Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Acessos

Acessos

Links relacionados

-

Similares em

SciELO

Similares em

SciELO

Compartilhar

Observatorio (OBS*)

versão On-line ISSN 1646-5954

OBS* vol.8 no.4 Lisboa dez. 2014

Critical but co-operative – Netizens evaluating journalists in social media

Elina Noppari*, Ari Heinonen**, Eliisa Vainikka***

* Researcher at Tampere Research Centre for Journalism, Media and Communication, FI-33014 University of Tampere, Finland. (elina.noppari@uta.fi)

** Professor of Journalism, University of Tampere, Kalevantie 4, Tampere, Finland. (ari.a.heinonen@uta.fi)

*** Researcher at Tampere Research Centre for Journalism, Media and Communication, FI-33014 University of Tampere, Finland. (eliisa.vainikka@uta.fi)

ABSTRACT

This article looks into the relationship between professional journalists and active Web users in the sphere of social media1. Our exploration into journalists social media participation is approached through two clashes of cultures between the online context and the world of journalism, namely anonymity and transparency. The research, which is based on interviews with journalists and experts and a survey to the web users, permits the conclusion that the relation between journalists and public is fraught with suspicion and conflict. Newsrooms should be more open as regards journalistic practices, but frequently they are not accessible to the public.

Keywords: Journalists, social media, netizens, crowdsourcing

1. Introduction

Social media and networked online spaces have recently occasioned change in the ways of doing journalism such that one has begun to speak of journalism among other things as serving the public (Artwick, 2013), as ambient (Hermida, 2010), as dialogue (Gillmor, 2004) or blur next journalism (Kovach and Rosentiel, 2010). All these terms refer to the Internet as a complex communication environment in which web users themselves write, recommend, share and comment on content, producing also parallel publicities that challenge journalism, which has traditionally dominated the public agenda. Nick Couldry (2009) claims that the traditional mass communication paradigm is undergoing change as the public are gradually becoming active sender-receiver hybrids and Manuel Castells (2009) refers to the same development by talking about mass self-communication, in which anyone can target a large following with the help of peer networks.

Social media are, according to Andreas Kaplan and Michael Haenlein (2010), a group of Internet applications that build both the ideological and technological base of Web 2.0, and allow the creation and exchange of user-generated content. With the arrival of network journalism (Heinrich, 2008) the roles of both the public and the journalists have changed. The public have more opportunities than before to choose how and where they consume journalistic products and many news items first circulate in the social media before ending up in the traditional media (Heinonen, 2011; Hermida, 2010). Newsrooms have generally reacted to these changes by encouraging journalists to be users of social media. From the perspective of journalism, social media have been perceived as significant, particularly as a facilitator and enabler of interaction with the public. Media enterprises may strive to survive amid intensifying competition by using co-creation, crowdsourcing and open dialogue and by building audience communities and fan groups. The web is also a potential source of subjects for stories and background information and increasingly a channel for the journalists' self-branding and promotion. Social media is all the more often used to present ones own work achievements and therefore ones own personality is also foregrounded (e.g. Hedman and Djerf-Pierre, 2013; Lehtonen, 2013; Noguera-Vivo, 2013).

Although all journalists have access to easy-to-use technologies, using social media takes more investment than merely registering for certain services. In other words, creating a blog or a Facebook profile does not yet mean that the journalist is operating in social media in a professionally productive manner. For every popular blog there are countless unread blogs and a person casually going online seldom succeeds in initiating worthwhile interaction. The Internet at large can be conceived of as a peculiar type of publicity where audience mechanisms differ from those of the traditional, off-line media. In order to function purposefully in social media, a journalist must achieve credibility by being present in the web as a genuine participant. In this article we use empirical data to scrutinize what the actions of journalists seem like in practice and in what endeavours and how productively they are present in the various social media environments.

Journalism and the web both entail a culture and parlance built on certain practices. Journalism, built on the traditional, one-way dissemination of information, has emphasized the significance of the institution as an impartial and truth-seeking producer of information, whereas on the Web the norms spring from an opposing line of thought and still to this day reflect the principles of hacker culture. An important part of the journalists professional identity is the notion of them being not only independent professionals but also representatives of the public and watchdogs of those in power. Traditional journalism rests on authorized and hierarchical sources and emphasises the quality of its own work (Helberger, Leurdijk & de Munck, 2010; Örnebrink, 2008). At the heart of journalism lies the notion of the journalist as a gatekeeper (Singer, 2008). The norms of the Internet emphasise freedom of information and oppose any attempt to regulate peoples access to sources of information or to limit their activities on the Web. Opposition towards authority, e.g. the state, academia or a commercial actor, frequently arises online. The core values on the web are direct democracy, freedom of speech, rights of the individual and transparency of governance. (Gerbaudo, 2012; Levy, 2010.) In the Internet anonymity has traditionally been a value to be vehemently defended, as it is seen to ensure equality. Achieving a high rank in an online community is not necessarily based on traditional social categories, as is for example professional status, but by investing in the good of the community in a way that the community approves of (cf. Green and Jenkins, 2011; Kollock, 1999).

