particular genre or subculture, we decided to explore a broad range of musical preferences amongst contemporary Flemish LGBs, combining quantitative and qualitative methods. To answer our first research question, What characterizes the musical preferences of contemporary Flemish LGBs?, we primarily relied on the quantitative survey. Despite a lot of variation, a clear pattern arose: gay and bisexual men tend to prefer pop and dance music, while lesbian and bisexual women prefer rock. This pattern was confirmed in the subsequent qualitative interviews. Musical preferences turn out to vary strongly according to gender, as they do in the broader population, but in the opposite direction: our male participants tend to prefer music which is culturally coded as 'feminine' (pop, commercial, mainstream), while our female participants tend to prefer music coded as 'masculine' (rock, independent, alternative). The patterns we found very much confirm internationally observed insights into differences between lesbian and gay cultures. Moreover, many of the artists most mentioned by our participants are international stars, which suggests the existence of shared, 'global' LGB cultural icons.

Trying to get a better grasp on these findings, we addressed a second question, How do Flemish LGBs perceive the connection between music and sexual orientation? First, we explored the importance of the musicians' sexual orientation, which turned out to be a nice extra but not a key reason to listen to particular music. Nevertheless, for quite a few women lesbian artists had an extra appeal. Second, we further explored which genres and artists are associated with LGB culture, and why. Although not all participants agree that there is such a thing as 'gay' or 'LGB' music, most do have quite a clear image of particular genres and artists who are coded as lesbian and/or gay, and who are associated with LGB culture. Again, there is a clear distinction between a gay male culture associated with 'mainstream', popular dance music and divas, and a lesbian culture associated with independent, strong female rock stars and alternative singer-songwriters. Interestingly, the male and female participants agree on the central position of 'gay' disco and divas in LGB party culture, but in both groups some participants stress that this does not correspond with their personal musical preferences. Clearly, some music is appropriated by and perceived as part of a shared culture, allowing for collective identification but not necessarily coinciding with personal preferences. Heteronormative codes of masculinity and femininity, as well as their exaggeration or subversion (for instance in camp), play a key role in the cultural processes of musical signification and appropriation we observed.

Reflecting on these findings, we note that the continuities with older, international patterns discussed in the literature review are striking: music continues to play a key role as a shared point of identification, and there are still distinctive gendered musical cultures, despite overlaps and shared tastes (e.g. for Madonna as a strong diva). However, as indicated above, it is important to remember that in this account we only focus on the participants' gender, while other factors and variations (in terms of age, class, ethnicity etc.) are also important in understanding musical preferences among lesbians and gays. Further research is needed to disentangle the intersection of multiple individual and collective uses and meanings of music, as well as variations within and blurred lines between the gender groups which have been presented here as rather homogeneous. Similarly, much more could be said about the importance of the specific Flemish cultural and social context, going beyond our initial disclosure of patterns broadly corresponding to international findings. Finally, more in depth analysis of the specific importance and meanings of music in the varied lives of LGBT individuals is sorely needed.10

References

Abeles, H.F. & Chung J.W. (1996). Responses to music. In D.A. Hodges (Ed.), Handbook of music psychology (2nd ed.) (pp. 285-342). San Antonio: IMR Press. [ Links ]

Amico, S. (2001). ‘I want muscles’: House music, homosexuality and masculine signification. Popular Music, 20(3), 359-378.

Bayton, M. (1992). Out on the margins: feminism and the study of popular music. Women: A Cultural Review, 3(1), 51-59. [ Links ]

Biddle, I. & Jarman-Ivens, F. (2007). Introduction: oh boy! Making masculinity in popular music. In F. Jarman-Ivens (Ed.), Oh boy! Masculinities and popular music (pp. 1-17). New York/London: Routledge. [ Links ]

Booth, M. (2002). Campe-toi!: On the origins and definitions of camp. In F. Cleto (Ed.), Camp: Queer aesthetics and the performing subject: A reader (pp. 66-79). Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press. [ Links ]

Borghs, P. & Eeckhout, B. (2010). LGB rights in Belgium, 1999-2007: A historical survey of a velvet revolution. International Journal of Law, Policy and the Family, 24(1), 1-28. [ Links ]

Brett, P., Wood, E., & Thomas, G.C. (Eds.) (1994). Queering the pitch: The new gay and lesbian musicology. New York: Routledge. [ Links ]

Brett, P. & Wood, E. (2001). Gay and lesbian music. In The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians (Vol. 9, pp. 597-608). London: Macmillan.

Buckland, F. (2002). Club culture and queer world-making. Middletown: Wesleyan University Press. [ Links ]

Chauncey, G. (1994). Gay New York: Gender, urban culture, and the making of the gay male world, 1890-1940. New York: Basic Books. [ Links ]

Christensen, P.G. & Peterson, J.B. (1988). Genre and gender in the structure of music preferences. Communication Research, 15(3), 282-301. [ Links ]

Clifton, K. (2004). Queer hearing and the Madonna queen. In S. Fouz-Hernández & F. Jarman-Ivens (Eds.), Madonna’s drowned worlds: New approaches to her cultural transformation, 1983-2003 (pp. 55-68). Aldershot: Ashgate Publishing Ltd.

