Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Acessos

Acessos

Links relacionados

-

Similares em

SciELO

Similares em

SciELO

Compartilhar

e-Journal of Portuguese History

versão On-line ISSN 1645-6432

e-JPH vol.17 no.2 Porto dez. 2019

https://doi.org/10.26300/51ha-kh55

ARTICLES

The Patron Saints and Devotions of the Benedictine Military Orders (Portugal and Castile, 15-16th Centuries)

Paula Pinto Costa1, Raquel Torres Jiménez2, Joana Lencart3

1Faculdade de Letras da Universidade do Porto, Portugal. E-Mail: ppinto@letras.up.pt

2 Facultad de Letras de la Universidad de Castilla La Mancha, Espanha. E-Mail:: raquel.torres@uclm.es

3 Lab2PT, Universidade do Minho, Portugal. E-Mail: joana.lencart@meo.pt

ABSTRACT

This paper studies hagiographic devotion in the seigniories of the military orders: the Orders of Avis and Christ in Portugal and of Calatrava in Castile. Applying a common methodology and using similar sources for all three cases, this paper analyzes the written testimonies of the orders’ devotion to Christ and the Virgin Mary, as well as their veneration of the saints. These records were compiled from the visitations made to churches, hermitages, and confraternities between 1462 and 1539. The research was governed by two objectives: firstly, to construct a hagiographic overview of the selected territories by systematizing the data collected; and, secondly, to reflect on the typical devotional profile of the territories of the military orders as portrayed by the documentary evidence.

Keywords: Military orders; Calatrava; Avis; Christ; Hagiography; Medieval religiosity.

RESUMO

Este trabalho estuda a devoção hagiográfica nos senhorios das Ordens Militares de Avis e Cristo em Portugal, e de Calatrava em Castela. Usando metodologia e fontes comuns, são analisados testemunhos escritos da devoção a Cristo e à Virgem, bem como aos santos. Os visitadores compilaram estes registos durante as visitações às igrejas, ermidas e confrarias nos territórios dessas Ordens entre 1462 e 1539. Dois objetivos estão subjacentes a esta investigação: primeiro, construir uma visão hagiográfica geral dos territórios em estudo, sistematizando os dados coligidos e, segundo, refletir sobre as características específicas e o perfil devocional dos domínios das Ordens Militares.

Palavras-Chave: Ordens militares; Calatrava; Avis: Cristo; Hagiografia; Religiosidade Medieval.

Introduction

Few studies have been made of the hagiography of medieval military orders. The religious aspects of these institutions have not been investigated as frequently as their military, institutional, material, economic, and political dimensions.[4] There have been some studies of the spirituality and devotions of the international military orders, but none of these are specifically about the Iberian orders; this justified the approach adopted here. The few studies that do, in fact, focus on the hagiography of the military orders do not deal with Portugal and Castile, the territories examined in this paper. In Portugal, three specific publications should be noted (Costa and Lencart 2017: 57-69). In Castile, the religious dimension of the military orders has been studied (Ayala Martínez 2014: 331-346; Ayala Martínez 2015: 547-562; Torres Jiménez 2010: 261-302; Torres Jiménez 2000: 1087-1116; Torres Jiménez 1996: 433-458; Josserand 2004), but the cults of different saints have received little attention (Torres Jiménez 2005a: 37-74; Torres Jiménez 2005b: 155-180). There is, however, a vast literature on the international military orders, namely on the Order of the Temple. There are two main reasons for this. Firstly, because the treatise written by St. Bernard of Clairvaux-De laude novae militia- presented a matrix for the new spiritual model for religious knights; and secondly, because of the process of the order’s suppression at the beginning of the fourteenth century (Nicholson 2005: 91-113; Carraz and Dehoux 2016).

From their very beginning, the military orders were complex religious and military institutions operating in accordance with the ideals of the Crusades. The main feature that distinguished their religiosity was the model of the Miles Christi, both in the Latin East and in Iberia. The knights played an important defensive and organizational role in protecting the large manorial estates, particularly in the frontier areas between the Portuguese and the Castilian kingdoms. As a consequence, they were able to guarantee the continuity of the ecclesiastical and spiritual features of their orders on these estates.

During the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, the Benedictine military orders were the Order of Calatrava, in Castile, and the Orders of Avis (affiliated with Calatrava) and Christ, in Portugal. All three orders were inspired by the Benedictine rule, although they issued their own normative corpora. The ties to St. Benedict derived from St. Bernard’s De Laude Novae Militia.

These military orders performed a significant role in the period under analysis, not only in relation to religious aspects, but also in relation to Peninsular society in general. Their seigniories were organized into several dozen territories, administered either by the commander or the master of the order, or even by the convent itself. During the campaign for the reconquest of the Iberian Peninsula, the knights were especially favored by the monarchs, as well as by some prestigious families. They accumulated great swathes of land as well as all manner of jurisdictional and ecclesiastical privileges granted by the Popes. Thus, the brethren of the orders were responsible for their religious organization in general and for their liturgical activities in particular.

The comparative nature of this study enhances the quality of the analysis that is presented here because these orders were all established in Iberia, independently of any diplomatic and political borders. From a methodological perspective, experts in the study of medieval military orders have achieved some notable results (Josserand; Oliveira and Carraz 2015; Torres Jiménez and Ruiz Gómez 2016). Nonetheless, it is not our purpose to bring together various studies on a specific topic relating to the different orders. Instead, this study seeks to present a comparison based on a common methodology and objectives. A third important dimension of this study is the intersection between the religious aspects of the orders and the social history of the period in question. In fact, the worship of saints was one of the most typical features of medieval popular religion, as was noted by the pioneering sociological studies of religious orders, first developed almost fifty years ago (Boglioni 1972: 55-56) and influenced by several scientific areas. The hagiography of these orders is vast and was given a fresh impetus in the 1980s. The number of studies focusing on local and regional contexts has consistently increased since then (Acta Sanctorum 1999-2002; Brown 1984; Cantera Montenegro 1985: 39-61; Christian 1990; Vauchez 1994; Abou-el-Haj 1997; Deuffic 2006; Guiance 2014; Pérez-Embid Wamba 2017).

However, such knowledge has not developed to the same extent in the specific case of the military orders. Moreover, hagiographic devotion is seen as an obvious factor affecting the organization of the territories administered by the military orders. Therefore, gathering knowledge about these orders takes us far beyond the strictly religious level and helps to increase our understanding of their seigniories and the way in which these were run. Gathering information from manuscripts about the patron saints of the Benedictine military orders in the late medieval period also broadens our knowledge about religious devotion in Latin Europe.

The hagiographic testimonies of the visitations undertaken by the three orders to the churches, hermitages, and confraternities in their territories between 1462 and 1539 helped to achieve two main objectives: firstly, to construct a hagiographic overview of the selected territories; secondly, to reflect upon the meaning of these sources, given that they revealed some information about devotional practices in the domains of the military orders.

The evidence gathered includes information about Christological, Marian, and the orders’ own forms of hagiographic worship and venerations. Their patron saints were depicted on the high altars of their churches, hermitages, and confraternities. The orders’ confraternities were associated either with a church, or, in a few cases with hospitals, because they had no explicit links with any one particular saint. These charitable institutions were referred to simply as hospitals, although sometimes they bore the name of the confraternity that was responsible for their administration. In Campo de Calatrava (Castile), parish churches were referred to as the “main churches.” In some cases, it was difficult to categorize and label the devotional spaces. This was the case, for example, with the commandery of Marmeleiro (Order of Christ), where the same sacred building, devoted to St. Catherine, is classified both as a chapel (an altar inside a church) and as a hermitage.[5]

The patron saints indicated the devotional piety of the knights, as well as of the people who lived in their domains. Some of these saints may have been assigned to the churches even before the orders began to administer them. This means that the order simply adopted the church’s previous invocation. Nevertheless, some patron saints might have been altered by the orders. There is at least one such case in the Order of St. John (Rosas and Costa 2014: 177-192). In fact, in order to fully identify the devotional profile of a military order, besides the precepts laid out in the normative texts, it is imperative to consider the patron saints of the churches associated with their convent buildings.

