Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Acessos

Acessos

Links relacionados

-

Similares em

SciELO

Similares em

SciELO

Compartilhar

Observatorio (OBS*)

versão On-line ISSN 1646-5954

OBS* vol.7 no.4 Lisboa set. 2013

Differentiated strategies for digital innovation on television: Traditional channels vs. new entrants

Heritiana Ranaivoson*, Joëlle Farchy**

* iMinds-SMIT, Vrije Universiteit Brussel, Belgium

** Ecole des Médias, Université Paris 1, Panthéon-Sorbonne, France

ABSTRACT

Digitization has greatly influenced the functioning of the television industry. This paper analyzes in particular how French television channels have innovated and adapted to digital technologies. We begin with a typology of innovation in the media by drawing a distinction between product innovations and process innovations, as well as between companies according to whether they were the first to adopt an innovation, or only adopted it once it was already well established in the field. A total of 21 criteria for innovation are analyzed for each of the 15 TV channels in our sample.

This paper shows that TV channels have varied innovation strategies. Rather than some channels being innovators on all criteria and others being followers on all criteria, we show that channels adopt, more or less rapidly, certain types of innovation according to the channels characteristics. The characteristics that play the greatest role are the age of the channel, whether it is public or private, and whether it is general or thematic.

Keywords: television, digital technologies, innovation, cultural industries.

1. Introduction

Since 1925, when John Logie Baird carried out the first transmission of images, television has created an upheaval in the daily lives of billions of people. Around the world, the broadcasting landscape itself has been radically altered over the past three decades. Once subject to a shortage of broadcasting frequencies, television - as a result of technological changes - has entered a new era of abundance, in which hundreds of channels are now available to the public. In recent years, the digital revolution has greatly accelerated this wealth of content.

In France, channels combine a variety of reception (cable, satellite, DSL, Digital Terrestrial Television, etc.), financing (fees, subscriptions and advertising), programming (thematic, general, etc.) and seniority-based incentive schemes. Well-established channels were jostled by the emergence of the new DTT channels, which became operational on March 31, 2005 and have since gradually become available throughout the entire territory. The last French region switched to digital on 29 November, 2011, relegating analog TV to the archives of memory. DTT offers at least 19 free channels, not including the pay per view channels and subscriptions to cable, satellite or DSL that many homes have. Beyond the multiplying effect of the offer, digital technology has profoundly changed televisions relationship with the viewer, turning the latter into a veritable program director via new services like VOD and catch-up TV.

The aim of this paper is to understand how different television channels adopt digital innovations based on the French case.

Based on an original typology of innovation in the media (Part 2), we constructed indicators of digital innovation for the 15 channels included in our sample. The measuring of innovation through these indicators is based on:

Observation of the channels programs over a period of 7 days (from Monday, December 29 to Sunday, December 5, 2010). This represents 3340 programs for which criteria of innovation relative to content enrichment were applied (see 3.1.1.)

General information, such as the date of adoption of certain innovations by each channel.

The methodology of this measurement is described in detail in Part 3. Differentiated results according to the type of innovation and the channel are provided in Section 4.

2. Innovation in the media: characteristics and typology

2.1 Definition and characteristics of innovation in the media

Innovation, that is to say the use of a new product or production process (Donders et al., 2011; Pavitt, 1984), is a concept that is widely analyzed by management sciences and economics. This also holds true for innovation in media and cultural industries. However, the specific natures of the latter two are not systematically taken into account.

The first essential ingredient of innovation is its novelty (Castañer & Campos, 2002; Schumpeter, 1942). This novelty should also lead to significant amelioration (OECD, 2002). Not all new ideas or prototypes are innovations, however; in the words of Freeman (1991), an invention must be used in order to become an innovation (see also Henten et al., 2004), which means that the idea or prototype must also be developed and marketed.

Secondly, innovations can be categorized depending on whether they are product or process innovations (Cave & Frinking, 2007; Handke, 2008). In the case of the media, product innovation refers both to content and how it is made available to consumers, which are usually designed to change users behavior (Kamprath & Mietzner, 2009), i.e. to ensure that viewers watch more content, or to attract a new audience (Bakhshi & Throsby, 2010). The innovation process meanwhile includes all that is related to content production; while less visible to consumers, it may nonetheless involve major organizational changes.

Beyond this general definition, innovation in the media has specific characteristics (Preston & Cawley, 2004). To begin, most of the activities in this sector are services; the literature, however, is generally oriented towards innovation in products manufacturing (Djellal et al., 2003). Innovation in services is less centralized and less localizable within a company.

