Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Indicators

-

Cited by SciELO

Cited by SciELO -

Access statistics

Access statistics

Related links

-

Similars in

SciELO

Similars in

SciELO

Share

Observatorio (OBS*)

On-line version ISSN 1646-5954

OBS* vol.8 no.3 Lisboa Sept. 2014

Spanish and Portuguese journalists on Twitter: best practices, interactions and most frequent behaviors1

Montserrat Doval*

* Profesora de la Facultad de Ciencias Sociales y de la Comunicación, Universidad de Vigo, Campus A Xunqueira s/n 36005 Pontevedra, Spain. (montse.doval@uvigo.es).

ABSTRACT

Mediated communication has created new relationship conditions between media, journalists and audience. In an age where information is ubiquitous, in Twitter becomes more evident the ambiguity between mass, interpersonal, public and private communication; and this social network site is the choice for many journalists to engage with the audience. Through content analysis and monitoring of the activity of 20 journalists, 10 Spaniards and 10 Portuguese, most of them media managers, the research suggests that journalists are still learning how to use Twitter, and next to best practices it has also been found that there are unprofessional uses of the tool. After analyzing their behavior through 1470 tweets, it was found that some journalists leverage the capabilities of the medium; acting as agenda-setters and interacting with the audience while others use it simply as a loudspeaker, without audience or source interaction. What Portuguese journalists, with some exceptions, have in common is a scarcer use of the medium, but at the same time a higher rate of following others than the Spanish journalists do. Some journalists predominantly retweet messages that praise them and interact mostly with their colleagues of their own media which gives an endogamous shade to their behavior online.

Keywords: social network sites, journalism, content analysis, discourse.

1. Introduction

This research was done during a stay in 2012 at the Instituto de Ciências Sociais, Universidade do Minho, Portugal, with the "José Castillejo" research fellowship funded by the Spanish Ministry of Education, through the National Human Resources Mobility Plan I-D + i 2008-2011.

Recent investigations show a tendency to dissolve the line drawn between mass communication and interpersonal communication (Carr and others, 2008) and some authors defend that the characteristics of the new media are cracking the foundations of our conception of mass communication (Chaffee & Metzger, 2001). This is because media conditions have radically changed communication in recent years: we now have media audiences that are increasingly fragmented and the ability to disseminate amplified messages in social media. These two trends have greatly obscured the historical distinction between mass and interpersonal communications, leading some scholars to refer instead to masspersonal communications (Wu, Mason, Hofman, & Watts, 2011) (O'Sullivan, 2003)

Social Network Sites (SNS), ie. means by which information is shared via the Internet, has a role in the emergence of social issues of interest, acting as a new tool of influence for interpersonal groups. Todays media have to live in a new communication ecosystem where the preconditions have changed: from a situation in which the media established its agenda, and their ability to control the message, to a situation in which social media influentials can now set the media agenda and, through it, the public agenda (Meraz, 2011). A new element of change has been the customization of information, the demise of the inadvertent audience" (Bennet & Iyengar, 2008). One consequence of this is the growing gap between informed and uninformed persons. This has reached a point where the exposure to information it is no longer selective but partisan, as Bennett and Iyengar described in the text mentioned above.

Personalization technology prevents users from accessing the same reality, both in their searches online and through social networks. Alejandro Barrios explains how Google personalizes search results: "from 2009, the search engine modified its famous PageRank algorithm, that is, the resulted PageRank becomes sensitive from around 56 variables (browser, IP, operating system, etc.) that identify you, ie. in a form of personalization" (Barrios, 2012), so the search results of the same term are not the same depending on from which device the term is searched.

This content personalization reaches its peak through social networks: Chaffee & Metzger predicted that "Through the daily me concept, the new media will allow people to isolate themselves from the larger public discourse and, in the process, undermine the very notion of a larger public discourse. (Chaffee & Metzger, 2001)

This is a new communication ecosystem in which 1) the boundaries between traditional media and social media have disappeared, 2) in which the "editorial principle" has been replaced by the machine, and that machine is fed (imperfectly) by the election of the user.

