Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Acessos

Acessos

Links relacionados

-

Similares em

SciELO

Similares em

SciELO

Compartilhar

Observatorio (OBS*)

versão On-line ISSN 1646-5954

OBS* vol.7 no.4 Lisboa set. 2013

From Broadsheet to Tabloid: Content changes in Swedish newspapers in the light of a shrunken size

Ulrika Andersson*

*University of Gothenburg, Sweden

ABSTRACT

During the early 2000s, the newspaper market in Northern Europe was characterised by a trend of format changes as many broadsheets have chosen to adapt to the tabloid format. Similar tendencies also have emerged in other Western countries, making it a transnational phenomenon. Critics have argued that a reduced size impacts the content, resulting in increased tabloidisation, finding a connection between the page size and the news content whereby the broadsheet and tabloid formats require different kinds of journalism. Thus, this study aims to analyse whether it is possible to detect this type of increased tabloidisation in relation to the resizing of newspapers. Using the theoretical concept of tabloidisation, this study begins with a content analysis of Swedish dailies that have changed their format during the early 2000s. Comparisons are made to newspapers that did not undergo this type of transition as means of determining whether any of the changes detected can be explained by the actual format change, or rather, are the effects of other factors. The study focuses on news content published in 1990, 2000, and 2010. It reveals that the format itself has had only a minor influence on journalism, in that all newspapers show similar signs of increased tabloidisation during this period.

Keywords: broadsheets, journalism, tabloids, tabloid transition,tabloidisation

Introduction

The tabloid has conquered the newspaper business (SvD, 2004). Those were the words of the Swedish quality paper Svenska Dagbladet (SvD) in early October 2004. The article was written due to the transition of several large morning papers from the broadsheet to the tabloid format. During two weeks in October, more than 800,000 Swedish readers and subscribers found their local newspaper to have shrunk to about half of its original size in one day.

A common argument used to justify the resizing of daily newspapers was that the tabloid format represented a modern and reader-friendly product (Melesko, 2006; Newsbound, 2010; Sternvik, 2007a, 2007b). The tabloid format, however, was not a new phenomenon in the industry. The actual breaking point during which the vast majority of all Swedish dailies were printed in tabloid size took place as early as the mid-1980s, due to the choice of many smaller newspapers to adopt the tabloid format. But, it was not until the 2000s that the tabloid became the common standard in the industry due to the decision of a great number of large newspapers to adopt the compact format (Sternvik, 2007a, 2007b).

The trend towards a shrinking size has by no means been unique to Sweden, although a handful of Swedish newspapers, along with their Norwegian counterparts, have been described as role models in the worldwide trend toward a compact format that has taken place in the printed news media (Newsbound, 2010; Sternvik, 2007b). Other important actors were the Times and the Independent, two British quality papers that drew international attention to the trend toward a compact format as they went tabloid in 2003. Their transition was regarded as somewhat sensational as the tabloid format has long had a strong association with the low quality press in the UK (Franklin, 2008; McMullan & Wilkingson, 2004). Thus, the term compact has commonly been used by British owners and editors as a way of avoiding the anticipated opprobrium associated with the tabloid concept (Franklin, 2008). Other countries characterised by shrinking newspapers are Austria, France, the French-speaking parts of Belgium and Switzerland (McMullan & Wilkingson, 2004), Canada (Brin & Drolet, 2008), and Australia (Sydney Morning Herald, 2013; Rowe, 2011). In Northern Europe, the trend spread to Denmark during the mid-2000s (Sternvik, 2007b) and to Finland during the early 2010s (Medievärlden, 2012).

The transition of quality papers to a more compact format has led to discussions about the real effects of a shrunken size on journalism. When the Times and the Independent chose to adopt the tabloid format, fears arose that their original quality journalism would degenerate into journalism more similar to that of the tabloid press (cf. Bird, 2009; Franklin, 2008; Gans, 2009). From this point of view, the format transition of quality newspapers was believed to increase the level of tabloidisation in terms of less focus on hard news and greater focus on soft news, pictures, illustrations, graphics, and large headlines. Other voices, however, have argued that editors at newspapers whose formats have been changed have paid too little attention to adjusting their papers content to the tabloid size; consequently, broadsheet content has been forced harshly into a tabloid mold, making their newspapers outdated and less reader-friendly (Botero de Leyva, 2004; Erbsen, Giner, & Torres, 2007; Giner, 2004). From this point of view, the modern newspaper not only needs a fresh outer shape, but also, upgraded journalism. Regardless of ones opinion, these arguments clearly demonstrate a general belief that the size of a newspaper is strongly linked to its journalism: Thus, the broadsheet is perceived to demand a certain kind of journalism, while the tabloid format is believed to demand another kind of journalism.

The connection between page size and content will, therefore, be the focus in this paper as it aims to analyse whether it is possible to detect increased tabloidisation in relation to the resizing of quality newspapers. The focus is on five Swedish daily newspapers that have changed from the broadsheet to the tabloid format during the early 2000s. A comparison will be made with the only remaining major high-frequency newspaper that continues to be printed in broadsheet. This comparison is done as a means of determining whether the measured changes are the effect of the format transition itself, or rather, the effect of other factors. Using the concept of tabloidisation, the focus is on changes in form, range, and style. Those elements are measured by a quantitative content analysis of the newspapers´ appearance before and after the format transition. The focus is on news content published in March 1990, 2000, and 2010. By pinpointing this issue, it is possible to determine the real role the size of a newspaper has on its content.

