Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Acessos

Acessos

Links relacionados

-

Similares em

SciELO

Similares em

SciELO

Compartilhar

Observatorio (OBS*)

versão On-line ISSN 1646-5954

OBS* vol.8 no.2 Lisboa jun. 2014

Discourses of Heterosexuality in Women's Magazines' ads: Visual Realizations and their Ideological Underpinnings

Zara Pinto Coelho*; Silvana Mota-Ribeiro**

* Associate Professor in the Department of Communication Sciences, Minho University, Campus de Gualtar, 4710 Braga, Portugal. Researcher at the Communication and Society Research Centre. (zara@ics.uminho.pt)

** Assistant Professor in the Department of Communication Sciences, Minho University, Campus de Gualtar, 4710 Braga, Portugal. Researcher at the Communication and Society Research Centre. (silvanar@ics.uminho.pt)

ABSTRACT

This article aims to identify the discourses articulated in images of heterosexual ads published in women's magazines and their ideological underpinnings. It explores how heterosexuality is represented at a visual level, and examines the notions of femininity and masculinity, gender and sexuality that are constructed by the ads and the way they are intertwined. The main structures of the images are analysed within the framework of social semiotics, and from a critical feminist point of view. The analysis of hetero ads reveals the presence of heteronormative gender discourses and conventional representations of the hetero couple, as well as the presence of more 'permissive' discourses and representations concerning female sexuality. However, although some ads might slightly 'flirt' with female sexual transgression, this is done in a way that does not threat dominant conceptions of feminine heterosexuality. In conclusion, hetero ads still reinforce conventional heteronormative expectations regarding the relationship between sexuality and gender.

Keywords: feminine heterosexuality discourses; gender discourses; visual social semiotics; advertising images; women's magazines; interweaving of gender and (hetero)sexuality

Introduction

Previous research has shown that in 'Western' cultures women's ads participate in the on-going construction of forms of knowing and evaluating gender relations and subjectivities in accordance with heterosexual desire (Puustinen, 2000; Rossi, 2000a, 2000b, 2005). This continuing re-production of a linkage between gender and heterosexuality in which print ads play an active role establishes a causal relationship between sex, gender and desire (Butler, 1990). This needs to be broken, or at least exposed, if one wants to make strange and challenge the dominant gender ideology of our cultural tradition, and the hetero-gender hegemony that is sustained by it. In attempting to do so, we have been engaging in a long-term research project focusing on women's ads published in women's magazines to reveal how femininity and masculinity are constructed relationally through heteronormative gender discourses. One of our aims has been to study the role of specific visual choices in the expression of heterosexual discourses, since we think there is still a lot to do on this field. On the one hand, there is psychological research, mainly based on interviews, which gives us access to the specific contents of this kind of discourses (e.g. Hollway, 1989), but which is not visually oriented. The same happens with linguistic oriented analysis, with its focus on language use (e.g. Crawford, 1995; Weatherall, 2002). On the other hand, there are empirical media studies that do not show in detail the visual workings of women ads, due to the still dominant preference for content analysis. In a previous article (Pinto-Coelho & Mota-Ribeiro, 2006), we used visual social semiotics of Gunther Kress and Theo van Leeuwen (1996) for a detailed systematic visual analysis of women ads, and in the present study we keep working within this approach. It allows us to question the naturalness and rigidity of women's ads' meanings and offers the resources to go beyond the level of vague suspicion and intuitive response, common in content analysis. It may also contribute to pave the way to new uses of visual resources in the domain of women's ads.

At the same time, however, in the study of the use of visual resources, visual social semiotics by itself is not enough, as it is essentially a descriptive framework (Jewitt & Oyama, 2001). In order to generate ideas for the research question and hypothesis, and for the interpretation of images, the study had to draw on other sources: gender, sexuality and power debates (Butler, 1990, 1993; Connell & Dowsett, 1999; Connell, 2002; Rich, 1980; Rubin, [1984] 1999), research on gender and discourse (Lazar, 2005; Wodak, 1997) and on sexuality and discourse (Bryant, 2004; Cameron & Kulick, 2003; Harrison, 2006; Hollway, 1984; Mooney-Somers, 2005), as well as on studies of gender and sexuality construction in women's ads (Cortese, 1999; Gill, 2008; Goffman, 1979; Lazar, 2006; Messaris, 1997; Mistry, 2000; O'Barr, 2006; Rossi, 2000b; Williamson, 1978; Winship, 1980, 1987, 2000). It is against this background that we want to identify the discourses realised in women's ads and spell out their contents, as well as to show how they are articulated within ads, based on visual cues. Another aim is to examine the representations of heterosexuality that are produced, and also to know what these constructions tell us about the (changing or unchanging) contemporary balance of power between women and men in the domain of heterosexual ads published in women's magazines. Our hypothesis is that these representations play a role in the construction of a form of feminine and masculine heterosexuality that positions women and men asymmetrically. We thus consider that women ads are relevant to the construction of both heterosexuality and gender, with male dominance as a key-component in both cases. We also claim that heterosexuality has a crucial function in the maintenance of gender hierarchy that subordinates women and men.

1. Discourses and the Interweaving of Heterosexuality and Gender Constructions

Discourse is hereby understood in Foucauldian terms to mean a set of related statements that 'systematically form the objects of which they speak' (Foucault, 1972: 149) and which, within that object, or area of social life, make specific subject positions available. Discourses are never neutral or objective, in the sense that putting into discourse is a selective procedure and that discourses are inherently positioned, that is, they carry the meanings about the nature of the institution, or the social grouping from which they derive (Kress, 1989). Differently positioned social formations 'see' and represent social life in different ways, as different discourses (Fairclough, 2001).

As historically variable modes of talking (Kress, 1989), discourses enable and constrain possible ways of knowing the world, the sense of who we may be (and not be) within that world order, and how we may (and may not) relate to one another. They tell us what is normal and natural whilst establishing the boundaries of what is acceptable and appropriate. Since knowing is engaging in social relations, the power to control ways of knowing is a power over what is accepted as reality, and over those amongst whom that acceptance circulates. Discourses are thus seen as productive and as having power outcomes or effects. They define and establish what is 'true' about a given social area at particular moments, and thus define what is accepted as reality in a given social grouping. In the domain of heterosexuality, there is nothing inherently fixed or essential about the identities of a hetero-female or a hetero-male, or in the way heterosexual relations between them have tended to be structured - as opposite and complementary. Heterosexuality and heterosexual behaviour are not expressions of a 'fixed essence' (Padgug, 1999), of natural or biological impulses, or of a natural attraction between pre-existing opposites - men and women. Rather, those are always and everywhere constrained (and, at the same time, potentiated) by the rules, the prohibitions and permissions, the categories and definitions that circulate in discourse. For example, a male/female dichotomy allows only heterosexuality as normative.

Since discourse about heterosexuality, or more generally about sex, sexuality and gender is not static and homogenous, 'the rules through which we organise our understanding of sex and gender are not always and everywhere identical' (Cameron & Kulick, 2003: 43). As far as gender is concerned, the historian Joan Wallach Scott (1999) points to these contradictions in culturally available symbols in the Western Christian tradition that evoke multiple (and often contradictory) representations - Eve and Mary as symbols of Woman, for example, but also myths of light and dark, purification and pollution, innocence and corruption (Tseelon, 1995; Ussher, 1997; Weitz, 1998). This diversity is one of the reasons why power effects of discourses should be analysable in the context of orders of discourse (Fairclough, 1992) and of a larger system of sometimes opposing, contradictory, competing, contesting or merely different discourses (Kress, 1989). In this vein, Hollway (1984) sees heterosexuality as constructed by the way in which 'at a specific moment several coexisting and potentially contradictory discourses concerning sexuality make available different positions and different powers for men and women' (1984: 230). However, not all discourses have the same power. Discourses are always subject to contestation, and it is in the best interest of dominant social groupings to repress or deny this contestation, as it is in the best interest of the subordinated groups to engage in it as strongly as possible. Within the scope of heterosexuality, as well as in the domain of gender, discourses are a terrain of struggle. They testify to the on-going power struggles over who may define and categorise sex and gender, and from which point of view.

