Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Acessos

Acessos

Links relacionados

-

Similares em

SciELO

Similares em

SciELO

Compartilhar

Observatorio (OBS*)

versão On-line ISSN 1646-5954

OBS* vol.7 no.3 Lisboa jun. 2013

Uses of democratic theory in media and communication studies

Kari Karppinen*

*University of Helsinki, Finland

ABSTRACT

It is commonly accepted that different theories of democracy imply different normative frameworks for evaluating media performance. However, it has also been argued that media and communication researchers engagement with broader political theories remains underdeveloped and dependent on a narrow range of sources. The aim of this article is to map out in a basic quantitative fashion how different models of democracy are employed in media and communication studies. Some broad theoretical trends and omissions in the current academic debate on media and democracy are identified by analyzing central theorists, trends and patterns in the theoretical resources employed in academic journal articles within the field. This is done by analysing the keywords and names that appear in the Communication & Mass Media Complete (CMMC) database from 1990 to 2011.

Keywords: democracy, democratic theories, normative theories, media and communication studies, bibliometrics

Introduction

The performance and role of media in society is routinely assessed against the ideal of democracy. There is a common understanding that media and communication systems play an important part in the working of democracy, and that this role should also somehow guide the work of media organizations and the public policies that shape the structures and conditions of media systems. Democracy, however, is not a unified concept that can be easily defined. Beyond the general idea of the rule of the people, democracy is an ambiguous and abstract value that can be used in a variety of different meanings and contexts.

In political theory, this ambiguity of democracy as a normative framework is manifest in the enduring debates on the different models of democracy and their normative underpinnings. The aim of this article is to map out – in a basic quantitative fashion – how these different models are employed in current media and communication studies and to identify some broad theoretical trends or omissions in the current academic debate on media and democracy.

Undoubtedly in much of media and communication studies, as in other fields, terms democracy or democratic are used simply as bywords for any desirable state of affairs, or to denote general questions about what the media should do in a good society. But if democracy is understood more analytically as a concept or a value to be defined, discussed and contested, we can assume that different normative theories of democracy – i.e. theories that seek to define the general principles and values of democracy – also imply different intellectual and normative frameworks for evaluating and criticizing the role and performance of different media in society.

The approach of the article is decidedly exploratory. Rather than advocate or criticize specific conceptions of democracy, the article provides a basic descriptive mapping of normative frameworks by identifying central theorists and some broad patterns in the theoretical resources that are actually employed in media and communication studies. This is done by analysing the keywords and names that appear in the Communication & Mass Media Complete (CMMC) database from 1990 to 2011.

The quantitative counting of theorists and keywords is unavoidably a very crude way to analyse the intellectual fashions of academic debate. However, the results do at least provide a tangible basis for further discussion on the theoretical biases and omissions in current media and communication studies. In the final part of the article, I also combine the analysis with my own observations of the literature to offer some more qualitative remarks about the dominant theoretical frameworks currently used in the field. Before analysing the results, I will briefly review some earlier debates on media researchers engagement with democratic theories.

Media studies engagement with political theory

While the ideal of democracy has always figured centrally in discussions about the media, there are differing views on the depth and scope of media scholars engagement with broader debates about the principles of democracy in social and political theory. The relationship between media and democracy is obviously one of the most debated issues in media studies, and there are also a number of theoretically informed and commonly cited works that have conceptualized this relationship from a variety of perspectives (e.g. Baker, 2002; Dahlgren, 2009; Christians et al, 2009; Curran, 2011; Garnham, 2000; Keane, 1991).

Many strands of both public and academic media criticism are based on either explicit or implicit criteria derived from different conceptions of democracy. There have also been attempts to operationalize the various normative demands derived from democratic theories into empirical criteria that can be used to evaluate or monitor how the media fulfill these democratic roles in different countries of contexts (e.g. Trappel, 2011).

In other words, both empirical analyses and theoretical critiques of media performance routinely rely on some normative theory or a model of ideal democracy as a normative basis. In this sense, the general idea that different models of democracy imply different roles and expectations for the media is quite uncontroversial and common. Evaluations of the quality and range of intellectual and theoretical resources that are actually employed in media and communication studies, however, have often been more critical.

It has been argued that media researchers engagement with broader social and political theory remains underdeveloped or that it depends on a narrow range of sources (Hesmondhalgh & Toynbee, 2008; Phelan & Dahlberg, 2011). According to Christians et al (2009), there is an ongoing need for stronger philosophical grounding of normative questions about the medias role in a democratic society.

