Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Acessos

Acessos

Links relacionados

-

Similares em

SciELO

Similares em

SciELO

Compartilhar

Acta Obstétrica e Ginecológica Portuguesa

versão impressa ISSN 1646-5830

Acta Obstet Ginecol Port vol.10 no.1 Coimbra mar. 2016

ORIGINAL STUDY/ESTUDO ORIGINAL

Complications of laparoscopic sacropexy: as harmless as they seem?

Complicações da sacropexia laparoscópica: serão assim tão inofensivas?

Sara Campos*, Valentina Billone*, Marta Durão**, Marie Beguinot*, Nicolas Bourdel*, Benoît Rabischong***, Michel Canis***, Revaz Botchorishvili*

Department of Gynecological Surgery

Centre Hospitalier Universitaire de Clermont-Ferrand - CHU Estaing Clermont-Ferrand, France

*MD, Department of Gynaecological Surgery, Centre Hospitalier Universitaire de Clermont-Ferrand,

**MD, Centro Hospitalar do Oeste

***MD, PhD, Department of Gynaecological Surgery, Centre Hospitalier Universitaire de Clermont-Ferrand,

Endereço para correspondência | Dirección para correspondencia | Correspondence

ABSTRACT

Overview and aims: To analyze all patients needing surgical treatment for complications related to laparoscopic sacropexy and their clinical management.

Study Design: Case series.

Population: All women submitted to surgical treatment of complications related to laparoscopic sacropexy for pelvic organ prolapse treatment on a tertiary referral center (university hospital), from January 1998 to December 2013.

Methods: Retrospective analysis of the patients' clinical records.

Results: Thirty-three patients were submitted to surgery due to complications related to the procedure, some more than once, with more than one complication registered. There were 6 general surgical complications (2 hematomas, 2 peritonitis, 1 mechanical bowel obstruction due to small bowel incarceration and 1 vaginal wall necrosis) and 34 mesh related complications (27 vaginal mesh exposures, 4 periprosthetic abscesses, 1 vesicovaginal fistula, 1 rectovaginal fistula and 1 posterior mesh retraction). Mean time between prolapse surgery and the first surgery for complication treatment was 18.2 ± 25.3 months (3 days - 131 months). The average number of surgeries needed was 1.8 ± 1.5(1- 6).

Conclusions: Surgeons should be aware of the risk factors for complications. Longterm complications should not be neglected. After a mesh placement, patients are at risk for requiring multiple surgeries to resolve complications, which can be challenging, ineffective and expose patient to new ones.

Keywords: Sacropexy; Complications; Prolapse; Mesh; Laparoscopy.

Introduction

Abdominal sacrocolpopexy (ASC) has been shown to be more effective than a vaginal approach surgery on the treatment of apical vaginal prolapse1,2, with reported longterm success rates of 68-100%3. Furthermore, it also allows simultaneous treatment of other compartment defects4. Laparoscopic sacropexy avoids the need for a large abdominal incision and minimizes bowel manipulation, potentially leading to less postoperative pain and shorter recovery time5.

The use of synthetic mesh, while essential for the success rate, is associated to a complication unique to this kind of repair: the possibility of erosion through adjacent tissue. Mesh erosion rates after sacrocolpopexy range from 2% to 10% according to literature6-9, with a wide range of consequences. Despite the widespread concern about mesh related complications, their treatment is not extensively discussed.

Risk factors associated with mesh erosions include smoking7, prior surgical scarring10, oestrogen deficiency11, concomitant hysterectomy7, mesh type12 and a transvaginal placement of the mesh13.

Mesh erosion is one of the most worrisome complications related to sacrocolpopexy, especially because of the impact on quality of life. However, a series of other complications may be associated to this procedure.

Complications of sacropexy may be broadly divided in two main groups8:

• general surgical complications (procedure or surgeon-based) - related to surgical technique, as dissection or haemostasis; although not related to the mesh itself, they can influence surgery outcome.

• mesh-related complications (product-based) - directly attributed to the presence of mesh inside the patient’s body.