The testimonies from the visitations and from other records administered by the institutions themselves (tombos, e.g. descriptions of properties) are the main sources for this study. In Portugal, the chronology of the documents spans the period from 1462 to 1538. However, this type of record was not always available. For example, in the case of Idanha-a-Nova, in 1505, all the churches in the village were said to belong to the Order of Christ, “as stated in the process of the visitations,” but, in fact, that process does not exist in the Portuguese archives.[6] In this case, the lack of information results from the absence of the visitation records of some commanderies between 1505 and 1510. This missing information can be partly offset with the data collected from the “tombos,” as these have roughly the same chronology. These time frames are coincidentally valid for Campo de Calatrava, in Castile, where the visitations are dated as taking place from 1471 to 1539. In this latter case, there is also a book written in 1570: “Relaciones Topográficas de Felipe II” [Topographic relations of the Spanish towns, made under the command of Philip II], which provides information on the order’s forms of worship and its vows dating back to the first decades of the sixteenth century.[7]

The criteria for recording information may not have been strictly the same across the different sources that have been identified, even though all the texts relate to orders with a close affinity and even with strong legal and functional connections. In fact, different legal documents and government practices could result in different written records. Beyond these substantive issues, the modus operandi of the people involved in each of these processes was a decisive factor in determining the nature of what was written down. Visitors mainly addressed issues relating to the orders’ heritage and the behavior of their knights and congregation, while the description of the orders’ religious practices and spirituality was not their main objective. Furthermore, they did not attempt to be exhaustive in their accounts. Also worth highlighting are the differences between the level of the institution’s religiosity, observed mainly by its clergy, and the popular worship noticed at hermitages, confraternities, and brotherhoods.

From a territorial point of view, there are substantial differences between the Portuguese and the Castilian cases. In Castile, all the territory was centralized in Campo de Calatrava, the order’s seigniory located between Montes de Toledo and Sierra Morena, or between Toledo and Andalusia, in the central-southern area of Castile. In Portugal, however, such property was more spread out: the commanderies were located along a north-south axis, especially in the Alto Alentejo in the case of the Order of Avis, and in Trás-os-Montes and the Beira frontier area in the case of the Order of Christ. Considering these circumstances, it is difficult to establish a reliable criterion for identifying the locations where the chapels and hermitages studied were found.

Data, results and interpretations

From the sources consulted, it can be seen that the Order of Avis recorded three visitations that took place in 1515,[8] 1519,[9] and 1538,[10] as well as one more in 1512, relating only to Telhada.[11] As this last record makes no reference to any patron saint, it was disregarded. Sources from the Order of Christ detailed four clusters of visitation activity: 1462,[12] 1505,[13] 1507,[14] and 1536.[15] The accounts of the Order of Calatrava presented ten visitation campaigns: 1471, 1491, 1493,[16] 1495, 1500,[17] 1502,[18] 1508-1510,[19] 1535,[20] 1537-1538, and 1539.[21]

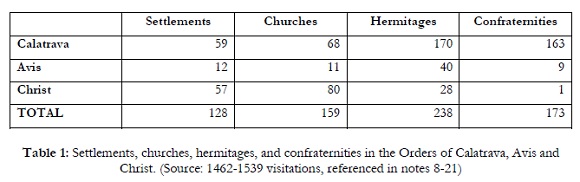

On the basis of these documents, it is possible to identify the places of devotion associated with different locations, as described below. Counting the locations was sometimes difficult, because there were frequently several churches included in the same territory, as was the case, for example, in Tomar, where there were 13 religious buildings.[22]

The inverse relationship between the number of churches and hermitages in the three orders is curious. Thus, while the Orders of Calatrava and Avis display a similar proportionality in terms of hermitages, the Order of Christ shows a higher number of churches. These numbers should be understood as valid for a specific chronology, given that the classification of devotional spaces could occasionally suffer alterations, as has already been mentioned in the case of Campo de Calatrava (Torres Jiménez 2013: 207). Another example comes from the territory of Dornes, belonging to the Order of Christ, this time relating to the parish church of St. Alexis, which was referred to as a hermitage before 1510.[23] In eight settlements belonging to Campo de Calatrava, the parish church was replaced by a larger one, located in the center of the village. This new church took a different invocation, while the old parish church became a hermitage.[24] Differences in the size of the territory and the concentration of the population in the place where the religious heritage was to be found, as well as variations in the population density, can clearly interfere with the numbers that are presented here.

Scattered hermitages from former times played an important role in the settlement of peripheral territories (Torres Jiménez 2013: 195 and 197 ff.). The Order of Christ had a lower number of hermitages, which may simply be the result of a reduced interest in recording them. The higher degree of political exposure enjoyed by the Order of Christ may have had an impact on these results. From its foundation (1319) onwards, this Order was considered to be a royal institution. In the late Middle Ages, the fact that King Manuel I himself was the Master of this Order probably accounted for the downgrading of the value and importance of those places of worship representing popular spirituality (hermitages). The order’s leading officials were more concerned with investing heavily in churches, which were regarded as central elements in the institution’s network of commanderies. Moreover, churches represented a prestigious heritage, in contrast to hermitages, which were small, poor buildings in isolated places. The greater exposure of the Order of Christ to the monarchy and its wealth may have increased the attention paid by the episcopal authorities towards the control of their main places of worship, in other words, their churches (Vilar 2018: 93-108). Furthermore, the sources that were consulted reported on the poor state of conservation of some hermitages and the works that were done there, in answer to the questions asked by the knight commander himself when visiting the area.[25]

Popular spirituality is also reflected in the names of the saints, which invoked mother nature and other environmental features, such as the hermitage of Nossa Senhora das Ervas (Our Lady of the Herbs) in Avis. The proliferation of hermitages in the Order of Avis could also have been a central element in the ecclesiological organization of the space (García de Cortázar 2012: 288-300.). According to Raquel Torres Jiménez the role of religiosity in establishing the identity of hermitages strengthened the sense of belonging to a community and a territory. Hermitages expressed a sense of sociability and were considered special, sacralized centers within a territory. Furthermore, they held religious and recreational festivities for the benefit of the community, also developing a clearly civic dimension (Torres Jiménez 2013: 187-214).

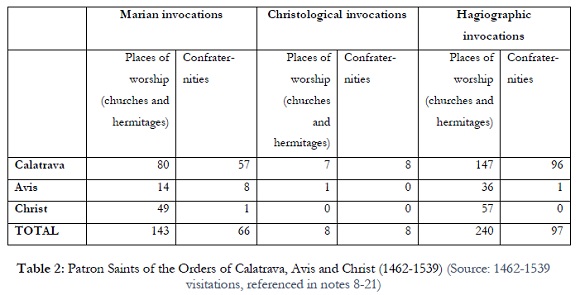

The patron saints are classified below as being Marian, Christological, or hagiographic. There are large differences across each of the categories shown.

Marian devotion always enjoyed a privileged role. The twelfth and thirteenth centuries were the golden age of people’s devotion to the Virgin Mary (Bergonzini 2015: 39-45; Torres Jiménez 2016-17: 23-59). This cult was disseminated by Franciscan, Dominican, and Cistercian monks and was clearly displayed in the following centuries when the Virgin Mary became the object of both clerical piety and popular devotion. The worship of the Virgin Mary undoubtedly represented the most widespread devotion within the territories of the military orders analyzed here. The most common invocation and name attributed to parish churches, hermitages, and confraternities was that of St. Mary or Our Lady, although there were also many specific Marian patronages. The most common invocation in Campo de Calatrava was that of Our Lady of the Assumption (Jounel 1992: 1024-1039; Ladero Quesada 2004: 59-60). In the case of the hermitages, the names were highly diversified, reflecting popular taste. Invocations would highlight the association of the Virgin with nature: St. Mary of the Valley, of Valdeleón, of the Hawthorns, of the Mount, of Nava, of the Star, and of Snow in Calatrava, and Our Lady of the Herbs in Avis, as already mentioned. The Virgin Mary was also commemorated because of her protective powers: Virtues, Grace, Mercy, the Head of Saints, the Way, of the Baths and of Fuencaliente. There were also other invocations relating to toponymy: Our Lady of Aberturas and of Barajas in Calatrava, along with St. Mary of Vila Real in Avis. Theological and liturgical names are also worth noting-Nativity, Visitation, Immaculate Conception, Purification and the High Heavens-as well as depictions of the Virgin in relation to the Passion of her son Jesus (Our Lady of the Crosses in Calatrava, Our Lady of Tears, and the image of the Pietà, the Virgin cradling her dead Son, on an altar in the Order of Christ).

