Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Indicators

-

Cited by SciELO

Cited by SciELO -

Access statistics

Access statistics

Related links

-

Similars in

SciELO

Similars in

SciELO

Share

e-Journal of Portuguese History

On-line version ISSN 1645-6432

e-JPH vol.16 no.1 Porto 2018

https://doi.org/10.7301/Z0513WRQ

INSTITUTIONS & RESEARCH

Whose Colonial Project? Angolan Elites and the Colonial Exhibitions of the 1930s: Notes on the Special Magazine Edition of A província de Angola, August 15, 1934

Torin Spangler1

1 PhD Student, Department of Portuguese and Brazilian Studies, Brown University (Providence, RI, U.S.A.); E-Mail: torin_spangler@brown.edu

ABSTRACT

A major objective of early exhibitions during the Estado Novo was to project an image of universal support for the newly reformulated colonial project in both the metropole and the colonies. Although recent research has shed new light on the 1930s exhibitions from a metropolitan perspective, accessing voices from within colonial spaces can often prove more difficult. This article examines the specific case of the Angolan white settler community and the local independent press, observing the complexities of their involvement in, and reactions to, exhibitions in Angola and Portugal. In this context, the special edition of the newspaper A Província de Angola (August 15, 1934), published on the occasion of the Exposição Colonial do Porto, will be used as a central vehicle of intertextual exploration in an effort to uncover the complex interplay between local collaboration in colonial exhibitions and resistance to hegemonic control of discourses and images within the empire.

Keywords: Colonial exhibitions; Angola; Portugal; press; imperial identities

RESUMO

O presente artigo examina as reações de colonos angolanos à 1ª Exposição Colonial Portuguesa (Porto, 1934), utilizando o Número Extraordinário do jornal A Província de Angola (15 Agosto, 1934) como veículo central de exploração intertextual. Nesta análise, destaca-se a forma como se combinam, nas páginas do jornal, sentimentos pró-imperialistas com uma resistência subtil ao controlo hegemónico de discursos e imagens pela metrópole. O documento em análise representa uma tentativa única e curiosa de celebrar o império e, simultaneamente, defender os interesses e a identidade local de um grupo que se via atacado pelas novas políticas do Estado Novo.

Palavras-chave: Exposições coloniais; Angola; Portugal; imprensa; identidades imperiais

Over the past two decades, we have begun to gain a clearer understanding of the role played by colonial exhibitions in the early years of the Estado Novo (1933-1974).2 Inspired by the 1929 Ibero-American Exposition of Seville and the 1931 International Colonial Exposition of Paris (Vargaftig 2016: 63-98), Portuguese officials such as Armindo Monteiro (Minister of the Colonies, 1931-1935) and Henrique Galvão (director of the exhibitions) set out to produce their own colonial exhibitions, beginning with the 1934 Exposição Colonial Portuguesa (ECP) in Porto. Such exhibitions represented a meeting of worlds, meant to glorify the colonial project and show unity between colonial and metropolitan peoples. Indigenous peoples from Africa and Asia were put on display, colonial entrepreneurs exhibited goods, and a host of institutions from both colonies and metropole came armed with statistics and samples to impress visitors to their stands.

While new light has been shed on metropolitan perspectives on the exhibitions, voices from the colonies remain difficult to retrieve. This study examines a unique Angolan perspective on the 1934 ECP through the lens of a single publication: the Número extraordinário (NE) of the newspaper A província de Angola, published on the occasion of the exhibition.3 This special magazine edition presents a curious counterpoint to official views on the 1934 event. While it is a product of a colonial elite, it is nonetheless written from a decidedly local viewpoint. It is a testament to the supposed achievements of Portuguese colonialism in Angola, but one which emphasizes the settlers themselves and which often reads as a dialogue with metropolitan Portuguese visitors to the ECP, encouraging them to look beyond the surface of the images and information on display in Portugal. When analyzed against the backdrop of early-twentieth century colonial Angolan historywith particular attention to the tensions between Angolan white autonomist movements and the nascent Estado Novothe NE provides a window through which to glimpse Angolan colonists involvement in the 1930s exhibitions staged in both Portugal and Angola.

Angola não é um país pequeno

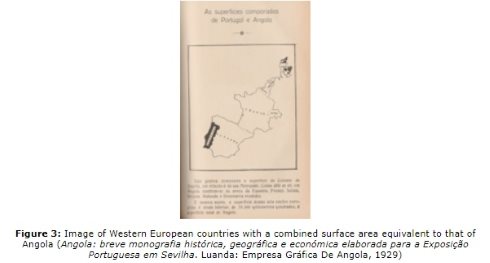

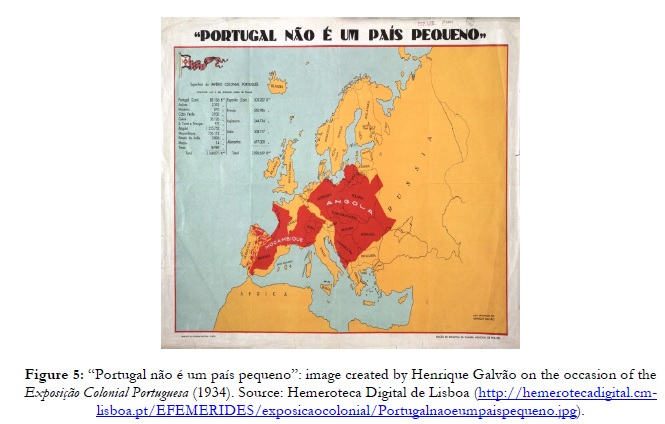

In the Angolan case, local involvement in colonial exhibitions began even before the ECP. For the 1929 Ibero-American Exposition of Seville, colonists from Angola created a booklet4 on the colony to accompany the exhibit, images from which can be seen above (Figures 1-3). In 1932, Luanda played host to theFeiras de Amostras de Produtos Portugueses. The Feiras (held first in Luanda and afterwards in Lourenço Marques) were organized by Henrique Galvão, who would then go on to direct the ECP, where he was responsible for the creation of one of the most infamous pieces of Estado Novo propaganda, Portugal não é um país pequeno (Portugal is not a small country) (Figure 5) (Serra 2016: 50).