Going tabloid: three phases of transition in Sweden

The process towards establishing the tabloid as the industry standard in Sweden has been characterised by three rather distinct phases. The starting point of the first phase was in the 1950s and 1960s when many low-frequency newspapers (published once or twice a week) chose to embrace the tabloid format. Research has shown that new technology and decreasing readership were important factors to explain the appearance of this first tabloid phase. However, the most important factor was the fact that many newspapers suffered from lack of editorial content and advertisements: There simply was not enough content to fill a broadsheet (Sternvik, 2007a, pp. 85-87).

The second tabloidisation phase took place in the 1970s and 1980s and was dominated by changes in high-frequency newspapers (published at least five days a week) that were competing against a larger newspaper in the same local market. The choice of the tabloid format resulted in a competitive advantage as it turned out to be a favourable differentiation from the major newspaper (Sternvik, 2007a, p. 93; cf. Porter, 1983, pp. 56-58). Former ideological and practical barriers to the introduction of the tabloid format were steadily eliminated during this period as internal as well as external actors gradually changed their opinions about the tabloid size. Important factors explaining this change of mind were technological developments, as aging printing presses needed to be replaced, and economic considerations, in terms of increased competition and declining readership (Sternvik, 2007b, p. 13). Thus, adopting a smaller page size appeared to be a potential solution to some of these problems.

The third, and so far, the last, phase began in the early 2000s when most major newspapers chose to adopt the tabloid format. This phase has been subject to analyses with a focus on several factors, including economic considerations, editorial processes, and readers (Halonen, 2004; Melesko, 2006; Stenberg & Wiberg, 2004; Sternvik, 2007a). In November 2000, Svenska Dagbladet (SvD), one of Swedens top selling morning papers, switched from broadsheet to tabloid, a move that frequently has been described as the trigger for the third tabloid phase (Sternvik, 2007b, p. 13).

Most daily quality papers that followed SvDs track expressed clear policies that their papers should continue to publish similar amounts of editorial content following the format transition (Melesko, 2006, p. 125). However, new editorial guidelines were developed simultaneously, stating that all articles needed to be kept shorter in order to accommodate the new page size (Sternvik, 2007a, p. 142). Studies have shown that journalists and editors perceived news work as becoming even more routinised as articles and page spreads were controlled by tighter reins in the tabloid format (Andersson, 2013). A brief content analysis conducted soon after the format transition of a handful of morning papers showed a shift in the distribution between editorial content and advertising content (Sternvik, 2007a, pp. 142-144, 149-151). A similar tendency also has been found in German morning papers that have adopted the tabloid format (von Bucher & Schumacher, 2007, pp. 515-517), suggesting that this kind of shift may be a common consequence of a smaller size despite a newspaper´s ambition to keep its distribution intact.

Reader preferences have been one main reason why many major Swedish morning papers chose to adopt the tabloid format during the early 2000s, at least according to most editors-in-chief (Sternvik, 2007a, p. 103). But, scholars have shown that fierce competition and economic considerations are other central factors that have affected many newspapers in this matter (Melesko, 2006; Sternvik, 2007a, pp. 108-110). Most newspapers had been confronted with falling readership and shrinking advertising markets during the 1990s, and thus, the tabloid format seemed to offer significant advantages compared to the broadsheet: It was not only more reader-friendly, it also produced long-term financial benefits for the publisher as it was cheaper and easier to edit and print. Further, it simplified the cooperative advertising process when all newspapers involved were printed in the same format (Sternvik, 2005, 2007b).

While most newspapers went tabloid on more or less optimal bases, some felt obligated or perhaps even forced to adopt the tabloid format because of increased demands from advertisers, readers, or other newspapers (Sternvik, 2007a, pp. 108-110). Thus, the shift towards the tabloid format as the industry standard has become a somewhat overriding factor for most newspapers, although there still were about ten morning papers (high-frequency as well as low-frequency) printed in broadsheet format in the early 2010s. The vast majority of all newspapers, however, more than 90 %, are edited and printed as tabloids in 2013. The question in focus, therefore, is how this format transition has come to affect the process of tabloidisation among newspapers that took part in the third tabloid phase.

The concept of tabloidisation

From a historic point of view, the tabloid concept was first introduced into the media business as a description of a certain kind of compact newspaper appearing in the early 20th century (Fang, 1997, p. 108). Those papers most often reach a wide audience and thus, are strongly focused on pictures, sensations, entertainment, and amusements. This so-called tabloid journalism often has been perceived as less worthy by professionals and scholars, in its early days as well as in recent years (Langer, 1998, pp. 8-9; Örnebring & Jönsson, 2004, p. 284; Sparks, 2000). Its counterpart has, by tradition, been found in quality papers – broadsheets – that from a normative perspective have strived to offer the audience serious, responsible, and quality journalism (Connell, 1998; Langer, 1998, pp. 8-9; Örnebring & Jönsson, 2004, p. 284; Sparks, 2000). The broadsheet historically has not only been associated with a size twice as large as the tabloid, it also has connoted an intellectual and substantial content with a greater focus on hard news. Clearly, the close connection between page size and journalistic content has deeper roots than merely being a part of the discussion related to format transition that took place in the early 2000s.

