Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Acessos

Acessos

Links relacionados

-

Similares em

SciELO

Similares em

SciELO

Compartilhar

e-Journal of Portuguese History

versão On-line ISSN 1645-6432

e-JPH vol.14 no.1 Porto 2016

ARTICLES

Lineage, Marriage, and Social Mobility: the Teles de Meneses Family in the Iberian Courts (Fifteenth and Sixteenth Centuries).

Hélder Carvalhal1

1 CIDEHUS (UID/HIS/00057/2013), University of Évora, Portugal. Project Na Privança d´el Rei: Relações Interpessoais e Jogos de Facções em Torno de D. Manuel I (EXPL/EPH-HIS/1720/2013). E-mail: helderfmcarvalhal@gmail.com

ABSTRACT

This article discusses the social mobility strategies of the Teles de Meneses family throughout the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, seeking to understand their influence on the familys social evolution and improved ranking at the court. Marriage policy and service in the Iberian courts are analyzed over three different generations and from two standpoints: first, the preservation of the familys pre-acquired status; second, the diversification of the services performed in the various settings where its influence could be exercised. This will highlight the reasons behind the social evolution of this family and the subsequent granting of titles to some of its members.

Keywords: Teles de Meneses; Social Mobility; Family; Nobility; Marriage

RESUMO

O presente artigo pretende discutir as estratégias de promoção e mobilidade social da família Teles de Meneses durante os séculos quinze e dezasseis, com o propósito de compreender as implicações que daí advêm em termos de incremento social e posicionamento na corte. Para tal, analisar-se-á a política matrimonial e o serviço nas cúrias ibéricas conduzido por três distintas gerações, obedecendo a duas perspectivas: uma relacionada com a conservação do estatuto já adquirido e outra centrada na diversificação dos serviços prestados nas variadas esferas de poder, percebendo desta maneira as razões para o consequente incremento social e titulação de alguns membros.

Palavras-chave: Teles de Meneses; Mobilidade Social; Família; Nobreza; Matrimónio

Introduction

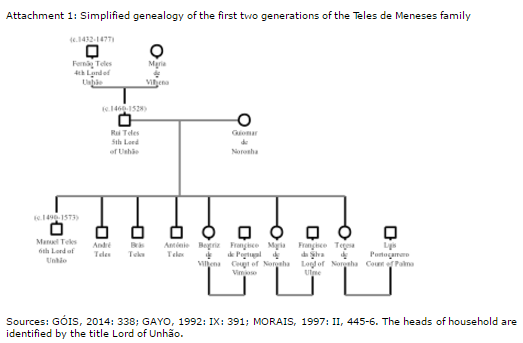

This articles main goal is to discuss the social mobility strategies of the Teles de Meneses family at the end of the fifteenth century and during the first half of the sixteenth century, by examining both the practical execution of such strategies and the instruments employed to attain the social status they enjoyed at the time. The family under analysis is one of the branches of the Silva lineage,2 who, as a result of the services they rendered at the court, were rewarded with the County of Unhão in 1636 (Freire, 1927: II, 73). The article will follow the trajectory of Fernão Teles de Meneses (c. 1432–1477), the fourth Lord of Unhão, and of his descendants up to the second half of the sixteenth century, encompassing a period corresponding to three generations.

I shall argue that two main variables lay at the root of the substantial degree of social mobility demonstrated by this family from the mid-sixteenth century onwards. The first variable relates to the progressive stabilization of a courtly and political hierarchy in the context of the Portuguese monarchy. In order to secure for themselves the best position possible, the members of this family resorted to a series of social and political practices, ranging from dedicated service at the Iberian royal courts to the pursuit of a deliberate marriage policy.

This first variable gave rise to another feature, the services provided by family members at the Portuguese and Castilian courts, which grew in visibility from the reign of Manuel I onwards. Court service will be approached from a dual, and not necessarily concomitant, perspective: on the one hand, royal service was simply the result of the Teles de Meneses proximity to the royal family, which afforded them the obvious rewards within a favor-based economy. From another perspective, it is important to assess the limits of the political fides as it was practiced by this extended family, considering their taste for high-ranking employment in the Portuguese crown dating back to the Middle Ages. During the first half of the sixteenth century, the range of courts at which members of the family rendered service became increasingly diverse. This raises the question of how family members dealt with the issue of fealty and, in turn, of whether individual princes exploited their clienteles in order to increase their own power. In spite of such ambiguities, the investment made by the various family members across such spheres of power led to an inevitable increase in their social capital, exploited by the extended family by virtue of their kinship and the formal and informal relations they developed in both kingdoms. In turn, the enhanced social capital obtained among the Iberian princes and monarchs ensured that the family members involved in the process would gain in both power and influence, in the form of titles, rents and land, as well as high-ranking positions and offices in their respective courts.