Marian devotion also included the veneration of the Archangel St. Gabriel (Calatrava) and of the Virgin’s family: St. Joseph with the Virgin on a high altar in Avis and St. Anne (in a hermitage in Avis; and in a church, three hermitages, and two confraternities in Calatrava). The worship of Mary’s mother, St. Anne, was very popular in Castile (Christian 1991: 53-54 and 315, n. 43) and even more so in Campo de Calatrava, due to her apparition in Puertollano, a tradition accepted by the visitors of Calatrava.[26]

In Portugal, the lack of Christological invocations was counterbalanced by other devotions that were closely related to the human figure of Christ, and which are included here under the hagiographic category, such as St. Peter, St. Mary Magdalene, St. John the Baptist, and the Holy Savior. This latter invocation was very common in the early Middle Ages. The worship of the Holy Savior started in the western world in the eighth century and the invocation was highly popular as an alternative name for Jesus Christ. It was not displaced until the thirteenth century when the devotion to the Holy Cross began to emerge. However, there were no invocations to the Holy Cross to be found at the churches of the orders studied here and only two hermitages were dedicated to St. Mary of the Crosses in Calatrava. In turn, the worship of St. Mary Magdalene appeared as a paradigm of perfection and radical conversion (Vorágine 2016 (ed.): I, 382-92; Scattigno 2000: 1619).[27] In these three military orders, such devotion reflects the medieval dissemination of models of holiness that were different from those that prevailed during the High Middle Ages and which were mainly focused on martyrs, bishops, and monks (Pérez-Embid Wamba 2017: 51-56 and 61-93).

The cyclical celebrations throughout the year of the different liturgical dimensions of Christ (birth, life, and death) may explain why his name only infrequently appeared among the patron saints. In the written documents of the Order of Calatrava, there are expressions such as Christ, God the Father, the Holy Trinity, the Holy Spirit, and Eucharist (three hermitages and three parish churches of the Holy Savior, one Trinity church, one Corpus Christi hermitage, and seven Eucharistic confraternities) (Torres Jiménez 2001: I, 293-328). The Passion of Jesus Christ is observed through iconography: there are plenty of Ecce Homo images in Campo de Calatrava, as well as images of the Veronica and the Five Wounds. All three military orders venerated the Crucifixion and Calvary (Jesus on the cross with the Virgin and St. John) as well as the Fifth Sorrow. Furthermore, there is clear documentary evidence of a devotion to the Cross among the members of the Order of Calatrava.[28] However, a methodological note must be made here. Although the worship of God is sufficiently documented, this does not reflect its full dimension at that time. Reverence for Christ appears to have been a secondary affair when compared to the devotion to the saints and to the Virgin Mary, to whom many confraternities, hermitages, and churches were dedicated. Their respective feasts were celebrated precisely because the mysteries of the Incarnation and the Passion are themselves central to the liturgy.

Saints were considered to be exceptional persons, mirrors of God, who were recognized by the Church. From Innocent III (1198-1216) onwards, the Pope was the only person entitled to authorize the cult of the different saints, and, in 1234, Gregory IX institutionalized the process of canonization (Pérez-Embid Wamba 2017: 139; Vauchez 2004: 357-363). Saints were seen as intercessors in the salvation of the soul and as protectors more than as models of Christian life (Pablo Maroto 1998: 392), although this latter role had grown in importance since the twelfth and thirteenth centuries (Vauchez 1994: 449-478). This theological perspective was reflected in some of the religious behaviors adopted by society.

Besides the patron saints, when it came to the dedications of the high altars, the range of devotional invocations increased notably. The same can be said for all the images housed in these sacred places. The most frequent devotional groups (taking into account the patron saints of the orders’ churches, hermitages, and confraternities), in other words those with four or more occurrences, comprised different saints in each of the three orders: St. Mary (thirteen), St. Sebastian (six), St. Peter (four), and St. James the Greater (four) in the Order of Avis; and St. Mary (forty three), St. Peter (seven), St. Mary Magdalene (five), St. Martin (five), St. Michael (four), and St. Sebastian (four) in the Order of Christ. In the Order of Calatrava’s seigniory of Campo de Calatrava, the dedications to the Virgin Mary were worth noting: St. Mary, Our Lady and all of her specific variations (one hundred thirty seven), followed by St. Sebastian (forty four), St. John the Baptist (twenty three), St. Bartholomew (nineteen), St. Antony the Great (fourteen), St. James the Greater (fourteen), St. Mark (twelve), St. Andrew (ten), St. Benedict (nine), St. Quiteria (eight), St. Mary Magdalene (eight), St. Peter (six), St. Anne (six), and St. Christopher (five).

St. Mary and her different invocations were also recorded in recognition of her virtues or in reference to some elements of nature, or even to local toponymy as a symbol of the similarity between the Mother of God and the Mother of the Church. Moreover, St. Peter was also notably present in the Orders of Avis and Christ due to his symbolic dimension as the co-founder of the Church. In the Orders of both Avis and Calatrava, the devotion to St. Sebastian was the second most important invocation after that of the Virgin Mary. The proliferation of the patronage of this third-century military martyr matched his great fame in the western world as a great protector against the plague, a reputation which started in the ninth century (Scorza Barcellona 2000: II, 2031) and was disseminated through the Golden Legend of Jacobus de Voragine (Vorágine 2016 (ed.): I, 116).

The Virgin Mary was strongly venerated within the military orders and worshippers were encouraged to go to the feasts held in honor of the Virgin as well as of St. Bernard as a means of indulgence.[29] While it is quite simple to understand this recommendation, on the contrary, it is not easy to interpret the similar advice given in relation to St. Bernard. Indeed, the Benedictine military orders seem to have been closer to St. Benedict and his experiences than to St. Bernard, who was, above all, the mentor of the Knights Templar, to whom late medieval Europe attributed responsibility for a long list of sins.

Bearing in mind the Benedictine origins of the three orders, the absence of St. Bernard and the scant devotion afforded to St. Benedict merit special attention. St. Benedict is found only in three hermitages in Avis, in two churches of the Order of Christ and in three churches, five hermitages, and one confraternity of the Order of Calatrava. In turn, only two hermitages dedicated to St. Bernard were identified in Calatrava. One credible explanation for this situation would be that these orders probably retained the patron saints that had already been adopted before they settled in those places. It is also possible that the reduced representation of those Benedictine saints is due to the relative weakness of the military orders’ participation in the spiritual traditions of the Cistercian monastic order, the renovated branch of the Benedictines. It is significant that visitors ordered that paintings of both of those saints should be placed in the churches of Campo de Calatrava, often on the high altar. But this requirement did not meet with a solution. They also ordered that images of other saints should be replaced by those of St. Benedict and St. Bernard, but, again, they were not obeyed. Some documents suggest that the vassals of the Order of Calatrava were unfamiliar with the images of these saints.[30] In contrast, the church of Santa Maria do Cano in Avis was ordered to organize a solemn procession in honor of St. Benedict, which was to be afforded the same level of dignity as the one dedicated to Corpus Christi.[31] Records also reveal a series of references to St. Benedict, who was even mentioned as “Our Father.” Furthermore, the celebration of his feast was instituted at St. Benedict hermitages in Alandroal and Seda.[32] The absence of St. Bernard can be explained by the fact that he was the mentor of the Knights Templar, an order that gave rise to great controversy and was suppressed at the beginning of the fourteenth century. In the late Middle Ages, the members of the order showed a tendency to dismiss him from their invocations. The same situation occurred with St. Raymund of Fitero, one of the founders of the Order of Calatrava in 1158. In fact, there were no invocations made in his name from the mid-thirteenth century onwards, in spite of his healing and protective virtues (he was invoked as a protector against lightning and hail) (Mateo 2000: II, 1957-1959; Gutton 1955: 29).

According to the instructions given by the visitors, one of their major concerns was to supply the main altar with symbols that were expected to dignify worship inside the religious spaces. The consequent status of patron saints was created through these measures. In keeping with these objectives, in the Order of Christ, an altarpiece dedicated to St. James the Greater was ordered to be placed on the main altar of the church of St. James the Greater in Soure.[33] At the church of Our Lady of Grace in Ega, an altarpiece dedicated to Our Lady of Grace was ordered to be erected on the high altar within a year.[34] At the church of Our Lady of Tears in Dornes, high-quality paintings of her image were commissioned.[35] At the church of St. Mary in Alcains, an image of the Virgin Mary, made of either stone or wood, was ordered to be placed on the altar. This image was to be “fermosa e bem pintada” [beautiful and well-painted] and was to measure at least four spans in height. It was commissioned in order to replace the previous one, which was small, old, and badly painted.[36] At the church of Our Lady in Proença, an altarpiece was commissioned, depicting the Virgin Mary with her son on her lap.[37] In turn, the order issued by the visitors of the Order of Avis to the church of St. Mary of Cano was more far-reaching and commissioned the following works: an altarpiece of Our Lady and St. Benedict, an image of St. Michael, one of the Crucifix, one of Our Lady, and one of St. John.[38] The main reason for this order seems to have been the weak preservation of that hermitage, that had imposed the requirements of the visitors. The visitors insisted on the changes at the church of St. Blaise in Figueira, where the image of Our Lady on the high altar was ordered to be repainted within a year, even though the patron saint was St. Blaise.[39] Visitors to the Igreja de São João da Praça, in Redinha, ordered an altarpiece with the image of Our Lady of Grace to be placed in the church within a year.[40]