Discourses are fluid. They do not have an objective beginning and a clearly defined end (Wodak, 1997: 6). They are fluid and opportunistic, and concurrently draw upon existing discourses about an issue whilst utilising, interacting with, and being mediated by other discourses. This leads to the question of gender and sexuality, and how they may be discursively intertwined. Although we agree with Rubin's claim (Rubin, [1984] 1999) that sex and gender are not the same thing, and that analytically sexuality and gender should be distinguished, we also think, with many other feminist theorists, and with Rubin as well, as she had claimed this same position in her early 1975 essay (Rubin, 1975), that they are separated systems which are interwoven at many points. They have a particular kind of mutual dependence, which no study of either can overlook (Bucholtz & Hall, 2004; Cameron & Kulick, 2003). It is by now a familiar finding - reported by several researchers working in Anglo-American cultures - that the discursive construction of heterosexuality is often bound up with the discursive construction of femininity and of masculinity (Hollway, 1984; Rich, 1980; Sunderland, 2004). In this discursive chaining between gender and heterosexuality, heterosexual identities are represented as natural, the product of the anatomically sexed body (whether female or male), while gender identities are seen as signifying the meanings attributed to the sexed body (whether feminine or masculine). This distinction between sex and gender entails the understanding that male bodies are the basis of masculinity and female bodies the basis of femininity and the construction of an established binary heterosexual order upon which normative gender is built. The coherence of the articulation between 'gender differences discourse' (Hollway, 1984) and the dominant heterosexuality discourse, where the binary structure of gender finds its complement in opposite-sex attraction, is insured by the dominant ideology of gender. According to this ideology,'real men axiomatically desire women, and true women want men to desire them. Hence, if you are not heterosexual you cannot be a real man or a true woman; and if you are not a real man or woman then you cannot be heterosexual' (Cameron & Kulick, 2003: 6).

2. Women's Magazines Ads, Configuration of Discourses and their Ideological Workings

Our focus of attention is on semiotic resources, specifically on the ways visual and written resources are used in women's magazines ads, and on their interrelationships, i.e. on the multimodality of the ads. The use of semiotic resources as we see it is a social activity, and therefore we understand the production and reception of visual ads as being regulated by the conventions and norms of the genre of advertising.

As a genre of communication, advertisements are identified by their typical forms of text which link specific social participants, topic, purpose, medium, manner and occasion (Hodge & Kress, 1988). The final purpose of advertisers is, as we know, to persuade people to buy products, although there is a minority of ads that do not refer to a product (e.g. prevention ads in the field of public health). The strategy used to advocate a change of behaviour is to build an 'image' for the product being advertised, by associating the product with cultural properties (e.g. values, ideals, lifestyles, myths), that then become a part of it, its mark of distinction, the image that distinguishes the company and its consumers (Cornu, 1990). In order to be effective, however, this strategy needs the active participation of the viewer (Leiss, Kline & Jhally, 1990) that should be able to transfer the meanings of a visual image with a young beautiful couple to the clothes with which is associated. The process of recognition and memory is simplified because visual ads, due to its persuasive nature, aim to engage the viewers directly, by constructing a position for them. As we are aware, in mediated communication the immediate and actual reciprocity of face-to-face communication does not exist. There is from the start a lack of reciprocity and other things (for example, the complex and the indeterminate nature of the producer) that make the producer and the viewer unequal, a lack which realises power (Fairclough, 1989). In images, the power of the maker of the image must, as it were, be transferred onto one or more represented participants. Visually, it is through identification with the role models that magazine readers are invited to accept the image given to the product, and are asked to become a part of that community, to be one of them (Kress & van Leeuwen, 1996).

This work of interpellation may also function through textual features which are widespread in the advertising genre (direct address of viewers with a 'you', and imperative sentences) (Myers, 1994), as well as through specific articulations between visual resources and written ones. In common sense, this construction of a specific relationship between producer and viewer and of a viewing position for the viewer, goes generally unnoticed, as the focus of attention is usually on what the image is about, i.e. on the world represented by the image. But in the framework of visual social semiotics the representation of the social relations of viewer-image, what the images want from the viewer, what they offer to them, the position constructed for the viewer, using as vehicles for these effects a number of selected visual resources, have a fundamental status. They are considered to be the expression of the social place of producers, of their discursive histories, of the meanings and forms of the genre, and as such they affect both what the image is about and its reading and uses.

Obviously, during actual interaction the viewers may refuse the position constructed for them in the visual text; a distance of some kind makes such viewings possible. This may be due to differences between their social position, discursive history and knowledge of the genre, and those of the producer; but ads construct this position whether the viewer steps into it or not (Kress, 1989). So, as a social activity, the production and the reception of ads is constrained or influenced by the meaning and the formal features of the genre, and also by the type of discourses that are drawn to construct an image for the product and a viewing position for the reader. Likewise, the viewing subject is limited in her or his work of image reconstruction by the viewing position is set for her or him in the text, which gives her or him instructions about how to read the ad, and by the position that she or he is invited to occupy in the discourse or discourses articulated in the ad. The path of least resistance is to access discourses compatible with how one is being subject positioned.

In spite of all these constraints, of all these features that make the construction of meanings possible, ads as social activity or genre have a constitutive nature. In other words, they contribute to produce the world that is shown in the image, by constructing a representation of it and by constructing a reading position for the viewer. This, in a long run, if accepted, is turned into a 'subject position', that is, 'a prescription of a range of actions, modes of thinking and being, compatible with the demands of a discourse' (Kress, 1989: 36). This means that what limits the act of production and reception is also what makes possible the constitutive effects of ads and their active viewing. Social agents are active and creative. The space of interaction, the concrete situation of social exchange, enables the re-construction work of the rules of the genre, and of the discourses used in the production and in the reception of the ads. Therefore, it is crucial to focus on the use of semiotic resources in specific instances of visual texts. They are the sites where change may happen. Each time a team of ad designers use a discourse, or a set of discourses, to build an image for the product, they re-construct it in a new way through the use of a new composition, which structured the meanings of the ad. And, as it is well known, the ever-changing demands and contradictions of social situations require the agent to be creative in her or his use of semiotic resources and discourses articulated by them. As Kress argues, every text arises out of a dissension situation, and shows the features of differing discourses, competing and struggling for dominance. They thus should be seen as 'sites of attempts to resolve particular problems' (Kress, 1985: 74).

