Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Acessos

Acessos

Links relacionados

-

Similares em

SciELO

Similares em

SciELO

Compartilhar

Observatorio (OBS*)

versão On-line ISSN 1646-5954

OBS* vol.7 no.3 Lisboa jun. 2013

Cinema and/as Revolution: The New Latin American Cinema

Sergio Roncallo*, Juan Carlos Arias-Herrera**

*Universidad de la Sabana, Chía , Colombia

**Pontificia Universidad Javeriana, Bogotà, Colombia

ABSTRACT

The New Latin American Cinema has been traditionally defined as a political cinema committed to the transformation of the social conditions that characterized Latin America in the 1960s. The notion of revolution has been placed in the core of this movement. Deeply influenced by the Cuban Revolution in 1959 and by several political movements throughout the continent, a group of filmmakers proposed an aesthetic transformation of what they described as a colonized culture. Our aim in this essay is to explain what these filmmakers understood by a cinematographic revolution that could be the condition for a broader political and social transformation. It is not our intention to stand up for the concept of revolution in the New Latin American Cinema, but to try to avoid the stereotypes around this concept and to understand what this notion involved within a particular context.Keywords: New Latin American Cinema, revolution, politics, social transformation, representation.

We understand what cinemas social function should be in Cuba in these times: It should contribute in the most effective way possible to elevating viewers revolutionary consciousness and to arming them for the ideological struggle which they have to wage against all kinds of reactionary tendencies and it should also contribute to their enjoyment of life (p. 110). These words were written in La Habana, Cuba by Tomás Gutiérrez Alea in 1982. Although he tried to announce the responsibility of cinema production in the 1980s, those words could be used as an accurate description of the spirit of the New Latin American Cinema movement during the 60s and 70s. Not only in Cuba but also throughout several countries in Latin America, the 1960s represented the decade of the integration between cinema and revolution.

The term revolution appears repeatedly and emphatically in all the discourses, interviews, texts and films composed by the major figures of the movement: Fernando Birri, Fernando Solanas and Octavio Getino in Argentina; Glauber Rocha and the Cinema Novo in Brazil; Jorge Sanjinés and the Ukamau group in Bolivia; Julio García Espinosa and Tomás Gutierrez Alea in Cuba; Miguel Littín, Raúl Ruíz and Patricio Guzmán in Chile1. These are only a few of the names that composed one of the largest new cinema postwar movements in the world. All of them explicitly stated a close relation between cinema and politics to the point that today it is almost obvious to talk about the New Latin American Cinema as a political revolutionary movement. As López (1997) points out, the New Latin American Cinema is a political cinema committed to praxis and to the socio-political investigation and transformation of the underdevelopment that characterizes Latin America. (p. 137) It is not our intention to argue against this kind of interpretations, but to try to understand that relation between cinema and politics focusing on the concept of revolution. What did those authors understand by revolution? And, probably more important, what was the role of cinema in that idea of revolution?

The term revolution seemed to be omnipresent during the decade of the 1960s. It was not confined to Latin America, but the world that the idea of revolution was part of the social imagery of the time. All those who used the term to support or oppose it, seemed to understand and share an implicit common definition. However, the notion of revolution has had several and dissimilar uses. The word appeared during the fourteenth century as a derivative of the Latin revolvere used to refer to the natural laws of cyclical movements in the heavens. (Craven, 2006, p. 6) A paradigmatic case is Nicolas Copernicus well-known De revolutionibus orbium coelestium (On the Revolutions of Celestial Spheres) published in 1543. The book, besides having the revolutions –movements– of the celestial bodies as main topic, was also catalogued as a revolution –a fundamental change– in the field of astronomy and science in general.

Craven (2006) suggests that the political sense of the term appeared in the late seventeenth and early eighteenth century as an alternative to words like revolt and rebellion. With the French Revolution, for instance, the term came to mean the legitimate natural subversion or overthrow of tyrannical leaders. But probably it was in the nineteenth century with figures like Marx and Engels when the contemporary use of the term appeared through its connection with the concept of ideology. Since the mid-nineteenth century, it has not longer been plausible to speak of a non-ideological revolution. An uprising that addresses only local inequities now means no more than a rebellion or a revolt. (p. 8) This connection with the notion of ideology, instead of unifying the meanings of the term revolution, seemed to multiply its ambiguity. Marx and Engels concept of revolution has been subject to several interpretations and modifications to the point of generating radical discussions about the original meaning of the term. Probably Marxs famous, and sometimes decontextualized and misinterpreted, affirmation about its own Marxism quoted by Engels (2000), is the best example to show the ambiguity of the term: All I know is that Im not a Marxist.

Today the situation does not seem to be different. Notions like revolution and revolutionaries have been incorporated into the collective consciousness through a series of texts and images massively spread throughout the last decades. It is difficult to imagine someone today who does not know the image of Ernesto el Ché Guevara popularized by the famous picture Heroic Guerrilla taken by Alberto Korda in 1960. El revolucionario seems to be, not only in Latin America, a well-known figure that everybody could recognize. That common stereotype has worked for producing both vindicating and scornful discourses –sometimes state discourses– that have placed the concept of revolution in the center of political polarization in many countries.

Cinema has not been isolated from this situation. The emphasis on revolution made by the New Latin American Cinema in the 1960s and 1970s created the stereotype of political cinema around which extreme positions have emerged, just as in the political arena. Besides the division between the filmmakers against any possible political use of cinema and the explicit militants within a particular ideology, there is a current widespread artistic trend that openly declares its political neutrality. In the 27th Chicago Latino Film Festival in 2011 the Colombian filmmaker Carlos César Arbeláez affirmed, after the projection of his film The Colors of the Mountain (2010), that his intention was to offer a non-politicized perspective on the internal conflict in Colombia. Arbeláezs position is only one of multiple examples of artists who have tried to defend a neutral position regarding the reality of Latin American peoples probably as a reaction to the excesses brought about by the stereotype of the revolutionary filmmaker and the committed cinema. The political commitment of movements like the New Latin American Cinema seems to be reduced or simply ignored in several contexts today, most of the time without a deep comprehension of what that commitment implied.