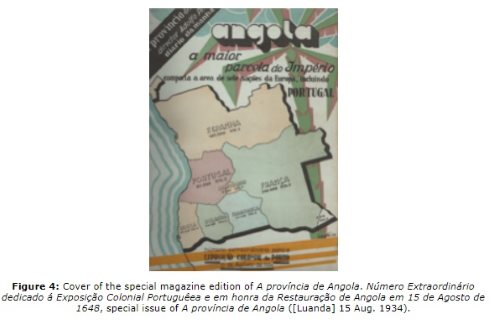

Galvãos map has come to epitomize the Estado Novos obsession with projecting an image of imperial might. 5 Few may be aware, however, that similar maps were made in 1929 (Figure 3) and 1934 (Figure 4), showcasing the territorial extent of Portugals largest colonial possession, Angola. The 1934 image, Angola, a maior parcela do Império (Angola, the largest portion of the Empire), is from the cover of the very magazine that is the focus of this article.

At first glance, the image seems to be a mere appropriation of the colonialist spirit manifested in Portugal não é um país pequeno. Indeed, A maior parcela likely dialogues with Galvãos map considering the latters appearance in a photograph in the magazine which shows a stand at the ECP belonging to the Empresa Gráfica de Angola (EGA): the parent company of A província de Angola, and also the publisher of the 1929 booklet from the Seville event. What is notable here is not simply the establishment of a direct lineage between the 1929 image and A maior parcela in 1934, with a likely intermediation of Galvãos map; the remarkable fact is that the images connection to the EGA means that they were published by a company whose founder and director, Adolfo Pina, was a fervent advocate of Angolan autonomy.

Given Pinas political views, we may never know to what extent the designers of A maior parcela intended the image to be an exaltation of empire or a sly retort to Galvãos message of imperial unity and grandeur. Perhaps it is both; in which case it can be held to be emblematic of the complex relationship between Angolan colonial elites and metropolitan officials during the early 1930s.

The 1934 ECP and the earlier Feiras de Amostras were seen by organizers as a means of strengthening economic ties between the colonies and the metropole. These events also came at a time of particular tension in the Angolan capital. Luanda had recently been the site of an uprising of military officers and local political elites against High-Commissioner Filomeno da Câmara (March 20April 10, 1930), which was followed by a series of measures aimed at dismantling power structures in the colony and reorienting the Angolan economy towards total dependence on Portugal (Pimenta 2005, 2012; Torres 1997).

Hostility to metropolitan control over colonial economic and political affairs could not possibly have evaporated by the time of the first colonial exhibitions in Angola and Portugal. However, the existence of publications such as the NE shows that Angolan colonial elites were nonetheless active participants in those events. Angolan companies and organizations, including the EGA, were present at the 1932 Feira de amostras de Luanda and at the 1934 ECP, and entities based in the colony would go on to put together Angolas first locally organized public exhibitions: the Exposição Provincial de Benguela (1935) and the Exposição-Feira de Angola (1938).

This analysis of the NE will look at the themes that most characterize the document and its insertion into the historical context under examination. First, however, we should look at the story of the man whose name appears on the cover of the magazine and understand how his life came to be intertwined with the history of the group Pimenta has termed the Euro-African nationalists of Angola (Pimenta 2008).

Adolfo Pina and Angolas White Settler Community

What little information can be gleaned about Adolfo Pina from the NE is found in the directors opening remarks in which he explains the purpose of the special edition, stating:

[ ] dedicado á 1ª Exposição Colonial Portuguesa [ ] editamos o presente Número extraordinário que, na sua modéstia, representa o máximo que os nossos recursos gráficos até agora conseguiram realizar e, incontestavelmente, o melhor que tem sido publicado na Colónia. A tanto nos abalançamos para, aos materiais magníficos que levantaram êsse monumento ao valor do Império, que é a Exposição Colonial Portuguêsa , juntarmos a nossa contribuição, dentro do que as possibilidades próprias permitiram .6 (Número extraordinário 1934: 5) 7 .

Pina likens the challenges of producing such a technically audacious publication to those faced by the colonists, whose struggles might be difficult for metropolitan Portuguese to understand. Although he praises the ECP, Pina also implies that the metropole should have greater sympathy for complaints voiced by colonists in the midst of hardship:

Esta a desculpa das suas impaciências, de suas reclamações e queixas por vezes enervantes [ ] para quem as ouve, fóra do meio trepidante em que se produzem. Que ela lhe seja levada em conta, pelo muito que moureja, sofre e concorre para a grandêsa da Pátria. Não se limitando a ser mero e anónimo orgão criador ou distribuidor de riquezas, vinca sua individualidade como colaborador apaixonado do progresso da maior parcela do Império . 8 (Número extraordinário 1934: 6-7, my emphasis).

Because of his oscillation between praise for the Empire and solidarity with Angolas settler community, it may be hard to see where Pinas sympathies lie. To read the subtext in Pinas words, one must understand more about who he was and what sort of complaints he was most likely referring to when discussing the plight of Angolan colonists.

Adolfo Pina was born in Porto in either 1889 or 1890, 9 and emigrated to Angola in 1910 (Torres 2012: 21). In 1913, he helped to organize the 1º Congresso Provincial de Benguela, where he first expressed his support for Angolan autonomy (Pimenta 2005: 111).