If visual ads are to be seen as such, it may be asked how the process of reproduction of genres and discourses happens, either in a conservative sense, sustaining continuity, or in a transformational one, effecting changes. Within the visual social semiotics approach, the answer lies on the works of ideology through texts. When people draw upon genres and discourses that they perceive as universal and common sense, because it is simply the way of conducting oneself, they place them outside ideology, that is, out of social struggle. This appearance of neutrality is the result of the naturalization of a discourse, which means that it has succeeded in the fight for the colonisation of a particular social area by 'making that which is social seem natural and that which is problematic seem obvious' (Kress, 1989: 10). In the domain of sexuality, this is visible in the naturalness of the two-sex idea, and in the notion that the two must be inherently contrasting. This contrast is read in most cultures, according to Cameron and Kulick (2003), as complementary (i.e., matching what the 'opposite sex' is not), and is rendered desirable, awarding heterosexuality with validity and authority as the only natural and normal sexuality. Although what we 'know' to be heterosexuality at any given time is historically, culturally and socially specific and subject to redefinition and transformation, it is heterosexuality that persists as the benchmark of 'good' 'normal', 'natural', 'healthy' and 'holy' sexuality (Rubin, [1984] 1999). Therefore, ideas about heterosexuality become naturalised in commonplace thinking with the effect that heterosexual relationships are taken for granted as the norm.

This naturalisation, that makes domination appear as not being domination at all, and makes us think in terms of ideological hegemony (van Dijk, 1998) because it presupposes a winning of consent, is always a matter of degree, and the extent to which the meanings of a discourse and its associated subject positions are fixed may change, in accordance with social change. Even if power relations remain relatively stable, they need to renew themselves in a constantly changing world, and the creative combination of discourses may thus be necessary for a dominant social group to keep its position (Fairclough, 1992). Advertisements are a good example of this strategic use, since they draw upon existing discourses about an issue whilst utilising, interacting with, and being mediated by other discursive elements (about, e.g., family, morality, health, religion) to produce new ways of conceptualising a given social area. This is another sense in which visual ads are productive.

If visual ads are constituted in and by this plethora of discourses, how do these different and sometimes contradictory representations of social life cohere - that is, how do they come together - to build up an image to the product and a viewing position for the viewer? According to Kress (1989), while discourses articulate the meanings of particular institutions, ideologies lead to a specific configuration of discourses in specific texts in response to the demands of larger social structures. The alignment of discourses in particular ways provides a coherent surface for the visual ad, which offers a single overall viewing position to its viewers. The working of ideology is thus a conservative one, as it is a means to contain differences within the configurations of discourse already known, so that what usually happens in visual ads comes to be the common sense. At the same time, however, the continuous change of practices creates a tension between social reality and practices and the way these are represented in visual ads. Encouraging 'readings against the grain' that offer alternative subject and viewing positions has the effect of making these differences visible and open to debate - an openness we believe to be fundamental for the promotion of social change, when it also implies extra-discursive or material changes.

3. Ads' Visual Features and Discourse Spotting

Discourses appear and are realized in many other modes besides language (Kress & van Leeuwen, 2001). For linguistic texts, it is 'a certain range of linguistic features that make up the text which are determined, selected, by the characteristics of the discourse' (Kress, 1985: 28). In terms of visual texts we need to look instead at a range of visual entities. A given discourse is only recognisable by analysts through its manifestation in typical visual traces in texts, because discourses are not themselves visible. When these texts combine visual and written semiotic resources, the analyst must pay attention to the manner in which they are brought together, and the contributions of each of them to the articulation of discourses, and to the viewer's making of meaning.

As we put it, visual features express or point to discourses but, at the same time, their local manifestations in visual texts transform or reconstruct those discourses (Fairclough, 1989). As far as analysis is concerned, discourses are identified in terms of a set of representations that express a particular viewpoint. The aim of the analysis is to make these various representations evident, singly or in articulation with others, which shows the operation of a particular discourse, or a combination of discourses in the visual text. At the same time, we identify the versions of heterosexuality and gender that are constructed in visual ads and how they imbricate with relations of power between women and men. Due to the persuasive nature of ads, and to the degree of naturalness of the dominant discourses of heterosexuality and gender, discourses and ideologies that give them coherence can be expected to be brought to discourse not as explicit elements of visual text, but as background assumptions imposed upon it, which, on the one hand, 'lead the text producer to textualize the world in a particular way and, on the other hand, lead the interpreter to interpret the text in a particular way' (Fairclough, 1989: 85). Therefore, the activity of "discourse spotting" (Sunderland, 2004: 32) is one of making explicit the content of discourses backgrounded in visual texts. This requires a sense of the range of discourses used within the domain of women's magazines ads and that are a part of the cultural common ground of Western societies, as a horizon against which to assess discourses in which a particular visual text draws upon.

The identification of both discourses and the versions of heterosexuality and gender in visual texts is done through a systematic analysis of visual structures (and sometimes textual, their combination) and of processes that cue these discourses and representations. This involved a 'back and forth' between visual texts and the content of discourses which we accessed through the reading of specific feminist literature on the subject, especially Hollway (1984). Hollway's framework, though in many ways psychological, connects gender and sexuality in particularly useful ways, since she focuses on gender differences in discourses concerning sexuality and its implication for the construction of subjectivities of men and women and gender-differentiated positions. The three discourses identified in her study - 'male sexual drive discourse', 'have/hold discourse' and 'permissive discourse' - are often still considered nowadays the dominant discourses on heterosexuality in Western societies (Gavey, McPhillips & Braun, 1999; Mooney-Somers, 2005).

The reading of the feminist literature also helped us in the activity of naming the discourses identified in ads. Using the metaphor of Sunderland, the activity of identifying discourses in visual ads is a 'birding activity' (Sunderland, 2004: 3), and is always interpretive. Just like the viewer, the analyst draws on her or his representations of personal and social memory to give coherence to visual texts (van Dijk, 1998), that is, to bring the implicit assumptions into the process of interpretation. However, unlike the viewer, she or he does this in a conscious way (Fairclough, 1989). It is also important to stress that, due to the specific features of the ads under analysis, we consider that the visual features that cue femininity visually also cue heterosexual identity. That is, we see the women's ads in our study as a means to construct both gender identities and sexual ones. But one should not assume that this is always the case (Cameron & Kulick, 2003).

The analysis of the visual structures in ads is inspired by the grammar of visual design developed by Kress and Van Leeuwen (1996). These authors, following Halliday's function theory, argue that the grammar of visual design is analysable in different ways, according to a triple meaning-making process:

- Representational meaning - the ways in which heterosexuality can be visually encoded - that is patterns of representation, which can be narrative (including transactional or non-transactional action and reaction processes of participants, realized by vectors of various sorts, and also circumstances) or conceptual (including classificational or analytical types of structures). Based on this, we show what kind of version of heterosexuality is established (narrative or conceptual), and make explicit the discursive elements about (hetero)sexuality that were implied or suggested by these constructions and its discursive chaining with other types of discourses.

- Interactive meaning - patterns of interaction, the things that can be done by viewers and makers of images to each other and the relationship between them that it entails; this includes, among others, gaze of the participants, the size of frame (close, medium or long shot), point of view (the angle from which the participant is 'seen' by the assumed viewer) and also modality aspects - coding orientation and modality markers, such as issues of colour, contextualization, abstraction/pictorial detail, depth, illumination and brightness. Based on this level of the meaning-making process, we show how the versions of heterosexuality constructed by the images implicate women and men in different ways, that is, how it contributes to maintain gender-differentiated positioning in heterosexual relations.

- Compositional meaning - the ways in which patterns of representation and patterns of interaction relate to each other and cohere into a meaningful whole; this may include information value (realized by placement of participants and syntagms in the representation space) and salience (realized for instance by contrast, size, sharpness) (Kress & van Leeuwen, 1996).