In this article we contemplate how well the views of journalists and netizens coincide in the use of social media. Are the journalists practices in the Internet such that they would motivate active web users to commit to be an audience community, to interact and co-operate with journalists? And are the web users or journalists actually inclined to such co-operation? Our preliminary hypothesis is that a clash of cultures, develops as journalists and netizens come across each other in various online spaces. This clash of cultures, or lack of shared understandings, results in differences in ideologies and actions.

In journalism studies, most research (Lehtonen, 2013; Nikunen, 2011) has focused on journalists perceptions of their social media use or the content found on journalistic web sites. In our study we also wanted to look at journalists' appearance in social media from the perspective of those who meet them online: active web users, the so-called netizens. The online presence of journalists and their actions in social media were presented to web users for assessment in the hope of arriving at a new perspective that would complement earlier research on journalists own views and actions and the use of social media content in journalism.

First, we present the methods and data used in this article, and then we proceed to look into the two illustrative examples of clashes of cultures2 in journalism and online communication. We study how both journalists and web users assess journalists actions in social media. Finally we consider what all this may signify for journalism and for the professional identity of journalists altogether.

2. Methods and data

The data used in this article was gathered in a study of journalists´ online presence and social media use conducted in 2012–2013. An anonymously completed online survey (n = 248) was distributed both through the researchers own Facebook profiles and also directly to 19 Finnish Internet discussion forums. The survey posed open-ended questions and multiple-choice questions on the Finnish mainstream media, social media, journalists and the Internet culture. The responses to the open-ended questions were analysed coding the emerged themes by sub themes and categories.

Our aim was to obtain as many different respondents as possible by distributing the survey link to forums presumably attracting different user groups. Nevertheless it should be born in mind that the respondents, referred to here as netizens, were after all predominantly male (74 % of respondents), with differing educational backgrounds and from different age groups. We are aware that the term netizen is problematic to some degree, as a part of the vocabulary of digital culture, and has lost some of its meaning in the recent years. Here, by referring to netizens, we mean those individuals who have positioned themselves as active Web users. They were heavy Internet users: nine percent used the web as much as ten hours per day. They were also firmly in favour of freedom of information with liberal conceptions of freedom of speech. The survey was distributed mostly in anonymous online communities and thus it can be assumed that the responses of this group reflect specifically the norms and conceptions of an anonymous Internet culture. Therefore the conceptions of the respondents may differ from the studies conducted in non-anonymous environments, such as Facebook or Twitter, where the individual is emphasised. The survey respondents are not average media users and their opinions are not generalizable as such, but they represent those especially active individuals who journalists encounter when operating online, and thus their conceptions of journalists' online presence are relevant.

In addition to the survey we interviewed journalists (n=10) and social media professionals (n=7) in both Finland and the UK, six and four journalists, respectively. We selected for the interviews so-called early adopters who at a relatively early stage made professional use of social media services. The interviews were transcribed and analysed by coding the original themes to smaller subcategories.

3. Illustrative examples of cultural clashes: Anonymity

The clashes of cultures between journalism and the culture of the Web can be approached through two concepts, anonymity and transparency, which were present both in the parlance of the netizens and the journalists.

Tensions between journalists and netizens frequently mount around the issue of anonymity. For the media companies anonymity on the web frequently poses a problem where anonymous writing undeniably involves misconduct. Journalists seldom attach much worth to anonymous writing, let alone that they would themselves participate in anonymous online discussions (Heinonen, 2008). According to Bill Reader (2012), journalists often see anonymous online discussion as filth and as a vehicle for bullying and trolls, which are frequently more bother than benefit to media brands. In Finland, also, the journalists attitude to the discussion forums of their own medium or online discussions in general is contradictory. Journalists consider online discussion to be hostile and irrelevant (Nikunen, 2011). The comment sections of online news have been said to also provide the public with a place as an audience, when these comments do not actually pose a threat to the professional identity of the journalist (Domingo et al., 2008; Reich, 2011; Thurman and Hermida, 2008).

Our research confirmed the results of previous studies, as the journalist in our study described a negative discussion atmosphere in the discussion forums as follows:

It is somehow so tiring, there in our discussion forums. I regularly succumb to going there, thinking now its a good time to have some contact with the readers, but it (the aggressive discussion) always manages to kill the enthusiasm and I always swear that I will not go there again, let them shout there by themselves. (Journalist interviewee, male, Finland)The interaction between us and readers is minimal [--] every time I go to our discussion forum, I remember no, dont do this again, because it always starts an awful uproar and its somehow really aggressive, the crowd there. (Journalist interviewee, male, Finland)

People can leave comments on our stories and the idea is that the journalists would be able to talk back and justify the stories and get involved in a debate but they dont tend to do that. You know, quite often the journalists will get criticized and it would be great if the journalists could go on and defend their stance and explain it, because then the user is getting such a more rich experience, but its just difficult because usually, once a journalist gets criticized theyll just switch the comments off and think theyre a bunch of idiots (Journalist interviewee, male, UK)

Some journalists are very careful in what they say or do online, because of the aggressive commentators, as this female UK journalist explains: I think it goes back to not adding too much personality, too much opinion – just reporting. Because I think that things can get misconstrued online and once you put it out there, you cant take it back. Many media companies have tightened the moderating practices of their web pages and may have prevented anonymous comments in order to comply with the requirements of the legislation, the ethical guidelines, to improve the quality of the discussions or to protect their brand. (Binns, 2012; Heikkilä, Ahva, Siljamäki & Valtonen, 2012.)