Hesmondhalgh and Toynbee (2008, p. 9) argue that while media studies commonly draws attention to things that are wrong in the media, it tends to suffer from crypto-normativity, because contributions do not always make clear the theoretical and normative basis of their claims. Similarly, Strömbäck (2005, p. 331) argues that critics of journalism are often not clear enough about which democratic standards or models of democracy they apply when criticizing the media. To rectify this, it has been repeatedly argued that media studies needs richer intellectual resources and more serious engagement with social and political theory.

To put it even more bluntly, James Curran (2007, p. 34) argues that traditional theories of the democratic roles of the media that are reproduced in much of academic commentary as well as press editorials has become fossilized, anachronistic, pious, and in general disconnected from an understanding of how contemporary democracy works. Both Curran and John Keane (2009) have also noted that the role of the media should not be examined in isolation from other institutions and activities that take place in the civil society and political system. Instead, assessing the democratic roles of the media only makes sense in conjunction with analyzing other actors like social movements, think tanks, critical researchers, and political institutions themselves. To understand and make sense of these dynamics, media studies should engage more thoroughly with both empirical and theoretical work in other fields. In this sense, it can be argued that research on the role of media and communication tends to be somewhat isolated from broader questions and concerns in social sciences and political philosophy.

Common critiques involve the claim that media studies have been too media-centric, placing the media in the centre-stage as the central intermediary institution of liberal democracy. On the other hand, more theoretical debates are criticized for being confined to a narrow range of theoretical resources. A common argument here is that media studies have only selectively and fragmentarily engaged with broader theoretical and philosophical debates. As the results below also confirm, much of the research on media and democracy is based on standard readings of established theorists, such as Habermass work on the public sphere. More extensive engagement with contemporary debates in political philosophy and democratic theory are thus often deemed lacking.

The claims about under-developed theoretical resources, of course, do not apply only to theories of democracy. New intellectual resources can also be sought from many directions. In fact, many would claim that democratic theories, understood as some kind of coherent models or systems of thought, are more the source of fossilization than its cure, and that it is entirely elsewhere that media studies should turn their attention to. Undoubtedly, many are tempted to see democracy as discursive construction, or an empty signifier, rather than a subject of systematical theoretical idea.

Whether or not normative theories of democracy in political philosophy actually have anything useful to contribute to a better understanding of existing societies in general or media and communications in particular can be debated. The starting point of this article, however, is that various assumed or naturalized taxonomies of democratic theories can influence the terms of academic debates irrespective of their relationship to developments in the real world. Therefore it is useful to have a overview of their actual employment in the field.

The next top model of democracy

Political theorists have produced an abundance of different models of democracy that emphasise competing conceptualizations of its different component values and their proper relationship to each other. These different models can be deconstructed on multiple dimensions, such as their emphasis on the axes of liberty/equality, commonality/pluralism, participation/representation, or common good/proceduralism (e.g. Estlund, 2002; Held, 2006). No actually existing democracy corresponds to any one type of these theories, and different theories of democracy often overlap or simply focus on different aspects or levels of analysis so that they cannot be neatly divided into sharply delineated alternatives. Yet, it can be expected that these theories guide the questions, issues, concepts used also in debates on the role media for democracy.

Rather than categorizing and comparing models on the basis of existing political and media systems (e.g. Hallin & Mancini, 2004), this article is more concerned with the use of ideal models of democracy found in political philosophy, rather than the characteristics of actually existing democracies or media systems. Therefore, the analysis below will mainly focus on theorists and theories associated with the field of study known as democratic theory.

As normative, philosophical theories that seek to define the general principles and values of democracy, democratic theory can be defined narrowly as a specific subfield of social and political theory. However, even then, the corpus of democratic theory is obviously large and sprawling with a historical tail stretching back to the ancient Greece, or even beyond (Keane, 2009). In practice, democratic theory also takes place across a range of academic disciplines, including at least philosophy, political science, law, economics, and sociology (Estlund, 2002, p. 1). Furthermore, all relevant works on the principles of democracy would probably not even identify with the label of democratic theory.

