Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Acessos

Acessos

Links relacionados

-

Similares em

SciELO

Similares em

SciELO

Compartilhar

Observatorio (OBS*)

versão On-line ISSN 1646-5954

OBS* vol.8 no.4 Lisboa dez. 2014

A deliberative public sphere? Picturing Portuguese political blogs1

Elsa Costa e Silva*

*Professora Auxiliar do Departamento de Ciências da Comunicação, Universidade do Minho, Campus de Gualtar, 4710-057 Braga, Portugal. (elsa.silva@ics.uminho.pt)

ABSTRACT

Deliberative democracies are based on the principle of citizens participation. However, election turnouts and citizens alienation are signs of a political disengagement that could endanger the foundations of democratic systems. The spaces in which political debate and rational argumentation between equals may take place have diminished, yet new digital technologies have brought up potentialities in the promotion of online, horizontal and deliberative communication. Political blogs have been one of the most studied platforms, as they allow citizens engaged in political discussion and argumentation to establish a public sphere in which matters of public concern are debated. Nonetheless, issues of political polarization, fragmentation and non-rational debate have also been pointed out to limit the most optimistic perspectives over political blogs. By using the social network analysis, this paper aims to contribute to a better understanding of the role of Portuguese political blogs, by assessing its level of deliberation.

Keywords: Political blogs, deliberation, participation, public sphere, hyperlinks, Social Network Analysis.

Introduction

Modern democracies have been facing an increasing political disengagement, election turnouts and citizens alienation. One of the reasons pointed out to explain why citizens are supposedly distant from politics is the model of democracy adopted, which is mainly representational – citizens are represented in policy-making by elected officials, and do not effectively participate in the process. This situation raises concerns regarding the own nature of democracy, because this is a system that relies primarily in the inclusion of citizens in policy processes. The key concept in these concerns is participation, which can signify a wide array of civic practices.

The understanding of participation as a process that involves citizens in politics and in policy-making processes depends on the underneath conception of democracy (Carpentier, 2011; Martins, 2004). The more representational, the less involving – democracy is a process taken over by elites, elected officials, with citizens called in only to particular moments, such as voting or referendums. However, broader notions of participation consider it a tool for the full commitment of citizens with the governance of society and to the choice of alternatives, as a result of deliberation processes. Several new forms of participation have been emerging in the public sphere thus showing the interest of citizens in taking part of the political process, even though not in formal or institutional contexts.

One of the new forms of political participation that has attracted the attention of academics and researchers is online forums, such as political blogs, where citizens may engage in political deliberation over issues of public interest. Some concerns have been presented over the real impact of new technologies in increasing the levels of participation and in providing real democratic spaces where deliberation and political debate may occur (Dahlberg, 1998; Papacharissi, 2002). However, some evidences have pointed out the positive effect of the new media interactivity potential, namely in terms of political engagement (Boulianne, 2009). In the particular case of political blogs, Gil de Zúñiga et al. (2009: 562) showed that the practice of reading blogs increases the likeliness of discussing politics online.

On the other hand, even when discussing politics online, people may be only exposed to one side of the question, not seeking to hear other perspectives, which is essential to guarantee deliberation. Assessing the level of deliberation in online forums such as political blogs is then critical to evaluate their democratic gain. The purpose of this paper is to contribute to the understanding of Portugal political blogosphere, by providing evidences on the deliberative behavior of blogs, using the social network analysis methodology.

Democracy and deliberation

Reaching a common knowledge and standpoint over a public issue of common interest, as advocated by Habermas (1989) and Champagne (2000), depends on the existence of a previous enlightening and inclusive debate, where various perspectives are confronted. From a normative point of view, a deliberative political model underlies the assumption of the public sphere, that requires the participation of citizens from which should result an action or intervention. Through the discussion proposed by Habermas, language and communication origin and legitimize democratic practices in a network of communicative processes both within and outside the parliamentary set (Silva, 2002).

Discursive communication involves arguments, objections and criticism, this condition being the first postulate of this deliberative model. Another precondition is that everyone should be accepted and no one can be legitimately excluded. The decisions achieved within this process should not depend on external pressures (from other forms of power) and no internal coercion should either exist since equal participation is guaranteed. Everyone has the right to be heard and to introduce topics for the discussion and to be critical of the others proposals. The communicational practice, argues Esteves (2003: 204), thereby obeys to three criteria: the openness of the public, the openness of themes for discussions and the parity in argumentation. In this deliberation, the power of the best argument" (Habermas, 1989: 54) should prevail.

However, for some authors, this deliberative ideal may not be achievable. Sunstein (2008) notes, for example, that the group discussion can lead to bias and to more extreme positions, thus creating irreconcilable differences. If people are grouped into formations dominated by the same kind of thinking, then the internal deliberations will result in greater homogeneity within the group and greater gap from opposing thoughts. Because opinions are shared by the majority of the members, opinions will be reinforced, especially considering that any individual has the need to be favorably perceived by the others.

The ideal of public deliberation has also its supporters (Bohman, 1996), despite modern societies being characterized by complexity and pluralism in terms of values?and interests of the individuals. The concept of public relates to how the deliberation is made (in public), but also to the kind of arguments that are presented in the process, in an interaction that should be characterized as cooperative. "In the case of cultural pluralism, (...) diversity can even improve the public use of reason and make democratic life more vibrant" (Bohman 1996: 72), by providing alternative interpretations. Consisting of citizens acting in a context of fairness, the public sphere understood as a process, not as a structure, is the main source of innovation and learning in deliberative democracies. Here the participation of citizens is an unquestionable condition: a conception of politics that undervalues civic engagement is likely to miss out on the benefits of public deliberation as the discussion of potential for change in perceptions of interests, preferences, and values is a fundamental normative requisite of democracy (Blumler and Coleman, 2010: 146).