Among the netizens, however, this is frequently viewed as proof that the discussion has been suppressed and even as an attempt at censorship. (cf. Haara, 2012; Masip, Diaz Noci, Domingo, Lluís Micó & Ruiz, 2010; Trygg, 2012.) For those supporting an anonymous and uninhibited Web the mainstream media do easily represent a gatekeeper to free discussion motivated by the pursuit of financial gain and hand in glove with the powerful in society. The aim of the mainstream media is never seriously undermine order in society or to profoundly further societal change (McQuail, 2005), but it can be seen as a part of the system of authority sustaining the status quo, and this should be regarded with suspicion. Of our survey respondents 78 percent said that their own online communities approach issues from mainstream media with suspicion or criticism.

Our survey respondents highly favoured the option for anonymity – it was linked both to the freedom of the individual and to the realization of democracy. Of the respondents 92 percent thought that anonymous writing enables a free discussion and critical speech against power structures, and 87 percent were of the opinion that regardless of anonymity the web offered opportunities for appropriate discussion of high quality. Anonymity is frequently associated with the downsides of the Internet and for many it is synonymous with bad behaviour, offensive mode of expression, hate speech, trolling and downright crime (e.g. Barnes, 2003; Pöyhtäri, Haara & Raittila, 2013; Shirky, 1995). The positive side of anonymity is that it enables discussion on sensitive and politically debatable subjects. Anonymous communities are frequently creative and innovative as when writing under pseudonyms there is no fear of failure which would inhibit ideation and writing. (Bernstein et al., 2011; Stromer-Galley and Wichowski, 2011.)

4. Transparency as a value and as a concept

Openness and transparency were concepts our respondents, both journalists and netizens, often referred to as being important values in the social media. As a concept transparency is abstract, it is necessary to give it a closer look. The study by Richard Van Der Wurff and Klaus Schönbach stressed transparency as a new journalistic norm in the reporting process (2011, p. 412, 417). According to José Manuel Noguera Vivo (2013) there are several examples of how with Twitter the newsroom becomes more transparent and contact with the public has accelerated. For example, editors-in-chief solicit opinions in Twitter on headlines and subjects for articles.

Michael Karlsson (2010) proposes that the concept transparency should be rendered comprehensible by splitting it into more concrete transparency rituals, which could be used in newsroom work. Karlsson uses disclosure transparency to refer to openness on the part of newsmakers with reference to selection criteria and production. Participatory transparency for its part is used to refer to the fact that the public has the option of participating in the news process and its various stages. (Ibid., p. 537.) Transparency might mean that in both inside and outside of the journalism institution, people might be given an opportunity to monitor, criticize, check and even intervene in the journalistic process. Axel Bruns (2004) takes the view that a user should be able to intervene in every stage of the news production process, from the ideation of subject and collection to publication, analysis and discussion. For example, the truth produced in blogs is based on dialogue which instantly self-corrects and complements the original text (Karlsson, 2011, p. 284).

In work by Dominic Lasorsa, Seth Lewis and Avery Holton (2012), journalists also used Twitter as an opportunity to provide accountability and transparency. In their tweets journalists discuss their work, have conversations and share links. However, they don´t usually open the journalistic process in Twitter to those outside of journalism. According to José Manuel Noguera Vivo (2013) achieving trust and credibility is one of the journalists first challenges in Twitter. In order to create a good relationship with the public and thereby to obtain tips and derive benefit from social media, journalists should, according to Noguera Vivo, offer in Twitter something other than merely reiterating news headlines. The social media experts we interviewed spoke in favour of a similar approach: journalists should build a distinctive and easily approachable online presence and preferably create a profile as a specialist in a certain area of expertise.

The pioneer journalists in social media stressed in the interviews the importance of answering to the public and the ability to take and utilize negative feedback, for example, in developing a journalistic product. The social media experts also expressed the hope that journalists might be able to participate more in critical discussion on their work. Journalists should therefore accept both positive and negative feedback and to openly declare her role as a journalist when fishing for information in the Internet. Openness was seen as one means by which to cultivate a good reputation in the web.