Alternative ways of conceptualizing the key values of democracy, privileging some of them over others and developing their implications for the way in which the media should be organised are practically endless and they can be divided in a variety of ways – by school, the genealogy and history of their ideas, or according to political stance (see e.g. Estlund, 2002; Held, 2006; Keane, 2009, for some alternative ways of presenting the field). There would be no point in going over these theoretical debates or to try to synthesize their findings in any great detail here. Instead, I briefly highlight some common ways to distinguish different theoretical approaches and models of democracy before turning to analyze their appearance in journal articles within media and communication studies.

Typically, various models of democracy, derived from different philosophical traditions, include common phrases, such as representative, participatory, direct, and deliberative models of democracy that have become part of the common parlance in both media and communication and broader social sciences. These theories are divided and categorized into number of more or less coherent theoretical traditions. A broad division is often drawn, for instance, between the broad traditions of republican and liberal models of democracy. The former tradition is typically seen as more interested in the active, substantive role of citizens in the search for common good, while the latter is seen to emphasize individual liberties and more procedural aspects of democracy (e.g. Estlund, 2002; Held, 2006; Shapiro, 2005).

Very roughly outlined, the analysis and justification of democracy has changed from a broadly economic point of view of social choice or public choice schools of social science that flourished in the 50s and 60s to the ideals of participatory democracy in the 1970s to current debates under the banner of deliberative democracy, which many see as the dominant theoretical tradition since the 1990s (Estlund, 2002).

While notions such as deliberative democracy, or its variants such as discursive (Dryzek, 1990) or communicative democracy (Young, 2000) have remained popular, they have also fragmented into different strands. Deliberative tradition has also been heavily criticized by, among others, various poststructuralist political theorists (e.g. Mouffe, 2000). Yet others have noted a new representative turn that seeks to reinstate the value representation as essential to the working of mass democracy (Näsström, 2011). A number of scholars have also noted the inadequacy of the traditional models of democracy to propose their own models, such as complex democracy (Baker, 2007) or monitory democracy (Keane, 2009), which build on an eclectic combination of various strands of theories.

One key divide, which seems too much of the literature, is the division that has been drawn between deliberative and agonistic models of democracy. In particular, the division between the Habermasian deliberative democrats and the poststructuralist or postmodern approaches of theorists like Chantal Mouffe, Ernesto Laclau and William Connolly seems to have gained ground as one of the main dividing lines in contemporary debates on democratic theory (see Karppinen, Moe & Svensson, 2008).

Despite criticism that media scholars have poorly engaged with broader social and political theories, the idea that different conceptions of democracy underlie different approaches to the media and journalism seems to be quite widely adopted, and the implications of these most commonly invoked models of democracy for the role of the media have been developed by a number of scholars. (see e.g. Baker, 2002; Dahlberg, 2011; Christians et al, 2009; Curran, 2011; Strömbäck, 2006).

Normative Theories of the Media by Christians et al (2009, pp. 125-130), for instance, distinguishes between the liberal-pluralist, administrative-elitist, deliberative-civic, and popular-direct models of democracy. These are then associated with a group of familiar names including Robert Dahl (liberal), Joseph Schumpeter, Walter Lippmann (administrative), Jürgen Habermas, Joshua Cohen (deliberative), and Benjamin Barber (direct). These different models of democracy are then associated with the monitorial, facilitative, radical, and collaborative roles of the media, with each covering different requirements derived from different theoretical models of democracy. James Curran (2011, pp. 80-81) also ends up with a related categorization of liberal-pluralist, rational-choice, deliberative, and radical democracy, each of which is linked to different media regimes.

In addition to these more or less established theoretical traditions, there is increasing attention to more media-centric notions such as digital democracy or e-democracy. For some, the enthusiasm about the possibility of digital media technology enhancing democracy is another signal that media studies has grown more inward-looking and media-centric, more concerned with justifying which media elements or processes were key, while bigger question of the media in society, which the debate had begun with, becomes less important (Hesmondhalgh & Toynbee, 2008, p. 8).

Lincoln Dahlberg (2011), however, notes that there are also very different understanding of the form and models of democracy that digital media may promote. In his attempt to delineate the main positions of this debate, Dahlberg identifies liberal-individualist, deliberative, counter-publics, and autonomist Marxist understanding of digital democracy, with cyber-feminist, communitarian, cyber-libertarian and postmodern positions identified as other, less prominent, articulations of digital or e-democracy.