Participation is a broad concept that may range from a minimalist conception (reduced mostly to the time of voting, representation thus being an unidirectional process) to a maximalist dimension (in which politics goes beyond institutionalized forms in a heterogeneous and multidirectional process). The latest contributions to this debate have enlarged the concept beyond the institutionalized politics, not forgetting though that the ultimate goal of participation is to influence politics (Carpentier, 2011). In the context of deliberative democracy, the locus of participation takes place in communication, since this setting implies a decision-making process resulting from the discussion among free and equal citizens within the public sphere (materialized or just as a normative procedural conception). It is clear that equality between citizens is more an idealized condition than a reality, since some studies on the demographics of participation indicate that this practice is especially more regular in males with high resources in terms of time, money and skills (Couldry et al., 2010). Research has also demonstrated that participation tends to leave perennial legal forms (such as party affiliation, social or civic organizations) to become a more individual activity (Pole, 2010) or a practice developed in favor of specific causes in momentary aggregation forms.

Extending the concept of participation to spheres outside the traditional political system allows to account for a multitude of actions that citizens can take, even in the most intimate places such as home, in a broad understanding of political participation that goes beyond the formal institutional setting. The overt political apathy and disaffiliation from the established political system does not necessarily mean a disinterest in politics (Dahlgren, 2005). Political participation is much more than party affiliation and has been used to describe the increasing engagement in social movements in Western societies. There is a growing desire of citizens for better channels to participate in political life – while, at the same time, a widespread dissatisfaction with the functioning of democracy and with the performance of the representative function is growing (Dalton, 2008; Freire and Meirinho, 2009). Internet and digital platforms, such as blogs, have been presented as an example of these channels for political participation, as citizens can freely take part in discussions and debate over the course of societies.

Deliberation and the internet: the case of political blogs

Baker (2007) highlights the transformative effect of the internet in the public sphere that potentially can have, or has even now, a great political and democratic importance. In this particular scenario, the blogosphere provides important new spaces for public discourse in a world where such spaces have, in practice, been declining. Thus, the blogosphere, especially the political blogosphere, is increasingly regarded as a new public sphere where opinions and perspectives on aspects of public life are expressed in a constant deliberation. The blogosphere can revitalize functions of the civil society, such as the permanent scrutiny of public authorities, the dissemination of information and the empowerment of citizens to defend their own interests.

The political blogosphere has received increasing attention from academic research concerned with public sphere and political participation. The U.S. electoral campaign in 2004 provided a corpus of analysis that has been profusely analyzed in terms of the topics discussed and of the campaign agenda. In the so-called political blogosphere, campaign blogs or blogs of elected politicians are considered. But the research has devoted a special interest to these platform, not as campaign blogs or as a form of e-government, but rather focusing its attention on political blogs maintained by citizens (sometimes also held by members of parties or even elected but not as official sites) who are essentially discussion forums.

Campaign blogs or other forms of interaction between elected officials and citizens raised more doubts on its potential as "much vertical online communication seems to replicate the worst aspects of the established political communication system, with politicians running blogs that look like old-fashioned newsletters, while the horizontal communication among peers-citizens "adapted creatively to the informal, acephalous, nonproprietorial, unbounded logic of the network (Blumler and Coleman, 2010: 148).

Being a recent phenomenon, the blogosphere soon began to attract the attention of academics, particularly by the public perception of its influence. At first, this surprised researchers and politics: how could a platform with no central organization, no consensus among participants, unequal in terms of expertise, earn such an upward in the public space? As summarized by Drezner and Farrell (2008: 16), influence over political and policy outcomes was not a straightforward conclusion given the disparity in resources and organization vis-à-vis other actors.

Castells (2009: 263) points out that through blogs (which he sees as a form of mass self-communication) independent politicians have a different way to reach the target audience and that they intend to disseminate information and opinions that cannot be found in the mainstream media, as well as to establish a base of support for their approach to political issues. On the other hand, blogs potentiate an unprecedented propagation of information because they have an immediate viral dissemination, with the comments of bloggers and readers fueling controversy. The importance of these new actors in the current democratic societies is such that a growing number of bloggers works as political consultants, and the blogosphere has become a critical area of ??communication where the public image is created and recreated (Castells, 2009: 329).

The blogosphere has been envisaged as very influential in public space (Tremayne, 2007; Drezner and Farrell, 2008; Woodly, 2008), being able to influence the mainstream media and the political class and to provide interested citizens with new forms of information and knowledge. The growing influence in media contents and comentators (Ackland, 2005) and a greater civic intervention (Pole, 2010) have being pointed out as major outcomes of blogs. Moreover, the deliberation there taking place has advantages over other forms of online activism, particularly over electronic petitions that tend to originate policies «on request» to satisfy own interests rather than to fulfill the essential function of politics, that is the efficient allocation and management of scarce resources (Blumler and Coleman, 2010).

Woodly (2008) presents a very positive outlook on the political blogosphere, arguing that this platform has changed the structure of political communication by offering readers a democratic experience that is not possible by traditional forms. That is, political blogs are different because they have linking strategies that enhance interactivity and diversify the amount of information that is provided. Not based on political elites nor restrained by criteria of journalistic neutrality, political blogs provide questions and arguments and examine public facts, providing informations whose source is open and revealed (Woodly, 2008). Blogger do not need credentials to get into the discussion and have enlarged, in magnitude and scope, the political communication, thus compromising the power of big media corporations in setting the agenda (Pole, 2010).

