Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Acessos

Acessos

Links relacionados

-

Similares em

SciELO

Similares em

SciELO

Compartilhar

e-Journal of Portuguese History

versão On-line ISSN 1645-6432

e-JPH vol.16 no.1 Porto 2018

https://doi.org/10.7301/Z0VH5MBT

ARTICLES

A Forgotten Century of Brazilwood: The Brazilwood Trade from the Mid-Sixteenth to Mid-Seventeenth Century

Cameron J. G. Dodge1

1 University of Virginia, USA. E-Mail: cjd9yp@virginia.edu

ABSTRACT

The brazilwood trade was the first major economic activity of colonial Brazil, but little research has examined the trade after the middle of the sixteenth century. This study describes the emergence of the trade and the subsequent changes that allowed it to overcome the commonly-cited reasons for its presumed decline within a century of its beginnings, namely coastal deforestation and a shrinking supply of indigenous labor. Examining the brazilwood trade on its own apart from comparisons with sugar reveals an Atlantic commercial activity that thrived into the middle of the seventeenth century.

Keywords: Brazilwood, economic history of Brazil, colonial Brazil, royal monopoly, Atlantic history

RESUMO

O comércio do pau-brasil foi a primeira atividade econômica do Brasil colonial mas pouca pesquisa tinha examinado o comércio depois o meio do século XVI. Este estudo descreve o surgimento do comércio e as mudanças subsequentes que o permitiu superar as razões citadas para seu presumido declínio em menos de um século do seu início, a saber desmatamento litoral e diminuição da oferta de mão-de-obra indígena. Examinar o comércio do pau-brasil sozinho sem comparações a açúcar revela um comércio atlântico que prosperou até o meio do século XVII.

Palavras-chave: Pau-brasil, história econômica do brasil, Brasil colonial, monopólio real, História Atlântica

In mid-July 1662, two Dutch ships arrived near the now-forgotten harbor of João Lostão in Rio Grande do Norte on the northern coast of Brazil. The men from the first ship disembarked and began loading the crimson logs of a tree called brazilwood onto their vessel. Meanwhile, the second ship sailed further up the coast and dispatched a separate contingent into the forest to hunt for more of the wood and bring it to the shore. The Dutchmen of the first ship had already loaded a substantial cargo of brazilwood onto their vessel when a large Portuguese caravel approached them. The Portuguese captain, Francisco de Morais, hailed the Dutch crew and asked what their business was in this part of Brazil. They responded that they had just finished loading a cargo of brazilwood and were waiting for more to come from their countrymen trekking in the interior. Hearing this information, Morais continued up the coast and, finding the second ship, anchored his own caravel, gathered his men, and headed into Brazil's Atlantic Forest. The Portuguese unit ventured a short ways inland and encountered the Dutchmen chopping down stands of brazilwood and gathering the logs for transport back to the coast. Morais and his men fell upon the Dutch, killing three and scattering the rest. With the opposing crew dispersed, the Portuguese burned all the brazilwood they found there to prevent the foreigners from coming back and harvesting any more (AHU CU 018, cx. 1, d. 6).

Brazilwood (Portuguese pau-brasil), the commodity the Dutch sailors were attempting to trade, is the common name given to the species Paubrasilia echinata and is native only to Brazil.2 Unlike many other exotic hardwoods, brazilwood's value lay not in its uses as a variety of timber but as a source of dye. When soaked in water, the flesh of the brazilwood tree creates a crimson dye useful in coloring textiles. Its colorfastness surprised sixteenth-century French traveler Jean de Léry when he visited Brazil:

One day one of our company decided to bleach our shirts, and, without suspecting anything, put brazilwood ash in with the lye; instead of whitening them, he made them so red that although they were washed and soaped afterward, there was no means of getting rid of that tincture, so that we had to wear them that way (Léry, 1992: 101).

Textile producers in the industry's centers of Europespecifically England, Italy, northern France, and the Low Countriescame to value brazilwood dye for the strength and distinctive hue noted by Léry. At the time of Pedro Cabral's landing in 1500 on the shores of what Europeans would come to know as Brazil, brazilwood grew relatively abundantly in stands up and down the Atlantic coast from Cabo de São Roque in the north through to Guanabara Bay in the south. That said, three main regions had the densest stands of P. echinata and became the foci of the brazilwood trade through the sixteenth century and into the seventeenth century: the area around Cabo Frio, southern Bahia close to Porto Seguro, and Pernambuco. The last of these became particularly renowned for the abundance and quality of its wood (Sousa, 1978: 45-49, 53-55; Dean, 1995: 45).

The trade in brazilwood was the first major economic activity of colonial Brazil. Historians of Brazil usually date the trade as lasting from Cabral's landing in Brazil in 1500 to around 1550. According to this traditional narrative,3 a number of factors contributed to the decline of the trade by the middle of the sixteenth century. Deforestation from the early decades of brazilwood harvesting and land clearance for sugar planting led to a decline in the supply of the dyewood. Furthermore, hostilities between Portuguese settlers and indigenous Brazilians resulted in a decreasingly reliable labor source (Disney, 2009: 216-218, 233-236). There is also a sense that, with the rapid growth in highly-profitable sugar cultivation in the middle of the century, there was something akin to a crowding out of further investment in brazilwood commerce. The brazilwood trade was thus a primitive, extractive commercial activity that petered out after half a century (Buescu & Tapajós, 1967: 24, 32; Buescu, 44). If brazilwood really had ceased to be an important commodity by the middle of the sixteenth century, however, why did our Portuguese and Dutchmen at João Lostão come to blows over a load of this dyewood in 1662, more than a century after the trade had allegedly tailed off? Why were the Dutch willing to come on a clandestine mission from their own country on the North Sea to harvest the wood? Why was a Portuguese patrol plying the coast with the specific aim of disrupting interloping traders? And why were these Portuguese so bent on keeping control of this wood that they would burn what remained?

The following pages trace the brazilwood trade in Brazil and the Atlantic through the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, emphasizing its continued strength through the middle of the latter when this imperial altercation took place. The trade emerged from the early voyages of Portuguese colonization and quickly became the colony's primary economic activity, attracting the attention of rival French merchants. The trade operated first under a royal monopoly and then under a series of royal licenses. Brazilwood harvesting took place close to the coast with the help of indigenous labor. While the trends of deforestation and an increasing lack of willing indigenous labor are apparent starting in the middle of the sixteenth century, the brazilwood trade continued into the seventeenth century under a revived monopoly system. Portuguese colonists harvested brazilwood with the help of slaves by moving up Brazil's rivers and exploiting stands of wood further inland, thus overcoming the aforementioned trends that seemed to spell the trade's end. Far from being a primitive commercial activity, this new method of brazilwood harvesting necessitated capital investment and a high degree of coordination between the trade's various participants. Comparing this later period of the trade with the earlier, we see that, while the value of brazilwood exports did decline, they did so only after 1600, and even in the seventeenth century the trade was still a significant economic activity in the colonial Brazilian economy as evidenced by a number of measures. The brazilwood trade's longevity makes it part of narratives such as rivalries over Atlantic commerce, the trans-Atlantic slave trade, and the shift in global commerce from the Indian Ocean to the Atlantic.

The Brazilwood Trade in the Sixteenth Century

The brazilwood trade emerged from the first Portuguese voyages to Brazil in the opening years of the sixteenth century. Pedro Cabral's fleet, the argosy credited with the European discovery of Brazil, was the first to export brazilwood back to Portugal. The fleet landed near Porto Seguro in the future state of Bahia in April of 1500. After a week's stay, the bulk of the fleet continued around the Cape of Good Hope to India, the fleet's original destination, but Cabral sent captain Gaspar de Lemos and the fleet's supply ship back to Lisbon to convey reports of the newly-discovered territory to Portuguese monarch Dom Manuel. Lemos' ship bore a cargo of brazilwood, harvested by native Brazilians during the Europeans' brief stay (Guedes, 1975a: 165-172; Sousa, 1978: 56-57). With the news of Brazil's discovery and the arrival of the first shipment of brazilwood in Lisbon, D. Manuel quickly dispatched a follow-up expedition to further explore the new lands upon which Cabral had stumbled. This expedition reported infinite quantities of brazilwood in the territory and almost certainly brought another shipment of the dyewood back to Lisbon (Guedes, 1975b: 226-239; Vespucci, 2005: 282).