It is our intention to stand up for the concept of revolution in the New Latin American Cinema, but to try to avoid the stereotypes and to understand what this notion involved within a particular context. It could be useful to think of the relation between arts and politics beyond the modern polarization between militant and neutral art. That relation has been object of a second prejudice.

Commonly, authors that have analyzed the relation between cinema and politics assume these two notions as separate fields that find matching moments with specific filmmakers and movements. Thus, categories like political cinema have been created to define films that portray topics related with what we commonly understand by politics. In the case of the New Latin American Cinema the most common way to reading it is to understand its relation with politics as the implementation of external ideas to the composition of the contents of the films. On the contrary, we would like to think of the relation between cinema and politics as a relation of mutual recreation instead as a relation of application or representation. So, our question is not how New Latin American filmmakers applied an idea of revolution to cinema, but how they created a cinematographic idea of revolution, not only through the contents of the films, but also focusing on the formal composition and the logics of production.

1. Why a Revolution: the Problem of Representation

Unlike other new cinemas in Europe which emerged in the same period, like the French New Wave, the New Latin American Cinema has not a clear birth year or a foundational work. The name was given at the end of the 1960s to a group of filmmakers from different countries in Latin America who, since the 1950s, had shared a common interest in changing the social function of cinema. López (1997) characterizes this decade by the rise of nationalism and militancy, evident in several political and social incidents throughout the continent: the bogotazo in Colombia in 1949, the unfinished workers revolution in Bolivia in 1952, liberal reforms in Guatemala in 1954 which provoked U.S. intervention, the suicide of the populist Brazilian President Vargas in 1954, the military overthrow of Argentine President Perón in 1955, and, most significantly, the guerrilla war in Cuba which led to the establishment of a socialist regime in 1959. (p. 139) Cinema, and culture in general, were not impervious to this atmosphere of political activism.

Most of the texts written by the New Latin American filmmakers during this period stated an explicit position about cinematographic production directly connected to a political attitude derived from a particular interpretation of Latin American current conditions. The particular language of those texts reveals a strong connection with the revolutionary ideas of the time. Imperialism, the System, the enemy, historical consciousness, guerrilla activity, the masses, the people, were some of the terms used to reflect on cinema production. This particular language could be interpreted as an application of political ideologies to the field of cinema. However, these authors considered this interpretation as a dangerous misreading of revolution at the extent that it implied a dichotomy between politics and art. If the terms used to speak about the political revolution were the same used to reflect about cinema, it was because there was not any distance between arts and politics. Cinema was not a representation of political ideologies, but a political practice itself.

It can be useful to compare these texts with other manifestos written during the same years in Europe to understand the singular relation between art and politics those authors stated. While texts like the Oberhausen Manifesto written in 1962 as basis for the New German Cinema discussed the possibility of producing new movies as an exclusive problem of film industry, Latin American filmmakers expanded the discussion about cinema to a broader context. Cinema was not only a cinematographic issue, but especially a social problem. Almost in a contrary way to the points made by the French New Wave at the end of the 1950s about cinema as an instrument of individual expression, the New Latin American filmmakers stated from the beginning the need of thinking of cinema as a social instrument, never isolated from the political trends of its time. Somehow, the idea was simple: in times of revolution it was necessary to create a revolutionary cinema. Thus, cinema would follow and reproduce the ideas of the revolutionary movements of the period working as a spreading instrument. While the avant-garde cinema in Europe created the idea of an almost autonomous cinema that implied to reject any external ideology in order to exalt the individual expression and the formal independence of the authors –what the Oberhausen Manifesto called new freedoms–, in Latin America the adjective new was directly associated with creating resonances between the films and any other cultural and political expressions. The novelty of this cinema lay, precisely, in its political commitment instead of in its self-reflective character.

In this sense, the causes that made necessary to create a new cinema were also different in Latin America and in Europe. The New Latin American filmmakers seemed to share a common enemy with the European movements of the period: Hollywood and its influence on national models of cinema production. The expansion of American commercial cinema around the world created a dynamic of reproduction of a particular model of narration and production in several countries that were looking for the foundation or consolidation of a national industry. However, the consequences of this model were different according to each movement. For the European avant-garde it seemed to be an internal problem to the logics of composition and production of a film. For Latin American filmmakers, on the contrary, the problem was not that Hollywood affected film production, but that through it Hollywood was an instrument of colonization in Latin America. Thus, to rebel against Hollywood was the equivalent to rebel against colonization in a broader political sense. The problem was not the films as such, but cinema as symptom of a particular political and cultural condition. Changing cinema was part of a broader social transformation. Our purpose is to create a new person, a new society, a new history and therefore a new art and a new cinema. Urgently. (Birri, 1997a, p. 87) The question is what the role of cinema in that transformation was; how they connected the new society with the new cinema.

In order to understand the revolutionary role of cinema, it is important to further define the enemy of the revolution. Authors like Glauber Rocha (1997) affirmed that Latin America was object of a new type of colonialism several years after the end of the independence movements throughout the continent. What distinguishes yesterdays colonialism from todays colonialism is merely the more polished form of the colonizer and the more subtle forms of those who are preparing future domination. (p. 59) What Rocha identified as these subtle mechanisms of colonialism were not political interventions or state matters, but a problem of representation. The imposition of European and American terms to think of reality, for instance, the duality between civilization and uncivilized, created a distorted representation of Latin America, not only for Europe and the U.S., but especially for Latin Americans themselves. Latin America was freed from the political control of its territory, but maintained the basic colonial terms to think of its own reality. Understanding –or, rather, misunderstanding– of these countries has always come about by applying analytical schemes imposed by foreign colonialists or their local henchmen. (Birri, 1997a, p. 87)

The problem of this colonial representation is that it created an alienated consciousness of reality. Latin American people received an image of its own condition, of its own misery, constructed through terms imposed by others. Latin American people were not able to perceive a true image of their own condition because they thought about themselves using external categories, concepts, and information. In a similar way that Marx used the concept of alienation to define the distance created by capitalism between the worker and his/her own product, Latin American filmmakers used colonialism to denounce a distance between the people and their own reality.