The interviews we conducted reveal that transparency is a central value within the sphere of social media. Heikki Heikkilä and Jari Väliverronen (2013), however, make the point that in spite of ample talk about transparency and accountability, little has been done in Finnish newsrooms for the development of practices supporting transparency. They stress that the norm of transparency should be scrutinized in practice in three separate stages: 1) actor transparency (for example ethical principles and ownership relations and journalistic objectives), 2) production transparency (internal decision-making or processes of newsgathering) and 3) responsiveness (the practices after publication, such as reactions to errors and feedback and participating in discussion). In their study only a little over half (57 %) of journalists were, for example, in favour of making public the internal guidelines of the media organization. (Ibid.)

Our data also includes an example of failed production transparency in which a Finnish journalist recounted having been subjected to a reprimand by the editor-in-chief on reporting too much in Twitter about a certain editorial decision.

In (the editor-in-chiefs) opinion it was an extremely bad idea, the readers they ask all sorts of things, but theres no need to always go and explain, and so then they were never answered. (Journalist interviewee, male, Finland)

In our survey the netizens spoke strongly for freedom of information and of expression. The journalists we interviewed and the netizens were thus unanimous that transparency was the way for journalism to operate through social media. However, the responses of web users served to confirm the observations of Heikkilä and Väliverronen (2013) that openness is currently more of a slogan than a social media practice guiding the work of journalists.

The netizens emphasized that newsrooms should greatly increase their transparency at all stages of the journalistic process. At the level of actor transparency they emphasised that the media companies ought to be more open about their policies and the values and opinions of individual journalists. Of the respondents 52 percent were of the opinion that journalists should clearly indicate in the social media for example their political position. The netizens considered that being frank about ones political position was a sign of credibility, as many of the respondents did not seem to believe in the notion of an impartial professional journalist. The members of the public hoped that in the production stage journalists would openly present their work processes, the sources they used and, for example, provide links to the original materials. On the Web the overall picture of an event is often built by piecing together fragmental bits of information. There is often also false information included, as in the case where Reddit users tried to collectively track down the Boston Marathon bombers in April 2013. In these cases the solution, and all the steps leading to it, are publicly available and for people who are accustomed to this kind of dissemination of information, so an item of news without any links or additional information about the sources may feel dubious.

(There ought to be) links to the original sources of the information: to research, reports, minutes of meetings, original interviews / written contributions, memos. In subject with a great deal of substance the media always have to make things banal and simplify them, but in an online discussion one can delve deeper and really get into it. (Response to an open-ended question)

The quote above shows how in various online communities there is a great desire to engage in investigative work on the subjects addressed in the media (cf. Jenkins, 2008, p. 28–29), and also to evaluate the contribution of the journalist. According to Van Der Wurff and Schönbach (2011) the public should be offered an opportunity to ascertain whether the information provided by the media is correct or not. People invest a lot of time and effort online in following themes that interest them. The survey respondents devoted time to seeking information on the subjects that interest them in other places than the traditional media and, for example, in international subjects they often relied on other sources than their domestic media.

5. Critical voices from the Web

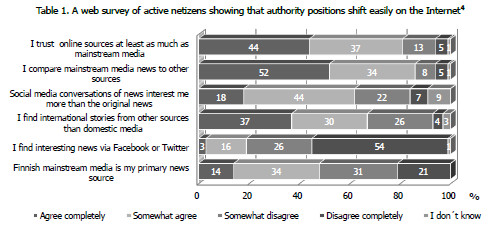

It should be born in mind that the respondents to our survey are not average media users, but typically they form critical publics (see Table 1)4. This becomes apparent among other places in the extent to which they used traditional media as a source of news or how they frequently sought alternative perspectives on the news presented by mainstream media. They obtain information from fragmented sources and the authority positions on which journalism traditionally relies, easily disintegrate in the Internet. Over 80 percent of respondents reported, for example, relying just as much on unofficial online sources known to them to be good as on the news presented by mainstream media.3They enjoy assuming the position of the watchdogs watchdog (cf. Cooper, 2006) or the fifth estate (Dutton, 2009): many discussion forums have separate areas focused on different issues of the media in which users discuss news and practices of traditional media.

To sum up the netizens attitudes towards journalism, in the survey responses web users considered mainstream media journalists social media lurkers more than active participants. According to the netizens the main challenge as regards journalists use of social media would appear to be that they do indeed use the services of social media for different purposes but seldom spend enough timein them to learn, for example, to act according to the rules of the community. Certainly this is connected not only to the journalists professional attitudes and practices but also to media economy, and to the fact that many newsrooms have suffered drastic cuts in personnel.

One respondent described the journalists as sitting in the social media grandstand, from which they then easily make misinterpretations. For these reasons journalists may misjudge the context and tone of online discussions, and fail, for example, to recognize irony, satirical text or trolling. The respondents to the questionnaire cited examples in which Finnish journalists had, for example, publicized fake Twitter profile updates in the name of a public figure as genuine.