Moreover, innovation in the media largely concerns innovation in terms of content, versus innovation in terms of process. It follows that in these sectors, innovation is more likely to be produced by the margin (Flew et al., 2008), including in conjunction with other service activities. In other words, innovation in the media does not necessarily come from big players with large investment capacity, but often newer, more agile players or consortia of firms. Media companies operate in a context of open innovation, where innovation is produced outside of their walls (Chesbrough, 2006). Finally, end users play a considerable role in innovation, as indicated most notably by the development of the concept of 'produser' (Bruns, 2008). Users can have a crucial influence on the conditions that govern the adoption of an innovation, especially when the latter is based on their active participation, as in social networks.

2.2 Product innovation vs. process innovation

This paper posits that innovation in the media is characterized by innovation in content, which is why we take as our starting point the classic distinction between product innovation and process innovation. This comparison is also used as a starting point in research that attempts to quantitatively analyze media innovation (e.g. Donders et al., 2011; Handke, 2008; Stoneman, 2010). We preferred this approach to one that compares incremental innovations (which function by successive improvements) with radical innovations (which consist of a paradigm shift) (e.g. Castañer & Campos, 2002; Köhler, 2005).

Schweitzers (2003) modeling helps in identifying product innovation. A media product consists of three parts, or successive layers: the core, the inner form and the outer form. The core is the basis (in other words the theme or message), while the inner form is the style (for example, the type of film). These two parts represent a media products content. Any innovation relative to this content is what Stoneman (2010) calls "soft innovation." The outer form is the medium that carries the content; it is linked to it, but can also be detached from it (for example, by a change of medium). Thus, in the case of a DVD of the film Titanic, the story of impossible love is the core, the special effects are part of the inner form and the cover of the DVD or Blu-Ray represents the outer form.

Process innovation is modeled by considering that this type of innovation affects one or more steps of the value chain: creation (e.g., a new camera), (re)production (e.g., a new video codec), aggregation (e.g., a new encoding format), distribution (e.g., using Internet protocols to distribute audiovisual content), exposure (e.g., 3D) and consumption (e.g. the possibility of choosing the camera to follow during a sporting event). We include in process innovation all that which relates to the overall process, or more broadly that affects relations between the innovator and other industry players (i.e., through alliances)in other words, innovations on the business model (see most notably Ballon, 2007).

In order to create a complete approach, we combined product and process innovation. The fact that product innovation of the outer form corresponds to process innovation in terms of ways to consume content seems to be an important characteristic of innovation in the media. In fact, the way in which content is accessed is directly tied to the experience the consumer has of this content. In this approach, technological innovation does not stand in contrast to other forms of innovation; on the contrary, digital technologies make it possible to innovate in different ways, but play a role – whether in innovation in business models or in content, as illustrated and developed in the next section).

3. Building of the methodology

3.1 Typology of innovations

This study is based on a sample of 15 of the 19 channels available on DTT at the time of our study. The editorial lines and economic weight of these channels differ greatly. We excluded France O, LCP, Gulli and DirectStar from our sample, the first two due to low viewership in 2010, and the second two because of their specific positions as youth and music channels respectively.

Our sample thus includes public channels like TF1, one of the major broadcasters in Europe, as well as i>TELE, a thematic channel with a much more limited audience. The sample is comprised of both public and private, general-interest and thematic channels that belong to more or less powerful media groups. The way the channels are financed also differs, as does their economic importance and audience ratings (see table below).

Table 1

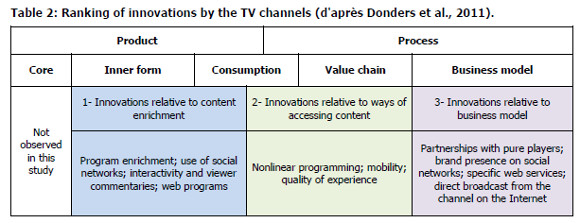

3.2 Typology of innovations

Among the five categories of innovation described in the previous section, those relating to the core of the product are not used here, as it was not possible to identify the impact of digital technology (especially the Internet) on the substance of cultural and media content within the framework of this study. We therefore used only those changes affecting the inner form of the product, how it is consumed, the value chain and the business model, by grouping them into three broad categories: innovations relative to content enrichment, those relative to how content is accessed, and those relating to the business model and strategy development.