Some authors have raised, however, the possibility of online discussion being dominated, like it happens in real life, by elites, thus not being able to influence public opinion. Being a mere reproduction of what happens in the traditional political debate, the blogosphere may just be an additional platform and not a real alternative that transforms the space and political structure (Dahlgren, 2005; Papacharissi, 2002). For Sunstein (2008: 93), the problem may also lie in the polarization process, stating that there is every reason to believe that the logic of group polarization characterizes social interaction on the Internet too, especially in contexts such as political blogosphere. The evidences lie in studies that show denser linking patterns between blogs of the same political affiliation, while opposing blogs do not even tend to discuss the same issues. Although it contains great promises as far the provision of a broader range of perspectives and the aggregation of dispersed information and knowledge are concerned, the political blogosphere may just mean that many readers only read blogs with which they feel more aligned, thus accessing to only one side of the story.

But other authors have noted further features in the political blogosphere that enhance the possibilities for deliberation. Firstly, the main function of political blogs is not to provide information as news sites do (Scott, 2007; Leccese, 2009). And though some criticism and scrutiny over media work have been found in blogs (Domingo and Heinonen, 2008; McKenna and Pole, 2008; Vos et al. 2011), most of the media voices is embedded in the speech of bloggers that use these facts and information to form their own arguments, strengthen perspectives and challenge opponents. Thus, the links to media are used to reinforce the skills and arguments for deliberation. For Koop and Jansen (2009: 171), the practice found in blogs to focus more on substantive issues, rather than on partisan politics (as media do), feeds the prospect of the blogosphere as a forum for democratic deliberation: this argument is sustained by the fact that, despite the balkanization of the discussion in ideological terms, the authors found a will in discussions that exceeded the partisan logic.

One of the basic elements used to assess to level of deliberation in the blogosphere is the hyperlinks between political blogs. Links have been considered as a sign of recognition in the internet, an acknowledgement of the authority of others (Karpf, 2008; Drezner and Farrell, 2008). In theoretical work aimed at conceptualizing a methodology of analysis for the networked public sphere, Bruns et al. (2008) suggest that the patterns of interconnection in the blogosphere indicate the existence of a network of attention: links indicate that the subject is interesting (positively or negatively), thus providing visibility and awarding influence. This recognition may be long-lasting (through blogrolls - other blogs listed in a column of the blog itself) or due to specific issues and to comments made ??to posts (thus involving the audience).

Other studies have studied links as an indicator of political affiliation or ideological proximity (Adamic and Glance, 2005; Bruns and Adams, 2009; Koop and Jansen, 2009; Moe, 2011; Park and Thelwall, 2008). This has been a major trend in research as links may reveal if new technologies are, in fact, leading to greater debate or to the fragmentation of public opinion, as people may only be exposed to what they want to. Homophily, people relating only to think-alike minds, has been described as a possible effect of blogs, meaning that the political discussion is increasingly polarized. Adamic and Glance (2005) found signs of the polarization process in a study that showed higher linking patterns between conservatives and between liberals and not between each other. But Hargittai et al. (2008: 85) found that although the most popular American political blogs are more likely to engage those with similar views in their writings, they also address those on the other end of the ideological spectrum. Another contribution of this study is the fact that it did not reveal an increasing trend in this linking pattern. Similarly, Moe (2011) characterized the Norwegian political blogosphere and did not find great signs of polarization, rather a platform for alternative voices.

These studies highlight the importance of studying political blogs as platforms for deliberation, assessing their role in providing a common ground for debate or, in the contrary, as spaces where homophily and polarization take place. Portuguese political blogosphere has received scarce attention in what relates to the assessment of deliberation or polarization processes through the study of hyperlinks. An example of a research on this matter is the study of Moura (2009), that analyzed the performance of two political blogs specifically created to support the two major political parties to 2009 legislative elections (the blogs Simplex and Jamais). The results showed that the blog Jamais (which was connected to the opposition party, the social-democrats) had a more insular practice in terms of hyperlinks and showed higher levels of aggressiveness. However, no image of the more global Portuguese political blogosphere has been provided in terms of linking between blogs.

Linking Portuguese political blogs: deliberation or polarization?

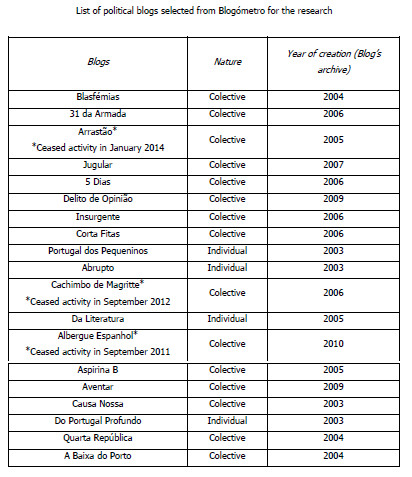

The aim of this paper is to assess the deliberation process in Portuguese political blogosphere by analyzing the linking patterns between blogs. In order to provide a more deepened image of the deliberation process in a wide public sphere, this research focused on the links of the 20 most read Portuguese political blogs (see annex A), selected from the list provided by Blogómetro2. The selection was performed having as criteria: citizen projects (meaning that there is no official logo or official speaking in the name of a given political party or civic movement or newspaper); major political content in blogs focusing on politics in general (and not specific policy sectors, such as education, health or economics).