Rocha (1997) made one of the best descriptions of this alienation through a reflection on the hunger of Latin American people: For the European it is a strange tropical surrealism. For the Brazilian it is a national shame. He does not eat, but he is ashamed to say so; and yet, he does not know where this hunger comes from. (p. 60) It was not enough to have an experience of hunger to be aware of the nature of that hunger, because the experience itself has been alienated by the bad conscience, as Birri (1997a) called it, produced by capitalism.

Hollywood seemed to be the incarnation of this misrepresentation of Latin American reality. Lopes (2004) quotes Rocha to explain the problem:

There is a big influence of Hollywood in Brazilian cinema: for example, the desire for greatness. What we never accept of Hollywood was not its greatness, its development or its sophistication; what we always rejected of Hollywood was its colonialist ideology in relation to natives and blacks, and in relation to the underdeveloped peoples (which is unquestionable in the American westerns and the police ones) and we also reject their moral in the sense that the American way of life (which is a goal of American democracy) would be ours as well. (p. 82)

Hollywood presented a distorted image of Latin American reality not only when the films tried to directly depict Latin American people, but also by offering an idealistic image of progress and civilization; image that has been always based on its counterpart of poverty and misery. In this sense, Hollywood was one of the most powerful instruments of the system because it created a colonized logic of representation; it spread a particular ideology that distanced the people of a deep understanding of their own reality.

In this sense, for the New Latin American Cinema revolution meant, in the first place, to transform the processes of self-representation within the continent. A revolutionary cinema was not only a means of communication of the political revolution but one of the fields in which the revolution must be produced. Authors like Solanas and Getino (1997) in Argentina even suggested that the cinematographic and cultural revolution was a condition for the political one: The revolution does not begin with the taking of political power from imperialism and the bourgeoisie, but rather begins at the moment when the masses sense the need for change and their intellectual vanguards begin to study and carry out this change through activities on different fronts. (35) From this perspective, cinema was one of the instruments to generate a revolutionary consciousness in the masses. The relation between these masses and the intellectual filmmaker was one of the main problems for the New Latin American Cinema. Part of the movements objective was to transform the traditional passive role of the audiences created by American cinema giving the people the opportunity of taking an active position in the films. We will explain later how this popular cinema, as Sanjinés (1997) called it, could work. For now, we would like to emphasize the affirmation of cinema as an instrument of knowledge: to generate a genuine consciousness of Latin American conditions and suppress the alienated representations imposed by colonialism, cinema had to work as a means to access the true reality of Latin American peoples.

The question is how it was possible to depict this true reality and generate a revolutionary consciousness through cinema. Our proposal is to understand this revolutionary production of new self-representations in three main senses: as content, as form, and as a new logic of production.

2. Revolution in the Contents: Cinema as Means of Knowledge

Commonly, the term political cinema has been associated with films that include explicit ideological contents, almost cinematographic pamphlets that only illustrate external ideas. Jorge García Espinosa (1997) radically opposed this idea highlighting arts own cognitive power: art is not the illustration of ideas ( ) Every artists desire to express the inexpressible is nothing more than the desire to express the vision of a theme in terms that are inexpressible through other than artistic means. (p. 73) In this sense, cinema was not a simple reproduction, but the practice of showing something that only became visible through the mediation of image. That is precisely what the New Latin American filmmakers called reality.

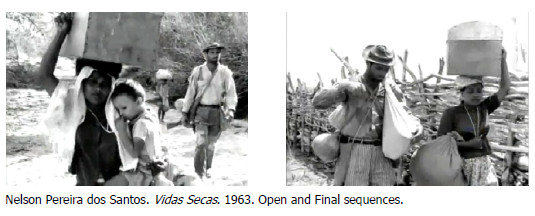

The revolutionary character of cinema was based on a deep trust in its capacity of showing a naked reality (Solanas & Getino, 1997, p. 44), of depicting how reality is (Birri, 1997a, p. 93) devoid of any colonizing ideology. Rocha (1997), for instance, highlighted the contribution of the Cinema Novo showing peoples hunger in Brazil outside of any kind of primitivism or exoticism. The camera could depict that reality that people could not perceive in their own daily experience because of their condition of alienation. Thus, Cinema Novo devoted itself to present peoples hunger in all its faces. Nelson Pereira dos Santos Vidas Secas (1963) is one of the best examples. The film tells the story of a family –Fabiano, the father; Sinhá Vitória, the mother; two sons and their dog–, in the sertão in the northeast of Brazil that lives in the permanent and futile searching of a better place to live, with food and work. There must be a place for us in Gods world. These words pronounced repeatedly by Vitória to her sons summarize the story and the changeless condition of the characters that seem to move in an endless cycle –the film begins and ends with similar sequences of the family walking in the dessert looking for a new home–.

Like Vidas Secas, several movies told the story of groups or individuals condemned to a continuous cycle of poverty. This cyclical character was a central narrative strategy for the Cinema Novo. Under the influence of Hollywood, the Latin American spectator had been accustomed to perceiving stories with a linear development; plots in which the characters struggle against the opposing forces of the world resulted in the restoration of a balance, most of the times through a happy ending. Following a neorealist influence, the New Latin American Cinema broke with the concept of action, central in the traditional cinema they wanted to oppose. Instead of showing characters overcoming obstacles to transform their situation, Brazilian filmmakers emphasized on the pure struggle without any result. That is one of the reasons why the sertão became a central place in their stories. This desolated context was a reflection of the internal situation of the characters, of the impossibility of change. The characters trip across the desert became an irony of the traditional Hollywoods transformation journey in famous genres like American Western. The physical displacement is not the action of transforming the relation between the character and his/her own world –basic structure of the American dream in Hollywood films–, but the affirmation of some kind of permanent paralysis in the individuals.

In this sense, those films were not simple descriptions of hunger, but attempts to produce a deep understanding of its singular character beyond the traditional categories that had described that condition. In Rochas terms, the Cinema Novo did not show a primitive or underdeveloped poverty, but the most simple, physical behavior of the hungry: violence. Cinema Novo shows that the normal behavior of the starving is violence; and the violence of the starving is not primitive ( ) From Cinema Novo it should be learned that an esthetic of violence, before being primitive, is revolutionary. (Rocha, 1997, p. 60) By emphasizing on violence Rocha was trying to recover the most basic character of hunger forgotten by its capitalist categorization. Showing the violence of the hungry, cinema could make the public aware of its own, and until that moment misunderstood, misery.