Changes in the media ecosystem in past decades have led to the renegotiation of the tabloid concept as quality papers worldwide have claimed that the tabloid is a contemporary and modern format, suitable for serious and responsible news journalism. Tabloid journalism is, however, still somewhat tainted and this is particularly evident in the context of tabloidisation. Tabloidisation primarily has been used to describe a process whereby the news media shifts towards an increase in audience orientation and commercialisation; further, it is most often equated with low quality journalism, i.e., tabloid journalism, and it has been described as a transition whereby the news media increases its focus on sensationalism, scandals, and infotainment. (e.g., Esser, 1999; Franklin, 2008; Örnebring & Jönsson, 2004; Papathanassopoulos, 2001; Plasser, 2005; Reinemann, Stanyer, Scherr, & Legnante, 2012; Sparks, 2000). In this process, hard news such as politics and economics often are given less space as media professionals´ perceptions of what the citizenry needs is broadened. Thus, the discussion and concerns associated with the tabloidisation of journalism are about the gradual influence of values associated with tabloids and tabloid journalism on the qualitative news media. This process often is described as a potential threat to a democratic society because it lowers journalistic standards (Franklin, 2008, 1997; Örnebring & Jönsson, 2004; Sparks, 2000).

Researchers often explain changes of this kind as the increased influence of commercial factors and the desire of media firms to adapt to these factors. The increased willingness of the media to adjust to and address the audience is one frequently mentioned factor; others are the increased competition resulting from new technology, as well as increased demands for profitability (Bek, 2004, p. 376; Esser, 1999; Picard, 2005; Sparks, 2000, pp. 3-4). From this perspective, tabloidisation is strongly connected to the social context as changes in society are believed to have a powerful influence on how the news medias form and content develops over time. Given that society has long been characterised by increased commercialisation, it is expected that at least some traces of tabloidisation in news journalism will be found as the media, an integral part of society, is affected by changes and processes that occur locally as well as globally (cf. Harrington, 2008; McChesney & Nichols, 2010). Following this line, the transition from the broadsheet to the tabloid format may very well be described as a kind of tabloidisation as it has been a part of newspapers´ adaptation to the current economy, industry-wide cooperation, technological developments, and increased audience demands. This also is how some researchers recently have chosen to use the concept (cf. Bird, 2009; Franklin, 2008; Gans, 2009). Tabloidisation may therefore describe changes in content as well as a newspapers outer form, although the focal point in this study is changes in content.

Most scholars adopt a critical perspective when discussing the content changes associated with tabloidisation; the process is commonly believed to decrease the quality of journalism (Esser, 1999; Örnebring & Jönsson, 2004; Sparks, 2000). In trying to determine what this content discussion is really about, Collin Sparks (2000) distinguishes three main tendencies in the use of the tabloidisation concept: Firstly, news media that undergoes a tabloidisation process devotes less attention to issues such as politics, economics, and social issues (hard news); instead, an increased focus is put on sports, scandals, and entertainment (soft news). Also, greater importance is put on peoples personal and private lives rather than on political processes, economic developments, and social changes; secondly, editorial priorities are restructured so that news and information is less prioritised while entertainment is highlighted to a greater extent; thirdly, the populist tone of reporting on political issues is increasing (Sparks, 2000, pp. 3, 10-11).

Despite scholarly efforts to clarify what tabloidisation is really about, there is a certain variety in the dimensions attributed to this process. The distribution of hard versus soft news and public life versus private life mentioned above are regarded as important features by some researchers (e.g., Balcytiene, 2009; Franklin, 1997, 2008; Örnebring & Jönsson, 2004; Plasser, 2005; Reinemann et al., 2012; Sparks, 2000). Other concepts used to describe these dimensions have been range (McLachlan & Golding, 2000; Porto, 2007; Rooney, 2000; Uribe & Gunter, 2004), theme (Bek, 2004), and trivialisation (Djupsund & Carlsson, 1998). Also, the concept of style, sometimes described as mode of address, has been used to analyse the degree of conflict orientation (Bek, 2004; Esser, 1999) as well as personalisation in news content (van Aelst et. al., 2012; Balcytiene, 2009; Esser, 1999; McLachlan & Golding, 2000; Plasser, 2005; Uribe & Gunter, 2004). Common to all these key concepts is their focus on the written or spoken word.

Another dimension commonly mentioned in current research is form. Here, form refers to the use of illustrations, simplified language, and the size of headlines (McLachlan & Golding, 2000; Uribe & Gunter, 2004). Sometimes, visualisation is used to describe this dimension (Djupsund & Carlsson, 1998; Machin & Niblock, 2008; Papathanassopoulos, 2001). Form as an expression of tabloidisation must be considered highly important as the increase in the use of visual elements usually means fewer written words. If news reporting shifts towards a decrease in range, in terms of fewer pieces on politics, economics, and social issues, and headlines and images simultaneously are given increased space, these changes are more likely to impact the overall quality of newspapers.

Form as a dimension is perhaps most clearly linked to the question of whether going tabloid really pushes journalism towards increased tabloidisation. The transition from the broadsheet to the tabloid format unavoidably has a compelling influence on the actual page structure: Broadsheets are commonly edited page by page, while tabloids are edited spread-wise. In practice, this means that broadsheets have a vertical page structure wherein articles are elongated in height, while tabloids have a certain horizontal structure wherein articles are drawn out lengthwise. Shrinking the outer form of a newspaper into half of its original size is therefore likely to affect the relationship between the internal components of an article such as headline, illustrations, and text. Consequently, some layout changes should be expected in the forthcoming analysis. The extent of these changes is central in this study because major changes are assumed to indicate an increased tabloidisation derived from the transition to the tabloid format.

