Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Acessos

Acessos

Links relacionados

-

Similares em

SciELO

Similares em

SciELO

Compartilhar

Observatorio (OBS*)

versão On-line ISSN 1646-5954

OBS* vol.9 no.2 Lisboa jun. 2015

Use of blogs, Twitter and Facebook by UK PhD Students for Scholarly Communication

Yimei Zhu*, Rob Procter**

*Yimei Zhu, PhD Researcher, Sociology, University of Manchester, Arthur Lewis Building, Oxford Road, UK, M13 9PL. (zhuyimei@manchester.ac.uk)

**Professor Rob Procter, Deputy Head of Department of Computer Science, University of Warwick, Coventry, UK, CV4 7AL.(Rob.Procter@warwick.ac.uk)

ABSTRACT

This study explores scholarly use of social media by PhD students through a mix-method approach of qualitative interviews and a case study of #phdchat conversation. Social media tools, such as blogs, Twitter and Facebook, can be used by PhD students and early career researchers to promote their professional profiles, disseminate their work to a wider audience quickly, and gain feedback and support from peers across the globe. There are also difficulties and potential problems such as the lack of standards and incentives, the risks of ideas being stolen, lack of knowledge of how to start and maintain using social media tool and the potential need to invest significant amount of time and effort. We found that respondents employed various strategies to maximize the impact of their scholarly communication practice.

Keywords: social media, scholarly communication, blog, Twitter, Facebook, Web 2.0, PhD students, early career researchers

Introduction

Globalisation has reduced the constraints of geography on economic, political, social and cultural arrangements (Water 2001). This intensification of worldwide social connections unconstrained by time and space (Giddens 1990) has been reinforced by the rapid development of the World Wide Web in the last two decades. The internet has enabled open communication between people from all over the world, including academics. Whilst scholars previously depended on accessing published papers in the library or meeting in conferences to keep up-to-date within their research field, the emergence of new media tools, such as research blogs, micro-blogs and social networking sites, have enabled real-time communication and dissemination of scientific contents (Maron and Smith 2008; Neylon and Wu 2009). Social media seem to have gained some popularity in the research life cycle among academic communities, from identifying research opportunities to disseminating findings (Nicholas and Rowlands 2011). Social media tools can be used to search for knowledge and stay current with new literature (Bonetta 2009; Gu and Widén-Wulff 2011), or disseminate research-related information and to promote research projects, conferences and publications (Letierce et al. 2010a; Priem and Costello 2010; Terras 2012).

However, the benefits of using social media tools and especially the precise evidence of these benefits have been lacking in the literature. The Research Excellence Framework (REF), which are guidelines released by the Higher Education Funding Council for England (HEFCE), for assessing the quality of UK academic research, did not credit work published solely via social media (HEFCE 2012). There were no formal incentives in UK academia for disseminating research related contents on social media. Moreover, social media content is not peer reviewed and thus might not be trustworthy or reliable. The academic reward system still relies on the priority of discovery based on the quality and quantity of formal publications (Merton 1957). For PhD students who are at their early career stages, getting published in academic journals or books is extremely important, as they have not secured professional status or reputation. Would the use of social media be a distraction from doing ‘real’ research? Can the adoption of social media benefit PhD students in any way? According to the Diffusion of Innovation theory, in order to make a decision to adopt or reject any innovation, an individual needs to weigh the advantages and disadvantages of using the innovation (Rogers 2010). How are those early adopters using social media tools? What are the benefits of using social media and what are the difficulties and potential problems? What strategies can be adopted to maximise the impact of PhD students’ scholarly communication practice on the social media?

To explore these issues, a mixed-methods approach of qualitative interviews and a case study of tweets containing #phdchat were conducted between May 2012 and March 2013. This paper begins with a review of the literature on scholarly communication, social media and relevant empirical studies. It then outlines the design of our study and discusses the findings, including how participants use social media tools in their research work, benefits and difficulties, as well as the strategies used by early adopters to maximise the impact.

Background and literature review

Scholarly communication is used as a broad term to cover all the activities and norms of academic research related to producing, exchanging and disseminating knowledge (Rieger 2010; Hahn et al. 2011). It is often used to refer primarily to the process of peer-reviewed publication that has traditionally relied on scholarly publication in print journals and conference proceedings (Procter et al. 2010b). Now, scholarly communication has largely been transformed to online, digital publication using the World Wide Web (Nicholas et al. 2009). Moreover, institutional repositories, data centres and new media tools have provided new forms of scholarly communication in relation to producing, exchanging and disseminating academic research (Björk 2004; Wilbanks 2006; De Roure et al. 2010; RIN 2011).

With the development of the internet and related technologies, social media have gained popularity across the globe. Social media refers to a group of online applications ‘that build on the ideological and technological foundations of Web 2.0, and that allow the creation and exchange of User Generated Content’ (Kaplan and Haenlein 2010: 60). Social media sites and tools provide a technical platform to enable users to interact with each other and generate content together in a virtual community, in contrast to Web 1.0 where users are passive viewers of the content that has already been created (Thanuskodi 2011).

A survey of academic researchers all over the world found that the most popular social media tools for research purposes are those for collaborative authoring, conferencing, and scheduling meetings, whilst the least popular ones are for blogging, microblogging and social tagging and bookmarking, which may be due to their new and innovative characteristics (Nicholas and Rowlands 2011). However, in the recent years, microblogging and social networking sites have become part of people’s everyday life in Western countries. The current top two most popular social media tools with the largest number of monthly visitors are Facebook and Twitter, each with over 300 million estimated unique monthly visitors (eBiZMBA 2015). Research blogs have also been discussed in the literature as a popular social media tool for academics to communicate research ideas, and can be found in popular academic journals, such as Nature and Science (Kjellberg 2010). Academic publishers such as the Nature Publishing Group (NPG) and Public Library of Science (PLoS) also started to support blog posts to promote scholarly articles (Stewart et al. 2013). Thus the use of research blogs, Twitter and Facebook for scholarly communication are the main focus of this study.