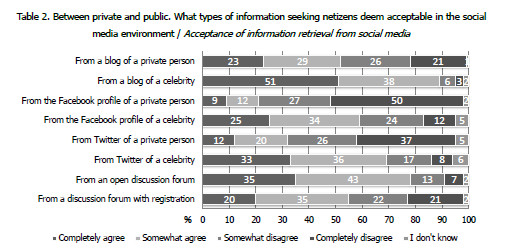

Although the web users deemed it a good thing that journalists should try to seek information and new perspectives from various forums, they pointed out that journalists should make their presence known and request permission to publish things. This demand may be considered somewhat inconsistent, as the users themselves wish to remain anonymous, whereas they hope for the journalists to come forward as media professionals. A study on BBC journalists found that the journalists frequently regarded the content produced by netizens as raw material (Wardle and Williams, 2010). This does not go down well with web users: they stress that even those writing in the anonymous forums are individuals who invest effort in the activities of their pseudonyms.

The situation of social media midway between private and public for its part gives rise to tensions between web users and journalists in search of information. Many social media platforms promise privacy, and an attempt is made to create a sense of being at home and people are encouraged to express themselves freely (Sloop and Gunn, 2010). However, they may be on view to a surprisingly extensive number of people. Thus journalists may, for example, use information from Facebook, possibly considered private by the source her/himself, as Facebook is often perceived as a private and personal area (cf. boyd, 2008). The netizens criticized how news picked up from social media emphasize scandals and the journalists are tempted to resort to lazy political journalism, for example, by exposing politicians or other public figures controversial or private social media updates.

The netizens criticism very often after all falls on the traditional journalistic values and their abandonment. This finding is similar to that in the study by Vos, Craft & Ashley (2012), in which bloggers criticized the conventional media for inaccuracy and a lack of independence. The bloggers also found cause for complaint in the journalists consideration of news, sensationalism and lack of a professional approach.

6. Signs of productive co-operation

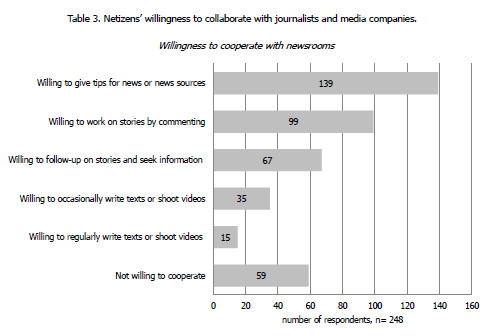

Despite their critical stance, the netizens were occasionally willing to share their contributions with the journalists and this is a resource which journalism can ill afford to lose. Most of the respondents were ready to collaborate with a fairly loose commitment, but 27 percent of them reported that they were willing to monitor certain subjects regularly as aid to the newsrooms and to seek information for the journalists. The netizens have issues about which they are passionate, convictions and endeavours to exert influence (which is what motivates them to operate in social media). Therefore the idea of crowdsourcing works well in theory, but in practice the problems of bias, misleading and trolling appear. The journalist might not meet the right crowds at all, but noisy, unmanageable people who do not resemble her ideal readers.

As Tanja Aitamurto (2013) points out, typical journalistic work flow does not function seamlessly when working with the crowd because the journalist cannot predict the quality and amount of the readers input. Oftentimes the final outputs of the public are not of adequate quality (Helberger et al., 2010) but they may serve as a resource in information retrieval.

In order for journalists and active web users to interact, the journalist should be ready to participate in the discussion concerning their work. For example in the study by Heikkilä and Väliverronen (2013), as many as 80 percent of the journalists involved noted that the newsrooms should actually require journalists to respond to feedback received and also our journalist interviewees were at least in principle positively disposed towards feedback. However, in the netizens experience journalists did not respond to feedback addressed to them, the more so if this was critical in nature. Moreover, changes made as a result of feedback on an item published in the net might be made without mentioning the changes made. Many respondents had already formed the opinion that there was no point in seeking interaction with a journalist and that this made no difference.

Respondents to the web survey reported following journalists actions in social media mostly through the discussion forums of the media companies and linked items to other discussion forums. Ten percent of respondents reported following the journalists Twitter updates or Facebook activity. On the other hand the journalists blogs had reached 35 percent of the netizens. What fascinated the respondents about the blogs was on the one hand that they served to convey the journalists own views and on the other that the journalists responded to the comments on the blogs more frequently than they did to other contacts. Although a great deal of discussion on journalism takes place on the web, most of this never reaches the journalists and they do not take part in it as journalists.

The discussion forums we followed while conducting our research showed that when a journalist makes an exception and ventures to join the discussion, she is frequently received enthusiastically even in forums which could be classified as critical of the media. For example, in a Finnish anti-immigrant discussion forum some users defended the journalist who joined in when the discussion was at risk of becoming inappropriate.

Dont get nasty if somebody from YLE (Finnish Broadcasting Company) joins in for once in Homma, please. I myself will use the opportunity to propose an idea for a programme... (Comment in the Homma discussion forum, April 2013)

Entering the forum does indeed require of the journalist a healthy professional confidence as, for example, it is customary in the above-mentioned forum to publish and discuss things that are found on the web about the person. Online communities often include strong subjective views and affective elements, whereas journalism is considered rational and objective.