In Twitter becomes more evident the ambiguity between mass, interpersonal, public and private communication. Twitter, therefore, represents the full spectrum of communications from personal and private to masspersonal" to traditional mass media (Wu, Mason, Hofman, & Watts, 2011)

1.1 Journalists and Twitter

Journalism is a particularly significant example through which the transition from mass and mediated public communication to interpersonal public communication has occurred. Few academic studies research how journalists use – or do not use – social media as a whole (Lariscy, Avery, Sweetser, & Howes, 2009).

Twitter, the highly popular microblogging network born in 2006, allows messages of 140 characters or less (Marwick & boyd, 2010, pp. 116-117). It has emerged as a real-time source of news for the media, a way to keep in constant touch with the audience, and a brand new way of disseminating information.

"Journalists, who have long cultivated a professional distance from their readers and sources, find themselves integrated into a network in which the distances have collapsed. Physical distances have been erased by a global network that instantaneously delivers information everywhere and anywhere, while social ones have been erased by the inherently open and wholly participatory nature of the network" (Singer, et al., 2011) However, Twitter is about personalityabout adding value to your stories by pulling important information, soliciting feedback and, in general, acting like a human, not like a robot (Lowery, 2009).

In 2008, a research group interviewed 200 journalists from the media as The Wall Street Journal, Financial Times and Business Week. At that time, only three of the 200 journalists said they used Twitter as a source of information. (Lariscy, Avery, Sweetser, & Howes, 2009)

Other studies mention that in autumn 2008, CNN already had 150 journalists using the microblogging network (Messner, Linke, & Eford, 2011).

In a study presented in May 2011, 200 journalists, ??mostly Americans (90 percent) stated that 69 percent of them used Twitter, 49 percent said they managed a business account on that network, and 41 percent had a personal account (Middleberg Communications, 2011). In the same study, the delivering of content to their followers via Twitter or Facebook was 3rd in order of the priorities for journalists. First was delivering the journalistic piece itself and second was to publish it on the website of the medium. The scoop, in the age of social media, has become more important for most journalists, the respondents claim.

In Spain, a recent study based on interviews with 50 professionals (Carrera Álvarez, Sainz de Baranda Andújar, Herrero Curiel, & Limón Serrano, 2012), states that Twitter is the preferred social media by journalists and the most used for finding information, detecting social trends and developing audience loyalty; and to a lesser extent, but also important, to connecting with citizens and institutional sources. Journalists think that the information on Twitter is faster but also more ephemeral. Just over 15 percent of professionals have received instructions or suggestions from their company on how to use social media.

Social media is also used to find news and news sources. In a survey of more than 600 journalists from 16 countries (including Spain and Portugal), 54 percent of them use Twitter and Facebook to receive news or add new perspectives to their information (Oriella PR Network, 2012).

Another area open to scholarly research is the deontological treatment of the journalistic information whose source is Twitter, such as hoaxes or rumors being spread by re-tweeting messages without confirmation. The desire to be the first to communicate a scoop has led ??some journalists to re-tweet false information to their followers without checking its veracity (Millner, 2012). In 2012, journalists from CNN, Huffington Post and Mediate all perpetuated a tweet from a fake profile of the North Carolina Governor they received via Twitter (Silverman, 2012). As Silverman notes, the profile was clearly a travesty, had the previous posts been read, something that that the journalists didn't do. It was not the first time, and probably wont be the last, in which that has happened. The media involved are not guilty of the lack of technological skills, but perhaps of the lack of journalistic standards of verification.

These conditions demand a new kind of relationship between the media and the audience, more specifically, a new management of journalists and media executives, who are forced to answer the summons of an audience that now has means for amplifying their demands.

In Spain the managers of major newspapers are joining Twitter, using the medium in a more or less active way depending on the case.

In the new ecosystem in which public communication and interpersonal boundaries are blurring, it is pertinent to consider what professionals engaged in public communication do with social networking sites. Do they use it as a mass medium? Do they use it for interpersonal conversations? Do they have conversations with the audience or with other journalists?

2. Material and methods

The emergence of computer mediated communication (CMC) is driving a change in research methodology. This research uses content analysis complemented by qualitative methods that achieve a better understanding of the subject matter. Content analysis has been attempted with the perspective and depth claimed by the online context (McMillan, 2000) but quantitative methodologies, apparently well suited to online communication, often reveal as ineffective to capture the complexity of computer-mediated discourse. For example, there are grammatical errors and misspellings in tweets not due to a negligent use of the language but to elements of speech that are expressed through symbols (Herring, 2010, p. 210) (laughs, grunts, emoticons).