Research Blogs

Blogs are web pages whose content can be filled in by dated entries, usually displayed in a reverse chronological order; and often combining text and images. The pages also usually display links to other blogs or web pages relevant to the topics contained in them, and a comments function allows interaction between the authors and readers. This function is usually monitored and can be altered by the blog host (Bukvova 2011). The configurations of blogs can range from individual blogs with a sole author to a variety of network structures, such as those hosted by a faculty or a research community over a broad topic, or a set of carefully selected blogs aggregated and present in a single web space (Tatum and Jankowski 2010). Examples of research blogs can be found in specialised web-portals such as scienceblogs.com or researchblooging.org (Kjellberg 2010). A famous example of research blog for publishing research updates is the Open Notebook Science in Chemistry and Chemical Biology, whose participants use a web blog to record day-to-day laboratory work, within which, data can be linked and made openly available (RIN 2010). This kind of blogs enabled real-time communication and dissemination of scientists’ work. Early adopters of research blogs reported positive experiences in gaining valuable feedback of their work after posting pre-publication chapters on their blogs (Powell et al. 2011;Weller 2011).

Twitter is the most popular public micro-blog, which is a weblog that consists of short messages (Java et al. 2007). Twitter was first launched by a San Francisco-based company in October 2006 and soon became an international phenomenon, which is popular in many parts of the world, including North America, Europe and Japan (Honeycutt and Herring 2009). It allows registered users to post and share short messages of up to 140 characters, which are posted in reverse chronological order, to any other registered members. Such messages are called ‘tweets’. Users ‘follow’ another member in order to subscribe to that user’s message feeds. Over the past few years, Twitter has been adopted for scholarly activities, such as sharing information and resources, asking for advice, promoting work, and networking with peers (Veletsianos and Kimmons 2012). Users are able to disseminate articles or other research information by including a hyperlink (URL) of the websites in their tweets. Twitter enables scholars across the globe to spread scientific materials to reach different communities, including their peers, students and general public (Ebner et al. 2010).

The convenience of using twitter has been enhanced by the popularity of smart phones and tablets, which can download a Twitter application without charge. Many basic mobile phones also have internet connectivity and so can access Twitter easily. This convenience enables users, including those from impoverished countries, to search for and disseminate information rapidly and at all times (Murthy 2011).

Twitter was first used as a conference communication tool as an experiment by early adopters and later became a common way of promoting conferences (Ebner et al. 2010). In micro-blogs, hashtags were introduced to be used by a community of users interested in, and discussing, a specific topic (Laniado and Mika 2010). By pre-pending a hash sign in front of a word (e.g., #science) to represent a specific topic, it can help users search and aggregate messages related to that tag. Hashtags are now commonly employed by Twitter users. For academic users, there are discipline-specific communities, such as #twitterstorians for History scholars and position-specific network, such as #phdpostdoc (Regis 2012). In academic conferences, organisers are able to disseminate information about the conference and facilitate communication between participants and peers by circulating the specific themed hashtags.

Facebook was created by two Harvard students in 2004 for other university students in the United States, but rapidly became a global phenomenon. Users can create online profiles with information about themselves, link with other people’s profiles as their ‘friends’, comments on friends’ profiles and send private messages to other users. Additionally, users are allowed to create groups and events that they can invite others to join (Hodge 2006). Facebook profiles have different degrees of privacy settings so that users have control over who can see them. For example, a user may choose her profile to be accessible only to ‘friends’. Facebook started the feature of the Facebook page in 2010, which enabled the creation of pages for companies, brands, persons and so on.

Individual Facebook members can join in by ‘liking’ the specific page and participating in discussions. The owners of these pages can make use of these online spaces to share photos, videos and massages with ‘fans’ without revealing any private information from their own profiles. Academics may create a Facebook page as an individual or for the courses they teach to communicate with students. Academics can also create Facebook groups for their research centres or disciplinary areas to disseminate research information and interact with peers.

Empirical research on scholarly use of social media

Nicholas and Rowlands’ study found that younger researchers favour the use of blogging, microblogging, social tagging or bookmarking (Nicholas and Rowlands 2011). Crotty (2011) suggests that this is because the ‘increasing time pressure as one’s career advances–a first year graduate student has a lot more time to waste on Twitter than a professor actively seeking tenure’. Priem et al. (2011) studied scholarly use of Twitter and found no evidence that rank (full-time faculty, post docs, or PhD students) disproportionally affected Twitter use or presence. Procter et al. (2010b) surveyed UK academics in their adoption of Web 2.0 and found that PhD students and professors both had the highest percentage of frequent users (20%) comparing to research fellows (18%), senior lecturers (15%), lecturers (13%) and reader (6%). These findings suggest that professional status does not necessarily influence scholarly use of social media—professors may be ‘wasting’ the same amount of time on Twitter as PhD students. But are they really being distracted from producing real work? Can the adoption of social media tools benefit PhD students’ research work in any ways? Regis (2012) suggests that PhD students and early career researchers can use Twitter to form communities that offer support, advice and sharing of good resources. By 6 June 2012, over 85% of the higher education institutions in the UK have both official Facebook pages and Twitter accounts (Kelly 2012). In the recent years, many universities in the UK have started training courses for PhD students and academic staff on how to use blogs and other social media tools to promote their online presence and benefit their work. However, barriers were reported for adopting social media in research work. For example, Coverdale (2011) organised a training session for PhD students and participants were concerned about the significant amount of time and commitment required to build up a network on Twitter and maintain a blog, as well as the lack of incentive for the time and effort being invested.