Pinas early activities in Angola are relatively obscure. It is helpful, however, to provide some historical context on early twentieth-century Angola. Pina arrived in the colony at a moment in which power relations between different groupswhites, mestiços andindígenas (blacks)were changing rapidly. 10 Until the late nineteenth century, the Portuguese presence in Angola had been largely restricted to a few coastal settlements such as Luanda and Benguela. The interior of the territory remained controlled by mostly Bantu African peoples and virtually untouched by white settlers, with the notable exception of Sá da Bandeira (Lubango), founded in 1884 (Castelo 2007: 54). Between 1900 and 1930, however, the white settler population increased from 9,000 to 30,000 (Pimenta 2012: 178). While this number remained minuscule in comparison with the black population, estimated at 3.3 million in 1930 (Pimenta 2005: 191), the growth of the settler population was significant enough that the newcomers began to assert themselves as a distinct social group and to form their own press and institutions, while, at the same time, the once highly active mestiço press was being pushed aside and suppressed (Pélissier and Wheeler 2009; Corrado 2010). These transformationswent hand-in-hand with a renewed post-Berlin Conference drive towards effective occupation and heightened divisions between racial groups under the influence of theories on the perils of racial mixing, such as those espoused by Norton de Matos, Governor-General of Angola (1912-1915) and High-Commissioner of Angola (1921-1924) (Castelo 2007: 66-69).

This period also saw discussions in metropolitan and colonial circles over the desired nature of the colonial project in Angola. One point of disagreement was whether or not imperial interests would be best served by increasing white settlement of the colonies. Even where officials agreed to promote settlement, they argued over what kind of colonization to encourage: that of skilled immigrants or that of poor laborers, such as the Madeirans who first settled Sá da Bandeira (Castelo 2007). Norton de Matos was an advocate of the latter type of colonization and his views and personal relationship with Angolas white communities earned him allies, such as Adolfo Pina, who defended the High-Commissioners economic policies in 1922 (Fonseca 2014: 154). On the other hand, the High-Commissioners stance against the use of forced labor also gained him enemies in the colony and his disastrous financial policies contributed to the strengthening of autonomist movements among settlers during the 1920s (Pimenta 2005: 98-100).

Adolfo Pinas activities in the 1920s were closely tied to the development of the autonomist movements. Pina created the Empresa Gráfica de Angola and its main newspaper,A província de Angola,in 1923. A província focused on issues of political autonomy in the colony, the problem of indigenous labor, colonization and infrastructure (Fonseca 2014: 148) and was one of the outlets through which colonists expressed their political demands during the 1920s (Pimenta 2012: 179).

In addition to his journalistic activities, Pina was a member of the Freemasons, like many of Angolas colonial elites.11 In the events surrounding the aforementioned 1930 uprising against High-Commissioner Filomeno da Câmara, Angolas Freemasonsnoted for their autonomist and republican sympathiescame under attack. The uprising came as a result of Câmaras temporary delegation of authority to his right-hand man, Morais Sarmento, who seized the opportunity to arrest and deport hundreds of opponents of the new fascist Portuguese regime (Torres 1997: 10). During the ensuing chaos, Salazar threatened to send a warship to Luanda to enforce Portuguese authority, eliciting calls for independence from some colonists, including Adolfo Pina, who stated:

Angola terá o destino de todas as colónias [ ] em todos os tempos se sente o formidável desejo e a invencível aspiração dos povos à independência. A hora de Angola ainda não chegou, mas ela chegará .12 (Qtd. in Torres 1997: 11)

The outcome of the March 1930 uprising saw Sarmento killed and Filomeno da Câmara recalled to Lisbon. Pina and his fellow autonomists, however, would have no better luck. Following a series of autonomist attacks against colonial authorities in the months from June to October of that year, the Portuguese government deported a number of the rebels and introduced measures to prevent further insubordination (Pimenta 2005: 111-112).

Among the laws enacted was the Lei das Transferências (May, 1931), which, in principle, was meant to ensure repayment of Angolas debts by placing control of its currency reserves in Lisbons hands (Ibid.: 113). The law was also a means of protecting Portuguese exports by limiting Angolas ability to import from other sources. In the wake of this decree, many of Angolas economic associations issued a letter of complaint to Lisbon, drafted by Adolfo Pina himself (Ibid.). Nonetheless, Lisbon continued to nationalize the Angolan economy and the autonomist movements lost their impetus with the dismantling of local power structures and elimination of the Masonic order (Ibid.: 114). Furthermore, the tightening of press censorship beginning in 1932 meant the gradual elimination of opposition voices from the colonial press, which only those publications willing to align themselves with the new regime were able to avoid (Fonseca 2014: 216).

A província de Angola was one such survivor, remaining in print until 1975 and existing to this day through its successor, the Jornal de Angola. Pina may have had to make compromises in order for his newspaper to survive, but he continued to express his opposition views in subtle ways up until his death in 1935.

One instance of Pinas insubordination occurred during the 1932 Feira de Amostras. Although the exhibition garnered considerable interest among colonial elites, not all colonists present could have been happy with the premise of the event. The Feira was a show of Lisbons strength following the recent centralizing measures; one in which Portuguese products were ironically showcased to prospective buyers from the colony, as if they had a choice in their consumption habits following the governments recent decrees. Such irony may not have been lost on Adolfo Pina, whose flagship newspaper created a stand at the event under the banner Por Angola, eliciting the following comment from fellow Luanda newspaper, Última Hora:

Em lugar de destaque, na Feira de Amostras, encontrava-se um enorme, disforme stand que poderíamos classificar de Stand - Enigma, visto que, de princípio, desconhecíamos a sua utilidade [ ] não obstante gigantescas letras dizerem Por Angola. Como mais tarde nêle vimos expostas colecções de jornais do nosso prezado colega A Província de Angola ficámos sabendo ao que êle se destinava e achávamos de mais efeito ter-se crismado êsse stand, mudando-lhe o nome para Pró Angola porque, afinal, para [sic] e pró têm, relativamente a mesma significação. 13 (Qtd. in Galvão 1933: 118)

When one realizes that Pró-Angola was the name of an autonomist group from the 1920s, the episode emerges as an inside joke among the local press, which, perhaps surprisingly, found its way into a section on positive reviews of the Feira in Henrique Galvãos official report on the event.