This type of innovation is the basis for the construction of innovation indicators. These indicators can be: (1) binary criteria1, (2) dates2 or (3) percentages of programs that have been adapted for innovation.3 Once the indicators are known for each innovation, the channels are then classified according to whether they are precursors, challengers or followers (see 3.3). For binary indicators, we compared precursors (those who have embraced the innovation) and followers (those who have not).

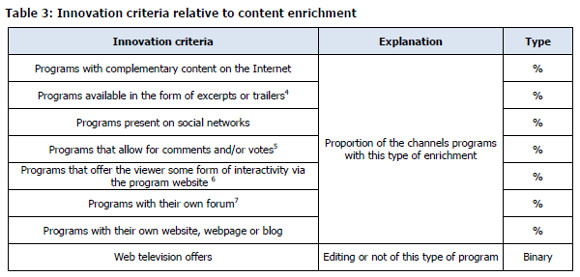

3.2.1 Innovations relative to content enrichment (for inner and consumption)

The first category relates to the inner form of the product, and how the product (programming) is presented to consumers. These innovations aim to enrich content originally produced for television, from the possibility of accessing clips, to the production of programs dedicated to be watched on the Internet. These innovations actually create new content, either via the channels themselves or via users (i.e. comments). They are often important for image. Unlike the first category of innovations, they do not have a direct economic impact, but do tend to act positively on the TV channels reputation by depicting it as younger and closer to its audience.

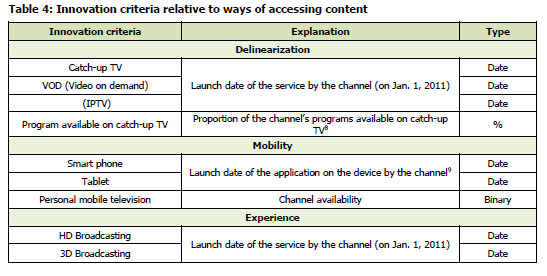

3.2.2 Innovations regarding ways to access content (value chain and consumption)

The second category concerns the means available to consumers to access content (and thus innovations in means of consumption), but also concerns other aspects of the innovation process. Technological development indeed allows TV channels to offer new ways of accessing enhanced, interactive, nonlinear content.

Such innovations allow consumers to choose when (delinearization), where (mobility) and how (changing their experience by increasing the technical quality of content) they watch television programs. These innovations can be seen as economically-driven in the short and medium terms; channels often offer these services to increase viewership (for delinearization), to reach consumers in a context different from that of presence in front of a screen (for mobility) or, on the contrary, to encourage viewers to stay in front of their screens by offering a different experience.

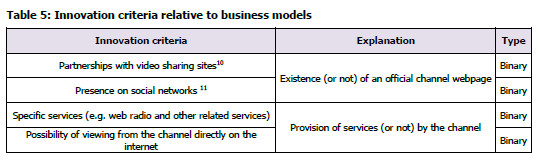

3.2.3 Innovations in business models and strategy development

Finally, the third category includes broader innovations, over and beyond, for instance, the emergence of a new broadcast medium or innovation relative to one of the channels programs. In particular, it concerns partnerships with other economic actors, and/or how viewers access all services (not just television programs).

3.3 Ranking of the channels according to the pace of adoption of innovations

Channels react differently to the emergence of digital innovations, adopting them more of less rapidly, and to a greater or lesser extent. To systematize our classification, we have borrowed the concept funnel of knowledge (Martin, 2009).

Martin distinguishes between different stages in the production or adoption of an innovation. In the first, the innovator (in this case, the channel) is confronted with an innovation that is little or not at all used by its competitors. This innovation can be adopted and adapted to deal with problems (e.g. to reach new viewers) that are, as yet, poorly-defined (e.g. who are these new viewers?). Such innovators are precursors, essentially following their intuition. In the second stage, precursors may clarify their intuition in order to explain the solution they have chosen, but cannot necessarily easily reproduce it (e.g. young people are increasingly interested in Smartphone applications. Some are particularly successful, but it is difficult to know why or how). Other channels also seize innovation; we call them challengers. Finally, the solutions identified to accommodate innovation - i.e. to make it easier to implement them in companies or to reduce production costs - become more easily reproducible not only for the original innovators, but for others as well, like companies that eventually adopt the innovation after the factfollowers.

