Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Acessos

Acessos

Links relacionados

-

Similares em

SciELO

Similares em

SciELO

Compartilhar

Observatorio (OBS*)

versão On-line ISSN 1646-5954

OBS* vol.7 no.4 Lisboa set. 2013

Entrepreneurial journalism education: where are we now?

María José Vázquez Schaich*, Jeffrey S. Klein**

* Universidad de Navarra, Spain; Universidad Casa Grande, Ecuador

** Annenberg Center on Communication Leadership and Policy, University of Southern California, United States

ABSTRACT

The purpose of this investigation is to evaluate the state of the entrepreneurial journalism courses through the lecturers perspective. We conducted a survey with thirty-three lecturers from the US, UK, Canada, France, Colombia and Mexico to understand in more depth the courses objectives and structures; their integration to schools curriculums; challenges and obstacles faced by lecturers; availability and use of teaching resources; and lecturers profiles.

Keywords: Education; entrepreneurial journalism; digital journalism; innovation; journalism schools

1. Introduction

The media industry is undergoing one of the most intensive periods of experimentation in its history, and so too are journalism schools. As Eric Newton, Senior Advisor to the President at Knight Foundation noted, Universities can help lead the way through the era of creative destruction. But only if they are willing to destroy and recreate themselves (Newton, 2012). There are at least two clear trends in the way journalism schools are adapting to the digital era and transforming themselves to stay relevant. First, journalism schools intend to play a more active role as innovation labs in the development of a new media ecosystem. Anderson et al. (2011) and Lenhoff (2011) compare this trend to that of a teaching hospital model. As explained by Anderson et al.: Just as teaching hospitals dont merely lecture medical students, but also treat patients and pursue research, journalism programs should not limit themselves to teaching journalists, but should produce copy and become laboratories of innovation as well (Anderson, 2011, 1-2).

Second, they are transforming their curricula to emphasize multi-faceted digital skills as well as business, management and especially entrepreneurship. Journalism schools had historically prepared students for the newsroom paradigm, according to Professor Seth Lewis (2010). But that model is in steady decline. Thousands of journalists jobs have been eliminated in newsrooms around the world, and many journalists didnt understand the fundamental change in newspaper economics that was driving the staff reductions. It is time that journalists learn to take responsibility for their own brands and participate actively in the business strategies that affect their craft.

The newsroom paradigm isolated journalists from the business side of the companies they worked in, and from the basic notions of economic value creation for their organizations, something that many media management scholars such as Alfonso Nieto (1973, p. 103) have been warning about for some time: that the traditional wall between editorial and management kept journalists from understanding and participating in strategic issues affecting the future of their business. Robert G. Picard recently referred to this matter as the biggest mistake of journalism professionalism (2010), and Geneva Overhaulser, former journalist and current director of the journalism school at USC Annenberg School of Communication & Journalism claimed that this wall had bad effects on journalists and got them disengaged from the audience (The Paley Center for Media, 2010). In that respect, John Harris, editor in chief of The Politico and Politico.com recently called upon students and educators to embrace the conception of journalists as free agents and individual value creators: You the journalist are the franchise, what value do you bring and how transferable is that value? (The Paley Center, 2010).

The current turmoil in the industry is making that point even more clear. According to Stephen Shepard, dean of the CUNY Graduate School of Journalism, it came to be recognized that journalists needed to play more of a role in the future of their enterprises" (as cited in Benkoil, 2010). In this context, journalism schools are responding by integrating multimedia and digital and technological skills to the curriculums, but also by enhancing their students understanding of the business side of news and the economics of the digital landscape.

Although media management courses are not new for many schools, what might change is the reason why they are relevant to journalism students now, their focus, and more importantly what is also new is the growing introduction of entrepreneurial journalism courses. Given the precarious labor market, and the low barriers to entry in the digital world, entrepreneurship skills will enable graduates to create their own jobs and create value in new and transforming legacy media organizations.

In Latin America, Europe but especially in the US, the number of journalism schools offering entrepreneurial education at the graduate and undergraduate level is growing steadily (Breiner, 2013; Glenn, 2013; Anderson, 2011; Benkoil, 2010), and scholars already started studying the courses potential advantages for journalism curriculums, students and professionals (Baines and Kennedy, 2010; Hunter and Nel, 2011; Ferrier, 2011).

On January 2010 about thirty educators participated on a conference call organized by Jeff Jarvis, director of the Tow-Knight Center for Entrepreneurial Journalism, to discuss how they implemented entrepreneurial courses in their journalism schools. According to Jarvis (2010), all participants agreed on the idea that students today need to understand the economics of news and that its important to bring entrepreneurship to the industry but there were different approaches, for example, regarding the focus of the entrepreneurial training they should translate to students: new venture oriented vs. concentrating on fostering innovation and entrepreneurship on legacy media companies. Even the highly regarded and traditionally staid academic institution, Columbia University Graduate School of Journalism, now has a required half-course for all masters candidates entitled the business of journalism (which has been taught by one of the authors).

For this study we intended to assess the evolution of entrepreneurial journalism courses and programs through the lecturers perspective: lessons learned; courses characteristics; relevance of the courses; main obstacles and challenges faced; how these contents fit into the schools curriculums; and lecturers backgrounds.

2. Method

We first comprised an extensive list of institutions at the international level offering entrepreneurial skills to journalism professionals, graduate and undergraduate students. To select the participants we analyzed past entrepreneurial journalism lecturers gatherings, asked lecturers for referrals and conducted several searches on the Internet, in books and in articles related to the topic. The list included journalism schools and institutions from US, UK, Canada, France, Colombia and Mexico. We sent sixty-five digital surveys and got thirty-three responses back (21 from the US; 8 from the UK; 1 from France; 1 from Canada; 1 from Colombia; and 1 from Mexico). The online survey was sent to participants using Google Forms. Please see the full list of respondents and their affiliations in the following blog:

http://entrepreneurialjournalismedu.wordpress.com/

The survey was divided into six sections: Each section was comprised of a set of open and closed questions:

- Course/program objectives

- Course/program structure

- Teaching resources

- Collaborations

- Lessons learned

- Lecturer profile

This paper presents a general picture of lecturers insights for every section listed. For most of the open-ended questions we conducted a content analysis of responses in order to identify certain categories and determine which topics are most frequently discussed.. In addition, some answers are exerpted here to provide context, but we recommend readers refer to the full answers available online to get more detailed information about each course/program individually7.

3. Basic characteristics of the respondents and their courses

3.1 Time teaching entrepreneurial journalism

Given that most of the pioneers in entrepreneurial journalism education participated in this study, we gained an approximate idea about the time these courses have been offered. More than half, 55% of the lecturers, answered they have been teaching these skills for three to four years; 29% responded more than five years; and 16% for one to two years. From the nine lecturers surveyed who have been teaching for more than five years, four teach in the US, four in the UK and one teaches in Colombia. So these courses are a relatively new phenomena.