Upon Pinas death three years later, Elmano Cunha e Costalawyer, ethnographic photographer and undercover PVDE 14 agent in Moçâmedeswrote to Salazar that although the New State [had] not arrived to [sic] Angola, at least Angola was rid of Adolfo Pina, who was the most dangerous individual that Angola [had] ever seen, due to his ownership of much of Angolas free press and his links to the Freemasons (Faria 2013: 105).

Angolan researcher Paulo Faria believes that Cunha e Costas remarks on Pina were most likely exaggerated (Ibid.). Nevertheless, given Pinas political position, it is clear that the newspaper directors words in the NE are a veiled criticism of metropolitan ignorance of colonial realities. The words are couched in a language that glorifies imperial unity on the occasion of the ECP, but, by the end of Pinas introduction, the writers greater sympathy for his fellow settlers is clear.

The Angolan Settler in the Número Extraordinário

Pinas colleague and fellow NE contributor, Norberto Gonzaga, published a eulogy for the journalist in the special edition of the Voz do planalto (also owned by Pina) dedicated to the Exposição Provincial de Benguela (EPB) (1935). Gonzagas praise for his newspapers former director was not particularly controversial, as he limited himself to listing Pinas qualities as a journalist and businessman (Exposição Provincial 1935: 19). However, in exploring Gonzagas comments on the EPB, we see parallels with Adolfo Pinas earlier exaltation of Angolan settlers. Gonzaga writes:

O homem indomável [ ] virado à terra, seu berço e esperança, que canta a nostalgia dos pátrios lares, fica-se sem revoltas, abate-se ao infortúnio quando a desgraça baixa, e caminha de alma afeita de novo ao sacrifício [ ]

Que se diga bem alto nas colunas do nosso jornalfoi com gente desta que o Alto Comissário Norton de Matos contou, foi com gente desta têmpera, dêste quilate, que se fez o Huambo e foi com gente tam valente [ ] que hoje se leva a efeito a 1.ª EXPOSIÇÃO PROVINCIAL DE BENGUELA! [ ]

E nêste momento que recordamos a data da fundação da cidade não podemos deixar de saudar [ ] a rude gente do planalto [ ] A êsses bravos, a muitos dos seus que nestas terras tombaram mordendo o pó, impõe-se prestar-lhes a devida homenagem .15 (Ibid.: 11)

Detectible in Gonzagas words is a concern with defending the image of Angolas white settlers. As Pimenta has pointed out, even white Angolan colonists were the subject of discrimination by metropolitan Portuguese, and as more Portuguese immigrants entered the colony, divisions appeared between settlers born in Angola and those new arrivals, who were seen as having certain privileges (Pimenta 2012: 181-183). This prejudice was also visible in discussions surrounding colonization policies, which were often influenced by deep-rooted theories on the tropical degeneration and cafrealization (adoption of indigenous habits by Europeans) that were thought to affect whites in Africa. These discussions were also marked by criticism of the low social status of most older generations of Portuguese immigrants to Angola (Castelo 2007: 43-124).

Thus, when Gonzaga writes of the rude gente do Planalto he may also be turning the tables on preconceived notions of the degeneracy of the colonists by glorifying the first generations. He goes on to write of Angolan colonists as agents of progress, insinuating that this is something metropolitan Portuguese knew little about (Exposição Provincial 1935: 13). Gonzaga also expresses concern over new waves of immigration:

Não perderemos de vista a colonização estrangeira. Mas [ ] antes da vinda de novos colonos [ ] urge pensar na vida daquêles que já por aqui mourejam.

Quais são os alicerces da colonização nestas paragens? A terra e a família. [ ] Aos colonos, pois, já estabelecidos, a primazia. Os outros virão depois metòdicamente e consoante o apetrechamento.

Portugal não é um país pequeno . Se deseja viver e prosperar, não o pode fazer alheando-se da vida das províncias ultramarinas [ ]16 (Ibid.: 47, my emphasis)

Gonzagas glorification of the Angolas white settler community is also visible in his story A vida de um raio de sol, included in the NE. The ray of sunshine in question is the unborn child of Natacha Maria, the Portuguese wife of Fritz, a Boer settler who lived near Sá da Bandeira. Fritz is impaled by an elephants tusks, but his desolate widow discovers that as suas entranhas, agora despertas, guardavam a herança do morto 17 (Número extraordinário 1934: 83). Natacha kisses her husbands corpse, happy in the realization that her future child represents the continuation of her community. Here it is helpful to recall that Sá da Bandeira was one of the first white settlements in the Angolan interior, having been colonized simultaneously in the 1880s by Portuguese settlers from the island of Madeira and by South African Boer trekkers.18 Oddly enough, a young Henrique Galvão spent most of his time in the region in Angola, getting to know both communities; Madeirans and Boers. He described them as white tribes, and was particularly depreciative of the Madeirans, whom he believed had suffered a process of africanization (Pimenta 2005: 47).

Aware of the negative image that individuals such as Galvão held of Angolas older settler communities, contributors to the NE sought to turn settlements such as Sá da Bandeira into emblems of the successful colonization of Angola. Reference to the town is also made in Carta de Longe e de Perto, by José Licínio Rendeiro. The writer, addressing metropolitan readers, complains that Angola é uma terra caluniada como tantos outros florões do nosso querido Império.19 He emphasizes the mild climate of the plateaus and lists the modern achievements of the colony: trains, cinemas, and newspapers. Moreover, Rendeiro stresses the Portugueseness and whiteness of the colony. He writes:

Nunca lhes disseram, meus amigos, que uma das maiores riquesas de que se pode orgulhar Portugal, são as cinco mil crianças da nossa côr que, na região de Sá da Bandeira, pedem a Deus pela Pátria-Mãe? 20 (Número extraordinário 1934: 55)

Rendeiro closes with the following:

Angola é uma terra incompreendida por nós, mas demasiadamente conhecida pelos estrangeiros. Nela habitam 60.000 brancos da Metrópole que, pela lei e pela grei, honram o nome da Pátria longínqua. Só lastimamos que vocês não nos conheçam melhor e não abandonem aquele cepticismo e aquela indiferença que manifestam quando se fala de Angola.