These two early voyages revealed the quantity of brazilwood in Brazil and the colony's potential economic value to the Portuguese crown. After the return of the second voyage in 1502, the crown began to contract out the rights to control trade with the territory to private merchants who would finance brazilwood commerce in its early years. In the few decades of the trade, royal permission took the form of monopoly contracts awarded to an individual or consortium whereby that party was the only one allowed to import brazilwood from Brazil. The Portuguese crown had long doled out similar monopoly contracts for the rights to trade with territories in west Africa during the fifteenth century as Portuguese explorers gradually made their way further down Africa's Atlantic coast (Sousa, 1978: 58). The brazilwood contracts of the sixteenth century were simply an extension into the New World of time-honored Portuguese imperial commercial practices.

D. Manuel awarded the first contract to a consortium of Lisbon merchants headed by Fernão de Loronha. For the first three years of the contract, the crown charged Loronha and his partners with a number of stipulations: sending six ships annually to Brazil to trade brazilwood, exploring 300 additional leagues of the land's coast during each expedition, and establishing and maintaining a fort. All this, including building the fort and maintaining its garrison, would be done at the merchants' own expense. In addition, the merchants owed the crown each year a portion of their gross profits: nothing the first year, one-sixth the second, and one quarter the third. As the duration of the contract progressed, the contract's aims became more strictly economic in nature and the extent of brazilwood commerce permitted more defined. Starting in 1505, the merchants were allowed to import 20,000 quintals of brazilwood annually, a privilege for which they paid 4,000 ducats a year. Crucially, the crown agreed to prohibit the importation of any competing red dyewood from Asia (Rondinelli, 2001: 270; Masser, 2001: 401).4 In essence, this stipulation meant that the brazilwood Loronha and his fellow merchants brought to Lisbon would be the only red dyewood available in Europe, except that which trickled in through the Levant.

The Loronha consortium dispatched expeditions to Brazil in 1502 and 1503 that began to make good on the merchants' obligations to the king and profit from the group's monopoly rights. The first expedition charted a large swath of the coast of Brazil from Cabo de São Roque in the northeast to Porto Seguro. On the way, it gathered a cargo of brazilwood and indigenous slaves for the return to Lisbon. A storm and subsequent shipwreck scattered the second expedition on the approach to the Brazilian mainland but a portion of the fleet regrouped at Cabo Frio. There, the remaining crews spent five months trading the native Brazilians for brazilwood and constructing a fort in fulfillment of the terms of Loronha's contract. The captains left two dozen men as a garrison along with a dozen cannons, weapons, and provisions for six months before returning to Lisbon in June of 1504 (Guedes, 1975b: 237-243; Serrão & Marques, 1992: 80-86; Vianna, 1972: 64-65; Vespucci, 2001: 346).

These two voyages give an idea of the motivations behind the trade with Brazil in its first years. Exploration and discovery were entwined with commercethe knowledge of new lands was as important as the goods those lands produced. Each expedition navigated large stretches of the Brazilian coast. The crews would have mapped the coast as they went and brought this valuable information with them back to Lisbon in addition to holds full of brazilwood. Moreover, these expeditions had the task of establishing commerce and a Portuguese presence in Brazil. Setting up trading factories was crucial not only to the development of trade with Brazil but also to the establishment of a de facto Portuguese claim to the territory (a de jure claim having already been established by the 1494 Treaty of Tordesillas). These early voyages thus served the national interests of the Portuguese crown as much as the commercial interests of the merchant monopolists.

Two first-hand accounts of European travelers to Brazil help reconstruct how the brazilwood trade was conducted in the sixteenth century. Frenchman Jean de Léry and German Hans Staden both accompanied voyages to Brazil in the middle of the sixteenth century and wrote accounts that were published in Europe. Together, they paint a clear picture of the exchanges between the Europeans and the indigenous Brazilians.

Brazilwood was extremely heavy and often grew some distance inland from the coast. The process of harvesting brazilwood trees was therefore quite labor intensive. The few Europeans that crewed the ships that sailed to Brazil could not harvest brazilwood in any considerable quantities and so had to rely on indigenous labor as Léry makes clear:

As for the manner of loading it on the ships, take note that both because of the hardness of this wood and the consequent difficulty of cutting it, and because, there being no horses, donkeys, or other beasts to carry, cart, or draw burdens in that country, it has to be men who do this work: if the foreigners who voyage over there were not helped by the savages, they could not load even a medium-sized ship in a year. The savages not only cut, saw, split, quarter, and round off the brazilwood, with the hatchets, wedges, and other iron tools given to them by the French and by others from over here, but also carry it on their bare shoulders, often from a league or two away, over mountains and difficult places, clear down to the seashore by the vessels that lie at anchor, where the mariners receive it (Léry, 1992: 101).

In exchange for their labor, Portuguese and French merchants would trade the natives linen and wool garments, hats, knives, mirrors, combs, and scissorsessentially basic trade merchandise, tools, and trinkets (Léry, 1992: 101; Staden, 2008: 58). This type of exchange meant that the Europeans could acquire brazilwooda valuable commodity in Europecheaply in the New World.

For the Portuguese, these exchanges occurred at a feitoria, a fortified trade post, like the one established by the Loronha consortium's second expedition in 1503. Each feitoria had a resident factor, an agent who acted as a go-between for the ship captains who came to trade with the native Brazilians. The local tribes would bring brazilwood to the feitoria where the factor would barter for it with European goods. Only the factor was allowed to mediate the transactions between the Portuguese and the indigenous peoples (Metcalf, 2005: 60-62; Marchant, 1942: 40). The French, on the other hand, had no permanent settlements in Brazil. French merchants tried a number of times to establish trading posts on the Brazilian coast but these footholds were quickly destroyed by Portuguese patrols. The French instead established a more informal method of trading brazilwood. Certain Frenchmen, who came to be known as truchements (interpreters), went and lived among the indigenous groups. These Europeans fully integrated themselves into native Brazilian society: they not only learned the indigenous language, but also accumulated social status by taking indigenous wives and even participating in cannibalistic rituals. French ship captains who arrived in Brazil would seek out these men who would act as the go-between and arrange the commercial exchanges between the native Brazilians and the Frenchmen (Metcalf, 2005: 64-74). While seemingly less efficient than the more centralized Portuguese system, the French managed to cultivate strong relationships with local groups under this system.

Two voyages in these early years demonstrate the two systems of trading brazilwood. The first is the voyage of the Portuguese ship Bretoa. In 1511, Fernão de Loronha and three of his partners outfitted the Bretoa for a yearly trade mission. In Brazil, the ship stopped first at Bahia de Todos os Santos before continuing down to Cabo Frio and landing at the feitoria established there in 1503. The Bretoa surrendered all her trade goods to the factor in Cabo Frio and he organized the trade with the natives: in the ship's ledger, the captain is quick to note that not one member of the thirty-man crew made any damaging action against the natives nor traded them any goods or weapons. The natives harvested the brazilwood from the surrounding forest and brought it to the feitoria; the crew itself, however, loaded the logs onto the ship. In addition to some native Brazilian slaves and exotic birds, the Bretoa carried back to Lisbon about 2,082 quintals of brazilwood taken from around 300 brazilwood trees (Marchant, 2005: 34-40; Dean, 1995: 372 n. 8; Baião, 1921: 343-347).