3.2. Courses basic characteristics

Graduate/Undergraduate.We asked lecturers if their courses are aimed at graduate, undergraduate or professionals (respondents were allowed to select more than one option). Not surprisingly, results show that most of the courses are aimed at graduate students. Entrepreneurial journalism courses emerged at the graduate level because of the urgency to train journalists who are seeking a new career path or coping with the changes in the industry.

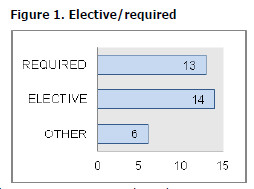

Elective/Required. The majority of courses are still elective (14 mentions), but its important to explain that the category other (see Figure 1) groups for example, professional training programs or MA and certificates exclusively focused on entrepreneurial journalism (explanations and comments can be found in the online survey), so probably these could also be considered required.

Average class size. We asked lecturers about the average class size. Responses in this subsection were varied, probably because they are dependent on the specific courses characteristics (e.g. graduate or undergraduate). For this reason we decided to analyze range frequencies instead of calculating a general average. Results showed that most of the lecturers (22 mentions) provided a number in the range between 10 and 20 students average per class.

4. Results

4.1 Course/program objectives

This section explores the objectives and focus of the programs and courses in entrepreneurial journalism.

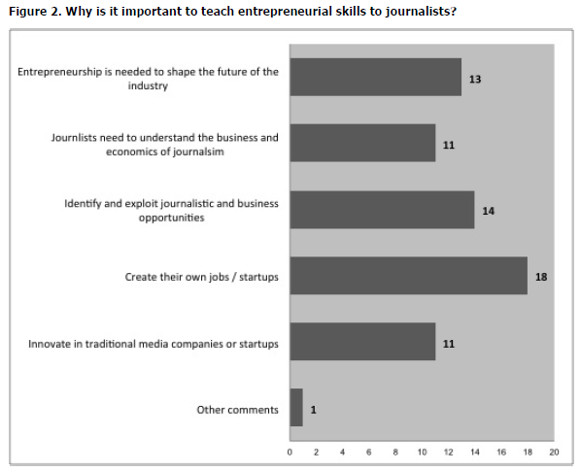

Why teach entrepreneurial journalism. First, we asked lecturers why they consider it important to integrate entrepreneurial skills with journalism education. Through the content analysis of responses to this open-ended question we were able to identify six distinct categories of reasons. The first two categories showed in Figure 2 are related to entrepreneurship as a function of the market and the focus is in the economic function of the entrepreneur, or what happens in the market when entrepreneurs act. The rest of the categories tend to focus on entrepreneurship as a process: how entrepreneurs act and create new ventures, and the focus is on the process of identifying and exploiting opportunities.

One of the important reasons discussed by lecturers is that an entrepreneurial attitude is needed to shape the future of an industry in transformation. The concept was discussed by 13 out of 33 (although is fair to say that its also implicit in most of the responses). According to David Westphal, entrepreneurial skills foster the needed cultural change in the media industry: It's important because the news culture of the last few decades has been anti-entrepreneurial. So these courses amount to almost an antidote for long-established cultures.

The next concept or category that was also widely mentioned throughout the study (in this question by 11 out of 33 lecturers) is fairly basic but not always welcomed: its an imperative in the new digital landscape for journalists to deeply understand the business and economics of journalism. This is, for most of the respondents, an essential cultural change that we believe professionals should embrace in order to confront the disruption of the industry and foster change and innovation. Another related issue mentioned several timesand that will be individually discussed in following sectionsis that this understanding of the business is essential for journalists working not only as individual entrepreneurs, but also for journalists working in established media organizations or established startups. This is also related to the first category of responses of this section (the whole industry needs an entrepreneurial mindset to shape its future). As Leslie Walker explains, News media business models have been massively disrupted, and must be reinvented for the digital age. Now more than ever journalism students need greater understanding of the business side of media and news. Even if they don't start their own news ventures, tomorrow's graduates likely will be involved in intrapreneurial initiatives for media companies.

This leads us to another related concept (mentioned by 14 out of 33 lecturers) widely discussed in this section: journalists need the skills to exploit the opportunities arising from the digital landscape and the low barriers to entry. One important concept examined in this category of responses is, as explained by James Breiner, that opportunities that arise for entrepreneurs in the digital landscape are not only business opportunities but also journalistic opportunities: Journalists have an opportunity to fill the gaps left by traditional media, which are cutting staff and coverage. There is a business and a journalistic opportunity here. The journalistic opportunity is to identify niches of reader interest not being adequately served by mass media now, and there are many: environment, education, local business, gender, local culture and language, local data, cultural coverage... the list is virtually infinite. The business opportunity is to create a community that will be attractive to both users of the community and those who want to reach that community. Beyond advertising, other possibilities for monetizing a community are direct sales of products, sale of specialized information, consulting in communication, and membership (members will often pay much more than subscribers), events and foundations, to name a few. The course is necessary because most journalists who launch a product on the web lack basic business skills, such as identifying a target audience, creating marketing to attract the target audience, developing various ways to monetize the attention on the web and so on.

The next two categories of responses were implicitly and explicitly mentioned and discussed above, and emerge together several times in the responses. The first category (mentioned by 18 out of 33) groups responses affirming that entrepreneurial skills (and the ability to identify and exploit opportunities discussed above) prepare students to create their own jobs. This is particularly relevant in a context of massive layoffs in the industry and shrinking media operations. Tim McGuire accentuated the idea of the changing labor market: Most of the jobs they will occupy during their career don't exist right now.

In the second category (mentioned by 11 out of 33) we grouped responses related to the idea that entrepreneurial skills are also essential for professionals to work in transforming media companies and new media startups that already require journalists to participate in intrapreneurial projects and embrace an entrepreneurial mindset.

Teaching focus.Next we explored two issues related to the focus of the courses/programs. First, if teaching is centered in new venture creation or intrapreneurship (that is, entrepreneurship in established organizations or corporate entrepreneurship); and second, if teaching is targeted to to non-journalism students.73% (24) of the lecturers teach in courses/programs that are focused on both, new ventures entrepreneurship and intrapreneurship (entrepreneurship in established organizations); 21% (8) in courses focused exclusively on new ventures; and none in courses exclusively focused on intrapreneurship.

Whether entrepreneurship is an activity related exclusively to new venture creation or within existing firms is a common topic in academic entrepreneurship literature. Consistent with what was discussed in the first section of this study, we found that a majority of the lecturers tend to address both approaches to entrepreneurship. Results show a conception of entrepreneurship more focused on creating and exploiting opportunities, regardless of the context where this activity takes place.

Then, we examined whether the courses are open to non-journalism students. The results show that 22 out of 33 lecturers (69%) integrate non-journalism students into their courses. In fact, some courses/programs are centered on entrepreneurship in media as a whole, including journalism. An example is the Center for Digital Media Entrepreneruship at Syracuse University, that is open to all students at Newhouse, junior, seniors, grad students, explained Sean Branagan, director of the Center: My course is broader than just entrepreneurship in journalism; we include all professional disciplines in the school and believe that this adds to the strength and vibrancy of the teams, the ideas, and business.