All in all, even a cursory overview reveals that there is a diversity of models of democracy applied in media studies, with different scholars developing their own versions of these categories and taxonomies. The list of models and categories and theorists, of course, goes on indefinitely and I make no pretence of covering them all here. Many of these banners, like deliberative democracy or participatory democracy also overlap to a great extent and they do not constitute any coherent or clearly delineable traditions. The placement of individual theorists or studies within these categories is inevitably also in part arbitrary. Yet, in all their indeterminacy I use the approaches as general entry points to illustrate the role of different theoretical assumptions in current media and communication research.

I do not claim that different models of democracy could be neatly isolated to extract some normative essence, which could then be used as an unambiguous yardstick for evaluating media performance. The idea here is not that any of these models of democracy would provide some kind of ready-made blueprints. Instead, all theories are seen here more as potential resources to engage with and as intellectual horizons that reveal something about normative presumptions in media and communication studies.

Method and data

There is a tradition of studies that assess the state of a particular research area by means of bibliometric analysis, i.e. by analyzing the descriptive records of published works (see de Bellis, 2009). This approach is, of course, not an alternative to more qualitative and interpretative work, and it does not contribute anything to a better understanding of the actual research object of the field. Instead, the broad aim of this kind of analysis is to illuminate some broad patterns in masses of publications and to identify some very general trends, gaps or weaknesses in the theoretical presuppositions of the field. The limitations of this kind of approaches are largely obvious. However, such analyses can at least provide a basis for more qualitative analyses and thus give further material for critical academic self-reflection.

In line with this tradition, the aim of the article is to provide a very basic mapping of the extent that different theorists and notions of democracy appear in the recent work done within media and communication studies. To provide a rough overview of the most popular theorists and theories, I have conducted a series of keyword searches in the EBSCOhost Communication & Mass Media Complete (CMMC) database1. In addition, some complementary searches were conducted in the general Social Science Citation Index2 to establish a baseline for comparing media and communication studies results to social sciences more generally. The CMMC database was chosen because it constituted the most comprehensive and representative source that I was able to access for uncovering broad trends specifically in media and communication studies.

To illuminate the dominant theories, theorists and conceptions of democracy used in the articles, a series of exploratory keyword searches was conducted to determine the frequency of occurrence of specific keywords, phrases and references to people in the articles. Searches included keywords, abstracts, full texts and the specific people category of the database. All searches were limited to the time period from 1990 to 2011. The focus on recent years intends to capture the most current research trends and also to keep the data more manageable. Historical analyses from 1990 to present were conducted with selected keywords to detect some trends and relative changes in the use of different theories. More comprehensive historical analyses, however, fall outside the scope of this article.3

The database itself is relatively comprehensive, but it is obvious that it does not include all work done within media and communication studies. The results are not exclusively limited to articles in English, but it does dominate the results.

Searches based on keywords or names of persons also involve a number of practical difficulties. Most importantly, the analysis does not take into account the way in which theories or people are discussed. The results include, for instance, occurrences where given theorists or theories are discussed critically, dismissed, or only mentioned in passing. When possible, I have tried to take into account different spellings of names, initials and keywords. All possible variations, however, are impossible to take into account so some inaccuracies inevitably remain. Similar limitations apply to keyword searches. Some phrases like participatory democracy have very indeterminate uses and can appear in various contexts as general phrases, while others like agonistic democracy have a much more specific scope of meaning confined to certain theorists. The keywords are thus not directly comparable and the interpretation of the results remains speculative.

Designing the search terms has involved multiple stages and a fair amount of experimentation with different keywords and search options, so the possibility that my own biases and existing knowledge have influenced the results cannot be ruled out. It is inevitable that others would also have thought of other relevant keywords and names to include so it is obvious that all results are suggestive only.

The choice of keywords and theorists that were searched is based on a combination of my previous reading and knowledge in the field, various reference books and lists of most cited theorists, and suggestions from readers who have commented on earlier versions of the article. Inevitably, the list is not all-inclusive – if not for other reasons, because of the indistinct boundaries of democratic theory as a field4. The results are thus only suggestive of theoretical trends, and they are intended to be used as a basis for a more qualitative and interpretative analysis rather than as objective ranking lists.5

Based on the searches conducted, a broad overview of the range and frequency of theoretical sources used in contemporary debates can still be formed. Given that a more qualitative analysis of the thousands of articles on media and democracy would be a daunting task, this kind of an overview is the best available means for producing a general mapping of the uses of different democratic theories in media and communication studies. In the following, I will first present the rough results of the bibliometric searches and then move on from there to discuss some of the issues that arise from the findings combined with my own observations about recent literature on media and democracy.