The second voyage is that of the French ship Pèlerine. Bertrand d'Ornesan, Baron of Saint-Blancard, funded the expedition to trade with the natives and establish a fort in Brazil to allow further commerce. The ship sailed from Normandy in 1531 with 120 men, goods to trade, and all the necessary materials to construct the fort. When the Pèlerine landed in Pernambuco, six Portuguese and a large number of natives attacked the French crew. These Portuguese troops were likely from the garrison of the Portuguese feitoria in Pernambuco, which heard of the French landing and sent out a patrol to attack the interlopers together with their indigenous allies. The French overpowered the coalition, however, and impressed them into helping construct a fort of their own. The French then traded extensively with the indigenous Brazilians, loading a final cargo for the Pèlerine of some 5,000 quintals of brazilwood as well as smaller quantities of cotton, exotic birds, skins, hides, and gold. Despite this impressive haul, the voyage of the Pèlerine was a failure on both its intended fronts. The ship itself was taken by a Portuguese squadron in the Mediterranean on its way back to Marseilles and the fort the French crew built lasted only a few months, destroyed by Portuguese captain Pero Lopes de Sousa later that year. In the end, the goods the expedition had acquired in Brazil never made it back to France and the foothold Bertrand d'Ornesan had hoped to establish in the territory never materialized (Guénin, 1901: 43-47).

These two voyages, that of the Bretoa and that of the Pèlerine, highlight some key aspects of the brazilwood trade in its early years. As the record of the Bretoa indicates, maintaining the integrity of the feitoria and its resident factor was crucial for the Portuguese. The crew of the ship was under strict orders not to leave the confines of the feitoria or do any side-trading with the local natives. All interactions between the Portuguese and the indigenous Brazilians went through the designated factor, ensuring direct, uniform relations between the two groups, and the natives' continued willingness to trade Portuguese goods for their labor and wood. The voyage of the Bretoa also demonstrates the slight shift in priorities since the earliest trade missions to Brazil. Once the first few expeditions had established the trade and charted the coast of the territory, the emphasis shifted to generating a regular profit from Brazil. Unlike the Loronha consortium's previous voyages which had explored and constructed a fort, the Bretoa visited a fully operational feitoria and the crew loaded as much cargo as the ship could hold. The voyage was fully committed to extracting profit from Brazil.

The failure of the Pèlerine is indicative of the trend of repeated, ill-fated French attempts to establish bases in Brazil and challenge Portuguese dominance of the trade therewith. The French crew had no fort at which to land initially and so constructed oneone that was swiftly removed by Portuguese forces. Failures such as this left French merchants relegated to using the informal system of beach landings and interpreters to trade for brazilwood. French interest in Brazilian commerce began around the same time the Loronha consortium received its contract from the Portuguese crown. In 1503, a group from Honfleur, a small port town in Normandy at the mouth of the Seine, dispatched the ship l'Espoir for an expedition. In Brazil, the crew traded goods such as spades, hardware, mirrors, and wool for brazilwood. Like in the later voyage of the Pèlerine, the dyewood carried by l'Espoir did not make it back to France, but information regarding the riches of Brazil did. Pirates captured, pilfered, and sunk l'Espoir off the Channel Islands as she was returning to France but dropped her crew off in The Hague. When the crew arrived back in Normandy, its members spread the knowledge of the potentially lucrative trade with Brazil (Tomlinson, 1970: 31-47, 51).

With this information, the floodgates opened for French merchants to tap into the brazilwood trade. In 1526 alone, at least 10 French ships made voyages to Brazil and in 1529 one expedition reportedly brought 8,400 quintals of brazilwood back to France, which would have amounted to almost half of the Portuguese contractors' annual requirement of 20,000 quintals. Normandy continued to be the hub for these expeditions with wealthy merchants such as Jean Ango from Dieppe providing financing. Captains Jean Parmentier (1520), Hughes Roger (1521), and Giovanni da Verrazzano (1522) all sailed to Brazil to harvest brazilwood with the backing of Ango. There was some institutional support for Ango's efforts too, for in 1529 he received a letter of marque from king Francis I permitting him to attack the Portuguese Brazil trade. The aforementioned voyage of the Pèlerine in 1531 and an attempt to establish a trade post on Ilha de Santo Aleixo near modern-day Recife in Pernambuco were in many ways the culmination of this early period of French attention directed towards Brazil (Serrão & Marques, 1992: 219-220; Vianna, 1972: 146-148; Morison, 1974: 588).

The Portuguese crown responded firmly to the increasing French presence in Brazil and the foreigners' challenges to Portugal's monopoly on brazilwood. First Manuel and later João III dispatched seasoned captain Cristóvão Jaques on a series of coastguard expeditions to Brazil between 1516 and 1528 to attack French shipping. During these missions, Jaques patrolled almost the full length of the Brazilian coast from Pernambuco to Santa Catarina. He also opted to close the Cabo Frio feitoria and relocate it far to the north to Igarassu on the shores opposite Itamaracá island in Pernambuco. The original trade post established at Cabo Frio by the Laronha consortium in 1503 was safe owing to its out-of-the-way location but it did little to ward off French interlopers. At its new location, the Portuguese fort would be more prominent, grant access to the higher-quality brazilwood stands of Pernambuco, and be geographically closer to Portugal. Jaques must have had a special dispensation from the crown because he was allowed to trade brazilwood during his voyages as part of his annual compensation for defending the territory. During his first expedition, he loaded three ships with brazilwood at Cabo Frio before closing the factory there and during his last expedition he loaded brazilwood at the new feitoriaat Igarassu (Serrão & Marques, 1992: 95-100, 219; Trías, 1975: 257-283).

While Cristóvão Jaques had some modest success combatting French shipping and made the strategic move to reposition Portugal's primary base in the territory, the crown soon realized that simply sending armed patrols to the Brazilian coast would be insufficient to thwart the French threat. The Portuguese crown thus initiated a series of efforts to colonize the coast of Brazil, the most serious of which was João III's 1534 decision to divide up the Brazilian littoral into fifteen captaincies which he gave as hereditary fiefs to members of the lesser nobility. Each noble captain had the right to the land and its produce within their captaincy and the responsibility to colonize it in the name of Portugal (Disney, 2009: 211). Brazilwood was an exception, however: its status remained as it was in the first three decades of the tradea royal possession requiring a royal license to trade. D. João was clear in his Charter of Donation to Duarte Coelho, the captain of Pernambuco, as to the status of brazilwood:

The brazilwood in the captaincy and any spices or drugs of any type found there shall belong to me and shall always belong to me and my successors, and neither the captain nor any other person may deal in these things nor sell them there. Nor may they export them to my realms or territories or beyond them (Schwartz, 2010: 15).

Even though he could not freely trade it, Coelho was expected as hereditary captain to guard and preserve the brazilwood in his domains from those who wished to trade it without a license. He had motivation to do so: D. João granted Coelho one-twentieth of the crown's gross profit from the brazilwood imported from his captaincy (João III, 1966: 40). Ensuring the trade in brazilwood continued legally was thus in Coelho's best financial interest. Under this arrangement, the brazilwood trade continued to be a closely-guarded royal possession in the mid-sixteenth century, but its profits helped the hereditary captains as well as the crown and the merchants who traded the commodity.

As evidenced by Jaques's dispensation to trade brazilwood on his missions, the crown had terminated the brazilwood monopoly and began to dole out numerous licenses to trade the resource by the time of the establishment of the captaincies. With more merchants involved in the colony's commerce, the brazilwood trade became more regularized in this period. The yearly expedition sent out by the monopolists gave way to multiple journeys crossing the Atlantic for brazilwood each year. The crown appointed royal factors in the captaincies' settlements that were in charge of weighing and registering cargoes of brazilwood for export to ensure royal profit from taxation of the newly-liberalized trade (Coelho, 2010: 20-21; João III, 2010: 49).

The price at which brazilwood merchants could obtain the dyewood began to rise in this period. In 1546, Coelho complained that the brazilwood licensees trading in Pernambuco

pester the Indians so much and promise them so many things that it is not right to promise It is not simply that they supply the Indians with tools, as is the custom. Rather, to persuade them to gather brazilwood, they give them beads from Bahia, as well as feather headdresses and colored garments that cannot be obtained here. Worse still, they give them swords and muskets (Coelho, 2010: 21).