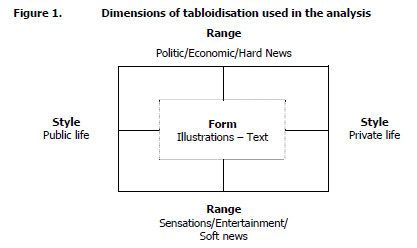

Aiming to analyse whether it is possible to detect an increased tabloidisation in relation to the resizing of newspapers, this study focuses on three dimensions related to tabloidisation: form, range, and style (see Figure 1). The form of news coverage deals with article size, headline size, and the presence of visual elements such as pictures and other kinds of illustrations. By focusing these factors, the study will provide an understanding of the kind of impact the transition from broadsheet to tabloid has had on the overall structure of news articles. This dimension reveals whether visual elements have increased at the expense of written words (cf. Machin & Niblock, 2008).

Range, in turn, focuses on the news items reported in the coverage and aims to detect whether news reporting has become more limited as well as whether the focus on so-called hard news has decreased in favour of soft news (cf. Uribe & Gunther, 2004). There are certainly no common rules or guidelines regarding how to make the distinction between hard and soft news (Boczkowski, 2009; Reinemann et. al., 2012). In this study, hard news is defined as reports about politics, public administration, the economy, science, technology, social issues, and related topics. Soft news is defined as reports about celebrities, human interest, sports and other entertainment-centred stories. Reports on accidents and crimes are sometimes difficult to define either as hard or soft news (see Curran, Salovaara-Moring, Cohen, & Iyengar, 2010; Reinemann et. al., 2012) and are therefore treated as a separate category in the analysis.

Finally, style is used to measure the focus on public life versus private life (cf. van Aelst et. al., 2012; Uribe & Gunther, 2004), i.e., whether news articles include more emphasis on the private lives of public persons and on individuals rather than public persons in public life. This dimension commonly is used in analyses of political reporting, in which it measures the shift in media focus from politicians as occupiers of public roles to politicians as private individuals, but it also should be regarded as a fruitful approach when analysing wider news reports.

Research design

This study is based on a quantitative content analysis of the news coverage of seven daily newspapers in Sweden during the period from 1990 to 2010. Every sixth edition in March 1990, 2000, and 2010 has been coded, starting with March 1st. In all, March 1st, 6th, 11th, 16th, 21st, 26th and 31st have been included in the analysis; altogether, these days comprise an average week, from Monday to Sunday. Spreading the coded material this way is a deliberate choice designed to prevent specific events from having too much impact on the results.

The news coverage that is the focus of the study consists of the local, regional, national, and international reporting in these seven newspapers. As the analysis will focus solely on traditional news sections, other sections such as sports, culture, family, and opinions, have been excluded from the study. This delimitation is made with reference to the function of the news media in a democracy, in which providing information and scrutinising those in power is considered important (cf. Kovach & Rosenstiehl, 2007). It is therefore important to analyse the kind of impact the tabloid transition of the past decade really has had on news coverage. Also, given that the theoretical concept of tabloidisation – on which this study´s operational indicators rely – is based on certain changes in news coverage, it appears most fruitful to focus on this kind of content.

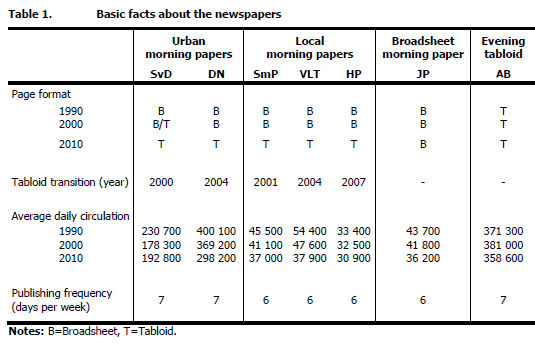

The seven daily newspapers in focus have been divided into four groups depending upon their characteristics. Two of these groups, urban morning papers and local morning papers, consist of newspapers that have changed from broadsheet to tabloid during the period from 2001 to 2007. Svenska Dagbladet (SvD) and Dagens Nyheter (DN) are part of the first group, while Smålandsposten (SmP), VLT, and Hallandsposten (HP) are part of the latter group (see Table 1). In addition, two other newspapers serve as references because they are dailies that have not reduced their page size during the period in focus. The first one is Jönköpings-Posten (JP), the only major Swedish morning paper that has chosen to preserve the broadsheet format. This newspaper will be named broadsheet morning paper in the forthcoming analyses. The second paper is Aftonbladet (AB), an evening tabloid that has long been edited in the tabloid format. This latter paper should perhaps be described as the only real tabloid of the newspapers compared, at least given the original meaning of the tabloid concept.

The broadsheet morning paper and the evening tabloid are included to determine whether detected changes found in the newspapers with a format change should be regarded as a consequence of the format change itself, or rather, a change that is common to the business as such. Comparisons with the evening tabloid also will reveal whether quality papers have become more similar to the tabloid press as a result of the tabloid transition. If all seven newspapers appear to have developed in a similar direction during the period between 1990 and 2010, this probably means the format – the actual page size – has no consequence for the news content. Further, the inclusion of an evening tabloid is motivated by the results of prior studies of British newspapers, which have indicated the presence of an ongoing convergence wherein broadsheets and tabloids are slowly shifting toward similar content (Uribe & Gunter, 2004, p. 400; see also Franklin, 1997, p. 7; McLachlan & Golding, 2000; Rooney, 2000).