Conceptions of democracy in media and communication studies

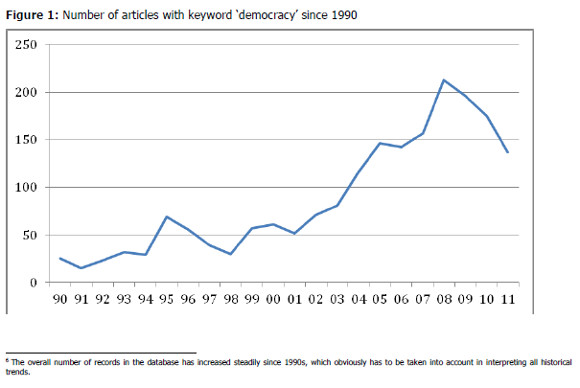

Despite the crudeness of the employed method, the analysis reveals some interesting observations that deserve further discussion. To give an idea of the number of articles that discuss the relationship between media and democracy, there were 2 531 results in the database for articles that include democracy in its title or keywords since the year 1990. The number of such articles has gone up from a low of 15 in 1991 to a high of 213 in 2008, showing steady growth even in relation to the overall number of records in the database (see figure 1)6. Thus, democracy clearly remains, and has become even more prominent, as one of the central topics and normative reference points in media and communication studies.

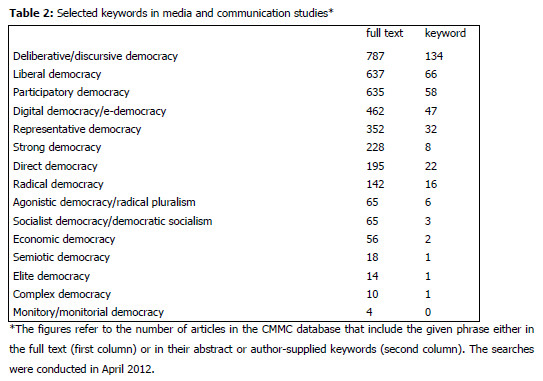

Regarding different models of democracy, it seems evident that the notion of deliberative democracy today constitutes a dominant paradigm for discussing the relationship between media and democracy (see table 2). Much attention in media and communication studies focuses on the role of media or other means of communication in promoting popular participation and public deliberation. Even though deliberative or discursive models of democracy are often still presented as challenging the dominant, hegemonic understanding of liberal representative democracy, at least in academic discussions in media and communication studies the deliberative model itself seems to have become the common reference point that needs to be acknowledged even by its critics.

There are most likely numerous reasons for this. The popularity of deliberative democracy as a theoretical framework in media and communication studies of course mirrors its emergence since the 1980s in political theory and social sciences more generally. On the other hand, it can be argued that the deliberative approach has become dominant not only because of the interest it has gained in political science and policy, but also because of the seeming elective affinity it has with communication and public debate (Dahlberg, 2011, p. 859). In a sense, the emphasis on public communication and debate implies a privileged position for the media as central democratic institutions. Deliberative and participatory models of democracy can thus be interpreted to reflect the aim in much of media and communication studies to deepen democratic practices beyond formal, representative institutions.

A quick search in the Social Science Citation Index confirms that while deliberative democracy is very widely used also in social sciences more generally, in relation to keywords such as representative democracy or liberal democracy it seems to have an exceptionally prominent place in media and communication studies7.

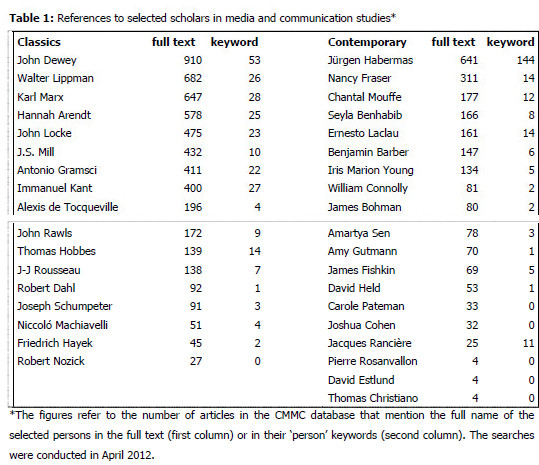

In terms of references to classic theorists of democracy, a number of names receive a fair number of references, but it is difficult to judge if these mostly include passing references or more sustained engagement with these theorists work. The search to determine the occurrences of these people in the article keywords reveals that at least half a dozen names have attracted enough attention to warrant articles to focus particularly on their work. Whether or not this contradicts claims about the underdeveloped nature of media and communication studies remains to be speculated.