On a more general note, and in accordance with the vast historiography produced about the role of royal and noble courts as a space for self-affirmation, patronage and client-patron relationships, the (not necessarily concurrent) viewpoints adopted in this articlethat is, the stabilization of a constellation of political agents at court and the services rendered by individuals at two royal courts simultaneouslyrely upon two basic premises. The first such premise concerns the proximity to the monarch, which mightor might notbe the consequence of high office. It thus differs from the second premise, which is social status. Historiography has indeed highlighted the important role played in decision-making by those servants who were physically closest to the prince (Starkey, 1973). The period under analysis was characterized by a certain ambiguity between features that were distinctive to the late Middle Ages and to the Early Modern court. Such ambiguity results in the fact that the two above-mentioned premises do not always coincide. Therefore, the condition of being close to the prince and/or the king did not always mean belonging to the high nobility. Theoretically, for the lower strata of the nobility, the possibility of social ascension depended on the efforts of the interested parties. Most importantly, it relied on the monarchs own favor and his acceptance of the presence of these parties. However, the ambivalence resulting from serving the monarch was subject to a number of factors. One such factor was the self-image of the king as a natural leader among the nobility, and the need for him to act accordingly (Elias, 1987: 65; Duindam, 1995: 49-56).

The period studied in this article, encompassing the second half of the fifteenth century and the first half of the sixteenth century, has been described as quite favorable to social mobility within the kingdom (Pereira, 2003). Much of this paradigm may be explained by three aspects. First, the bureaucratic needs of the royal household, leading to recruitment from among non-noble ranksa policy that had clear social consequences in the short term (Gomes, 2003: 16-55). Second, the opportunities prompted by maritime expansion, which allowed the second children of nobles to occupy administrative and military positions in the African outposts and, later, in the Estado da Índia (Boone, 1986). Lastly, marriage used in its political role as a means of forging alliances, raising social status, and even collecting magnanimous endowments (Cunha and Monteiro, 2010: 51-53).

Aside from the diversification of the services provided, due to an increase in opportunities, it is important to understand whether the concessions made to descendants, along with the solidarity ties at stake, would have worked as the main catalyst for social ascension, or if the most relevant factor was instead the investment made in client-patron interdependency, with considerable implications for the monarchys political arena.

With these considerations and objectives in view, an analysis will be carried out regarding the marriage policy and the princely service of the Teles de Meneses at the Iberian courts across three generations, clarifying the familys behavior in the light of both the corresponding political context and the pursuit of titles of nobility, leading to an ever rising social status.

Political context

Before initiating this discussion, it is necessary to consider the centuries-old tradition of paying service to the crown, not only on the part of the Teles de Meneses family, but also on the part of other families who were similarly related to the Silva lineage. Indeed, the most remote ancestors of the Silvas, with branches existing in both Castile and Portugal, had been close to the Portuguese courts sphere of influence since at least the middle of the thirteenth century (Ventura, 2009: 216). During the rule of the Avis dynasty (from 1385 onwards), the various branches in the lineage usually provided royal service either to the royal household or to the newly established houses of the royal infantes, specifically to the dukedoms of Viseu-Beja and Coimbra. For instance, the support offered to Infante Pedro by Aires Gomes da Silva, the Lord of Vagos and head magistrate at the Casa do Cível (a high court of law), did not result in his being cast out from the royal sphere of influence, since Afonso V pardoned all defectors soon after the Battle of Alfarrobeira (1449), in which Pedro was defeated (Moreno, 1979: I, 659). After obtaining the royal pardon (1453), Aires and his sons were able to return to the court, having briefly regained some significant offices in the royal administration: one of the sons, Fernão Teles de Meneses, was allowed to inherit a substantial share of the jurisdictions his father had enjoyed (Freire, 1927: II, 51; Moreno, 1979: II, 1048).

Fernão possessed no title and enjoyed only a middle ranking within the hierarchy of nobles, but his close relationship with the court and the offices he occupied granted him some degree of influence at Afonsos court. This was enough for him and his descendants to earn rewards from the fides and the services carried out, in the form of highly coveted courtly offices and even jurisdiction rights in the Portuguese Atlantic, a fertile ground yet to be explored (Riley, 1998: 152). Likewise, Fernão participated in various campaigns in North Africa, serving the king and Infante Fernando at al-Qsar as-Seghir (Alcácer-Ceguer, 1458), Tangiers (1463) and Asilah (1471) (Moreno, 1979: II, 1047-53). Historiography has highlighted the close affinity between Queen Isabel and DonaBeatriz de Meneses, the mother of Fernão Teles and her sometime chambermaid and maid of honor (Freire, 1927, II, 51-3). Several authors have approached the role of interpersonal relations and of the concept of fealty in supporting the way of life at the Early Modern court (Mousnier, 1982; Dedieu and Moutoukias, 1998). Perhaps this informal relationship between the two women was one of the reasons why Fernão was so swiftly readmitted to the royal court to enjoy significant benefits, among which were the positions of head steward to Queen Leonor, João IIs consort, and chamberlain to Princess Joana (known as theExcelente Senhora).

As will soon become clear, these dynamics designed to safeguard power were a distinctive, underlying feature of the marriage policy implemented by the founder of this branch of the lineage, Fernão Teles de Meneses; they are also traceable in the continuous targeting of different spheres of power, as well as in the increasing diversity of the services performed.

Marriage policy

Table 1: Lineage and male line in the Teles de Meneses family (c. 1450-c. 1550)3

| Generation | Average number of children per male heir | Average number of male heirs per male heir | Average number of legitimate children per male heir |

| 1st | 6 | 4 | 6 |

| 2nd | 5 | 3.5 | 4.5 |

| 3rd | 3.7 | 2.9 | 3.1 |

Sources: GÓIS, 2014: 337-9; MORAIS, 1997: II, 445-55; GAYO, 1992: IX, 391-407; FREIRE, 1927: II, 73-105; FARIA, 1956: 127-9.