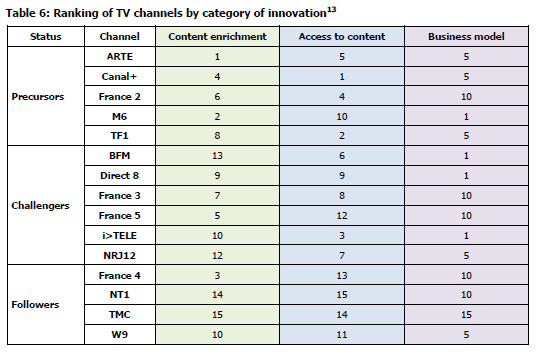

To obtain this ranking, for each chain we added all of the values of the criteria within each category of innovation.12 To do this, we standardized the dates between 0 and 1. The precursor channel thus gets a value of 1; the other channels get a value between 0 and 1 depending on how fast they adopted the innovation relative to the precursor (or 0, if the channel has not adopted the innovation). After adding the criteria, each channel obtained a score by category of innovation. The channels are then ranked for each category.

Finally, the analysis is based on a snapshot at a given point in time, reflecting the varying degrees of innovation of television channels in France in 2010. Some criteria are not subject to change (i.e. the 'date' type, which is linked to when the channel adopted the innovation followed by said criteria). However, most do change. Finally, new indicators may also have been added, following the emergence and/or adoption of innovations (e.g. the use of Instagram, which emerged in 2010).

4. Analysis of the results

The ranking of channels by innovation group gives us the following results (in other words: ARTEis the mostinnovative channelin terms ofcontent enrichment, M6 issecond, France 3 is third, etc.). In terms of content enrichment, we find well-established channels (ARTE, M6, Canal + and France 5) at the top, as well as France 4. At the bottom of the ranking we find TMC, NT1, NRJ12, W9 and news channels. The situation is similar with regard to access to content: heading the list we find the five well-established channels (M6, Arte, Canal +, TF1 and France 2), followed by a new independent channel (Direct 8). At the bottom of the ranking we find TMC, NT1 and W9, accompanied here by France 4 and France 5. In terms of innovations relative to business models, the newer channels (BFM, i>TELE and Direct 8) are particularly innovative. These are followed by NRJ12 and the well-established channels. TMC and NT1 are once again the least innovative channels.

In the end, three main types of channels can be identified based on their performance with regard to digital innovation.

4.1 Innovate or die: the most innovative channels are the historic ones

The leading channels of the major broadcasting groups (TF1, France 2, Canal +, M6 and Arte) are, overall, more innovative than their competitors. These channels have had time to create an identity and brand, and their financial capacities also give them greater flexibility than the younger, more fragile channels. As such, these well-established channels have positions and images to uphold. However, the arrival of new, free channels has undermined their viewership; TF1, the historic leader in French broadcasting, saw its audience share fall from 32.3% in 2005 to 24.5% in 2010.14 Faced with competition from the new DTT channels, illegal downloading, and the announced entry of giants like Apple and Google on the Smart TV market, they strike back using innovation.

Traditional private channels vs. traditional public channels

Public channels have relatively stable budgets that are allocated by the State, mainly through license fees in exchange for quality standards, programming and innovation. We note a marked difference between the strategies of traditional private channels and traditional public channels on two counts: the development of programs on the Internet - where the public channels are clearly ahead - and marketing and development aspects of the brand on the Internet, where private channels appear to be much more aggressive. Public channels are more likely to make a wide range of programming available to viewers on catch-up TV websites, often accompanied by additional content. Such enrichment of programs on the Internet is an added value that is seldom present on the platforms of private channels and well suits the identity and mission of public broadcasting channels. Public broadcasters also have an edge when it comes to the development of audiovisual content specifically for the Internet. Web programs offer their viewers new interactive scriptwriting, turning them into active spectators. ARTE is by and large the precursor in this niche. On the private side, only Canal+ has attempted this. Public channels are generally leaders in terms of community building around programs, i.e. the creation of websites and blogs devoted to the channels programs, although M6 (along with TF1) ranks first in this criterion.

However, TF1 and M6 – the two leading private channels – are on par with and even surpass public channels when it comes to marketing on the Internet. For instance, these channels use voting and commentary devices for three-quarters of the videos they post. Private channels use clips from their programs more for promotional purposes than do public broadcasters. The three main private channels - TF1, M6 and Canal+ - are among the most active on social networks, making use of among others votes, comments, communities, the use of promotional video clips and spaces for specific programs. In general, private channels are more attentive to growing their brands on the Internet (the strategy of France Télévisions is particularly weak on this point). So while TF1, M6 and Canal+ offer web viewers direct access to their channels through their own platforms, public broadcasters have chosen to separate their linear offerings from their nonlinear ones. Hence, although the channels of France Televisions and ARTE are available online via other platforms (PlayTV), the impact in terms of branding is not the same.