Terra de condenados? Terra de pretos? Terra de féras?

Não meus amigos! Terra de gente honrada, terra de brancos, terra de Portugal. 21 (Ibid.)

Writing from Afar

Carta de Longe e de Perto expresses sentiments shared by Galvão and Monteiro who, in putting together the ECP, hoped to put an end to popular misconceptions regarding the colonies. The notion of writing from afar, on the other hand, is one that is present in many articles in the NE and underscores the personal nature of colonists concerns over being misunderstood by those back in Portugal.

This theme manifests itself in multiple ways. In Carta ás mulheres de Portugal, D. Maria Amélia Dias dAlmeida Teixeira writes of the rich social life and quality facilities to be found in Luanda and stresses how pleasantly surprised she was by the quality of life to be had in the colony. Teixeiras letter is a call to the women of Portugal to follow her example, but, like Rendeiros Carta de Longe, it is also meant to bridge the knowledge gap between mother country and colony.

The appeals from afar in the NE are also often related to a perceived lack of economic support for the colony. Francisco Borja do Nascimento writes that the ECP is an opportunity to reawaken the spirit of discovery among modern Portuguese and open their eyes to the possibilities offered by the colonies. In a seeming reference to the recent strangling of Angolas economy by harmful policies, Nascimento states:

Da estrutura do sistema de administração do nosso Império Colonial não pode deixar de resultar sempre [ ] um grande desequilíbrio económico entre todas as partes do todo a favor da Metrópole, como aliás é justo e natural [ ] Mas para que então a vida das colónias se não estiole, convém, é imprescindível, que se não esqueça nem se deixe de atender a necessidade de compensar [ ] aquele mesmíssimo desequilíbrio, não por via de empréstimos ruinosos e vexatórios, mas com a construção de portos e caminhos de ferro [ ]

Povo Português! Fadado desde remotos séculos para povo colonizador e civilizador, acarinhai as vossas colónias [ ] recuperai com sofreguidão a pura essência da vossa tradicional MENTALIDADE COLONIAL! 22 (Número extraordinário 1934: 108)

Nascimento is not the only one to request railroads. Carlos Alves (perhaps the only non-white contributor to the NE) 23 describes the agricultural potential of the Congo region (current Uíge province) of northwestern Angola and dispels myths about the regions poor climate and diseases. After listing the areas numerous positive qualities, however, Alves finishes with an appeal:

Sua Ex.ª o Ministro das Colónias, Dr. Armindo Monteiro, quando passou no Uíge pela sua visita à Colónia em 1932, teve ocasião de vêr [ ] alguns cafésais em frutificação.

[ ] Quando Sua Ex.ª vir em exposição o café do Uíge, que se lembre dos seus produtores amarrados implacavelmente às consequências fatais da monocultura [ ] Que se lembre do território enorme formado pelo Zaire-Congo, que não tem uma via de penetração que lhe garanta uma troca eficiente com o exterior dos géneros variados da sua produção [ ] Que se lembre, enfim, de dar o impulso que há muito o Congo-Zaire espera para a construção do seu caminho de ferro [ ] que guarda a chave que há de abrir as portas da riqueza, da prosperidade e do bem estar. 24 (Ibid. 1934: 99)

What is fascinating about Alvess article is the dialogue he opens with Armindo Monteiro. Clearly, Alves knew of Monteiros 1932 visit to Angola, which coincided with the Feira de amostras, and he was also aware of his regions representation in the Angolan section of the ECP, using it as an opportunity to press Monteiro on the delivery of real progress to accompany the flash and rhetoric of the exhibition. Alvess knowledge of the exhibitions is also made clear by the fact that he contributed to writing the Opúsculo de Propaganda entitled Uíge, Songo e Bembe: A Circunscrição Civil do Bembe, na Primeira Exposição Colonial Portuguesa, 1934 , published under the sponsorship of the Angolan Governments delegation to the ECP.

As a final example of the dialogue between the NE contributors and visitors to the ECP, special attention should be given to Ralph Delgados article A Riqueza Indígena de Angola. The article contains what initially reads as a somewhat progressivealbeit paternalisticcriticism of Portuguese exoticizing and objectification of Angolas indígenas:

Para os portugueses que andam distanciados , por falta de conhecimentos, da nossa obra colonial, os negros boçais do nosso património ultramarino são taxados de elementos primitivos exóticos [ ] ; para os escritores, para os poetas, que se não dediquem, também, à causa colonial, os indígenas são fontes de caprichos de retórica, de barbarismos fantasistas, aproveitados, na generalidade, por uma nudez lamentável, adjectivada de artística,pedaços humanos dignos de registo, não pelo que façam ou possam vir a fazer, mas pelo que valem como antiqualha rara, preciosa, de museu [ ]25 (Número extraordinário 1934: 95, my emphasis)

Although Delgado was probably aware of the fact that visitors to the ECP were being exposed to the lamentable nudity of Africans who were part of the exhibitions living museums26 hence the articles inclusion in this special issuethe article seems out of place in a magazine that itself contains pictures of semi-nude African women, such as the one titled Venus Negras de Angola. 27 In any event, the writer does not dwell on the issue of the objectification of black (mainly female) bodies,28 since his main point regards what he considers to be the true indigenous wealth of Angola, of which only the colonists are aware:

Só para os comerciantes que têm relações com o ultramar, para os colonialistas, para os estudiosos, eles [os indígenas] são considerados elementos superiores de actividade, colaboradores incansáveis e dirigidos da nossa obra colonizadora, personalidades conscientes, acessíveis ao progresso, cujas portas lhes rasgâmos, com paciência e com interesse inegualáveis [ ]29 (Ibid.)