4. A Visual Social Semiotics Analysis: Corpus and Visual Features

Based on an extensive corpus of print advertisements, which belongs to a larger project on a visual social semiotics analysis of gender in women's magazine ads, we have selected a set of 15 advertisements for this research. The global corpus consisted of 152 images, collected from all monthly women's magazines, published in Portugal, in September 2006 (Elle, Máxima, Vogue, Activa, Cosmopolitan, Lux Woman, Ragazza). Monthly magazines were chosen, since weekly magazines are quite poor in terms of advertising images and they are more likely to be labelled as "gossip" or "TV" magazines rather than women's magazines, following Buitoni's discussion (1986). Also, monthly women's magazines published in Portugal include both Portuguese titles (e.g. Máxima) and national versions of global brands (e.g. Elle) (Machin & Thornborrow, 2003).

Image selection was based on the fact that they depict at least one woman and one man, whose way of being together has common sense heterosexual connotations, that is, romantic or sexual meanings1. As in these magazines women appear mostly alone (Mota-Ribeiro, 2005, 2011) and the selection was based on heterosexual connotations (the object of this research in particular), only 15 images followed the criteria out of the wider corpus of 152. These images were singled out since our interest was to analyse heterosexuality and not the way in which women or man alone are portrayed in advertisements.

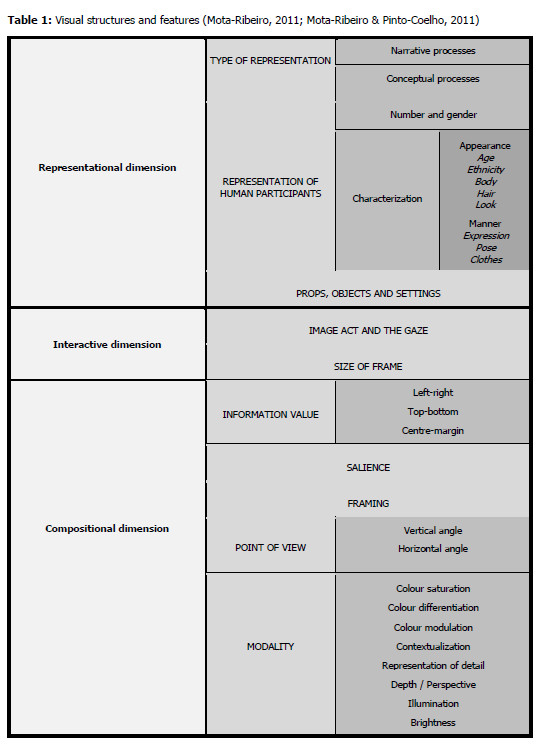

The analysis of the visual structures in the selected ads is inspired by the grammar of visual design developed by Kress and van Leeuwen (1996) and was conducted using the visual features shown bellow2 (Table 1).

All 15 images were analysed in detail, according to these features. However, we in order to illustrate and account for the representations of heterosexuality, only 5 are shown and discussed more thoroughly.

5. Representations of Heterosexuality: Visual Features and Discourse Spotting

Analysis is structured along the lines of two main representations of heterosexuality constructed by or through the images: coupledom heterosexuality and female centred heterosexuality. The significance of heterosexual coupledom as a form of socio-sexual relationality has remained relatively unchallenged (Cover, 2006; Finn, 2005). According to Catherine Belsey (1994), coupledom operates as the 'conventional tale of desire framed by true love, contained by marriage, and generating the nuclear family, which is understood to be the primary source of domestic comfort and emotional support for all normal members of a civilized society'. (pp. 193-194).

Coupledom heterosexuality has traditionally been grounded in the presumed 'naturalness' of heterosexual complementarity, which implies the male/female dyad supposed to give the excitement to heterosexual sex, and the active/passive dyad. These dualistic categories are the basis for the representation of the couple as the ideal, natural, or authentic form of heterosexual relation, standing in opposition to casual sex, the one-night-stand, sex-without-emotion or non-committed sex, and so, for its essentialisation as a naturally occurring entity. In this acceptable, natural way of coupling, of everyday sexual and relational sociality, sex is ultimately reproductive and therefore useful.

Female centred heterosexuality is the representation that organizes the set of images which are not bounded by the couple regime, the safe 'one-to-one haven' (Finn, 2005); they construct a way of doing coupledom that implies a more autonomous female sexuality (Hollway, 1989), or which offer women a way to express their sexuality out of a committed relationship with a man, valuing thus free sexual expression over a 'monogamously bonded pairing' (Finn, 2005: 63). The presence of this kind of images show that women's magazines ads are not a homogenous visual world (Rossi, 2005), even if this visual difference does not stand at close analysis or keeps on elaborating under traditional meanings, as we claim here.

5.1. Hetero Coupledom

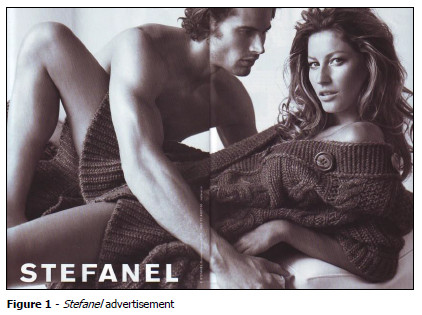

Discourses about heterorelationships in couple arrangements frequently draw upon narratives of romance and passion in which sexual relations between women and men are based on meanings of 'natural complementary opposites' and are framed by the dominant script where an active, masterful and skilful man will receive access to sex when he enacts the appropriate practices with/for a woman. figure 1 is an example of how this narrative can be expressed in women's ads.

- Heterosexuality as passion and desire

The image in figure 1 constructs a version of heterosexual couple relationships that includes sexual and erotic actions and as based on a sort of natural, reified essence, constructed differently for women and men. Discourse of proper femininity and masculinity is visually realized by bodily characteristics shown as opposite (the man consists of [/ the woman consists of] - a conceptual analytical process) and are combined with poses and actions to make up the idea of sexual dichotomy/complementarity and to construct the proper heterosexual symbol: the couple.

In terms of narrative processes, women and men's sexualities are also constructed as opposites, an opposition that evokes the coexisting 'have/hold' and 'male sex drive' discourses (Hollway, 1984): he is 'naturally' predatory, she is 'naturally' receptive and passive; he always wants sex, she is 'naturally' not interested in sex. The man is presented as the actively sexual half, while she is shown as bodily more passive. Also, he is unable to resist her (the man's pose and expression realize this). On the other hand (and this is somehow a contradictory aspect of the heterosexual discourse), the woman is not supposed to actively pursue the man and should even resist his 'male drive' actions - something that happens, tough subtlety, in this image, since he restrains her body (she cannot resist), and she is not active in the action of seducing him (she is looking at the viewer). Modality markers and interactive meanings (especially as far as the image act is concerned) show this woman somewhat withdrawn bodily and psychologically from the actual erotic encounter, but shows also that is she is perfectly aware of her ability to attract him and her condition of bodily/visual being, which she wants the viewer to acknowledge. As part of her 'typical' and 'natural' feminine attributes, which say that women use beauty, clothing and appropriate sexuality to trap men into romantic relationships, she should be able to attract the man based on corporeal features of beauty and youth. And this is the position the female model invites the viewer to identify with, through her direct and malicious look, to desire to be desired by men. The 'woman as appearance' feature of a dominant discourse about femininity is therefore quite present here, attached to meanings about the sexually manipulative and dangerous woman, found in the 'predatory female discourse' and on myths of women who use their body to attract and deceive men (Tseelon, 1995; Ussher, 1997).