It is legitimate to say that, to a certain extent, the marriage policy implemented by the Teles de Meneses branch ever since its creation provided the conditions necessary for every second child to bear progeny. The lesser number of offspring in subsequent generations was prompted by variables such as a rise in male mortality rates (chiefly deriving from military duties carried out in North Africa) or their admission into the military orders, which imposed vows of chastity and restrictions on marriage. To a certain extent, the latter variable can help us to understand the considerable fall in the number of legitimate offspring during the second and third generations of the family.

The substantial mortality rate of male heirs at the time, coupled with a tendency to give younger females away to a religious life, generally accounted for the concentration of wealth in the hands of only a few heirs, or even just one. This behavior was common to most families in the upper echelons of the nobility. However, in the lowest strata, to encourage the marriage of every descendanteven the female offspringmight prove to be the shrewdest strategy, since the meagerness of the familys assets would not compensate for their concentration in the hands of just one or a few individuals (Boone, 1986).

In the case of the Teles de Meneses family, their behavior regarding the marriage market reveals the adoption of two different strategies. On the one hand, the marriage options for the female offspring called for extreme care. Even in the third generation, marriage to members of the titled nobility did exist (see Tables Table 4 and Table 5), which contradicts the tendency for the second sons to embark on a religious career. On the other hand, ever since the first generation it had been common for male heirs of this family to be admitted to both the mendicant and the military orders (such was the case, for example, with Aires Teles of the first generation, and Jerónimo Teles of the third). The choice to integrate these men into such institutions is, apparently, indicative of a profile similar to that of the upper aristocracy, thus enabling the concentration of assets in the hands of the lowest possible number of children. The compulsory assignment of these resources, as imposed by their entailment (the morgadio) at the time of Maria de Vilhena in 1483, was ratified in 1504 by Rui Teles de Meneses, which also contributed to the adoption of the latter arrangement.4 Nonetheless, based on the information available, such actions may be considered ambivalent. In part, they reflected the ambitions of a family who, in spite of their proximity to the royal court and unlike some of their distant relatives, did not belong to the kingdoms highest nobility.

Table 2: Marriage policy applied to the direct offspring of Fernão Teles de Meneses (c. 1432-1477) and Maria de Vilhena – first generation.

| Descendant | Consort | Social status | Social Mobility |

| André Teles | n/a | n/a | n/a |

| Rui Teles de Meneses | Guiomar de Noronha | Non-titled nobility | Identical |

| João de Vilhena | n/a | n/a | n/a |

| Aires Teles | n/a | n/a | n/a |

| Joana de Vilhena | João de Meneses | Titled nobility | Higher |

| Filipa de Vilhena | Nuno Martins de Silveira | Non-titled nobility | Identical |

Sources: GÓIS, 2014: 337; FREIRE, 1927: II, 76; GAYO, 1992: IX, 391; MORAIS, 1997: II, 445; FARIA, 1956: 127-8.

Table 3: Marriage policy applied to the direct offspring of Rui Teles de Meneses (c. 1460-1528) and Guiomar de Noronha – second generation.

| Descendant | Consort | Social status | Social Mobility |

| Fernão Teles | n/a | n/a | n/a |

| Aires Teles | Inês de Noronha | Non-titled nobility | Identical |

| Manuel Teles de Meneses | Margarida de Vilhena | Non-titled nobility | Identical |

| Brás Teles | Catarina de Brito | Non-titled nobility | Identical |

| André Teles da Silva | Branca Coutinho | Non-titled nobility | Identical |

| Beatriz de Vilhena | Francisco de Portugal | Titled nobility | Higher |

| Teresa de Noronha | Luís Portocarrero | Titled nobility | Higher |

| Maria de Noronha | Francisco da Silva | Non-titled nobility | Identical |

Sources: GÓIS, 2014: 338; FREIRE, 1927: II, 80; GAYO, 1992: IX, 391; MORAIS, 1997: II, 445-6; FARIA, 1956: 128.

Marriage policy applied to the direct offspring of Manuel Teles de Meneses (d. 1573) and Margarida de Vilhena – third generation5

| Descendant | Consort | Social status | Social Mobility |

| Fernão Teles de Meneses | Maria de Castro | Non-titled nobility | Identical |

| Jerónimo Teles | n/a | n/a | n/a |

| Maria de Vilhena | Fernando de Noronha | Non-titled nobility | Identical |

| Joana de Vilhena | Afonso de Noronha | Titled nobility | Higher |

Sources: GÓIS, 2014: 338; GAYO, 1992: IX, 391-2; FREIRE, 1927: II, 83-4; MORAIS, 1997: II, 446; FARIA, 1956: 128.