The analysis of several scholars of discourse analysis applied to online content suggest the need to combine content analysis with other qualitative methodologies to triangulate research (Martí, Doval, & Román, 2011), in addition, critical discourse analysis highlights the importance of not only what is said but what is omitted (Machin & Mayr, 2012, p. 2)

Regarding the tools used in the research, SocialBro was used for the selection of the analyzed journalists.

For the content analysis I used two tools: the Google Spreadsheet "Twitter Status Updates Archive" created by Martin Hawksey (Hawksey, 2011) and DiscoverText (Discovertext) .

Twenty journalists is an adequate sample as the population of Spanish and –especially- Portuguese communication managers is still scarce.

The population to be analyzed is made ??up of journalists, preferably managers (director, assistant director, editor etc.), of Spanish and Portuguese media, ten from each country. Among those identified as communication managers a further selection had to be made for the Portuguese list, as there is a scarce presence of managers on Twitter among Portuguese journalists, and the few that use the service couldnt be researched as they keep private accounts or dont tweet regularly. The Portuguese list was comprised of journalists without a management position but who were quite influential in the Portuguese society, such as Fernanda Cancio or Paulo Querido. Using SocialBro, it was found that the entire population of Portuguese journalists with at least 100 followers was 106 (February 28, 2012)

On the Spanish list, having more active managers on Twitter, all of the chosen have a management position and were the ones with more followers at the time of research. The whole population of Spanish journalists with at least 100 followers was 974 (February 28, 2012).

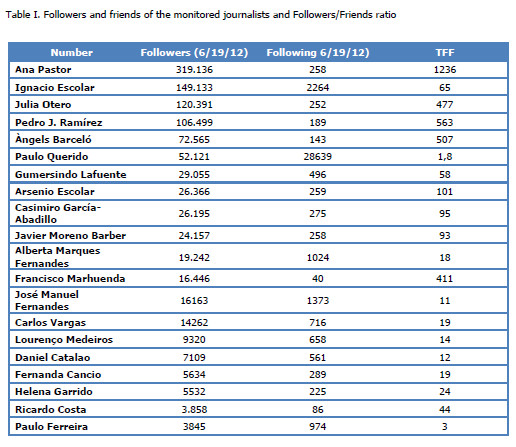

The list of 20 journalists surveyed, and sorted by the number of followers is in Table I2. I also include the TFF index (Twitter Following/Followers Ratio) (Herrera & Requejo, 2012, p. 212) (Elósegui, 2011). The TFF index indicates the possibility of two types of users; the "materialistic" and the "conversationalist" (Leavitt, Burchard, Fisher, & Gilbert, 2009). It suggests that the greater the TFF, the less willingness there is to talk. We will see that this is not accurate, since users with high TFF turned out to be talkers, while users with low TFF did not.

3.0 Results

The monitoring was conducted based on the following categories: 1. Activity and relevance in the social network. 2. Content analysis of activity during a week. 3. Detection of good practices in 25 tweets for each monitored person.

3.1 Activity and relevance in the social network

The first observation is that the use of Twitter among managers of the Portuguese media is much rarer than among Spanish media managers. While the size of the Portuguese population is smaller, Twitter penetration in Portugal is also much lower than in Spain (Observatório da Comunicação, 2012) (Asociación para la Investigación de Medios de Comunicación, 2012).

It seems too that in both countries there is a large gap in Twitter popularity between journalists with television programs and those in newspaper, but this is quite common in other countries as well. For instance, Alan Rusbridger, editor of The Guardian has approximately 78,000 Twitter followers (29 May 2012). However, Eamonn Holmes, host of UK television news programs Sky News Sunrise and ITV This Morning, has approximately 360,000 Twitter followers (11 June 2012). French newspaper editors also are not very popular on Twitter.For example, Erik Izraelewicz director of Le Monde, has less than 2000 followers (29 May 2012) and Anne Sinclair, director of Le Huffington Post, has just over 28,000 (May 29 2012).

Influencing the influencers: A first observation is that the Spanish journalists follow fewer people than their Portuguese colleagues. With the exception of Ignacio Escolar, who follows over 2,000 people, the Spanish journalists do not follow even 500, while in all but 3 cases, Portuguese journalists follow more than 500 people. To this we add the statements made above: Portuguese journalists have fewer followers than Spanish do.