The financing structureof the private channels

Beyond the public/private divide, the structure itself of a channels financing impacts its innovation strategy. Financing structure is therefore undoubtedly the source of Canal+s strong performance relative to its competitors, both private and public. With advertising funding representing less than 10% of its turnover, Canal+s primary objective is to build loyalty and increase the size of its subscriber base by remaining at the forefront of innovation. The channel follows a hybrid strategy: its status as a private company makes it is similar to TF1 and M6 on many criteria (brand development and marketing); its financing structure, however, is like that of traditional public channels (relative to content).

Among our sample, Canal+ is the channel that was most responsive to IPTV. The flexibility of use that nonlinear access to content provides is indeed appealing, and follows the same logic as the multiple exposure windows introduced by the group with its different variations (Canal+ Cinema, Canal+ family, etc.). Canal+ has developed a pay catch-up offering (Canal+ on demand), a VOD offering (Canal Play, for subscribers only) and a free catch-up TV interface for its un-encrypted programs. All of these services are a real selling point for customers, who cannot always watch the channel at the hours of their favorite programs. Canal+ thus quickly adopted the catch-up TV option. Moreover, in terms of the density of the offering of nonlinear programs, it approaches the performance of the public channels. As mentioned earlier, Canal+ is also the only private channel to have ventured into the field of web programs. It has also created a web TV channel aimed at street culture, Canal Street a genuine, high-quality, specific offering. Web programs still have a restricted audience, mainly due to a lack of funding. Risk taking, which the production of such programs or development of a web TV channel (niche audience) involves, can explain public channels and Canal+s presence in this segment (importance of the image and the brand).

The impact of editorial policy

The cornerstone of traditional public broadcasting, the cultural channel ARTE, has adopted a particular strategy by extending its objective of disseminating knowledge to include the Internet, hoping in this way to reach an additional audience (most notably, young people who spends less time in front of TV screens). ARTE has been among the most responsive channels in terms of catch-up TV. However, the breadth of its online programming is more limited, as the channel has chosen to select certain programs more suited to this type of distribution. There is a strong desire here to develop a veritable service – to bring together a range of relevant programs and not merely to serve as a catch-up platform for all of the channels programs. Too much exposure can indeed adversely affect the enhancement of stock programs, such as the documentaries that are so plentiful on the channel. ARTE nonetheless makes feature films available online sporadically.

Meanwhile, ARTE is actively developing Internet-only programs. The channel focuses on web series, and has a strategy - like a TV authoring - geared at web authoring.

Audience shares

Beyond the divisions mentioned above, the position of the channels (in terms of audience share) impacts how they innovate. Audience share is more or less directly linked to the channels financial capacity. It also reflects the attractiveness of their programs. Thus, leaders such as TF1 and France 2 stand out from the other traditional channels as regards their nonlinear program offerings. Only these three channels rebroadcast more than 50% of their TV transmissions on the Internet. France 2s catch-up TV website covers the entire spectrum of program genres broadcast on the network, and almost all time slots.

4.2 Survival strategies: innovation relative to specific services

Among the channels with the smallest audience shares, some are dynamic on specific innovation criteria, i.e. France 3, France 5, BFM TV, i>TELE, NRJ12 and Direct 8. These criteria vary from one channel to another, as do the reasons for this dynamism. There are indeed two types of channels, both of which have very different goals: independent general interest channels (NRJ12 and Direct 8) and thematic channels (France 3, France 5, i>TELE and BFMTV).

New general interest channels

NRJ12 and Direct 8 have the distinction of being new, free DTT channels that are not dependent on a large, well-established broadcasting group. They are subsidiaries of media groups (NRJ Group and the Bolloré group respectively), but such groups are not specialized in audiovisual broadcasting and do not have a flagship channel. These two new general interest channels are the most similar to their predecessors in terms of innovation.

These new general interest channels cannot yet afford to build on innovations in content (see below), thus leaving them two fields in which to innovate: support (delinearization, mobility and quality) and brand development (program promotion). NRJ12 and Direct 8 are, for instance, among the first broadcasters to have developed applications for the Ipad tablet, and also chose IPTV very early on. Both are also in a good position to introduce voting and feedback devices for their online videos. Yet, both channels have opted for a different line of innovation.