7. Conclusions

In this paper we wanted to ascertain whether journalists social media work practices are such that they motivate active net users to commit as audience communities and engage in collaboration with journalists, and whether the parties are even desirous of such interaction.

Our data show that relations between professional journalists and netizens appear at present to be somewhat contradictory. On the one hand the journalists are compelled in this fluid modern (Bauman, 2000) age to justify their role and modes of action to the public more weightily, while the public is more critically, even hostilely, disposed to journalists as a professional group. The journalists are compelled to acknowledge that from the perspective of the public, or a large part of it, the work of journalists is not as important as it used to be as regards following public events. Both netizens and social media pioneers would like to see greater transparency on the part of journalists in social media. The journalists should sometimes turn the spotlight on themselves. Self-coverage complements the usual news coverage and public self-reflection on journalistic practices and methods creates trustworthiness.

On the other hand the journalists find themselves faced with new opportunities. Although some netizens would prefer to remain aloof from journalism and assume the voice of a critical counterculture, another group, albeit critical, would like to collaborate with journalists. The willingness of the netizens to engage in co-operation may be founded on a realistic assessment of the situation: the journalistic organizations of the mainstream media have at their disposal resources so large that they might be impossible for one person to grasp, in which the netizens would like to have a say regarding their use. It would appear that in social media, too, the notion of an established correct publicity residing in the traditional media still persists. The mainstream media serves as a confirmer of information putting an end to rumours circulating online. The role of the journalist will also remain important in how the information is presented in a clear and coherent manner which all of the amateur producers may not have the abilities to do. Traditional mainstream media maintains its role especially in times of crisis when the diverse audience segments have been seen to approach the center of high-brow media and each other in their ways of using different media (Westlund and Ghersetti, 2013).

The lack of time and sufficient internet literacies has also been seen as a hindrance to the effective use of social media in journalism. As Helberger et al. (2010) mention, discussion amongst all the different players in the field, from individual journalists to media companies, legislators and amateur producers, should take place to determine how the encounter between mainstream and independent amateur media would happen so that it would be beneficial to both. Helberger et al. also highlight the importance of internet skills and media literacy, not only for the young, but across all demographic levels of society.

In such a transitional situation it would be useful for the journalism professionals to build a genuinely interactive connection to the netizens. A service orientation has been put forward as a solution for better journalism (e.g. Artwick, 2013; Usher, 2012). The findings of our research interviews support observations that in social media in particular taking note of and serving the public is important. One of the social media pioneer journalists in a Finnish television news programme (created interactively with the help of social media), described their attitude as we are here for you, if you need us. The social media experts already serve their audience, the followers they have accumulated: I have to really serve my Twitter audience (Interview with a social media producer in journalism, male, Finland). Out of these kinds of relationships purposeful networks can grow that are useful for professional journalists – if journalists appreciate the communities and actively take part in them instead of lurking. As Megan Knight and Clare Cook (2013, p. 3) have pointed out, in this ecology journalism trades on participation rather than a top-down approach. They aptly state that this is a culture of collaboration, not co-optation. What is important is that netizens expect transparency. Thus journalists have to open up while doing journalism; they need to explain people what they are doing and how they are doing it. The result can benefit the public at large.

References

Aitamurto, Tanja. (2013). Balancing Between Open and Closed. Digital Journalism 1(2), 229–251. [ Links ]

Artwick, Claudette. (2013). Reporters on Twitter. Digital Journalism 1(2), 212–228. [ Links ]

Barnes, Susan. (2003). Computer-Mediated Communication: Human-to-Human Communication across the Internet. Boston: Allyn and Bacon. [ Links ]

Bernstein, Michael, Monroy-Hernandez, Andrés, Harry, Drew, André, Paul, Panovich, Katrina & Vargas, Greg. (2011). 4chan and /b/: An analysis of Anonymity and Ephemerality in a Large Online Community. In Proceedings of the 5th International AAAI Conference on Weblogs and Social Media, Barcelona, 50–57.

Binns, Amy. (2012). Don´t feed the Trolls! Managing troublemakers in magazines´online communities. Journalism Practice 6(4), 547–562. [ Links ]

Bauman, Zygmunt. (2000). Liquid Modernity. Cambridge: Polity Press. [ Links ]

boyd, danah. (2008). Facebooks privacy trainwreck. Convergence: The International Journal of Research into New Media Technologies 14(1), 13–20. [ Links ]

Castells, Manuel. (2009). Communication Power. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

Cooper, Stephen, D. (2006). Watching the Watchdog. Bloggers as the Fifth Estate. Washington: Marquette Books. [ Links ]

Couldry, Nick. (2009). Does the Media Have a Future? European Journal of Communication 24(4), 437–449. [ Links ]