That is the reason why the concept of documentary was always on the basis of the New Latin American Cinema, even in those filmmakers who always produced fictional films. Latin American filmmakers perceived the traditional division between documentary and fictional films as a product of the capitalist industry that they had to overcome. In their terms, there was not any contradiction between fiction and real document. As Gutiérrez Alea (1997) stated, such a way of looking at reality through fiction offers spectators the possibility of appreciating, enjoying, and better understanding reality. (p. 122) Thus, to produce a document did not imply to reproduce reality just like it was –which is just like the viewer was used to perceive it. Cinema, through the creation of a new reality, could reveal deeper and more essential layers of reality itself. Images could show what the colonizing ideologies had covered, what the System found indigestible. (Solanas & Getino, 1997, p. 46)

The question is how to find those deep layers of reality. Was it enough to go out with a camera to find the truth hidden by the System? Was it enough to tell the story of starving characters to compose a revolutionary cinema? As we stated above, the problem of colonization was especially a matter of language, of logics of representation. It was not enough, therefore, to show what the System did not want to show, but to depict it through a new and proper language. Latin American revolution implied the creation of a new way to speak about Latin America itself, an original mechanism of representation. The problem was not only what to show, but also how to show it.

3. Revolution as Form: the Invention of a New Language

In 1953 Fidel Castro pronounced his famous defense speech History will absolve me during his trial for rebellion. One of the main topics of the speech was the importance of revolutionary discourse, of the voice of the revolution. According to Castro, revolutionaries had to find a proper voice; they must speak differently to the official state discourse. A revolutionary voice should, in the very first place, take an evident distance from the oppressive voices in the nation. The first way to do it was to affirm the truth of revolutionary speech opposed to the lies of official discourses. Revolutionary language always told the truth because, according to Castro, it followed the simple logic of the people. (2001) Therefore, to tell the truth it was necessary to create a new language, the language of the people.

Together with Castro all the main figures of the revolutionary movements in Latin America shared this common concern about speech. Every revolution created, sometimes even imposed, a new language as the basis for the creation of a new reality. The New Latin American filmmakers seemed to share this awareness of the need of a new language directly connected with the truth of Latin American peoples.2 Film form was a major concern for the movement as an instrument to produce a critical consciousness in the viewers.

A common concept appears in most of the texts written by the New Latin American filmmakers since the end of the 1950s: dialectics. The concept refers to Marxs notion of history and, especially, to its filmic implementations in the Russian avant-gardes in the 1920s. In several texts, Rocha (2003; 2004b; 2006) referred explicitly to the contributions of Sergei Eisenstein as a main reference for the construction of a Latin American cinema. According to Eisenstein (1958), if cinema wanted to be a revolutionary instrument, it would need to follow a dialectical form that could produce intellectual effects on the spectator by depicting the dialectical character of reality. Eisensteins major contribution was to affirm that, in order to produce a revolutionary effect, cinema must be composed with the same principle as the reality it wanted to depict. Thus, if the objective was to show the people the contradictions of their own material conditions, that is, to show what Gutiérrez Alea called the deep layers of reality, the film itself must be composed following the principle of those contradictions. For Eisenstein, just as for Latin American filmmakers like Rocha, Solanas, Getino, and Gutiérrez Alea, the key of a revolutionary cinema was to create a structural analogy between reality, film and thinking. In short, a social reality –misery, underdevelopment, hunger– defined by internal contradictions, that is, a dialectical reality, needed a dialectical film form that produced in the people a deep consciousness of their own condition. It is important to consider these three levels of the concept of dialectics and its filmic implementation.

The concept of dialectics has an extensive history in Western thought from classical Greek philosophy to the most popular uses of the term in Hegel and Marx. The latter two authors are probably the main references to understand the New Latin American Cinemas concept of dialectics and its essential role in arts.

Although the multiple differences between them, Hegel and Marx share a common assumption about the concept of dialectics: it is not only a subjective thinking method but the ontological dynamic of reality itself. According to Hegel, dialectics is a method to study things in their own being and movement. (1874, Note to §81) If this method is necessary, it is because this own being of reality has a dialectic character: Wherever there is movement, wherever there is life, wherever anything is carried into effect in the actual world, there Dialectic is at work. (Ibid) This kind of omnipresent character of dialectics conduced Hegel to affirm that being was dialectical. In his terms, absolut spirit evolves toward its ideal realization through historical stages of self-negation. This is probably the main point that Marx criticized in Hegels philosophy. Although Hegel placed dialectics in the concrete field of historical experience, history was only the material manifestation of Spirits development. Marx disagreed with this objectivization of dialectics as an entity out of history. If dialectics was the driving force of reality, it did not imply that it was an external principle to history.

The concepts of dialectics and history are inseparable in Marxs thought. One of his major objectives was to determine the cause of the transformations of history, not only to describe it, but especially to determine a potential principle of action that could transform the present conditions of men. Unlike Hegel, Marxs concept of history was not based on an essentialist assumption of being as dialectical process, but on a real economic fact: the more wealth workers produce, the poorer they become. The worker had been alienated by an estrangement of the objects he/she produced. Thus, Marx wanted to think of history of man as social being. He was not interested in abstract beings immersed in a spiritual process that determines them but in living and real individuals. And the most real aspect of these individuals was their material conditions of production. Thus, history was not, according to Marx, the manifestation of Spirit but the development of relations of production. These relations had a dialectical character, evident in Marxs concept of class struggle.

In a text from 1880 Engels explained this materialistic concept of history and its distance from Hegels thought as one of Marxs major contributions: Hegel has freed history from metaphysicshe made it dialectic; but his conception of history was essentially idealistic. But now idealism was driven from its last refuge, the philosophy of history; now a materialistic treatment of history was propounded. (2003) In short, Marxs historical materialism pointed out that dialectical relations of production were the driving force of history. Therefore, it was indispensable to create a dialectical approach to the study of history in order to understand its necessary dynamics and using them for the emancipation of the proletariat. Thus, if it is needed to create a dialectical method to study history it is because history itself has a dialectical character. According to Marx, to know a dialectical object implied to use a dialectical method. That is probably one of Marxs major contributions: knowledge had to assume the same form of its object. Knowing did not mean to apply an external method to a particular object, but to derive a method from the nature of the object itself. Here, dialectics defined as method finds a direct connection with dialectics as object of knowledge. In short, Marxs thought was based on the possibility of knowing dialectically the dialectical character of history.