Marriage policy applied to the direct offspring of André Teles da Silva (d. 1562) and Branca Coutinho – third generation

| Descendant | Consort | Social status | Social Mobility |

| Rui Teles da Silva Coutinho | Leonor de Manrique | Non-titled nobility | Identical |

| Paulo da Silva | n/a | n/a | n/a |

| Brás Teles | n/a | n/a | n/a |

| Aires Teles de Meneses | Brites de Aragão | Non-titled nobility | Identical |

| Bernardim Teles | n/a | n/a | n/a |

| Manuel Teles Coutinho | n/a | n/a | n/a |

| Lourenço Teles Meneses da Silva | Joana de Moncada | Titled nobility | Higher |

| Guiomar de Vilhena | Fradique de Toledo | Titled nobility | Higher |

| Maria Coutinho | Lopo de Alarcão | Non-titled nobility | Identical |

| Beatriz Coutinho | Vasco da Gama | Non-titled nobility | Identical |

Sources: GÓIS, 2014: 339; MORAIS, 1997: II, 453; FREIRE, 1927: II, 80-1; GAYO, 1992: IX, 405-6; FARIA, 1956: 129.

As shown in Table 2, all the offspring of Fernão Teles de Meneses married members of influential families at court (except for André Teles, João de Vilhena and Aires Teles, all of whom never married). The heir Rui Teles de Meneses (c. 1460-1528), the fourth Lord of Unhão, married Guiomar de Noronha, the daughter of Pêro de Noronha, João IIs head steward and the Commander-in-Chief (comendador-mor) of the Order of St. James in Portugal ( Ordem de Santiago). A similar alliance was to be noted in the marriages of Joana and Filipa de Vilhena, respectively, to Nuno Martins de Silveira, Queen Catarinas head steward, and João de Meneses, known as the Conde-Prior due to his accumulation of offices and titles. The strategy of attempting to maintain the familys offspring within the sphere of the court is quite clear. Let us now consider the situation of the following generation.

An analysis of Table 3 shows that such a trend continued to exist: the practice of marrying male heirs to the offspring of court officers was maintained, provided that those officers occupied either central administrative positions (such as Inês de Noronhas father, Álvaro de Castro, who was governor of the Casa do Cível) or positions in overseas territories (such as Rui Dias de Sousa, the governor of al-Qsar as-Seghir and the father of Branca Coutinho). On the other hand, great emphasis was placed on the matrimonial alliances of female descendants, since a number of marriages took place to men of higher social standing (for example, Francisco de Portugal, the first Count of Vimioso), or alternatively to nobles whose families were close to the court and/or were prominent figures within it (for example, to Francisco da Silva, a distant relative of the extended family). Regarding these matrimonial options, particular attention should be paid to the surrounding political context. As will be demonstrated later on, a key aspect for understanding the high rate of social mobility of the second children (in this case, the daughters of Rui Teles de Meneses) was the diversification of services provided by both men and women to the Iberian royal courts.

The marital unions recorded among the progeny of Manuel Teles de Meneses (d. 1573), the fifth Lord of Unhão, highlight the marriage policy practiced by their direct ancestors. Once again, the firstborn son (and potential heir) married the daughter of a court official (here, Jerónimo de Noronha), who served as lady-in-waiting to Queen Catarina, while the female children were married to similar or even higher-ranking gentlemen. Such was the case with Joana de Vilhena, who married Afonso de Noronha, the fifth Count of Odemira.

It is, however, important to point out that such patterns were not exclusive to the progeny of the heir to the jurisdictions, lands and entailed property of the lordship of Unhão. There is evidence that this policy applied more widely within the family branch, as it was followed by all the descendants, despite slight variations depending on the available marriage options and the opportunities resulting from the services being rendered at court or overseas. The lineage of the following descendants emphasizes this idea: considering the offspring of André Teles da Silva (or Teles de Meneses, depending on the author), we can see a marriage policy that was simultaneously conservativeas far as social status was concernedand expansive.

The familys propensity for promoting marriages with Castilian families is noteworthy. By proceeding in this way, the family was attempting not only to conserve its social status, but if possible to enhance it. This increment in the matrimonial market should not, however, be seen merely as a consequence of the mobility of servants from the houses of the royal princes, such as the departure of Rui Teles de Meneses, fourth Lord of Unhão, to Castile, to serve in the entourage of Empress Isabel. The protection gained from becoming part of this entourage was considered to be a major advantage in the plethora of marriage arrangements. One should also bear in mind that Teresa de Noronha was later to marry Luis Portocarrero, the second Count of Palma. However, considering the marriage options available, the evidence indicates that this was an alternative solution. Indeed, Rui Teles de Meneses had attempted to arrange the marriage of this daughter of his to Alfonso Téllez, the heir to the Marquisate of Villena. The direct assistance of Emperor Charles V suggests that the crown was, at least, interested in ensuring that Teresa de Noronha married a man who would be worthy of the Empresss lady-in-waiting status. In this case, the political purpose of the marriage arrangement was to promote the familys relations with its Castilian counterpart, considered at the time to be among the great noble houses of Castile and Aragon (the so-called Grandees). When the arrangement failed, Rui Teles had to seek an alternative. 6

The ties established abroad arose from the opportunity and interest in marrying offspring (especially second children) to members of a socially or hierarchically well-positioned family. While there was a tendency to maintain homogamy in political marriages in the case of male descendants, the marriage policy for women was one of hypergamy. This explains why Guiomar Vilhena, the daughter of André Teles da Silva, married Fradique Toledo, the high steward of the household of Prince Carlos and the son of the third Count of Alva de Liste. There were also, naturally, some exceptions to this tendency. The marriage of Lourenço Teles Meneses da Silva, the son of André Teles da Silva, to Joana de Moncada (or Mendonça) may be understood as one such case in which the acquisition of titles through marriage was directly related to the occupation of high office, with all of its subsequent rewards.