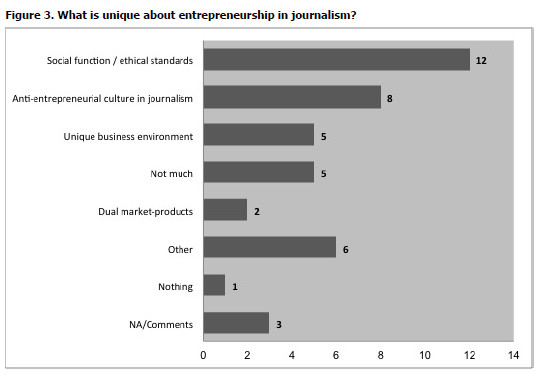

Unique characteristics of entrepreneurial journalism. In this subsection we asked lecturers what is unique about entrepreneurship in journalism and communication as compared to entrepreneurship in other businesses. Media management and media economics academic fields have been widely defined by the application of economic and management theory to the unique characteristics of media products, companies and markets. Lecturers in entrepreneurial journalism identify these unique characteristics and treat them as important issues to address, and that should no longer beused as a justification to build a wall between the business and editorial sides of the journalistic work. In fact, lecturers and entrepreneurial journalists tend to argue that these barriers were detrimental for the industry and got journalists disengaged from their audiences.

Through the content analysis of responses to the open-ended question we identified eight categories of responses (see Figure 3).

The first one, mentioned by 12 out of 33 lecturers is related to the social function, ethics and the public good nature of media products: Journalists operate with a sense of mission, and journalism is a service that is broadly considered a public good essential to democracy. In other words, there are externalities involved that are not present in many other industries. The key in teaching entrepreneurship may be to explore the nexus of how that sense of mission is supported by a business model, when the two are in conflict and mechanisms for resolving that tension, stated Kelly Toughill.

The second most cited point, by eight out of 33 lecturers (and widely mentioned throughout the study), is the anti-business culture in journalism and journalism students. This is, according to entrepreneurial journalism lecturers, a unique characteristic of entrepreneurship in journalism and media as compared to entrepreneurship in other businesses. Ava Seave agrees with this established characterization of the journalism profession: Journalists in the past didn't worry their pretty little heads about how the business they were working for prospered or didn't. In fact they purposely avoided the business side, afraid it would taint their reporting. This just didn't happen in other businesses or institutions. Even artists were more educated about business than journalists. So this is new. Moreover, Eric Scherer adds that most of the times they are even not motivated by money.

The third most cited idea (mentioned by five out of 33) is that there are no significant differences between entrepreneurial journalism and entrepreneurship in other industries or that the differences that existsome were mentioned along with this answerdont constitute a big alteration. Moreover, as Figure 3 shows, one lecturer, Alan Mutter, answered that there was nothing unique about it. This is related to what we already explained about the new attitude of entrepreneurial journalists towards the business and commercial side of their operations.

Also five out of 33 lecturers mentioned the current unique business environment as a particularity of entrepreneurship in journalism. Regardless of the disruption, the industry has been particularly resistance to change. That leads, according to Ben Compaine, to a great opportunity for entrepreneurs given the slowness of legacy media companies to innovate.

The next idea (mentioned by two lecturers) is also widely identified in media management and media economics academic research fields, and is related to the economic concept that media industries operate in a dual and even multiple product market (audience, advertisers, producers): They have more than one client, explains Angela Preciado. Although there is much experimentation going on regarding the new revenue streams, this characteristic is still relevant to journalism entrepreneurs. Leslie Walker explains it as follows: The duality of the business model for most media companieswith both advertisers and readers/producers as customersis perhaps the biggest differentiator of media ventures from other businesses. That said, the basic principles of entrepreneurship aren't very different.

Under others we grouped six responses. Lurene Kelley, for example, considers that one particularity of entrepreneurship in journalism comes from the difficulty to scale journalistic content: Entrepreneurial journalism ventures are typically more focused on original content (although not always) and, therefore, can be more difficult to scale. Content development is labor-intensive and expensive. These projects may also be niche, so scaling these types of projects can be difficult and resource-heavy. Larry Kramer believes that a particularity of entrepreneurship in media and journalism is that those skills will matter in any business now, as every company to some extend has to become a media company since communication is at the heart of all the technological changes we are going through. According to Burghardt Tenderich another unique feature about it is that it is mainly web based. This means barriers of entry are low, as are start-up costs. Andy Price referred to the concept stage of the entrepreneurial process in journalism: The proof of concept stage is very easy to reach. Sree Sreenivasan and Annette Naudin reinforced the concept that entrepreneurial journalism should be context specific. Naudin stated that, Generic business/entrepreneurship education can be too narrow and focused on core business skills rather than the specifics of media or journalism work. Issues such as social capital, networking capabilities and understanding the characteristics of the industry are key.

Creating the syllabus in a new field.In this subsection we analyzed how lecturers managed to create their syllabus in an emergent field characterized by its constant flux; particularly, we ask lecturers if they had any reference to draw from. Only nine out of 32 lectures, 28%, responded that they had a model or referred to the activity of an existing initiative when developing their course. From the lecturers that have been teaching entrepreneurship for more than five years (see above), only two said they looked at other courses when creating their syllabus: Francoise Nel and Barbara Rowlands. These lecturers are truly entrepreneurs themselves in forging new academic courses and approaches.

The most cited reference program is the Tow-Knight Center at City University of New York (CUNY), mentioned four times (three by non US lecturers). For example, Barbara Rowlands from City University London explained that although they didnt have a specific model they looked at CUNY and other programs in the United States. However, since the journalism environment is a bit different in the UK, they have added their own twist. Other programs/courses in entrepreneurial journalism mentioned once, as models, are the ones in Georgetown University, American University, Penn State, Maryland University, Arizona State University and the Knight Digital Media Center at University of Southern California. Francoise Nel from the University of Central Lancashire also expounded that in 2005 he started drawing principally on the research and activities of the Kauffman Foundation, in general, and the Newspaper Next project at the (now defunct) American Press Institute, in particular. Burghardt Tenderich from USC Annenberg M2E program mentioned non-journalism institutions, the Technology Entrepreneurship course at UC Berkeley Center for Entrepreneurship & Technology: The adaptation to media was done by the instructor, he added. James Breiner also used a non-journalism resource as one of his sources when he started in 2007 and tailored much of the material: U.S. Small Business Administration website. Jeff Jarvis from CUNY explained that although when they started they couldnt find an analog for what we were trying to do in entrepreneurial journalism, his colleague at CUNY, Jeremy Caplan, took valuable lessons from Columbia's Knight-Bagehot fellowship and MA. David Baines from Newcastle University mentioned a media company that inspired their course focus; he suggested that their syllabus reflects the recent adoption by the BBC (British Broadcasting Corporation) of an entrepreneurial mindset and culture.

4.2 Course/program structure.

In this section we analyze how lecturers translate the class objectives into practice and the obstacles they found when teaching these skills to journalists.