The rest of Delgados article amounts to a series of statistics on the productivity of Angolas indigenous workforce. It is a call for investment in healthcare facilities and other infrastructures that will transform the indígenas into even more productive members of colonial society. As such, the articles message is not so different from that of the advocates of indigenous labor in metropolitan policymaking circles. The key difference hereand the main feature that this article shares with others in the NEis that it stresses, once again, that it is the colonists who know what the colony needs.

Whether they emphasize the past exploits of the colonists, the fruits of modern living, or the economic imperatives of the future, the writers of the NE make it clear that their proximity to Angolan affairs gives them a unique right to speak from and for the colony. In retrospect, it is abundantly clear that such elite voices could hardly claim to speak for any but a tiny minority of the colonys population. Yet the emphasis on local perspectives is clear and omnipresent throughout the publication and stands in marked contrast to the voices heard in metropolitan publications on the ECP.

Conclusions

More remains to be said on Angolan involvement in the colonial exhibitions of the 1930s. Nevertheless, the examination of this one magazine reveals a side of the colonial exhibitions that is not often visible, bringing to light unique agencies and viewsin this case, those of the colonists themselveswhich contest one of the exhibitions main intended purposes: to demonstrate unity and singularity of thought among imperial citizens and subjects.

One might think that colonists would be happy to be represented in the metropole as agents of civilization, thus aligning themselves with the organizers ideological aims. Adolfo Pina and the contributors to the NE show us that although pride in the Empire and its civilizing mission was certainly a pervasive characteristic of those colonists writings on the 1ª Exposição Colonial Portuguesa, they also were greatly concerned about who was speaking for them in the metropole and how they were being perceived.

On the eve of the first colonial exhibitions in Angola and Portugal, the tensions between the metropole and certain Angolan colonial elites came to a head following the repression of the autonomist movements, elimination of the free press, dismantling of local power structures, and enactment of harsh economic policies. Despite whatever economic benefits and cultural pride colonists might have derived from the exhibitions, many of themespecially those involved in what once constituted the colonys opposition presswould not have forgotten their disputes with Lisbon.

Thus, even in times of censorship, the contributors to the NE found subtle ways to promote their own agendas between the lines of imperialist rhetoric. They may have genuinely believed in the imperialist ideals being exposed, but they wished to see them translated into real respect and material benefits for themselves, for their fellow colonists, and, in some limited respects, for Angola as a whole. Thinking back to the colorful cover image A maior parcela do império, and taking into account Adolfo Pinas words that the Número extraordinário was the greatest achievement thus far of Angolas printing industry, one can see that the magazine was an outlet for expressing pride in more than just the colonial project on display at the ECP. It was about articulating a particular type of local identity and making the colonists voice heard, both in Angola and in the metropole.

REFERENCES

Primary Sources:

Angola: breve monografia histórica, geográfica e económica elaborada para a Exposição Portuguesa em Sevilha (1929). Luanda: Empresa Gráfica De Angola. [ Links ]

Boletim Geral Das Colónias. Ano VIII, nº 83. Lisboa: Agência Geral das Colónias, Maio de 1932. [ Links ]

Boletim Geral Das Colónias. Ano VIII, nº 84. Lisboa: Agência Geral das Colónias, Junho de 1932. [ Links ]

Boletim Geral Das Colónias. Ano VIII, nº 85. Lisboa: Agência Geral das Colónias, Julho de 1932. [ Links ]

Boletim Geral Das Colónias. Ano VIII, nº 86. Lisboa: Agência Geral das Colónias, Agosto/Setembro de 1932. [ Links ]

Boletim Geral Das Colónias. Ano VIII, nº 85. Lisboa: Agência Geral das Colónias, Julho de 1932. [ Links ]

Boletim Geral Das Colónias. Ano XIV, nº 153. Lisboa: Agência Geral das Colónias, Março de 1938. [ Links ]

Coimbra, V. and Leitão, M. (1934) O Império português na 1ª Exposição colonial portuguesa. Album-catálago oficial: documentário histórico, agrícola, industrial e comercial, paisagens, monumentos e costumes . Porto: Agência Geral das Colónias. [ Links ]

Exposição Provincial de Benguela e Feira de Amostras no Huambo . Nova Lisboa: Voz do Planalto, 1935. [ Links ]

Feira de Amostras de Produtos Portugueses em Angola e Moçambique . Catálogo. Lisbon: Ministério das Colónias, 1932. [ Links ]

Galvão, H. (1933) As feiras de amostras coloniais 1932, relatório e contas . Lisbon: Ministério das Colónias. [ Links ]

Martins, J. R., Afonso, J. and Alves, C. (1934) Uíge, Songo e Bembe: A Circunscrição Civil do Bembe na Primeira Exposição Colonial Portuguesa, 1934: Opúsculo de Propaganda . Luanda: Imprensa Nacional. [ Links ]

Número Extraordinário dedicado á Exposição Colonial Portuguesa e em honra da Restauração de Angola em 15 de Agosto de 1648 , special issue of A província de Angola [Luanda] 15 Aug. 1934. [ Links ]

Secondary Sources:

Acciaiuoli, M. (1998) Exposições do Estado Novo, 1934-1940. Lisbon: Novo Horizonte. [ Links ]

Cairo, H. (2006) [2017] Portugal is not a small country: Maps and Propaganda in the Salazar Regime. Geopolitics 11 (3) 367–95. [ Links ]

Castelo, C. (2007) Passagens para África: O Povoamento de Angola e Moçambique com Naturais da Metrópole (1920-1974). Porto: Afrontamento. [ Links ]

Corrado, J. (2010) [2017] The Fall of a Creole Elite? Angola at the Turn of the Twentieth Century: The Decline of the Euro-African Urban Community. Luso-Brazilian Review 47 (2) 121-49. [ Links ]

Faria, P. C. J. (2013) The Post-war Angola: Public Sphere, Political Regime and Democracy. Newcastle upon Tyne, UK: Cambridge Scholars. [ Links ]

Fonseca, I. (2014) [2017] A Imprensa e o Império na África Portuguesa, 1842-1974 . Diss. Universidade De Lisboa.