If the journalists are influential themselves, who do they think is influential enough to follow on Twitter? I did what Moretti (2012) suggests: to create a word cloud with the information contained in the Twitter "Biography" (what the user writes to describe his/her personality) of the people who these twenty journalists follow. It is necessary here to consider a methodological problem. People with a Twitter account may or may not indicate certain information in their profile, it may or may not be true, it may be metaphorical or imaginative, refer to their professional or personal life, etc. So the results of collecting from the "biography" of a Twitter profile is not a scientific confirmation of the identity of that individual , but as a collection of several biography profiles, we have some valid content due to the fact that many Twitter users have relevant information in the biography.

The first glance at the contents of the biography cloud suggests a conclusion: there are many users who operate within a closed and narrow social network. For example, if you look at the profiles of those followed by Moreno Barber, editor of El País; the most mentioned word is "país". A closer look confirms that of the 250 people who he follows, a majority work for El País. Julia Otero, Francisco Marhuenda and Angels Barceló follow the same criteria in choosing who they follow.

We can question the reason for this behavior, as it does not seem logical to follow sources of information you already have. One hypothesis is that for these users, Twitter is not a tool for getting information but for delivering information. If this is true, they are not making use of, and perhaps rejecting, one of the most important Twitter functions identified by some studies, that Twitter is a valuable tool for finding journalistic sources (Millner, 2012).

3.2 Content analysis of one weeks activity

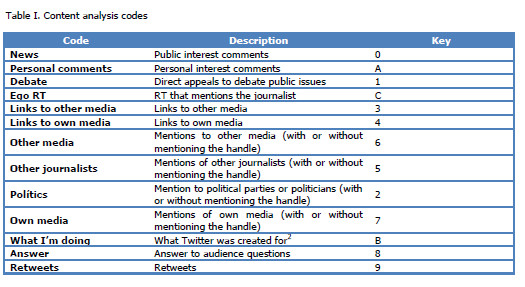

Content analysis was performed on 970 tweets written by the twenty journalists between June 19 and 24, 2012. The tweets were classified with 13 codes reflected in Table II.

The full results in units and percentage are: news 651 (67%), retweets 520 (54%), Ego-retweets 289 (30%), personal comments 213 (22%), links to other media 152 (15%), politics 136 (14%), answers 125 (13%), links to own media 120 (12%), mention to other journalists 83 (9%), debate 53 (5%) and mentions to other media 47 (5%) . Each tweet could be coded with several keys.

The concept Ego RT occurs when A retweets B when Bs message refers to A. Some see this practice as narcissistic or self-serving, while others see it as a way of giving credit to and appreciating the person talking about them (boyd, Golder, & Lotan, 2010).

Each tweet could correspond to several codes. The content analysis allowed investigating how the 20 journalists use Twitter, in order to determine a number of issues:

- If predominates interpersonal communication or mass communication

- If the issues raised are of public or personal interest

- If the tweeters practice active listening

- If they interact with the public or with other journalists

- If they provide information sources from their own medium or other media

- If they promote personal agendas

Fernanda Cancio stands out because of the intensity of use, as she emits almost twice the number of messages than the next highest user, Pedro J. Ramirez, and more than twice than the third, Ignacio Escolar.

As a result of the content analysis, we can make the following conclusions:

Interpersonal or mass communication. In this context, I am referring to whether or not the messages are personalized. How can we detect this with these codes? When there are answers to the messages, we can safely assume that they were customized. If answers are nonexistent or very rare, there is no personalization of the message, and that mass communication predominates. Few users respond to their followers (just over 13% of tweets are replies to another tweet). Fernanda Cancio, establishing a permanent dialogue with her users (36% of her tweets are replies) and Carlos Vargas (34%) stand out. To a much lesser extent and in descending order, so do Pedro J. Ramírez, Julia Otero, Paulo Querido and Ana Pastor.