As for the content analysis, all form variables have been coded by counting frequencies (e.g., number of articles and illustrations) or measuring size in square centimetres (e.g., size of articles and illustrations). In addition, all range and style variables have been coded according to a principle of main representation, which means that the subject or style given the largest space in the article also represents the full article. Measurements used in the forthcoming analysis are based on frequencies, percentages, and bivariate correlations (Kendall´s Tau-c). Kendall´s Tau rank correlation coefficient is a non-parametric test that measures the association between two variables. The coefficient varies between -1 to +1 where -1 equals a perfect negative correlation (i.e., high values on variable X corresponds to low values on variable Y) and +1 equals a perfect positive correlation (i.e., high values on variable X corresponds to high values on variable Y).

Results

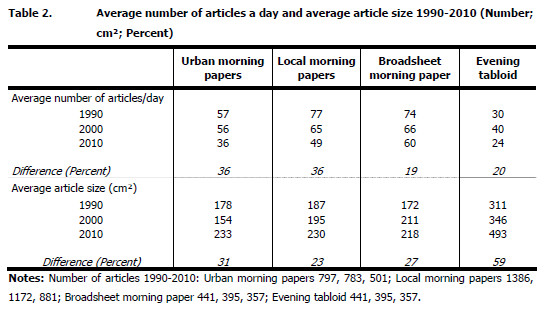

There is no doubt that the process of going tabloid has resulted in consequences for the analysed newspapers to some extent. The most apparent are the changes in the page structure as the tabloids are edited spread-wise, and thus, have more of a horizontal layout structure. But, reducing the paper into half of its original size also has led to changes in the number of articles published, as well as changes in the average article size. The number of articles published a typical day in urban and local morning papers has decreased by one-third during the years between 2000 and 2010. In addition, the average article size has increased by approximately one-fourth during the same period (Table 2). These changes are mainly found in the distribution of small, mid-size, and large articles, where the latter have increased both in number and size, while the quantity of mid-size articles has clearly decreased following the tabloid transition.

The results further reveal that these changes are not unique to format swapping newspapers; instead, it appears to be a trend common to the business itself, as the referenced papers – the broadsheet morning paper and the evening tabloid – also show similar tendencies to some extent (Table 2). As for the broadsheet paper, the decrease in the number of articles and increase in the article size seem to have happened primarily between 1990 and 2000. Yet, the overall situation reveals that the business as a whole has developed in a similar direction, although the tabloid shift clearly has helped to speed up these changes. This means that readers are generally presented primarily with small and large articles. They also face decreased news reporting as the number of entrances has declined.

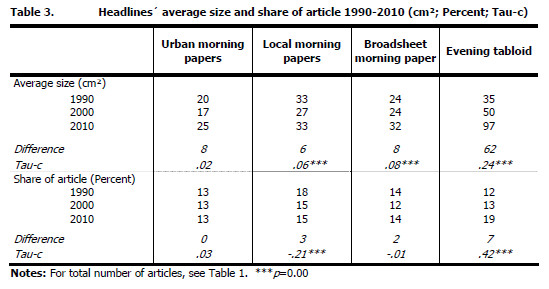

Focusing on the overall structure of news articles, there is a tendency for newspapers to include fewer written words and more reader input, such as larger headlines and more pictures and other illustrations, into articles. Regarding headlines, the average size increased during the first decade of the 2000s (Table 3). A similar tendency is not seen, however, when looking at the headline´s share of the article: With an exception for the evening tabloid, in which the headline´s portion of the article has increased over time, there are only small or no changes found among morning papers. For urban morning papers and the broadsheet morning paper, the increase in the size of headlines corresponds to a similar increase in the article size. Again, the changes found among these newspapers appear to be of a more general nature.

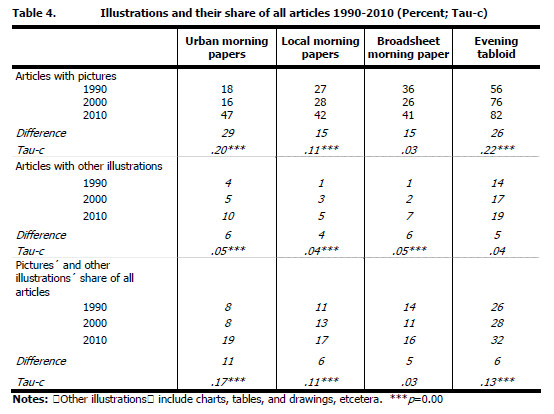

The situation is somewhat different when it comes to the presence of different kinds of illustrations. The illustrations as such have been divided into two groups in the analysis: 1) pictures; and, 2) other illustrations, for example, charts, tables, and drawings. The results reveal that articles with pictures have almost doubled for those newspapers that went tabloid during the early 2000s (Table 4). In 1990 and 2000, urban morning papers published pictures in about every fifth article; the share in 2010 was nearly 50 percent. Although the local morning papers do not display differences as large as the urban morning papers, both groups clearly have changed following the tabloid transition. Again, the other two papers – the broadsheet morning paper and the evening tabloid – seem to be characterised by a similar development.