Hohlfeldt, A. and Carvalho, C. (2012) A imprensa angolana no âmbito da história da imprensa colonial de expressão portuguesa. Intercom – Revista Brasileira de Ciências da Comunicação 35 (2) 85-100. [ Links ]

Lopo, J. C. (1962) Para a História da Imprensa de Angola. Luanda: Centro de Informação e Turismo de Angola. [ Links ]

Matos, P. F. (2006) As cores do império: representações raciais no império colonial português . Lisbon: Instituto de Ciências Sociais. [ Links ]

Melo, D. (2016) [2017]A censura salazarista e as colónias: um exemplo de abrangência. Revista de História da Sociedade e da Cultura (16) 475-496. [ Links ]

Pélissier, R. and Wheeler, D. (2009) História de Angola. Lisbon: Tinta da China. [ Links ]

Pimenta, F. T. (2012) Angolas Euro-African Nationalism: The United Angolan Front. In E. Morier-Genoud, (org.) Sure Road? Nationalisms in Angola, Guinea-Bissau and Mozambique. Leiden: Brill. [ Links ]

Pimenta, F.T. (2008) Nacionalismo Euro-Africano em Angola: uma Nova Lusitânia?. In Comunidades Imaginadas: Nação e Nacionalismos em África . Coimbra: University Press. [ Links ]

Pimenta, F.T. (2005) Brancos de Angola: Autonomismo e Nacionalismo (1900-1961). Coimbra: Minerva Coimbra. [ Links ]

Pinto, A. O. (2013) Representações literárias coloniais de Angola, dos angolanos e das suas culturas, 1924-1939 . Lisbon: Fundação Calouste Gulbenkian/FCT. [ Links ]

Pomar, A. (2013) [2017] Luanda: Exhibition-Fair Angola 1938. Buala.

Rosas, F. (2012). Salazar e o Poder: A Arte de Saber Durar. Lisbon: Tinta da China. [ Links ]

Serra, F. (2016) [2017] Visões do Império: a 1ª Exposição Colonial Portuguesa de 1934 e alguns dos seus álbuns. In Revista Brasileira de História da Mídia (RBHM) 5 (1). [ Links ]

Torres, A. (1997) [2017] Angola: conflitos políticos e sistema social (1928-1930). Estudos afro-asiáticos 32: 163-183. [ Links ]

Torres, S. (2012) Guerra colonial na revista Notícia : A cobertura jornalística do conflito ultramarino português em Angola . Thesis. Universidade Nova de Lisboa. [ Links ]

Vargaftig, N. (2016) Des Empires en Carton: les expositions coloniales au Portugal et en Italie (1918-1940). Madrid: Casa de Velázquez. [ Links ]

Vicente, F. L. (2013) [2017] Rosita e o império como objecto de desejo. Buala. [ Links ]

Zilhão, P. (2006) [2017] Henrique Galvão: prática política e literatura colonial (1926-36) . Thesis. Universidade de São Paulo.

NOTES

2 See, for example: Acciaiuoli 1998; Matos 2006;Vargaftig 2016.

3 Número Extraordinário dedicado á Exposição Colonial Portuguesa e em honra da Restauração de Angola em 15 de Agosto de 1648 , special issue of A província de Angola. Luanda, 15 Aug. 1934.

4 Angola: breve monografia histórica, geográfica e económica elaborada para a Exposição Portuguesa em Sevilha . Luanda: Empresa Gráfica De Angola, 1929.

5 For further information, see Cairo 2006.

6 [ ] dedicated to the 1st Portuguese Colonial Exhibition [ ] we have published this Special Edition, which, in its modesty, represents the greatest achievement that our printing resources have thus far been able to produce, and, undeniably, the best publication yet produced in the Colony. To the extent that present conditions permit, we have put forward our best effort to add our contribution to the magnificent materials that have gone into the making of that monument to the value of the Empire that is the Portuguese Colonial Exhibition.

7 The original spelling in all quotations has been left unaltered.

8 This excuse for their [the colonists] impatience, for their complaints, which are sometimes irritating [ ] to those that hear them outside of the atmosphere of trepidation from which they spring: may it be taken into account, given how much they toil, suffer and fight for the greatness of the Fatherland, not wishing themselves to be limited to mere anonymous generators or distributors of wealth, and staking their claim to individuality as passionate contributors to progress in this greatest portion of the Empire .

9 Torres (2012) dates his birth to 1890, but the Biblioteca Municipal do Porto (bmp.cm-porto.pt/) has a date of 1889 on titles listed with Adolfo Pina as the author.

10 See: Pélissier and Wheeler 2009; Castelo 2007.

11 One should recall, of course, that the Freemasons were major political targets of Salazars regime during his rise to power and throughout the formative years of the Estado Novo. See, for instance, Rosas 2012.

12 Angola will have the same destiny as all colonies [ ] all times have borne witness to peoples great desire for, and invincible aspiration towards, independence. Angolas time has not yet come, but it shall arrive.

13 Centrally placed in the Feira de Amostras, there was a huge, oddly shaped stand, which we might classify as an Enigma Stand, given that, at first, it was unclear what purpose it served [ ] despite the fact that giant letters read For Angola. As we later noticed the stands collections of newspapers from our dear colleagues at A Província de Angola, we understood what it was for, and felt it might have been more effective to christen it Pro-Angola, since, after all, for and pro have essentially the same meaning.