Post were collected during four weeks in 2011 (one week in April, May, June and July). This period corresponds to a change in Portugals political system, as the country faced a moment of electoral campaign and change in the leader party. In June 2011, the leadership of the government changed from a Left (Socialist) to a Right (Social-Democrat) party. This period is then of particular interest in terms of political deliberation as, in the one hand, the future of the country was under discussion and deliberative processes are of high relevance in these contexts, but, on the other hand, electoral fight could increase the negative ambiance around political discussion, as well as polarization and aggressiveness between different ideological stands.

All in-posts links were coded manually and submitted to a quantitative and qualitative analysis. Each link was categorized according to the source of the connection (media, blogs, institutional sites, collaborative sites and other social media) and, concerning the links between blogs, to the type action performed: neutral (mere polite indication of other blogs, with no agreement or disagreement), positive (respectful acknowledgement of the others position, agreeing or disagreeing) and negative (mocking and ridicule others perspective).

During the analysis period, 3344 posts were collected, 63% of which contained links. A total of 3937 links were analyzed, 43% of which redirected readers to mainstream media sites, a value that is consistent with the ones found in studies focusing on different geographic regions (Etling et al., 2010; Leccese, 2009; Reese et al., 2007). The second major source of links are blogs with 32,5% of the total links (of which only 40% were internal links, to the own blog, but not necessarily to the blogger itself as most blogs are collective projects). This study only considers the set of links between blogs.

Dialogue between blogs

Conversation and dialogue between blogs is not the most important activity for political bloggers, but it represents a significant part of the interactions established in the universe under study. In the period of analysis, links connected all the blogs studied (except for Baixa do Porto that was not targeted by any link, although it linked to Arrastão), but a very large number of other blogs was also targeted: 195 different blogs, 18 of which foreigners. It thus seems that the most read political blogs are a kind of gateway to a much wider world of the blogosphere, channeling readers' attention to other foci of opinion they consider relevant.

On the other hand, all the 20 analyzed blogs are a very relevant core of the political blogosphere: of the total interactions with blogs, nearly 40% relates specifically to the set under consideration, with 60% of remaining links targeting at 200 other blogs. Besides this set, other projects (though less read) also proved to be important destination of links: it is the case of Câmara Corporativa, which received mainly links with a negative function. This blog is considered to be, in the political blogosphere in general, an anonymous space held by communication professionals in which takes place propaganda in favor of the former Prime Minister, José Sócrates, and is therefore mostly disregarded in this sphere. Other projects with a significant number of incoming links are Educação do Meu umbigo (dedicated to education policy) and Margens de Erro (which focuses on political polling and was hence heavily referenced in the first two weeks of analysis which corresponded to an election period).

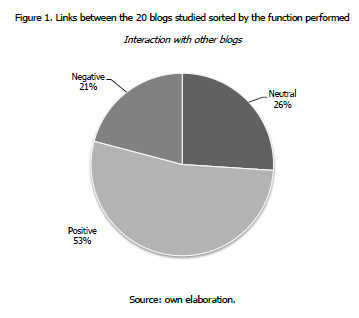

Some of the limitations pointed out to the blogosphere indicate that interactions between bloggers are often instilled with negative emotions, such as mockery or contempt, seeking to insult and not the debate of ideas or solutions for the governance of society (Dahlgren, 2005; Papacharissi, 2002). Thus, it makes sense to examine the nature of interactions between bloggers, specifically among the authors of the 20 blogs studied, in order to characterize the established relationships. And, in fact, our data do not support the idea of ??predominantly negative interactions (see Figure 1.

The most common practice is to link to other blogs to agree, disagree, debate and argue – functions performed by links we classified as positive interactions. Thus, in 53% of the links between the 20 analyzed blogs, bloggers envisioned the debate, with arguments, respecting the other. Another 26% of the links between blogs seek a neutral interaction, meaning that bloggers did not show agreement or disagreement, but acknowledged the presence of other bloggers. These links can be understood under the bloggers ethics of linking to blogs or bloggers they refer or that have written over the issue they are dealing with. Thus, only 21% of the interactions had a negative sense. The most targeted blog in our universe is Blasfémias, which received 18.5% of total links to the 20 blogs studied, and is followed by the Cachimbo de Magritte (12.3%) and 5 Dias (9.25%) – this latter one more targeted by negative links.

This data could suggest a blogosphere mainly deliberative and seeking to debate, but further evidences are needed, since most of the links could connect blogs of the same ideological trend thus showing a right/left polarization. Another methodology to answer this research question is then needed and it will be addressed in the next section.

Performing social network analysis to political blogosphere

Mutual links between blogs can be understood as a way to indicate relationships (Chin and Chignell, 2007) and determine networked conversations, identifying directions and connections. This network of blogs can be observed with the techniques of social network analysis, using software like Ucinet (Borgatti et al., 2002) that provides visualizations of social networks as well as the measurement of their properties. Social networks are made ??up of individuals (or organizations and objects) connected through social exchanges and relationships. The social network analysis has been widely used as a technique that maps and analyzes these relationships in varied scientific areas and particularly in research focusing on the blogosphere (see, for example, Ackland, 2005; Adamic and Glance, 2005; Etling et al, 2010; Thelwall and Park, 2008).