Most empirical research on social media use in an academic context focuses on students and faculty members’ use of social networks sites and social media tools for teaching and learning in higher education (e.g. Selwyn 2009; Roblye et al. 2010; Moran et al. 2011). To date, the literature on how PhD students use social media for scholarly communication has been extremely limited. This study will explore gaps and post questions for further research as well as contribute to the literature of communication study in academia.

Methodology

The methodology chosen for this study incorporates the use of qualitative interviews and a case study of tweets. Between May 2012 and March 2013, eight interviews were conducted using a convenience sample of six PhD students who had used social media for scholarly communication and two who chose not to use social media in their academic life. The interviewees who were social media users were asked when and why they started to use social media, whether and/or how they used research blog, Twitter and Facebook to help their research. The questions for non-user participants were shorter and they were asked why they chose not to use social media in research work.

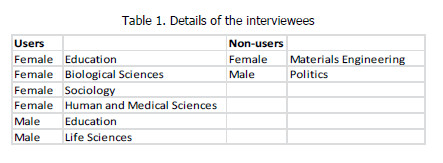

The main sampling strategy was purposeful sampling – a mixture of convenience and quota sampling. Convenience sampling involves the selection of the most accessible subjects which is the least costly in terms of time, effort and money (Marshall 1996). It allows the data collection to be completed quickly; however, it cannot enable reliable generalisations to a wider population. Quota sampling is designed to reflect a wider population in terms of important categories. It aims to ensure the inclusion of diverse elements of the population in the proportions in which they occur in the population (Selltiz et al. 1959). As in this study, these elements are gender and academic discipline. Interviewees were selected from various discipline areas to offer some diversity. As shown in Table 1, four interviewees were from Social Sciences and another four were based in Medical, Life Sciences and Engineering. Four of them were male and another four were female.

The respondents were based in two large universities in northern England. None of the interviewees was based in Communication Sciences or Computer Science that require the use of social media as part of their research work. However, all eight PhD students including the non-user participants were familiar with the internet and used computers in their daily work.

We decided to recruit mostly experienced social media users in order to explore their insights into the benefits and difficulties of using social media tools to communicate research. From November 2011 to May 2012, the lead author attended a number of workshops in Manchester and Oxford that were related to academic use of social media which helped recruit potential participants. Most of the respondents for the interviews were recruited from people that the lead author met at those workshops. Others including the two non-user participants were recruited through the author’s personal network.

Various interview methods were used—four by face-to-face, one by Skype instant messaging and three by email. Questionnaires were emailed to interviewees before the face-to-face interviews and Skype messaging interviews. Their replies were analysed briefly to gain an initial impression, which was probed further in the interviews. The face-to-face and Skype interviews lasted approximately an hour each. Face-to-face interviews were recorded and subsequently transcribed. The email interviews contained an initial questionnaire and a number of follow-up emails probing questions. In this study, findings from the first interview helped develop questions for interviews with later interviewees.

Case study

During fieldwork, we came across a popular Twitter online thread forum and chat group using the hashtag #phdchat. #phdchat was first set up in 2010 by a UK based PhD student Nasima Riazat and has become a regular live chat event on Twitter every Wednesday 7.30-8.30pm British Standard Time. The organisers usually post a poll of topics before hands and participants vote to make a decision for a topic for that week. Twitter users may include #phdchat in their public messages any other time during the week in order for their messages to be seen by other users who search for this term. Two years after it was first set up, a rapidly growing #phdchat community has had regular participants from the UK, United States, Australia and central Europe, including postgraduate students, lecturers, professors and other academics who have long finished their doctoral study but want to offer advice and share experiences, as well as other followers who have an interest in higher education, such as Guardian Higher Education (Riazat, 2011). An early participant in #phdchat group created a wiki which records some of the highlights from archives of previous live chats.

A case study of two cohorts of topic called ‘blogging about your research’ was conducted as the topic fit into the agenda of this study. This topic was discussed as the #phdchat live chat on two occasions at 4 April 2012 and 20 June 2012. All the tweets from the live chat of ‘blogging about your research’ on two occasions were on the public wiki site and analysed for this case study1. After assigning a number to the name of each participant, it showed that around 50 people participated in the first live chat and around 60 people participated in the second. The first cohort contains 527 tweets (11,705 words) and the second cohort contains 307 tweets (7,432 words).

Thematic analysis was conducted to analyse the two cohorts of #phdchat tweets deposited on the public wiki site. Thematic analysis, as a method for identifying patterns and themes, is ideal for describing qualitative data in rich detail (Braun and Clarke 2006). The contents were coded by the author into the following themes: function of blogging, blog content, worry about blogging, strategies, share of resource and good practice, sense of community and mentioning of other social media tools.

Results and discussion

How they use social media and for what purposes/benefits?

As this paper focus on the use of research blogs, Twitter and Facebook for scholarly communication, each of these three social media tools are discussed separately in relation to how they are being used and the purposes and benefits of using them.