NRJ12 is among the precursors, if not the leader, on many criteria of innovation. The channel quickly adopted HD broadcasting, and it is also the only channel (along with TF1) that is developing 3D broadcasting. It is likewise active in various forms of media and, as we have seen, is among the first in terms of mobility. Finally, the channel offers a wide variety of nonlinear programs.

For its part, Direct 8 focuses on the development of marketing tools offered by digital technology, both for the promotion of its programs and for the development of its brand. It ranks ahead of NRJ12 as a general interest channel, has its own programs and a more developed identity, and is the channel that is most active in the development of program websites and blogs, with 86% of its programs concerned. However, these types of services, which respond to the information needs of viewers, are less successful here than on traditional channels. Nevertheless, Direct 8 is the only new DTT channel to be successful in this area. Like private well-established channels, it also uses clips from its programs for promotional purposes. Direct 8 is present on social networks, both for its programs and as a media brand, has developed specific services on its website, and provides access to direct broadcasting.

Thematic channels

Thematic channels France 3, France 5, i>TELE and BFM derive their strong performance from their specificity. The two public thematic channels - France 3 and France 5 - benefit from the dynamics of France Télévisions in terms of technical innovation, but have also innovated in specific areas according to their editorial needs.

France 3 - the regional channel - has a naturally close rapport with its viewers a proximity that has led it to develop innovative solutions in terms of program support on the Internet. The channel ranks first in terms of the presence of additional online content. Many of its programs also have special forums or websites. Finally, France 3 is one of the channels with the widest range of programs available on catch-up.

An educational channel, France 5 has adopted a path of innovation similar to that of ARTE, by taking advantage of new broadcasting tools to further it in its mission to disseminate knowledge. France 5 was among the first channels to put its content on the Internet following broadcast. It has also developed a relatively large program offering specifically for this media. While ARTE focuses on web series, France 5 gives priority to web documentaries, and is active in terms of interactivity and community building around its programs. Again, it is similar to ARTE in this area, as both channels share the desire to interact with viewers. Despite these similarities, France 5 proves less innovative than ARTE on most criteria. Unlike France 5, ARTE is not dependent on the overall strategy of a channel group and, more importantly, has a much larger annual budget than does France 5.

Continuous news channels as information sources are in direct competition with other media, such as the press, radio and, of course, websites. To weather this competition, they must be innovative on specific criteria, such as access to programs.

Mobility is thus crucial for news channels. i>TELE is, moreover, one of the first channels to have developed an iPhone application. BMFTV and i>TELE were responsive in dealing with tablets and were among the first to have developed specific applications. They have also developed veritable information platforms on the Internet, rebroadcasting the networks productions and adding specific services such as web radio (for i>TELE) and direct access to the channel. In terms of percentages of programs available on catch-up, news channels topped the list (for duration), rebroadcasting all of the stories originally produced for the network on the Internet, in keeping with their logic of disseminating multi-media (TV-radio-internet) information.

The immediacy of news, along with the ephemeral nature of news reports, pushes broadcasters to diffuse information as quickly as possible in order to make it as profitable as possible. The logic of flow programs comes fully into play here.

i>TELE TV allows viewers to comment and vote on the videos it posts. Exchanges with viewers go even further, with forms of interactivity via web features. This tool is widely used by these channels on the lookout for news and exclusive material. They are also all particularly attentive to the visibility of their brands on the Internet, especially via social networks and partnerships with pure player platforms.

4.3 Strengthening the core business rather than innovating

A third group of channels distinguishes itself; it consists of the "little sisters" of well-established channels. Thus, W9 of the M6 group, France 4 of France Télévisions, TMC and NT1 of the TF1 group, overall show little innovativeness. These channels focus on their first line of business as TV broadcasters and play a complementary role to their network by attracting a specific audience and additional revenue, but are not yet strong enough to attract particular attention from their groups for innovation.

In large part operational thanks to the recycling of programs from traditional channels due to their low budgets, these new channels have few programs of their own. What is more, programs broadcast on these channels tend to attract a small audience. At the time of this study, viewership rarely exceeded a million, and this large a number often thanks to motion picture films, the negotiation of rights for which makes broadcast on catch-up TV complex. So, unlike traditional channels, their programs are not strong enough to warrant any special effort in terms of their development on the Internet. However, this status does not stop them from benefitting from the innovations developed by their parent companies in other areas after the fact. The group effect here fully plays on differences in the behavior of the channels, starting with the distinction between private groups and public service.