The phenomenon was not just confined to Pernambuco and the northeast of Brazil either. In the south around Guanabara Bay, Hans Staden mentioned that French traders had given some natives guns and powder in exchange for brazilwood (Staden, 2008: 50). It thus seems that wherever Europeans traded for brazilwood along the coast, natives demanded more valuable goods in exchange. The problem became such that D. João instructed Tomé de Sousa, the first Governor General of Brazil, to impose a limit on the barter value that [the licensees] are to pay for the goods circulating in the territory in an attempt to reign in this inflation (João III, 2010: 49).

A combination of factors contributed to the rising price of brazilwood in Brazil. First, the greater number of merchants coming to trade brazilwood in the middle of the century caused greater demand. Part of this growth came from more royal licenses, but part of it was the result of Portuguese merchants exporting brazilwood illicitly, either without royal permission or beyond the limits of their license. Coelho remarked that he could not find anyone who does not think that he has some right to deal in brazilwood as though it were some vegetable to be sold on the market. He reported to D. João that he tried to prevent this contraband trade as the king had ordered him when he gave him rights to the captaincy, but that the level of the illicit activity was too much for him to restrain (Coelho, 2010: 21, 33).

Second, Europeans had for a few decades been bringing the same basic goods (tools, knives, simple garments, etc.) to trade. By this time, the Europeans had saturated the market for these rudimentary goods and the natives now demanded items of higher value. Coelho commented that previously when the Indians were hungry and needed tools, they would come clear the land and do all the other heavy work in exchange for what we gave them, but now, as they have plenty of tools, they no longer gather wood for the Europeans (Coelho, 2010: 21).

Third, years of brazilwood harvesting and clearing land for sugar plantations had thinned out the Atlantic Forest. Coelho noted that brazilwood had to be harvested further inland, having been deforested along the coast, meaning that indigenous laborers had to spend more time looking for brazilwood and carry the heavy logs a greater distance (Coelho, 2010: 20-21). Furthermore, Portuguese colonization had either killed a significant portion of Brazil's indigenous population or forced it to migrate further inland (Disney, 2009: 216-218, 233-236). The labor as well as the resource itself was harder to find. Brazilwood was thus becoming more expensive to obtain and the trade was becoming altogether less lucrative.

The trends that Coelho reported suggest the impending collapse of the trade as the sixteenth century wore on. That collapse did not come, however, and the trade continued through a number of political changes in the middle and latter half of the century. In 1548, D. João appointed Tomé de Sousa the first Governor General of Brazil and sent him to found the colonial capital in Bahia in an attempt to centralize royal authority in the colony. The status of brazilwood remained unchanged, however: the crown reaffirmed brazilwood as royal property that could only be traded with a license from the king (João III, 2010: 49). Licensed (and illicit) trade continued through the 1550s and 1560s when the Governors General smothered the last French attempts to colonize Brazil, and beyond 1580 when dynastic crisis in Portugal unified the Portuguese and Spanish crowns. In 1594, the trade was still lucrative enough and the extent of illegal brazilwood trading so great that D. Filipe reverted the trade back to a monopoly system (Disney, 2009: 233). The trade thus came full circle structurally to the royal monopoly under which it operated at the beginning of the century. If the brazilwood trade continued through the end of the sixteenth century and was poised to carry on into the seventeenth, brazilwood traders must have overcome the declining supply of indigenous labor and increasing coastal deforestation of brazilwood stands.

The Brazilwood Trade in the Seventeenth Century

By the beginning of the seventeenth century, a new method for harvesting brazilwood emerged that allowed traders to overcome these obstacles. This method is evident in a work attributed to Ambrósio Fernandes Brandão , a Portuguese sugar planter who lived in Paraíba in northeastern Brazil. In his 1618 Diálogos das Grandezas do Brasil ( Dialogues of the Great Things of Brazil), Brandão lays out what he saw as the five major industries of Brazil: trade in general, sugar, brazilwood, cotton, and other timber. Fortunately, his knowledge was first-hand and his detail is penetrating. Brandão describes how the brazilwood trade might have continued in spite of the issues concerning indigenous labor and deforestation:

many settlers make their living simply by going into the forest and hauling the wood out with oxen to a waterway, where they sell it to persons who have a license to ship it They go some twelve, fifteen, and even twenty leagues out from the Captaincy of Pernambuco in search of the greatest stands of it, for it cannot be found any closer at hand since the demand has been so great The men who engage in this occupation take many slaves from Guinea with axes [with them into the forest] From there they cart it in wagons, five or six logs being tied together, until they get it to storage sheds, where barges can come alongside to take it aboard (Brandão, 1987: 151).

Brandão presents a number of details that directly respond to the supposed problems facing the brazilwood trade in the early seventeenth century. With regard to the dwindling supply of indigenous labor, Portuguese settlers used African slaves to harvest the wood and transported it with the help of beasts of burden. In the face of deforestation of brazilwood trees along the Atlantic coast, these European and African brazilwood harvesters went further inland, navigating Brazil's river systems. There they were able to find pristine, untouched stands of brazilwood. Brandão says that the settlers who plied the rivers sold brazilwood to the merchants with licenses to ship it. Settlers could not truly sell the product because, as Brandão himself was quick to point out, brazilwood is His Majesty's own drug and, as such, is protected so that no one may deal in it except the king himself or those who received his license under contract (Brandão, 1987: 51). The crown firmly maintained its rights over brazilwood in the seventeenth century as it had in the sixteenth and the settlers had no right to sell the wood that they themselves did not own. Instead, as we will see, brazilwood changed hands numerous times between the forests of Brazil and the docks of Lisbon; the money that changed hands along with it represented reimbursement for labor and transportation rather than ownership over the resource.

Brandão's description of the brazilwood trade in the seventeenth century shows how the trade had become more capital intensive since the previous century. The teams that penetrated the interior had to travel greater distances to harvest and transport the wood than before, but they had a number of advantages over the indigenous Brazilians who had harvested brazilwood during the trade's earlier decades. These advantages included draft animals, wheeled carts, and barges that relieved the harvesters themselves of the physical burden. Such capital assets for brazilwood extraction were unheard of in the sixteenth century. The trade's early years saw the construction of a handful of forts, but these served as much a political purpose to strengthen Portugal's claim to Brazil as an economic purpose to store brazilwood. Labor-saving investments in the seventeenth century, on the other hand, allowed Portuguese traders to overcome the inherent disadvantage of the resource's inaccessibility. Furthermore, the slaves that now did the physical harvesting were themselves a capital investment and one that gave Portuguese settlers control over labor as a factor of production. The unwillingness of the indigenous labor force to participate in harvesting was no longer an issue. Portuguese merchants could supply labor they directed to extract brazilwood. Capital investment in the trade thus allowed the Portuguese to counteract the challenges of trading brazilwood in the face of unavailable indigenous labor and deforestation.

Brandão's description also points to a more sophisticated system of trading. The use of rivers to transport brazilwood created a more complex trade network than what had come before. Traders employed warehouses upstream along rivers close to harvesting activity and likely downstream at the mouth as well to hold the brazilwood until a ship would arrive. Bargemen would ferry the cut wood along the waterways, taking logs from storage depots to awaiting ships. No longer could brazilwood be harvested close to a settlement or feitoria around the time of a ship's landing. The new system involved more parties and required a high level of coordination between harvesters, fluvial and oceanic transporters, and factors. Far from being a primitive industry, the brazilwood trade of the seventeenth century had a dynamic, developed system of extraction.