Sources also reveal that, in Campo de Calatrava, each church had the image of the Virgin Mary or the saint to whom it was dedicated. In this area, it was customary to dress the images, especially those of the Virgin Mary and the Virgin and Child. They were ornamented with jewels and with a variety of clothes made from fine, rich fabrics donated by the people, especially by women (Torres Jiménez 2018: 145-160). As the visitors were opposed to this clear manifestation of popular religiosity, they made some efforts to change it, although their orders seem not to have been obeyed.[41]

Sometimes the senior officials of the military orders would attempt to encourage certain devotions, not only to St. Benedict and St. Bernard, but also to St. John the Baptist, whose image they ordered to be painted close to baptismal fonts. Sometimes, the members of the congregation themselves would encourage special devotions, which were then incorporated as patron saints. One resident in Villarubia, for instance, had the figure of St. Quiteria painted next to St. Antony the Great on the altar of the church of St. Mary Major.[42] This third-century martyr (Román López 1999: 186) was widely venerated in rural Castile, due to her status as a protectress against rabies (Christian 1991: 95). Other individuals founded a chapel in honor of St. Antony the Great in the church of St. Bartholomew of Almagro. St. Antony the Great was the prototype of the eremitic life, a defender of animals and a protector against fire.[43] Rodrigo de Oviedo, the Commander of the Order of Calatrava, also founded a chapel dedicated to St. Sylvester.[44]

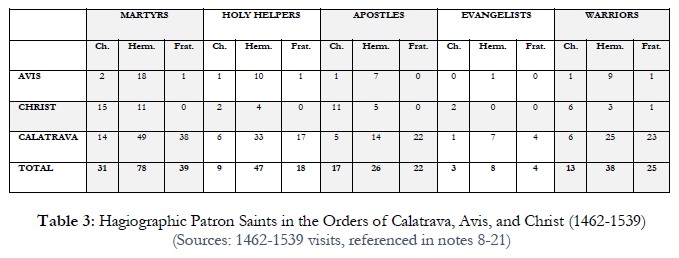

As mentioned above, the worship of different kinds of saints was one of the most important devotional practices. According to the data collected, it is possible to define five categories of these practices, although they are not totally distinct from one another. This means, for example, that some warrior saints may also have been martyrs; St. James could similarly be classified among either the apostles or the warrior saints. In accordance with this methodological exercise, the following table shows the most common label for each saint.

(clique para ampliar ! click to enlarge)

Two main patterns may be deduced from the above table: the predominance of the categories of Martyrs and Holy Helpers; and the similarity between the Orders of Avis and Calatrava as far as the number of hermitages dedicated to honoring the martyrs is concerned.

In terms of hagiographic devotion, Martyrs and Holy Helpers (only some of them) were prominent in the Order of Avis. The martyrs were celebrated in twenty-one sacred places. In turn, the term “holy helpers” constitutes a non-liturgical title relating to the specific graces that they offered. The fourteen Holy Helpers, all of whom were essentially martyrs, were systematized as a group in the fourteenth century in Germany, and were then widely disseminated during the early modern period across the northern European world, including Germany (Chiesa 2000: I, 378). The Holy Helpers included St. Catherine, St. Blaise, and St. Sebastian, who were especially relevant for the military orders. Curiously, of the twelve religious spaces dedicated to the Holy Helpers, ten were hermitages, one was a confraternity, and only one was a church. These data seem to underline the value that those saints had as agents of divine intercession. The devotion to the Holy Helpers had a more popular profile and thus tended to be practiced more at the hermitages, which were mainly located in rural environments.

In contrast, the Order of Christ focused most strongly on the veneration of Martyrs and Apostles (fifteen churches and eleven hermitages were dedicated especially to St. Sebastian and St. John the Baptist). The apostles were celebrated in sixteen places: eleven churches (five dedicated to St. Peter, two to St. James the Greater, two to St. Bartholomew, one to St. John, and one to St. Matthew) and five hermitages (two dedicated to St. Peter, one to St. Andrew, one to St. Bartholomew, and one to St. Thomas). Perhaps the notable presence in this list of St. John the Baptist and the apostles may reflect the dedication of this order to Christ, which was obviously quite significant in an order whose name was the Order of Christ.

In Campo de Calatrava, the martyrs prevailed over the apostles. There was a clear predominance of dedications to St. Sebastian (four churches, twenty-six hermitages, and fourteen confraternities). The number of hermitages dedicated to him was triple the number of those dedicated to other saints. St. John the Baptist was also highly revered in Campo de Calatrava, especially in the confraternities (thirteen). This may be explained by the popularity of his nativity feast (June 24), which had strong liturgical roots as well as popular and pagan antecedents (Ladero Quesada 2004: 57-58). Furthermore, St. John the Baptist was one of the few saints to be afforded two liturgical feasts, one marking his birth and the other his martyrdom. Below the devotional level of St. Sebastian and St. John, the worship of other saints was widely dispersed. Among the holy helpers, St. Christopher, St. Catherine, and St. Blaise were venerated in churches (two), hermitages (seven), and confraternities (three), in keeping with their popularity as protectors all across Europe, especially in rural environments.[45] Other martyrs were St. Quiteria (four hermitages and one parish church), St. Nicasius (two hermitages). St. Quiricus, St. Julitta, St. Fabian, St. Lucy, and St. Marina each had a single hermitage or confraternity dedicated to them.

In the case of Campo de Calatrava, apostles such as St. Bartholomew and St. James the Greater are worth noting, not for the number of churches dedicated to them (two and one respectively), but for the number of hermitages (seven and five) and confraternities (ten and eight). This phenomenon linked to hermitages and confraternities, which functioned as volunteer lay organizations, enhanced the status of the parish’s patron saints. The lesser importance attached to St. Peter, the princeps apostolorum, by the Order of Calatrava is quite notable when compared with his important status in the Orders of Avis and Christ. Other apostles did not have parish churches dedicated to them, but they did have hermitages and confraternities: St. Simon, St. Jude, St. Barnabas, and St. Paul. However, St. Andrew and St. James the Greater did have churches in important locations, such as El Moral and Carrión, and St. Peter was the patron saint of the second parish in Daimiel. Although the Order of Avis was affiliated to the Order of Calatrava, it reflected a number of quite singular options. Indeed, the apostles were invoked at seven hermitages (four dedicated to St. Peter, and three dedicated to St. James the Greater) and at just one church (St. James the Greater).

As mentioned above, the Order of Christ attributed more importance to the celebration of the apostles as the patron saints of their churches. One of the reasons for this may be the name of the order itself-Order of Christ. Paying homage to Christ, it had a higher number of churches dedicated to the apostles, the people closest to the human figure of Christ.

The evangelists, on the other hand, had very little representation: St. Mark at just one hermitage in the Order of Avis, and St. Matthew and St. John each at just one church, both belonging to the Order of Christ. Similarly, in Campo de Calatrava, only one hermitage is documented as being dedicated to St. Matthew. St. Mark was the patron saint of seven hermitages, four confraternities, and just one church. As his feast day was on April 25, his veneration formed part of the spring farming cycle and corresponded to the Major Litanies, a procession in which prayers of pagan origin were recited to ask for good harvests, contributing to the sacralization of the rural environment (Christian 1991: 143 ff; Vauchez 1988: 21-34).