Interestingly, John Deweys position as a leading figure also corresponds with the dominant position of the deliberative democratic framework in a sense that he is often mentioned as a predecessor or source of inspiration for current theories of deliberative and participatory democracy (see, e.g. Barber, 1984; Bohman, 2000; Dryzek, 2000). The prominence of Dewey and Walter Lippmann is also undoubtedly explained by the status of Dewey-Lippmann debate as basic stuff of journalism textbooks, so references to these names does not necessarily indicate especially deep scrutiny of these theorists. Interestingly, other 20th century American theorists of democracy such as John Rawls and Robert Dahl have received much less attention.

In terms of contemporary theorists, Jürgen Habermas is unsurprisingly a dominant figure. What is interesting is that aside from actual citations or articles that discuss his work in detail, the term Habermasian seems to have become an expression that does not even need to be defined or explained. The term appears 454 times in the articles since 1990 (with 426 of those since 2000), which is more than any individual name and as a general identifier second only to Marxist8 . This seems to suggest that especially in recent decades the term has gained an implicit meaning and can be used as a short-hand reference for things like rational discussion and the public sphere without even citing the relevant works. The status of Habermas as the main man of consecutive generations of media scholars is thus hardly in question, even if he may be used today more as an almost half-fictional reference point than as an actual discussion partner.

Whether of not these references actually reflect the work of Habermas or if there are aspects that have been overlooked in media and communication studies is beyond the scope of this article (see Karppinen, Moe & Svensson, 2008). At least to some extent, however, this seems to reflect Hesmondhalgh and Toynbees observations about the narrow uses of social theory. Hesmondhalgh and Toynbee (2008) argue that although various theorists have been mobilized in media and communication studies, only a single aspect of their work is typically taken up. Theorists are appropriated for particular concepts and problems, such as Habermas for the idea of the public sphere, which are then either employed or dismissed based on a very small part of his work. The same is undoubtedly true for different theories. Mouffe may be similarly appropriated for her critique of Habermas or the idea of agonistic democracy or Nancy Fraser for subaltern counter-publics. In each case, concepts can be adopted without any systematic engagement of the underlying fundamental principles underlying these theorists work. Again, whether this reflects healthy theoretical eclecticism (Karppinen et al, 2008) or peculiar narrowness (Hesmondhalg & Toynbee, 2008) remains to be debated.

Beyond Habermas, the cast of most popular democratic theorists is fairly familiar, including Nancy Fraser, Seyla Benhabib and Iris Marion Young, all broadly associated with the debates around the deliberative paradigm. On the other hand, critical interrogations of the public sphere theory and especially post-structuralist political theories that reject the Habermasian framework of deliberative democracy have also gained a relatively strong following in media and communication studies. Of theorists that are clearly critical of the Habermasian tradition, Chantal Mouffe and Ernesto Laclau and their theories of radical and plural democracy seem to have generated a fairly stable following also in media studies. Other notable poststructuralist political theorists, such as William Connolly, however, seem to have attracted much less interest in media and communication studies.

As a hypothesis, it can also be assumed that particular conceptions of democracy, including relevant theorists, concepts and phrases, correspond to certain disciplinary subfields or topics of study. Peter Dahlgren (2009), for instance, identifies three traditions in debates on media and democracy: political communication studies, public sphere theory, and the culturalist tradition. Each of which tends to engage with different kinds of theory: political communication with formal political institutions and representative democracy, the public sphere approach with deliberative democracy, and the culturalist perspectives with poststructuralist political theory.

It has also been noted earlier that the public sphere approach has been adopted in studies that employ critical political economy and in discussions on public service broadcasting, for instance, while theoretical insights from poststructuralist democratic theories of Laclau and Mouffe resonate with cultural studies interest in discourse and representations (see Karppinen et al, 2008; Phelan & Dahlberg, 2011, p. 7). Similarly, it can be speculated that notions like participatory democracy or direct democracy have found much new use in debates on new media technologies, social media, and their participatory potential.