There also is an increase in other kinds of illustrations presented in news reporting, a tendency that applies to all newspapers (Table 4). Therefore, it can be concluded that newspapers in general devote more editorial space to pictures and illustrations. But, changes in the extent of the focus these features are given tends to differ between the groups. Urban morning papers have gone through the most significant change since the tabloid switch: In 2000, they had the lowest percentages of articles with pictures and illustrations compared to all other morning papers; in 2010, the situation was quite the reverse. Aside from this change, the general trend is that all morning papers have begun to converge toward a similar distribution between illustrations and the written word.

When the impact of headlines and illustrations are taken into consideration jointly, the results reveal similarities as well as differences in their development. All morning papers appear to have adopted a more similar look in the 2010s, but the extent of the changes tends to differ (Table 5). Again, urban morning papers have experienced the greatest change: In 2000, about one-fifth of the average article focused on illustrations and headlines; in 2010, the corresponding number was about one-third. Clearly, urban morning papers have been affected the most by the tabloid transition, at least when the focus is placed on the form dimension.

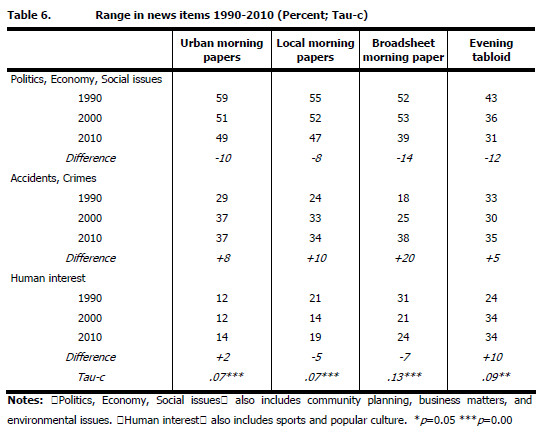

Prior research has revealed a decrease in the number of general news reports about politics and social planning, and hard news is commonly said to have decreased at the expense of soft news (Franklin, 1997; McLachlan & Golding, 2000; Plasser, 2005; Rooney, 2000). Similar tendencies are found in this study when examining the dimension of range. Articles on politics, the economy, and social issues have been reduced in all newspapers during the 1990s and early 2000s, but contrary to the results found by other scholars (e.g., Plasser, 2005), there is no simultaneous increase of articles on human interests (Table 6). A significant change is instead found in reporting on crimes and accidents.

Many scholars commonly chose to include this kind of reporting into the concept of hard news, thus equating it with subjects such as politics and the economy (see Reinemann et al., 2012); however, this change also may very well be described as an increased focus on sensational events. Reporting on accidents and tragic deaths certainly is news that, in certain contexts and for certain reasons, may be important to know about; however, when reporting increasingly focuses on the emotions and feelings of the victims, witnesses, and relatives, it also becomes more similar to the kind of reporting usually associated with the evening tabloids. Considering this perspective, Swedish newspapers are seemingly more tabloidised today than twenty years ago. This is especially true if the reporting on politics and community planning is analysed separately: In all morning papers, the proportion of these articles has been reduced by thirty percent since 1990. In the evening tabloid, the reduction is about fifty percent.

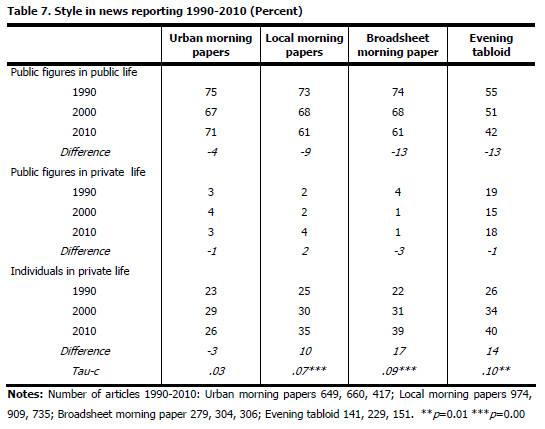

The final dimension of tabloidisation – style – measures how much space is devoted to public life and private life. Despite what was expected, the focus on private matters involving public figures has remained unchanged since the 1990s (Table 7). Redistribution is, however, seen regarding the presence of public figures in public life and individuals in private life. All newspapers, except urban morning papers, have seen a decline in the focus on public figures as professionals and a simultaneous increase in the focus on individuals. The latter dimension includes, for example, individuals affected by cuts in the public sector, victims of crime, and perpetrators of crime. These changes should be regarded as an indication of increased privatisation (cf. van Aelst et al., 2012), as the balance between public life and private life, to some extent, has been shifted. Consequently, it also means that there has been, and probably continues to be, a process of tabloidisation occurring in many daily newspapers.

Conclusions

Focusing on three dimensions of tabloidisation – form, range, and style – has allowed an analysis of how the shrinking of a newspaper´s outer form affects its inner content. The basic assumption was that it would be possible to detect some indications of an increased tabloidisation in relation to the resizing of quality newspapers. To control for changes common to the business, the analysis also included newspapers whose size had not been reduced. Indeed, there are some indications of tabloidisation in the newspapers. Firstly, the number of articles and total space devoted to news reports has decreased. Secondly, the written word is seemingly subject to competition, as illustrations are given additional space. Thirdly, reporting on political issues and community planning is declining, although the change in this area does not correspond to a similar growth in human interest stories. Rather, an increased focus on sensationalism is found within the extended reporting on crimes and accidents. Finally, focus on individuals appears to be gradually increasing in news reporting.