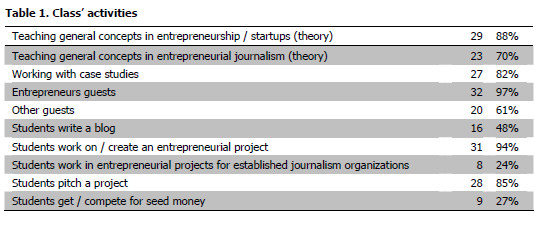

Class activities. By analyzing the available courses syllabus, reading the available publications and articles on entrepreneurial journalism education, we first identified the most common activities that lecturers use in class and then asked them to select the ones that are part of their syllabus.

The most common class activity (with 97% participation) in entrepreneurial journalism courses is inviting entrepreneurs-speakers. Several reasons could explain this. First, inviting professionals to share real life experiences with students is a common practice in general business and entrepreneurship courses, especially at the graduate level. Second, the emergence of the entrepreneurial phenomenon is relatively new in journalism; there is much experimentation going on to find the models that will fund journalism and also to discover new career paths for journalists and media professionals in the digital landscape. This implies that everybody is learning almost in real time (what works and what doesnt) from each others experiences, so speakers insights are most valuable.

As represented in Table 1, project-based learning is the second most common approach. Its important to note that learning-by-doing approaches such as project-based and field-immersion experiences are gaining more relevance in general entrepreneurship courses, especially in the startups arena. Other frequently selected activities are: working with case studies (82%), teaching general concepts of entrepreneurship (88%) and project pitching (85%).

When asked about additional teaching activities Kelly Toughill mentioned the importance of business simulation games: Our students do one course in the Faculty of Management that is based on a computer simulation of a start up. Barbra Rowlands and Lurene Kelley discussed the value of networking activities. According to Rowlands, they conduct networking evenings with experts: We have networking evenings - complete with refreshment/beer - where the students, in their start-up groups, mix with 10 or so expert guests. They do poster presentations outlining the progress of their start-ups. Kelley explained that networking with entrepreneurs is a key component of our class. Most class blog posts involved students meeting entrepreneurs. Mike Fancher conducted an interactive public forum on journalism for jobs this semester in conjunction with a course in participatory journalism. The purpose was to demonstrate the power of journalism to create engagement around a topic.

David Westphal explains that students in his class also perform group presentations that study entrepreneurs and entrepreneurial companies. Vikki Porter and Jeff Jarvis mentioned mentoring activities. According to Porter, at the Block by Block News Entrepreneurs Super Camp (professional training) they offer publishers High touch mentoring by successful experts in sales and business development including site visits and weekly chats as well as ongoing webinars for one year after a 4-day boot camp focused on development of business plan and 100-day action plan.

According to Jarvis, at the MA program in entrepreneurial journalism at CUNY, besides mentorship, they also include field-experience activities, technology training and a course in media business fundamentals: Students in the MA/certificate semester create their business plans as the core of their work. They also take an abbreviated MBA-like course in business fundamentals in the media context. We study disruption in the industry. They take technology traininge.g., in product developmentgiven to all with the ability to take specialized courses that meet their particular needs. . . They serve a brief apprenticeship in a New York startup. Being in New York is a great advantage as it brings us entrepreneurs, investors, and executives to serve as speakers, mentors, and jurors in the final judging.

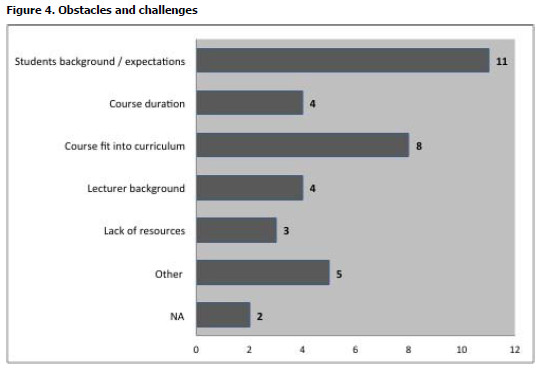

Obstacles and challenges teaching/developing the course. Next we asked lecturers about the main challenges or obstacles they faced in developing and teaching the course. Through the content analysis of responses to this open-ended question we were able to identify six distinct categories (see Figure 4).

The most commonly mentioned challenge is related to the students background and expectations (mentioned by 11 out of 33) and with concepts such as the anti-business culture of journalists and students discussed in section one. Regarding students expectations, B.J. Roche raised an interesting point on the difficulties of the entrepreneurial path: Now I worry that we're overselling entrepreneurship! It's very difficult and it requires money to start with, as well as the ability to not make a paycheck for a while, which is not in my students' profile. Once people see how hard it is to get 50,000 page views a day, they start to rethink the whole idea.

Fitting the course into the curriculum or into the schedule of the student curriculum, as was articulated bySree Sreenivasan, is the second most mentioned challenge. Lecturers referred to insufficient resources for the courses and for marketing the courses given the amount of students interested; the fact that most of them remain as electives; colleagues distinct perceptions on journalism education; and also confusion among students and colleagues regarding the aims and scope of the courses. For example, Sarah Stuteville mentioned the confusion in the department and among students about multimedia training vs. entrepreneurial journalism (are they the same thing, can they be taught in the same class?)

An additional challenge mentioned by lecturers is the courses duration and time restrictions. Four lecturers expressed this concern. Frequently, lecturers end up summarizing in one course business and economics basics, media business and economics, technology, business model generation, startup culture, etc., plus student projects. We have very little time in our very crowded program, stated Angela Phillips. Ben Compaine notes that, 14 weeks is a bit too short for a comprehensive business plan, given course load and/or full time jobs.

Also four lecturers mentioned lecturers background as a challenge. According to Mandy Jenkins, A lot of research needed to happen to make this possible... and it could use more influence from business school curricula. Tim McGuire confronted this issue when he needed to recruit new lecturers: I invented the course and it's required, but we are finding it is difficult to find other instructors. Lurene Kelley did overcome some of these difficulties by partnering with a business accelerator: While I have a strong journalism background and studied organizational communication, I have never been an entrepreneur. Fortunately, I was able to partner with an entrepreneurial accelerator willing to share their time, knowledge, and resources.

The lack of resources (mentioned three times) was widely discussed at the 2010 entrepreneurial journalism education conference call organized by Jeff Jarvis. At the conference call, and also throughout this study, lecturers expressed the need for sharing available resources (e.g. case studies).

Under other we grouped five responses. Ann Grimes mentioned the challenge of forming interdisciplinary teams. According to Vin Crosbie, there is a lack of theory development: Developing the theories that explain the changes underway in the media environment and how those changes effect the media businesses. Another interesting observation contributed by Larry Kramer is the geographic challenge. As we already explained, guest speakers is one of the most common activities in class, so the geographic barriers can easily become a challenge to some lecturers: Geographic. I'm in NYC, where most of the guest speakers are, the students are based in Syracuse. Steve Buttry addressed an interesting topic on juggling class with full-time job. As we will expose in this report, most of the lecturers are professionals, or professionals and academics. Finally, Jeff Jarvis mentioned the novelty of the courses as a challenge, especially because they were pioneers when they started.