The purpose of this study is to alert to possible complications after laparoscopic sacropexy, as well as treatment options, by analysing all cases of patients who needed surgical treatment of complications after laparoscopic sacropexy in our department. At the same time, other surgery-related complications are described, with the aim of alerting surgeons to their occurrence, and therefore contributing to their prevention.

Methods

After receiving institutional review board approval, a retrospective analysis of electronic medical records was performed for all patients who underwent surgical treatment for Grade III-b complications (according to Clavien-Dindo Grading System for the Classification of Surgical Complications14) after sacropexy (sacrocervicopexy, sacrocolpopexy or sacrohysteropexy) with mesh to treat pelvic organ prolapse by laparoscopic approach, from January 1998 to December 2013. Sacropexies were performed by 5 different experienced laparoscopic surgeons. Only complications treated in our institution were considered.

Medical records of these patients were retrieved to collect clinical data (BMI, menopausal status, hormonal replacement therapy (HRT) usage, topical oestrogens usage, prior hysterectomy, smoking), and operative details were abstracted (concomitant hysterectomy - total or subtotal -, type of mesh used, fixation technique, peritonization, perioperative antibiotic prophylaxis), along with complications and its management. Type of complications, clinical presentation, delay before surgical management, initial and eventual subsequent approaches and postoperative data were assessed.

Results

A total of 1238 sacropexies were performed between January 1998 and December 2013, in our Department. Mean follow-up time was 41.3 months, with 16 patients lost to follow-up.

A total of 33 patients (2.7%) had a Grade III-b complication (N = 33).

NOTE: Women for whom data on any field were not recorded were excluded from the descriptive analysis of the respective parameter. Ratios (n/N) and percentages (%) are presented according to available data.

Patients’ characteristics

Mean age was 52.0 ± 8.3 (42-75) years.

There were 2/28 (7.1%) obese patients, and 9/28 (32%) were overweight. Mean body index mass was 24.1 ± 3.5 (18-32) Kg.m-2. Most of the patients (24/33) were postmenopausal (72.7%), and 13/24 (54.2%) were using systemic hormonal replacement treatment. Six out of 31 (19.4%) had current smoking habits.

Fourteen out of 33 (42.4%) had undergone a previous hysterectomy (total abdominal hysterectomy in 7 patients, total laparoscopic hysterectomy in 6 and subtotal laparoscopic hysterectomy in 1).

Intraoperative relevant findings/incidents

In surgical reports, 4/33 (12.1%) cases of through-and-through vaginal stitches were found. This fact was noticed intraoperatively and immediately corrected, either by replacing the suture laparoscopically or by vaginally cutting the visible suture. Two cases of difficult vesicovaginal dissection were reported, as well as 2 cases of adhesions between the sigmoid and the vaginal vault before the beginning of the procedure, 2 cases of uterine perforation at the time of cannulation and 1 pelvic endometriosis).

Complications

Complications are presented in Table I.

There were 6 general surgical complications (2 haematomas, 2 peritonitis, 1 mechanical bowel obstruction and 1 vaginal wall necrosis); and 34 mesh related complications (27 vaginal mesh exposures, 4 periprosthetic abscesses, 1 vesicovaginal fistula, 1 rectovaginal fistula and 1 symptomatic mesh retraction). When accessing the interval of time to diagnosis, 8 early postoperative complications (during the first month) were reported (2 peritonitis, 2 haematomas, 1 mechanical bowel obstruction, 1 vesicovaginal fistula, 1 vaginal wall necrosis, 1 vaginal mesh exposure) along with 32 late postoperative complications (diagnosed more than one month after surgery) (26 vaginal mesh exposures, 4 periprosthetic abscesses, 1 rectovaginal fistula and 1 symptomatic mesh retraction).

Clinical presentation

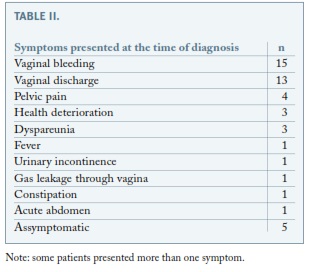

Clinical presentations are presented in Table II.