The contracts signed between the crown and merchant monopolists after the reversion to monopolies in 1594 reflect Brandão's presentation of the trade. One example is the agreement between D. Filipe III and Luiz Vaz de Rezende that allowed Rezende to import 10,000 quintals of brazilwood per year from 1632 to 1642 (AHU CU 017-01, cx. 1, d. 157). The contract document itself is a testament to the continued importance of the trade, having been block-printed in a Lisbon printing house and comprising 12 pages and 37 total stipulations. One of these stipulations specified that only the settlers (moradores) of the Brazilian captaincies were allowed to cut and harvest brazilwood. African slaves, while not explicitly mentioned, would have also been included under this provision as property of the settlers themselves, and reports of brazilwood harvesting during the time of Rezende's contract mention the use of slave labor in Bahia (AHU CU 015, cx. 4, d. 317). Another stipulation addressed the internal movement of brazilwood within Brazil, dictating that only those who received a license from the contractor or his factors could move the goods from the interior forests to the coast. These stipulations echo the goal of the monopoly systemto reduce the prevalence of illicit tradingbut also support the schema for the trade that Brandão presented: Portuguese settlers were the ones harvesting brazilwood and a structured system of transportation existed to extract the wood from the interior where it could be found to the coast.

Coordinating the extraction and transportation of brazilwood fell on resident factors. Rezende's contract allowed him to select five factors to reside in Brazil and act as his agents there. They would take up station at major settlements in northeastern Brazil such as Ilhéus, Porto Seguro, Salvador da Bahia, and Olinda, and from there grant transportation licenses to local fluvial bargemen and arrange for the wood to be shipped back to Lisbon (AHU CU 005-02, cx. 9, d. 1067; AHU CU 015, cx. 2, d. 116). The arrival of the Santo Antônio in Porto Seguro in 1645 highlights some of the logistics managed by the factors. Paulo Barbosa, the brazilwood factor in Porto Seguro at the time, had a stockpile of brazilwood in the settlement which he transferred to captain Manuel Tomé when the ship docked. This load composed only a little over half his ship's eventual cargo of brazilwood, however. Barbosa had also arranged for additional brazilwood to be ferried from a nearby river. Perhaps he had run out of room to store any more brazilwood in Porto Seguro and so arranged for these smaller shipments to bring further loads of brazilwood from a remote location, or perhaps the timing worked out such that bargemen were bringing freshly-harvested brazilwood to Porto Seguro during the Santo Antônio's stay. Either way, the six additional loads from smaller boats completed the ship's cargo and the bargemen received 80 réis per quintal for their services (AHU CU 005, cx. 1, d. 78).

Captains such as Tomé who made the trans-Atlantic voyage between Brazil and Portugal to ferry brazilwood on the longest leg of its journey also received reimbursement for their role. Rezende's contract committed the monopolist to reimburse captains upon their arrival in Lisbon. Captains maintained their own records of the brazilwood they transported and requested remuneration from the contractor. Manuel Tomé, for instance, kept diligent records of the transactions in Porto Seguro and submitted them for reimbursement in Lisbon. He listed the amount of brazilwood he received from each source (Paulo Barbosa and the additional loads from the barges) and the freight reimbursement due for each item (AHU CU 005, cx. 1, d. 78). In the first half of the seventeenth century, the common rate for transporting brazilwood across the Atlantic was 300 réis per quintal (AHU CU 015, cx. 1, d. 53; AHU CU 015, cx. 2, d. 99). That said, most captains transported only small quantities of brazilwood on each voyage. In the first two and a half years of Rezende's monopoly, 32 ships sailed from Bahia to Lisbon carrying brazilwood. Most carried 100 quintals or less with a median cargo of 85 quintals; one carried just 20 quintals (AHU CU 005-02, cx. 5, d. 632). Such small quantities imply that ships carried other goods, namely sugar, the primary export of the colony at the time. Captains' records from the 1640s show that ships sailed from Porto Seguro laden with mixed cargoes of sugar and brazilwood (AHU CU 005, cx. 1 d. 37; AHU CU 015, cx. 5, d. 332). Thus, the schema for transporting brazilwood across the Atlantic had evolved greatly after a century and a half of trade. Unlike the trade's earliest years when monopolists would outfit their own expeditions to Brazil and bring back a cargo of almost exclusively brazilwood, in the early seventeenth century monopolists paid for brazilwood to be carried on other merchants' ships alongside other exports.

Just as the French had been the primary challengers to Portuguese dominance over the brazilwood trade in the sixteenth century, the Dutch became the Iberians' main rivals in the seventeenth century. The Low Countries had been involved in the trade since its early years, with merchants in Flanders indirectly importing the dyestuff from Brazil through the Portuguese metropole as early as 1505 (Masser, 2001: 401). In the seventeenth century, however, Holland began asserting itself directly in the brazilwood trade as the United Provinces grew as a commercial and naval power. In 1617, the prevalence of Dutch incursions in Brazil was such that the crown dispatched admiral Martim de Sá with specific orders to prevent foreigners from harvesting brazilwood. His initial mandate covered the southern captaincies of Cabo Frio, Rio de Janeiro, and São Vicente but the list quickly grew to include Espírito Santo, Bahia, Paraíba, and Rio Grande do Norteessentially most of Brazil's Atlantic coast (AHU CU 017, cx. 1, d. 7, 10, 15, 20). Martim de Sá's patrols had some impact on Dutch trading activities but not enough to prevent brazilwood contractor André Lopes Pinto from notifying the crown the following year that Dutch attacks were inhibiting him from importing the amount of brazilwood specified in his contract (AHU CU 005-02, cx. 2, d. 170).

Dutch involvement in the brazilwood trade reached its zenith during the period of Dutch occupation of northeastern Brazil (1630-1654). Under Dutch rule, brazilwood was a monopoly of the West India Company and the trade was a crucial industry of the colony: John Maurice of Nassau, the colony's first governor general, listed brazilwood second in importance only to sugar as an export of the Dutch territory (Maurice of Nassau, (2010): 246). During these years, the United Provinces controlled Pernambuco and the surrounding captaincies, giving Dutch merchants immediate territorial access to abundant brazilwood stands. Brazilwood exports started off weakly in the early 1630s, likely due to the destruction and disruption caused by the war, but grew rapidly in subsequent years (Sousa, 1978: 92-5). Prices for brazilwood in Amsterdam fell by 50% in the decade from 1630 to 1640 (Posthumus, 1946: 443-444). This drop, in the absence of a sharp decline in demand for the dyestuff (an unlikely trend during a period of economic prosperity in the Netherlands), indicates the large influx of brazilwood that came to Holland from newly-conquered northeastern Brazil.

Dutch occupation took its toll on the Portuguese side of the brazilwood trade. Most importantly, Portugal lost control of the territory with the most abundant brazilwood stands.5 Furthermore, Dutch naval patrols interrupted Portuguese brazilwood shipments from the rest of Brazil. In 1636, contractor Luiz Vaz de Rezende complained to D. Filipe that he was having difficulties importing the wood as specified in his contract. Dutch ships prevented vessels carrying brazilwood from leaving Brazil regularly and sailing directly to Lisbon (AHU CU 017-01, cx. 1, d. 156). That said, the worst of the trade disruptions were short-lived: Portuguese forces had success reconquering lost territory in the second half of the 1640s and Dutch control of northeastern Brazil came to an end in 1654. Even after the end of Dutch occupation and without direct territorial access to Brazil, traders from the Netherlands still came to Brazil to harvest brazilwood. Two ships from Amsterdam landed at Cunhaú in Pernambuco to load the dyestuff in 1657 (AHU CU 015 cx. 7, d. 597) and in 1662 two Dutch ships encountered captain Francisco de Morais at João Lostão in Rio Grande do Norte (AHU CU 018, cx. 1, d. 6).