Then what about alternative intellectual resources or new ways of conceptualizing democracy? Based on the data, many of the main figures in current debates in democratic theory like David Estlund or Thomas Christiano are virtually absent in media and communication studies texts. References to Pierre Rosanvallon and the notion of counter-democracy, or the notion of complex democracy or monitory democracy are also almost completely missing in the articles. In part, the slow reception of some new ideas can be explained by the long cycle of academic journal publishing. Yet, the relative absence of more contemporary ideas in democratic theory seems to confirm at least some lack of vitality in the use of theoretical resources.

Overall, the theoretical resources used in media and communication studies reflect fashions in democratic theory and social science discourse in general. However, some approaches are adopted more readily in media studies, while others remain marginal. Theoretical fashions also do not always ebb and flow simultaneous in different disciplines, but new theories are often adopted with delay.

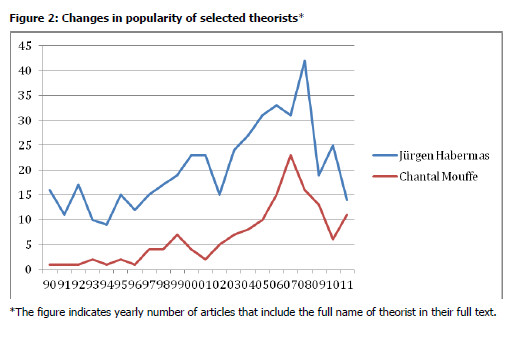

The methods used here can also be used to identify some rough trends or changes in the relative popularity of different theorists. Figure 2, for instance, shows a comparison of Habermas and Mouffe. The figure indicates not only an increasing attention to Mouffe, but also a strong resemblance between the lines, which seems to indicate that these theorists are often discussed together in same articles.

Conclusion

In this article, I have applied a rough method of mapping dominant theorists and theoretical keywords in the debate on media and democracy to assess trends and patterns in the use of different democratic theories and conceptual frameworks. As I have emphasized, the method used is necessarily crude and there are some obvious limitations to the method of quantitatively counting key words and phrases that appear in journal articles.

Although the field of media and communication studies in general is theoretically quite diverse and eclectic, one of the initial claims that this article seeks to test is that current research on media and democracy is focused on a relatively narrow range of theoretical sources, while many theorists in political philosophy and democratic theory are virtually unknown in media and communication studies. To some extent, the results confirm that much of the discussion revolves around a broadly Habermasian conceptions of democracy, even if some of his critics have also received a fair amount of attention. While the dominance of Habermas and the framework of deliberative democracy is hardly surprising, there is also some support also for the claim about the relative dearth of engagement with more contemporary critical political theories in media and communication studies.

All in all, it is in the nature of democracy – as an essentially contested concept – that existing conceptual categories and theoretical understandings are always subject to contestation. New models are juxtaposed against earlier dominant models of democracy. And emphasized before, these models do not constitute any clearly delineated recipes that can be readily applied. It needs to be noted that results presented here do not provide any information on whether discussions of Habermas, for example, have turned more critical recently.

Interpretation of the results is thus open to many different conclusions. However, even as a crude overview, they can provide a basis for further more qualitative analysis. Also, other researchers are free to utilize and develop similar methods to shed light on further trends or to provide a more detailed picture of the use of different theorists in different sub-fields, for instance. Possible future research topics could include, for example, relationships between different theorists and associations between certain models of democracy and subfields or thematic areas. Many of these issues have only been speculated on in this article, but other researchers are free to take it from here.

One of the main objectives behind this article has been to help bridge the gap between current media studies and broader debates on political theory. Making the theoretical assumptions and underpinnings of the current debates more visible and thus open to critical assessment is one way of doing that. Besides the assessment of the different theoretical frameworks, another challenge for future research is, of course, mapping new, alternative theoretical frameworks for conceptualizing the democratic roles of the media.