Management of complications

Mean time between prolapse and first surgery for complication treatment was 18.2 ± 25.3 months (3 days-131 months). A mean of 1.8 ± 1.5 (1-6) surgeries were needed for complication management, with eleven patients having more than one procedure. Considering only these 11 patients, the mean time between the prolapse surgery and the last surgery for complication resolution was 64.7 ± 49.1 (2-162) months, and the mean number of surgeries 3.4 ± 1.6 (2-6).

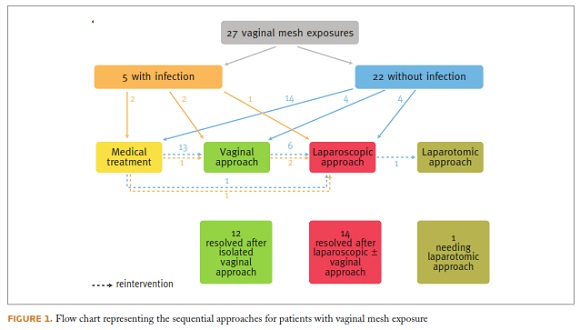

Twenty-two out of 27 patients (81.5%) had a pure non-infected vaginal mesh exposure. In 14/22 (63.6%) patients, an initial medical treatment was attempted (with topical oestrogens and antiseptics), though unsuccessful, with persistence of mesh exposure. For 13/14 (92.9%) patients, a vaginal approach was the next step, with exposed mesh removal and vaginal wall resuture. Among these patients, 5/12 (41.7%) needed a subsequent laparoscopic approach, due to persistent exposure; 4/5 with superimposed infection. At the end, of those 22 patients initially diagnosed with non-infected vaginal mesh exposure, 11 patients (50%) had the vaginal mesh exposure resolved after vaginal surgery, while 10 patients (45.5%) needed at least one laparoscopic surgery and 1 patient (4.5%) needed a laparotomy, due to heavy bleeding during mesh removal, and difficulties in the identification of anatomical structures. A total of 6 local infections were posteriorly diagnosed among the patients initially diagnosed with vaginal mesh exposure without associated infection.

The remaining 5/27 patients (18.5%) presented a vaginal mesh exposure with concomitant signs of local infection at the time of diagnosis (vaginal malodorous discharge, vaginal wall erythema). Two out of these 5 patients were initially treated with topical treatment, 2 with a vaginal approach and only 1 with an initial laparoscopic approach. At the end, just a single patient had its complication resolved after vaginal surgery; all the remaining needed, at least, one laparoscopic surgery (Figure 1).

The initial approach for fistulas (vesicovaginal and rectovaginal), cases of peritonitis or periprosthetic abscesses, bowel incarceration, haematomas, and mesh retraction, was laparoscopic; the same applied to cases of vaginal wall necrosis without mesh exposure.

Whenever a laparoscopic approach was performed, partial or total mesh removal was carried out (21/33 patients; 63.6%). Total mesh removal was attempted in all cases of concomitant infection. Five patients needed subsequent surgeries to remove remaining mesh pieces causing persistent infection.

Two patients also needed subsequent laparoscopies to resolve complications related to the mesh removal (one partial necrosis of the right ureter, needing reimplantation, and one haematoma of the right pararectal fossa).

All patients with suspected or confirmed infection were studied with abdominal CT or MRI, searching for eventual abscess collection or spondylodiscitis. No cases of spondylodiscitis were found.

Discussion

Pelvic organ prolapse (POP) is common and seen on examination in 40% to 60% of parous women, potentially diminishing their quality of life15, 16. In the United States, the updated lifetime risk of undergoing prolapse surgery is 12.6%17.

According to a recent Cochrane review1, sacrocolpopexy was associated with a lower rate of recurrent vault prolapse on examination and painful intercourse than sacrospinous suspension, and a higher success rate and lower reoperation rate than high vaginal uterosacral suspension and transvaginal polypropylene mesh. A recent publication actually states ASC as the most effective treatment for apical vaginal prolapse2, with reported longterm success rates of 68-100%3. Plus, an abdominal approach allows a simultaneous correction of the three pelvic floor compartments defects: anterior, apical and posterior, preserving vaginal integrity. The laparoscopic approach represents an alternative to open surgery, with comparable outcomes, while benefitting patients with the well-recognized advantages of minimally invasive surgery2. The characteristics of this completely minimally invasive surgery, as well as its potential benefits for sexual function (preservation of vaginal length and axis and lower rates of dyspareunia), make this procedure a better option for younger, sexually active women18.