Journalists who use Twitter for communicating personal content. Those in which A and B codes predominate without linking to any external source. Fernanda Cancio again is the clearest example of this, as almost 58 % of her tweets are personal comments as is Alberta Marques Fernandes, with 75 %. In Cancios case there are many answers with personal content. The journalists, however, do not have similar behavior: Cancio has much more Twitter activity than Fernandes, as her messages are of both personal and public interest. Among the Spanish journalists, those that tweet more personal than public comments are Ana Pastor (10.4 percent), Angels Barceló (8.3 percent) Julia Otero (7.7 percent) and Arsenio Escolar (5.9 percent). The "What Im doing" code highlights Francisco Marhuenda, as his posts are exclusively for the cover of his newspaper, the talk-shows he attends, or tertuits3. The tertuit is a tweet to inform followers when the user attends a talk show (radio or television) and, by extension, when the user reports when he/she is interviewed, when he/she is invited to a show, book signing, etc. Ana Pastor uses 55.8% of her posts to report on what she does and Angels Barceló uses 45.8%.

Active listening. 68 % of Pedro J. Ramírez posts are ego retweets, 53 percent for Ana Pastor, 54 percent for Àngels Barceló, and 33% for Julia Otero. That is, these users are awaiting a mention. In the case of Ramirez this corresponds also to a novel practice that it is altering the print newspaper. In the print version of El Mundo there is a daily selection of tweets mentioning the editor of the newspaper and printed in the Letters to the editor section (El Mundo, 2012). In these cases, we can say that they perform active listening but we will see that there are differences between Ramirez and the rest. Ramirez retweets comments that followers make on what he says, also including negative comments. Pastor, Barceló and Otero, in this sample at least, limited their retweets to those who mention and praise their work. In this case, it was a surprise the aforementioned journalists retweeted so many messages of praise.

Ramirez forwards comments that do not refer to his work but to his previous tweets on matters of public interest, that is, the director of El Mundo generates a discussion on certain topics, selects some tweets and forwards them.

Creating community through debate. Related to the above, one of the codes tries to detect when the journalist attempts to promote debate among his/her followers. The journalists who do this most often are Ricardo Costa (26 percent of his tweets) and Arsenio Escolar (20 percent of his tweets). Pedro J. Ramirez also promotes debate with his audience by asking questions, for example, about how to value a news event. Then he retweets the answers, creating a community of people who debate with him as administrator of messages and therefore as gatekeeper of the information flow. He dedicated 6 percent of his tweets to creating such debates. His ego retweets, in most cases, correspond to the subsequent administration of the answers. These three journalists could be categorized as agenda-setters, acting as discussion catalysts (Graham & Wright, 2013).

Conversation with the public or with colleagues. Of the 57 references to other journalists, many are by Ignacio Escolar, who mentions the author of a piece of information in his newspaper (eldiario.es). He and other journalists mention other colleagues that share talk-shows in radio and television with him/her. In Barcelós case, her mentions only refer to journalists.

Judging by this sample, there is little actual conversation between these journalists and their professional colleagues, and when there is it is only among those in the same medium.

Links to other media. Media, in this case, is a broad concept not just including professional media, but also blogs or self-produced content (photographs taken, personal profile or Facebook page, etc), media of the same publishing group, and media in which the journalists collaborate (radio and television talk shows, for example). Links to other media exceed links to own medium by two units. This result may surprise some but is due to the participation of two very active Portuguese users, Cancio and Querido, that link heavily to other media. Spanish journalists did not link to other media in this sample.

3.3 Detection of best practices in 25 tweets

Best Twitter journalistic practices are the subject of a recent study (Herrera & Requejo, 2012). From that research I gathered some best practices for implementing a content analysis of 500 tweets, comprised of the last 25 of each journalist, collected through DiscoverText on July 11, 2012. I did it this way so that the result was not influenced by the journalists frequency of use.

The best practices concluded in the research are: Having a human voice, retweeting and mentioning users not necessarily related to the media, and linking to external content when it enriches a contribution ( ) listen and talk with the audience, provide useful information, conduct surveys among users or promote its most relevant content in an appealing way. They also make a creative use of hashtags, add multimedia value, or link to other networks where media might have a profile (Herrera & Requejo, 2012, p. 191). I decided not to use the first one as it seemed difficult to assign the category without being subjective. The practice of linking to external content is assumed to be for the purpose of providing proof or documentation about the information provided by the journalists. I added a best practice that was mentioned by Herrera and Requejo in another paragraph: to report events in real-time.