At the end of the nineteenth century this new materialistic perspective on history meant a deep transformation in the models and methods to think of reality. In the afterword to the second German edition of Capital in 1873, Marx explained the cause of this change and the common reactions it generated:

In its mystified form, dialectic became the fashion in Germany, because it seemed to transfigure and to glorify the existing state of things. In its rational form it is a scandal and abomination to bourgeoisdom and its doctrinaire professors, because it includes in its comprehension and affirmative recognition of the existing state of things, at the same time also, the recognition of the negation of that state, of its inevitable breaking up; because it regards every historically developed social form as in fluid movement, and therefore takes into account its transient nature not less than its momentary existence; because it lets nothing impose upon it, and is in its essence critical and revolutionary. (Marx 1873; emphasis added)

This critical character is the core of the dialectical method. It does not imply to describe the present conditions of the people, but to understand the material forces that have created that conditions and, therefore, the necessary finality of history. By understanding dialectics as the possibility of historical awareness Marx linked the concept with the notion of revolution: the dialectical method, as critical approach to the present, was the basis of transforming action. This triple relation between dialectics, history and revolution seemed to be the basis for the New Latin American Cinema. Like Marxs dialectical method, its objective was to produce the awakening of the consciousness of reality. (Birri, Cinema and Underdevelopment, 1997a, p. 94)

The main question is how to apply Marxs concept of dialectics to the creation of a film. Rocha and Gutiérrez Alea highlighted, following Eisensteins reflections on cinema, the importance of the montage in the composition of a dialectical film. The key was the ability of film to produce connections between isolated elements: Cinema can reach greater depth and generalization by establishing new relations among those images of isolated aspects. Thereby, those aspects take a new meaning –a meaning not completely alien to them, and can be more profound and more revealing– upon connecting themselves to other aspects and producing shocks and associations which in reality are dilute and opaque because of their high degree of complexity and because of day-to-day routine. (Gutiérrez Alea 1997, 122; emphasis added)

Eisenstein (1958) explained this ability in The Cinematographic Principle and the Ideogram. By analyzing Japanese ideograms he shows how the combination of heterogeneous images could produce the representation of a concept, something that is graphically undepictable. (30) Thus, the juxtaposition of opposite formal elements in the montage of a film made the depicting of abstract ideas possible. This juxtaposition supposed an active role of the viewer. The conflict of images generated a shock in the viewers perception that forced him/her to create a synthesis through an active process of thought. This is precisely the dialectical effect of the films. The dialectical form produced a conflict in the viewer that must be solved in order to understand the dialectical character of reality depicted in the film. Thus, cinema was not a passive representation, but an instrument to wake the viewers up from their colonizing dream.

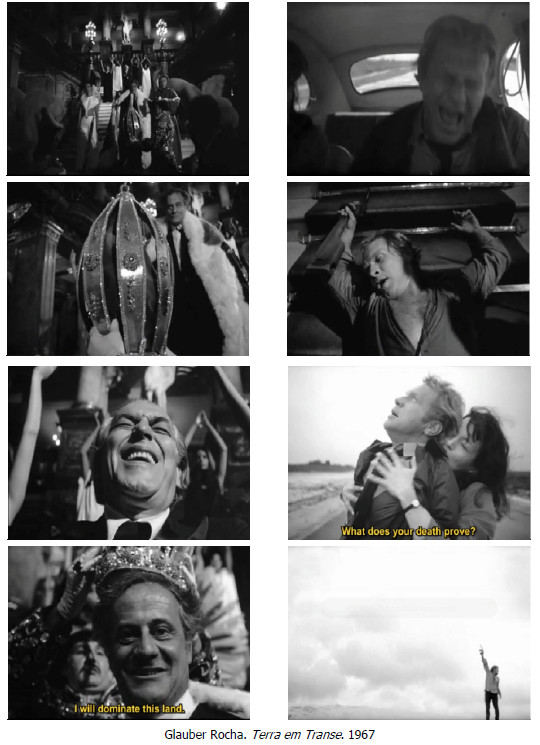

The final sequence of Rochas Terra em Transe (1967) is a good example of this dialectical principle deployed on the montage. The film tells the story of Paolo Martins, a revolutionary journalist in the imaginary state of El Dorado who begins a close relation with the populist politician Felipe Vieira looking for establishing a revolutionary government in the country against the rightist Porfirio Diaz. Vieira, however, rejects Paolos offer to take up arms to defeat Diaz, so the latter is crowned President while Paolo dies as part of the armed revolutionary struggle. The film begins with Paolos final moments, flashes back to the events that conduced him to that situation, and returns to the sequence of his death at the end. In that final sequence Rocha opposed the shots of Diazs coronation with Paolo falling shot dead by the police: the death of the revolutionary against the rise of the tyrant. However, it is not only a narrative opposition. Rocha accelerates the montage by shortening the duration of the shots, and mixes images from Paolos past struggles, Diazs fantastic coronation, sounds of gunfire, piano classical music, and a voice over asking how much longer people can stand oppression. All these formal conflicts culminate in the final image of Paolo, mortally wounded, raising his weapon in a closing symbolic gesture.