In turn, dedications to warrior saints were less frequent than those to Christ, the Virgin Mary and the apostles (Josserand 2016: 197). Nevertheless, the Virgin was also linked to the spiritual background of warrior saints, namely in Campo de Calatrava: St. Mary of Peace and St. Mary of the Martyrs, the latter being located in the Convent of Calatrava itself, next to the graveyard of the martyrs where the bodies of the Calatrava knights who died in the battle of Alarcos in 1195 were buried. The most venerated warrior saints were St. Sebastian, St. Michael, and St. James the Greater. Above all, St. Sebastian was the most revered (five hermitages and one confraternity in the Order of Avis; one church and three hermitages in the Order of Christ; and four churches, twenty six hermitages and fourteen confraternities in the Order of Calatrava), followed by St. James the Greater (one church and three hermitages in the Order of Avis, two churches and one hermitage in the Order of Christ; five hermitages and eight confraternities in the Order of Calatrava), and by St. Michael (four churches in the Order of Christ; one hermitage in the Order of Avis; and only one hermitage and two confraternities in the Order of Calatrava). St. George was also present as a patron saint in the Order of Calatrava,[46] namely in a confraternity and in a parish church close to the central convent of the order. The predominance of St. Sebastian could be the result of his status as a protector against epidemics and the plague. To further underline his importance, we can point to the great number of rural hermitages dedicated to him in Campo de Calatrava, as well as the vows that were made to him in the municipalities. From a theoretical point of view, there was a tendency to replace St. Sebastian with St. Roch, as the protector against the plague, a movement that was already documented in Western Europe in the fifteenth century (Marques 2000: 234). Nevertheless, this replacement did not occur in the context of the Cistercian military orders in Portugal. There is only one reference in Portugal to St. Roch being represented on a high altar of the Order of Avis. In Campo de Calatrava, there was a hermitage and a confraternity named in his honor. Furthermore, St. Roch represented a new hagiographic model, displaying both an evangelical and a penitential spirituality. His commemoration was closely linked to pilgrimages, the eremitic life, voluntary poverty, service to the sick, and the imitation of the ideal of Christ. Significantly, the devotion to St. Sebastian continued to increase in the first decades of the sixteenth century in Campo de Calatrava. Thus, the military orders seem to have maintained more traditional devotional models. So, in Iberia, it seems to make greater sense to classify St. James (Santiago) as a warrior saint rather than as an apostle in this context, in keeping with the legend of Santiago Matamouros, which formed part of the reconquest process.

Roman and Eastern martyrs also belonged to the set of patron saints, notably St. Sebastian, St. Catherine, St. Lawrence, St. Blaise, and St. John the Baptist in Portugal, followed by the occasional veneration of St. Stephen, St. Vincent, St. Andrew, St. Mamas, and St. Margaret. Seen from a methodological perspective, some of them might have certain qualities that could be linked to other categories. Iberian martyrs were almost completely absent, both in Portuguese territories and in Campo de Calatrava. The exception for Portugal is St. Irene of Tomar, who was born close to the main convent of the Order of Christ. The same could be said for local hermitic saints and local bishops. There are only two saints of Visigothic and Mozarabic origin: St. Ildephonsus, the Archbishop of Toledo in the seventh century (657-667), who was venerated both in Portugal and in Castile (one church in the Order of Christ and one hermitage in the Order of Calatrava), and St. Servandus, a fourth-century Spanish martyr, with one hermitage in Campo de Calatrava. St. Servandus was venerated at the Mozarabic Church[47] and at the Roman Rite Church in Toledo (Ruiz Gómez 2002: 127). In Campo de Calatrava, St. Ildephonsus reflected the influence of Toledan piety in the archdiocese of Toledo, the jurisdictional tutor of the Order of Calatrava. The hagiography of these three military orders has an international profile and reveals a very different panorama when compared with the north of Spain, where monasteries and churches celebrated Paleo-Christian and Mozarabic martyrs, such as St. Pelagius and St. Leocadia, among others, as well as sixth to eighth-century hermits and bishops, such as St. Aemilius, St. Felix, St. Prudentius, and St. Valerius (Cantera Montenegro 1985: 48-51).

Finally, the visitations identified more individual references to certain saints without a common label. For example, there were monastic saints, like St. Antony the Great, the protector of rural animals and a protector against fire (one hermitage in the Order of Christ, one high altar in the Order of Avis, seven hermitages and seven confraternities in the Order of Calatrava) and also St. Mary of Egypt, a sixth-century oriental anchorite saint and a penitent sinner (Román López 1999: 153). The former was highly venerated for her miracles at a rural hermitage that became a regional place of devotion and was also turned into a village.[48] The Archangel St. Michael, the paradigm of the fight against the devil and the leader of the souls to Heaven (Cavedo 2000: II, 1720-1721), had four churches and two high altars in the Order of Christ, and one hermitage and one high altar in the Order of Avis, but only one hermitage and two confraternities in the Order of Calatrava. The virtual absence of St. Francis (only one hermitage in Calatrava) is not surprising, given that the military orders often viewed with suspicion the establishment of mendicant orders in their domains (Javier Rubio 2018: 540). Furthermore, the military orders wished to implement their prerogative of granting or refusing a license for new convents.[49] On the other hand, the mendicant orders had little interest in establishing themselves in rural areas, where the main seigniories of the military orders were located. Nevertheless, St. Antony of Padua[50] had one church dedicated to him and two high altars in the Order of Avis, as well as one hermitage and one high altar in the Order of Christ. The veneration of two Doctors of the Church, St. Gregory of Nazianzus (three hermitages and one confraternity) and St. Augustine (one hermitage and three confraternities) is documented in relation to the Order of Calatrava. Both were regarded as protectors against the plagues of locusts that wreaked havoc on the crops that the people had planted (Christian 1991: 60-62 ff.).

This proliferation of patron saints does not reveal any particular trend and is difficult to interpret. One possible hypothesis is that the diversity of hermitages in the Order of Avis, which was similar to the diversity found in the Order of Calatrava, may reflect the jurisdictional link between these two orders. Furthermore, in the case of the Order of Christ, the great amplitude of the devotions could also reflect the former Templar heritage. When inheriting the churches and chapels of the Templars, the knights of the Order of Christ maintained the same patron saints, respecting a longstanding devotion. Even though this is a highly interesting matter, it is not possible to assess the full importance of the inherited patron saints venerated in previous times based on the sources analyzed in this paper.

In many cases, the high altars were dedicated to the same patron saint who had given his or her name to the church. However, on some occasions, the patron saint of the church did not coincide with the saint to whom the high altar was dedicated. Without any clear explanation, those churches whose invocation was not represented on the respective high altar were recorded in the written sources with great surprise on the part of the visitors. For example, the Virgin Mary with the Child Jesus was invoked on the high altar of the church of St. Blaise in Figueira, whereas the altar of St. Blaise was placed on the south side of the church.[51] The church of St. Martin in Pombal had an old high altar that did not contain any reference to the patron saint of the church.[52] And Our Lady was invoked on the high altar of the Igreja de São João da Praça in Redinha.[53]

One final indicator of the hagiographic devotion of the military orders consists of the vows, documented for Campo de Calatrava in the “Relaciones topográficas de Felipe II.” We found eighteen vows from the end of the fifteenth century until 1535. Vows to saints took the form of local and civic promises to celebrate their feasts and to express gratitude to them, in the hope of achieving their protection. These favors were usually related to natural disasters, such as plagues of locusts, droughts, frosts, fires, rabies, etc., and to the protection of animals. They not only constitute an interesting testimony to the strength of rural devotion, but also confirm the sense of protection against the plague that the people attributed to St. Sebastian. The popular faith was reinforced more by the protection that these saints could guarantee against misfortunes than by the impact of their historical and liturgical status (whether they were martyrs or apostles).

Conclusions

After analyzing the data, it is possible to identify some remarkable trends. In quantitative terms, the Order of Avis was more akin to the Order of Calatrava than to the Order of Christ. The institutional and legal links between the Orders of Avis and Calatrava may well have accounted for this phenomenon, as has already been explained. The higher level of episcopal control over the sacred places managed by the Order of Christ and even the name of this institution itself should further confirm this interpretation.

The analysis of the patron saints identified during the course of the visitations reveals a prevalence of traditional, universally-oriented devotions. The close links between the orders and the Papacy (rather than with the bishoprics) may well explain the promotion of a universal devotion and a major liturgical profile when compared with the absence of local traditions. Furthermore, the supranational dimension of some of these institutions would have favored a wider frame of reference.

Marian spirituality, Christological worship, and hagiographic models are the most common references. In particular, attention was paid to saints who were martyrs, apostles, evangelists, and holy helpers. Some Fathers of the Church, venerated for their protection of the harvests, were also venerated in the Order of Calatrava.

Local pre-Islamic or Mozarabic saints were practically absent. In Campo de Calatrava, the lack of previous archaisms can be explained by the late organization of the Roman rite in this territory. This suggests an implantation of the Church network ex novo, a circumstance which does not seem to have been relevant in Portugal. Furthermore, the authority of the Toledan Church had scant hagiographic influence in this seigniory of Calatrava, perhaps as a result of the ecclesiastical jurisdictional conflict between the Toledan archdiocese and this order. The multiple invocations of the Virgin played an important role in some communities.

The traditional Marian profile of the devotion of these orders is consistent with the rural and non-urban nature of these Castilian and Portuguese settlements (Vauchez 1994: 156-157.)[54] The venerated saints were widely popular and had liturgical feasts as well as a firmly established reputation as protectors of the rural world. Finally, the minimal presence and influence of the mendicant orders in the territory of the military orders (whose establishment was generally obstructed, at least in Castile) might have hindered the spread of the new models of holiness.