Research blogs

In relation to research blogs, some respondents had a blog linked with their real names, others preferred anonymity. A number of respondents read other research blogs hosted on sites such as WordPress, Blogger, Tumblr or blogs hosted by their institutions:

‘I read a number of blogs, mostly on WordPress or Tumblr as the free sites appear to be the most popular amongst the research community.’ (Female, PhD student in Sociology)

‘I read University Faculty of Life science blog on the WordPress. I also read blogs about sciences, history and mythology.’ (Male, PhD student in Life Sciences)

The participants of #phdchat in the case study also gave similar answers in terms of popular research blogs:

‘WordPress indeed is the most user friendly.’

‘The research blogs that I like to read are either on blogger or Tumblr.’

As for the content of blogging, most respondents confirmed that they would post published papers and abstracts that have been accepted by conferences on blogs. According to the participants in the two live #phdchat streams we observed, blogs can be used as a notebook that records thoughts and progress of the PhD. Other types of contents may be book reviews, summary of chapters, teaching, conferences, social issues and personal stories to ‘give audience a sense of who I am’. Many participants stated that they would blog about their research progress rather than about the research content:

‘I don't blog results but I share stories about my field work and my general progress.’

‘I think people blog about their journey and experience rather than the actual PhD topic.’

The reason behind this is possibly related with academic rewards and will be discussed in the ‘Difficulties and potential problems’ section.

In the #phdchat case study, participants discussed the purposes and benefits in writing and reading research blogs. The most common purposes were practising writing, disseminating and gathering information, networking and sharing thoughts, reflecting and getting feedbacks, keeping a record of ideas and conversation, as well as raising profiles and reaching out to more people. It is common in many disciplines that getting published in an academic journal can take over one year. For PhD students, who may not have published anything in peer reviewed journals, blogging can potentially raise their profiles and rapidly disseminate information without the long process of gaining research results or waiting for long publication process. Blogging may be seen as a quick approach for early career researchers to get their names/work out into the public domain and publish in an informal way. Some participants believed that the research blog can serve as a ‘publishing platform’ offering an open record of their research. Others believe that writing a blogging is good for practising and improving writing about their research, which may progress further to formal publishing opportunities.

Many participants in the #phdchat case study acknowledged the benefit of gaining valuable feedback. Some participants thought that getting comments on blogging posts was comparable to the benefits of traditional peer review process:

‘Opens up your research to peer review from an early stage, get input and ideas.’

‘My blog readers have actively contributed to all stages of my research, including helping me develop proposal and methodology.’

‘It's a great way to get ideas and thoughts down and then can look at them with a fresh pair of eyes/get feedback.’

Twitter was popular among the interviewees in this study to link to other users, look for useful information, and participate in discussions. One interviewee stated that Twitter can be useful to look for information when she applies for jobs:

‘I don’t need to look for jobs now, but I will in the future. When I saw job ads, I search for the names of the supervisors and see whether they have Twitter account.’ (Female, PhD student in Human and Medical sciences)

She also suggested that Twitter helped her search for useful information related to her research subjects, funding bodies and top researchers in her area:

‘Because I do medical research, I also searched for the disease name of my research interest and followed the patients who mentioned that disease. I also follow big funding bodies, like the Welcome Trust. I also follow top researchers in the field.’ (Female, PhD student in Human and Medical sciences)

Twitter can be an effective means for finding information quickly:

‘I use Twitter as it offers me timely and up-to-date information which is relevant to my research. I feel I can subscribe to people who I feel will yield useful and relevant data, and it is also great to feel that are able to engage in dialogue with others. You can get an answer straight away rather than waiting for a detailed email response or nothing at all.’ (Female, PhD student in Sociology)

‘To get more information on science as well as jobs across the globe… to search for scientific events taking place throughout the world and people’s positive and negative feedback about the events.’ (Female, PhD student in Biological Sciences)

Twitter is also often used to disseminate information. A number of interviewees stated that they would post web links to papers they have published on Twitter. Some of them also posted links to articles that they find interesting or post information about news of their workplace. One example of Twitter’s use in disseminating information was raised as below:

‘I use Twitter to disseminate information, present things from other network. Twitter is like a platform, connected to many other social media and websites. Twitter presents short summary.’ (Male, PhD student in Life Sciences)

Several interviewees had participated in the #phdchat live chat on Twitter and regularly add themed hashtags in their tweets in order for the information to be disseminated to wider audience.

When asked whether they used Twitter during a conference, a number of interviewees indicated having such experiences. One suggested that the adoption would depend on types of conferences and whether they have access to the internet. In some discipline areas, Twitter is less widely adopted than the others in conferences:

‘The last two conferences I went to, they said we don’t have official twitter account, but we’ll look into it. But my partner is in Education and technology, their conference has twitter account, hashtag, twitter wall. It’s still getting there.’ (Female, PhD student in Education)

Another interviewee indicated that she would announce conferences or workshops she was going to attend on Twitter:

‘Yes, because others may not know about them, and it’s useful also to know who is going to be at a conference. It also encourages others to do the same.’ (Female, PhD student in Sociology)

Facebook Groups and Pages

Facebook was the most common social media tool for general use among the interviewees including the two non-user participants. All the interviewees set their Facebook profiles as private. Although most respondents tend to use Facebook for personal use rather than research related purposes, the popularity of Facebook among the younger generation in the western countries and its potential as a new communication platform for academics is worth noting. One interviewee described her positive experience with Facebook groups and pages. She suggested that Facebook groups and pages can be used to facilitate an informal support network for researchers and they may use this space to promote their professional profile, as well as organise events and meetings. This interviewee created a public Facebook page for herself as an individual as well joining other Facebook groups:

‘Yes, I’m a member to two Facebook groups. People from my school, most PGR students, MSc, leading to PhD […] Posting events or people asking questions, for example, can someone show me how to use SPSS? Or does someone know how to get help for xx […] I set up a Facebook page linked to my blog. The Facebook page is public. So when people search me, they can see the Facebook page and see the information of the blog.’ (Female, PhD student in Education)

PhD students from the lead authors’ department have actively participated in a Facebook group created in September 2011 by a student representative. Group members often post information about conferences, workshops and work opportunities, seek and offer advices and organise events.