Being the main responsible for the effectiveness and durability of the procedure, the use of synthetic mesh carries, nevertheless, a set of possible related complications, unique to this procedure. Those complications frequently require surgical treatment. A reoperation is not necessarily related to mesh placement; it can be secondary to dissection, which is necessarily wider for abdominal mesh placement, comparing to vaginal approach. The rate of type III-b complications according to the Dindo classification14 seems to be higher after vaginal than abdominal mesh insertion (7% vs 4.8%)6. Understanding the subjacent mechanisms of mesh complications should help us to reduce their occurrence.

Before discussing mesh-related complications, general surgical complications will be considered. The distinction between general surgical complications vs mesh related complications seems reasonable and facilitative of complication analysis. The first group will be mandatorily specific to the abdominal approach, needing transperitoneal dissection, and thus required to be considered separately from mesh related complications.

Two cases of peritonitis occurred, both reoperated on day 3. In both patients previous abdominal hysterectomy and need for adhesiolysis was reported, which may have contributed to unnoticed bowel injury during dissection. In a study focusing on gastrointestinal complications of laparoscopic sacrocolpopexy, Warner et al. report a rate of 1.3% for intraoperative bowel injury19. Surprisingly, prior abdominal surgery was positively associated with functional gastrointestinal complications, but not with bowel injury. Nonetheless, it is prudent to consider that those patients that present with previous surgeries, particularly total abdominal hysterectomy, and with multiple adhesions, mainly at vaginal cuff level, have an increased risk for bowel injury at the time laparoscopic sacropexy.

Simultaneously, the risk of vaginal wall necrosis may also be increased. The increased fragility of vaginal wall after dissection (always difficult in these cases), aligned with excessive bipolar coagulation, may explain this. Preoperative local oestrogen treatment should be considered, especially in these patients, as it is proved that increases vaginal wall thickness11.

Two patients presented early haematomas. One patient was diagnosed with vaginal suture exposure (later complicated by infection) more than 8 years after the index surgery, and the other patient presented a subsequent periprosthetic abscess, both demanding complete mesh removal, achieved laparoscopically. The overall median rate of bleeding complications was described by Nygaard as 4.4%3. The presence of a haematoma had already been described as a potential risk factor for mesh erosion19.

A patient needed a laparoscopy on day 3 due to a small bowel incarcerated hernia in the Retzius space, dissected for a paravaginal defect repair. The incomplete closure of the space at the end of the paravaginal repair was the probable mechanism behind bowel incarceration. Later, the patient also presented a vaginal mesh exposure.

Mesh erosion is a wellknown complication of using synthetic mesh. Erosions may be asymptomatic and inconsequential or they may present with severe infection or result in fistula. The analysis of the prevalence and identification of risk factors among the patients with vaginal mesh erosion is beyond the scope of this study, which intends to describe complications and its management. Nevertheless, an overview of Table I allows us to quickly notice that at least one of the literature reported risk factors for mesh erosion was present in every single patient who hereafter presented this complication (previous or concomitant total laparoscopic hysterectomy, through-and-through vaginal stitch, uterine perforation, difficult dissection for pelvic adhesions).

In the CARE trial, concomitant total hysterectomy was considered a modifiable risk factor for mesh erosion after sacrocolpopexy7. Also Warner et al. related open-cuff hysterectomy to a significantly higher rate of mesh erosion, compared to supracervical hysterectomy (4.9% vs. 0%, p=0.032)21. De Tayrac et al. reported an even higher risk when concomitant total hysterectomy was performed (8.6%). Nonetheless, according to the same study, even a previous hysterectomy was related to an increased risk of vaginal mesh exposure (2.2%), followed by supracervical hysterectomy (1.7%) and hysteropexy (1.5%)22. Also according to our experience, supracervical hysterectomy did not completely abolished the risk of mesh exposure, since half of the patients who presented mesh exposure had been submitted to supracervical hysterectomy, without the need for vaginal opening.