Domingo, David, Quandt, Thorsten, Heinonen, Ari, Paulussen, Steve, Singer, Jane & Vujnovic, Marina. (2008). Participatory Journalism Practices in the media and beyond: an international comparative study of initiatives in online newspapers. Journalism Practice 2(3), 680–704. [ Links ]

Dutton, William H. (2009). The Fifth Estate Emerging through the Network of Networks. Prometheus 27(1), 1–15. [ Links ]

Gerbaudo, Paolo. (2012). Tweets and the Streets. Social Media and Contemporary Activism. New York: Pluto Press. [ Links ]

Green, Joshua & Jenkins, Henry. (2011). Spreadable Media: How Audiences Create Value and Meaning in a Networked Economy. In Nightingale, Virginia (ed.) The Handbook of Media Audiences. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing Ltd, 109–128. [ Links ]

Haara, Paula. (2012). Poliittinen maahanmuuttokeskustelu Helsingin Sanomien verkkokeskustelussa. In Maasilta Mari (ed.) Maahanmuutto, media ja eduskuntavaalit. Tampere: Tampere University Press, 52–87. [ Links ]

Hedman, Ulrika & Djerf-Pierre, Monica. (2013). The Social journalist: Embracing the social media life or creating new digital divide? Digital Journalism 1(3), 368–385. [ Links ]

Heikkilä, Heikki, Ahva, Laura, Siljamäki, Jaana & Valtonen, Sanna. (2012). Kelluva kiinnostavuus. Tampere: Vastapaino. [ Links ]

Heikkilä, Heikki & Väliverronen, Jari. (2013). Transparency - the New Objectivity? Journalist´s Attitudes towards Openness and Audience Interaction in Finland. Presentation in Nordmedia Conference, Oslo, August 2013.

Heinonen, Ari. (2008). Yleisön sanansijat journalismissa. Tampere: Journalismin tutkimusyksikkö.

Heinonen, Ari. (2011). The Journalist´s Relationship with Users. New dimensions to conventional roles. In Singer, Jane, Hermida, Alfred, Domingo, David, Heinonen, Ari, Paulussen, Steve, Quandt, Thorsten, Reich, Zvi &Vujnovic, Marina (eds.) Participatory Journalism. Guarding Open Gates at Online Newspapers. Malden, MA: Wiley-Blackwell, 34–55.

Heinrich, Ansgard. (2008). Network Journalism: Moving towards a Global Journalism Culture. Paper in RIPE conference Mainz Oct 9-11 2008. Available online: http://ripeat.org/wp-content/uploads/2010/03/Heinrich.pdf

Helberger, Natali, Leurdijk, Andra & de Munck, Silvain. (2010). User generated diversity Some reflections on how to improve the quality of amateur productions. Communications & strategies 77, 1st Q 2010, 55. [ Links ]

Hermida, Alfred. (2010). Twittering the News. The emergence of ambient journalism. Journalism Practise 4(3), 297–308. [ Links ]

Jenkins, Henry. (2008). Convergence culture: Where old and new media collide. New York: New York University Press. [ Links ]

Kaplan, Andreas & Haenlein, Michael. (2010). Users of the World, Unite! The challenges and opportunities of social media. Business Horizons 53(1), 59–68. [ Links ]

Karppinen, Kari, Jääsaari, Johanna & Kivikuru, Ullamaija. (2010). Media ja valta kansalaisten silmin. SSKH Notat – SSKH Reports and Discussion papers 2/2010. Helsinki: Helsingin yliopisto. [ Links ]

Karlsson, Michael. (2010). Rituals of transparency. Journalism studies 11(4), 535–545. [ Links ]

Karlsson, Michael. (2011). The immediacy of online news, the visibility of journalistic processes and a restructuring of journalistic authority. Journalism 12(3), 279–295. [ Links ]

Knight, Megan & Cook, Clare. (2013). Social media for journalists. Principles and practice. London: Sage. [ Links ]

Kollock, Peter. (1999). The economics of online cooperation: Gifts and public goods in cyberspace. In Smith, Marc & Kollock, Peter. (eds.) Communities in Cyberspace. London: Routledge, 219–241. [ Links ]

Kovach, Bill & Rosenstiel, Tom. (2010). Blur:How to Know What's True in the Age of Information Overload. New York: Bloomsbury. [ Links ]

Lasorsa, Dominic, Lewis, Seth & Holton, Avery. (2012). Normalising Twitter. Journalism Practice 2(1), 19–36. [ Links ]

Lehtonen, Pauliina. (2013). Itsensä markkinoijat Nuorten journalistien urapolut ja yksilöllistyvä työelämä. Tampere: Tampere University Press. [ Links ]

Levy, Steven. (2010). Hackers. Heroes of the Computer Revolution. California: O´Reilly Media. [ Links ]