Each tweet could be coded in several categories. The most common best practice among the twenty journalists is talking with the audience (155 tweets of 250) after eliminating those exchanges with professional colleagues. The Portuguese journalists stand out with 104 tweets as having the highest frequency of talking with the audience. 21 of those tweets are from Alberta Marques. Regarding the Spanish journalists (51 tweets of this type) the one that talks most with the audience is Julia Otero, with 22 tweets.

A significant difference between the Spanish and Portuguese journalists is in retweeting: the Portuguese forwarded ??46 tweets while the Spaniards only 3. The Spanish ones who retweeted were Pedro J. Ramirez, Moreno Barber and Gumersindo Lafuente. The Portuguese journalist that retweeted the most was Paulo Querido with 18 retweets.

The frequency of tweeting of real-time reports marks another difference between Portuguese and Spanish journalists, but may be contingent upon the news itself in each country. In the case of the Spaniards, 43 posts were of this type while only 2 among Portuguese journalists. In July 2012, Casimiro García Abadillo sent 22 tweets reporting on a news event in real time the budget cut of 65 billion Euros disclosed by the Spanish Prime Minister Mr. Rajoy. During that time, Portugal did not have a news event of similar importance, so that could have skewed the results.

No Spanish or Portuguese journalist made a follow-up recommendation (Follow Fridays).

Marhuenda stands out for not following any best practice, as his activity on Twitter is limited to linking to the front page of La Razón and mentioning what talk shows he attends (tertuits).

Although Lourenço Medeiros has a 100 percent in recommended tweets, he focuses on just one best: tweeting multimedia content. Others mostly just chat (Otero, Marques, and Cancio Pastor) without making use of other recommended practices.

El Mundo, as a medium and not Pedro J. Ramirez and Garcia Abadillo personally, created the hashtag #bonusparatuiteros to circulate promotion of its paid services free of charge, providing an open link on Twitter. It can be considered a good practice of the medium, and not of the individual professionals. It is not the subject of this research but this is a novel way to interact with an audience of potential customers. Ana Pastor also used a hashtag with the name of the program (# losdesayunosdetve) where she worked at that time.

The word clouds of each user also give clues about their most frequent subjects or the type of communication they send. Julia Oteros most commonly used words are the names of other users, indicating a high level of interactivity. The users she mentions are fellow journalists of her program (Antonio Naranjo) or the audience (the rest). Ana Pastor, who also interacts frequently on Twitter, predominantly talks with other journalists. Àngels Barceló mentions mostly the affairs of her own program or communicates with other journalists and collaborators. Alberta Marques also maintains a talkative practice, but predominantly with her audience. Fernanda Cancio's most used words indicate her high level of interactivity answering questions, since her name is one of the most mentioned.

Therefore, we see that the TFF index is not necessarily indicative of a predisposition to interact. The reason is that users choose interlocutors from among those who mention them, no matter if they follow him/her or not.

Francisco Marhuenda shows in his word cloud two types of tweets: promotion of La Razón frontpage and participation in talk shows, although the talk shows only appear when we open the world cloud to more than five words. In the other journalists cases, the content of their messages is related to the activity of their media.

4. Conclusions and Discussion

Twitter is about personality, as can be seen in this research; the activity of each of the journalists is a reflection of the variety of attitudes toward the same social network, ranging from interpersonal chat with the audience to automated broadcast messages. What Portuguese journalists (except Cancio and Querido) have in common is generally a scarce use of the medium, but at the same time a higher rate of following others than the Spanish journalists do.

Research suggests that journalists - in this case Portuguese and Spanish- are still experimenting with how to use Twitter.

There are some journalists, such as Paulo Querido, that provide a wealth of information to their followers. Others such as Pedro J. Ramírez, Fernanda Cancio, Ana Pastor and Julia Otero interact with the audience, engaging them and creating a community around themselves. Ramirez takes advantage of this with a novel practice that it is also altering the print newspaper El Mundo, with a daily selection of tweets mentioning the editor of the newspaper and printed in the Letters to the editor section.

Three journalists (Costa, Arsenio Escolar and Pedro J. Ramírez) could be categorized as agenda-setters, acting as discussion catalysts.