France 4, the public channel

France 4 differs from other channels in this category in terms of the relative speed with which it adopts new technologies. It entered the field of VOD, IPTV and mobility (iPhone application) at the same time as the traditional channels of the group. The holding company France Télévisions favors the development of the group brand, emphasizing the complementarity of the channels as each being a part of a whole. France Télévisions group vision distinguishes it from private groups, which place greater emphasis on the individual channels. Like its elders, France 4 showcased its programs on the Internet by offering viewers additional content and developing communities. The channel is the only one (among the new entrants) to offer web programs on its website.

The new private channels

The behavior of these private channels vis-à-vis digital technology is also impacted by the strategies of the broadcasting groups to which they belong. Thus, although overall NT1, TMC and W9 are lagging behind, W9 (part of the M6 group) stands out among its competitors from the TF1 group.

Although their audiences are comparable, the strategies of W9 and TMC diverge. In general, the M6 group takes greater advantage of the opportunities offered by digital technology for its new free channel (W9). Like M6, W9 has chosen to develop additional online content to enrich the networks programs. The broadcaster is also active as regards interactivity and communities, just like the groups flagship channel. Like France Télévisions, there is a uniformity of channels Internet devices. Up until now, the logic was not the creation of a common platform for catch-up TV, but the W9 platform uses ergonomics similar to those of M6. This integration is not as present within the TF1 group.

TMC is more innovative than NT1. Its relative audience success encourages it to delinearize, offering its flagship programs an additional window of exposure. The channel broadcasts 37% of its airplay on catch-up TV and thus ranks first among the new DTT channels (excluding news channels) on this criterion.

5. Conclusion

Despite the numerous studies on innovation, including in cultural industries, few have attempted to provide objective indicators that make it possible to quantify innovation, in particular with the objective comparing of the strategies of different actors. From this point of view, this paper is an exploratory analysis applied to the case of the French television channels, with a focus on innovations resulting from the development of digital technologies.

To accomplish this, the paper uses a typology of innovations that contrast product innovations and process innovations, the specificity of the media being the significance of the junction between these two types of innovation a junction that includes all of the means by which consumers can access content. From this typology, 21 criteria of innovation were built, and the corresponding indicators were measured for each of the 15 channels in our sample and the programs in question (more than 3000 in total).

This methodology allowed us to objectify the analysis between traditional channels (which are more prone to innovation and act as precursors, especially with respect to programming) and new general interest channels (owned by large broadcasting groups that play the role of followers in terms of innovation). While "showcase" channels of large traditional broadcasting groups are in advance in terms of program enrichment and access to content (TF1, France 2, Canal +, M6 and ARTE), the latter, generally speaking, are not very innovative (W9, TMC and NT1 France 4).

In addition, this typology allows us to go beyond the precursor vs. follower dichotomy because of the level of detail for indicators of innovation. More specifically, a third group of channels stands out. These channels, which are neither always among the most innovative nor consistently among the followers, are highly innovative in a specific area and have more of a wait-and-see attitude. Their common characteristic, however, is the obligation to innovate on certain points, despite tight budgets, in order to survive. These challengers are independent channels and/or thematic channels that distinguish themselves based on specific innovations (Direct8, NRJ12, France 3, France 5, BFM and i>TELE).

This research is only the first step in understanding how digital technologies are changing the innovation strategies of cultural industries, and merits a more detailed and thorough analysis. A first avenue of approach would be to analyze how innovation is internally driven, and what are the internal processes that have led to the current situation (in particular the choices made in terms of innovation to favour). Another approach would be to adapt and apply these indicators to other cultural industries, such as music or movies, bearing in mind that the innovation touted in managerial discourses - like those of policy makers - needs to be quantified and evaluated in order to gain depth and objectivity.