These decades of direct Dutch imports helped make the Netherlands the center for processing brazilwood: refining the wood so it could be turned into a dye. The first stages of processing took place in Brazil at the time of harvesting to remove the bark, branches, and outer layers that did not contribute to dye-making and thus were worthless to transport across the Atlantic. In the early years of the trade and for later Dutch traders who often relied on indigenous labor where they could find it,6 native Brazilians cut, saw[ed], split, quarter[ed], and round[ed] off the brazilwood, with the hatchets, wedges, and other iron tools given to them by Europeans (Léry, 1992: 101). In the seventeenth century, the Portuguese moradores and slaves remove[d] all the outer layers, for the brazil [dye itself] is in the heartwood. In this way a tree of tremendous girth supplies a piece of wood no longer than your leg (Brandão, 1987: 151). Once in Amsterdam, these much-paired-down logs were reduced to dust so that they could later be mixed with water to create the dye. The center for this stage of the process was Amsterdam's Rasphuis, or Saw House, a penal institution for the criminals of the city. Here, prisoners would rasp brazilwood in two-man teams using a type of gang saw (Pontanus, 1611). This saw was woefully heavy, consisting of a number of rough blades strapped together. Each team had a daily quota it had to produce, which could have been as much as 60 pounds of saw dust. This method, a brutal and arduous task for the inmates, was seen as an excellent correctional tool that would reform ne'er-do-wells while contributing to Dutch industry (Sellin, 1944: 53-58; Schama, 1988: 19-20).

Correctional goals aside, brazilwood rasping was a booming business. The Rasphuis grew quickly from its founding in 1596 to dominate brazilwood processing in the Netherlands, thanks in part to some generous concessions. In 1599, the Amsterdam city council gave the Rasphuis the sole right to rasp brazilwood in the city and its environs. Later, in 1602, the States General of the United Provinces extended this monopoly to all of Holland and West Friesland. While existing penal institutions in other towns were allowed to retain their local monopolies on rasping, only the Rasphuis could export the saw dust to other countries, a crucial right that gave the Amsterdam institution primacy in the industry, much to the chagrin of similar institutions in Leiden and Rotterdam. Moreover, the 1602 edict banned private brazilwood rasping outside such penal institutions (Sellin, 1944: 54-55). Between these privileges and its location at the heart of an entrepôt flush with brazilwood in the early seventeenth century, Amsterdam's Rasphuis became Europe's center for brazilwood processing.

The Brazilwood Trade across Two Centuries

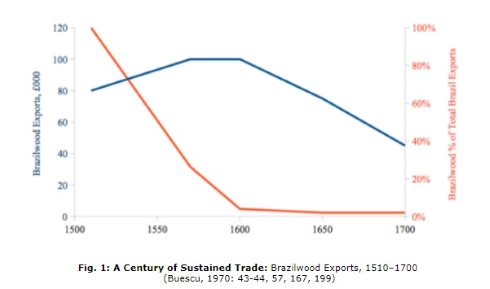

The brazilwood trade, then, continued well into the seventeenth century, but just how strong was it over a century after its inception? A look at the value of brazilwood exports throughout the trade's history gives some indication of its longevity and continued strength (Fig. 1). Historians generally pay most attention to the percentage of the brazilwood trade in the colony's export economy as a whole when discussing the trade's short duration (Buescu & Tapajós, 1967: 24). These proportions indicate the significant and uninterrupted decline of brazilwood across the sixteenth century as sugar came to dominate the export market. At the beginning of the century, brazilwood represented almost all of the colony's exports, but by the century's end it represented merely a small fraction. These relative values do not tell the whole story, though. In absolute terms, the value of brazilwood exports actually increased over the course of the sixteenth century, reaching its peak sometime in the century's later decades. Moreover, even after this peak, the trade did not drop off completely as some have suggested.7 Rather, the trade continued in significant volumes for the next hundred years: only by 1650 did the value of the trade's exports drop below that of the early years of the sixteenth century, the purported heyday of the trade, and only around 1700 had they dropped below 50% of the trade's peak about a century earlier. The brazilwood trade, then, continued well into the seventeenth century and certainly did not die out in the middle of the sixteenth century.

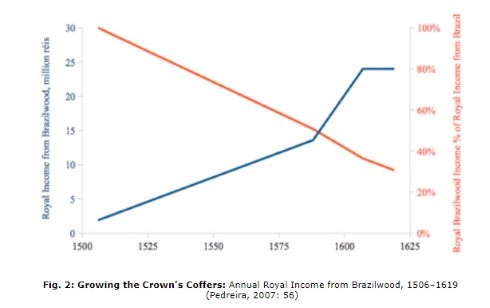

Another way to understand the lasting importance of the brazilwood trade is by examining royal income from the trade (Fig. 2). Like the value of brazilwood exports, royal revenue from the resource increased across the sixteenth century. Revenue swelled from 1.9 million réis in 1506 to 24 million réis a century later, with particularly strong growth around the turn of the century as the crown converted the trade back to a monopoly system. Even during this period of profound growth, royal revenue from brazilwood decreased as a portion of all royal revenue from Brazil as increasing sugar exports generated more duties. That said, brazilwood continued to represent a significant portion of royal revenue from the colony. Even in the early seventeenth century when tax receipts from sugar would have hit full stride, brazilwood amounted to around a third of royal income from the American colony, a far greater portion than its minuscule share of export volumes might suggest. Far from being an insignificant facet of the colonial economy, the brazilwood trade continued to profit the crown over a century after its inception.

Beyond the crown, other participants in the colonial economy profited from brazilwood. We have seen that ship captains and bargemen received compensation for transporting the wood and that Brandão reported that some Portuguese settlers made their living by harvesting trees, a reality echoed by colonial officials (AHU CU 015, cx. 2, d. 113). As for the monopolists, they too profited despite the more complex method of brazilwood extraction and transportation in the seventeenth century. Roberto Simonsen calculated that in 1602, after factoring in the price of a monopoly contract, the cost of harvesting brazilwood in Brazil, and the cost of trans-Atlantic transportation, a Portuguese brazilwood contractor could realize around six million réis net profit each year, or a 15% return on investment (Simonsen, 1937: 101). The hereditary captains continued to receive a share of royal proceeds from the brazilwood exported from their captaincies in the seventeenth century as well. Recall that D. João granted Duarte Coelho one-twentieth of the royal profits from brazilwood from his captaincy beginning in 1534. This custom prevailed into the following century: the contract between the crown and monopolist Nuno Álvares Vizeu signed in 1628 required that Vizeu pay the crown 18 million réis, of which one-twentieth would go to the captains of the captaincies from which the brazilwood came (AHU CU 015, cx. 2, d. 116). To a similar end, Duarte de Albuquerque Coelho (the fourth captain of Pernambuco and grandson of Duarte Coelho) received a large payment of over four million réis from D. Filipe II in 1619 for brazilwood that had come to Lisbon from Pernambuco (AHU CU 015, cx. 1, d. 64).

Conclusion: Brazilwood, an Atlantic Commodity

We see that, far from an ephemeral commercial endeavor that died out within the first half century of Brazil's colonial history, the brazilwood trade was a mainstay of the Brazilian economy for over a century and a half. The continued value of exports, royal income, and profitability to the trade's participants demonstrate its lingering importance to the colonial economy. Such continuity does not mean the trade had not changed over the course of a century and a half. The pursuit of the tradethe process by which brazilwood was harvested and transportedhad changed greatly in response to the two apparent threats that seemed to signal its end: coastal deforestation and a declining supply of indigenous labor. While in the sixteenth century natives harvested brazilwood close to the coast, by the seventeenth century Portuguese settlers and African slaves trekked inland up rivers to find stands of the dyewood. The trade became more sophisticated logistically and more capital intensive in order to support the new system of the brazilwood harvesting. Factors no longer negotiated with indigenous laborers at the palisade of a feitoria but instead organized a network of harvesters, fluvial transporters, and Atlantic ship captains. The monopolist merchants in the seventeenth century ceased outfitting ships themselves and paid ship captains to take smaller quantities of brazilwood aboard their vessels along with the other goods they carried. The trade's political structure had at the same time changed both greatly and not at all. It came full circle, from a monopoly in the earliest years, to numerous licenses for most of the sixteenth century, and back again to a monopoly by the early seventeenth century.

From this perspectivethat of the brazilwood trade's longevitywe can make sense of the imperial altercation between Dutch and Portuguese sailors on the coast of Brazil in 1662. Over a century and a half after its inception, the trade still had the ability to generate conflict: the Dutch at João Lostão were trying to tap into a still-lucrative trans-Atlantic trade and their Portuguese adversaries were defending an imperial economic interest. The lengths to which both parties were willing to go (be it a long, clandestine voyage or burning brazilwood to keep it out of enemy hands) are a testament to the commodity's continued import.