The court and the granting of offices and titles

In general terms, the growing number of offices that were granted (Table 6) can be explained by the previously mentioned factors: the increased bureaucracy associated with the royal administrative structures, and the additional opportunities opened up by the overseas expansion. The second and third generations of the family, in particular, benefited from the need to empower the households of Manuel Is children, elevating the family members to the higher echelons within the hierarchy. This allowed them to build upon their pre-existing influence by populating these various structures with their descendants and relatives. Furthermore, the family took full advantage of the overseas offices granted to them, since by the third generation they had obtained a high number of posts in the administrative structures of North Africa and the Estado da Índia, serving as captains, captains-general and even as governors/viceroys. Services were also rewarded through the granting of commanderships of the military orders. Indeed, the granting of positions in the military orders of Avis, Christ and St. James is clearly notable from the third generation onwards (Olival, 1988: II, 463-4), which were slightly higher in number than the positions granted within the Order of Malta and other foreign military institutions, such as the Order of Alcántara in Castile, which provided Lourenço Teles da Silva with a commandership.

Number of offices and titles granted to the Teles de Meneses family, per generation (c. 1450-c. 1590)7

| Generation | CORH | RAO | OVO | EMB | CMO | EO | T |

| 1st | 3 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| 2nd | 4 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 1 | 0 |

| 3rd | 7 | 7 | 8 | 1 | 8 | 1 | 1 |

Caption: CORH = Chief offices in the royal household (including the princes households); RAO = Royal administration offices; OVO = Overseas offices; EMB = Embassies; CMO = Commanderships of the military orders; EO = Ecclesiastic offices; T = Titles.

Both the male and the female progeny of Rui Teles de Meneses tend to fit into this pattern of diversification. Rui, the head of the family, must have been extremely influential within the court, as he succeeded in placing all of his four subsequent children within the courts institutional sphere or in households related to it, thus promoting the preservation of his lineage within such circles of power. This was particularly clear in the house of Infante Luís, where Rui Teles guaranteed his sons positions: Brás Teles inherited the offices of provost (guarda-mor) and high chamberlain (camareiro-mor); André Teles was appointed the high steward (mordomo-mor); and António Teles was granted the office of head chaplain (capelão-mor).8 It should be noted that, in institutional terms and when taken together, the spaces which these men oversawthe chamber, the hall and the chapelrepresented an astonishing platform of influence and power, providing significant access to this prince as master of the household, and conditioning his capacity to allocate patronage. This confirms the tendency of this family to firmly establish itself in the above-mentioned social structure, with the offspring being appointed to key domestic sectors.

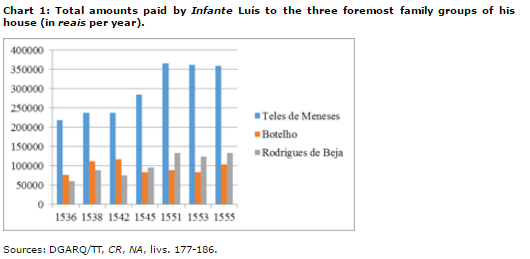

The payments in question (see Chart 1) might not relate exclusively to services carried out at court. On many occasions, gifts made directly by the prince, or under his influence, came in the form of administrative, fiscal, and military offices. As far as this family is concerned, sizeable grants include those made by Infante Luís to André Teles da Silva and Brás Teles, appointed respectively as governors (alcaides-mor) of Covilhã, and Seia and Moura. The inclination to regard offices such as these as a family legacy is equally clear, at least from the second quarter of the sixteenth century onward. João Gomes da Silva, the son of Brás Teles, inherited the position of governor of Seia from his father, keeping the office in the family until the period of the restoration of Portuguese independence, in 1640. Brás de Teles firstborn son, Rui Teles de Meneses (named after his grandfather), would be granted the officeheld by his father before himof governor of Moura. André Teles firstborn son, Rui Teles de Meneses Coutinho (named after his cousin and grandfather) would also be appointed governor, just like his father, a position which in turn was passed on to his offspring (Gayo, 1992: 394, 406; Sousa, 1947: 335).

The inclusion of Rui Teles de Meneses progeny in the entourage escorting Princess Isabel to Castile, upon her marriage to Carlos V, may have benefited from the affinity between Isabel and Guiomar de Noronha. Indeed, Rui Teles de Meneses wife had been summoned to the palace very early on in her life (1504), in order to take part in the princesss upbringing.9 Not only did this turn into a huge advantage for Guiomar, it also especially benefitted her female descendants, who were shown priority among the women eligible for inclusion in Isabels entourage. Despite the attempts to remove Portuguese officials from the empresss household through the appointment of prominent Castilian nobles to the highest positions there (Labrador Arroyo, 2005), Isabels grandson, Rui Gomes da Silva, was able to establish himself at court, thanks to his proximity to Prince Felipe (later, Felipe II), thus improving his social standing in a remarkable way, having been shown favoritism and granted various titles (Boyden, 1995). To a certain extent, such an influence would even benefit Ruis brothers. For example, Fernando Teles da Silva served Filipe II in Milan, became governor of Asti, and married Juana de Moncada, the Marchioness of Favara (Álvarez-Ossorio Alvariño, 2001: 87). In addition to the services provided at the households of the various princes, the family never ceased to render services directly to the king. These services were rewarded through fixed regular payments and miscellaneous graces and favors, with family members enjoying the rank of fidalgos da Casa Realnoblemen of the royal household.