References

Baker, E. C. (2002). Media, Markets, and Democracy. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

Baker, E. C. (2007). Media Concentration and Democracy. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

Barber, B. (1984). Strong Democracy. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press. [ Links ]

Bohman, J. (2000). Public Deliberation: Pluralism, Complexity, and Democracy. Cambridge, Mass: MIT Press. [ Links ]

Christians, C. G., T. L. Glasser, D. McQuail, K. Nordenstreng and R. A. White (2009). Normative Theories of the Media. Urbana and Chicago: University of Illinois Press. [ Links ]

Curran, J. (2007). Reinterpreting the Democratic Roles of the Media. Brazilian Journalism Research, 3(1), 31-54. [ Links ]

Curran, J. (2011). Media and Democracy. London: Routledge. [ Links ]

Dahlberg, L. (2011). Re-constructing Digital Democracy: An Outline of Four Positions. New Media & Society, 13(6), 855-872. [ Links ]

Dahlgren, P. (2009). Media and Political Engagement: Citizens, Communication, and Democracy. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

De Bellis, N. (2009). Bibliometrics and Citation Analysis. Lanham: Scarecrow Press. [ Links ]

Dryzek, J. (2000). Discursive Democracy: Politics, Policy, and Political Science. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

Estlund, D. (2002). Introduction. In D. Estlund (ed.), Democracy (pp. 1-28). Oxford: Blackwell. [ Links ]

Garnham, N. (2000). Emancipation, the Media, and Modernity. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

Hallin, D. and P. Mancini (2004). Comparing Media Systems. Three Models of Media and Politics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

Held, D. (2006). Models of Democracy. London: Polity Press. [ Links ]

Hesmondhalgh, D. and J. Toynbee (2008). Why Media Studies Needs Better Social Theory. . In D. Hesmodnhalgh and J. Toynbee (Eds.), Media and Social Theory (pp. 1-24). London: Routledge. [ Links ]

Karppinen, K., H. Moe and J. Svensson (2008). Habermas, Mouffe and Political Communication. A Case for Theoretical Eclecticism. Javnost, 15(3), 5-22. [ Links ]

Keane, J. (1991). Media and Democracy. Cambridge: Polity Press. [ Links ]

Keane, J. (2009). The Life and Death of Democracy. London: Simon & Schuster. [ Links ]

Mouffe, C. (2000). The Democratic Paradox. London: Verso. [ Links ]

Näsström, S. (2011). Where is the representative turn going? European Journal of Political Theory, 10(4), 501–510. [ Links ]

Phelan, S. and L. Dahlberg (2011). Discourse Theory and Critical Media Politics: An Introduction. In S. Phelan and L. Dahlberg (Eds.), Discourse Theory and Critical Media Politics (pp. 1-40). Basingstoke: Palgrave McMillan. [ Links ]

Shapiro, I. (2005). The State of Democratic Theory. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. [ Links ]

Strömbäck, J. (2006). In Search of a Standard: Four Models of Democracy and Their Normative Implications for Journalism. Journalism Studies, 6(3), 331-345. [ Links ]

Trappel, J. (2011). Why Democracy Needs Media Monitoring. In J. Trappel, H. Nieminen and L. Nord (Eds.), The Media for Democracy Monitor: A Cross National Study of Leading News Media (pp. 11-28). Göteborg: Nordicom. [ Links ]

Young, I. M. (2000). Inclusion and Democracy. Oxford: Oxford University Press [ Links ]

NOTES

1 CMMC claims to offer indexing and abstracts for more than 570 journals, and selected coverage of nearly 200 more, for a combined coverage of more than 770 titles, including full text for over 450 journals in the areas related to communication, mass media, and other closely-related fields of study. See http://www.ebscohost.com/academic/communication-mass-media-complete.

2 http://thomsonreuters.com/products_services/science/science_products/a-z/social_sciences_citation_index/

3 Before 1990, the coverage of the database declines significantly so it is not suitable for longer historical analyses. The database also does not cover comprehensively the most recent years (2011-2012).

4 For example, many classic sociologists, such as Weber, Foucault, Bourdieu, who are not primarily thought of as democratic theorists have been excluded in the tables, even though they undoubtedly have had an enormous influence in media and communication studies. Other such borderline cases are countless, so the tables below should not be read as some kind of official ranking lists of most influential theorists.

5 It should also be noted that the method used here is open so that anyone with access to these databases can easily conduct further searches with other keywords and search terms to reveal further trends and patters. The results presented in the tables below thus represent only some examples of the kind of information that can be obtained with this method.

6 The overall number of records in the database has increased steadily since 1990s, which obviously has to be taken into account in interpreting all historical trends.

7 An article topic search in SSCI gives 691 results for liberal democracy, 663 for deliberative democracy and 446 for representative democracy

8 Marxist appears a whopping 2 091 times in all of the texts but it is fair to guess that in most cases it used very casually as a general catchword rather than as a serious analytical term.