In some journalists, such as Marhuenda and Moreno, I have not detected any effort to engage with the audience, as they merely post links to their own media. Nor do Gumersindo Lafuente and Casimiro Garcia-Abadillo have an interactive behavior, emitting tweets that are either links to their media or about current events. Among the Portuguese, Helena Garrido also follows this pattern of Twitter behavior.

Some journalists predominantly retweet messages that praise them, (Barceló and Pastor both above 50% of their tweets) as a way of self-promotion, but this very high percentage may be indicative of narcissistic behavior.

The TFF index is not indicative of the willingness to talk, since users with high TFF (eg, Ana Pastor) are more likely to talk than users with lower TFF (Javier Moreno) because users choose interlocutors from among those who mention them, no matter if they follow him/her or not.

Some users seem enclosed in their own profile, as the director of El País. One hypothesis is that for these users Twitter is a tool for delivering information not for receiving information.

None of the 20 journalists did a Follow-Friday recommendation, which may be due to either the sample of tweets, or the lack of interest in recommending the following of others.

Judging by this sample, there is little actual conversation between these journalists and their professional colleagues, and when there is it is only among those in the same medium.

Tertuits, ego-retweets and conversations with colleagues give an endogamous shade to the speech of some Spanish journalists versus the Portuguese. This is exacerbated by the practice of linking only to their own medium contents. In the Spanish case there is only one exception, Julia Otero, who links to information from a newspaper of another media group, El País. It can be concluded that at least some Spanish journalists keep a distance from their audience without really engaging in conversation.

References

Asociación para la Investigación de Medios de Comunicación. (2012, February 23). Navegantes en la Red. Retrieved June 21, 2012, from Asociación para la Investigación de Medios de Comunicación: http://www.aimc.es/-Navegantes-en-la-Red-.html [ Links ]

Barrios, A. (2012, February 19). Sabías que tus búsquedas en la web no son neutras! Retrieved February 21, 2012, from El escritorio de Alejandro Barros: http://www.alejandrobarros.com/sabias-que-tus-busquedas-en-la-web-no-son-neutras [ Links ]

Bennet, L., & Iyengar, S. (2008, December). A New Era of Minimal Effects? The Changing Foundations of Political Communication. Journal of Communication, 58(4), 707–731. [ Links ]

boyd, d., Golder, S., & Lotan, G. (2010). Tweet, Tweet, Retweet: Conversational Aspects of Retweeting on Twitter. HICSS-43. IEEE. Kauai, HI. [ Links ]

Carrera Álvarez, P., Sainz de Baranda Andújar, C., Herrero Curiel, E., & Limón Serrano, N. (2012, June). Periodismo y Social Media: cómo están usando Twitter los periodistas españoles. Estudios sobre el Mensaje Periodístico,, 31-53. [ Links ]

Chaffee, S. H., & Metzger, M. J. (2001). The End of Mass Communication? Mass Communication & Society, 365–379. [ Links ]

Discovertext. (n.d.). Discovertext. Retrieved from Discovertext: http://discovertext.com/

El Mundo. (2012, June 20). Tuits al director. El Mundo, p. 20. [ Links ]

Elósegui, T. (2011, January 23). Los medios usan Twitter como un altavoz. Retrieved September 6, 2012, from Tristán Elósegui. Blog de marketing online: http://www.tristanelosegui.com/2011/01/23/los-medios-de-comunicacion-usan-twitter-como-un-altavoz/ [ Links ]

Graham, T., & Wright, S. (2013). Discursive Equality and Everyday Talk Online: The Impact of Superparticipants. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, 1-18. [ Links ]

Hawksey, M. (2011, May 3). Google Spreadsheets and floating point errors. Retrieved May 12, 2012 from Jisc CETIS MASHe: http://mashe.hawksey.info/2011/05/export-twitter-status-updates/ [ Links ]

Herrera, S., & Requejo, J. L. (2012). 10 Good Practices for News Organizations Using Twitter. Journal of Applied Journalism and Media Studies, 79-95. [ Links ]

Herring, S. (2010). Computer-Mediated Discourse. In D. T. Deborah Schiffrin, The handbook of Discourse Analysis (pp. 612-634). Malden (MA) EEUU: Blackwell Publishing.