4.3 Teaching resources

After studying the courses structure and objectives in this section we analyze the teaching resources in more depth.

Commonly used resources. We asked lecturers what kind of teaching resources they use in class. Below is the list of resources sorted by times mentioned (full answers available online may give readers better detail on each case).

- Online blog posts and articles (mentioned 23 times)

- Case Studies (20). Lecturers mentioned Harvard, Columbia Case Consortium and self-written cases as sources.

- Books (20).

- Guest speakers (10). According to the data from the teaching activities section of this report, we can guess that some lecturers didnt consider guest speakers a teaching resource and so didnt mention it again here. Some lecturers said guests sometimes participate via Skype (a solution to geographic restraints discussed above). They also mentioned some example guests such as entrepreneurs, business angels or other lecturers.

- Video: entrepreneur talks / cases / tutorials (9).For example, Ben Compaine mentioned the videos of entrepreneurs talks from Stanford and Cornell University.

- Research reports (8).

- Business, marketing and operations plans and templates (4)

- Further resources mentioned by lecturers: Class website, Facebook and Twitter groups (2), simulation games (1), one-on-one peer to peer mentoring/coaching (1), online discussion groups in online courses (1), online multimedia projects (1), media business coverage, interactive exercises, role play games (1), take students to visit working enterprises (1), mostly online resources (1).

Shared resources. Another interesting issue is whether lecturers use general entrepreneurship resources or if they mainly use entrepreneurial journalism (or media) resources. Results show that 61% (20 lecturers) use general entrepreneurship resources and 36% (13) dont. This may be the result of insufficient media entrepreneurial resources generally available.

What additional resources should be developed?Finally, we asked lecturers which resources they wish were available. Categories were defined through the content analysis of responses to the open-ended question.The most commonly mentioned resource is case studies (mentioned by nine lecturers). As we already explained, this was also widely discussed at the 2010 conference call on entrepreneurial journalism education organized by Jeff Jarvis. Andy Price added that cases should be more detailed than the ones already available. James Breiner also mentioned cases but with more rigorous standards. Annette Naudin asked for cases from international practice since the business environment and available resources (particularly philanthropic grants) are not the same in the US than in other countries.

Three lecturers mentioned Business plans and templates adapted to entrepreneurial journalism as a needed resource. Sue Heseltine and Mandy Jenkins discussed the need for textbooks. As explained by Heseltine, More texts that are specifically related to journalism. There is a lot of discussion around these issues at conferences but they haven't filtered through into many texts yet. Mandy Jenkins also referred to text adaptation: Perhaps some boiled down or Cliff's Notes versions of business school texts on startups and small businesses would be of assistance.

Two lecturers mentioned video resources. Andy Price suggested streaming practitioners interviews and Leslie Walker mentioned video talks by CEOs who are trying to pioneer new business models for news.Another resource mentioned twice is mentoring opportunities and coaching: More media entrepreneurs to come along and work with the students, explained Francoise Nel.

Other ideas mentioned are internships with journalism entrepreneurs; specialized simulation games (Kelly Toughill: I wish we had a simulation game similar to CAPSIM (which is?)that could be used as the basis for an entire course. The instant feedback of simulations is a great learning tool and allows instructors with little business background to teach complex topics. I have an MBA, but most journalism professors have a meager understanding of basic financial statements, marketing principles etc.); David Westphal suggested the need of continued support for students' projects at semester's end; Annette Naudin also discussed the need of further research (Current research on aspects of entrepreneurial journalism such as the 'lived experience'. Market research and marketing studies for students to learn from Social enterprise and new business models discussed in academic context) and critical debates (Critical debates - challenges facing entrepreneurial journalism); more resources and reports on common rules, best practices, common mistakes, added Eric Scherer; Mike Fancher mentioned the need to count with more people who are living the experience of entrepreneurial journalism; and Sree Sreenivasan suggested more syllabi.

Other lecturers added other suggestions. For example, Barbara Rowlands asked for courses to become more independent from guests: Courses like this rely on staff [to] bring in guests to mentor the students. When answering which resources he wishes were available, Mark Potts stated: It's harder to figure out what to leave out. It's a fast-changing field, and most of the syllabus comes from current or recent blog posts. It changes 40-50% year over year, as new posts become available. The business is changing so fast, it is hard for teachers to keep up with whats happening.

Annette Naudin suggested that there should be more resources also focused on small business: A focus on small business / freelance work rather than using examples from big business, and Andy Price alluded to resources that reflect ideas about social enterprise in the news business. Finally, Leslie Walker asked for a greater effort in sharing resources: It's tiring to reinvent the media business wheel, so to speak. It would be so helpful if there were more collaborative efforts among those teaching it to share resources.

4.4 Collaboration

In this section we explored courses collaboration and partnerships. We asked lecturers about the courses/programs home institutions support and also if they established partnerships with business schools or business and entrepreneurship programs.

Institutional support.First we asked lecturers if they consider that entrepreneurial journalism courses are fully supported by their institutions, since entrepreneurial journalism involves a significant cultural transformation in the journalistic practice, culture and education as well.85% (28 lecturers) feel their institution is fully supportive; 9% (3) gave an intermediate answer; and there were no negative answers. Thats a good sign of strong institutional support.

Entrepreneurship courses and broader innovation efforts at journalism schools. As explained above, several journalism schools are transforming their curriculum (integrating multimedia, business and entrepreneurial skills), playing a more active role in their communities (for example through university-based community news sites) and becoming innovation hubs (funding, training, and reporting the work of entrepreneurs, organizing conferences, establishing innovation labs, etc.). In this section we asked if lecturers consider entrepreneurial courses to be part of or integrated into those broader efforts of journalism schools toward innovation in education and research.

Results show that 79% (26) of lecturers consider their course or program to be part of a wider innovation effort; 9% (3) provided an intermediate answer (grouped in other); and a 3% (1) answered with a no.

Collaboration with/integration to media management and media economics courses. Media management and Media economics research and teaching fields have developed throughout the 20th century: lecturers and scholars from these fields were the first to integrate business concepts into journalism schools. At the same time, as our study shows, entrepreneurship lecturers consider that explaining the economics and business of the media represents a significant part of entrepreneurial journalism courses as well. On the other hand, a recent study with directors of journalism programs in the US found that entrepreneurial journalism courses were considered more important than courses in media management or media economics (Blom & Davenport, 2012). We therefore asked lecturers if their institutions offer media management or media economics courses, and (for those who answered affirmatively) how the contents of entrepreneurship courses differ from what students learn in these courses and how both type of courses are integrated.

First, we asked lecturers if their school offers any/course program in media management or media economics. Slightly less than half, 49% (16) of lecturers responded that their schools/institutions offer courses in media management or media economics, and 45% (15) responded that they dont offer these courses. Results show a certain disengagement of journalism schools from the commercial side of the industry since in almost half of these institutions entrepreneurship courses represent the first approach to the business side of journalism.