Overlooking the dangers of excessive generalizations, this approach paints a picture of the patron saints venerated in the different places of devotion under the three Benedictine military orders. Assessing their impact at the spiritual level implies making a distinction between the devotional profile and the traditions imposed on the members of the orders and those that were practiced by the local population, who attended the sacred places of worship in those territories. It also seems that the orders respected the devotional preferences of the congregation. Despite the recommendations made by the visitors to promote some images of St. Benedict and St. Bernard, the devotion to both saints seems not to have increased.

From a general point of view, the historiography states that the models of holiness changed between the twelfth and the fifteenth centuries, from the inimitable heroic martyr to more imitable models (Manselli 1975) that were closer to the essential aim of serving the poor. Thus, saints were not honored so that they might be imitated, but, instead, so that the worshippers might benefit from their protection. Between the eleventh and the thirteenth centuries, the veneration that was associated with voluntary poverty, asceticism, charity, and hard work enriched this scenario. From the end of the thirteenth to the fifteenth century, religious laywomen and mendicant saints, namely the mendicant lay Dominicans (Tertiaries), increased in importance (Vauchez 1994: 254 and 449-478). Furthermore, the saints’ calendar had been steadily increasing since the thirteenth century. Apart from the traditional saints (those dating from the time of the origins of Christianity and the first centuries of the Church), the people preferred saints that were closer to themselves. In parallel to this, Christological worship was becoming more popular. The Corpus Christi procession was a clear expression of this all over Europe. All these changes reflected new trends in the models of holiness.

This evolution was not clearly evident in the territories of the military orders from the documentation examined in the course of this study. It will therefore be necessary to deepen the analysis and go further in future studies, using other indicators, such as the cults of relics, the images placed on secondary altars, and the data relating to miracles, among other phenomena. In fact, the analysis of the patron saints and of the images on the high altars is not enough to apply this reasoning to the specific case of the three Benedictine military orders. To clarify the question of the influence of the military orders on the religiosity of the Christians in their seigniories, yet more in-depth research is still needed. Considering the hypothesis that the military orders would take into account the spiritual tendencies of the late Middle Ages, it is impossible to extrapolate these and then apply them to all members of the local congregation (Torres Jiménez 2006: 464). In short, it is difficult to determine the extent to which the parishioners of the seigniories were prepared to adhere to new tendencies. In seeking to achieve a better knowledge of these issues, the research framework should be reinforced with the study of catechetical practices, the spiritual guidelines laid down by the members of the orders, and the multiple elements of worship inside the sacred buildings of the military orders.

REFERENCES

Abou-el-Haj, Barbara (1997). The Medieval Cult of Saints. Formations and Transformations. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

Acta Sanctorum Full-Text Database (1999-2002). Cambridge: ProQuest Information and Learning Company. [ Links ]

Archivo Histórico Nacional in Madrid (AHN), Órdenes Militares (OOMM), Consejo de Órdenes (Consejo), Legajo (Leg.) 6075; 6076; 6078; 6079; 6080; 6109; 6110; Lib. 1067C. [ Links ]

Ayala Martínez, Carlos de (2014). “Ideología, espiritualidad y religiosidad de las órdenes militares en época de Alfonso VIII. El modelo santiaguista.” Las Navas de Tolosa 1212-2012: miradas cruzadas. Patrice Cressier and Vicente Salvatierra (eds.). Jaén: Universidad de Jaén, 331-346. [ Links ]

Ayala Martínez, Carlos de (2015). Órdenes militares, monarquía y espiritualidad militar en los Reinos de Castilla y León. Granada: Universidad de Granada. [ Links ]

Bergonzini, Massimo (2015). Il Culto mariano e immaculista della monarchia di Spagna: l’ambasciata romana di D. Luis Crespi de Borja (1659-1661). Porto: CITCEM. [ Links ]

Boglioni, Pietro (1972). “La religion populaire au Moyen Âge. Éléments d’un bilan.” Les religions populaires (Colloque international, 1970). Benoit Lacroix and Pietro Boglioni (eds.), Québec: Les Presses de l'Université Laval, 55-56. [ Links ]

Brown, Peter (1984). The Cult of the Saints. Its Rise and Function in Latin Christianity. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [ Links ]

Cantera Montenegro, Margarita (1985). “Advocaciones religiosas en la Rioja medieval,” Anuario de Estudios medievales 15: 39-61. [ Links ]

Carraz, Damien and Esther Dehoux (eds.) (2016). Images et ornements autour des ordres militaires au Moyen Âge. Culture visuelle et culte des saints (France, Espagne du Nord, Italie). Toulouse: Presses universitaires du Midi. [ Links ]

Carreiras, José Albuquerque and Carlos de Ayala Martínez (eds.) (2015). Cister e as Ordens Militares na Idade Média: Guerra, Igreja e Vida Religiosa. Tomar: Associação Portuguesa de Cister. [ Links ]

Cavedo, R. (2000). “San Miguel arcángel.” Diccionario de los santos, II. Claudio Leonardi, Andrea Riccardi and Gabriella Zarri (eds.). Madrid: San Pablo, 1720-1721. [ Links ]

Chiesa, P. (2000). “San Blas.” Diccionario de los santos, I. Claudio Leonardi, Andrea Riccardi and Gabriella Zarri (eds.). Madrid: San Pablo, 378. [ Links ]

Christian, Jr., William (1990). Apariciones en Castilla y Cataluña (siglos XIV-XVI). Madrid: Nerea. [ Links ]

Christian, Jr., William (1991). Religiosidad local en la España de Felipe II. Madrid: Nerea. [ Links ]

Costa, Paula Pinto and Joana Lencart (2017). “As igrejas das Ordens Religioso-Militares entre 1220 e 1327: das inquirições régias aos documentos normativos.” Genius Loci. Lugares e significados, vol. 1. Lúcia Rosas, Ana Cristina Sousa and Hugo Barreira (eds.). Porto: CITCEM, 57-69. [ Links ]

Deuffic, Jean-Luc (ed.) (2006). Reliques et sainteté dans l’espace medieval. Saint Dénis: Pecia. [ Links ]

Dias, Pedro (1979). Visitações da Ordem de Cristo de 1507 a 1510. Aspectos artísticos. Coimbra: Instituto de História da Arte da Faculdade de Letras da Universidade de Coimbra. [ Links ]

Diccionario de los santos (2000). Claudio Leonardi, Andrea Riccardi and Gabriella Zarri (eds.). Madrid: San Pablo. [ Links ]

Donnini, M. (2000). “Santa Catalina de Alejandría.” Diccionario de los santos, I. Claudio Leonardi, Andrea Riccardi and Gabriella Zarri (eds.). Madrid: San Pablo, 447. [ Links ]

Fernandes, Carla Varela (ed.) (2015). Imagens e Liturgia na Idade Média. Lisboa: Secretariado Nacional para os Bens Culturais da Igreja. [ Links ]

Fernandes, Isabel Cristina (ed.) (2010). Ordens Militares e Religiosidade, Homenagem ao Professor José Mattoso. Palmela: Município de Palmela/GEsOS. [ Links ]

Fuguet, Joan and Carme Plaza (2016). “Culto a los santos y lucha contra el Islam en las órdenes militares de la Corona Catalano-aragonesa.” Images et ornements autour des ordres militaires au Moyen Âge. Damien Carraz and Esther Dehoux (eds.). Toulouse: Presses Universitaires du Midi, 155-180. [ Links ]

García de Cortázar, José Angel (2012). Historia religiosa del Occidente medieval (Años 313-1464). Madrid: Akal. [ Links ]

Guiance, Ariel (2014). Legendario cristiano: creencias y espiritualidad en el pensamiento medieval. Buenos Aires: Consejo nacional de investigaciones cientificas y técnicas, Instituto multidisplinario de historia y ciencias humanas. [ Links ]

Gutton, Francis (1955). La Orden de Calatrava. Madrid: El Reino. [ Links ]

Javier Rubio, Carlos (2018). “El establecimiento de la regular observancia en La Mancha. Los franciscanos en Villanueva de los Infantes.” La Iglesia y el mundo hispánico en tiempos de Santo Tomás de Villanueva (1486-1555). Francisco Javier Campos and Fernández de Sevilla (eds.). San Lorenzo del Escorial: Ediciones Escurialenses, 539-562. [ Links ]

Josserand, Philippe (2004). Église et pouvoir dans la peninsule ibérique. Les ordres militaires dans le royaume de Castille. Madrid: Casa de Velázquez, 1252-1369. [ Links ]