Four of the patients who later presented vaginal mesh exposure had already an exposed vaginal suture, identified 1 month after the surgery, during follow-up consultation. An exposed vaginal suture may be considered a precursor or, at least, a sentinel, for future mesh exposure, mainly if polyester sutures are used, as it has been described that a delayed absorbable, monofilament suture appears to reduce the risk of mesh/suture erosion23.

Synthetic glue was also used, in 2011. Unfortunately, mesh erosion also occurred. To the best of our knowledge, there are inconclusive data in literature to support the use of synthetic glue. This type of fixation was tried, hypothesizing that it would diminish the risk of infection, by eliminating the risk of through-and-through vaginal stitches, but it became quickly evident that a “new” type of complication was emerging. Three of the patient presented mesh exposure with no associated infection, probably an immune reaction to a foreign body, as described by one of the hypothesis of de Tayrac20. According to this author, mesh erosion may result from a combination of bacterial infection and devascularization of the vaginal wall. De Tayrac describes 3 hypothesis to explain mesh-related complications, such as erosion, shrinkage or pain: an immune reaction to a foreign body; a prolonged inflammatory response (oxidative attack); a chronic infection. According to this paper, biomaterial implantation is followed immediately by a “race for the surface”, a contest between tissue cell integration and bacterial adhesion to that same surface that the bacteria win. The surface is occupied and is thus less available for tissue integration. In a study performed by Boulanger et al.24 bacterial contamination was found in all meshes removed for complications after surgical management of urinary incontinence or pelvic organ prolapse, and even if quantification was often low, its exact role is not yet clear. Vollebregt et al. also described as much as 83.6% of colonized vaginal implanted meshes25. This colonization justifies the systematic antibiotic prophylaxis, respected in most of the patients of this series. Nonetheless, this measure was not sufficient to prevent the cases of mesh exposure and/or infection.

Concerning infected meshes, two scenarios may occur: a localized infection, limited to the vaginal wall, or retroperitoneal extension of the infection up to the abdominal cavity, frequently causing a periprosthetic abscess. In both scenarios, the most reasonable one is that the mesh is infected at the time of its placement, as described above. In the first case, and if polypropylene mesh was used, a partial transvaginal removal of the mesh may be attempted. In the second scenario, complete removal of the infected mesh is required, especially if multifilament polyester mesh was used. Polyester mesh was used in 17/32 (53.1%) patients, especially in the beginning of our study. It is interesting to remark that in patients who presented longer intervals between surgery and diagnosis of periprosthetic abscesses, a polyester mesh had been used. Two occurred after haematomas and 1 after uterine perforation.

More frequent was the diagnosis of vaginal mesh exposure with no associated infection, which presented in most cases as vaginal bleeding or vaginal discharge (Table II). A conservative treatment for this condition was initially attempted in 14 patients (with topical oestrogens and antiseptic agents) with disappointing results, all of them needing subsequent surgical treatment. Transvaginal surgical excision and transvaginal endoscopic technique may be the next step26, with partial removal of the exposed mesh. When insufficient, an ulterior laparoscopic approach is required. In 6 of the patients to whom a conservative or initial vaginal approach was tried, an infection was subsequently diagnosed. They probably experienced a chronic subclinical infection, with the creation of a bacterial biofilm, which allowed bacteria to remain quiescent during the initial period18. An intercurrent event, such as persistent exposition to the vaginal environment, may have contributed to bacterial multiplication and clinical infection. The fact that postoperative topic oestrogens were initially prescribed to only half of the patients may have contributed to the development of vaginal mesh exposure11. Five occurred in patients with polyester meshes, which supports the use of a macroporous, monofilament, soft polypropylene, type I mesh27, and that conservative vaginal treatment should only be attempted in cases of polypropylene meshes, particularly in cases of small abscesses or asymptomatic patients. Nonetheless, our experience has shown that conservative treatment is rarely sufficient. An infected mesh should be completely removed, especially in case of deep infection and/or a polyester mesh. The particularity of the attachment to the promontory makes it mandatory to proceed with extreme care, because of the risk of spondylodiscitis.