The social network analysis seeks to understand patterns and implications of the relationships between social entities, responding to issues of political, economic or social order. This methodology uses relationships between actors (which can be people, organizations, countries, blogs, etc.) as the unit of analysis. Actors are seen as interdependent and relational ties as channels for the flow of resources (Wasserman and Faust, 1994). Measures of social networks can characterize degrees of influence, prominence or (relational) importance of some elements. The choice of the population for the analysis of social networks may follow, according to Wasserman and Faust (1994: 31-32) a realistic approach (setting boundaries and membership as perceived by the actors themselves) or a nominalist approach that results from the theoretical concerns of the researcher. Regarding this study, we decided for a nominalistic approach, trying to capture a more global picture of the most read political blogosphere, thus focusing on the 20 most read political blogs in the set of the 200 Portuguese blogs with more page views.

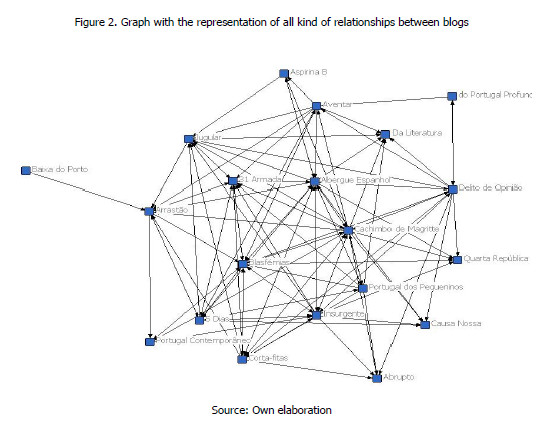

The relations between the 20 most read political blogs were translated into a matrix – a table 1 of double entry that identifies who links to who. The assumption is that in relationships between blogs, the link acts as a recognition of the other as a partner in dialogue – though considering different levels of acknowledgement: an indication of courtesy, rational deliberation (agreeing, disagreeing or adding supplementary information or argumentation) or the expression of disdain and mockery. Data collection resulted from the observations of the links in the period mentioned above (four weeks during 2011). Using the software Ucinet (Borgatti et al. 2002), a non-symmetric matrix (because links are not reciprocal) of the relationships between each pair of blogs was constructed, in which 1 identified the existence of a link between them and 0 the lack of connection. A graph (Figure 2) picturing all the oriented relationships between the blogs was extracted. The orientation of the arrow indicates the direction of the link that may be symmetrical (in the case of blogs that link mutually) or non-symmetrical when blogs only send or receive links. Although this methodology was not used to account for the strength of ties (if ties between blogs happened more than once), this methodology allows us to analyze the structure of the network.

The observation of this image immediately allows to state the central position occupied by blogs more connected with the right and the liberal wing of the Portuguese ideological spectrum: Cachimbo de Magritte, Albergue Espanhol, Blasfémias and 31 da Armada. On the other hand, it is also possible to graphically observe a dense network of relationships, with the sole exception of a blog that clearly occupies a marginal position in the network, Baixa do Porto.

The analysis of social networks is translated by the extraction of measures that allow to understand the structure of the relations between the actors. There are two approaches to the analysis of the network: its characterization and the relational position of actors. In the first case, measures of cohesion are used to provide a characterization of the network and, in the second case, measures of centrality and prestige are the most common. The cohesion of the network is drawn from measures such as density, components analysis and geodesic distances. The more cohesive a network is, the higher the exchange of resources and information flow between actors, as well as the greater the proximity between them.

The density of the network has the maximum value of 1, which is reached when each player is connected to each other. The density of the network of the most read political blogs is 0.300, which already indicates a considerable level of cohesion. Therefore, the set of analyzed blogs represents a relevant community, in which all elements are linked. The component analysis reveals network regions with stronger connections and, in this population, we have a component with 15 of the 20 analyzed blogs. This indicates the existence of a significant number of blogs in large interaction within the network. This network has another five components each consisting of a single blog: four who only received links from other blogs and did not link back (Da Literatura, Abrupto, Causa Nossa e Quarta República) and one that only sent a link but was not linked back (Baixa do Porto). This observation highlights a certain isolation of these blogs. Thus , we realize that we have a relatively cohesive network, with a central core that brings together 15 of the 20 blogs analyzed: a set of interconnected and close blogs, showing that they are listening to each other, to the opinions expressed, sharing interests, themes and issues. Some blogs are more marginal to this core set, being especially targeted by other links, but with no relationships of mutuality in the acknowledgment of others, those ones being Abrupto, Causa Nossa, Da Literatura and Quarta República.

The second angle of a network analysis focuses on the location of its actors, assessing their relational centrality and prestige. This approach allows identifying the most visible or prominent actors, given that the location in the network interferes with the management of resources distribution. One of the measures of centrality is given by the observation of the number of connections (or degrees) of each actor: a central actor is an active one, mastering the ties to others actors. Links can be incoming (if the blog is receiving links) or outgoing (if the blog is sending links). The centrality measured by degrees indicates where action is and, accordingly, indicates which are the most visible actors (Wasserman and Faust, 1994).

The analysis of the centrality measures extracted highlights the Albergue Espanhol as the blog with higher number of connections (14 issued and 10 received), immediately followed by Cachimbo de Magritte (with 23 connections), the player with the highest number of links sent (15). In this sense, Cachimbo de Magritte is the actor linking to the larger number of different blogs, the most active in intertwining its web of opinion. It is the blog with the greater degree of expansiveness (Wasserman and Faust 1994: 126), thus assuming the role of monitoring the network, distributing attention to the rest of the blogs. But when we look specifically for incoming links, a degree which can be used to measure the prestige and popularity of the actors (the most prestigious being the more linked) then Blasfémias (11 incoming ties) is the most relevant blog. It is the most popular blog (Wasserman and Faust 1994: 126) and, in terms of prestigious actors (measured by incoming links), it is followed by the Albergue Espanhol (10) and by the 31 da Armada and Jugular (both with 9).