Through this type of formal strategies Rocha and the New Latin American filmmakers aimed at producing a new consciousness in the viewer. This was the new language demanded by the revolution, the language capable of breaking the colonizing logics of self-representation by producing a dialectical effect in the viewer. Only a dialectical cinema was able to show the true reality of Latin American peoples, its dialectical richness, (Solanas & Getino, 1997, p. 47) and, therefore, to get them out of their condition of alienation. This intersection between film form, reality, and the effect on the viewer was the basis for the definition of a revolutionary cinema: The work itself must bear those premises which can bring the spectator to discern reality. That is to say, it must push spectators into the path of truth, into coming to what can be called a dialectical consciousness about reality. Then it could operate as a real guide for action. (Gutiérrez Alea, 1997, p. 129)

A main question that seems to remain open is who was able to recognize and depict the truth to the alienated people. One could think that, like the political leaders of the period, the New Latin American filmmakers presented themselves as the incarnation of the will of the people. Cinema has been always based on a hierarchical structure in which the filmmaker decides what the audience sees. In this sense, it has worked as a perfect means of communication of particular ideologies based on a division between the people and their, sometimes self-proclaimed, leaders. The use of cinema as propaganda is the best example of this point. A group of intellectuals, most of them men, committed with the state, decided the contents and the form of the films produced on behalf of the people. That is one of the main critiques filmmakers like Eisenstein received throughout the twentieth century. The revolutionary cinema became at the end the work of an elite with some privileges. An elite that tried to dissolve itself in the rhetoric of the logic of the people.

The New Latin American Cinema seemed to be aware of this problem. For that reason, those filmmakers stated the need of transforming film conditions of production to reach a real popular cinema. The revolution, besides a problem of contents and form, was a problem of production and exhibition.

4. The Revolution as Production: For a Collective Cinema

One of the most notable differences between the New Cinema in Latin America and other new cinema movements around the world was the particular relation between avant-garde and industry the former movement affirmed. While in the European cinema the avant-garde involved the radical negation of any type of industry in defense of an independent or resisting cinema, in Brazil, and most generally in Latin America, the avant-garde was only possible with a transformation rather than a negation of the industry. This is the core of the discussion between Rocha and the French filmmaker Jean-Luc Godard in the 1960s.

Rocha had a relatively close relationship with Godard. He met Godard personally in France and shared with him some discussions about the present and the future of cinema. He even participated as an actor in a scene from Vent dest, filmed by Godard in 1969. Rocha permanently expressed a strong admiration by Godard throughout his texts using him as a main reference of the dialectical-revolutionary cinema. However, despite the great closeness and admiration for Godard, Rocha was aware of the deep gap between them. He explained that distance in these terms:

He criticizes me saying that I have a producer mentality; then he asks me to help him destroying cinema; there I tell him that I am in something else; I tell him that my business is creating cinema in Brazil and in the Third World; then he asks me to play a role in the film and then he asks me if I want to shoot a scene of Vent dest and (being the wise guy that I am, and having a No-Trusting machine) I tell him to calm down because I am only there for an adventure and it is not funny for me getting into the gigolos collective folklore of the unforgettable French May. (2006c, 318)3

The distance mentioned in Godards recrimination is indeed the interest of Rocha to establish the conditions of a national production in Brazil. This does not mean that a Brazilian cinema industry did not exist before, but for Rocha such industry sponsored by the State was only producing colonized, bourgeois mini-films announcing a new form copied from the old American underground. (2004a, 56) It was necessary to create an industry according to the conditions of Latin American peoples. Thus, industry and avant-garde were not two contradictory objectives according to New Latin American filmmakers: The old controversy between commercial film and art film is false and hypocritical. (Rocha, 2004a, p. 66) The question is how this industry should work in order to avoid being a simple reproduction of the European and American models that have traditionally produced a cinema of entertainment supported by the division between filmmaker and the audience. In García Espinosas words, what can be done so that the audience stops being an object and transforms itself into the subject? (1997, 75)

According to the New Latin American filmmakers the core of the new industry was the collective character of the films that implied the breakdown of the traditional division between the privileged filmmaker behind the camera and the masses in front of it. Revolutionary cinema cannot be anything but collective in its most complete phase, since the revolution is collective. (Sanjinés, 1997, p. 63) The objective was to transform the traditionally exclusive practice of filmmaking into a collective activity in which people could depict their own reality without any restriction. This process of democratization did not imply to impose a high aesthetic taste on the masses. García Espinosa was careful of avoiding the homogenization of the masses: The new outlook for artistic culture is not longer that everyone must share the taste of a few, but that all can be creators of that culture. Popular art has absolutely nothing to do with what is called mass art ( ) Popular art needs and consequently tends to develop the personal individual taste of a people. On the other hand, mass art (or art for the masses), requires the people to have no taste. (1997, 76) The ideal role of the filmmaker was the one of a provisional leader who, after waking a revolutionary consciousness in the people, should disappear into the masses by becoming a proletarian.

Thus, it is possible to recognize different stages in what the New Latin American Cinema understood by revolution. In a first stage it was necessary to build a group of intellectuals, what Solanas and Getino called a film-guerrilla group, (1997, 49) which would breakdown the colonizing logics of representation through the implementation of a dialectical cinema. This shift in the perception of Latin American reality would inevitably lead to the dissolution of the guerrilla filmmakers into the masses of the people. In that point the process of democratization of cinema would be complete, and a true popular cinema could emerge. A type of cinema produced by the masses in which the creators are at the same time the spectators and vice versa. (García Espinosa, 1997, p. 76) Just like the armed guerrillas, the film-guerrilla group was only a means to build a popular cinema. The words of Ernesto el Ché Guevara about the guerrilla warfare can describe also the spirit of the New Latin American Cinema: Above all, we must emphasize at the outset that this form of struggle is a means to an end. (Guevara, 2005)

It is not clear when it was possible to move from one stage to another. Some authors even suggested that these two steps were not chronologically divided, but they could occur simultaneously. What we would like to highlight is the way those filmmakers replicated in the field of cinema a particular idea of political action. Solanas and Getino (1997), perhaps, defended the most radical perspective through the concept of guerrilla. According to them, the only difference between the army guerrillas and the film-guerrilla group was the type of weapons each one used. In their particular case, the idea of a revolutionary cinema was constructed with the language of the army struggle: the filmmakers were in a long war that required using the camera as our rifle to defeat the enemy working underground (50). For Solanas and Getino, revolutionary cinema seemed to be a problem of application of political ideas to cinema.