Lariscy, R. W., Avery, E. J., Sweetser, K. D., & Howes, P. (2009). An examination of the role of online social media in journalists source mix. Public Relations Review(35), 314–316. [ Links ]

Leavitt, A., Burchard, E., Fisher, D., & Gilbert, S. (2009). The Influentials: New approaches for analyzing influence on Twitter. Boston, MA: Web Ecology Project.

Lowery, C. (Fall 2009). An Explosion Prompts Rethinking of Twitter and Facebook. Retrieved March 7, 2012, from Nieman Reports: http://www.nieman.harvard.edu/reportsitem.aspx?id=101894 [ Links ]

Machin, D., & Mayr, A. (2012). How to do critical discourse analysis. Londres: SAGE Publications. [ Links ]

Martí, D., Doval, M., & Román, M. (2011). Ajuste tecnológico y social del análisis del discurso digital. "Investigar la Comunicación en España: Proyectos, Metodologías y Difusión de resultados", (págs. 117-132). Madrid. [ Links ]

Marwick, A. E., & boyd, d. (2010). I tweet honestly, I tweet passionately: Twitter users, context collapse, and the imagined audience. New media & society, 13(I), 114-133. [ Links ]

McMillan, S. J. (2000). The microscope and the moving target: the challenge of applying content analysis to the World Wide Web. Journalism and Mass Communication Quarterly, 80-98. [ Links ]

Meraz, S. (2011, January). The fight for how to think: Traditional media, social networks, and issue interpretation. Journalism, 12(1), 107-127. [ Links ]

Messner, M., Linke, M., & Eford, A. (2011). Shoveling tweets: An analysis of the microblogging engagement of traditional news organizations. International Symposium on Online Journalism (p. 25). Austin TX: Knight Chair in Journalism. University of Texas at Austin. [ Links ]

Middleberg Communications. (2011, May 6). Insights from the 3rd Annual Middleberg/SNCR Survey of Media in the Wired World. Retrieved May 2, 2012, from Middleberg Communications: http://middlebergcommunications.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/05/Middleberg-SNCR-Survey_2011-05-06_slides.pdf [ Links ]

Millner, L. (2012). A Little Bird Told Me. Journal of Mass Media Ethics: Exploring Questions of Media Morality, 60-62. [ Links ]

Moretti, L. T. (2012, marzo 1). How to map an influencers network. Retrieved March 6, 2012, from Ident{een}ity: http://www.identeenity.com/2012/03/01/how-to-map-an-influencers-network/ [ Links ]

Observatório da Comunicação. (2012, May). Sociedade em Rede. A Internet em Portugal 2012. Retrieved June 21, 2012, from Observatório da Comunicação: http://www.obercom.pt/content/782.np3#1 [ Links ]

Oriella PR Network. (2012, June 20). The influence game: how news is sourced and managed today. Retrieved June 25, 2012, from Oriella PR Network: http://www.oriellaprnetwork.com/sites/default/files/research/Oriella%20Digital%20Journalism%20Study%202012%20Final%20US.pdf [ Links ]

O'Sullivan, P. B. (2003). Masspersonal Communication: An Integrative Model Bridging the Mass-Interpersonal Divide. [ Links ] International Communication Associations annual conference. San Diego.

Silverman, C. (2012, May 15). HuffPost, CNN, Mediaite fall for fake Twitter account of NC governor. Retrieved May 15, 2012, de Poynter: http://www.poynter.org/latest-news/regret-the-error/173923/huffpost-cnn-mediaite-fall-for-fake-twitter-account-of-nc-governor/ [ Links ]

Singer, J. B., Hermida, A., Domingo, D., Heinonen, A., Paulussen, S., Quandt, T., . . . Vujnovic, M. (2011). Participatory Journalism: Guarding Open Gates at Online Newspapers. Malden, MA: Wiley-Blackwell.

Wu, S., Mason, W. A., Hofman, J. M., & Watts, D. J. (2011). Who Says What to Whom on Twitter. Retrieved May 25, 2011, from Yahoo Research: http://research.yahoo.com/pub/3386 [ Links ]

NOTAS

1 Translation of the current article was supervised by Carolyn Sheehan Crosby

2 "What are you doing?" was the question Twitter asked users for status updates from 2006 to 2009, when was changed for "What is happening?"

3 The term is a creation of media consultant Antoni Maria Piqué (@ ampique). It is a contraction of "tertulia": talk-show in Spanish and "tuiteo", Spanish for tweet.