What differentiates the entrepreneurial courses from existing media management classes?

The most mentioned difference (6 times) is that entrepreneurial courses focus on creating new projects/ventures/products. Another difference is (mentioned by five lecturers) shown in Steve Buttrys response: Media management and economics courses tend to focus on managing in large media organizations and on the news industry and its larger business issues and trends. The respondents tended to relate Media management courses to established media organizations: The traditional course in media economics at UMD is much more theoretical and focused on traditional media, explained Leslie Walker.

Three lecturers explained that at their schools the courses are now merged. For example, Lurene Kelley explained how the media management and entrepreneurship contents were merged at the University of Memphis: Our entrepreneurial journalism course was actually a redesign of our media management course. So the course combines content from media management and entrepreneurialism. We also use intrapreneurship as a meeting point for the management and entrepreneurship content.

Two lecturers explained that they consider courses to be a sequence or complementary. Lastly, Farncois Nel explained how entrepreneurship is now also embedded in media management courses: We take the need to innovative as given for all our media management courses, so seek to embed the entrepreneurial mindset throughout.

Collaboration with business schools/general entrepreneurship programs.Next we explored if lecturers worked collaboratively with business schools or business and entrepreneurship programs, and also the nature of these partnerships.

When asked if they collaborated, 58% (19) of lecturers responded with a yes and 42% (14) with a no.

Eight lecturers explained that they work with an in-house business school or business/entrepreneurship program/center. Another type of collaboration (mentioned by six lecturers) consists of integrating lecturers from business schools or business and general entrepreneurship related programs to entrepreneurial journalism courses/programs. For example, Mark Potts (who answered with a no) explained that they established this type of collaboration, although now all lecturers have a journalism background: Our undergrad course was formerly taught in conjunction with a business school professor; this semester, I'm teaching itas a serial entrepreneur/business person who happens to have a journalism backgroundwith another journalism professor.

Other courses are part of the business school. Two lecturers actually explained that their courses run at the business school, as explained by Ben Compaine; or as in the case of Larry Kramer, his course is also part of the MBA program.

Finally,Two lecturers mentioned extra-mural partnerships. Andy Price referred to Teesside Entrepreneurs Society: We work with an extra-mural student initiative called, Entreprenerus@tees. We do not work with the business school in this area. Vikki Porter mentioned their collaboration with Patterson Foundation to pursue funding, recruitment, program development.

4.5 Lessons learned

We grouped the responses about the most important lessons learned in four categories.

The first category is related to lessons learned about students attitudes towards entrepreneurship. Lecturers highlighted the fact that journalists have already some entrepreneurial mindset because, as stated by Branagan, they are tenacious, resourceful, and inquisitive. They have skills as creators, storytellers and builders... all good skills of an entrepreneur. And they are comfortable working with missing information. But, at the same time, they need to be more focused on the execution: One of the obstacles is learning to stop searching and start DOING! Entrepreneurship is about DOING. Francoise Nel agreed with Branagan on these shared characteristics: That participants delight in seeing how many of the key skills (opportunity identification, networking, etc.) that are essential to success to making great journalism can also be used to help build sustainable journalism enterprises. Annette Naudin, BJ Roche and Sarah Stuteville emphasized additional entrepreneurial attitudes. According to Naudin, students need to develop confidence to explore and experiment. Roche highlighted the issue of failure: THESE KIDS ARE NEVER ALLOWED TO FAIL AT ANYTHING. In general all their lives, they've quit at things they weren't immediately good at. They are still on the "A" thing as the only measurement. This course breaks them of that thinking. They know they need to have a million ideas, and then find another million of them until they find something that works. Then they start the process of learning when it's time to persist and when it's time to give up on an ideathat's another really key skill that most grownups don't even get. Lastly, Stuteville mentioned two issues related to technology and opportunities: That students easily become fixated on learning certain technologies instead of embracing a technology-curious/flexible mindset that will serve them in a shifting media landscape. That many students still expect that they will land a traditional media job (e.g.: a job as a newspaper reporter) and aren't thinking enough about the diverse media jobs/opportunities the include/embrace journalism and journalism skills.

Eric Scherer, Burghardt Tenderich, Tim McGuire and Mike Fancher discussed lessons learned about students business background and attitude. According to Scherer, journalism students are out of touch with business and economic realities Scary! Tenderich agrees with him in that, most students lacked knowledge of basic business concepts. However, by the end of the semester, you could notice most students' business thinking had advanced. McGuire explained students change of attitude once they start the course: That kids have a very negative feeling about it when they begin but the content reveals important things to the students about themselves. Mike Fancher referred to the challenge journalism is changing: It is extremely hard to get people to re-imagine how journalism might be done differently in an interactive world.

Lastly, Sree Sreenivasasn explained that although this is hard work; there's great hunger for this among students, and Angela Preciado learned that they also get enthusiasm with the idea of being owners of their business.

Next we grouped responses related to lessons learned regarding the courses structures and activities. For example, Mandy Jenkins mentioned time constraints given the wide range of content needed for the courses: I have learned just how much work there is to not only starting your own venture, but learning all if the aspects of business that go along with it. I couldn't possibly cover everything in one class. Steve Buttry emphasized the benefits of the project-approach to teaching entrepreneurship: Students need to work in entrepreneurial projects that require them to think through business issues and problems.

Jeff Jarvis mentioned several lessons learned related to continuing support for students projects: If students do want to start their businesses, the real work of supporting them with mentorship and incubation begins as the class ends; grants: Having money to give in grants is very valuable but it can also skew the students' work too much toward the final presentation; that simply needs caution; project-based approach: We have found that individual projects work best; I wonder whether group projects might sometimes work better at undergraduate; class composition: Mixing professionalsincluding some from outside journalismwith journalism students is fruitful for all, though one needs to pay attention to the disconnects that can sometimes occur between them; admissions: For admissions, we need to have students propose businesseseven though most will changeto check their attitude toward innovation and business; content priorities: In the first year of the certificate, we gave general technology education but soon learned that more specific instruction in skills the students neede.g., project managementis more important; and finally, selecting students projects juries: Our jury is popular but we found that juries can get too big, leading to consensus decisions rather than taking risks. We adjusted for that by taking a more active role ourselves in the decisions.

Next we grouped comments about lessons learned on teaching and courses contents. For example, Larry Kramer discussed the benefits of storytelling when teaching entrepreneurship: Teaching is hard. Basic storytelling is the best form. We spend a lot of time on examples of intrapreneurism, and it's very helpful. Alan Mutter highlighted the importance of working with students individually: Students approach this with varying levels of understanding and insight. You have to work with each individual as an individual. Kelly Toughill recommended a focus on basics: Our students struggled mightily with the basic concept that a new venture must fill a perceived need, not just deliver a product; a deeper emphasis on finances: Finances were also a challenge. We went over finances once before they began working on their professional project. In the upcoming class, we will go over finances three times before they are expected to generate their own statements; and constant revision: We have realized that this stream will take more rigorous revision every year because the landscape is changing so quickly.