This same altercation points to some of the broader narratives in Atlantic history of which the brazilwood trade is now part. We have seen that brazilwood was integral to rivalries over Atlantic commerce, both between the French and the Portuguese and the Portuguese and the Dutch. Brazilwood's role in the second of these conflicts has been under-recognized due to the trade's perceived short duration. We have also seen how African slave labor replaced that of indigenous Brazilians as the trade progressed. Many studies have explored economic relations between native Brazilian and the Portuguese but this knowledge adds a new facet to discussions about the history of slavery in Brazil. The previous pages have focused on the brazilwood trade in Brazil and the Atlantic, touching only briefly on brazilwood once it reached Europe, but there are further connections to be uncovered between brazilwood and the burgeoning textile industry on the continent. How did European merchants distribute brazilwood in Europe so that the dyestuff reached dyers and textile producers? Where outside Amsterdam was brazilwood refined? What competition did brazilwood face from rival dye sources in the marketplaces of Europe? New World cochineal, African takula, and Asian sappanwood were all alternate sources of red dye in early-modern Europe. How did the relative quality, availability, and cost of these rivals affect the trade in brazilwood?

There is yet another important narrative in Atlantic history of which we now find brazilwood a part: the shift in global commerce from the Indian Ocean to the Atlantic. Long before Portuguese, French, and Dutch vessels carried brazilwood across the Atlantic, luxuries found their way to Europe from the East. Oriental goods such as sappanwood arrived in Europe through ports like Constantinople, Venice, and Genoa, carried first by ship across the Indian Ocean. In this way, the eastern sea acted as a great sea highway that linked China, the Indian subcontinent, East Africa, the Middle East, and Europe in one large trade network. The Indian Ocean was the heart of the commercial exchanges that carried goods from east to west and the merchants who plied the ocean's waters controlled the bulk of global trade (Abu-Lughod, 1989: 170-175, 261-270). When Spain and Portugal invested in maritime ventures of discovery in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, they were seeking an entrance into this center of the rich commercial web of Eurasia: they were trying to tap into the enormously profitable seafaring trade in the Indian Ocean. At the time, western Europe was a poor periphery of the Eurasian landmass, an extremity of its trade network. Europe's poverty and peripheral location, however, spurred on the expansion that eventually reversed the continent's fortunes. Europeans had few valuable commodities to exchange. They generally traded for Asian exotics with specie rather than domestic goods. If Europeans wanted to obtain the commodities of the Orient, they would have to travel themselves to meet foreign merchants because there was little motivating the foreigners to come to them (Fernández-Armesto, 2006: 119-120).

The two greatest results of Portugal and Spain's flurry of maritime exploration were the pioneering of a sea route to Asia around the Cape of Good Hope by the Portuguese and the accidental European discovery of the Western Hemisphere by Spanish ships seeking a westward route to Asia. In the grand scheme of global trade, the discovery of the Americas proved to be far more wide-reaching than the opening of a maritime route to the Indian Ocean. As Janet Abu-Lughod states, it was the European incorporation of the New World more than the takeover of the Old World that utterly transformed the dynamics of modern global commerce (Abu-Lughod, 1989: 363). What Spain and Portugal (and later England, Holland, and France) did was bring the New World into the world system of global trade. Starting at the beginning of the sixteenth century, European settlement and colonization of the Western Hemisphere led to commercial links between the Americas and other continents that did not exist previously. The colonizers exploited the Americas for their economic gain, extracting commodities and cultivating profitable cash crops to be sold in Europe and beyond. As these commercial activities grew, the Americas became inexorably intertwined with Asia, Europe, and Africa as part of a global trade network.

Leading this shift was a pair of widely-traded American commodities. The first was silver from Spain's New World holdings. Silver mining in Spanish America started in significant quantities in the 1540s with the discoveries of silver lodes at Zacatecas in Mexico and Potosí in Upper Peru (modern-day Bolivia). Large-scale exports of the metal, however, did not begin until the amalgamation process of refining silver was introduced to Mexico in the 1550s and to Greater Peru in the 1570s (TePaske, 2010: 74-75). The large quantities of silver that flowed out of Spain's American mines had a profound impact on global trade. Silver was the preferred currency in China at the time and boatloads of the metal began to flow to China via the Spanish-held Philippines. Some estimates hold that up to 70 percent of the silver mined from Spanish America went to China rather than Europe. In exchange for silver, Spanish merchants purchased large quantities of silks and porcelain, which they then shipped back to America and Spain. In the end, Mexico City and Madrid became inundated with Chinese goods bought with silver mined in Peru (Mann, 2011: 123-163).

The second American commodity was sugar from Portuguese Brazil. The first attempts to plant sugar in colonial Brazil began as early as the 1520s but not until the 1560s was sugar entrenched in the colony (Disney, 2009: 235). Sugar profoundly influenced patterns of global trade. Most of the sugar produced in Brazil went to Europe but the trade connections from the sugar industry stretched beyond those two regions. Sugar production required an enormous supply of labor and that labor came from Africa. From the late sixteenth century on, Brazilian sugar plantations fueled the Atlantic slave trade. Brazilian sugar was a commodity grown in America using African labor and shipped to Europe.

Brazilwood deserves similar regard: the brazilwood trade predates the trades in both silver and sugar from the New World. The Portuguese began exporting brazilwood from Brazil as soon as Cabral landed in the territory in 1500, while Spanish and Portuguese merchants did not start exporting silver and sugar, respectively, until the middle of the century. The arrival of Gaspar de Lemos' supply ship in Lisbon in 1500 was a watershed moment. It contained the first shipment of a major commodity to cross the Atlantic, the ocean that would go on to become the center of global commercial exchange. Commerce from a list of commodities brought the Atlantic into the forefront of world-wide trade, including brazilwood, sugar, silver, tobacco, cotton, and coffee, to name some of the most prominent. Brazilwood deserves its spot at the top of this list chronologically, though not for pride of place. Brazilwood is the first American export and the first commodity in the narrative of a global shift in commerce from the Indian Ocean to the Atlantic.

PRIMAR SOURCES

Arquivo Histórico Ultramarino, Lisbon, Portugal. Conselho Ultramarino (AHU CU). [ Links ]

Brandão, Ambrósio Fernandes (1987) [1618]. Dialogues of the Great Things of Brazil, ed. and trans. Frederick Hall, et al. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press. [ Links ]

Coelho, Duarte (2010) [1542, 1546, 1549]. Three Letters from Duarte Coelho to King John III. In Stuart B. Schwartz (ed.), Early Brazil: A Documentary Collection to 1700. New York: Cambridge University Press, 18-33. [ Links ]

João III (1966) [1534]. Letter of the Grant of the Captaincy of Pernambuco to Duarte Coelho. In E. Bradford Burns (ed.), A Documentary History of Brazil. New York: Knopf, 34-45. [ Links ]

João III (2010) [1548]. Instructions Issued to the First Governor-General of Brazil, Tomé de Sousa, on 17 December 1548. In Stuart B. Schwartz (ed.), Early Brazil: A Documentary Collection to 1700. New York: Cambridge University Press, 37-52. [ Links ]

Léry, Jean de (1992) [1578]. History of a Voyage to the Land of Brazil, trans. Janet Whatley. Berkley, CA: University of California Press. [ Links ]

Masser, Leonardo da Chá (2001) [1505]. Relação de Leonardo da Cá Masser. In Janaína Amado and Luiz Carlos Figueiredo (eds.), Brasil 1500: Quarenta Documentos. São Paulo: Editora da Universidade de Brasília, 397-402. [ Links ]

Maurice of Nassau (2010) [1638]. A Brief Report on the State that is Composed of the Four Conquered Captaincies, Pernambuco, Itamaracá, Paraíba, and Rio Grande, Situated in the North of Brazil. In Stuart B. Schwartz (ed.), Early Brazil: A Documentary Collection to 1700. New York: Cambridge University Press, 234-263. [ Links ]