Other authors, however, went further in defining the relation between cinema and politics. They shared the common objective of projecting in the cinema production the principles of the political struggles throughout the continent, but they did not define it as a simple application. According to Rocha (2006a), for instance, Solanas and Getino confused a revolutionary cinema with activist films:

The artist must demand a precise identification of what revolutionary art at the service of political activism is; of what revolutionary art thrown into the spaces opened up to new discussions is: and of what revolutionary art by the left and operated by the right is. As an example of the first case, I, as a man of film, cite La hora de los hornos, a film by the Argentine Fernando Solanas. It is typical of the pamphlets of information, agitation and controversy that are currently used by political activists around the world. To illustrate the second case, there are some films, including my own, from the Brazilian Cinema Novo.

Rochas critique to film-pamphlets shows a new way of defining the relation between arts and politics. Most of the New Latin American filmmakers proposed to eliminate the traditional distance between those two terms established by capitalism. Cinema was not more a matter of entertainment, and politics a field related with state operation. The concept of revolution implied to break that division by making of art a political practice. In this sense, the objective of building a popular cinema was equivalent to the purpose of taking political power in the guerrilla groups. Both were modes of overcoming the oppressing conditions of underdevelopment in Latin America, the former through the modification of the logics of representation and the latter through the state administration. For some authors those were not different objectives. Others, like Glauber Rocha (2006a), were skeptical of the political revolution as the end of colonialism. Taking political power does not imply the success of the revolution. For him, it was more important to change the rationality of the people, their logics of representation than the structures of the state.

Rochas perspective shows a complex relation between Latin American filmmakers and political revolutionaries. He seemed to be aware of the excesses that could be made on behalf of the people and the revolution. Sometimes what these new filmmakers understood by revolutionary cinema did not match with the definition the political revolutionaries gave to the term. Over the years, the project of a new cinema seemed to break away from the direct struggle for power. Revolutionary filmmakers became aware that their relation with State, regardless of who was in charge of it, would be always problematic.

5. A Utopian Project?

Despite the internal differences among the filmmakers, they shared a common objective, at least as an ideal: not to replace a colonizing ideology for a homogeneous and massive culture, but to create an active spectator who could think for him/herself. A true revolutionary cinema must highlight the multiple characters of the people instead of creating an amorphous mass ready to follow its leaders. Revolution means to give the people the instruments to represent themselves and, therefore, to critically understand their own reality.

Was that really possible? It is common today to hear expressions like post-utopia and post-communist art to define an era in which artists seem to overcome the idealistic perspectives of the artistic creation from the 1910s until the 1970s. What this kind of terms reveal is that movements like the New Latin American Cinema, among others, are perceived today almost as impossible political dreams that clearly failed in implementing a new reality. Although Marx and Engels made an explicit critique to the utopian socialism trying to give socialism a scientific basis, terms like communism are associated today with an unattainable idealization of social organization. If one judges projects like the New Latin American Cinema from the perspective of the empirical results it would be easy to classify it as a utopia that showed its limitations during the second half of the twentieth century.

In 1985, Birri (1997b) affirmed that the new revolutionary was a reality: The cinema that started to be made 25 years ago was a utopia, and now this cinema exists and has a continental dimension. (p. 97) Despite Birris optimism, today it is still difficult to talk of a national film industry in some countries of Latin America, and therefore more difficult to talk of a continental cinema. The presence of Hollywood films, not only in the theaters but especially in the common imaginary of people and filmmakers, is overwhelming. Names like Glauber Rocha, Jorge Sanjinés or Tomás Gutiérrez Alea are known only in certain circles connected with Academy and artistic production. Although filmmakers like Fernando Solanas, Fernando Birry, and Patricio Guzmán continue making movies, it is quite difficult to access them if one does not live in the country where they were produced. If the New Latin American Cinema failed as a cultural project, it was even more unsuccessful as social plan. Obviously the extreme poverty of many countries has not changed, and social inequality has grown in some regions. The guerrilla warfare has become established regimes or senseless struggles in which civilians are targets. This scenario would suggest a failure of the revolution in all its possible senses.

If one reads the project of the New Latin American Cinema as a future-oriented plan, as the promise of a new period in which the social conditions of Latin America will change, it would be possible to affirm its utopian character. However, we think although the multiple attempts of identification of arts and political practices, there will always be an irreducible difference. Cinema keeps an autonomy which allows it to be art and not simply a pamphlet used in the political struggle. All the new cinemas and in general the avant-garde movements in the twentieth century defended the idea of the artistic creation as a radical act of affirmation of the present. As Alain Badiou (2007) suggests, the ontological question of twentieth-century art is that of the present. (p. 135) In this sense, avant-garde cinema has always shifted between two simultaneous temporalities: the promise of a future and the absolute affirmation of the present. Why to promise a future if their intention was to affirm the present? Badiou explains this point using the case of manifestos: This rhetorical invention of a future which is on its way to existing in the shape of an act is a useful and even necessary thing, in politics and art as well as in love, where the I love you forever is the patently surrealist Manifesto of an uncertain act. (p. 139) As the love promise, art is not a contract but a rhetorical projection that allows us to reveal the active powers of the present. Love does not exist without an I love you forever just as avant-garde art does not exist without the promise of revolution. Like a circus ringmaster who presents during several minutes and with a hyperbolic language the acrobat jumps trying to call the attention of the public to an ephemeral moment, the avant-garde cinema highlights the consciousness of the present above all. The New Latin American Cinema never depicted a future time in its movies. The promise of this future was contained in the affirmation of the present.

We would like to read the utopian formulation of a new cinema as a call to think of the present instead as a failed future project. The dialectic of present and future was the core of the notion of revolution for the New Latin American filmmakers. Cinema was simultaneously and dialectically the promise and the realization of revolution.