14 Polícia de Vigilância e de Defesa do Estado the Portuguese security agency that preceded the infamous PIDE (Polícia Internacional e de Defesa do Estado ).

15 These indomitable men [ ] turned towards the land, their birthplace and their hope, who sing nostalgically of their native land: they do not revolt. They are momentarily knocked down when misfortune befalls them, only to march forth again with their souls hardened by sacrifice. Let it be said loud and clear in the columns of our newspaper: it was people like these that High-Commissioner Norton de Matos counted on, it was with men of this Caliber that Huambo was founded and it was with such valiant people [ ] that we have been able to bring to fruition the 1st Provincial Exhibition of Benguela! [ ] And in this moment when we commemorate the date of the founding of this city, we cannot forget to salute [ ] the rough-mannered men of the plateau [ ] We must pay due homage to these bold men, to the many of their like who have bitten the dust in this land.

16 We will not lose sight of foreign immigration. But [ ] before new colonists arrive [ ] we must think of the lives of those who already toil here. What are the bedrock of colonization in this part of the world? Family and the land [ ] Let priority be given, then, to those colonists who are already established. Others will come in a measured way and according to the resources available. Portugal is not a small country . If it wishes to live and prosper, it cannot do so by turning its back on the overseas provinces [ ]

17 Her womb, newly awakened, guarded the dead mans legacy.

18 In fact, the Madeirans had been sent to the region precisely to block colonization by the Boers, whom the Portuguese government mistrusted as unpredictable foreign agents whose culture was incompatible with Portuguese values (Pélissier and Wheeler 119-120). Considering that, when these efforts failed, some hoped the Boer population would be assimilated into the Portuguese community, perhaps Natachas pregnancy, followed by Fritzs death, represents a successful pact between the two communities, with the ultimate longevity of the Portuguese element.

19 Angola is a much maligned land, just like so many other flowers of our cherished Empire.

20 Have you not heard, my friends, that one of the greatest treasures of which Portugal can boast are the five thousand children of our color who, in the region of Sá da Bandeira, pray to God on behalf of the Motherland?

21 Angola is a land that we misunderstand, but which is all too well known to foreigners. There reside 60,000 whites from the Metropole who, for God and country, honor the name of the far-off Fatherland. We only regret that you do not know us better and that you do not abandon that skepticism and that indifference you display when talking about Angola. A land of exiles? A land of black people? A land of wild beasts? No my friends! A land of honorable people, a land of white people, a land that belongs to Portugal.

22 The administrative structure of our Colonial Empire must always lead to [ ] a great economic imbalance between all parts in favor of the Metropole, as is, of course, fair and natural [ ] But so that life in the colonies does not stagnate, it is essential that we not forget to compensate for [ ] that same imbalance, not via ruinous and humiliating loans, but through the construction of ports and railways [ ] People of Portugal! Destined throughout the centuries to be a colonizing and civilizing people, cherish your colonies [ ] you must eagerly recover the pure essence of your age-old COLONIAL MENTALITY!

23 Judging from sparse photographic and biographical information on the contributors. Photographs of Alves show him to be most likely mestiço, but no direct confirmation of this has been found. Alves published a number of works (see listings on http://memoria-africa.ua.pt/ ) and was later involved in politics as Mayor of Carmona (Uige) and deputy for Angola in the National Assembly (see http://app.parlamento.pt/PublicacoesOnLine/DeputadosAN_1935-1974/html/pdf/a/alves_carlos.pdf)

24 His Excellency, the Minister of the Colonies, Dr. Armindo Monteiro, when he passed through Uige during his visit to the Colony in 1932, had the opportunity to see some fruiting coffee bushes. [ ] When His Excellency sees Uiges coffee on display at the exhibition, may he remember the coffee growers who are cruelly tied to the fatal consequences of monoculture. [ ] May he remember the enormous territory of the Zaire-Congo region, which has no commercial route to ensure the efficient export of its various products [ ] May he remember to provide that impetus that the Congo-Zaire has long awaited to begin construction of its railway [ ] which holds the key to opening the doors to wealth, prosperity and well-being.

25 Among those Portuguese who, due to their lack of knowledge, are far removed from our colonial issues, the uncultured blacks of our overseas territories are considered to be exotic and primitive beings [ ]; for those writers and poets who also are not dedicated to the colonial cause, the indígenas are a source of fanciful rhetoric and fantastic barbarisms, and are often taken advantage of for their lamentable nudity, labeled as artistic – human bodies worthy of record, not for what they do or what they may come to do, but rather for what they are worth as rare, precious antique pieces for museums [ ]

26 For more on this topic, see: Blanchard, Pascal (2008). Human Zoos: Science and Spectacle in the Age of Colonial Empires. Liverpool: Liverpool UP.

27 Very probably a reference to Sara Baartman (1790 – 1815), a Khoikhoi woman known as the Hottentot Venus who was put on display as a freak-show attraction for her allegedly abnormally large buttocks and images of whom fed into discourses on scientific racism over the course of the 19th and 20th centuries. See, for example: Lindfors, Bernth (2014). Early African Entertainments Abroad: From the Hottentot Venus to Africa's First Olympians. Madison: U of Wisconsin.

28 The circulation and consumption of images of nude African women by a (male) European public was a widespread and disturbing feature of visual culture in the Portuguese Empire and others. For more on this topic see, for instance, Vicente 2013.

29 Only for those traders who do business in the overseas territories, for the colonialists, for those who study [colonial matters], they [the indígenas] are considered superiorly active, tireless directed collaborators in our colonizing mission: conscious personalities who are capable of progress, the doors to which we open wide for them, with unparalleled patience and interest [ ]

Copyright 2018, ISSN 1645-6432

e-JPH, Vol. 16, number 1, June 2018