Pontanus, Johan Isaksson (1611). Rasphuis aan de Heiligeweg te Amsterdam, woodcut. Nationaal Gevangenismuseum, Veenhuizen, the Netherlands. [ Links ]

Guénin, Eugène (ed.) (1901). Protestation de Bertrand d'Ornesan, baron de Saint-Blancard, commandant les galères du Roi dans la Méditerranée, contre la prise du navire la Pèlerine [c. 1532]. In Eugène Guénin, Ango et Ses Pilotes. Paris: Imprimerie Nationale, 43-47. [ Links ]

Rondinelli, Pietro (2001) [1502]. Carta de Pedro Rondinelli. In Janaína Amado and Luiz Carlos Figueiredo (eds.), Brasil 1500: Quarenta Documentos. São Paulo: Editora da Universidade de Brasília, 267-270. [ Links ]

Schwartz, Stuart B. (ed. & trans.) (2010). A Royal Charter for the Captaincy of Pernambuco, Issued to Duarte Coelho on 24 September 1534. In Stuart B. Schwartz (ed.), Early Brazil: A Documentary Collection to 1700. New York: Cambridge University Press, 14-18. [ Links ]

Staden, Hans (2008) [1557]. Hans Staden's True History, ed. and trans. Neil L. Whitehead and Michael Harbsmeier. Durham, NC: Duke University Press. [ Links ]

Vespucci, Amerigo (2001) [1502]. Carta de Américo Vespúcio a Lourenço dei Medici. In Janaína Amado and Luiz Carlos Figueiredo (eds.), Brasil 1500: Quarenta Documentos. São Paulo: Editora da Universidade de Brasília, 273-283. [ Links ]

REFERENCES

Abu-Lughod, Janet (1989). Before European Hegemony. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

Baião, António (1921). O Comércio do Pau Brasil. In Carlos Malheiro Dias (ed.), História da Colonização Portuguesa do Brasil, vol. II. Porto: Litografia Nacional, 316-347. [ Links ]

Boxer, C. R. (1969). The Portuguese Seaborne Empire: 1415-1825. New York: Knopf. [ Links ]

Buescu, Mircea (1970). História Econômica do Brasil: Pesquisas e Análises. Rio de Janeiro: APEC Editora. [ Links ]

Buescu, Mircea & Vicente Tapajós (1967). História do Desenvolvimento do Brasil. Rio de Janeiro: A Casa do Livro. [ Links ]

Dean, Warren (1995). With Broadax and Firebrand: The Destruction of the Brazilian Atlantic Forest. Berkley, CA: University of California Press. [ Links ]

Disney, A. R. (2009).A History of Portugal and the Portuguese Empire, vol. II, The Portuguese Empire. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Fernández-Armesto, Felipe (2006). Pathfinders: A Global History of Exploration. New York: Norton. [ Links ]

Gagnon, Edeline, et al. (2016). A New Generic System for the Pantropical Caesalpinia Group (Leguminosae). In PhytoKeys 71: 1-160. [ Links ]

Guedes, Max Justo (1975a). O Descobrimento do Brasil. In Max Justo Guedes (ed.), História Naval Brasileira. Rio de Janeiro: Ministério da Marinha, Serviço de Documentação Geral da Marinha, 165-172. [ Links ]

Guedes, Max Justo (1975b). As Primeiras Expedições de Reconhecimento da Costa Brasileira. In Max Justo Guedes (ed.), História Naval Brasileira. Rio de Janeiro: Ministério da Marinha, Serviço de Documentação Geral da Marinha, 226-239. [ Links ]

Mann, Charles C. (2011). 1493. New York: Alfred A. Knopf. [ Links ]

Marchant, Alexander (1942). From Barter to Slavery: The Economic Relations of Portuguese and Indians in the Settlement of Brazil, 1500-1580. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins Press. [ Links ]

Metcalf, Alida C. (2005). Go-betweens and the Colonization of Brazil, 1500–1600. Austin: University of Texas Press. [ Links ]

Morison, S. E. (1974). The European Discovery of America: The Southern Voyages, A.D. 1492-1616. New York: Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

Pedreira, Jorge M. (2007). Costs and Financial Trends in the Portuguese Empire, 1415–1822. In Francisco Bethencourt & Diogo Ramada Curto (eds.), Portuguese Oceanic Expansion. New York: Cambridge University Press, 49-87. [ Links ]

Posthumus, N. W. (1946). Inquiry into the History of Prices in Holland. Leiden: Brill.

Schama, Simon (1988). The Embarrassment of Riches. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Schwartz, Stuart B (1985). Sugar Plantations in the Formation of Brazilian Society: Bahia, 1550-1835. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

Sellin, Thorsten (1944). Pioneering in Penology. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press. [ Links ]

Serrão, Joel and A. H. de Oliveira Marques (1992).Nova História da Expansão Portuguesa, vol. VI, O Império Luso-Brasileiro, 1500-1620. Lisbon: Editorial Estampa. [ Links ]

Simonsen, Roberto C. (1937). História Econômica do Brasil. São Paulo: Companhia Editora Nacional. [ Links ]

Sousa, Bernardino José de (1978). O Pau-brasil na História Nacional, 2nd ed. São Paulo: Companhia Editora Nacional. [ Links ]

TePaske, John J. (2010). A New World of Gold and Silver. Leiden: Brill. [ Links ]

Tomlinson, R. J. (1970). The Struggle for Brazil: Portugal and the French Interlopers. New York: Las Americas Press. [ Links ]

Trías, Rolando A. Laduarda (1975). Cristóvão Jaques e as Armadas Guarda-Costa. In Max Justo Guedes (ed.), História Naval Brasileira. Rio de Janeiro: Ministério da Marinha, Serviço de Documentação Geral da Marinha, 257-283. [ Links ]

Vianna, Helio (1972). História do Brasil, vol. I, Período Colonial. São Paulo: Melhoramentos. [ Links ]

Received for publication: 05 August 2017

Accepted in revised form: 18 April 2018

Recebido para publicação: 05 de Agosto de 2017

Aceite após revisão: 18 de Abril de 2018

NOTES

2 Formerly classified as Caesalpinia echinata, recent work on Brazilwood's taxonomic classification (Gagnon, et al. [2016]) has shown that it belongs within its own genus in the legume family.

3 This narrative is best seen in Simonsen, 1937; Buescu and Tapajós, 1967; Boxer, 1969; and Schwartz, 1985. Buescu and Tapajós mention the trade continued past 1550 but give no details of the trade after that date. Brief treatments of the brazilwood trade after 1550 can be found in Vianna (1972) and Sousa (1978).

4 Rondinelli's 1502 letter says the contract lasted three years while the report by Masser notes ten. Based on the three-year gap between the two sources and the vastly different contractual terms they report, the likelihood is that they refer to different contracts that were both signed by Fernão de Loronha and his partners: a three-year contract in 1502 and a seven-year contract extension in 1505. This resolution fits with our knowledge that by 1513 Jorge Lopes Bixorda had taken over the brazilwood monopoly. For a thorough discussion of the varying interpretations of the scarce source material on early brazilwood contracts, see Sousa, 1978: 60-64.

5 One colonial official reported in 1625 that the captaincy of Pernambuco accounted for the majority of Brazil's brazilwood exports (AHU CU 015, cx. 2, d. 113).

6 Without slaves or settlers of their own, Dutch traders would have had to rely on indigenous labor for harvesting. This situation might have occurred during times the Dutch did not control territory in Brazil or when they were searching for brazilwood in sparsely colonized areas. For instance, in 1618 foreign brazilwood traders came to Espírito Santo and received help harvesting the resource from native Brazilians (AHU CU 007, cx. 1, d. 6).

7 Buescu and Tapajós (1967: 25) posit that the brazilwood trade fell vertically after the end of the sixteenth century.

Copyright 2018, ISSN 1645-6432

e-JPH, Vol. 16, number 1, June 2018