Difficulties and potential problems

The participants in the #phdchat case study shared various difficulties they had faced in starting and using research blogs. There were concerns related to academic rewards and the fear of not being able to secure those rewards. Since the Nineteenth Century, the publication of articles in journals and the relative prestige of the journals in which they are published have become predominant indicator of professional performance for researchers and the institutions that employed them (Merton 1957;Schauder 1993;Correia and Teixeira 2005). Under the academic reward system, an individual researcher’s career advancement and promotion are often based on their professional performance in terms of the quality and quantity of formal publications (Kim 2011). Most recent empirical studies found that academic researchers’ top concern for scholarly communication is to disseminate their work in academic journals and conferences (Procter et al. 2010a). Publications via social media are not recognised as a means to evaluate researchers’ performance and are not given credit by the Research Excellence Framework (REF).

Thus the lack of incentives and lack of precise evidence of benefits in using social media are barriers for adoption. These barriers were raised by two interviewees who were reluctant to adopt social media in their research work.

When asked why he chose not to use social media for his research, one interviewee suggested ‘lack of perceived value and time to do so.’ (Male, PhD student in Politics)

Another interviewee said, ‘I can’t be bothered since I can’t see what advantage that could have.’ (PhD student in Materials Science)

Participants from the case study were aware of the lack of formal incentives:

‘That depends. No promotion for writing blogs, you need journal papers in the UK. The REF will have to change.’

‘I doubt that REF will ever take account blogging, but at least it can be additional evidence.’

As PhD students have not secured professional status or reputation, they may be very protective of their projects and data, for fear of someone else stealing their ideas and getting published first:

‘My data is quick and easy to collect and analyse, easy for someone to replicate and publish first.’

‘I have a real problem with keeping my research private. So what if someone else has a similiar idea.’

‘That's my worry about blogging my thesis. And having the content stolen!’

The concern about ideas being stolen or plagiarised from research blogs can apply to the use of other social media tools. One interviewee expressed her concern of plagiarism using Twitter:

‘Twitter makes it very easy for people to see someone else’s insights and then pass them off as their own, either on Twitter or in their own academic research. How does one prove plagiarism of ideas without making reference to a publication?’ (Female, PhD student in Sociology)

Apart from plagiarism, content on social media can also be misused for commercial purposes. One interviewee shared a story of his online content being used inappropriately by a third party:

‘Once, some company use my project picture in their website and saying it’s theirs. I reported them to the Twitter provider.’ (Male, PhD student in Life Sciences)

Regarding to the contents on the social web, there are ethical issues of what can be discussed in a public medium:

‘I can understand that it is important to know the boundaries of what can be discussed in public.’

‘I think sometimes there are ethical issues to consider, depending on your area.’

Another common problem of blogging, which can also apply to Twitter and Facebook, is the lack of knowledge of how to start and what to write about. One participant in the #phdchat case study commented: ‘I don’t feel authoritative enough to write on my subject’. Another participant emphasised that she was aware that once she wrote something online, ‘it's out there forever’. Would these public records make the authors look stupid? A study of digital scholarly communication in North America found a case of rumours about young researchers being denied interviews or jobs when employers mistakenly assumed that informal, unpolished ideas that they had published on a blog entirely represent their formal scholarly output (Maron and Smith 2008). Many PhD students may not have built up enough confidence of their expertise or feel vulnerable when posting in a public medium for fear of exposing their ignorance.

Other common difficulties are the time and effort needed to invest in learning how to use social media effectively and maintain these social media profiles. Several participants in #phdchat mentioned that it takes time to build a blog audience and it takes time to interact with the audience in order to get comments. There is also a risk of information overload on top of a busy PhD schedule.

Strategies

Link different new media tools together for cross-platform promotion:

Respondents from the qualitative interviews had various strategies for maximising the impact of content disseminated. The most commonly used strategy to maximise the impact of having various social media accounts is to link them together for cross-platform promotion:

‘Linking each site to one another so that they’re updated automatically […] I set up WordPress link to my Twitter, which is linked to my Facebook page. Friends and family on Facebook can see when I have a new blog post. But also people from Facebook Page or Twitter can see that I have a blog post. So I cover both bases separately. I used to post on Facebook and Twitter about my blog post. Once I set up the link on WordPress, it would just do it at once.’ (Female, PhD student in Education)

‘Embed conference presentations on blog via SlideShare.’ (Male, PhD student in Education)

‘I put my Twitter name on my email signature, and also encourage students and fellow researchers to follow me. There is also a link from my blog.’ (Female, PhD student in Sociology)

Linking accounts from different social media sites together is an easy and quick way for scholars to promote their online content. For example, they can upload slides on SlideShare, embed it on their blog, then tweet about it and publish it in their other social media accounts such as LinkedIn and Schoop.it. This cross-platform promotion helps disseminate the slides to audiences on various social media sites, in contrast to the sole audience on SlideShare. This finding is in line with a study of blog aggregator ResearchBlogging.org (RB), in which Shema et al. (2012) found that 72% of the active blogs in their sample (126) had at least one active public twitter account. Linking accounts on different sites together aims to maximise the dissemination across different platforms.