References

Badiou, A. (2007). The Century. (A. Toscano, Trans.) Maiden: Polity Press. [ Links ]

Birri, F. (1997). For a Nationalist, Realist, Critical and Popular Cinema. In New Latin American Cinema (Vol. 1, pp. 95-98). Detroit: Wayne State University Press. [ Links ]

Birri, F. (1997a). Cinema and Underdevelopment. In M. Martin (Ed.), New Latin American Cinema (Vol. 1, pp. 86-94). Detroit: Wayne State University Press. [ Links ]

Blüthner, B. (1962). The Oberhausen Manifesto. Retrieved 2011 ??? 19-April from University of Victoria: http://web.uvic.ca/geru/439/oberhausen.html [ Links ]

Castro, F. (2001). History Will Absolve Me. Retrieved 2011 ??? 21-April from Marxist Archive: http://www.marxists.org/history/cuba/archive/castro/1953/10/16.htm [ Links ]

Craven, D. (2006). Art and Revolution in Latin America 1910-1990. New Haven and London: Yale University Press. [ Links ]

Eisenstein, S. (1958). A Dialectic Approach to Film Form. In S. Eisenstein, Film Form (J. Leyda, Trans., pp. 45-63). New York: Meridian Books. [ Links ]

Eisenstein, S. (1958). The Cinematographic Principle and the Ideogram. In S. Eisenstein, Film Form (J. Leyda, Trans., pp. 28-44). New York : Meridian Books. [ Links ]

Engels, F. (2000). Marx-Engels Correspondence 1890. Engels to C. Schmidt In Berlin. Retrieved 2011 ??? 23-April from Marxists Archive: http://www.marxists.org/archive/marx/works/1890/letters/90_08_05.htm [ Links ]

Engels, F. (2003). Socialism: Utopian and Scientific. Retrieved 2011 ??? 9-April from Marxist Internet Archive: http://www.marxists.org/archive/marx/works/1880/soc-utop/ch02.htm [ Links ]

García Espinosa, J. (1997). For an Imperfect Cinema. In M. Martin (Ed.), New Latin American Cinema (Vol. 1, pp. 71-82). Detroit: Wayne State University Press. [ Links ]

Guevara, E. (2005). Guerrilla warfare: A method. Retrieved 2011 ??? 23-April from Marxists Archive: http://www.marxists.org/archive/guevara/1963/09/guerrilla-warfare.htm [ Links ]

Gutiérrez Alea, T. (1997). The Viewer's Dialectic. In M. Martin (Ed.), New Latin American Cinema (Vol. 1, pp. 108-131). Detroit: Wayne State University Press. [ Links ]

Hegel, F. (1874). Part One of the Encyclopedia of Philosophical Sciences: The Logic. Retrieved 2011 ??? 8-April from Marxists Internet Archive: http://www.marxists.org/reference/archive/hegel/works/sl/sl_divis.htm [ Links ]

Lopes, J. (2004). El pasaje de las mitologías. In Glauber Rocha: del hambre al sueño. Buenos Aires: Malba. [ Links ]

López, A. M. (1997). An "Other" History. The New Latin American Cinema. In M. T. Martin, New Latin American Cinema (Vol. 1, pp. 135-156). Detroit: Wayne State University Press. [ Links ]

Marx, K. (1873). Capital. Volume One. Retrieved 2011 ??? 9-April from Marxist Internet Archive: http://www.marxists.org/archive/marx/works/1867-c1/p3.htm [ Links ]

Pereira dos Santos, N. (Writer), & Pereira dos Santos, N. (Director). (1963). Vidas Secas [Motion Picture]. Brazil. [ Links ]

Rocha, G. (Writer), & Rocha, G. (Director). (1967). Terra em Transe [Motion Picture]. Brazil. [ Links ]

Rocha, G. (1997). An Esthetic of Hunger. In M. Martin (Ed.), New Latin American Cinema (Vol. 1, pp. 59-61). Detroit: Wayne State University Press. [ Links ]

Rocha, G. (2003). Revisão crítica do cinema brasileiro. Sao Paulo: Cosac & Naify. [ Links ]

Rocha, G. (2004a). Glauber Rocha: del hambre al sueño. (P. Goldman, & A. Gangi, Eds.) Buenos Aires: Museo de Arte Latino Americano de Buenos Aires. [ Links ]

Rocha, G. (2004b). Revolução do cinema novo. Sao Paulo: Cosac & Naify. [ Links ]

Rocha, G. (2006a). Aesthetic of Dream. Retrieved 2011 ??? 23-April from Tempo Glauber: http://www.tempoglauber.com.br/english/t_esteticasonho.html [ Links ]

Rocha, G. (2006b). Eyzenstein e a Revolução Soviétyka. In G. Rocha, O Seculo do Cinema (pp. 161-170). Sao Paulo: Cosac & Naify. [ Links ]

Rocha, G. (2006c). Nouvelle-Vague. In G. Rocha, O Século do Cinema (pp. 301-336). Sao Paulo: Cosac & Naify. [ Links ]

Sanjinés, J. (1997). Problems of Form and Content in Revolutionary Cinema. In M. Martin (Ed.), New Latin American Cinema (Vol. 1, pp. 62-70). Detroit: Wayne University Press. [ Links ]

Solanas, F., & Getino, O. (1997). Towards a Third Cinema. In M. Martin (Ed.), New Latin American Cinema (Vol. 1, pp. 33-57). Detroit: Wayne State University. [ Links ]

NOTES

1 We are only reproducing here the names of the most visible figures of the movement. It would be necessary to make an account of all the minor filmmakers that traditional historical accounts have ignored. Given the main objective of this paper, we only include the names of the authors that published reflexive texts about cinema in Latin America.

2 Although it is possible to consider this problem of language as a rhetoric issue, we would like to approach it in a broader sense as a problem of representation. The difficulty of considering it only as a rhetoric matter is that the language is reduced to a means of transmitting ideas. A rhetorical analysis of revolutionary speeches and images is central to understand the mechanisms through which the idea of revolution was constructed and disseminated, but insufficient to comprehend the ontological relation between language and reality. To think of revolutionary language only as a means to convince, or even to manipulate, people implies to reduce it and to ignore the possibility of transforming reality through the change of representations.

3 Me critica dizendo que eu tenho mentalidade de produtor, depois me pede para ajudá-lo a destruir o cinema, aí eu digo para ele que estou em outra, que meu negócio é construir o cinema no Brasil e no Terceiro Mundo, então ele me pede para fazer um papel no filme e depois me pergunta se quero filmar um plano do Vento do Leste e eu que sou malandro e tenho desconfiômetro digo para ele maneirar pois estou ali apenas na paquera e não sou gaiato para me meter no folclore coletivo dos gigolôs do inesquecível Maio francês.