Most of these indicators, however, are not derived directly from the tabloid transition. Oppositely, almost all the changes appear to be common to the business as a whole, with the notion that some of them are particularly significant in certain newspapers. This is especially true regarding the growth in the number of illustrations in the urban morning paper. During the 1990s, the articles in these newspapers were distinguished by having a low percentage of pictures, a situation that clearly has changed with the tabloid transition. Therefore, the transition can be said to have accelerated the development of the urban morning papers by forcing them to catch up with the local morning papers. From this perspective, the tabloid transition has had an interactional effect on the tabloidisation of these newspapers.

Thus, this study establishes that a newspaper´s actual page size only has a minor influence on the content, except for the kind of influence tied to the editing of the page structure as such. Therefore, change associated with increased tabloidisation may be considered a matter of industrial wisdom (cf. Hellgren & Melin, 1991) rather than a consequence of going tabloid. Such content and layout developments are primarily guided by values and norms common to the business, a cultural wisdom not always visible, but most often compelling, to individual newspapers. This kind of influential power also has forced the business into increased professionalisation as daily morning papers have become more similar during the past decades in terms of outer form and inner content, e.g., form, range, and style. Thus, this study clarifies that critics who argue that quality papers that go tabloid will degenerate into journalism similar to the tabloid press (cf. Bird, 2009; Franklin, 2008; Gans, 2009) are not fully justified in their fear; the tabloidisation process already has been established for quite some time among those papers, regardless of the tabloid format.

References

van Aelst, P., Sheafer, T. & Stanyer, J. (2012). The personalization of mediated political communication: A review of concepts, operationalizations and key findings. Journalism, 13(2), 203-220. [ Links ]

Andersson, U. (2013) Från fullformat till tabloid. [From broadsheet to tabloid]. Stockholm: Vulkan. [ Links ]

Balcytiene, A. (2009). Market-led reforms as incentives for media change, development and diversification in the Baltic States: A small country approach. International Communication Gazette 71(1-2): 39-49. [ Links ]

Bek, M. G. (2004). Research Note: Tabloidization of News Media: An Analysis of Television News in Turkey.European Journal of Communication, 19(3), 371-386. [ Links ]

Bird, S. E. (2009). Tabloidization: What is it, and Does it Really Matter? In Zeilizer, B. (ed) The Changing Faces of Journalism. Tabloidization, Technology, and Truthiness. London and New York: Routledge. [ Links ]

Boczkowski, P. J. (2009). Rethinking hard and soft news production: From common ground to divergent paths. Journal of Communication 59(1): 98–116. [ Links ]

Botero de Leyva, M. (2004). Lights and shadows of format changes among newspapers. In Erbsen, C. E., Giner, J. A. & Sussman, B. (eds) WAN Report 2004: Innovations in Newspapers. Pamplona: Innovation, World Association of Newspapers (WAN). [ Links ]

Brin, C. & Drolet, G. (2008). Tabloid Nouveau Genre. Journalism Practice, 2(3), 386-401. [ Links ]

von Bucher, H-J. & Schumacher, P. (2007) Tabloid versus Broadsheet: Wie Zeitungsformate glesen werden. Ein verleichende Rezeptionsstudie zur Leser-Blatt-Interaktion. Media Perspektiven, 10, 514-528. [ Links ]

Curran, J., Salovaara-Moring, I., Cohen, S., & Iyengar, S. (2010). Crime, foreigners and hard news: A cross-national comparison of reporting and public perception. Journalism 11(1): 3–19. [ Links ]

Connell, I. (1998). Mistaken Identities: Tabloid and Broadsheet News Discourse. Javnost – The Public, 5(3), 11-31. [ Links ]

Djupsund, G. & Carlsson, T. (1998). Trivial Stories and Fancy Pictures? Tabloidization Tendencies in Finnish and Swedish Regional and National Newspapers, 1982-1997. Nordicom Review, 19(1), 101-115. [ Links ]

Erbsen, C. E., Giner, J. A. & Torres, M. (2007) Innovations in Newspapers. 2007 WAN report. Pamplona: Innovation, World Association of Newspapers (WAN). [ Links ]

Esser, F. (1999). Tabloidization of News: A Comparative Analysis of Anglo-American and German Press Journalism. European Journal of Communication, 14, 291-324. [ Links ]

Fang, I. (1997). A History of Mass Communication: Six Information Revolutions. Boston, MA: Focal Press. [ Links ]

Franklin, B. (1997). Newzak and Newsmedia. London: Arnold. [ Links ]

Franklin, B. (2008). The Future of Newspapers. Journalism Practice, 2(3), 306-317. [ Links ]

Gans, H. J. (2009). Can Popularization Help the News Media? In Zeilizer, B. (ed) The Changing Faces of Journalism. Tabloidization, Technology, and Truthiness. London and New York: Routledge. [ Links ]

Giner, J. A. (2004). The keys to the success of Polands Gazeta Wyborcza.In Erbsen, C. E., Giner, J. A. & Sussman, B. (eds) WAN Report 2004: Innovations in Newspapers. Pamplona: Innovation, World Association of Newspapers (WAN). [ Links ]

Halonen, L. (2004). Effects of newspaper structure on productivity. Stockholm: KTH. [ Links ]