Create a personal learning network (PLN)

‘A personal learning network (pln), can be defined as a collection of people and resources that guide your learning, point you to learning opportunities, answer your questions, and give you the benefit of their own knowledge and experience. In the 21st Century there are many tools to help these networks along including websites, social networks, RSS feeds, and podcasts that allow you to have advice and guidance from your personal learning network mentors delivered right to you.’ (Nielsen 2008)

In the recent years, the development of the internet enables lone PhD students to find peers from all over the world by searching on the social web. It is possible to find peers who are doing research in a similar area and thus collaborate and support each other. One interviewee specifically mentioned PLN and the benefit from engaging with audiences across the world:

‘Blogging first and then learning about Twitter. Once I actually started to use Twitter, I understand how it really work and then in cooperate the two together, then create a network for myself. They call it a personal learning network (PLN). By creating that, some people I met on Twitter, It makes it easy for me to have an audience who are interested in what I have to say. It motivates me to keep my blog up [...] By reading someone’s blog and being part of the community, beginning to really understand the community side of it, which has been very useful […] my audience are mostly PhD students, other researchers, not necessarily from UK, they are from everywhere.’ (Female, PhD student in Education)

Lone PhD students usually receive regular support from their supervisors and colleagues in their institutions. By creating a personal learning network through interacting with other users on the social web, PhD students may be able to gain support from peers all over the world. For example, reading and commenting regularly on others’ research blogs may lead them to visit and comment back, and thus gradually form a personal learning network for oneself. The use of themed hashtags on Twitter can provide a platform for informal support networks and communities without the constraints of time and space. The participants of #phdchat are from many different countries and according to our observations, many of them actively interact with each other and answer questions to one another.

Build a professional online profile

It is interesting that the strategy used by most interviewees for tackling privacy issues was to have two different identities on Facebook and Twitter—Facebook Profile for their private identities and Twitter for their professional identities. Kietzmann et al (2012) criticised the lack of research that investigates how people manage different identities on different social media sites. In this study, a number of respondents separate their personal social media profiles from their professional accounts:

‘My Facebook profile is private and I set up a Facebook page linked to my blog. The Facebook page is public. So when people search me, they can see the Facebook page and see the information of the blog […] I prefer to have this personal space. I have many friends that I work with that are on both sites but I find the distinction helpful’. (Female, PhD student in Education)

‘Yes, I’m very selective of people who can follow me on Twitter. I don’t post anything personal on Twitter or social media. I don’t post any pictures of family or friends on public social media sites. You can do that on Facebook […] Facebook for private use and LinkedIn, academia.edu for professional use.’ (Male, PhD student in Life Sciences)

Having a Facebook page that fans can ‘like’ is a strategy for having a Facebook presence but using it for a professional purpose. Having a Facebook page does not reveal any private information of the owner’s profile. One interviewee also configured the settings of her Facebook profile to limit the access of certain acquaintances, such as students she was teaching at the time. Interviewees chose specific social media tools to build a professional online profile—having a public professional profile on sites such as Twitter, Facebook Page, research blogs, LinkedIn and academia.edu, but keeping Facebook profile private to connect with friends and family. Most respondents prefer to keep private and professional social media use separate. Some mix them together, but are careful about it and are aware of the complications.

Interviewees were cautious about what they post on their social media profiles:

‘My rule of thumb is that I’d only put online what I’m not ashamed of and willing to publicly defend.’ (Female, PhD student in Education)

Others indicated that they would not leak research findings on their social media sites before going through traditional publication channels first. This seems to be extremely important for early career-researchers as publications are keys to their academic careers.

Conclusions and Future Work

This study explores the scholarly use of social media by UK PhD students. Social media tools are not alternatives for traditional peer reviewed publication, but rather supplements to help academics with their research work in various ways. Social media tools, such as research blogs, Twitter and Facebook, can be used by PhD students and early career researchers to search for information, promote their professional profiles, disseminate their work to a wider audience quickly, and gain feedbacks and support from peers across the world.

There are difficulties and potential problems, such as the lack of formal incentives, the risks of ideas being stolen and plagiarised, lack of knowledge of how to start and maintain using social media tools and the time and effort investment needed to become proficient in their use. PhD students in this study deployed different strategies to maximise their use of social media and these strategies can also be adopted by other academic users.

The findings suggest that social media can be beneficial for early career researchers if it is used wisely, but that there are also risks and barriers and these continue to act as a deterrent to many. As the UK Research Excellence Framework (REF) does not yet recognise scholarly outputs on social media, careers will continue to depend on formal, peer-reviewed publications. Discussing ideas on the social web can potentially leak good ideas to competitors with the consequence that they may gain an advantage and, ultimately, credit. Thus, it is important to be careful about what kinds of content are communicated through social media and to follow institutional and disciplinary norms. To help researchers to manage these risks, there is a need for examples of good practice, benefits and dangers of using social media so new users can learn from others. Training in social media for researchers would also help in raising standards and helping them avoid the risks. Finally, if new forms of scholarly communication are to flourish, it is important that institutions and funders recognise and incentivise the dissemination of research outputs through social media.

The exploratory nature of this study aims to capture initial insights of current scholarly communication practice among early career researchers. There are limitations as only eight interviewees were recruited in this study and they cannot represent the wider population of PhD students in the UK. A quantitative study will be needed to capture the attitudes and practices of the UK academics and investigate any factors that influence uptake and use.

References

Björk, B. C. (2004). Open access to scientific publications–an analysis of the barriers to change? Information research, 9(2), 170.