Masip, Pere, Diaz Noci, Javier, Domingo, David, Lluís Micó, Josep & Ruiz, Carles. (2010). Comments in News, Democracy Booster or Journalistic Nightmare: Assessing the Quality and Dynamics of Citizen Debates in Catalan Online Newspapers. Paper presented in IAMCR 2010. Available online: http://www.lasics.uminho.pt/ocs/index.php/iamcr/2010portugal/paper/view/614

Matikainen, Janne. (2010). Perinteinen ja sosiaalinen media - Käyttö ja luottamus. Media & viestintä 33(2), 55–70. [ Links ]

McQuail, Dennis. (2005). McQuail´s Mass Communication Theory. (5th ed.) London: Sage. [ Links ]

Nikunen, Kaarina. (2011). Enemmän vähemmällä. Laman ja teknologisen murroksen vaikutukset suomalaisissa toimituksissa 2009–2010. Tampere: Journalismin tutkimusyksikkö, Tampereen yliopisto. [ Links ]

Noguera Vivo, José Manuel. (2013).How open are journalists on Twitter? Trends towards the end-user journalism. Communication & society 26(1), 93–114. [ Links ]

Pöyhtäri, Reeta, Haara, Paula & Raittila, Pentti. (2013). Vihapuhe sananvapautta kaventamassa. Tampere: Tampere University Press. [ Links ]

Reader, Bill. (2012). Free Press vs. Free Speech? The Rhetoric of Civilicity in Regard to Anonymous Online Comments. Journalism & Mass Communication Quaterly 89(3), 495–513. [ Links ]

Reich, Zvi. (2011). User comments. The transformation of participatory space. In Singer, Jane, Hermida, Alfred, Domingo, David, Heinonen, Ari, Paulussen, Steve, Quandt, Thorsten, Reich, Zvi & Vujnovic, Marina (eds.) Participatory Journalism. Guarding Open Gates at Online Newspapers. Malden, MA: Wiley-Blackwell, 96–117.

Shirky, Clay. (1995). Voices from the Net. Emeryville, California: Ziff-Davis Press.

Singer, Jane (2008). The Journalist in the Network. A Shifting Rationale for the Gatekeeping Role and the Objectivity Norm. Tripodos 23, 61–76. [ Links ]

Sloop, John & Gunn, Joshua. (2010). Status Control: An Admonion Concerning the Publicized Privacy of Social Networking. The Communication Review 13(4), 289–308. [ Links ]

Stromer-Galley, Jennifer & Wichowski, Alexis. (2011). Political Discussion Online. In Burnett, Robert, Consalvo, Mia & Ess, Charles (eds.) The Handbook of Internet Studies. Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell, 168–188. [ Links ]

Thurman, Neil & Hermida, Alfred. (2008). A Clash of Cultures: The integration of User-generated Content within Professional Journalistic Frameworks at British Newspaper Websites. Journalism Practice 2(3), 343–356. [ Links ]

Trygg, Sanna. (2012). Is Comment Free? Ethical, Editorial and Political Problems of Moderating Online News. Nordicom-Information 34(1), 3–21. [ Links ]

Usher, Nikki. (2012). Service journalism as community experience Personal technology and personal finance at The New York Times, Journalism Practice 6(1), 107–121. [ Links ]

Van Der Wurff, Richard & Schönbach, Klaus. (2011). Between profession and audience. Journalism studies 12(4), 407–422. [ Links ]

Westlund, Oscar & Ghersetti, Marina. (2013). Modelling news media use Positing and applying the MC/GC- model in comparing everyday and envisioned media use in crisis situations. Article abstract. Available online: http://journalismtransformation.files.wordpress.com/2013/10/oscar-westlund-and-marina-ghersetti.pdf

Vos, Tim, Craft, Stephanie & Ashley, Seth. (2012). New media, old criticism: Bloggers press criticism and the journalistic field. Journalism 13(7), 850–868. [ Links ]

Örnebrink, Henrik. (2008). The Consumer as Producer – Of what? User-generated tabloid content in The Sun (UK) and Aftonbladet (Sweden). Journalism Studies 9(5), 771–785. [ Links ]

Date of submission: May 12, 2014

Date of acceptance: October 1, 2014

NOTES

1 The article is based on a research project which looked into the online presence and credibility of journalists in social media and was conducted in 2012–2013.

2 Instead of clash of cultures, we may use the term clash of discourses because journalists operate in the Web not only as professionals, but also as private individuals, they may belong to the same communities as their audience and thus become netizens themselves.

3 The group of respondents clearly differ from the Finnish mainstream as the Finnish media have succeeded fairly well in retaining their credibility among media users. According to Karppinen, Jääsaari & Kivikuru, 2010, p. 41–46) a few years ago some 95 percent of Finns considered YLE (Finnish Broadcasting Company) news to be reliable and 81 percent were of the opinion that the requirement of veracity was met in Finnish mass-communication either well or fairly well. However, the reliability of social media has been considered fairly poor (Matikainen, 2010).

4 It is interesting to notice that as news-distribution channels Twitter and Facebook are not significant. We propose that these special groups of users get information mainly from their own anonymous online communities to which they are committed to.