Cohan, S. (2005). Incongruous entertainment: Camp, cultural value, and the MGM musical. Durham: Duke University Press. [ Links ]

Colley, A. (2008). Young people’s musical taste: Relationship with gender and gender-related traits. Journal of applied social psychology, 38(8), 2039-2055.

Davis, M., & Lapovsky Kennedy, E. (1986). Oral history and the study of sexuality in the lesbian community: Buffalo, New York, 1940-1960. Feminist Studies, 12(1), 7-26. [ Links ]

Dewaele, A. (2008). De schoolloopbaan van holebi- en heterojongeren [The school career of LGB and straight youth]. Antwerpen: Steunpunt Gelijkekansenbeleid. [ Links ]

d’Emilio, J. (1983). Capitalism and gay identity. In K.V. Hansen & A.I. Garey (Eds.), Families in the US: kinship and domestic politics (pp. 131-141). Philadelphia: Temple University Press.

Dyer, R. (1998). In defense of Disco. In C.K. Creekmur & A. Doty (Eds.), Gay, lesbian, and queer essays on popular culture (pp. 407-415). Durham: Duke University Press. [ Links ]

Dyer, R. (2002). The culture of queers. London: Routledge. [ Links ]

Eeckhout, B. (2011). Queer in Belgium: Ignorance, goodwill, compromise. In L. Downing & R. Gillett (Eds.), Queer in Europe: Contemporary case studies (pp. 11-24). Farnham: Ashgate Publishing Ltd. [ Links ]

Farmer, B. (2005). The fabulous sublimity of gay diva worship. Camera Obscura, 20(2), 165-195. [ Links ]

Fouz-Hernández, S. & Jarman-Ivens, F. (Eds.) (2004). Madonna’s drowned worlds: New approaches to her cultural transformation, 1983-2003. Aldershot: Ashgate Publishing Ltd.

Frith, S. & McRobbie, A. (1978). Rock and sexuality. In S. Frith & A. Goodwin (Eds.), On record: Rock, pop and the written word (1990) (pp. 317-332). London: Routledge.

Hargreaves, D.J. & North, A.C. (1999). Music and adolescent identity. Music Education Research, 1(1), 75-92. [ Links ]

Hargreaves, D.J., North, A.C., & Tarrant, M. (2006). The development of musical preference and taste in childhood and adolescence. In G. McPherson (Ed.) The child as musician: A handbook of musical development (pp. 135-154). Oxford: Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

Haslop, C., Hill, H., & Schmidt R.A. (1998). The gay lifestyle: Spaces for a subculture of consumption. Marketing Intelligence & Planning, 16(5), 318-326. [ Links ]

Hellinck, B. (2004). Peter Pan. Uitgaan in de jaren ’50 en ’60. Het ondraaglijk besef: Nieuwsbrief van het Fonds Suzan Daniel, 10, 24-26.

Hellinck, B. (2007). Over integratie en confrontatie: Ontwikkelingen in de homo- en lesbiennebeweging [About integration and confrontation: Developments in the gay and lesbian movement]. BEG-CHTP, 18, 109-130.

Hepper, P.G. & Shahidullah, S. (1994). The beginnings of mind-evidence from the behaviour of the fetus. Journal of reproductive and infant psychology, 12(3), 143-154. [ Links ]

Horn, K. (2012). Camping with the stars: Queer performativity, pop intertextuality, and camp in the pop art of Lady Gaga. Current Objectives of Postgraduate American Studies, 11. Retrieved from http://copas.uni-regensburg.de/article/view/131/155

Irvine, J.M. (1994). A place in the rainbow: Theorizing lesbian and gay culture. Sociological Theory, 12(2), 232-248. [ Links ]

Jang, S. M., & Lee, H. (2014). When pop music meets a political ssue: Examining ow “Born This Way” influences attitudes toward gays and gay rights policies. Journal of Broadcasting & Electronic Media, 58(1), 114-130.

Jennex, C. (2013). Diva worship and the sonic search for queer utopia. Popular Music and Society, 36(3), 343-359. [ Links ]

Jennings, R. (2006). The Gateways Club and the emergence of a post-second world war lesbian subculture. Social History, 31(2), 206-225. [ Links ]

Katz-Gerro, T. (1999). Cultural consumption and social stratification: Leisure activities, musical tastes, and social location. Sociological perspectives, 42, 627-646. [ Links ]

Kourtova, P. (2012). Imitation and controversy: Performing (trans)sexuality in post-communist Bulgaria. In F. Attwood, V. Campbell, I.Q. Hunter & S. Lockyer (Eds.), Controversial images: Media representations on the edge (pp. 52-66). Houndmills, Basingstoke, Hampshire: Palgrave Macmillan. [ Links ]

Lamont, A. & Greasley, A. (2009). Musical preferences. In S. Hallam, I. Cross, & M. Thaut (Eds.), The Oxford Handbook of Music Psychology (pp. 160-168). Oxford: Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

Lareau, A. (2005). Lavender songs: Undermining gender in Weimar cabaret and beyond. Popular Music and Society, 28(2), 15-33. [ Links ]

Lemish, D. (2004). ‘My kind of campfire’: The Eurovision Song Contest and Israeli gay men. Popular Communication, 2(1), 41-63.