One should also highlight the overseas interest of some family members, whether participating in colonial settlements or benefiting from colonial trade. Such was the case with Brás Teles de Meneses, who in 1524 was authorized to keep 3,200 arrobas (approximately 106 lb) of sugar from Madeira and to sell it abroad, exempt from the payment of duties (the dízima) to the crown. That such transactions had already taken place beforehand is known from the fact that Brás Teles de Meneses authorized his representative, Manuel Carvalho, to ship a similar amount of this product to Venice, where it would be sold.10 Though we cannot be certain about the exact profits from this business, there is evidence of a subsequent attempt to expand it to Brazil, since, in 1541, Brás Teles de Meneses was granted some land in the captaincy of Espírito Santo, by the captain-major at the time, Vasco Fernandes Coutinho.11 From a broader perspective, the grant may relate to the royal approval (by Afonso V, in 1474) of the purchase of the island of Flores (in the Azores), together with its lordship rights, from João de Teive by Brás grandfather, Fernão Teles de Meneses. Fernão was given ownership of the domain of Sete Cidades (also in the Azores) as well as any territories discovered by him, excluding those around the Guinea region (Meneses, 2005: III, 243-260). Although granted at different periods, both jurisdictional rights reflect the involvement of some family members in colonial endeavors, thus enhancing the social status of the Teles de Meneses family, while meeting the crowns need for maritime exploration and the settlement of newly conquered territories.

That mutual support was exercised between members of the family regardless of their proximity in terms of kinship is noticeable from the assignments they carried out on behalf of their lords. During Catarina of Austrias regency, there is evidence of favors requested by André Teles de Meneses for his son, during the latters employment as an ambassador in Castile and Rome, and until his death in 1562. As a reward for those services, the regent Catarina promised to grant Aires Teles, Andrés son, the command of a fortress in India.12 The choice of André Teles as an ambassador to Castile was far from being an innocent one: in the 1530s, he had already been sent as an envoy of Infante Luís to the Castilian court, to discuss the latters private business.13 It may, therefore, be concluded that the prior experience of André Teles, taken together with the social capital that he was gradually able to acquire, justify his mandate for the crown, André keeping his role as a facilitator of communications between the two courts.

Another broad implication of this analysis is that Rui Gomes da Silva, Prince of Eboli and Duke of Pastrana, also used his position to influence the granting of commanderies to his kinsmen in Portugal.14 Assuming that arrangements of this type were widespread, it can be inferred that interpersonal relationships, in addition to a thoughtful marriage policy, facilitated the establishment of a platform for family power, whose profits were shared among the various family members. An intricate web of informal contacts also fed such a platform, working on both sides of the border, where family members used their privileges of greater access to the prince in order to promote this system.

Conclusions

As historians have stated, the diversification of the services provided to the crown was a crucial factor in guaranteeing the sustainability and even the expansion of aristocratic lineages in the process of upward social mobility, particularly when considering that such mobility was very common during the period under analysis (Cunha, 2009). In the particular case of the Teles de Meneses family, this diversification was not achieved merely through the several individual actions performed by its members over a considerable period of timenamely holding prominent offices at the royal household and the princes households and important positions in both the central and the colonial administrations; serving in diplomatic missions; and holding military posts. The family also invested in the close relationships arising from its service to other sovereigns. Additionally, advantages were obtained from the political support that the various members of the extended family permitted each other. As an example, consider the actions of Rui Gomes da Silva, who, in recommending grants for his fidalgo cousins in the royal household, overlooked the political strife between the partisans of Catarina and those supporting the regency of Henrique, during the minority of King Sebastião.

If we consider the earning of titles as another possible goal within the lineage, only the Castilian branch of the family was successful (as Rui Gomes da Silva, Fernando Teles, or Lourenço Teles da Silva proved). Due to a number of different factors, the family members who served in Portuguese courts experienced a slower development in their upward mobility process. During the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, they never accomplished the same level of gains as those achieved by their distant relatives, who actively took part in the maritime expansion and in courtly service (Cunha, 2009).

Ironically, to a certain extent, the regular services provided by members of the family at the household of Infante Luís were to hinder the social progress of several individuals, since this prince was not himself successful in promoting his own particular standing. Neither did the attachment of those individuals to the crown do much for their status. Although this is still unproven, it seems likely that competition for the kings patronage was much fiercer at the royal court than it was in the princes households. The latter had fewer resources to offer when compared to the crown.