Harrington, S. (2008). Popular news in the 21st century. Time for a new critical approach? Journalism, 9(3): 266-284. [ Links ]

Hellgren, B. & Melin, L. (1991). Business Systems, Industrial Wisdom and Corporate Strategies: the case of the pulp-and-paper industry. In Whitley, R. (ed) The Social Foundations of Enterprise. European comparison perspectives (pp 180-197). London: Sage. [ Links ]

Kovach, B. & Rosenstiel, T. (2007). The Elements of Journalism: What Newspeople Should Know and the Public Should Expect. New York: Three Rivers Press. [ Links ]

Langer, J. (1998). Tabloid Television: Popular Journalism and the Other News. London: Routledge. [ Links ]

Machin, D. & Niblock, S. (2008). Branding newspapers. Journalism Studies, 9(2), 244-259. [ Links ]

McChesney, R. W. & Nichols, J. (2010). The Death and Life of American Journalism: the Media Revolution that will Begin the World Again. Philadelphia, PA: Nation Books. [ Links ]

McLachlan, S. & Golding, P. (2000). Tabloidization in the British Press: A Quantitative Investigation into Changes in British Newspapers 1952-1997. In Sparks, C. & Tulloch, J. (eds) Tabloid Tales: Global Debates over Media Standards (pp 75-89). Lanham, MD, Boulder, CO, New York and Oxford: Rowman and Littlefield. [ Links ]

McMullan, D. & Wilkingson, E. J. (2004). Does Size Matter for Newspapers? The Trend towards Compact Format. Dallas: INMA. [ Links ]

Medievärlden (2012). Helsingin Sanomat blir tabloid [Helsingin Sanomat goes tabloid]. February 28th 2012.

Melesko, S. (2006). Marknads- och produktivitetsaspekterna på tabloidiseringen i landsorten [Market and productivity aspects on tabloidization in rural areas]. In Gustafsson, K.E. (ed) Lokalmediestudier [Local media studies]. Jönköping: JIBS [ Links ]

Newsbound (2010). The success of the Scandinavian Compact. 2010:1:15. [ Links ]

Örnebring, H. & Jönsson, A-M. (2004). Tabloid Journalism and the Public Sphere: a historical perspective on tabloid journalism. Journalism Studies, 5(3), 283-295. [ Links ]

Papathanassopoulos, S. (2001). Media commercialization and journalism in Greece. European Journal of Communication, 16(4):505.521. [ Links ]

Picard, R. G. (2005). Money, media, and the public interest. In Overholser, G. & Jamieson, K. H. (eds) The press. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

Plasser, F. (2005). From hard to soft news standards? How political journalists in different media systems evaluate the shifting quality of news. Harvard International Journal of Press/Politics, 10(2), 47-68. [ Links ]

Porter, M. E. (1983). Analyzing Competitors: Predicting Competitor Behavior and Formulating Offensive and Defensive Strategy. In Leontiades, M. (ed) Strategy and Implementation. Random House, Inc. [ Links ]

Porto, M. (2007). TV news and political change in Brazil. The impact of democratization on TV Globo´s journalism. Journalism, 8(4), 381-402. [ Links ]

Reinemann, C., Stanyer, J., Scherr, S. & Legnante, G. (2012). Hard and soft news: A review of concepts, operationalizations, and key concepts. Journalism, 13(2), 221-239. [ Links ]

Rooney, D. (2000). Thirty Years of Competition in the British Tabloid Press: The Mirror and the Sun 1968-1998. In Sparks, C. & Tulloch, J. (eds) Tabloid Tales: Global Debates over Media Standards (pp 91-110). Lanham, MD, Boulder, CO, New York and Oxford: Rowman and Littlefield. [ Links ]

Rowe, D. (2011). Obituary for the newspaper? Tracking the tabloid. Journalism, 12(4), 449-466. [ Links ]

Sparks, C. (2000). Introduction: The panic over tabloidization. In Sparks, C. & Tulloch, J. (eds) Tabloid Tales: Global Debates over Media Standards (pp 1-40). Lanham, MD, Boulder, CO, New York and Oxford: Rowman and Littlefield. [ Links ]

Stenberg, J. & Wiberg, L. (2004). Produktionspåverkan i övergång från Broadsheet till Tabloid [Product impact in the transition from broadsheet to tabloid]. Stockholm: Tidningsutgivarna. [ Links ]

Sternvik, J. (2005). Swedish Daily Newspapers: A Shrinking Format?. PressBusiness. Media, Markets, Leaders, Strategies, 1(1), 31-34. [ Links ]

Sternvik, J. (2007a). I krympt kostym. Morgontidningarnas formatförändringar och dess konsekvenser [In smaller suit. Daily morning papers´ format transitions and its consequences]. Gothenburg: University of Gothenburg. [ Links ]

Sternvik, J. (2007b). A Small World: Role Models in Scandinavia. PressBusiness. Media, Markets, Leaders, Strategies, 1(3), 12-16. [ Links ]

Svenska Dagbladet (2004). Tabloiden har erövrat tidningsvärlden [The tabloid has conquered the newspaper business]. October 5th 2004.

Sydney Morning Herald (2013). Read all about it: the future´s in your hands. March 4th 2013.

Uribe, R. & Gunter, B. (2004). Research Note: The Tabloidization of British Tabloids. European Journal of Communication, 19(3): 387-402. [ Links ]