Figure 1 presents the treatment for vaginal mesh exposures. It demonstrates the frequent need for several reinterventions, certainly affecting these patients quality of life. An initial less invasive treatment should be always balanced with the risk of reintervention. This is especially important when, as recently reinforced by a Chamsy and Lee publication28, “laparoscopic excision procedures of sacrocolpopexy mesh are typically challenging, even in the hands of experienced surgeons”.

Late exposure occurrence should not be neglected. Our series reports cases of a vaginal mesh exposure diagnosed 8 years after prolapse surgery, and Nygaard at al29 recently reinforced the importance of a long follow-up.

The only case of mesh retraction was on patient 8, who presented severe constipation, needing a surgical approach 9 months after the initial surgery. At the time, no evident mesh retraction was noticed but a marked fibrosis of the uterosacral ligaments was perceived. That under tension area was surgically released. Two years later, the patient was reoperated for a posterior mesh retraction evident at vaginal examination, persistent constipation and vaginal exposure.

Other relevant question addresses the treatment of recurrences after complete mesh removal. In our series, 2 patients needed subsequent surgeries for recurrent prolapse. On patient 21, a second laparoscopic sacropexy was performed, since a previous complete mesh removal had been necessary. This patient had a previous polyester mesh, and a polypropylene mesh was placed 10 months after the removal of the first one. Patient 33, on the other hand, had needed multiple pelvic adhesiolysis during laparoscopic sacropexy and presented an acute peritonitis on day 3, which would contribute to a more difficult insertion of a new mesh. A transvaginal approach was preferred for recurrent vaginal vault prolapse treatment in this case.

Limitations of this study are primarily related to its retrospective nature and small sample size. The fact that not all clinical data were accessible also limited our analysis. Even the technique evolved along the years. Follow-up intervals were not equivalent between all subjects, so it is possible that with time, new complications will be revealed. The retrospective nature of this study made it difficult to assess subjective symptoms of complications, so the clinical presentation is mostly based on signs.

In 2007, our center published a series on complete laparoscopic treatment of genital prolapse30, with no major complications, 5% of vaginal mesh erosion and 1% of mesh removal due to infectious complications. The authors intention was never to present a further statistical analysis of mesh-related complications, but rather a comprehensive review of their experience, by considering all cases of patients who needed subsequent surgery for treating complications after sacropexy.

In conclusion, when performing laparoscopic sacropexy, surgeons should be aware of the risk factors for complications such as vaginal opening, post-hysterectomy status (complicating dissection and contributing to tissue devascularization), uterine perforation, adhesiolysis, through-and-through vaginal stitches and hypoestrogenism. Those situations should alert to the fact that need of re-intervention is more likely. In order to prevent this complication, some measures may be taken:

• Avoidance of aggressive coagulation of the vaginal wall during dissection on vault prolapse correction.

• Avoiding vaginal opening.

• Vaginal preparation with topic oestrogens.

• Systematic check for transfixing vaginal suture and avoiding overtraction.

• Utilization of light monofilament polypropylene meshes.

In case of possible mesh contamination (e.g.: bowel perforation), the procedure should be interrupted or no mesh shall be left in place.

Patients should be motivated to stop smoking and to respect pre-operative vaginal preparation with topic oestrogens. Patients with mesh exposure with associated risk factors (smoking, prior surgical scarring, oestrogen deficiency, concomitant hysterectomy) should be advised about the higher risk of mesh exposure.

Mostly, the surgeon should be able to predict which complications are more likely to happen to each particular patient. Moreover, longterm complications should be never neglected. The longer the follow-up, the later the diagnosis of complications can happen. It seems reasonable to assume that a patient with a mesh implanted is always at risk for mesh exposure.

After a mesh placement, patients are at risk for requiring multiple surgeries to resolve complications, surgeries that can be ineffective and expose the patient to new complications. Major complications can occur, as great vessels or urinary tract injury, and dissection can be challenging - during prolapse surgery or during complication-resolving surgery. Laparoscopic treatment of complications is feasible, but not always easy. The ability to resolve surgery and mesh-related complications should be considered a pre-requisite to perform prolapse surgery.