Leibetseder, D. (2012). Queer tracks: Subversive strategies in rock and pop music. Farnham: Ashgate Publishing Ltd. [ Links ]

Lont, C.M. (1992). Women’s Music: No longer a small private party. In R. Garofalo (Ed.), Rockin’ the boat: Mass music and mass movements (pp. 241-254). Cambridge: South End Press.

Mark, N. (1998). Birds of a feather sing together. Social Forces, 77(2), 453-485. [ Links ]

Moore, C. (2001). Sunshine and rainbows: The development of gay and lesbian culture in Queensland. Queensland: University of Queensland Press. [ Links ]

Rentfrow, P.J. & McDonald J.A. (2010). Preference, personality, and emotion. In P.N. Juslin & J. Sloboda (Eds.), Handbook of music and emotion: Theory, research, applications (pp. 669-695). Oxford: Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

Rodnitzky, J.L. (1999). Feminist Phoenix: The rise and fall of a feminist counterculture. Westport: Praeger Publishers. [ Links ]

Ross, A. (2002). Uses of camp. In F. Cleto (Ed.), Camp: Queer aesthetics and the performing subject: A reader (pp. 53-55). Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press. [ Links ]

Sandfort, T. (2000). Homosexuality, psychology, and gay and lesbian studies. In T. Sandfort, J. Schuyf, J. Duyvendak, & J. Weeks (Eds.), Lesbian and gay studies: An introductory, interdisciplinary approach (pp. 14-45). London: SAGE Publications Ltd. [ Links ]

Singleton, B., Fricker, K., & Moreo, E. (2007). Performing the queer network. Fans and families at the Eurovision Song Contest. SQS, 2(7), 12-24. [ Links ]

Taylor, J. (2012). Playing it queer: popular music, identity and queer world-making. Bern/New York: Peter Lang. [ Links ]

Valentine, G. (1995). Creating transgressive space: The music of kd lang. Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers, New Series, 20(4), 474-485. [ Links ]

Van Eijck, K. (2001). Social differentiation in musical taste patterns. Social Forces, 79(3), 1163-1184. [ Links ]

Whiteley, S. (2000). Women and popular music: Sexuality, identity and subjectivity. New York: Routledge. [ Links ]

Whiteley, S., & Rycenga, J. (Eds.) (2006). Queering the popular pitch. New York: Routledge. [ Links ]

Date of submission : February 25, 2015

Date of acceptance : April 21, 2015

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the students participating in the 2010 research seminar on 'LGB media, culture and identity' at the University of Antwerp for their help in conducting the interviews. We are also grateful to Leen De Wispelaere for her contributions to the analysis of the data.

Notes

1 In the general discussion, the term 'lesbian and gay' is used to refer to these (historical) subcultures. In discussion of the Flemish context and research, the term 'LGB' (Lesbian, Gay and Bisexual) is used as a translation of the widely used Flemish term 'holebi'.

2 The call for participation was widely spread online (websites and newsletters of 17 LGB associations, discussion boards and social network sites) and offline (a magazine announcement, a radio interview and flyers in LGB bars).

3 For our analysis, we discuss all the male and all the female participants together, as the group of bisexuals was too small to analyze separately and preliminary analysis disclosed no significant differences, although research with a larger sample of people identifying as (rather) bisexual would be necessary to corroborate this.

4 The interviews were fully transcribed and analyzed using the Atlas.ti software for qualitative analysis. In this paper, all quotes are literal translations by the authors. The names of participants have been changed for the sake of anonymity, but we do add their gender (m/f) and age.

5 N=623; Chi square 15.748, df 6, p < 0.05.

6 N=666, Chi Square 16.595, df 3, p = 0.001.

7 In this context, the Dutch terms 'homo' (short for homosexual) and 'holebi' were used interchangeably by both interviewers and participants, and both terms were variously interpreted by the participants as referring to gay, lesbian or 'shared' LGB music.

8 The largest Flemish LGBT magazine.

9 While this exploratory research does not allow for definitive statements about the role of such intermediaries, they are the object of further in-depth, historical research by one of the co-authors.

10 In-depth analysis of the Flemish case as well as in-depth analysis of the importance of music in the lives of LGB individuals goes beyond the scope of this exploratory article but it is the topic of ongoing, in-depth qualitative research by the authors.