In the ad, these meanings are double-edged in terms of women's power. While the female model is shown as someone who can deny access to her body and transform that into a game - gaining some power -, she is still doing it in a male sexual logic. Her own sexuality and desire are almost erased and the focus is on the meaning of sex as something that he does to her, which positions men and women asymmetrically in terms of power. This version of heterosexual passion is drawn upon a discourse of heterosexual ideal, bliss and erotic fantasy, realized by visual resources such as colour, issues of modality, lighting and decontextualization, which give the couple a more ethereal, universal condition, to which women as consumers should aspire.

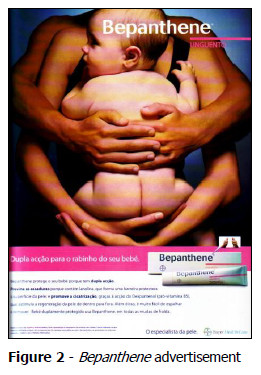

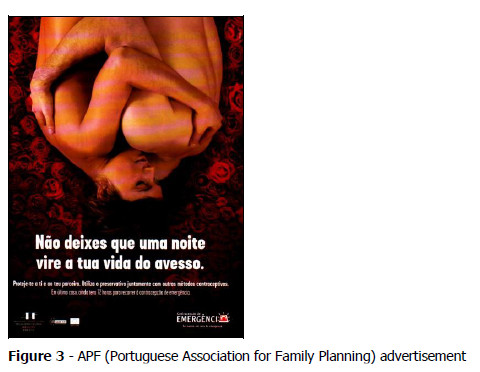

- Heterosexuality as Reproduction

A number of coexisting and sometimes competing discourses contribute to create representations of heterosexuality that express the heteroreproductive norm. Women and men are biologically different (anatomically sexed bodies). These differences are the basis of their sexual attraction and this leads naturally to biological reproduction. In this dominant heterosexual discourse, Sex is constructed as a natural force that exists prior to social arrangements, as 'unchanging, a-social and transhistorical', as Rubin ([1984] 1999: 149) put it.

Two images are used to illustrate this point (figures 2 and 3). One of the images, figures 3, is not commercial, but is a part of a Portuguese public campaign to prevent unwanted pregnancy aimed at young people, and was published in women's magazines. Although these two images have different purposes, their visual resources are used to construct biological difference as the basis of 'natural' sexuality in a very similar way: the emphasis is on the visualization of bodily difference (a feminine vs. a masculine body), which is at the core of framing of sex and sexuality as a natural given. Nudity emphasizes bodily difference and seems to point to a pre-civilization imaginarium (where nature was not 'corrupted' by culture (symbolized by clothes)) of basic sexual instincts and reproduction drives.

Both images construct a link between sexuality and reproduction. However, this is done in a somewhat different way, drawing upon different discourses, which are brought together through a specific interplay between visual features and linguistic ones, structured by a top and bottom compositional organization. This polarised structure gives to the visual elements placed on the top meanings of 'ideal', evoking dominant discourses of heterosexuality, and to those placed on the bottom more realistic ones, as the text serves to give more specific information on the product, or more practical information (details on the product, or practical consequences and directions for action in heterosexual relationships) and draw upon a set of more realistic heterosexual discourses. This means that the visual top is used, in terms of actions and participants (the representational meanings), to construct a romantic, harmonious and an apparently gender balanced relationship, while at the textual bottom other meanings emerge, such as double moral standards and different roles in terms of reproduction and child care. It is important, nevertheless, to say that this interplay is not, in fact, that linear. There are contradictory discursive elements in both parts of the image. It is through this position that female consumer viewers are invited to take up a subject position in the 'couple matrix' (Finn, 2005: 63).

Figure 2 is, in terms of composition, a vertically, polarized image, and separates (through framing resources) a top-ideal space (the 'family') from a bottom-real space (the image of the actual product - the cream - and the informational text). It presents a traditional symbol of the nuclear family (mother, father and baby). Heads of both the woman and the man are cut from the framing, which favours a more abstract, generic essence of their naked bodies and their ability to reproduce biologically. It is an idealized version of coupledom heterosexuality, based on harmony and emotional closeness in the family (marriage) or cohabitation context. Slight dark lighting from the behind with a blue brighter aura around the human participants gives this picture of heterosexual bliss a timeless, ethereal and almost divine meaning. This idealized model of heterosexuality is conservative as it entails emotional connection and a relationship between opposite sex individuals and a child who should be brought up within the presence of a father and a mother.

Less conservative gender meanings are however present in this visual idealisation. The emotionally and sometimes physically absent father from the past is replaced by a sensitive, tender father, who shows emotion and physically touches his child. But this more modern version of gender appropriate roles in family life does not stand by itself, due to the conservative meanings articulated at this same visual level that are reinforced by the textual one. She is constructed as the primary caretaker, while he is shown as the protector of the family (woman and child). And this is linked to their bodily appearances, which emphasises sexual and biological characteristics as determining gender roles and identities and their gender appropriated action. Her body and touch is more delicate as opposed to his muscular body and strong big hands. She is the one holding the baby; he puts his arms around his family to protect them both, and has the baby's back and the women's back in a protective embrace. The baby's body is against hers/his mother breasts, as representing the mother's emotional and biological bond to the child. Due to compositional features, the woman is closer (more in the foreground) to the viewer, and compositionally is more salient, and this means that the viewer is invited to identify with the female part of this couple. This visual interpellation helps to clarify and at the same reinforces the meaning of the possessive pronoun 'your baby' - 'o seu bebé'. In Portuguese the expression 'o seu bebé' does not indicate by itself the sex of the interpellated consumer. It only indicates, because it is singular, that the ad addresses only one parent: the one responsible for changing the dippers and applying the cream. Both image and text express that the parent addressed is, in fact, the female part of the couple.

This allows us to conclude that the ideal constructed by this image is a gender-differentiated version of parenthood that draws upon traditional motherhood discourses, where femininity is seen as closely related to childbearing and child care and with the need of a man's protection, and female sexuality is reduced to procreation.

While the previous image constructs a version of heterosexual reproduction based on a family/Christian discourse about heterosexuality, figures 3 draws upon an articulation of contradictory heterosexual discourses: the conservative 'have/hold discourse' (visually expressed by the representational meanings of the picture placed at the top of the ad, with a more 'permissive discourse' (Hollway, 1984), expressed by the interactional meanings produced by both textual and visual features.

The ad values as the ideal the heterosexual encounter that is romantic - lighting, red roses (symbols of romantic passionate love), and idyllic bodies (beautiful, properly feminine and properly masculine, beautifully shot). Part of this ideal is also the assumption that both sexes have the right to express their sexuality. This balance, free sexuality and pleasure, is realised visually through compositional features (symmetry) and poses (lying on a surface), body display (nudity) and the facial expression of the woman, indicating sexual intercourse occurred before this shot. It seems that pleasure and enjoyment are valued over reproduction. But sexual pleasure in a realistic way is absent from the image through the choice of de-sexualized bodies and of modality that favours a non-realistic set, a choice that already activates a somehow more moralistic discourse. Sex occurs in fact, for what we can see in the visual part of the ads, in an emotional, not free from deep feelings way. Only the woman's face is shown along with a peaceful facial expression that does not seem to mean mere physical pleasure but emotional involvement. These visual features activate moral preferences to pair female sexuality with emotional involvement and relationship commitment, which evoke the traditional model of couple relationships that is a part of the 'have/hold discourse'.