REFERENCES

1. Maher C, Feiner B, Baessler K, Schmid C. Surgical management of pelvic organ prolapse in women. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013 Apr 30;4:CD004014. [ Links ]

2. Parkes IL, Shveiky D. Sacrocolpopexy for the Treatment of Vaginal Apical Prolapse: Evidence Based Surgery. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2014 July - August;21(4):546-557.

3. Nygaard IE, McCreery R, Brubaker L, Connolly A, Cundiff G, Weber AM, Zyczynski H; Pelvic Floor Disorders Network. Abdominal sacrocolpopexy: a comprehensive review. Obstet Gynecol. 2004; 104(4):805-823. [ Links ]

4. Botchorishvili R. Prolapsus et incontinence urinaire par promonto-fixation et réparation paravaginale. In: Chirurgie coelioscopique en gynécologie (2nd Edition). Mage G (ed). Elsevier Masson SAS; 2013:171-184.

5. Mustafa S, Amit A, Filmar S, Deutsch M, Netzer I, Itskovitz-Eldor J, Lowenstein L. Implementation of laparoscopic sacrocolpopexy: establishment of a learning curve and short-term outcomes. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2012 Oct;286(4):983-988.

6. Diwakar GB, Barber MD, Feiner B, Maher C, Jelovsek JE. Complication and reoperation rates after apical vaginal prolapse surgery repair: a systematic review. Obstet Gynecol. 2009; 113(2 Pt 1): 367-373. [ Links ]

7. Cundiff GW, Varner E, Visco AG, Zyczynski HM, Nager CW, Norton PA, Schaffer J, Brown MB, Brubaker L; Pelvic Floor Disorders Network. Risk factors for mesh/suture erosion following sacral colpopexy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2008;199(6):688. [ Links ]

8. Kohli N, Walsh PM, Roat TW, Karram MM. Mesh erosion after abdominal sacrocolpopexy. Obstet Gynecol. 1998;92(6): 999-1004. [ Links ]

9. Feiner B, Jelovsek JE, Maher C. Efficacy and safety of transvaginal mesh kits in the treatment of prolapse of the vaginal apex: a systematic review. BJOG. 2009;116(1):15-24. [ Links ]

10. Shah H, Badlani G. Mesh complications in female pelvic floor reconstructive surgery and their management: A systematic review. Indian J Urol. 2012 Apr-Jun; 28(2):129-153.

11. Rahn DD, Good MM, Roshanravan SM, Shi H, Schaffer JI, Singh RJ, Word RA. Effects of preoperative local estrogen in postmenopausal women with prolapse: a randomized trial. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2014 Oct;99(10):3728-3736.

12. Begley JS, Kupferman SP, Kuznetsov DD, Kobashi KC, Govier FE, McGonigle KF, Muntz HG. Incidence and management of abdominal sacrocolpopexy mesh erosions. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2005; 192(6):1956-1962. [ Links ]

13. Visco AG, Weidner AC, Barber MD, Myers ER, Cundiff GW, Bump RC, Addison WA. Vaginal mesh erosion after abdominal sacral colpopexy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2001;184(3):297-302. [ Links ]

14. Clavien PA, Barkun J, de Oliveira ML, Vauthey JN, Dindo D, Schulick RD, de Santibañes E, Pekolj J, Slankamenac K, Bassi C, Graf R, Vonlanthen R, Padbury R, Cameron JL, Makuuchi M. The Clavien-Dindo classification of surgical complications: five-year experience. Ann Surg. 2009 Aug; 250(2):187-196.

15. Handa VL, Garrett E, Hendrix S, Gold E, Robbins J. Progression and remission of pelvic organ prolapse: a longitudinal study of menopausal women. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2004;190(1): 27-32. [ Links ]

16. Hendrix SL, Clark A, Nygaard I, Aragaki A, Barnabei V, McTiernan A. Pelvic organ prolapse in the Women’s Health Initiative: gravity and gravidity. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2002 Jun;186(6):1160-1166. [ Links ]

17. Wu JM, Matthews CA, Conover MM, Pate V, Jonsson Funk M. Lifetime risk of stress urinary incontinence or pelvic organ prolapse surgery. Obstet Gynecol. 2014 Jun;123(6):1201-1206.