James Breiner explained why is it important to set the bar high: Tell students not only that they can do this, but that it is a requirement that they come up with a journalism project that they can initiate. Starting with that expectation means the participants go beyond their own expectations. Annette Naudine also added several recommendations. She referred to the need for broadening students career paths: That we need to enhance opportunities for live projects which come from a range of sources / industries - not just journalism; the need to stay critical and updated: That we need to stay critical - debate and challenge the industry / teaching methods. That we need to engage with debates through conferences, research, industry networks etc.; the need to meet the challenge of working with diverse groups: At post graduate level some of the challenges are to do with the diverse student group - this is often a neglected issue. International students still expect the UK to have a traditional media / journalism industry and causes many challenges; and finally, the need for lecturers to participate in and run real entrepreneurial projects: Enabling staff to work in practice / run projects / engage in practice based research is important in this fast changing sector.

David Westphal and Barbara Rowlands discussed the project-based approach to teaching entrepreneurship. Accroding to Westphal, It's the students' own struggle and engagement with an entrepreneurial project (feasibility of a new media startup) where the most intense learning occurs. Rowlands mentioned the benefits of working with diverse teams: I have found that even the most reluctant student is now excited by their media start-up. I have also learnt that the strongest teams are those of mixed skills (students from different pathways joining force).

Tim McGuire and Vikki Porter shared additional experiences and recommendations. Tim McGuire explained one exercise to foster business model thinking and creativity: I do one exercise where I give groups of students a business model template and then I ask them to invent a product and apply the template. The twist is the product has to be based on something in their pockets, purse or backpack. The exercise leads to wonderful creativity at the same time it teaches them the discipline of business model thinking. Vikki Porter stated that by teaching community news publishers they learned that success of news entrepreneurs is still a challenge, and she also added two recommendations for lecturers: Don't recruit showboats and that an exit strategy is as important as a business plan. Finally, David Baines highlights the importance of helping students integrate the skills to recognize and exploit opportunities: The necessity of preparing students to be able to recognize changes taking place in the media industries in general and journalism in particular and to be able to accommodate at least and ideally benefit from those changes by adapting to them and gaining new skills and knowledge throughout their career.

Finally, other lecturers added several general conclusions about teaching entrepreneurship in media. For example, Mark Potts insisted that they are not doing nearly enough of it! Vin Crosbie discussed the resistance to innovation among several journalism professors: That few journalism professors have a clue about the gargantuan changes underway in the media environment. Most simply think the change is that people are shifting their media consumption from traditional outlets to online or to new devices. The results of that misunderstanding are that they teach little more than shovelware (i.e., trying to transplant 20th Century journalism theories and practices into a new environment that doesn't support those.) I've found the students generally are more savvy about these changes than are the professors.

Leslie Walker explained that the entrepreneurial mindset proved to be valuable in different areas of students life: The big lesson or takeaway to me has been how incredibly valuable this kind of learning has been for our students in OTHER areas of their life, not just journalism and business, since entrepreneurial thinking can be applied so widely. The positive response from students has been startling and impressive; and BJ Roche mentioned certain lessons she learnt about measuring class outcomes: At first I had hoped we'd do some successful startups so I was measuring it that way and falling short. Then I realized that students don't have to do a startup to benefit from the ideas we talk about in class. Intrapreneurship can be just as valuable. Knowing how to connect with grownups about an idea can be a super-valuable skill in a job interview, for example. If you can identify a problem and solve it for an employer, you'll always have a job.

Finally, Barbara Rowlands and Lurene Kelley discussed personal lessons they learned after delivering these courses: I've learnt a lot delivering this module and it has widened my knowledge of how media startups can be monetized and combined with other industries, explained Rowlands. Kelley highlighted the evolution of her understanding about opportunities in the transforming media environment: I was fortunate enough to be chosen as a Fellow for the first Scripps-Howard Entrepreneurial Journalism Institute held at ASU this year. It was an amazing experience. That, coupled with my partnership with our local entrepreneurial acceleratorLaunchMemphishas turned me into a different type of teacher and person. I certainly see our changing media environment as one huge opportunity now, no longer the depressing wreckage of an industry I once loved. It has made me, personally, more hopeful and willing to embrace risk and change.

4.6 Lecturer profile

In this section we analyze lecturers profiles, particularly if they are professionals or academics and their experience in entrepreneurial ventures and other professional activities. Over half, 58% (19) of lecturers defined themselves as both, professionals and academics; 27% (9) as professionals; and only four lecturers, less than 12?%, as pure academics.

When asked if they have experience working in entrepreneurial ventures in journalism/media, 76% (25) of lecturers answered with a yes and 24% (8) with a no. Results show a clear predominance of professional and entrepreneurial experience among lecturers in entrepreneurial journalism, although a majority is also integrated to the academic world.

5. Conclusions and Discussion

In this paper we presented a study with 33 entrepreneurial journalism lecturers from six different countries. Full answers for this study are available online2. We wanted to assess the state of this new area of education through the lens of the lecturers themselves. We analyzed six dimensions of teaching entrepreneurial journalism: Course/program objectives, course/program common activities, teaching resources, collaborations, lessons learned and lecturers profiles.

We found that the main reasons these courses were established was to promote the entrepreneurial mindset needed to shape the future of the industry, to help students create their own jobs, and to provide them with the skills to exploit the new business and journalistic opportunities of the digital landscape.

Not surprisingly, but to our disappointment, we found that the anti-business culture of the journalism profession remains as one of the central challenges when teaching entrepreneurial journalism. Students still get to these courses with the traditional mindset probably because journalism schools are in the earliest stages of the transformation of their programs, the introduction of the new skills and the redefinition of the professional profile of the digital age journalist. This may be the reason why half of the courses are still elective and focused on the graduate and professional levels, and also the reason why it is challenging to fit these courses into existing curriculum requirements. Perhaps they also started on the graduate level because of the urgency to train professionals who lost their jobs or are starting to take advantage of the opportunities of the digital landscape to establish their own organizations.

Its clear this is a new movement. In half of the cases, the entrepreneurial journalism courses represent the first approach to teaching the business side of journalism at their schools. Half of the lecturers said their schools didnt offer previous courses in Media management or Media economics. This represents an important cultural change for these institutions. On the other hand, in the schools that did offer Media management and Economics, entrepreneurial journalism courses are still not fully integrated with these established academic fields. In most of the cases, lecturers see courses in Media Management and Media Economics as being related to established media organizations and focusing on broader economic trends of the industry, but at the same time, most of them stated that entrepreneurial journalism courses also focus on intrapreneurship (innovation in established organizations) and in explaining the business and economic trends in the industry. This reflects a disconnect and probably duplication between these courses and also suggests the need for better coordination between them. Lecturers in entrepreneurial journalism should probably concentrate their efforts in the learning by doing approach. In most of the cases lecturers try to do it all in one course (change mindset, explain the industry disruption, teach business fundamentals and finances and develop students projects), and that represents a big challenge. In fact, although most of the lecturers stated that their courses focus on intrapreneruship, only eight of them make students work in innovation projects for established media organizations.