Josserand, Philippe (2016). “Le regard d’un historien.” Images et ornements autour des ordres militaires au Moyen Âge. Culture visuelle et culte des saints (France, Espagne du Nord, Italie). Damien Carraz and Esther Dehoux (eds.). Toulouse: Presses Universitaires du Midi, 195-201. [ Links ]

Josserand, Philippe, Luís Filipe Oliveira, and Damien Carraz (eds.) (2015). Élites et ordres militaires au Moyen Âge. Rencontre autour d’Alain Demurger. Madrid: Casa de Velázquez. [ Links ]

Jounel, Pierre (1992). “El culto de María.” La Iglesia en oración. Introducción a la liturgia. Aimé Georges Martimort (ed.). Barcelona: Herder, 1024-1039. [ Links ]

“La construcción de la santidad femenina de los siglos XV al XVII (2015).” Medievalia. Revista d’Estudis Medievais. María Morrás (coord.). Universidad Autónoma de Barcelona. Available at http://revistes.uab.cat/medievalia/issue/view/22 [ Links ]

Ladero Quesada, Miguel Ángel (2004). Las fiestas en la cultura medieval. Barcelona: Areté. [ Links ]

Los pueblos de Ciudad Real en las Relaciones Topográficas de Felipe II (2009). Francisco Javier Campos and Fernández de Sevilla (eds.). 2 vols. Ciudad Real: Imprenta Provincial. [ Links ]

Manselli, Raoul (1975). La religion populaire au Moyen Âge: Problèmes de méthode et d'histoire. Montréal: Institut d’Études Médiévales. [ Links ]

Marques, L. C. L. (2000). “San Roque.” Diccionario de los santos, II. Claudio Leonardi, Andrea Riccardi, and Gabriella Zarri (eds.). Madrid: San Pablo, 2001. [ Links ]

Mateo, M. C. (2000). “San Raimundo de Fitero.” Diccionario de los santos, II. Claudio Leonardi, Andrea Riccardi and Gabriella Zarri (eds.). Madrid: San Pablo, 1957-1959. [ Links ]

Nicholson, Helen (2005). “Saints venerated in the Military Orders.” Selbstbild und Selbstverständnis der geistlichen Ritterorden. Jürgen Sarnowsky and Roman Czaja (eds.). Toruń, 91-113. [ Links ]

Pablo Maroto, Daniel de (1998). Espiritualidad de la Alta Edad Media. Madrid: Editorial de Espiritualidad. [ Links ]

Pérez-Embid Wamba, Javier (2017). Santos y milagros. La hagiografía medieval. Madrid: Síntesis. [ Links ]

Pinius. “Liturgiae antiquae hispanae Tractatus,” n. 454. Acta Sanctorum, t. VI, julii, p. 89, in Acta Sanctorum Full-Text Database [cited on January 20, 2017]: available at http://gateway.proquest.com/openurl?url_ver=Z39.88-2004&res_dat=xri:acta&rft_dat=xri:acta:ft:all:Z400008003 [ Links ]

Rades y Andrada, Fray Francisco de (1980) [1572]. Crónica de la Orden de Calatrava. Toledo, Edic. facsímil, Ciudad Real: Diputación Provincial y Museo de Ciudad Real. [ Links ]

Román López, Maria Teresa (1999). Diccionario de los santos. Madrid: Alderabán. [ Links ]

Rosas, Lúcia and Paula Pinto Costa (2014). “Vera Cruz de Marmelar: a intervenção de Afonso Peres Farinha.” População e Sociedade, nº 22: 177-192. Available in https://www.cepese.pt/portal./pt/populacao-e-sociedade/edicoes/populacao-e-sociedade-n-o-22 [ Links ]

Ruiz Gómez, Francisco (2002). “El antiguo reino de Toledo y las tierras de La Mancha en los siglos XI-XIII.” Castilla-La Mancha medieval. Ricardo Izquierdo Benito (ed.). Ciudad Real: Manifesta, 73-139. [ Links ]

Scattigno, A. (2000). “Santa María Magdalena.” Diccionario de los santos, II. Claudio Leonardi, Andrea Riccardi, and Gabriella Zarri (eds.). Madrid: San Pablo, 1619. [ Links ]

Scorza Barcellona, F. (2000). “San Sebastián.” Diccionario de los santos, II. Claudio Leonardi, Andrea Riccardi, and Gabriella Zarri (eds.). Madrid: San Pablo, 2031. [ Links ]

Tombos da Ordem de Cristo: Comendas da Beira interior centro (1508). Lisboa: Centro de Estudos Históricos da Universidade Nova de Lisboa, 2009. [ Links ]

Tombos da Ordem de Cristo: Comendas da Beira interior sul (1505). Lisboa: Centro de Estudos Históricos da Universidade Nova de Lisboa, 2009. [ Links ]

Tombos da Ordem de Cristo: Comendas do médio Tejo (1504-1510). Lisboa: Centro de Estudos Históricos da Universidade Nova de Lisboa, 2005. [ Links ]

Torre do Tombo (TT), Ordem de Avis e Convento de São Bento de Avis (OA), liv. 13; 14; 15; 35. [ Links ]

Torre do Tombo (TT), Ordem de Cristo/Convento de Tomar (OC/CT), mç. 13, nº 2, doc. 2; mç. 44; mç. 56; mç. 66; n.º 132; liv. 268. [ Links ]

Torres Jiménez, Raquel (1996). “Modalidades de jurisdicción eclesiástica en los dominios calatravos castellanos (siglos XII-XIII).” Alarcos, 1195. Ricardo Izquierdo and Francisco Ruiz (eds.). Cuenca: Universidad de Castilla-La Mancha, 433-458. [ Links ]

Torres Jiménez, Raquel (2000). “Liturgia y espiritualidad en las parroquias calatravas (siglos XV-XVI).” Las Órdenes Militares en la Península Ibérica, I: Edad Media. Ricardo Izquierdo and Francisco Ruiz (eds.). Cuenca: Universidad de Castilla-La Mancha, 1087-1116. [ Links ]

Torres Jiménez, Raquel (2001). “Devoción eucarística en el Campo de Calatrava al final de la Edad Media. Consagración y elevación.” Memoria Ecclesiae, XX. Religiosidad popular y Archivos de la Iglesia, I. Agustín Hevia Ballina (ed.). Oviedo: Asociación de Archiveros de la Iglesia en España, 293-328. [ Links ]

Torres Jiménez, Raquel (2005a). “La influencia devocional de la Orden de Calatrava en la religiosidad de su señorío durante la Baja Edad Media.” Revista de las Órdenes Militares, 3: 37-74. [ Links ]

Torres Jiménez, Raquel (2005b). Formas de organización y práctica religiosa en Castilla-La Nueva. Siglos XIII-XVI. Señoríos de la Orden de Calatrava. Madrid: Universidad Complutense. [ Links ]

Torres Jiménez, Raquel (2006). “Notas para una reflexión sobre el cristocentrismo y la devoción medieval a la Pasión y para su estudio en el medio rural castellano.” Hispania Sacra, LVIII: 449-487. [ Links ]

Torres Jiménez, Raquel (2010). “La religiosidad calatrava en sus primeros tiempos.” El nacimiento de la Orden de Calatrava. Primeros tiempos de expansión (siglos XII y XIII). Ángela Madrid Medina and Luis Rafael Villegas Díaz (eds.). Ciudad Real: Instituto de Estudios Manchegos, 261-302. [ Links ]

Torres Jiménez, Raquel (2013). “Ermitas y religiosidad popular: el santuario de Cortes.” Alcaraz, del Islam al consejo castellano. Aurelio Pretel (ed.). Alcaraz: Ayuntamiento, 187-214. [ Links ]

Torres Jiménez, Raquel (2016-2017). “La devoción mariana en el marco de la religiosidad del siglo XIII.” Alcanate, 10: 23-59. [ Links ]

Torres Jiménez, Raquel (2018). “El ‘templo vestido’. Espacios, liturgia y ornamentación textil en las iglesias del Campo de Calatrava (1471-1539).” Las tres religiones en la Baja Edad Media peninsular. Espacios, percepciones y manifestaciones. Luis Araus Ballesteros and Juan Antonio Prieto Sayagués (eds.). Madrid: La Ergástula, 145-160. [ Links ]

Torres Jiménez, Raquel and Francisco Ruiz Gómez (eds.) (2016). Órdenes militares y construcción de la sociedad occidental. Cultura, religiosidad y desarrollo social de los espacios de frontera (siglos XII-XV). Madrid: Sílex. [ Links ]

Vauchez, André (1988). “Liturgie et culture folklorique: les rogations dans la Légende Dorée de Jacques de Voragine.” Fiestas y liturgia. Fêtes et liturgie. Alfonso de Esteban Alonso and Jean-Pierre Étienvre (eds.). Madrid: Casa de Velázquez, 21-34. [ Links ]