At the place of the real, however, women are positioned as someone who has 'one-night-stands', and heterosexual sex is constructed in the context of casual encounters. The written text makes a reference to 'uma noite' ['one night']), which presupposes that sex in real life may not occur in the context of a monogamous emotional relationship. But this choice is presented as a dangerous choice, as it carries with it the risk of unwanted pregnancy ('Não deixes que uma noite vire a tua vida do avesso' ['Don't let one night turn your life upside down']). It is to this female viewer that the linguistically expressed warning is directed to ('o teu parceiro' ['your partner' (male)]), meanings that are reinforced by some visual features (we see the woman's face and not the man's, and the idea of danger is produced by the dark lightening and the black (the mysterious/the unknown) and red colours (symbol of danger associated with blood). This kind of warning presupposes a viewer that does not want to get pregnant and that does not take up the subject position of dominant 'pro-natality' discourse and dominant gender ideology that constructs maternity as something natural for women, and as something they necessarily want in the context of heterosexual couple relationships. But this viewer is explicitly reminded that men can do what they want, women have to be careful and protect themselves ('Protege-te a ti e ao teu parceiro' ['Protect yourself and your partner' (male)]) (male). This shows that those women who endorse a more sexual permissive discourse are implicitly condemned by their free sexuality and made responsible and blamed for its 'bad' consequences. As they are the only ones who are responsible for the unwanted pregnancy, they should be the ones who should avoid it.

So, this ad illustrates the way the discourse of free female sexuality has been 'colonised' (Chouliaraki & Fairclough, 1999) by the discourses of public health which carried with them moralistic and gendered meanings disguised under their utilitarian logic (Lupton, 1995). Since the nineteenth century the discourse of public health has represented women as guardians of their families' health, and has targeted them for intervention as agents of regulation, for example, as the 'responsible' partner in heterosexual relationships in aids campaign (Lupton, 1995). In spite of the utilitarian logic and the scientific neutrality that is suggested by the activation of a fertility control discourse, the way women are invited to take up a position for the performance and articulation of sexual subjectivity is in fact equivalent to saying that the best thing women can do is really to avoid causal sex and stick to the old but allegedly safer romantic coupled-for-ever type of heterosexual relationships. At the same time, the re-affirmation of the binary coupledom/promiscuity, expressed by the opposition between anonymous sex and committed-sex as the only two possible forms of female sexuality, ignores the multidimensional character of gender and sexual practices of everyday life and excludes any other sexual configuration. From a public health point view, it is important to stress that this kind of advices may have boomerang effects, and not be able to target the most common risks of unwanted pregnancy which occurs, in fact, in the context of 'safe-havens' (Finn, 2005). So, it may contribute to producing what it wanted to prevent in the first place.

5.2. Female Centred Heterosexuality

Contrary to the 'hetero coupledom' type of representation, 'female centred heterosexuality' is a representation of way of doing heterosexuality out of the dyadic bond with traces of less conservative gender and sexuality discourses. The assignment of gender appropriate roles and identities is looser or less straight, as dichotomy is less visible (though differences between genders are present in the ads). Female sexuality is presented as more agential, autonomous and free to express itself, which points out to a more equal representation of desire between women and men bounded up with 'permissive discourse' meanings.

The two configurations of non-couple heterosexuality that we are going to analyse here are particularly interesting because they activate vital points in the challenging of the sexual double standard: women's bodies are desiring bodies and women are free to express and fulfil their fantasies; and women are presented as active desiring sexual subjects who pursue their needs and initiate sexual activity. Though this is quite clear, these 'emancipatory' discourses nonetheless coexist in the ads with more traditional discourses concerning female sexuality that draw upon meanings of passivity and receptivity on the one hand, and deviance and danger on the other.

- Female Sexuality as Bodily Desire and Fantasy

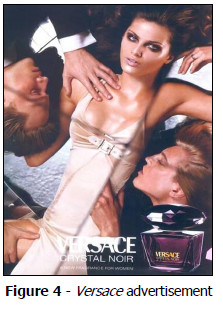

Figure 4 constructs the female body as a desiring body (sweat, parted legs, facial expression - gaze and semi-parted lips - are representational features that realized this) and erotic activity is framed under a female fantasy: two men for one woman is the reversal of the 'threesome' - with two women - and lesbian classic male fantasies. This construction takes the reversal forward for several reasons: it subverts the classic visual features associated with masculinity and femininity, plays with boundaries of sexual difference through the androgyny appearance of one of the male models, and challenges traditional masculine refusal to share a female ('natural' masculine jealousy) or to get erotically close to other men (homophobic fears).

The erotic sexual fantasy seems to be a feminine one, and also one that entails a feminine viewer. Interactional and compositional meanings realize this. The model's gaze is a demand for the viewer to get into the fantasy and to identify with a beautiful woman who is able to attract several men and to gain pleasure from it. Identification with the feminine model is also constructed by other visual resources: she is placed in the centre of the image, is shown almost in full figure and is more salient (composition), while the two men appear on the sides, cropped and fragmented; and she is shot from a frontal angle, while they appear in profile, which does not allow their visual features to be visible.

However, and in spite of its transgressive aspects, this image expresses discourses that position women as objects of male desire and articulates traditional notions around female passivity/responsiveness and male activity/drive. Men are the actors; women are the goals. They touch, grab and get close to women - vectors are quite visible - while she lays there in a passive, submissive pose, showing herself as sexually available. Her powerless position is reinforced by the choice of a high angle, which has the effect of showing her body as submissive and of conferring power to the viewer, who has to go down to get into the fantasy. Moralistic meanings may be attached to this. On the other hand, the model's thin body, long blond hair, 'sexy' dress, visible breasts and delicate feminine features connect female sexuality and body with traditional feminine (gender) meanings and construct corporeality and appearance as a crucial feature of gendered female sexuality. Far from offering a more hopeful version of femininity, this emphasis re-locates women in their bodies, indeed as bodies, that still primarily define themselves in terms of their relationship to male bodies. A dualistic way of thinking about bodies lies in this emphasis, coming from classical times, and views the female body as 'open, receptive and penetrable, inwardly focused, and passive', and the male body as 'impenetrable, outwardly focused, and active'(Potts, 2002: 187).

- Female Sexuality as Active Seduction

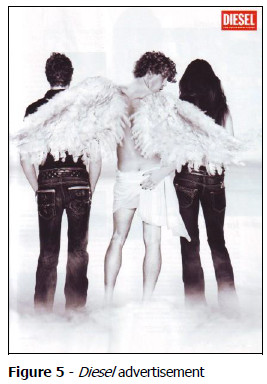

Figure 5 draws upon a particularly recurrent representation of non-coupledom heterosexuality - the sexual triangle - but it evokes discoursal traces of a less frequent representation female sexuality, an agentive one. The woman is shown taking the initiative (she grabs the angel's butt) and trying to seduce a participant that is not usually seen as sexual (an angel) - she is the actor and he is the goal. As the other man is 'human', dressed in the same way as she is, and is positioned symmetrically in relation to the woman, and therefore shown as her 'partner', the image constructs the woman as having a deceiving and deviant sexuality (she does it on his back). This activates notions of fidelity/monogamy vs. infidelity, and of feminine sexuality as a dark continent, as Freud used to invoke.

Although the female figure is shown as actively desiring and allowed to claim possession of an active sexuality, she is also constructed as the seductive temptress who is capable of alluring the angels and challenging monogamy with her 'predatory sexuality'. Several religious and mythological discourses and meanings are called upon to make up this representation: Adam and Eve, Pandora, the sirens that attract sailors to their death are only a few of those who present the woman as responsible for sin and humanity doom. As the angel and Heaven are present, a religious Christian discourse is more clearly visible. Angels are described in this discourse merely as spiritual beings, an as possessing an ethereal body, that might be led to sin when tempted by human women (demons were born from that sinful union).