The central role that actors play in the network can also be gauged by the level of intermediation (Freeman Betweenness Centrality), assuming that a central position allows actors to control the interactions between non-adjacent actors (not directly connected). Actors who are «in the middle» may have greater interpersonal influence over others (Wasserman and Faust 1994: 189). In this study, the actor who occupies the central position is the Albergue Espanhol, followed by the Cachimbo de Magritte and Blasfémias. This means that the Albergue Espanhol, for instance, can quickly drive readers elsewhere in the network via the links they provide.

The analysis of centrality measures confirms the visual observation of the relationships pictured in the graph (Figure 2). Central actors in the political blogosphere are the blogs situated in the liberal and right wing of the ideological spectrum. This happened at the same time when Portuguese political life was preparing a shift in power: the country was preparing elections and a change in the leader party, from Left (socialist party) to Right (social-democrat party). At the same time the right wing was taking over the government, the blogs most related to this ideological wing also assumed the centrality of the most widely read political blogosphere in Portugal. This observation demonstrates the close parallelism between the activity of the blogosphere and the formal and institutional Portuguese political life.

Particularly significant in this setting was the role of Albergue Espanhol – a recently created a blog (in 2010) and already a deactivated one (it ceased its activity in September 2011) –, that brought together people connected with the leader of the opposition party (PSD), Pedro Passos Coelho, who was later elected prime-minister. As it has been observed, this was one of the blogs that established more links to other blogs, building a network of shared ideas and messages and also establishing ties to blogs of other ideologies. On the other hand, this blog was also an important destination in terms of incoming links (the second), with a dynamism that reflects the recognition of the other bloggers. It is the blog «in the middle», which denotes its strategic position in the network regarding the flow of communication (particularly in support to Pedro Passos Coelho). Moreover, the dispersion of the Left also appears to be a relevant factor. While the blogs from the liberal and right wings were linking to each other, the Left blogs were more distant and did not establish much connections between them.

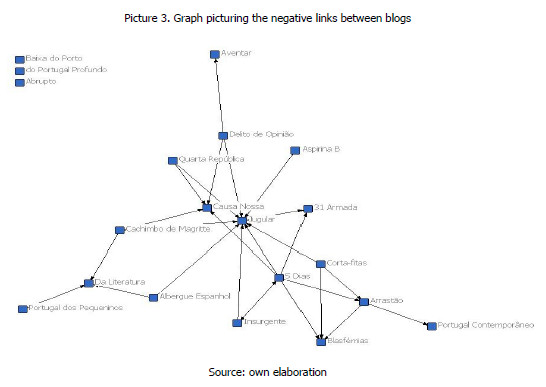

The analysis of the overall structure of the most read Portuguese political blogosphere provides relevant readings in terms of the behavior of the blogs, but it covers all interactions, regardless of the action behind it (neutral, positive or negative). A sharper image of the deliberative potential of the political blogosphere should distinguish between these kinds of interactions, as links with a negative sense do not contribute to the rational deliberation set as necessary to the constitution of a public sphere. Analyzing only the negative links may provide a different picture of this network? To answer this question a second matrix, only using the data on interactions with a sense of contempt or mockery, was built and a new graph was extracted (Figure 3).

The network of political blogs acquires a completely different configuration when only the negative links are considered. It is a more disperse network, with relationships less dense. Three blogs are even out of the web, which means that they did not receive nor issued any negative link (Baixa do Porto, Do Portugal Profundo and Abrupto). The graphic visualization of the network allows also to notice that the geographical distribution of the actors has changed. Links are mostly non-reciprocal, except for the dyads Jugular/31 da Armada and Insurgente/5 Dias – cross-ideological negative dyads that indicate some level of aggressiveness between Left and Right.

This network is much less cohere (cohesion measure of 0.071). Blogs are less dynamic in this kind of links and do not adversely interact with a large number of other projects. The location of the actors in this network is also different, now showing the centrality of the blogs connected to the Left wing. The blog with increased activity and expansiveness in negative relationships is 5 Dias (6 outgoing ties). Other blogs with the highest number of links issued (3) are the Cachimbo de Magritte, Corta-Fitas and Delito de Opinião. It is noteworthy that the Albergue Espanhol, the most active when all connections are considered, has here a more discreet performance: only two outgoing ties. It thus seems that the strategy to support the candidate for prime-minister (Pedro Passos Coelho) followed a more positive interaction. The most negatively popular blog is Jugular (closely connected with the Socialist party), which received nine incoming ties. Another blog commonly attached to the Socialist Party is the blog that follows, Causa Nossa (4).

Again, these centrality measures indicate that, similarly to what happens when analyzing the whole network, the rhythm of the Portuguese political blogosphere closely follows the general environment of the formal and institutional politics. The Socialist Party (whose support was more related to blogs like Jugular, Causa Nossa and Da Literatura) was on the edge of losing elections and the leadership of the country. And when the blogs «in the middle» are identified, Jugular still comes first, but is now closely followed by 5 Dias and Arrastão – two blogs also connected to the Left wing. These are the blogs more targeted by negative interactions, but it is also from the Left that proceeds the higher level of negative interactions: 5 Dias is the blog with greater centrality in terms of expansiveness.