To deal with this challenge, more than half of the lecturers in entrepreneurial journalism have already started collaborating with business schools or related institutions to developed their courses. Thats a good start, but only a start. These collaborations have been proven effective for them, but certainly they need a broader integration with their schools curriculums. Journalism schools willing to add entrepreneurial journalism courses should seriously pursue partnerships with business schools, accelerators and other real world organizations.

Morover, since Media management and Economics fields are already established research fields, scholars could collaborate with lecturers in entrepreneurial journalism in fostering academic research in this new field, publishing more new and detailed case studies and the developing simulation materials.

The makeup of the instructors is not that of a typical academic. We found that top-professionals with experience in journalism and entrepreneurship are teaching these courses. As noted by Eric Newton (2012) this shows the need to restore top news professionals to the most respected ranks of academia and thus promote the teaching hospital model for journalism schools.

There is a predominance of the learning by doing (projects), learning by listening (guests coming in) and case study approaches to teaching entrepreneurship in journalism. The dependence on case studies and guests (mostly other entrepreneurs) is related to the fact that the digital landscape is so new and rapidly changing and entrepreneurs are still mostly learning from each others experiences. This can be problematic in some geographical areas. For that reason, several lecturers mentioned that they use video resources in class but probably this could be better addressed with the development of further teaching resources (including videos) that can substitute for individual testimonies of entrepreneurs. Lecturers perceive that limited teaching resources remains as a challenge, but this factor had less an impact in the results of this study than in the conclusions of the 2010 lecturers gathering organized by Jeff Jarvis that we mentioned above; lecturers considered that there is still a need for more case studies and for developing new kind of resources and class activities.

The learning by doing teaching approach is being widely embraced by traditional business schools for coping with disrupted environments where innovation and entrepreneurial skills are key (Nohria, 2012). We also found that lecturers in entrepreneurial journalism have embraced hands on learning from the start. In most of the courses in entrepreneurial journalism students develop real world journalism projects and in some programs they receive seed money to continue developing them. Finding ways of supporting the projects when the semester ends is an effective way for motivating students and its also a way for journalism schools to promote innovation for the industry, but how to implement that support is still a challenge for most of the individual courses.

Some specialized graduate programs in entrepreneurial journalism have already managed to provide this kind of support for students. As noted by Jeff Jarvis, his 2006 course grew into a certificate and then into an MA program because he identified the importance of offering mentoring, incubation, funding and continuing education opportunities for entrepreneurs. For individual courses, besides giving students seed money, other low-cost activities can be done to support projects: some lecturers mentioned the importance of organizing networking activities so students can meet experts and entrepreneurs and have the opportunity to present their projects, and also coaching opportunities where entrepreneurs work directly in the projects with them in class. Other innovative class activities mentioned that promote the learning by doing approach are simulation games and field experiences.

Entrepreneurial journalism is new. Teaching entrepreneurial journalism is even newer. The lecturers who participated in this survey are leading the way. They have created new courses, cobbled together course materials from a variety of obscure sources, convinced struggling and successful entrepreneurs to visit their classrooms, and inspired students to think differently about their careers and the industry in which they will work. Resources are still meager. Support from some tradition-bound journalism schools is still lacking. But the road ahead is clear. The news and information industry is undergoing radical change, and journalism schools should be on the cutting edge in helping their students innovate--leading the changes, exploiting the disruption, and improving journalism, rather than simply standing by and watching it disintegrate. We hope the lessons learned shared from our colleagues help, just a bit, in this important effort.

References

Anderson, C.W, Glaisyer, T., Smith J. & Rothfeld M. (2011). Shaping 21st century journalism. Leveraging a Teaching Hospital Model in journalism education. Washington, DC: New America Foundation. [ Links ]

Baines, D. & Kennedy C. (2010). An Education for Independence: Should Entrepreneurial Skills Be an Essential Part of the Journalists Toolbox? Journalism Practice, 4 (1), 97-113. [ Links ]

Benkoil, D. (2010, September 3). Business, Entrepreneurial Skills Come to Journalism School. Retrieved from: http://to.pbs.org/d0W6s1 [ Links ]

Blom, R. & Davenport L. (2012). Searching for the Core of Journalism Education: Program Directors Disagree on Curriculum Priorities. Journalism & Mass Communication Educator, 67 (1), 70-86. [ Links ]

Breiner, J. (2013, May 17). How J-schools are helping students develop entrepreneurial journalism skills. Retrieved from: http://www.poynter.org/latest-news/top-stories/213701/how-j-schools-are-helping-students-develop-entrepreneurial-journalism-skills/ [ Links ]

Ferrier, M. (2012, August). Media entrepreneurship: curriculum development and faculty perceptions of what students should know. Paper presented at the national convention of the Association for Education in Journalism and Mass Communication, Chicago. [ Links ]

Glenn, A. (2013, January 13). Trending in Journalism Education: Online Degrees; Entrepreneurship; Mobile Design. Retrieved from: http://www.pbs.org/mediashift/2013/01/trending-in-journalism-education-online-degrees-entrepreneurship-mobile-design008#sthash.QF0YJL7Y.dpuf [ Links ]

Hunter, A. & Francois N. (2011). Equipping the Entrepreneurial Journalist: An Exercise in Creative Enterprise. Journalism & Mass Communication Educator, 66 (1), 9-24. [ Links ]

Jarvis, J. (2010, January 11). Teaching entrepreneurial journalism [Web log post]. Retrieved from: http://buzzmachine.com/2010/01/11/teaching-entrepreneurial-journalism/ [ Links ]

Lenhoff, A. (2011). The teaching hospital: Possibilities for journalism education. New York, NY: Lap Lambert Publishing. [ Links ]

Lewis, S. (2010, February 1). What is journalism school for? A call for input.Retrieved from: http://www.niemanlab.org/2010/02/what-is-journalism-school-for-a-call-for-input/ [ Links ]

Newton, E. (2012, May 11). Journalism education reform: How far should it go. Retrieved from: http://www.knightfoundation.org/press-room/speech/journalism-education-reform-how-far-should-it-go/ [ Links ]

Nieto, A. (1973). La empresa periodística en España. Pamplona: EUNSA [ Links ]

Nohria, N. (2012). What Business Schools Can Learn from the Medical Profession. Harvard Business Review, 90 (1/2), 38-38. [ Links ]

The Paley Center for Media (Producer). (2010, February 12). Panel: Education of the Entrepreneurial Journalist [Video file]. Retrieved from: http://www.paleycenter.org/carnegie-entepreneurial-journalism/ [ Links ]

Picard, R. (2010, February 2): The biggest mistake of journalism professionalism [Web log post]. Retrieved from: http://themediabusiness.blogspot.com/2010/01/biggest-mistake-of-journalism.html [ Links ]

Notas

1 Please refer to the online survey: http://entrepreneurialjournalismedu.wordpress.com/

2 Please refer to the online survey: http://entrepreneurialjournalismedu.wordpress.com/