Bibliography

Bakhshi, H., & Throsby, D. (2010). Culture of Innovation. An economic analysis of innovation in arts and cultural organisations: NESTA. [ Links ]

Ballon, P. (2007). Business modelling revisited: the configuration of control and value. Info: The journal of policy, regulation and strategy for telecommunications, information and media, 9(5), 14. [ Links ]

Bruns, A. (2008). Blogs, Wikipedia, Second life, and Beyond : from production to produsage. New York: Peter Lang. [ Links ]

Castañer, X., & Campos, L. (2002). The Determinants of Artistic Innovation: Bringing in the Role of Organizations. Journal of Cultural Economics, 26(1), 29-52. [ Links ]

Cave, J., & Frinking, E. (2007). Public Procurement for R&D. University of Warwick. [ Links ]

Chesbrough, H. W. (2006). Open business models : how to thrive in the new innovation landscape. Boston, Mass.: Harvard Business School Press. [ Links ]

Djellal, F., Francoz, D., Gallouj, C., Gallouj, F. z., & Jacquin, Y. (2003). Revising the definition of research and development in the light of the specificities of services. Science and Public Policy, 30, 415-429. [ Links ]

Donders, K., Ballon, P., Ranaivoson, H., Lindmark, S., Evens, T., Rucic, H., et al. (2011). Naar een Ecosysteem-Model voor Onderzoek en Innovatie rond Audiovisuele Consumptie in Vlaanderen. Deliverable 2. Desirable and feasible scenarios for collaborative innovation in the Flemish media sector. Brussel / Gent: IBBT-SMIT, VUB / MICT, UGent. [ Links ]

Flew, T., Cunningham, S. D., Bruns, A., & Wilson, J. A. (2008). Social Innovation, User-Created Content and the Future of the ABC and SBS as Public Service Media : Submission to Review of National Broadcasting (ABC and SBS), Department of Broadband, Communications and the Digital Economy. [ Links ]

Freeman, C. (1991). Innovation The New Palgrave: A Dictionnary of Economics (pp. 3). London: The Macmillan Press Limited. [ Links ]

Handke, C. (2008). On Peculiarities of Innovation in Cultural Industries. Paper presented at the 15th International Conference of the Association for Cultural Economics International (ACEI). [ Links ]

Henten, A., Falch, M., & Tadayoni, R. (2004). New Trends in Telecommunication Innovation. Communications & Stratégies, 54(2nd quarter), 131-158. [ Links ]

Kamprath, M., & Mietzner, D. (2009). The Nature of Radical Media Innovation - Insights from an Explorative Study. Paper presented at the 2nd ISPIM Innovation Symposium - "Stimulating Recovery - The Role of Innovation Management". [ Links ]

Köhler, L. (2005). Produktinnovation in der Medienindustrie. Organisationskonzepte auf der Basis von Produktplattformen: DUV Gabler Edition Wissenschaft. [ Links ]

OECD (2002). Frascati manual 2002 : proposed standard practice for surveys on research and experimental development : the measurement of scientific and technological activities. Paris: Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. [ Links ]

Pavitt, K. (1984). Sectoral patterns of technical change: Towards a taxonomy and a theory. Research Policy, 13(6), 343-373. [ Links ]

Preston, P., & Cawley, A. (2004). Understanding the 'Knowledge Economy' in the early 21st century: Lessons from Innovation in the Media Sector. Communications & Stratégies, 55(3rd quarter), 26. [ Links ]

Schumpeter, J. A. (1942). Capitalism, socialism, and democracy. New York, London,: Harper & Brothers. [ Links ]

Schweizer, T. S. (2003). Managing Interactions between Technological and Stylistic Innovation in the Media Industries. Technology Analysis & Strategic Management, 15, 23. [ Links ]

Stoneman, P. (2010). Soft innovation : economics, product aesthetics, and the creative industries. Oxford ; New York: Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

Notes

1 i.e. Has the innovation been adopted or not? The difference between precursors (those who have adopted innovation) and followers (those who have not).

2 i.e. when was the innovation adopted? The first channels to have adopted innovation are precursors, the ones after are intermediates and the last (including those that have not adopted the innovation) are followers.

3 i.e. to what extent has the innovation been adopted by the channel? Channels with the highest percentage of programs for which the innovation has been adapted are the precursors, those who follow in terms of percentage are intermediaries, and those with the lowest percentage are followers.

4 On the channel website in catch-up or, when it exists, on the program website.

5 On the channel website in catch-up or, when it exists, on the program website.

6 Devices that allow viewers to act on the programs (i.e. ask questions directly or post videos that can then be reused).

7 On the channel website in catch-up or, when it exists, on the program website.

8 Calculation based on the hourly volume (and not the number of programs). For news channels, we observed online journals and not TV newscasts per se.

9 The iPhone and iPad were respectively chosen for the categories of smart phone and touch tablet.

10 Dailymotion or Youtube.

11 Facebook pages or Twitter accounts.

12 Results available in the appendix.

13 More detailed results in Appendix.

14 Audience share of a population age 4 years and over. Source: Médiamétrie.

Annexes

Anexo 1