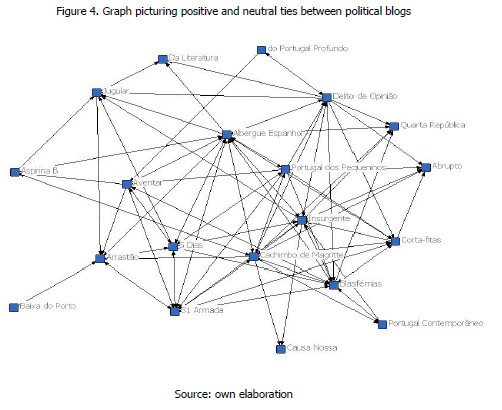

A new question arises from this analysis: does the fact of having the Left wings blogs as the «preferred target» for negative interactions mean that there is a polarization in political blogosphere? Will blogs of similar ideology link only to think-alike projects when it comes to dialogue and conversation, in a deliberative sense? Or, on the contrary, are the blogs of different ideologies also connecting through positive interactions or neutral statements, showing willingness to maintain crossed ideological dialogues? Another matrix for positive and neutral relationship between blogs allowed to obtain the following graph (see Figure 4) that highlights an active interaction between blogs, regardless of their beliefs, and a cross-ideological conversational linking.

This network presents, as the one considering all the kinds of interaction, a substantial density (0.261), meaning that that there is a high level of connectedness. The centrality of network is also occupied by the same actors, the most popular being Blasfémias and Albergue Espanhol (with ten ties each), followed by the 31 da Armada (8 ties). As in the network that considers all kind of interactions, the more expansive blog are Albergue Espanhol and Cachimbo de Magritte (with 13 connections each), followed by Insurgente and Delito de Opinião (with ten ties each).

Concluding remarks

The findings of the social analysis performed allow us to conclude that there is a deliberative environment in the political blogosphere. Portuguese blogs managed by citizens interested in politics do engage in conservations and debates regardless of the ideology. We find right and left wing blogs linking to each other, thus indicating that they share issues and themes of debate, interests, and arguments. Negative ties, that intend to mock or show contempt, insult and hamper dissident voices, are much less intense and do not connect all actors. Thus, we cannot consider that there is polarization in the Portuguese political blogosphere, although there is a greater probability of connection between blogs from the right and the liberal wing. Interestingly, we do not see these strong connections between blogs from the Left wing. In the blogosphere, this ideological wing is more scattered, fragmented and less connected.

The social network analysis also highlights a close correspondence between the formal and institutional political life in Portugal and the online life pictured by blogs activity. This correspondence is visible in the prominence of certain actors on the blogosphere and in the kind of relationships established. Blogs connected with the Right and the liberal wing were more active and central to weave the web of opinion in the blogosphere, while blogs connected with the Left became the main target of negative interactions. This is particularly noticeable in the case of blogs like Albergue Espanhol and Jugular. On the one hand, a network for active and rational deliberation, constituted by positive and neutral interactions, did take place involving all the blogs. However, on the other hand, to a lesser extent, there has been a certain disqualification of some blogs connected to the Left, which were subjected to scorn and contempt - which excludes them from the rationality of deliberation and thus from the political debate and argumentation.

This strategy of exclusion closely followed the election tactics, in a time when Portugal was facing elections and the formation of new government. The prominence of blogs connected with the Right and Liberal wing happened at the same time when a Left party lost the leadership in Portugal. In that sense, although a deliberative public sphere in which different ideologies connected and shared issues, the political blogosphere did not present itself as an alternative forum for the discussion, but mainly a parallel one.

References

Ackland, R. (2005). Mapping the U.S. Political blogosphere: are conservative bloggers more prominent?, Blogtalk Downunder 2005 Conference.

Adamic, L. & Glance, N. (2005). The Political Blogosphere and the 2004 U.S. Election: Divided They Blog, Proceedings of the 3rd international workshop on Link discovery: 36–43.

Baker, C.E. (2007). Media concentration and Democracy – why ownership matters, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

Blumler, J.G. & Coleman, S. (2010). Political communication in freefall: the British case – and others?, The International Journal of Press/Politics 15 (2): 139-154. [ Links ]

Bohman, J. (1996). Public Deliberation, Cambridge: MIT. [ Links ]

Borgatti, S.P.; Everett, M.G. & Freeman, L.C. (2002). Ucinet for Windows: Software for Social Network Analysis. Harvard, MA: Analytic Technologies.

Boulianne, S. (2009). Does Internet use affect engagement? A meta-analysis of Research, Political Communication 26 (2): 193-211. [ Links ]

Bruns, A.; Wilson, J.A.; Saunders, B.J.; Highfield, T.J.; Kirchhoff, L. & Nicolai, T. (2008). Locating the Australian Blogosphere: Towards a New Research Methodology, in Proceedings ISEA 2008: International Symposium on Electronic Arts, Singapore. [ Links ]

Bruns, A. & Adams, D. (2009). Mapping the Australian political blogosphere, in A. Russell & N. Echaibi (Eds.) International blogging: Identity, politics, and networked publics, New York: Peter Lang, 85-111. [ Links ]

Carpentier, N. (2011). Media and Participation, Bristol: Intellect. [ Links ]

Castells, M. (2009). Comunicación y poder, Madrid: Alianza Editorial. [ Links ]

Champagne, P. (2000). Os Média, as sondagens de opinião e a democracia, in Os cidadãos e a Sociedade de Informação – Debates Presidência da República, Lisboa: Imprensa Nacional Casa da Moeda. [ Links ]