Apart from the patterns demonstrated so far, there are also other conclusions to be drawn. A political interpretation may be made, based, for instance, on the familys behavior during the dynastic crisis of 1580. Some historians have found it difficult to explain the reasons why Fernão Teles de Meneses, the governor of Portuguese India, was so eager to proclaim his allegiance to Filipe II (sworn in as the new king in 1581) before leaving Goa. His hesitation had been due to the close relationship between himself, his father (Brás Teles de Meneses) and Infante Luís, in addition to his being, quite plausibly, sympathetic to the cause of the latters illegitimate son, António, the Prior of Crato. Essentially, the familys behavior and the mutual support network connecting its memberseven the most remote onesmay help to explain their preference for serving with the Castilian king. Some authors have already highlighted the probable conversations between Rui Teles de Meneses, the second governor of Moura (and the brother of Fernão Teles de Meneses), and Cristóvão de Moura, concerning their eventual support for Filipe IIs claim to the Portuguese throne (Colleción, 1845: VI, 294). For some, such clues have been enough to place the family as supporters of Filipe IIs cause (Sampaio, 1921: 15-6). Yet, considering the diversity of offices performed at the various Iberian royal courts, it is very much to be expected that family alliances prevailed over the bonds of allegiance and fidelity to the prince being served. In spite of the many rewards accumulated over time from the Portuguese crown, the princes households (particularly those of Isabel and Luís), and the offices held at the central and overseas administrations, in the end it was the will of the family which carried most weight when the time came to make a decision. This implied shifting their allegiance and services to Filipe II, since he would probably be in a better place to reward the family members for their support. Likewise, patriarchal power would be reinforced in terms of both decision-making within the family and the planning of their descendants future, considering the interests of the lineage (Frigo, 1985).

The existence of a coherent family strategy for the period studied here is open to discussion. Nevertheless, the arguments previously stressed regarding marriage policy and the political solidarity among its members leads one to think that, at least in the time of Rui Teles de Meneses, the fifth Lord of Unhão, and his descendants, family interests were taken into serious consideration. In fact, the strategy mentioned here does not differ considerably from that of other case studies from the same period, such as the Meneses or the Cunhas (Cunha, 2009). It was based on the premise of maximizing what the matrimonial market could offer, especially to daughters and some second sons, a strategy attributed to families that did not belong to the highest nobility (Boone, 1986: 867). Alternative ways of guaranteeing social mobility to descendants other than the first-born came in the form of courtly service. Hence, arranged marriages, accompanied by services rendered through offices at court and overseas, were part of a typical path of social ascension. From that viewpoint, the behavior of the Teles de Meneses family before 1580 was decisive for its future success in the noble hierarchy, always taking advantage of the current political context and profiting from it.

ABBREVIATIONS

AGS: Archivo General de Simancas

CC: Corpo Cronológico

CDJ: Chancelaria de D. João III

CDM: Chancelaria de D. Manuel I

CR: Casa Real

DGARQ/TT: Direcção Geral dos Arquivos/Torre do Tombo

Est: Estado

Fl: Folio

Leg: Legajo

LN: Leitura Nova

Mç: Maço

Nº: Número

NA: Núcleo Antigo

BIBLIOGRAPHY AND PRINTED SOURCES

Álvarez-Ossorio Alvariño, Antonio (2001). Milán y el legado de Felipe II: Gobernadores y Corte Provincial en la Lombardía de los Austrias. Madrid: Sociedad Estatal para la Conmemoración de los Centenarios de Felipe II y Carlos V. [ Links ]

Boone, James L. (1986). Parental Investment and Elite Family Structure in Preindustrial States: A Case Study of Late Medieval-Early Modern Portuguese Genealogies. American Anthropologist, 88 (4): 859-878. [ Links ]

Boyden, James (1995). The Courtier and the King; Ruy Gómez de Silva, Phillip II and the Court of Spain. Berkeley: University of California Press. [ Links ]

Cunha, Mafalda Soares da (2009). Nobreza, alianças matrimoniais e reprodução social. Análise comparada dos grupos familiares dos Meneses e Cunha (séc. XV-1640). [ Links ]

In Amélia Aguiar Andrade, Hermenegildo Fernandes and João Luís Fontes (eds.), Olhares sobre a História. Estudos oferecidos a Iria Gonçalves. Casal de Cambra: Caleidoscópio, 741-756. [ Links ]

Cunha, Mafalda Soares da and Monteiro, Nuno G. (2010). Aristocracia, poder e família em Portugal, séculos XV-XVIII. In Mafalda Soares da Cunha and Juan Hernández Franco (eds.),Sociedade, Família e Poder na Península Ibérica. Elementos para uma História Comparativa. Évora and Múrcia: CIDEHUS/Universidade de Évora and Universidade de Múrcia, 47-75. [ Links ]

Dedieu, Jean-Pierre and Moutoukias, Zacarias (1998). Introduction. In Juan Luis Castellanos and Jean-Pierre Dedieu (eds.), Réseaux, famillles et pouvoirs dans le monde ibérique à la fin de l´Ancien Régime. Paris: CNRS, 7-30. [ Links ]

Duindam, Jeroen (1995). Myths of Power. Norbert Elias and the Early Modern European Court. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press. [ Links ]

Elias, Norbert (1987) [1969]. A Sociedade de Corte. Lisbon: Estampa.

Faria, António Machado de (1956). Livro de Linhagens do século XVI. Lisbon: Academia Portuguesa de História. [ Links ]

Freire, Anselmo Braancamp (1927) [1899-1901]. Brasões da Sala de Sintra. Coimbra: Imprensa da Universidade de Coimbra, 3 vols.