The image re-constructs this imaginary which links female active sexuality to sin and danger and also draws upon a male sex drive discourse to explain why the male angel cannot resist her. While the representational resources - participants, actions and settings - construct this narrative as one in which the woman has and active part and they also evoke notions of sin and deviant sexuality - namely through symbols - interactional and compositional aspects realize some distance and non-involvement of the viewer with an agentive female sexuality. The non-realistic and decontextualized setting, along with black and white colour lower modality, construct this situation as a fantasy, not something that the viewer sees in reality or might be involved with (the back view realizes minimum involvement). In fact, the viewer is positioned as someone who identifies with the 'fallen angel' (when he 'turns' in the viewer's direction to show his sexually aroused facial expression) and not with the empowered sexual subject, the female figure that takes the initiative.

The image does not therefore construct female agentive sexuality as 'natural', 'normal' or 'proper', but as immoral and 'bad' as it clearly brings to mind discourses that position female sexuality dichotomously either as asexual and responsive to male needs or actively sexual, immoral and bad. More importantly, the reason why the display of active sexuality is seen as deviant is because female sexuality is believed to be naturally passive (Hollway, 1984).

Conclusions

Our analysis of the visual features of hetero ads showed two kinds of representations of heterosexuality: hetero coupledom and female centred heterosexuality. In the first one, i.e. the classical form of a narrative of romance and desire, we identified visual traces of the discourse of proper femininity and masculinity articulated with coexisting 'have/hold' and 'male sex drive' discourses (Hollway, 1984). The way the viewer is positioned towards the image reveals traces of a 'predatory female discourse', whose empowering effects are in fact quite apparent as female sexuality and desire is still understood under a receptive frame. Hetero coupledom comprises also images that construct biological difference as the basis of 'natural' sexuality and a link between sexuality and reproduction. The articulations of discourses on these two ads, a commercial and a health public one, is done through a specific interplay between visual features and linguistic ones and a top and bottom compositional organization. This orchestration works to instantiate contradictory features of discourses on appropriate roles in family life and on casual sex. These two ads interpellate the female viewer as a gendered subject, and the way casual sex is framed in the discourse of fertility control denies the right to a free female sexuality and contributes to reinforce the binary coupledom/promiscuity.

On the second one - female centred sexuality - we explored the classical sexual format of the 'ménage à trois', the context where notions of an agential, autonomous and free female sexuality are evoked. We explored the ways they coexist with more traditional female sexuality discourses embedded with meanings of passivity and receptivity, on the one hand, and deviance, sin and danger, on the other hand. In spite of their transgressive aspects, these images still reproduce the restricted meanings of women's sexual bodies as 'the mysterious place for others' of the past.

References

Belsey, C. (1994) Desire: Love Stories in Western Culture, Oxford: Blackwell. [ Links ]

Bryant, J. (2004). 'Sex, Subjectivity and Agency: A Life History Study of Women's Sexual Relations and Practices with Men' (Publication no. 2123/575). Retrieved 10-05-2007, from University of Sydney. Behavioural and Community Health Sciences: http://hdl.handle.net/2123/575 [ Links ]

Bucholtz, M. & Hall, K. (2004) 'Theorizing Identity in Language and Sexuality Research', Language in Society, 33(4): 501-547. [ Links ]

Buitoni, D. (1986) Imprensa Feminina, S. Paulo: Editora ática. [ Links ] [ Links ]

Butler, J. (1993) Bodies that Matter. On the Discursive Limits of Sex, New York: Routledge. [ Links ]

Cameron, D. & Kulick, D. (2003) Language and Sexuality, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

Chouliaraki, L. & Fairclough, N. (1999) Discourse in Late Modernity: Rethinking Critical Discourse Analysis, Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press. [ Links ]

Connell, R. & Dowsett, G. (1999) '"The Unclean Motion of the Generative Parts": Frameworks in Western Thought on Sexuality' in Aggleton, P. & Parker, R. (eds.), Culture, Society and Sexuality: A Reader, London: UCL Press, pp. 179-196. [ Links ]

Connell, R. W. (2002) Gender, Cambridge: Polity Press. [ Links ] [ Links ]

Cortese, A. (1999) Provocateur. Images of Women and Minorities in Advertising, Lanham, Boulder, New York & Oxford: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers. [ Links ]

Cover, R. (2006). 'Producing Norms: Same-Sex Marriage, Refiguring Kinship and the Cultural Groundswell of Queer Coupledom'. Reconstruction, 6(2). Retrieved from http://reconstruction.eserver.org/062/cover.shtml [ Links ]

Crawford, M. (1995) Talking Difference: On Gender and Language, London: Sage. [ Links ]

Fairclough, N. (1989) Language and Power, London: Longman. [ Links ]

Fairclough, N. (1992) Discourse and Social Change, Cambridge: Polity Press. [ Links ]

Fairclough, N. (2001) Language and Power (second ed.), London: Longman. [ Links ]

Finn, M. (2005) The Discursive Domain of Coupledom: A Post-Structuralist Psychology of Its Productions and Regulations, Unpublished PhD, University of Western Sydney, Sydney. [ Links ]

Foucault, M. (1972) The Archaeology of Knowledge and the Discourse on Language, New York: Pantheon. [ Links ]

Gavey, N., McPhillips, K. & Braun, V. (1999) 'Interruptus Coitus: Heterosexuals Accounting for Intercourse', Sexualities, 2(1): 35-68. [ Links ]

Gill, R. (2008) 'Empowerment/Sexism: Figuring Female Sexual Agency in Contemporary Advertising', Feminism & Psychology, 18(35): 35-60. [ Links ]

Goffman, E. (1979) Gender Advertisements, New York: Harper and Row. [ Links ]

Harrison, W. (2006) 'The Shadow and the Substance: The Sex/Gender Debate' in Davis, K., Evans, M. S. & Lorber, J. (eds.), Handbook of Gender and Women's Studies, London: Sage, pp. 35-54. [ Links ]

Hodge, R. & Kress, G. (1988) Social Semiotics, Oxford: Polity Press. [ Links ]

Hollway, W. (1984) 'Gender Difference and the Production of Subjectivity' in Henriques, J., Hollway, W., Urwin, C., Venn, C. & Walkerdine, V. (eds.), Changing the Subject: Psychology, Social Regulation and Subjectivity, London: Methuen, pp. 227-263. [ Links ]

Hollway, W. (1989) Subjectivity and Method in Psychology: Gender Meaning and Science, London: Sage. [ Links ]

Jewitt, C. & Oyama, R. (2001) 'Visual Meaning: A Social Semiotic Approach' in van Leeuwen, T. & Jewitt, C. (eds.), Handbook of Visual Analysis, London: Sage, pp. 134-156. [ Links ]

Kress, G. (1985) 'Ideological Structures in Discourse' in Van Dijk, T. (ed.), Handbook of Discourse Analysis, London: Academic Press, pp. 15-31. [ Links ]

Kress, G. (1989) Linguistic Processes in Sociocultural Practice, Oxford: Deakin University, Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

Kress, G. & van Leeuwen, T. (1996) Reading Images: The Grammar of Visual Design, London: Routledge. [ Links ]

Kress, G. & van Leeuwen, T. (2001) Multimodal Discourse: The Modes and Media of Contemporary Communication, Oxford: Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