Chin, A. & Chignell, M. (2007). Identifying communities in blogs: roles for social network analysis and survey instruments, International Journal of Web Based Communities 3 (3): 345-363. [ Links ]

Couldry, N.; Livingstone, S. & Markham, T. (2010). Media consumption and public engagement – beyond the presumption of attention, Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan. [ Links ]

Dahlberg, L. (1998). Cyberspace and the Public Sphere: exploring the democratic potential of the net Convergence 4: 70-84. [ Links ]

Dahlgren, P. (2005). The Internet, public spheres, and political communication: dispersion and deliberation, Political Communication 22: 147-162. [ Links ]

Dalton, R.J. (2008). Citizen politics: public opinion and political parties in advanced industrial democracies, Washington: CQ Press. [ Links ]

Domingo, D. & Heinonen, A. (2008). Weblogs and Journalism - A Typology to Explore the Blurring Boundaries, Nordicom Review 29 (1): 3-15. [ Links ]

Drezner, D.W. & Farrell, H. (2008). Introductions: Blogs, politics and power: a special issue of Public Choice, Public Choice 134: 1-13. [ Links ]

Esteves, J.P. (2003). A ética da comunicação e os media modernos – legitimidade e poder nas sociedades complexas, Lisboa: Fundação Calouste Gulbenkian. [ Links ]

Etling, B.; Kelly, J.; Faris, R. & Palfrey, J. (2010). Mapping the Arabic blogosphere: politics and dissent online, New Media and Society 12 (8): 1225-1243. [ Links ]

Freire, A. & Meirinho, M. (2009). Reformas institucionais em Portugal: a perspectiva dos deputados e dos eleitores, in A. Freire e J. Viegas (Org.) Representação política – O caso Português em perspectiva comparada, Lisboa: Sextante Editora. [ Links ]

Gil de Zúñiga, H.; Puig-i-Abril, E. & Rojas, H. (2009). Weblogs, traditional sources online and political participation: an assessment of how the Internet is changing the political environment, New Media and Society 11 (4): 553-574. [ Links ]

Habermas, J. (1989). The Structural Transformation of the Public Shpere, Cambridge: MIT. [ Links ]

Hargittai, E.; Gallo, J. & Kane, M. (2008). Cross-ideological discussion among conservative and liberal bloggers, Public Choice 134: 67-86. [ Links ]

Karpf, D. (2008). Measuring influence in the political blogosphere – whos winning and how can we tell, Politics and Technology Review, George Washington Universitys Institue for Politics, Democracy & The Internet. [ Links ]

Koop, R. & Jansen, H.J. (2009). Political blogs and blogrolls in Canada: forums for Democratic deliberation, Social Science Computer Review 27: 155-173. [ Links ]

Leccese, M. (2009). Online information sources for political blogs, Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly 86 (3): 578-593. [ Links ]

Martins, M.M. (2004). Participação Política e Democracia, Lisboa: ISCSP. [ Links ]

McKenna, L. & Pole, A. (2008). What do bloggers do: an average day on an average political blog, Public Choice 134: 97–108. [ Links ]

Moe, H. (2011). Mapping the Norwegian blogosphere: methodological challenges in internationalizing Internet research, Social Science Computer Review 29(3): 313-326. [ Links ]

Moura, L.M. (2009). Assimetrias de comportamentos na blogosfera política portuguesa, dissertação em Sociologia, Lisboa: ISCTE [ Links ]

Papacharissi, Z. (2002). The virtual sphere – the Internet as a public sphere, New Media and Society 4: 9-25. [ Links ]

Park, H.W. & Thelwall, M. (2008). Developing network indicators for ideological landscapes from the political blogosphere in South Korea, Journal of computer-mediated communication 13: 856-879. [ Links ]

Pole, A. (2010). Blogging the Political – politics and participation in a networked society, New York: Routledge. [ Links ]

Reese SD, Rutgliano L, Hyun K and Jeong J ( 2007) Mapping the blogosphere: Professional and citizen-based media in the global news arena. Journalism 8 (3): 235-261. [ Links ]

Scott, D.T. (2007). Pundits in Muckrakers clothing: political blogs and the 2004 U.S. Presidential Election, in M. Tremayne (ed.) Blogging, citizenship, and the future of media, New York: Routledge. [ Links ]

Silva, F.C. (2002). Espaço Público em Habermas, Lisboa: ICS. [ Links ]

Sunstein, C.R. (2008). Neither Hayek nor Habermas, Public Choice 134: 87-95. [ Links ]

Tremayne, M. (2007). Harnessing the active audiences: Synthesizing blog research and lessons for the future of media, in M. Tremayne (Ed.) Blogging, citizenship, and the future of media, New York: Routledge. [ Links ]

Vos, T. P.; Craft, S. & Ashley, S. (2012). New media, old criticism: Bloggers press criticism and the journalistic field, Journalism 13(7) 850–868. [ Links ]

Wasserman, S. & Faust, K. (1994). Social Network Analysis – Methods and applications, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

Woodly, D. (2008). New competencies in democratic communication? Blogs, agenda setting and political communication, Public Choice 134: 109-134. [ Links ]

Date of submission: February 18, 2014

Date of acceptance: July 23, 2014

NOTES

1 This research was supported by the Fundação para a Ciência e Tecnologia and co-funded by the European Social Fund in the framework of the Programa Operacional Potencial Humano (POPH) of QREN (SFRH / BD / 45400 / 2008).

2 Portuguese site that ranks blogs according to page views counted by the Sitemeter technology; this site was discontinued and a new ranking is now provided by the blog Aventar

Annex A