Vauchez, André (1994). La sainteté en Occident aux derniers siècles du Moyen Âge. D’après les procès de canonisation et les documents hagiographiques. Rome: École Française de Rome. [ Links ]

Vauchez, André (2004). “Conclusion.” Procès de canonisation au Moyen Âge: aspects juridiques et réligieux. Gábor Klaniczay (ed.). Rome: École Française de Rome, 357-363. [ Links ]

Vilar, Hermínia (2018). “Bispos na conquista de Ceuta ou os possíveis significados de uma ausência.” As Décadas de Ceuta (1385-1460). Maria Helena da Cruz Coelho and Armando Luís Carvalho Homem (eds.) Lisboa: Caleidoscópio, 93-108. [ Links ]

Villegas Díaz, Luis Rafael (1999). “Calatravensis militia, cisterciensis ordinis.” Cistercium, 30: 547-562. [ Links ]

Vorágine, Santiago de (2016). Leyenda Dorada. Translated by Fray J. M. Macías, 2 vols., Madrid: Alianza Editorial. [ Links ]

Received for publication: 09 October 2019. Accepted in revised form: 16 January 2020

Recebido para publicação: 09 de Outubro de 2019. Aceite após revisão: 16 de Janeiro de 2020

NOTES

[4] This study was carried out under the scope of the project entitled Military Orders and Religiosity in the Medieval West and the Latin East (12th-mid-16th centuries). Ideology, Memory and Material Culture (Reference PGC2018-096531-B-I00), funded by the Spanish Ministry of Science, Innovation and Universities (MCIU/AEI/FEDER, UE).

[5] Tombos da Ordem de Cristo: Comendas da Beira interior centro (1508), 134.

[6] Tombos da Ordem de Cristo: Comendas da Beira interior sul (1505), 189.

[7] Answers to the survey ordered by Philip II, dating from 1575, 1576 and 1579. Campos and Fernández de Sevilla, 2009.

[8] TT, Ordem de Avis e Convento de São Bento de Avis (OA), liv. 13.

[9] TT, OA, liv. 15.

[10] TT, OA, liv. 14.

[11] TT, OA, liv. 35.

[12] TT, Ordem de Cristo/Convento de Tomar (OC/CT), mç. 13, nº 2, doc 2; TT, OC/CT, mç. 44, s./nº; TT, OC/CT, mç. 56.

[13] TT, OC/CT, mç. 66, nº 2.

[14] TT, OC/CT, nº 132. Publ. Dias, Visitações da Ordem de Cristo de 1507 a 1510, 3-192.

[15] TT, OC/CT, liv. 268.

[16] 1471, 1491 and 1493 visitations at the Archivo Histórico Nacional in Madrid (AHN), Órdenes Militares (OOMM), Consejo de Órdenes (Consejo), Legajo (Leg.) 6075.

[17] 1495 and 1500 visitations at AHN, OOMM, Consejo, Leg. 6109.

[18] AHN, OOMM, Consejo, Leg. 6110.

[19] AHN, OOMM, Consejo, Leg. 6076 y 6110.

[20] AHN, OOMM, Consejo, Leg. 6080.

[21] 1537-1538 and 1539 visitations at AHN, OOMM, Consejo, Leg. 6079.

[22] Since some visitations refer to the same places, many references to patron saints are repeated. In this case, the saint was counted only once.

[23] TT, OC/CT, liv. 268, f. 56v.

[24] In these cases, we considered two invocations for two parish churches. In Torralba, for example, the new Trinity parish church replaced another previous parish church, which was smaller and more distant from the village, dedicated to Santa Maria la Blanca (literally, St. Mary the White, or St. Mary of the Snow), which then remained as a hermitage. AHN, OOMM, Consejo, Leg. 6079, nº 23, ff. 139r-139v.

[25] Tombos da Ordem de Cristo: Comendas do médio Tejo (1504-1510), 2: 11.

[26] AHN, OOMM, Consejo, Leg. 6.076, nº 20a, f. 299r.

[27] Throughout the Middle Ages, Mary Magdalene’s evangelical traits were overshadowed by the focus on her sinful life and her status as a penitent sinner.

[28] In his will, Pedro Girón (1445-66), the Master of the Order of Calatrava, commissioned a mass in his memory at the Convent of Calatrava, to be celebrated on each day of the Exaltation of the Holy Cross. Rades y Andrada, Crónica de la Orden de Calatrava, f. 77v.

[29] Rades y Andrada, Crónica de la Orden de Calatrava, ff. 10, 20v, 33.

[30] The order issued by the visitors in 1495, concerning the parish church of Alcolea, was re-issued in 1502. AHN, OOMM, Consejo, Leg. 6110, nº 17, f. 211. Further examples can be found in AHN, OOMM, Consejo, Leg. 6075, nº 11, f. 252; 1502; AHN, OOMM, Consejo, Leg. 6110, nº 16, f. 205v. In one specific church, St. Bernard was painted in a dark habit instead of a white one. AHN, OOMM, Consejo, Leg. 6075, nº 14, f. 84.

[31] TT, OA, liv. 15, f. 21v.

[32] 100 masses per year were to be said at St. Benedict’s chapel at the Alcázar in Elvas (TT, OA, liv. 13, f. 4v).

[33] TT, OC/CT, liv. 268, f. 25v.

[34] TT, OC/CT, liv. 268, f. 39v.

[35] TT, OC/CT, liv. 268, f. 54.

[36] TT, OC/CT, mç. 66, nº 2, f. 115.

[37] TT, OC/CT, mç. 66, nº 2, f. 119v.

[38] TT, OC/CT, liv. 15, ff. 29-30.

[39] TT, OC/CT, liv. nº 15, f. 77v.

[40] TT, OC/CT, liv. 268, f. 34v.

[41] E.g. the Virgin and Child at the parish church in Valenzuela. In 1502, the visitors ordered that all the clothes be sold and the images be painted in blue and gold (AHN, OOMM, Consejo, Leg. 6075, nº 31, f. 318v). By 1549, these orders had still not been obeyed (AHN, OOMM, Consejo, Leg. 6080, nº 4, ff. 100-100v).

[42] Ordered in his will. To that end, he donated nine goats to the church. AHN, OOMM, Consejo, Leg. 6075, nº 29, f. 172v.

[43] One fraternity bore his name. AHN, OOMM, Consejo, Leg. 6078, nº 1, f. 37v.

[44] AHN, OOMM, Consejo, Leg. 6078, nº 1, fol. 43-44. There was a St. Sylvester fraternity in Almagro from 1486 onwards. AHN, OOMM, Consejo, Leg. 6075, nº 7, ff. 126-126v.

[45] St. Catherine, the protectress against sudden death, was also the protectress of trades linked to the use of wheels: cartwrights and millers, for example (Donnini, “Santa Catalina de Alejandría,” I, 447). St. Blaise had a hagiographic tradition closely related to the rural and pastoral sphere; he was also associated with the protection of animals and with protection against throat problems (Chiesa, “San Blas,” I, 377-378). According to Latin and Greek traditions, St. Christopher was a soldier and a martyr in Antioch (Su Passio, in Acta Sanctorum Full-Text Database, Cambridge, ProQuest Information and Learning Company, 1999-2002 [cited on January 20, 2017]). However, his hagiographic tradition as the giant who carried the Baby Jesus across the river became popular thanks to “The Golden Legend” by Voragine, (Leyenda dorada, I, 405-408), which turned him into the patron saint of travelers.

[46] St. George is not totally absent in Portugal; he was venerated at two altars of the Order of Christ. These altars will be the subject of a separate study, due to be published shortly.

[47] Pinius. “Liturgiae antiquae hispanae Tractatus,” n. 454, in Acta Sanctorum, t. VI, julii, p. 89.

[48] This was the village called Luciana in the last quarter of the fifteenth century. Relaciones topográficas de Felipe II, II, 548-549.

[49] This was the case with the Convent of Saint Francis at Villanueva de los Infantes, in the seigniory of the Order of Santiago in La Mancha. The master Alonso de Cárdenas authorized its foundation in 1483 on condition that the new convent would come under the jurisdiction of the Military Order of Santiago (AHN, OOMM, Lib. 1067C, f. 314).

[50] Or St. Antony of Lisbon, in Portugal.

[51] TT, OA, liv. 15, ff. 68-68v.

[52] TT, OC/CT, liv. 268, f. 5v.

[53] TT, OC/CT, liv. 268, f. 32v.

[54] Vauchez associates the rural sphere with a greater devotional archaism and a reduced sensitivity and less openness towards new models of holiness.