18. Thibault F, Costa P, Thanigasalam R, Seni G, Brouzyine M, Cayzergues L, De Tayrac R, Droupy S, Wagner L. Impact of laparoscopic sacrocolpopexy on symptoms, health-related quality of life and sexuality: a medium-term analysis. BJU Int. 2013 Dec;112 (8):1143-1149.

19. Warner WB, Vora S, Alonge A, Welgoss JA, Hurtado EA, von Pechmann WS. Intraoperative and postoperative gastrointestinal complications associated with laparoscopic sacrocolpopexy. Female Pelvic Med Reconstr Surg. 2012; 18(6):321-324. [ Links ]

20. de Tayrac R, Letouzey V. Basic science and clinical aspects of mesh infection in pelvic floor reconstructive surgery. Int Urogynecol J. 2011 Jul;22(7):775-780.

21. Warner WB, Vora S, Hurtado EA, Welgoss JA, Horbach NS, von Pechmann WS. Effect of operative technique on mesh exposure in laparoscopic sacrocolpopexy. Female Pelvic Med Reconstr Surg. 2012; 18(2):113-117. [ Links ]

22. de Tayrac R, Sentilhes L. Complications of pelvic organ prolapse surgery and methods of prevention. Int Urogynecol J. 2013; 24:1859-1872. [ Links ]

23. Shepherd JP, Higdon HL 3rd, Stanford EJ, Mattox TF. Effect of suture on the rate of suture or mesh erosion and surgery failure in abdominal sacrocolpopexy. Female Pelvic Med Reconstr Surg. 2010 Jul;16(4):229-233. [ Links ]

24. Boulanger L, Boukerrou M, Rubod C, Collinet P, Fruchard A, Courcol RJ et al. Bacteriological analysis of meshes removed for complications after surgical management of urinary incontinence or pelvic organ prolapse. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 2008 Jun;19(6):827-831.

25. Vollebregt A, Troelstra A, van der Vaart CH. Bacterial colonisation of collagen-coated polypropylene vaginal mesh: are additional intraoperative sterility procedures useful? Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 2009 Nov;20(11):1345-1351.

26. Billone V, Amorim-Costa C, Campos S, Rabischong B, Bourdel N, Canis M et al. Laparoscopy-like operative vaginoscopy: a new approach to manage mesh erosions. J Minim Invasive Gynecol 2015 Jan;22(1):10.

27. Birch C, Fynes NM. The role of synthetic and biological prosthesis in reconstructive pelvic floor surgery. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol. 2002: 14:527-595. [ Links ]

28. Chamsy D, Lee T. Laparoscopic Excision of Sacrocolpopexy Mesh. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2014 Nov-Dec;21(6):986.

29. Nygaard I, Brubaker L, Zyczynski HM, Cundiff G, Richter H, Gantz M et al. Long-term outcomes following abdominal sacrocolpopexy for pelvic organ prolapse. JAMA. 2013 May 15; 309(19):2016-24. [ Links ]

30. Rivoire C, Botchorishvili R, Canis M, Jardon K, Rabischong B, Wattiez A, Mage G. Complete laparoscopic treatment of genital prolapse with meshes including vaginal promontofixation and anterior repair: a series of 138 patients. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2007 Nov-Dec;14(6):712-718.

Endereço para correspondência | Dirección para correspondencia | Correspondence

Sara Campos

E-mail: saraginecobs@gmail.com

Authors’ contribution

S Campos: project development, data collection, data analysis, manuscript writing

V Billone: data collection, data analysis

M Durão: manuscript writing

M Beguinot: data collection, data analysis

N Bourdel: responsible surgeon

B Rabischong: responsible surgeon

M Canis: responsible surgeon, manuscript writing

R Botchorishvili: project development, data collection, data analysis, responsible surgeon, manuscript writing

All patients gave their informed consent prior to their inclusion in the study.

The authors have full control of all primary data and they agree to allow the journal to review their data if requested.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest and received no funding.

Recebido em: 11-12-2014

Aceite para publicação: 01-05-2015