Lazar, M. (2005) 'Politicizing Gender in Discourse: Feminist Critical Discourse Analysis as Political Perspective and Praxis' in Lazar, M. (ed.), Feminist Critical Discourse Analysis: Gender, Ideology and Power, New York: Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 1-28. [ Links ]

Lazar, M. (2006) '"Discover the Power of Femininity!": Analysing Global "Power Femininity" in Local Advertising', Feminist Media Studies, 6(4): 505-518. [ Links ]

Leiss, W., Kline, S. & Jhally, S. (1990) Social Communication in Advertising: Persons, Products and Images of Well-Being (second ed.), Ontario: Nelson Canada. [ Links ]

Lupton, D. (1995) The Imperative of Health: Public Health and the Regulated Body, London: Sage. [ Links ]

Machin, D. & Thornborrow, J. (2003) 'Branding and Discourse: The Case of Cosmopolitan', Discourse and Society, 14(4): 453-471. [ Links ]

Messaris, P. (1997) Visual Persuasion: The Role of Images in Advertising, London: Sage. [ Links ]

Mistry, R. (2000). 'From "Hearth and Home" To a Queer Chic: A Critical Analysis of Progressive Depictions of Gender in Advertising'. Retrieved from http://www.theory.org.uk/mistry-printversion.htm [ Links ]

Mooney-Somers, J. (2005) Heterosexual Male Sexuality: Representations and Sexual Subjectivity, Unpublished PhD Thesis, University of Western Sydney, Sydney. [ Links ]

Mota-Ribeiro, S. (2005) Retratos de Mulher: Construções Sociais e Representações Visuais no Feminino, Porto: Campo das Letras. [ Links ]

Mota-Ribeiro, S. (2011) Do Outro Lado do Espelho: Imagens e Discursos de Género nos Anúncios das Revistas Femininas - uma Abordagem Socio-semiótica Visual Feminista, Unpublished Doctoral thesis, Universidade do Minho, Braga, http://hdl.handle.net/1822/12384. [ Links ]

Mota-Ribeiro, S. & Pinto-Coelho, Z. (2011) 'Para além da SuperfÃcie Visual: os Anúncios Publicitários Vistos à Luz da Semiótica Social - Representações e Discursos da Heterossexualidade e de Género.', Comunicação e Sociedade: Publicidade - Discursos e Práticas, (ed. Helena Pires), 19: 227-256. [ Links ]

Myers, G. (1994) Words in Ads, London: Edward Arnold. [ Links ]

O'Barr, W. (2006) 'Representations of Masculinity and Femininity in Advertisements', Advertising & Society, 7(2): 1-35. [ Links ]

Padgug, R. (1999) 'Sexual Matters: On Conceptualizing Sexuality in History' in Aggleton, P. & Parker, R. (eds.), Culture, Society and Sexuality: A Reader, London: UCL Press, pp. 15-28. [ Links ]

Pinto-Coelho, Z. & Mota-Ribeiro, S. (2006) 'Sex, Gender and Ads: Analysing Visual Images and Their Social Effects', Paper presented at the IAMCR 2006 Conference, [ Links ] Knowledge Societies for All: Media and Communication Strategies, The American University of Cairo, Cairo, Egypt.

Potts, A. (2002). 'Homebodies: Images of 'Inner Space' and Domesticity in Women's Talk on Sex'. Journal of Mundane Behavior - Special Issue on Mundane Sex, 3(1). Retrieved from http://www.mundanebehavior.org/issues/v3n1/potts.htm [ Links ]

Puustinen, L. (2000) 'Advertising Design as Technologies of Gender' in Koivunen, A. & Paasonen, S. (eds.), Conference proceedings for Affective Encounters - Rethinking Embodiment in Feminist Media Studies, Turku: University of Turku, School of Art, Literature and Music - Media Studies, pp. 203-212. [ Links ]

Rich, A. (1980) 'Compulsory Heterosexuality and Lesbian Existence', Signs, 5: 631-661. [ Links ]

Rossi, L.-M. (2000a). 'Masculine Women: Viable Forms of Media Representation? Options for Gender Transitivity in Finnish Television Commercials'. Paper for the 4th European Feminist Research Congress, Bologna 29.9.-1.10.2000. Retrieved from http://www.women.it/cyberarchive/files/rossi.htm

Rossi, L.-M. (2000b) 'Why Do I Love and Hate the Sugarfolks in Syruptown? Studying the Visual Production of Heteronormativity in Television Commercials' in Koivunen, A. & Paasonen, S. (eds.), Conference proceedings for Affective Encounters - Rethinking Embodiment in Feminist Media Studies, Turku: University of Turku, School of Art, Literature and Music - Media Studies, pp. 213-225. [ Links ]

Rossi, L.-M. (2005). 'Sugarfolks in Syraphill? Studying the Visual Production of Heteronormativity in Advertising, Especially in Television Commercials'. Retrieved from http://www.kistan.is/efni.asp?n=3637&f=3&u=43 [ Links ]

Rubin, G. (1975) 'The Traffic in Women: Notes on the 'Political Economy' of Sex' in Reiter, R. (ed.), Toward an Anthropology of Women, New York: Monthly Review Press, [ Links ]

Rubin, G. ([1984] 1999) 'Thinking Sex: Notes for a Radical Theory of the Politics of Sexuality' in Aggleton, P. & Parker, R. (eds.), Culture, Society and Sexuality: A Reader, London: UCL Press, pp. 143-179. [ Links ]

Scott, J. W. (1999) 'Gender as a Useful Category of Historical Analysis' in Aggleton, P. & Parker, R. (eds.), Culture, Society and Sexuality: A Reader, London: UCL Press, pp. 57-75. [ Links ]

Sunderland, J. (2004) Gendered Discourses, New York: Palgrave Macmillan. [ Links ]

Tseelon, E. (1995) The Masque of Femininity, London: Sage. [ Links ]

Ussher, J. (1997) Fantasies of Femininity: Reframing the Boundaries of Sex, London: Penguin. [ Links ]

Van Dijk, T. (1998) Ideology: A Multidisciplinary Approach, London: Sage. [ Links ]

Weatherall, A. (2002) Gender, Language and Discourse, London: Routledge. [ Links ]

Weitz, R. (1998) 'A History of Women's Bodies' in Weitz, R. (ed.), The Politics of Women's Bodies - Sexuality, Appearance, and Behavior, Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 3-11. [ Links ]

Williamson, J. (1978) Decoding Advertisements: Ideology and Meaning in Advertising, London: Marion Boyars. [ Links ]

Winship, J. (1980) 'Sexuality for Sale' in Hall, S., Hobson, D., Lowe, A. & Willis, P. (eds.), Culture, Media, Language, London: Hutchinson, pp. 217-223. [ Links ]

Winship, J. (1987) Inside Women's Magazines, London: Pandora. [ Links ]

Winship, J. (2000) 'Women Outdoors. Advertising, Controvery and Disputing Feminism in the 1990s', International Journal of Cultural Studies, 3(1): 27-55. [ Links ]

Wodak, R. (1997) 'Introduction: Some Important Issues in the Research of Gender and Discourse' in Wodak, R. (ed.), Gender and Discourse, London: Sage, pp. 1-20. [ Links ]

NOTAS

1 The specific meanings of these connotations can be checked in point 5.

2 Some visual structures and features were added in the representational dimension and there was a selection of the most adequate features from Kress and van Leeuwen's grammar (Mota-Ribeiro & Pinto-Coelho, 2011).