Frigo, Daniela (1985). Il padre di famiglia. Governo della casa e governo civile nella tradizione dell´economica tra Cinque e Seicento. Rome: Bulzoni. [ Links ]

Gayo, Manuel José Felgueiras (1992) [1938-1941]. Nobiliário de Famílias de Portugal. Braga: Carvalhos de Basto, 12 vols.

Góis, Damião de (2014). Livro de Linhagens de Portugal. In António Maria Falcão Pestana de Vasconcelos (ed.). Lisbon: Instituto Português de Heráldica/CLEGH/CEPESE. [ Links ]

Gomes, Rita Costa (2003) [1995]. The Making of a Court Society. Kings and Nobles in Late Medieval Portugal. Cambridge and New York: Cambridge University Press.

Labrador Arroyo, Félix (2005). La Emperatriz Isabel de Portugal, mujer de Carlos V: Casa Real y facciones cortesanas (1526-1539). Portuguese Studies Review, 13 (1-2): 135-171. [ Links ]

Meneses, Avelino Freitas de (2005) O Povoamento. In Joel Serrão and António H. Oliveira Marques (eds.), Nova História da Expansão Portuguesa. Vol. III:A Colonização Atlântica (coordinated by Artur Teodoro de Matos). Lisbon: Estampa, 209-306. [ Links ]

Morais, Cristóvão Alão de (1997) [1943-1948]. Pedatura Lusitana. Nobiliário de Famílias de Portugal. Braga: Carvalhos de Basto, 6 vols.

Moreno, Humberto Baquero (1979) [1973]. A Batalha de Alfarrobeira. Antecedentes e significado histórico, 2 vols. Coimbra: Biblioteca Geral da Universidade de Coimbra.

Mousnier, Roland (1982). Les fidélités et les clientèles en France aux XVIe, XVIIe et XVIIIe siècles.Social History/Histoire Sociale, 15 (29): 35-46. [ Links ]

Olival, Maria Fernanda (1988). Para uma análise sociológica das Ordens Militares no Portugal do Antigo Regime (1581-1621), 2 vols, MA dissertation in Early Modern History. Lisbon: Faculdade de Letras da Universidade de Lisboa. [ Links ]

Pereira, João Cordeiro (2003). Estrutura social e o seu devir. In Portugal na Era de Quinhentos. Estudos vários. Cascais: Patrimonia Historica, 299-369. [ Links ]

Riley, Carlos Guilherme (1998). Ilhas Atlânticas e Costa Africana. In Francisco Bethencourt and Kirti Chaudhuri (eds.), História da Expansão Portuguesa, vol. I. Lisbon: Círculo de Leitores, 137-62. [ Links ]

Sampaio, Luís Teixeira de (1921). Os Chavões. Porto: Typographia da Empresa Literária e Typografica. [ Links ]

Salvá, Miguel and Baranda, Pedro Sainzde (eds.) (1845). Collección de Documentos Inéditos para la Historia de España, tomo VI. Madrid: Imprenta de la Viuda de Calero. [ Links ]

Sousa, António Caetano de (1946-1955). História Genealógica da Casa Real Portuguesa. Coimbra: Atlântida, 13 vols. [ Links ]

Starkey, David (1973). The Kings Privy Chamber, 1485-1547, PhD thesis, Cambridge: University of Cambridge. [ Links ]

Ventura, Leontina (2009). D. Afonso III. Rio de Mouro: Temas e Debates. [ Links ]

Received for publication: 14 April 2015

Accepted in revised form: 4 April 2016

Recebido para publicação: 14 de Abril de 2015

Aceite após revisão: 4 de Abril de 2016

NOTES

2 Habitually referred to as Teles de Meneses or Silva Teles, being part of the House of Unhão. See Attachment 1.

3 Numbers include only the male line of the family, including illegitimate children.

4 DGARQ/TT, LN, liv.18, fl. 290.

5 The decision was made to consider only the legitimate children for the purposes of this article: the number of illegitimate children is unclear, with Gayo reporting two male children, Morais one, and theLivro de Linhagens do século XVI none whatsoever.

6 AGS, Est., Leg. 2-1, fl. 174; Leg. 2-2, fl. 397.

7 Only the offices and titles bestowed upon the male line are contemplated here.

8 DGARQ/TT, CDM, Doações..., liv.36, fl. 66v; DGARQ/TT, CDJ, Próprios, liv.47, fl. 120; DGARQ/TT,CDJ, Próprios, liv.51, fl. 77v. The remuneration considered refers to subsidies of various types, paid every two or three months, either in kind or in cash.

9 DGARQ/TT, CC, Parte I, mç. 4, nº 60.

10 DGARQ/TT, CC, Parte I, mç. 31, nº 46; Parte II, mç. 118, nº 116.

11 DGARQ/TT, CDJ, Doações..., liv. 47, fl. 1.

12 DGARQ/TT, CC, Parte I, mç. 104, fl. 87. Letter of André Teles de Meneses to Queen Catarina [Toledo, 1561-03-12].

13 AGS, Est., Leg. 369, fl. 123.

14 DGARQ/TT, CC, Parte I, mç. 108, nº 57. Letter from Rui Gomes da Silva to Queen Catarina, requesting the commandery of Ulme for his nephew, João de Saldanha [Madrid, 1567-5-25].

Copyright 2016, ISSN 1645-6432

e-JPH, Vol. 14, number 1, June 2016