Braun, V. & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative research in psychology, 3(2), 77-101. [ Links ]

Bonetta, L. (2009). Should you be tweeting? Cell, 139(3), 452-453. [ Links ]

Bukvova, H. (2011). Taking new routes: Blogs, Web sites, and Scientific Publishing. ScieCom Info, 7(2). [ Links ]

Correia, A. M. R. & Teixeira, J. C. (2005). Reforming scholarly publishing and knowledge communication: From the advent of the scholarly journal to the challenges of open access. Online information review, 29(4), 349-364. [ Links ]

Coverdale, A., Hill, L. R. & Sisson, T. (2011). Using social media in academic practice: a student-led training initiative. Compass: The Journal of Learning and Teaching at the University of Greenwich, (3), 37-45. [ Links ]

Crotty, D. (2011). Researchers And Social Media: Uptake Increases When Obvious Benefits Result [Online]. Available: http://scholarlykitchen.sspnet.org/2011/03/01/researchers-and-social-media-uptake-increases-when-obvious-benefits-result/ [Accessed 22 Oct 2012].

De Roure, D., Goble, C., Aleksejevs, S., Bechhofer, S., Bhagat, J., Cruickshank, D., Fisher, P., Hull, D., Michaelides, D., Newman, D., Procter, R., Lin, Y. W. & Poschen, M. (2010). Towards open science: the myExperiment approach. Concurrency and Computation-Practice & Experience, 22(17), 2335-2353. [ Links ]

eBiZMBA. (2014). Top 15 most popular social networking sites May 2014 [Online]. Available: http://www.ebizmba.com/articles/social-networking-websites [Accessed 1 April 2015].

Ebner, M., Mühlburger, H., Schaffert, S., Schiefner, M., Reinhardt, W. & Wheeler, S. (2010). Getting Granular on Twitter: Tweets from a Conference and Their Limited Usefulness for Non-Participants. Key Competencies in the Knowledge Society, 102-113. [ Links ]

Giddens, A. (1990). The Consequences of Modernity. . Cambridge: Polity Press. [ Links ]

Gu, F. & Widén-Wulff, G. (2011). Scholarly communication and possible changes in the context of social media: A Finnish case study. Electronic Library, The, 29(6), 762-776. [ Links ]

Hahn, T., Burright, M. & Duggan, H. (2011). Has the revolution in scholarly communication lived up to its promise? American Society for Information Science and Technology, 37(5), 5. [ Links ]

HEFCE. (2012). Publication [Online]. Available: http://www.ref.ac.uk/pubs/ [Accessed 13 July 2012].

Hodge, M. (2006). The Fourth Amendment and Privacy Issues on the New Internet: Facebook.com and Myspace.com. Southern Illinois University Law Journal, 31, 95-123. [ Links ]

Honeycutt, C. & Herring, S. C. (2009). Beyond microblogging: Conversation and collaboration via Twitter. Proceedings of the 42 Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences. Los Alamitos, CA: IEEE Computer Society.

Java, A., Song, X., Finin, T. & Tseng, B. (2007). Why we twitter: Understanding microblogging usage and communities. Proceedings of the 9th WebKDD and 1st SNA-KDD 2007 Workshop on Web Mining and Social Network Analysis. San Jose, CA.

Kaplan, A. M. & Haenlein, M. (2010). Users of the world, unite! The challenges and opportunities of Social Media. Business horizons, 53(1), 59-68. [ Links ]

Kelly, B. (2012). Further Evidence of Use of Social Networks in the UK Higher Education Sector, 6 June 2012 [Online]. Available: http://ukwebfocus.wordpress.com/2012/06/06/guest-post-further-evidence-of-use-of-social-networks-in-the-uk-higher-education-sector/ [Accessed 23 Oct 2012].

Kim, J. (2011). Motivations of Faculty Self-archiving in Institutional Repositories. Journal of Academic Librarianship, 37(3), 246-254. [ Links ]

Kjellberg, S. (2010). I am a blogging researcher: Motivations for blogging in a scholarly context. First Monday, 15(8). [ Links ]

Laniado, D. & Mika, P. (2010). Making sense of twitter. The Semantic Web–ISWC 2010, 470-485.

Letierce, J., Passant, A., Breslin, J. & Decker, S. (2010a). Understanding how Twitter is used to spread scientific messages. Web Science Conference. Raleigh, NC, USA.

Letierce, J., Passant, A., Breslin, J. G. & Decker, S. (2010b). Using Twitter During an Academic Conference: The iswc2009 Use-case. Proceedings of the Fourth International AAAI Conference on Weblogs and Social Media.

Maron, N. L. & Smith, K. K. (2008). Current Models of Digital Scholarly Communication: Results of an Investigation Conducted by Ithaka for the Association of Research Libraries. Washington, DC: Association of Research Libraries.

Marshall, M. N. (1996). Sampling for qualitative research. Family Practice, 13(6), 522-526. [ Links ]

Merton, R. K. (1957). Priorities in scientific discovery: a chapter in the sociology of science. American Sociological Review, 22(6), 635-659. [ Links ]

Moran, M., Seaman, J. & Tinti-Kane, H. (2011). Teaching, Learning, and Sharing: How Today's Higher Education Faculty Use Social Media. [Online]. Babson Survey Research Group. Available: http://www.eric.ed.gov/ERICWebPortal/search/detailmini.jsp?_nfpb=true&_&ERICExtSearch_SearchValue_0=ED535130&ERICExtSearch_SearchType_0=no&accno=ED535130 [Accessed 24 Oct 2012].

Murthy, D. (2011). Twitter: Microphone for the masses? Media, Culture & Society, 33(5), 779. [ Links ]

Neylon, C. & Wu, S. (2009). Article-level metrics and the evolution of scientific impact. PLoS Biol, 7(11), e1000242. [ Links ]

Nicholas, D., Clark, D., Rowlands, I. & Jamali, H. R. (2009). Online use and information seeking behaviour: institutional and subject comparisons of UK researchers. Journal of Information Science, 35(6), 660-676. [ Links ]

Nicholas, D. & Rowlands, I. (2011). Social media use in the research workflow. Information Services and Use, 31(1), 61-83. [ Links ]

Nielsen, L. 2008. Developing Mentors from Your Personal Learning Network. The Innovative Educator [Online]. Available from: http://theinnovativeeducator.blogspot.co.uk/2008/05/developing-mentors-from-your-personal.html [Accessed 5 Sep 2012].

Powell, D. A., Jacob, C. J. & Chapman, B. J. (2011). Using Blogs and New Media in Academic Practice: Potential Roles in Research, Teaching, Learning, and Extension. Innovative Higher Education, 1-12. [ Links ]

Priem, J. & Costello, K. L. (2010). How and why scholars cite on Twitter. Proceedings of the American Society for Information Science and Technology, 47(1), 1-4.

Priem, J., Costello, K. & Dzuba, T. (2011). First-year graduate students just wasting time? Prevalence and use of Twitter among scholars. Metrics 2011 Symposium on Informetric and Scientometric Research New Orleans, LA, USA.

Procter, R., Williams, R. & Stewart, J. (2010a). If You Build It, Will They Come? How Researchers Perceive and Use Web 2.0. Research Information Network. Available at http://www.rin.ac.uk/system/files/attachments/web_2.0_screen.pdf [accessed 21 Dec 2011].

Procter, R., Williams, R., Stewart, J., Poschen, M., Snee, H., Voss, A. & Asgari-Targhi, M. (2010b). Adoption and use of Web 2.0 in scholarly communications. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society A, 368(1926). [ Links ]

Regis, A. K. (2012). Early Career Victorianists and Social Media: Impact, Audience and Online Identities. Journal of Victorian Culture, 1-8. [ Links ]

Rieger, O. Y. (2010). Framing digital humanities: The role of new media in humanities scholarship. First Monday, 15(10). [ Links ]

RIN. (2010). Open to All: Case Studies of Openness in Research [Online]. Research Information Network Available: http://www.rin.ac.uk/our-work/data-management-and-curation/open-science-case-studies [Accessed 25 June 2011].

RIN. (2011). Data centres: their use, value and impact [Online]. Research Information Network Available: http://www.rin.ac.uk/our-work/data-management-and-curation/benefits-research-data-centres [Accessed 21 Dec 2011].

Roblye, M. D., McDaniel, M., Webb, M., Herman, J. & Witty, J. V. (2010). Findings on Facebook in higher education: A comparison of college faculty and student uses and perceptions of social networking sites. The Internet and Higher Education, 13(3), 134-140. [ Links ]

Rogers, E. M. (2010). Diffusion of Innovations, 4th edition: Simon and Schuster. [ Links ]

Schauder, D. (1993). Electronic publishing of professional articles: attitudes of academics and implications for the scholarly communication industry. Proceedings of the IATUL Conferences.

Selltiz, C., Jahoda, M., Deutsch, M. & Cook, S. W. (1959). Research Methods in Social Relations. New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston. [ Links ]

Selwyn, N. (2009). Faceworking: exploring students' education-related use of Facebook. Learning, Media and Technology, 34(2), 157-174. [ Links ]

Stewart, J., Procter, R., Williams, R. and Poschen, M. (2013). The role of academic publishers in shaping the development of Web 2.0 services for scholarly communication. New Media & Society, 15(3), 413-432. [ Links ]

Tatum, C. & Jankowski, N. W. (2010). Openness in Scholarly Communication: Conceptual Framework and Challenges to Innovation [Online]. Available: http://digital-scholarship.ehumanities.nl/wp-content/uploads/Tatum-and-Jankowski-openness-in-scholarly-comm-v202.pdf [Accessed 21 Dec 2011].

Terras, M. (2012). The verdict: is blogging or tweeting about research papers worth it? [Online]. The Impact Blog, LSE. Available: http://blogs.lse.ac.uk/impactofsocialsciences/2012/04/19/blog-tweeting-papers-worth-it/ [Accessed 13 June 2014].

Thanuskodi, S. (2011). WEB 2.0 Awareness among Library and Information Science Professionals of the Engineering Colleges in Chennai City: A Survey. J Communication, 1(2), 69-75. [ Links ]

Veletsianos, G. & Kimmons, R. (2012). Networked participatory scholarship: Emergent techno-cultural pressures toward open and digital scholarship in online networks. Computers & Education, 58(2), 766-774. [ Links ]

Water, M. (2001). Globalization, 2nd edition. London and New York: Routledge. [ Links ]

Weller, M. (2011). The digital scholar: How technology is transforming scholarly practice. London: Bloomsbury Academic. [ Links ]

Wilbanks, J. (2006). Another Reason for Opening Access to Research. BMJ (British Medical Journal), 333(7582), 1306-1308. [ Links ]

Ziman, J. M. (1987). An introduction to science studies: The philosophical and social aspects of science and technology: Cambridge Univ Press. [ Links ]

Date of submission: December 27, 2014

Date of acceptance: April 6, 2015

Notes

1 http://phdchat.pbworks.com/w/page/55047451/Blogging%20about%20your%20research